Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Moroccan Arabic

View on WikipediaThis article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (June 2017) |

| Moroccan Arabic | |

|---|---|

| Darija | |

| العربية المغربية الدارجة | |

| Pronunciation | [ddɛɾiʒə] |

| Native to | Morocco |

| Ethnicity | Moroccan Arabs, also used as a second language by other ethnic groups in Morocco |

| Speakers | L1: 31 million (2020)[1] L2: 9.6 million (2020)[1] Total: 40 million (2020)[1] |

| Dialects | |

| Arabic alphabet | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | ary – Moroccan Arabic |

| Glottolog | moro1292 |

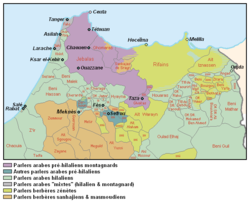

Map of Moroccan Arabic[2] | |

Moroccan Arabic (Arabic: العربية المغربية الدارجة, romanized: al-ʻArabiyyah al-Maghribiyyah ad-Dārija[3] lit. 'Moroccan vernacular Arabic'), also known as Darija (الدارجة or الداريجة[3]), is the dialectal, vernacular form or forms of Arabic spoken in Morocco.[4][5] It is part of the Maghrebi Arabic dialect continuum and as such is mutually intelligible to some extent with Algerian Arabic and to a lesser extent with Tunisian Arabic. It is spoken by 91.9% of the population of Morocco, with 80.6% of Moroccans considering it their native language.[6]

While Modern Standard Arabic is used to varying degrees in formal situations such as religious sermons, books, newspapers, government communications, news broadcasts and political talk shows, Moroccan Arabic is the predominant spoken language of the country and has a strong presence in Moroccan television entertainment, cinema and commercial advertising. Moroccan Arabic has many regional dialects and accents as well, with its mainstream dialect being the one used in metropolitan cities, such as Casablanca, Rabat, Meknes and Fez. Therefore, the metropolitan dialects dominate the media and eclipse most of the other regional accents.

Dialects

[edit]Moroccan Arabic was formed by two dialects of Arabic belonging to two genetically different groups: pre-Hilalian and Hilalian dialects.[7][8][9]

There is a growing consensus that modern Moroccan Arabic is undergoing a process of koineization.[10] This koine emerged in the past fifty years due to urbanization, increased mobility and the influence of radio and television and is based of the Bedouin dialects of the Atlantic coast.[11] This new dialect is the one that is socially dominant and is used in popular singing, in theatre and cinema, in radio and TV announcements and most notably in publicity marketing. In the literature, this dialect has been named Average Moroccan Arabic, General Moroccan Arabic and Mainstream Moroccan Arabic but Moroccans only refer to it as Darija.[12]

The growth of Mainstream Moroccan Arabic has affected the speaker count of several local dialects, especially Hilalian dialects

Pre-Hilalian dialects

[edit]

Pre-Hilalian dialects are a result of early Arabization phases of the Maghreb, from the 7th to the 12th centuries, concerning the main urban settlements, the harbors, the religious centres (zaouias) as well as the main trade routes. The dialects are generally classified in three types: (old) urban, "village" and "mountain" sedentary and Jewish dialects.[8][13] In Morocco, several pre-Hilalian dialects are spoken:

- Urban dialects: Old dialects of Fes, Casablanca, Rabat, Salé, Taza, Tétouan, Wezzan, Chefchaouen, Tangier, Asilah, Larache, Ksar el-Kebir, Meknes and Marrakesh.[14][9][15]

- Jebli dialects: Dialects of northwestern Morocco, spoken by the Jebala people.[9][16]

- Sedentary ("village") dialects of Zerhoun and Sefrou and their neighboring tribes (Zerahna tribe for Zerhoun; Kechtala, Behalil and Yazgha tribes for Sefrou), remnants of pre-Hilalian dialects that were more widely spoken before the 12th century.

- Judeo-Moroccan, nearly extinct, formerly spoken by Moroccan Jews.[17]

The pre-Hilalian dialects are descended from Arabic dialects brought to the region by Qurashi families, such as the Idrissids and the Umayyads, as well as dialects brought by Arabs and Amazighs from al-Andalus. When al-Andalus fell, many of its Muslim inhabitants migrated back to North Africa, particularly to cities along the Mediterranean coast.

Hilalian dialects

[edit]Hilalian dialects (Bedouin dialects) were introduced following the migration of Arab nomadic tribes to Morocco in the 11th century, particularly the Banu Hilal, which the Hilalian dialects are named after.[18][13]

The Hilalian dialects spoken in Morocco belong to the Maqil subgroup,[13] a family that includes three main dialectal areas:

- 'Aroubi Arabic (Western Moroccan Arabic): spoken in the western plains of Morocco by Doukkala, Abda, Tadla, Chaouia, Gharb, and Zaers, and in the area north of Fes by Hyayna, Cheraga, Awlad Jama', etc.

- Eastern Moroccan Arabic: spoken in Oujda, the Oriental region[19])

- New urban dialects: predominantly Hilalian urban dialects, resulting from the migration movements from the countryside to cities in 20th century.[15]

- Hassaniya Arabic: spoken in southern Morocco, Western Sahara and Mauritania.[20] Among the dialects, Hassaniya is often considered as distinct from Moroccan Arabic.

The Hilalian dialects are descended from Arabic dialects brought to the region by Hilalian tribes, such as the Athbaj and Riyah. Although the Hilalians did interact and intermarry with the local Amazigh populations, it occurred to a much lesser extent compared to the Qurashi families. Since the Hilalians came to the region in large numbers, alongside their women and children, unlike the Qurashis, who were typically descended from a single Qurashi male who had migrated to the region alone.

Phonology

[edit]Vowels

[edit]| Short | Long | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front | Central | Back | Front | Back | |

| Close | ə | u | iː | uː | |

| Mid | |||||

| Open | aː | ||||

One of the most notable features of Moroccan Arabic is the collapse of short vowels. Initially, short /a/ and /i/ were merged into a phoneme /ə/ (however, some speakers maintain a difference between /a/ and /ə/ when adjacent to pharyngeal /ʕ/ and /ħ/). This phoneme (/ə/) was then deleted entirely in most positions; for the most part, it is maintained only in the position /...CəC#/ or /...CəCC#/ (where C represents any consonant and # indicates a word boundary), i.e. when appearing as the last vowel of a word. When /ə/ is not deleted, it is pronounced as a very short vowel, tending towards [ɑ] in the vicinity of emphatic consonants, [a] in the vicinity of pharyngeal /ʕ/ and /ħ/ (for speakers who have merged /a/ and /ə/ in this environment), and [ə] elsewhere. Original short /u/ usually merges with /ə/ except in the vicinity of a labial or velar consonant. In positions where /ə/ was deleted, /u/ was also deleted, and is maintained only as labialization of the adjacent labial or velar consonant; where /ə/ is maintained, /u/ surfaces as [ʊ]. This deletion of short vowels can result in long strings of consonants (a feature shared with Amazigh and certainly derived from it). These clusters are never simplified; instead, consonants occurring between other consonants tend to syllabify, according to a sonorance hierarchy. Similarly, and unlike most other Arabic dialects, doubled consonants are never simplified to a single consonant, even when at the end of a word or preceding another consonant.

Some dialects are more conservative in their treatment of short vowels. For example, some dialects allow /u/ in more positions. Dialects of the Sahara, and eastern dialects near the border of Algeria, preserve a distinction between /a/ and /i/ and allow /a/ to appear at the beginning of a word, e.g. /aqsˤarˤ/ "shorter" (standard /qsˤərˤ/), /atˤlaʕ/ "go up!" (standard /tˤlaʕ/ or /tˤləʕ/), /asˤħaːb/ "friends" (standard /sˤħab/).

Long /aː/, /iː/ and /uː/ are maintained as semi-long vowels, which are substituted for both short and long vowels in most borrowings from Modern Standard Arabic (MSA). Long /aː/, /iː/ and /uː/ also have many more allophones than in most other dialects; in particular, /aː/, /iː/, /uː/ appear as [ɑ], [e], [o] in the vicinity of emphatic consonants and [q], [χ], [ʁ], [r], but [æ], [i], [u] elsewhere. (Most other Arabic dialects only have a similar variation for the phoneme /aː/.) In some dialects, such as that of Marrakech, front-rounded and other allophones also exist. Allophones in vowels usually do not exist in loanwords.

Emphatic spreading (i.e. the extent to which emphatic consonants affect nearby vowels) occurs much less than in Egyptian Arabic. Emphasis spreads fairly rigorously towards the beginning of a word and into prefixes, but much less so towards the end of a word. Emphasis spreads consistently from a consonant to a directly following vowel, and less strongly when separated by an intervening consonant, but generally does not spread rightwards past a full vowel. For example, /bidˤ-at/ [bedɑt͡s] "eggs" (/i/ and /a/ both affected), /tˤʃaʃ-at/ [tʃɑʃæt͡s] "sparks" (rightmost /a/ not affected), /dˤrˤʒ-at/ [drˤʒæt͡s] "stairs" (/a/ usually not affected), /dˤrb-at-u/ [drˤbat͡su] "she hit him" (with [a] variable but tending to be in between [ɑ] and [æ]; no effect on /u/), /tˤalib/ [tɑlib] "student" (/a/ affected but not /i/). Contrast, for example, Egyptian Arabic, where emphasis tends to spread forward and backward to both ends of a word, even through several syllables.

Emphasis is audible mostly through its effects on neighboring vowels or syllabic consonants, and through the differing pronunciation of /t/ [t͡s] and /tˤ/ [t]. Actual pharyngealization of "emphatic" consonants is weak and may be absent entirely. In contrast with some dialects, vowels adjacent to emphatic consonants are pure; there is no diphthong-like transition between emphatic consonants and adjacent front vowels.

Consonants

[edit]| Labial | Dental-Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Pharyngeal | Glottal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | emphatic | plain | emphatic | |||||||

| Nasal | m | mˤ | n | |||||||

| Plosive | voiceless | (p) | t | tˤ | k | q | ʔ | |||

| voiced | b | bˤ | d | dˤ | ɡ | |||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | (fˤ) | s | sˤ | ʃ | χ | ħ | h | |

| voiced | (v) | z | zˤ | ʒ | ʁ | ʕ | ||||

| Tap | ɾ | ɾˤ | ||||||||

| Trill | r | rˤ | ||||||||

| Approximant | l | lˤ | j | w | ||||||

Phonetic notes:

- Non-emphatic /t/ In normal circumstances, is pronounced with noticeable affrication, almost like [t͡s] (still distinguished from a sequence of /t/ + /s/), and hence is easily distinguishable from emphatic /tˤ/ which can be pronounced as [t]. However, in some recent loanwords from European languages, a non-affricated, non-emphatic [t] appears, distinguished from emphatic /tˤ/ primarily by its lack of effect on adjacent vowels (see above; an alternative analysis is possible).

- /mˤʷ, bˤʷ, fˤʷ/ are very distinct consonants that only occur geminated, and almost always come at the beginning of a word. They function completely differently from other emphatic consonants: They are pronounced with heavy pharyngealization, affect adjacent short/unstable vowels but not full vowels, and are pronounced with a noticeable diphthongal off-glide between one of these consonants and a following front vowel. Most of their occurrences can be analyzed as underlying sequences of /mw/, /fw/, /bw/ (which appear frequently in diminutives, for example). However, a few lexical items appear to have independent occurrences of these phonemes, e.g. /mˤmˤʷ-/ "mother" (with attached possessive, e.g. /mˤmˤʷək/ "your mother").

- /p/ and /v/ occur mostly in recent borrowings from European languages, and may be assimilated to /b/ or /f/ in some speakers.

- Unlike in most other Arabic dialects (but, again, similar to Amazigh), non-emphatic /r/ and emphatic /rˤ/ are two entirely separate phonemes, almost never contrasting in related forms of a word.

- /lˤ/ is rare in native words; in nearly all cases of native words with vowels indicating the presence of a nearby emphatic consonant, there is a nearby triggering /tˤ/, /dˤ/, /sˤ/, /zˤ/ or /rˤ/. Many recent European borrowings appear to require (lˤ) or some other unusual emphatic consonant in order to account for the proper vowel allophones; but an alternative analysis is possible for these words where the vowel allophones are considered to be (marginal) phonemes on their own.

- Original /q/ splits lexically into /q/ and /ɡ/ in many dialects (such as in Casablanca) but /q/ is preserved all the time in most big cities such as Rabat, Fes, Marrakech, etc. and all of northern Morocco (Tangier, Tetouan, Chefchaouen, etc.); for all words, both alternatives exist.

- Original /dʒ/ normally appears as /ʒ/, but as /ɡ/ (sometimes /d/) if a sibilant, lateral or rhotic consonant appears later in the same stem: /ɡləs/ "he sat" (MSA /dʒalas/), /ɡzzar/ "butcher" (MSA /dʒazzaːr/), /duz/ "go past" (MSA /dʒuːz/) like in western Algerian dialects.

- Original /s/ is converted to /ʃ/ if /ʃ/ occurs elsewhere in the same stem, and /z/ is similarly converted to /ʒ/ as a result of a following /ʒ/: /ʃəmʃ/ "sun" vs. MSA /ʃams/, /ʒuʒ/ "two" vs. MSA /zawdʒ/ "pair", /ʒaʒ/ "glass" vs. MSA /zudʒaːdʒ/, etc. This does not apply to recent borrowings from MSA (e.g. /mzaʒ/ "disposition"), nor as a result of the negative suffix /ʃ/ or /ʃi/.

- The gemination of the flap /ɾ/ results in a trill /r/.

Writing

[edit]

Through most of its history, Moroccan vernacular Arabic has usually not been written.[22]: 59 Due to the diglossic nature of the Arabic language, most literate Muslims in Morocco would write in Standard Arabic, even if they spoke Darija as a first language.[22]: 59 However, since Standard Arabic was typically taught in Islamic religious contexts, Moroccan Jews usually would not learn Standard Arabic and would write instead in Darija, or more specifically a variety known as Judeo-Moroccan Arabic, using Hebrew script.[22]: 59 A risala on Semitic languages written in Maghrebi Judeo-Arabic by Judah ibn Quraish to the Jews of Fes dates back to the ninth-century.[22]: 59

Al-Kafif az-Zarhuni's epic 14th century zajal Mala'bat al-Kafif az-Zarhuni, about Abu al-Hasan Ali ibn Othman al-Marini's campaign on Hafsid Ifriqiya, is considered the first literary work in Darija.[23][24]

Most books and magazines are in Modern Standard Arabic; Qur'an books are written and read in Classical Arabic, and there is no universally standard written system for Darija. There is also a loosely standardized Latin system used for writing Moroccan Arabic in electronic media, such as texting and chat, often based on sound-letter correspondences from French, English or Spanish ('sh' or 'ch' for English 'sh', 'u' or 'ou' for English 'oo', etc.) and using numbers to represent sounds not found in French or English (2-3-7-9 used for ق-ح-ع-ء, respectively.).

In the last few years, there have been some publications in Moroccan Darija, such as Hicham Nostik's Notes of a Moroccan Infidel, as well as basic science books by Moroccan physics professor Farouk El Merrakchi.[25] Newspapers in Moroccan Arabic also exist, such as Souq Al Akhbar, Al Usbuu Ad-Daahik,[26] the regional newspaper Al Amal (formerly published by Latifa Akherbach), and Khbar Bladna (news of our country), which was published by Tangier-based American painter Elena Prentice between 2002 and 2006.[27]

The latter also published books written in Moroccan Arabic, mostly novels and stories, written by authors such as Kenza El Ghali and Youssef Amine Alami.[27]

Vocabulary

[edit]Substrates

[edit]Moroccan Arabic is characterized by a strong Berber, as well as Latin (African Romance), substratum.[28]

Following the Arab conquest, Berber languages remained widely spoken. During their Arabisation, some Berber tribes became bilingual for generations before abandoning their language for Arabic; however, they kept a substantial Berber stratum that increases from the east to the west of the Maghreb, making Moroccan Arabic dialects the ones most influenced by Berber. Arabian tribes that inhabited the plains of Morocco also adopted Amazigh loanwords, though much less compared to the pre-Hilalian dialects spoken by city-dwellers and Amazighs. For the most part, the Hilalian Dialects of the western plains remained mostly unaffected until the beginning of urbanization after the French colonization period.

More recently, the influx of Andalusi people and Spanish-speaking–Moriscos (between the 15th and the 17th centuries) influenced urban dialects with Spanish substrate (and loanwords).

Vocabulary and loanwords

[edit]The vocabulary of Moroccan Arabic is mostly Semitic and derived from Classical Arabic.[29] It also contains some Berber, French and Spanish loanwords.

There are noticeable lexical differences between Moroccan Arabic and most other Arabic languages. Some words are essentially unique to Moroccan Arabic: daba "now". Many others, however, are characteristic of Maghrebi Arabic as a whole including both innovations and unusual retentions of Classical vocabulary that disappeared elsewhere, such as hbeṭ' "go down" from Classical habaṭ. Others are shared with Algerian Arabic such as hḍeṛ "talk", from Classical hadhar "babble", and temma "there", from Classical thamma.

There are a number of Moroccan Arabic dictionaries in existence:

- A Dictionary of Moroccan Arabic: Moroccan-English, ed. Richard S. Harrell & Harvey Sobelman. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 1963 (reprinted 2004.)

- Mu`jam al-fuṣḥā fil-`āmmiyyah al-maghribiyyah معجم الفصحى في العامية المغربية, Muhammad Hulwi, Rabat: al-Madaris 1988.

- Dictionnaire Colin d'arabe dialectal marocain (Rabat, éditions Al Manahil, ministère des Affaires Culturelles), by a Frenchman named Georges Séraphin Colin, who devoted nearly all his life to it from 1921 to 1977. The dictionary contains 60,000 entries and was published in 1993, after Colin's death.

Examples of words inherited from Classical Arabic

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. The vast majority of 'example words' below lack citations. (June 2023) |

- kəlb: dog (orig. kalb كلب)

- qəṭ: cat (orig. qiṭṭ قط)

- qərd: monkey (orig. qird قرد)

- bħar: sea (orig. baħr بحر)

- šəmš: sun (orig. šams شمس)

- bab: door (orig. bab باب)

- ħiṭ: wall (orig. ħā'iṭ حائط)

- bagra/baqra: cow (orig. baqarah بقرة)

- koul: eat (orig. akala أكل)

- fikra: idea (orig. fikrah فكرة)

- ħub: love (orig. ħubb حب)

- dhab: gold (orig. dhahab ذهب)

- ħdid: metal (orig. ħadid حديد)

- ržəl: foot (orig. rijl رجل)

- ras: head (orig. ra's رأس)

- wžəh: face (orig. wažh وجه)

- bit: room (orig. bayt بيت)

- xiṭ: wire (orig. khayṭ خيط)

- bənti: my daughter (orig. ibnati ابنتي)

- wəldi: my son (orig. waladi ولدي)

- rajəl: man (orig. rajul رجل)

- mra: woman (orig. imra'ah امرأة)

- colors=red/green/blue/yellow: ħmər/xdər/zrəq/ṣfər (orig. aħmar/axdar/azraq/aṣfar أحمر/أخضر/أزرق/أصفر)

- šħal: how much (orig. ayyu šayʾ ḥāl أَيُّ شَيْء حَال)[citation needed]

- ʕlāš: why (orig. ʿalā ʾayyi šayʾ, عَلَى أَيِّ شَيْء)[citation needed]

- fīn: where (orig. ʿfī ʾaynaʾ فِي أَيْنَ)

- ʢṭīni: give me (orig. aʢṭinī أعطني)

Examples of words inherited from Tamazight

[edit]- Muš: cat (orig. Amouch), pronounced [muʃ]

- Xizzu: carrots [xizzu]

- Tekšita: typical Moroccan dress

- Lalla: lady, madam

- Mesus: tasteless

- Tburiš: goosebumps

- Fazeg: wet

- Zezon: deaf

- Henna: grandmother (jebli and northern urban dialects) / "jeda" :southern dialect

- Dšar or tšar: zone, region [tʃɑɾ]

- Neggafa: wedding facilitator (orig. tamneggaft) [nɪɡɡafa][30]

- Mezlot: poor

- Sebniya: veil (jebli and northern urban dialects)

- žaada: carrots (jebli and northern urban dialects)

- sarred: synonym of send (jebli and northern urban dialects)

- šlaɣem: mustache

- Awriz: heel (jebli and northern urban dialects)

- Sifet: send

- Sarut: key

- Baxuš: insect

- Kermos: figs

- Zgel: miss, overlook

- Tabrori: hail

- Fakron: turtle

- Tammara: hardship, worries

- Bra: letter

- Deġya: hurry

- Dmir: hard work

Examples of loanwords from French

[edit]- forshita/forsheta: fourchette (fork), pronounced [foɾʃitˤɑ]

- tonobil/tomobil: automobile (car) [tˤonobil]

- telfaza: télévision (television) [tlfazɑ]

- radio: radio [ɾɑdˤjo], rādio is common across most varieties of Arabic

- bartma: appartement (apartment) [bɑɾtˤmɑ]

- rompa: rondpoint (roundabout) [ɾambwa]

- tobis: autobus (bus) [tˤobis]

- kamera: caméra (camera) [kɑmeɾɑ]

- portable: portable (cell phone) [poɾtˤɑbl]

- tilifūn: téléphone (telephone) [tilifuːn]

- brika: briquet (lighter) [bɾike]

- parisiana: a French baguette, more common is komera, from spanish

- disk: song

- tran: train (train) [træːn]

- serbita: serviette (napkin) [srbitɑ]

- tabla : table (table) [tɑblɑ]

- ordinatūr/pc: ordinateur / pc

- boulis: police

Examples of loanwords from Spanish

[edit]Some loans might have come through Andalusi Arabic brought by Moriscos when they were expelled from Spain following the Christian Reconquest or, alternatively, they date from the time of the Spanish protectorate in Morocco.

- rwida: rueda (wheel), pronounced [ɾwedˤɑ]

- kuzina: cocina (kitchen) [kuzinɑ]

- simana: semana (week) [simɑnɑ], may be borrowed from the french word for week (semaine)

- manta: manta (blanket) [mɑntˤɑ]

- rial: real (five centimes; the term has also been borrowed into many other Arabic dialects) [ɾjæl]

- fundo: fondo (bottom of the sea or the swimming pool) [fundˤo]

- karrossa: carrosa (carriage) [kɑrosɑ]

- kama (in the north only): cama (bed) [kɑmˤɑ]

- blassa: plaza (place) [blɑsɑ]

- komir: comer (but Moroccans use the expression to name the Parisian bread) [komeɾ]

- elmaryo: El armario (the cupboard) [elmɑɾjo]

- karratera: carretera (road) [karateɾa]

Examples of regional differences

[edit]- Now: "daba" in the majority of regions, but "druk" or "druka" is also used in some regions in the centre and south and "drwek" or "durk" in the east.

- When?: "fuqāš" in most regions,"fuyāx" in the Northwest (Tangier-Tetouan) but "imta" in the Atlantic region and "weqtāš" in Rabat region.

- What?: "ašnu", "šnu" or "āš" in most regions, but "šenni", "šennu" in the north, "šnu", "š" in Fes, and "wašta", "wasmu", "wāš" in the far east.

Some useful sentences

[edit]Note: All sentences are written according to the transcription used in Richard Harrell, A Short Reference Grammar of Moroccan Arabic (Examples with their pronunciation).:[31]

- a i u = full vowels = normally [æ i u], but [ɑ e o] in the vicinity of an emphatic consonant or q ("vicinity" generally means not separated by a full vowel)

- e = /ə/

- q = /q/

- x ġ = /x ɣ/

- y = /j/

- t = [tˢ]

- š ž = /ʃ ʒ/

- ḥ ʿ = /ħ ʕ/

- ḍ ḷ ṛ ṣ ṭ ẓ = emphatic consonants = /dˤ lˤ rˤ sˤ tˤ zˤ/ (ṭ is not affricated, unlike t)

| English | Western Moroccan Arabic | Northern (Jebli, Tanjawi and Tetouani) Moroccan Arabic | Eastern (Oujda) Moroccan Arabic | Western Moroccan Arabic

(Transliterated) |

Northern (Jebli, Tetouani) Moroccan Arabic

(Transliterated) |

Eastern (Oujda) Moroccan Arabic

(Transliterated) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How are you? | لا باس؟ | كيف نتينا؟/لا باس؟ بخير؟ | راك شباب؟ /لا باس؟/ راك غايَ؟ | la bas? | la bas? / bi-xayr?/ kif ntina? / amandra? | la bas? / rak ġaya / rak šbab? |

| Can you help me? | يمكن لك تعاونني؟ | تقدر تعاونني؟/ واخا تعاونني؟ | يمكن لك تعاونني؟ | yemken-lek tʿaweni? | teqder dʿaweni? waxa dʿaweni? | yemken-lek tʿaweni? |

| Do you speak English? | واش كَتهدر بالانّڭليزية؟/ واش كتدوي بالانّڭليزية؟ | واش كَتهدر بالانّڭليزية؟/كتهدر الانّڭليزية؟ | واش تهدر الانّڭليزية؟ | waš ka-tehder lengliziya / waš ka-tedwi be-l-lengliziya? | waš ka-tehder be-l-lengliziya? / ka-tehder lengliziya? | waš tehder lengliziya? |

| Excuse me | سمح ليَ | سمح لي | سمح لِيَ | smaḥ-liya | smaḥ-li | smaḥ-liya |

| Good luck | الله يعاون/الله يسهل | allah y'awn / allah ysahel | ||||

| Good morning | صباح الخير/صباح النور | ṣbaḥ l-xir / ṣbaḥ n-nur | ||||

| Good night | تصبح على خير | الله يمسيك بخير | تصبح على خير | teṣbaḥ ʿla xir | lay ymsik be-xer | teṣbaḥ ʿla xir |

| Goodbye | بالسلامة / تهلا | بالسلامة | بالسلامة | be-slama / tḥălla | be-slama | be-slama |

| Happy new year | سنة سعيدة | sana saʿida | ||||

| Hello | السلام عليكم/اهلاً | السلام عليكم/اهلاً | السلام عليكم | s-salam ʿalikum / as-salamu ʿalaykum (Classical) / ʔahlan | as-salamu ʿalaykum (Classical) / ʔahlan | s-salam ʿlikum |

| How are you doing? | لا باس؟ | la bas (ʿlik)? | ||||

| How are you? | كي داير؟/كي دايرة؟ | كيف نتين؟/كيف نتينا؟ | كي راك؟ | ki dayer ? (masculine) / ki dayra ? (feminine) | kif ntin? (Jebli) / kif ntina [ki tina] ? (Northern urban) | ki rak? |

| Is everything okay? | كل شي مزيان؟ | كل شي مزيان؟ /كل شي هو هداك؟؟ | كل شي مليح؟ | kul-ši mezyan ? | kul-ši mezyan ? / kul-ši huwa hadak ? | kul-ši mliḥ? / kul-ši zin? |

| Nice to meet you | متشرفين | metšaṛṛfin [mət.ʃɑrˤrˤ.fen] | ||||

| No thanks | لا شكراً | la šukran | ||||

| Please | الله يخليك/عفاك | الله يعزك / الله يخليك / عفاك | الله يعزك / الله يخليك | ḷḷa yxallik / ʿafak | ḷḷa yxallik / ḷḷa yʿizek / ʿafak | ḷḷa yxallik / ḷḷa yʿizek |

| Take care | تهلا فراسك | تهلا | تهلا فراسك | tḥălla f-ṛaṣek | tḥălla | tḥălla f-ṛaṣek |

| Thank you very much | شكراً بزاف | šukran bezzaf | ||||

| What do you do? | فاش خدام/شنو كتدير؟ | faš xddam? / chno katdir | škatʿăddel? / šenni xaddam? (masculine) / šenni xaddama? (feminine) / š-ka-dexdem? / šini ka-teʿmel/tʿadal f-hyatak? | faš texdem? (masculine) / faš txedmi ? (feminine) | ||

| What's your name? | شنو اسمك؟ / شنو سميتك؟ | ašnu smiytek? / šu smiytek | šenni ʔesmek? /šenno ʔesmek? / kif-aš msemy nta/ntinah? | wašta smiytek? | ||

| Where are you from? | منين نتا؟ | mnin nta? (masculine) / mnin nti? (feminine) | mnayn ntina? | min ntaya? (masculine) / min ntiya? (feminine) | ||

| Where are you going? | فين غادي؟ | fin ġhadi? | fayn machi? (masculine) / fayn mašya? (feminine) | f-rak temchi? / f-rak rayaḥ | ||

| You are welcome | بلا جميل/مرحبا/دّنيا هانية/ماشي مشكل / العفو | bla žmil/merḥba/ddenya hania/maši muškil/l'afo | bla žmil/merḥba/ddunya hania/maši muškil/l'afo | bla žmil/merḥba/ddenya hania/maši muškil/l'afo | ||

Further useful phrases

[edit]| English[32] | Moroccan Arabic | Latin Transliteration |

|---|---|---|

| Yes. | .ايه | eyeh. |

| Yes please. | .وخا شكراً | wakha shoukran. |

| No. | .لا | la. |

| Thank you. | .شكراً | shoukran. |

| I'd like a coffee please. | .واحد القهوة عفاك | wahed lqahoua afak. |

| What time is it? | شحال فالساعة؟ | ch-hal fssa-a? |

| Can you repeat that please? | وخا تعاود عافاك؟ | wakha t-awoud afak? |

| Please speak more slowly. | .هضر بشويا عافاك | hder bshwiya afak. |

| I don't understand. | .ما فهمتش | ma fhamtch. |

| Sorry. | .سمح لي | smeh li. |

| Where are the toilets? | فين الطواليط؟ | fin toilettes? |

| How much does this cost? | بشحال هادا؟ | bch-hal hada? |

| Welcome! | !تفضّل | tfdel! |

| Good evening. | .مسا الخير | msa lkheir. |

Grammar

[edit]Verbs

[edit]Introduction

[edit]The regular Moroccan Arabic verb conjugates with a series of prefixes and suffixes. The stem of the conjugated verb may change a bit, depending on the conjugation:

The stem of the Moroccan Arabic verb for "to write" is kteb.

Past tense

[edit]The past tense of kteb (write) is as follows:

I wrote: kteb-t

You wrote: kteb-ti (some regions tend to differentiate between masculine and feminine, the masculine form is kteb-t, the feminine kteb-ti)

He/it wrote: kteb (can also be an order to write; kteb er-rissala: Write the letter)

She/it wrote: ketb-et / ketb-at""

We wrote: kteb-na

You (plural) wrote: kteb-tu / kteb-tiu

They wrote: ketb-u

The stem kteb turns into ketb before a vowel suffix because of the process of inversion described above.

Present tense

[edit]The present tense of kteb is as follows:

I am writing: ka-ne-kteb

You are (masculine) writing: ka-te-kteb

You are (feminine) writing: ka-t-ketb-i

He's/it is writing: ka-ye-kteb

She is/it is writing: ka-te-kteb

We are writing: ka-n-ketb-u

You (plural) are writing: ka-t-ketb-u

They are writing: ka-y-ketb-u

The stem kteb turns into ketb before a vowel suffix because of the process of inversion described above. Between the prefix ka-n-, ka-t-, ka-y- and the stem kteb, an e appears but not between the prefix and the transformed stem ketb because of the same restriction that produces inversion.

In the north, "you are writing" is always ka-de-kteb regardless of who is addressed. This is also the case of de in de-kteb as northerners prefer to use de and southerners prefer te. However, there is an exception, which is the northern dialectof Tangier, where they use te instead of de .

Instead of the prefix ka, some speakers prefer the use of ta (ta-ne-kteb "I am writing"). The coexistence of these two prefixes is from historic differences. In general, ka is more used in the north and ta in the south, some other prefixes like la, a, qa are less used. In some regions like in the east (Oujda), most speakers use no preverb (ne-kteb, te-kteb, y-kteb, etc.).

Other tenses

[edit]To form the future tense, the prefix ka-/ta- is removed and replaced with the prefix ġa-, ġad- or ġadi instead (e.g. ġa-ne-kteb "I will write", ġad-ketb-u (north) or ġadi t-ketb-u "You (plural) will write") It is worth noting that in northern Morocco, such as Tangier and Tetouan, they use "ha" instead of ""gha/ġa"" most of the time, and also "ʕa" (عا) to a lesser extent. Also "aa" can be used as an abbreviation for "Gha/Ġa" in the general Moroccan dialect in rapid speech especially.

For the subjunctive and infinitive, the ka- is removed (bġit ne-kteb "I want to write", bġit te-kteb "I want 'you to write").

The imperative is conjugated with the suffixes of the present tense but without any prefixes or preverbs:

kteb Write! (masculine singular)

ketb-i Write! (feminine singular)

ketb-u Write! (plural)

Negation

[edit]One characteristic of Moroccan Arabic syntax, which it shares with other North African varieties as well as some southern Levantine dialect areas, is in the two-part negative verbal circumfix /ma-...-ʃi/. (In many regions, including Marrakech, the final /i/ vowel is not pronounced so it becomes /ma-...-ʃ/.)[33]

- Past: /kteb/ "he wrote" /ma-kteb-ʃi/ "he did not write"

- Present: /ka-j-kteb/ "he writes" /ma-ka-j-kteb-ʃi/ "he does not write"

/ma-/ comes from the Classical Arabic negator /ma/. /-ʃi/ is a development of Classical /ʃajʔ/ "thing". The development of a circumfix is similar to the French circumfix ne ... pas in which ne comes from Latin non "not" and pas comes from Latin passus "step". (Originally, pas would have been used specifically with motion verbs, as in "I did not walk a step". It was generalised to other verbs.)

The negative circumfix surrounds the entire verbal composite, including direct and indirect object pronouns:

- /ma-kteb-hom-li-ʃi/ "he did not write them to me"

- /ma-ka-j-kteb-hom-li-ʃi/ "he does not write them to me"

- /ma-ɣadi-j-kteb-hom-li-ʃi/ "he will not write them to me"

- /waʃ ma-kteb-hom-li-ʃi/ "did he not write them to me?"

- /waʃ ma-ka-j-kteb-hom-li-ʃi/ "does he not write them to me?"

- /waʃ ma-ɣadi-j-kteb-hom-li-ʃi/ "will he not write them to me?"

Future and interrogative sentences use the same /ma-...-ʃi/ circumfix (unlike, for example, in Egyptian Arabic). Also, unlike in Egyptian Arabic, there are no phonological changes to the verbal cluster as a result of adding the circumfix. In Egyptian Arabic, adding the circumfix can trigger stress shifting, vowel lengthening and shortening, elision when /ma-/ comes into contact with a vowel, addition or deletion of a short vowel, etc. However, they do not occur in Moroccan Arabic (MA):

- There is no phonological stress in MA.

- There is no distinction between long and short vowels in MA.

- There are no restrictions on complex consonant clusters in MA and hence no need to insert vowels to break up such clusters.

- There are no verbal clusters that begin with a vowel. The short vowels in the beginning of Forms IIa(V), and such, have already been deleted. MA has first-person singular non-past /ne-/ in place of Egyptian /a-/.

Negative pronouns such as walu "nothing", ḥta ḥaja "nothing" and ḥta waḥed "nobody" can be added to the sentence without ši as a suffix:

- ma-ġa-ne-kteb walu "I will not write anything"

- ma-te-kteb ḥta ḥaja "Do not write anything"

- ḥta waḥed ma-ġa-ye-kteb "Nobody will write"

- wellah ma-ne-kteb or wellah ma-ġa-ne-kteb "I swear to God I will not write"

Note that wellah ma-ne-kteb could be a response to a command to write kteb while wellah ma-ġa-ne-kteb could be an answer to a question like waš ġa-te-kteb? "Are you going to write?"

In the north, "'you are writing" is always ka-de-kteb regardless of who is addressed. It is also the case of de in de-kteb, as northerners prefer to use de (Tangier is an exception) and southerners prefer te.

Instead of the prefix ka, some speakers prefer the use of ta (ta-ne-kteb "I am writing"). The co-existence of these two prefixes is from historical differences. In general ka is more used in the north and ta in the south. In some regions like the east (Oujda), most speakers use no preverb:

- ka ma-ġadi-ši-te-kteb?!

In detail

[edit]Verbs in Moroccan Arabic are based on a consonantal root composed of three or four consonants. The set of consonants communicates the basic meaning of a verb. Changes to the vowels between the consonants, along with prefixes and/or suffixes, specify grammatical functions such as tense, person and number in addition to changes in the meaning of the verb that embody grammatical concepts such as causative, intensive, passive or reflexive.

Each particular lexical verb is specified by two stems, one used for the past tense and one used for non-past tenses, along with subjunctive and imperative moods. To the former stem, suffixes are added to mark the verb for person, number and gender. To the latter stem, a combination of prefixes and suffixes are added. (Very approximately, the prefixes specify the person and the suffixes indicate number and gender.) The third person masculine singular past tense form serves as the "dictionary form" used to identify a verb like the infinitive in English. (Arabic has no infinitive.) For example, the verb meaning "write" is often specified as kteb, which actually means "he wrote". In the paradigms below, a verb will be specified as kteb/ykteb (kteb means "he wrote" and ykteb means "he writes"), indicating the past stem (kteb-) and the non-past stem (also -kteb-, obtained by removing the prefix y-).

The verb classes in Moroccan Arabic are formed along two axes. The first or derivational axis (described as "form I", "form II", etc.) is used to specify grammatical concepts such as causative, intensive, passive or reflexive and mostly involves varying the consonants of a stem form. For example, from the root K-T-B "write" are derived form I kteb/ykteb "write", form II ketteb/yketteb "cause to write", form III kateb/ykateb "correspond with (someone)" etc. The second or weakness axis (described as "strong", "weak", "hollow", "doubled" or "assimilated") is determined by the specific consonants making up the root, especially whether a particular consonant is a "w" or " y", and mostly involves varying the nature and location of the vowels of a stem form. For example, so-called weak verbs have one of those two letters as the last root consonant, which is reflected in the stem as a final vowel instead of a final consonant (ṛma/yṛmi "throw" from Ṛ-M-Y). Meanwhile, hollow verbs are usually caused by one of those two letters as the middle root consonant, and the stems of such verbs have a full vowel (/a/, /i/ or /u/) before the final consonant, often along with only two consonants (žab/yžib "bring" from Ž-Y-B).

It is important to distinguish between strong, weak, etc. stems and strong, weak, etc. roots. For example, X-W-F is a hollow root, but the corresponding form II stem xuwwef/yxuwwef "frighten" is a strong stem:

- Weak roots are those that have a w or a y as the last consonant. Weak stems are those that have a vowel as the last segment of the stem. For the most part, there is a one-to-one correspondence between weak roots and weak stems. However, form IX verbs with a weak root will show up the same way as other root types (with doubled stems in most other dialects but with hollow stems in Moroccan Arabic).

- Hollow roots are triliteral roots that have a w or a y as the last consonant. Hollow stems are those that end with /-VC/ in which V is a long vowel (most other dialects) or full vowel in Moroccan Arabic (/a/, /i/ or /u/). Only triliteral hollow roots form hollow stems and only in forms I, IV, VII, VIII and X. In other cases, a strong stem generally results. In Moroccan Arabic, all form IX verbs yield hollow stems regardless of root shape: sman "be fat" from S-M-N.

- Doubled roots are roots that have the final two consonants identical. Doubled stems end with a geminate consonant. Only Forms I, IV, VII, VIII, and X yield a doubled stem from a doubled root. Other forms yield a strong stem. In addition, in most dialects (but not Moroccan), all stems in Form IX are doubled: Egyptian Arabic iḥmáṛṛ/yiḥmáṛṛ "be red, blush" from Ḥ-M-R.

- Assimilated roots are those where the first consonant is a w or a y. Assimilated stems begin with a vowel. Only Form I (and Form IV?) yields assimilated stems and only in the non-past. There are none In Moroccan Arabic.

- Strong roots and stems are those that fall under none of the other categories described above. It is common for a strong stem to correspond with a non-strong root but the reverse is rare.

Table of verb forms

[edit]In this section, all verb classes and their corresponding stems are listed, excluding the small number of irregular verbs described above. Verb roots are indicated schematically using capital letters to stand for consonants in the root:

- F = first consonant of root

- M = middle consonant of three-consonant root

- S = second consonant of four-consonant root

- T = third consonant of four-consonant root

- L = last consonant of root

Hence, the root F-M-L stands for all three-consonant roots, and F-S-T-L stands for all four-consonant roots. (Traditional Arabic grammar uses F-ʕ-L and F-ʕ-L-L, respectively, but the system used here appears in a number of grammars of spoken Arabic dialects and is probably less confusing for English speakers since the forms are easier to pronounce than those involving /ʕ/.)

The following table lists the prefixes and suffixes to be added to mark tense, person, number, gender and the stem form to which they are added. The forms involving a vowel-initial suffix and corresponding stem PAv or NPv are highlighted in silver. The forms involving a consonant-initial suffix and corresponding stem PAc are highlighted in gold. The forms involving no suffix and corresponding stem PA0 or NP0 are not highlighted.

| Tense/Mood | Past | Non-Past | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| 1st | PAc-t | PAc-na | n(e)-NP0 | n(e)-NP0-u/w | |

| 2nd | masculine | PAc-ti | PAc-tiw | t(e)-NP0 | t(e)-NPv-u/w |

| feminine | t(e)-NPv-i/y | ||||

| 3rd | masculine | PA0 | PAv-u/w | y-NP0 | y-NPv-u/w |

| feminine | PAv-et | t(e)-NP0 | |||

The following table lists the verb classes along with the form of the past and non-past stems, active and passive participles, and verbal noun, in addition to an example verb for each class.

Notes:

- Italicized forms are those that follow automatically from the regular rules of deletion of /e/.

- In the past tense, there can be up to three stems:

- When only one form appears, this same form is used for all three stems.

- When three forms appear, these represent first-singular, third-singular and third-plural, which indicate the PAc, PA0 and PAv stems, respectively.

- When two forms appear, separated by a comma, these represent first-singular and third-singular, which indicate the PAc and PA0 stems. When two forms appear, separated by a semicolon, these represent third-singular and third-plural, which indicate the PA0 and PAv stems. In both cases, the missing stem is the same as the third-singular (PA0) stem.

- Not all forms have a separate verb class for hollow or doubled roots. In such cases, the table below has the notation "(use strong form)", and roots of that shape appear as strong verbs in the corresponding form; e.g. Form II strong verb dˤáyyaʕ/yidˤáyyaʕ "waste, lose" related to Form I hollow verb dˤaʕ/yidˤiʕ "be lost", both from root Dˤ-Y-ʕ.

| Form | Strong | Weak | Hollow | Doubled | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Past | Non-Past | Example | Past | Non-Past | Example | Past | Non-Past | Example | Past | Non-Past | Example | |

| I | FMeL; FeMLu | yFMeL, yFeMLu | kteb/ykteb "write", ʃrˤeb/yʃrˤeb "drink" | FMit, FMa | yFMi | rˤma/yrˤmi "throw", ʃra/yʃri "buy" | FeLt, FaL | yFiL | baʕ/ybiʕ "sell", ʒab/yʒib "bring" | FeMMit, FeMM | yFeMM | ʃedd/yʃedd "close", medd/ymedd "hand over" |

| yFMoL, yFeMLu | dxel/ydxol "enter", sken/yskon "reside" | yFMa | nsa/ynsa "forget" | yFuL | ʃaf/yʃuf "see", daz/yduz "pass" | FoMMit, FoMM | yFoMM | koħħ/ykoħħ "cough" | ||||

| yFMu | ħba/yħbu "crawl" | yFaL | xaf/yxaf "sleep", ban/yban "seem" | |||||||||

| FoLt, FaL | yFuL | qal/yqul "say", kan/ykun "be" (the only examples) | ||||||||||

| II | FeMMeL; FeMMLu | yFeMMeL, yFeMMLu | beddel/ybeddel "change" | FeMMit, FeMMa | yFeMMi | werra/ywerri "show" | (same as strong) | |||||

| FuwweL; FuwwLu | yFuwweL, yFuwwLu | xuwwef/yxuwwef "frighten" | Fuwwit, Fuwwa | yFuwwi | luwwa/yluwwi "twist" | |||||||

| FiyyeL; FiyyLu | yFiyyeL, yFiyyLu | biyyen/ybiyyen "indicate" | Fiyyit, Fiyya | yFiyyi | qiyya/yqiyyi "make vomit" | |||||||

| III | FaMeL; FaMLu | yFaMeL, yFaMLu | sˤaferˤ/ysˤaferˤ "travel" | FaMit, FaMa | yFaMi | qadˤa/yqadˤi "finish (trans.)", sawa/ysawi "make level" | (same as strong) | FaMeMt/FaMMit, FaM(e)M, FaMMu | yFaM(e)M, yFaMMu | sˤaf(e)f/ysˤaf(e)f "line up (trans.)" | ||

| Ia(VIIt) | tteFMeL; ttFeMLu | ytteFMeL, yttFeMLu | ttekteb/yttekteb "be written" | tteFMit, tteFMa | ytteFMa | tterˤma/ytterˤma "be thrown", ttensa/yttensa "be forgotten" | ttFaLit/ttFeLt/ttFaLt, ttFaL | yttFaL | ttbaʕ/yttbaʕ "be sold" | ttFeMMit, ttFeMM | yttFeMM | ttʃedd/yttʃedd "be closed" |

| ytteFMoL, yttFeMLu | ddxel/yddxol "be entered" | yttFoMM | ttfekk/yttfokk "get loose" | |||||||||

| IIa(V) | tFeMMeL; tFeMMLu | ytFeMMeL, ytFeMMLu | tbeddel/ytbeddel "change (intrans.)" | tFeMMit, tFeMMa | ytFeMMa | twerra/ytwerra "be shown" | (same as strong) | |||||

| tFuwweL; tFuwwLu | ytFuwweL, ytFuwwLu | txuwwef/ytxuwwef "be frightened" | tFuwwit, tFuwwa | ytFuwwa | tluwwa/ytluwwa "twist (intrans.)" | |||||||

| tFiyyeL; tFiyyLu | ytFiyyeL, ytFiyyLu | tbiyyen/ytbiyyen "be indicated" | tFiyyit, tFiyya | ytFiyya | tqiyya/ytqiyya "be made to vomit" | |||||||

| IIIa(VI) | tFaMeL; tFaMLu | ytFaMeL, ytFaMLu | tʕawen/ytʕawen "cooperate" | tFaMit, tFaMa | ytFaMa | tqadˤa/ytqadˤa "finish (intrans.)", tħama/ytħama "join forces" | (same as strong) | tFaMeMt/tFaMMit, tFaM(e)M, tFaMMu | ytFaM(e)M, ytFaMMu | tsˤaf(e)f/ytsˤaf(e)f "get in line", twad(e)d/ytwad(e)d "give gifts to one another" | ||

| VIII | FtaMeL; FtaMLu | yFtaMeL, yFtaMLu | ħtarˤem/ħtarˤem "respect", xtarˤeʕ/xtarˤeʕ "invent" | FtaMit, FtaMa | yFtaMi | ??? | FtaLit/FteLt/FtaLt, FtaL | yFtaL | xtarˤ/yxtarˤ "choose", ħtaʒ/yħtaʒ "need" | FteMMit, FteMM | yFteMM | htemm/yhtemm "be interested (in)" |

| IX | FMaLit/FMeLt/FMaLt, FMaL | yFMaL | ħmarˤ/yħmarˤ "be red, blush", sman/ysman "be(come) fat" | (same as strong) | ||||||||

| X | steFMeL; steFMLu | ysteFMeL, ysteFMLu | steɣrˤeb/ysteɣrˤeb "be surprised" | steFMit, steFMa | ysteFMi | stedʕa/ystedʕi "invite" | (same as strong) | stFeMMit, stFeMM | ystFeMM | stɣell/ystɣell "exploit" | ||

| ysteFMa | stehza/ystehza "ridicule", stăʕfa/ystăʕfa "resign" | |||||||||||

| Iq | FeSTeL; FeSTLu | yFeSTeL, yFeSTLu | tˤerˤʒem/ytˤerˤʒem "translate", melmel/ymelmel "move (trans.)", hernen/yhernen "speak nasally" | FeSTit, FeSTa | yFeSTi | seqsˤa/yseqsˤi "ask" | (same as strong) | |||||

| FiTeL; FiTLu | yFiTeL, yFiTLu | sˤifetˤ/ysˤifetˤ "send", ritel/yritel "pillage" | FiTit, FiTa | yFiTi | tira/ytiri "shoot" | |||||||

| FuTeL; FuTLu | yFuTeL, yFuTLu | suger/ysuger "insure", suret/ysuret "lock" | FuTit, FuTa | yFuTi | rula/yruli "roll (trans.)" | |||||||

| FiSTeL; FiSTLu | yFiSTeL, yFiSTLu | birˤʒez??? "cause to act bourgeois???", biznes??? "cause to deal in drugs" | F...Tit, F...Ta | yF...Ti | blˤana, yblˤani "scheme, plan", fanta/yfanti "dodge, fake", pidˤala/ypidˤali "pedal" | |||||||

| Iqa(IIq) | tFeSTeL; tFeSTLu | ytFeSTeL, ytFeSTLu | tˤtˤerˤʒem/ytˤtˤerˤʒem "be translated", tmelmel/ytmelmel "move (intrans.)" | tFeSTit, tFeSTa | ytFeSTa | tseqsˤa/ytseqsˤa "be asked" | (same as strong) | |||||

| tFiTeL; tFiTLu | ytFiTeL, ytFiTLu | tsˤifetˤ/ytsˤifetˤ "be sent", tritel/ytritel "be pillaged" | tFiTit, tFiTa | ytFiTa | ttira/yttiri "be shot" | |||||||

| tFuTeL; tFuTLu | ytFuTeL, ytFuTLu | tsuger/ytsuger "be insured", tsuret/ytsuret "be locked" | tFuTit, tFuTa | ytFuTa | trula/ytruli "roll (intrans.)" | |||||||

| tFiSTeL; tFiSTLu | ytFiSTeL, ytFiSTLu | tbirˤʒez "act bourgeois", tbiznes "deal in drugs" | tF...Tit, tF...Ta | ytF...Ta | tblˤana/ytblˤana "be planned", tfanta/ytfanta "be dodged", tpidˤala/ytpidˤala "be pedaled" | |||||||

Sample Paradigms of Strong Verbs

[edit]Regular verb, form I, fʕel/yfʕel

[edit]Example: kteb/ykteb "write"

| Tense/Mood | Past | Present Subjunctive | Present Indicative | Future | Imperative | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| 1st | kteb-t | kteb-na | ne-kteb | n-ketb-u | ka-ne-kteb | ka-n-ketb-u | ɣa-ne-kteb | ɣa-n-ketb-u | |||

| 2nd | masculine | kteb-ti | kteb-tiw | te-kteb | t-ketb-u | ka-te-kteb | ka-t-ketb-u | ɣa-te-kteb | ɣa-t-ketb-u | kteb | ketb-u |

| feminine | t-ketb-i | ka-t-ketb-i | ɣa-t-ketb-i | ketb-i | |||||||

| 3rd | masculine | kteb | ketb-u | y-kteb | y-ketb-u | ka-y-kteb | ka-y-ketb-u | ɣa-y-kteb | ɣa-y-ketb-u | ||

| feminine | ketb-et | te-kteb | ka-te-kteb | ɣa-te-kteb | |||||||

Some comments:

- Boldface, here and elsewhere in paradigms, indicate unexpected deviations from some previously established pattern.

- The present indicative is formed from the subjunctive by the addition of /ka-/. Similarly, the future is formed from the subjunctive by the addition of /ɣa-/.

- The imperative is also formed from the second-person subjunctive, this by the removal of any prefix /t-/, /te-/, or /d-/.

- The stem /kteb/ changes to /ketb-/ before a vowel.

- Prefixes /ne-/ and /te-/ keep the vowel before two consonants but drop it before one consonant; hence singular /ne-kteb/ changes to plural /n-ketb-u/.

Example: kteb/ykteb "write": non-finite forms

| Number/Gender | Active Participle | Passive Participle | Verbal Noun |

|---|---|---|---|

| Masc. Sg. | kateb | mektub | ketaba |

| Fem. Sg. | katb-a | mektub-a | |

| Pl. | katb-in | mektub-in |

Regular verb, form I, fʕel/yfʕel, assimilation-triggering consonant

[edit]Example: dker/ydker "mention"

| Tense/Mood | Past | Present Subjunctive | Present Indicative | Future | Imperative | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| 1st | dker-t | dker-na | n-dker | n-dekr-u | ka-n-dker | ka-n-dekr-u | ɣa-n-dker | ɣa-n-dekr-u | |||

| 2nd | masculine | dker-ti | dker-tiw | d-dker | d-dekr-u | ka-d-dker | ka-d-dekr-u | ɣa-d-dker | ɣa-d-dekr-u | dker | dekr-u |

| feminine | d-dekr-i | ka-d-dekr-i | ɣa-d-dekr-i | dekr-i | |||||||

| 3rd | masculine | dker | dekr-u | y-dker | y-dekr-u | ka-y-dker | ka-y-dekr-u | ɣa-y-dker | ɣa-y-dekr-u | ||

| feminine | dekr-et | d-dker | ka-d-dker | ɣa-d-dker | |||||||

This paradigm differs from kteb/ykteb in the following ways:

- /ne-/ is always reduced to /n-/.

- /te-/ is always reduced to /t-/, and then all /t-/ are assimilated to /d-/.

Reduction and assimilation occur as follows:

- Before a coronal stop /t/, /tˤ/, /d/ or /dˤ/, /ne-/ and /te-/ are always reduced to /n-/ and /t-/.

- Before a coronal fricative /s/, /sˤ/, /z/, /zˤ/, /ʃ/ or /ʒ/, /ne-/ and /te-/ are optionally reduced to /n-/ and /t-/. The reduction usually happens in normal and fast speech but not in slow speech.

- Before a voiced coronal /d/, /dˤ/, /z/, /zˤ/, or /ʒ/, /t-/ is assimilated to /d-/.

Examples:

- Required reduction /n-them/ "I accuse", /t-them/ "you accuse".

- Optional reduction /n-skon/ or /ne-skon/ "I reside", /te-skon/ or /t-skon/ "you reside".

- Optional reduction/assimilation /te-ʒberˤ/ or /d-ʒberˤ/ "you find".

Regular verb, form I, fʕel/yfʕol

[edit]Example: xrˤeʒ/yxrˤoʒ "go out"

| Tense/Mood | Past | Present Subjunctive | Present Indicative | Future | Imperative | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| 1st | xrˤeʒ-t | xrˤeʒ-na | ne-xrˤoʒ | n-xerˤʒ-u | ka-ne-xrˤoʒ | ka-n-xerˤʒ-u | ɣa-ne-xrˤoʒ | ɣa-n-xerˤʒ-u | |||

| 2nd | masculine | xrˤeʒ-ti | xrˤeʒ-tiw | te-xrˤoʒ | t-xerˤʒ-u | ka-te-xrˤoʒ | ka-t-xerˤʒ-u | ɣa-te-xrˤoʒ | ɣa-t-xerˤʒ-u | xrˤoʒ | xerˤʒ-u |

| feminine | t-xerˤʒ-i | ka-t-xerˤʒ-i | ɣa-t-xerˤʒ-i | xerˤʒ-i | |||||||

| 3rd | masculine | xrˤeʒ | xerˤʒ-u | y-xrˤoʒ | y-xerˤʒ-u | ka-y-xrˤoʒ | ka-y-xerˤʒ-u | ɣa-y-xrˤoʒ | ɣa-y-xerˤʒ-u | ||

| feminine | xerˤʒ-et | te-xrˤoʒ | ka-te-xrˤoʒ | ɣa-te-xrˤoʒ | |||||||

Regular verb, form II, feʕʕel/yfeʕʕel

[edit]Example: beddel/ybeddel "change"

| Tense/Mood | Past | Present Subjunctive | Present Indicative | Future | Imperative | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| 1st | beddel-t | beddel-na | n-beddel | n-beddl-u | ka-n-beddel | ka-n-beddl-u | ɣa-n-beddel | ɣa-n-beddl-u | |||

| 2nd | masculine | beddel-ti | beddel-tiw | t-beddel | t-beddl-u | ka-t-beddel | ka-t-beddl-u | ɣa-t-beddel | ɣa-t-beddl-u | beddel | beddl-u |

| feminine | t-beddl-i | ka-t-beddl-i | ɣa-t-beddl-i | beddl-i | |||||||

| 3rd | masculine | beddel | beddl-u | y-beddel | y-beddl-u | ka-y-beddel | ka-y-beddl-u | ɣa-y-beddel | ɣa-y-beddl-u | ||

| feminine | beddl-et | t-beddel | ka-t-beddel | ɣa-t-beddel | |||||||

Boldfaced forms indicate the primary differences from the corresponding forms of kteb, which apply to many classes of verbs in addition to form II strong:

- The prefixes /t-/, /n-/ always appear without any stem vowel. This behavior is seen in all classes where the stem begins with a single consonant (which includes most classes).

- The /e/ in the final vowel of the stem is elided when a vowel-initial suffix is added. This behavior is seen in all classes where the stem ends in /-VCeC/ or/-VCCeC/ (where /V/ stands for any vowel and /C/ for any consonant). In addition to form II strong, this includes form III strong, form III Due to the regular operation of the stress rules, the stress in the past tense forms beddel-et and beddel-u differs from dexl-et and dexl-u.

Regular verb, form III, faʕel/yfaʕel

[edit]Example: sˤaferˤ/ysˤaferˤ "travel"

| Tense/Mood | Past | Present Subjunctive | Present Indicative | Future | Imperative | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| 1st | sˤaferˤ-t | sˤaferˤ-na | n-sˤaferˤ | n-sˤafrˤ-u | ka-n-sˤaferˤ | ka-n-sˤafrˤ-u | ɣa-n-sˤaferˤ | ɣa-n-sˤafrˤ-u | |||

| 2nd | masculine | sˤaferˤ-t | sˤaferˤ-tiw | t-sˤaferˤ | t-sˤafrˤ-u | ka-t-sˤaferˤ | ka-t-sˤafrˤ-u | ɣa-t-sˤaferˤ | ɣa-t-sˤafrˤ-u | sˤaferˤ | sˤafrˤ-u |

| feminine | t-sˤafrˤ-i | ka-t-sˤafrˤ-i | ɣa-t-sˤafrˤ-i | sˤafrˤ-i | |||||||

| 3rd | masculine | sˤaferˤ | sˤafrˤ-u | y-sˤaferˤ | y-sˤafrˤ-u | ka-y-sˤaferˤ | ka-y-sˤafrˤ-u | ɣa-y-sˤaferˤ | ɣa-y-sˤafrˤ-u | ||

| feminine | sˤafrˤ-et | t-sˤaferˤ | ka-t-sˤaferˤ | ɣa-t-sˤaferˤ | |||||||

The primary differences from the corresponding forms of beddel (shown in boldface) are:

- The long vowel /a/ becomes /a/ when unstressed.

- The /i/ in the stem /safir/ is elided when a suffix beginning with a vowel follows.

Regular verb, form Ia, ttefʕel/yttefʕel

[edit]Example: ttexleʕ/yttexleʕ "get scared"

| Tense/Mood | Past | Present Subjunctive | Present Indicative | Future | Imperative | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| 1st | ttexleʕ-t | ttexleʕ-na | n-ttexleʕ | n-ttxelʕ-u | ka-n-ttexleʕ | ka-n-ttxelʕ-u | ɣa-n-ttexleʕ | ɣa-n-ttxelʕ-u | |||

| 2nd | masculine | ttexleʕ-ti | ttexleʕ-tiw | (te-)ttexleʕ | (te-)ttxelʕ-u | ka-(te-)ttexleʕ | ka-(te-)ttxelʕ-u | ɣa-(te-)ttexleʕ | ɣa-(te-)ttxelʕ-u | ttexleʕ | ttxelʕ-u |

| feminine | (te-)ttxelʕ-i | ka-(te-)ttxelʕ-i | ɣa-(te-)ttxelʕ-i | ttxelʕ-i | |||||||

| 3rd | masculine | ttexleʕ | ttxelʕ-u | y-ttexleʕ | y-ttxelʕ-u | ka-y-ttexleʕ | ka-y-ttxelʕ-u | ɣa-y-ttexleʕ | ɣa-y-ttxelʕ-u | ||

| feminine | ttxelʕ-et | (te-)ttexleʕ | ka-(te-)ttexleʕ | ɣa-(te-)ttexleʕ | |||||||

Sample Paradigms of Weak Verbs

[edit]Weak verbs have a W or Y as the last root consonant.

Weak, form I, fʕa/yfʕa

[edit]Example: nsa/ynsa "forget"

| Tense/Mood | Past | Present Subjunctive | Present Indicative | Future | Imperative | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| 1st | nsi-t | nsi-na | ne-nsa | ne-nsa-w | ka-ne-nsa | ka-ne-nsa-w | ɣa-ne-nsa | ɣa-ne-nsa-w | |||

| 2nd | masculine | nsi-ti | nsi-tiw | te-nsa | te-nsa-w | ka-te-nsa | ka-te-nsa-w | ɣa-te-nsa | ɣa-te-nsa-w | nsa | nsa-w |

| feminine | te-nsa-y | ka-te-nsa-y | ɣa-te-nsa-y | nsa-y | |||||||

| 3rd | masculine | nsa | nsa-w | y-nsa | y-nsa-w | ka-y-nsa | ka-y-nsa-w | ɣa-y-nsa | ɣa-y-nsa-w | ||

| feminine | nsa-t | te-nsa | ka-te-nsa | ɣa-te-nsa | |||||||

The primary differences from the corresponding forms of kteb (shown in ) are:

- There is no movement of the sort occurring in kteb vs. ketb-.

- Instead, in the past, there are two stems: nsi- in the first and second persons and nsa- in the third person. In the non-past, there is a single stem nsa.

- Because the stems end in a vowel, normally vocalic suffixes assume consonantal form:

- Plural -u becomes -w.

- Feminine singular non-past -i becomes -y.

- Feminine singular third-person past -et becomes -t.

Weak verb, form I, fʕa/yfʕi

[edit]Example: rˤma/yrˤmi "throw"

| Tense/Mood | Past | Present Subjunctive | Present Indicative | Future | Imperative | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| 1st | rˤmi-t | rˤmi-na | ne-rˤmi | ne-rˤmi-w | ka-ne-rˤmi | ka-ne-rˤmi-w | ɣa-ne-rˤmi | ɣa-ne-rˤmi-w | |||

| 2nd | masculine | rˤmi-ti | rˤmi-tiw | te-rˤmi | te-rˤmi-w | ka-te-rˤmi | ka-te-rˤmi-w | ɣa-te-rˤmi | ɣa-te-rˤmi-w | rˤmi | rˤmi-w |

| feminine | |||||||||||

| 3rd | masculine | rˤma | rˤma-w | y-rˤmi | y-rˤmi-w | ka-y-rˤmi | ka-y-rˤmi-w | ɣa-y-rˤmi | ɣa-y-rˤmi-w | ||

| feminine | rˤma-t | te-rˤmi | ka-te-rˤmi | ɣa-te-rˤmi | |||||||

This verb type is quite similar to the weak verb type nsa/ynsa. The primary differences are:

- The non-past stem has /i/ instead of /a/. The occurrence of one vowel or the other varies from stem to stem in an unpredictable fashion.

- -iy in the feminine singular non-past is simplified to -i, resulting in homonymy between masculine and feminine singular.

Verbs other than form I behave as follows in the non-past:

- Form X has either /a/ or /i/.

- Mediopassive verb forms—i.e. Ia(VIIt), IIa(V), IIIa(VI) and Iqa(IIq) – have /a/.

- Other forms—i.e. II, III and Iq—have /i/.

Examples:

- Form II: wedda/yweddi "fulfill"; qewwa/yqewwi "strengthen"

- Form III: qadˤa/yqadˤi "finish"; dawa/ydawi "treat, cure"

- Form Ia(VIIt): ttensa/yttensa "be forgotten"

- Form IIa(V): tqewwa/ytqewwa "become strong"

- Form IIIa(VI): tqadˤa/ytqadˤa "end (intrans.)"

- Form VIII: (no examples?)

- Form IX: (behaves as a strong verb)

- Form X: stedʕa/ystedʕi "invite"; but stehza/ystehza "ridicule", steħla/ysteħla "enjoy", steħya/ysteħya "become embarrassed", stăʕfa/ystăʕfa "resign"

- Form Iq: (need example)

- Form Iqa(IIq): (need example)

Sample Paradigms of Hollow Verbs

[edit]Hollow verbs have a W or Y as the middle root consonant. Note that for some forms (e.g. form II and form III), hollow verbs are conjugated as strong verbs (e.g. form II ʕeyyen/yʕeyyen "appoint" from ʕ-Y-N, form III ʒaweb/yʒaweb "answer" from ʒ-W-B).

Hollow verb, form I, fal/yfil

[edit]Example: baʕ/ybiʕ "sell"

| Tense/Mood | Past | Present Subjunctive | Present Indicative | Future | Imperative | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| 1st | beʕ-t | beʕ-na | n-biʕ | n-biʕ-u | ka-n-biʕ | ka-n-biʕ-u | ɣa-n-biʕ | ɣa-n-biʕ-u | |||

| 2nd | masculine | beʕ-ti | beʕ-tiw | t-biʕ | t-biʕ-u | ka-t-biʕ | ka-t-biʕ-u | ɣa-t-biʕ | ɣa-t-biʕ-u | biʕ | biʕ-u |

| feminine | t-biʕ-i | ka-t-biʕ-i | ɣa-t-biʕ-i | biʕ-i | |||||||

| 3rd | masculine | baʕ | baʕ-u | y-biʕ | y-biʕ-u | ka-y-biʕ | ka-y-biʕ-u | ɣa-y-biʕ | ɣa-y-biʕ-u | ||

| feminine | baʕ-et | t-biʕ | ka-t-biʕ | ɣa-t-biʕ | |||||||

This verb works much like beddel/ybeddel "teach". Like all verbs whose stem begins with a single consonant, the prefixes differ in the following way from those of regular and weak form I verbs:

- The prefixes /t-/, /j-/, /ni-/ have elision of /i/ following /ka-/ or /ɣa-/.

- The imperative prefix /i-/ is missing.

In addition, the past tense has two stems: beʕ- before consonant-initial suffixes (first and second person) and baʕ- elsewhere (third person).

Hollow verb, form I, fal/yful

[edit]Example: ʃaf/yʃuf "see"

| Tense/Mood | Past | Present Subjunctive | Present Indicative | Future | Imperative | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| 1st | ʃef-t | ʃef-na | n-ʃuf | n-ʃuf-u | ka-n-ʃuf | ka-n-ʃuf-u | ɣa-n-ʃuf | ɣa-n-ʃuf-u | |||

| 2nd | masculine | ʃef-ti | ʃef-tiw | t-ʃuf | t-ʃuf-u | ka-t-ʃuf | ka-t-ʃuf-u | ɣa-t-ʃuf | ɣa-t-ʃuf-u | ʃuf | ʃuf-u |

| feminine | t-ʃuf-i | ka-t-ʃuf-i | ɣa-t-ʃuf-i | ʃuf-i | |||||||

| 3rd | masculine | ʃaf | ʃaf-u | y-ʃuf | y-ʃuf-u | ka-y-ʃuf | ka-y-ʃuf-u | ɣa-y-ʃuf | ɣa-y-ʃuf-u | ||

| feminine | ʃaf-et | t-ʃuf | ka-t-ʃuf | ɣa-t-ʃuf | |||||||

This verb class is identical to verbs such as baʕ/ybiʕ except in having stem vowel /u/ in place of /i/.

Sample Paradigms of Doubled Verbs

[edit]Doubled verbs have the same consonant as middle and last root consonant, e.g. ɣabb/yiħebb "love" from Ħ-B-B.

Doubled verb, form I, feʕʕ/yfeʕʕ

[edit]Example: ħebb/yħebb "love"

| Tense/Mood | Past | Present Subjunctive | Present Indicative | Future | Imperative | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| 1st | ħebbi-t | ħebbi-na | n-ħebb | n-ħebb-u | ka-n-ħebb | ka-n-ħebb-u | ɣa-n-ħebb | ɣa-n-ħebb-u | |||

| 2nd | masculine | ħebbi-ti | ħebbi-tiw | t-ħebb | t-ħebb-u | ka-t-ħebb | ka-t-ħebb-u | ɣa-t-ħebb | ɣa-t-ħebb-u | ħebb | ħebb-u |

| feminine | t-ħebb-i | ka-t-ħebb-i | ɣa-t-ħebb-i | ħebb-i | |||||||

| 3rd | masculine | ħebb | ħebb-u | y-ħebb | y-ħebb-u | ka-y-ħebb | ka-y-ħebb-u | ɣa-y-ħebb | ɣa-y-ħebb-u | ||

| feminine | ħebb-et | t-ħebb | ka-t-ħebb | ɣa-t-ħebb | |||||||

This verb works much like baʕ/ybiʕ "sell". Like that class, it has two stems in the past, which are ħebbi- before consonant-initial suffixes (first and second person) and ħebb- elsewhere (third person). Note that /i-/ was borrowed from the weak verbs; the Classical Arabic equivalent form would be *ħabáb-, e.g. *ħabáb-t.

Some verbs have /o/ in the stem: koħħ/ykoħħ "cough".

As for the other forms:

- Form II, V doubled verbs are strong: ɣedded/yɣedded "limit, fix (appointment)"

- Form III, VI doubled verbs optionally behave either as strong verbs or similar to ħebb/yħebb: sˤafef/ysˤafef or sˤaff/ysˤaff "line up (trans.)"

- Form VIIt doubled verbs behave like ħebb/yħebb: ttʕedd/yttʕedd

- Form VIII doubled verbs behave like ħebb/yħebb: htemm/yhtemm "be interested (in)"

- Form IX doubled verbs probably don't exist, and would be strong if they did exist.

- Form X verbs behave like ħebb/yħebb: stɣell/ystɣell "exploit".

Sample Paradigms of Doubly Weak Verbs

[edit]"Doubly weak" verbs have more than one "weakness", typically a W or Y as both the second and third consonants. In Moroccan Arabic such verbs generally behave as normal weak verbs (e.g. ħya/yħya "live" from Ħ-Y-Y, quwwa/yquwwi "strengthen" from Q-W-Y, dawa/ydawi "treat, cure" from D-W-Y). This is not always the case in standard Arabic (cf. walā/yalī "follow" from W-L-Y).

Paradigms of Irregular Verbs

[edit]The irregular verbs are as follows:

- dda/yddi "give" (inflects like a normal weak verb; active participle dday or meddi, passive participle meddi)

- ʒa/yʒi "come" (inflects like a normal weak verb, except imperative aʒi (sg.), aʒiw (pl.); active participle maʒi or ʒay)

- kla/yakol (or kal/yakol) "eat" and xda/yaxod (or xad/yaxod) "take" (see paradigm below; active participle wakel, waxed; passive participle muwkul, muwxud):

| Tense/Mood | Past | Present Subjunctive | Present Indicative | Future | Imperative | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| 1st | kli-t | kli-na | na-kol | na-kl-u | ka-na-kol | ka-na-kl-u | ɣa-na-kol | ɣa-na-kl-u | |||

| 2nd | masculine | kli-ti | kli-tiw | ta-kol | ta-kl-u | ka-ta-kol | ka-ta-kl-u | ɣa-ta-kol | ɣa-ta-kl-u | kul | kul-u |

| feminine | ta-kl-i | ka-ta-kl-i | ɣa-ta-kl-i | kul-i | |||||||

| 3rd | masculine | kla | kla-w | ya-kol | ya-kl-u | ka-ya-kol | ka-ya-kl-u | ɣa-ya-kol | ɣa-ya-kl-u | ||

| feminine | kla-t | ta-kol | ka-ta-kol | ɣa-ta-kol | |||||||

Social features

[edit]Evolution

[edit]In general, Moroccan Arabic is one of the least conservative of all Arabic languages. Now, Moroccan Arabic continues to integrate new French words, even English ones due to its influence as the modern lingua franca, mainly technological and modern words. However, in recent years, constant exposure to Modern Standard Arabic on television and in print media and a certain desire among many Moroccans for a revitalization of an Arab identity has inspired many Moroccans to integrate words from Modern Standard Arabic, replacing their French, Spanish or otherwise non-Arabic counterparts, or even speaking in Modern Standard Arabic[dubious – discuss] while keeping the Moroccan accent to sound less formal.[34]

Though rarely written, Moroccan Arabic is currently undergoing an unexpected and pragmatic revival. It is now the preferred language in Moroccan chat rooms or for sending SMS, using Arabic Chat Alphabet composed of Latin letters supplemented with the numbers 2, 3, 5, 7 and 9 for coding specific Arabic sounds, as is the case with other Arabic speakers.

The language continues to evolve quickly as can be noted by consulting the Colin dictionary. Many words and idiomatic expressions recorded between 1921 and 1977 are now obsolete.

Code-switching

[edit]Some Moroccan Arabic speakers, in the parts of the country formerly ruled by France, practice code-switching with French. In parts of northern Morocco, such as in Tetouan and Tangier, it is common for code-switching to occur between Moroccan Arabic, Modern Standard Arabic, and Spanish, as Spain had previously controlled part of the region and continues to possess the territories of Ceuta and Melilla in North Africa bordering only Morocco. On the other hand, some Arab nationalist Moroccans generally attempt to avoid French and Spanish in their speech; consequently, their speech tends to resemble old Andalusian Arabic.

Literature

[edit]Although most Moroccan literature has traditionally been written in the classical Standard Arabic, the first record of a work of literature composed in Moroccan Arabic was Al-Kafif az-Zarhuni's al-Mala'ba, written in the Marinid period.[35]

There exists some poetry written in Moroccan Arabic like the Malhun. In the troubled and autocratic Morocco of the 1970s, Years of Lead, the Nass El Ghiwane band wrote lyrics in Moroccan Arabic that were very appealing to the youth even in other Maghreb countries.

Another interesting movement is the development of an original rap music scene, which explores new and innovative usages of the language.

Zajal, or improvised poetry, is mostly written in Moroccan Darija, and there have been at least dozens of Moroccan Darija poetry collections and anthologies published by Moroccan poets, such as Ahmed Lemsyeh[36] and Driss Amghar Mesnaoui. The later additionally wrote a novel trilogy in Moroccan Darija, a unique creation in this language, with the titles تاعروروت "Ta'arurut", عكاز الريح (the Wind's Crutch), and سعد البلدة (The Town's Luck).[37]

Scientific production

[edit]The first known scientific productions written in Moroccan Arabic were released on the Web in early 2010 by Moroccan teacher and physicist Farouk Taki El Merrakchi, three average-sized books dealing with physics and mathematics.[38]

Newspapers

[edit]There have been at least three newspapers in Moroccan Arabic; their aim was to bring information to people with a low level of education, or those simply interested in promoting the use of Moroccan Darija. From September 2006 to October 2010, Telquel Magazine had a Moroccan Arabic edition Nichane. From 2002 to 2006 there was also a free weekly newspaper that was entirely written in "standard" Moroccan Arabic: Khbar Bladna ('News of Our Country'). In Salé, the regional newspaper Al Amal, directed by Latifa Akherbach, started in 2005.[39]

The Moroccan online newspaper Goud or "ݣود" has much of its content written in Moroccan Arabic rather than Modern Standard Arabic. Its name "Goud" and its slogan "dima nishan" (ديما نيشان) are Moroccan Arabic expressions that mean almost the same thing "straightforward".[40]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Moroccan Arabic at Ethnologue (28th ed., 2025)

- ^ Ennaji, Moha (1998). Arabic Varieties in North Africa. Centre for Advanced Studies of African Soc. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-919799-12-4.

- ^ a b Manbahī, Muḥammad al-Madlāwī; منبهي، محمد المدلاوي. (2019). al-ʻArabīyah al-Dārijah : imlāʼīyah wa-naḥw العربية الدارجة : إملائية ونحو (1st ed.). Zākūrah. ISBN 978-9920-38-197-0. OCLC 1226918654.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Abdel-Massih, Ernest Tawfik (1973). An Introduction to Moroccan Arabic. Center for Near Eastern and North African Studies, University of Michigan. ISBN 9780932098078.

- ^ Yabiladi.com. "Darija, a lingua franca influenced by both Arabic Tamazight and". en.yabiladi.com. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ Gauthier, Christophe. "كلمة افتتاحية للسيد المندوب السامي للتخطيط بمناسبة الندوة الصحفية الخاصة بتقديم معطيات الإحصاء العام للسكان والسكنى 2024". Site institutionnel du Haut-Commissariat au Plan du Royaume du Maroc (in French). Retrieved 23 December 2024.

- ^ A. Bernard & P. Moussard, « Arabophones et Amazighophones au Maroc », Annales de Géographie, no.183 (1924), pp.267-282.

- ^ a b D. Caubet, Questionnaire de dialectologie du Maghreb Archived 2013-11-12 at the Wayback Machine, in: EDNA vol.5 (2000-2001), pp.73-92

- ^ a b c S. Levy, Repères pour une histoire linguistique du Maroc, in: EDNA no.1 (1996), pp.127-137

- ^ Turner, Mike (18 February 2019). "Moroccan Arabic". In Huehnergard, John; Pat-El, Na’ama (eds.). The Semitic Languages. Routledge. p. 459. ISBN 978-0-429-65538-8.

- ^ Boumans, Louis; de Ruiter, Jan Jaap (13 May 2013). "Moroccan Arabic in the European diaspora". In Rouchdy, Aleya (ed.). Language Contact and Language Conflict in Arabic. Routledge. p. 262. ISBN 978-1-136-12218-7.

- ^ Dahbi, Mohammed (28 July 2023). "Language Choice, Literacy, and Education Quality in Morocco". In Joshi, R. Malatesha; McBride, Catherine A.; Kaani, Bestern; Elbeheri, Gad (eds.). Handbook of Literacy in Africa. Springer Nature. p. 170. ISBN 978-3-031-26250-0.

- ^ a b c K. Versteegh, Dialects of Arabic: Maghreb Dialects Archived 2015-07-15 at the Wayback Machine, teachmideast.org

- ^ The dialects of Ouezzane, Chefchaouen, Asilah, Larache, Ksar el-Kebir and Tangiers are influenced by the neighbouring mountain dialects. The dialects of Marrakech and Meknes are influenced by Bedouin dialects. The old urban dialect formerly spoken in Azemmour is extinct.

- ^ a b L. Messaoudi, Variations linguistiques: images urbaines et sociales, in: Cahiers de Sociolinguistique, no.6 (2001), pp.87-98

- ^ A. Zouggari & J. Vignet-Zunz, Jbala: Histoire et société, dans Sciences Humaines, (1991) (ISBN 2-222-04574-6)

- ^ "Glottolog 4.6 - Judeo-Moroccan Arabic". glottolog.org. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ François Decret, Les invasions hilaliennes en Ifrîqiya

- ^ J. Grand'Henry, Les parlers arabes de la région du Mzāb, Brill, 1976, pp.4-5

- ^ M. El Himer, Zones linguistiques du Maroc arabophone: contacts et effets à Salé Archived 2015-04-13 at the Wayback Machine, in: Between the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, Studies on Contemporary Arabic, 7th AIDA Conference, 2006, held in Vienna

- ^ Caubet (2007), p. 3

- ^ a b c d Gottreich, Emily (2020). Jewish Morocco. I.B. Tauris. doi:10.5040/9781838603601. ISBN 978-1-78076-849-6. S2CID 213996367.

- ^ "الخطاب السياسي لدة العامة في مغرب العصر المريني - ملعبة الكفيف الزرهوني نموذجا" (PDF). هيسبريس تمودا العدد XLIX، 2014، ص 13-32. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 December 2019.

- ^ "الملعبة، أقدم نص بالدارجة المغربية". Archived from the original on 27 June 2018.

- ^ "Farouk El Merrakchi Taki, professeur de physique en France, s'est lancé dans la rédaction de manuels scientifiques en darija" (in French). 26 November 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ Moha Ennaji (20 January 2005). Multilingualism, Cultural Identity, and Education in Morocco. Springer Science & Business Media (published 5 December 2005). p. 2019. ISBN 9780387239804.

- ^ a b Valentina Ferrara (2017). "À propos de la darija" (in French).

- ^ Martin Haspelmath; Uri Tadmor (22 December 2009). Loanwords in the World's Languages: A Comparative Handbook. Walter de Gruyter. p. 195. ISBN 978-3-11-021844-2.

- ^ Elimam, Abdou (2009). Du Punique au Maghribi : Trajectoires d'une langue sémito-méditerranéenne (PDF). Synergies Tunisie.

- ^ Chafik, Mohamed (1999). الدارجة المغربية مجال توارد بين الأمازيغية والعربية [Moroccan Darija: a space of exchange between Amazigh and Arabic] (PDF) (in Arabic and Moroccan Arabic). Moroccan Royal Academy. p. 170.

- ^ Morocco-guide.com. "Helpful Moroccan Phrases with pronunciation - Moroccan Arabic".

- ^ "Learn Moroccan Arabic with uTalk". utalk.com. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ Boujenab, Abderrahmane (2011). Moroccan Arabic. Peace Corps Morocco. p. 52.

- ^ Kamusella, Tomasz (December 2017). "The Arabic Language: A Latin of Modernity?" (PDF). Journal of Nationalism, Memory & Language Politics. 11 (2): 117–145. doi:10.1515/jnmlp-2017-0006. Retrieved 11 March 2024.

- ^ "الملعبة، أقدم نص بالدارجة المغربية". 27 May 2018. Archived from the original on 27 June 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ "Publications by Ahmed Lemsyeh" (in Moroccan Arabic and Arabic). Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- ^ "رواية جديدة للمغربي إدريس أمغار المسناوي" [A new novel by Moroccan (writer) Driss Amghar Mesnaoui]. 24 August 2014. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ "Une première: Un Marocain rédige des manuels scientifiques en…". Medias24.com. 26 November 2013.

- ^ "Actualité : La "darija" ou correctement la langue marocaine sort ses griffes". lavieeco.com (in French). 9 June 2006.

- ^ "كود". Goud.

Bibliography

[edit]- Ernest T. Abdel Massih. Introduction to Moroccan Arabic. Washington: Univ. of Michigan, 1982.

- Jordi Aguadé. ‘Notes on the Arabic Dialect of Casablanca’, in: AIDA, 5th Conference Proceedings. Universidad de Cadiz, 2003, pp. 301–8.

- Jordi Aguadé. ‘Morocco (dialectological survey)’, in Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics, vol. 3, Brill, 2007, pp. 287–97.

- Bichr Andjar & Abdennabi Benchehda. Moroccan Arabic Phrasebook, Lonely Planet, 1999.

- Louis Brunot. Introduction à l'arabe marocain. Paris: Maisonneuve, 1950.

- Dominique Caubet. L'arabe marocain. Publ. Peeters, 1993.

- Dominique Caubet. ‘Moroccan Arabic’, in Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics, vol. 3, Brill, 2007, pp. 274–287

- Olivier Durand. L'arabo del Marocco: elementi di dialetto standard e mediano. Rome: Università degli Studi La Sapienza, 2004.

- Richard S. Harrel. A short reference grammar of Moroccan Arabic. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown Univ. Press, 1962.

- Richard S. Harrel. A Dictionary of Moroccan Arabic. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown Univ. Press, 1966.

- Jeffrey Heath. Ablaut and Ambiguity: Phonology of a Moroccan Arabic Dialect. Albany: State Univ. of New York Press, 1987.

- Angela Daiana Langone. ‘Khbar Bladna, une expérience journalistique en arabe dialectal marocain’, in Estudios de dialectologia norteafricana y andalusi, no. 7, 2003, pp. 143–151.

- Angela Daiana Langone. ‘Jeux linguistiques et nouveau style dans la masrahiyya en-Neqsha, Le déclic, écrite en dialecte marocain par Tayyeb Saddiqi’, in Actes d'AIDA 6. Tunis, 2006, pp. 243–261.

- Francisco Moscoso García. Esbozo gramatical del árabe marroquí. Cuenca: Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, 2004.

- Abderrahim Youssi. ‘La triglossie dans la typologie linguistique’, in La Linguistique, no. 19, 1983, pp. 71–83.

- Abderrahim Youssi. Grammaire et lexique de l'arabe marocain moderne. Casablanca: Wallada, 1992.

- Annamaria Ventura & Olivier Durand. Grammatica di arabo marocchino: Lingua dārija. Milan: Hoepli, 2022.

External links

[edit]Moroccan Arabic

View on GrokipediaClassification and Origins

Historical Development