Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Propulsion

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2017) |

Propulsion is the generation of force by any combination of pushing or pulling to modify the translational motion of an object, which is typically a rigid body (or an articulated rigid body) but may also concern a fluid.[1] The term is derived from two Latin words: pro, meaning before or forward; and pellere, meaning to drive.[2] A propulsion system consists of a source of mechanical power, and a propulsor (means of converting this power into propulsive force).

Plucking a guitar string to induce a vibratory translation is technically a form of propulsion of the guitar string; this is not commonly depicted in this vocabulary, even though human muscles are considered to propel the fingertips. The motion of an object moving through a gravitational field is affected by the field, and within some frames of reference physicists speak of the gravitational field generating a force upon the object, but for deep theoretic reasons, physicists now consider the curved path of an object moving freely through space-time as shaped by gravity as a natural movement of the object, unaffected by a propulsive force (in this view, the falling apple is considered to be unpropelled, while the observer of the apple standing on the ground is considered to be propelled by the reactive force of the Earth's surface).

Biological propulsion systems use an animal's muscles as the power source, and limbs such as wings, fins or legs as the propulsors. A technological system uses an engine or motor as the power source (commonly called a powerplant), and wheels and axles, propellers, or a propulsive nozzle to generate the force. Components such as clutches or gearboxes may be needed to connect the motor to axles, wheels, or propellers. A technological/biological system may use human, or trained animal, muscular work to power a mechanical device.

Influencing rotational motion is also technically a form of propulsion, but in speech, an automotive mechanic might prefer to describe the hot gasses in an engine cylinder as propelling the piston (translational motion), which drives the crankshaft (rotational motion), the crankshaft then drives the wheels (rotational motion), and the wheels propel the car forward (translational motion). In common speech, propulsion is associated with spatial displacement more strongly than locally contained forms of motion, such as rotation or vibration. As another example, internal stresses in a rotating baseball cause the surface of the baseball to travel along a sinusoidal or helical trajectory, which would not happen in the absence of these interior forces; these forces meet the technical definition of propulsion from Newtonian mechanics, but are not commonly spoken of in this language.

Vehicular propulsion

[edit]Air propulsion

[edit]

An aircraft propulsion system generally consists of an aircraft engine and some means to generate thrust, such as a propeller or a propulsive nozzle.

An aircraft propulsion system must achieve two things. First, the thrust from the propulsion system must balance the drag of the airplane when the airplane is cruising. And second, the thrust from the propulsion system must exceed the drag of the airplane for the airplane to accelerate. The greater the difference between the thrust and the drag, called the excess thrust, the faster the airplane will accelerate.[2]

Some aircraft, like airliners and cargo planes, spend most of their life in a cruise condition. For these airplanes, excess thrust is not as important as high engine efficiency and low fuel usage. Since thrust depends on both the amount of gas moved and the velocity, we can generate high thrust by accelerating a large mass of gas by a small amount, or by accelerating a small mass of gas by a large amount. Because of the aerodynamic efficiency of propellers and fans, it is more fuel efficient to accelerate a large mass by a small amount, which is why high-bypass turbofans and turboprops are commonly used on cargo planes and airliners.[2]

Some aircraft, like fighter planes or experimental high speed aircraft, require very high excess thrust to accelerate quickly and to overcome the high drag associated with high speeds. For these airplanes, engine efficiency is not as important as very high thrust. Modern combat aircraft usually have an afterburner added to a low bypass turbofan. Future hypersonic aircraft may use some type of ramjet or rocket propulsion.[2]

Ground

[edit]

Ground propulsion is any mechanism for propelling solid objects along the ground, usually for the purposes of transportation. The propulsion system often consists of a combination of an engine or motor, a gearbox and wheel and axles in standard applications.

The development of the steam engine and internal combustion engine allowed for the development of rail vehicles and motor vehicles, all of which have some form of a powertrain. The electric motor allowed for quieter vehicles with lower emissions, and frequently higher engine efficiency.

Maglev

[edit]

Maglev (derived from magnetic levitation) is a system of transportation that uses magnetic levitation to suspend, guide and propel vehicles with magnets rather than using mechanical methods, such as wheels, axles and bearings. With maglev a vehicle is levitated a short distance away from a guide way using magnets to create both lift and thrust. Maglev vehicles are claimed to move more smoothly and quietly and to require less maintenance than wheeled mass transit systems. It is claimed that non-reliance on friction also means that acceleration and deceleration can far surpass that of existing forms of transport. The power needed for levitation is not a particularly large percentage of the overall energy consumption; most of the power used is needed to overcome air resistance (drag), as with any other high-speed form of transport.

Marine

[edit]

Marine propulsion is the mechanism or system used to generate thrust to move a ship or boat across water. While paddles and sails are still used on some smaller boats, most modern ships are propelled by mechanical systems consisting of a motor or engine turning a propeller, or less frequently, in jet drives, an impeller. Marine engineering is the discipline concerned with the design of marine propulsion systems.

Steam engines were the first mechanical engines used in marine propulsion, but have mostly been replaced by two-stroke or four-stroke diesel engines, outboard motors, and gas turbine engines on faster ships. Nuclear reactors producing steam are used to propel warships and icebreakers, and there have been attempts to utilize them to power commercial vessels. Electric motors have been used on submarines and electric boats and have been proposed for energy-efficient propulsion.[3] Recent development in liquified natural gas (LNG) fueled engines are gaining recognition for their low emissions and cost advantages.

Space

[edit]

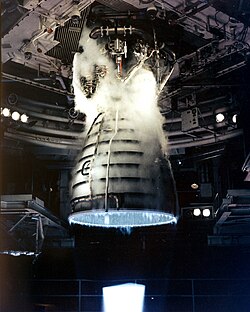

Spacecraft propulsion is any method used to accelerate spacecraft and artificial satellites. There are many different methods including pumps.[4] Each method has drawbacks and advantages, and spacecraft propulsion is an active area of research. However, most spacecraft today are propelled by forcing a gas from the back/rear of the vehicle at very high speed through a supersonic de Laval nozzle. This sort of engine is called a rocket engine.

All current spacecraft use chemical rockets (bipropellant or solid-fuel) for launch, though some (such as the Pegasus rocket and SpaceShipOne) have used air-breathing engines on their first stage. Most satellites have simple reliable chemical thrusters (often monopropellant rockets) or resistojet rockets for orbital station-keeping and some use momentum wheels for attitude control. Soviet bloc satellites have used electric propulsion for decades, and newer Western geo-orbiting spacecraft are starting to use them for north–south stationkeeping and orbit raising. Interplanetary vehicles mostly use chemical rockets as well, although a few have used ion thrusters and Hall-effect thrusters (two different types of electric propulsion) to great success.

Cable

[edit]A cable car is any of a variety of transportation systems relying on cables to pull vehicles along or lower them at a steady rate. The terminology also refers to the vehicles on these systems. The cable car vehicles are motor-less and engine-less and they are pulled by a cable that is rotated by a motor off-board.

Animal

[edit]

Animal locomotion, which is the act of self-propulsion by an animal, has many manifestations, including running, swimming, jumping and flying. Animals move for a variety of reasons, such as to find food, a mate, or a suitable microhabitat, and to escape predators. For many animals the ability to move is essential to survival and, as a result, selective pressures have shaped the locomotion methods and mechanisms employed by moving organisms. For example, migratory animals that travel vast distances (such as the Arctic tern) typically have a locomotion mechanism that costs very little energy per unit distance, whereas non-migratory animals that must frequently move quickly to escape predators (such as frogs) are likely to have costly but very fast locomotion. The study of animal locomotion is typically considered to be a sub-field of biomechanics.

Locomotion requires energy to overcome friction, drag, inertia, and gravity, though in many circumstances some of these factors are negligible. In terrestrial environments gravity must be overcome, though the drag of air is much less of an issue. In aqueous environments however, friction (or drag) becomes the major challenge, with gravity being less of a concern. Although animals with natural buoyancy need not expend much energy maintaining vertical position, some will naturally sink and must expend energy to remain afloat. Drag may also present a problem in flight, and the aerodynamically efficient body shapes of birds highlight this point. Flight presents a different problem from movement in water however, as there is no way for a living organism to have lower density than air. Limbless organisms moving on land must often contend with surface friction, but do not usually need to expend significant energy to counteract gravity.

Newton's third law of motion is widely used in the study of animal locomotion: if at rest, to move forward an animal must push something backward. Terrestrial animals must push the solid ground; swimming and flying animals must push against a fluid (either water or air).[5] The effect of forces during locomotion on the design of the skeletal system is also important, as is the interaction between locomotion and muscle physiology, in determining how the structures and effectors of locomotion enable or limit animal movement.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Wragg, David W. (1974). A Dictionary of Aviation (1st American ed.). New York: Frederick Fell, Inc. p. 216. ISBN 0-85045-163-9.

- ^ a b c d "Beginner's Guide to Propulsion NASA".

- ^ "Energy Efficient - All Electric Ship". Archived from the original on 2009-05-17. Retrieved 2009-11-25.

- ^ Hall, Nancy. "Propulsion System". NASA – Glenn Research. Retrieved November 11, 2025.

- ^ Biewener, Andrew A. (2003-06-19). Animal Locomotion. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-850022-3.

External links

[edit] Media related to Propulsion at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Propulsion at Wikimedia Commons

- Pickering, Steve (2009). "Propulsion Efficiency". Sixty Symbols. Brady Haran from the University of Nottingham.

Propulsion

View on GrokipediaFundamentals of Propulsion

Definition and Principles

Propulsion is the process of generating a force, known as thrust, to drive or propel an object forward through a medium such as air or water, or in the vacuum of space. This action involves accelerating a working fluid or mass to produce motion, distinguishing it from traction-based movement, which depends on friction or direct contact with a surface for locomotion, such as wheels gripping a road.[1][5] The historical roots of propulsion concepts date to ancient mechanical principles, including Archimedes' work on levers in the 3rd century BCE, which demonstrated force amplification for moving objects and influenced later engineering designs. In the 17th century, Isaac Newton's laws of motion formalized the scientific foundations, with the second law linking force to the product of mass and acceleration, and the third law explaining action-reaction pairs critical to many propulsion mechanisms. Practical advancements emerged in the 18th and 19th centuries, exemplified by James Watt's 1769 patent for an improved steam engine, which doubled efficiency over prior designs and powered early industrial and transport applications.[6][7][8] The scope of propulsion spans diverse systems, including mechanical devices like steam or internal combustion engines, chemical reactions in rockets, electrical methods such as ion drives, and biological processes involving muscle contraction, though the focus here excludes in-depth biological details or specific vehicle implementations. At its core, propulsion adheres to Newton's second law, , where thrust accelerates the propelled mass at rate ; in practice, this often entails a mass flow rate that, when accelerated (e.g., via expulsion or fluid interaction), generates the net forward force without relying on constant mass.[3][9] Systems may briefly reference reaction propulsion, which expels mass for thrust via action-reaction, versus non-reaction types interacting with an external medium, though specifics are addressed elsewhere.[10]Thrust Generation

Thrust in propulsion systems arises as a reaction force, governed by the conservation of momentum principle, which states that the total momentum of a closed system remains constant unless acted upon by external forces. In a propulsion context, this manifests when a system expels mass (such as exhaust gases) at high velocity, imparting an equal and opposite momentum change to the vehicle, thereby generating forward thrust. The impulse-momentum theorem quantifies this relationship as , where is the change in momentum, is the thrust force, and is the time interval; for continuous operation, thrust equals the rate of momentum change, , with as the mass flow rate and as the exhaust velocity relative to the vehicle.[11][12] Energy sources for propulsion convert stored potential into kinetic energy to accelerate the expelled mass. Chemical energy, derived from fuel combustion, dominates traditional systems by rapidly releasing thermal energy to heat and expand propellants. Electrical energy, from batteries or motors, powers ion thrusters by accelerating charged particles electrostatically. Nuclear energy, via fission reactors, provides sustained thermal or electrical output for high-efficiency drives, while solar energy, captured by photovoltaic arrays, enables low-thrust electric propulsion in sunlit regions. These conversions are limited by the source's energy density and the system's ability to direct output into directed momentum.[13][14] Propulsive efficiency measures how effectively thrust propels the vehicle relative to total energy input, defined for many systems as , where is the vehicle speed and is the exhaust velocity; this peaks near , balancing kinetic energy loss in the wake. Specific impulse , a key performance metric, quantifies efficiency as , with as standard gravity (9.81 m/s²), representing thrust per unit propellant weight flow and often expressed in seconds; higher indicates better fuel economy, as in ion engines exceeding 3000 s versus chemical rockets around 450 s.[15][16] Thrust magnitude depends on the surrounding medium's density, which influences mass intake and exhaust dynamics in fluid-based systems, reducing effective thrust in low-density environments like high altitudes. Temperature affects gas expansion and molecular speeds, altering exhaust velocity and thus momentum transfer, while drag from the medium opposes net forward force, requiring higher thrust to maintain velocity. The power-to-weight ratio, critical for system viability, is calculated as , where is power output, is weight, is mass, and is speed; this ratio determines acceleration capability, with values above 1 enabling rapid maneuvers in aerospace applications.[17][18]Propulsion by Reaction

Jet Propulsion

Jet propulsion operates by accelerating a mass of ambient fluid, typically air in atmospheric conditions, rearward to generate forward thrust through Newton's third law. In gas turbine-based systems, the core mechanism involves four primary stages: intake, where air is drawn into the engine; compression, where the air is pressurized by rotating blades; combustion, where fuel is injected and ignited to heat the compressed air at nearly constant pressure; and exhaust, where the high-energy gases expand through a turbine and nozzle to produce thrust. This process follows the Brayton thermodynamic cycle, which models the ideal operation of such engines. The cycle consists of isentropic compression (increasing pressure and temperature without heat transfer), isobaric heat addition (combustion raising temperature at constant pressure), isentropic expansion (extracting work in the turbine), and isobaric heat rejection (exhaust cooling). On a pressure-volume (p-V) diagram, the cycle appears as a closed loop: process 1-2 (isentropic compression) follows an adiabatic curve upward to higher pressure and lower volume; 2-3 (isobaric heat addition) moves horizontally rightward at constant pressure to larger volume; 3-4 (isentropic expansion) curves downward to lower pressure and larger volume; and 4-1 (isobaric heat rejection) returns horizontally leftward to the starting point. The enclosed area represents the net work output, which translates to thrust in propulsion applications.[19] The thrust generated by a jet engine derives from the conservation of momentum applied to the fluid flow through the engine. Considering a control volume around the engine, the net force (thrust) equals the rate of momentum outflow minus inflow, plus any pressure imbalance at the exit. For steady flow, this yields the general thrust equation: where is the mass flow rate, is the velocity (with subscripts for exhaust and for inlet), is pressure, and is the exhaust area. In most jet engines, due to fuel mass being negligible, simplifying to . This equation highlights that thrust increases with higher exhaust velocity relative to inlet velocity and mass flow, optimized by the engine's thermodynamic efficiency.[11] Common types of jet engines include the turbojet, which provides pure reaction thrust by accelerating all ingested air through the core for high-speed performance; the turbofan, which improves efficiency by bypassing a portion of the air around the core via a large front fan, reducing noise and fuel use for subsonic to transonic flight; and the ramjet, a supersonic variant with no moving parts, where incoming air is compressed solely by the vehicle's high speed (typically above Mach 2) before combustion and exhaust. The turbofan dominates modern civil aviation due to its bypass ratio enhancing propulsive efficiency, while ramjets suit specialized high-speed applications. The pioneering flight of a jet-powered aircraft occurred on May 15, 1941, using Frank Whittle's turbojet engine in the Gloster E.28/39, marking the practical realization of continuous combustion propulsion.[20][21] Jet propulsion finds primary application in aircraft, where efficiency peaks at flight speeds from Mach 0.8 (high subsonic) for turbofans to Mach 2.0 (supersonic) for turbojets and ramjets, balancing thermodynamic and propulsive efficiencies before drag rises sharply. Thrust-specific fuel consumption (TSFC), defined as fuel mass flow rate per unit thrust (typically in lb/(lbf·h)), serves as a key efficiency metric; for example, modern high-bypass turbofans achieve TSFC around 0.5, enabling long-range commercial flights, while turbojets exhibit higher values (0.8–1.0) suited to military intercepts. These systems excel in atmospheric media by leveraging ambient air, contrasting with self-contained alternatives.[22][23]Rocket Propulsion

Rocket propulsion relies on the reaction principle, where thrust is generated by expelling high-velocity exhaust gases produced from the combustion of self-contained propellants, making it ideal for operation in the vacuum of space or at high altitudes without reliance on atmospheric oxygen.[24] In a typical chemical rocket engine, liquid or solid propellants consisting of fuel and oxidizer are mixed and ignited in a combustion chamber, creating hot, high-pressure gases that are accelerated through a nozzle to produce directed exhaust.[24] The de Laval nozzle, a converging-diverging design, optimizes this process by first constricting the flow to sonic speeds at the throat (Mach 1) and then expanding it supersonically in the diverging section, converting thermal energy into kinetic energy for maximum exhaust velocity while minimizing losses.[25] This mechanism enables efficient thrust generation, with the nozzle's expansion ratio tailored to ambient pressure conditions—higher ratios for vacuum performance.[25] Rocket engines are classified by propellant type and energy source, each suited to specific mission profiles emphasizing high thrust for launch or sustained low-thrust efficiency for deep space. Solid rocket engines use a pre-mixed solid propellant grain that burns progressively from the surface, offering simplicity, high initial thrust-to-weight ratios, and reliability but lacking throttle or restart capability once ignited.[26] Liquid bipropellant engines, such as those using liquid oxygen (LOX) and refined petroleum (RP-1), provide high controllability through separate storage and pumped delivery of fuel and oxidizer, allowing throttling, restart, and precise mixture ratios for optimized performance.[26] Hybrid engines combine a solid fuel grain with a liquid or gaseous oxidizer, inheriting safety and storability from solids while enabling throttling by controlling oxidizer flow, though they generally offer moderate efficiency without superior thrust over pure chemical variants.[26] Electric variants, including ion thrusters and Hall effect thrusters, ionize and accelerate propellants like xenon using electrostatic or electromagnetic fields, delivering low thrust (0.1–55 mN) but exceptionally high specific impulse (200–3,000 seconds) for fuel-efficient, long-duration maneuvers in space.[4] The performance of rocket propulsion is fundamentally described by the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation, which quantifies the maximum change in velocity (Δv) achievable from a given propellant mass: Here, is the effective exhaust velocity (related to specific impulse by , where is standard gravity), is the initial total mass (structure plus propellants), and is the final mass after propellant expulsion.[27] To derive this, consider conservation of momentum for a rocket in free space (neglecting gravity and drag): the instantaneous thrust equals the rate of momentum change, , where mass decreases as propellant is ejected (). Rearranging gives ; integrating from initial velocity and mass to final and yields .[28] For multi-stage rockets, which mitigate the equation's mass ratio limitations by discarding empty stages, the total Δv is the sum of each stage's contribution: , where each stage's initial mass includes subsequent stages, enabling greater overall velocity for missions like orbital insertion.[28] Historical advancements underscore rocket propulsion's evolution from experimental devices to reusable systems. Robert H. Goddard achieved the first liquid-fueled rocket flight on March 16, 1926, at his aunt's farm in Auburn, Massachusetts, where a 10-foot-tall device using gasoline and liquid oxygen reached 41 feet in 2.5 seconds, demonstrating controlled combustion and nozzle expansion.[29] During World War II, Wernher von Braun's team developed the V-2 (A-4) as the first long-range ballistic missile, with operational launches beginning in September 1944 from mobile sites in occupied Europe, such as near The Hague in the Netherlands, achieving ranges up to 320 km using a 25-ton-thrust alcohol-liquid oxygen engine and de Laval nozzle for supersonic exhaust.[30] In modern applications, SpaceX's Falcon 9 demonstrated reusability on December 21, 2015, during the ORBCOMM-2 mission, when its first-stage booster successfully landed vertically after orbital insertion, powered by nine Merlin engines using LOX/RP-1, reducing launch costs through propellant-efficient recovery. Since 2015, SpaceX has achieved over 300 successful first-stage landings as of November 2025, with ongoing development of fully reusable systems like Starship aimed at reducing costs for interplanetary missions.[31][32]Non-Reaction Propulsion

Wheel and Track Systems

Wheel and track systems provide friction-based propulsion for land vehicles, converting mechanical power from an engine or motor into linear motion through torque applied to rotating wheels or continuous tracks. The core mechanism involves transmitting torque from the power source to the wheels or tracks via a drivetrain, which typically includes a gearbox for speed and torque multiplication, a differential to allow independent wheel rotation during turns, and axles that deliver the force to the ground-contacting elements. This torque generates rotational motion, and the resulting traction force propels the vehicle forward, limited by the friction between the contact surface and the ground. The traction force is given by , where is the coefficient of friction between the tire or track and the surface, and is the normal force exerted by the vehicle's weight on that surface.[33][34] Wheeled systems dominate most land transportation due to their simplicity and efficiency on prepared surfaces, featuring pneumatic tires that inflate with air to provide cushioning, reduce vibration, and enhance traction by conforming to the terrain. Examples include automobiles with four wheels and bicycles with two, where pneumatic tires—first practically applied to bicycles in 1888 by John Boyd Dunlop and to automobiles in 1895 by the Michelin brothers—improve ride comfort and grip compared to solid rubber alternatives.[35] In contrast, tracked systems use continuous belts of rigid plates driven by sprockets, distributing the vehicle's weight over a larger contact area to minimize ground pressure and enable operation on soft or uneven terrain, as seen in military tanks and construction bulldozers. This design reduces sinkage in soil or snow by lowering the pressure per unit area, often to levels below 0.1 MPa, compared to wheeled vehicles' higher point pressures.[36] Drive configurations further optimize propulsion by determining which wheels receive power. Rear-wheel drive (RWD) sends torque primarily to the rear wheels, offering balanced weight distribution for better handling in high-performance vehicles, while all-wheel drive (AWD) distributes torque to all four wheels, either constantly or on demand via clutches and electronics, improving traction on slippery surfaces without the need for driver intervention.[37] Power for these systems derives from internal combustion engines or electric motors. Internal combustion engines operate on the Otto cycle for spark-ignition gasoline engines, achieving thermal efficiencies up to 35% through controlled combustion in a four-stroke process, or the Diesel cycle for compression-ignition engines, reaching 40-45% efficiency due to higher compression ratios. Electric propulsion uses motors that convert electrical energy directly to torque with efficiencies exceeding 90%, often incorporating regenerative braking to recover kinetic energy during deceleration by reversing the motor to act as a generator, storing up to 70% of braking energy back into batteries. Overall drivetrain efficiency measures power transmission as , where is wheel torque, is angular velocity, and is input power, typically ranging from 80-95% in modern systems depending on losses in gears and friction.[38][39][40] Historically, wheel and track propulsion evolved from early steam-powered designs. In 1804, Richard Trevithick demonstrated the first successful steam railway locomotive at the Penydarren Ironworks in Wales, using high-pressure steam to drive pistons connected to wheels via rods, hauling iron over nine miles of track. Electric vehicles emerged in the 1830s with Robert Anderson's crude battery-powered carriage in Scotland, marking an early shift toward non-combustion propulsion. Modern advancements include hybrid systems like the Toyota Prius, introduced in 1997 as the first mass-produced hybrid electric vehicle, combining an internal combustion engine with electric motors for improved fuel efficiency through seamless power blending.[41][42][43]Magnetic and Cable Systems

Magnetic and cable systems represent non-friction-based propulsion methods for ground and elevated transport, primarily employed in specialized rail and aerial applications to achieve efficient movement over challenging terrains without reliance on wheel-rail contact. In magnetic levitation (maglev) systems, vehicles are suspended and propelled using electromagnetic forces, eliminating mechanical friction for reduced wear and higher speeds. Two primary levitation mechanisms are electromagnetic suspension (EMS) and electrodynamic suspension (EDS). EMS utilizes attractive forces generated by electromagnets on the vehicle interacting with a ferromagnetic guideway, maintaining a levitation gap of approximately 8-10 mm through active feedback control to counteract inherent instability.[44][45] In contrast, EDS employs repulsive forces from superconducting magnets on the vehicle inducing eddy currents in a conductive guideway, providing passive stability above a minimum speed threshold, typically around 80 km/h, with larger gaps up to 100 mm for smoother operation.[46][47] Superconducting materials in EDS systems enable persistent currents that sustain strong magnetic fields without continuous power input once cooled. Propulsion in maglev systems is achieved via linear motors, such as linear synchronous motors (LSM) or linear induction motors (LIM), integrated into the guideway. These motors generate thrust by creating a traveling magnetic wave that interacts with onboard magnets or conductors, accelerating the vehicle along the track.[48] The fundamental propulsion force arises from the Lorentz force acting on currents in the presence of the magnetic field, expressed as: where is the force, is the current, is the length of the conductor, and is the magnetic field strength.[49] This interaction provides precise, high-thrust propulsion scalable to speeds exceeding 500 km/h. Levitation gap stability is critical for safe operation, particularly in EMS where the attractive force decreases nonlinearly with increasing gap, leading to potential collapse without intervention. Stability analysis involves modeling the system as a feedback-controlled electromagnetic actuator, using techniques like state-space representations to ensure the gap remains within operational limits under disturbances such as track irregularities or load variations.[50] EDS systems offer inherent damping from eddy currents, enhancing passive stability at operational speeds, though startup assistance like wheels is required until levitation engages.[51] Development of maglev began in Japan in 1962 under the Japanese National Railways, with the first successful superconducting maglev run on a short test track in 1972.[52] In Germany, the Transrapid system, based on EMS technology, emerged in the late 1960s, with initial prototype testing in 1971 and full-scale development through the 1970s leading to operational demonstrations.[53] Cable propulsion systems, distinct from magnetic methods, use tensile forces from continuously moving or counterbalanced cables to drive vehicles, suitable for steep inclines or aerial routes. Aerial cable cars, or gondolas, consist of passenger cabins suspended from a haul rope driven by bullwheels at terminal stations, with grips that clamp onto the rope for propulsion.[54] Tension is maintained via counterweights or hydraulic tensioners to compensate for cable elongation under load, ensuring consistent speed and safety; detachable grips allow cabins to slow for boarding, while fixed grips operate at constant rope velocity up to 6 m/s.[55] Ground-based cable railways, such as funiculars, employ a cable connecting two counterbalanced cars over a summit pulley, where the descending car's weight assists in pulling the ascending one, minimizing energy input from stationary electric motors.[56] Grip mechanisms securely attach cars to the cable, with tension controlled by the pulley system and auxiliary drives for precise operation on gradients exceeding 30 degrees. A seminal example is the San Francisco cable car system, introduced in 1873 on Clay Street, which used underground cables gripped by levers to navigate steep urban hills, revolutionizing inclined transport.[57]Environmental Applications

Atmospheric Propulsion

Atmospheric propulsion encompasses systems designed for vehicles operating within Earth's atmosphere, where air density and aerodynamics play critical roles in efficiency and performance. For air vehicles, propellers remain a primary mechanism for subsonic flight, with fixed-pitch designs offering simplicity and lower cost for general aviation, while variable-pitch propellers allow optimization of blade angle for varying speeds and loads, enhancing efficiency in electric or hybrid configurations.[58] Jet engines, integrated into atmospheric vehicles for transonic and supersonic regimes as outlined in jet propulsion principles, provide high thrust but require careful aerodynamic matching to minimize drag penalties. The lift-to-drag (L/D) ratio fundamentally influences propulsion demands, as higher ratios enable sustained flight with less thrust, directly improving fuel efficiency and range in aircraft designs.[59] Environmental factors, including variations in air density with altitude, impose significant constraints on atmospheric propulsion systems. Air density decreases exponentially with height according to the barometric formula , where is sea-level density and is the scale height (approximately 8.5 km in the troposphere), leading to reduced power output and propeller thrust as altitude increases.[60] Additionally, international regulations, such as those from the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), have addressed noise and emissions since the 1970s; noise standards were first adopted in 1971 via Annex 16, with emissions standards for smoke and unburned hydrocarbons following in 1981 to mitigate local air quality impacts from aircraft engines.[61] Representative examples illustrate these adaptations. In drones, propeller efficiency leverages Bernoulli's principle, where accelerated airflow over blades creates pressure differentials for thrust generation, achieving up to 80-90% efficiency in small-scale rotors under standard conditions.[62] Hybrid electric aircraft concepts, such as NASA's planned X-57 Maxwell demonstrator (canceled in 2023 without flight), aimed to integrate distributed electric propulsion with high-lift propellers to enhance cruise efficiency by 500% over conventional designs, while addressing atmospheric density effects through advanced wing integration.[63]Marine Propulsion

Marine propulsion encompasses systems designed to generate thrust in water, leveraging hydrodynamic principles to propel vessels supported by buoyancy while navigating high-density fluid environments with significant drag forces. Early developments focused on mechanical innovations to overcome water resistance, beginning with paddle steamers introduced by Robert Fulton in 1807, when his vessel Clermont demonstrated the first commercially viable steamboat on the Hudson River, achieving speeds of about 5 knots and revolutionizing inland and coastal transport. By the 1910s, diesel engines emerged as a dominant power source, offering higher efficiency than steam; the Danish vessel MS Selandia became the first ocean-going ship powered solely by diesel in 1912, marking the shift toward internal combustion for commercial fleets.[64] Nuclear propulsion followed in 1954 with the USS Nautilus, the world's first nuclear-powered submarine, which enabled extended submerged operations without frequent surfacing for air, demonstrating unlimited range limited only by crew endurance.[65] Key mechanisms in marine propulsion include screw propellers, which dominate due to their efficiency in converting rotational energy into thrust via helical blades that accelerate water rearward; fixed-pitch and controllable-pitch variants are common, with designs optimized to minimize cavitation—the formation of vapor bubbles from low-pressure zones on blade surfaces that erodes material and reduces efficiency—through blade profiling and material choices like bronze alloys.[66] Waterjets provide an alternative, using impeller pumps to draw in and expel water at high velocity for thrust, ideal for shallow-draft vessels like ferries and patrol boats where protruding propellers risk damage, though they incur higher drag at low speeds.[67] Sails offer a reaction-based method, harnessing wind forces on fabric or rigid surfaces to generate lift and forward momentum, historically central to sailing ships and now revived in hybrid systems for fuel savings.[68] Power sources have evolved to enhance maneuverability and efficiency, with diesel remaining prevalent for its reliability across cargo and passenger ships, while electric pod systems like Azipods—azimuth thrusters housing electric motors and propellers in 360-degree rotatable pods—improve docking precision and reduce mechanical complexity by eliminating traditional shafts and rudders, cutting fuel use by up to 20% in applications such as cruise liners.[69] In modern liquefied natural gas (LNG) carriers, dual-fuel systems introduced in the 2010s allow engines to operate on LNG or marine diesel oil, reducing emissions by up to 25% and utilizing boil-off gas from cargo, as seen in vessels like those powered by MAN Energy Solutions' ME-GI engines.[70] Propeller performance is quantified by the thrust equation: where is thrust, is water density (typically 1025 kg/m³ for seawater), is rotational speed in revolutions per second, is propeller diameter, and is the thrust coefficient derived from empirical tests accounting for blade geometry and advance ratio.[71] Vessel motion balances this against hull resistance, approximated as: where is resistance force, is speed, is the drag coefficient (varying with hull form, often 0.001–0.01 for streamlined shapes), and is wetted surface area, emphasizing the need for hull designs that minimize wave-making and frictional components in dense water media.[72]Space Propulsion

Space propulsion encompasses the technologies and methods used to maneuver spacecraft in the vacuum of space, where the absence of atmosphere necessitates reliance on reaction principles to generate thrust for changing velocity, known as delta-v (Δv). These systems must account for orbital mechanics, propellant efficiency, and mission-specific requirements, such as achieving escape velocity from Earth or navigating interplanetary trajectories. Primary applications include launch vehicles for initial orbit insertion, attitude control systems to maintain orientation, and propulsion for deep-space travel, often combining onboard engines with gravitational influences from celestial bodies. Recent developments include reusable methane-fueled engines like SpaceX's Raptor, enabling high-thrust, recoverable launches with demonstrated orbital performance as of 2025.[73] Launch vehicles, typically multi-stage chemical rockets, provide the high thrust needed to overcome Earth's gravity and reach orbit, as exemplified by the Saturn V, which first flew in 1967 and powered the Apollo missions with liquid-fueled stages generating over 34 million newtons of thrust at liftoff.[74] For attitude control, spacecraft employ small thrusters, such as monopropellant hydrazine systems with specific impulse (Isp) values of 180–285 seconds, to make precise adjustments and stabilize orientation during coasting or thrusting phases.[75] Interplanetary missions integrate propulsion with gravity assists, where a spacecraft slingshots around a planet to gain or lose speed without expending propellant; NASA's Voyager 2 mission (1977) utilized assists from Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune to extend its reach across the solar system.[76] Advanced propulsion types balance thrust, efficiency (measured by Isp, in seconds), and mission demands. Chemical systems, using bipropellants like monomethyl hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide, deliver high thrust (up to 22 newtons) but low Isp (around 285–310 seconds), making them suitable for rapid maneuvers like orbit insertion.[4] Electric propulsion, particularly gridded ion thrusters using xenon gas ionized and accelerated electrostatically, achieves high Isp exceeding 3,000 seconds (e.g., 3,100 seconds for the NSTAR engine) at low thrust (0.1–20 millinewtons), enabling efficient station-keeping and interplanetary transfers over extended periods.[77] Nuclear thermal propulsion, demonstrated in the NERVA program through ground tests in the 1960s, heats hydrogen propellant via a nuclear reactor to produce Isp of 800–900 seconds with higher thrust than electric systems, offering potential for crewed Mars missions though never flown in space. Delta-v budgets for space maneuvers, such as Hohmann transfers between circular orbits, are calculated using the vis-viva equation for velocity, , where is the gravitational parameter, is the radial distance, and is the semi-major axis; the required is the difference between initial and transfer velocities, applied via the rocket equation to determine propellant needs.[80] Key milestones include the Saturn V's role in lunar landings and NASA's Deep Space 1 mission in 1998, which validated ion propulsion by operating for 16,265 hours and achieving 4.3 km/s of . Looking ahead, the VASIMR plasma engine, developed by Ad Astra Rocket Company, uses radiofrequency heating and magnetic fields to accelerate plasma propellants like argon, targeting Isp up to 5,000 seconds for rapid cislunar or Mars transits with nuclear electric power.[81][82]Biological Propulsion

Animal Mechanisms

Animal propulsion relies on diverse muscle-powered mechanisms adapted to terrestrial, aquatic, and aerial environments, enabling efficient locomotion through coordinated body movements. In leg-based systems, quadrupeds such as mammals generate forward thrust via alternating limb cycles, where ground reaction forces propel the body during stance phases while limbs swing freely in aerial phases. This mechanism optimizes energy use by minimizing vertical oscillations and maximizing horizontal impulse, as seen in the coordinated flexion and extension of limbs driven by antagonistic muscle pairs. In soft-bodied invertebrates like worms, peristalsis provides propulsion through sequential waves of circular and longitudinal muscle contractions, creating localized anchors via setae and propagating body undulations to push against substrates or burrow through media.[83][84][85] Aquatic animals employ fin and flipper-based undulatory swimming, where lateral body or appendage oscillations generate thrust by deforming water into reactive flows. Fish, for instance, use caudal fins in carangiform locomotion, with myotomal muscles contracting to produce a propagating wave that maximizes thrust while minimizing drag through tuned body stiffness. Flippers in marine mammals like dolphins facilitate similar undulations, achieving optimal propulsion at Strouhal numbers between 0.2 and 0.4, where tail oscillation frequency and amplitude balance thrust and efficiency. Aerial propulsion in birds and insects involves wing flapping, which creates lift and thrust via delayed stall and vortex shedding; the leading-edge vortex on flapping wings enhances force generation, with insects relying on rapid, high-frequency strokes to sustain hovering.[86][87][88] At the physiological core, propulsion stems from the sliding filament mechanism, where actin-myosin interactions in sarcomeres generate contractile force powered by ATP hydrolysis, converting chemical energy into mechanical work with cycle efficiencies up to 50% in fast-twitch fibers. This process fuels diverse locomotor patterns, though overall system efficiencies vary; fish achieve propulsive efficiencies approaching 90% during steady cruising due to streamlined hydrodynamics and red muscle specialization, contrasting with lower terrestrial efficiencies around 25-40% in legged animals owing to gravitational costs and intermittent contact.[89][83] Evolutionarily, animal propulsion traces from prokaryotic origins to complex vertebrate systems, beginning with bacterial flagella—rotary motors rotating at 100-300 Hz to propel cells via viscous drag—evolving into eukaryotic cilia and then metazoan appendages. Over 150 million years ago, transitional forms like Archaeopteryx integrated feathered wings for powered flight, bridging reptilian bipedalism with avian flapping via asymmetric feathers that stabilized vortices for lift. These adaptations reflect selective pressures for energy-efficient traversal of media, culminating in specialized mechanisms like the cheetah's sprint biomechanics, where peak ground reaction forces exceed three times body weight during acceleration, enabling bursts up to 100 km/h through elastic limb energy storage and rapid stride frequencies.[90][91][92]Human and Assisted Propulsion

Human propulsion encompasses natural forms of locomotion, such as bipedal walking and running on land, as well as swimming in aquatic environments. In bipedal movement, the heel-toe gait predominates, where the heel strikes the ground first, followed by a roll to the toes, enabling efficient forward progression through a combination of muscle contractions and passive elastic recoil in tendons and ligaments. The net metabolic energy cost for walking at preferred speeds is approximately 2 J/kg/m, reflecting the body's optimization for low-energy transport over long distances.[93] For running, this cost rises to about 3.5 J/kg/m, as greater vertical oscillation and faster stride frequencies demand higher muscular power to support body weight and generate propulsion.[94] Swimming relies on drag-based propulsion, where arms and legs execute alternating strokes to push against water resistance, creating thrust while minimizing frontal drag through streamlined body positioning. Arm pulls in strokes like front crawl generate the majority of propulsion via hand and forearm surfaces acting as paddles, supplemented by leg kicks that contribute up to 10-15% of total thrust in efficient swimmers. This mechanism contrasts with land-based gait by emphasizing hydrodynamic forces, with energy expenditure varying by stroke efficiency and speed, often exceeding 20 J/kg/m due to the dense medium.[95][96] Assisted propulsion augments human capabilities through mechanical devices, with the bicycle representing a seminal invention. In 1817, Karl Drais developed the first two-wheeled velocipede, or draisine, a wooden frame propelled by foot pushes against the ground, marking the transition from pure biological to hybrid locomotion. Modern bicycles employ a pedal-driven chain mechanism, where cranks connected to chainrings transfer leg power via a chain to rear sprockets, with gear ratios—calculated as front chainring teeth divided by rear cog teeth—allowing adaptation to terrain; for instance, a 50/25 ratio yields 2:1, doubling wheel rotations per pedal revolution for speed on flats.[97][98] Advanced augmentations include myoelectric prosthetics and powered exoskeletons, which interface with human physiology to restore or enhance mobility. Myoelectric lower-limb prosthetics use electromyographic signals from residual muscles to control actuators, such as motors at the knee and ankle, enabling propulsion mimicking natural gait patterns for amputees.[99] In the 2010s, DARPA-funded projects like the Warrior Web exosuit incorporated powered hip and knee joints to reduce metabolic demands during load-carrying, assisting soldiers by offloading up to 20 kg while preserving natural movement.[100] As of 2025, advancements include AI-powered exoskeletons for enhanced mobility, with innovations showcased at CES 2025 and a projected global market of $30 billion by 2032.[101][102][103] Electric bicycles, emerging commercially in the mid-1990s with hub motors integrated into wheels for pedal-assist, further exemplify augmentation by providing electric torque alongside human input, extending range without exceeding physiological limits.[104] Human propulsion is constrained by physiological limits, including aerobic capacity measured by VO2 max, which reaches 4-5 L/min in elite athletes, determining sustained endurance efforts. Peak power output, as in cycling, allows elites to maintain around 400 W for an hour, highlighting the interplay between muscular efficiency and cardiovascular support in augmented systems.[105][106]References

- https://science.[nasa](/page/NASA).gov/mission/deep-space-1/

- https://www1.grc.[nasa](/page/NASA).gov/wp-content/uploads/NERVA-Nuclear-Rocket-Program-1965.pdf