Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Psalm 1

View on Wikipedia

| Psalm 1 | |

|---|---|

| "Blessed is the man" | |

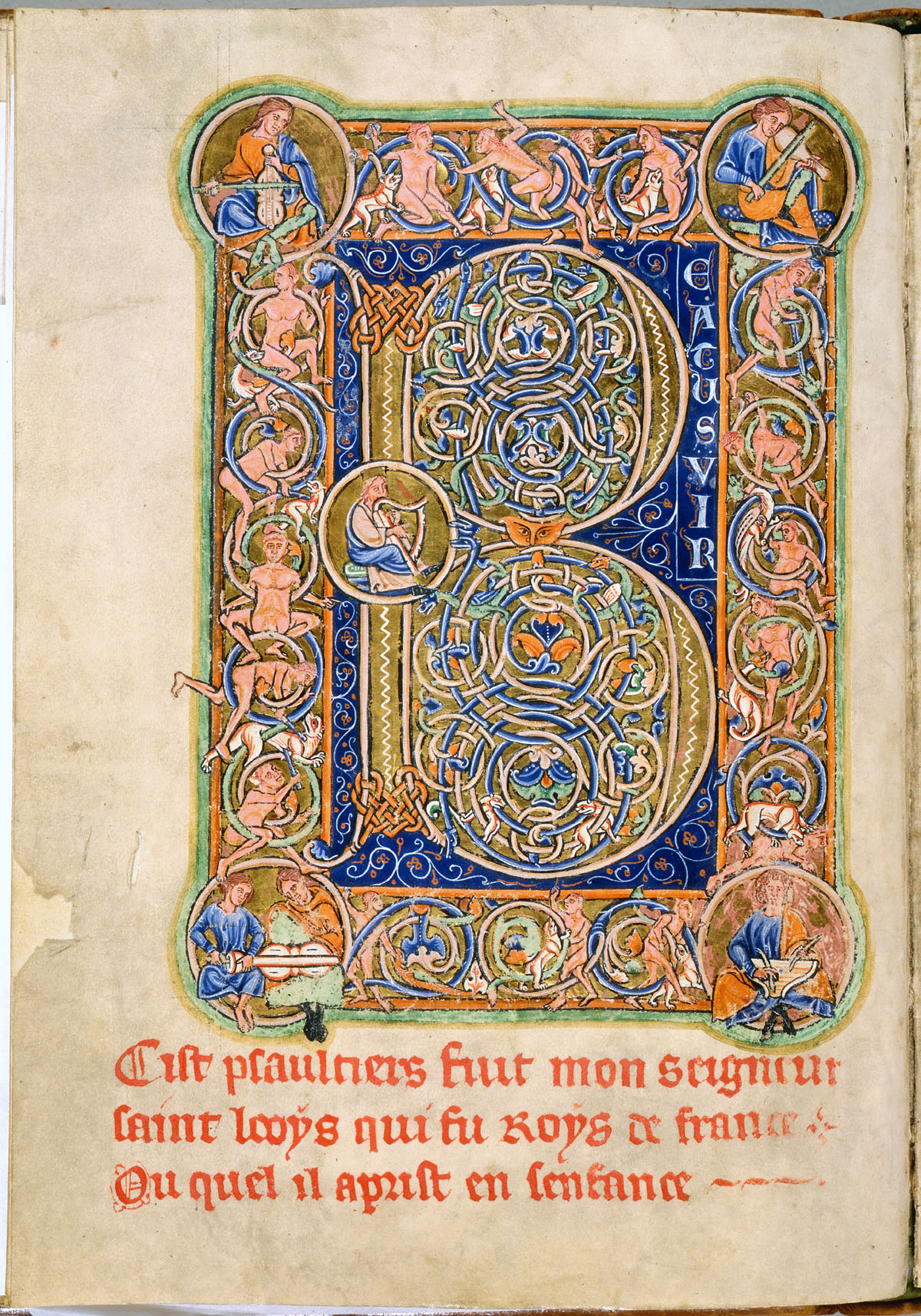

Large Beatus initial from the Leiden Psalter of Saint Louis, 1190s | |

| Other name |

|

| Language | Hebrew (original) |

| Psalm 1 | |

|---|---|

Psalm 2 → | |

| Book | Book of Psalms |

| Hebrew Bible part | Ketuvim |

| Order in the Hebrew part | 1 |

| Category | Sifrei Emet |

| Christian Bible part | Old Testament |

| Order in the Christian part | 19 |

Psalm 1 is the first psalm of the Book of Psalms, beginning in the English King James Version: "Blessed is the man", and forming "an appropriate prologue" to the whole collection according to Alexander Kirkpatrick.[1] The Book of Psalms is part of the third section of the Hebrew Bible,[2] and a book of the Christian Old Testament. In Latin, this psalm is known as "Beatus vir" [3] or "Beatus vir, qui non abiit".[4]

The psalm is a regular part of Jewish, Catholic, Lutheran and Anglican liturgies in addition to Protestant psalmody.

Numbering

[edit]The Book of Psalms is subdivided into five parts. Psalm 1 is found in the first part, which includes psalms 1 through 41.[5] It has been counted as the beginning of part one in some translations, in some counted as a prologue, and in others Psalm 1 is combined with Psalm 2.[6]

Background and themes

[edit]Beatus vir, "Blessed is the man ..." in Latin, are the first words in the Vulgate Bible of both Psalm 1 and Psalm 112 (111). In illuminated manuscript psalters, the start of the main psalm text was traditionally marked by a large Beatus initial for the "B" of "Beatus", and the two opening words are often much larger than the rest of the text. Between them, these often take up a whole page. Beatus initials have been significant in the development of manuscript painting, as the location of several developments in the use of initials as the focus of painting.[7]

Patrick D. Miller suggests that Psalm 1 "sets the agenda for the Psalter through its "identification of the way of the righteous and the way of the wicked as well as their respective fates" along with "its emphasis on the Torah, the joy of studying it and its positive benefits for those who do".[8] Stephen Dempster suggests that the psalm serves as an introduction to the Ketuvim (Writings), the third section of the Tanakh. Dempster points out the similarities between Psalm 1:2–3 and Joshua 1:8, the first chapter of the Nevi'im (Prophets),[9] in both passages—the one who meditates on the Law (Biblical Hebrew: סֵפֶר הַתּוֹרָה, romanized: Sefer HaTorah) prospers: {{blockquote|text=This Book of the Law shall not depart from your mouth, but you shall meditate in it day and night, that you may observe to do according to all that is written in it. For then you will make your way prosperous, and then you will have good success.[10]

Like many of the psalms, it contrasts the "righteous" person (tzadik צדיק) with the "wicked" or "ungodly" (rasha` רשע) or the "sinner" (chatta' חטא). A righteous person carefully learns the laws of God, which gives them good judgment and helps them avoid bad company. As a result, they can endure tough times supported by God's grace and protection.[11] On the other hand, the wicked person's behavior makes them vulnerable to disaster, like chaff blowing away in the wind. The point that the wicked and the righteous will not mingle at the day of judgment is clearly stated by the writer. The path the wicked have chosen leads to destruction, and at the judgment, they receive the natural consequences of that choice.[12]

The righteous person is compared in verse 3 to a tree planted beside a stream. Their harvest is plentiful, and whatever they do prospers. The prophet Jeremiah is recorded sharing a similar message in Jeremiah 17:7–8—namely of the advantage in facing difficult times if one trusts in God:

Blessed is the man who trusts in the LORD, whose trust is in God alone. He shall be like a tree planted by waters, sending forth its roots by a stream: It does not sense the coming of heat, its leaves are ever fresh; of has no care in a year of drought, it does not cease to yield fruit.[13]

Bible scholar Alexander Kirkpatrick suggests that the "judgment" referred to in verse 5 pertains not only to the "last judgment"—"as the Targum and many interpreters understand it"—but also to every act of divine judgment.[1]

In The Flow of the Psalms, Christian O. Palmer Robertson examines thematic pairings of divine law and the Messiah, notably emphasizing the law in Psalm 1 alongside the anointed (i.e., the Messiah) in Psalm 2. Similar intentional pairings are observed with Psalms 18 and 19, as well as Psalms 118 and 119 .[14]

Text

[edit]The following table shows the Hebrew text[15][16] of the Psalm with vowels, alongside the Koine Greek text in the Septuagint,[17] the Latin text in the Vulgate[18] and the English translation from the King James Version. Note that the meaning can slightly differ between these versions, as the Septuagint and the Masoretic Text come from different textual traditions.[note 1]

| # | Hebrew | English | Greek | Latin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | אַ֥שְֽׁרֵי הָאִ֗ישׁ אֲשֶׁ֤ר ׀ לֹ֥א הָלַךְ֮ בַּעֲצַ֢ת רְשָׁ֫עִ֥ים וּבְדֶ֣רֶךְ חַ֭טָּאִים לֹ֥א עָמָ֑ד וּבְמוֹשַׁ֥ב לֵ֝צִ֗ים לֹ֣א יָשָֽׁב׃ | Blessed is the man that walketh not in the counsel of the ungodly, nor standeth in the way of sinners, nor sitteth in the seat of the scornful. | ΜΑΚΑΡΙΟΣ ἀνήρ, ὃς οὐκ ἐπορεύθη ἐν βουλῇ ἀσεβῶν καὶ ἐν ὁδῷ ἁμαρτωλῶν οὐκ ἔστη καὶ ἐπὶ καθέδρᾳ λοιμῶν οὐκ ἐκάθισεν. | Beatus vir, qui non abiit in consilio impiorum et in via peccatorum non stetit et in conventu derisorum non sedit, |

| 2 | כִּ֤י אִ֥ם בְּתוֹרַ֥ת יְהֹוָ֗ה חֶ֫פְצ֥וֹ וּֽבְתוֹרָת֥וֹ יֶהְגֶּ֗ה יוֹמָ֥ם וָלָֽיְלָה׃ | But his delight is in the law of the LORD; and in his law doth he meditate day and night. | ἀλλ᾿ ἤ ἐν τῷ νόμῳ Κυρίου τὸ θέλημα αὐτοῦ, καὶ ἐν τῷ νόμῳ αὐτοῦ μελετήσει ἡμέρας καὶ νυκτός. | sed in lege Domini voluntas eius, et in lege eius meditatur die ac nocte. |

| 3 | וְֽהָיָ֗ה כְּעֵץ֮ שָׁת֢וּל עַֽל־פַּלְגֵ֫י־מָ֥יִם אֲשֶׁ֤ר פִּרְי֨וֹ ׀ יִתֵּ֬ן בְּעִתּ֗וֹ וְעָלֵ֥הוּ לֹֽא־יִבּ֑וֹל וְכֹ֖ל אֲשֶׁר־יַעֲשֶׂ֣ה יַצְלִֽיחַ׃ | And he shall be like a tree planted by the rivers of water, that bringeth forth his fruit in his season; his leaf also shall not wither; and whatsoever he doeth shall prosper. | καὶ ἔσται ὡς τὸ ξύλον τὸ πεφυτευμένον παρὰ τὰς διεξόδους τῶν ὑδάτων, ὃ τὸν καρπὸν αὐτοῦ δώσει ἐν καιρῷ αὐτοῦ, καὶ τὸ φύλλον αὐτοῦ οὐκ ἀποῤῥυήσεται· καὶ πάντα, ὅσα ἂν ποιῇ, κατευοδωθήσεται. | Et erit tamquam lignum plantatum secus decursus aquarum, quod fructum suum dabit in tempore suo; et folium eius non defluet, et omnia, quaecumque faciet, prosperabuntur. |

| 4 | לֹא־כֵ֥ן הָרְשָׁעִ֑ים כִּ֥י אִם־כַּ֝מֹּ֗ץ אֲֽשֶׁר־תִּדְּפֶ֥נּוּ רֽוּחַ׃ | The ungodly are not so: but are like the chaff which the wind driveth away. | οὐχ οὕτως οἱ ἀσεβεῖς, οὐχ οὕτως, ἀλλ᾿ ἢ ὡσεὶ χνοῦς, ὃν ἐκρίπτει ὁ ἄνεμος ἀπὸ προσώπου τῆς γῆς. | Non sic impii, non sic, sed tamquam pulvis, quem proicit ventus. |

| 5 | עַל־כֵּ֤ן ׀ לֹא־יָקֻ֣מוּ רְ֭שָׁעִים בַּמִּשְׁפָּ֑ט וְ֝חַטָּאִ֗ים בַּעֲדַ֥ת צַדִּיקִֽים׃ | Therefore, the ungodly shall not stand in the judgment, nor sinners in the congregation of the righteous. | διὰ τοῦτο οὐκ ἀναστήσονται ἀσεβεῖς ἐν κρίσει, οὐδὲ ἁμαρτωλοὶ ἐν βουλῇ δικαίων· | Ideo non consurgent impii in iudicio, neque peccatores in concilio iustorum. |

| 6 | כִּֽי־יוֹדֵ֣עַ יְ֭הֹוָה דֶּ֣רֶךְ צַדִּיקִ֑ים וְדֶ֖רֶךְ רְשָׁעִ֣ים תֹּאבֵֽד׃ | For the LORD knoweth the way of the righteous: but the way of the ungodly shall perish. | ὅτι γινώσκει Κύριος ὁδὸν δικαίων, καὶ ὁδὸς ἀσεβῶν ἀπολεῖται. | Quoniam novit Dominus viam iustorum, et iter impiorum peribit. |

Uses

[edit]Judaism

[edit]Psalms 1, 2, 3, and 4 are recited on Yom Kippur night after Maariv.[19]

Verse 1 is quoted in the Mishnah in Pirkei Avot 3:2,[20] wherein Rabbi Haninah ben Teradion explains that a group of people that does not exchange words of Torah is an example of the psalm's "company of scoffers".[21] Psalm 1 is also recited to prevent a miscarriage.[22]

In the Talmud (Berakhot 10a),[23] it is stated that Psalm 1 and Psalm 2 were counted as one composition and David's favorite as he used the word "ashrei" ("blessed") in the opening phrase of Psalm 1 (ashrei ha′ish) and the closing phrase of Psalm 2 (ashrei kol choso vo).[24]

Christianity

[edit]

In the Church of England's Book of Common Prayer, Psalm 1 is appointed to be read on the morning of the first day of the month.[4] English poet John Milton translated Psalm 1 into English verse in 1653. Scottish poet Robert Burns wrote a paraphrase of the psalm, referring to "the man, in life wherever plac'd, ... who walks not in the wicked's way, nor learns their guilty lore!"[25] The Presbyterian Scottish Psalter of 1650 rewords the psalm in a metrical form that can be sung to a tune set to the common meter.[26]

Some[weasel words] see the Law and the work of the Messiah set side by side in Psalms 1 and 2, 18 and 19, 118 and 119. They see the law and the Messiah opening the book of Psalms.[27][28]

Book 1 of the Psalms begins and ends with "the blessed man": the opening in Psalms 1–2[29] and the closing of Psalms 40–41.[30] Theologian Hans Boersma notes that "beautifully structured, the first book concludes just as it started".[31] Many see the 'blessed man being Jesus'.[32]

In the Agpeya, the Coptic Church's book of hours, this psalm is prayed in the office of Prime.[33]

Musical settings

[edit]Thomas Tallis included Psalm 1, with the title Man blest no dout, in his nine tunes for Archbishop Parker's Psalter (1567).[34]

Dwight L. Armstrong composed “Blest and Happy Is the Man” which appears in hymnals of the Worldwide Church of God.

Heinrich Schütz wrote a setting of a paraphrase in German, "Wer nicht sitzt im Gottlosen Rat", SWV 079, for the Becker Psalter, published first in 1628. Marc-Antoine Charpentier composed around 1670, one "Beatus vir qui non abiit", H.175, for 3 voices, 2 treble instruments and continuo.

Music artist Kim Hill recorded a contemporary setting of Psalm 1.[citation needed]

The Psalms Project released its musical composition of Psalm 1 on the first volume of its album series in 2012.[35]

In 2018 Jason Silver, a Christian musician and composer, released Psalm 1 set in a contemporary musical setting. This was on Volume 1 of his Love the Psalms project.[36] He entitled it "The Two Ways".[37]

Notes

[edit]- ^ A 1917 translation directly from Hebrew to English by the Jewish Publication Society can be found here or here, and an 1844 translation directly from the Septuagint by L. C. L. Brenton can be found here. Both translations are in the public domain.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Kirkpatrick, A. F. (1906), Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges on Psalm 1, accessed 11 September 2021

- ^ Mazor 2011, p. 589.

- ^ Parallel Latin/English Psalter / Psalmus 1 Archived 11 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine medievalist.net

- ^ a b Church of England, Book of Common Prayer: The Psalter as printed by John Baskerville in 1762

- ^ Richard J. Clifford (2010). Michael D. Coogan (ed.). The New Oxford Annotated Bible: New Revised Standard Version, With The Apocrypha: Fully Revised Fourth Edition: College Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 773.

- ^ Dummelow, J. R. The One Volume Bible Commentary. 1936. Macmillan Company. P. 328-329.

- ^ Otto Pächt, Book Illumination in the Middle Ages (trans fr German), pp. 85–90, 1986, Harvey Miller Publishers, London, ISBN 0199210608

- ^ Miller, Patrick D (2009). "The Beginning of the Psalter". In McCann, J. Clinton (ed.). Shape and Shaping of the Psalter. pp. 85–86.

- ^ Joshua 1:8

- ^ Stephen G. Dempster, "The Prophets, the Canon and a Canonical Approach" in Craig Bartholomew et al (eds.), Canon and Biblical Interpretation, p. 294.

- ^ Jeremiah 17:7–9; Commentary on Jeremiah 17:8, Earle, Ralph, Adam Clarke’s Commentary on the Holy Bible, Beacon Hill Press 1967, p. 627

- ^ Commentary on Psalm 1:6; Matthew Henry's Commentary on the Whole Bible, Vol. III, 1706–1721, p. 390 read online

- ^ Jer 17:7–8

- ^ Robertson, O. Palmer. "The Flow of the Psalms," pp. 247, 249. In The Flow of the Psalms, P&R Publishing, 2015, ISBN 978-1-62995-133-1 pp. 247, 249

- ^ "Psalms – Chapter 1". Mechon Mamre.

- ^ "Psalms 1 - JPS 1917". Sefaria.org.

- ^ "Psalm 1 - Septuagint and Brenton's Septuagint Translation". Ellopos. Retrieved 3 March 2025.

- ^ "NOVA VULGATA LIBER PSALMORUM". Vatican City. Retrieved 2 June 2025.

- ^ Brauner, Reuven (2013). "Shimush Pesukim: Comprehensive Index to Liturgical and Ceremonial Uses of Biblical Verses and Passages" (PDF) (2nd ed.). p. 31.

- ^ Talmud, b. Pirkei Avot 3:2

- ^ Scherman 2003, p. 557.

- ^ "Birth". Daily Tehillim. Archived from the original on 14 December 2018. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ Talmud, b. Berakhot 10a

- ^ Parsons, John J. Psalm 1 in Hebrew (Mizmor Aleph) with English commentary. Hebrew4christians. Accessed July 30, 2020.

- ^ Psalm 1 – A Paraphrase by Robert Burns Archived 16 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 2 August 2016

- ^ "Psalm 1, Scottish Psalter".

- ^ "The Messianic Nature of Psalm 118".

- ^ Jamie A. Grant, The King as Exemplar: The Function of Deuteronomy’s Kingship Law in the Shaping of the Book of Psalms (AcBib 17; Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2004)

- ^ 1:1; 2:12

- ^ 40:4; 41:1

- ^ Boersma, H., Sacramental Preaching: Sermons on the Hidden Presence of Christ, chapter 9

- ^ Samson, John. The Blessed Man of Psalm One. Reformation Theology. February 16, 2008.

- ^ "Prime". agpeya.org. Retrieved 3 March 2025.

- ^ Tallis First Tune, Choral Public Domain Library, accessed 11 September 2021

- ^ "Music". The Psalms Project. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ "Jason Silver - Worship Songs". Be Still - Scripture Songs by Jason Silver. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ "Jason Silver - Worship Songs". Be Still - Scripture Songs by Jason Silver. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

Cited sources

[edit]- Mazor, Lea (2011). "Book of Psalms". In Berlin, Adele; Grossman, Maxine (eds.). The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973004-9.

- Scherman, Rabbi Nosson (2003). The Complete Artscroll Siddur (3rd ed.). Mesorah Publications, Ltd. ISBN 978-0-89-906650-9.

Further reading

[edit]- Berlin, Adele and Brettler, Marc Zvi, The Jewish Study Bible, Oxford University Press, Oxford, New York p. 1284-1285.

- Saint Augustine of Hippo. "Expositions on the Book of Psalms". CCEL. Archived from the original on 2 September 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2021. (also known under the title of Homelies on Psalms)

External links

[edit]- Pieces with text from Psalm 1: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Psalm 1: Free scores at the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Psalms Chapter 1 תְּהִלִּים text in Hebrew and English, mechon-mamre.org

- Text of Psalm 1 according to the 1928 Psalter Archived 4 December 2024 at the Wayback Machine

- Psalm 1 – The Way of the Righteous and the Way of the Ungodly text and detailed commentary, enduringword.com

- Blessed is the man who does not walk in the counsel of the wicked text and footnotes, usccb.org United States Conference of Catholic Bishops

- PSAL. I. / Bless'd is the man who hath not walk'd astray Archived 31 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine translation by John Milton, dartmouth.edu

- Psalm 1:1 introduction and text, biblestudytools.com

- Psalm 1 / Refrain: The Lord knows the way of the righteous. Church of England

- Psalm 1 at biblegateway.com

- Calvin's Commentaries, Vol. 10: Psalms, Part I, tr. by John King, (1847–50) / PSALM 1. sacred-texts.com

- Charles H. Spurgeon: Psalm 1 detailed commentary, archive.spurgeon.org

- Psalm 1 in Hebrew and English with commentary on specific Hebrew words.

- The happy man of Psalm 1, from the Jewish Bible Quarterly

- "Hymns for Psalm 1". hymnary.org. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- PSALMUS 01, Vatican City

Psalm 1

View on GrokipediaIntroduction and Context

Numbering and Placement

Psalm 1 is positioned as the first psalm in the Book of Psalms, a compilation of 150 individual psalms that collectively form the Psalter.[6] It functions as a prologue to the entire book, introducing themes of righteous meditation on divine instruction that frame the subsequent collection.[7] The Book of Psalms itself is structured into five distinct books, with Psalm 1 opening Book 1, which spans Psalms 1–41 and concludes with a doxology in Psalm 41:13.[8] In the Hebrew Bible, the Book of Psalms holds the position of the first book within the Ketuvim, the third and final division known as the Writings.[9] In the Christian Old Testament, it appears among the poetic or wisdom books, typically following the historical books such as Chronicles and preceding Proverbs.[6] Unlike many psalms, Psalm 1 lacks a superscription, rendering its authorship anonymous within the text.[10] The compilation of the Book of Psalms occurred during the post-exilic period, approximately between the 5th and 2nd centuries BCE, drawing from earlier materials into its canonical form.[11] Variations in its treatment appear in ancient sources; for instance, some early Hebrew manuscripts combine Psalms 1 and 2 into a single composition, while others regard Psalm 1 as an unnumbered introductory piece to the Psalter.[12] In the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures, Psalm 1 retains its distinct numbering and placement as the opening psalm, consistent with the Masoretic Text tradition.[13]Historical Background

Psalm 1 is widely regarded by biblical scholars as an anonymous composition, lacking the superscription typical of many Davidic psalms in the Psalter, which suggests it was likely penned by a scribe, temple poet, or editor rather than a named historical figure.[14] Its placement as the opening psalm indicates an intentional editorial addition to frame the entire collection, possibly crafted specifically for this introductory role during the Psalter's final compilation.[14] The psalm's origins are traced to the post-exilic period, likely during or after the Babylonian exile in the 6th century BCE, aligning with the broader compilation of the Book of Psalms between the 5th and 2nd centuries BCE in the early Second Temple era.[15] This timing reflects Israel's experiences of displacement and return, where meditation on the Torah became a central practice amid the loss of temple rituals, as evidenced by connections to Ezra's post-exilic reforms emphasizing law observance.[16] No major archaeological discoveries related to Psalm 1 have emerged since 2020, leaving scholarly dating reliant on textual and literary analysis.[15] Influences from ancient Near Eastern wisdom traditions are evident, with thematic parallels to books like Proverbs and Job, particularly in the contrast between the righteous and the wicked and imagery of prosperity through divine instruction.[17] Intertextual links further tie it to prophetic and Deuteronomic texts, such as Joshua 1:8's call to meditate on the law day and night for success, and Deuteronomy's emphasis on covenantal adherence to the Torah as a path to blessing.[14] These connections underscore Psalm 1's role in promoting Torah-centered piety as a response to exilic trauma. In recent scholarship, commentaries from the 2020s, such as those in Working Preacher analyses, highlight the psalm's emphasis on "meditative delight" in the Torah—portrayed not as rote legalism but as joyful, active engagement that fosters covenantal faithfulness and serves as an entry point to the Psalter's themes of divine guidance.[18] This perspective reinforces its function in post-exilic Judaism as a wisdom prologue encouraging personal and communal renewal through scripture.[18]Content and Themes

Structure of the Psalm

Psalm 1 comprises six verses and lacks a superscription, a feature that distinguishes it from many other psalms in the Book of Psalms and highlights its function as an introductory piece to the Psalter.[19] This absence of a title or attribution emphasizes its programmatic role, setting the tone for the collection by contrasting paths of human conduct without tying it to a specific historical or authorial context.[20] The psalm exhibits a clear bipartite structure, dividing into two contrasting halves: verses 1–3 focus on the righteous individual, described as blessed for avoiding the counsel of the wicked and delighting in meditating on the Torah day and night, leading to prosperity and stability; verses 4–6 then shift to the wicked, portraying their instability and ultimate perishing under divine judgment.[19] This division employs antithesis as a primary poetic device, juxtaposing the enduring vitality of the righteous against the fleeting nature of the wicked, with verse 6 serving as a climactic summary: "For the Lord knows the way of the righteous, but the way of the wicked will perish."[3] Imagery reinforces this opposition, likening the righteous to a tree planted by streams of water that yields fruit in season and does not wither, symbolizing rootedness and divine favor, while the wicked are compared to chaff that the wind drives away, evoking worthlessness and dispersion.[19] Further poetic sophistication appears in the psalm's chiastic elements, particularly in the inverted parallels that mirror the progression from blessing to judgment and back to divine oversight, creating a balanced envelope around the central contrasts.[21] Classified as a wisdom psalm, it carries a didactic intent, instructing readers on moral choices and their consequences through this formal organization, and opens with a beatitude ("Blessed is the man") akin to those in wisdom literature such as Proverbs, which similarly extol the virtues of Torah observance and righteous living.[19]Key Themes

Psalm 1 begins with a beatitude pronouncing blessing upon the righteous individual who eschews the counsel of the wicked, the path of sinners, and the seat of scoffers, instead finding delight in the law of the Lord and meditating on it day and night.[22] This meditation represents continuous reflection and obedience to God's Torah, positioning it as the foundation for a life of true happiness and spiritual vitality.[6] Theologically, the Torah serves as the source of enduring prosperity, guiding the righteous toward stability and fruitfulness in all endeavors.[23] The psalm employs vivid imagery to depict the righteous as a tree planted by streams of water, one that yields its fruit in season and whose leaf does not wither, symbolizing prosperity, resilience, and divine sustenance even in adversity.[22] This metaphor echoes the description in Jeremiah 17:7–8 of the blessed person who trusts in the Lord, reinforcing themes of rootedness and unyielding vitality amid life's challenges.[22] In contrast, the wicked are likened to chaff that the wind drives away, portraying their transience, lack of substance, and inevitable judgment, as they cannot withstand the divine scrutiny at the judgment or in the assembly of the righteous.[23] At its core, Psalm 1 presents a stark contrast between two ways of life, termed derekh (way or path) in Hebrew: the path of Torah obedience leading to divine favor and endurance, versus the way of the wicked culminating in destruction and separation from God's presence.[6] The Lord is depicted as intimately knowing and watching over the way of the righteous, ensuring their protection and ultimate vindication, while the way of the wicked perishes under divine judgment.[22] This binary framework underscores the psalm's emphasis on moral discernment and the profound consequences of aligning with or against God's instruction.[24]Interpretations

In traditional Jewish exegesis, Psalm 1 underscores the path to blessing through diligent Torah study, portraying the righteous individual as one who meditates on God's law day and night, yielding spiritual fruitfulness like a tree planted by streams of water.[25] Christian interpretations often view the psalm as typologically foreshadowing Jesus Christ as the exemplary righteous one, who embodied perfect delight in God's law while rejecting the counsel of the wicked, thereby fulfilling the blessed state described. This reading connects to New Testament echoes, such as Jesus' assurance of paradise to the thief on the cross in Luke 23:43, symbolizing entry into eternal blessing for the repentant. During the Reformation, figures like Martin Luther emphasized the psalm's focus on meditating on Scripture alone (sola scriptura) as the sole source of righteousness and guidance, countering reliance on ecclesiastical traditions.[26][23][27] Modern scholarship in the 2020s, including Lifeway's 2025 Bible study series, interprets the psalm's meditation practice as cultivating psychological and spiritual resilience, with the tree metaphor illustrating stability and prosperity amid life's trials through rooted engagement with divine wisdom. Intertextual analyses position Psalms 1 and 2 as a unified messianic gateway to the Psalter, introducing themes of royal blessing and divine sonship.[28][29] Feminist readings critique the psalm's use of the Hebrew term ish ("man") in verse 1 as reflecting an androcentric lens, yet emphasize its universal applicability to anyone—regardless of gender—who delights in torah, allowing women to claim the blessed imagery for themselves.[30] Postcolonial interpretations scrutinize the binary of righteous versus wicked as reinforcing power dynamics, where the "wicked" (reshayim) may represent marginalized groups judged through dominant lenses, urging a reevaluation of such categorizations in contexts of oppression.[31]Text and Translations

Original Hebrew Text

The Masoretic Text of Psalm 1, as preserved in the Leningrad Codex (dated 1008 CE), forms the standard basis for the original Hebrew version of this psalm. This codex, the oldest complete manuscript of the Hebrew Bible, provides a vocalized and accented text that reflects the medieval Tiberian tradition of pronunciation and interpretation. The textual stability of the Psalter, including Psalm 1, is supported by ancient witnesses, which demonstrate close alignment with the Masoretic tradition despite minor orthographic variations.[32][33] The full Hebrew text of Psalm 1 (verses 1–6) from the Leningrad Codex is as follows:אַשְׁרֵ֥י הָ֭אִישׁ אֲשֶׁ֣ר לֹ֣א הָלַ֑ךְ בַּעֲצַ֖ת רְשָׁעִ֣ים וּבְדֶ֥רֶךְ חַ֝טָּאִ֗ים לֹ֣א עָמָֽד וּבְמֹושַׁ֥ב לֵ֝יצִ֗ים לֹ֣א יָשָֽׁב׃

כִּ֤י אִ֥ם בְּתוֹרַ֨ת ׀ יְהוָ֬ה חֶפְצ֑וֹ וּבְתוֹרָת֥וֹ יֶ֝הְגֶּ֗ה יוֹמָ֥ם וָלָֽיְלָה׃

וְהָיָ֗ה כְּעֵ֥ץ שָׁת֥וּל עַל־פַּלְגֵ֣י מַ֭יִם אֲשֶׁר פִּרְי֥וֹ יִתֵּ֗ן בְּעִתּ֫וֹ וְעָלֵ֥הוּ לֹֽא־יִבּ֑וֹל וְכֹ֖ל אֲשֶׁר־יַעֲשֵׂ֣הוּ יַצְלִֽיחַ׃

לֹא־כֵ֥ן הָרְשָׁעִ֑ים כִּ֥י אִם־כַּ֝מֹּ֗ץ אֲשֶׁר־תִּדְּפֶ֥נּוּ רֽוּחַ׃

עַל־כֵּ֣ן לֹא־יָקֻ֭מוּ רְשָׁעִ֣ים בַּמִּשְׁפָּ֑ט וְ֝חַטָּאִ֗ים בַּעֲדַ֥ת צַדִּיקִֽים׃

כִּֽי־יוֹדֵ֣עַ יְ֭הוָה דֶּ֣רֶךְ צַדִּיקִ֑ים וְדֶ֖רֶךְ רְשָׁעִ֣ים תֹאבֵֽד׃

אַשְׁרֵ֥י הָ֭אִישׁ אֲשֶׁ֣ר לֹ֣א הָלַ֑ךְ בַּעֲצַ֖ת רְשָׁעִ֣ים וּבְדֶ֥רֶךְ חַ֝טָּאִ֗ים לֹ֣א עָמָֽד וּבְמֹושַׁ֥ב לֵ֝יצִ֗ים לֹ֣א יָשָֽׁב׃

כִּ֤י אִ֥ם בְּתוֹרַ֨ת ׀ יְהוָ֬ה חֶפְצ֑וֹ וּבְתוֹרָת֥וֹ יֶ֝הְגֶּ֗ה יוֹמָ֥ם וָלָֽיְלָה׃

וְהָיָ֗ה כְּעֵ֥ץ שָׁת֥וּל עַל־פַּלְגֵ֣י מַ֭יִם אֲשֶׁר פִּרְי֥וֹ יִתֵּ֗ן בְּעִתּ֫וֹ וְעָלֵ֥הוּ לֹֽא־יִבּ֑וֹל וְכֹ֖ל אֲשֶׁר־יַעֲשֵׂ֣הוּ יַצְלִֽיחַ׃

לֹא־כֵ֥ן הָרְשָׁעִ֑ים כִּ֥י אִם־כַּ֝מֹּ֗ץ אֲשֶׁר־תִּדְּפֶ֥נּוּ רֽוּחַ׃

עַל־כֵּ֣ן לֹא־יָקֻ֭מוּ רְשָׁעִ֣ים בַּמִּשְׁפָּ֑ט וְ֝חַטָּאִ֗ים בַּעֲדַ֥ת צַדִּיקִֽים׃

כִּֽי־יוֹדֵ֣עַ יְ֭הוָה דֶּ֣רֶךְ צַדִּיקִ֑ים וְדֶ֖רֶךְ רְשָׁעִ֣ים תֹאבֵֽד׃

Ashrei ha-ish asher lo halakh ba'atsat resha'im uvederekh chatta'im lo amad uvemoshav letsim lo yashav.

Ki im betorat YHWH chefetso uvetorato yehgeh yomam valaylah.

Vehayah ke'ets shatul al-palgei mayim asher piryo yitten be'itto ve'alehu lo yibbol vekhol asher ya'asehu yatzliach.

Lo-khen ha-resha'im ki im-kammotz asher-tidpennu ruach.

Al-ken lo-yakumu resha'im bammishpat vechatta'im ba'adat tzaddikim.

Ki-yode'a YHWH derekh tzaddikim vederekh resha'im toved.

```[](https://biblehub.com/wlct/psalms/1.htm)

Key linguistic features include prominent terms that shape the psalm's contrast between the righteous and the wicked. The opening word *ashrei* (אַשְׁרֵי), often rendered as "blessed" or "happy," derives from a root implying a state of profound [well-being](/page/Well-being) or divine favor, setting a tone of beatitude. *Torah* (תּוֹרָה) in verse 2 refers to divine instruction or teaching, beyond mere "[law](/page/Law)," emphasizing meditative engagement. *Resha'im* (רְשָׁעִים), meaning "wicked" or "guilty," and *tzaddiq* (צַדִּיק), denoting "righteous" or "just," form the ethical binary central to the text, with *resha'im* appearing in plural to evoke a collective force.[](https://www.sefaria.org/Psalms.1?lang=bi)

Poetically, Psalm 1 lacks an [acrostic](/page/Acrostic) structure, unlike some later [psalms](/page/Psalms), but employs antithetic parallelism throughout, contrasting the righteous path with the wicked one. Notable [wordplay](/page/Word_play) appears in verse 1's progression *halakh* (walked), *amad* (stood), *yashav* (sat), illustrating a deepening entanglement in [evil](/page/Evil) through escalating degrees of association, from advice to companionship. This chiastic arrangement enhances the rhythmic flow, typical of Hebrew poetry without [rhyme](/page/Rhyme).[](https://mechon-mamre.org/p/pt/pt2601.htm)

### Major Translations

Psalm 1 has been translated into numerous languages across centuries, with significant versions shaping its interpretation in religious and cultural contexts. The Greek [Septuagint](/page/Septuagint), dating to the 3rd–2nd centuries BCE, renders the opening as "Makarios anēr hos ouk eporeuthē en boulē asebōn" (Μακάριος ἀνὴρ ὃς οὐκ ἐπορεύθη ἐν βουλῇ ἀσεβῶν), using *makarios* to translate the Hebrew *'ashre*, a term denoting profound [happiness](/page/Happiness) or [blessing](/page/Blessing) that influenced the [New Testament](/page/New_Testament) [Beatitudes](/page/Beatitudes) in [Matthew 5](/page/Matthew_5):3–11, where *makarios* similarly introduces declarations of blessedness.[](https://www.sats.edu.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Lioy-Psalm-1-and-the-Beatitudes-in-Matthew-5.pdf) The [Septuagint](/page/Septuagint) also includes slight expansions, such as in verse 3 describing the tree as "planted beside the outlets of the waters" (*pephyteumenon para tas diexodus tōn hydatōn*), emphasizing channels of flow rather than direct rivers.[](https://www.blueletterbible.org/lxx/psa/1/1/)

The Latin [Vulgate](/page/Vulgate), translated by [Jerome](/page/Jerome) in the late [4th century](/page/4th_century) CE, begins with "Beatus vir qui non abiit in consilio impiorum," establishing *beatus vir* as a foundational phrase that inspired numerous musical settings, including polyphonic motets by composers like [Claudio Monteverdi](/page/Claudio_Monteverdi) in his 1640 Selva morale e spirituale.[](https://baroque.boston/monteverdi-beatus-vir) This version closely mirrors the Hebrew structure while adapting it for Latin liturgical use, influencing Western Christian traditions.[](https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Psalmi%201&version=VULGATE)

In English translations, the King James Version (KJV, 1611) famously opens with "Blessed is [the man](/page/The_Man) that walketh not in the [counsel](/page/Counsel) of the ungodly, nor standeth in the way of sinners, nor sitteth in the seat of the scornful," retaining gender-specific language from the Hebrew *ha-'ish* ([the man](/page/The_Man)) to convey an archetypal figure of [righteousness](/page/Righteousness).[](https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Psalm%201&version=KJV) Modern versions address inclusivity: the [New International Version](/page/New_International_Version) (NIV, 2011 update) shifts to "Blessed is the one who does not walk in step with the wicked or stand in the way that sinners take or sit in the company of mockers," using gender-neutral terms to broaden applicability beyond male readers.[](https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Psalm%201&version=NIV) Similarly, the [New Revised Standard Version](/page/New_Revised_Standard_Version) Updated Edition (NRSVUE, 2021) employs plural inclusivity with "Happy are those who do not follow the advice of the wicked, or take the path that sinners tread, or sit in the seat of scoffers," reflecting contemporary scholarly efforts to avoid gender-specific assumptions while preserving the text's poetic intent.[](https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Psalm%201&version=NRSVUE) The Jewish Publication Society (JPS) 1917 translation maintains a more traditional tone: "Happy is [the man](/page/The_Man) that hath not walked in the [counsel](/page/Counsel) of the wicked, nor stood in the way of sinners, nor sat in the seat of the scornful," prioritizing fidelity to the [Masoretic Text](/page/Masoretic_Text) for Jewish readers.[](https://biblehub.com/jps/psalms/1.htm)

To illustrate key differences, the following table compares verse 1 (opening blessing and progression of sin) and verse 3 (tree imagery) across the original Hebrew (with transliteration), Septuagint Greek, Vulgate Latin, and a representative English rendering (NRSVUE for inclusivity).

| Verse | Hebrew (Masoretic, transliteration) | Septuagint (Greek) | Vulgate (Latin) | NRSVUE (English) |

|-------|------------------------------------|--------------------|-----------------|------------------|

| 1 | אַשְׁרֵי־הָאִישׁ אֲשֶׁר לֹא הָלַךְ בַּעֲצַת רְשָׁעִים וּבְדֶרֶךְ חַטָּאִים לֹא עָמָד וּבְמֹושַׁב לֵצִים לֹא יָשָׁב׃<br>(Ashrei ha-'ish asher lo halakh ba'atzat resha'im uvederekh chatta'im lo amad uvmoshav letzim lo yashav.) | Μακάριος ἀνὴρ ὃς οὐκ ἐπορεύθη ἐν βουλῇ ἀσεβῶν καὶ ἐν ὁδῷ ἁμαρτωλῶν οὐκ ἔστη καὶ ἐπὶ καθέδραν λοιμῶν οὐκ ἐκάθισεν.<br>(Makarios anēr hos ouk eporeuthē en boulē asebōn kai en hodō hamartōlōn ouk estē kai epi kathedran loimōn ouk ekathisen.) | Beatus vir qui non abiit in consilio impiorum, et in via peccatorum non stetit, et in cathedra pestilentiae non sedit.<br>(Beatus vir qui non abiit in consilio impiorum, et in via peccatorum non stetit, et in cathedra pestilentiae non sedit.) | Happy are those who do not follow the advice of the wicked, or take the path that sinners tread, or sit in the seat of scoffers.<br>(Happy are those who do not follow the advice of the wicked, or take the path that sinners tread, or sit in the seat of scoffers.) |

| 3 | וְהָיָה כְּעֵץ שָׁתוּל עַל־פַּלְגֵי מָיִם אֲשֶׁר פִּרְיוֹ יִתֵּן בְּעִתּוֹ וְעָלֵהוּ לֹא־יִבּוֹל וְכֹל אֲשֶׁר־יַעֲשֶׂה יַצְלִיחַ׃<br>(Vehayah ke'ets shatul al-palgei mayim asher piryo yitten be'itto ve'alehu lo-yibbol vekhol asher-ya'asehu yatzliach.) | καὶ ἔσται ὡς τὸ δένδρον τὸ πεφυτευμένον παρὰ τὰς διεξόδους τῶν ὑδάτων, ὃ τὸν καρπὸν αὐτοῦ δώσει ἐν καιρῷ αὐτοῦ, καὶ τὸ φύλλον αὐτοῦ οὐκ ἐξαμαρανθήσεται, καὶ πάντα ὅσα ἂν ποιῇ κατευοδωθήσεται.<br>(Kai estai hōs to dendron to pephyteumenon para tas diexodous tōn hydatōn, ho ton karpon autou dōsei en kairō autou, kai to phyllon autou ouk examaranthēsetai, kai panta hosa an poiēi kateuōdōthēsetai.) | Et erit tamquam lignum quod plantatum est secus decursus aquarum, quod fructum suum dabit in tempore suo: et folium ejus non defluet: et omnia quaecumque faciet prosperabuntur.<br>(Et erit tamquam lignum quod plantatum est secus decursus aquarum, quod fructum suum dabit in tempore suo: et folium ejus non defluet: et omnia quaecumque faciet prosperabuntur.) | They are like trees planted by streams of water, which yield their fruit in its season, and their leaves do not wither. In all that they do, they prosper.<br>(They are like trees planted by streams of water, which yield their fruit in its season, and their leaves do not wither. In all that they do, they prosper.) |

[](https://biblehub.com/text/psalms/1-1.htm)[](https://www.blueletterbible.org/lxx/psa/1/1/)[](https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Psalmi%201&version=VULGATE)[](https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Psalm%201&version=NRSVUE)

Interpretive variations appear in rendering the Hebrew *letzim* (לֵצִים) in verse 1, often translated as "scornful" in the KJV to evoke derisive [contempt](/page/Contempt), while the NIV uses "mockers" to highlight [imitation](/page/Imitation) and ridicule, and some scholarly analyses describe it as "scoffers" denoting cynical rejectors of [wisdom](/page/Wisdom).[](https://biblehub.com/text/psalms/1-1.htm)[](https://lettingthetextspeak.com/2013/07/12/moving-beyond-mockery/) Recent post-2020 readings, particularly in eco-theological contexts, reinterpret the verse 3 tree imagery—planted by streams and un-withering—as a model for sustainable [human](/page/Human) [flourishing](/page/Flourishing) amid environmental crises, emphasizing rootedness in [divine law](/page/Divine_law) as ecological [stewardship](/page/Stewardship).[](https://www.faraday.cam.ac.uk/churches/church-resources/posts/psalm-1-rainforest-trees-and-flourishing-disciples/)

## Religious Uses

### In Judaism

Psalm 1 occupies a prominent role in Jewish liturgy and devotional practice.

The psalm receives significant attention in rabbinic literature, particularly in the Mishnah. Pirkei Avot 3:3 interprets the phrase "nor sat in the seat of scoffers" from Psalm 1:1 as a warning against idle conversation, stating that if two people sit together without words of Torah between them, it constitutes the "seat of scoffers," but if Torah study occurs, the Divine Presence (Shekhinah) rests among them. This reference underscores the ethical imperative of Torah study as a communal and protective practice against moral decline.

### In Christianity

In Christian lectionaries, Psalm 1 serves as the responsorial psalm for Proper 18 in Year C of the Revised Common Lectionary, highlighting themes of delight in God's law and the prosperity of the righteous.[](https://www.lectionarypage.net/YearC_RCL/Pentecost/CProp18_RCL.html) Its emphasis on meditating on Scripture day and night resonates with Advent themes of spiritual preparation and discernment, often incorporated into seasonal reflections on righteous living in anticipation of Christ's incarnation.[](http://reformedworship.org/resource/advent-through-psalms)

Early [Church Fathers](/page/Church_Fathers), particularly St. Augustine, viewed Psalm 1 as a prophetic depiction of Christ, the blessed man who avoids the counsel of the ungodly, contrasting the heavenly city of God—built on love for [divine law](/page/Divine_law)—with the earthly city rooted in [self-love](/page/Self-love) and worldly pursuits.[](https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/1801001.htm) This patristic interpretation influenced later theology, including Lutheran traditions, where the psalm underscores the necessity of constant meditation on God's Word for faith formation, as emphasized by [Martin Luther](/page/Martin_Luther) in his teachings on Christian devotion.[](https://thelutheran.com.au/2021/02/26/christian-meditation-meeting-christ-in-scripture/)

Liturgically, Psalm 1 holds a prominent place in various Christian rites. In the Anglican [Book of Common Prayer](/page/Book_of_Common_Prayer), it forms the opening psalm for Morning Prayer on the first day of the monthly cycle, inviting daily reflection on blessedness through obedience to God.[](https://www.bcponline.org/Psalter/the_psalter.html) Similarly, in the Coptic Orthodox [Agpeya](/page/Agpeya), the [Book of Hours](/page/The_Book_of_Hours), Psalm 1 initiates the First Hour prayer each morning, symbolizing renewal through Christ's resurrection and the rejection of sinful paths.[](http://www.coptic.net/prayers/agpeya/First.html) Within Catholicism, the psalm appears in the [Liturgy of the Hours](/page/Liturgy_of_the_Hours) psalter, where its declarations of blessing parallel the [Beatitudes](/page/Beatitudes) in [Matthew 5](/page/Matthew_5), portraying the righteous as those who, like the poor in spirit and meek, inherit God's kingdom through faithful adherence to His teachings.[](https://www.sats.edu.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Lioy-Psalm-1-and-the-Beatitudes-in-Matthew-5.pdf)

Among Protestants, Puritan divines integrated Psalm 1 into daily recitations as part of disciplined prayer routines, using its imagery to cultivate habitual Scripture engagement and moral vigilance, as seen in the devotional expositions of figures like [Matthew Henry](/page/Matthew_Henry).[](https://foundationrt.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Old_Matthew_Henry.pdf) This tradition continues in modern contexts, such as Lifeway's 2025 "Explore the Bible" summer curriculum, which dedicates its first session to Psalm 1 under the title "God's Wisdom," guiding believers to apply the psalm's principles for spiritual fruitfulness and discernment in contemporary life.[](https://explorethebible.lifeway.com/uncategorized/helps-for-teaching-session-1-psalms-summer-2025/)

### In Islam and Other Traditions

In Islamic tradition, the [Psalms](/page/Psalms), known as the Zabur, are recognized as a holy book revealed by [God](/page/God) to the [Prophet](/page/Prophet) [David](/page/David) (Dawud), serving as a collection of hymns, praises, and exhortations rather than a book of law. The [Quran](/page/Quran) affirms this revelation in verses such as 4:163 ("and to David We gave the Psalms") and 17:55 ("And We have preferred some prophets over others, and We gave David, Psalms"), positioning the Zabur as part of the chain of divine scriptures preceding [the Gospel](/page/The_gospel) and the Quran itself. While specific psalms like Psalm 1 are not recited in Muslim worship, its themes of righteousness, meditation on divine guidance, and the contrast between the pious and the wicked resonate with broader Islamic emphases on [taqwa](/page/Taqwa) ([piety](/page/Piety)) and submission to God's will, inspiring spiritual reflection and moral exhortation.[](https://qurangallery.app/topics/zabur-psalms-david-islamic-scripture)[](https://www.eurasiareview.com/19122023-to-david-we-gave-psalms-to-resonate-universally-and-emotionally-oped/)[](https://www.eurasiareview.com/29052023-psalms-for-jews-christians-and-muslims-oped/)

Interfaith studies highlight shared Abrahamic themes in Psalm 1, such as adherence to [divine law](/page/Divine_law) and the pursuit of [righteousness](/page/Righteousness), which parallel Quranic injunctions like those in Surah 1 (Al-Fatiha) urging believers to seek the straight path and avoid misguidance. A 2023 analysis in *[Eurasia](/page/Eurasia) Review* underscores how the [Psalms](/page/Psalms) foster common ground among [Jews](/page/Jews), [Christians](/page/Christians), and [Muslims](/page/Muslims) by emphasizing [monotheism](/page/Monotheism), [justice](/page/Justice), and ethical living, with Psalm 1's imagery of the righteous as a fruitful [tree](/page/Tree) echoing prophetic calls to piety across traditions. In [Sufism](/page/Sufism), the mystical branch of [Islam](/page/Islam), practices of [dhikr](/page/Dhikr) (remembrance of God) and contemplation of sacred texts offer parallels to the psalm's call for meditating on scripture day and night, promoting inner purification and alignment with divine wisdom, though not directly referencing the biblical text.[](https://www.eurasiareview.com/29052023/psalms-for-jews-christians-and-muslims-oped/)[](https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/9/10/323)

Beyond Abrahamic faiths, the Bahá'í Faith regards the Psalms as part of ancient scriptures containing timeless truths and divine wisdom, integrated into its recognition of progressive revelation from earlier prophets like [David](/page/David). In non-Abrahamic traditions, engagement with Psalm 1 remains minimal, but comparative ethical studies draw parallels between its depiction of the righteous path and concepts like [dharma](/page/Dharma) in [Hinduism](/page/Hinduism) and [Buddhism](/page/Buddhism), where moral duty and non-violence ([ahimsa](/page/Ahimsa)) guide ethical conduct toward liberation, contrasting with the psalm's justice-oriented framework while highlighting universal themes of virtuous living over retribution.[](https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/14/2/203)

In the 2020s, Psalm 1 has featured in Muslim-Christian dialogues as a bridge for discussing righteousness and shared ethical foundations, exemplified by the Oxford Interfaith Forum's 2021 reading group on Psalms in multifaith contexts, which included inaugural sessions on Psalm 1 to explore interreligious hermeneutics. A 2023 publication, *Psalms, Islam, and Shalom*, further utilizes the Psalms' common heritage to promote dialogue, emphasizing musical and poetic elements of texts like Psalm 1 to foster peace and mutual understanding between communities.[](https://oxfordinterfaithforum.org/thematic-international-interfaith-reading-groups/psalms-in-interfaith-contexts-international-interfaith-reading-group/)[](https://www.fortresspress.com/store/product/9781506491196/Psalms-Islam-and-Shalom)

## Musical Settings

### Classical and Historical

In the Renaissance period, Thomas Tallis composed a setting of Psalm 1 as part of his contributions to Archbishop Matthew Parker's Psalter, published in 1567. Titled "Man blest no doubt," this English anthem tune for four voices presents a metrical paraphrase of the psalm in a simple, homophonic style suitable for congregational singing in the Anglican tradition.

The Baroque era saw further developments in Psalm 1 settings, notably Heinrich Schütz's German motet "Wer nicht sitzt im Gottlosen Rat" (SWV 97) from his Becker Psalter, Op. 5, composed around 1628. This polyphonic work for voices and instruments draws on the metrical psalter by Cornelius Becker, emphasizing the psalm's contrast between the righteous and the wicked through expressive word-painting and choral textures influenced by Italian models.[](https://genevanpsalter.blogspot.com/2012/07/heinrich-schutz-and-becker-psalter.html) Similarly, Marc-Antoine Charpentier created "Beatus vir qui non abiit," cataloged as H.175, circa 1670, a French motet for three voices, two treble instruments, and continuo that highlights the psalm's meditative tone with ornate melodic lines and basso continuo accompaniment.[](https://imslp.org/wiki/Beatus_vir,_H.175_(Charpentier,_Marc-Antoine))

Other notable pre-20th-century adaptations include literary-musical paraphrases, such as John Milton's metrical version of Psalm 1, "Bless'd is the man who hath not walk'd astray," completed in 1653 and intended for versified singing in Protestant worship. In the late [18th century](/page/18th_century), Scottish poet [Robert Burns](/page/Robert_Burns) offered a paraphrase around 1781, "The man, in life wherever plac'd," which adapted the psalm's themes of moral dichotomy into vernacular Scots verse, often set to simple folk-like melodies in Presbyterian contexts. Additionally, the [Gregorian chant](/page/Gregorian_chant) "Beatus vir qui non abiit" provided the foundational plainchant melody for Psalm 1, recited in Tone 1 during monastic and liturgical offices from the early medieval period onward.[](https://milton.host.dartmouth.edu/reading_room/psalms/psalm_1/text.shtml)[](https://www.bbc.co.uk/arts/robertburns/works/paraphrase_of_the_first_psalm/)[](https://www.lieder.net/lieder/get_text.html?TextId=106704)

Psalm 1 held significant liturgical roles in historical musical practices, appearing in Catholic [polyphony](/page/Polyphony) from the [15th century](/page/15th_century) as motets and antiphons in [vespers](/page/Vespers) and [matins](/page/Matins), where elaborate choral works underscored themes of blessedness and [divine law](/page/Divine_law).[](https://www.milkenarchive.org/articles/view/the-book-of-psalms-and-its-musical-interpretations/) In Lutheran traditions, the psalm inspired [chorale](/page/Chorale) settings up to the [19th century](/page/19th_century), including harmonizations in cantatas and organ preludes adapting metrical versions for congregational hymnody that emphasized personal piety and scriptural meditation.[](https://www.milkenarchive.org/articles/view/the-book-of-psalms-and-its-musical-interpretations/)

### Contemporary

In the 21st century, contemporary musical settings of Psalm 1 have proliferated within [Christian worship](/page/Christian_worship) music, often emphasizing accessibility and modern production for congregational use. The Psalms Project, initiated in [2012](/page/2012) by musician Shane Heilman, released a full album of verbatim settings for Psalms 1–10, including "Psalm 1: Everything He Does Shall Prosper" featuring Lance Edward, which blends acoustic folk elements with reflective lyrics drawn directly from the text.[](https://thepsalmsproject.com/) This project aimed to set all 150 Psalms to music, prioritizing scriptural fidelity in a [contemporary worship](/page/Contemporary_worship) style.[](https://music.apple.com/us/album/vol-1-psalms-1-10/1490354567)

Building on this momentum, the EveryPsalm initiative by the duo Poor Bishop Hooper launched in late 2019, committing to weekly releases of psalm-based songs through 2022 to cover the entire [Psalter](/page/Psalter). Their setting of Psalm 1, released on December 31, 2019, adopts an [indie folk](/page/Indie_folk) aesthetic with gentle instrumentation and introspective vocals, garnering over two million streams on [Spotify](/page/Spotify) as of 2025 and highlighting the project's role in revitalizing psalmody for modern listeners.[](https://www.everypsalm.com/) In 2020, the band Liturgical Folk issued their album *Psalm Settings*, featuring a verbatim choral arrangement of Psalm 1 in an [indie folk](/page/Indie_folk) genre, designed for liturgical contexts with layered harmonies and [acoustic guitar](/page/Acoustic_guitar).[](https://liturgicalfolk.bandcamp.com/album/psalm-settings)

Post-2020 releases continued to diversify genres, incorporating [contemporary Christian music](/page/Contemporary_Christian_music) (CCM) and electronic influences. Eleven22 Worship's 2022 track "I Delight (Psalm 1)" from *The Psalms EP* infuses upbeat CCM rhythms with electronic production, focusing on the psalm's theme of delighting in God's law for [worship](/page/Worship) settings.[](https://open.spotify.com/album/6T0tY1YM3iJvLjARsFmDM2) In 2024, Eternalgrace Music's *Singing the Psalms 1-10, Vol. 1* offered a modern praise album with Psalm 1 rendered in a soothing acoustic style, part of a broader effort to create [worship](/page/Worship) resources blending [indie folk](/page/Indie_folk) and CCM.[](https://open.spotify.com/album/6T0tY1YM3iJvLjARsFmDM2) By 2025, additional projects in modern [worship](/page/Worship) styles emerged, often featuring electronic beats and congregational choruses to emphasize the psalm's imagery of prosperity and rootedness.

Globally, adaptations in African gospel traditions have integrated Psalm 1 into rhythmic, communal expressions. For instance, a 2025 Afrobeat rendition of Psalm 1:1–3 by independent artists combines uplifting percussion and soulful vocals, reflecting West African principles of singable psalm translations for oral cultures.[](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bj_15TlXnr8) Choral works like the Kenyan folk-inspired *African Psalm* by Patrick Liebergen, which adapts psalm texts, employ call-and-response patterns to foster participatory worship.[](https://www.jwpepper.com/african-psalm-3014206/p) Online compilations, such as a 2025 [Substack](/page/Substack)-curated playlist spanning Psalms 1–150, aggregate diverse settings in indie folk, CCM, and other genres, making them accessible via streaming platforms for worldwide audiences.[](https://stillsmallvoice.substack.com/p/psalms-1-150-a-playlist-and-some)

Ashrei ha-ish asher lo halakh ba'atsat resha'im uvederekh chatta'im lo amad uvemoshav letsim lo yashav.

Ki im betorat YHWH chefetso uvetorato yehgeh yomam valaylah.

Vehayah ke'ets shatul al-palgei mayim asher piryo yitten be'itto ve'alehu lo yibbol vekhol asher ya'asehu yatzliach.

Lo-khen ha-resha'im ki im-kammotz asher-tidpennu ruach.

Al-ken lo-yakumu resha'im bammishpat vechatta'im ba'adat tzaddikim.

Ki-yode'a YHWH derekh tzaddikim vederekh resha'im toved.

```[](https://biblehub.com/wlct/psalms/1.htm)

Key linguistic features include prominent terms that shape the psalm's contrast between the righteous and the wicked. The opening word *ashrei* (אַשְׁרֵי), often rendered as "blessed" or "happy," derives from a root implying a state of profound [well-being](/page/Well-being) or divine favor, setting a tone of beatitude. *Torah* (תּוֹרָה) in verse 2 refers to divine instruction or teaching, beyond mere "[law](/page/Law)," emphasizing meditative engagement. *Resha'im* (רְשָׁעִים), meaning "wicked" or "guilty," and *tzaddiq* (צַדִּיק), denoting "righteous" or "just," form the ethical binary central to the text, with *resha'im* appearing in plural to evoke a collective force.[](https://www.sefaria.org/Psalms.1?lang=bi)

Poetically, Psalm 1 lacks an [acrostic](/page/Acrostic) structure, unlike some later [psalms](/page/Psalms), but employs antithetic parallelism throughout, contrasting the righteous path with the wicked one. Notable [wordplay](/page/Word_play) appears in verse 1's progression *halakh* (walked), *amad* (stood), *yashav* (sat), illustrating a deepening entanglement in [evil](/page/Evil) through escalating degrees of association, from advice to companionship. This chiastic arrangement enhances the rhythmic flow, typical of Hebrew poetry without [rhyme](/page/Rhyme).[](https://mechon-mamre.org/p/pt/pt2601.htm)

### Major Translations

Psalm 1 has been translated into numerous languages across centuries, with significant versions shaping its interpretation in religious and cultural contexts. The Greek [Septuagint](/page/Septuagint), dating to the 3rd–2nd centuries BCE, renders the opening as "Makarios anēr hos ouk eporeuthē en boulē asebōn" (Μακάριος ἀνὴρ ὃς οὐκ ἐπορεύθη ἐν βουλῇ ἀσεβῶν), using *makarios* to translate the Hebrew *'ashre*, a term denoting profound [happiness](/page/Happiness) or [blessing](/page/Blessing) that influenced the [New Testament](/page/New_Testament) [Beatitudes](/page/Beatitudes) in [Matthew 5](/page/Matthew_5):3–11, where *makarios* similarly introduces declarations of blessedness.[](https://www.sats.edu.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Lioy-Psalm-1-and-the-Beatitudes-in-Matthew-5.pdf) The [Septuagint](/page/Septuagint) also includes slight expansions, such as in verse 3 describing the tree as "planted beside the outlets of the waters" (*pephyteumenon para tas diexodus tōn hydatōn*), emphasizing channels of flow rather than direct rivers.[](https://www.blueletterbible.org/lxx/psa/1/1/)

The Latin [Vulgate](/page/Vulgate), translated by [Jerome](/page/Jerome) in the late [4th century](/page/4th_century) CE, begins with "Beatus vir qui non abiit in consilio impiorum," establishing *beatus vir* as a foundational phrase that inspired numerous musical settings, including polyphonic motets by composers like [Claudio Monteverdi](/page/Claudio_Monteverdi) in his 1640 Selva morale e spirituale.[](https://baroque.boston/monteverdi-beatus-vir) This version closely mirrors the Hebrew structure while adapting it for Latin liturgical use, influencing Western Christian traditions.[](https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Psalmi%201&version=VULGATE)

In English translations, the King James Version (KJV, 1611) famously opens with "Blessed is [the man](/page/The_Man) that walketh not in the [counsel](/page/Counsel) of the ungodly, nor standeth in the way of sinners, nor sitteth in the seat of the scornful," retaining gender-specific language from the Hebrew *ha-'ish* ([the man](/page/The_Man)) to convey an archetypal figure of [righteousness](/page/Righteousness).[](https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Psalm%201&version=KJV) Modern versions address inclusivity: the [New International Version](/page/New_International_Version) (NIV, 2011 update) shifts to "Blessed is the one who does not walk in step with the wicked or stand in the way that sinners take or sit in the company of mockers," using gender-neutral terms to broaden applicability beyond male readers.[](https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Psalm%201&version=NIV) Similarly, the [New Revised Standard Version](/page/New_Revised_Standard_Version) Updated Edition (NRSVUE, 2021) employs plural inclusivity with "Happy are those who do not follow the advice of the wicked, or take the path that sinners tread, or sit in the seat of scoffers," reflecting contemporary scholarly efforts to avoid gender-specific assumptions while preserving the text's poetic intent.[](https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Psalm%201&version=NRSVUE) The Jewish Publication Society (JPS) 1917 translation maintains a more traditional tone: "Happy is [the man](/page/The_Man) that hath not walked in the [counsel](/page/Counsel) of the wicked, nor stood in the way of sinners, nor sat in the seat of the scornful," prioritizing fidelity to the [Masoretic Text](/page/Masoretic_Text) for Jewish readers.[](https://biblehub.com/jps/psalms/1.htm)

To illustrate key differences, the following table compares verse 1 (opening blessing and progression of sin) and verse 3 (tree imagery) across the original Hebrew (with transliteration), Septuagint Greek, Vulgate Latin, and a representative English rendering (NRSVUE for inclusivity).

| Verse | Hebrew (Masoretic, transliteration) | Septuagint (Greek) | Vulgate (Latin) | NRSVUE (English) |

|-------|------------------------------------|--------------------|-----------------|------------------|

| 1 | אַשְׁרֵי־הָאִישׁ אֲשֶׁר לֹא הָלַךְ בַּעֲצַת רְשָׁעִים וּבְדֶרֶךְ חַטָּאִים לֹא עָמָד וּבְמֹושַׁב לֵצִים לֹא יָשָׁב׃<br>(Ashrei ha-'ish asher lo halakh ba'atzat resha'im uvederekh chatta'im lo amad uvmoshav letzim lo yashav.) | Μακάριος ἀνὴρ ὃς οὐκ ἐπορεύθη ἐν βουλῇ ἀσεβῶν καὶ ἐν ὁδῷ ἁμαρτωλῶν οὐκ ἔστη καὶ ἐπὶ καθέδραν λοιμῶν οὐκ ἐκάθισεν.<br>(Makarios anēr hos ouk eporeuthē en boulē asebōn kai en hodō hamartōlōn ouk estē kai epi kathedran loimōn ouk ekathisen.) | Beatus vir qui non abiit in consilio impiorum, et in via peccatorum non stetit, et in cathedra pestilentiae non sedit.<br>(Beatus vir qui non abiit in consilio impiorum, et in via peccatorum non stetit, et in cathedra pestilentiae non sedit.) | Happy are those who do not follow the advice of the wicked, or take the path that sinners tread, or sit in the seat of scoffers.<br>(Happy are those who do not follow the advice of the wicked, or take the path that sinners tread, or sit in the seat of scoffers.) |

| 3 | וְהָיָה כְּעֵץ שָׁתוּל עַל־פַּלְגֵי מָיִם אֲשֶׁר פִּרְיוֹ יִתֵּן בְּעִתּוֹ וְעָלֵהוּ לֹא־יִבּוֹל וְכֹל אֲשֶׁר־יַעֲשֶׂה יַצְלִיחַ׃<br>(Vehayah ke'ets shatul al-palgei mayim asher piryo yitten be'itto ve'alehu lo-yibbol vekhol asher-ya'asehu yatzliach.) | καὶ ἔσται ὡς τὸ δένδρον τὸ πεφυτευμένον παρὰ τὰς διεξόδους τῶν ὑδάτων, ὃ τὸν καρπὸν αὐτοῦ δώσει ἐν καιρῷ αὐτοῦ, καὶ τὸ φύλλον αὐτοῦ οὐκ ἐξαμαρανθήσεται, καὶ πάντα ὅσα ἂν ποιῇ κατευοδωθήσεται.<br>(Kai estai hōs to dendron to pephyteumenon para tas diexodous tōn hydatōn, ho ton karpon autou dōsei en kairō autou, kai to phyllon autou ouk examaranthēsetai, kai panta hosa an poiēi kateuōdōthēsetai.) | Et erit tamquam lignum quod plantatum est secus decursus aquarum, quod fructum suum dabit in tempore suo: et folium ejus non defluet: et omnia quaecumque faciet prosperabuntur.<br>(Et erit tamquam lignum quod plantatum est secus decursus aquarum, quod fructum suum dabit in tempore suo: et folium ejus non defluet: et omnia quaecumque faciet prosperabuntur.) | They are like trees planted by streams of water, which yield their fruit in its season, and their leaves do not wither. In all that they do, they prosper.<br>(They are like trees planted by streams of water, which yield their fruit in its season, and their leaves do not wither. In all that they do, they prosper.) |

[](https://biblehub.com/text/psalms/1-1.htm)[](https://www.blueletterbible.org/lxx/psa/1/1/)[](https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Psalmi%201&version=VULGATE)[](https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Psalm%201&version=NRSVUE)

Interpretive variations appear in rendering the Hebrew *letzim* (לֵצִים) in verse 1, often translated as "scornful" in the KJV to evoke derisive [contempt](/page/Contempt), while the NIV uses "mockers" to highlight [imitation](/page/Imitation) and ridicule, and some scholarly analyses describe it as "scoffers" denoting cynical rejectors of [wisdom](/page/Wisdom).[](https://biblehub.com/text/psalms/1-1.htm)[](https://lettingthetextspeak.com/2013/07/12/moving-beyond-mockery/) Recent post-2020 readings, particularly in eco-theological contexts, reinterpret the verse 3 tree imagery—planted by streams and un-withering—as a model for sustainable [human](/page/Human) [flourishing](/page/Flourishing) amid environmental crises, emphasizing rootedness in [divine law](/page/Divine_law) as ecological [stewardship](/page/Stewardship).[](https://www.faraday.cam.ac.uk/churches/church-resources/posts/psalm-1-rainforest-trees-and-flourishing-disciples/)

## Religious Uses

### In Judaism

Psalm 1 occupies a prominent role in Jewish liturgy and devotional practice.

The psalm receives significant attention in rabbinic literature, particularly in the Mishnah. Pirkei Avot 3:3 interprets the phrase "nor sat in the seat of scoffers" from Psalm 1:1 as a warning against idle conversation, stating that if two people sit together without words of Torah between them, it constitutes the "seat of scoffers," but if Torah study occurs, the Divine Presence (Shekhinah) rests among them. This reference underscores the ethical imperative of Torah study as a communal and protective practice against moral decline.

### In Christianity

In Christian lectionaries, Psalm 1 serves as the responsorial psalm for Proper 18 in Year C of the Revised Common Lectionary, highlighting themes of delight in God's law and the prosperity of the righteous.[](https://www.lectionarypage.net/YearC_RCL/Pentecost/CProp18_RCL.html) Its emphasis on meditating on Scripture day and night resonates with Advent themes of spiritual preparation and discernment, often incorporated into seasonal reflections on righteous living in anticipation of Christ's incarnation.[](http://reformedworship.org/resource/advent-through-psalms)

Early [Church Fathers](/page/Church_Fathers), particularly St. Augustine, viewed Psalm 1 as a prophetic depiction of Christ, the blessed man who avoids the counsel of the ungodly, contrasting the heavenly city of God—built on love for [divine law](/page/Divine_law)—with the earthly city rooted in [self-love](/page/Self-love) and worldly pursuits.[](https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/1801001.htm) This patristic interpretation influenced later theology, including Lutheran traditions, where the psalm underscores the necessity of constant meditation on God's Word for faith formation, as emphasized by [Martin Luther](/page/Martin_Luther) in his teachings on Christian devotion.[](https://thelutheran.com.au/2021/02/26/christian-meditation-meeting-christ-in-scripture/)

Liturgically, Psalm 1 holds a prominent place in various Christian rites. In the Anglican [Book of Common Prayer](/page/Book_of_Common_Prayer), it forms the opening psalm for Morning Prayer on the first day of the monthly cycle, inviting daily reflection on blessedness through obedience to God.[](https://www.bcponline.org/Psalter/the_psalter.html) Similarly, in the Coptic Orthodox [Agpeya](/page/Agpeya), the [Book of Hours](/page/The_Book_of_Hours), Psalm 1 initiates the First Hour prayer each morning, symbolizing renewal through Christ's resurrection and the rejection of sinful paths.[](http://www.coptic.net/prayers/agpeya/First.html) Within Catholicism, the psalm appears in the [Liturgy of the Hours](/page/Liturgy_of_the_Hours) psalter, where its declarations of blessing parallel the [Beatitudes](/page/Beatitudes) in [Matthew 5](/page/Matthew_5), portraying the righteous as those who, like the poor in spirit and meek, inherit God's kingdom through faithful adherence to His teachings.[](https://www.sats.edu.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Lioy-Psalm-1-and-the-Beatitudes-in-Matthew-5.pdf)

Among Protestants, Puritan divines integrated Psalm 1 into daily recitations as part of disciplined prayer routines, using its imagery to cultivate habitual Scripture engagement and moral vigilance, as seen in the devotional expositions of figures like [Matthew Henry](/page/Matthew_Henry).[](https://foundationrt.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Old_Matthew_Henry.pdf) This tradition continues in modern contexts, such as Lifeway's 2025 "Explore the Bible" summer curriculum, which dedicates its first session to Psalm 1 under the title "God's Wisdom," guiding believers to apply the psalm's principles for spiritual fruitfulness and discernment in contemporary life.[](https://explorethebible.lifeway.com/uncategorized/helps-for-teaching-session-1-psalms-summer-2025/)

### In Islam and Other Traditions

In Islamic tradition, the [Psalms](/page/Psalms), known as the Zabur, are recognized as a holy book revealed by [God](/page/God) to the [Prophet](/page/Prophet) [David](/page/David) (Dawud), serving as a collection of hymns, praises, and exhortations rather than a book of law. The [Quran](/page/Quran) affirms this revelation in verses such as 4:163 ("and to David We gave the Psalms") and 17:55 ("And We have preferred some prophets over others, and We gave David, Psalms"), positioning the Zabur as part of the chain of divine scriptures preceding [the Gospel](/page/The_gospel) and the Quran itself. While specific psalms like Psalm 1 are not recited in Muslim worship, its themes of righteousness, meditation on divine guidance, and the contrast between the pious and the wicked resonate with broader Islamic emphases on [taqwa](/page/Taqwa) ([piety](/page/Piety)) and submission to God's will, inspiring spiritual reflection and moral exhortation.[](https://qurangallery.app/topics/zabur-psalms-david-islamic-scripture)[](https://www.eurasiareview.com/19122023-to-david-we-gave-psalms-to-resonate-universally-and-emotionally-oped/)[](https://www.eurasiareview.com/29052023-psalms-for-jews-christians-and-muslims-oped/)

Interfaith studies highlight shared Abrahamic themes in Psalm 1, such as adherence to [divine law](/page/Divine_law) and the pursuit of [righteousness](/page/Righteousness), which parallel Quranic injunctions like those in Surah 1 (Al-Fatiha) urging believers to seek the straight path and avoid misguidance. A 2023 analysis in *[Eurasia](/page/Eurasia) Review* underscores how the [Psalms](/page/Psalms) foster common ground among [Jews](/page/Jews), [Christians](/page/Christians), and [Muslims](/page/Muslims) by emphasizing [monotheism](/page/Monotheism), [justice](/page/Justice), and ethical living, with Psalm 1's imagery of the righteous as a fruitful [tree](/page/Tree) echoing prophetic calls to piety across traditions. In [Sufism](/page/Sufism), the mystical branch of [Islam](/page/Islam), practices of [dhikr](/page/Dhikr) (remembrance of God) and contemplation of sacred texts offer parallels to the psalm's call for meditating on scripture day and night, promoting inner purification and alignment with divine wisdom, though not directly referencing the biblical text.[](https://www.eurasiareview.com/29052023/psalms-for-jews-christians-and-muslims-oped/)[](https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/9/10/323)

Beyond Abrahamic faiths, the Bahá'í Faith regards the Psalms as part of ancient scriptures containing timeless truths and divine wisdom, integrated into its recognition of progressive revelation from earlier prophets like [David](/page/David). In non-Abrahamic traditions, engagement with Psalm 1 remains minimal, but comparative ethical studies draw parallels between its depiction of the righteous path and concepts like [dharma](/page/Dharma) in [Hinduism](/page/Hinduism) and [Buddhism](/page/Buddhism), where moral duty and non-violence ([ahimsa](/page/Ahimsa)) guide ethical conduct toward liberation, contrasting with the psalm's justice-oriented framework while highlighting universal themes of virtuous living over retribution.[](https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/14/2/203)

In the 2020s, Psalm 1 has featured in Muslim-Christian dialogues as a bridge for discussing righteousness and shared ethical foundations, exemplified by the Oxford Interfaith Forum's 2021 reading group on Psalms in multifaith contexts, which included inaugural sessions on Psalm 1 to explore interreligious hermeneutics. A 2023 publication, *Psalms, Islam, and Shalom*, further utilizes the Psalms' common heritage to promote dialogue, emphasizing musical and poetic elements of texts like Psalm 1 to foster peace and mutual understanding between communities.[](https://oxfordinterfaithforum.org/thematic-international-interfaith-reading-groups/psalms-in-interfaith-contexts-international-interfaith-reading-group/)[](https://www.fortresspress.com/store/product/9781506491196/Psalms-Islam-and-Shalom)

## Musical Settings

### Classical and Historical

In the Renaissance period, Thomas Tallis composed a setting of Psalm 1 as part of his contributions to Archbishop Matthew Parker's Psalter, published in 1567. Titled "Man blest no doubt," this English anthem tune for four voices presents a metrical paraphrase of the psalm in a simple, homophonic style suitable for congregational singing in the Anglican tradition.

The Baroque era saw further developments in Psalm 1 settings, notably Heinrich Schütz's German motet "Wer nicht sitzt im Gottlosen Rat" (SWV 97) from his Becker Psalter, Op. 5, composed around 1628. This polyphonic work for voices and instruments draws on the metrical psalter by Cornelius Becker, emphasizing the psalm's contrast between the righteous and the wicked through expressive word-painting and choral textures influenced by Italian models.[](https://genevanpsalter.blogspot.com/2012/07/heinrich-schutz-and-becker-psalter.html) Similarly, Marc-Antoine Charpentier created "Beatus vir qui non abiit," cataloged as H.175, circa 1670, a French motet for three voices, two treble instruments, and continuo that highlights the psalm's meditative tone with ornate melodic lines and basso continuo accompaniment.[](https://imslp.org/wiki/Beatus_vir,_H.175_(Charpentier,_Marc-Antoine))

Other notable pre-20th-century adaptations include literary-musical paraphrases, such as John Milton's metrical version of Psalm 1, "Bless'd is the man who hath not walk'd astray," completed in 1653 and intended for versified singing in Protestant worship. In the late [18th century](/page/18th_century), Scottish poet [Robert Burns](/page/Robert_Burns) offered a paraphrase around 1781, "The man, in life wherever plac'd," which adapted the psalm's themes of moral dichotomy into vernacular Scots verse, often set to simple folk-like melodies in Presbyterian contexts. Additionally, the [Gregorian chant](/page/Gregorian_chant) "Beatus vir qui non abiit" provided the foundational plainchant melody for Psalm 1, recited in Tone 1 during monastic and liturgical offices from the early medieval period onward.[](https://milton.host.dartmouth.edu/reading_room/psalms/psalm_1/text.shtml)[](https://www.bbc.co.uk/arts/robertburns/works/paraphrase_of_the_first_psalm/)[](https://www.lieder.net/lieder/get_text.html?TextId=106704)

Psalm 1 held significant liturgical roles in historical musical practices, appearing in Catholic [polyphony](/page/Polyphony) from the [15th century](/page/15th_century) as motets and antiphons in [vespers](/page/Vespers) and [matins](/page/Matins), where elaborate choral works underscored themes of blessedness and [divine law](/page/Divine_law).[](https://www.milkenarchive.org/articles/view/the-book-of-psalms-and-its-musical-interpretations/) In Lutheran traditions, the psalm inspired [chorale](/page/Chorale) settings up to the [19th century](/page/19th_century), including harmonizations in cantatas and organ preludes adapting metrical versions for congregational hymnody that emphasized personal piety and scriptural meditation.[](https://www.milkenarchive.org/articles/view/the-book-of-psalms-and-its-musical-interpretations/)

### Contemporary

In the 21st century, contemporary musical settings of Psalm 1 have proliferated within [Christian worship](/page/Christian_worship) music, often emphasizing accessibility and modern production for congregational use. The Psalms Project, initiated in [2012](/page/2012) by musician Shane Heilman, released a full album of verbatim settings for Psalms 1–10, including "Psalm 1: Everything He Does Shall Prosper" featuring Lance Edward, which blends acoustic folk elements with reflective lyrics drawn directly from the text.[](https://thepsalmsproject.com/) This project aimed to set all 150 Psalms to music, prioritizing scriptural fidelity in a [contemporary worship](/page/Contemporary_worship) style.[](https://music.apple.com/us/album/vol-1-psalms-1-10/1490354567)

Building on this momentum, the EveryPsalm initiative by the duo Poor Bishop Hooper launched in late 2019, committing to weekly releases of psalm-based songs through 2022 to cover the entire [Psalter](/page/Psalter). Their setting of Psalm 1, released on December 31, 2019, adopts an [indie folk](/page/Indie_folk) aesthetic with gentle instrumentation and introspective vocals, garnering over two million streams on [Spotify](/page/Spotify) as of 2025 and highlighting the project's role in revitalizing psalmody for modern listeners.[](https://www.everypsalm.com/) In 2020, the band Liturgical Folk issued their album *Psalm Settings*, featuring a verbatim choral arrangement of Psalm 1 in an [indie folk](/page/Indie_folk) genre, designed for liturgical contexts with layered harmonies and [acoustic guitar](/page/Acoustic_guitar).[](https://liturgicalfolk.bandcamp.com/album/psalm-settings)

Post-2020 releases continued to diversify genres, incorporating [contemporary Christian music](/page/Contemporary_Christian_music) (CCM) and electronic influences. Eleven22 Worship's 2022 track "I Delight (Psalm 1)" from *The Psalms EP* infuses upbeat CCM rhythms with electronic production, focusing on the psalm's theme of delighting in God's law for [worship](/page/Worship) settings.[](https://open.spotify.com/album/6T0tY1YM3iJvLjARsFmDM2) In 2024, Eternalgrace Music's *Singing the Psalms 1-10, Vol. 1* offered a modern praise album with Psalm 1 rendered in a soothing acoustic style, part of a broader effort to create [worship](/page/Worship) resources blending [indie folk](/page/Indie_folk) and CCM.[](https://open.spotify.com/album/6T0tY1YM3iJvLjARsFmDM2) By 2025, additional projects in modern [worship](/page/Worship) styles emerged, often featuring electronic beats and congregational choruses to emphasize the psalm's imagery of prosperity and rootedness.

Globally, adaptations in African gospel traditions have integrated Psalm 1 into rhythmic, communal expressions. For instance, a 2025 Afrobeat rendition of Psalm 1:1–3 by independent artists combines uplifting percussion and soulful vocals, reflecting West African principles of singable psalm translations for oral cultures.[](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bj_15TlXnr8) Choral works like the Kenyan folk-inspired *African Psalm* by Patrick Liebergen, which adapts psalm texts, employ call-and-response patterns to foster participatory worship.[](https://www.jwpepper.com/african-psalm-3014206/p) Online compilations, such as a 2025 [Substack](/page/Substack)-curated playlist spanning Psalms 1–150, aggregate diverse settings in indie folk, CCM, and other genres, making them accessible via streaming platforms for worldwide audiences.[](https://stillsmallvoice.substack.com/p/psalms-1-150-a-playlist-and-some)