Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Movable type

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on the |

| History of printing |

|---|

|

Movable type (US English; moveable type in British English) is the system and technology of printing and typography that uses movable components to reproduce the elements of a document (usually individual alphanumeric characters or punctuation marks) usually on the medium of paper.

Overview

[edit]The world's first movable type printing technology for paper books was made of porcelain materials and was invented around 1040 AD in China during the Northern Song dynasty by the inventor Bi Sheng (990–1051).[1] The earliest printed paper money with movable metal type to print the identifying code of the money was made in 1161 during the Song dynasty.[2] In 1193, a book in the Song dynasty documented how to use the copper movable type.[3] The oldest extant book printed with movable metal type, Jikji, was printed in Korea in 1377 during the Goryeo dynasty.

The spread of both movable-type systems was, to some degree, limited to primarily East Asia. The creation of the printing press in Europe may have been influenced by various sporadic reports of movable type technology brought back to Europe by returning business people and missionaries to China.[4][5][6] Some of these medieval European accounts are still preserved in the library archives of the Vatican and Oxford University among many others.[7]

Around 1450, German goldsmith Johannes Gutenberg invented the metal movable-type printing press, along with innovations in casting the type based on a matrix and hand mould. The small number of alphabetic characters needed for European languages was an important factor.[8] Gutenberg was the first to create his type pieces from an alloy of lead, tin, and antimony—and these materials remained standard for 550 years.[9]

For alphabetic scripts, movable-type page setting was quicker than woodblock printing. The metal type pieces were more durable and the lettering was more uniform, leading to typography and fonts. The high quality and relatively low price of the Gutenberg Bible (1455) established the superiority of movable type in Europe and the use of printing presses spread rapidly. The printing press may be regarded as one of the key factors fostering the Renaissance[10] and, due to its effectiveness, its use spread around the globe.

The 19th-century invention of hot metal typesetting and its successors caused movable type to decline in the 20th century.

Precursors to movable type

[edit]

Letter punch and coins

[edit]The technique of imprinting multiple copies of symbols or glyphs with a master type punch made of hard metal first developed around 3000 BC in ancient Sumer. These metal punch types can be seen as precursors of the letter punches adapted in later millennia to printing with movable metal type. Cylinder seals were used in Mesopotamia to create an impression on a surface by rolling the seal on wet clay.[11]

Seals and stamps

[edit]Seals and stamps may have been precursors to movable type. The uneven spacing of the impressions on brick stamps found in the Mesopotamian cities of Uruk and Larsa, dating from the 2nd millennium BC, has been conjectured by some archaeologists as evidence that the stamps were made using movable type.[12] The enigmatic Minoan Phaistos Disc of c. 1800–1600 BC has been considered by one scholar as an early example of a body of text being reproduced with reusable characters: it may have been produced by pressing pre-formed hieroglyphic "seals" into the soft clay. A few authors even view the disc as technically meeting all definitional criteria to represent an early incidence of movable-type printing.[13] In the West the practice of sealing documents with an impressed personal or official insignia, typically from a worn signet ring,[14] became established under the Roman Empire, and continued through the Byzantine and Holy Roman empires,[15] into the 19th century, when a wet signature became customary.

Seals in China have been used since at least the Shang dynasty (2nd millennium BCE). In the Western Zhou, sets of seal stamps were encased in blocks of type and used on clay moulds for casting bronzes. By the end of the 3rd century BCE, seals were also used for printing on pottery. In the Northern dynasties textual sources contain references to wooden seals with up to 120 characters.[16] The seals had a religious element to them. Daoists used seals as healing devices by impressing therapeutic characters onto the flesh of sick people. They were also used to stamp food, creating a talismanic character to ward off disease. The first evidence of these practices appeared under a Buddhist context in the mid 5th century CE. Centuries later, seals were used to create hundreds of Buddha images.[16] According to Tsien Tsuen-hsuin, Chinese seals had greater potential to turn into movable type due to their square, rectangular, and flat shape suited to a printing surface, whereas seals in the west were cylindrical or scabaroid, round or oval, and mostly used for pictures rather than writing.[17]

Woodblock printing

[edit]Bones, shells, bamboo slips, metal tablets, stone tablets, silk, as well as other materials were previously used for writing. However, following the invention of paper during the Chinese Han dynasty, writing materials became more portable and economical. Yet, copying books by hand was still labour-consuming. Not until the Xiping Era (172–178 AD), towards the end of the Eastern Han dynasty, did sealing print and monotype appear. These were used to print designs on fabrics and to print texts.

By about the 8th century during the Tang dynasty, woodblock printing was invented and worked as follows. First, the neat hand-copied script was stuck on a relatively thick and smooth board, with the front of the paper sticking to the board, the paper being so thin it was transparent, the characters showing in reverse distinctly so that every stroke could be easily recognized. Then, carvers cut away the parts of the board that were not part of the character, so that the characters were cut in relief, completely differently from those cut intaglio. When printing, the bulging characters would have some ink spread on them and be covered by paper. With workers' hands moving on the back of paper gently, characters would be printed on the paper. By the Song dynasty, woodblock printing came to its heyday. Although woodblock printing played an influential role in spreading culture, there were some significant drawbacks. Carving the printing plate required considerable time, labour, and materials. It also was not convenient to store these plates and was difficult to correct mistakes.

History

[edit]Ceramic movable type

[edit]

Bi Sheng (畢昇) (990–1051) developed the first known movable-type system for printing in China around 1040 AD during the Northern Song dynasty, using ceramic materials.[19][20] As described by the Chinese scholar Shen Kuo (沈括) (1031–1095):

When he wished to print, he took an iron frame and set it on the iron plate. In this he placed the types, set close together. When the frame was full, the whole made one solid block of type. He then placed it near the fire to warm it. When the paste [at the back] was slightly melted, he took a smooth board and pressed it over the surface, so that the block of type became as even as a whetstone.

For each character there were several types, and for certain common characters there were twenty or more types each, in order to be prepared for the repetition of characters on the same page. When the characters were not in use he had them arranged with paper labels, one label for each rhyme-group, and kept them in wooden cases.

If one were to print only two or three copies, this method would be neither simple nor easy. But for printing hundreds or thousands of copies, it was marvelously quick. As a rule he kept two forms going. While the impression was being made from the one form, the type was being put in place on the other. When the printing of the one form was finished, the other was then ready. In this way the two forms alternated and the printing was done with great rapidity.[19]

After his death, ceramic movable type may have spread to the Tangut kingdom of Western Xia, where a Buddhist text known as the Vimalakirti Nirdesa Sutra was found in modern Wuwei, Gansu, dating to the reign of Emperor Renzong of Western Xia (r. 1125-1193). The text features traits that have been identified as hallmarks of ceramic movable type such as the hollowness of the character strokes and deformed and broken strokes.[21] The ceramic movable-type also passed onto Bi Sheng's descendants. The next mention of movable type occurred in 1193 when a Southern Song chief counselor, Zhou Bida (周必大), attributed the movable-type method of printing to Shen Kuo. However Shen Kuo did not invent the movable type but credited it to Bi Sheng in his Dream Pool Essays. Zhou used ceramic type to print print the Yutang Zaji (Notes of the Jade Hall) in 1193. Further evidence of the spread of movable type appears in the Binglü Xiansheng Wenji (Collected Works of Master Palm) by Deng Su (1091-1132), which references the use of metal frames in movable type printing to print poems. The ceramic movable type was mentioned by Kublai Khan's councilor Yao Shu, who convinced his pupil Yang Gu to print language primers using this method.[3][22]

The claim that Bi Sheng's ceramic types were "fragile" and "not practical for large-scale printing" and "short lived"[23] were refuted by later experiments. Bao Shicheng (1775–1885) wrote that fired clay moveable type was "as hard and tough as horn"; experiments show that clay type, after being fired in a kiln, becomes hard and difficult to break, such that it remains intact after being dropped from a height of two metres onto a marble floor. The length of ceramic movable types in China was 1 to 2 centimetres, not 2 mm, thus hard as horn. But similar to metal type, ceramic type did not hold the water-based Chinese calligraphic ink well, and had an added disadvantage of uneven matching of the type which could sometimes result from the uneven changes in size of the type during the firing process.[24][25]

Ceramic movable type was used as late as 1844 in China from the Song dynasty through to the Qing dynasty.[26]: 22

Wooden movable type

[edit]

Bi Sheng (990–1051) of the Song dynasty also pioneered the use of wooden movable type around 1040 AD, as described by the Chinese scholar Shen Kuo (1031–1095). However, this technology was abandoned in favour of clay movable types due to the presence of wood grains and the unevenness of the wooden type after being soaked in ink.[19][27]

A number of books printed in Tangut script during the Western Xia (1038–1227) period are known, of which the Auspicious Tantra of All-Reaching Union, which was discovered in the ruins of Baisigou Square Pagoda in 1991 is believed to have been printed sometime during the reign of Emperor Renzong of Western Xia (1139–1193).[28] It is considered by many Chinese experts to be the earliest extant example of a book printed using wooden movable type.[29]

In 1298, Wang Zhen (王禎), a Yuan dynasty governmental official of Jingde County, Anhui Province, China, re-invented a method of making movable wooden types. He made more than 30,000 wooden movable types and printed 100 copies of Records of Jingde County (《旌德縣志》), a book of more than 60,000 Chinese characters. Soon afterwards, he summarized his invention in his book A method of making moveable wooden types for printing books. Although the wooden type was more durable under the mechanical rigors of handling, repeated printing wore down the character faces, and the types could only be replaced by carving new pieces. This system was later enhanced by pressing wooden blocks into sand and casting metal types from the depression in copper, bronze, iron or tin. This new method overcame many of the shortcomings of woodblock printing. Rather than manually carving an individual block to print a single page, movable type printing allowed for the quick assembly of a page of text. Furthermore, these new, more compact type fonts could be reused and stored.[19][20] Wang Zhen used two rotating circular tables as trays for laying out his type. The first table was separated into 24 trays in which each movable type was categorized based on a number corresponding with a rhyming pattern. The second table contained miscellaneous characters.[3]

The set of wafer-like metal stamp types could be assembled to form pages, inked, and page impressions taken from rubbings on cloth or paper.[20] In 1322, a Fenghua county officer Ma Chengde (馬称德) in Zhejiang, made 100,000 wooden movable types and printed the 43-volume Daxue Yanyi (《大學衍義》). Wooden movable types were used continually in China. Even as late as 1733, a 2300-volume Wuying Palace Collected Gems Edition (《武英殿聚珍版叢書》) was printed with 253,500 wooden movable types on order of the Qianlong Emperor, and completed in one year.[3]

Metal movable type

[edit]China

[edit]| Wooden movable-type printing of China | |

|---|---|

| Country | China |

| Reference | 00322 |

| Region | Asia and the Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2010 (5th session) |

| List | Need of Urgent Safeguarding |

At least 13 material finds in China indicate the invention of bronze movable type printing in China no later than the 12th century,[30] with the country producing large-scale bronze-plate-printed paper money and formal official documents issued by the Jin (1115–1234) and Southern Song (1127–1279) dynasties with embedded bronze metal types for anti-counterfeit markers. Such paper-money printing might date back to the 11th-century jiaozi of Northern Song (960–1127).[26]: 41–54

The typical example of this kind of bronze movable type embedded copper-block printing is a printed "check" of the Jin dynasty with two square holes for embedding two bronze movable-type characters, each selected from 1,000 different characters, such that each printed paper note has a different combination of markers. A copper-block printed note dated between 1215 and 1216 in the collection of Luo Zhenyu's Pictorial Paper Money of the Four Dynasties, 1914, shows two special characters—one called Ziliao, the other called Zihao—for the purpose of preventing counterfeiting; over the Ziliao there is a small character (輶) printed with movable copper type, while over the Zihao there is an empty square hole—apparently the associated copper metal type was lost. Another sample of Song dynasty money of the same period in the collection of the Shanghai Museum has two empty square holes above Ziliao as well as Zihou, due to the loss of the two copper movable types. Song dynasty bronze block embedded with bronze metal movable type printed paper money was issued on a large scale and remained in circulation for a long time.[31]

The 1298 book Zao Huozi Yinshufa (《造活字印書法》) by the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) official Wang Zhen mentions tin movable type, used probably since the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279), but this was largely experimental.[32] It was unsatisfactory due to its incompatibility with the inking process.[19]: 217 But by the late 15th century these concerns were resolved and bronze type was widely used in Chinese printing.[33]

During the Mongol Empire (1206–1405), printing using movable type spread from China to Central Asia.[clarification needed] The Uyghurs of Central Asia used movable type, their script type adopted from the Mongol language, some with Chinese words printed between the pages—strong evidence that the books were printed in China.[34]

During the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), Hua Sui in 1490 used bronze type in printing books.[19]: 212 In 1574 the massive 1000-volume encyclopedia Imperial Readings of the Taiping Era (《太平御覧》) was printed with bronze movable type.

In 1725 the Qing dynasty government made 250,000 bronze movable-type characters and printed 64 sets of the encyclopedic Complete Classics Collection of Ancient China (《古今圖書集成》). Each set consisted of 5,040 volumes, making a total of 322,560 volumes printed using movable type.[34]

Korea

[edit]

In 1234 the first books known to have been printed in metallic type set were published in Goryeo dynasty Korea. They form a set of ritual books, Sangjeong Gogeum Yemun, compiled by Ch'oe Yun-ŭi.[35][36]

While these books have not survived, Jikji, printed in Korea in 1377, is believed to be the world's oldest metallic movable type-printed book.[37] However, 2022 research suggests that a copy of the Song of Enlightenment with Commentaries by Buddhist Monk Nammyeong Cheon, printed 138 years before Jikji in 1239, may have been printed in metal type.[38] The Asian Reading Room of the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., displays examples of this metal type.[39] Commenting on the invention of metallic types by Koreans, French scholar Henri-Jean Martin described this as "[extremely similar] to Gutenberg's".[40] However, Korean movable metal type printing differed from European printing in the materials used for the type, punch, matrix, mould and in method of making an impression.[41]

The techniques for bronze casting, used at the time for making coins (as well as bells and statues) were adapted to making metal type. The Joseon dynasty scholar Seong Hyeon (성현, 成俔, 1439–1504) records the following description of the Korean font-casting process:

At first, one cuts letters in beech wood. One fills a trough level with fine sandy [clay] of the reed-growing seashore. Wood-cut letters are pressed into the sand, then the impressions become negative and form letters [moulds]. At this step, placing one trough together with another, one pours the molten bronze down into an opening. The fluid flows in, filling these negative moulds, one by one becoming type. Lastly, one scrapes and files off the irregularities, and piles them up to be arranged.[35]

A potential solution to the linguistic and cultural bottleneck that held back movable type in Korea for 200 years appeared in the early 15th century—a generation before Gutenberg would begin working on his own movable-type invention in Europe—when Sejong the Great devised a simplified alphabet of 24 characters (hangul) for use by the common people, which could have made the typecasting and compositing process more feasible. But Korea's cultural elite, "appalled at the idea of losing hanja, the badge of their elitism", stifled the adoption of the new alphabet.[20]

A "Confucian prohibition on the commercialization of printing" also obstructed the proliferation of movable type, restricting the distribution of books produced using the new method to the government.[42] The technique was restricted to use by the royal foundry for official state publications only, where the focus was on reprinting Chinese classics lost in 1126 when Korea's libraries and palaces had perished in a conflict between dynasties.[42]

Scholarly debate and speculation has occurred as to whether Eastern movable type spread to Europe between the late 14th century and early 15th centuries.[35][6]: 58–69 [43][5][44] For example, authoritative historians Frances Gies and Joseph Gies claimed that "The Asian priority of invention movable type is now firmly established, and that Chinese-Korean technique, or a report of it traveled westward is almost certain."[4] However, Joseph P. McDermott claimed that "No text indicates the presence or knowledge of any kind of Asian movable type or movable type imprint in Europe before 1450. The material evidence is even more conclusive."[44]

Europe

[edit]

Johannes Gutenberg of Mainz, Germany, invented the printing press, using a metal movable type system. Gutenberg, as a goldsmith, knew techniques of cutting punches for making coins from moulds. Between 1436 and 1450 he developed hardware and techniques for casting letters from matrices using a device called the hand mould.[6] Gutenberg's key invention and contribution to movable-type printing in Europe, the hand mould, was the first practical means of making cheap copies of letterpunches in the vast quantities needed to print complete books, making the movable-type printing process a viable enterprise.[citation needed]

Before Gutenberg, scribes copied books by hand on scrolls and paper, or print-makers printed texts from hand-carved wooden blocks. Either process took a long time; even a small book could take months to complete. Because carved letters or blocks were flimsy and the wood susceptible to ink, the blocks had a limited lifespan.[citation needed]

Gutenberg and his associates developed oil-based inks ideally suited to printing with a press on paper, and the first Latin typefaces. His method of casting type may have differed from the hand-mould used in subsequent decades. Detailed analysis of the type used in his 42-line Bible has revealed irregularities in some of the characters that cannot be attributed to ink spread or type wear under the pressure of the press. Scholars conjecture that the type pieces may have been cast from a series of matrices made with a series of individual stroke punches, producing many different versions of the same glyph.[47][need quotation to verify]

It has also been suggested[by whom?] that the method used by Gutenberg involved using a single punch to make a mould, but the mould was such that the process of taking the type out disturbed the casting, causing variants and anomalies, and that the punch-matrix system came into use possibly around the 1470s.[48]

This raises the possibility that the development of movable type in the West may have been progressive rather than a single innovation.[49]

Gutenberg's movable-type printing system spread rapidly across Europe, from the single Mainz printing press in 1457 to 110 presses by 1480, with 50 of them in Italy. Venice quickly became the centre of typographic and printing activity. Significant contributions came from Nicolas Jenson, Francesco Griffo, Aldus Manutius, and other printers of late 15th-century Europe. Gutenberg's movable type printing system offered a number of advantages over previous movable type techniques. The lead-antimony-tin alloy used by Gutenberg had half the melting temperature of bronze,[50][51] making it easier to cast the type and aided the use of reusable metal matrix moulds instead of the expendable sand and clay moulds. The use of antimony alloy increased hardness of the type compared to lead and tin[52] for improved durability of the type. The reusable metal matrix allowed a single experienced worker to produce 4,000 to 5,000 individual types a day,[53][54] while Wang Chen had artisans working two years to make 60,000 wooden types.[55]

Type-founding

[edit]

Stages

[edit]Type-founding as practised in Europe and the West consists of three stages:

- Punchcutting

- If the glyph design includes enclosed spaces (counters) then a counterpunch is made. The counter shapes are transferred in relief (cameo) onto the end of a rectangular bar of carbon steel using a specialized engraving tool called a graver. The finished counterpunch is hardened by heating and quenching (tempering), or exposure to a hot cyanide compound (case hardening). The counterpunch is then struck against the end of a similar rectangular steel bar—the letterpunch—to impress the counter shapes as recessed spaces (intaglio). The outer profile of the glyph is completed by scraping away with a graver the material outside the counter spaces, leaving only the stroke or lines of the glyph. Progress toward the finished design is checked by successive smoke proofs; temporary prints made from a thin coating of carbon deposited on the punch surface by a candle flame. The finished letter punch is finally hardened to withstand the rigours of reproduction by striking. One counterpunch and one letterpunch are produced for every letter or glyph making up a complete font.

- Matrix

- The letterpunch is used to strike a blank die of soft metal to make a negative letter mould, called a matrix.

- Casting

- The matrix is inserted into the bottom of a device called a hand mould. The mould is clamped shut and molten type metal alloy (consisting mostly of lead and tin, with a small amount of antimony for hardening) is poured into a cavity from the top. Antimony has the rare property of expanding as it cools, giving the casting sharp edges.[56] When the type metal has sufficiently cooled, the mould is unlocked and a rectangular block approximately 4 cm (1.6 in) long, called a sort, is extracted. Excess casting on the end of the sort, called the tang, is later removed to make the sort the precise height required for printing, known as "type height".

National traditions

[edit]The type-height varied in different countries. The Monotype Corporation Limited in London UK produced moulds in various heights:

- 0.918 inches (23.3 mm): United Kingdom, Canada, U.S.

- 0.928 inches (23.6 mm): France, Germany, Switzerland and most other European countries

- 0.933 inches (23.7 mm): Belgium height

- 0.9785 inches (24.85 mm): Dutch height

A Dutch printer's manual mentions a tiny difference between French and German Height:[57]

- 62.027 points Didot = 23.30 mm (0.917 in) = English height

- 62.666 points Didot = 23.55 mm (0.927 in) = French height

- 62.685 points Didot = 23.56 mm (0.928 in) = German height

- 66.047 points Didot = 24.85 mm (0.978 in) = Dutch Height

Tiny differences in type-height can cause quite bold images of characters.

At the end of the 19th century there were only two typefoundries left in the Netherlands: Johan Enschedé & Zonen, at Haarlem, and Lettergieterij Amsterdam, voorheen Tetterode. They both had their own type-height: Enschedé: 65 23/24 points Didot, and Amsterdam: 66 1/24 points Didot—enough difference to prevent a combined use of fonts from the two typefoundries: Enschede would be too light, or otherwise the Amsterdam-font would print rather bold. This was a way of keeping clients.[58]

In 1905 the Dutch governmental Algemeene Landsdrukkerij, later: "State-printery" (Staatsdrukkerij) decided during a reorganisation to use a standard type-height of 63 points Didot. Staatsdrukkerij-hoogte, actually Belgium-height, but this fact was not widely known[by whom?].

Typesetting

[edit]Modern, factory-produced movable type was available in the late 19th century. It was held in the printing shop in a job case, a drawer about 2 inches high, a yard wide, and about two feet deep, with many small compartments for the various letters and ligatures. The most popular and accepted of the job case designs in America was the California Job Case, which took its name from the Pacific coast location of the foundries that made the case popular.[59]

Traditionally, the capital letters were stored in a separate drawer or case that was located above the case that held the other letters; this is why capital letters are called "upper case" characters while the non-capitals are "lower case".[60]

Compartments also held spacers, which are blocks of blank type used to separate words and fill out a line of type, such as em and en quads (quadrats, or spaces. A quadrat is a block of type whose face is lower than the printing letters so that it does not itself print.). An em space was the width of a capital letter "M"—as wide as it was high—while an en space referred to a space half the width of its height (usually the dimensions for a capital "N").

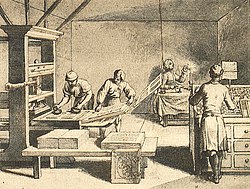

Individual letters are assembled into words and lines of text with the aid of a composing stick, and the whole assembly is tightly bound together to make up a page image called a forme, where all letter faces are exactly the same height to form a flat surface of type. The forme is mounted on a printing press, a thin coating of viscous ink is applied, and impressions are made on paper under great pressure in the press. "Sorts" is the term given to special characters not freely available in the typical type case, such as the "@" mark.

Metal type combined with other methods

[edit]

Sometimes, it is erroneously stated that printing with metal type replaced the earlier methods. In the industrial era printing methods would be chosen to suit the purpose. For example, when printing large scale letters in posters etc. the metal type would have proved too heavy and economically unviable. Thus, large scale type was made as carved wood blocks as well as ceramics plates.[61] Also in many cases where large scale text was required, it was simpler to hand the job to a sign painter than a printer. Images could be printed together with movable type if they were made as woodcuts or wood engravings as long as the blocks were made to the same type height. If intaglio methods, such as copper plates, were used for the images, then images and the text would have required separate print runs on different machines.

See also

[edit]- History of printing in East Asia

- History of Western typography

- Letterpress printing

- Odhecaton – the first sheet music printed with movable type

- Spread of European movable type printing

- Type foundry

- Typesetting

- Style guides

References

[edit]- ^ Needham, Joseph (1994). The Shorter Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 4. Cambridge University Press. p. 14. ISBN 9780521329958.

Bi Sheng... who first devised, about 1045, the art of printing with movable type

- ^ 吉星, 潘. 中國金屬活字印刷技術史. pp. 41–54.

- ^ a b c d Wilkinson 2012, p. 911.

- ^ a b Gies, Frances and Gies, Joseph (1994) Cathedral, Forge, and Waterwheel: Technology and Invention in the Middle Age, New York : HarperCollins, ISBN 0-06-016590-1, p. 241.

- ^ a b Thomas Franklin Carter, The Invention of Printing in China and its Spread Westward, The Ronald Press, NY 2nd ed. 1955, pp. 176–178

- ^ a b c von Polenz, Peter (1991). Deutsche Sprachgeschichte vom Spätmittelalter bis zur Gegenwart: I. Einführung, Grundbegriffe, Deutsch in der frühbürgerlichen Zeit (in German). New York/Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH.

- ^ He, Zhou (1994). "Diffusion of Movable Type in China and Europe: Why Were There Two Fates?". International Communication Gazette. 53 (3): 153–173. doi:10.1177/001654929405300301. S2CID 220900599.

- ^ Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15034-5.

- ^ Printing (publishing) at the Encyclopædia Britannica Retrieved

- ^ Eisenstein, Elizabeth L., The Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe, Cambridge University Press, 1983

- ^ Clair, Kate; Busic-Snyder, Cynthia (2012). A Typographic Workbook: A Primer to History, Techniques, and Artistry. John Wiley & Sons. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-118-39988-0.

- ^ Sass, Benjamin; Marzahn, Joachim (2010). Aramaic and Figural Stamp Impressions on Bricks of the Sixth Century B.C. from Babylon. Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 11, 20, 160. ISBN 978-3-447-06184-1.

"the latter has cuneiform signs that look as if made with a movable type, and impressions from Assur display the same phenomenon

- ^ Herbert E. Brekle, "Das typographische Prinzip", Gutenberg-Jahrbuch, Vol. 72 (1997), pp. 58–63 (60f.)

- ^ "The History Behind … Signet Rings". National Jeweler. Retrieved 2020-08-21.

- ^ Seibt, Werner (19 June 2016). "The Use of Monograms on Byzantine Seals in the Early Middle-Ages (6th to 9th Centuries)". Parekbolai. An Electronic Journal for Byzantine Literature. 6: 1–14. doi:10.26262/par.v6i0.5082. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ a b Wilkinson 2012, p. 909.

- ^ Tsien 1985, p. 6.

- ^ Jin 金, 柏东 (1 February 2004). "从白象塔《佛说观无量寿佛经》的发现说起活字印刷与温州——看我国现存最早的活字印刷品". 温州会刊. 20: 2. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin (1985). Paper and Printing. Needham, Joseph Science and Civilization in China. Vol. 5 part 1. Cambridge University Press. pp. 201–217. ISBN 978-0-521-08690-5.; also published in Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd., 1986.

- ^ a b c d Man, John (2002). The Gutenberg Revolution: The story of a genius that changed the world. London: Headline Book Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7472-4504-9. A detailed examination of Gutenberg's life and invention, interwoven with the underlying social and religious upheaval of Medieval Europe on the eve of the Renaissance.

- ^ Qi 2015, p. 214.

- ^ Qi 2015, p. 211-212.

- ^ Sohn, Pow-Key (1959). "Early Korean Printing". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 79 (2): 96–103. doi:10.2307/595851. JSTOR 595851.

- ^ Science and Civilization, volume 5 part 1, Joseph Needham, 1985, Cambridge University Press, page 221. ISBN 0 521 08690 6

- ^ The Book: A Cover-to-Cover Exploration of the Most Powerful Object of Our Time. W. W. Norton & Company. 22 August 2016. ISBN 9780393244809.

- ^ a b Pan Jixing, A history of movable metal type printing technique in China 2001

- ^ Shen, Kuo. Dream Pool Essays.

- ^ Zhang Yuzhen (張玉珍) (2003). "世界上現存最早的木活字印本—宁夏贺兰山方塔出土西夏文佛經《吉祥遍至口和本讀》介紹" [The world's oldest extant book printed with wooden movable type]. Library and Information (《書與情报》) (1). ISSN 1003-6938. Archived from the original on 2012-04-02.

- ^ Hou Jianmei (侯健美); Tong Shuquan (童曙泉) (20 December 2004). "《大夏寻踪》今展國博" ['In the Footsteps of the Great Xia' now exhibiting at the National Museum]. Beijing Daily (《北京日报》).

- ^ "韩国剽窃活字印刷发明权只是第一步". news.ifeng.com. Archived from the original on 2020-02-05. Retrieved 2014-05-23.

- ^ A History of Moveable Type Printing in China, by Pan Jixing, Professor of the Institute for History of Science, Academy of Science, Beijing, China, English Abstract, p. 273.

- ^ Wang Zhen (1298). Zao Huozi Yinshufa (《造活字印書法》).

近世又铸锡作字, 以铁条贯之 (rendering: In the modern times, there's melten Tin Movable type, and linked them with iron bar)

- ^ Tsien 1985, p. 211

- ^ a b Chinese Paper and Printing, A Cultural History, by Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin

- ^ a b c Thomas Christensen (2007). "Did East Asian Printing Traditions Influence the European Renaissance?". Arts of Asia Magazine (to appear). Archived from the original on 2019-08-11. Retrieved 2006-10-18.

- ^ Sohn, Pow-Key (Summer 1993). "Printing Since the 8th Century in Korea". Koreana. 7 (2): 4–9.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Twyman, Michael (1998). The British Library Guide to Printing: History and Techniques. London: The British Library. p. 21. ISBN 9780802081797.

- ^ Yoo, Woo Sik (2022-05-27). "The World's Oldest Book Printed by Movable Metal Type in Korea in 1239: The Song of Enlightenment". Heritage. 5 (2): 1089–1119. doi:10.3390/heritage5020059. ISSN 2571-9408.

- ^ World Treasures of the Library of Congress Archived 2016-08-29 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 26 December 2006.

- ^ Briggs, Asa and Burke, Peter (2002) A Social History of the Media: from Gutenberg to the Internet, Polity, Cambridge, pp. 15–23, 61–73.

- ^ Hee-Jae LEE (20–24 August 2006). "Korean Typography in 15th Century" (PDF). Seoul, Korea: 72ND IFLA GENERAL CONFERENCE AND COUNCIL. table on page 15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ a b Burke

- ^ Juan González de Mendoza (1585). Historia de las cosas más notables, ritos y costumbres del gran reyno de la China (in Spanish).

- ^ a b McDermott, Joseph P., ed. (2015). The Book Worlds of East Asia and Europe, 1450–1850: Connections and Comparisons. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-988-8208-08-1.

- ^ "Incunabula Short Title Catalogue". British Library. Archived from the original on 12 March 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ Buringh, Eltjo; van Zanden, Jan Luiten (2009). "Charting the 'Rise of the West': Manuscripts and Printed Books in Europe, A Long-Term Perspective from the Sixth through Eighteenth Centuries". The Journal of Economic History. 69 (2): 409–445. doi:10.1017/S0022050709000837. JSTOR 40263962. S2CID 154362112p. 417, table 2.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Agüera y Arcas, Blaise; Paul Needham (November 2002). "Computational analytical bibliography". Proceedings Bibliopolis Conference The future history of the book. The Hague (Netherlands): Koninklijke Bibliotheek.

- ^ "What Did Gutenberg Invent?—Discovery". BBC / Open University. 2006. Retrieved 2006-10-25.[dead link]

- ^ Adams, James L. (1993). Flying Buttresses, Entropy and O-Rings: the World of an Engineer. Harvard University Press. p. 80. ISBN 9780674306899.

There are printed materials from Holland that supposedly predate the Mainz shop. Early work on movable type in France was also under way.

- ^ "Machine Composition and Type Metal". Archived from the original on 2019-03-03. Retrieved 2019-03-07.

- ^ "Melting Points of Metals". Onlinemetals.com. Archived from the original on 2019-03-07. Retrieved 2019-03-07.

- ^ "Hardness of Lead Alloys". Archived from the original on 2019-02-26. Retrieved 2019-03-07.

- ^ Scientific American "Supplement" Volume 86 July 13, 1918 page 26, HATHI Trust Digital Library

- ^ Legros, Lucien Alphonse; Grant, John Cameron (1916) Typographical Printing-surfaces: The Technology and Mechanism of Their Production. Longmans, Green, and Co. p. 301

- ^ Childressm, Diana (2009) Johannes Gutenberg and the Printing Press. Twenty-First Century Books, Minneapolis, p. 49

- ^ "Answers.com page on antimony". McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Science and Technology. McGraw-Hill. 2005-01-01. Retrieved 2009-06-30.

- ^ Blankenstein A.H.G., Wetser Ad: Zetten, uitgebreide leerstof, deel 1, p. 26, Edecea, Hoorn, The Netherlands, 5th edition, (c.1952)

- ^ P.J.W. Oly, de grondslag van het bedrijf der lettergieterij Amsterdam, formerly N.Tetterode, edition: Stichting Lettergieten 1983, Westzaan, pp. 82–88

- ^ National Amateur Press Association Archived 2007-11-02 at the Wayback Machine, Monthly Bundle Sample, Campane 194, The California Typecase by Lewis A. Pryor (Edited)

- ^ Glossary of Typesetting Terms, by Richard Eckersley, Charles Ellerston, Richard Hendel, Page 18

- ^ Meggs, Philip B.; Purvis, Alston W. (2006). "Graphic Design and the Industrial Revolution". History of Graphic Design (4th ed.). Hoboken, N.J: Wiley. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-471-69902-6.

Further reading

[edit]- Nesbitt, Alexander (1957). The History and Technique of Lettering. Dover Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-486-40281-9. LCCN 57-13116.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) The Dover edition is an abridged and corrected republication of the work originally published in 1950 by Prentice-Hall, Inc. under the title Lettering: The History and Technique of Lettering as Design.- Moxon, Joseph (1683–84). Herbert Davies; Harry Carter (eds.). Mechanick Exercises on the Whole Art of Printing (1962 reprint ed.). New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-23617-X. LCCN 77-20468.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) The classic manual of hand-press technology.

- Moxon, Joseph (1683–84). Herbert Davies; Harry Carter (eds.). Mechanick Exercises on the Whole Art of Printing (1962 reprint ed.). New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-23617-X. LCCN 77-20468.

- Qi, Han (2015), Lecture 2 Printing, Springer

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2012), Chinese History: A New Manual, Harvard University Asia Center for the Harvard-Yenching Institute, ISBN 978-0-674-06715-8

External links

[edit]- International Printing Museum Web site

- Category:Typographical symbols – Articles related to typographical symbols

- Demonstration of Goryeo Period Korean Movable Type Printing

- Movable type of printing at Oxford Reference