Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Myelin

View on Wikipedia| Myelin | |

|---|---|

Structure of simplified neuron in the peripheral nervous system with myelinating Schwann cells | |

Neuron with myelinating oligodendrocyte and myelin sheath in the central nervous system | |

| Details | |

| System | Nervous system |

| Identifiers | |

| FMA | 62977 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Myelin (/ˈmaɪ.əlɪn/ MY-ə-lin) is a lipid-rich material that in most vertebrates surrounds the axons of neurons to insulate them and increase the rate at which electrical impulses (called action potentials) pass along the axon.[1][2] The myelinated axon can be likened to an electrical wire (the axon) with insulating material (myelin) around it. However, unlike the plastic covering on an electrical wire, myelin does not form a single long sheath over the entire length of the axon. Myelin ensheaths part of an axon known as an internodal segment, in multiple myelin layers of a tightly regulated internodal length.

The ensheathed segments are separated at regular short unmyelinated intervals, called nodes of Ranvier. Each node of Ranvier is around one micrometre long. Nodes of Ranvier enable a much faster rate of conduction known as saltatory conduction where the action potential recharges at each node to jump over to the next node, and so on till it reaches the axon terminal.[1][3][4][5] At the terminal the action potential provokes the release of neurotransmitters across the synapse, which bind to receptors on the post-synaptic cell such as another neuron, myocyte or secretory cell.

Myelin is made by specialized non-neuronal glial cells, that provide insulation, and nutritional and homeostatic support, along the length of the axon. In the central nervous system, myelination is formed by glial cells called oligodendrocytes, each of which sends out cellular extensions known as foot processes to myelinate multiple nearby axons. In the peripheral nervous system, myelin is formed by Schwann cells, which myelinate only a section of an axon. In the CNS, axons carry electrical signals from one nerve cell body to another.[6][7] The "insulating" function for myelin is essential for efficient motor function (i.e. movement such as walking), sensory function (e.g. sight, hearing, smell, the feeling of touch or pain) and cognition (e.g. acquiring and recalling knowledge), as demonstrated by the consequence of disorders that affect myelination, such as the genetically determined leukodystrophies;[8] the acquired inflammatory demyelinating disease, multiple sclerosis;[9] and the inflammatory demyelinating peripheral neuropathies.[10] Due to its high prevalence, multiple sclerosis, which specifically affects the central nervous system, is the best known demyelinating disorder.

History

[edit]Myelin was first described as white matter fibres in 1717 by Vesalius, and first named as myelin by Rudolf Virchow in 1854.[11] Over a century later, following the development of electron microscopy, its glial cell origin, and its ultrastructure became apparent.[11]

Composition

[edit]

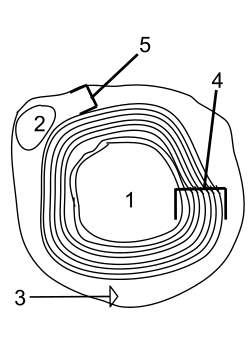

- Axon

- Nucleus of Schwann cell

- Schwann cell

- Myelin sheath

- Neurilemma

Myelin is found in all vertebrates except the jawless fish.[12][13] Myelin in the central nervous system (CNS) differs slightly in composition and configuration from myelin in the peripheral nervous system (PNS), but both perform the same functions of insulation and nutritional support. Being rich in lipid, myelin appears white, hence its earlier name of white matter of the CNS. Both CNS white matter tracts such as the corpus callosum, and corticospinal tract, and PNS nerves such as the sciatic nerve, and the auditory nerve, which also appear white, comprise thousands to millions of axons, largely aligned in parallel. In the corpus callosum there are more than 200 million axons.[14] Blood vessels provide the route for oxygen and energy substrates such as glucose to reach these fibre tracts, which also contain other cell types including astrocytes and microglia in the CNS and macrophages in the PNS.

In terms of total mass, myelin comprises approximately 40% water; the dry mass comprises between 60% and 75% lipid and between 15% and 25% protein. Protein content includes myelin basic protein (MBP),[15] which is abundant in the CNS where it plays a critical, non-redundant role in formation of compact myelin; myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG),[16] which is specific to the CNS; and proteolipid protein (PLP),[17] which is the most abundant protein in CNS myelin, but only a minor component of PNS myelin. In the PNS, myelin protein zero (MPZ or P0) has a similar role to that of PLP in the CNS in that it is involved in holding together the multiple concentric layers of glial cell membrane that constitute the myelin sheath. The primary lipid of myelin is a glycolipid called galactocerebroside. The intertwining hydrocarbon chains of sphingomyelin strengthen the myelin sheath. Cholesterol is an essential lipid component of myelin, without which myelin fails to form.[18]

Myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG) is a critical protein in the formation and maintenance of myelin sheaths. MAG is localized on the inner membrane of the myelin sheath and interacts with axonal membrane proteins to attach the myelin sheath to the axon.[19] Mutations to the MAG gene are implicated in demyelination diseases such as multiple sclerosis.[20]

Function

[edit]

The main purpose of myelin is to increase the speed at which electrical impulses (known as action potentials) propagate along the myelinated fiber. In unmyelinated fibers, action potentials travel as continuous waves, but, in myelinated fibers, they "hop" or propagate by saltatory conduction. The latter is markedly faster than the former, at least for axons over a certain diameter. Myelin decreases capacitance and increases electrical resistance across the axonal membrane (the axolemma). It has been suggested that myelin permits larger body size by maintaining agile communication between distant body parts.[12]

Myelinated fibers lack voltage-gated sodium channels along the myelinated internodes, exposing them only at the nodes of Ranvier. Here, they are highly abundant and densely packed.[21] Positively charged sodium ions can enter the axon through these voltage-gated channels, leading to depolarisation of the membrane potential at the node of Ranvier. The resting membrane potential is then rapidly restored due to positively charged potassium ions leaving the axon through potassium channels. The sodium ions inside the axon then diffuse rapidly through the axoplasm (axonal cytoplasm), to the adjacent myelinated internode and ultimately to the next (distal) node of Ranvier, triggering the opening of the voltage gated sodium channels and entry of sodium ions at this site. Although the sodium ions diffuse through the axoplasm rapidly, diffusion is decremental by nature, thus nodes of Ranvier have to be (relatively) closely spaced, to secure action potential propagation.[22] The action potential "recharges" at consecutive nodes of Ranvier as the axolemmal membrane potential depolarises to approximately +35 mV.[21] Along the myelinated internode, energy-dependent sodium/potassium pumps pump the sodium ions back out of the axon and potassium ions back into the axon to restore the balance of ions between the intracellular (inside the cell, i.e. axon in this case) and extracellular (outside the cell) fluids.

Whilst the role of myelin as an "axonal insulator" is well-established, other functions of myelinating cells are less well known or only recently established. The myelinating cell "sculpts" the underlying axon by promoting the phosphorylation of neurofilaments, thus increasing the diameter or thickness of the axon at the internodal regions; helps cluster molecules on the axolemma (such as voltage-gated sodium channels) at the node of Ranvier;[23] and modulates the transport of cytoskeletal structures and organelles such as mitochondria, along the axon.[24] In 2012, evidence came to light to support a role for the myelinating cell in "feeding" the axon.[25][26] In other words, the myelinating cell seems to act as a local "fueling station" for the axon, which uses a great deal of energy to restore the normal balance of ions between it and its environment,[27][28] following the generation of action potentials.

When a peripheral nerve fiber is severed, the myelin sheath provides a track along which regrowth can occur. However, the myelin layer does not ensure a perfect regeneration of the nerve fiber. Some regenerated nerve fibers do not find the correct muscle fibers, and some damaged motor neurons of the peripheral nervous system die without regrowth. Damage to the myelin sheath and nerve fiber is often associated with increased functional insufficiency.

Unmyelinated fibers and myelinated axons of the mammalian central nervous system do not regenerate.[29]

Development

[edit]The process of generating myelin is called myelination or myelinogenesis. In the CNS, oligodendrocyte progenitor cells differentiate into mature oligodendrocytes, which form myelin. In humans, myelination begins early in the third trimester which starts at around week 26 of gestational age.[30] The signal for myelination comes from the axon; axons larger than 1–2 μms become myelinated.[31] The length of the internode is determined by the size of the axonal diameter.[31] During infancy, myelination progresses rapidly, with increasing numbers of axons acquiring myelin sheaths. This corresponds with the development of cognitive and motor skills, including language comprehension, speech acquisition, crawling and walking. Myelination continues through adolescence and early adulthood and although largely complete at this time, myelin sheaths can be added in grey matter regions such as the cerebral cortex, throughout life.[32][33][34]

Not all axons are myelinated. For example, in the PNS, a large proportion of axons are unmyelinated. Instead, they are ensheathed by non-myelinating Schwann cells known as Remak SCs and arranged in Remak bundles.[35] In the CNS, non-myelinated axons (or intermittently myelinated axons, meaning axons with long non-myelinated regions between myelinated segments) intermingle with myelinated ones and are entwined, at least partially, by the processes of another type of glial cell the astrocyte.[36]

Clinical significance

[edit]Demyelination

[edit]Demyelination is the loss of the myelin sheath insulating the nerves, and is the hallmark of some neurodegenerative autoimmune diseases, including multiple sclerosis, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, neuromyelitis optica, transverse myelitis, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy, Guillain–Barré syndrome, central pontine myelinosis, inherited demyelinating diseases such as leukodystrophy, and Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease. People with pernicious anaemia can also develop nerve damage if the condition is not diagnosed quickly. Subacute combined degeneration of spinal cord secondary to pernicious anaemia can lead to slight peripheral nerve damage to severe damage to the central nervous system, affecting speech, balance, and cognitive awareness. When myelin degrades, conduction of signals along the nerve can be impaired or lost, and the nerve eventually withers.[clarification needed] A more serious case of myelin deterioration is called Canavan disease.

The immune system may play a role in demyelination associated with such diseases, including inflammation causing demyelination by overproduction of cytokines via upregulation of tumor necrosis factor[37] or interferon. MRI evidence that docosahexaenoic acid DHA ethyl ester improves myelination in generalized peroxisomal disorders.[38]

Symptoms

[edit]Demyelination results in diverse symptoms determined by the functions of the affected neurons. It disrupts signals between the brain and other parts of the body; symptoms differ from patient to patient, and have different presentations upon clinical observation and in laboratory studies.

Typical symptoms include blurriness in the central visual field that affects only one eye, may be accompanied by pain upon eye movement, double vision, loss of vision/hearing, odd sensation in legs, arms, chest, or face, such as tingling or numbness (neuropathy), weakness of arms or legs, cognitive disruption, including speech impairment and memory loss, heat sensitivity (symptoms worsen or reappear upon exposure to heat, such as a hot shower), loss of dexterity, difficulty coordinating movement or balance disorder, difficulty controlling bowel movements or urination, fatigue, and tinnitus.[39]

Myelin repair

[edit]Research to repair damaged myelin sheaths is ongoing. Techniques include surgically implanting oligodendrocyte precursor cells in the central nervous system and inducing myelin repair with certain antibodies. While results in mice have been encouraging (via stem cell transplantation), whether this technique can be effective in replacing myelin loss in humans is still unknown.[40] Cholinergic treatments, such as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs), may have beneficial effects on myelination, myelin repair, and myelin integrity. Increasing cholinergic stimulation also may act through subtle trophic effects on brain developmental processes and particularly on oligodendrocytes and the lifelong myelination process they support. Increasing oligodendrocyte cholinergic stimulation, AChEIs, and other cholinergic treatments, such as nicotine, possibly could promote myelination during development and myelin repair in older age.[41] Glycogen synthase kinase 3β inhibitors such as lithium chloride have been found to promote myelination in mice with damaged facial nerves.[42] Cholesterol is a necessary nutrient for the myelin sheath, along with vitamin B12.[43][44]

Dysmyelination

[edit]Dysmyelination is characterized by a defective structure and function of myelin sheaths; unlike demyelination, it does not produce lesions. Such defective sheaths often arise from genetic mutations affecting the biosynthesis and formation of myelin. The shiverer mouse represents one animal model of dysmyelination. Human diseases where dysmyelination has been implicated include leukodystrophies (Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease, Canavan disease, phenylketonuria) and schizophrenia.[45][46][47]

Invertebrates

[edit]Functionally equivalent myelin-like sheaths are found in several invertebrate taxa, including oligochaete annelids, and crustacean taxa such as penaeids, palaemonids, and calanoids. These myelin-like sheaths share several structural features with the sheaths found in vertebrates including multiplicity of membranes, condensation of membrane, and nodes.[12] However, the nodes in vertebrates are annular; i.e. they encircle the axon. In contrast, nodes found in the sheaths of invertebrates are either annular or fenestrated; i.e. they are restricted to "spots". It is found on the median giant fiber of the earthworm (Lumbricus terrestris L.), which is myelinated with openings on the dorsal side.[48] The fastest recorded conduction speed (across both vertebrates and invertebrates) is found in the ensheathed axons of the Kuruma shrimp, an invertebrate,[12] ranging between 90 and 200 m/s. This is obtained by neurons 10 μm in diameter and covered by a 10 μm thick myelin.[13] (cf. 100–120 m/s for the fastest myelinated vertebrate axon).

See also

[edit]- Myelin-associated glycoprotein

- Myelin incisure

- The Myelin Project, project to regenerate myelin

- Myelin Repair Foundation, a nonprofit medical research foundation for multiple sclerosis drug discovery.

- Myelinoid, an in vitro model for studying human myelination and white matter diseases

References

[edit]- ^ a b Bean, Bruce P. (June 2007). "The action potential in mammalian central neurons". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 8 (6): 451–65. doi:10.1038/nrn2148. ISSN 1471-0048. PMID 17514198. S2CID 205503852.

- ^ Morell, Pierre; Quarles, Richard H. (1999). "The Myelin Sheath". Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular and Medical Aspects. 6th edition. Lippincott-Raven. Retrieved 15 December 2023.

- ^ Carroll, SL (2017). "The Molecular and Morphologic Structures That Make Saltatory Conduction Possible in Peripheral Nerve". Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 76 (4): 255–57. doi:10.1093/jnen/nlx013. PMID 28340093.

- ^ Keizer J, Smith GD, Ponce-Dawson S, Pearson JE (August 1998). "Saltatory propagation of Ca2+ waves by Ca2+ sparks". Biophysical Journal. 75 (2): 595–600. Bibcode:1998BpJ....75..595K. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77550-2. PMC 1299735. PMID 9675162.

- ^ Dawson SP, Keizer J, Pearson JE (May 1999). "Fire-diffuse-fire model of dynamics of intracellular calcium waves". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (11): 6060–63. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.6060D. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.11.6060. PMC 26835. PMID 10339541.

- ^ Stassart, Ruth M.; Möbius, Wiebke; Nave, Klaus-Armin; Edgar, Julia M. (2018). "The Axon-Myelin Unit in Development and Degenerative Disease". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 12: 467. doi:10.3389/fnins.2018.00467. ISSN 1662-4548. PMC 6050401. PMID 30050403.

- ^ Stadelmann, Christine; Timmler, Sebastian; Barrantes-Freer, Alonso; Simons, Mikael (2019-07-01). "Myelin in the Central Nervous System: Structure, Function, and Pathology". Physiological Reviews. 99 (3): 1381–431. doi:10.1152/physrev.00031.2018. ISSN 1522-1210. PMID 31066630.

- ^ van der Knaap MS, Bugiani M (September 2017). "Leukodystrophies: a proposed classification system based on pathological changes and pathogenetic mechanisms". Acta Neuropathologica. 134 (3): 351–82. doi:10.1007/s00401-017-1739-1. PMC 5563342. PMID 28638987.

- ^ Compston A, Coles A (October 2008). "Multiple sclerosis". Lancet. 372 (9648): 1502–17. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61620-7. PMID 18970977. S2CID 195686659.

- ^ Lewis RA (October 2017). "Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy". Current Opinion in Neurology. 30 (5): 508–12. doi:10.1097/WCO.0000000000000481. PMID 28763304. S2CID 4961339.

- ^ a b Boullerne AI (September 2016). "The history of myelin". Experimental Neurology. 283 (Pt B): 431–45. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2016.06.005. PMC 5010938. PMID 27288241.

- ^ a b c d Hartline DK (May 2008). "What is myelin?". Neuron Glia Biology. 4 (2): 153–63. doi:10.1017/S1740925X09990263. PMID 19737435. S2CID 33164806.

- ^ a b Salzer JL, Zalc B (October 2016). "Myelination" (PDF). Current Biology. 26 (20): R971–75. Bibcode:2016CBio...26.R971S. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.07.074. PMID 27780071.

- ^ Luders E, Thompson PM, Toga AW (August 2010). "The development of the corpus callosum in the healthy human brain". J Neurosci. 30 (33): 10985–90. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5122-09.2010. PMC 3197828. PMID 20720105.

- ^ Steinman L (May 1996). "Multiple sclerosis: a coordinated immunological attack against myelin in the central nervous system". Cell. 85 (3): 299–302. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81107-1. PMID 8616884. S2CID 18442078.

- ^ Mallucci G, Peruzzotti-Jametti L, Bernstock JD, Pluchino S (April 2015). "The role of immune cells, glia and neurons in white and gray matter pathology in multiple sclerosis". Progress in Neurobiology. 127–128: 1–22. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.02.003. PMC 4578232. PMID 25802011.

- ^ Greer JM, Lees MB (March 2002). "Myelin proteolipid protein – the first 50 years". The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 34 (3): 211–15. doi:10.1016/S1357-2725(01)00136-4. PMID 11849988.

- ^ Saher G, Brügger B, Lappe-Siefke C, Möbius W, Tozawa R, Wehr MC, Wieland F, Ishibashi S, Nave KA (April 2005). "High cholesterol level is essential for myelin membrane growth". Nature Neuroscience. 8 (4): 468–75. doi:10.1038/nn1426. PMID 15793579. S2CID 9762771.

- ^ Lopez PH (2014). "Role of Myelin-Associated Glycoprotein (Siglec-4a) in the Nervous System". Glycobiology of the Nervous System. Advances in Neurobiology. Vol. 9. pp. 245–62. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-1154-7_11. ISBN 978-1-4939-1153-0. PMID 25151382.

- ^ Pronker MF, Lemstra S, Snijder J, Heck AJ, Thies-Weesie DM, Pasterkamp RJ, Janssen BJ (December 2016). "Structural basis of myelin-associated glycoprotein adhesion and signalling". Nature Communications. 7 13584. Bibcode:2016NatCo...713584P. doi:10.1038/ncomms13584. PMC 5150538. PMID 27922006.

- ^ a b Saladin KS (2012). Anatomy & physiology: the unity of form and function (6th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.[page needed]

- ^ Raine CS (1999). "Characteristics of Neuroglia". In Siegel GJ, Agranoff BW, Albers RW, Fisher SK, Uhler MD (eds.). Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular and Medical Aspects (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven.

- ^ Brivio V, Faivre-Sarrailh C, Peles E, Sherman DL, Brophy PJ (April 2017). "Assembly of CNS Nodes of Ranvier in Myelinated Nerves Is Promoted by the Axon Cytoskeleton". Current Biology. 27 (7): 1068–73. Bibcode:2017CBio...27.1068B. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.01.025. PMC 5387178. PMID 28318976.

- ^ Stassart RM, Möbius W, Nave KA, Edgar JM (2018). "The Axon-Myelin Unit in Development and Degenerative Disease". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 12: 467. doi:10.3389/fnins.2018.00467. PMC 6050401. PMID 30050403.

- ^ Fünfschilling U, Supplie LM, Mahad D, Boretius S, Saab AS, Edgar J, Brinkmann BG, Kassmann CM, Tzvetanova ID, Möbius W, Diaz F, Meijer D, Suter U, Hamprecht B, Sereda MW, Moraes CT, Frahm J, Goebbels S, Nave KA (April 2012). "Glycolytic oligodendrocytes maintain myelin and long-term axonal integrity". Nature. 485 (7399): 517–21. Bibcode:2012Natur.485..517F. doi:10.1038/nature11007. PMC 3613737. PMID 22622581.

- ^ Lee Y, Morrison BM, Li Y, Lengacher S, Farah MH, Hoffman PN, Liu Y, Tsingalia A, Jin L, Zhang PW, Pellerin L, Magistretti PJ, Rothstein JD (July 2012). "Oligodendroglia metabolically support axons and contribute to neurodegeneration". Nature. 487 (7408): 443–48. Bibcode:2012Natur.487..443L. doi:10.1038/nature11314. PMC 3408792. PMID 22801498.

- ^ Engl E, Attwell D (August 2015). "Non-signalling energy use in the brain". The Journal of Physiology. 593 (16): 3417–329. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2014.282517. PMC 4560575. PMID 25639777.

- ^ Attwell D, Laughlin SB (October 2001). "An energy budget for signaling in the grey matter of the brain". Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 21 (10): 1133–45. doi:10.1097/00004647-200110000-00001. PMID 11598490.

- ^ Huebner, Eric A.; Strittmatter, Stephen M. (2009). "Axon Regeneration in the Peripheral and Central Nervous Systems". Results and Problems in Cell Differentiation. 48: 339–51. doi:10.1007/400_2009_19. ISBN 978-3-642-03018-5. ISSN 0080-1844. PMC 2846285. PMID 19582408.

- ^ "Pediatric Neurologic Examination Videos & Descriptions: Developmental Anatomy". library.med.utah.edu. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

- ^ a b Schoenwolf, Gary C.; Bleyl, Steven B.; Brauer, Philip R.; Francis-West, P. H. (2015). Larsen's human embryology (Fifth ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone. p. 242. ISBN 978-1-4557-0684-6.

- ^ Swire M, French-Constant C (May 2018). "Seeing Is Believing: Myelin Dynamics in the Adult CNS". Neuron. 98 (4): 684–86. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2018.05.005. PMID 29772200.

- ^ Hill RA, Li AM, Grutzendler J (May 2018). "Lifelong cortical myelin plasticity and age-related degeneration in the live mammalian brain". Nature Neuroscience. 21 (5): 683–95. doi:10.1038/s41593-018-0120-6. PMC 5920745. PMID 29556031.

- ^ Hughes EG, Orthmann-Murphy JL, Langseth AJ, Bergles DE (May 2018). "Myelin remodeling through experience-dependent oligodendrogenesis in the adult somatosensory cortex". Nature Neuroscience. 21 (5): 696–706. doi:10.1038/s41593-018-0121-5. PMC 5920726. PMID 29556025.

- ^ Monk KR, Feltri ML, Taveggia C (August 2015). "New insights on Schwann cell development". Glia. 63 (8): 1376–93. doi:10.1002/glia.22852. PMC 4470834. PMID 25921593.

- ^ Wang, Doris D.; Bordey, Angélique (11 December 2008). "The astrocyte odyssey". Progress in Neurobiology. 86 (4): 342–67. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.09.015. PMC 2613184. PMID 18948166 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ^ Ledeen RW, Chakraborty G (March 1998). "Cytokines, signal transduction, and inflammatory demyelination: review and hypothesis". Neurochemical Research. 23 (3): 277–89. doi:10.1023/A:1022493013904. PMID 9482240. S2CID 7499162.

- ^ Martinez, Manuela; Vazquez, Elida (1 July 1998). "MRI evidence that docosahexaenoic acid ethyl ester improves myelination in generalized peroxisomal disorders". Neurology. 51 (1): 26–32. doi:10.1212/wnl.51.1.26. PMID 9674774. S2CID 21929640.

- ^ Mayo Clinic 2007 and University of Leicester Clinical Studies, 2014[full citation needed]

- ^ Windrem MS, Nunes MC, Rashbaum WK, Schwartz TH, Goodman RA, McKhann G, Roy NS, Goldman SA (January 2004). "Fetal and adult human oligodendrocyte progenitor cell isolates myelinate the congenitally dysmyelinated brain". Nature Medicine. 10 (1): 93–97. doi:10.1038/nm974. PMID 14702638. S2CID 34822879.

- "Stem Cell Therapy Replaces Missing Myelin In Mouse Brains". FuturePundit. January 20, 2004. Archived from the original on June 14, 2011. Retrieved March 22, 2007.

- ^ Bartzokis G (August 2007). "Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors may improve myelin integrity". Biological Psychiatry. 62 (4): 294–301. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.08.020. PMID 17070782. S2CID 2130691.

- ^ Makoukji J, Belle M, Meffre D, Stassart R, Grenier J, Shackleford G, Fledrich R, Fonte C, Branchu J, Goulard M, de Waele C, Charbonnier F, Sereda MW, Baulieu EE, Schumacher M, Bernard S, Massaad C (March 2012). "Lithium enhances remyelination of peripheral nerves". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (10): 3973–78. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109.3973M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1121367109. PMC 3309729. PMID 22355115.

- ^ Petrov AM, Kasimov MR, Zefirov AL (2016). "Brain Cholesterol Metabolism and Its Defects: Linkage to Neurodegenerative Diseases and Synaptic Dysfunction". Acta Naturae. 8 (1): 58–73. doi:10.32607/20758251-2016-8-1-58-73. PMC 4837572. PMID 27099785.

- ^ Miller A, Korem M, Almog R, Galboiz Y (June 2005). "Vitamin B12, demyelination, remyelination and repair in multiple sclerosis". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 233 (1–2): 93–97. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2005.03.009. PMID 15896807. S2CID 6269094.

- ^ Krämer-Albers EM, Gehrig-Burger K, Thiele C, Trotter J, Nave KA (November 2006). "Perturbed interactions of mutant proteolipid protein/DM20 with cholesterol and lipid rafts in oligodendroglia: implications for dysmyelination in spastic paraplegia". The Journal of Neuroscience. 26 (45): 11743–52. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3581-06.2006. PMC 6674790. PMID 17093095.

- ^ Matalon R, Michals-Matalon K, Surendran S, Tyring SK (2006). "Canavan disease: studies on the knockout mouse". N-Acetylaspartate. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 576. pp. 77–93, discussion 361–63. doi:10.1007/0-387-30172-0_6. ISBN 978-0-387-30171-6. PMID 16802706.

- ^ Tkachev D, Mimmack ML, Huffaker SJ, Ryan M, Bahn S (August 2007). "Further evidence for altered myelin biosynthesis and glutamatergic dysfunction in schizophrenia". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 10 (4): 557–63. doi:10.1017/S1461145706007334. PMID 17291371.

- ^ Günther, Jorge (1976-08-15). "Impulse conduction in the myelinated giant fibers of the earthworm. Structure and function of the dorsal nodes in the median giant fiber". Journal of Comparative Neurology. 168 (4): 505–531. doi:10.1002/cne.901680405. ISSN 0021-9967.

Further reading

[edit]- Fields, R. Douglas, "The Brain Learns in Unexpected Ways: Neuroscientists have discovered a set of unfamiliar cellular mechanisms for making fresh memories", Scientific American, vol. 322, no. 3 (March 2020), pp. 74–79. "Myelin, long considered inert insulation on axons, is now seen as making a contribution to learning by controlling the speed at which signals travel along neural wiring." (p. 79.)

- Swire M, Ffrench-Constant C (May 2018). "Seeing Is Believing: Myelin Dynamics in the Adult CNS". Neuron. 98 (4): 684–86. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2018.05.005. PMID 29772200.

- Waxman SG (October 1977). "Conduction in myelinated, unmyelinated, and demyelinated fibers". Archives of Neurology. 34 (10): 585–89. doi:10.1001/archneur.1977.00500220019003. PMID 907529.