Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pori (Finnish: [ˈpori]; Swedish: Björneborg [bjœːrneˈborj] ⓘ; Latin: Arctopolis)[8] is a city in Finland and the regional capital of Satakunta. It is located on the west coast of the country, on the Gulf of Bothnia. The population of Pori is approximately 83,000, while the sub-region has a population of approximately 128,000. It is the 10th most populous municipality in Finland, and the eighth most populous urban area in the country.

Key Information

Pori is located some 10 kilometres (6 mi) from the Gulf of Bothnia, on the estuary of the Kokemäki River, 110 kilometres (68 mi) west of Tampere, 140 kilometres (87 mi) north of Turku and 241 kilometres (150 mi) north-west of Helsinki, the capital of Finland. Pori covers an area of 2,062.00 square kilometres (796.14 sq mi) of which 870.01 km2 (335.91 sq mi) is water.[3] The population density is 71.93/km2 (186.3/sq mi).

Pori was established in 1558 by Duke John, who later became King John III of Sweden.[1][2] The municipality is unilingually Finnish. Pori was also once one of the main cities with Turku in the former Turku and Pori Province (1634–1997). The neighboring municipalities are Eurajoki, Kankaanpää, Kokemäki, Merikarvia, Nakkila, Pomarkku, Sastamala, Siikainen and Ulvila.

Pori is especially known nationwide for its Jazz Festival, Yyteri's sandy beaches, Kirjurinluoto, Porin Ässät ice hockey club, FC Jazz football club, which won two championships in the Veikkausliiga in the 1990s, and Pori Theater, which is the first Finnish-language theater in Finnish history.[9] Pori is also known for its local street food called porilainen.[10] During its history, the city of Pori has burned down nine times; only Oulu has burned more often, as many as ten times.[11][12][13][14][15] The current coat of arms of Pori was confirmed for use by President P. E. Svinhufvud on December 11, 1931,[16] and was later redrawn by Olof Eriksson. The city council reaffirmed the use of the redrawn version on October 27, 1959. The bear motif of the coat of arms comes from a 17th century seal and the motto, deus protector noster or "God is our protector", is also on the coat of arms of the city's founder, Duke John.[1]

Name

[edit]The Finnish name Pori comes from the -borg part (meaning citadel, fortress or castle) of the original name in Swedish with a Fennicised pronunciation.[17] The whole Swedish name Björneborg literally means Bear Fortress or Bear Castle (Finnish: Karhulinna), and the Latin-Greek Arctopolis means Bear City (Finnish: Karhukaupunki).[18][19][20]

History

[edit]Early years

[edit]City of Pori was established on March 8, 1558 by Duke John of Finland (Finnish: Juhana III or Juhana-herttua) who was later known as John III of Sweden.[2] It was a successor to the medieval towns of Teljä (Kokemäki) and Ulvila. Sailing the Kokemäki river had become more and more difficult since the 14th century due to the post-glacial rebound. The importance of Kokemäki and Ulvila began to decline as the ships could no longer navigate the river. In the 16th century the situation had become so bad that Duke John decided to establish a new harbour and market town closer to the sea.

The Bourgeoisie of Ulvila were ordered to migrate to the newly founded city and on 8 March 1558 John III gave the charter of Pori, which read: "Because we have seen that it would be best to build a strong market town alongside the sea, and because we cannot find anywhere suitable for fortifying in Ulvila, we have chosen another location at Pori."[21]

At the beginning Pori had around 300 involuntary residents. However, they soon recognized the advantages of their new location, which offered opportunities for profitable trading, among other things. Ship building has been important since the beginning of history of Pori. Shipyard started by the river in 1572 and it worked until the early 20th century. The biggest ship probably ever built in Pori was "Porin Kraveli," completed in 1583.

Greater Wrath and Crimean War

[edit]

During the Greater Wrath of 1713, Pori was occupied by Russian troops. Eight Russian regiments spent four months in town from September 1713 to January 1714 vandalizing and demolishing the city. Some of the wealthiest residents vanished, they were probably imprisoned and taken to Russia. Wind mills and storage houses were burnt. Most of the oxen and horses and more than 400 boats were lost. The Russian invasion of Finland continued another seven years. It meant great financial loss for Pori as the foreign trade was completely finished. After the Greater Wrath, Pori lost its staple rights and the city went into deep depression. A new "golden age" for Pori started in 1765 as the city got back the staple rights for foreign trade.[22]

As the Crimean War broke out in 1853, Pori was attacked by both the French Navy and British Navy in 1855 during the Åland War. The French frigate D'Assos made the first attempt on July and managed to catch one ship outside the Isokari island before they sailed further north. Another attack was made by the British fleet on 9 August. Mayor Klaus Wahlberg negotiated a deal with the enemy and the city was saved. Two sailing ships and 17 smaller boats along with some other properties were given to the British.[23] The activities of the people of Pori were considered shameful and according to some information, Lieutenant General Alexander von Wendt would have later demoted the officer who had retreated from Luotsinmäki to sergeant during a review held at the Pori market square.[24]

City fires

[edit]

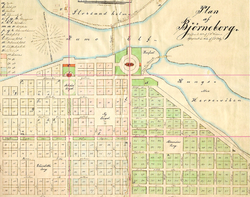

As most of its houses were made of wood, Pori has had its share of fires. The town has burned down and been rebuilt nine times.[25] The city was first destroyed by fire in 1571 and the last major fire was in 1852. More than 75 per cent of the city was destroyed in 1852 and most of the residents became homeless. Only a few buildings, such as the Town Hall, were saved. The Great Fire of 1852 was one of the worst disasters in Finland so far.[26] The new city plan and the shape of the present old town was designed by Swedish architect C. T. von Chiewitz. The newly completed buildings, such as the Pori Theatre and Hotel Otava are historically and culturally important. Four esplanades, which are wider than the other streets, divided the new city center in four parts.

Finnish Civil War and World War II

[edit]During the 1918 Finnish Civil War, Pori was a part of the Finnish Socialist Workers' Republic. The city was not on the direct war zone but some terror was made by both sides. The best known incident was the execution of 11 Whites at the schoolyard of Pori Lyceum.

During World War II, Pori was bombed four times by the Soviet Airforce in 1939–1940. The worst bombing occurred on 2 February 1940 as 21 people were killed. Most of the bombs were aimed to the harbour area instead of the city itself.[27] From 1942 to 1944 Pori Airport served as an air depot for the Jagdgeschwader 5 of German Luftwaffe.[28] Pori air depot was known as "Feldluftpark Pori" and it was one of the major German air depots in Northern Europe. In September 1944, Germans left the airport and destroyed many of their facilities with explosives.[29] One German-built hangar is still used today. Total of 319 Soviet Red Army prisoners of war died in Pori as they were used as a forced labor by the Germans. Soviet soldiers are buried at Vähärauma district in the western part of the city.[30]

Geography

[edit]River and delta

[edit]The geological uplift after the last ice age has been relatively high at the mouth of the Kokemäenjoki river. When the city was established in 1558, it was situated on the shore of Pori bay. Because of this uplift the delta of the river now begins in front of the city. The recreation area of Kirjurinluoto is actually on an island connected with bridges to the mainland. Pori National Urban Park preserves the story of the phases of development of the town born at the mouth of the river Kokemäenjoki.

Climate

[edit]Pori has a humid continental climate (Dfb), with moderation from the Gulf of Bothnia helping to keep September above the 10 °C (50 °F) isotherm, and is amongst the northern extent of that climate in Finland. Winters are long, and cold, but are notably shorter and warmer than in the Northern parts of Finland due to the marine effect and location by the Bothnian Sea. The temperatures measured in the city center are slightly higher on average due to the urban heat island effect. Summers are relatively warm. The highest ever recorded temperature in this weather station was 33.3 °C (91.9 °F), on 13 July 2010 and the lowest official temperature ever recorded was -36.8 °C (-34.2 °F), on 3 February 1966. Visiting the famous "Yyteri" beach is arguably the best pastime thing to do in Pori on warm summer days. In fact, it gathers the most visitors out of any other beach in Finland on summers.

| Climate data for Pori Airport, records 1960 - present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 9.6 (49.3) |

9.5 (49.1) |

14.5 (58.1) |

24.5 (76.1) |

29.4 (84.9) |

32.9 (91.2) |

33.3 (91.9) |

33.2 (91.8) |

28.2 (82.8) |

20.1 (68.2) |

14.7 (58.5) |

11.3 (52.3) |

33.3 (91.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −1.2 (29.8) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

2.4 (36.3) |

8.7 (47.7) |

15.0 (59.0) |

18.9 (66.0) |

21.8 (71.2) |

20.6 (69.1) |

15.3 (59.5) |

8.5 (47.3) |

3.3 (37.9) |

0.5 (32.9) |

9.4 (48.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −4.0 (24.8) |

−4.6 (23.7) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

4.0 (39.2) |

9.7 (49.5) |

14.1 (57.4) |

17.1 (62.8) |

15.8 (60.4) |

11.0 (51.8) |

5.4 (41.7) |

1.2 (34.2) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

5.6 (42.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −7.0 (19.4) |

−7.6 (18.3) |

−4.9 (23.2) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

4.3 (39.7) |

9.0 (48.2) |

12.1 (53.8) |

11.0 (51.8) |

6.8 (44.2) |

2.3 (36.1) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

−4.8 (23.4) |

1.6 (34.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −35.7 (−32.3) |

−36.8 (−34.2) |

−27.1 (−16.8) |

−16.3 (2.7) |

−5.8 (21.6) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

1.7 (35.1) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−7.3 (18.9) |

−16.7 (1.9) |

−22.5 (−8.5) |

−35.4 (−31.7) |

−36.8 (−34.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 44 (1.7) |

28 (1.1) |

29 (1.1) |

30 (1.2) |

35 (1.4) |

54 (2.1) |

67 (2.6) |

71 (2.8) |

56 (2.2) |

66 (2.6) |

55 (2.2) |

51 (2.0) |

586 (23.1) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 14 (5.5) |

14 (5.5) |

4 (1.6) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

3 (1.2) |

8 (3.1) |

43 (16.9) |

| Average rainy days | 18 | 13 | 12 | 9 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 14 | 13 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 159 |

| Source: Climatological statistics of Finland 1981–2010[31]

Source 2: Foreca | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]Population

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 13,482 | — |

| 1910 | 13,981 | +3.7% |

| 1920 | 13,928 | −0.4% |

| 1930 | 15,966 | +14.6% |

| 1940 | 18,230 | +14.2% |

| 1950 | 43,306 | +137.6% |

| 1960 | 52,542 | +21.3% |

| 1970 | 72,938 | +38.8% |

| 1980 | 78,405 | +7.5% |

| 1985 | 78,376 | −0.0% |

| Source: City of Pori, Yearbook 2018[32][33] | ||

The city of Pori has 83,157 inhabitants, making it the 10th most populous municipality in Finland. The Pori region has 128,095 inhabitants, making it the eight most populous region in Finland. In Pori, 6% of the population has a foreign background, which is below to the national average.[34]

The significant population increase in 1950 was the result of annexing nearby areas. Population peaked in the mid-1970s when it was over 80 000. After that, the population declined, and in recent years has remained steady at just over 83 000. After the annex of the neighbouring municipality Noormarkku in 2010 and Lavia in 2015 the population rose to the current level. In 1952 Pori was the fifth largest city in Finland after Helsinki, Turku, Tampere and Lahti.[35]

| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1990 | |

| 1995 | |

| 2000 | |

| 2005 | |

| 2010 | |

| 2015 | |

| 2020 |

Languages

[edit]mother tongue (2024)[34]

- Finnish (93.6%)

- Russian (1.00%)

- Ukrainian (0.60%)

- Swedish (0.60%)

- Arabic (0.40%)

- English (0.40%)

- Estonian (0.30%)

- Other (3.10%)

Pori is a monolingual Finnish-speaking municipality. As of 2024[update], the majority of the population, 77,974 persons (93.6%), spoke Finnish as their first language. In addition, the number of Swedish speakers was 467 persons (0.6%) of the population. Foreign languages were spoken by 5.8% of the population.[34] As English and Swedish are compulsory school subjects, functional bilingualism or trilingualism acquired through language studies is not uncommon.

At least 40 different languages are spoken in Pori. The most commonly spoken foreign languages are Russian (1.0%), Ukrainian (0.6%), Arabic (0.4%) and English (0.4%).[34]

Immigration

[edit]| Population by country of birth (2024)[34] | ||

| Nationality | Population | % |

|---|---|---|

| 78,129 | 93.8 | |

| 651 | 0.8 | |

| 440 | 0.5 | |

| 309 | 0.4 | |

| 271 | 0.3 | |

| 254 | 0.3 | |

| 247 | 0.3 | |

| 196 | 0.2 | |

| 190 | 0.2 | |

| 176 | 0.2 | |

| 174 | 0.2 | |

| Other | 2,268 | 2.7 |

As of 2024[update], there were 4,935 persons with a migrant background living in Pori, or 6% of the population.[note 1] The number of residents who were born abroad was 5,176, or 6% of the population. The number of persons with foreign citizenship living in Pori was 3,723. Most foreign-born citizens came from the former Soviet Union, Sweden, Ukraine, Russia, Sri Lanka and Estonia.[34] There is a Swedish School and a Swedish Culture Club that are aimed at serving the Finland-Swedish minority in the Satakunta region.

The relative share of immigrants in Pori's population is below to the national average. However, the city's new residents are increasingly of foreign origin. This will increase the proportion of foreign residents in the coming years.

Religion

[edit]In 2023, the Evangelical Lutheran Church was the largest religious group with 68.3% of the population of Pori. Other religious groups accounted for 1.9% of the population. 29.9% of the population had no religious affiliation.[38]

Politics

[edit]The largest parties in Pori are Social Democratic Party and National Coalition Party. In 2021 municipal elections the parties gained 21.5% and 20.4% of vote, respectively.[39] The mayor of Pori is Lauri Inna, who was elected to run the city in 2022 after the former mayor, Aino-Maija Luukkonen, retired from the post.[40]

Transport

[edit]

Pori railway station and bus station are located in the city center. Since the Pori station is a terminal train station, railway traffic is quite moderate. Pori is only connected to Tampere with 13 daily departures by the Tampere–Pori railway. Bus traffic is very busy instead. Pori has more than 100 intercity buses with major Finnish cities Helsinki, Turku and Tampere as well as smaller places like Rauma and Vaasa. Public transport is managed by the city owned bus company Porin Linjat. It has also service to nearby municipalities. The most significant highways from Pori to other cities are Highway 2 to Helsinki, Highway 8 (to south) to Turku and (to north) to Vaasa, Highway 11 to Tampere and Highway 23 to Jyväskylä.

Pori Airport has connections to Helsinki Airport.[41]

Port of Pori is specialized on bulk cargo. It has liner service to several Northern European ports. In October 2013 Pori was the destination of MS Nordic Orion, the first commercial cargo ship ever to transit the Northwest Passage. She was carrying a cargo of coking coal from Port Metro Vancouver, Canada.[42]

Economy

[edit]

There were 35,216 jobs in 2014. 7,548 residents of other municipalities worked in Pori and 5,710 Pori employees outside the city in 2014. The unemployment rate was 10.7% in May 2018.[43]

The largest employer in Pori in terms of the number of employees in 2016 was the city of Pori with more than 5,000 employees.[44] Other major employers include Technip and Satakunta University of Applied Sciences.[44]

Education

[edit]

Pori is the home of 28 comprehensive schools and 7 gymnasiums including English, French and German classes as well as the Swedish-speaking Björnebogs svenska samskola, Rudolf Steiner School and a Christian school.[45] First Trivial school in Pori was founded in 1641. Today it is succeeded by Pori Lyceum established 1879.[46] Vocational education is given in five institutes[45] including the music school Palmgren Conservatory[47] and Finnish Aviation Academy[48] which is owned by the state of Finland and Finnish flag carrier airline Finnair.

Highest grades of education in Pori are the Satakunta University of Applied Sciences and University Consortium of Pori (UCPori).

Culture

[edit]In 1987, the Art Association NYTE, an artist group and art association is founded.[49]

Pori Jazz Festival

[edit]Pori is widely known for its international jazz music festival, established in 1966. Today Pori Jazz is one of the major jazz festivals in Europe as well as one of the largest culture events in Finland. The nine-day festival is held annually in July.[50] Many renowned musicians have played the festival over the years, including artists like B. B. King, Ray Charles, Miles Davis, Keith Jarrett, Bob Dylan, Elton John, Kanye West and Santana.[51]

Concert arenas are located around the city. Main venue is Kirjurinluoto Arena, which is an open-air concert park holding an audience more than 30,000. The arena has hosted also many other events like Sonisphere Festival in 2009 and 2010. SuomiAreena in an international public debate forum held simultaneously with Pori Jazz.[52]

Theatre and music

[edit]

Pori is considered to be the birthplace of Finnish-language theatre[9] as the Finnish National Theatre gave its first performance at Hotel Otava on October 13, 1872. Pori Theatre is a municipal theatre established in 1931 as a merger of two local stages. Theatre building was completed in 1884. Another professional theatre in Pori is Rakastajat-teatteri. It is also hosting an annual festival for independent theatre groups.[53] Pori is a home for several amateur and youth theatres and the Kirjurinluoto Summer Theatre that presents open-air productions in summertime.

Pori Symphony Orchestra was established 1938 and it is today known as Pori Sinfonietta. The orchestra performs in 1999 built Promenadikeskus music hall. The first city orchestra was founded in 1877. In its early years the orchestra was mostly performing light orchestral music and its musicians were German. The very first symphony concert was played in 1902. Most famous classical composer from Pori is Selim Palmgren, even called as "The Finnish Chopin". Pori Opera was established in 1976. It performs a yearly production together with Pori Sinfonietta and Pori Opera Choir. In 2004 they recorded Kung Karls jakt which is the first opera composed in Finland.

Pori is known as one of the birthplaces of Finnish rock music, where the bands Dingo and Yö, among others, originate.[54] With this, the concept of "Porirock" was born to define the music made by rock musicians from Pori.[55]

Museums

[edit]Satakunta Museum is a historical museum established 1888. It is one of the oldest historical museums in Finland and presents the history of Satakunta province and the city of Pori. Museum building was completed in 1973.[56] Pori Art Museum is a museum of contemporary and modern art. It was opened in 1979. Museum is based on the collections of local art collector and patronage Maire Gullichsen. Pori Art Museum is located in a former weigh house originally built in 1860.[57] Other museums in Pori are the Rosenlew Museum which is presenting the industrial heritage of Rosenlew Company[58] and the natural history museum Luontotalo Arkki.[59] Toivo is the renovation center of Satakunta Museum. It presents traditional ways of restoring wooden houses with an exhibition of typical early 1900s home.[60]

Sport

[edit]

Major team sports in Pori are ice hockey and football. Pori is especially known for its popular hockey team Ässät which is a three-time Finnish Champion, most recently in 2013.[61] Their victory parade gathered some 20,000 people to the Pori market square.[62] Local top football side FC Jazz have won the Finnish premier league Veikkausliiga in 1993 and 1996. The club has also competed in several UEFA competitions. As of 2024[update], FC Jazz plays in the third tier Ykkönen.[63] Jazz's main rival and other local football team is Musan Salama which plays in fifth tier, Kolmonen.

Other popular team sports in Pori are bandy and pesäpallo, the Finnish version of baseball. Women's pesäpallo team Pesäkarhut and bandy side Narukerä are both playing in the premier divisions. Pori has also men's and women's lower division teams in almost all major team sports, including clubs like Pori Futsal (futsal), Bears (American football), Pori Rugby (rugby union) and FBT Karhut United (floorball). The oldest sportsclub in Finland, Segelföreningen i Björneborg, was established 1856 in Pori.[64]

The biggest sports club in Pori is Liikuntaseura Pori, which offers multiple sports including gymnastics, TeamGym and cheerleading.

Sporting facilities

[edit]12,300 seated Pori Stadium, which is primarily used for football, is one of the largest multi-purpose stadiums in Finland. It is the home ground for FC Jazz and NiceFutis. The stadium has also been a venue for two Finland internationals. Pori Stadium has hosted the Finnish Championships in Athletics three times and was the venue of 2015 games.

Stadium is located at the Isomäki sports center. The area includes several other facilities like the Isomäki Areena ice hockey arena for 6,150 spectators, an indoor football arena, a rink for bandy and skating, tennis courts and an outdoor swimming stadium. Pori Racetrack is one of the major horse racing venues in Finland.

The motorcycle speedway track, Yyterin speedwaystadion is approximately 16 kilometres to the north off the Mäntyluodontie, the track has held the final of the Finnish Individual Speedway Championship six times from 1983 to 2019.[65] Yyteri Golf is also located in this region.[66] The other golf course, Pori Golf Club, is on the outskirts of the city.[67]

The city-owned indoor swimming pool was opened in September 2011. It is a modern facility with seven pools of variable depth and size, three saunas and a gym.[68]

Notable sportspeople

[edit]Olympic gold medal winners from Pori include Greco-Roman wrestler Kelpo Gröndahl (1952) and weightlifter Kaarlo Kangasniemi (1968). Leo-Pekka Tähti, five-time Paralympic gold medalist in category T54 sprint events (100m: 2004, 2008, 2012, 2016; 200m: 2004), is also from Pori. Other Olympic medalists from Pori are swimmer Arvo Aaltonen (1920), weightlifter Jouni Grönman (1984), boxers Joni Nyman (1984) and Jyri Kjäll (1992), pole vaulter Eeles Landström (1960), archer Kyösti Laasonen (1972) and ice hockey players Sakari Salminen (2014) and Sari Marjamäki (née Fisk, 1998). The best known, currently active athletes from Pori are swimmer Matti Mattsson, hurdler Nooralotta Neziri, NHL ice hockey goaltender Joonas Korpisalo and players Jesperi Kotkaniemi, Joel Armia and Erik Haula, and Paralympic gold medalist Leo-Pekka Tähti. Mikko Salo won the 2009 CrossFit Games in Aromas, California and was declared the "World's Fittest Man."[69]

Media

[edit]The most widely read daily newspaper of Pori area is the independent Satakunnan Kansa.[70] Other local media were the politically-affiliated papers Uusi Aika, which was aligned with the Social Democrats,[71][72] and Satakunnan Työ, which was aligned with the Left Alliance.[73][74]

Radio Pori is a radio station established in 1985 as one of the first commercial stations in Finland.[75] Eazy 101 was during 2012–2015 a local radio station mainly for younger people under 30.[76][77] Public service radio in Pori area is Yle Satakunta, a regional station of Yle Radio Suomi.[78] Yle TV2 screens daily local news from the Pori region and Satakunta province on its national channel.

Points of interest

[edit]

Yyteri Beach is located 17 kilometres out of the city center. The six-kilometre-long beach is one of the largest in Baltic Sea.[25] Tourist facilities in Yyteri include a hotel/spa, camping/caravan park and a golf course. It is also very popular among windsurfers.[79] Island of Reposaari is located some 10 kilometres further of Yyteri. It is connected with the mainland by highway. Reposaari is a unique village with a townscape of mostly wooden buildings and a population of 1,000 people. The island has a church, marina, hostel, camping site, several restaurants and a fishing port.[80]

Juselius Mausoleum at the Käppärä Cemetery was built in 1901 for the 11-year-old daughter of businessman Fritz Arthur Jusélius. It is the only mausoleum in Finland. The building is decorated with frescoes by Akseli Gallen-Kallela who is one of Finland's most prominent painters. Kirjurinluoto is an island and park at the delta of river Kokemäenjoki by the city center. On the south side of the river stand the Empire style buildings of the "old town", raised after the 1852 city fire. 1841 built Old Town Hall is one of the few buildings saved from the fire. Central Pori Church and the Greek Orthodox Church of Pori dedicated to John the Theologian are the most notable churches.[79] 10 kilometres outside the city at the municipality of Ulvila are the Medieval St. Olaf's Church and the 18th century ironworks of Leineperi.

Villa Mairea is a design of Finland's most famous architect Alvar Aalto. It is considered one of his most significant works. The villa is widely known all over the world among the ones interested in modern architecture.[81] Villa Mairea is located in Noormarkku, a municipality annexed with Pori in 2010.

The northernmost district of Pori, Ahlainen, is a natural seaside village consisting of wooden houses. The Ahlainen's wooden church, built in 1796, is located in the district and is the oldest surviving church building in Pori.[25] Eteläranta ("South Shore"), located along the Kokemäki River, is a value area of Pori, as the stone house blocks of the riverside landscape were built mostly after the Great Fire of Pori in 1852.[25][82]

Notable people

[edit]

- Arvo Aaltonen (1892–1949), breaststroke swimmer and Olympic bronze medalist

- Lorenz Nikolai Achté (1835–1900), opera singer, composer, conductor and music teacher

- Joel Armia (born 1993), professional ice hockey player

- Nikita Bergenström (born 1965), criminal and triple murderer

- Tuure Boelius (born 2001), YouTuber, singer and actor

- Danny (born 1942), singer and guitarist

- Samuli Edelmann (born 1968), actor and singer

- Akseli Gallen-Kallela (1865–1931), painter

- Eino Grön (born 1939), singer

- Richard Hall (1860–1942), painter

- Jenni Haukio (born 1977), poet and First Lady of Finland

- Lotta Henttala (born 1989), racing cyclist

- Kari Hotakainen (born 1957), author

- Laura Huhtasaari (born 1979), politician

- Fritz Arthur Jusélius (1855–1930), industrialist and politician

- Krista Kiuru (born 1974), politician

- Timo Koivusalo (born 1963), film director, screenwriter, actor, columnist and musician

- Aleksandr Kokko (born 1987), football player

- Anna Kontula (born 1977), sociologist and politician

- Jesperi Kotkaniemi (born 2000), professional hockey player

- Olli Lindholm (1964–2019), singer and guitarist

- Kari Mäkinen (born 1955), archbishop

- Visa Mäkinen (born 1945), film director, producer, screenwriter and actor

- Nooralotta Neziri (born 1992), 100-meter hurdler

- Joonas Nordman (born 1986), actor, comedian, impersonator, director and screenwriter

- Niko Palonen (born 1989), professional ice hockey player

- Risto E. J. Penttilä (born 1959), businessman and politician

- Emil von Qvanten (1827–1903), poet, librarian, publisher and politician

- Miro Rahkola (born 1988), ice hockey player

- Marjatta Raita (1944–2007), actress

- Henry Saari (born 1964), actor, director and porn star

- Tero Saarinen (born 1964), dance artist and choreographer

- Sakari Salminen (born 1988), professional ice hockey player

- Johan Eberhard von Schantz (1802–1880), admiral, ship designer and explorer

- Kai Setälä (1913–2005), physician and professor

- Jorma Uotinen (born 1950), dancer, singer and choreographer

International relations

[edit]Twin towns – Sister cities

[edit] Bremerhaven, Germany, since 1967

Bremerhaven, Germany, since 1967 Eger, Hungary, since 1973

Eger, Hungary, since 1973 Kołobrzeg, Poland, since 1975

Kołobrzeg, Poland, since 1975 Mâcon, France, since 1990

Mâcon, France, since 1990 Porsgrunn, Norway, since 1956

Porsgrunn, Norway, since 1956 Riga, Latvia, since 1965

Riga, Latvia, since 1965 Stralsund, Germany, since 1968

Stralsund, Germany, since 1968 Sundsvall, Sweden, since 1940

Sundsvall, Sweden, since 1940 Sønderborg, Denmark, since 1952

Sønderborg, Denmark, since 1952

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Vuonokari, Pekka (June 22, 2017). "Pori – joen ja meren kaupunki". Päivämies (in Finnish). Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ^ a b c J. W. Ruuth (1958). "Kaupungin perustamiskirje". Porin kaupungin historia II (in Finnish). City of Pori. p. 269.

- ^ a b "Area of Finnish Municipalities 1.1.2018" (PDF). National Land Survey of Finland. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ^ "Population increased most in Uusimaa in January to June 2025". Population structure. Statistics Finland. 2025-07-24. ISSN 1797-5395. Retrieved 2025-07-24.

- ^ "Number of foreign-language speakers exceeded 600,000 during 2024". Population structure. Statistics Finland. 2025-04-04. ISSN 1797-5395. Retrieved 2025-04-05.

- ^ "Population according to age (1-year) and sex by area and the regional division of each statistical reference year, 2003–2020". StatFin. Statistics Finland. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ a b "Luettelo kuntien ja seurakuntien tuloveroprosenteista vuonna 2023". Tax Administration of Finland. 14 November 2022. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- ^ Mead, William Richard (1993). An Experience of Finland. Hurst. ISBN 978-1-85065-165-9.

- ^ a b "Teatteritalon historia" (in Finnish). City of Pori. Archived from the original on September 21, 2008. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ^ MTV:n grilliraportti: Näin syntyy legendaarinen porilainen – on siinä makkarasiivulla kokoa! – MTV Uutiset (in Finnish)

- ^ "Meren kaupunki Pori". YLE Elävä arkisto (in Finnish). YLE. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ^ "Porin seutu" (in Finnish). Porin seudun kehittämiskeskus Oy POSEK. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ^ Dialogiluento, Kaarina Niskala ja Markus H. Korhonen: Kylästä kaupungiksi – mikä kaupunkirakenteessa ja -kulttuurissa on pysyvää Archived 2005-09-09 at the Wayback Machine (in Finnish)

- ^ Elo Jarkko (1999). Satakunnan maakuntakirja (in Finnish). Pori: Satakuntaliitto. ISBN 952-5295-08-7.

- ^ "Hotellit – Pori". Kuumat.com (in Finnish). Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ^ "Asetus vaakunan vahvistamisesta Porin kaupungille". Valtionarkisto (in Finnish). Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ^ Peter Slotte (16 January 2007). "Paikannimet kahdella kielellä – pitkä kulttuuriperinne" (in Finnish). Kotimaisten kielten tutkimuskeskus. Archived from the original on 3 June 2009. Retrieved 6 March 2009.

- ^ Karhukaupungin Demarit

- ^ Karhukaupungin Kodinpalvelut

- ^ Karhu vieraili Porin kansallisessa kaupunkipuistossa Archived 2007-07-13 at the Wayback Machine: "Karhukaupunki Porin nimikkoeläin oli lehtitietojen (Satakunnan Kansa) mukaan näyttäytynyt Ilmailuopiston tiellä noin klo kaksi koiraansa ulkoiluttaneelle lenkkeilijälle."

- ^ J.W., Ruuth (1958). "Kaupungin perustamiskirje". Porin kaupungin historia II (in Finnish). Porin kaupunki. p. 269. Archived from the original on 8 December 2008. Retrieved 7 March 2009.

- ^ Pori-tieto – Isoviha Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine (in Finnish). Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- ^ Pori-tieto – Krimin sota ja Pori Archived 2016-08-09 at the Wayback Machine (in Finnish). Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- ^ Eero Auvinen: Krimin sota, Venäjä ja suomalaiset. University of Turku, 2015. (in Finnish)

- ^ a b c d Zitting, Marianne (July 10, 2017). "Ei vain asuntomessut - 10 mainiota perustetta pistäytyä Porissa". Iltalehti (in Finnish). Retrieved September 14, 2021.

- ^ Vesa Paavilainen: "Liekit muuttivat Porin tulipätsiksi toukokuussa 150 vuotta sitten", p. 10. Satakunnan Kansa, May 1, 2002. (in Finnish)

- ^ Porin kaupunki – 1939–1945 Sota ja teollisuus Archived 2012-03-06 at the Wayback Machine (in Finnish). Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- ^ Lexikon der Wehrmacht (in German). Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- ^ Väisänen, Teemu. "Feldluftpark Pori: Luftwaffen huoltokenttää tutkimassa". Skas 1/2020 (in Finnish). Suomen keskiajan arkeologian seura: 64–68.

- ^ Finnish-Russian Association of Pori (in Finnish). Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- ^ Tilastoja Suomen ilmastosta 1981 - 2010. Ilmatieteen laitos. 14 August 2012. ISBN 9789516977655.

- ^ "Porin kaupungin tilastollinen vuosikirja 2018" (PDF) (in Finnish). Porin kaupunki. November 2018. p. 18. Retrieved 23 September 2023.

- ^ Petri S. Juuti (January 2010). Pori, kaupunki joen varrella (in Finnish). Tampere University. p. 13. ISBN 978-951-44-8215-1. Retrieved 23 September 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f "Number of foreign-language speakers exceeded 600,000 during 2024". Population structure. Statistics Finland. 2025-04-04. ISSN 1797-5395. Retrieved 2025-04-10.

- ^ "Suomen kuntien väkilukutiedot 1.1.1952" Mitä missä milloin Yearbook 1954.

- ^ "Number of foreign-language speakers grew by nearly 38,000 persons". Statistics Finland. 31 May 2023. Retrieved 12 September 2023.

- ^ "Persons with foreign background". Statistics Finland. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ^ Key figures on population by region, 1990-2023 Statistics Finland

- ^ "Pori: Tulos puolueittain ja yhteislistoittain". Ministry of Justice. 22 June 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ "Lauri Inna on Porin uusi kaupunginjohtaja". Satakunnan Kansa. 14 November 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- ^ "Suomen sisäisen lentoliikenteen suurin kasvu alkuvuonna Porissa: "Liikematkailu on elpynyt"". Yle Uutiset (in Finnish). 2025-03-12. Retrieved 2025-12-17.

- ^ McGarrity, John; Gloystein, Henning (27 September 2013). "Big freighter traverses Northwest Passage for 1st time". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2023-06-14.

- ^ "Työllisyyskatsaus" (in Finnish). ELY-keskus. May 31, 2018. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- ^ a b Tilastollinen vuosikirja 2017 (in Finnish). Pori: City of Pori. 2017. ISBN 978-952-7020-41-8.

- ^ a b Family life Archived 2013-09-24 at the Wayback Machine City of Pori. Retrieved November 16, 2013.

- ^ Pori Lyceum Official Homepage Archived 2013-12-03 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved November 16, 2013.

- ^ Palmgren Conservatory Official Homepage (in Finnish). Retrieved November 16, 2013.

- ^ Finnish Aviation Academy Official Homepage Archived 2013-12-02 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved November 16, 2013.

- ^ Nyten esittely seuran kotisivuilla Archived 12 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Pori Jazz Festival". VisitFinland.com. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ^ "History of Pori Jazz". Pori Jazz. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ^ What is SuomiAreena? Archived 2013-12-09 at the Wayback Machine SuomiAreena Official Homepage. Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- ^ Rakastajat-teatteri Official Homepage Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- ^ Vuorela, Mervi (13 October 2024). "Pori on Suomen tärkeimpiä rock-kaupunkeja, mutta kukaan ei ole onnistunut kirjoittamaan siitä – paitsi nyt". Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). Retrieved 14 October 2024.

- ^ Lindfors, Jukka (13 November 2007). "Porirockin nousu ja tuho". Elävä arkisto (in Finnish). Yle. Retrieved 14 October 2024.

- ^ Satakunta Museum Archived 2015-04-19 at the Wayback Machine City of Pori. Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- ^ Pori Art Museum Museot.fi. Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- ^ Rosenlew Museum Archived 2013-10-19 at the Wayback Machine City of Pori. Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- ^ The Ark Nature Centre Archived 2013-05-18 at the Wayback Machine City of Pori. Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- ^ Satakunta Museum, Building Heritage House Toivo and The home of the Korsman Family Museums.fi. Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- ^ "Pori Ässät take ice hockey championship". Yle News. April 25, 2013. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- ^ "Porin kultajuhlat sujuivat rauhallisesti" (in Finnish). Yle Uutiset. April 27, 2013. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- ^ "Europa League football for Vaasa in 2014". Yle News. October 20, 2013. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- ^ History of Segelföreningen i Björneborg (in Finnish). Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- ^ "Speedway Individual Finnish Championship". Speedway Sanomat. Retrieved 13 February 2024.

- ^ Yyteri Golf Archived 2013-11-13 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- ^ Pori Golf Club – Kalafornia Golfcouse Archived 2013-11-13 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- ^ Keskustan uimahalli Archived 2013-11-13 at the Wayback Machine (in Finnish). The City of Pori. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- ^ "A Finn at the Finish". 2009 CrossFit Games. July 12, 2009. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- ^ Levikkitilasto – Media Audit Finland (in Finnish)

- ^ Uuden Ajan lakkautus varmistui – kannattamattomuus lopettaa 113-vuotiaan demarilehden – Yle (in Finnish)

- ^ Uusi Aika loppuu – lehden viimeinen numero ilmestyy tänään – Yle (in Finnish)

- ^ Satakunnan Työ siirtyy verkkoon – julkaisuoikeudet vasemmistopiirille – Yle (in Finnish)

- ^ Minne katosi Satakunnan Työ? – verkkosivut pimeinä – Yle (in Finnish)

- ^ Radiomedia.fi (in Finnish)

- ^ Radio Melodia Radio Eazyn tilalle Porissa – Mediamonitori (in Finnish)

- ^ "Radio Eazy 101 aloitti lähetykset" Eazy 101 12.1.2012 (in Finnish)

- ^ YLE/alueet (in Finnish)

- ^ a b The Sights Archived 2011-12-02 at the Wayback Machine City of Pori. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^ Reposaaren yhdyskunta Finnish National Board of Antiquities. (in Finnish). Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^ "AD Classics: Villa Mairea / Alvar Aalto". ArchDaily. October 28, 2010. Retrieved November 28, 2013.

- ^ Eteläranta, Pori – Matkailu-opas (in Finnish)

- ^ "Verkostot maailmalla" (in Finnish). City of Pori. 12 October 2017. Archived from the original on 21 April 2019. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

External links

[edit]- City of Pori – Official website

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

Name

Etymology and Historical Usage

The Swedish name Björneborg, under which the city was founded on March 8, 1558, by Duke John (Johan) of Finland, combines björn ("bear") and borg ("fortress" or "castle"), literally translating to "bear fortress" or "bear castle."[7] This nomenclature reflected the strategic establishment of a fortified settlement at the mouth of the Kokemäenjoki River, previously part of the older town of Ulvila chartered in 1365.[8] The choice of "bear" may evoke the region's wildlife or symbolic strength, though no primary contemporary records specify the rationale beyond standard Swedish toponymic conventions for new strongholds. The Finnish name Pori emerged as a phonetic adaptation of the -borg suffix, undergoing Fennicization to align with native pronunciation patterns while retaining the fortress connotation.[9] During Sweden's rule over Finland (until 1809), Björneborg was the official and exclusive designation in administrative, legal, and cartographic documents, as evidenced in 16th- and 17th-century Swedish charters and maps. A Latin calque, Arctopolis ("bear city"), appeared in occasional scholarly or ecclesiastical contexts, directly translating the Swedish elements for international correspondence.[9] Post-1809, under Russian Grand Duchy autonomy, bilingual usage increased, but Pori gained prominence in Finnish-language records by the 19th century amid rising national consciousness. Following Finland's independence in 1917, Pori became the standardized name in official state contexts, though Björneborg endures in Swedish-speaking communities, military traditions (e.g., the Björneborgarnas Marsch), and dual-language signage per Finland's bilingual policy.[9] No evidence links Pori to unrelated Finnish roots like pori ("pore"), confirming its Swedish-derived origin without pre-1558 indigenous precedents.[5]History

Founding and Early Development

Pori was established on March 8, 1558, by Duke John of Finland (Juhana Herttua), who later ascended as King John III of Sweden, at the estuary of the Kokemäki River on the Gulf of Bothnia coast.[10] [11] The founding served to supplant the upstream medieval settlement of Ulvila, chartered in 1365, whose harbor had silted and become impassable to larger vessels due to post-glacial rebound, rendering it unsuitable for maritime trade.[12] [13] Duke John ordered Ulvila's merchants and burghers to relocate southward to the new site, offering a 10-year tax exemption to incentivize the transfer and stimulate economic activity.[14] The initial population numbered approximately 300 residents, primarily migrants from Ulvila, who brought established trading networks focused on timber, tar, and other regional commodities.[15] Under Swedish administration, the settlement—known as Björneborg—developed as a fortified trading post, benefiting from its strategic position for exporting goods to Stockholm and continental Europe via the Baltic Sea routes.[9] Early infrastructure included wooden structures clustered around a central market square, with the river facilitating shipbuilding and commerce; by the late 16th century, it had emerged as a key regional hub in the Province of Satakunta.[11] Growth in the 17th century was modest but steady, supported by royal privileges that granted burghers monopolies on certain trades and exemptions from certain tolls, fostering guilds for craftsmen such as smiths and shipwrights.[9] The city's layout, planned with a grid pattern influenced by Renaissance urban ideals imported from Sweden, emphasized defensibility against coastal raids, though vulnerabilities to fire and flooding persisted due to reliance on timber construction.[13] By the early 18th century, Pori had solidified its role as a primary export point for Satakunta's agrarian and forestry products, laying foundations for later industrialization.[12]18th and 19th Century Growth

During the 18th century, under Swedish rule, Pori (known as Björneborg) developed as a regional port city in western Finland, benefiting from its location near the Gulf of Bothnia and the Kokemäki River. Trade connections with Stockholm were established early, facilitating exports of local products such as tar and timber, which were key to the Swedish-Finnish economy. By 1766, the city's population reached approximately 1,500 inhabitants, making it one of the larger urban centers in Finland at the time.[16] In the early 19th century, following Finland's incorporation into the Russian Empire as an autonomous grand duchy in 1809, Pori continued its economic expansion driven by maritime trade and forestry-related industries. The population grew from around 3,000 in 1830 to approximately 7,000 by 1860, reflecting increased commercial activity and urbanization. By the end of the 1830s, Pori had become Finland's second-largest exporter of deals (sawn pine planks), capitalizing on rising demand for timber in European markets.[17] In the 1840s, it ranked as the third-largest exporter overall in Finland, underscoring its role in the burgeoning export-oriented economy.[16]Major Disasters and Reconstructions

Pori has endured numerous catastrophic fires since its founding, resulting in extensive reconstructions that shaped its urban development. The initial destruction occurred in 1571, when the wooden structures of the early settlement were consumed by flames, necessitating a full rebuild. During the 17th century, the city suffered at least six major fires, each prompting rebuilding efforts amid the era's prevalent timber architecture and limited firefighting capabilities.[18] The most devastating event was the Great Fire of 1852, which ignited on May 22 and razed nearly the entire city within a single day. This conflagration destroyed over 200 buildings, comprising more than 75% of Pori's structures, and rendered a significant portion of the population homeless.[19][11] Only a handful of stone edifices, such as the Old Town Hall (whose clock tower was damaged but later restored), survived intact. The fire's rapid spread was exacerbated by dry conditions, strong winds, and closely packed wooden homes, highlighting the vulnerabilities of pre-industrial urban planning.[18] Reconstruction following the 1852 fire transformed Pori's layout and building codes. Authorities implemented a rigorous grid-plan redesign, emphasizing fire-resistant stone and brick construction in the central districts to mitigate future risks. This shift marked the inception of Pori's industrial era, as the rebuild incorporated modern infrastructure, including wider streets and regulated zoning, while debates arose over relocating the city to the nearby island of Reposaari (Räfsö). By the late 19th century, these measures had stabilized the urban core, preserving elements of neoclassical architecture amid the neoclassical revival.[20][21][18] No other large-scale natural disasters, such as floods or earthquakes, have dominated Pori's historical record to the extent of these fires, though the Kokemäki River has posed periodic flooding threats that informed later urban resilience planning.[22]Wars and Conflicts

During the Finnish Civil War (27 January–15 May 1918), an unofficial front line divided the country between socialist Red forces in the south and industrial areas and conservative White forces in the north and east, extending westward from Pori along the coast to Viipuri in the east; this positioning placed Pori near the contested southwestern sector where Red Guards maintained initial control amid revolutionary unrest, including jailbreaks by local troops in late 1917.[23] [24] White advances eventually secured the region, contributing to the overall White victory by mid-May 1918.[25] In the Winter War (1939–1940), Soviet air forces conducted raids extending to Pori on the Gulf of Bothnia coast, including mass attacks on 3 February 1940 targeting coastal and inland sites as part of broader efforts to weaken Finnish defenses and infrastructure.[26] These bombings focused primarily on the harbor area, with four documented strikes between 1939 and 1940 causing limited damage but highlighting Pori's strategic vulnerability due to its port and proximity to potential invasion routes. During the Continuation War (1941–1944), the Pori airfield hosted German Luftwaffe operations, serving as the base for Feldluftpark 3/XI, an aviation equipment depot that supported maintenance and logistics for Axis aircraft in northern theaters; this collaboration stemmed from Finland's co-belligerent status against the Soviet Union, with German personnel constructing barracks, hangars, and support facilities.[27] [28] Soviet bombing campaigns persisted sporadically, though ground fighting bypassed Pori directly. In the Lapland War (1944–1945), as Finnish forces compelled German withdrawal per armistice terms with the Allies, retreating Luftwaffe units demolished the Pori airfield on 18 September 1944, destroying runways and infrastructure to deny assets to advancing troops; this scorched-earth tactic inflicted significant local damage but marked the end of Axis presence in the region without major prolonged engagements in Pori itself.[29]Post-War Modernization and Recent Developments

Following World War II, Pori contributed to Finland's industrialization drive, spurred by war reparations and economic reconstruction, with the Rosenlew company expanding its multidisciplinary operations in machinery, engines, and consumer goods, serving as a major employer in the region.[30] The city emerged as a hub for heavy industry and port activities, supporting national export-led growth through the 1950s and 1960s.[31] Population expansion accompanied this, fueled by rural-urban migration and municipal annexations, peaking above 80,000 residents by the mid-1970s.[32] Urban modernization in the 1970s included the development of the Promenadi-Pori pedestrian zone, established in 1977 to revitalize the city center and accommodate growing vehicular and foot traffic.[33] Culturally, the Pori Jazz Festival, founded in 1966 by local enthusiasts, evolved into one of Europe's premier jazz events, drawing international performers and boosting the city's profile annually in July.[34] The 1980s brought industrial challenges, exemplified by Rosenlew's closure in 1987 amid broader sectoral shifts, prompting diversification into services, education, and tourism.[30] The University Consortium of Pori (UCPori), established in 2004 as a collaboration among Finnish universities, has since fostered multidisciplinary higher education and research, hosting over 1,200 students and supporting regional innovation in a repurposed textile mill campus.[35] Recent initiatives emphasize cultural and economic renewal, including plans for a cultural quarter funded by private foundations linked to historic families like Rosenlew, alongside tourism growth yielding €103 million in direct revenue in 2024 despite national downturns.[16][36] The launch of International House Pori in 2024 further aids integration and business development, reflecting Pori's adaptation to post-industrial realities through livable urban enhancements and entrepreneurial promotion.[37]Geography

Location and Topography

Pori lies in the Satakunta region of southwestern Finland, positioned on the western coast along the estuary of the Kokemäki River, approximately 10 kilometers inland from the Gulf of Bothnia.[38] The city's central coordinates are 61°29′N 21°48′E, placing it about 110 kilometers west of Tampere and 140 kilometers northwest of Helsinki.[39] The topography of the Pori municipality consists primarily of flat coastal plains and low-lying terrain typical of Finland's Archipelago Sea and Bothnian Sea borderlands, with gradual rises toward inland areas.[38] Elevations range from a minimum of -3 meters, reflecting reclaimed or subsident coastal zones, to a maximum of 162 meters in peripheral hills, with an average elevation of 36 meters above sea level across the sub-region.[38] This landscape supports a mix of riverine deltas, sandy shores, and forested plateaus, shaped by glacial deposits and post-glacial isostatic rebound.[38]Kokemäki River System

The Kokemäenjoki River forms the core of the Kokemäki River System, draining a basin of approximately 27,000 km² across southwestern Finland, ranking as the country's fourth-largest river basin.[40] This basin encompasses parts of Satakunta, Pirkanmaa, and Tavastia Proper regions, with a high proportion of lakes that moderate hydrological variability through storage and release of water.[41] The system's extensive lake coverage contributes to regulated flows, influenced by upstream reservoirs and hydropower operations, such as the Harjavalta plant, which affect downstream discharge patterns reaching Pori.[42] Spanning 121 km, the Kokemäenjoki originates near Lake Liekovesi in Pirkanmaa and flows westward, entering Satakunta before reaching Pori, where it discharges into the Gulf of Bothnia.[43] In the lower reaches through Pori, the river channel deepens in sandy valleys before branching into multiple distributaries, eroding banks upstream of the city center while depositing sediments in urban areas, shaping local topography.[44] The resulting delta at Pori's coast represents Scandinavia's largest, formed post-glacially amid ongoing isostatic rebound of about 0.7 cm annually, which continues to expand coastal landforms.[45][46] Hydrologically, the system experiences average discharges supporting Pori's water management, but winter ice jams and spring snowmelt floods pose recurrent risks, particularly at the delta where Pori concentrates urban and industrial activity.[47] Monitoring and forecasting of water levels occur nationally due to these vulnerabilities, with flow regulation mitigating but not eliminating peak events in the 12 km tidal-influenced lower reach.[48] The basin's nutrient and sediment loads, derived from agricultural and forested uplands, influence estuarine ecology near Pori, historically sustaining fisheries like salmon while requiring ongoing environmental controls.[43]Climate and Environmental Conditions

Pori features a warm-summer humid continental climate classified as Köppen Dfb, with cold, snowy winters lasting from late November to mid-March and a brief warm season from early June to early September.[49] The city's coastal position on the Gulf of Bothnia moderates extremes, preventing the severe inland cold typical of much of Finland, though temperatures still drop below freezing for extended periods. Average annual temperatures hover around 5–6°C, with February recording the lowest averages at highs of -2°C and lows of -8°C, while July peaks with highs of 21°C and lows of 12°C.[50] Precipitation totals approximately 700 mm annually, distributed year-round but peaking in August at about 58 mm of rain, with February the driest at 13 mm; snowfall is heaviest in January, averaging 15 cm.[50] [51] Wind speeds average 6–9 mph, strongest in winter, and cloud cover is highest in January at 72% overcast, contributing to short daylight hours in winter (around 6 hours) versus up to 19 hours in summer.[50] The Kokemäki River and proximity to the Baltic Sea influence local microclimates, fostering higher humidity (often 80–90% in winter) and occasional fog, while sea surface temperatures range from 1°C in March to 16°C in August.[50] [49] Environmental conditions remain favorable for a mid-sized industrial city, with air quality consistently rated good; PM2.5 levels typically stay below 10 µg/m³, supported by low urban density and prevailing westerly winds dispersing pollutants.[52] The surrounding landscape includes coastal dunes, boreal forests, and wetlands, which sustain diverse flora and fauna, including migratory birds and typical Nordic species, though regional biodiversity faces pressures from forestry and climate shifts, as acknowledged in local commitments to restoration efforts.[53] [54] Water quality in the river and gulf is monitored, with occasional nutrient runoff from agriculture noted but generally compliant with EU standards.[55]Demographics

Population Dynamics

As of 2024, Pori's municipal population stands at 83,305 residents, reflecting a density of approximately 72 inhabitants per square kilometer across its 1,156 km² area.[56] [57] This figure incorporates expansions from municipal mergers, including Noormarkku in 2010 and Lavia in 2015, which added territory and residents to the core urban area.[58] Prior to these consolidations, the population hovered around 75,000–80,000 in the late 20th century, following a post-World War II expansion driven by industrial development and annexations of adjacent rural districts in 1950.[59] Population growth peaked in the mid-1970s, surpassing 80,000, amid broader Finnish urbanization trends that drew labor to coastal manufacturing hubs like Pori's textile and metal industries. Subsequent decades saw stabilization, with the population reaching 84,587 by 2017 before entering a phase of gradual decline. Between 2014 and 2017, the average annual variation was -0.33%, influenced by a negative natural balance (fewer births than deaths) and net domestic out-migration to larger centers like Tampere or Helsinki. Recent estimates indicate an annual change of -0.11% from 2021 to 2023, consistent with Finland's national fertility rate of 1.3 children per woman and aging demographics, where over 20% of residents exceed age 65.[59] [57] [60] These dynamics underscore Pori's transition from growth-oriented industrialization to challenges of demographic stagnation, with limited offsetting immigration (foreign-born residents at 5.2% in 2023, primarily from former Soviet states). Without sustained inward migration or policy interventions to boost local retention, projections align with Finland's broader trajectory of subdued growth or contraction in regional cities.[32] [60]Linguistic Composition

Pori is classified as a monolingual Finnish-speaking municipality under Finnish law, with Finnish serving as the sole official language. As of 2024, approximately 95% of the city's residents report Finnish as their mother tongue, reflecting the region's historical and cultural dominance of the language in Satakunta province.[61] This figure aligns with Statistics Finland's municipal-level data on primary languages, where Finnish constitutes the overwhelming majority in non-coastal, inland areas like Pori.[62] Swedish, Finland's other national language, is spoken as a first language by a small minority of about 500 residents, equating to roughly 0.6% of the population based on 2022 estimates from official records.[63] This low proportion underscores Pori's lack of bilingual status, as the threshold for mandatory Swedish-language services requires at least 8% or 3,000 speakers of the minority language.[64] Sámi languages have negligible presence, with fewer than a handful of speakers if any. Speakers of foreign languages as a mother tongue comprise the remaining share, estimated at around 4-5% in 2024, up from 3.4% in 2019 due to immigration trends.[65] Common non-national languages include Russian (approximately 0.9%), Arabic (0.4%), and English (0.3%), though exact distributions vary annually per Statistics Finland tabulations; these groups are concentrated in urban employment hubs but do not alter the Finnish linguistic hegemony.[62] Local dialects of Finnish, known as Pohjanmaa or Satakunta variants, feature phonetic traits like softened consonants and vowel shifts, but standardized Finnish prevails in education, media, and administration.Immigration Trends and Societal Impacts

In recent years, Pori has experienced a notable increase in immigration, contributing significantly to its population stability amid domestic outflows. Net immigration from abroad reached a record 796 persons between 2020 and 2023, surpassing previous highs and helping offset internal migration losses.[66] By 2023, foreign citizens comprised approximately 4% of Pori's population, aligning with regional trends in Satakunta where the figure stood at 9,126 individuals or 4% overall.[67] This growth, concentrated in Pori as the regional hub, has been driven by family reunification, work, studies, and humanitarian reasons, with Pori accounting for a substantial share of Satakunta's inflows alongside Rauma.[68] Demographically, immigration has mitigated Pori's population decline risks, with foreign arrivals providing a net positive amid aging native cohorts and low birth rates. Projections indicate that without sustained immigration, Satakunta's population could drop by up to 18% by 2050, but recent trends suggest doubling inflows could stabilize or balance this in urban centers like Pori.[69] Economically, immigrants bolster the local labor market, particularly in sectors requiring international skills, supported by targeted integration programs emphasizing employment and language training. The city's International House Pori and municipal help-desk (MAINE) assist with residence permits, job placement, and vocational guidance, while the Satakunta Multicultural Association offers work-life orientation courses in simplified Finnish to facilitate entry into regional industries.[70][71] Socially, immigration has prompted expanded integration services, including cultural exchange events and volunteer opportunities through organizations like the Red Cross and Pentecostal congregations, which have historically supported asylum seekers in the region.[72] These efforts aim to foster two-way adaptation, though national data highlight persistent challenges such as lower employment rates among immigrant women (around 56% versus 74% for Finnish men) and the need for enhanced language proficiency for full societal participation.[73] In Pori, multicultural initiatives promote cohesion, but the modest scale of inflows—relative to larger Finnish cities—has limited widespread societal strains, with immigration viewed locally as a counter to regional depopulation rather than a dominant policy issue.[74]Religious Affiliations

The predominant religious affiliation among residents of Pori is membership in the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland, which operates five parishes within the city: Keski-Pori, Länsi-Pori, Meri-Pori, Noormarkku, and Porin Teljä. As of the end of 2021, these parishes collectively reported 60,602 members.[75] Individual parish figures from 2022 include 18,247 members in Keski-Pori and 11,421 in Länsi-Pori. Given Pori's population of 83,205 as of 2023, Lutheran membership constituted approximately 73% at that time, exceeding the national average of 64% reported for December 2023.[76][77] Membership in the Evangelical Lutheran Church has followed national patterns of gradual decline, driven by annual disaffiliations outpacing new joins; between 2019 and 2023, Finland-wide net losses exceeded 100,000 members annually in some years.[77] Active participation remains low, with church attendance typically under 2% of members weekly, reflecting broader secularization in Finnish society where nominal affiliation persists but personal religiosity is minimal.[78] Minority religious communities in Pori include the Finnish Orthodox Church, which maintains a congregation in the city, alongside smaller groups such as Pentecostals, Adventists, and Jehovah's Witnesses.[79] Adherents to these faiths, as well as Catholicism and Islam—primarily linked to immigrant populations from regions like the Middle East and South Asia—account for less than 2% of residents combined, consistent with national figures where non-Lutheran Christians and other faiths total under 3%.[80] Approximately 25-30% of Pori's population reports no religious affiliation, mirroring Finland's rising unaffiliated rate of over 30% nationally.[56]Government and Politics

Administrative Framework

Pori operates as an independent municipality with city status under Finland's Local Government Act, serving as the administrative center of the Satakunta region while retaining autonomous local governance. The City Council, consisting of 59 members elected through municipal elections every four years, functions as the highest decision-making body, approving the annual budget, strategic plans, and key policies while overseeing overall city operations and finances. Council meetings occur monthly and are open to the public, ensuring transparency in deliberations.[81] The City Board, elected by the City Council from its members for a four-year term, acts as the primary executive organ, responsible for preparing agenda items for council approval, supervising administrative divisions, managing fiscal implementation, and representing the municipality in external legal and contractual matters. It meets weekly to address operational efficiency and compliance.[82] The mayor, serving as the chief executive officer, leads day-to-day administration, coordinates between the board and municipal departments, and implements council directives; Lauri Inna has held this position since March 2023. Specialized committees and boards, appointed by the council, handle sector-specific oversight, including education, health services, and land-use planning, with protocols published in accordance with statutory requirements. Pori lacks formal sub-municipal administrative units, maintaining a centralized structure typical of smaller Finnish cities.[83][84][85]Electoral Outcomes and Party Influence

The Social Democratic Party (SDP) emerged as the leading party in Pori's municipal elections on April 13, 2025, capturing 31.5% of the votes—a gain of 10 percentage points and approximately six additional seats compared to 2021—amid a national leftward shift in local voting patterns.[86] [87] This result reflected Pori's industrial and working-class base, where SDP has historically drawn strong support, though turnout remained low at around 54%.[87] The 59-member city council, Pori's highest decision-making body, saw seats distributed proportionally under Finland's d'Hondt method, with SDP's surge positioning it as the largest faction.[81] Despite SDP's electoral success, influence over executive functions shifted through post-election arrangements. A technical electoral alliance comprising the National Coalition Party (NCP), Centre Party, Green League, and Finns Party secured a collective majority of seats, enabling them to sideline SDP in key positions.[88] The city executive board (kaupunginhallitus), which prepares council matters and oversees administration, was chaired by NCP's Mikael Ropo, with SDP's Jarno Joensuu as first deputy and Green League's Laura Pullinen as second deputy for 2025–2027, indicating a cross-ideological coalition to balance urban development, welfare services, and fiscal restraint.[89] The council chair, Krista Kiuru (SDP), holds ceremonial influence but limited executive power.[89] Pori's mayor, Lauri Inna, appointed in 2022 and serving through 2025, operates as a non-partisan professional administrator, selected by the council with broad cross-party support rather than direct partisan affiliation, focusing on implementation over policy initiation.[90] [91] In prior elections, such as 2021, SDP polled 21.5% amid lower turnout, underscoring the party's consistent dominance alongside NCP as Pori's core political forces, though populist and center-right parties have gained sporadically on immigration and economic issues.[92] Party influence manifests primarily through board majorities shaping budgets for infrastructure, education, and social services, with SDP advocating welfare expansion and NCP emphasizing market-oriented reforms.[88]Policy Debates and Local Governance Issues

In recent municipal elections held in April 2025, the Social Democratic Party (SDP) secured over 30% of votes, emerging as the largest group in Pori's city council, yet the National Coalition Party (Kokoomus) formed a technical coalition with the Centre Party, Greens, and Finns Party to claim the council chairmanship, breaking traditional SDP-Kokoomus cooperation known as the "aseveliakseli."[93] This shift has fostered mutual distrust among major groups, complicating the formation of a cross-party agreement essential for stable decision-making, with analysts predicting a more quarrelsome term than the previous one due to ideological clashes over fiscal austerity and personal animosities.[93] Internal divisions within Kokoomus have intensified governance challenges, including disputes over position allocations in regional bodies and budget discipline, culminating in a 2022 trust vote against party leadership at a general meeting, where critics targeted council chair Mari Kaunistola for pursuing prominent roles and deviating from agreed cooperation with SDP.[94] Similar tensions persisted into 2024, with conflicts over councilor Sampsa Kataja's dual roles as a city councilor and deputy chair of the city board prompting the council to establish a temporary committee in late April to evaluate removing the chairmanship amid allegations of procedural irregularities.[95] Within SDP, the proposed sale of Pori Energia utility has exposed rifts, with factions aligned to former minister Krista Kiuru opposing the deal, potentially leading to disciplinary actions against supporters and further eroding group cohesion.[93] Financial sustainability remains a core policy debate, exacerbated by urban shrinkage and persistent budget deficits, prompting discussions on asset divestitures like Pori Energia to balance accounts, though such measures risk deepening partisan divides over service cuts and long-term viability.[93] Concerns over forced municipal mergers have resurfaced, as in 2020 proposals linking Pori with Eurajoki to address fiscal shortfalls, echoing earlier resistance to a 2014 government-mandated merger with Lavia, which Pori opposed citing loss of local autonomy.[96][97] Local policymakers have shown limited recognition of residential segregation as a pressing issue, prioritizing economic pressures over targeted integration policies in a welfare state context where such concerns are downplayed in smaller cities like Pori.[98]Transportation

Road and Highway Infrastructure

Pori's road infrastructure encompasses state-maintained national highways and municipal streets, facilitating connectivity within the Satakunta region and to major Finnish cities. The Finnish Transport Infrastructure Agency oversees the primary highways, including Valtatie 2 (Highway 2), which spans 227 kilometers from Mäntyluoto in Pori to Palojärvi in Vihti, serving as the principal link to the Helsinki capital region and Forssa sub-region.[99] This route handles significant freight and passenger traffic as part of the EU TEN-T network, with sections featuring short four-lane segments but predominantly two-lane configuration typical of Finnish rural highways.[99] Complementing this, Valtatie 8 (Highway 8), a 626-kilometer coastal artery, traverses Pori en route from Turku northward through Rauma and Vaasa toward Oulu, supporting regional logistics for ports and industries in the Turku-Pori corridor over its 135-kilometer Turku-to-Pori segment.[100] Valtatie 11 (Highway 11), extending 101 kilometers eastward from Pori to Nokia near Tampere, provides access to inland routes. Municipal responsibility falls to the City of Pori for local streets and roads, governed by the city's Road and Street Network Plan to 2040, which emphasizes speed limits of 40 km/h in residential and central areas (with 30 km/h in core pedestrian zones) to enhance safety amid urban expansion.[101] These local networks integrate with state highways at key interchanges, such as those facilitating Highway 8's junction arrangements. Maintenance prioritizes pavement condition, drainage, and winter operations, aligned with national standards for public roads totaling over 78,000 kilometers nationwide. Ongoing enhancements address capacity and safety. A road plan for Highway 2 through Pori's center, approved with an environmental impact assessment in 2024, aims to reconcile growing volumes from Highways 2 and 8 with expanded urban land use, including potential junction upgrades between Friitala and Korpi interchanges spanning Pori and Ulvila.[102] On Highway 11, replacement of the Koivisto and Pikkuhaara bridges over the Kokemäenjoki river commenced in November 2024 at a budgeted cost of 16 million euros, with works anticipated to complete ahead of schedule and under budget by late 2025.[103][104] Further, junction improvements at Hyvelä on Highway 8 target better access via Vaasantie and Lyttyläntie roads to reduce congestion.[105] These initiatives reflect broader efforts to mitigate repair backlogs while prioritizing heavy goods traffic vital to Pori's industrial base.[106]Public Transit Systems

Public transit in Pori is primarily provided by bus services operated by Porin Linjat Oy, a company fully owned by the City of Pori.[107] The system serves the city center, suburbs, and adjacent areas, facilitating daily commuting and access to key locations such as residential districts, schools, and commercial hubs.[108] Routes are planned to connect major points including the central market square (Kauppatori) and outlying neighborhoods, with schedules varying between weekdays (Monday to Friday) and weekends (Saturday to Sunday).[109] Ticketing for the network integrates the Waltti system, which divides Pori into two zones: a limited City zone covering only line 1 between Puuvilla and the Isomäki intersection, and the broader A zone encompassing the rest of the city.[110] Single tickets, day passes, and period tickets can be purchased via the Waltti mobile app, onboard validators, or sales points, with fares structured by zone and travel duration; for instance, a single A-zone ticket valid for 75 minutes costs approximately €3.00 as of 2023.[110] Real-time route planning, schedules, and vehicle tracking are accessible through the Digitransit service at pori.digitransit.fi, supporting multimodal journeys including connections to regional buses and trains.[111] The operator maintains around 30-40 active bus lines depending on the season, with services running from early morning until evening hours, typically starting around 5:00 AM and ending by 11:00 PM on weekdays.[109] Porin Linjat reports transporting over 2.6 million passengers annually, underscoring the system's role in local mobility despite the prevalence of personal vehicles in the region.[112] Integration with national rail services occurs at Pori railway station, where local buses provide feeder connections, though the core public transit remains bus-centric without rail or tram options within the city.[113]Maritime and Air Connectivity

The Port of Pori operates as a key freight terminal on Finland's west coast along the Gulf of Bothnia, emphasizing industrial cargo handling over passenger services. It includes three primary facilities: Mäntyluoto for general cargo, Tahkoluoto for oil and chemical tankers, and the central city harbor for smaller operations. The port supports diverse logistics, including crane services up to 200 tonnes capacity, conveyor systems, and land rental for storage and operations. Cargo throughput reached 4.83 million tonnes in 2022, with total traffic at 3.6 million tonnes in 2021, reflecting a 14.94% year-over-year increase driven by export volumes.[114][115] Primary commodities include paper products, for which Pori ranks as Finland's leading export port with annual shipments exceeding 3 million tonnes, alongside bulk goods like forest industry materials and emerging offshore wind components.[116] Maritime connectivity links to major Baltic routes, with direct access channels from international shipping lanes facilitating trade to ports in Sweden, Germany, and beyond, though vessel calls average low volumes indicative of specialized rather than high-frequency traffic. Passenger ferries or cruise operations remain absent, underscoring the port's cargo-centric role.[117] Pori Airport (EFPO), located 2.6 km south of the city center, functions mainly as a regional hub with restricted commercial aviation. Scheduled passenger services consist solely of domestic nonstop flights to Helsinki-Vantaa (HEL), covering 212 km in approximately 45 minutes, with about 21 weekly departures and an average of 2 flights per day.[118] These operations, typically handled by regional carriers under Finnair codeshares, serve business and leisure travelers but exhibit low utilization, with monthly passenger counts recently around 1,300 as of mid-2025.[119] Annual traffic peaked above 54,000 passengers in 2011 but has since contracted amid competition from road and rail to larger airports, prompting a shift toward general aviation uses like flight training, parachuting, and occasional military activities. No international routes operate directly, requiring connections via Helsinki for global access, which limits Pori's role in broader air networks.[120] The facility features a single main runway (12/30) and basic amenities including two check-in counters and a cafeteria, supporting its modest scale.[121]Economy

Primary Industries and Employment

The primary sector in Pori, comprising agriculture, forestry, fishing, and related extractive activities, accounts for approximately 1% of total employment.[31] This marginal share underscores the city's economic orientation toward manufacturing, energy production, and services, with primary activities largely confined to peripheral rural areas in the Satakunta region. Urban expansion and industrialization have diminished the scale of local farming and resource extraction since the mid-20th century, limiting opportunities in these fields to small-scale operations. Forestry leverages the surrounding boreal woodlands for timber harvesting, but employment remains low due to mechanization and downstream processing dominance in facilities like sawmills and pulp operations.[122] Agriculture focuses on field crops, dairy, and horticulture in Satakunta's arable lands, contributing modestly to regional output but facing challenges from soil quality and climate. Fishing in the Gulf of Bothnia sustains artisanal fleets targeting herring, sprat, and whitefish, though catches have declined amid environmental pressures and competition from aquaculture elsewhere in Finland. Mining extraction is absent within Pori municipality, with the sector's local footprint limited to logistics via the Port of Pori, which handles ore and concentrate exports from inland sites.[123] Overall, primary sector jobs in Pori totaled fewer than 500 in recent estimates, reflecting national trends where such employment fell to under 4% nationwide by 2023.[124]Labor Market Statistics