Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

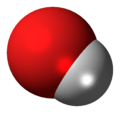

Hydroxyl radical

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2010) |

| |||

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Hydroxyl radical

| |||

| Systematic IUPAC name | |||

Other names

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| 105 | |||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| HO | |||

| Molar mass | 17.007 g·mol−1 | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | 11.8 to 11.9[2] | ||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Std molar

entropy (S⦵298) |

183.71 J K−1 mol−1 | ||

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

38.99 kJ mol−1 | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related compounds

|

O2H+ OH− O22− | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

The hydroxyl radical, denoted as •OH or HO•,[a] is the neutral form of the hydroxide ion (OH–). As a free radical, it is highly reactive and consequently short-lived, making it a pivotal species in radical chemistry.[3]

In nature, hydroxyl radicals are most notably produced from the decomposition of hydroperoxides (ROOH) or, in atmospheric chemistry, by the reaction of excited atomic oxygen with water. They are also significant in radiation chemistry, where their formation can lead to hydrogen peroxide and oxygen, which in turn can accelerate corrosion and stress corrosion cracking in environments such as nuclear reactor coolant systems. Other important formation pathways include the UV-light dissociation of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and the Fenton reaction, where trace amounts of reduced transition metals catalyze the breakdown of peroxide.

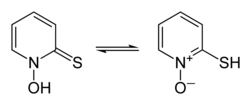

In organic synthesis, hydroxyl radicals are most commonly generated by photolysis of 1-Hydroxy-2(1H)-pyridinethione.

The hydroxyl radical is often referred to as the "detergent" of the troposphere because it reacts with many pollutants, often acting as the first step to their removal. It also has an important role in eliminating some greenhouse gases like methane and ozone.[4] The rate of reaction with the hydroxyl radical often determines how long many pollutants last in the atmosphere, if they do not undergo photolysis or are rained out. For instance, methane, which reacts relatively slowly with hydroxyl radicals, has an average lifetime of >5 years and many CFCs have lifetimes of 50+ years. Pollutants, such as larger hydrocarbons, can have very short average lifetimes of less than a few hours.

The first reaction with many volatile organic compounds (VOCs) is the removal of a hydrogen atom, forming water and an alkyl radical (R•):

- •OH + RH → H2O + R•

The alkyl radical will typically react rapidly with oxygen forming a peroxy radical:

- R• + O2 → RO2•

The fate of this radical in the troposphere is dependent on factors such as the amount of sunlight, pollution in the atmosphere and the nature of the alkyl radical that formed it (see chapters 12 & 13 in External Links "University Lecture notes on Atmospheric chemistry").

Biological significance

[edit]Hydroxyl radicals can occasionally be produced as a byproduct of immune action. Macrophages and microglia most frequently generate this compound when exposed to very specific pathogens, such as certain bacteria. The destructive action of hydroxyl radicals has been implicated in several neurological autoimmune diseases such as HIV-associated dementia, when immune cells become over-activated and toxic to neighboring healthy cells.[5]

The hydroxyl radical can damage virtually all types of macromolecules: carbohydrates, nucleic acids (mutations), lipids (lipid peroxidation) and amino acids (e.g. conversion of Phe to m-tyrosine and o-tyrosine). The hydroxyl radical has a very short in vivo half-life of approximately 10−9 seconds and a high reactivity.[6] This makes it a very dangerous compound to the organism.[7][8]

Unlike superoxide, which can be detoxified by superoxide dismutase, the hydroxyl radical cannot be eliminated by an enzymatic reaction. Mechanisms for scavenging peroxyl radicals for the protection of cellular structures include endogenous antioxidants such as melatonin and glutathione, and dietary antioxidants such as mannitol and vitamin E.[7]

Importance in the Earth's atmosphere

[edit]The hydroxyl radical (•OH) is one of the main chemical species controlling the oxidizing capacity of the Earth's atmosphere, having a major impact on the concentrations and distribution of greenhouse gases and pollutants. It is the most widespread oxidizer in the troposphere, the lowest part of the atmosphere. Understanding •OH variability is important to evaluating human impacts on the atmosphere and climate. The •OH species has a lifetime in the Earth's atmosphere of less than one second.[9] Understanding the role of •OH in the oxidation process of methane (CH4) present in the atmosphere to first carbon monoxide (CO) and then carbon dioxide (CO2) is important for assessing the residence time of this greenhouse gas, the overall carbon budget of the troposphere, and its influence on the process of global warming.

The lifetime of •OH radicals in the Earth's atmosphere is very short; therefore, •OH concentrations in the air are very low and very sensitive techniques are required for its direct detection.[10] Global average hydroxyl radical concentrations have been measured indirectly by analyzing methyl chloroform (CH3CCl3) present in the air. The results obtained by Montzka et al. (2011)[11] show that the interannual variability in •OH estimated from CH3CCl3 measurements is small, indicating that global •OH is generally well buffered against perturbations. This small variability is consistent with measurements of methane and other trace gases primarily oxidized by •OH, as well as global photochemical model calculations.

Astronomical importance

[edit]First detection of interstellar •HO

[edit]The first experimental evidence for the presence of 18 cm absorption lines of the hydroxyl (•HO) radical in the radio absorption spectrum of Cassiopeia A was obtained by Weinreb et al. (Nature, Vol. 200, pp. 829, 1963) based on observations made during the period October 15–29, 1963.[12]

Important subsequent reports of •HO astronomical detections

[edit]| Year | Description |

|---|---|

| 1967 | •HO Molecules in the Interstellar Medium. Robinson and McGee. One of the first observational reviews of •HO observations. •HO had been observed in absorption and emission, but at this time the processes which populate the energy levels are not yet known with certainty, so the article does not give good estimates of •HO densities.[13] |

| 1967 | Normal •HO Emission and Interstellar Dust Clouds. Heiles. First detection of normal emission from •HO in interstellar dust clouds.[14] |

| 1971 | Interstellar molecules and dense clouds. D. M. Rank, C. H. Townes, and W. J. Welch. Review of the epoch about molecular line emission of molecules through dense clouds.[15] |

| 1980 | •HO observations of molecular complexes in Orion and Taurus. Baud and Wouterloot. Map of •HO emission in molecular complexes Orion and Taurus. Derived column densities are in good agreement with previous CO results.[16] |

| 1981 | Emission-absorption observations of •HO in diffuse interstellar clouds. Dickey, Crovisier and Kazès. Observations of fifty-eight regions which show HI absorption were studied. Typical densities and excitation temperature for diffuse clouds are determined in this article.[17] |

| 1981 | Magnetic fields in molecular clouds—•HO Zeeman observations. Crutcher, Troland and Heiles. •HO Zeeman observations of the absorption lines produced in interstellar dust clouds toward 3C 133, 3C 123, and W51.[18] |

| 1981 | Detection of interstellar •HO in the Far-Infrared. J. Storey, D. Watson, C. Townes. Strong absorption lines of •HO were detected at wavelengths of 119.23 and 119.44 microns in the direction of Sgr B2.[19] |

| 1989 | Molecular outflows in powerful •HO megamasers. Baan, Haschick and Henkel. Observations of •H and •HO molecular emission through •HO megamasers galaxies, in order to get a FIR luminosity and maser activity relation.[20] |

Energy levels

[edit]•HO is a diatomic molecule. The electronic angular momentum along the molecular axis is +1 or −1, and the electronic spin angular momentum S=1/2. Because of the orbit-spin coupling, the spin angular momentum can be oriented in parallel or anti-parallel directions to the orbital angular momentum, producing the splitting into Π1/2 and Π3/2 states. The 2Π3/2 ground state of •HO is split by lambda doubling interaction (an interaction between the nuclei rotation and the unpaired electron motion around its orbit). Hyperfine interaction with the unpaired spin of the proton further splits the levels.

Chemistry of the molecule •HO

[edit]In order to study gas phase interstellar chemistry, it is convenient to distinguish two types of interstellar clouds: diffuse clouds, with T=30–100 K, and n=10–1000 cm−3, and dense clouds with T=10–30K and density n=104–103 cm−3. Ion-chemical routes in both dense and diffuse clouds have been established for some works (Hartquist 1990).

•HO production pathways

[edit]The •HO radical is linked with the production of H2O in molecular clouds. Studies of •HO distribution in Taurus Molecular Cloud-1 (TMC-1)[21] suggest that in dense gas, •HO is mainly formed by dissociative recombination of H3O+. Dissociative recombination is the reaction in which a molecular ion recombines with an electron and dissociates into neutral fragments. Important formation mechanisms for •HO are:

H3O+ + e− → •HO + H2 (1a) Dissociative recombination H3O+ + e− → •HO + •H + •H (1b) Dissociative recombination HCO+2 + e− → •HO + CO (2a) Dissociative recombination •O + HCO → •HO + CO (3a) Neutral-neutral H− + H3O+ → •HO + H2 + •H (4a) Ion-molecular ion neutralization

•HO destruction pathways

[edit]Experimental data on association reactions of •H and •HO suggest that radiative association involving atomic and diatomic neutral radicals may be considered as an effective mechanism for the production of small neutral molecules in the interstellar clouds.[22] The formation of O2 occurs in the gas phase via the neutral exchange reaction between •O and •HO, which is also the main sink for •HO in dense regions.[21]

We can see that atomic oxygen takes part both in the production and destruction of •HO, so the abundance of •HO depends mainly on the abundance of H+3. Then, important chemical pathways leading from •HO radicals are:

•HO + •O → O2 + •H (1A) Neutral-neutral

•HO + C+ → CO+ + •H (2A) Ion-neutral

•HO + •N → NO + •H (3A) Neutral-neutral

•HO + C → CO + •H (4A) Neutral-neutral

•HO + •H → H2O + photon (5A) Neutral-neutral

Rate constants and relative rates for important formation and destruction mechanisms

[edit]Rate constants can be derived from the UMIST Database for Astrochemistry.[23] Rate constants have the form:

The following table has the rate constants calculated for a typical temperature in a dense cloud (10 K).

| Reaction | / cm3s−1 |

|---|---|

Formation rates (rix) can be obtained using the rate constants k(T) and the abundances of the reactant species C and D:

- rix = k(T)ix[C][D]

where [Y] represents the abundance of the species Y. In this approach, abundances were taken from the 2006 UMIST database, and the values are relative to the H2 density. The following table shows rates for each pathway relative to pathway 1a (as the ratio rix/r1a) in order to compare the contributions of each to hydroxyl formation.

| r1a | r1b | r2a | r3a | r4a | r5a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Rate |

The results suggest that pathway 1a is the most prominent mode of hydroxyl formation in dense clouds, which is consistent with the report from Harju et al..[21]

The contributions of different pathways to hydroxyl destruction can be similarly compared:

| r1A | r2A | r3A | r4A | r5A | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Rate |

These results demonstrate that reaction 1A is the main hydroxyl sink in dense clouds.

Importance of interstellar •HO observations

[edit]Discoveries of the microwave spectra of a considerable number of molecules prove the existence of rather complex molecules in the interstellar clouds and provide the possibility to study dense clouds, which are obscured by the dust they contain.[24] The •HO molecule has been observed in the interstellar medium since 1963 through its 18-cm transitions.[25] In the subsequent years, •HO was observed by its rotational transitions at far-infrared wavelengths, mainly in the Orion region. Because each rotational level of •HO is split by lambda doubling, astronomers can observe a wide variety of energy states from the ground state.

•HO as a tracer of shock conditions

[edit]Very high densities are required to thermalize the rotational transitions of •HO,[26] so it is difficult to detect far-infrared emission lines from a quiescent molecular cloud. Even at H2 densities of 106 cm−3, dust must be optically thick at infrared wavelengths. But the passage of a shock wave through a molecular cloud is precisely the process which can bring the molecular gas out of equilibrium with the dust, making observations of far-infrared emission lines possible. A moderately fast shock may produce a transient raise in the •HO abundance relative to hydrogen. So, it is possible that far-infrared emission lines of •HO can be a good diagnostic of shock conditions.

In diffuse clouds

[edit]Diffuse clouds are of astronomical interest because they play a primary role in the evolution and thermodynamics of the ISM. Observation of the abundant atomic hydrogen in 21 cm has shown good signal-to-noise ratio in both emission and absorption. Nevertheless, HI observations have a fundamental difficulty when they are directed to low-mass regions of the hydrogen nucleus, such as the center part of a diffuse cloud: the thermal width of hydrogen lines are of the same order as the internal velocity structures of interest, so cloud components of various temperatures and central velocities are indistinguishable in the spectrum. Molecular line observations in principle do not suffer from these problems. Unlike HI, molecules generally have an excitation temperature Tex << Tkin, so that emission is very weak even from abundant species. CO and •HO are considered to be the most easily studied candidate molecules. CO has transitions in a region of the spectrum (wavelength < 3 mm) where there are not strong background continuum sources, but •HO has the 18 cm emission line, convenient for absorption observations.[17] Observation studies provide the most sensitive means of detection for molecules with sub-thermal excitation, and can give the opacity of the spectral line, which is a central issue to model the molecular region.

Studies based in the kinematic comparison of •HO and HI absorption lines from diffuse clouds are useful in determining their physical conditions, especially because heavier elements provide higher velocity resolution.

•HO masers

[edit]•HO masers, a type of astrophysical maser, were the first masers to be discovered in space and have been observed in more environments than any other type of maser.

In the Milky Way, •HO masers are found in stellar masers (evolved stars), interstellar masers (regions of massive star formation), or in the interface between supernova remnants and molecular material. Interstellar HO masers are often observed from molecular material surrounding ultracompact H II regions (UC H II). But there are masers associated with very young stars that have yet to create UC H II regions.[27] This class of •HO masers appears to form near the edges of very dense material, places where H2O masers form, and where total densities drop rapidly and UV radiation from young stars can dissociate H2O molecules. So, observations of •HO masers in these regions can be an important way to probe the distribution of the important H2O molecule in interstellar shocks at high spatial resolutions.

Application in water purification

[edit]Hydroxyl radicals also play a key role in the oxidative destruction of organic pollutants.[28]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The dot (•) indicates a free radical, an atom or molecule with an unpaired electron. The notations •OH and •HO are chemically identical and used interchangeably. The •HO order is often used in reaction chemistry (such as astrochemistry) to visually emphasize the roles of the hydrogen and oxygen atoms.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Hydroxyl (CHEBI:29191)". Chemical Entities of Biological Interest (ChEBI). UK: European Bioinformatics Institute.

- ^ Perrin, D. D., ed. (1982) [1969]. Ionisation Constants of Inorganic Acids and Bases in Aqueous Solution. IUPAC Chemical Data (2nd ed.). Oxford: Pergamon (published 1984). Entry 32. ISBN 0-08-029214-3. LCCN 82-16524.

- ^ Finlayson-Pitts, Barbara J.; Pitts, James N. (2000). Chemistry of the Upper and Lower Atmosphere. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-257060-5.

- ^ Forster, P.; V. Ramaswamy; P. Artaxo; T. Berntsen; R. Betts; D.W. Fahey; J. Haywood; J. Lean; D.C. Lowe; G. Myhre; J. Nganga; R. Prinn; G. Raga; M. Schulz; R. Van Dorland (2007). "Changes in Atmospheric Constituents and in Radiative Forcing" (PDF). In Solomon, S.; D. Qin; M. Manning; Z. Chen; M. Marquis; K.B. Averyt; M.Tignor; H.L. Miller (eds.). Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press.

The hydroxyl free radical (OH) is the major oxidizing chemical in the atmosphere, destroying about 3.7 Gt of trace gases, including CH4 and all HFCs and HCFCs, each year (Ehhalt, 1999).

- ^ Kincaid-Colton, Carol; Wolfgang Streit (November 1995). "The Brain's Immune System". Scientific American. 273 (5): 54–5, 58–61. Bibcode:1995SciAm.273e..54S. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1195-54. PMID 8966536.

- ^ Sies, Helmut (March 1993). "Strategies of antioxidant defense". European Journal of Biochemistry. 215 (2): 213–219. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18025.x. PMID 7688300.

- ^ a b Reiter RJ, Melchiorri D, Sewerynek E, et al. (January 1995). "A review of the evidence supporting melatonin's role as an antioxidant". J. Pineal Res. 18 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079x.1995.tb00133.x. PMID 7776173. S2CID 24184946.

- ^ Reiter RJ, Carneiro RC, Oh CS (August 1997). "Melatonin in relation to cellular antioxidative defense mechanisms". Horm. Metab. Res. 29 (8): 363–72. doi:10.1055/s-2007-979057. PMID 9288572. S2CID 22573377.

- ^ Isaksen, I.S.A.; S.B. Dalsøren (2011). "Getting a better estimate of an atmospheric radical". Science. 331 (6013): 38–39. Bibcode:2011Sci...331...38I. doi:10.1126/science.1199773. PMID 21212344. S2CID 206530807. Retrieved 2011-01-09.

- ^ Heal, M.R.; Heard, D.E.; Pilling, M.J.; Whitaker, B.J. (1995). "On the development and validation of FAGE for local measurement of tropospheric HO and HO2". Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. 52 (19): 3428–3448. Bibcode:1995JAtS...52.3428H. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1995)052<3428:OTDAVO>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0469.

- ^ Montzka, S.A.; M. Krol; E. Dlugokencky; B. Hall; P. Jöckel; J. Lelieveld (2011). "Small interannual variability of global atmospheric hydroxyl". Science. 331 (6013): 67–69. Bibcode:2011Sci...331...67M. doi:10.1126/science.1197640. PMID 21212353. S2CID 11001130. Retrieved 2011-01-09.

- ^ Dieter, N. H.; Ewen, H. I. (1964). "Radio Observations of the Interstellar OH Line at 1,667 Mc/s". Nature. 201 (4916): 279–281. Bibcode:1964Natur.201..279D. doi:10.1038/201279b0. ISSN 0028-0836. S2CID 4163406.

- ^ Robinson, B J; McGee, R X (1967). "Oh Molecules in the Interestellar Medium". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 5 (1): 183–212. Bibcode:1967ARA&A...5..183R. doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.05.090167.001151. ISSN 0066-4146.

- ^ Heiles, Carl E. (1968). "Normal OH Emission and Interstellar Dust Clouds". The Astrophysical Journal. 151: 919. Bibcode:1968ApJ...151..919H. doi:10.1086/149493. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ Rank, D. M.; Townes, C. H.; Welch, W. J. (1971). "Interstellar Molecules and Dense Clouds". Science. 174 (4014): 1083–1101. Bibcode:1971Sci...174.1083R. doi:10.1126/science.174.4014.1083. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17779392. S2CID 43499656.

- ^ Baud, B.; Wouterloot, J. G. A. (1980), "OH observations of molecular complexes in Orion and Taurus", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 90: 297, Bibcode:1980A&A....90..297B

- ^ a b Dickey JM, Crovisier J, Kazes I (May 1981). "Emission-absorption observations of •HO in diffuse interstellar clouds". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 98 (2): 271–285. Bibcode:1981A&A....98..271D.

- ^ Crutcher, R. M.; Troland, T. H.; Heiles, C. (1981). "Magnetic fields in molecular clouds - OH Zeeman observations". The Astrophysical Journal. 249: 134. Bibcode:1981ApJ...249..134C. doi:10.1086/159268. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ Storey, J. W. V.; Watson, D. M.; Townes, C. H. (1981). "Detection of interstellar OH in the far-infrared". The Astrophysical Journal. 244: L27. Bibcode:1981ApJ...244L..27S. doi:10.1086/183472. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ Baan, Willem A.; Haschick, Aubrey D.; Henkel, Christian (1989). "Molecular outflows in powerful OH megamasers". The Astrophysical Journal. 346: 680. Bibcode:1989ApJ...346..680B. doi:10.1086/168050. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ a b c Harju, J.; Winnberg, A.; Wouterloot, J. G. A. (2000), "The distribution of OH in Taurus Molecular Cloud-1", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 353: 1065, Bibcode:2000A&A...353.1065H

- ^ Field, D.; Adams, N. G.; Smith, D. (1980), "Molecular synthesis in interstellar clouds - The radiative association reaction H + OH yields H2O + h/nu/", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 192: 1, Bibcode:1980MNRAS.192....1F, doi:10.1093/mnras/192.1.1

- ^ "The UMIST Database for Astrochemistry". udfa.ajmarkwick.net. Retrieved 2023-10-27.

- ^ Rank DM, Townes CH, Welch WJ (1971-12-01). "Interstellar Molecules and Dense Clouds". Science. 174 (4014): 1083–1101. Bibcode:1971Sci...174.1083R. doi:10.1126/science.174.4014.1083. PMID 17779392. S2CID 43499656. Retrieved 2009-01-13.

- ^ Dieter NH, Ewen HI (1964-01-18). "Radio Observations of the Interstellar HO Line at 1,667 Mc/s". Nature. 201 (4916): 279–281. Bibcode:1964Natur.201..279D. doi:10.1038/201279b0. S2CID 4163406. Retrieved 2009-01-13.

- ^ Storey JW, Watson DM, Townes CH (1981-02-15). "Detection of interstellar HO in the far-infrared". Astrophysical Journal, Part 2 - Letters to the Editor. 244: L27 – L30. Bibcode:1981ApJ...244L..27S. doi:10.1086/183472.

- ^ Argon AL, Reid MJ, Menten KM (August 2003). "A class of interstellar •HO masers associated with protostellar outflows". The Astrophysical Journal. 593 (2): 925–930. arXiv:astro-ph/0304565. Bibcode:2003ApJ...593..925A. doi:10.1086/376592.

- ^ The Conversation (Spanish Edition): The material that rays are made of can help us purify water and deal with drought Published: March 21, 2024 22:42 CET

- Downes A, Blunt TP (1879). "The effect of sunlight upon hydrogen peroxide". Nature. 20 (517): 521. Bibcode:1879Natur..20Q.521.. doi:10.1038/020521a0.

External links

[edit]Hydroxyl radical

View on GrokipediaFundamental Properties

Molecular Structure and Bonding

The hydroxyl radical (•OH) is a diatomic species comprising one oxygen atom covalently bonded to one hydrogen atom, with an unpaired electron localized primarily on the oxygen atom, resulting in a total of seven valence electrons. This configuration imparts paramagnetic properties and high reactivity. The molecule adopts a linear geometry, belonging to the C_{∞v} point group symmetry.[8] The equilibrium O-H bond length (r_e) measures 0.970 Å, as determined from spectroscopic data.[8] The rotational constant B_e is 18.91080 cm⁻¹, consistent with this bond length and the reduced masses of the atoms.[8] The permanent electric dipole moment is 1.668 D, oriented with the negative pole at oxygen, reflecting the electronegativity difference.[8] In its ground electronic state, X ^2Π, the hydroxyl radical arises from the molecular orbital configuration (1σ)^2 (2σ)^2 (3σ)^2 (1π)^3, where the 3σ orbital forms the primary σ-bond through overlap of oxygen 2p_σ and hydrogen 1s atomic orbitals, while the singly occupied 1π orbital (degenerate π orbitals with three electrons) contributes minimal bonding character.[9] The bond dissociation energy D_0 for dissociation to ground-state atoms O(^3P) + H(^2S) is 35593 cm⁻¹ (425.4 kJ/mol), indicating a strong yet single-bond-like interaction weaker than the initial O-H bond in H_2O due to diminished orbital overlap and electron repulsion in the radical.[10] The harmonic vibrational frequency ω_e of 3737.761 cm⁻¹ further corroborates the bond stiffness.[8]Spectroscopic and Physical Characteristics

The hydroxyl radical resides in the X ^2\Pi ground electronic state, featuring an unpaired electron in a π antibonding orbital, which imparts paramagnetism and reactivity. This state splits into two spin-orbit components due to the large spin-orbit coupling constant A ≈ -123.5 cm^{-1}: the lower-energy ^2\Pi_{3/2} substate (ground) and the higher-energy ^2\Pi_{1/2} substate, separated by 123.5 cm^{-1}.[11] The equilibrium O-H bond length is 0.970 Å, reflecting strong single-bond character with partial double-bond influence from the radical electron.[8] The bond dissociation energy D_0 for OH → O(³P) + H(²S) is 428 kJ/mol at 0 K, indicating robust stability relative to dissociation products.[12] The permanent electric dipole moment is 1.668 D, enabling strong transitions in microwave and far-infrared spectroscopy, including pure rotational spectra within the ^2\Pi state. Rotational constants for the ground vibrational level are B ≈ 18.911 cm^{-1} for ^2\Pi_{3/2}, with centrifugal distortion D ≈ 0.053 cm^{-1}, facilitating precise rotational analysis despite Lambda-doubling splittings on the order of 10^{-3} cm^{-1} in low-J levels.[8][11] Vibrational spectroscopy reveals a fundamental band origin at 3570.5 cm^{-1} (ν=0 to ν=1), with harmonic frequency ω_e = 3738 cm^{-1} and anharmonicity ω_e x_e ≈ 84.9 cm^{-1}, yielding zero-point energy of 1784.8 cm^{-1}.[8] Electronic transitions, notably the A ^2Σ^+ ← X ^2\Pi system near 308 nm, underpin laser-induced fluorescence detection, with the A-state lifetime ≈ 0.7 μs.[13] Thermodynamically, the standard enthalpy of formation ΔH_f°(298 K) is 37.36 kJ/mol, entropy S°(298 K) is 183.74 J mol^{-1} K^{-1}, and constant-pressure heat capacity C_p(298 K) is 29.89 J mol^{-1} K^{-1}, consistent with a diatomic radical's translational and rotational degrees of freedom dominating at room temperature.[8] These properties derive from high-resolution microwave, infrared, and ultraviolet spectra, with uncertainties typically below 0.1% for constants measured via techniques like laser magnetic resonance.[14]| Property | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Bond length (r_e) | 0.970 | Å |

| Dipole moment (μ) | 1.668 | D |

| Rotational constant (B) | 18.91080 | cm^{-1} |

| Vibrational harmonic frequency (ω_e) | 3738 | cm^{-1} |

| Bond dissociation energy (D_0) | 428 | kJ mol^{-1} |

Reactivity and Generation

Chemical Reactivity Profile

The hydroxyl radical (•OH) is highly reactive owing to its unpaired electron and electrophilic character, enabling rapid reactions with a broad array of substrates under ambient conditions. Primary reaction pathways include hydrogen atom abstraction from saturated hydrocarbons, carbonyl compounds, and other hydrogen donors, as well as addition to π-bonds in alkenes and aromatics; these dominate its gas-phase chemistry in the troposphere and combustion environments.[15][16] Abstraction reactions generally exhibit activation energies of 2–5 kcal/mol, while additions are often barrierless or near-diffusion-limited, with overall rate constants spanning 10^{-18} to 10^{-10} cm³ molecule⁻¹ s⁻¹ at 298 K depending on the substrate.[17][1] In hydrogen abstraction, •OH + RH → H₂O + R•, the exothermicity (driven by the ~119 kcal/mol O–H bond strength in water) favors radical formation, with selectivity correlating to C–H bond dissociation energies and resulting radical stabilities: tertiary > secondary > primary > vinylic/acetylenic. For alkanes, relative rate constants per hydrogen atom increase with branching; e.g., the reaction with ethane proceeds ~10 times slower than with propane at the secondary site.[17][16] Absolute rates for methane abstraction are notably slow (k ≈ 6 × 10^{-15} cm³ molecule⁻¹ s⁻¹), limiting its direct oxidation, whereas branched alkanes approach 10^{-11}–10^{-10}, nearing collision limits.[18] This pathway initiates chain oxidation of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), yielding peroxy radicals that propagate tropospheric oxidant cycles.[19] Addition reactions predominate for unsaturated species, where •OH inserts across double bonds to form β-hydroxyalkyl radicals, often without significant barriers; e.g., the rate for ethylene exceeds that for ethane by orders of magnitude due to π-electron attack.[1] For aromatics like benzene or toluene, initial addition to the ring competes with methyl H-abstraction in toluene (abstraction ~20–30% of total at 298 K), with addition channels leading to ring-retaining or opening products under low-NOₓ conditions.[20] These electrophilic additions exhibit negative temperature dependences, enhancing reactivity at lower temperatures relevant to the upper troposphere.[21] Beyond organics, •OH oxidizes CO via •OH + CO (→ H + CO₂), a pressure-dependent association-dissociation process with k ≈ 10^{-13} cm³ molecule⁻¹ s⁻¹ at 1 atm and 298 K, crucial for CO removal in air masses lacking hydrocarbons. Reactions with NOx are slower; e.g., •OH + NO₂ + M → HNO₃ + M (k ≈ 10^{-11} cm³ molecule⁻¹ s⁻¹), contributing to acid rain precursors but secondary to organic sinks. Electron transfer occurs rarely, mainly with strong reductants, underscoring •OH's preference for covalent mechanisms over ionic ones in neutral environments.[18][18] Overall, •OH's non-selective yet kinetically tunable reactivity positions it as a versatile oxidant, with lifetimes of milliseconds to seconds in polluted air dictated by total sink abundances.[19]Laboratory Generation Methods

In gas-phase laboratory studies, hydroxyl radicals are frequently generated using discharge-flow techniques, where hydrogen atoms produced via microwave or radio-frequency discharge in a H₂/Ar mixture react with nitrogen dioxide to yield OH: H + NO₂ → OH + NO.[1] This method allows controlled production in flow tubes for kinetic measurements, with typical OH concentrations on the order of 10^{11}–10^{12} molecules cm^{-3}.[1] Flash photolysis represents another primary approach, employing pulsed lasers (e.g., ArF excimer at 193 nm) or flash lamps to dissociate precursors such as hydrogen peroxide: H₂O₂ + hν → 2•OH, or nitrous acid: HONO + hν → OH + NO.[1] These techniques enable time-resolved spectroscopy, generating transient OH bursts with lifetimes determined by subsequent reactions, often in the microsecond to millisecond range under low-pressure conditions.[1] In aqueous environments, the Fenton reaction provides a standard route: Fe^{2+} + H₂O₂ → Fe^{3+} + OH^- + •OH, typically initiated at near-neutral pH with micromolar iron concentrations and millimolar H₂O₂.[22] Variations include photo-Fenton processes, enhancing yield via UV-induced Fe^{3+} reduction, with quantum yields up to 0.1–0.5 depending on wavelength and ligands.[23] Electrochemical methods, such as anodic oxidation of water or cathodic H₂O₂ reduction, also produce •OH at electrodes like boron-doped diamond, with rates scalable to 10^{-6}–10^{-5} M s^{-1}.[24] Specialized techniques include radiofrequency or DC discharges directly in water vapor or humid gases, yielding OH via electron-impact dissociation: H₂O + e^- → •OH + H + e^-, used in plasma chemistry with production rates exceeding 10^{16} molecules s^{-1} in pulsed systems.[25] For supersonic molecular beams, chemical reactions like O(³P) + H₂ → OH + H facilitate cooled, vibrationally selected OH generation.Detection Techniques

Direct detection of the hydroxyl radical (OH) in gas-phase environments, such as laboratory reactors or the atmosphere, predominantly relies on spectroscopic techniques due to the radical's transient nature and low concentrations, often below 10^7 molecules cm^{-3}. Laser-induced fluorescence (LIF) is a cornerstone method, wherein OH is excited by a tunable laser at specific rovibronic transitions, typically around 308 nm (A²Σ⁺ ← X²Π), and the resulting fluorescence is collected and quantified using photomultiplier tubes or similar detectors. This approach achieves detection limits as low as 10^5–10^6 molecules cm^{-3} with integration times of minutes, enabling real-time monitoring; calibration often involves photolysis of water vapor at 185 nm to generate known OH quantities, with uncertainties around ±18%.[26] A variant, the Fluorescence Assay by Gas Expansion (FAGE), expands ambient air into a low-pressure chamber to reduce quenching and enhance signal-to-noise, achieving sensitivities of approximately 6.5 × 10^5 molecules cm^{-3} for indoor or atmospheric applications.[27] Other spectroscopic methods include differential optical absorption spectroscopy (DOAS), which measures OH absorption features at 308 nm along multi-kilometer light paths, offering sensitivities around 7.3 × 10^5 molecules cm^{-3} but requiring large setups unsuitable for confined spaces.[27] Chemical ionization mass spectrometry (CIMS) provides an indirect route by converting OH to detectable ions, such as through reaction with SO₂ to form H₂SO₄ clusters ionized via NO₃⁻ reagents, with isotopic labeling (e.g., ³⁴SO₂) for specificity; this method suits complex matrices like indoor air but demands precise calibration to account for interferences.[27] Resonance fluorescence, historically used in upper atmospheric rocket-borne instruments, excites OH and detects prompt emission, though it is less common today due to LIF's superior versatility.[28] In solution or biological contexts, indirect trapping methods predominate, as direct gas-phase spectroscopy is impractical. Electron spin resonance (ESR) spectroscopy captures OH via spin traps like 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO), forming stable nitroxide adducts detectable by their magnetic resonance signals; this direct radical identification is highly specific but limited by adduct instability and the need for cryogenic preservation, with applications mainly in vitro.[29] High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) quantifies OH-induced products from traps such as salicylic acid (yielding dihydroxybenzoic acids) or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, producing formaldehyde), offering sensitivities down to 10^{-9}–10^{-11} g but involving complex separation of intermediates and potential overestimation from competing radicals.[29] Fluorescence-based probes, like coumarin derivatives, generate fluorescent adducts upon OH reaction, providing high sensitivity (e.g., limits of 0.04 μmol/L) and simplicity, though specificity suffers from cross-reactivity with other oxidants.[29] Spectrophotometric assays monitor absorbance changes in probes like methylene blue, which decolorizes upon oxidation, but these are less sensitive and prone to indirect interferences compared to ESR.[29]Atmospheric Role

Production and Destruction Pathways

The primary production pathway for the hydroxyl radical (OH) in the daytime troposphere is the photolysis of ozone (O₃) by ultraviolet radiation with wavelengths shorter than 320 nm, yielding electronically excited oxygen atoms that react with water vapor: O₃ + hν → O(¹D) + O₂, followed by O(¹D) + H₂O → 2 OH.[30] This two-step process accounts for the majority of tropospheric OH formation globally, with its efficiency depending on solar zenith angle, ozone column density, and water vapor concentration.[31] In regions with low water vapor, such as the upper troposphere, the reaction of O(¹D) with H₂ instead contributes: O(¹D) + H₂ → H₂O + OH.[32] Secondary production occurs via photolysis of nitrous acid (HONO), prevalent in urban and polluted environments: HONO + hν → OH + NO, where HONO forms from heterogeneous reactions of NO₂ on surfaces.[33] Reactions of ozone with alkenes, such as through addition across carbon-carbon double bonds, also generate OH, particularly in vegetated or biogenic emission areas, with yields up to 0.3–0.6 per reaction depending on the alkene structure.[34] Radical recycling, including HO₂ + NO → OH + NO₂ and HO₂ + O₃ → OH + 2 O₂, sustains OH levels but originates from primary photolytic sources.[30] Destruction of OH primarily involves its high reactivity with trace gases, initiating oxidation chains that propagate but ultimately terminate the radical cycle. The dominant sinks include reactions with carbon monoxide (OH + CO → H + CO₂, followed by H + O₂ + M → HO₂ + M, rate constant ~1.5 × 10⁻¹³ cm³ molecule⁻¹ s⁻¹ at 298 K) and methane (OH + CH₄ → CH₃ + H₂O, rate constant ~6.4 × 10⁻¹⁵ cm³ molecule⁻¹ s⁻¹), which together account for over 50% of global OH loss.[3] In polluted, high-NOₓ environments, OH + NO₂ + M → HNO₃ + M serves as a permanent sink, forming nitric acid and removing nitrogen oxides from the radical pool.[33] In clean, low-NOₓ regions, destruction proceeds via peroxy radical self-reactions, such as HO₂ + HO₂ → H₂O₂ + O₂ (rate constant ~2.0 × 10⁻¹² cm³ molecule⁻¹ s⁻¹, increasing with temperature and [H₂O]) or HO₂ + RO₂ → products, leading to reservoir species like hydrogen peroxide.[35] OH reactions with non-methane hydrocarbons, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and sulfur dioxide (e.g., OH + SO₂ → HOSO₂, rate constant ~1.0 × 10⁻¹² cm³ molecule⁻¹ s⁻¹) contribute additional sinks, with VOC oxidation dominating in forested areas.[36] These pathways ensure OH's short lifetime of seconds to minutes, balancing production to maintain steady-state concentrations around 10⁶ molecules cm⁻³ daytime average.[30]Kinetic Parameters and Relative Rates

The rate constants for bimolecular reactions of the hydroxyl radical (OH) with atmospheric trace gases, expressed in units of cm³ molecule⁻¹ s⁻¹, span several orders of magnitude at 298 K, from ~10^{-18} for stable species like N₂O to ~10^{-10} for highly reactive unsaturated hydrocarbons, reflecting differences in reaction mechanisms such as hydrogen abstraction, addition, or electron transfer. These parameters, derived from pulsed laser photolysis, discharge flow, and relative rate techniques, are critically evaluated in compilations like NASA JPL Publication 19-5 (2019) and IUPAC kinetic data sheets, prioritizing direct measurements over theoretical estimates where discrepancies arise. Uncertainties typically range from 5-20% for well-studied reactions, higher for complex organics due to conformational effects and pressure dependencies. Temperature dependence follows the modified Arrhenius form , with parameters fitted to experimental data over 200-400 K; for endothermic abstractions, γ > 0 implies activation barriers, while β accounts for curvature from quantum tunneling or complex formation at low T. For instance, the reaction OH + CO → H + CO₂ exhibits strong non-Arrhenius behavior due to pressure-dependent stabilization of the HOCO intermediate, with k(298 K) ≈ 2.4 × 10^{-13} cm³ molecule⁻¹ s⁻¹ in air, increasing at lower temperatures contrary to simple Arrhenius predictions.[37] Relative rates, often measured against reference reactions like OH + CH₃CCl₃ (k_ref ≈ 5.9 × 10^{-15} cm³ molecule⁻¹ s⁻¹), highlight selectivity: saturated hydrocarbons react via abstraction with k ~10^{-12} to 10^{-14}, yielding lifetimes of weeks to months at typical [OH] ≈ 10^6 molecules cm⁻³, whereas alkenes and aromatics react 10-10³ times faster via addition, dominating urban OH sinks. [17]| Reactant | k(298 K) (×10^{-12} cm³ molecule⁻¹ s⁻¹) | Mechanism | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CH₄ | 0.0064 | Abstraction | Low reactivity; global sink |

| CO | 0.24 | Abstraction/addition | Pressure-dependent[37] |

| C₂H₄ | 3.0 | Addition | High reactivity benchmark |

| NO₂ | ~0.001 (low-pressure limit, termolecular) | Association | Forms HNO₃; bath gas enhanced |