Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

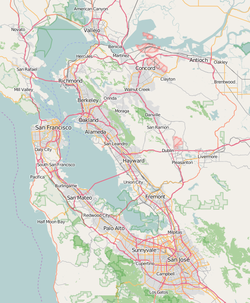

Milpitas, California

View on Wikipedia

Milpitas (Spanish for 'little milpas' or little cornfields) is a city in Santa Clara County, California, part of Silicon Valley and the broader San Francisco Bay Area. Located on the eastern shore of San Francisco Bay, it is bordered by San Jose to the South, Fremont to the North, and the Coyote Creek to the west, and Calaveras Reservoir to the east. As of the 2020 census, the city population was 80,273.[6] The city is located at the junction of Interstates 680 and 880 and is served by the Milpitas BART station.

Key Information

Historically inhabited by the Ohlone people, the area served as a crossroads between Mission San José de Guadalupe in present-day Fremont and Mission Santa Clara de Asis in present-day Santa Clara. The city’s modern development began in the mid-20th century, driven by postwar suburbanization and its incorporation in 1954. Milpitas experienced rapid growth during the 1970s–1990s, fueled by Silicon Valley’s tech industry, and became a hub for manufacturing and corporate offices, hosting companies like Cisco Systems, KLA Corporation, and Flex Ltd.. Its diverse population includes significant Asian and Hispanic communities, reflecting broader Bay Area demographic trends.

Milpitas' economy is closely tied to the tech sector, though it also features retail landmarks such as the Great Mall of the Bay Area, one of Northern California’s largest outlet malls. Environmental challenges include odor issues linked to the adjacent Newby Island landfill and water pollution from street water runoff and industrial wastes. The city's infrastructure includes multiple public parks, trails, and access to regional transit systems, including VTA light rail and buses.

History

[edit]Milpitas was first inhabited by Tamien people, a subgroup of the Ohlone people who had resided in the San Francisco Bay Area for thousands of years. The Ohlone Indians lived a traditional life based on everyday hunting and gathering. Some of the Ohlone lived in various villages within what is now Milpitas, including sites underneath what are now the Calvary Assembly of God Church and Higuera Adobe Park.[7] Archaeological evidence gathered from Ohlone graves at the Elmwood Correctional Facility in 1993 revealed a rich trade with other tribes from Sacramento to Monterey.

During the Spanish expeditions of the late 18th century, several missions were founded in the San Francisco Bay Area. During the mission period, Milpitas served as a crossroads between Mission San José de Guadalupe in present-day Fremont and Mission Santa Clara de Asis in present-day Santa Clara. The land of modern-day Milpitas was divided between the 6,353-acre (25.71 km2) Rancho Rincon de Los Esteros (Spanish for "corner of the wetlands") granted to Ignacio Alviso; the 4,457.8-acre (18.040 km2) Rancho Milpitas (Spanish for "little milpaa" (corn fields)) granted to José María Alviso; and the 4,394.35-acre (17.7833 km2) Rancho Los Tularcitos (Spanish for "little tule marshes") granted to José Higuera. Jose Maria Alviso was the son of Francisco Xavier Alviso and Maria Bojorquez, both of whom arrived in San Francisco as children with the de Anza Expedition. José María Alviso is considered to be the founder of Milpitas. Due to Jose Maria Alviso's descendants' difficulty securing his claims to the Rancho Milpitas property, portions of his land were either swindled from the Alviso family or were sold to American settlers to pay for legal fees.[8]

Both landowners had built prominent adobe homes on their properties. Today, both adobes still exist and are the oldest structures in Milpitas. The seriously eroded walls of the Jose Higuera Adobe, now in Higuera Adobe Park, are encapsulated in a brick shell built c. 1970 by Marian Weller, a descendant of pioneer Joseph Weller.[9]

The Alviso Adobe can be seen mostly in its original form, with one kitchen addition made by the Cuciz family after they purchased the adobe from the Gleason family in 1922. Prior to the city acquiring the Alviso Adobe in 1995, it was the oldest continuously occupied adobe house in California dating from the Mexican period and today is still gradually being restored and undergoing seismic upgrades by the City of Milpitas.

In the 1850s, large numbers of Americans of English, German, and Irish descent arrived to farm the fertile lands of Milpitas. The Burnett, Rose, Dempsey, Jacklin, Trimble, Ayer, Parks, Wool, Weller, Minnis, and Evans families are among the early settlers of Milpitas.[10] (Today many schools, streets, and parks have been named in honor of these families.) These early settlers farmed the land that was once the ranchos. Some set up businesses on what was then called Mission Road (now called Main Street) between Calaveras Road (now called Carlo Street) and the Alviso-Milpitas Road (now called Serra Way). By the late 20th century this area became known as the "Midtown" district. Yet another influx of immigration came in the 1870s and 1880s as Portuguese sharecroppers from the Azores came to farm the Milpitas hillsides. Many of the Azoreans had such locally well-known surnames as Coelho, Covo, Mattos, Nunes, Spangler, Serpa, and Silva.

There is a local legend that in 1857, when the U.S. Postal Service wanted to locate a Post Office in Frederick Creighton's store near the intersection of Mission Road and Alviso-Milpitas Road to serve the newly created Township, there was some support for naming it Penitencia, after the small Roman Catholic confessional building that had served local Indians and ranchers and had once stood several miles south of the village near Penitencia Creek which ran just west of the Mission Road. A local farmer and first Assistant Postmaster, Joseph Weller, felt the Spanish word Penitencia might be confused with the English word "penitentiary." Instead of choosing Penitencia, he suggested another popular name for the area, Milpitas, after the name of Alviso's property, Rancho Milpitas. Thus was born "Milpitas Township."[11]

For over a century, Milpitas served as a popular rest stop for travelers on the old Oakland−San Jose Highway. At the north side of the intersection of that road with the Milpitas-Alviso Road, for many years stood "French's Hotel" that had been originally built by Alex Anderson prior to 1859, when Alfred French bought it from Austin M. Thompson.[12] South of the site of French's Hotel, was a saloon dating from at least 1856 when Agustus Rathbone purchased the land and "improvements" from Richard Greenham. The first murder in Milpitas was committed in the early 1860s in "Rathbone's Saloon" (alas, the murderer escaped). Later the saloon was replaced by a hotel that is shown on the 1893 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map as "Goodwin's Hotel" (perhaps the same Henry K. Goodwin who, in 1890, loaned money to prominent local rancher Marshall Pomeroy). Presumably, this hotel burned down and "Smith's Corner," which still stands, was built in 1895, by John Smith, as a saloon that served beer and wine to thirsty travelers for a century before becoming a restaurant in 2001.[13] Around this central core, grocery and dry goods stores, blacksmithies, service stations, and, in the 1920s, one of America's earliest "fast food" chain restaurants, "The Fat Boy", opened nearby. Another of Milpitas's most popular restaurants was the "Kozy Kitchen", established in 1940 by the Carlo family in the former "Central Market" building. Kozy Kitchen was demolished soon after Jimmy Carlo sold the restaurant in 1999.[14] Even in the early 1950s, Milpitas served a farming community of 800 people who walked a mere one or two blocks to work.

On January 26, 1954, faced with getting swallowed up by a rapidly expanding San Jose, Milpitas residents incorporated as a city that included the recently built Ford Auto Assembly plant. When San Jose attempted to annex Milpitas barely seven years later, the "Milpitas Minutemen" were quickly organized to oppose annexation and keep Milpitas independent. An overwhelming majority of Milpitas registered voters voted "No" to annexation in the 1961 election as a result of a vigorous anti-annexation campaign. Following the election, the anti-annexation committee, who had compared themselves to the Revolutionary War Minutemen who fought the British on Lexington Green—a role filled in this case by the neighboring city of San Jose—adopted the image of Daniel Chester French's Minuteman statue, that stands near the site of the Old North Bridge in Concord, MA, as part of the official city seal. In the 1960s, the city approved the construction of the Calaveras overpass. Formerly at a junction with the Union Pacific railroad, Calaveras Boulevard had a bridge passing over six sets of railroad tracks after the construction was completed. Though the result was that local residents could now drive over the train tracks without waiting for a slow freight to pass, it resulted in the loss of the historical residential area. Here houses owned by city leaders had to be purchased by the city at full market value and either moved or demolished.[15]

Starting in 1955, with the construction of the Ford Motor Assembly Plant, and accelerating in the 1960s and 1970s, extensive residential and retail development took place. Hayfields in Milpitas rapidly disappeared as industries and residential housing developments spread. Soon, the once rural town of Milpitas found itself a San Jose suburb. The population jumped from about 800 in 1950 to 62,698 in 2000. Several local farmers and businessmen who had chipped in from $2 to $50 to file for incorporation, had become millionaires within ten years. Most of them then moved away.[12]

According to the book The Color of Law by Richard Rothstein (2017), when the Ford plant moved from Richmond to Milpitas in 1953, the town incorporated in order to pass laws that would exclude African American workers from residing there. "Union leaders met with Ford Executives and negotiated an agreement permitting all 1400 Richmond plant workers, including the approximately 250 African Americans, to transfer to the new facility. Once Ford's plans became known, Milpitas residents incorporated the town and passed an emergency ordinance permitting the newly installed city council to ban apartment construction and allow only single family homes. ... The Federal Housing Administration approved subdivision plans that met their specifications in Milpitas and guaranteed mortgages to qualified buyers ... One of the specifications for mortgages insured in Milpitas (as in the rest of the country at that time) was an openly stated prohibition on sales to African Americans. Because Milpitas had no apartments, and houses in the area were off-limits to black workers-though their incomes and economic circumstances were like those of whites on the assembly line-African Americans had to choose between giving up the good industrial jobs, moving to apartments in a segregated neighborhood of San Jose, or enduring lengthy commutes between North Richmond and Milpitas.[16]

In 1961, Ben F. Gross, a civil rights activist, became Milpitas's first black city councilman with the backing of the UAW. This election was recognized nationally and received attention from Look and Life magazines. In 1966, Ben F. Gross became California's first black mayor when he was elected by the city's residents and "the only black mayor of a predominantly white town in California".[17] Mayor Gross was reelected in 1968 and continued fighting against Milpitas's annexation by San Jose.

The Ford San Jose Assembly Plant closed in 1984, later being converted into a shopping mall, known as the Great Mall of the Bay Area, which opened in 1994.

In the early 21st century, the Milpitas light rail transit system station was added, making it the northeastern most light rail destination in the region. On January 26, 2004, the city celebrated the 50th anniversary of its incorporation and issued the book Milpitas: Five Dynamic Decades to commemorate 50 years of Milpitas's history as a busy, exciting crossroads community.

Etymology

[edit]The name Milpitas is the plural diminutive of milpa, Mexican Spanish for "cornfield." The name means "Place of little cornfields."[18] The word milpa is derived from the Nahuatl words milli, meaning "agricultural field," and pan, meaning "on."

The name Milpitas, perhaps used by Jose Maria Alviso to name his land grant, Rancho de las Milpitas, may have meant that there had been small Native American gardens nearby because of the rich alluvial soils of the area.[18]

The first deed of property sale in Milpitas is found in the Santa Clara County Records General Index 1850–1856 (K-143) and is dated February 14, 1856. It is Juana Galindo Alviso, widow of Jose Maria Alviso, to Michael and Ellen Hughes for 800 acres (3.2 km2) of land, today the Main Street area south of Carlo Street, although the deed gives the name of the Rancho as Rancho San Miguel, rather than as Milpitas.

Geography

[edit]Milpitas lies in the northeastern corner of the Santa Clara Valley, which is south of San Francisco. Milpitas is generally considered to be a San Jose suburb in the South Bay, a term used to denote the southern part of the San Francisco Bay Area.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 13.5 sq mi (35.0 km2). 13.5 sq mi (34.9 km2) of it is land and 0.039 sq mi (0.10 km2) of it (0.28%) is water.[3]

The median elevation of Milpitas is 19 feet (5.8 m). At Piedmont Road, Evans Road, and North Park Victoria Drive, the elevation is generally about 100 feet (30 m), while the western area is almost at sea level. The highest point in Milpitas is a 1,289-foot (393 m) peak in the southeastern foothills.

To the east of Milpitas is a range of high foothills and mountains, part of the Diablo Range which runs along the east side of San Francisco Bay. Monument Peak is a prominent summit in the eastern Milpitas hills, and is the location of antenna broadcasting television stations KICU and KQEH to the San Francisco Bay Area.

There are also many creeks in Milpitas, most of which are part of the Berryessa Creek watershed. Calera Creek, Arroyo de los Coches, Penitencia Creek and Piedmont Creek are some of the creeks that flow from the Milpitas hills and empty into the San Francisco Bay. (See Berryessa Creek)

Urban layout

[edit]

Milpitas is divided into three sections by Interstates 680 and 880. To the west of I-880 is a largely industrial and commercial area. Between I-880 and its eastern counterpart freeway, I-680, is an industrial zone in the south and residential neighborhoods in the north. Other residential neighborhoods and undeveloped mountains lie east of I-680.

In reality, Milpitas has no concentrated downtown "center," but instead has several small retail centers generally located near residential developments and anchored by a supermarket. The so-called "Midtown" area, the oldest part of Milpitas, has few remaining historic residences and was the only commercial district that existed before 1945. Midtown is situated in the region where Main and Abel Streets run parallel to each other bordered by Montague Expressway in the south and Weller Street at the north end. A USPS post office, Saint John the Baptist Catholic Church, Elementary & Junior High Catholic School, the Milpitas Public Library (which incorporates the old Milpitas Grammar School building), the Smith/DeVries mansion, the Senior Center, and Elmwood Correctional Facility are all in the Midtown section of Milpitas. The Milpitas Civic Center, which includes City Hall, is not located in Midtown, but stands at the intersection of Milpitas and Calaveras Boulevards. The Civic Center is separated from Midtown by the Calaveras overpass. The boundaries that divide major Milpitas neighborhoods and districts include Calaveras Boulevard running from east to west and the Union Pacific railroad, which runs from north to south. The newest retail centers are west of Interstate 880.

Berryessa Creek flows through Milpitas.

Pollution

[edit]Milpitas occasionally experiences odorous air traveling downwind from bay salt marshes, from the Newby Island landfill, from the anaerobic digestion facility at Zero Waste Energy Development Company, and from the San Jose sewage treatment plant's percolation ponds. Most malodorous during the autumn, it is especially pungent west of Interstate 880 because of its close location to the San Francisco Bay and the direction of the prevailing winds out of the north-northwest. The City of Milpitas would like to remedy this air quality problem to the extent it can and encourages its residents to file odor complaints.[19]

Local creeks and the nearby San Francisco Bay suffer somewhat from water pollution originating from street water runoff and industrial wastes. The creeks in Milpitas, especially Calera, Scott, and Berryessa Creeks, used to be prime fishing spots for native steelhead until pollutants from urban development and industry killed the fish starting in the 1950s. While small populations of steelhead and even salmon still may be seen in area streams these cannot legally be fished and consumption of legal catches is limited by mercury contamination.

The I-880 corridor has experienced relatively elevated levels of air pollution from freeway traffic. For example, eight-hour standards for carbon monoxide have been near to maximum levels for the last two decades.[20]

Climate

[edit]Set within a warm Mediterranean climate zone in Santa Clara County, Milpitas enjoys warm, sunny weather with few extreme temperatures. Rainfall is confined mostly to the winter months. During winter, temperatures are relatively cold, at an average of 41 to 59 °F (5 to 15 °C). Showers and cloudy days come and go during this season, dropping most of the city's annual 15 inches (380 mm) of precipitation, and as spring approaches, the gentle rains gradually dwindle. In summer, the grasslands on the hillsides dehydrate rapidly and form bright, golden sheets on the mountains set off by stands of oak. Summer is dry and warm but not hot like in other parts the Bay Area. Temperatures infrequently reach over 100 °F (38 °C), with most days in the low 80s to the mid 80s. From June to September, Milpitas experiences little rain, and as autumn approaches, the weather gradually cools down. Many temperate-climate trees drop their leaves during fall in the South Bay but the winter temperature is warm enough for evergreens like palm trees to thrive.

| Climate data for Milpitas, California | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 79 (26) |

81 (27) |

89 (32) |

95 (35) |

101 (38) |

109 (43) |

108 (42) |

105 (41) |

109 (43) |

106 (41) |

85 (29) |

79 (26) |

109 (43) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 58 (14) |

63 (17) |

68 (20) |

72 (22) |

76 (24) |

82 (28) |

84 (29) |

84 (29) |

82 (28) |

75 (24) |

65 (18) |

58 (14) |

72 (22) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 41 (5) |

44 (7) |

46 (8) |

48 (9) |

53 (12) |

56 (13) |

58 (14) |

58 (14) |

56 (13) |

50 (10) |

45 (7) |

40 (4) |

50 (10) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 24 (−4) |

26 (−3) |

30 (−1) |

35 (2) |

37 (3) |

42 (6) |

47 (8) |

47 (8) |

42 (6) |

36 (2) |

21 (−6) |

19 (−7) |

19 (−7) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.03 (77) |

2.84 (72) |

2.69 (68) |

1.02 (26) |

0.44 (11) |

0.10 (2.5) |

0.06 (1.5) |

0.07 (1.8) |

0.23 (5.8) |

0.87 (22) |

1.73 (44) |

2.00 (51) |

15.08 (383) |

| Source: [21] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 | 6,572 | — | |

| 1970 | 26,561 | 304.2% | |

| 1980 | 37,820 | 42.4% | |

| 1990 | 50,686 | 34.0% | |

| 2000 | 62,698 | 23.7% | |

| 2010 | 66,790 | 6.5% | |

| 2020 | 80,273 | 20.2% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[22] | |||

| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[23] | Pop 2010[24] | Pop 2020[25] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 14,917 | 9,751 | 7,795 | 23.79% | 14.60% | 9.71% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 2,187 | 1,836 | 1,577 | 3.49% | 2.75% | 1.96% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 240 | 137 | 100 | 0.38% | 0.21% | 0.12% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 32,281 | 41,308 | 57,260 | 51.49% | 61.85% | 71.33% |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 347 | 316 | 319 | 0.55% | 0.47% | 0.40% |

| Other race alone (NH) | 131 | 93 | 332 | 0.21% | 0.14% | 0.41% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | 2,178 | 2,109 | 2,304 | 3.47% | 3.16% | 2.87% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 10,417 | 11,240 | 10,586 | 16.61% | 16.83% | 13.19% |

| Total | 62,698 | 66,790 | 80,273 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

2020

[edit]The 2020 United States census reported that Milpitas had a population of 80,273. The population density was 5,954.1 inhabitants per square mile (2,298.9/km2). The racial makeup of Milpitas was 11.3% White, 2.1% African American, 0.6% Native American, 71.7% Asian, 0.4% Pacific Islander, 7.5% from other races, and 6.3% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 13.2% of the population.[26]

The census reported that 97.9% of the population lived in households, 0.2% lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 1.9% were institutionalized.[26]

There were 24,480 households, out of which 41.4% included children under the age of 18, 63.2% were married-couple households, 4.1% were cohabiting couple households, 17.3% had a female householder with no partner present, and 15.3% had a male householder with no partner present. 12.9% of households were one person, and 4.2% were one person aged 65 or older. The average household size was 3.21.[26] There were 19,428 families (79.4% of all households).[27]

The age distribution was 21.1% under the age of 18, 7.4% aged 18 to 24, 35.7% aged 25 to 44, 23.7% aged 45 to 64, and 12.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36.4 years. For every 100 females, there were 105.2 males.[26]

There were 25,183 housing units at an average density of 1,867.9 units per square mile (721.2 units/km2), of which 24,480 (97.2%) were occupied. Of these, 58.6% were owner-occupied, and 41.4% were occupied by renters.[26]

In 2023, the US Census Bureau estimated that the median household income was $176,822, and the per capita income was $67,448. About 3.6% of families and 5.4% of the population were below the poverty line.[28]

2010

[edit]The 2010 United States census[29] reported that Milpitas had a population of 66,790. The population density was 4,896.5 inhabitants per square mile (1,890.5/km2). The racial makeup of Milpitas was 13,725 (20.5%) White, 1,969 (2.9%) African American, 309 (0.5%) Native American, 41,536 (62.2%) Asian, 346 (0.5%) Pacific Islander, 5,811 (8.7%) from other races, and 3,094 (4.6%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 11,240 persons (16.8%).

The Census reported that 64,092 people (96.0% of the population) lived in households, 104 (0.2%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 2,594 (3.9%) were institutionalized.

There were 19,184 households, out of which 8,616 (44.9%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 12,231 (63.8%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 2,279 (11.9%) had a female householder with no husband present, 1,105 (5.8%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 760 (4.0%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 100 (0.5%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 2,470 households (12.9%) were made up of individuals, and 742 (3.9%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.34. There were 15,615 families (81.4% of all households); the average family size was 3.61.

The population was spread out, with 15,303 people (22.9%) under the age of 18, 5,887 people (8.8%) aged 18 to 24, 21,827 people (32.7%) aged 25 to 44, 17,434 people (26.1%) aged 45 to 64, and 6,339 people (9.5%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36.1 years. For every 100 females, there were 104.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 104.6 males.

There were 19,806 dwelling units at an average density of 1,452.0 per square mile (560.6/km2), of which 12,825 (66.9%) were owner-occupied, and 6,359 (33.1%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 1.2%; the rental vacancy rate was 3.1%. 42,501 people (63.6% of the population) lived in owner-occupied dwelling units and 21,591 people (32.3%) lived in rental housing units.

Economy

[edit]

Milpitas has a relatively large percent of residents employed in the computer and electronic products industry. 34.1% of men[30] and 26.9% of women[31] are employed in this industry.

While over 75% of people who live in Milpitas work out of the city; the daytime population of Milpitas actually increases by nearly 20% as there are more people living in other cities who work in Milpitas than people living in Milpitas who work in other cities.[32] This results in heavy traffic commutes along key arterial roads twice each day.[33]

Milpitas is home to the headquarters of Adaptec, Aerohive Networks, FireEye, Intersil, SonicWall, IXYS Corporation, Viavi Solutions and Lumentum Holdings (formerly JDSU), KLA-Tencor, Linear Technology, LTX-Credence, SCA, Sigma Designs, and Flex. Many other companies have corporate offices in Milpitas including Hewlett Packard Enterprise, Western Digital, Cisco Systems, Renesas, Infineon Technologies, Varian Medical Systems, Teledyne, Quantum, LifeScan, and Johnson & Johnson Vision.

Milpitas is also home to one of Santa Clara County's two correctional facilities, the Elmwood Correctional Facility,[34] which houses over 3,000 inmates.[35]

Top employers

[edit]According to the city's 2020 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[36] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cisco Systems | 3,347 |

| 2 | KLA Corporation | 2,223 |

| 3 | Flex | 2,732 |

| 4 | Sandisk | 1,913 |

| 5 | Linear Technology | 1,283 |

| 6 | Milpitas Unified School District | 811 |

| 7 | Headway Technologies | 735 |

| 8 | FireEye | 528 |

| 9 | Walmart | 439 |

| 10 | Kaiser Permanente Medical Offices | 361 |

Arts and culture

[edit]

Milpitas residents enjoy various visual and performing arts. The Milpitas Alliance for the Arts, founded in 1997, is an organization that promotes and funds murals, plays, sculptures, and many other forms of art. The "Art in Your Park" project has put many sculptures in local Milpitas parks, including a ceramic tower in Hillcrest Park, a sundial in Augustine Park, and a historical memorial in Murphy Park. The Celebrate Milpitas Festival is held annually every August, featuring vendors of crafts-type merchandise and providing local talent with a performance venue while selling visitors samplings of exotics like garlic fries or lumpia and even offerings from one or two Californian wineries. The suburb offers a rich variety of food options, including sit-down restaurants and fast food.

The Santa Clara County Library system operates the Milpitas public library.[37]

Retail

[edit]Milpitas is home to the largest Bay Area enclosed shopping mall (in terms of land area), the Great Mall of the Bay Area. The Great Mall is a part of the Simon Property Group and is the biggest mall/outlet shopping center in northern California. There are approximately 200 stores in the mall, with a total of 1,357,000 square feet (126,100 m2) of retail area.

Milpitas is also home to the first and largest power center in Santa Clara County, McCarthy Ranch Marketplace, which was built in 1994.

A large outdoor shopping center called Milpitas Square is west of Interstate 880. Another shopping center in Milpitas is The Seasons Marketplace. Other Milpitas shopping centers and plazas include Ulferts Center, Milpitas Town Center, Jacklin Square, Parktown Plaza, Beresford Square, and the City Square.

In the past, Milpitas had a very different culture from that of its modern suburban state. As late as the 1950s, Milpitas was an unincorporated rural town with the Midtown district on Main Street as its main center of business and social activities. Many old businesses include Main Street Gas (operated by the Azorean Spangler brothers), Smith's Corner Saloon, and Kozy Kitchen. The Cracolice Building was one of the oldest commercial buildings in Milpitas and was the site of many political conventions and meetings. "As Milpitas Goes, So Goes the State" used to be a popular slogan around the town. Most of the land now within modern-day Milpitas's boundaries was used for strawberry, asparagus, apricot, and potato cultivation until the postwar boom during the 1950s and 1960s.

Parks and recreation

[edit]

The city has many athletic and educational recreational programs which are located in several city buildings, including the city's sports center, teen center, library, community center, and senior center.

Parks

[edit]

Ed R. Levin County Park is the largest county regional park near Milpitas. The County of Santa Clara Parks and Recreation Department runs the park. Monument Peak can be accessed through trails that lead north through the county park. The park also provides facilities for hang gliding and paragliding and includes a newly built dog park that was a joint effort by the county and the city of Milpitas. Two golf courses, Spring Valley Golf Course and Summitpointe Golf Course, are located in the Milpitas foothills. Both have expensive gated residential developments located adjacent to them. Milpitas itself has 17 traditional neighborhood parks which are generally 3 to 10 acres (12,000 to 40,000 m2). There also is a sports complex with two swimming pools and sports parks with baseball and tennis play areas fenced off. There are also smaller parks of less than 3 acres (12,000 m2) scattered in newer developments. Milpitas has begun to develop the San Francisco Water District's Hetch Hetchy right-of-way as park land in lieu of using land from new high density residential developments adjacent to it. Together, these parks total 166 acres (670,000 m2) of land area or less than 2% of the city's acreage. The Milpitas City Council voted February 16, 2016, to designate Jacaranda mimosifolia as Milpitas's official city tree.[38]

Government

[edit]Local

[edit]The city has a Council–manager government headed by five-member city council consisting of a mayor, a vice mayor, and three councilmembers. As of April 26, 2024, the mayor is Carmen Montano, the vice mayor is Evelyn Chua, and the councilmembers are Hon Lien, Garry Barbadillo and Anthony Phan. The city manager is Steven McHarris. The city attorney is Christopher Diaz. The police chief is Armando Corpuz. The fire chief is Brian Sherard.

The Milpitas Town Seal was the idea of former Councilman and Vice Mayor John McDermott, who came up with the idea for a seal of the Minuteman from one of his son's history textbooks. He designed the seal and took it to Arnie's Signs and had 4,000 decals made.[39] The city's seal shows Daniel Chester French's Minuteman statue, musket in hand, standing in the Santa Clara Valley, with the golden hills of Milpitas rising to the east. He faces defiantly south toward San Jose because early residents of Milpitas considered themselves minutemen when they defeated efforts by San Jose to annex the newly incorporated Milpitas.

State and federal

[edit]In the California State Legislature, Milpitas is in the 10th senatorial district, represented by Democrat Aisha Wahab, and in the 24th Assembly district, represented by Democrat Alex Lee.[40]

In the United States House of Representatives, Milpitas is in California's 17th congressional district, represented by Democrat Ro Khanna.[41]

Milpitas Vs. San Jose

[edit]In 2015, the city of Milpitas challenged a decision by the city of San Jose to expand the Newby Island landfill on the border of the two cities. Residents of Milpitas have complained about the smell of the landfill, which is located underneath a highway leading to San Jose and Fremont. The courts upheld San Jose's position and approved the expansion.[42]

In 2016, Republic Services, owner of the Newby Island landfill, settled a class-action lawsuit over the alleged landfill odor pollution. Republic will create a $1.2 million fund to be paid to households within a 1.5-mile (2.4 km) radius from the landfill. In addition, Republic agreed to provide $2 million to mitigate odors over the next five years. Odor mitigation will include updating the gas collection system and also modifying the composting operation to use forced air static piles.[43][44]

Education

[edit]Primary and secondary schools

[edit]

From 1912 to 1956, students attended Milpitas Grammar School—now a city library.[45] Additional schools were built, administered by the Milpitas Elementary School District.[45][46] In 1968, the community voted to combine the city schools as part of the Milpitas Unified School District.[45] District schools include:[47]

- Burnett Elementary

- Calaveras Hills High School

- Curtner Elementary

- Milpitas Adult Education

- Milpitas High School

- Milpitas Middle College High School

- Mattos Elementary

- Pomeroy Elementary

- Rancho Middle School

- Randall Elementary

- Rose Elementary

- Russell Middle School

- Sinnott Elementary

- Spangler Elementary

- Weller Elementary

- Zanker Elementary

Infrastructure

[edit]Roads

[edit]From north to south, the major east–west roads in Milpitas are Dixon Landing Road, Jacklin Road, Calaveras Boulevard, and Landess Avenue/Montague Expressway. From east to west, the major north–south roads are Piedmont Road, Evans Road, Park Victoria Drive, Milpitas Boulevard, Main Street, Abel Street, and McCarthy Boulevard. Milpitas roads that reach into the hills are, from north to south, Country Club Drive, Old Calaveras Road, Calaveras Road, and a private ranch drive, the historic Urridias Ranch Road.

As with many other Californian suburbs, Milpitas has divided roads that are maintained well by the local city government. Street signs are in green. Like the San Jose public works system, all pedestrians must manually press a button in order to turn the pedestrian signal lights on (unlike the South Bay cities, San Francisco has automatic pedestrian lights at intersections and does not have "press to cross" buttons for pedestrians).

Not all streets in Milpitas have bicycle lanes or sidewalks. It has a walk score of 48.[48] Piedmont Road, Evans Road, and Jacklin Road have excellent bike lanes and sidewalks with ample spacing, but Montague Expressway and South Milpitas Boulevard have limited sidewalks and narrow bike lanes, which causes some problems for workers commuting by bike or on foot.

Interstate 680 and Interstate 880 lead north to Fremont and south to downtown San Jose. State Route 237 begins at Milpitas and goes west to Sunnyvale and Mountain View.

Public transportation

[edit]The city is served by the Milpitas BART station, which opened for service as part of Phase I of the Silicon Valley BART extension on June 13, 2020. The station is located near the city limits of San José, and is bounded on two sides by the Montague Expressway and Capitol Ave. A pedestrian bridge runs over Capitol Ave and connects the BART station with VTA's Milpitas light rail station (formerly known as Montague station).[49]

The Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority (VTA) runs light rail and local buses for public transportation. Three light rail stations lie within city limits: Milpitas, Great Mall, and Alder, all on the Orange Line. VTA bus routes in Milpitas are 46, 47, 60, 66, 70, 71, 77.[50]

The nearest major airport to the city is the San Jose International Airport (SJC), less than ten minutes away in San José. The city is also served by the general aviation Reid–Hillview Airport in East San Jose.

Milpitas borders salt ponds on the San Francisco Bay in the extreme northwest, but has no boat access. Alviso, a neighborhood in San José and formerly a neighboring city, has a marina and boat launch that allows motorized and non-motorized boats access to the bay.

China Airlines formerly operated a bus service to San Francisco International Airport for flights to Taipei, Taiwan.[51]

Communications

[edit]The USPS post office on Abel Street is Milpitas's main office for postal mail and is the only USPS post office in the city. ZIP code 95035 is exclusively for Milpitas and is the only standard ZIP code for the city. 95036 is a new ZIP that is used sometimes for post office boxes in Milpitas. Until the merger with SBC, Milpitas had relied on Pacific Bell for its telecommunications services. American Telegraph and Telephone (AT&T) acquired Southern Bell (SBC) in 2006 and became the landline telephone provider in the city. As part of the agreement for the merger of AT&T with SBC, Milpitas residents were offered high-speed DSL internet access from AT&T for only $10 per month until December 2009, although few residents were aware of the offer.

On Earth Day, April 22, 2009, the public-private partnership Silicon Valley Unwired announced the rollout of a free municipal WiFi wireless network for the entire city. After the Google WiFi network in Mountain View, it is the second municipal wireless network, providing free Internet access.

Notable people

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2024) |

- Kim Bokamper – Miami Dolphins football player

- Brandon Carswell – former USC football player

- Mark Foster – lead singer of Foster the People[52]

- Lenzie Jackson – NFL football player

- Jeannie Mai – TV personality

- Deltha O'Neal – NFL football player

- Tab Perry – NFL football player

- Vita Vea – NFL football player for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers

- Andy Weir – science fiction writer, author of The Martian[53]

- Cori Close - UCLA Women's Basketball head coach

In popular culture

[edit]The Milpitas Monster was filmed in the town in 1976. Originally started as a high school project, it developed into a feature-length film. In the quiet town of Milpitas, California, a gigantic creature is spawned in a polluted, overflowing waste disposal site. The townspeople rally to destroy the creature, which has an uncontrollable desire to consume large quantities of garbage cans.

The movie River's Edge was inspired by the murder of Marcy Renee Conrad in Milpitas in 1981.

John Darnielle's 2022 novel Devil House takes place in Milpitas.

Sister cities

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on October 17, 2013. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "City Council". City of Milpitas. Retrieved October 10, 2025.

- ^ a b "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ "Milpitas". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- ^ "Milpitas (city) QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "US Census Bureau 2020 QuickFacts: Milpitas, CA".

- ^ Marvin-Cunningham (1990)

- ^ Editors of the Milpitas History Homepage . "The Milpitas History Homepage". Milpitashistory.org. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ Steve Munzel (January 24, 2003). "Higuera Adobe". Milpitashistory.org. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ Loomis (1986)

- ^ Steve Munzel (January 24, 2003). "Weller Palm". Milpitashistory.org. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ a b Steve Munzel (January 24, 2003). "Maple Hall". Milpitashistory.org. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ Steve Munzel (January 24, 2003). "Smith's Corners". Milpitashistory.org. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ Steve Munzel (January 24, 2003). "Kozy Kitchen". Milpitashistory.org. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ Devincenzi (2004)

- ^ Rothstein, Richard (2017). The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. Liveright Publishing. pp. 19–20. ISBN 9781631492860 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Ben Gross (1921–) | The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed". The Black Past. December 11, 2008. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ a b Ann Zeise. "How Milpitas Got Its Name". Go Milpitas. Ann Zeise:Go Mipitas!. Archived from the original on January 4, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ Report to the Mayor and City Council on Odor Control in Milpitas January 18, 2011, by: Kathleen Phalen, Utility Engineer

- ^ C. Michael Hogan, Marc Papineau, Ballard George et al., Environmental Assessment of the I880/Dixon Landing Road Interchange Improvement Project, Cities of Fremont and Milpitas, Earth Metrics Incorporated, Federal Highway Administration Publication, March 1989

- ^ "weather.com". Retrieved September 14, 2010.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "P004: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Milpitas city, California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Milpitas city, California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Milpitas city, California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "Milpitas city, California; DP1: Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics - 2020 Census of Population and Housing". US Census Bureau. Retrieved June 27, 2025.

- ^ "Milpitas city, California; P16: Household Type - 2020 Census of Population and Housing". US Census Bureau. Retrieved June 27, 2025.

- ^ "Milpitas city, California; DP03: Selected Economic Characteristics - 2023 ACS 5-Year Estimates Comparison Profiles". US Census Bureau. Retrieved June 27, 2025.

- ^ "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA - Milpitas city". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ^ "Top 101 cities with largest percentage of males working in industry: Computer and electronic products (population 5,000+)". City-Data. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

- ^ "Top 101 cities with largest percentage of females working in industry: Computer and electronic products (population 5,000+)". City-Data. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

- ^ "Milpitas City Statistics". City-Data. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

- ^ "Milpitas Community-Based Transportation Plan" (PDF). Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

- ^ "Elmwood Jail, Santa Clara County Correctional Facilities". Go Milpitas. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "About Us - Correction, Department of (DEP)". Archived from the original on October 15, 2007.

- ^ "Comprehensive Annual Financial Report : For the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2020" (PDF). ci.milpitas.ca.gov.

- ^ "Milpitas Library Welcome Page". Archived from the original on December 1, 1998.

- ^ Mohammed, Aliyah (February 24, 2016). "Milpitas: Council approves colorful Jacaranda Mimosifolia tree as official city tree". The Mercury News. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

- ^ "Milpitas History". Milpitas Historical Society. April 1, 2012. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "Final Maps | California Citizens Redistricting Commission". Retrieved October 10, 2025.

- ^ "California's 17th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC. Retrieved October 10, 2025.

- ^ "City of Milpitas v. City of San Jose, H040664 | Casetext Search + Citator". casetext.com. Archived from the original on October 4, 2023. Retrieved December 8, 2022.

- ^ Bauer, Ian (July 25, 2016). "Milpitas: Judge finalizes settlement in class-action suit over alleged landfill odors". The Mercury News. Archived from the original on March 5, 2017. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- ^ "Peter Ng, et al. v. International Disposal Corp. of California, et al. - Liddle & Dubin, P.C." www.ldclassaction.com. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- ^ a b c "History". Milpitas Unified School District. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ^ "Milpitas Unified School District" (PDF). California State Treasurer's Office. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ "Our Schools". Milpitas Unified School District. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ^ "Milpitas neighborhoods on Walk Score". WalkScore.

- ^ "BART finally comes to San Jose Saturday: What you need to know about the new stations". The Mercury News. June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- ^ "Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority". Retrieved March 17, 2024.

- ^ "Archived copy". www.china-airlines.com. Archived from the original on May 24, 2005. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Snapchat from Mark Foster on a Fan page". June 2, 2016. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- ^ Vallone, Julie (November 2015). ""The Man From Mars"" (PDF). South Bay Accent. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]The following books on Milpitas have been used as significant references for this article. Many of the books are not available at a regular store or are out of print, but all are available at the Milpitas branch of the Santa Clara County Library. These books are also recommended as resources for further reading.

- Burrill, Robert L. (2005). Milpitas. Images of America Series. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-2910-3.

- Craig, Madge (1976). History of Milpitas: Sketch by Beverly Craig.

- Devincenzi, Robert J.; Thomas Gilsenan; Morton Levine (2004). Milpitas: Five Dynamic Decades. City of Milpitas. ISBN 978-0-9748858-0-3.

- Loomis, Patricia (1986). Milpitas: the century of "little cornfields," 1852-1952. California History Center. ISBN 978-0-935089-07-3.

- Marvin-Cunningham, Judith; Paula Juelke Carr (1990). Historic Sites Inventory, Milpitas, California 1990. City of Milpitas.

External links

[edit]Milpitas, California

View on GrokipediaMilpitas is a city in Santa Clara County, California, situated in the East Bay portion of the San Francisco Bay Area adjacent to San Jose and Fremont.[1] Incorporated on January 26, 1954, the city transitioned from a small agricultural community of around 800 residents to a suburban hub driven by postwar development and proximity to emerging high-technology centers.[2] As of July 2024, Milpitas has an estimated population of 79,746, reflecting modest decline from its 2020 census count of 80,273 amid broader regional housing pressures.[3] The local economy centers on manufacturing and professional, scientific, and technical services, employing over 42,000 workers, with major employers including Cisco Systems, KLA Corporation, and Flex, contributing to a daytime population swell to approximately 118,000 due to its role in research, development, and innovation within Silicon Valley.[1][4] Demographically, the city features a predominantly Asian population comprising about 72% of residents, alongside a median household income of $176,822 in 2023 dollars, indicative of its affluent, skilled workforce attracted by tech opportunities.[3][5] Notable landmarks include the Great Mall of the Bay Area, one of the largest indoor outlets in Northern California, and recreational areas like Ed Levin County Park, underscoring Milpitas' blend of commercial vitality and suburban appeal.[1]

History

Early settlement and land use

The territory comprising present-day Milpitas was originally occupied by Ohlone indigenous groups, who subsisted through hunting, gathering acorns and seeds, and seasonal exploitation of the region's riparian and grassland resources prior to Spanish colonization.[6] European settlement commenced under Spanish and Mexican administration, with the area incorporated into large ranchos following the secularization of Mission San José in 1834, which redistributed former mission lands for private grazing.[7] Between 1821 and 1839, Mexican authorities issued four principal land grants that delineated much of Milpitas' boundaries: Rancho Tularcitos to José Higuera in 1821, Rancho Milpitas to José Maria Alviso on September 23, 1835, and additional grants including portions overlapping with Rancho de las Pulgas and Rancho Los Coches.[8] [9] The Rancho Milpitas grant specifically encompassed the tract where Alviso constructed his adobe residence, serving as the foundational settlement nucleus.[9] Land use during this era centered on extensive cattle ranching, with grantees maintaining herds numbering in the thousands for the production of hides and tallow—primary commodities in California's hide-and-tallow economy that supplied New England markets via Pacific ports.[7] The fertile alluvial soils of the Santa Clara Valley supported grassland pastures ideal for livestock, while limited arable areas permitted subsistence cultivation of wheat, corn, and vegetables by vaqueros and their families.[2] This pastoral orientation persisted until the mid-19th century, when American land claims processes and population influx prompted fragmentation of ranchos into smaller farms.[8]Incorporation and name origins

![José María Alviso Adobe][float-right] The name Milpitas originates from the Spanish word milpa, a term derived from Nahuatl meaning "cornfield" or cultivated field, with the diminutive suffix -itas indicating "little cornfields" or "place of small fields." This nomenclature reflects the area's early agricultural character, particularly its use for growing maize and other crops during the Mexican era. The designation traces back to Rancho Milpitas, a land grant of approximately 3,689 acres awarded by the Mexican government to Californio ranchero José María Alviso on November 24, 1835, encompassing much of the present-day city.[10][11] Prior to formal municipal status, the Milpitas area functioned as an unincorporated township within Santa Clara County, serving as a rural outpost with farms, orchards, and a stagecoach stop along the route from San Jose to Livermore. Incorporation efforts gained momentum in the early 1950s amid rapid postwar population growth and industrial development, including the establishment of a Ford Motor Company assembly plant in 1953, which attracted workers and heightened annexation pressures from the expanding city of San Jose. Residents voted to incorporate on January 26, 1954, establishing Milpitas as an independent general-law city under a council-manager form of government to preserve local control over zoning, services, and development. This defensive measure succeeded in maintaining autonomy, with the new city boundaries including the Ford facility and surrounding farmlands.[12][13]Postwar expansion and industrialization

The establishment of the Ford Motor Company's San Jose Assembly Plant marked the onset of Milpitas' postwar industrialization. Opened on May 17, 1955, after relocation from the outdated Richmond facility to meet surging postwar automobile demand, the plant spanned expansive acreage previously used for agriculture, such as cornfields.[13][14] At its peak, it employed nearly 6,000 workers and produced 135,963 vehicles in 1962 alone, providing stable, high-wage manufacturing jobs that drew laborers from surrounding areas.[12][14] This development directly spurred infrastructural and economic shifts, as the city's incorporation on January 26, 1954, had positioned it to annex the plant site and capitalize on industrial zoning.[12] The Ford plant's operations triggered rapid residential expansion to house incoming workers, converting rural landscapes into suburban tracts. Housing projects like Sunnyhills, developed in 1956 as one of the nation's earliest planned racially integrated communities through a United Auto Workers cooperative, exemplified this boom, accommodating diverse factory employees.[13][12] Population growth accelerated accordingly, with the city reaching 27,149 residents by the 1970 census, a reflection of the causal link between manufacturing employment and demographic influx.[15] Local commerce followed, as stores and services proliferated to serve the expanded workforce, fundamentally altering Milpitas from a sparse agricultural outpost to a burgeoning industrial hub.[13] By the 1960s, industrialization diversified beyond automobiles into electronics, as firms like IBM and National Semiconductor established facilities, leveraging proximity to emerging Silicon Valley talent pools and infrastructure.[16] This transition built on the foundational manufacturing base from the Ford era, with industrial zoning expansions—such as the Western Pacific Railroad's division of 1,500 acres south of Calaveras Road—facilitating further factory sites and reinforcing Milpitas' role in regional economic growth.[17] The cumulative effect positioned the city for sustained expansion, though initial reliance on heavy industry like Ford underscored vulnerabilities to market fluctuations evident by the 1970s.[13]Tech boom and modern growth

The tech boom in Milpitas began in the 1960s, as companies like IBM and National Semiconductor established operations in the city, drawn by available land and proximity to emerging Silicon Valley infrastructure.[16] This shift from agriculture and postwar manufacturing to high-technology sectors accelerated industrialization, with semiconductor fabrication and electronics assembly becoming dominant by the 1970s.[16] The city's strategic location facilitated rapid expansion, contributing to a population surge from approximately 37,000 in 1970 to over 50,000 by 1980, directly tied to job creation in these industries.[18] By the 1980s, Milpitas solidified its role in the high-tech ecosystem, hosting research and development (R&D) facilities alongside production sites for firms in semiconductors and networking equipment.[19] This period saw the city evolve into a manufacturing hub, with over one-fifth of the workforce engaged in advanced manufacturing by the 2010s.[4] Major employers included companies like Infineon Technologies and VIAVI Solutions, focusing on components for telecommunications and cybersecurity.[20] Economic development emphasized innovation, expanding the daytime population to about 118,000 as commuters flocked to approximately 41,000 high-tech and professional jobs.[4] Modern growth has sustained this trajectory, with Milpitas attracting data centers, clean energy tech, and electric vehicle manufacturing amid Silicon Valley's broader digital economy expansion.[21] In recent years, firms like Rivian announced facilities for EV production, reinforcing the city's appeal for capital-intensive tech operations.[22] Population continued rising, reaching 81,773 by 2023, with a 0.17% annual increase attributed to sustained employment opportunities despite regional housing pressures.[18] Of the top employers as of 2015, seven out of ten were technology firms, underscoring the sector's enduring dominance in local economic output.[19]Recent developments and challenges

In 2023, Milpitas adopted the Milpitas Metro Specific Plan, which encompasses the Innovation District and includes provisions for a Parks and Trails Master Plan; community input on this plan was solicited in September 2025 to guide enhancements in green spaces and connectivity.[23] The city's 2025 State of the City address reported $3.1 million invested in upgrading 13 parks with new playgrounds, paths, and restrooms, alongside road safety improvements through infrastructure projects.[24] The Milpitas Gateway-Main Street Specific Plan targets infill development in four focus areas along Main Street and Calaveras Boulevard to accommodate future commercial and residential growth.[25] A zoning code update approved in August 2025 facilitates increased housing density to address regional demands.[26] The 2023-2031 Housing Element projects approximately 300 new affordable units from existing pipeline developments, amid broader General Plan updates anticipating up to 11,186 additional housing units and significant population growth by 2040.[27][28] In 2023, the city council banned natural gas infrastructure in all new buildings to advance electrification goals and enhanced rideshare programs for transit efficiency.[29] The operational Milpitas BART station, part of the 2020 Berryessa extension, continues to integrate with local transit planning, while Phase II extensions toward downtown San Jose remain in development.[30] Persistent challenges include traffic congestion exacerbated by proposed housing expansions, with residents in February 2025 opposing developments citing strains on roadways and quality of life.[31] A 2023 traffic safety survey identified priorities for improvements, reflecting ongoing commuter pressures in the Silicon Valley corridor.[32] Affordable housing construction faces primary barriers in funding, despite low rental and ownership vacancy rates driving high costs and special needs for supportive units.[33][34] Community forums in September 2025 addressed local crime trends and prevention strategies, underscoring efforts to maintain safety amid urban growth.[35]Geography

Location and physical features

Milpitas occupies 13.48 square miles of land in the northeastern portion of Santa Clara County, California, within the San Francisco Bay Area.[3] The city is situated at approximately 37°25′42″N 121°54′27″W, bordering the city of Fremont to the north in Alameda County, San Jose to the south and southwest, and unincorporated lands of Santa Clara County to the east.[36][37] It lies near the southern tip of San Francisco Bay, approximately 45 miles southeast of downtown San Francisco and 10 miles north of downtown San Jose.[37] The terrain consists primarily of flat alluvial plains typical of the Santa Clara Valley floor, with a median elevation of 19 feet (6 meters) above sea level.[38] Elevations rise gradually eastward toward the foothills of the Diablo Range, reaching about 100 feet (30 meters) along areas like Piedmont Road and North Park Victoria Drive.[38] The western and central parts remain low-lying, facilitating urban development, while the eastern boundary includes hilly terrain preserved in public parks such as Ed Levin County Park.[39] Water coverage accounts for 0.04 square miles, including minor streams and reservoirs influenced by proximity to Calaveras Reservoir to the east.[3]Climate patterns

Milpitas has a warm-summer Mediterranean climate under the Köppen classification (Csb), featuring mild temperatures year-round, with cooler, wetter winters and warmer, drier summers moderated by proximity to the Pacific Ocean and San Francisco Bay.[40][41] Average annual temperatures fluctuate between lows of 42°F and highs of 80°F, with minimal extremes due to the region's marine influence that prevents severe heat or cold snaps.[42] Precipitation averages 15 inches annually, concentrated primarily in the winter months from November to March, when Pacific storms bring the bulk of rainfall, often in intermittent events rather than prolonged downpours.[42][43] Summers, from June to September, are arid with negligible rain, low humidity, and frequent morning fog layers that typically dissipate by midday, yielding clear afternoons and evenings.[43] Winters occasionally dip below freezing at night, with rare light frost, but daytime highs seldom fall below 60°F in January, the coolest month. Seasonal variations reflect California's broader semi-arid patterns, including periodic droughts that have intensified in recent decades, though Milpitas benefits from relatively stable conditions compared to more exposed inland valleys.[44] Daily summer highs climb from 77°F in June to 83°F in September, while winter precipitation supports brief green-up before the dry season resumes.[45]Environmental quality and pollution

Milpitas' air quality is generally satisfactory, with current Air Quality Index (AQI) readings often in the "good" range (0-50), though regional influences from traffic, industrial emissions, and wildfires contribute to periodic elevations in fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and ground-level ozone. Projections indicate approximately 15 days annually with AQI exceeding 100, deemed unhealthy for sensitive populations, aligning with Santa Clara County's average of 10 unhealthy PM2.5 days and 3 for ozone per year, as reported by health assessments.[46][47] Local monitoring initiatives, including community-deployed sensors, have enhanced detection of hyper-local pollutants near industrial zones, revealing disparities in exposure that exceed broader EPA regional averages during inversion events or high-traffic periods.[48][49] Drinking water in Milpitas, supplied primarily by the Santa Clara Valley Water District through a blend of groundwater, imported surface water from the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, and recycled sources, meets federal standards but shows trace contaminants linked to urban and industrial legacies. The 2019 consumer confidence report documented arsenic at 0.004 mg/L (below the 0.010 mg/L maximum contaminant level) and hexavalent chromium detections, attributed to natural geology and past manufacturing runoff, with ongoing treatment via filtration and corrosion control. Urban stormwater runoff introduces pollutants such as heavy metals, pathogens, and sediments into local creeks like Berryessa and Penitencia, prompting annual mitigation under the Santa Clara Valley Urban Runoff Pollution Prevention Program, which logged over 1,000 illicit discharge investigations region-wide in FY 2023-24.[50][51][52] Hazardous waste management reflects Milpitas' industrial profile, with two active non-National Priorities List (non-NPL) sites, including the North American Transformer facility at 1200 Piper Drive, stemming from historical transformer manufacturing involving polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and oils. No sites in Milpitas appear on the EPA's National Priorities List, unlike adjacent Silicon Valley areas with groundwater plumes from semiconductor solvents like trichloroethylene, though proximity necessitates vigilant monitoring for migration risks. County programs facilitate household hazardous waste disposal, collecting thousands of pounds annually to curb improper releases into sewers or landfills, amid broader efforts to reduce pollution burdens in diverse communities.[53][54]Demographics

Population trends and projections

Milpitas experienced significant population growth following its incorporation in 1954, driven initially by postwar suburban expansion and proximity to emerging industrial opportunities in Santa Clara County. Decennial U.S. Census data reflect this trajectory, with the population increasing from 6,572 in 1960 to 27,149 in 1970, a more than fourfold rise attributable to residential development and manufacturing influx. Subsequent decades showed steadier but consistent expansion: 37,784 in 1980, 50,686 in 1990, 62,698 in 2000, 66,790 in 2010, and 80,273 in 2020.[15]| Census Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1960 | 6,572 |

| 1970 | 27,149 |

| 1980 | 37,784 |

| 1990 | 50,686 |

| 2000 | 62,698 |

| 2010 | 66,790 |

| 2020 | 80,273 |

Racial, ethnic, and immigrant composition

As of the 2023 American Community Survey estimates, Milpitas' population of approximately 77,321 residents is predominantly Asian, comprising 71.9% of the total, which aligns with the city's proximity to Silicon Valley and its appeal to high-skilled immigrants in technology sectors.[3] Non-Hispanic Whites account for 9.6%, while the Hispanic or Latino population (of any race) stands at 13.4%, reflecting a mix of Central American and Mexican origins common in the broader Bay Area.[3] [1] Black or African American residents make up 2.0%, American Indian and Alaska Native 0.3%, Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander 0.1%, and those identifying with two or more races 6.7%.[3]| Race or Ethnicity (Alone or in Combination) | Percentage (2019-2023 ACS) |

|---|---|

| Asian | 71.9% |

| White | 11.6% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 13.4% |

| Black or African American | 2.0% |

| Two or More Races | 6.7% |

| American Indian and Alaska Native | 0.3% |

| Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander | 0.1% |

Income, housing, and socioeconomic data

The median household income in Milpitas stood at $176,822 (in 2023 dollars) for the 2019–2023 period, substantially exceeding the national median of $75,149.[3] Per capita income during the same timeframe averaged $66,306, reflecting concentrations of high-earning professionals in technology and engineering sectors.[59] The poverty rate was 5.6% in recent estimates, lower than the California state average of 12.2% and indicative of broad economic stability amid regional affluence.[60] Unemployment hovered at 4.4% in 2023, below the U.S. average of 4.5% and tied to robust local job markets in semiconductors and software.[61] Housing reflects high demand driven by proximity to Silicon Valley employment hubs. The owner-occupied housing unit rate was 59.3% as of 2019–2023, with median home values exceeding $1.2 million per Census benchmarks, though recent market data shows median sale prices reaching $1.4 million in mid-2024, up 7.5% year-over-year.[3][62] Median listing prices stood at approximately $1.3 million, with per-square-foot values around $795, underscoring affordability constraints for lower-income households despite elevated incomes.[63] Socioeconomic indicators point to an educated workforce supporting these metrics. Educational attainment for residents aged 25 and older features bachelor's degrees or higher at rates comparable to the San Jose metro area, exceeding California's 37.5% baseline and aligning with tech-driven prosperity.[60] This profile correlates with lower poverty and unemployment, though housing costs exert pressure on entry-level workers, contributing to longer commutes and multigenerational households.[64]Government and politics

Municipal structure and administration

Milpitas is a general law city incorporated on January 26, 1954, operating under a council-manager form of government.[65][37] The elected city council sets policy direction, while the appointed city manager handles day-to-day administration and implements council decisions.[66][67] The city council comprises five members: a mayor and four councilmembers, all elected at-large in nonpartisan elections.[68] The mayor serves a two-year term, while councilmembers serve four-year terms, with elections staggered to ensure continuity.[69] Council meetings occur on the first and third Tuesdays of each month at 7:00 p.m.[70] The mayor presides over meetings, represents the city in official capacities, and votes on all matters, but lacks veto power under the council-manager structure.[71] The city manager, appointed by and reporting to the council, oversees approximately 339 full-time equivalent positions across departments including police, fire, public works, community development, and finance.[37][72] This executive role emphasizes efficient service delivery, budget management, and policy execution without direct electoral accountability.[73] Administrative operations are guided by the city code, which establishes the manager's authority pursuant to California Government Code provisions.[71]Electoral outcomes and voter behavior

In Santa Clara County, which encompasses Milpitas, voter registration as of October 2023 showed 48.5% affiliation with the Democratic Party, 12.1% with the Republican Party, 25.2% no party preference, and the remainder with minor parties or other designations, reflecting a substantial Democratic plurality consistent with broader Silicon Valley demographics of high education and income levels that correlate with left-leaning voting patterns.[74] This registration imbalance influences outcomes in partisan races, where Milpitas precincts mirror county-wide results due to homogeneous suburban voter composition. Voter turnout in presidential general elections typically exceeds 70% county-wide, driven by mail-in voting prevalence and civic engagement among professional residents, though local nonpartisan contests see comparatively lower participation in off-cycle years.[75] Municipal elections in Milpitas are nonpartisan, with voters electing a mayor and five city council members at-large to four-year terms, often concurrent with statewide generals to boost turnout. In the November 2024 election, incumbent Mayor Carmen Montano secured re-election with 47.2% of the vote against challengers including Councilmember Hon Lien (44.3%), amid a total of approximately 17,500 ballots cast in Milpitas precincts, benefiting from alignment with county-wide turnout around 75%.[76] City council races that year filled two seats, with incumbents Vice Mayor Evelyn Chua and Councilmember Raul Peralez advancing based on vote shares exceeding 20% each in a field of five candidates, indicating preference for experienced local governance focused on development and public safety rather than ideological divides.[76] In partisan contests, Milpitas voters have consistently favored Democratic candidates, as evidenced by 2020 presidential results where Joseph R. Biden garnered 72.64% county-wide against Donald J. Trump's 25.68%, with precinct data from Milpitas aligning within 2-3 percentage points of this margin due to minimal intra-county variation in affluent tech-adjacent areas.[77] The 2024 presidential election followed suit, with Kamala Harris receiving over 70% in Santa Clara County preliminary tallies, underscoring behavioral patterns where economic stability and pro-immigration stances among the city's large Asian-American population reinforce Democratic support, though occasional competitive local races highlight pragmatic voting over strict partisanship.[76] Statewide races, such as gubernatorial elections, show similar lopsides, with Democratic margins exceeding 60% in recent cycles.Relations with state, federal, and local entities

Milpitas maintains cooperative relations with the California state government primarily through compliance with housing mandates and participation in state-funded initiatives. The city's 6th Cycle Housing Element (2023-2031), adopted on January 24, 2023, was certified compliant by the California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) on May 17, 2023, making Milpitas the first municipality in Santa Clara County to achieve state approval under revised housing laws requiring plans for 3,793 units, including significant affordable housing allocations.[78][79] This certification followed updates to zoning and fee adjustments for affordable projects, reflecting ongoing adaptation to state legislation on housing production and tenant protections.[34] State involvement also extends to affordable housing developments, such as the November 2024 opening of Sango Court, supported by HCD resources for revitalizing industrial sites into low-income units.[80] At the federal level, Milpitas benefits from grants supporting infrastructure and economic programs. In September 2025, the city received a $2.77 million federal grant to expand its SMART rideshare service, increasing vehicle operations by 50% and incorporating autonomous vehicles for enhanced mobility.[81] Similarly, $2.9 million in federal funding was allocated in September 2024 for Safe Routes to School improvements, focusing on pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure upgrades.[82] The Milpitas Unified School District accesses federal aid through programs like the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) and Titles I-IV for educational support, while the city administers microenterprise grants, including $50,000 in federal funds via partnerships for small business recovery.[83][84] Relations with local entities, including Santa Clara County and neighboring cities, involve both collaboration and disputes over shared resources. Milpitas interacts with the county on spheres of influence, encompassing social and economic communities of interest, such as joint service areas and unincorporated lands adjacent to city boundaries.[85] Tensions with San Jose have arisen over environmental impacts; in September 2017, Milpitas authorized litigation against the San Jose-Santa Clara Regional Wastewater Facility after unresolved complaints about odors and noise affecting residents, following years of negotiation attempts.[86] In December 2022, Milpitas joined Santa Clara County and Santa Clara in suing San Jose to block aspects of its North San Jose development plan, citing inadequate environmental reviews, before a settlement enabled additional housing.[87] Cross-jurisdictional issues persist with Fremont and San Jose regarding homeless encampments along Alviso-Milpitas Road, where sweeps in April 2025 displaced individuals without coordinated relocation, highlighting strains in regional homelessness management.[88][89]Economy

Historical and current economic drivers

Milpitas' early economy centered on agriculture, as part of Santa Clara Valley's extensive fruit orchards before the mid-20th century tech transformation.[12] The opening of Ford Motor Company's San Jose Assembly Plant in 1955 on a 160-acre site introduced large-scale manufacturing, employing thousands and shifting the area from rural farming to industrial production, which spurred population growth and infrastructure development.[13] [90] [91] The facility produced vehicles until its closure in 1983, leading to temporary job losses, but its adaptive reuse as the Great Mall of the Bay Area in 1994 created retail opportunities and stabilized local commerce.[13] The late 1950s semiconductor boom positioned Milpitas as a key Silicon Valley node, attracting firms like Fairchild Semiconductor and subsequent spin-offs focused on chip fabrication and design.[16] By the 1960s, companies such as Intersil—established in 1967 for integrated circuits—anchored electronics manufacturing, driving sustained expansion through the 1970s and 1990s as demand for semiconductors propelled job creation in assembly, testing, and R&D.[16] This period saw Milpitas evolve into a manufacturing hub with over 550 plants and eight industrial parks by the late 20th century, capitalizing on proximity to San Jose and skilled labor inflows.[70] Contemporary economic drivers emphasize advanced manufacturing and technology, with manufacturing comprising more than one-fifth of the workforce—double the Bay Area average—and supporting over 41,000 high-tech and professional roles amid a daytime population of about 118,000.[4] In 2023, manufacturing employed 9,791 residents, followed closely by professional, scientific, and technical services at 9,524 jobs, underscoring reliance on semiconductor equipment, data storage, and photonics innovation.[1] Major contributors include Flex for electronics assembly, KLA Corporation for process control tools, Western Digital and Micron Technology for memory solutions, and Lumentum for optical components, fostering a business environment geared toward R&D and supply chain integration in global tech ecosystems.[4]Major employers and industries

![Flex building, 847 Gibraltar Dr., Milpitas, CA][float-right] Milpitas serves as a hub for advanced manufacturing and technology within Silicon Valley, with its economy heavily reliant on high-tech industries such as semiconductors, photonics, data storage, and electronics assembly. The city's strategic location facilitates research and development (R&D) operations, attracting firms focused on innovation in these sectors. Over one-fifth of the local workforce is engaged in manufacturing, while approximately 41,000 residents are employed in high-tech and professional services roles.[4][92] Prominent employers include KLA Corporation, a leader in process control and yield management for semiconductor manufacturing; Flex, which specializes in design, engineering, and supply chain solutions; Lumentum Holdings, focused on optical and photonic products; Western Digital, involved in data storage technologies; and Micron Technology, a producer of memory and storage solutions. These companies maintain significant facilities in Milpitas, supporting thousands of jobs in engineering, production, and technical support. Cisco Systems also operates a major campus here, contributing to networking and communications hardware development.[4][93] In addition to technology, retail plays a role through the Great Mall of the Bay Area, one of the largest enclosed malls in Northern California, employing workers in sales, logistics, and customer service. Healthcare providers like VITAS Healthcare represent a smaller but present sector. The concentration of these industries underscores Milpitas' integration into the broader Bay Area tech ecosystem, though employment data reflects resident occupational distributions rather than city-specific payrolls due to commuting patterns.[92][94]Fiscal policies and business environment