Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Video games and Linux

View on Wikipedia| Video games |

|---|

This article may contain excessive or inappropriate references to self-published sources. (May 2023) |

Linux-based operating systems can be used for playing video games. Because fewer games natively support the Linux kernel than Windows, various software has been made to run Windows games, software, and programs, such as Wine, Cedega, DXVK, and Proton, and managers such as Lutris and PlayOnLinux. The Linux gaming community has a presence on the internet with users who attempt to run games that are not officially supported on Linux.

History

[edit]

Linux gaming started largely as an extension of the already present Unix gaming scene,[1] which dates back to that system's conception in 1969 with the game Space Travel[2][3][self-published source?] and the first edition in 1971,[4] with both systems sharing many similar titles.[5][self-published source?][6] These games were mostly either arcade and parlour type games or text adventures using libraries like curses.[7][8] A notable example of this are the "BSD Games", a collection of interactive fiction and other text-mode amusements.[9][10] The free software philosophy and open-source methodology which drove the development of the operating system in general also spawned the creation of various early free games.[11][12]

Popular early titles included Netrek and the various XAsteroids, XBattle, XBill, XBoing, X-Bomber, XConq, XDigger, XEmeraldia, XEvil, XGalaga, XGammon, XLander, XLife, XMahjong, XMine, XSoldier, XPilot, XRobots, XRubiks, XShogi, XScavenger, XTris, XTron, XTic and XTux games using the X Window System.[13][14] Other games targeted or also supported the SVGAlib library allowing them to run without a windowing system,[15] such as LinCity, Maelstrom, Sasteroids,[16] and SABRE.[17] The General Graphics Interface was also used[18] for games like U.R.B.A.N The Cyborg Project[19] and Dave Gnukem[20] ported from MS-DOS. As the operating system itself grew and expanded, the amount of free and open-source games also increased in scale and complexity, with both clones of historically popular releases beginning with BZFlag, LinCity, and Freeciv,[21] as well as original creations such as Rocks'n'Diamonds, Cube, The Battle for Wesnoth, and Tux Racer.[22]

1994

[edit]

The beginning of Linux as a gaming platform for commercial video games is widely credited to have begun in 1994 when Dave D. Taylor ported the game Doom to Linux, as well as many other systems, during his spare time.[23][24] Shareware copies of the game were included on various Linux discs,[25] including those packed in with reference books.[26][27][28]

Ancient Domains of Mystery was also released for Linux in 1994 by Thomas Biskup, building on the roguelike legacy of games such as Moria and its descendent Angband, but more specifically Hack and NetHack.

1995

[edit]From there Taylor would also help found the development studio Crack dot Com, which released the video game Abuse,[29] with the game's Linux port even being distributed by Linux vendors Red Hat[30] and Caldera.[31] The studio's never finished Golgotha was also slated to be released by Red Hat in box.[32]

In 1991 DUX Software contracted Don Hopkins to port SimCity to Unix,[33] which he ported to Linux in 1995 and eventually released as open source for the OLPC XO Laptop.[34]

A website called The Linux Game Tome, also known as HappyPenguin after its URL, was begun by Tessa Lau in 1995 to catalogue games created for or ported to Linux from the SunSITE game directories as well as other classic X11 games for a collection of just over 100 titles.[35]

1996–1997

[edit]id Software, the original developers of Doom, also continued to release their products for Linux. Their game Quake was ported to Linux via X11 in 1996, once again by Dave D. Taylor working in his free time.[36][37] An SVGALib version was also later produced by Greg Alexander in 1997 using recently leaked source code, but was later mainlined by id.[38] Later id products continued to be ported by Zoid Kirsch[39] and Timothee Besset,[40] a practice that continued until the studio's acquisition by ZeniMax Media in 2009.[41] Initially, Zoid Kirsch was responsible for maintaining the Linux version of Quake and porting QuakeWorld to Linux.

Inner Worlds was released for and developed on Linux.[42] The UNIX Book of Games, a 1996 publication by Janice Winsor, described various games with an accompanying CD-ROM containing executables and source code for Linux and SCO Unix.[43]

1998

[edit]

The Linux Game Tome was taken over by Bob Zimbinski in 1998 eventually growing to over 2000 entries, sponsored by retailer Penguin Computing and later LGP until it went down in 2013, although mirrors still exist.[44][45]

The site LinuxGames covered news and commentary from November 1998 until its host Atomicgamer went down in 2015.[46][47] It was established by Marvin Malkowski, head of the Telefragged gaming network, alongside Al Koskelin and Dustin Reyes;[48] Reyes died 8 August 2023.[49]

Zoid Kirsch from id Software ported Quake II to Linux. Two programmers from Origin ported Ultima Online to Linux and MP Entertainment released an adventure game Hopkins FBI for Linux[50][51]

On 9 November 1998, a new software firm called Loki Software was founded by Scott Draeker, a former lawyer who became interested in porting games to Linux after being introduced to the system through his work as a software licensing attorney.[52] Loki, although a commercial failure, is credited with the birth of the modern Linux game industry.[53] Loki developed several free software tools, such as the Loki installer (also known as Loki Setup),[54] and supported the development of the Simple DirectMedia Layer,[55] as well as starting the OpenAL audio library project.[56][57] These are still often credited as being the cornerstones of Linux game development.[58] They were also responsible for bringing nineteen high-profile games to the platform before its closure in 2002.

1999

[edit]Loki published Civilization: Call to Power, Eric's Ultimate Solitaire, Heretic II, Heroes of Might and Magic III, Railroad Tycoon II: Gold Edition, Quake III: Arena, and Unreal Tournament for Linux.[59]

Loki's initial success also attracted other firms to invest in the Linux gaming market, such as Tribsoft, Hyperion Entertainment, Macmillan Digital Publishing USA, Titan Computer, Xatrix Entertainment, Philos Laboratories, and Vicarious Visions.[60]

The ports of Quake and Quake II were released physically by Macmillan Computer Publishing USA,[61] while Quake III was released for Linux by Loki Software.[62] Red Hat had previously passed on publishing Quake for Linux, since it was not open-source at the time.[63]

Philos Laboratories released a Linux version of Theocracy on the retail disk. Ryan "Ridah" Feltrin from Xatrix Entertainment released a Linux version of Kingpin: Life of Crime.

BlackHoleSun Software released Krilo and Futureware 2001 released a trading simulation Würstelstand for Linux.[64]

The Indrema Entertainment System (also known as the L600) was also in development since 1999 as a Linux based game console and digital media player,[65][66][67] but production halted in 2001 due to a lack of investment,[68][69] although the TuxBox project attempted a continuation.[70]

2000

[edit]Loki published Descent 3, Heavy Gear II, SimCity 3000, and Soldier of Fortune for Linux. They also released the expansion Descent 3: Mercenary as the downloadable Linux installer.[59]

Hyperion Entertainment ported Sin to Linux published by Titan Computer. Vicarious Visions ported the space-flight game Terminus to Linux. Mountain King Studios released a port of Raptor: Call of the Shadows and CipSoft published the Linux client of Tibia.[71]

Boutell.com ported Exile III: Ruined World to Linux, which was a game created by Spiderweb Software.

During this time Michael Simms founded Tux Games, one of the first online Linux game retailers,[72] later followed by Fun 4 Tux,[73] Wupra,[74] ixsoft, and LinuxPusher.[75]

The period also saw a number of commercial compilations released,[76] such as 100 Great Linux Games by Global Star Software,[77] Linux Games by Walnut Creek CDROM,[78][79] Linux Games++ by Pacific Hitech,[80][81] Linux Cubed Series 8 LINUX Games by Omeron Systems,[82] Best Linux Games by SOT Finnish Software Engineering,[83][84][85] LinuxCenter Games Collection,[86] Linux Games & Entertainment for X Windows by Hemming,[87][88] Linux Spiele & Games by more software,[89] Linux Spiele by Franzis Verlag,[90] and play it! Linux: Die Spielesammlung by S.A.D. Software.[91]

Numerous Linux distributions and collections packed in Loki games and demos,[92] including Red Hat Linux,[93] Corel Linux and WordPerfect Office,[94][95] and the complete Eric's Ultimate Solitaire bundled with PowerPlant by TheKompany.[96] Easy Linux 2000 similarly bundled in a copy of the Linux version of Hopkins FBI.[97]

2001

[edit]Loki published Heavy Metal: F.A.K.K.², Kohan: Immortal Sovereigns, Mindrover: The Europa Project, Myth II: Soulblighter, Postal Plus, Rune, Rune: Halls of Valhalla, Sid Meier's Alpha Centauri, and Tribes 2 for Linux.[59]

Linux Game Publishing was founded in 2001 in response to the impending demise of Loki. Creature Labs ported Creatures: Internet Edition to Linux, which was published by LGP.

Hyperion Entertainment ported Shogo: Mobile Armor Division to Linux, and Tribsoft created a Linux version of Jagged Alliance 2, both published by Titan Computer.

Illwinter Game Design released Conquest of Elysium II and Dominions: Priests, Prophets & Pretenders for Linux. Introversion Software released Uplink for Linux.

BlackHoleSun Software released Bunnies, and worked on Atlantis: The Underwater City – Interactive Storybook published by Sterling Entertainment.[98]

GLAMUS GmbH released a Linux version of their game Mobility and Oliver Hamann released the driving game Odyssey by Car.[99]

Small Rockets published Small Rockets BackGammon, Small Rockets Mah Jongg, and Small Rockets Poker for Linux.[citation needed]

The company TransGaming marketed as a monthly subscription its own proprietary fork of Wine called WineX in October 2001, later renamed Cedega in 2004 and discontinued in 2011, which aimed for greater compatibility with Microsoft Windows games. A special Gaming Edition of Mandrake Linux 8.1 was released that featured WineX packed in with The Sims.[100] The fact that the fork of Wine did not release source back to the main project was also a point of contention, despite promises to release code after achieving a set number of subscribers.[101][102]

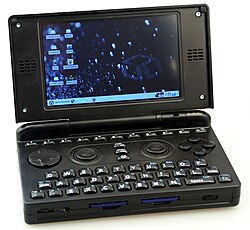

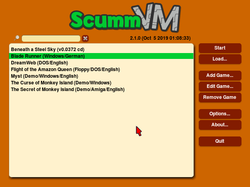

The release of ScummVM in 2001,[103] Dosbox in 2002,[104] as well as video game console emulators like MAME from 1997 and released as open source in 2016, helped make Linux a viable platform for retro gaming (facilitated by the RetroArch frontend since 2010).[105][106] This is especially the case for the GP2X series of handheld game consoles by GamePark Holdings in addition to the community driven Pandora and DragonBox Pyra. Dedicated emulation setups are also built on single-board computers like the Raspberry Pi released in 2012, which are most often Linux based including with Raspberry Pi OS.[107] Wine is also useful for running older Windows games,[108] including 16-bit and even some 32-bit applications that no longer work on modern 64-bit Windows.[109] The Sharp Zaurus personal data assistants adopted a Linux derived system called OpenZaurus, which attracted its own gaming scene.[110][111] This was also the case with the Agenda VR3, advertised as the first "pure Linux PDA".[112][113]

2002

[edit]

After Loki's closure, the Linux game market experienced some changes.[114] Although some new firms, such as Linux Game Publishing and RuneSoft, would largely continue the role of a standard porting house,[115] the focus began to change with Linux game proponents encouraging game developers to port their game products themselves or through individual contractors.[116] Influential to this was Ryan C. Gordon, a former Loki employee who would over the next decade port several game titles to multiple platforms, including Linux.[117]

Ryan ported America's Army, Candy Cruncher, Serious Sam: The First Encounter, and Unreal Tournament 2003 to Linux.[118][119][120]

Linux Game Publishing had initially tried to pick up the support rights to many of Loki's titles, but in the end it was only able to acquire the rights to MindRover: The Europa Project. They released the updated version of Mindrover and its downloadable update for owners of the old Loki version.[121]

Return to Castle Wolfenstein was released for Linux and with the Linux port done in-house by Timothee Besset[122]

Chronic logic released Bridge Construction Set and Triptych for Linux.

Sunspire Studios released in retail commercial expansion of the game titled Tux Racer.[123]

2003

[edit]Ryan ported Devastation, Medal of Honor Allied Assault, and Serious Sam: The Second Encounter to Linux.[124]

LGP took interest in publishing Pyrogon games on physical CDs and they released Candy Cruncher.[125] Mathieu Pinard from Tribsoft got LGP in contact with Cyberlore to save the Linux port of Majesty because Titan Computer get out of Linux publishing. This turn of events helped LGP to release a Majesty for Linux after Pinard closed his company in 2002.[126]

Timothee Bessett from id Software ported Wolfenstein: Enemy Territory to Linux.[127]

Around this time many companies, starting with id Software, also began to release legacy source code leading to a proliferation of source ports of older games to Linux and other systems.[128] This also helped expand the already existing free and open-source gaming scene, especially with regards to the creation of free first person shooters.[129] In addition, numerous game engine recreations have been produced to varying levels of accuracy using reverse engineering or underlying engine code supporting the original game files including on Linux and other niche systems.[130][131]

2004

[edit]Ryan ported Unreal Tournament 2004 to Linux for Epic Games[132] and Timothee Bessett from id Software ported Doom 3 to Linux.[133]

David Hedbor, founder and main programmer of Eon Games ported NingPo MahJong and Hyperspace Delivery Boy! to Linux, which later were published by LGP.[134]

2005–2007

[edit]Ryan ported Postal²: Share the Pain to Linux published by LGP.[135]

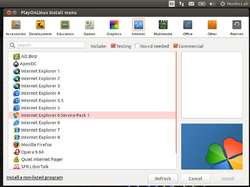

CodeWeavers offered an enhanced version of Wine called CrossOver Games.[136][137] The reliance on such compatibility layers remains controversial with concerns that it hinders growth in native development,[138][139] although this approach was defended based on Loki's demise.[140][141] PlayOnLinux, established in 2007, provides a community alternative,[142] with various guides being written on how to get games to run through Wine.[143]

2008–2011

[edit]- Windows (61.9%)

- Mac (21.6%)

- Linux (16.5%)

- Windows (52.1%)

- Mac (23.0%)

- Linux (24.9%)

The Linux gaming market also started to experience some growth towards the end of the decade with the rise of independent video game development,[145] with many "indie" developers favouring support for multiple platforms.[146] The Humble Indie Bundle initiatives inaugurated in 2010 helped to formally demonstrate this trend,[147] with Linux users representing a sizable population of their purchase base, as well as consistently being the most financially generous in terms of actual money spent.[148][149] The Humble Indie Bundle V in 2012 faced controversy for featuring a Wine-based release of Limbo prepared by CodeWeavers,[150] while a native version was later released in 2014.[151] Humble eventually began offering Windows-only games in their bundles and on their store.[152][153]

In 2009, the small indie game company Entourev LLC published Voltley to Linux which is the first commercial exclusive game for this operating system.[154][155] In the same year, LGP released Shadowgrounds which was the first commercial game for Linux using the Nvidia PhysX middleware.[156] The GamingOnLinux website was launched on 4 July 2009, and eventually succeeded LinuxGames as the main source of news and commentary.[157]

The release of a Linux version of Desura in 2011,[158] a digital distribution platform with a primary focus on small independent developers, was heralded by several commentators as an important step to greater acknowledgement of Linux as a gaming platform.[145][159][160] Shortly before this, Canonical launched the Ubuntu Software Center which also sold digital games.[161] The digital store Gameolith also launched in 2011 focused principally on Linux before expanding in 2012 and closing in 2014.[162][163]

2012–2016

[edit]In July 2012, game developer and content distributor Valve announced a port of their Source engine for Linux as well as stating their intention to release their Steam digital distribution service for Linux.[164][165][166] The potential availability of a Linux Steam client had already attracted other developers to consider porting their titles to Linux,[160][167][168][169] including previously Mac OS only porting houses such as Aspyr Media and Feral Interactive.[170]

In November 2012, Unity Technologies ported their Unity engine and game creation system to Linux starting with version 4. All of the games created with the Unity engine can now be ported to Linux easily.[171]

In September 2013, Valve announced that they were releasing a gaming oriented Linux based operating system called SteamOS with Valve saying they had "come to the conclusion that the environment best suited to delivering value to customers is an operating system built around Steam itself."[160][172] This was used for their Steam Machine platform released on 10 November 2015, and discontinued in 2018.[173]

In March 2014, GOG.com announced they would begin to support Linux titles on their DRM free store starting the same year, after previously stating they would not be able due to too many distributions.[174] GOG.com began their initial roll out on 24 July 2014, by offering 50 Linux supporting titles, including several new to the platform.[175]

Despite previous statements, GOG have confirmed they have no plans to port their Galaxy client to Linux.[176] The free software Lutris started in 2010,[177] GameHub from 2019,[178] MiniGalaxy from 2020,[179] and the Heroic Games Launcher from 2021,[180] offer support for GOG as well as the Epic Games Store, Ubisoft Connect and Origin.

In March and April 2014, two major developers Epic Games and Crytek announced Linux support for their next generation engines Unreal Engine 4 and CryEngine respectively.[181][182]

Towards the end of 2014, the game host itch.io announced that Linux would be supported with their developing open source game client.[183] This was fully launched simultaneously on Windows, Mac OS X and Linux on 15 December 2015.[184] The service had supported Linux since it was first unveiled on 3 March 2013, with creator Leaf Corcoran personally a Linux user.[185] The similar Game Jolt service also supports Linux and has an open source client released on 13 January 2016.[186][187] GamersGate also sells games for Linux.[188][189]

In 2015, started OpenXRay project — an improved version of the X-Ray Engine, the game engine used in the world-famous S.T.A.L.K.E.R, with Linux and macOS support.[190][191][192][193]

On July 2015, LinuxGames website shut down.[194]

2017–present

[edit]

On 22 August 2018, Valve released their fork of Wine called Proton, aimed at gaming.[195] It features some improvements over the vanilla Wine such as Vulkan-based DirectX 11 implementation, Steam integration, better full screen and game controller support and improved performance for multi-threaded games.[196] It has since grown to include support for DirectX 9[197] and DirectX 12[198] over Vulkan. The itch.io app added its own Wine integration in June 2020,[199] while Lutris and PlayOnLinux are long-standing independent solutions for compatibility wrappers.[200][201]

As with Wine and Cedega in the past, concerns have been raised over whether Proton hinders native development more than it encourages use of the platform.[202][203] Prodeus dropped native support in favour of Proton shortly before final release[204] and Arcen Games cancelled planned native support for Heart of the Machine.[205] Valve has expressed no preference over Proton or native ports among developers.[206]

On 25 February 2022, Valve released Steam Deck, a handheld game console running SteamOS 3.0.[207][208] The deployment of Proton and other design decisions were based on the limited response to their previous Steam Machines.[209] Linux was also used as a base for several nostalgia consoles, including the Neo Geo X,[210] NES Classic Edition,[211] Super NES Classic Edition,[212] Sega Genesis Mini,[213] Intellivision Amico,[214] Lichee Pocket 4A,[215] and the Atari VCS.[216] It also powers the more general Polymega,[217] Anbernic RG351 and 5G552, as well as the Game Gadget,[218] Evercade, VS, EXP and Super Pocket retrogaming consoles by Blaze Entertainment.[219][220]

As of early 2023, the retro game store Zoom Platform was enhancing Linux support on their available titles.[221]

Commercial games for non-x86 instruction sets

[edit]

Some companies ported games to Linux running on instruction sets other than x86, such as Alpha, PowerPC, Sparc, MIPS or ARM.

Loki Entertainment Software ported Civilization: Call to Power, Eric's Ultimate Solitaire, Heroes of Might and Magic III, Myth II: Soulblighter, Railroad Tycoon II Gold Edition and Sid Meier's Alpha Centauri with Alien Crossfire expansion pack to Linux PowerPC.[222] They also ported Civilization: Call to Power, Eric's Ultimate Solitaire, Sid Meier's Alpha Centauri with Alien Crossfire expansion pack to Linux Alpha and Civilization: Call to Power, Eric's Ultimate Solitaire to Linux SPARC.[223]

Linux Game Publishing published Candy Cruncher, Majesty Gold, NingPo MahJong and Soul Ride to Linux PowerPC. They also ported Candy Cruncher, Soul Ride to Linux SPARC and Soul Ride to Linux Alpha.[224][225]

Illwinter Game Design ported Dominions: Priests, Prophets and Pretenders, Dominions II: The Ascension Wars and Dominions 3 to Linux PowerPC, as well as Conquest of Elysium 3, Dominions 4: Thrones of Ascension to Raspberry Pi.[226]

Hyperion Entertainment ported Sin to Linux PowerPC published by Titan Computer[227] and Gorky 17 to Linux PowerPC which later was published by LGP.[228]

Runesoft hired Gunnar von Boehn which ported Robin Hood – The Legend of Sherwood to Linux PowerPC.[229] Later Runesoft ported Airline Tycoon Deluxe to Raspberry Pi was running Debian GNU/Linux.[citation needed]

Iain McLeod ported Spheres of Chaos to Linux on the PlayStation 2 consoles and later re-released it as a freeware game.

Market share

[edit]The Steam Hardware Survey reports that as of January 2024, 2% of users are using some form of Linux as their platform's primary operating system.[230] The Unity game engine used to[231] make their statistics available and in March 2016 reported that Linux users accounted for 0.4% of players.[232] In 2010, in the first Humble Bundle sales, Linux accounted for 18% of purchases.[233]

Supported hardware

[edit]

Linux as a gaming platform can also refer to operating systems based on the Linux kernel and specifically designed for the sole purpose of gaming. Examples are SteamOS, which is an operating system for Steam Machines, Steam Deck and general computers, video game consoles built from components found in the classical home computer, (embedded) operating systems like Tizen and Pandora, and handheld game consoles like GP2X, and Neo Geo X. The Nvidia Shield runs Android as an operating system, which is based on a modified Linux kernel.[citation needed]

The open source design of the Linux software platform allows the operating system to be compatible with various computer instruction sets and many peripherals, such as game controllers and head-mounted displays. As an example, HTC Vive, which is a virtual reality head-mounted display, supports the Linux gaming platform.[citation needed]

Performance

[edit]In 2013, tests by Phoronix showed real-world performance of games on Linux with proprietary Nvidia and AMD drivers were mostly comparable to results on Windows 8.1.[234] Phoronix found similar results in 2015,[235] though Ars Technica described a 20% performance drop with Linux drivers.[236]

Software architecture

[edit]An operating system based on the Linux kernel and customized specifically for gaming, could adopt the vanilla Linux kernel with only little changes, or—like the Android operating system—be based on a relative extensively modified Linux kernel. It could adopt GNU C Library or Bionic or something like it. The entire middleware or parts of it, could very well be closed-source and proprietary software; the same is true for the video games. There are free and open-source video games available for the Linux operating system, as well as proprietary ones.[citation needed]

Linux kernel

[edit]The subsystems already mainlined and available in the Linux kernel are most probably performant enough so to not impede the gaming experience in any way,[citation needed] however additional software is available, such as e.g. the Brain Fuck Scheduler (a process scheduler) or the Budget Fair Queueing (BFQ) scheduler (an I/O scheduler).[237]

Similar to the way the Linux kernel can be, for example, adapted to run better on supercomputers, there are adaptations targeted at improving the performance of games. A project concerning itself with this issue is called Liquorix.[238][239]

Available software for video game designers

[edit]Game creation systems

[edit]Several game creation systems can be run on Linux, such as Game Editor, GDevelop, Construct and Stencyl, as well as beta versions of GameMaker.[240] A Linux version of Clickteam Fusion 3 was mentioned, but has yet to be released.[241] The Godot, Defold, and Solar2D game engines also supports creating games on Linux,[242] as do the commercial UnrealEd[243] and Unity Editor,[244][245] The visual programming environments Snap!, Scratch 1.X[246] and Tynker are Linux compatible. Enterbrain's RPG Maker MV was released for Linux.[247] In addition, open-source, cross-platform clones of the RPG Maker series exist such as Open RPG Maker, MKXP and EasyRPG,[248] as well as the similar OHRRPGCE and Solarus.[249] The Adventure Game Studio editor is not yet ported to Linux, although games made in it are compatible, and the Wintermute and SLUDGE[250] adventure game engines are available. ZGameEditor,[251] Novashell,[252] GB Studio,[253] and the ZZT inspired MegaZeux[254] are also options. Versions of Mugen were made available for Linux,[255] and open-source re-implementations such as IKEMEN Go are compatible.[256] The JavaScript based Ct.js[257] Pixelbox.js,[258] and Superpowers[259] are also options.

Level editors

[edit]Various level editors exist for Linux, such as wxqoole, GtkRadiant, TrenchBroom[260][261] and J.A.C.K.[262] for the id Tech engines and related, Eureka,[263] SLADE[264] and ReDoomEd[265] for the Doom engine, and the general purpose tile map editors LDtk,[266] Ogmo,[267] and Tiled.[268]

Debuggers

[edit]Several game development tools have been available for Linux, including GNU Debugger, LLDB, Valgrind, glslang and others. VOGL, a debugger for OpenGL was released on 12 March 2014.

Available interfaces and SDKs

[edit]There are multiple interfaces and Software Development Kits available for Linux, and almost all of them are cross-platform. Most are free and open-source software subject to the terms of the zlib License, making it possible to static link against them from fully closed-source proprietary software. One difficulty due to this abundance of interfaces, is the difficulty for programmers to choose the best suitable audio API for their purpose. The main developer of the PulseAudio project, Lennart Poettering, commented on this issue.[269] Physics engines, audio libraries, that are available as modules for game engines, have been available for Linux for a long time.[time needed][citation needed]

The book Programming Linux Games covers a couple of the available APIs suited for video game development for Linux, while The Linux Programming Interface covers the Linux kernel interfaces in much greater detail.

| Library | License | in | Language bindings | Back-ends | Description | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Icon | Name | Official | 3rd-party | Linux | Windows | OS X | Other | |||

| Allegro | zlib License | C | Yes | Yes | Yes | Android, iOS | ||||

| ClanLib | zlib License | C++ | Python, Lua, Ruby | Yes | Yes | — | — | |||

| GLFW | zlib License | C | — | Ada, C#, Common Lisp, D, Go, Haskell, Java, Python, Rebol, Red, Ruby, Rust | Yes | Yes | Yes | a small C library to create and manage windows with OpenGL contexts, enumerate monitors and video modes, and handle input | ||

| Grapple | LGPL-2.1+ | C | Yes | Yes | Yes | free software package for adding multiplayer support | ||||

| Nvidia GameWorks | Proprietary | Unknown | WIP | Yes | — | — | As the result of their cooperation with Valve, Nvidia announced a Linux port of GameWorks.[270] As of June 2014, PhysX, and OptiX have been available for Linux for some time. | |||

| OpenPlay | APSL | C | Yes | Yes | Yes | — | networking library authored by Apple Inc. | |||

| Pygame | LGPL-2.1 | Python | Yes | Yes | Yes | build over SDL | ||||

| RakNet | 3-clause BSD | C++ | C++, C# | — | Yes | Yes | Yes | PlayStation 3, iOS, … | game network engine for multi-player | |

| SDL | zlib License | C | C | C#, Pascal, Python, Gambas | EGL, Xlib, GLX? | GDI, Direct3D | Quartz, Core OpenGL? | PSP-stuff | a low-level cross-platform abstraction layer | |

| SFML | zlib License | C++ | C, D, Python, Ruby, OCaml, .Net, Go | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| wxWidgets | LGPL-like | C++ | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||

Available middleware

[edit]Beside majority of the software which acts as an interface to various subsystems of the operating system, there is also software which can be simply described as middleware. A multitude of companies exist worldwide, whose main or only product is software that is meant to be licensed and integrated into a game engine. Their primary target is the video game industry, but the film industry also uses such software for special effects. Some very few well known examples are

- classical physics: Havok, Newton Game Dynamics and PhysX

- audio: Audiokinetic Wwise, FMOD

- other: SpeedTree

A significant share of the available middleware already runs natively on Linux, only a very few run exclusively on Linux.

Available IDEs and source code editors

[edit]Numerous source code editors and IDEs are available for Linux, among which are Visual Studio Code, Sublime Text, Code::Blocks, Qt Creator, Emacs, or Vim.

Multi-monitor

[edit]A multi-monitor setup is supported on Linux at least by AMD Eyefinity & AMD Catalyst, Xinerama and RandR on both X11 and Wayland. Serious Sam 3: BFE is one example of a game that runs natively on Linux and supports very high resolutions and is validated by AMD to support their Eyefinity.[271] Civilization V is another example, it even runs on a "Kaveri" desktop APU in 3x1 portrait mode.[272]

Voice over IP

[edit]The specifications of the Mumble protocol are freely available and there are BSD-licensed implementations for both servers and clients. The positional audio API of Mumble is supported by e.g. Cube 2: Sauerbraten.

Wine

[edit]

Wine is a compatibility layer that provides binary compatibility and makes it possible to run software, that was written and compiled for Microsoft Windows, on Linux. The Wine project hosts a user-submitted application database (known as Wine AppDB) that lists programs and games along with ratings and reviews which detail how well they run with Wine. Wine AppDB also has a commenting system, which often includes instructions on how to modify a system to run a certain game which cannot run on a normal or default configuration. Many games are rated as running flawlessly, and there are also many other games that can be run with varying degrees of success. The use of Wine for gaming has proved controversial in the Linux community as some feel it is preventing, or at least hindering, the further growth of native gaming on the platform.[273][274]

Emulators

[edit]

There are numerous emulators for Linux. There are also APIs, virtual machines, and machine emulators that provide binary compatibility:

- Anbox and Waydroid for the Android operating system;

- Basilisk II for the 68040 Mac;

- DOSBox and DOSEMU for MS-DOS and compatibles;

- DeSmuME and melonDS for the Nintendo DS;

- Dolphin for the GameCube, Wii, and the Triforce;

- FCEUX, Nestopia and TuxNES for the Nintendo Entertainment System;

- Flashpoint for Adobe Flash;

- Frotz for Z-Machine text adventures;

- Fuse for the Sinclair ZX Spectrum;

- Hatari for the Atari ST, STe, TT and Falcon;

- gnuboy for the Nintendo Game Boy and Game Boy Color;

- MAME for arcade games (and previously MESS for multiple hardware platforms);

- Mednafen and Xe emulating multiple hardware platforms including some of the above;

- Mupen64Plus and the no longer actively developed original Mupen64 for the Nintendo 64;

- PCSX-Reloaded, pSX and the Linux port of ePSXe for the PlayStation;

- Neko Project for the NEC PC-9801;

- PCSX2 for the PlayStation 2;

- PPSSPP for the PlayStation Portable;

- ScummVM for LucasArts and various other adventure games;

- SheepShaver for the PowerPC Macintosh;

- Snes9x, higan and ZSNES for the Super NES;

- Stella for the Atari 2600;

- UAE for the Amiga;

- VICE for the Commodore 64, 128, VIC-20, Plus/4 and PET;

- VisualBoyAdvance, mGBA and Boycott Advance for the Game Boy Advance;

- Mini vMac and the no longer actively developed original vMac for the 680x0 Macintosh;

Linux homebrew on consoles

[edit]Linux has been ported to several game consoles, including the Xbox, PlayStation 2, PlayStation 3, PlayStation 4,[275] GameCube,[276] and Wii which allows game developers without an expensive game development kit to access console hardware. Several gaming peripherals also work with Linux.[277][278]

Types of Linux gaming

[edit]Linux gaming can be divided into a number of sub-categories.[279][280][281]

Libre gaming

[edit]Libre gaming is a form of Linux gaming that emphasizes libre software, which often includes levels and assets as well as code.[282][self-published source?][283][irrelevant citation]

Native gaming

[edit]Native gaming is a form of Linux gaming that emphasizes using only native games or ports and not using emulators or compatibility layers.[273][139][284][285]

DRM-free gaming

[edit]DRM-free gaming is a form of Linux gaming that emphasizes boycotting DRM technologies. This can include buying games from GOG.com, certain Humble Bundles or itch.io and avoiding Steam and similar services.[286][287]

Terminal gaming

[edit]Terminal gaming is the playing of text-based games from within a console,[288] often programmed within Bash or using libraries such as ncurses.[289][290]

Retro gaming

[edit]Retrogaming is the playing of older games[291] using emulators such as MAME or Dosbox,[292] compatibility layers such as Wine and Proton,[293] engine reimplementations and source ports,[294] or even older Linux distributions (including live CDs and live USB, or virtual machines),[295][296] original binaries,[297] and period hardware.[298]

Live gaming

[edit]A number of games can be played from live distributions such as Knoppix, allowing easy access for users unwilling to fully commit to Linux.[299] Certain live distros have specially targeted gamers, such as SuperGamer and Linux-Gamers.[300][301]

Browser gaming

[edit]Browser gaming is the act of playing online games through a web browser,[302] which has the advantage of largely being platform independent.[303][304] The same largely applies to social network games hosted on social media sites.[305] Older games were largely based on Adobe Flash,[306] while modern ones are mostly HTML5.[307]

Cloud gaming

[edit]Cloud gaming is the streaming of games from a central server onto a desktop client.[308] This is another way to play games on Linux that are not natively supported,[309][310] although some cloud services, such as the erstwhile Google Stadia,[311][312] are hosted on Linux[313][314] and Android servers.[315] GamingAnywhere is an open source implementation.[316]

On Windows

[edit]Although less exploited than the reverse,[317] as few programs are Linux exclusive,[318] support does exist for running Linux binaries from Windows.[319][320] The Windows Subsystem for Linux allows the running of both command line[321][322] and graphical Linux applications[323] from Windows 10 and Windows 11.[324] An earlier implementation is Cygwin,[325] started by Cygnus Solutions and later maintained by Red Hat,[326] although it has limited hardware access[327] and required adaptation.[328] The use of Wine can even allow for the running of Windows games on Linux from Windows.[citation needed] The LibTAS library for tool assisted speedruns currently recommends WSL to run on Windows.[329] Naughty Dog meanwhile have used Cygwin to run old command-line tools for use in their game development,[330] which is a broader use for the platform.[331] As with running Windows applications on Linux, there is controversy over whether running Linux applications on Windows will dilute interest in Linux as distinct platform,[332] though it has speciality uses.[333]

Android gaming

[edit]Originally derived from Linux, the Android mobile operating system has a distinct and popular gaming ecosystem.[334] It has also been used as the base for several game consoles, such as the Nvidia Shield Portable and the Ouya.[335] Popular games include Pokémon Go, Genshin Impact, League of Legends: Wild Rift, Dead Cells and Call of Duty: Mobile.[336] Certain games, such as Minecraft, Stardew Valley, and Papers Please, are available for both Android and desktop Linux.[337]

ChromeOS gaming

[edit]ChromeOS is another Linux derived operating system by Google for its Chromebooks,[338] and it too has a dedicated gaming ecosystem.[339][340] Partly owing to a lack of high end graphics hardware,[341][342] it is especially oriented towards cloud gaming[343] via services like GeForce Now and Xbox Cloud Gaming,[344][345] with models featuring Nvidia GPUs ultimately being cancelled.[346] Numerous games for Android have also been made compatible with ChromeOS,[347][348] as well as a standard Linux games,[349][350][351] Windows games via Wine or Proton,[352][353][354] and with browser games also being popular.[355] A version of Steam has been in development for ChromeOS,[356] with third party launchers also available such as the Heroic Games Launcher for the Epic Games Store.[357] Popular titles include Among Us, Genshin Impact, Alto's Odyssey, Roblox, and Fortnite.[358][359][360][361] Skepticism remains for using ChromeOS and Chromebooks as gaming machines.[362][363][364] In August 2025, Google announced that they will end Steam for Chromebook support in 2026.[365]

BSD gaming

[edit]Owing to a common Unix-like heritage and free software ethos, many games for Linux are also ported to BSD variants[366] or can be run using compatibility layers such as Linuxulator.[367] BSDi had partnered with Loki Software to ensure its Linux ports ran on FreeBSD.[368] The Mizutamari launcher exists to facilitate running Windows games through Wine,[369] which can still be used standalone.[370] A 2011 benchmark by Phoronix even found certain speed advantages over running games on Linux itself, comparing PC-BSD 8.2 to Ubuntu 11.04.[371] Most BSD systems come with the same pack in desktop games as Linux.[372] The permissive licensing of BSD has also lead to its inclusion in the system software of several game consoles, such as the Sony PlayStation line[373][374] and the Nintendo Switch.[375]

OpenHarmony gaming

[edit]HarmonyOS with custom kernel[376] and OpenHarmony-Oniro based operating systems distros[377] of these newer platforms has a dedicated gaming ecosystem with compatibilities with third-party Linux libraries by developers on Linux kernel subsystem such as musl-libc of C standard library that targets the Linux syscall and POSIX APIs compatibility for native compatible games as well as limited virtual machines such as Android-based sandboxed ones.[378][379]

Unix gaming

[edit]A further niche exists for running games, either through ports or lxrun,[380] on Solaris[381] and derivatives such as OpenIndiana,[382] Darwin distributions such as PureDarwin,[383] Coherent,[384] SerenityOS,[385][386] Redox OS,[387][388] ToaruOS,[389] Xv6,[390] Fiwix,[391] or on Minix[392] and Hurd based systems.[393] There has been some cross-pollination with purely proprietary Unix derivatives,[394] such as AIX,[395] QNX,[396] Domain/OS,[397] HP-UX,[398] IRIX (see here),[399][400] Xenix,[401] SCO Unix,[402] Unixware,[403] Tru64 UNIX,[404][405] LynxOS (which features inbuilt Linux compatibility[406]), Ultrix,[407] OpenVMS,[408][409] z/OS UNIX System Services,[410] and even A/UX.[411] The games Doom and Quake were developed by id Software on NeXTStep,[412] a forerunner of modern macOS,[413] before being ported to DOS and back to numerous other Unix variants.[414] This involved reaching out to numerous Unix vendors to supply machines to use in the build and testing process.[415]

See also

[edit]- Directories and lists

- Linux gaming software

- Other articles

References

[edit]- ^ Ritchie, Dennis (June 2001). "Ken, Unix and Games". ICGA Journal. 24 (2): 67–70. doi:10.3233/ICG-2001-24202. Archived from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ Jowitt, Tom (26 May 2017). "Tales In Tech History: Unix". Silicon UK. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

The developers wanted to play the game on a PDP-7, a minicomputer built by Digital Equipment Corp found in the corner of their building. But the game couldn't be run run on more modern (and hence costly) equipment, as computing resource was a precious commodity back then. By the summer of 1969 they had developed the new Unix OS that could run the computer game and in 1971 the first ever edition of Unix was released. A second edition of Unix arrived in December 1972 and was rewritten in the higher-level language C.

- ^ Crick, Joseph (12 December 2017). "Lessons from the Development of Unix". Medium. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- ^ Toomey, Warren (December 2011). "The Strange Birth and Long Life of Unix" (PDF). IEEE Spectrum.

Apart from the text-processing and general system applications, the first edition of Unix included games such as blackjack, chess, and tic-tac-toe.

- ^ Bronnikov, Sergey. "Unix ASCII games". GitHub. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- ^ Radke, Harald (5 November 1999). "Tux's secret obsession – Gaming under Linux". LinuxFocus. Retrieved 26 May 2025.

- ^ Allen Holm, Joshua (21 June 2017). "Revisit Colossal Cave with Open Adventure". Opensource.com. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ Hasan, Mehedi (24 November 2022). "Top 20 Best ASCII Games on Linux System". Ubuntu Pit. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- ^ Gagné, Marcel (1 September 2000). "The Ghost of Fun Times Past". Linux Journal. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- ^ Woodman, Lawrence (11 August 2009). "My Top 10 Classic Text Mode BSD Games". TechTinkering. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- ^ Stallman, Richard. "Linux and the GNU System". GNU Project. Archived from the original on 19 March 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

Some of our system components, the programming tools, became popular on their own among programmers, but we wrote many components that are not tools. We even developed a chess game, GNU Chess, because a complete system needs games too.

- ^ Wen, Howard (21 November 2001). "Building Freeciv: An Open Source Strategy Game". LinuxDevCenter.com. Archived from the original on 29 December 2008. Retrieved 14 April 2009.

- ^ Armstrong, Ryan (18 November 2020). "Old X Games". Zerk Zone. Retrieved 14 February 2023.

- ^ Wilson, Hamish (10 January 2022). "Building a Retro Linux Gaming Computer – Part 8: Shovelware with a Penguin". GamingOnLinux. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ Link, Jay (30 September 1999). "Easy graphics: A beginner's guide to SVGAlib". Developer.com. Retrieved 29 September 2023.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Pitzel, Brad (12 February 1994). "Sasteroids v1.0 release (vga arcade game)". Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- ^ Ayers, Larry (1 July 1998). "Sabre: An Svgalib Flight Sim". Linux Gazette. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- ^ Beck, Andreas (1 November 1996). "Linux-GGI Project". Linux Journal. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ^ Wilson, Hamish (12 March 2024). "Building a Retro Linux Gaming Computer Part 40: The Cyborg Project". GamingOnLinux. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ "Software Announcements". Linux Weekly News. 6 January 2000. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ Fox, Alexander (5 January 2018). "The Best Open Source Clones of Great Old Games". Make Tech Easier. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- ^ Maskara, Swati (3 March 2021). "33 Best Open Source Games That Are Forever Free To Play". TechNorms. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- ^ Johnson, Michael K. (1 December 1994). "DOOM". Linux Journal. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ Zimbinski, Bob (1 January 1999). "Getting Started with Quake". Linux Journal.

- ^ Hellums, Duane (1 March 1999). "Red Hat LINUX Secrets, Second Edition". Linux Journal. Retrieved 2 July 2023.

It would be nice to see some extra CD goodies included, such as Doom and Quake which are freely available elsewhere.

- ^ Tackett, Jack (1997). Special Edition. Using Linux. United States: Que Corporation. p. 287. ISBN 9780470485460.

The X Windows version supplied on the accompanying Slackware CD-ROM in the /contrib directory is a complete hareware version. (The Red Hat distribution automatically installs the game during installation.) Although this version runs on 386 computers, it was built to run on high-end 486 systems. If you run DOOM on a 386 with a small amount of physical RAM, be prepared to be disappointed; the game will be too slow to be enjoyable. You need lots of horse-power to play DOOM under Linux.

- ^ Barkakati, Naba (1996). Linux Secrets. United States: IDG Books Worldwide. p. 96. ISBN 9781568847986.

This disk set contains a collection of well-known UNIX games (X is not required), such as Hangman, Dungeon, and Snake. The set also includes id Software's DOOM. (This game comes in two versions, one runs under X, and the other runs without X.) You may want to install this disk set just so you can try out DOOM.

- ^ Parker, Tim (1996). Linux Unleashed. United States: Macmillan Computer Publishing. p. 981. ISBN 0672313723.

DOOM - This exciting, though controversially gory, game is now ported to Linux as well. Complete with sound support and exquisite graphics, this Linux port does its DOS counterpart justice.

- ^ "So Long, Crack.com". loonygames. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ "Partnership with Crack dot Com Brings Games to Linux" (Press release). Red Hat. 7 October 1997. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ^ Anonymous (2000). Maximum Linux Security: A Hacker's Guide to Protecting Your Linux Server and Workstation, Volume 1. United States: Sams Publishing. p. 121. ISBN 9780672316708.

A classic, and very easy-to-follow SUID attack is the on the file /usr/lib/games/abuse/ abuse.console—part of a game that was distributed with Open Linux 1.1 and Red Hat 2.1. Yes, you read that right: Even a game can be a security risk to the system.

- ^ Jebens, Harley (26 April 2000). "Okay, Dave Taylor: Why Linux?". GameSpot. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- ^ Sawicki, Antoni (30 December 2022). "SimCity for Unix Liberated". Virtually Fun. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ^ "History and Future of OLPC SimCity / Micropolis". Archived from the original on 13 January 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ^ "[ANNC] The Linux Game Tome on the Web". groups.google.com. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ^ "'Dave Taylor Interview – game developer'". blankmaninc.com. 27 October 2012. Archived from the original on 23 July 2014. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- ^ Mrochuk, Jeff (15 November 2000). "How To Install Quake 1". Linux.com. Archived from the original on 1 April 2022. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Wilson, Hamish (27 February 2023). "Building a Retro Linux Gaming Computer – Part 27: Lost Souls". GamingOnLinux. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ Raghavan, Barath; Katz, Jeremy; Moffitt, Jack (19 February 1999). "An interview with Dave "Zoid" Kirsch of linux quake fame". Linux Power. Archived from the original on 10 September 1999. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ Reyes, Dustin (22 August 2004). "Interview with id Software's Timothee Besset". LinuxGames. Archived from the original on 24 September 2004. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ Chalk, Andy (6 February 2013). "John Carmack Argues Against Native Linux Games". The Escapist. Archived from the original on 21 January 2020. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- ^ Hitchens, Joe (19 September 2001). "Internet Based Software Development". Sleepless Software Inc. Archived from the original on 31 December 2001.

- ^ Dicks, Steve (December 1998). "REVIEW – The UNIX Book of Games". ACCU. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- ^ Gasperson, Tina (16 December 2004). "Site review: Linux Game Tome". Linux.com. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- ^ Larabel, Michael (18 November 2010). "LGP Has Been Down For A Month And A Half". Phoronix. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- ^ Stieben, Danny (6 February 2013). "Top 4 Websites To Discover Free Linux Games". Make Use Of. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ Wagh, Amol (14 September 2011). "Best Web Places to Find Amazing Free Linux Games". Digital Conqueror. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ Barr, Joe (1 July 1999). "You can tell a lot about an OS from its games". CNN. Archived from the original on 14 May 2001. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ Dawe, Liam (14 August 2023). "Rest in peace Dustin 'Crusader' Reyes, a pioneer of Linux gaming news". GamingOnLinux. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ "Ultima Online for Linux". Archived from the original on 29 February 2004.

- ^ Kuhnash, Jeremy (9 February 2000). "Hopkins FBI". Linux.com. Archived from the original on 28 October 2007.

- ^ "Interview: Scott Draeker and Sam Lantinga, Loki Entertainment". Linux Journal. 1 August 1999.

- ^ Lynch, Jim (7 September 2016). "Remembering Loki's Linux games from the '90s". InfoWorld. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ^ "Interview with Ryan Gordon: Postal2, Unreal & Mac Gaming – Macologist". Archived from the original on 9 March 2005.

- ^ Lantinga, Sam (1 September 1999). "SDL: Making Linux fun". IBM. Archived from the original on 11 May 2003. Retrieved 15 December 2023.

- ^ Kreimeier, Bernd (1 January 2001). "The Story of OpenAL". Linux Journal.

- ^ Hills, James. "Loki and the Linux World Expo – GameSpy chats with Linux legend Scott Draeker about the future of Linux gaming". GameSpy. Archived from the original on 15 March 2006.

- ^ Foster-Johnson, Eric. "Does Ragnarok for Loki Spell Doom for Linux Games?". Archived from the original on 29 August 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ a b c Mielewczik, Michael. "Spielspass pur. Kommerzielle Linux-Spiele". PC Magazin LINUX. 2/2007: 80–83.

- ^ Hills, James (1 March 2001). "Is Linux Gaming here to stay?". GameSpy. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ "Macmillan Says 'Let the Linux Games Begin!'; Market Leader in Linux Software & Books Offers 'Quake' & 'Civilization'". Business Wire. 17 June 1999. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- ^ Shah, Rawn (9 March 2000). "Quake III Arena on Linux". CNN. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ CmdrTaco (5 November 1998). "Red Hat not Interested in Publishing Id Games". Slashdot. Retrieved 12 September 2023.

- ^ Wilson, Hamish (16 January 2023). "Building a Retro Linux Gaming Computer – Part 21: Fluffy Bunnies". GamingOnLinux. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ Gestalt (21 November 2000). "Indrema to bring Linux to the masses?". Eurogamer. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ Shankland, Stephen (2 January 2002). "Game start-up faces major rivals with Linux console". CNET. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ Manjoo, Farhad (13 March 2001). "Game Arrives Only in Dreams". Wired. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ Becker, David (2 January 2002). "Plans for Linux game console fizzle". CNET. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ Smith, Tony (11 April 2001). "Linux games console fragged". The Register. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ Gross, Grant (18 April 2001). "TuxBox: Rising from Indrema's ashes". Linux.com. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ "The Linux Game Tome: Raptor – Call of the Shadows". Archived from the original on 21 February 2012. on The Linux Game Tome

- ^ "Linux Game Publishing Blog, LGP History pt 1: How LGP came to be". Archived from the original on 13 July 2011.

- ^ Dawe, Liam (30 June 2011). "Gameolith – The Linux Game Download Store". GamingOnLinux. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- ^ Bush, Josh (11 September 2018). "Cheese talks to himself (about Proton and the history of modern Linux gaming)". CheeseTalks. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- ^ Larabel, Michael (1 April 2014). "Linux Game Publishing Remains Dormant". Phoronix. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- ^ Wilson, Hamish (12 December 2023). "Building a Retro Linux Gaming Computer Part 36: Entertainment for X Windows". GamingOnLinux. Retrieved 15 December 2023.

While still being the most elaborate, 100 Great Linux Games was far from the only shovelware set of games released for Linux, with several UNIX CD-ROM vendors such as Walnut Creek CDROM and Omeron Systems also seeking a piece of the action for themselves.

- ^ Ajami, Amer (26 April 2000). "Take-Two Jumps on Linux". GameSpot. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ "Linux Games". Walnut Creek CDROM. Archived from the original on 28 October 2000. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^ "Walnut Creek CDROM Catalog". Walnut Creek CDROM. 17 December 2000. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

Linux Games (Linux) – Large collection of games, graphics, sound, and video applications, plus related development tools.

- ^ "PC CD-ROM – Shareware & utlity". Zeta. Italy. May 1997. p. 92. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ "PHT Products". Pacific Hitech. 1998. Archived from the original on 6 December 1998. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

Formerly known as 'Linux Games++', this is a collection of the best entertainment and multimedia programs for the Linux operating system. It also contains multimedia development tools to assist you in creating your own games and multimedia applications for Linux. This is the latest issue, volume 4, and features a new and improved user interface. The CD contains packages for i386, DEC Alpha, and PPC platforms. This product is only available through Walnut Creek CD-ROM.

- ^ "Linux Cubed Series 8 LINUX Games". Internet Archive Community Software. 11 December 1997. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ Thomas, Benjamin D. (2 April 2000). "Best Linux". Linux.com. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^ Knight, Will (5 February 2000). "CeBIT 2000: "Consumer" Linux from Finland". ZDNet. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^ "Linux is Best". SOT Finnish Software Engineering Ltd. Archived from the original on 16 August 2000. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^ Wilson, Hamish (8 August 2023). "Building a Retro Linux Gaming Computer Part 31: The Fear of Loss". GamingOnLinux. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

I did discover that Phobia III was later packaged as part of the Russian made LinuxCenter Games Collection Vol.2 compilation, a selection of Linux gaming files that was sold on either four CD-ROMs or a single DVD, but this too appeared to have been scrubbed from the internet.

- ^ Wilson, Hamish (12 December 2023). "Building a Retro Linux Gaming Computer Part 36: Entertainment for X Windows". GamingOnLinux. Retrieved 15 December 2023.

- ^ "Linux Products". Hemming Ag. Archived from the original on 16 January 2001. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ "SPIELE-TEST: Linux – Spiele & Games". PC Player. Germany. May 2000. p. 122. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ "Linux Spiele". GameFAQs. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ "play it! Linux: Die Spielesammlung …the funny side of Linux!". SocksCap64. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ "Loki Software Games Demos". Halo Linux Services. 3 June 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2023.

- ^ "Red Hat brings out Linux 7.1". ITWeb. 19 April 2001. Retrieved 30 June 2023.

- ^ Menalo, Nikolina (18 May 2000). "Corel puts out the Word on Office 2000". IT World Canada News. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

- ^ Knight, Will (9 December 1999). "Corel Linux Deluxe won't cross the pond". ZDNet. Retrieved 30 June 2023.

- ^ Gilbert, Jim (1 December 2000). "PowerPlant Review". Linux Journal. Retrieved 30 June 2023.

- ^ Schürmann, Tim (1 June 2001). "Komplettlösung Hopkins FBI". Linux Community.de. Retrieved 26 May 2025.

- ^ Wilson, Hamish (16 January 2023). "Building a Retro Linux Gaming Computer – Part 21: Fluffy Bunnies". GamingOnLinux. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ Wilson, Hamish (4 June 2023). "Building a Retro Linux Gaming Computer Part 29: The Odyssey". GamingOnLinux. Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- ^ Robertson, F. Grant (12 December 2001). "Review: Mandrake 8.1 Gaming Edition opens Linux to more games, more users". Linux.com. Retrieved 30 June 2023.

- ^ Gross, Grant (22 October 2001). "TransGaming, Mandrake team up to bring PC games directly to Linux". NewsForge. Archived from the original on 25 December 2001. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

- ^ Vaughan-Nichols, Steven J. (12 June 2008). "Finally, it's time for Wine". Linux.com. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

According to White in a 2006 NewsForge interview, this forking caused Wine's development to slow down for years. "Historically, the main interest for volunteer Wine developers was games; that was the primary focus for most of Wine's early years (~1993–2000). When Transgaming started in 2001, they promised that they would release their DirectX improvements back to Wine. That cast a chill over games in Wine — why work on DirectX if all these improvements would 'soon' be coming back? Of course, no meaningful improvements have ever come back, which had the effect of creating a huge hole in what had been Wine's very best facility." By 2007, White says, "The Wine community had recovered from the hole created by Transgaming."

- ^ Moss, Richard (16 January 2012). "Maniac Tentacle Mindbenders: How ScummVM's unpaid coders kept adventure gaming alive". Ars Technica. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ^ Dawe, Liam (15 July 2019). "DOSBox-X and DOSBox Staging both had new releases lately". GamingOnLinux. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ Diener, Derrik (5 February 2018). "How To Play Arcade Games Using MAME On Linux". Addictivetips. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- ^ Dawe, Liam (15 July 2019). "RetroArch, the front-end app for emulators and more is heading to Steam". GamingOnLinux. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ Dawe, Liam (30 April 2020). "If you have the retro gaming itch RetroPie 4.6 is out with support for the Raspberry Pi 4". GamingOnLinux. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ Long, Moe (23 September 2016). "How to Play Retro Windows Games on Linux". MakeUseOf. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ^ Warrington, Don (11 May 2020). "Is the Best Place to Run Old Windows Software... on Linux or a Mac?". Vulcan Hammer. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ^ Aznar, Guylhem (2 July 2002). "Applications for the Sharp Zaurus". Linux Journal. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

An excellent way to start using the Zaurus is by playing games. The best way to play games on the Zaurus is to install an emulator.

- ^ Kendrick, Bill. "Zaurus Software". New Breed Software. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ ""Agenda's agenda – a Linux-based "Open PDA""". Archived from the original on 13 May 2008., LinuxDevices.com, retrieved 17 July 2008

- ^ "Games". Agenda Wiki. Archived from the original on 17 October 2006. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ Kepley, Travis (13 May 2010). "A brief history of commercial gaming on Linux (and how it's all about to change)". Opensource.com. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ Olson, Dana (18 April 2003). "Gaming and Linux in 2003". LinuxHardware.org. Archived from the original on 2 June 2003. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- ^ Larabel, Michael (14 December 2010). "Alternative Games Is All About Linux Gaming". Phoronix.

- ^ Heggelund Hansen, Robin (10 March 2009). "Porting games to Linux". hardware.no. Archived from the original on 22 March 2014. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ "A mixed welcome for Unreal Tournament 2003 on Linux – LinuxWorld". Archived from the original on 29 February 2012. Retrieved 7 December 2009.

- ^ Mac, Linux America's Army – Blue's News

- ^ Serious Sam 2nd Encounter Q&A & Linux News – Blue's News

- ^ LGP History pt 1: How LGP came to be Archived 13 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Linux Game Publishing Blog, 15 May 2009 (Article by Michael Simms)

- ^ Furness, James (15 November 2001). "On Wolf's Goldness". Blue's News. Archived from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^ "Tux Racer website". Sunspire Studios. Archived from the original on 4 September 2004.

- ^ Serious Sam 2nd Encounter Q&A & Linux News – Blue's News

- ^ Linux Game Publishing and Pyrogon Announcement Archived 4 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine LinuxGames, 10 September 2002

- ^ Majesty, Tribsoft, and LGP Archived 14 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine LinuxGames, 3 January 2002

- ^ id Software's Main Linux Game Developer Resigns Phoronix, 27 January 2012

- ^ Crider, Michael (24 December 2017). "The Best Modern, Open Source Ports of Classic Games". How-To Geek. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ "Quake, Meet GPL; GPL, Meet Quake". Linux Journal. 1 December 2007. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ^ Bolding, Jonathan (4 September 2022). "Y'all know about these huge lists of free, open-source game clones, right?". PC Gamer. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- ^ Kumar, Nitesh (2021). "Open Source Ports of Commercial Game Engines". LinuxHint. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ Interview with Ryan Gordon: Postal², Unreal & Mac Gaming Macologist, 10 November. 2004

- ^ id Software's Main Linux Game Developer Resigns Phoronix, 27 January 2012

- ^ Hyperspace Delivery Boy Port Archived 4 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine LinuxGames, 6 September 2002

- ^ Interview with Ryan Gordon: Postal2, Unreal & Mac Gaming Macologist, 10 November. 2004

- ^ Rice, Christopher (28 December 2009). "Linux Gaming: Are We There Yet?". AnandTech. Archived from the original on 30 March 2010. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ Hoogland, Jeff (April 2010). "Codeweavers vs. Cedega, Commercial Wine Product Comparison". Linux Gazette. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ Vrabie, Stefan (31 July 2006). "Cedega and Linux: Let the Windows games begin". Linux.com. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ a b Lees, Jennie (4 December 2005). "Linux gaming made easy". Engadget. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ Dave, Salvator (28 July 2004). "Linux Takes on Windows Gaming". Extreme Tech. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ Millard, Elizabeth (24 June 2004). "TransGaming Updates WineX for Linux Gaming". Ecommerce Times. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ M, Angelo (2 February 2021). "PlayOnLinux vs Wine: The Differences". ImagineLinux. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ Husted, Steve (13 September 2004). "Opinion: Regarding the Linux Gaming". OSNews. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ a b "Wolfire Stats" (TXT).

- ^ a b "The State of Linux Gaming 2011". OSNews.com. 14 November 2011. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

In short: indie games are thriving on Linux. The Humble Bundles have not only helped publicize the games, but have also helped prove that there is an untapped market for games on Linux, and that Linux users have no problem paying to support the developers who support them.

- ^ Rosen, Jeffrey (28 December 2008). "Why you should support Mac OS X and Linux". Wolfire Games. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

- ^ Kuchera, Ben (1 March 2011). "Humble Bundle creator on Ars' influence and why Linux is important". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ Orland, Kyle (28 February 2011). "GDC 2011: Humble Indie Bundle Creators Talk Inspiration, Execution". Game Developer. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

Linux users tended to be the most generous of these, leading Graham to suggest indie developers go after underserved markets. "If you support Mac and Linux as an independent developer you have a good chance of doubling your revenue," Graham said.

- ^ Sneddon, Joey (21 December 2011). "Linux Users Continue To Pay Most for the @Humble Indie Bundle". OMG! Ubuntu!. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ^ Priestman, Chris (4 June 2012). "LINUX USERS PETITION AGAINST 'HUMBLE BUNDLE V' DUE TO NON-NATIVE VERSION OF 'LIMBO'". Indie Game Magazine. Archived from the original on 8 June 2012. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- ^ Dawe, Liam (19 June 2014). "LIMBO Dark Platformer Fully Native Linux Version Released, No More Wine". GamingOnLinux. Archived from the original on 15 July 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ^ Orland, Kyle (29 November 2012). "Humble THQ Bundle threatens to ruin the brand's reputation (Updated)". Ars Technica. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ^ Machkovich, Sam (14 January 2022). "Humble subscription service is dumping Mac, Linux access in 18 days". Ars Technica. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ "Voltely product page". Entourev LLC. Archived from the original on 22 December 2014. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ "Native Linux Games". Linuxexperten.com. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ Larabel, Michael (29 January 2009). "LGP Is Now Porting Shadowgrounds: Survivor". Phoronix. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- ^ "An Interview with Liam Dawe, Owner of GamingOnLinux". Linux Gaming Central. 20 April 2022. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- ^ "Desura games now also for Linux". The H Online. 18 November 2011. Retrieved 3 July 2024.

- ^ "cheese talks to himself – Desura Beta". twolofbees.com. 11 October 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- ^ a b c "The state of Linux gaming in the SteamOS era". Ars Technica. 26 February 2015. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- ^ Zinoune, M. (27 November 2011). "Will it be Desura's Linux client Vs USC?". Unixmen. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- ^ Dawe, Liam (21 August 2011). "Interview with Jonathan Prior of Gameolith.com". GamingOnLinux. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- ^ Larabel, Michael (11 July 2011). "A New Linux Game Store Is Launching Next Week". Phoronix. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- ^ Albanesius, Chloe (17 July 2012). "Valve Moves Forward With Steam for Linux | News & Opinion". PCMag.com. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ "Steam'd Penguins". Valve. 16 July 2012. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- ^ Lein, Tracey (16 July 2012). "'Left 4 Dead 2' to be first Valve game on Linux". The Verve. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- ^ Hillier, Brenna (24 July 2012). "Serious Sam 3: BFE headed to Steam Ubuntu". VG247. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ^ Larbel, Michael (25 May 2010). "Valve's Linux Play May Lead More Games To Follow Suit". Phoronix. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- ^ Larbel, Michael (18 November 2010). "Egosoft Wants To Bring Games To Steam On Linux". Phoronix. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ^ "Editorial: Linux Gaming Will Be Fine Even Without Steam Machines Succeeding". GamingOnLinux. 20 February 2015. Retrieved 27 February 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Unity 4.0 Launches". Marketwire. 14 November 2012. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ^ Makuch, Eddie (23 September 2013). "Valve reveals SteamOS". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 26 September 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ Crecente, Brian (4 June 2015). "The first official Steam Machines hit Oct. 16, on store shelves Nov. 10". Polygon. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ Dawe, Liam (18 March 2014). "GOG.com Are Going To Support Linux, Confirmed!". GamingOnLinux. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ Dawe, Liam (24 July 2014). "GOG Com Now Officially Support Linux Games". GamingOnLinux. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- ^ "GOG finally remove the false 'in progress' note about GOG Galaxy for Linux". GamingOnLinux. 1 July 2022. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- ^ "Lutris v0.5.12 out now fixing Origin, Epic Store, Ubisoft Connect, GOG". GamingOnLinux. 5 December 2022. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- ^ "GameHub is another open source game launcher, giving Lutris some competition". GamingOnLinux. 18 March 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ "Minigalaxy the simple GOG client for Linux has a big 1.0 release". GamingOnLinux. 30 November 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ "Heroic Games Launcher is a new unofficial Epic Games Store for Linux". GamingOnLinux. 5 January 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ "Unreal Engine 4.1 Update Preview". 3 April 2014. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- ^ "CRYENGINE adds Linux Support as Crytek Prepare to Offer New Possibilities at GDC". 11 March 2014. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- ^ Dawe, Liam (29 December 2014). "The Itch Games Store Are Working On An Open Source Client". GamingOnLinux. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ Corcoran, Leaf (14 December 2015). "Say hello to the itch.io app: itch". Itch.io. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- ^ Orphanides, K.G. (8 August 2018). "Crossing Platforms: a Talk with the Developers Building Games for Linux". Linux Journal. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ Prakash, Abhishek (19 January 2023). "Fantastic Linux Games and Where to Find Them". It's FOSS. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- ^ Kerr, Chris (13 January 2016). "Indie marketplace Game Jolt releases open source desktop client". Game Developer. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- ^ Lee, Joel (30 August 2015). "Where to Download the Best Linux Games Without Any Hassle". MakeUseOf. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- ^ Sohail, Mohd (23 December 2016). "Popular Gaming Platforms For Linux". LinuxAndUbuntu. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- ^ "OpenXRay, an enhanced game engine for S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Call of Pripyat shows off Linux progress". GamingOnLinux. 30 November 2018. Retrieved 1 July 2025.

- ^ Cartwright, John. "Stalker game running on Linux with Open Xray. – Securitron Linux blog". Retrieved 1 July 2025.

- ^ "Новая версия открытого движка OpenXRay (S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Call of Pripyat) версии 730". www.linux.org.ru (in Russian). 10 July 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2025.

- ^ Isaac (2 December 2018). "OpenXRay: an improved graphics engine for STALKER: Call of Pripyat". Desde Linux. Retrieved 1 July 2025.

- ^ Dawe, Liam (16 July 2015). "End Of An Era, LinuxGames Website Looks To Be Shutting Down". GamingOnLinux. Retrieved 22 July 2025.

- ^ Wong, Alistair (25 August 2018). "Steam Play Proton To Improve Game Support For Linux Users". Siliconera. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ "Steam for Linux :: Introducing a new version of Steam Play". 21 August 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ^ "Changelog · ValveSoftware/Proton Wiki". 31 July 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- ^ "Changelog · ValveSoftware/Proton Wiki". 8 November 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- ^ Dawe, Liam (7 September 2020). "The itch.io app can now use a system installed Wine on Linux for Windows-only games". GamingOnLinux. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- ^ Kenlon, Seth (25 October 2018). "Lutris: Linux game management made easy". Opensource.com. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ Saive, Ravi (18 July 2022). "PlayOnLinux – Run Windows Software and Games in Linux". TechMint. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ Slater, Jack (19 July 2021). "Native Linux Games vs Windows API Compatibility Layers on the Steam Deck". Nuclear Monster. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ LateToTheParty (22 July 2021). "The Linux Gaming Conundrum: Proton vs. Native Linux Support". Publish0x. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ Dawe, Liam (6 September 2022). "Prodeus cancels the Native Linux version, focusing on Proton compatibility (updated)". GamingOnLinux.

- ^ Dawe, Liam (14 August 2023). "Heart of the Machine from Arcen Games dropping Native Linux for Proton". GamingOnLinux.

- ^ Dawe, Liam (13 November 2021). "Valve answers the question: should developers do native Linux support or Proton?". Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ Dawe, Liam (25 February 2022). "The Steam Deck has released, here's my initial review". GamingOnLinux. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ Larabel, Michael (25 February 2022). "For Linux Enthusiasts Especially, The Steam Deck Is An Incredible & Fun Device". Phoronix. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ Marks, Tom (30 July 2021). "Valve Explains How The Failure of Steam Machines Helped Build The Steam Deck". IGN. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ McFerran, Damien (11 September 2013). "Neo Geo X Gold & Mega Pack Volume 1". Time Extension. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

It uses a Linux-based emulator running on a 1GHz Jz4770 system-on-chip

- ^ Humphries, Matthew (7 November 2016). "NES Classic Is a Quad-Core Linux Computer". PCMag. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ Ackerman, Dan (9 October 2017). "Hackers crack SNES Classic to add more games and features". CNET. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

Fortunately, the SNES Classic, like its predecessor, is basically a Nintendo emulator built on a Linux foundation, so it's not impossible to hack.

- ^ Machkovech, Sam (12 September 2019). "Sega Genesis Mini review: $80 delivers a ton of blast-processing fun". Ars Technica. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

Let this look at the taken-apart Sega Genesis Mini remind you that, like other recent retro consoles, the SGM relies on a Linux-driven SoC.

- ^ Takahashi, Dean (21 June 2019). "Intellivision Entertainment prepares for its rebirth on 10–10–20". VentureBeat. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

But our OS is a hybrid, a Linux/Android hybrid that we've created in house. It's very solid, but it's very flexible, with Linux being the flexible part and Android being the solid part.

- ^ Shilov, Anton (19 December 2023). "World's first RISC-V handheld gaming system announced — retro gaming platform uses Linux". Tom's Hardware. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ Portnoy, Sean (31 May 2018). "Atari VCS gaming console Linux mini-PC finally available to pre-order". ZDNET. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ Grant, Christopher (3 September 2021). "The Polymega is an all-in-one retro console worth your attention". Polygon. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

The Polymega is a software emulation-based console with a custom, Intel-backed motherboard running on Linux with a custom user interface.

- ^ Welch, Thomas (28 November 2012). "Game Gadget Review". Calm Down Tom. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ Linneman, John (25 April 2020). "Evercade review: the cartridge-based retro handheld that works". Eurogamer. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

Inside, the Evercade features a 1.2GHz Cortex A7 SoC running a customized Linux setup.

- ^ Petite, Steven (16 December 2022). "Evercade EXP Review". GameSpot. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

The custom Linux operating system that the EXP runs borrows from the VS home console.

- ^ Dawe, Liam (2 February 2023). "Zoom Platform, a store aimed at 'Generation X' adds more Linux support". GamingOnLinux. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ "PPC games made by Loki software – related posts LinuxGames". Archived from the original on 19 October 2013.

- ^ "Loki Holiday Info and Deals LinuxGames". Archived from the original on 20 October 2013.

- ^ "Candy Cruncher Linux Sparc". 9 September 2005. Archived from the original on 9 September 2005.

- ^ "Linux Game Publishing: Interview with Michael Simms". Linux Gazette. 6 March 2005. Archived from the original on 12 July 2005.

- ^ "Dominions II: The Ascension Wars 2.12". 8 June 2004. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013.

- ^ "Linux Version of SiN Almost Finished". amiga-news.de. 28 August 2008. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ "Gorky 17 dla Linuxa PPC". eXec.pl. 8 June 2006. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ "Linux: PowerPC port of Robin Hood". amiga-news.de. 30 July 2006. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ "Steam Hardware & Software survey". July 2021.

- ^ "Where's the Unity stats page gone?". Unity Forum. 24 January 2018. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ Platforms Top on 2016-03 Archived 27 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine Windows Players: 97.3%, OS X Players: 2.3%, Linux Players: 0.4%

- ^ "Humble Budle data".

- ^ "Ubuntu Linux Gaming Performance Mostly On Par With Windows 8.1". Phoronix. 27 October 2013. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ "NVIDIA GeForce: Windows 10 vs. Ubuntu 15.04 Linux OpenGL Benchmarks Review – Phoronix".

- ^ "SteamOS gaming performs significantly worse than Windows, Ars analysis shows". 13 November 2015.

- ^ "Budget Fair Queueing I/O Scheduler". Archived from the original on 11 March 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ "Phoronix: Liquorix-benchmarks".

- ^ "Liquorix homepage".

- ^ Dawe, Liam (21 September 2021). "GameMaker Studio 2 update released to bring forth the Ubuntu Linux editor Beta". GamingOnLinux. Retrieved 9 September 2023.

- ^ Dawe, Liam (27 September 2016). "Fusion 3, the next generation game engine and editor from Clickteam will support Linux". GamingOnLinux. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ Dawe, Liam (13 September 2023). "Here's some alternatives to the Unity game engine". GamingOnLinux. Retrieved 16 September 2023.

- ^ Dawe, Liam (20 July 2022). "Unreal Engine 5 editor quietly gets a proper Linux version". GamingOnLinux. Retrieved 9 September 2023.

- ^ Best, Martin (30 May 2019). "Announcing the Unity Editor for Linux". Unity Blog. Retrieved 9 September 2023.