Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Scientific modelling

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Research |

|---|

|

| Philosophy portal |

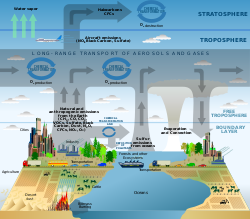

Scientific modelling is an activity that produces models representing empirical objects, phenomena, and physical processes, to make a particular part or feature of the world easier to understand, define, quantify, visualize, or simulate. It requires selecting and identifying relevant aspects of a situation in the real world and then developing a model to replicate a system with those features. Different types of models may be used for different purposes, such as conceptual models to better understand, operational models to operationalize, mathematical models to quantify, computational models to simulate, and graphical models to visualize the subject.

Modelling is an essential and inseparable part of many scientific disciplines, each of which has its own ideas about specific types of modelling.[1][2] The following was said by John von Neumann.[3]

... the sciences do not try to explain, they hardly even try to interpret, they mainly make models. By a model is meant a mathematical construct which, with the addition of certain verbal interpretations, describes observed phenomena. The justification of such a mathematical construct is solely and precisely that it is expected to work—that is, correctly to describe phenomena from a reasonably wide area.

There is also an increasing attention to scientific modelling[4] in fields such as science education,[5] philosophy of science, systems theory, and knowledge visualization. There is a growing collection of methods, techniques and meta-theory about all kinds of specialized scientific modelling.

Overview

[edit]

A scientific model seeks to represent empirical objects, phenomena, and physical processes in a logical and objective way. All models are in simulacra, that is, simplified reflections of reality that, despite being approximations, can be extremely useful.[6] Building and disputing models is fundamental to the scientific enterprise. Complete and true representation may be impossible, but scientific debate often concerns which is the better model for a given task, e.g., which is the more accurate climate model for seasonal forecasting.[7]

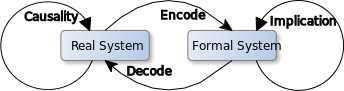

Attempts to formalize the principles of the empirical sciences use an interpretation to model reality, in the same way logicians axiomatize the principles of logic. The aim of these attempts is to construct a formal system that will not produce theoretical consequences that are contrary to what is found in reality. Predictions or other statements drawn from such a formal system mirror or map the real world only insofar as these scientific models are true.[8][9]

For the scientist, a model is also a way in which the human thought processes can be amplified.[10] For instance, models that are rendered in software allow scientists to leverage computational power to simulate, visualize, manipulate and gain intuition about the entity, phenomenon, or process being represented. Such computer models are in silico. Other types of scientific models are in vivo (living models, such as laboratory rats) and in vitro (in glassware, such as tissue culture).[11]

Basics

[edit]Modelling as a substitute for direct measurement and experimentation

[edit]Models are typically used when it is either impossible or impractical to create experimental conditions in which scientists can directly measure outcomes. Direct measurement of outcomes under controlled conditions (see Scientific method) will always be more reliable than modeled estimates of outcomes.

Within modeling and simulation, a model is a task-driven, purposeful simplification and abstraction of a perception of reality, shaped by physical, legal, and cognitive constraints.[12] It is task-driven because a model is captured with a certain question or task in mind. Simplifications leave all the known and observed entities and their relation out that are not important for the task. Abstraction aggregates information that is important but not needed in the same detail as the object of interest. Both activities, simplification, and abstraction, are done purposefully. However, they are done based on a perception of reality. This perception is already a model in itself, as it comes with a physical constraint. There are also constraints on what we are able to legally observe with our current tools and methods, and cognitive constraints that limit what we are able to explain with our current theories. This model comprises the concepts, their behavior, and their relations informal form and is often referred to as a conceptual model. In order to execute the model, it needs to be implemented as a computer simulation. This requires more choices, such as numerical approximations or the use of heuristics.[13] Despite all these epistemological and computational constraints, simulation has been recognized as the third pillar of scientific methods: theory building, simulation, and experimentation.[14]

Simulation

[edit]

A simulation is a way to implement the model, often employed when the model is too complex for the analytical solution. A steady-state simulation provides information about the system at a specific instant in time (usually at equilibrium, if such a state exists). A dynamic simulation provides information over time. A simulation shows how a particular object or phenomenon will behave. Such a simulation can be useful for testing, analysis, or training in those cases where real-world systems or concepts can be represented by models.[15]

Structure

[edit]Structure is a fundamental and sometimes intangible notion covering the recognition, observation, nature, and stability of patterns and relationships of entities. From a child's verbal description of a snowflake, to the detailed scientific analysis of the properties of magnetic fields, the concept of structure is an essential foundation of nearly every mode of inquiry and discovery in science, philosophy, and art.[16]

Systems

[edit]A system is a set of interacting or interdependent entities, real or abstract, forming an integrated whole. In general, a system is a construct or collection of different elements that together can produce results not obtainable by the elements alone.[17] The concept of an 'integrated whole' can also be stated in terms of a system embodying a set of relationships which are differentiated from relationships of the set to other elements, and form relationships between an element of the set and elements not a part of the relational regime. There are two types of system models: 1) discrete in which the variables change instantaneously at separate points in time and, 2) continuous where the state variables change continuously with respect to time.[18]

Generating a model

[edit]Modelling is the process of generating a model as a conceptual representation of some phenomenon. Typically a model will deal with only some aspects of the phenomenon in question, and two models of the same phenomenon may be essentially different—that is to say, that the differences between them comprise more than just a simple renaming of components.

Such differences may be due to differing requirements of the model's end users, or to conceptual or aesthetic differences among the modelers and to contingent decisions made during the modelling process. Considerations that may influence the structure of a model might be the modeler's preference for a reduced ontology, preferences regarding statistical models versus deterministic models, discrete versus continuous time, etc. In any case, users of a model need to understand the assumptions made that are pertinent to its validity for a given use.

Building a model requires abstraction. Assumptions are used in modelling in order to specify the domain of application of the model. For example, the special theory of relativity assumes an inertial frame of reference. This assumption was contextualized and further explained by the general theory of relativity. A model makes accurate predictions when its assumptions are valid, and might well not make accurate predictions when its assumptions do not hold. Such assumptions are often the point with which older theories are succeeded by new ones (the general theory of relativity works in non-inertial reference frames as well).

Evaluating a model

[edit]A model is evaluated first and foremost by its consistency to empirical data; any model inconsistent with reproducible observations must be modified or rejected. One way to modify the model is by restricting the domain over which it is credited with having high validity. A case in point is Newtonian physics, which is highly useful except for the very small, the very fast, and the very massive phenomena of the universe. However, a fit to empirical data alone is not sufficient for a model to be accepted as valid. Factors important in evaluating a model include:[citation needed]

- Ability to explain past observations

- Ability to predict future observations

- Cost of use, especially in combination with other models

- Refutability, enabling estimation of the degree of confidence in the model

- Simplicity, or even aesthetic appeal

People may attempt to quantify the evaluation of a model using a utility function.

Visualization

[edit]Visualization is any technique for creating images, diagrams, or animations to communicate a message. Visualization through visual imagery has been an effective way to communicate both abstract and concrete ideas since the dawn of man. Examples from history include cave paintings, Egyptian hieroglyphs, Greek geometry, and Leonardo da Vinci's revolutionary methods of technical drawing for engineering and scientific purposes.

Space mapping

[edit]Space mapping refers to a methodology that employs a "quasi-global" modelling formulation to link companion "coarse" (ideal or low-fidelity) with "fine" (practical or high-fidelity) models of different complexities. In engineering optimization, space mapping aligns (maps) a very fast coarse model with its related expensive-to-compute fine model so as to avoid direct expensive optimization of the fine model. The alignment process iteratively refines a "mapped" coarse model (surrogate model).

Types

[edit]Applications

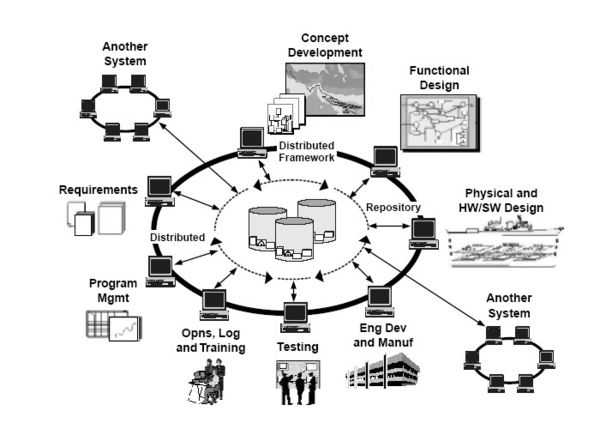

[edit]Modelling and simulation

[edit]One application of scientific modelling is the field of modelling and simulation, generally referred to as "M&S". M&S has a spectrum of applications which range from concept development and analysis, through experimentation, measurement, and verification, to disposal analysis. Projects and programs may use hundreds of different simulations, simulators and model analysis tools.

The figure shows how modelling and simulation is used as a central part of an integrated program in a defence capability development process.[15]

See also

[edit]- Abductive reasoning – Inference seeking the simplest and most likely explanation

- All models are wrong – Aphorism in statistics

- Data and information visualization – Visual representation of data

- Heuristic – Problem-solving method

- Inverse problem – Process of calculating the causal factors that produced a set of observations

- Scientific visualization – Interdisciplinary branch of science concerned with presenting scientific data visually

- Statistical model – Type of mathematical model

References

[edit]- ^ Cartwright, Nancy. 1983. How the Laws of Physics Lie. Oxford University Press

- ^ Hacking, Ian. 1983. Representing and Intervening. Introductory Topics in the Philosophy of Natural Science. Cambridge University Press

- ^ von Neumann, J. (1995), "Method in the physical sciences", in Bródy F., Vámos, T. (editors), The Neumann Compendium, World Scientific, p. 628; previously published in The Unity of Knowledge, edited by L. Leary (1955), pp. 157-164, and also in John von Neumann Collected Works, edited by A. Taub, Volume VI, pp. 491-498.

- ^ Frigg and Hartmann (2009) state: "Philosophers are acknowledging the importance of models with increasing attention and are probing the assorted roles that models play in scientific practice". Source: Frigg, Roman and Hartmann, Stephan, "Models in Science", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2009 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), (source)

- ^ Namdar, Bahadir; Shen, Ji (2015-02-18). "Modelling-Oriented Assessment in K-12 Science Education: A synthesis of research from 1980 to 2013 and new directions". International Journal of Science Education. 37 (7): 993–1023. Bibcode:2015IJSEd..37..993N. doi:10.1080/09500693.2015.1012185. ISSN 0950-0693. S2CID 143865553.

- ^ Box, George E.P. & Draper, N.R. (1987). [Empirical Model-Building and Response Surfaces.] Wiley. p. 424

- ^ Hagedorn, R. et al. (2005) http://www.ecmwf.int/staff/paco_doblas/abstr/tellus05_1.pdf Archived 2020-03-27 at the Wayback Machine Tellus 57A:219–33

- ^ Leo Apostel (1961). "Formal study of models". In: The Concept and the Role of the Model in Mathematics and Natural and Social. Edited by Hans Freudenthal. Springer. pp. 8–9 (Source)],

- ^ Ritchey, T. (2012) Outline for a Morphology of Modelling Methods: Contribution to a General Theory of Modelling

- ^ C. West Churchman, The Systems Approach, New York: Dell Publishing, 1968, p. 61

- ^ Griffiths, E. C. (2010) What is a model?

- ^ Tolk, A. (2015). Learning something right from models that are wrong – Epistemology of Simulation. In Yilmaz, L. (Ed.) Concepts and Methodologies in Modelling and Simulation. Springer–Verlag. pp. 87–106

- ^ Oberkampf, W. L., DeLand, S. M., Rutherford, B. M., Diegert, K. V., & Alvin, K. F. (2002). Error and uncertainty in modelling and simulation. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 75(3): 333–57.

- ^ Ihrig, M. (2012). A New Research Architecture For The Simulation Era. In European Council on Modelling and Simulation. pp. 715–20).

- ^ a b c Systems Engineering Fundamentals. Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Defense Acquisition University Press, 2003.

- ^ Pullan, Wendy (2000). Structure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-78258-9.

- ^ Fishwick PA. (1995). Simulation Model Design and Execution: Building Digital Worlds. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- ^ Sokolowski, J.A., Banks, C.M.(2009). Principles of Modelling and Simulation. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons.

Further reading

[edit]Nowadays there are some 40 magazines about scientific modelling which offer all kinds of international forums. Since the 1960s there is a strongly growing number of books and magazines about specific forms of scientific modelling. There is also a lot of discussion about scientific modelling in the philosophy-of-science literature. A selection:

- Rainer Hegselmann, Ulrich Müller and Klaus Troitzsch (eds.) (1996). Modelling and Simulation in the Social Sciences from the Philosophy of Science Point of View. Theory and Decision Library. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

- Paul Humphreys (2004). Extending Ourselves: Computational Science, Empiricism, and Scientific Method. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Johannes Lenhard, Günter Küppers and Terry Shinn (Eds.) (2006) "Simulation: Pragmatic Constructions of Reality", Springer Berlin.

- Tom Ritchey (2012). "Outline for a Morphology of Modelling Methods: Contribution to a General Theory of Modelling". In: Acta Morphologica Generalis, Vol 1. No 1. pp. 1–20.

- William Silvert (2001). "Modelling as a Discipline". In: Int. J. General Systems. Vol. 30(3), pp. 261.

- Sergio Sismondo and Snait Gissis (eds.) (1999). Modeling and Simulation. Special Issue of Science in Context 12.

- Eric Winsberg (2018) "Philosophy and Climate Science" Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Eric Winsberg (2010) "Science in the Age of Computer Simulation" Chicago: University of Chicago Press

- Eric Winsberg (2003). "Simulated Experiments: Methodology for a Virtual World". In: Philosophy of Science 70: 105–125.

- Tomáš Helikar, Jim A Rogers (2009). "ChemChains Archived 2021-03-03 at the Wayback Machine: a platform for simulation and analysis of biochemical networks aimed to laboratory scientists". BioMed Central.

External links

[edit]- Models. Entry in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Models in Science. Entry in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- The World as a Process: Simulations in the Natural and Social Sciences, in: R. Hegselmann et al. (eds.), Modelling and Simulation in the Social Sciences from the Philosophy of Science Point of View, Theory and Decision Library. Dordrecht: Kluwer 1996, 77-100.

- Research in simulation and modelling of various physical systems

- Modelling Water Quality Information Center, U.S. Department of Agriculture

- Ecotoxicology & Models

- A Morphology of Modelling Methods. Acta Morphologica Generalis, Vol 1. No 1. pp. 1–20.