Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Synapse

View on Wikipedia

In the nervous system, a synapse[1] is a structure that allows a neuron (or nerve cell) to pass an electrical or chemical signal to another neuron or a target effector cell. Synapses can be classified as either chemical or electrical, depending on the mechanism of signal transmission between neurons. In the case of electrical synapses, neurons are coupled bidirectionally with each other through gap junctions and have a connected cytoplasmic milieu.[2][3][4] These types of synapses are known to produce synchronous network activity in the brain,[5] but can also result in complicated, chaotic network level dynamics.[6][7] Therefore, signal directionality cannot always be defined across electrical synapses.[8]

Chemical synapses, on the other hand, communicate through neurotransmitters released from the presynaptic neuron into the synaptic cleft. Upon release, these neurotransmitters bind to specific receptors on the postsynaptic membrane, inducing an electrical or chemical response in the target neuron. This mechanism allows for more complex modulation of neuronal activity compared to electrical synapses, contributing significantly to the plasticity and adaptable nature of neural circuits.[9]

Synapses are essential for the transmission of neuronal impulses from one neuron to the next,[10] playing a key role in enabling rapid and direct communication by creating circuits. In addition, a synapse serves as a junction where both the transmission and processing of information occur, making it a vital means of communication between neurons.[11] In the human brain, most synapses are found in the grey matter of the cerebral and cerebellar cortices, as well as in the basal ganglia [12]

At the synapse, the plasma membrane of the signal-passing neuron (the presynaptic neuron) comes into close apposition with the membrane of the target (postsynaptic) cell. Both the presynaptic and postsynaptic sites contain extensive arrays of molecular machinery that link the two membranes together and carry out the signaling process. In many synapses, the presynaptic part is located on the terminals of axons and the postsynaptic part is located on a dendrite or soma. Astrocytes also exchange information with the synaptic neurons, responding to synaptic activity and, in turn, regulating neurotransmission.[10] Synapses (at least chemical synapses) are stabilized in position by synaptic adhesion molecules (SAMs)[1] projecting from both the pre- and post-synaptic neuron and sticking together where they overlap; SAMs may also assist in the generation and functioning of synapses.[13] Moreover, SAMs coordinate the formation of synapses, with various types working together to achieve the remarkable specificity of synapses.[11][14] In essence, SAMs function in both excitatory and inhibitory synapses, likely serving as the mediator for signal transmission.[11]

Many mental illnesses are thought to be caused by synaptopathy.

History

[edit]Santiago Ramón y Cajal proposed that neurons are not continuous throughout the body, yet still communicate with each other, an idea known as the neuron doctrine.[15] The word "synapse" was introduced in 1897 by the English neurophysiologist Charles Sherrington in Michael Foster's Textbook of Physiology.[1] Sherrington struggled to find a good term that emphasized a union between two separate elements, and the actual term "synapse" was suggested by the English classical scholar Arthur Woollgar Verrall, a friend of Foster.[16][17] The word was derived from the Greek synapsis (σύναψις), meaning "conjunction", which in turn derives from synaptein (συνάπτειν), from syn (σύν) "together" and haptein (ἅπτειν) "to fasten".[16][18]

However, while the synaptic gap remained a theoretical construct, and was sometimes reported as a discontinuity between contiguous axonal terminations and dendrites or cell bodies, histological methods using the best light microscopes of the day could not visually resolve their separation which is now known to be about 20 nm. It needed the electron microscope in the 1950s to show the finer structure of the synapse with its separate, parallel pre- and postsynaptic membranes and processes, and the cleft between the two.[19][20][21]

Types

[edit]

Chemical and electrical synapses are two ways of synaptic transmission.

- In a chemical synapse, electrical activity in the presynaptic neuron is converted (via the activation of voltage-gated calcium channels) into the release of a chemical called a neurotransmitter that binds to receptors located in the plasma membrane of the postsynaptic cell. The neurotransmitter may initiate an electrical response or a secondary messenger pathway that may either excite or inhibit the postsynaptic neuron. Chemical synapses can be classified according to the neurotransmitter released: glutamatergic (often excitatory), GABAergic (often inhibitory), cholinergic (e.g. vertebrate neuromuscular junction), and adrenergic (releasing norepinephrine). Because of the complexity of receptor signal transduction, chemical synapses can have complex effects on the postsynaptic cell.

- In an electrical synapse, the presynaptic and postsynaptic cell membranes are connected by special channels called gap junctions that are capable of passing an electric current, causing voltage changes in the presynaptic cell to induce voltage changes in the postsynaptic cell.[22][23] In fact, gap junctions facilitate the direct flow of electrical current without the need for neurotransmitters, as well as small molecules like calcium.[24] Thus, the main advantage of an electrical synapse is the rapid transfer of signals from one cell to the next.[22]

- Mixed chemical electrical synapses are synaptic sites that feature both a gap junction and neurotransmitter release.[25][26] This combination allows a signal to have both a fast component (electrical) and a slow component (chemical).

The formation of neural circuits in nervous systems appears to heavily depend on the crucial interactions between chemical and electrical synapses. Thus these interactions govern the generation of synaptic transmission.[23] Synaptic communication is distinct from an ephaptic coupling, in which communication between neurons occurs via indirect electric fields. An autapse is a chemical or electrical synapse that forms when the axon of one neuron synapses onto dendrites of the same neuron.

Excitatory and inhibitory

[edit]- Excitatory synapse: Enhances the probability of depolarization in postsynaptic neurons and the initiation of an action potential.

- Inhibitory synapse: Diminishes the probability of depolarization in postsynaptic neurons and the initiation of an action potential.

An influx of Na+ driven by excitatory neurotransmitters opens cation channels, depolarizing the postsynaptic membrane toward the action potential threshold. In contrast, inhibitory neurotransmitters cause the postsynaptic membrane to become less depolarized by opening either Cl- or K+ channels, reducing firing. Depending on their release location, the receptors they bind to, and the ionic circumstances they encounter, various transmitters can be either excitatory or inhibitory. For instance, acetylcholine can either excite or inhibit depending on the type of receptors it binds to.[27] For example, glutamate serves as an excitatory neurotransmitter, in contrast to GABA, which acts as an inhibitory neurotransmitter. Additionally, dopamine is a neurotransmitter that exerts dual effects, displaying both excitatory and inhibitory impacts through binding to distinct receptors.[28]

The membrane potential prevents Cl- from entering the cell, even when its concentration is much higher outside than inside. The reversal potential for Cl- in many neurons is quite negative, nearly equal to the resting potential. Opening Cl- channels tends to buffer the membrane potential, but this effect is countered when the membrane starts to depolarize, allowing more negatively charged Cl- ions to enter the cell. Consequently, it becomes more difficult to depolarize the membrane and excite the cell when Cl- channels are open. Similar effects result from the opening of K+ channels. The significance of inhibitory neurotransmitters is evident from the effects of toxins that impede their activity. For instance, strychnine binds to glycine receptors, blocking the action of glycine and leading to muscle spasms, convulsions, and death.[27]

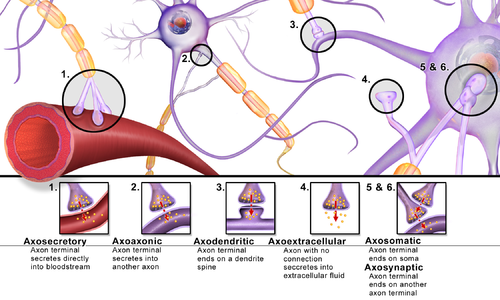

Interfaces

[edit]Synapses can be classified by the type of cellular structures serving as the pre- and post-synaptic components. The vast majority of synapses in the mammalian nervous system are classical axo-dendritic synapses (axon synapsing upon a dendrite), however, a variety of other arrangements exist. These include but are not limited to[clarification needed] axo-axonic, dendro-dendritic, axo-secretory, axo-ciliary,[29] somato-dendritic, dendro-somatic, and somato-somatic synapses.[citation needed]

In fact, the axon can synapse onto a dendrite, onto a cell body, or onto another axon or axon terminal, as well as into the bloodstream or diffusely into the adjacent nervous tissue.

Conversion of chemical into electrical signals

[edit]Neurotransmitters are tiny signal molecules stored in membrane-enclosed synaptic vesicles and released via exocytosis. A change in electrical potential in the presynaptic cell triggers the release of these molecules. By attaching to transmitter-gated ion channels, the neurotransmitter causes an electrical alteration in the postsynaptic cell and rapidly diffuses across the synaptic cleft. Once released, the neurotransmitter is swiftly eliminated, either by being absorbed by the nerve terminal that produced it, taken up by nearby glial cells, or broken down by specific enzymes in the synaptic cleft. Numerous Na+-dependent neurotransmitter carrier proteins recycle the neurotransmitters and enable the cells to maintain rapid rates of release.

At chemical synapses, transmitter-gated ion channels play a vital role in rapidly converting extracellular chemical impulses into electrical signals. These channels are located in the postsynaptic cell's plasma membrane at the synapse region, and they temporarily open in response to neurotransmitter molecule binding, causing a momentary alteration in the membrane's permeability. Additionally, transmitter-gated channels are comparatively less sensitive to the membrane potential than voltage-gated channels, which is why they are unable to generate self-amplifying excitement on their own. However, they result in graded variations in membrane potential due to local permeability, influenced by the amount and duration of neurotransmitter released at the synapse.[27]

Recently, mechanical tension, a phenomenon never thought relevant to synapse function has been found to be required for those on hippocampal neurons to fire.[30]

Release of neurotransmitters

[edit]Neurotransmitters bind to ionotropic receptors on postsynaptic neurons, either causing their opening or closing.[28] The variations in the quantities of neurotransmitters released from the presynaptic neuron may play a role in regulating the effectiveness of synaptic transmission. In fact, the concentration of cytoplasmic calcium is involved in regulating the release of neurotransmitters from presynaptic neurons.[31]

The chemical transmission involves several sequential processes:

- Synthesizing neurotransmitters within the presynaptic neuron.

- Loading the neurotransmitters into secretory vesicles.

- Controlling the release of neurotransmitters into the synaptic cleft.

- Binding of neurotransmitters to postsynaptic receptors.

- Ceasing the activity of the released neurotransmitters.[32]

Synaptic polarization

[edit]The function of neurons depends upon cell polarity. The distinctive structure of nerve cells allows action potentials to travel directionally (from dendrites to cell body down the axon), and for these signals to then be received and carried on by post-synaptic neurons or received by effector cells. Nerve cells have long been used as models for cellular polarization, and of particular interest are the mechanisms underlying the polarized localization of synaptic molecules. PIP2 signaling regulated by IMPase plays an integral role in synaptic polarity.

Phosphoinositides (PIP, PIP2, and PIP3) are molecules that have been shown to affect neuronal polarity.[33] A gene (ttx-7) was identified in Caenorhabditis elegans that encodes myo-inositol monophosphatase (IMPase), an enzyme that produces inositol by dephosphorylating inositol phosphate. Organisms with mutant ttx-7 genes demonstrated behavioral and localization defects, which were rescued by expression of IMPase. This led to the conclusion that IMPase is required for the correct localization of synaptic protein components.[34][35] The egl-8 gene encodes a homolog of phospholipase Cβ (PLCβ), an enzyme that cleaves PIP2. When ttx-7 mutants also had a mutant egl-8 gene, the defects caused by the faulty ttx-7 gene were largely reversed. These results suggest that PIP2 signaling establishes polarized localization of synaptic components in living neurons.[34]

Presynaptic modulation

[edit]Modulation of neurotransmitter release by G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) is a prominent presynaptic mechanism for regulation of synaptic transmission. The activation of GPCRs located at the presynaptic terminal, can decrease the probability of neurotransmitter release. This presynaptic depression involves activation of Gi/o-type G-proteins that mediate different inhibitory mechanisms, including inhibition of voltage-gated calcium channels, activation of potassium channels, and direct inhibition of the vesicle fusion process.

Endocannabinoids, synthesized in and released from postsynaptic neuronal elements and their cognate receptors, including the (GPCR) CB1 receptor located at the presynaptic terminal, are involved in this modulation by a retrograde signaling process, in which these compounds are synthesized in and released from postsynaptic neuronal elements and travel back to the presynaptic terminal to act on the CB1 receptor for short-term or long-term synaptic depression, that causes a short or long lasting decrease in neurotransmitter release.[36]

Effects of drugs on ligand-gated ion channels

[edit]Drugs have long been considered crucial targets for transmitter-gated ion channels. The majority of medications utilized to treat schizophrenia, anxiety, depression, and sleeplessness work at chemical synapses, and many of these pharmaceuticals function by binding to transmitter-gated channels. For instance, some drugs like barbiturates and tranquilizers bind to GABA receptors and enhance the inhibitory effect of GABA neurotransmitter. Thus, reduced concentration of GABA enables the opening of Cl- channels.

Furthermore, psychoactive drugs could potentially target many other synaptic signalling machinery components. Neurotransmitter release is a complex process involving various types of transporters and mechanisms for removing neurotransmitters from the synaptic cleft. While Na+-driven carriers play a role, other mechanisms are also involved, depending on the specific neurotransmitter system.[citation needed] For example, Prozac is an antidepressant medication that works by preventing the absorption of serotonin neurotransmitter. Also, other antidepressants operate by inhibiting the reabsorption of both serotonin and norepinephrine.[27]

Biogenesis

[edit]In nerve terminals, synaptic vesicles are produced quickly to compensate for their rapid depletion during neurotransmitter release. Their biogenesis involves segregating synaptic vesicle membrane proteins from other cellular proteins and packaging those distinct proteins into vesicles of appropriate size. Besides, it entails the endocytosis of synaptic vesicle membrane proteins from the plasma membrane.[37]

Synaptoblastic and synaptoclastic refer to synapse-producing and synapse-removing activities within the biochemical signalling chain. This terminology is associated with the Bredesen Protocol for treating Alzheimer's disease, which conceptualizes Alzheimer's as an imbalance between these processes. As of October 2023, studies concerning this protocol remain small and few results have been obtained within a standardized control framework.

Role in memory

[edit]Potentiation and depression

[edit]It is widely accepted that the synapse plays a key role in the formation of memory.[38] The stability of long-term memory can persist for many years; nevertheless, synapses, the neurological basis of memory, are very dynamic.[39] The formation of synaptic connections significantly depends on activity-dependent synaptic plasticity observed in various synaptic pathways. Indeed, the connection between memory formation and alterations in synaptic efficacy enables the reinforcement of neuronal interactions between neurons. As neurotransmitters activate receptors across the synaptic cleft, the connection between the two neurons is strengthened when both neurons are active at the same time, as a result of the receptor's signaling mechanisms. Memory formation involves complex interactions between neural pathways, including the strengthening and weakening of synaptic connections, which contribute to the storage of information.[40] This process of synaptic strengthening is known as long-term potentiation (LTP).[38]

By altering the release of neurotransmitters, the plasticity of synapses can be controlled in the presynaptic cell. The postsynaptic cell can be regulated by altering the function and number of its receptors. Changes in postsynaptic signaling are most commonly associated with a N-methyl-d-aspartic acid receptor (NMDAR)-dependent LTP and long-term depression (LTD) due to the influx of calcium into the post-synaptic cell, which are the most analyzed forms of plasticity at excitatory synapses.[41]

Mechanism of protein kinase

[edit]Moreover, Ca2+/calmodulin (CaM)-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) is best recognized for its roles in the brain, particularly in the neocortex and hippocampal regions because it serves as a ubiquitous mediator of cellular Ca2+ signals. CaMKII is abundant in the nervous system, mainly concentrated in the synapses in the nerve cells. Indeed, CaMKII has been definitively identified as a key regulator of cognitive processes, such as learning, and neural plasticity. The first concrete experimental evidence for the long-assumed function of CaMKII in memory storage was demonstrated

While Ca2+/CaM binding stimulates CaMKII activity, Ca2+-independent autonomous CaMKII activity can also be produced by a number of other processes. CaMKII becomes active by autophosphorylating itself upon Ca2+/calmodulin binding. CaMKII is still active and phosphorylates itself even after Ca2+ is cleaved; as a result, the brain stores long-term memories using this mechanism. Nevertheless, when the CaMKII enzyme is dephosphorylated by a phosphatase enzyme, it becomes inactive, and memories are lost. Hence, CaMKII plays a vital role in both the induction and maintenance of LTP.[42]

Synaptic Computation

[edit]Beyond serving as passive relays, synapses perform complex computations on incoming signals. Models of synaptic computation describe how neurotransmitter release kinetics, receptor subunit composition, and short‑term plasticity endow individual synapses with filtering, gain control, and temporal integration capabilities. Recent connectomic and functional studies—such as those reconstructing the larval zebrafish brainstem circuit—demonstrate that synaptic wiring diagrams can predict behaviorally relevant neural codes, underscoring the computational role of synaptic networks in information processing.[43]

Experimental models

[edit]For technical reasons, synaptic structure and function have been historically studied at unusually large model synapses, for example:

- Squid giant synapse

- Neuromuscular junction (NMJ), a cholinergic synapse in vertebrates, glutamatergic in insects

- Ciliary calyx in the ciliary ganglion of chicks[44]

- Calyx of Held in the brainstem

- Ribbon synapse in the retina

- Schaffer collateral synapses in the hippocampus. These synapses are small, but their pre- and postsynaptic neurons are well separated (CA3 and CA1, respectively).

Clinical Relevance

[edit]Synaptic dysfunction and loss are now recognized as central to the pathophysiology of major neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental disorders. In Alzheimer's disease (AD), synapse loss correlates more strongly with cognitive decline than amyloid‑β plaque burden, and emerging biomarkers—such as the YWHAG:NPTX2 ratio in cerebrospinal fluid and plasma—offer prognostic value for AD onset and progression. Synaptic pathology in AD encompasses alterations in glutamatergic transmission, dendritic spine density, and synaptic protein turnover, highlighting synapses both as early indicators of disease and as targets for therapeutic intervention.[45][46]

Synaptic disruptions can lead to a variety of negative effects, including impaired learning, memory, and cognitive function.[47] In fact, alterations in cell-intrinsic molecular systems or modifications to environmental biochemical processes can lead to synaptic dysfunction. The synapse is the primary unit of information transfer in the nervous system, and correct synaptic contact creation during development is essential for normal brain function. Genetic mutations can disrupt synapse formation and function, contributing to the development of neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders.[48] However, the precise relationship between specific mutations and disease phenotypes is complex and requires further investigation.

Synaptic defects are causally associated with early appearing neurological diseases, including autism spectrum disorders (ASD), schizophrenia (SCZ), and bipolar disorder (BP). Synaptic dysfunction, or synaptopathy, is often implicated in late-onset neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and Huntington's, but the exact mechanisms contributing to this phenomenon are not fully understood.[49] These diseases are identified by a gradual loss in cognitive and behavioral function and a steady loss of brain tissue. Moreover, these deteriorations have been mostly linked to the gradual build-up of protein aggregates in neurons, the composition of which may vary based on the pathology; all have the same deleterious effects on neuronal integrity. Furthermore, the high number of mutations linked to synaptic structure and function, as well as dendritic spine alterations in post-mortem tissue, has led to the association between synaptic defects and neurodevelopmental disorders, such as ASD and SCZ, characterized by abnormal behavioral or cognitive phenotypes.

Nevertheless, due to limited access to human tissue at late stages and a lack of thorough assessment of the essential components of human diseases in the available experimental animal models, it has been difficult to fully grasp the origin and role of synaptic dysfunction in neurological disorders.[50]

Additional images

[edit]-

Diagram of the synapse. Please see learnbio.org for interactive version.

-

A typical central nervous system synapse

-

The synapse and synaptic vesicle cycle

-

Major elements in chemical synaptic transmission

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Foster M, Sherrington CS (1897). Textbook of Physiology. Vol. 3 (7th ed.). London: Macmillan. p. 929. ISBN 978-1-4325-1085-5.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Bennett MV (1966). "PHYSIOLOGY OF ELECTROTONIC JUNCTIONS*". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 137 (2): 509–539. Bibcode:1966NYASA.137..509B. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1966.tb50178.x. ISSN 0077-8923. PMID 5229812.

- ^ Kandel ER, ed. (2013). Principles of neural science (5th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-139011-8.

- ^ Purves D, Williams SM, eds. (2004). Neuroscience (3rd ed.). Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 978-0-87893-725-7.

- ^ Bennett MV, Zukin R (2004). "Electrical Coupling and Neuronal Synchronization in the Mammalian Brain". Neuron. 41 (4): 495–511. doi:10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00043-1. ISSN 0896-6273. PMID 14980200.

- ^ Makarenko V, Llinás R (1998-12-22). "Experimentally determined chaotic phase synchronization in a neuronal system". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 95 (26): 15747–15752. Bibcode:1998PNAS...9515747M. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.26.15747. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 28115. PMID 9861041.

- ^ Korn H, Faure P (2003). "Is there chaos in the brain? II. Experimental evidence and related models". Comptes Rendus. Biologies (in French). 326 (9): 787–840. doi:10.1016/j.crvi.2003.09.011. ISSN 1768-3238. PMID 14694754.

- ^ Connors BW, Long MA (2004-07-21). "Electrical Synapses in the Mammalian Brain". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 27 (1): 393–418. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.041002.131128. ISSN 0147-006X.

- ^ Apodaca RL (2006-09-08). "Chemical Reviews on Wikipedia". doi:10.59350/t7n8f-bm508.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Perea G, Navarrete M, Araque A (August 2009). "Tripartite synapses: astrocytes process and control synaptic information". Trends in Neurosciences. 32 (8). Cell Press: 421–431. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2009.05.001. PMID 19615761. S2CID 16355401.

- ^ a b c Südhof TC (July 2021). "The cell biology of synapse formation". The Journal of Cell Biology. 220 (7) e202103052. doi:10.1083/jcb.202103052. PMC 8186004. PMID 34086051.

- ^ Johansen A, Beliveau V, Colliander E, Raval NR, Dam VH, Gillings N, Aznar S, Svarer C, Plavén-Sigray P, Knudsen GM (2024-08-14). "An In Vivo High-Resolution Human Brain Atlas of Synaptic Density". Journal of Neuroscience. 44 (33). doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1750-23.2024. ISSN 0270-6474. PMC 11326867. PMID 38997157.

- ^ Missler M, Südhof TC, Biederer T (April 2012). "Synaptic cell adhesion". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 4 (4) a005694. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a005694. PMC 3312681. PMID 22278667.

- ^ Hale WD, Südhof TC, Huganir RL (January 2023). "Engineered adhesion molecules drive synapse organization". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 120 (3) e2215905120. Bibcode:2023PNAS..12015905H. doi:10.1073/pnas.2215905120. PMC 9934208. PMID 36638214.

- ^ Elias LJ, Saucier DM (2006). Neuropsychology: Clinical and Experimental Foundations. Boston: Pearson/Allyn & Bacon. ISBN 978-0-20534361-4. LCCN 2005051341. OCLC 61131869.

- ^ a b Harper D. "synapse". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Tansey EM (1997). "Not committing barbarisms: Sherrington and the synapse, 1897". Brain Research Bulletin. 44 (3). Elsevier: 211–212. doi:10.1016/S0361-9230(97)00312-2. PMID 9323432. S2CID 40333336.

The word synapse first appeared in 1897, in the seventh edition of Michael Foster's Textbook of Physiology.

- ^ σύναψις, συνάπτειν, σύν, ἅπτειν. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ De Robertis ED, Bennett HS (January 1955). "Some features of the submicroscopic morphology of synapses in frog and earthworm". The Journal of Biophysical and Biochemical Cytology. 1 (1): 47–58. doi:10.1083/jcb.1.1.47. PMC 2223594. PMID 14381427.

- ^ Palay SL, Palade GE (January 1955). "The fine structure of neurons". The Journal of Biophysical and Biochemical Cytology. 1 (1): 69–88. doi:10.1083/jcb.1.1.69. PMC 2223597. PMID 14381429.

- ^ Palay SL (July 1956). "Synapses in the central nervous system". The Journal of Biophysical and Biochemical Cytology. 2 (4 Suppl): 193–202. doi:10.1083/jcb.2.4.193. PMC 2229686. PMID 13357542.

- ^ a b Silverthorn DU (2007). Human Physiology: An Integrated Approach (4th ed.). San Francisco: Pearson/Benjamin Cummings. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-8053-6851-2. LCCN 2005056517. OCLC 62742632.

- ^ a b Pereda AE (April 2014). "Electrical synapses and their functional interactions with chemical synapses". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 15 (4): 250–263. doi:10.1038/nrn3708. PMC 4091911. PMID 24619342.

- ^ Caire MJ, Reddy V, Varacallo M (2023). "Physiology, Synapse". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30252303. Retrieved 2024-01-01.

- ^ Sotelo C, Palay SL (February 1970). "The fine structure of the later vestibular nucleus in the rat. II. Synaptic organization". Brain Research. 18 (1): 93–115. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(70)90459-2. PMID 4313893.

- ^ Strausfeld NJ, Bassemir UK (December 1983). "Cobalt-coupled neurons of a giant fibre system in Diptera". Journal of Neurocytology. 12 (6): 971–91. doi:10.1007/BF01153345. PMID 6420522. S2CID 19764983.

- ^ a b c d Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P (2002). "Ion Channels and the Electrical Properties of Membranes". Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). Garland Science. Retrieved 2024-01-20.

- ^ a b Lasica A, Brewer C (2023). "Excitatory and Inhibitory Synaptic Signalling". TeachMePhysiology.

- ^ Sheu SH, Upadhyayula S, Dupuy V, Pang S, Deng F, Wan J, et al. (September 2022). "A serotonergic axon-cilium synapse drives nuclear signaling to alter chromatin accessibility". Cell. 185 (18): 3390–3407.e18. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2022.07.026. PMC 9789380. PMID 36055200. S2CID 251958800.

- University press release: "Scientists discover new kind of synapse in neurons' tiny hairs". Howard Hughes Medical Institute via phys.org. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- ^ Joy MS, Nall DL, Emon B, Lee KY, Barishman A, Ahmed M, Rahman S, Selvin PR, Saif MT (2023-12-26). "Synapses without tension fail to fire in an in vitro network of hippocampal neurons". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 120 (52) e2311995120. Bibcode:2023PNAS..12011995J. doi:10.1073/pnas.2311995120. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 10756289. PMID 38113266.

- ^ Pitman RM (September 1984). "The versatile synapse". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 112 (1): 199–224. Bibcode:1984JExpB.112..199P. doi:10.1242/jeb.112.1.199. PMID 6150966.

- ^ Holz RW, Fisher SK (1999). "Synaptic Transmission". In Siegel GJ, Agranoff BW, Albers RW, Fisher SK, Uhler MD (eds.). Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular and Medical Aspects (6th ed.). Lippincott-Raven. Retrieved 2024-01-04.

- ^ Arimura N, Kaibuchi K (December 2005). "Key regulators in neuronal polarity". Neuron. 48 (6). Cell Press: 881–884. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2005.11.007. PMID 16364893.

- ^ a b Kimata T, Tanizawa Y, Can Y, Ikeda S, Kuhara A, Mori I (June 2012). "Synaptic polarity depends on phosphatidylinositol signaling regulated by myo-inositol monophosphatase in Caenorhabditis elegans". Genetics. 191 (2). Genetics Society of America: 509–521. doi:10.1534/genetics.111.137844. PMC 3374314. PMID 22446320.

- ^ Tanizawa Y, Kuhara A, Inada H, Kodama E, Mizuno T, Mori I (December 2006). "Inositol monophosphatase regulates localization of synaptic components and behavior in the mature nervous system of C. elegans". Genes & Development. 20 (23). Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: 3296–3310. doi:10.1101/gad.1497806. PMC 1686606. PMID 17158747.

- ^ Lovinger DM (2008). "Presynaptic Modulation by Endocannabinoids". In Südhof TC, Starke K (eds.). Pharmacology of Neurotransmitter Release. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Vol. 184. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 435–477. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-74805-2_14. ISBN 978-3-540-74805-2. PMID 18064422.

- ^ Desnos C, Clift-o'Grady L, Kelly RB (1995-09-01). "Biogenesis of synaptic vesicles in vitro". The Journal of Cell Biology. 130 (5): 1041–1049. doi:10.1083/jcb.130.5.1041. ISSN 0021-9525. PMC 2120557. PMID 7544795.

- ^ a b Lynch MA (January 2004). "Long-term potentiation and memory". Physiological Reviews. 84 (1): 87–136. doi:10.1152/physrev.00014.2003. PMID 14715912.

- ^ Yang Y, Lu J, Zuo Y (December 2018). "Changes of synaptic structures associated with learning, memory and diseases". Brain Science Advances. 4 (2): 99–117. doi:10.26599/BSA.2018.2018.9050012.

- ^ Deason H (1966-08-12). "Science and Technology Supplements: The McGraw-Hill Yearbook of Science and Technology . David I. Eggenberger, Exec. Ed. McGraw-Hill, New York, 1966. 461 pp. Illus. $24.; McGraw-Hili Modern Men of Science . Jay E. Greene, Ed. McGrawHill, New York, 1966. 630 pp. Illus. $19.50.; McGraw-Hill Basic Bibliography of Science and Technology . David I. Eggenberger, Exec. Ed. McGraw-Hill, New York, 1966. 748 pp. $19.50". Science. 153 (3737): 731. doi:10.1126/science.153.3737.731. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ^ Krugers HJ, Zhou M, Joëls M, Kindt M (October 11, 2011). "Regulation of excitatory synapses and fearful memories by stress hormones". Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 5. Frontiers Media SA: 62. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2011.00062. PMC 3190121. PMID 22013419.

- ^ Bayer KU, Schulman H (August 2019). "CaM Kinase: Still Inspiring at 40". Neuron. 103 (3): 380–394. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2019.05.033. PMC 6688632. PMID 31394063.

- ^ Martínez De Fabricius AL, Maidana N, Gómez N, Sabater S (2003). "Distribution patterns of benthic diatoms in a Pampean river exposed to seasonal floods: The Cuarto River (Argentina)". Biodiversity and Conservation. 12 (12): 2443–2454. Bibcode:2003BiCon..12.2443M. doi:10.1023/a:1025857715437. ISSN 0960-3115.

- ^ Stanley EF (1992). "The calyx-type synapse of the chick ciliary ganglion as a model of fast cholinergic transmission". Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 70 (Suppl): S73 – S77. doi:10.1139/y92-246. PMID 1338300.

- ^ Terry N, Masliah A, Overk C, Masliah E (2019-08-03). "Remembering Robert D. Terry at a Time of Change in the World of Alzheimer's Disease". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 70 (3): 621–628. doi:10.3233/jad-190518. ISSN 1387-2877. PMC 6750985. PMID 31282421.

- ^ Chen YH, Wang ZB, Liu XP, Mao ZQ (2025-03-19). "Cerebrospinal fluid LMO4 as a synaptic biomarker linked to Alzheimer's disease pathology and cognitive decline". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 105: 216–227. doi:10.1177/13872877251326286. ISSN 1387-2877. PMID 40105503.

- ^ Hayes BK, Heit E (August 2004). "Why learning and development can lead to poorer recognition memory". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 8 (8): 337–339. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2004.05.001. ISSN 1364-6613. PMID 15335459.

- ^ Südhof TC (2021-07-05). "The cell biology of synapse formation". Journal of Cell Biology. 220 (7) e202103052. doi:10.1083/jcb.202103052. ISSN 0021-9525. PMC 8186004. PMID 34086051.

- ^ Missler M, Sudhof TC, Biederer T (2012-04-01). "Synaptic Cell Adhesion". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 4 (4) a005694. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a005694. ISSN 1943-0264. PMC 3312681. PMID 22278667.

- ^ Taoufik E, Kouroupi G, Zygogianni O, Matsas R (2018-09-05). "Synaptic dysfunction in neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental diseases: an overview of induced pluripotent stem-cell-based disease models". Open Biology. 8 (9) 180138. doi:10.1098/rsob.180138. ISSN 2046-2441. PMC 6170506. PMID 30185603.