Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

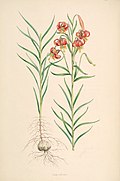

Lilium

View on Wikipedia

| Lilium | |

|---|---|

| |

| Lilium candidum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Order: | Liliales |

| Family: | Liliaceae |

| Subfamily: | Lilioideae |

| Tribe: | Lilieae |

| Genus: | Lilium L.[1] |

| Type species | |

| Lilium candidum | |

| Species | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Lilium (/ˈlɪliəm/ LIL-ee-əm)[3] is a genus of herbaceous flowering plants growing from bulbs, all with large and often prominent flowers. Lilies are a group of flowering plants which are important in culture and literature in much of the world. Most species are native to the Northern Hemisphere and their range is temperate climates and extends into the subtropics. Many other plants have "lily" in their common names, but do not belong to the same genus and are therefore not true lilies. True lilies are known to be highly toxic to cats.[4]

Description

[edit]

Lilies are tall perennials ranging in height from 1–6 ft (30–180 cm). They form naked or tunicless scaly underground bulbs which are their organs of perennation. In some North American species the base of the bulb develops into rhizomes, on which numerous small bulbs are found. Some species develop stolons.[5] Most bulbs are buried deep in the ground, but a few species form bulbs near the soil surface. Many species form stem-roots. With these, the bulb grows naturally at some depth in the soil, and each year the new stem puts out adventitious roots above the bulb as it emerges from the soil. These roots are in addition to the basal roots that develop at the base of the bulb, a number of species also produce contractile roots that move the bulbs deeper into the soil.[6]

The flowers are large, often fragrant, and come in a wide range of colors including whites, yellows, oranges, pinks, reds and purples. Markings include spots and brush strokes. The plants are late spring- or summer-flowering. Flowers are borne in racemes or umbels at the tip of the stem, with six tepals spreading or reflexed, to give flowers varying from funnel shape to a "Turk's cap". The tepals are free from each other, and bear a nectary at the base of each flower. The ovary is 'superior', borne above the point of attachment of the anthers. The fruit is a three-celled capsule.[7]

Seeds ripen in late summer. They exhibit varying and sometimes complex germination patterns, many adapted to cool temperate climates.

Most cool temperate species are deciduous and dormant in winter in their native environment. But a few species native to areas with hot summers and mild winters (Lilium candidum, Lilium catesbaei, Lilium longiflorum) lose their leaves and enter a short dormant period in summer or autumn, sprout from autumn to winter, forming dwarf stems bearing a basal rosette of leaves until, after they have received sufficient chilling, the stem begins to elongate in warming weather.

The basic chromosome number is twelve (n=12).[8]

Taxonomy

[edit]Taxonomical division in sections follows the classical division of Comber,[9] species acceptance follows the World Checklist of Selected Plant Families,[10] the taxonomy of section Pseudolirium is from the Flora of North America,[11] the taxonomy of Section Liriotypus is given in consideration of Resetnik et al. 2007,[12] the taxonomy of Chinese species (various sections) follows the Flora of China[13] and the taxonomy of Section Sinomartagon follows Nishikawa et al.[14] as does the taxonomy of Section Archelirion.[15]

The Sinomartagon are divided in three paraphyletic groups, while the Leucolirion are divided in two paraphyletic groups.[16]

There are seven sections:

- Martagon

- Pseudolirium

- Liriotypus

- Archelirion

- Sinomartagon

- Leucolirion

- Daurolirion

There are 119 species counted in this genus.[17] For a full list of accepted species with their native ranges, see List of Lilium species.

| Picture | Section | Sub Section | Botanical name | common name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Martagon | Lilium distichum | ||

|

Martagon | Lilium hansonii | ||

|

Martagon | Lilium martagon | Martagon or Turk's cap lily | |

|

Martagon | Lilium medeoloides | ||

|

Martagon | Lilium tsingtauense | ||

|

Pseudolirium | 2a | Lilium bolanderi | Bolander's Lily |

|

Pseudolirium | 2a | Lilium puberulum | |

|

Pseudolirium | 2a | Lilium kelloggii | |

|

Pseudolirium | 2a | Lilium rubescens | |

|

Pseudolirium | 2a | Lilium washingtonianum | Washington Lily, Shasta Lily, or Mt. Hood Lily |

|

Pseudolirium | 2b | Lilium kelleyanum | |

|

Pseudolirium | 2b | Lilium maritimum | |

|

Pseudolirium | 2b | Lilium occidentale | |

|

Pseudolirium | 2b | Lilium pardalinum | Panther or Leopard lily |

|

Pseudolirium | 2b | Lilium parryi | |

|

Pseudolirium | 2b | Lilium parvum | Sierra tiger lily or Alpine lily |

|

Pseudolirium | 2c | Lilium canadense | Canada Lily or Meadow Lily |

|

Pseudolirium | 2c | Lilium grayi | |

|

Pseudolirium | 2c | Lilium iridollae | |

|

Pseudolirium | 2c | Lilium michiganense | Michigan Lily |

|

Pseudolirium | 2c | Lilium michauxii | Carolina Lily |

|

Pseudolirium | 2c | Lilium superbum | Swamp lily or American tiger lily |

|

Pseudolirium | 2c | Lilium pyrophilum | Sandhills Lily[18] |

|

Pseudolirium | 2d | Lilium catesbaei | |

|

Pseudolirium | 2d | Lilium philadelphicum | Wood lily, Philadelphia lily or prairie lily |

|

Liriotypus | 3a | Lilium candidum | Madonna lily |

|

Liriotypus | 3b | Lilium albanicum | |

|

Liriotypus | 3b | Lilium bosniacum (Lilium carniolicum var. bosniacum) | |

|

Liriotypus | 3b | Lilium chalcedonicum | |

|

Liriotypus | 3b | Lilium carniolicum | |

|

Liriotypus | 3b | Lilium ciliatum | |

| Liriotypus | 3b | Lilium heldreichii | ||

|

Liriotypus | 3b | Lilium jankae | |

|

Liriotypus | 3b | Lilium pomponium | Turban lily |

|

Liriotypus | 3b | Lilium ponticum | |

|

Liriotypus | 3b | Lilium pyrenaicum | |

|

Liriotypus | 3c | Lilium akkusianum | |

|

Liriotypus | 3c | Lilium kesselringianum | |

|

Liriotypus | 3c | Lilium monadelphum | |

|

Liriotypus | 3c | Lilium rhodopeum | |

|

Liriotypus | 3c | Lilium szovitsianum | Polish Lily |

|

Liriotypus | 3c | Lilium polyphyllum | |

|

Liriotypus | 3c | Lilium ledebourii | |

|

Liriotypus | 3d | Lilium bulbiferum | Orange Lily or Fire Lily |

|

Archelirion | 4a | Lilium speciosum | Japanese lily |

|

Archelirion | 4b | Lilium auratum | Golden rayed lily of Japan, or Goldband lily |

|

Archelirion | 4c | Lilium alexandrae | |

|

Archelirion | 4c | Lilium japonicum | |

|

Archelirion | 4c | Lilium nobilissimum | |

|

Archelirion | 4d | Lilium brownii | |

|

Archelirion | 4d | Lilium rubellum | |

|

Archelirion | 4d | Lilium platyphyllum | |

|

Sinomartagon | 5a | Lilium davidii | |

|

Sinomartagon | 5a | Lilium duchartrei | |

|

Sinomartagon | 5a | Lilium henryi | Tiger Lily or Henry's lily |

|

Sinomartagon | 5a | Lilium lancifolium | Tiger Lily (often known as L. tigrinum) |

|

Sinomartagon | 5a | Lilium lankongense | |

|

Sinomartagon | 5a | Lilium leichtlinii | |

|

Sinomartagon | 5a | Lilium papilliferum | |

|

Sinomartagon | 5a | Lilium rosthornii | |

|

Sinomartagon | 5b | Lilium amabile | |

|

Sinomartagon | 5b | Lilium callosum | |

|

Sinomartagon | 5b | Lilium cernuum | |

|

Sinomartagon | 5b | Lilium concolor | Morning Star Lily |

|

Sinomartagon | 5b | Lilium fargesii | |

|

Sinomartagon | 5b | Lilium pumilum | Coral Lily, Low Lily, or Siberian Lily |

| Sinomartagon | 5b | Lilium xanthellum | ||

|

Sinomartagon | 5c | Lilium amoenum | |

| Sinomartagon | 5c | Lilium arboricola | ||

|

Sinomartagon | 5c | Lilium bakerianum | |

|

Sinomartagon | 5c | Lilium euxanthum | |

| Sinomartagon | 5c | Lilium henrici | ||

|

Sinomartagon | 5c | Lilium lophophorum | |

|

Sinomartagon | 5c | Lilium mackliniae | Siroi Lily |

|

Sinomartagon | 5c | Lilium majoense | |

|

Sinomartagon | 5c | Lilium nanum | |

|

Sinomartagon | 5c | Lilium nepalense | |

|

Sinomartagon | 5c | Lilium oxypetalum | |

| Sinomartagon | 5c | Lilium paradoxum | ||

|

Sinomartagon | 5c | Lilium poilanei | |

|

Sinomartagon | 5c | Lilium primulinum | |

| Sinomartagon | 5c | Lilium sempervivoideum | ||

| Sinomartagon | 5c | Lilium sherriffiae | ||

|

Sinomartagon | 5c | Lilium souliei | |

| Sinomartagon | 5c | Lilium stewartianum | ||

|

Sinomartagon | 5c | Lilium taliense | |

|

Sinomartagon | 5c | Lilium wardii | |

| Sinomartagon | 5? | Lilium brevistylum | ||

|

Sinomartagon | 5? | Lilium lijiangense | |

| Sinomartagon | 5? | Lilium anhuiense | ||

| Sinomartagon | 5? | Lilium eupetes | ||

|

Sinomartagon | 5? | Lilium habaense | |

| Sinomartagon | 5? | Lilium huidongense | ||

| Sinomartagon | 5? | Lilium jinfushanense | ||

| Sinomartagon | 5? | Lilium matangense | ||

| Sinomartagon | 5? | Lilium medogense | ||

| Sinomartagon | 5? | Lilium pinifolium | ||

| Sinomartagon | 5? | Lilium pyi | ||

| Sinomartagon | 5? | Lilium saccatum | ||

| Sinomartagon | 5? | Lilium tianschanicum | ||

| Sinomartagon | 5? | Lilium floridum | ||

|

Leucolirion | 6a | Lilium leucanthum | |

|

Leucolirion | 6a | Lilium regale | |

|

Leucolirion | 6a | Lilium sargentiae | |

|

Leucolirion | 6a | Lilium sulphureum | |

|

Leucolirion | 6a | Lilium wenshanense | |

| Leucolirion | 6b | Lilium anhuiense | ||

|

Leucolirion | 6b | Lilium formosanum | |

|

Leucolirion | 6b | Lilium longiflorum | Easter Lily |

| Leucolirion | 6b | Lilium neilgherrense | ||

|

Leucolirion | 6b | Lilium philippinense | Benguet lily[19][20] |

|

Leucolirion | 6b | Lilium wallichianum | |

| Leucolirion | 6b | Lilium zairii | ||

|

Leucolirion | 6b | Lilium puerense | |

|

Daurolirion | Lilium dauricum | ||

|

Daurolirion | Lilium maculatum | ||

|

Daurolirion | Lilium pensylvanicum | ||

| Lilium eupetes | ||||

|

Lilium armenum | |||

|

Lilium bosniacum | |||

|

Lilium columbianum | |||

|

Lilium debile | |||

|

Lilium humboldtii | |||

| Lilium rockii |

Some species formerly included within this genus have now been placed in other genera. These genera include Cardiocrinum, Notholirion, and Fritillaria.[21][22][23] Four other genuses, Lirium, Martagon, and Nomocharis are considered to synonyms by most sources.[17]

Etymology

[edit]The botanic name Lilium is the Latin form and is a Linnaean name. The Latin name is derived from the Greek word λείριον leírion, generally assumed to refer to true, white lilies as exemplified by the Madonna lily.[24][25][26] The word was borrowed from Coptic ϩ̀ⲣⲏⲣⲓ,[27] from Demotic ḥrry, from Egyptian ḥrr.t "flower".[28] Ancient Greek: κρῖνον, krīnon, was used by the Greeks, albeit for lilies of any color.[29]

The term "lily" has in the past been applied to numerous flowering plants, often with only superficial resemblance to the true lily, including water lily, fire lily, lily of the Nile, calla lily, trout lily, kaffir lily, cobra lily, lily of the valley, daylily, ginger lily, Amazon lily, leek lily, Peruvian lily, and others. All English translations of the Bible render the Hebrew shūshan, shōshan, shōshannā as "lily", but the "lily among the thorns" of Song of Solomon, for instance, may be the honeysuckle.[30]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]

The range of lilies in the Old World extends across much of Europe, across most of Asia to Japan, south to India, and east to Indochina and the Philippines. In the New World they extend from southern Canada through much of the United States. They are commonly adapted to either woodland habitats, often montane, or sometimes to grassland habitats. A few can survive in marshland and epiphytes are known in tropical southeast Asia. In general they prefer moderately acidic or lime-free soils.

Ecology

[edit]Lilies are used as food plants by the larvae of some Lepidoptera species including the Dun-bar.

The proliferation of deer (e.g. Odocoileus virginianus) in North America, mainly due to factors such as the elimination of large predators for human safety, is responsible there for a downturn in lily populations in the wild and is a threat to garden lilies as well.[31] Fences as high as 8 feet may be required to prevent them from consuming the plants, an impractical solution for most wild areas.[32]

Cultivation

[edit]Many species are widely grown in the garden in temperate, sub-tropical and tropical regions.[33] Numerous ornamental hybrids have been developed. They are used in herbaceous borders, woodland and shrub plantings, and as patio plants. Some lilies, especially Lilium longiflorum, form important cut flower crops or potted plants. These are forced to flower outside of the normal flowering season for particular markets; for instance, Lilium longiflorum for the Easter trade, when it may be called the Easter lily.

Lilies are usually planted as bulbs in the dormant season. They are best planted in a south-facing (northern hemisphere), slightly sloping aspect, in sun or part shade, at a depth 2½ times the height of the bulb (except Lilium candidum which should be planted at the surface). Most prefer a porous, loamy soil, and good drainage is essential. Most species bloom in July or August (northern hemisphere). The flowering periods of certain lily species begin in late spring, while others bloom in late summer or early autumn.[34] They have contractile roots which pull the plant down to the correct depth, therefore it is better to plant them too shallowly than too deep. A soil pH of around 6.5 is generally safe. Most grow best in well-drained soils, and plants are watered during the growing season. Some species and cultivars have strong wiry stems, but those with heavy flower heads are staked to stay upright.[35][36]

Awards

[edit]The following lily species and cultivars currently hold the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit (confirmed 2017):[37][38]

- African Queen Group (VI-/a) 2002 H6

- 'Casa Blanca' (VIIb/b-c) 1993 H6

- 'Fata Morgana' (Ia/b) 2002 H6

- 'Garden Party' (VIIb/b) 2002 H6

- Golden Splendor Group (VIb-c/a)[39]

- Lilium henryi (IXc/d) 1993 H6

- Lilium mackliniae (IXc/a) 2012 H5

- Lilium martagon – Turk's cap lily (IXc/d)[40]

- Lilium pardalinum – leopard lily (IXc/d)[41]

- Pink Perfection Group (VIb/a)[42]

- Lilium regale – regal lily, king's lily (IXb/a)[43]

Classification of garden forms

[edit]Numerous forms, mostly hybrids, are grown for the garden. They vary according to the species and interspecific hybrids that they derived from, and are classified in the following broad groups:[44][45][46]

Asiatic hybrids (Division I)

[edit]- These are derived from hybrids between species in Lilium section Sinomartagon.[47][48]

- They are derived from central and East Asian species and interspecific hybrids, including Lilium amabile, Lilium bulbiferum, Lilium callosum, Lilium cernuum, Lilium concolor, Lilium dauricum, Lilium davidii, Lilium × hollandicum, Lilium lancifolium (syn. Lilium tigrinum), Lilium lankongense, Lilium leichtlinii, Lilium × maculatum, Lilium pumilum, Lilium × scottiae, Lilium wardii and Lilium wilsonii.

- These are plants with medium-sized, upright or outward facing flowers, mostly unscented. There are various cultivars such as Lilium 'Cappuccino', Lilium 'Dimension', Lilium 'Little Kiss' and Lilium 'Navona'.[49]

- Dwarf (Patio, Border) varieties are much shorter, c.36–61 cm in height and were designed for containers.[50] They often bear the cultivar name 'Tiny', such as the 'Lily Looks' series, e.g. 'Tiny Padhye',[51] 'Tiny Dessert'.[52]

Martagon hybrids (Division II)

[edit]- These are based on Lilium dalhansonii, Lilium hansonii, Lilium martagon, Lilium medeoloides, and Lilium tsingtauense.

- The flowers are nodding, Turk's cap style (with the petals strongly recurved).

Candidum (Euro-Caucasian) hybrids (Division III)

[edit]- This includes mostly European species: Lilium candidum, Lilium chalcedonicum, Lilium kesselringianum, Lilium monadelphum, Lilium pomponium, Lilium pyrenaicum and Lilium × testaceum.

American hybrids (Division IV)

[edit]- These are mostly taller growing forms, originally derived from Lilium bolanderi, Lilium × burbankii, Lilium canadense, Lilium columbianum, Lilium grayi, Lilium humboldtii, Lilium kelleyanum, Lilium kelloggii, Lilium maritimum, Lilium michauxii, Lilium michiganense, Lilium occidentale, Lilium × pardaboldtii, Lilium pardalinum, Lilium parryi, Lilium parvum, Lilium philadelphicum, Lilium pitkinense, Lilium superbum, Lilium ollmeri, Lilium washingtonianum, and Lilium wigginsii.

- Many are clump-forming perennials with rhizomatous rootstocks.

Longiflorum hybrids (Division V)

[edit]- These are cultivated forms of this species and its subspecies.

- They are most important as plants for cut flowers, and are less often grown in the garden than other hybrids.

Trumpet lilies (Division VI), including Aurelian hybrids (with L. henryi)

[edit]

- This group includes hybrids of many Asiatic species and their interspecific hybrids, including Lilium × aurelianense, Lilium brownii, Lilium × centigale, Lilium henryi, Lilium × imperiale, Lilium × kewense, Lilium leucanthum, Lilium regale, Lilium rosthornii, Lilium sargentiae, Lilium sulphureum and Lilium × sulphurgale.

- The flowers are trumpet shaped, facing outward or somewhat downward, and tend to be strongly fragrant, often especially night-fragrant.

Oriental hybrids (Division VII)

[edit]

- These are based on hybrids within Lilium section Archelirion,[47][48] specifically Lilium auratum and Lilium speciosum, together with crossbreeds from several species native to Japan, including Lilium nobilissimum, Lilium rubellum, Lilium alexandrae, and Lilium japonicum.

- They are fragrant, and the flowers tend to be outward facing. Plants tend to be tall, and the flowers may be quite large. The whole group are sometimes referred to as "stargazers" because many of them appear to look upwards. (For the specific cultivar, see Lilium 'Stargazer'.)

Other hybrids (Division VIII)

[edit]- Includes all other garden hybrids.

Species (Division IX)

[edit]- All natural species and naturally occurring forms are included in this group.

The flowers can be classified by flower aspect and form:[53]

- Flower aspect:

- a up-facing

- b out-facing

- c down-facing

- Flower form:

- a trumpet-shaped

- b bowl-shaped

- c flat (or with tepal tips recurved)

- d tepals strongly recurved (with the Turk's cap form as the ultimate state)

Many newer commercial varieties are developed by using new technologies such as ovary culture and embryo rescue.[54]

Pests and diseases

[edit]

Aphids may infest plants. Leatherjackets feed on the roots. Larvae of the Scarlet lily beetle can cause serious damage to the stems and leaves. The scarlet beetle lays its eggs and completes its life cycle only on true lilies (Lilium) and fritillaries (Fritillaria).[55] Oriental, rubrum, tiger and trumpet lilies as well as Oriental trumpets (orienpets) and Turk's cap lilies and native North American Lilium species are all vulnerable, but the beetle prefers some types over others. The beetle could also be having an effect on native Canadian species and some rare and endangered species found in northeastern North America.[56] Daylilies (Hemerocallis, not true lilies) are excluded from this category. Plants can suffer from damage caused by mice, deer and squirrels. Slugs,[57] snails and millipedes attack seedlings, leaves and flowers.

Brown spots on damp leaves may signal an infection of Botrytis elliptica, also known as Lily blight, lily fire, and botrytis leaf blight.[58] Various viral diseases can cause mottling of leaves and stunting of growth, including lily curl stripe, ringspot, and lily rosette virus.[59]

Propagation and growth

[edit]Lilies can be propagated in several ways;

- by division of the bulbs

- by growing-on bulbils which are adventitious bulbs formed on the stem

- by scaling, for which whole scales are detached from the bulb and planted to form a new bulb

- by seed; there are many seed germination patterns, which can be complex

- by micropropagation techniques (which include tissue culture);[60] commercial quantities of lilies are often propagated in vitro and then planted out to grow into plants large enough to sell. A highly efficient technique for multiple shoot and propagule formation was given by Yadav et al., in 2013.[61]

Plant grow regulators (PGRs) are used to limit the height of lilies, especially those sold as potted plants. Commonly used chemicals include ancymidol, fluprimidol, paclobutrazol, and uni-conazole, all of which are applied to the foliage to slow the biosynthesis of gibberellins, a class of plant hormones responsible for stem growth.[62]

Research

[edit]A comparison of meiotic crossing-over (recombination) in lily and mouse led, in 1977, to the conclusion that diverse eukaryotes share a common pattern of meiotic crossing-over.[63] Lilium longiflorum has been used for studying aspects of the basic molecular mechanism of genetic recombination during meiosis.[64][65]

Toxicity

[edit]Some Lilium species are toxic to cats. This is known to be so especially for Lilium longiflorum, though other Lilium and the unrelated Hemerocallis can also cause the same symptoms with equal lethality.[66][67][68][69] The true mechanism of toxicity is undetermined, but it involves damage to the renal tubular epithelium (composing the substance of the kidney and secreting, collecting, and conducting urine), which can cause acute kidney failure.[69] Veterinary help should be sought, as a matter of urgency, for any cat that is suspected of eating any part of a lily – including licking pollen that may have brushed onto its coat. Due to the high mortality rate, medical care should be sought immediately once it is known a cat came into contact with lilies, ideally before any symptoms develop.[70]

Culinary uses

[edit]

Chinese cuisine

[edit]Lily bulbs are starchy and edible as root vegetables, though bulbs of some species may be too bitter to eat.[71]

Lilium brownii var. viridulum, known as 百合 (pak hop; pinyin: bǎi hé; Cantonese Yale: baak hap; lit. 'hundred united'), is one of the most prominent edible lilies in China. Its bulbs are large in size and not bitter. They were even exported and sold in the San Francisco Chinatown in the 19th century, available both fresh and dry.[71] A landrace called 龍牙百合 (pinyin: lóng yá bǎi hé; lit. 'dragon-tooth lily') mainly cultivated in Hunan and Jiangxi is especially renowned for its good-quality bulbs.[72]

L. lancifolium (Chinese: 卷丹; pinyin: juǎn dān; lit. 'reflexed red') is widely cultivated in China, especially in Yixing, Huzhou and Longshan. Its bulbs are slightly bitter.[72]

L. davidii var. unicolor (Chinese: 蘭州百合; lit. 'Lanzhou lily') is mainly cultivated in Lanzhou and its bulbs are valued for sweetness.[72]

Other edible Chinese lilies include L. brownii var. brownii, L. davidii var. davidii, L. concolor, L. pensylvanicum, L. distichum, L. martagon var. pilosiusculum, L. pumilum, L. rosthornii and L. speciosum var. gloriosoides.[73] Researchers have also explored the possibility of using ornamental cultivars as edible lilies.[76]

The dried bulbs are commonly used in the south to flavor soup.[citation needed] They may be reconstituted and stir-fried, grated and used to thicken soup, or processed to extract starch.[citation needed] Their texture and taste draw comparisons with the potato, although the individual bulb scales are much smaller.[citation needed]

The commonly marketed "lily" flower buds, called kam cham tsoi (Chinese: 金针菜; pinyin: jīnzhēncài; Cantonese Yale: gāmjām choi; lit. 'gold needle vegetable')[77] in Chinese cuisine, are actually from daylilies, Hemerocallis citrina,[78] or possibly H. fulva.[a][77] Flowers of the H. graminea and Lilium bulbiferum were reported to have been eaten as well, but samples provided by the informant were strictly daylilies and did not include L. bulbiferum.[b][79]

Lily flowers and bulbs are eaten especially in the summer, for their perceived ability to reduce internal heat.[80] A 19th century English source reported that "Lily flowers are also said to be efficacious in pulmonary affections, and to have tonic properties".[79]

Asiatic lily cultivars are also imported from the Netherlands; the seedling bulbs must be imported from the Netherlands every year.[81][82][83]

The parts of Lilium species which are officially listed as food material in Taiwan are the flower and bulbs of Lilium lancifolium, Lilium brownii var. viridulum, Lilium pumilum and Lilium candidum.[84]

Japanese cuisine

[edit]

The lily bulb or yuri-ne is sometimes used in Japanese cuisine.[c][85] It may be most familiar in the present day as an occasional ingredient (具, gu) in the chawan-mushi (savoury egg custard),[86] where a few loosened scales of this optional ingredient are found embedded in the "hot pudding" of each serving.[87][88] It could also be used as an ingredient in a clear soup or suimono.[89][90]

The boiled bulb may also be strained[d] into purée for use, as in the sweetened kinton,[91][92] or chakin-shibori.[92][93][e]

Yokan

[edit]There is also the yuri-yōkan, one recipe of which calls for combining measures of yuri starch with agar dissolved in water and sugar.[95] This was a specialty of Hamada, Shimane,[96] and the shop Kaisei-dō (開盛堂) established in 1885 became famous for it.[97][98] Because a certain Viscount Jimyōin wrote a waka poem about the confection which mentioned hime-yuri "princess lily",[f] one source stated that the hime-yuri (usually taken to mean L. concolor) had to have been used,[97] but another source points out that the city of Hamada lies back to back with across a mountain range with Fuchu, Hiroshima which is renowned for its production of yama-yuri (L. auratum).[94][g]

Species used

[edit]Current Japanese governmental sources (c. 2005) list the following lily species as prominent in domestic consumption:[102][103] the oni yuri or tiger lily Lilium lancifolium, the kooni yuri Lilium leichtlinii var. maximowiczii,[h] and the gold-banded white yama-yuri L. auratum.

But Japanese sources c. 1895–1900,[99][104] give a top-three list which replaces kooni yuri with the sukashi-yuri (透かし百合; lit. "see-through lily", L. maculatum) named from the gaps between the tepals.[105][106]

There is uncertainty regarding which species is meant by the hime-yuri used as food, because although this is usually the common name for L. concolor in most up-to-date literature,[107] it used to ambiguously referred to the tiger lily as well, c. 1895–1900.[99] The non-tiger-lily himeyuri is certainly described as quite palatable in the literature at the time, but the extent of exploitation could not have been as significant.[i]

North America

[edit]The flower buds and roots of Lilium columbianum are traditionally gathered and eaten by North American indigenous peoples.[108] Coast Salish, Nuu-chah-nulth and most western Washington peoples steam, boil or pit-cook the bulbs of Lilium columbianum. Bitter or peppery-tasting, they were mostly used as a flavoring, often in soup with meat or fish.[109]

Medicinal uses

[edit]Traditional Chinese medicine list the use of the following: 野百合 Lilium brownii, 百合 Lilium brownii var. viridulum, 渥丹 Lilium concolor, 毛百合 Lilium dauricum, 卷丹 Lilium lancifolium, 山丹 Lilium pumilum, 南川百合 Lilium rosthornii, 药百合Lilium speciosum var. gloriosoides, 淡黄花百合 Lilium sulphureum.[110][111]

In Taiwan, governmental publications list Lilium lancifolium Thunb., Lilium brownii var. viridulum Baker, Lilium pumilum DC.[112]

In the kanpō or Chinese medicine as practiced in Japan, the official Japanese governmental pharmacopeia Nihon yakkyokuhō (日本薬局方) includes the use of lily bulb (known as byakugō (ビャクゴウ 百合) in traditional pharmacological circles), listing the use of the following species: Lilium lancifolium, Lilium brownii, Lilium brownii var. colchesteri, Lilium pumilum[113] The scales flaked off from the bulbs are used, usually steamed.[113]

In South Korea, the lilium species which are officially listed for medicinal use are 참나리 Lilium lancifolium Thunberg; 당나리 Lilium brownii var. viridulun Baker.[114][115]

In culture

[edit]Symbolism

[edit]In the Victorian language of flowers, lilies portray love, ardor, and affection for your loved ones, while orange lilies stand for happiness, love, and warmth.[116]

White lilies have been used since the Romantic era of Japanese literature to symbolize beauty and purity in women, and are a de facto symbol of the yuri genre (yuri (百合) translates literally to "lily"),[117] which describes the portrayal of intimate love, sex, or emotional connections between women. The term Yurizoku (百合族; lit. "lily tribe") was coined in 1976 by Ito Bungaku, editor of the gay men's magazine Barazoku (see above), to refer to his female readers.[118][119] While not all those women were lesbians, and it is unclear whether this was the first instance of the term yuri in this context, an association of yuri with lesbianism subsequently developed.[120] In Korea and China, "lily" is used as a semantic loan from the Japanese usage to describe female-female romance media, where each use the direct translation of the term – baekhap (백합) in Korea[121] and bǎihé (百合) in China.[122]

Lilies are the flowers most commonly used at funerals, where they symbolically signify that the soul of the deceased has been restored to the state of innocence.[123]

Lilium formosanum, or Taiwanese lily, is called "the flower of broken bowl" (Chinese: 打碗花) by the elderly members of the Hakka ethnic group. They believe that because this lily grows near bodies of clean water, harming the lily may damage the environment, just like breaking the bowls that people rely on.[124] A different viewpoint proposes that parents discourage kids from picking lilies by informing them of the possible repercussions, like their dinner bowls breaking if they harm the flower. The indigenous Rukai people who call this same species bariangalay consider it as a symbol of bravery and perseverance.[125]

In Western Christianity, Madonna lily or Lilium candidum has been associated with the Virgin Mary since at least the Medieval Era. Medieval and Renaissance depictions of the Virgin Mary, especially at the Annunciation, often show her with these flowers. Madonna lilies are also commonly included in depictions of Christ's resurrection. Lilium longiflorum, the Easter lily, is a symbol of Easter, and Lilium candidum, the Madonna lily, carries a great deal of symbolic value in many cultures. See the articles for more information.

In Ancient Minoan Crete and Cyclades cultures, lilies are depicted associated with an unknown religious meaning. The crown from the "Priest-King" fresco at Knossos is covered with white lilies while a depiction of a shrine in the Xesté 3 house Akrotiri is covered in red lilies.[126]

Heraldry

[edit]Lilium bulbiferum has long been recognised as a symbol of the Orange Order in Northern Ireland.[127]

Lilium mackliniae is the state flower of Manipur. Lilium michauxii, the Carolina lily, is the official state flower of North Carolina. Idyllwild, California, hosts the Lemon Lily Festival, which celebrates Lilium parryi.[128] Lilium philadelphicum is the floral emblem of Saskatchewan province in Canada, and is on the flag of Saskatchewan.[129][130][131]

Other plants referred to as lilies

[edit]Lily of the valley, flame lilies, daylilies, water lilies and spider lilies are symbolically important flowers commonly referred to as lilies, but they are not in the genus Lilium.

See also

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Blasdale cites Bretschneider (1889), but in Bretschneider (1875), "Notes on Chinese Mediaeval Travellers to the West", p. 123, first gives the Chinese name for H. fulva as "kïm châm hōa" as according to João de Loureiro, while he himself only recognized its name as "kin huang hua" 金黃花 or as [黃花菜]; huang-hua ts'ai; 'yellow-flower vegetable' as they were called by Beijing merchants.

- ^ The informant, Pelham L. Warren, consul at Taiwan was presumably providing imports from China (main port Hankou) or Japan.

- ^ "not a common food" (Shizuo Tsuji).

- ^ The term uragoshi "straining" orthodoxically means using the "uragoshi-ki", traditionally a sieve with a fine mesh of horse-hair instead of metal wire.

- ^ These could refer to essentially the same thing, except for slight difference in texture and appearance. The yuri-kinton has been described as "ogura an (sweet adzuki bean paste) core surrounded with stipples (soboro) of strained lily bulb and white adzuki (shiroazuki or shiroshōzu).[94] A recipe for lily bulb dumplings or chakin-shibori calls for wrapping adzuki bean paste with lily bulb mashed into purée, then wrapping it in a cloth and wringing the dumpling into a ball shape.[93]

- ^ Jimyōin Motoaki b. 1865 was a viscount and poet. So was his son Motonori.

- ^ And as discussed below, this yama-yuri was also called "hime-yuri" in earlier days.[99]

- ^ The kooni yuri (小鬼百合; "lesser ogre lily").

- ^ That is, not in the top three of this period.[99]

References

[edit]- Citations

- ^ a b "Lilium". World Checklist of Selected Plant Families. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved June 13, 2014.

- ^ lectotype designated by N. L. Britton et A. Brown, Ill. Fl. N. U.S. ed. 2. 1: 502 (1913)

- ^ "lilium". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ Langston, Cathy E. (2002-01-01). "Acute renal failure caused by lily ingestion in six cats". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 220 (1): 49–52. doi:10.2460/javma.2002.220.49. ISSN 0003-1488. PMID 12680447.

- ^ Batygina, T. B. (2019-04-23). Embryology of Flowering Plants: Terminology and Concepts, Vol. 3: Reproductive Systems. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-429-52671-8.

- ^ Gracie, Carol (2020-04-28). Summer Wildflowers of the Northeast: A Natural History. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-20330-0.

- ^ European Garden Flora; Volume 1

- ^ Pelkonen, Veli-Pekka; Pirttilä, Anna-Maria (2012). "Taxonomy and Phylogeny of the Genus Lilium" (PDF). Floriculture and Ornamental Biotechnology. 6 (Special Issue 2): 1–8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-10-08. Retrieved 2016-07-29.

- ^ Harold Comber, 1949. "A new classification of the genus Lilium". Lily Yearbook, Royal Hortic. Soc., London. 15:86–105.

- ^ Govaerts, R. (ed.). "Lilium". World Checklist of Selected Plant Families. The Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Archived from the original on 2020-09-01. Retrieved 2013-02-03.

- ^ Flora of North America, Vol. 26, Online Archived 2012-10-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Resetnik I.; Liber Z.; Satovic Z.; Cigic P.; Nikolic T. (2007). "Molecular phylogeny and systematics of the Lilium carniolicum group (Liliaceae) based on nuclear ITS sequences". Plant Systematics and Evolution. 265 (1–2): 45–58. Bibcode:2007PSyEv.265...45R. doi:10.1007/s00606-006-0513-y. S2CID 32644749.

- ^ Flora of China, Vol. 24, eFloras.org Archived 2012-09-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Nishikawa Tomotaro; Okazaki Keiichi; Arakawa Katsuro; Nagamine Tsukasa (2001). "Phylogenetic Analysis of Section Sinomartagon in Genus Lilium Using Sequences of the Internal Transcribed Spacer Region in Nuclear Ribosomal DNA". 育種学雑誌 Breeding Science. 51 (1): 39–46. Bibcode:2001BrSci..51...39N. doi:10.1270/jsbbs.51.39.

- ^ Nishikawa Tomotaro; Okazaki Keiichi; Nagamine Tsukasa (2002). "Phylogenetic Relationships among Lilium auratum Lindley, L. auratum var. platyphyllum Baker and L. rubellum Baker Based on Three Spacer Regions in Chloroplast DNA". 育種学雑誌 Breeding Science. 52 (3): 207–213. Bibcode:2002BrSci..52..207N. doi:10.1270/jsbbs.52.207.

- ^ Li Juan; Cai Jing; Qin Huan-Huan; Price Megan; Zhang Zhen; Yu Yan; Xie Deng-Feng; He Xing-Jin; Zhou Song-Dong; Gao Xin-Fen (2022). "Phylogeny, Age, and Evolution of Tribe Lilieae (Liliaceae) Based on Whole Plastid Genomes". Frontiers in Plant Science. 12 699226. Bibcode:2022FrPS...1299226L. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.699226. ISSN 1664-462X. PMC 8845482. PMID 35178055.

- ^ a b "Lilium Tourn. ex L." Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ "Lilium pyrophilum in Flora of North America @". Efloras.org. Archived from the original on 2012-10-20. Retrieved 2013-02-03.

- ^ "Lilium philippinense (Benguet lily)". Shoot Limited. Archived from the original on 10 February 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ^ "Park personnel rear vanishing Benguet lily". Sun.Star Baguio. 13 August 2013. Archived from the original on 10 February 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ^ "Cardiocrinum (Endl.) Lindl". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ "Notholirion Wall. ex Boiss". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ "Fritillaria Tourn. ex L." Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ Hyam, R. & Pankhurst, R.J. (1995). Plants and their names: a concise dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-19-866189-4.

- ^ "Classification". Lily Net. Archived from the original on 15 April 2008. Retrieved 22 June 2008.

- ^ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1940). "λείριον". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus Digital Library.

- ^ Beekes, Robert S. P. (2010). Etymological Dictionary of Greek. Koninklijke Brill NV. p. 845. Retrieved 2025-06-12.

- ^ Crum, W. E. (1939). A Coptic Dictionary. Oxford University Press. p. 704. Retrieved 2025-06-12. "ϩⲣⲏⲣⲉ". Coptic Dictionary Online. Retrieved 2025-06-12.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 687.

- ^ Shorter Oxford English dictionary, 6th ed. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. 2007. p. 3804. ISBN 978-0-19-920687-2.

- ^ "Ecological Impacts of High Deer Densities". Teaching Issues and Experiments in Ecology. Ecological Society of America. 2004. Archived from the original on 2019-11-27. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- ^ "Will Deer Eat Hostas & Lilies?". SFGate. Hearst. Archived from the original on 2019-11-27. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- ^ "Azucenas en tierra boricua trascienden generaciones [Lilium in Puerto Rican land transcend generations]". El Nuevo Día (in Spanish). 2017-07-08. Archived from the original on 2020-07-19. Retrieved 2020-07-19.

- ^ "Lily". 2016. Archived from the original on 2014-02-25. Retrieved 2014-02-19.

- ^ RHS encyclopedia of plants & flowers. United Kingdom: Dorling Kindersley. 2010. p. 744. ISBN 978-1-4053-5423-3.

- ^ Jefferson-Brown, Michael (2008). Lilies. Wisley handbooks. London: Mitchell Beazley. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-84533-384-3.

- ^ "AGM Plants – Ornamental" (PDF). Royal Horticultural Society. July 2017. p. 60. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 January 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ "British Gardening Statistics". British Gardening Statistics. Our Country Garden. 10 May 2024. Retrieved January 28, 2025.

- ^ "RHS Plantfinder – Lilium Golden Splendor Group". Archived from the original on 24 March 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ "RHS Plantfinder – Lilium martagon". Archived from the original on 25 March 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ "RHS Plantfinder – Lilium pardalinum". Archived from the original on 24 March 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ "RHS Plantfinder – Lilium Pink Perfection Group". Archived from the original on 24 March 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ "RHS Plantfinder – Lilium regale". Archived from the original on 24 March 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ "North American Lily Society: Types of Lilies". Lilies.org. Archived from the original on 2013-11-03. Retrieved 2013-02-03.

- ^ RHS A-Z encyclopedia of garden plants. United Kingdom: Dorling Kindersley. 2008. p. 1136. ISBN 978-1-4053-3296-5.

- ^ "The RHS is the International Registration Authority for lilies". Archived from the original on 2014-05-21. Retrieved 2014-05-21.

- ^ a b Barba-Gonzalez, R.; Lokker, A.C.; Lim, K.B.; Ramanna, M.S.; Van Tuyl, J.M. (2004). "Use of 2n gametes for the production of sexual polyploids from sterile Oriental × Asiatic hybrids of lilies (Lilium)". Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 109 (6): 1125–1132. doi:10.1007/s00122-004-1739-0. PMID 15290047. S2CID 7992120.

- ^ a b van Tuyl, J.M.; Arens, P. (2011). "Lilium: Breeding History of the Modern Cultivar Assortment" (PDF). Acta Horticulturae. 900: 223–230. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-06-06.

- ^ "Lilium Asiatic Navona – Lily". brentandbeckysbulbs.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- ^ "Tina M. Smith. Production of Hybrid Lilies as Pot Plants. University of Massachusetts, Amherst". Center for Agriculture, Food and the Environment. Archived from the original on 2014-08-10. Retrieved 2014-08-06.

- ^ "Plant Profile for Lilium 'Tiny Padhye' – Dwarf Asiatic Lily Perennial". Archived from the original on 2015-05-08. Retrieved 2014-08-06.

- ^ "Plant Profile for Lilium 'Tiny Dessert' – Dwarf Asiatic Lily Perennial". Archived from the original on 2014-08-11. Retrieved 2014-08-07.

- ^ The RHS International Lily Registrar. "Application For Registration Of A Lily Name". Royal Horticultural Society. Archived from the original on 22 May 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ van Tuyl, J.M.; Binoa, R.J.; Vancreij, M.; Vankleinwee, T.; Franken, J.; Bino, R. (1991). "Application of in vitro pollination, ovary culture, ovule culture and embryo rescue for overcoming incongruity barriers in interspecific Lilium crosses". Plant Science. 74 (1): 115–126. Bibcode:1991PlnSc..74..115V. doi:10.1016/0168-9452(91)90262-7.

- ^ "Lily beetle". RHS Gardening. Royal Horticultural Society. Archived from the original on 2014-08-21. Retrieved 2014-08-21.

- ^ Whitman, Ann. "Controlling Lily Leaf Beetles". Gardener's Supply Company. Archived from the original on 2014-02-22. Retrieved 2014-02-18.

- ^ Adams, Charles; Early, Mike; Brook, Jane; Bamford, Katherine (2014-08-07). Principles of Horticulture: Level 2. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-93777-7.

- ^ George, Raymond A. T.; Fox, Roland T. V. (2014-11-21). Diseases of Temperate Horticultural Plants. CABI. ISBN 978-1-84593-773-7.

- ^ Smith, Kenneth M. (2012-12-02). A Textbook of Plant Virus Diseases. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-16205-0.

- ^ Duong Tan Nhut, Nguyen Thi Doan Tam, Vu Quoc Luan, Nguyen Tri Minh. 2006. Standardization of in vitro Lily (Lilium spp.) plantlets for propagation and bulb formation. Proceedings of International Workshop on Biotechnology in Agriculture, Nong Lam University (NLU), Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, page 134-137. Retrieved January 25, 2014

- ^ Yadav, Rakesh; Yadav, Neha; Pal, Minakshi; Goutam, Umesh (December 2013). "Multiple shoot proliferation, bulblet induction and evaluation of genetic stability in Asiatic hybrid lily (Lilium sp.)". Indian Journal of Plant Physiology. 18 (4): 354–359. Bibcode:2013InJPP..18..354Y. doi:10.1007/s40502-014-0060-4. ISSN 0019-5502. S2CID 17091557.

- ^ Kamenetsky, Rina; Okubo, Hiroshi (2012-09-17). Ornamental Geophytes: From Basic Science to Sustainable Production. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4398-4924-8.

- ^ Hotta Y, Chandley AC, Stern H (September 1977). "Meiotic crossing-over in lily and mouse". Nature. 269 (5625): 240–2. Bibcode:1977Natur.269..240H. doi:10.1038/269240a0. PMID 593319.

- ^ Terasawa M, Shinohara A, Hotta Y, Ogawa H, Ogawa T (April 1995). "Localization of RecA-like recombination proteins on chromosomes of the lily at various meiotic stages". Genes Dev. 9 (8): 925–34. doi:10.1101/gad.9.8.925. PMID 7774810.

- ^ Anderson LK, Offenberg HH, Verkuijlen WM, Heyting C (June 1997). "RecA-like proteins are components of early meiotic nodules in lily". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 94 (13): 6868–73. Bibcode:1997PNAS...94.6868A. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.13.6868. PMC 21251. PMID 11038554.

- ^ Langston CE (January 2002). "Acute renal failure caused by lily ingestion in six cats". J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 220 (1): 49–52, 36. doi:10.2460/javma.2002.220.49. PMID 12680447.

- ^ Hall J (1992). "Nephrotoxicity of Easter Lily (Lilium longiflorum) when ingested by the cat". Proc Annu Meet Am Vet Int Med. 6: 121.

- ^ Volmer P (April 1999). "Easter lily toxicosis in cats" (PDF). Vet Med: 331.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Fitzgerald, Kevin T. (2010). "Lily Toxicity in the Cat". Topics in Companion Animal Medicine. 25 (4): 213–217. doi:10.1053/j.tcam.2010.09.006. ISSN 1938-9736. PMID 21147474.

- ^ "Lily poisoning in cats – Vet Help Direct Blog". 2010-05-02. Archived from the original on 2013-11-02. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- ^ a b Blasdale (1899), p. 21.

- ^ a b c 陈辉; 张秋霞 (2019-08-28). "【药材辨识】百合,你买对了吗?". 搜狐网 (in Chinese). 羊城晚报. Archived from the original on 2020-02-13. Retrieved 2020-01-17.

- ^ "百合属 Lilium". www.iplant.cn. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- ^ "15个百合种和品种的食用性比较研究". Archived from the original on 2014-05-29. Retrieved 2014-05-28.

- ^ "不同食用百合品种在宁波地区引种品比试验". Archived from the original on 2014-02-01.

- ^ 'Batistero' and 'California' among 15 lilies in Beijing,[74] and 'Prato' and 'Small foreigners' among 13 lilies in Ningbo.[75]

- ^ a b Blasdale, Walter Charles (1899). A Description of Some Chinese Vegetable Food Materials and Their Nutritive and Economic Value. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 44. Archived from the original on 2020-09-01. Retrieved 2020-01-13.

- ^ Hemerocallis citrina Archived 2015-07-11 at the Wayback Machine Flora Republicae Popularis Sinicae

- ^ a b "Lily Flowers and Bulbs Used as Food". Bulletin of Miscellaneous Information. 1889 (29). Royal Gardens, Kew: 116–118. 1889. doi:10.2307/4113224. JSTOR 4113224. Archived from the original on 2016-07-30. Retrieved 2020-01-13.

- ^ "《按照传统既是食品又是中药材的物质目录(2013版)》(征求意见稿).doc". Archived from the original on 2014-02-22. Retrieved 2014-01-25.

- ^ 蔡, 月夏. "食用百合鱗莖有機栽培模式之建立" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-02.

- ^ "首頁 / 為民服務 / 常見問題(FAQ)". Hualien District Agricultural Research and Extension Station. Council of Agriculture, Executive Yuan. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014.

- ^ "首頁 / 最新消息 / 本場新聞 / 花蓮、宜蘭生產的有機食用百合深受消費者喜愛". Hualien District Agricultural Research and Extension Station. Council of Agriculture, Executive Yuan. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014.

- ^ "可供食品使用原料彙整一覽表". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 26 January 2014. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ^ Tsuji, Shizuo [in Japanese] (2007). Japanese Cooking: A Simple Art. Kodansha International. p. 74. ISBN 978-4-770-03049-8. Archived from the original on 2020-09-01. Retrieved 2020-01-16.

- ^ Takekawa, Masae; Iizuka, Keiko, eds. (2016). Saishin oishii yasai hyaku shu no jōzu na sodate-kata 最新 おいしい野菜100種のじょうずな育て方. Shufunotomo. p. 146. ISBN 978-4-07-414500-3. Archived from the original on 2020-09-01. Retrieved 2020-01-16.

- ^ "Bon Appetit! Japanese Culture in the Kitchen / A Hot 'pudding', Japanese-Style Chawan-mushi". Nipponia (15). Heibonsha: 30. 2000. Archived from the original on 2020-09-01. Retrieved 2020-01-16.

- ^ Tsuji (2007), pp. 214–215.

- ^ Kingsbury, Noel (2016). Garden Flora: The Natural and Cultural History of the Plants In Your Garden. Timber Press. p. 195. ISBN 978-1-604-69565-6. Archived from the original on 2020-09-01. Retrieved 2020-01-16.

- ^ Kawakami, Kōzō [in Japanese] (2006). Nihon ryōri jibutsu kigen 日本料理事物起源. Iwanami Shoten. pp. 46–47. ISBN 978-4-000-24240-0. Archived from the original on 2020-09-01. Retrieved 2020-01-16.

- ^ Tsuji (2007), pp. 74, 460–461.

- ^ a b Inoue, Yoshiyuki (supervising ed.) (1969). yuri-ne ゆり根 日本食品事典. Ono, Seishi; Sugita, Kōichi; Mori, Masao (edd.). Ishiyaku Shuppan. pp. 307–308. Archived from the original on 2020-09-01. Retrieved 2020-09-01.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Kosaki, Takayuki; Wagner, Walter (2007). Authentic Recipes from Japan. Tuttle. p. 108. ISBN 978-1-4629-0572-0. Archived from the original on 2020-09-01. Retrieved 2020-09-01.

- ^ a b Moriyasu, Tadashi (1971). Nihon meika jiten 日本名菓辞典. Tokyodo Shuppan. p. 378. Archived from the original on 2020-09-01. Retrieved 2020-09-01.

- ^ Shin shikunshi (1901), pp. 133–135 Archived 2020-02-10 at the Wayback Machine; also excerpted in NSJ (1908). p. 2082b Archived 2020-09-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Allegedly the Hamada city version was 90% adulterated with white [Phaseolus vulgaris

- ^ a b Sawa, Fumio (1994). "Yuri" 百合 ゆり. Nihon Dai-hyakka zensho. Vol. 23. Shogakukan. p. 436. ISBN 978-4-09-526001-3. Archived from the original on 2020-09-01. Retrieved 2020-09-01.; also Yuri-yokan Archived 2020-09-01 at the Wayback Machine via kotobank.

- ^ Moriyasu (1971), pp. 34–35.

- ^ a b c d Dai Nihon Nōkai [in Japanese] (1895). Useful Plants of Japan Described and Illustrated. Agricultural Society of Japan. p. 27. Archived from the original on 2020-09-01. Retrieved 2020-01-16.

- ^ Food Safety and Consumer Affairs Bureau, MAFF. "(Q&A) Shokuyō ni suru yurine ni tsuite oshiete kudasai" 食用にするユリネ(ゆり根)について教えてください. Archived from the original on 2013-03-07., citing KNU Publishing Department, Shokuhin zukan

- ^ Gomyō, Toshiharu [in Japanese] (February 2009). "yuri-ne (lily bulb)" ユリネ (百合根). Shokuzai hyakka jiten, an encyclopedia of food ingredients. Kagawa Nutrition University. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04.

- ^ Taira, Hirokazu et al. edd., (2006) Shokuhin zukan, KNU Publishing (女子栄養大学, Joshi Eiyō Daigaku). apud MAFF consumer bureau Q&A.[100] Cf. KNU Prof. Gomyo's online encyclopedia.[101]

- ^ Ministry of Education (MEXT, 2005), Standard Tables of Food Composition in Japan, 5th revised and expanded edition, Appendix 1-6 to Chapter3

- ^ Shin shikunshi (1901), p. 132 Archived 2020-02-10 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Sukashi-yuri すかし‐ゆり【透かし百合】・", Kojien, 4th ed., 1991. "下半各花被片の間に空隙があるところから命名。"

- ^ This species was particularly sought after by high-end kappo (割烹) restaurants, for braising it whole. Shin shikunshi (1901), p. 75.

- ^ Wiersema, John H.; León, Blanca (1999). World Economic Plants: A Standard Reference. CRC Press. pp. 404–405. ISBN 978-0-849-32119-1. Archived from the original on 2020-09-01. Retrieved 2020-01-16.

- ^ "Boreal Forest, Faculty of Natural Resources Management, Lakehead University, Lilium canadense, Canada Lily". Archived from the original on 2017-08-25. Retrieved 2017-08-19.

- ^ Pojar, Jim (2004). Plants of the Pacific Northwest Coast. Edmonton: Lone Pine Publishing. ISBN 978-1-55105-530-5.

- ^ "中国药用植物 (据《中国植物志》全书记载分析而得)". Archived from the original on 2014-02-02. Retrieved 2014-01-25.

- ^ "中国药用植物 (据《中国植物志》全书记载分析而得)". Archived from the original on 2014-02-02. Retrieved 2014-01-25.

- ^ Taiwan Herbal Pharmarcopeia Archived 2015-01-28 at the Wayback Machine Ministry of Health and Welfare

- ^ a b "The Japanese Pharmacopoeia, 17th edition" (PDF). Japanese Ministry of Health. p. 1906. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-01-13. Retrieved 2020-01-13.; index Archived 2014-07-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "백합". Archived from the original on 2016-09-20. Retrieved 2020-09-01.

- ^ "Lilii Bulbus" (PDF) (in Korean). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-02-03. Retrieved 2014-01-25.

- ^ "Symbolism of the Lily – The Flower That is a Part of History". Buzzle. Archived from the original on 2016-11-26. Retrieved 2016-11-26.

- ^ Maser, Verena (2014-08-31). Beautiful and Innocent: Female Same-Sex Intimacy in the Japanese Yuri Genre (PhD thesis). Universität Trier. pp. 3–4. doi:10.25353/ubtr-xxxx-db7c-6ffc. Archived from the original on 2018-11-02. Retrieved 2022-12-17.

- ^ "Yurizoku no Heya". Barazoku (in Japanese): 66–70. November 1976.

- ^ "What is Yuri?". Yuricon. 28 March 2011. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ Welker, James (2008). "Lilies of the Margin: Beautiful Boys and Queer Female Identities in Japan". In Fran Martin; Peter Jackson; Audrey Yue (eds.). AsiaPacifQueer: Rethinking Genders and Sexualities. University of Illinois Press. pp. 46–66. ISBN 978-0-252-07507-0.

- ^ "Gl/백합 만화 추천 10작품". 15 February 2021. Archived from the original on 6 April 2023. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ "這畫面太美我不敢看!女女戀不是禁忌,日本「百合展」呈現女孩間的真實愛戀!". 8 April 2019. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ "Meaning & Symbolism of Lilies". Archived from the original on 2018-04-06. Retrieved 2018-04-06.

- ^ Liberty Times (2015). 魯凱六角星,原民聖花 客庄打碗花,生態指標 (in Chinese). 自由電子報. Archived from the original on 2013-12-02.

- ^ 李子寧 (2023). Lawbubulu: 魯凱的珍寶 [Lawbubulu: Treasures of the Rukai] (in Chinese, English, and Rukai). National Taiwan Museum. pp. 62–3. ISBN 978-986-532-817-7.

- ^ Nugent, M. (2008). Seasonal Flux - Three Flowers for Three Seasons: Seasonal Ritual at Akrotiri. Iris (Journal of the Classical Association of Victoria), 21, 6–7. https://classicsvic.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/nugentvol21.pdf

- ^ Design Research Group (27 June 2007). "A kinder gentler image? Modernism, Tradition and the new Orange Order logo. Reinventing the Orange Order: A superhero for the 21st century". Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- ^ Lemon Lily Festival Archived 2010-07-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Government House Gardens Showcase Western Red Lily". Government of Saskatchewan. 2005-07-21. Archived from the original on 2011-06-11. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- ^ "Saskatchewan's Provincial Flower". Government of Saskatchewan. Archived from the original on 2011-07-28. Retrieved 2008-07-09., designated in 1941.

- ^ "Saskatchewan". Government of Canada. 2013-08-20. Archived from the original on 2015-07-21. Retrieved 2015-07-18.

- Bibliography

- Gao, Yun-Dong; Hohenegger, Markus; Harris, AJ; Zhou, Song-Dong; He, Xing-Jin; Wan, Juan (2012). "A new species in the genus Nomocharis Franchet (Liliaceae): evidence that brings the genus Nomocharis into Lilium". Plant Systematics and Evolution. 298 (1): 69–85. Bibcode:2012PSyEv.298...69G. doi:10.1007/s00606-011-0524-1. ISSN 0378-2697. S2CID 16912824.

- Rønsted, N.; Law, S.; Thornton, H.; Fay, M. F.; Chase, M. W. (2005). "Molecular phylogenetic evidence for the monophyly of Fritillaria and Lilium (Liliaceae; Liliales) and the infrageneric classification of Fritillaria". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 35 (3): 509–527. Bibcode:2005MolPE..35..509R. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2004.12.023. PMID 15878122.

- "Nomocharis", World Checklist of Selected Plant Families, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, archived from the original on 2020-09-01, retrieved 2015-09-14

- "yuri ユリ", in Nihon shakai jii 日本社會事彙 (in Japanese). Vol. 2. Keizai zasshi-sha. 1908. pp. 2077–2083. Archived from the original on 2020-09-01. Retrieved 2020-01-16., digested from Shin shikunshi.

- Seika-en Sanjin 精花園山人 "Hana-yuri 花百合", in Shōkadō Shujin (1901), Shin shikunshi 新四君子 (in Japanese), Tokyo Mita Ikushujyo, pp. 63–140, archived from the original on 2020-02-10, retrieved 2020-01-16

External links

[edit]- The Plant List

- North American Lily Society

- Royal Horticultural Society Lily Group

- 1 2 3 Time-lapse videos

- THE GENUS LILIUM

- "Lilium". The Encyclopedia of Life.

- Lily perenialization, Flower Bulb Research Program, Department of Horticulture, Cornell University

- Crossing polygon of the genus Lilium.

- Bulb flower production; Lilies, International Flower Bulb Centre

- Lily Picture Book, International Flower Bulb Centre