Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

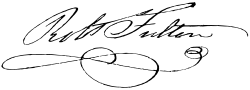

Robert Fulton

View on WikipediaRobert Fulton (November 14, 1765 – February 24, 1815) was an American engineer and inventor who is widely credited with developing the world's first commercially successful steamboat, the North River Steamboat (also known as Clermont). In 1807, that steamboat traveled on the Hudson River with passengers from New York City to Albany and back again, a round trip of 300 nautical miles (560 kilometers), in 62 hours. The success of his steamboat changed river traffic and trade on major American rivers.

Key Information

Fulton became interested in steam engines and the idea of steamboats in 1777 when he was around age 12 and visited state delegate William Henry of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, who was interested in this topic. Henry had learned about inventor James Watt and his Watt steam engine on an earlier visit to England.

In 1800, Fulton had been commissioned by Napoleon Bonaparte, leader of France, to attempt to design a submarine; he then produced Nautilus, the first practical submarine in history.[1] Fulton is also credited with inventing some of the world's earliest naval torpedoes for use by the Royal Navy.[2]

Early life

[edit]

Robert Fulton was born on a farm in Little Britain, Pennsylvania, on November 14, 1765. His father, Robert Fulton, married Mary Smith, daughter of Captain Joseph Smith and sister of Col. Lester Smith,[3] a comparatively well off family.[4] He had three sisters, Isabella, Elizabeth, and Mary, and a younger brother, Abraham.[5]

For six years, he lived in Philadelphia, where he painted portraits and landscapes, drew houses and machinery, and was able to send money home to help support his mother. In 1785, Fulton bought a farm at Hopewell Township in Washington County near Pittsburgh for £80 (equivalent to $13638 in 2018),[6] and moved his mother and family into it.

Career

[edit]Career in Europe (1786–1806)

[edit]

In early 1786, Fulton developed symptoms of tuberculosis and was advised by an eminent doctor to take an ocean voyage for the benefit of his health.[7] Fulton traveled to Europe, where he would live for the next twenty years. He left for England in the autumn of 1786, carrying several letters of introduction to Americans abroad from prominent individuals he had met in Philadelphia. He already corresponded with artist Benjamin West; their fathers had been close friends. West took Fulton into his home, where Fulton lived for several years and studied painting. Fulton gained many commissions painting portraits and landscapes, which allowed him to support himself. He continued to experiment with mechanical inventions.[5]

Fulton became caught up in the enthusiasm of the "Canal Mania". In 1793, he began developing his ideas for canals with inclined planes instead of locks. He obtained a patent for this idea in 1794, and also began working on ideas for the steam power of boats. He published a pamphlet about canals and patented a dredging machine and several other inventions. In 1794, he moved to Manchester to gain practical knowledge of English canal engineering. While there he became friendly with Robert Owen, a cotton manufacturer and early socialist. Owen agreed to finance the development and promotion of Fulton's designs for inclined planes and earth-digging machines; he was instrumental in introducing the American to a canal company, which awarded him a sub-contract. But Fulton was not successful at this practical effort and he gave up the contract after a short time.[8]

As early as 1793, Fulton proposed plans for steam-powered vessels to both the United States and British governments. The first steamships had appeared considerably earlier. The earliest steam-powered ship, in which the engine moved oars, was built by Claude de Jouffroy in France. Called Palmipède, it was tested on the Doubs in 1776. In 1783, de Jouffroy built Pyroscaphe, the first paddle steamer, which sailed successfully on the Saône. The first successful trial run of a steamboat in America had been made by inventor John Fitch, on the Delaware River on August 22, 1787. William Symington had successfully tried steamboats in 1788, and it seems probable that Fulton was aware of these developments.

In Britain, Fulton met the Duke of Bridgewater, Francis Egerton, whose canal, the first to be constructed in the country, was being used for trials of a steam tug. Fulton became very enthusiastic about the canals, and wrote a 1796 treatise on canal construction, suggesting improvements to locks and other features. Working for the Duke of Bridgewater between 1796 and 1799, Fulton had a boat constructed in the Duke's timber yard, under the supervision of Benjamin Powell. After installation of the machinery supplied by the engineers Bateman and Sherratt of Salford, the boat was duly christened Bonaparte in honour of Fulton having served under Napoleon. After expensive trials, because of the configuration of the design, the team feared the paddles might damage the clay lining of the canal and eventually abandoned the experiment. In 1801, Bridgewater instead ordered eight vessels for his canal based on Charlotte Dundas, constructed by Symington.

In 1797, Fulton went to Paris, where he was well known as an inventor. He studied French and German, along with mathematics and chemistry. Fulton also exhibited the first panorama painting to be shown in Paris, Pierre Prévost's Vue de Paris depuis les Tuileries (1800), on what is still called Rue des Panoramas (Panorama Street) today.[9] While living in France, Fulton designed the first working muscle-powered submarine, Nautilus, between 1793 and 1797. He also experimented with torpedoes. When tested, his submarine operated underwater for 17 minutes in 25 feet of water. He asked the government to subsidize its construction, but he was turned down twice. Eventually, he approached the Minister of Marine and, in 1800, was granted permission to build.[10] The shipyard Perrier in Rouen built it, and the submarine sailed first in July 1800 on the Seine River in the same city.

In France, Fulton met Robert R. Livingston, who was appointed U.S. Ambassador to France in 1801. He also had a scientifically curious mind, and the two men decided to collaborate on building a steamboat and to try operating it on the Seine. Fulton experimented with the water resistance of various hull shapes, made drawings and models, and had a steamboat constructed. At the first trial the boat ran perfectly, but the hull was later rebuilt and strengthened. On August 9, 1803, when this boat was driven up the River Seine, it sank. The boat was 66 feet (20 m) long, with an 8-foot (2.4 m) beam, and made between 2+1⁄2 and 3+1⁄2 knots (5 and 6 km/h) against the current.

In 1804, Fulton switched allegiance and moved to Britain, where he was commissioned by Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger to build a range of weapons for use by the Royal Navy during Napoleon's invasion scares. Among his inventions were the world's first modern naval "torpedoes" (modern "mines"). These were tested, along with several other of his inventions, during the 1804 Raid on Boulogne, but met with limited success. Although Fulton continued to develop his inventions with the British until 1806, the crushing naval victory by Admiral Horatio Nelson at the 1805 Battle of Trafalgar greatly reduced the risk of French invasion. Fulton was increasingly sidelined as a result.[2]

Career in the United States (1806–1815)

[edit]In 1806, Fulton returned to the United States. In 1807, he and Robert R. Livingston built the first commercially successful steamboat, North River Steamboat (later known as Clermont). Livingston's shipping company began using it to carry passengers between New York City and up the Hudson River to the state capital Albany. Clermont made the 150-nautical-mile (280 km) trip in 32 hours. Passengers on the maiden voyage included a lawyer Jones and his family from Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. His infant daughter Alexandra Jones later served as a Union nurse on a steamboat hospital in the American Civil War.[11]

The Clermont was the first successful steamboat in America. While it was being built people called it "Fulton's Folly". The Clermont had sails as well as a steam engine. At each end of the boat was a short mast with a small square sail that could be unfurled when needed. The engine was in the center of the boat and was surrounded by cord wood. The engine was 24-horsepower. Above the engine was a tall and slender smoke stack. On each side was a big paddle wheel that was open and uncovered. The diameter of the paddle wheels was 15 feet (4.6 m). The boat itself was 136 feet (41 m) long and 18 feet (5.5 m) wide. Its displacement was 160 tons.[12] Fulton received two patents for his steamboat, one in 1809 and the other in 1811.[13]

From 1811 until his death, Fulton was a member of the Erie Canal Commission, appointed by the Governor of New York.

Fulton's final design was the floating battery Demologos. This, the first steam-driven warship in the world, was built for the United States Navy for the War of 1812. The heavy vessel was not completed until after Fulton's death and was named in his honor.

From October 1811 to January 1812, Fulton, along with Livingston and Nicholas Roosevelt (1767–1854), worked together on a joint project to build a new steamboat, New Orleans, sturdy enough to take down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers to New Orleans, Louisiana. It traveled from industrial Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where it was built, with stops at Wheeling, West Virginia; Cincinnati, Ohio; past the "Falls of the Ohio" at Louisville, Kentucky; to near Cairo, Illinois, and the confluence with the Mississippi River; and down past Memphis, Tennessee, and Natchez, Mississippi, to New Orleans some 90 miles (140 km) by river from the Gulf of Mexico coast. This was less than a decade after the United States had acquired the Louisiana Territory from France. These rivers were not well settled, mapped, or protected. By achieving this first breakthrough voyage and also proving the ability of the steamboat to travel upstream against powerful river currents, Fulton changed the entire trade and transportation outlook for the American heartland.

Fulton was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1814.[14]

Personal life

[edit]

Prior to his marriage in 1808, Robert Fulton had a variety of homosexual and polyamorous relationships.[15] Famous among them was a ménage à trois with noted philanthropist couple Ruth and Joel Barlow while living in Paris with them for six years.[16] Letters between them reveal a sexual relationship among all three, including notes from American Revolutionary and patriot Joel Barlow requesting in baby-talk language for him "to have a wonderful summer of sexual pleasure with his wife" while he was away, and, importantly, that "he must not let...his beautiful body be deranged, and if he does anything wrong, he'll come and cut off his penis."[15] After he left Paris, he lived for two years at the castle of William Courtenay, 9th Earl of Devon, a known homosexual, although there is no confirmed epistolary evidence of an explicit sexual relationship between them[15][17]

On January 8, 1808, Fulton married Harriet Livingston (1783–1826), the daughter of Walter Livingston and niece of Robert R. Livingston, prominent men in the Hudson River area, whose family dated to the colonial era.[3][18] During his marriage, he proposed a foursome with himself, his wife, and Ruth and Joel Barlow in Washington, DC, but Harriet rejected the offer.[15] Harriet, who was nineteen years his junior, was well educated and was an accomplished amateur painter and musician.[4] Together, they had four children:[19]

- Robert Barlow Fulton (1808–1841), who died unmarried.[19]

- Julia Fulton (1810–1848), who married lawyer Charles Blight of Philadelphia.[19]

- Cornelia Livingston Fulton (1812–1893), who married lawyer Edward Charles Crary (1806–1848) in 1831.[18]

- Mary Livingston Fulton (1813–1861), who married Robert Morris Ludlow (1812–1894), parents of Robert Fulton Ludlow.[3]

Fulton died in 1815 in New York City from tuberculosis (then known as "consumption"). He had been walking home on the frozen Hudson River when one of his friends, Thomas Addis Emmet, fell through the ice. In rescuing his friend, Fulton got soaked with icy water. He is believed to have contracted pneumonia. When he got home, his sickness worsened. He was diagnosed with consumption and died at 49 years old. After his death, his widow married Charles Augustus Dale on November 26, 1816.

He is buried in the Trinity Church Cemetery for Trinity Church (Episcopal) at Wall Street in New York City, near other notable Americans such as former U.S. Secretaries of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton and Albert Gallatin. His descendants include Cory Lidle, a former Major League Baseball pitcher.[20]

Legacy

[edit]Posthumous honors

[edit]The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania donated a marble statue of Fulton to the National Statuary Hall Collection in the United States Capitol. Fulton was also honored for his development of steamship technology in New York City's Hudson-Fulton Celebration of the Centennial in 1909. A replica of his first steam-powered steam vessel, Clermont, was built for the occasion.

Five ships of the United States Navy have borne the name USS Fulton in honor of Robert Fulton.

Fulton Hall at the United States Merchant Marine Academy houses the Department of Marine Engineering and included laboratories for diesel and steam engineering, refrigeration, marine engineering, thermodynamics, materials testing, machine shop, mechanical engineering, welding, electrical machinery, control systems, electric circuits, engine room simulators and graphics.

Bronze statues of Fulton and Christopher Columbus represent commerce on the balustrade of the galleries of the Main Reading Room in the Thomas Jefferson Building of the Library of Congress on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C. They are two of 16 historical figures, each pair representing one of the 8 pillars of civilization.

The Guatemalan government in 1910 erected a bust of Fulton in one of the parks of Guatemala City.[21]

In 2006, Fulton was inducted into the "National Inventors Hall of Fame" in Alexandria, Virginia.[22]

Places named for Fulton

[edit]Many places in the U.S. are named for Robert Fulton, including:

Counties

[edit]Cities and towns

[edit]Other places

[edit]- Fulton Avenue, and the Fulton District in Sacramento, California

- Fulton Street in Berkeley, California

- Fulton Chain Lakes, New York

- Robert Fulton Elementary School, Chicago

- Robert Fulton Elementary, Cleveland, Ohio (closed)

- Fulton Elementary School, Dubuque, Iowa

- Robert Fulton Elementary School North Bergen, New Jersey

- Fulton Elementary School, Lancaster, Pennsylvania[24]

- Fulton Hall, State Quad, University at Albany, (State University of New York at Albany)

- Fulton Neighborhood in Minneapolis, Minnesota

- Fulton Opera House, Lancaster, Pennsylvania

- Fulton Park, New York City

- Fulton Steamboat Inn, hotel in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania

- Fulton Street in Brooklyn, New York

- BMT Fulton Street Line subway line

- IND Fulton Street Line subway line

- Fulton Street (IND Crosstown Line)

- Fulton Street in Manhattan

- Fulton Center in Manhattan

- Fulton Fish Market

- Fulton Street (New York City Subway) subway station

- Fulton Houses in Manhattan

- Fulton Street in Alcoa, Tennessee

- Fulton Street in Anaheim, California

- Fulton Street in Grand Rapids, Michigan

- Fulton Street in Hempstead, New York

- Fulton Street in Massapequa Park, New York

- Fulton Street in New Orleans, Louisiana

- Fulton Street in San Francisco, California

- Fulton Streer in Trenton, New Jersey[25]

- Fulton Street in York, Pennsylvania

- Fulton Street and Fulton Market in Chicago

- Fulton Street (Fultonstraße) in Vienna[26]

- Robert Fulton Drive in Columbia, Howard County, Maryland

- Robert Fulton Drive in Reston, Virginia

- Robert Fulton Fire Company, Fulton Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania

- Robert Fulton Highway, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania

- Robert Fulton School, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- Fulton, a neighborhood in Cincinnati, Ohio

In popular culture

[edit]20th Century-Fox's 1940 film, Little Old New York, based on a 1920 play by Rida Johnson Young, is a fictionalized version of Fulton's life from his arrival in New York to the first sailing of Clermont. British actor Richard Greene starred as Fulton with Brenda Joyce as Harriet Livingston. Alice Faye and Fred MacMurray played wharf friends who help Fulton overcome problems to realize his dream.

A fictionalized account of Fulton's role was produced by BBC television during the 1960s. In the first serial, Triton (1961,[27] re-made in 1968), two British naval officers, Captain Belwether and Lieutenant Lamb, are involved in spying on Fulton while he is working for the French. In the sequel, Pegasus (1969), they are surprised to find themselves working with Fulton after he changed sides. In the 1961 series, Fulton was played by Reed De Rouen, in the 1968 and 1969 series he was played by Robert Cawdron.

A Robert Fulton cartoon character appears in the 1955 Casper the Friendly Ghost short film Red, White, and Boo.

Author James McGee used Fulton's experiments in early submarine warfare (against wooden warships) as a major plot element in his 2006 novel Ratcatcher.

Invasion (2009), the tenth novel in the "Kydd" naval warfare series by Julian Stockwin, uses Fulton and his submarine as an important plot element.[28]

Until 2016, Disney Springs at Walt Disney World had a restaurant named Fulton's Crab House with a building in the shape of a steamboat.[29][30]

Gallery

[edit]-

Fulton presents his steamship to Bonaparte in 1803

-

Submarine design in cross section by Robert Fulton, 1806

-

Robert Fulton's tombstone at Trinity Church (Episcopal) in New York City

-

Fulton sculpture by Caspar Buberl at the Brooklyn Museum, 1872

-

Hudson-Fulton Celebration commemorative stamp, 1909 issue

-

200th Anniversary commemorative stamp, 1965 issue, based on the Houdon bust

Publications

[edit]- Torpedo war, and submarine explosions published 1810.

- A Treatise on the Improvement of Canal Navigation Archived 2004-12-31 at the Wayback Machine, 1796. From the University of Georgia Libraries in DjVu & layered PDF Archived 2006-08-24 at the Wayback Machine formats.

- A Treatise on the Improvement of Canal Navigation Archived 2023-05-31 at the Wayback Machine 1796. From Rare Book Room.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ American Treasures of the Library of Congress: "Fulton's Submarine" Archived 2009-03-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Best, Nicholas (2005). Trafalgar: The Untold Story of the Greatest Sea Battle in History. London: Phoenix. ISBN 0-7538-2095-1.

- ^ a b c Reynolds, Cuyler (1911). Hudson-Mohawk Genealogical and Family Memoirs: A Record of Achievements of the People of the Hudson and Mohawk Valleys in New York State, Included Within the Present Counties of Albany, Rensselaer, Washington, Saratoga, Montgomery, Fulton, Schenectady, Columbia and Greene. Lewis Historical Publishing Company. pp. 302–303.

- ^ a b Philip, Cynthia Owen (2003). Robert Fulton: A Biography. iUniverse. p. 3. ISBN 9780595262038. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ a b Buckman, David Lear (1907). Old Steamboat Days on The Hudson River. The Grafton Press. Archived from the original on August 26, 2010.

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved May 7, 2024.

- ^ Sutcliffe, Alice (1925). Robert Fulton. New York: The Macmillan Company.

- ^ Boyes, Graham. The Peak Forest Canal. ISBN 978-0901461599.

- ^ Sutcliffe, 1909, p. 63.

- ^ Burgess, Robert Forrest (1975). Ships Beneath the Sea. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-008958-7.

- ^ Alice Crary Sutcliffe, Robert Fulton and the 'Claremont'

- ^ Baldwin, James, Sailing the Seas, American Book Company, New York, Copyright 1920, pp. 73–74,

- ^ "Robert Fulton and the Claremont". Patently Interesting. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- ^ "MemberListF". American Antiquarian Society. Archived from the original on 2015-04-18. Retrieved 2015-04-14.

- ^ a b c d "[The Fire of His Genius] | Video | C-SPAN.org".

- ^ "Postscripts: The Short, Tragic Life of Robert Fulton, 2: Gone Too Soon".

- ^ Griffin, Gabriele (2004-06-16). Who's Who in Lesbian and Gay Writing. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-203-40221-4.

- ^ a b Historical Papers and Addresses of the Lancaster County Historical Society. 1909. pp. 227–228.

- ^ a b c Historical Papers and Addresses of the Lancaster County Historical Society: January 8, 1909. Vol. XIII No. 1. Lancaster County Historical Society. 1909. p. 227. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ "Lidle dies after plane crashes into NYC high-rise". ESPN.com. 11 October 2006.

- ^ "Fleet of Fifty Warships Built in the Brooklyn Navy Yard". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Brooklyn, New York). 12 May 1910. p. 22. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ "National Inventors Hall of Fame". Archived from the original on April 8, 2013.

- ^ Eaton, David Wolfe (1916). How Missouri Counties, Towns and Streams Were Named. The State Historical Society of Missouri. p. 267.

- ^ "The School District of Lancaster". Archived from the original on 2009-02-01. Retrieved 2008-06-10.

- ^ "Trenton Historical Society, New Jersey".

- ^ "Fultonstraße".

- ^ "Triton: Part 2". BBC Genome. 13 April 1962. Archived from the original on December 9, 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ^ Stockwin, Julian (2009). Invasion. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 9780340961155.

- ^ Arnold, Kyle. "Fulton's Crab House at Disney Springs changing to Paddlefish". OrlandoSentinel.com. Retrieved 2018-01-31.

- ^ Delgado, Lauren. "First Look: Paddlefish in Disney Springs". OrlandoSentinel.com. Retrieved 2018-01-31.

Sources

[edit]- Old Steamboat Days on The Hudson River (1909)

- Sutcliffe, Alice Crary (1909). Robert Fulton and the "Clermont". New York : The Century Co.

External links

[edit]- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Robert Fulton Birthplace

- Photos of Fulton's Birthplace

- Phair, Montgomery. "Robert Fulton and the Secret War of 1812". Casebook: The War of 1812. Archived from the original on October 2, 2006.

- Chapter XIII: Robert Fulton in Great Fortunes, and How They Were Made (1871), by James D. McCabe Jr., Illustrated by G. F. and E. B. Bensell, a Project Gutenberg eBook.

- Harvey, W.S.; Downs-Rose, G. (1980). "William Symington". Archived from the original on February 16, 2002.

- Buckman, David Lear (1907). Old Steamboat Days on The Hudson River. The Grafton Press. Archived from the original on August 26, 2010.

- Examples of art by Robert Fulton at the Art Renewal Center

- Thurston, Robert H. "Chapter V: The Modern Steam Engine". A history of the growth of the steam-engine. Archived from the original on 2012-02-21. Archived from the original.

- Iles, George (1912), Leading American Inventors, New York: Henry Holt and Company, pp. 40–75

- Booknotes interview with Kirkpatrick Sale on The Fire of His Genius: Robert Fulton and the American Dream, November 25, 2001.

- Collection of Robert Fulton manuscripts Archived 2016-01-01 at the Wayback Machine – digital facsimile from the Linda Hall Library

Robert Fulton

View on GrokipediaRobert Fulton (1765–1815) was an American engineer and inventor best known for developing and operating the first commercially successful steamboat.[1] Born in Little Britain, Pennsylvania, Fulton initially pursued painting in England and France before turning to engineering, where he designed improvements for canals and early submarines.[2] In 1807, partnering with Robert Livingston, he launched the North River Steamboat (later dubbed Clermont) on the Hudson River, completing a voyage from New York to Albany in 24 hours and demonstrating reliable steam-powered navigation that transformed commerce and travel.[1] Earlier, in 1800, Fulton constructed the hand-cranked submarine Nautilus in France under Napoleon Bonaparte's patronage, capable of submerging for limited durations and intended for naval warfare, though it saw no combat use.[3] His innovations extended to torpedo-like explosive devices and steam warship concepts during the War of 1812, underscoring his focus on practical applications of steam power and underwater propulsion despite challenges in securing military adoption.[4]