Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

New Persian

View on Wikipedia| New Persian | |

|---|---|

| فارسی نو, پارسی نو | |

Fārsi written in Persian calligraphy (Nastaʿlīq) | |

| Native to |

|

Native speakers | 70 million[7] (110 million total speakers)[6] |

Early forms | |

| Persian alphabet (Iran and Afghanistan) Tajik alphabet (Tajikistan) Hebrew alphabet Persian Braille | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

|

| Regulated by |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | fa |

| ISO 639-2 | per (B) fas (T) |

| ISO 639-3 | fas |

| Glottolog | fars1254 |

| Linguasphere | 58-AAC (Wider Persian) > 58-AAC-c (Central Persian) |

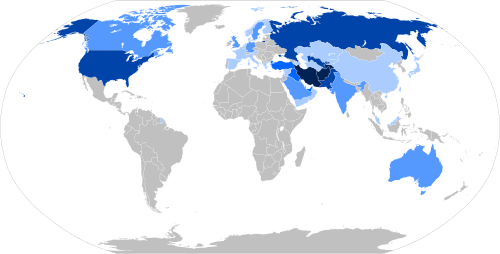

Areas with significant numbers of people whose first language is Persian (including dialects) | |

Persian Linguasphere. Legend Official language

More than 1,000,000 speakers

Between 500,000 – 1,000,000 speakers

Between 100,000 – 500,000 speakers

Between 25,000 – 100,000 speakers

Fewer than 25,000 speakers / none | |

New Persian (Persian: فارسی نو, romanized: fārsī-ye now), also known as Modern Persian (فارسی نوین) is the current stage of the Persian language spoken since the 8th to 9th centuries until now in Greater Iran and surroundings. It is conventionally divided into three stages: Early New Persian (8th/9th centuries), Classical Persian (10th–18th centuries), and Contemporary Persian (19th century to present).

Dari is a name given to the New Persian language since the 10th century, widely used in Arabic (see Istakhri, al-Maqdisi and ibn Hawqal) and Persian texts.[10] Since 1964, Dari has been the official name in Afghanistan for the Persian spoken there.

Classification

[edit]New Persian is a member of the Western Iranian group of the Iranian languages, which make up a branch of the Indo-European languages in their Indo-Iranian subdivision.[11]

| Indo-Iranian (Aryan) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proto Indo-Iranian | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Indo-Aryan | Proto-Iranian | Nuristani | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Iranian Languages (Irani-Aryan) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Old Iranian | Middle Iranian | New Iranian (Neo-Iranian) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Old Persian | Western | Eastern | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Southwestern | Northwestern | Soghdian, Scythian, Khwarezmian, Bactrian | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Middle Persian (Pārsīg/Sassanian Pahlavi) | Median (Medic), Parthian (Pahlavani/Arsacid Pahlavi) | Kurdish, Old Azeri, Tati, Balochi, Talyshi, Zaza, Mazanderani, Gilaki | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Achomi (Larestani) | Luri | New Persian (Farsi) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Iranian Farsi (Western) | Tajiki Farsi | Dari Farsi (Eastern) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tehrani, Isfahani, Etc... | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Western Iranian languages themselves are divided into two subgroups: Southwestern Iranian languages, of which Persian is the most widely spoken, and Northwestern Iranian languages, of which Kurdish is the most widely spoken.[11]

Etymology

[edit]"New Persian" is the name given to the final stage of development of Persian language. The term Persian is an English derivation of Latin Persiānus, the adjectival form of Persia, itself deriving from Greek Persís (Περσίς),[12] a Hellenized form of Old Persian Pārsa (𐎱𐎠𐎼𐎿),[13] which means "Persia" (a region in southwestern Iran corresponding to modern-day Fars province). According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the term Persian as a language name is first attested in English in the mid-16th century.[14]

There are different opinions about the origin of the word Dari. The majority of scholars believes Dari refers to the Persian word dar or darbār "court" (دربار) as it was the formal language of the Sasanian dynasty.[15] The original meaning of the word dari is given in a notice attributed to Ibn al-Muqaffaʿ (cited by Ibn al-Nadim in Al-Fehrest).[16] According to him, "Pārsī was the language spoken by priests, scholars, and the like; it is the language of Fars." This language refers to the Middle Persian.[15] As for Dari, he says, "it is the language of the cities of Madā'en; it is spoken by those who are at the king's court. [Its name] is connected with presence at court. Among the languages of the people of Khorasan and the east, the language of the people of Balkh is predominant."[15]

History

[edit]New Persian is conventionally divided into three stages:

- Early New Persian (8th/9th centuries)

- Classical Persian (10th–18th centuries)

- Contemporary Persian (19th century to present)

Early New Persian remains largely intelligible to speakers of Contemporary Persian, as the morphology and, to a lesser extent, the lexicon of the language have remained relatively stable.[17]

Early New Persian

[edit]

New Persian texts written in the Arabic script first appear in the 9th-century.[18] The language is a direct descendant of Middle Persian, the official, religious and literary language of the Sasanian Empire (224–651).[19] However, it is not descended from the literary form of Middle Persian (known as pārsīk, commonly called Pahlavi), which was spoken by the people of Fars and used in Zoroastrian religious writings. Instead, it is descended from the dialect spoken by the court of the Sasanian capital Ctesiphon and the northeastern Iranian region of Khorasan, known as Dari.[18][20] Khorasan, which was the homeland of the Parthians, was Persianized under the Sasanians. Dari Persian thus supplanted the Parthian language, which by the end of the Sasanian era had fallen out of use.[18] New Persian has incorporated many foreign words, including from eastern northern and northern Iranian languages such as Sogdian and especially Parthian.[21]

The mastery of the newer speech having now been transformed from Middle into New Persian was already complete by the era of the three princely dynasties of Iranian origin, the Tahirid dynasty (820–872), Saffarid dynasty (860–903) and Samanid Empire (874–999), and could develop only in range and power of expression.[22] Abbas of Merv is mentioned as being the earliest minstrel to chant verse in the newer Persian tongue and after him the poems of Hanzala Badghisi were among the most famous between the Persian-speakers of the time.[23]

The first poems of the Persian language, a language historically called Dari, emerged in Afghanistan.[24] The first significant Persian poet was Rudaki. He flourished in the 10th century, when the Samanids were at the height of their power. His reputation as a court poet and as an accomplished musician and singer has survived, although little of his poetry has been preserved. Among his lost works are versified fables collected in the Kalila wa Dimna.[25]

The language spread geographically from the 11th century on and was the medium through which among others, Central Asian Turks became familiar with Islam and urban culture. New Persian was widely used as a trans-regional lingua franca, a task for which it was particularly suitable due to its relatively simple morphological structure and this situation persisted until at least the 19th century.[26] In the late Middle Ages, new Islamic literary languages were created on the Persian model: Ottoman Turkish, Chagatai, Dobhashi and Urdu, which are regarded as "structural daughter languages" of Persian.[26]

Classical Persian

[edit]"Classical Persian" loosely refers to the standardized language of medieval Persia used in literature and poetry. This is the language of the 10th to 12th centuries, which continued to be used as literary language and lingua franca under the "Persianized" Turko-Mongol dynasties during the 12th to 15th centuries, and under restored Persian rule during the 16th to 19th centuries.[27]

Persian during this time served as lingua franca of Greater Persia and of much of the Indian subcontinent. It was also the official and cultural language of many Islamic dynasties, including the Samanids, Buyids, Tahirids, Ziyarids, the Mughal Empire, Timurids, Ghaznavids, Karakhanids, Seljuqs, Khwarazmians, the Sultanate of Rum, Delhi Sultanate, the Shirvanshahs, Safavids, Afsharids, Zands, Qajars, Khanate of Bukhara, Khanate of Kokand, Emirate of Bukhara, Khanate of Khiva, Ottomans and also many Mughal successors such as the Nizam of Hyderabad. Persian was the only non-European language known and used by Marco Polo at the Court of Kublai Khan and in his journeys through China.[28]

Contemporary Persian

[edit]

- Qajar dynasty

In the 19th century, under the Qajar dynasty, the dialect that is spoken in Tehran rose to prominence. There was still substantial Arabic vocabulary, but many of these words have been integrated into Persian phonology and grammar. In addition, under the Qajar rule numerous Russian, French, and English terms entered the Persian language, especially vocabulary related to technology.

The first official attentions to the necessity of protecting the Persian language against foreign words, and to the standardization of Persian orthography, were under the reign of Naser ed Din Shah of the Qajar dynasty in 1871.[citation needed] After Naser ed Din Shah, Mozaffar ed Din Shah ordered the establishment of the first Persian association in 1903.[29] This association officially declared that it used Persian and Arabic as acceptable sources for coining words. The ultimate goal was to prevent books from being printed with wrong use of words. According to the executive guarantee of this association, the government was responsible for wrongfully printed books. Words coined by this association, such as rāh-āhan (راهآهن) for "railway", were printed in Soltani Newspaper; but the association was eventually closed due to inattention.[citation needed]

A scientific association was founded in 1911, resulting in a dictionary called Words of Scientific Association (لغت انجمن علمی), which was completed in the future and renamed Katouzian Dictionary (فرهنگ کاتوزیان).[30]

- Pahlavi dynasty

The first academy for the Persian language was founded on 20 May 1935, under the name Academy of Iran. It was established by the initiative of Reza Shah Pahlavi, and mainly by Hekmat e Shirazi and Mohammad Ali Foroughi, all prominent names in the nationalist movement of the time. The academy was a key institution in the struggle to re-build Iran as a nation-state after the collapse of the Qajar dynasty. During the 1930s and 1940s, the academy led massive campaigns to replace the many Arabic, Russian, French, and Greek loanwords whose widespread use in Persian during the centuries preceding the foundation of the Pahlavi dynasty had created a literary language considerably different from the spoken Persian of the time. This became the basis of what is now known as "Contemporary Standard Persian".

Varieties

[edit]There are three standard varieties of modern Persian:

- Western Persian (Persian, Western Persian, or Farsi) is spoken in Iran, and by minorities in Iraq and the Persian Gulf states.

- Eastern Persian (Dari Persian, Afghan Persian, or Dari) is spoken in Afghanistan.

- Tajiki (Tajik Persian) is spoken in Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. It is written in the Cyrillic script.

All these three varieties are based on the classic Persian literature and its literary tradition. There are also several local dialects from Iran, Afghanistan and Tajikistan which slightly differ from the standard Persian. The Hazaragi dialect (in Central Afghanistan and Pakistan), Herati (in Western Afghanistan), Darwazi (in Afghanistan and Tajikistan), Basseri (in Southern Iran), and the Tehrani accent (in Iran, the basis of standard Iranian Persian) are examples of these dialects. Persian-speaking peoples of Iran, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan can understand one another with a relatively high degree of mutual intelligibility.[31] Nevertheless, the Encyclopædia Iranica notes that the Iranian, Afghan and Tajiki varieties comprise distinct branches of the Persian language, and within each branch a wide variety of local dialects exist.[32]

The following are some languages closely related to Persian, or in some cases are considered dialects:

- Luri (or Lori), spoken mainly in the southwestern Iranian provinces of Lorestan, Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad, Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari some western parts of Fars province and some parts of Khuzestan province.

- Tat, spoken in parts of Azerbaijan, Russia, and Transcaucasia. It is classified as a variety of Persian.[33][34][35][36][37] (This dialect is not to be confused with the Tati language of northwestern Iran, which is a member of a different branch of the Iranian languages.)

- Judeo-Tat. Part of the Tat-Persian continuum, spoken in Azerbaijan, Russia, as well as by immigrant communities in Israel and New York.

Standard Persian

[edit]Standard Persian is the standard variety of Persian that is the official language of the Iran[8] and Tajikistan[38] and one of the two official languages of Afghanistan.[39] It is a set of spoken and written formal varieties used by the educated persophones of several nations around the world.[40]

As Persian is a pluricentric language, Standard Persian encompasses various linguistic norms (consisting of prescribed usage). Standard Persian practically has three standard varieties with official status in Iran, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan. The standard forms of the three are based on the Tehrani, Kabuli, and Bukharan varieties, respectively.[41][42]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Samadi, Habibeh; Nick Perkins (2012). Martin Ball; David Crystal; Paul Fletcher (eds.). Assessing Grammar: The Languages of Lars. Multilingual Matters. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-84769-637-3.

- ^ "IRAQ". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ "Tajiks in Turkmenistan". People Groups.

- ^ Pilkington, Hilary; Yemelianova, Galina (2004). Islam in Post-Soviet Russia. Taylor & Francis. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-203-21769-6.

Among other indigenous peoples of Iranian origin were the Tats, the Talishes and the Kurds.

- ^ Mastyugina, Tatiana; Perepelkin, Lev (1996). An Ethnic History of Russia: Pre-revolutionary Times to the Present. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-313-29315-3.

The Iranian Peoples (Ossetians, Tajiks, Tats, Mountain Judaists)

- ^ a b Windfuhr, Gernot: The Iranian Languages, Routledge 2009, p. 418.

- ^ "Persian | Department of Asian Studies". Retrieved 2 January 2019.

There are numerous reasons to study Persian: for one thing, Persian is an important language of the Middle East and Central Asia, spoken by approximately 70 million native speakers and roughly 110 million people worldwide.

- ^ a b Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran: Chapter II, Article 15: "The official language and script of Iran, the lingua franca of its people, is Persian. Official documents, correspondence, and texts, as well as text-books, must be in this language and script. However, the use of regional and tribal languages in the press and mass media, as well as for teaching of their literature in schools, is allowed in addition to Persian."

- ^ Constitution of the Republic of Dagestan: Chapter I, Article 11: "The state languages of the Republic of Dagestan are Russian and the languages of the peoples of Dagestan."

- ^ "DARĪ – Encyclopaedia Iranica".

- ^ a b Windfuhr, Gernot (1987). Comrie, Berard (ed.). The World's Major Languages. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 523–546. ISBN 978-0-19-506511-4.

- ^ Περσίς. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Persia". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary online, s.v. "Persian", draft revision June 2007.

- ^ a b c Lazard, G. "Darī – The New Persian Literary Language", in Encyclopædia Iranica, Online Edition 2006.

- ^ Ebn al-Nadim, ed. Tajaddod, p. 15; Khjwārazmī, Mafātīh al-olum, pp. 116–17; Hamza Esfahānī, pp. 67–68; Yāqūt, Boldān IV, p. 846

- ^ Jeremias, Eva M. (2004). "Iran, iii. (f). New Persian". Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. 12 (New Edition, Supplement ed.). p. 432. ISBN 90-04-13974-5.

- ^ a b c Paul 2000.

- ^ Lazard 1975, p. 596.

- ^ Perry 2011.

- ^ Lazard 1975, p. 597.

- ^ Jackson, A. V. Williams. 1920. Early Persian poetry, from the beginnings down to the time of Firdausi. New York: The Macmillan Company. pp.17–19. (in Public Domain)

- ^ Jackson, A. V. Williams.pp.17–19.

- ^ Adamec, Ludwig W. (2011). Historical Dictionary of Afghanistan (4th Revised ed.). Scarecrow. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-8108-7815-0.

- ^ de Bruijn, J.T.P. (14 December 2015). "Persian literature". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ a b Johanson, Lars, and Christiane Bulut. 2006. Turkic-Iranian contact areas: historical and linguistic aspects Archived 2011-10-02 at the Wayback Machine. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- ^ according to iranchamber.com "the language (ninth to thirteenth centuries), preserved in the literature of the Empire, is known as Classical Persian, due to the eminence and distinction of poets such as Roudaki, Ferdowsi, and Khayyam. During this period, Persian was adopted as the lingua franca of the eastern Islamic nations. Extensive contact with Arabic led to a large influx of Arab vocabulary. In fact, a writer of Classical Persian had at one's disposal the entire Arabic lexicon and could use Arab terms freely either for literary effect or to display erudition. Classical Persian remained essentially unchanged until the nineteenth century, when the dialect of Teheran rose in prominence, having been chosen as the capital of Persia by the Qajar Dynasty in 1787. This Modern Persian dialect became the basis of what is now called Contemporary Standard Persian. Although it still contains a large number of Arab terms, most borrowings have been nativized, with a much lower percentage of Arabic words in colloquial forms of the language."

- ^ Boyle, John Andrew (1974). "Some Thoughts on the Sources for the Il-Khanid Period of Persian History". Iran. 12: 185–188. doi:10.2307/4300510. JSTOR 4300510.

- ^ Jazayeri, M. A. (15 December 1999). "Farhangestān". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ^ نگار داوری اردکانی (1389). برنامهریزی زبان فارسی. روایت فتح. p. 33. ISBN 978-600-6128-05-4.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Beeman, William. "Persian, Dari and Tajik" (PDF). Brown University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- ^ Aliev, Bahriddin; Okawa, Aya (2010). "TAJIK iii. COLLOQUIAL TAJIKI IN COMPARISON WITH PERSIAN OF IRAN". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ^ Gernot Windfuhr, "Persian Grammar: history and state of its study", Walter de Gruyter, 1979. pg 4:""Tat- Persian spoken in the East Caucasus""

- ^ V. Minorsky, "Tat" in M. Th. Houtsma et al., eds., The Encyclopædia of Islam: A Dictionary of the Geography, Ethnography and Biography of the Muhammadan Peoples, 4 vols. and Suppl., Leiden: Late E.J. Brill and London: Luzac, 1913–38.

- ^ V. Minorsky, "Tat" in M. Th. Houtsma et al., eds., The Encyclopædia of Islam: A Dictionary of the Geography, Ethnography and Biography of the Muhammadan Peoples, 4 vols. and Suppl., Leiden: Late E.J. Brill and London: Luzac, 1913–38. Excerpt: "Like most Persian dialects, Tati is not very regular in its characteristic features"

- ^ Kerslake, C. (January 2010). "Turkic-Iranian Contact Areas: Historical and Linguistic Aspects * Edited by LARS JOHANSON and CHRISTIANE BULUT". Journal of Islamic Studies. 21 (1): 147–151. doi:10.1093/jis/etp078.

It is a comparison of the verbal systems of three varieties of Persian—standard Persian, Tat, and Tajik—in terms of the 'innovations' that the latter two have developed for expressing finer differentiations of tense, aspect and modality…

- ^ Borjian, Habib (2006). "Tabari Language Materials from Il'ya Berezin's Recherches sur les dialectes persans". Iran and the Caucasus. 10 (2): 243–258. doi:10.1163/157338406780346005.

It embraces Gilani, Talysh, Tabari, Kurdish, Gabri, and the Tati Persian of the Caucasus, all but the last belonging to the north-western group of Iranian language.

- ^ "Tajikistan Drops Russian As Official Language". RFE/RL – Rferl.org. 7 October 2009. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ "What Languages are Spoken in Afghanistan?". 2004. Retrieved June 13, 2012.

Pashto and Dari are the official languages of the state. are – in addition to Pashto and Dari – the third official language in areas where the majority speaks them

- ^ "Standard Persian" (PDF). sid.ir. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ "History of Tehrani accent". Iranian students news agency. 10 July 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ Ido, Shinji (April 2014). "Bukharan Tajik". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 44 (1): 87–102. doi:10.1017/S002510031300011X.

Sources

[edit]- Bosworth, C.E. & Crowe, Yolande (1995). "Sāmānids". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume VIII: Ned–Sam. Leiden: E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-09834-3.

- Bosworth, C. E. (1998). "Esmāʿīl, b. Aḥmad b. Asad Sāmānī, Abū Ebrāhīm". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. VIII/6: Eršād al-zerāʿa–Eʿteżād-al-Salṭana. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 636–637. ISBN 978-1-56859-055-4.

- Crone, Patricia (2012). The Nativist Prophets of Early Islamic Iran: Rural Revolt and Local Zoroastrianism. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107642386.

- de Blois, Francois (2004). Persian Literature – A Bio-Bibliographical Survey: Poetry of the Pre-Mongol Period (Volume V). Routledge. ISBN 978-0947593476.

- de Bruijn, J.T.P. (1978). "Iran, vii.—Literature". In van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Bosworth, C. E. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume IV: Iran–Kha. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 52–75. OCLC 758278456.

- Frye, R. N. (2004). "Iran v. Peoples of Iran (1) A General Survey". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. XIII/3: Iran II. Iranian history–Iran V. Peoples of Iran. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 321–326. ISBN 978-0-933273-89-4.

- Jeremiás, Éva (2011). "Iran". In Edzard, Lutz; de Jong, Rudolf (eds.). Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Brill Online.

- Lazard, G. (1975). "The Rise of the New Persian Language". In Frye, Richard N. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 4: From the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 595–633. ISBN 0-521-20093-8.

- Lazard, G. (1994). "Darī". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. VII/1: Dārā(b)–Dastūr al-Afāżel. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 34–35. ISBN 978-1-56859-019-6.

- Paul, Ludwig (2000). "Persian Language i. Early New Persian". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition. New York.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Perry, John R. (2011). "Persian". In Edzard, Lutz; de Jong, Rudolf (eds.). Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Brill Online.

- Spuler, Bertold (2003). Persian Historiography and Geography: Bertold Spuler on Major Works Produced in Iran, the Caucasus, Central Asia, India, and Early Ottoman Turkey. Pustaka Nasional Pte Ltd. ISBN 978-9971-77-488-2.

- Rypka, Jan (1968). Jahn, Karl (ed.). History of Iranian Literature. doi:10.1007/978-94-010-3479-1. ISBN 978-94-010-3481-4.

External links

[edit]- Academy of Persian Language and Literature official website (in Persian)

- Assembly for the Expansion of the Persian Language official website (in Persian)

- Persian language Resources (in Persian)

New Persian

View on GrokipediaLinguistic Classification and Origins

Indo-Iranian Genealogy

New Persian is classified as a Southwestern Iranian language, belonging to the Western Iranian subgroup within the Iranian branch of the Indo-Iranian languages, which constitutes a major division of the Indo-European language family.[6] The Iranian languages as a whole trace their origins to Proto-Iranian, which emerged from Proto-Indo-Iranian in Central Asia during the late third to early second millennium BCE, sharing close genetic ties with the Indo-Aryan languages but diverging through distinct phonological and morphological developments, such as the Iranian satemization of Indo-European stops.[6] This Proto-Iranian stage gave rise to both Western and Eastern Iranian divisions, with Western Iranian further subdividing into Northwestern (e.g., Median, Parthian, and modern Kurdish) and Southwestern groups, the latter encompassing Persian and closely related languages like Luri and Bakhtiari.[7] The Southwestern Iranian lineage specifically leads from Old Persian, attested in cuneiform inscriptions of the Achaemenid Empire from the sixth to fourth centuries BCE, characterized by an inflected grammar with three genders, six cases, and a vocabulary reflecting imperial administration across a vast territory.[7] Old Persian evolved into Middle Persian (also known as Pahlavi), the administrative and literary language of the Sasanian Empire from roughly the third century BCE to the ninth century CE, which simplified the grammatical system by eliminating cases and genders while adopting the Pahlavi script derived from Aramaic.[8] Middle Persian served as the immediate ancestor of New Persian, retaining core lexical and syntactic features but undergoing significant analytic restructuring and vocabulary expansion, particularly after the Arab conquest in the seventh century CE, which introduced Arabic loanwords without fundamentally altering its Iranian substrate.[6][7] New Persian proper emerged around the ninth century CE in the Fārs province of southwestern Iran, initially as Early New Persian or Dārī, marking the transition to a fully analytic structure with periphrastic verb forms and the adoption of a modified Arabic script, while preserving phonological traits like the retention of initial /w-/ and /h-/ from earlier stages that were lost in many other Iranian languages.[8] This evolution reflects continuity in the Southwestern branch, distinguishing it from Northwestern Iranian languages through innovations such as the development of /d/ from Proto-Iranian *j- (e.g., Modern Persian *dān- "to know" versus Kurdish *zan-).[6] Unlike Eastern Iranian languages (e.g., Pashto, Ossetic), which preserve more conservative features like ergativity, the Southwestern group, including New Persian, exhibits a shift toward subject-object-verb word order and reduced inflection, adaptations likely influenced by contact with non-Iranian substrates in the Iranian plateau.[7] Persian remains the sole Iranian language attested across all three historical stages—Old, Middle, and New—underscoring its central role in the genealogy.[8]Distinctions from Ancestral Stages

New Persian emerged as a distinct stage following the Middle Persian period, marked by gradual phonological simplifications that reduced the inherited vowel system from eight in Middle Persian to a more streamlined set of six short and long vowels in Early New Persian, facilitating easier articulation and contributing to its analytic character.[1] Consonant clusters underwent epenthesis, with initial clusters like *sp- becoming *isp- (e.g., Middle Persian spāh to New Persian sepāh "army"), and word-final sounds such as -g were often lost or altered, reflecting natural drift rather than abrupt imposition.[9] These shifts, occurring primarily between the 7th and 10th centuries CE, built on Middle Persian trends but accelerated under bilingual contact environments post-Islamic conquest, distinguishing New Persian's phonology as less conservative than its ancestral forms.[10] Morphologically, New Persian further eroded the fusional elements of Old and Middle Persian, eliminating grammatical gender—retained in three forms (masculine, feminine, neuter) in Old Persian—and noun cases beyond a vestigial direct/indirect opposition, shifting reliance to postpositions and the ezāfe particle (-e) for relational marking.[11] Verb conjugation simplified, with the loss of dual number and subjunctive distinctions blurring into indicative moods, contrasting Old Persian's richly inflected paradigm of six cases and three numbers; Middle Persian had already begun this reduction, but New Persian's analytic syntax, using particles like rā for direct objects, rendered it more isolating than its predecessors.[12] This evolution prioritized clarity in multiracial, multilingual Persianate societies, where Middle Persian's residual inflections proved cumbersome for non-native scribes.[1] Lexically, the advent of New Persian coincided with extensive Arabic borrowing, introducing over 40% non-native vocabulary by the classical period—terms for administration (dawlat "state"), religion (namāz "prayer"), and science (ʿelm "knowledge")—far exceeding the Parthian and Aramaic loans in Middle Persian, which comprised under 20% of its core lexicon.[13] While ancestral stages drew from Iranian roots, New Persian integrated these calques and direct loans without supplanting indigenous words entirely, as seen in retained terms like pedar "father" from Proto-Iranian pitar, but this influx altered semantic fields, embedding Islamic cultural layers absent in pre-conquest Persian.[1] The script transitioned from the cursive Pahlavi variants of Middle Persian—derived from Aramaic and featuring ideograms (Aramaic logograms read in Persian)—to a modified Arabic abjad by the 9th century CE, incorporating four additional letters (p, č, ž, g) to accommodate Persian phonemes unrepresented in Arabic.[14] This change, post-651 CE conquest, enabled diacritics for vowels, improving orthographic fidelity over Pahlavi's ambiguity, though it introduced right-to-left directionality contrasting Old Persian's left-to-right cuneiform.[1] Such adaptation reflected pragmatic utility in caliphal bureaucracies rather than linguistic rupture, as core grammar persisted.[15]Etymology and Terminology

Historical Naming Conventions

In the early Islamic period following the Arab conquest of Iran in the 7th century CE, the nascent New Persian language—emerging from Middle Persian substrates—was primarily designated using terms rooted in regional and ethnic identifiers from the Sasanian era. The term Pārsī (or Pārsīg), denoting the language "of Pars" (the southwestern province), was commonly applied to the southern Iranian varieties, particularly in Zoroastrian and Jewish literature, as evidenced by 8th-century translator Ibn al-Muqaffaʿ's distinctions between Pārsī and other dialects like Pahlevī (Parthian-influenced).[1] This nomenclature reflected the language's continuity with Middle Persian (Pārsik), emphasizing its southwestern origins and use in administrative and religious texts preserved by non-Muslim communities into the 11th century.[1] Concurrently, Dārī gained prominence for the northeastern (Khorasanian) variant, originally the court language of the Sasanian capitals like Ctesiphon, which adapted under Abbasid rule and became the basis for literary New Persian by the 9th century.[1] This term, possibly derived from dār ("court" or "palace"), signified prestige and was used for the formalized speech of eastern Iranian elites, spreading westward as Arabic script facilitated its documentation in works like the Šāhnāma (completed ca. 1010 CE).[1] Composite designations such as Pārsi-ye Dārī ("Persian of the court") appeared in medieval texts to bridge regional forms, underscoring functional distinctions between vernacular southern Pārsī and the standardized eastern literary idiom.[16] By the 11th century, Fārsī—the Arabicized form of Pārsī, reflecting phonemic shifts in Arabic transcription—emerged in usage, as noted by poet Nāṣer-e Ḵosrow (ca. 1046 CE) to describe Persian spoken beyond Khorasan.[1] These conventions highlighted not only geographic variances but also sociolinguistic hierarchies, with Pahlevī retained by Muslims for "ancient" or Zoroastrian Middle Persian texts, distinguishing them from the evolving New Persian vernacular.[1] Over time, such terms were employed synonymously in Persianate scholarship, though Dārī and Fārsī persisted as markers of dialectal prestige in Afghanistan and Iran, respectively.[17]Modern Designations and Variants

In contemporary usage, New Persian is officially designated as Farsi (فارسی) in Iran, where it serves as the sole national language per the 1979 Constitution, spoken by approximately 53 million as a first language within the country.[18] In Afghanistan, the variety is termed Dari (دری), an official language alongside Pashto under the 2004 Constitution, with around 12-15 million native speakers, reflecting its historical role as the court language of the region.[19] In Tajikistan, it is known as Tajik (тоҷикӣ), the official language since independence in 1991, used by about 8 million speakers and codified with Russian influences from the Soviet era.[18] Internationally, the overarching term Persian persists in linguistic and diplomatic contexts, encompassing these variants as standardized forms of the same Southwestern Iranian language continuum.[19] These designations emerged post-20th century amid nation-building: "Farsi" derives from the endonym Pārsī, emphasized in Iran to distinguish from Arabic influences; "Dari" references the "language of the court" (from Dār al-Salṭana), formalized in Afghan policy to highlight its pre-Islamic heritage; and "Tajik" aligns with ethnic nomenclature for Persian-speakers in Central Asia, detached from Iranian connotations during Soviet Russification.[20] The variants exhibit high mutual intelligibility—estimated at 90-95% in spoken form—due to shared grammar, core lexicon from Middle Persian, and syntactic structure, though divergences arise from regional substrates and superstrates.[19] Key distinctions include script: Iranian Farsi and Afghan Dari employ modified Perso-Arabic alphabets (Dari with four additional letters for sounds like /g/ and /ch/), while Tajik adopted Cyrillic in 1939 under Soviet policy, reverting partially to Latin proposals but retaining Cyrillic for official use, hindering cross-variant literacy without adaptation.[21] Vocabulary varies by historical contact: Farsi incorporates heavier Arabic loanwords (up to 40% in formal registers, via Islamic scholarship); Dari features Pashto, Turkic, and some French/English terms from colonial and modern influences; Tajik shows Russian borrowings (e.g., "avtomobil" for car vs. Farsi "māshin") and Turkic elements, comprising 10-20% non-Persian elements in everyday speech.[20] Phonological shifts include Tajik's merger of certain vowels and Dari's retention of classical /w/ as /v/ or /ow/, yet core intelligibility persists, as evidenced by cross-border media consumption and literature translation with minimal barriers.[19] Peripheral variants, such as Hazaragi (with Mongolic substrata in central Afghanistan) or Aimaq dialects, extend the continuum but remain non-standardized, often aligning closer to Dari while incorporating Turkic or Mongolic features; these are not officially designated but contribute to the language's dialectal diversity without fracturing the New Persian macrolanguage status under ISO 639-3 (fas for Western Persian, tg for Tajik).[18]Historical Evolution

Post-Sasanian Transition

The Sasanian Empire fell to Arab Muslim forces in 651 CE, marking the end of Middle Persian as the dominant administrative and literary language of Iran.[1] Following the conquest, Persian-speaking populations gradually adopted Islam and the Arabic script, adapted as Perso-Arabic, while Middle Persian persisted in Zoroastrian religious texts and among pockets of the population.[1] This period saw the linguistic shift to Early New Persian, characterized by simplification of the inflectional system— including the loss of the izafa particle ī(g), direct object marker ō, and ergative verb constructions—alongside the retention of core Iranian grammatical structures.[1] Arabic exerted substantial lexical influence, introducing thousands of loanwords for administration, religion, and science, though syntactic frameworks remained predominantly Iranian.[1] The transition accelerated in eastern Iran, particularly Khorasan, under Iranian Muslim dynasties like the Tahirids (820–872 CE) and Saffarids (861–1003 CE), where Persian regained prominence as a vehicle for local administration and literature.[1] Saffarid ruler Ya'qub ibn al-Layth (r. 861–879 CE), limited in Arabic proficiency, actively promoted Persian usage, commissioning translations and compositions that bypassed Arabic intermediaries.[3] Earliest attestations of New Persian appear in Judaeo-Persian documents, such as the Tang-i Azao inscription dated 751–752 CE and a commercial letter from Dandan Öilïq around 760 CE, reflecting commercial and epigraphic use among Jewish communities in regions like Sistān and Ahvāz.[1] By the mid-9th century, prose and poetry in New Persian emerged, with the first recorded poem—a qasida by Abu'l-'Abbas of Marv—composed in 809 CE, though its preservation is uncertain.[3] More reliably attested are verses by poets like Hanzala of Bādghīs (pre-873 CE) and Muhammad b. Vasif's qasida from 865 CE, signaling the language's literary viability.[3] Notes in Persian on Quranic booklets, such as those by Ahmad Khayqānī of Tūs dated 905 CE, exemplify vernacular literacy's spread.[22] This evolution positioned New Persian as a resilient medium, adapting foreign elements without supplanting its Iranian essence, under dynastic patronage that favored regional autonomy over full Arabization.[1]Early New Persian Period

The Early New Persian period encompasses the 8th through 12th centuries CE, representing the initial phase of Persian linguistic and literary development following the Sasanian Empire's collapse and the Islamic conquest of Iran between 632 and 651 CE.[1] This era saw the language evolve from Middle Persian with relatively minor phonetic and grammatical alterations, such as a shift toward accusative syntax from the earlier ergative alignment, while preserving core features like the eżāfa construction for genitive relations, particularly in southern dialects.[1] Vocabulary expanded through heavy Arabic borrowing for religious, administrative, and scientific terms, though Iranian roots dominated everyday and epic lexicon, with some Parthian influences evident in terms like borz ("high") in epic poetry.[1][23] The adoption of the Arabic script, modified with additional diacritics for Persian phonemes, enabled widespread literary production, supplanting earlier Pahlavi, Manichean, or Syriac systems used by religious minorities.[1] Earliest surviving texts include brief inscriptions and documents, such as the Tang-i Azao rock inscription dated 751–752 CE and the Dandan Uiliq Chinese-Persian letter from circa 760 CE, attesting to administrative use in eastern Iran.[1] Poetry emerged first, with fragments traceable to the mid-9th century, including a qaṣīda by Abu'l-Abbas of Marv in 809 CE and works by Hanzala of Badghis before 873 CE; prose followed in the mid-10th century.[23] Regional dialects from Khorasan and Transoxiana, influenced by Parthian and Sogdian substrates, coalesced into a standardized literary form, often termed Dari in early Arabic sources.[23] Patronage under Iranian dynasties like the Samanids (819–999 CE) and Ghaznavids (977–1186 CE) catalyzed literary growth, particularly in Bukhara and eastern provinces, where Persian served as a vernacular counterweight to Arabic dominance in scholarship.[1] Rudaki (c. 858–941 CE), a Samanid court poet from near Samarkand, composed over 100,000 verses in New Persian, establishing genres like the qaṣīda and ġazal adapted from Arabic models but infused with Iranian themes of nature and wisdom, earning him recognition as a foundational figure in Persian poetry.[23] Prose milestones include Abu Ali Bal'ami's 963 CE translation and adaptation of al-Tabari's universal history into Persian, which introduced narrative techniques and reached broader audiences beyond Arabic-literate elites.[1][23] This period's output, blending pre-Islamic epic traditions with Islamic motifs, set precedents for later classical works like Ferdowsi's Šāh-nāma (completed c. 1010 CE), preserving Iranian mythology amid Arabization.[1]Classical Persian Era

The Classical Persian Era, spanning approximately the 10th to 18th centuries CE, represented the maturation and widespread adoption of New Persian as a literary and administrative medium across the Persianate cultural sphere, from Iran and Central Asia to the Indian subcontinent and Anatolia. Following the foundational advancements under the Samanids (819–999 CE), who patronized the language's revival against Arabic dominance, subsequent dynasties such as the Ghaznavids (977–1186 CE) and Seljuks (1037–1194 CE) elevated it in courtly and scholarly contexts.[3] This period's linguistic form exhibited stability, with grammar simplified from Middle Persian precedents—lacking inflectional cases, genders, and dual numbers—relying instead on prepositions, word order, and the ubiquitous ezafe enclitic for possession and attribution (e.g., ketâb-e man, "my book").[2] Lexical expansion was a hallmark, incorporating an estimated 20–40% Arabic-derived terms in prose and poetry, primarily for religious, philosophical, and administrative concepts, while core vocabulary and syntax retained Indo-Iranian roots; for instance, verbs conjugated via prefixes and suffixes without person-number agreement shifts beyond tense.[13] Prosody adapted Arabic quantitative meters to Persian's phonology, featuring short and long syllables in patterns like the ramal or hazaj, enabling complex rhyme schemes in forms such as the masnavi (rhymed couplets for narrative epics) and qasida (panegyric odes).[23] Phonetic shifts from early New Persian stabilized, with uvular /q/ and /ɣ/ distinguishing classical texts from later vernaculars, though regional dialects influenced spoken variants minimally in written standards. Literary output defined the era's cultural prestige, with epic, lyric, and didactic genres flourishing; Ferdowsi's Shahnameh (completed c. 1010 CE), at over 50,000 distichs, chronicled Iranian mythology in deliberately Arabicism-minimal Persian to assert ethnic continuity post-conquest.[24] Mystical and ethical works proliferated under Sufi influence, including Attar's Mantiq al-Tayr (c. 1177 CE) and Rumi's Mathnawi (completed 1273 CE), comprising 25,000 verses on spiritual allegory, alongside Sa'di's ethical treatises Gulistan (1258 CE) and Bustan (1257 CE).[25] Later Timurid and Safavid patronage (14th–18th centuries) sustained this canon, with poets like Hafez (d. 1390 CE) innovating the ghazal for ambiguous erotic-mystical expression, influencing Ottoman divan poetry and Mughal chronicles. Classical Persian functioned as a supralingual vehicle, employed in Timurid Herat's academies (e.g., under Ulugh Beg, r. 1411–1449 CE) and Safavid Isfahan's bureaucracy, fostering cross-cultural transmission without supplanting local tongues.[26] By the 18th century, under Afsharid and Zand disruptions, subtle divergences emerged—such as increased Turkic loans in eastern dialects—but the literary koine endured, resisting vernacular drift until 19th-century European contacts prompted modernization.[12] This stasis underscores New Persian's resilience, adapting Islamic-Arabic elements while preserving syntactic autonomy, as evidenced in archival manuscripts from Baghdad to Delhi.[19]Standardization in the Modern Age

In the twentieth century, the standardization of New Persian advanced through state-sponsored institutions and policies in Iran, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan, reflecting the language's pluricentric character with distinct official varieties: Iranian Persian (Farsi), Dari, and Tajik.[27] These efforts emphasized orthographic consistency, lexical purification, and educational promotion, often in response to foreign linguistic influences and script reforms.[28] In Iran, the Pahlavi government initiated formal standardization with the founding of the Academy of Iran on May 20, 1935, tasked with protecting Persian from excessive Arabic, French, and English loanwords while developing neologisms and standardizing spelling rules, spacing, and diacritic usage in the Perso-Arabic script.[28] Following the 1979 Islamic Revolution, the institution was restructured as the Academy of Persian Language and Literature (Farhangestān-e Zabān va Adab-e Fārsī) in 1987 under the Ministry of Education, continuing work on dictionaries, terminology committees, and resistance to radical script changes like Latinization proposals.[28] These bodies prioritized empirical revival of pre-Islamic Persian roots over wholesale adoption of foreign terms, producing resources such as the Dehkhoda Dictionary expansions and official guidelines that influenced print media, broadcasting, and school curricula.[29] Afghanistan's standardization of Dari, the eastern variety of New Persian, gained momentum post-1920s independence, with official status alongside Pashto enshrined in the 1964 constitution and reinforced in subsequent charters.[30] Government radio and education systems promoted a formalized pronunciation aligned with classical literary Persian, approximating Tehran's urban dialect while accommodating regional accents as a lingua franca for over 50% of the population.[19] Orthographic norms retained the Perso-Arabic script with minor adaptations for Dari-specific phonemes, supported by Kabul's Academy of Sciences language section, which compiled glossaries and grammars to counter Pashto dominance and Soviet-era influences.[31] In Tajikistan, Soviet policies from the 1929 establishment of the Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic drove standardization of Tajik as the state language, initially modifying the Perso-Arabic script in the early 1920s, shifting to Latin in 1927, and adopting Cyrillic by 1939 to facilitate Russification and literacy campaigns.[32] This process incorporated Russian loanwords for technical terms while standardizing literary norms through state publishing and schools, elevating educated speech toward classical Persian models despite Cyrillic's divergence from Iranian and Afghan orthographies.[33] Post-1991 independence, debates over reverting to Perso-Arabic or Latin scripts persisted, but Cyrillic remained dominant, with the Tajik Academy of Sciences overseeing ongoing lexical and grammatical codification.[32]Varieties and Dialects

Iranian Persian

Iranian Persian, known domestically as Farsi, functions as the official language of Iran and the primary medium for government, education, media, and public administration. It is natively spoken by approximately 50.6 million people within Iran, representing the majority ethnic Persian population and serving as a second language for many among the country's ethnic minorities, such as Azeris and Kurds, thereby fostering national cohesion.[18] The standard variety draws from the Tehran dialect, which has emerged as the prestige form due to urbanization and centralization of political power in the capital since the Qajar era.[12] Standardization efforts intensified in the 20th century through the Academy of the Persian Language and Literature, founded on May 20, 1935, by Reza Shah Pahlavi to systematize grammar, orthography, and vocabulary while reducing reliance on Arabic loanwords in favor of revived ancient Persian or newly coined terms. This institution continues to approve technical terminology, promote linguistic purity by substituting Perso-Arabic hybrids with indigenous equivalents—such as dāneshgāh for "university" derived from Avestan roots—and regulate usage in official domains to counterbalance historical Islamic influences.[34] Such policies reflect a nationalist agenda prioritizing pre-Islamic Iranian heritage, though implementation varies, with Arabic-derived words persisting in religious and literary contexts.[35] Distinct from Dari and Tajik, Iranian Persian features phonological shifts including the neutralization of certain vowel contrasts preserved in Dari, such as distinctions between short /e/ and /a/ in unstressed positions, contributing to a more streamlined spoken form. Lexically, it integrates greater numbers of European borrowings, particularly from French (e.g., siyāsat alongside calques for policy terms) and English in contemporary domains like technology and science, alongside Turkic elements from Ottoman interactions, contrasting with Dari's retention of more classical Arabic vocabulary and archaic Perso-Arabic forms. Pronunciation diverges in realizations like the fricative /v/ for the letter vāv (versus approximant /w/ in Dari) and variable voicing of /q/ as /ɢ/ or /ɣ/ in urban standards.[12] Regional dialects, including those of central Iran (e.g., Isfahani with softened consonants) and eastern provinces (e.g., Khorasani with retained archaisms), exhibit substrate influences from local languages but converge toward the Tehrani norm in formal settings, ensuring high mutual intelligibility across Iran while maintaining subtle prosodic variations in intonation and rhythm.[36]Dari in Afghanistan

Dari, the eastern variety of New Persian spoken in Afghanistan, functions as one of the country's two official languages alongside Pashto and serves as the primary lingua franca among diverse ethnic groups. It is native to ethnic Tajiks, Hazaras, and Aimaqs, while also widely adopted by Pashtuns and others for interethnic communication, education, and administration.[37] Approximately 77% of Afghanistan's population uses Dari, reflecting its role in unifying a multilingual society where Pashto accounts for 48% amid significant bilingualism. The variety traces its roots to the post-Islamic evolution of New Persian in the Khorasan region, where it developed as the literary and court language from the 9th century onward, retaining closer ties to classical Persian forms than some western dialects.[38] The modern designation "Dari" derives from "Darbari," denoting the language of the Samanid court in eastern Iran and Central Asia around the 10th century, though its official adoption in Afghanistan intensified in the 20th century to assert national distinction from Iranian Farsi amid Pashtun-centric identity politics.[39] Dialects vary regionally, with the Kabul-based standard influencing media and education, while northern variants incorporate Turkic elements and southern ones show Pashto substrate effects; principal subdialects include Kabuli, Herati, and Hazaragi, the latter featuring Mongolic influences from Hazara heritage.[31] Linguistically, Dari exhibits phonological conservatism, such as frequent realization of classical /w/ as rather than Iranian , and a more restricted vowel inventory compared to Iranian Persian, alongside lexical divergences like "shanbe" for Saturday (versus Iranian "shanbe") and greater retention of Arabic vocabulary due to religious and historical ties.[40] It employs the Perso-Arabic script without the post-1930s Iranian orthographic reforms, preserving spellings like "خ" for classical /x/ sounds, ensuring high mutual intelligibility with Iranian Persian—estimated at over 95%—despite these variances.[41] Since the Taliban's return to power in August 2021, Dari has faced systematic marginalization in official spheres, driven by the group's predominantly Pashtun composition and ideological preference for Pashto as the prestige language.[42] Policies include removing Dari from public signage and billboards shortly after takeover, substituting Pashto equivalents, and a July 2025 directive from the Ministry of Interior prohibiting Dari in government correspondence to enforce Pashto primacy.[43] [44] These measures extend to media and education, where Persian terms like "danishjo" (student) have been banned in favor of Pashto neologisms, reflecting a broader Pashtunization effort despite Dari's entrenched role in commerce and urban life.[44]Tajik in Central Asia

Tajik, also known as Tajiki, constitutes the Central Asian variety of New Persian, primarily spoken in Tajikistan and by ethnic Tajiks in Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan. It functions as the official national language of Tajikistan, where it predominates among the approximately 8 million native speakers in a population of over 9 million.[45][46] Russian serves as an additional official interethnic language, reflecting lingering Soviet-era multilingualism.[33] Prior to the 20th century, speakers in the region identified their speech as Farsi, without a distinct ethnolinguistic label separating it from other Persian dialects.[32] Soviet nationalities policy in the 1920s elevated it to the status of a separate language, culminating in the establishment of the Tajik ASSR in 1924 and full SSR in 1929. Standardization efforts during the 1920s and 1930s, led by Russian and Tajik linguists, drew primarily from northern dialects spoken around Dushanbe and Khujand to form the basis of the modern literary standard.[47] Orthographic reforms under Soviet influence transitioned Tajik from the Perso-Arabic script to a Latin-based alphabet in the late 1920s, before adopting the Cyrillic script in 1940 to facilitate Russification and administrative uniformity across the USSR.[48] This Cyrillic system, with 33 letters including four unique to Tajik (ё, ю, я, э), remains in use today, despite post-independence discussions of reverting to Perso-Arabic or Latin scripts. The script divergence contributes to reduced written mutual intelligibility with Iranian Persian and Afghan Dari, though spoken forms retain high comprehension due to shared grammar and core vocabulary. Lexically, Tajik incorporates extensive Russian borrowings—estimated at over 2,500 terms—acquired during seven decades of Soviet rule, particularly in technical, administrative, and modern domains, such as kompyuter for computer or avtomobil for automobile.[49] Post-1991 independence, de-Russification initiatives have sought to replace these with native or Perso-Arabic equivalents, though progress varies.[50] Grammatical structure aligns closely with other New Persian varieties, featuring subject-object-verb order, ezafe constructions, and minimal inflection, but exhibits minor phonological shifts, like the realization of /q/ as /ɣ/ in some contexts. Dialectal variation within Tajik includes northern dialects (e.g., around Khujand), central dialects along the Zarafshan Valley, and southern dialects in Kulob and surrounding areas, which influence regional accents and vocabulary but do not impede standard comprehension. In Uzbekistan, Tajik communities in Bukhara and Samarkand preserve dialects closer to classical Persian, historically significant as centers of Persianate culture.[32] These peripheral varieties, sometimes using Perso-Arabic script informally, highlight Tajik's continuum with broader Persian linguistic heritage despite political and orthographic separations.Peripheral Dialects

Peripheral dialects of New Persian encompass varieties spoken by ethnic minorities or in geographically isolated regions, often exhibiting substrate influences from non-Iranian languages or retention of archaic features due to limited contact with core standards. These include Hazaragi, Aimaq, and Judeo-Persian, which diverge phonologically and lexically from Iranian Persian, Dari, and Tajik while remaining mutually intelligible within the New Persian continuum. Such dialects typically arise among nomadic or historically marginalized groups, preserving elements like Turkic-Mongolic loanwords from medieval migrations.[51] Hazaragi, spoken primarily by the Hazara people in central Afghanistan's Hazarajat region, northeastern Iran, and parts of Pakistan, numbers approximately 1.8 million speakers as of early 2000s estimates. It derives from Dari but incorporates substantial Turco-Mongolian vocabulary—up to 10-15% in some registers—reflecting the Hazaras' descent from Mongol forces under Genghis Khan in the 13th century, alongside minor Indian lexical elements from historical trade. Phonologically, Hazaragi retains inter-vocalic stops (e.g., /b/ for standard /v/ in words like kabul for "accept") and shows vowel shifts absent in core varieties, though mutual intelligibility with Dari remains high at around 80-90%. Despite linguistic classification as a dialect, Hazara advocates often assert its status as a distinct language to emphasize ethnic identity.[52] Aimaq, used by the semi-nomadic Aimaq tribal confederation across northwestern and western Afghanistan, eastern Iran, and sporadically in Tajikistan, features subdialects among subgroups like the Taimani, Jamshidi, and Firozkohi. This variety blends core Dari with Turkic admixtures, estimated at 5-10% of lexicon, stemming from Oghuz Turkic interactions during Timurid and post-Mongol eras. Dialectal variation includes conservative retention of /w/ sounds (e.g., šoma pronounced with labial glide) and simplified verb conjugations compared to urban Dari; speakers total around 1-2 million, with gradual sedentarization eroding nomadic-specific idioms. Aimaq serves as a marker of tribal identity, distinct from urban Afghan Persian.[53] Judeo-Persian, historically spoken by Iranian Jewish communities in central and eastern Persia until mass emigration post-1979, represents a scriptally and lexically distinct variant now largely confined to Israel and small diaspora pockets. Written in Hebrew script with adaptations for Persian phonemes, it preserves Middle Persian archaisms like izafet constructions and vocabulary from Talmudic-era substrates, alongside Hebrew-Aramaic integrations (e.g., 5-10% Semitic loans in religious texts). Phonetic traits include uvular /q/ retention and avoidance of Arabic loans favoring native Iranian roots, differing from Muslim Persian norms; speaker numbers dwindled from tens of thousands in the early 20th century to under 5,000 fluent users by 2020s, with revitalization efforts limited by assimilation. As a minority dialect, it exemplifies peripheral conservatism, uninfluenced by state standardization.[51]Phonology

Consonant System

The consonant phoneme inventory of New Persian comprises 23 distinct segments, a system that has remained largely stable since Early New Persian while incorporating uvular and glottal elements from Arabic loanwords.[1][54] These phonemes are articulated across various places and manners, with no phonemic aspiration or voicing contrasts beyond standard stops and fricatives; voiced fricatives like /β/ and /δ/ from intervocalic lenition of /b/ and /d/ in Early New Persian merged into stops or approximants by the classical period.[1]| Manner of Articulation | Bilabial | Labiodental | Dental/Alveolar | Postalveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | p b | t d | k ɡ | q | ||||

| Affricate | tʃ dʒ | |||||||

| Fricative | f v | s z | ʃ ʒ | x ɣ | h | |||

| Nasal | m | n | ||||||

| Lateral approximant | l | |||||||

| Rhotic | r | |||||||

| Glides | j |

Vowel System and Prosody

The vowel system of New Persian features six monophthongs, categorized as three short vowels (/a/, /e/, /o/) and three long vowels (/ā/, /ī/, /ū/), with phonetic realizations including [æ] or for short /a/, or [ə] (in unstressed positions) for /e/, and for /o/; long /ā/ as [ɒː], /ī/ as [iː], and /ū/ as [uː].[58] This six-vowel structure emerged from Middle Persian, where length was phonemically contrastive, but in later New Persian stages and modern varieties, duration distinctions have partially eroded, with vowel quality becoming primary, though lengthening occurs in stressed or open syllables.[59] Four diphthongs (/ai/, /au/, /ei/, /ou/) also appear, primarily in loanwords or archaic forms, but they often monophthongize in contemporary speech (e.g., /ai/ to [eː] or [ɛi]).[58] Lexical stress in New Persian is largely predictable and defaults to the final syllable for nouns, adjectives, and most adverbs (e.g., ketâb 'book' stressed as ke.tâb), reflecting a right-edge alignment that favors heavy (CVːC or CVCC) syllables when present.[60] Verbs exhibit stress on the final syllable of their stem or ending, with proclitic prefixes (e.g., ne- 'not', mi- for progressive) shifting it leftward onto the prefix (e.g., né-xarid-am 'I didn't buy').[61] Arabic loanwords may retain penultimate stress (e.g., madrasé 'school'), but native patterns dominate, and stress does not alter word meaning, unlike in languages with lexical stress.[62] Phrasal prosody organizes into accentual phrases (APs), the smallest domain bearing a pitch accent ((L+)H*) on the lexically stressed syllable, often encompassing one content word plus enclitics, terminated by a high (h) or low (l) boundary tone.[61] Intonational phrases (IPs) group one or more APs; declaratives feature a falling nuclear contour ending in L%, while yes/no questions rise to H% with elevated pitch register (100–148 Hz vs. 89–125 Hz in statements) and final vowel lengthening (up to 210 ms).[61] Wh-questions align the wh-word as the nuclear AP with heightened pitch, followed by deaccenting and L% closure, supporting focus marking without dedicated morphological cues.[61] This system underscores Persian's syllable-timed rhythm, with stress cued by duration, intensity, and F0 rise rather than strict quantity sensitivity.[63]Grammar

Morphological Features

New Persian morphology is characterized by significant simplification from earlier Iranian stages, with the loss of grammatical gender, case inflections (beyond specific enclitics like -rā for definite direct objects), and dual number, resulting in a largely analytic system supplemented by agglutinative elements.[64][65] Inflectional processes primarily involve suffixes for plurality and verbal person-number agreement, while derivation employs a mix of suffixes and limited prefixes, often drawing on native Iranian roots or Arabic loans.[66] The ezafe enclitic -(e/y)e serves as a key functional morpheme, linking nouns to possessors, modifiers, or complements in a head-initial dependency structure, e.g., ketâb-e man ("my book").[64][65] Nouns lack inherent gender marking and case endings, with singularity unmarked and plurality indicated by suffixes such as -hâ (predominantly for inanimates and increasingly all nouns) or -ân (for animates, especially humans), alongside vestigial Arabic patterns like broken plurals (e.g., ketâb "book" to kotob) or suffixal -ât/-in in loanwords.[64][65] Definiteness is not morphologically encoded on nouns themselves but emerges contextually or via the indefinite suffix -i (e.g., ketâb-i "a book"), applicable across numbers.[64] Derivational suffixes on nouns include diminutives like -ak (doxtar-ak "little girl") and agentives like -gar (âhângar "blacksmith"), with prefixes such as na- for negation (na-dâd "non-existent").[66] Adjectives inflect minimally, showing no agreement in gender, number, or case with the nouns they modify; they follow the head noun via ezafe and form comparatives with -tar (bozorg-tar "larger") and superlatives with -tarin (bozorg-tarin "largest").[65] Derivation yields adjectival forms via suffixes like -i (irâni "Iranian") or -âne (dânesmand-âne "scholarly"), and prefixes including por- (por-sang "full of stones") or bi- (bi-sar "headless").[66] Verbs derive from a limited set of roots (often around 200 simple lexemes), frequently combining into complex predicates with light verbs (e.g., kardan "to do" in zadan kardan "to hit"), and distinguish present and past stems for tense formation.[64] Inflection uses person-number suffixes (e.g., -am for 1SG, -and for 3PL) on stems, with prefixes mi- for habitual present (mi-ravam "I go habitually") and be- for subjunctive or imperative (be-rav "go!"); negation employs na- or ne-.[64][65] Non-finite forms include infinitives (past stem + -an, e.g., raftan "to go") and participles, supporting periphrastic constructions for aspects like perfective (e.g., rafte-am "I have gone").[65] Passive voice lacks dedicated morphology, relying on analytic structures with the verb šodan "to become" and participles.[65] Pronouns exhibit enclitic forms for possession or objects (e.g., man "I" to -am), with limited inflection; personal pronouns distinguish direct/indirect series but lack case beyond context.[64] Overall, derivation favors suffixation for lexical expansion, incorporating Arabic masdar forms as nouns, while inflection remains sparse, emphasizing word order and particles for grammatical relations.[66][65]Syntactic Patterns

New Persian follows a basic subject-object-verb (SOV) word order in declarative clauses, with modifiers typically preceding the verb and noun phrases exhibiting head-initial structure despite the overall head-final tendencies in verb phrases.[67] This canonical order allows flexibility for topicalization or focus, but deviations are constrained by syntactic rules governing adjacency and dependency.[67] A defining feature of noun phrases is the ezafe construction, an enclitic linker realized as /=e/ (or /=je/ after vowels) that binds a head noun, adjective, or preposition to its attributive, possessive, or descriptive dependents, forming complex phrases through chaining. For instance, the phrase "the white wedding dress of Maryam" translates as lebās-e arusi-e sefid-e Maryam, where each ezafe reiterates to connect successive modifiers to the head.[68] This construction, inherited from Middle Persian's genitive linker ī and solidified in New Persian as a head-marking affix, applies to nominal, adjectival, and some prepositional phrases but is absent with definite determiners like in 'this' or proper names in direct attribution.[68] Direct objects undergo differential object marking via the enclitic =rā, which obligatorily attaches to definite, specific, or animate objects to signal their role, while indefinite or non-specific objects remain unmarked. An example is Maryam zan-i (=rā) dar kuche did ('Maryam saw a (=the) woman in the street'), where =rā emphasizes specificity or topicality.[68] This marker evolved from Middle Persian's indirect object dative rāy, progressively specializing as a direct object indicator in New Persian by the 10th-12th centuries, correlating with transitivity and discourse prominence.[68] Predicates frequently employ complex predicate structures, pairing a non-verbal host (noun, adjective, preposition, or particle) with a light verb to convey nuanced semantics, as simplex verbs number only around 250 in common use. Light verbs like zadan 'hit' or dādan 'give' supply tense, aspect, and argument structure, as in harf zadan 'to talk' (lit. 'word hit') or sili zadan 'to slap'.[68] These constructions, prominent since Early New Persian, expand the verbal lexicon and exhibit syntactic behaviors distinct from full verbs, such as host incorporation and aspectual restrictions.[68] Negation applies syntactically through the prefix na- (or ne- before imperfective mi-) on the verb stem, yielding forms like na-xarid 'did not buy', with scope over the entire predicate and compatibility with negative concord elements like hič 'no/none' for emphatic denial.[69] Yes/no questions prepend the particle āyā to the declarative clause while preserving SOV order, as in Āyā Maryam ketāb rā xarid? ('Did Maryam buy the book?'), or rely on rising intonation without inversion; wh-questions front the interrogative (e.g., ki, čē) but retain underlying SOV for the remainder.[70]Orthography

Perso-Arabic Script Mechanics

The Perso-Arabic script for New Persian consists of 32 letters, extending the 28-letter Arabic alphabet with four additional characters to represent phonemes absent in Arabic: پ for /p/, چ for /tʃ/, ژ for /ʒ/, and گ for /ɡ/.[71][72] This adaptation occurred following the Arab conquest of Persia in the 7th century, with the script standardized for Persian by the 9th century CE.[73] Letters are rendered in a cursive, right-to-left script, where most connect to adjacent letters, exhibiting four positional variants: isolated (standalone), initial (word-start), medial (internal), and final (word-end).[74][75] Six letters—ا, د, ذ, ر, ز, and و—do not connect to a following letter, disrupting the ligature flow and requiring distinct handling in word formation.[74] No uppercase or lowercase distinctions exist, and the script lacks inherent short vowel markers in everyday use, relying on reader familiarity for disambiguation.[72][75] Short vowels (/a/, /e/, /o/, /i/, /u/) are optionally indicated by diacritical marks (harakat) above or below consonants, such as َ for /a/ or ِ for /i/, but these are rarely employed in printed or handwritten Persian due to contextual predictability.[76] Long vowels are explicitly represented: آ or ا for /ɒː/, و for /uː/, and ی or ى for /iː/.[72] Consonants like ق (/ɢ/ or /ɣ/), غ (/ɣ/), and ح (/h/) distinguish uvular and pharyngeal sounds from Arabic origins, though Persian pronunciation simplifies some, such as merging emphatic Arabic sounds into plain equivalents.[71] The /v/ sound uses either و or ى depending on position, adding minor orthographic flexibility.[77] Numerals follow the Eastern Arabic-Indic system (٠١٢٣٤٥٦٧٨٩), distinct from Western Arabic digits, and are written left-to-right within right-to-left text.[73] This script's defectiveness for short vowels necessitates rote memorization for literacy, as homographs like کل ("kal", meaning mole or class) versus گل ("gol", meaning flower) differ only in unwritten vowels.[78] Despite these challenges, the system effectively conveys New Persian's phonology, with ambiguities resolved through syntactic and lexical context rather than explicit marking.[79]Script Variations and Reforms

The primary orthographic variation among New Persian varieties stems from geopolitical history: Iranian Persian (Farsi) and Afghan Persian (Dari) employ the Perso-Arabic script, a right-to-left cursive abjad with 32 letters adapted from Arabic by adding پ /p/, چ /tʃ/, ژ /ʒ/, and گ /ɡ/ to represent sounds absent in Arabic. Tajik, however, uses a Cyrillic-based alphabet of 33 letters, introduced during Soviet rule to distance it from Perso-Arabic influences associated with Islam and Iran.[32] This divergence creates barriers to mutual intelligibility in written form, despite high spoken comprehension among varieties.[80] Minor variations exist within Perso-Arabic usage: Farsi orthography in Iran favors simplified modern spellings (e.g., omitting certain diacritics for short vowels, which are implied contextually), while Dari in Afghanistan retains more conservative conventions influenced by classical Persian and Arabic, such as fuller use of optional vowel markers (zer, zabar, pesh) in religious or formal texts.[81] These differences arise from local standardization efforts rather than fundamental script changes, with both adhering to the same letter inventory and joining rules.[82] Reforms have been most pronounced in Tajik orthography. Following Tajikistan's 1991 independence, a 1998 spelling reform abolished obsolete Cyrillic letters like ц (/ts/, rare in native vocabulary) and adjusted digraphs to better match Tajik phonology, reducing Russified elements while retaining Cyrillic dominance.[32] Earlier shifts included adoption of a Latin alphabet in 1928 for anti-religious romanization, replaced by Cyrillic in 1940 amid Stalinist policies; post-Soviet Latinization proposals in the 1990s failed due to implementation costs, teacher retraining needs, and geopolitical aversion to Persian-script revival linked to Iranian cultural influence.[32] In 2019, President Emomali Rahmon mandated updates to the Tajik orthographic dictionary to standardize vocabulary and curb excessive Russification.[83] In Iran and Afghanistan, reforms have been limited and unsuccessful. Iranian intellectuals since the 19th century proposed phonetic simplifications or Latinization to address the Perso-Arabic script's ambiguities (e.g., unwritten short vowels leading to homographs), but these faced resistance from cultural guardians emphasizing ties to classical literature and Islam.[81] A 2025 initiative in Germany developed Latin-script teaching materials for Persian diaspora, but it lacks official adoption in Iran.[84] Afghan Dari remains unreformed under Taliban governance, prioritizing scriptural fidelity over modernization.[85] Marginal movements like "Parsig" advocate reviving pre-Islamic Pahlavi script elements for purism, but they hold no institutional sway.[15]Lexicon

Core Iranian Vocabulary

The core Iranian vocabulary of New Persian consists of terms inherited from Middle Persian (c. 3rd–9th centuries CE) and earlier stages such as Old Persian (c. 6th–4th centuries BCE), preserving Indo-Iranian roots in foundational semantic fields like kinship, numerals, body parts, and natural elements. These native words form the substrate of everyday speech, largely unaffected by the influx of approximately 8,000 Arabic loanwords that entered post-7th-century Islamic conquest, which primarily impacted learned, administrative, and abstract domains rather than basic lexicon.[86][1] Linguistic continuity is evident in Early New Persian texts (8th–12th centuries CE), where native terms coexisted with but were not supplanted by borrowings, as seen in works like the Šāh-nāme (c. 1010 CE) by Ferdowsi, which minimized Arabic elements to emphasize Iranian heritage.[1] Key examples illustrate this retention:- Kinship and family: Terms such as pedar (father), mādar (mother), barādar (brother), and xāhar (sister) derive directly from Middle Persian equivalents (pidar, mādar, brādar, xāhar), tracing to Proto-Iranian *pitar-, *mātar-, *brātar-, and xwahar-, respectively, maintaining phonetic and semantic stability over millennia.[1]

- Numerals: The decimal system features native Iranian roots, including yek (one, from Proto-Iranian *ēwa), do (two, from *dwa), se (three, from *θri), čahār (four, from *čathwar-), and panj (five, from *panča), unchanged in core usage since Old Persian inscriptions.[1]

- Body and health: Words like sar (head), dast (hand), pa (foot), and pezešk (physician or medicine) persist from Middle Persian (sr, dast, pāy, wišibuz), with pezešk exemplifying professional terms rooted in pre-Islamic Iranian healing traditions.[1]

- Nature and environment: Native designations include āb (water, from Old Persian ap-), ātaš (fire, from Avestan ātar- via Middle Persian ādur), zamin (earth or ground, from Proto-Iranian *zam-), bāğ (garden, from Middle Persian wāg), and zemestān (winter, from Middle Persian zimištān), reflecting ancient Zoroastrian cosmological emphases on elemental forces.[1][86]

- Religious and existential concepts: Despite Islamic influence, core terms for spiritual practices remained Iranian, such as xodā (God), jān (soul), gonāh (sin), namāz (prayer), and rūza (fasting), avoiding Arabic synonyms like allāh or ṣalāh in vernacular contexts.[86]

Loanwords and Borrowing Dynamics

New Persian lexicon incorporates a substantial number of loanwords, predominantly from Arabic, reflecting the linguistic impact of the 7th-century Arab conquest and subsequent Islamization. Approximately 8,000 Arabic loanwords remain in current use, comprising about 40% of a standard 20,000-word literary vocabulary.[86] These borrowings entered primarily through bilingual scholarship and administrative needs, with the proportion rising from around 30% in the 10th century to 50% by the 12th century, driven by literary styles favoring ornate prose.[87] Semantic fields dominated by Arabic include abstract concepts (36% of loans), cultural and intangible terms (54%), and to a lesser extent tangible objects (10%), such as religious terms (ṣalāt 'prayer'), scientific nomenclature (ʿelm 'science'), and governance (ḥokumat 'government').[86] Loanwords undergo phonetic and morphological adaptation to align with Persian phonology and grammar; for instance, Arabic emphatic consonants are simplified (e.g., ṣ to /s/), and feminine endings diversify into concrete -at (810 items, e.g., ketābat 'writing') or abstract -a (640 items, e.g., maʿnā 'meaning').[86] Borrowing peaked by the 13th century, after which nativist movements produced Persian neologisms (e.g., melli-yat 'nationalism' from Arabic roots), reducing reliance on new Arabic imports post-1930s language reforms.[86] Secondary sources include Turkic languages, with roughly 600 Turkish loanwords integrated via historical interactions under Turkic dynasties, often in military and pastoral domains, though constituting a minor fraction compared to Arabic.[88] European influences emerged in the 19th century amid modernization, with French providing 1,200–4,000 terms in technology, administration, and culture (e.g., kerāvāt 'cravat' from cravate, with epenthetic vowel for initial clusters).[89] English loans, numbering in the hundreds (e.g., 340 documented in dictionaries and media), have surged in contemporary colloquial speech for globalized concepts like computing and entertainment, showing partial phonetic shifts (e.g., kompyūter 'computer') and semantic narrowing.[90] [89] Borrowing dynamics favor domains lacking robust native equivalents, such as abstract philosophy or modern science, mediated by elite literacy, trade, and conquest rather than substrate replacement.[86] Adaptation prioritizes Persian core phonemes, preserving donor forms in formal registers while colloquial variants accelerate integration. Efforts by the Persian Language Academy since 1935 promote calques and revivals to counter foreign influx, yet globalization sustains English borrowing, particularly in urban youth slang and digital media.[89] This selective permeability underscores Persian's resilience, maintaining Indo-Iranian roots amid areal convergence.Literary Tradition

Foundational Texts and Authors