Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Platformer

View on Wikipedia

A platformer (also called a platform game) is a subgenre of action game in which the core objective is to move the player character between points in an environment. Platform games are characterized by levels with uneven terrain and suspended platforms that require jumping and climbing to traverse. Other acrobatic maneuvers may factor into the gameplay, such as swinging from vines or grappling hooks, jumping off walls, gliding through the air, or bouncing from springboards or trampolines.[1]

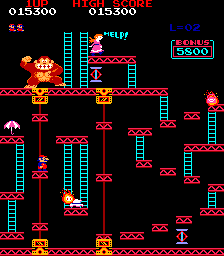

The genre started with the 1980 arcade video game Space Panic, which has ladders but not jumping. Donkey Kong, released in 1981, established a template for what were initially called "climbing games". Donkey Kong inspired many clones and games with similar elements, such as Miner 2049er (1982) and Kangaroo (1982), while the Sega arcade game Congo Bongo (1983) adds a third dimension via isometric graphics. Another popular game of that period, Pitfall! (1982), allows moving left and right through series of non-scrolling screens, expanding the play area. Nintendo's flagship Super Mario Bros. (1985) and the subsequent Super Mario series were the defining games for the genre, with horizontally scrolling levels and the player controlling a named character, Mario, which became Nintendo's mascot. The terms platform game and platformer gained traction in the late 1980s.

During their peak of popularity, platformers were estimated to comprise between a quarter and a third of all console games.[2] By 2006, sales had declined, representing a 2% market share as compared to 15% in 1998.[3] In spite of this, platformers are still being commercially released every year, including some which have sold millions of copies.

Concepts

[edit]A platformer requires the player to maneuver their character across platforms to reach a goal while confronting enemies and avoiding obstacles along the way. These games are either presented from the side view, using two-dimensional movement, or in 3D with the camera placed either behind the main character or in isometric perspective. Typical platforming gameplay tends to be very dynamic and challenges a player's reflexes, timing, and dexterity with controls.

The most common movement options in the genre are walking, running, jumping, attacking, and climbing. Jumping is central to the genre, though there are exceptions such as Nintendo's Popeye and Data East's BurgerTime, both from 1982. In some games, such as Donkey Kong, the trajectory of a jump is fixed, while in others it can be altered mid-air. Falling may cause damage or death. Many platformers contain environmental obstacles which kill the player's character upon contact, such as lava pits or bottomless chasms.[4] The player may be able to collect items and power-ups and give the main character new abilities for overcoming adversities.

Most games of this genre consist of multiple levels of increasing difficulty that may be interleaved by boss encounters, where the character has to defeat a particularly dangerous enemy to progress. Simple logical puzzles to resolve and skill trials to overcome are other common elements in the genre.

A modern variant of the platform game, especially significant on mobile platforms, is the endless runner, where the main character is always moving forward and the player must dodge or jump to avoid falling or hitting obstacles.

Naming

[edit]Various names were used in the years following the release of the first established game in the genre, Donkey Kong (1981). Shigeru Miyamoto originally called it a "running/jumping/climbing game" while developing it.[5] Miyamoto commonly used the term "athletic game" to refer to Donkey Kong and later games in the genre, such as Super Mario Bros. (1985).[6][7]

Donkey Kong spawned other games with a mix of running, jumping, and vertical traversal, a novel genre that did not match the style of games that came before it, leaving journalists and writers to offer their own terms.[8] Computer and Video Games magazine, among others, referred to the genre as "Donkey Kong-type" or "Kong-style" games.[8][9] "Climbing games" was used in Steve Bloom's 1982 book Video Invaders and 1983 magazines Electronic Games (US)—which ran a cover feature called "The Player's Guide to Climbing Games"—and TV Gamer (UK).[10][11][12] Bloom defined climbing games as those where the player "must climb from the bottom of the screen to the top while avoiding and/or destroying the obstacles and foes you invariably meet along the way". Under this definition, he listed Space Panic (1980), Donkey Kong, and, despite the top down perspective, Frogger (1981) as climbing games.[10]

In a December 1982 Creative Computing review of the Apple II game Beer Run, the reviewer used a different term: "I'm going to call this a ladder game, as in the 'ladder genre,' which includes Apple Panic and Donkey Kong."[13] That label was also used by Video Games Player magazine in 1983 when it named the Coleco port of Donkey Kong "Ladder Game of the Year".[14]

Another term used in the late 1980s to 1990s was "character action games", in reference to games based around named protagonists, such as Super Mario Bros.,[15] Sonic the Hedgehog,[16] and Bubsy.[17] It was also applied more generally to side-scrolling video games, including run and gun video games such as Gunstar Heroes.[18]

Platform game became a common term for the genre by 1989, popularized by its usage in the United Kingdom press.[19] Examples include referring to the "Super Mario mould" (such as Kato-chan & Ken-chan) as platform games,[20] and calling Strider a "platform and ladders" game.[21]

History

[edit]Single screen

[edit]

The genre originated in the early 1980s. Levels in early platform games were confined to a single screen, viewed in profile, with climbing between platforms.[4] Space Panic, a 1980 arcade release by Universal, is sometimes credited as the first platformer.[22] Space Panic has ladders and climbing, but not jumping. Another precursor to the genre from 1980 was Nichibutsu's Crazy Climber, in which the player character scales vertically scrolling skyscrapers.[23] The unreleased 1979 Intellivision game Hard Hat has a similar concept.[24]

Donkey Kong, an arcade video game created by Nintendo and released in July 1981, was the first game to allow players to jump over obstacles and gaps. It is widely considered to be the first platformer.[25][26] It introduced Mario. Donkey Kong was ported to many consoles and computers at the time, notably as the system-selling pack-in game for ColecoVision,[27] and also a handheld version from Coleco in 1982.[28] The game helped cement Nintendo's position as an important name in the video game industry internationally.[29]

Games with ladders and platforms rapidly followed from other developers, such as Kangaroo, BurgerTime, Canyon Climber, and Ponpoko, all from 1982. Also from the same year, Miner 2049er shipped with ten screens vs. Donkey Kong's four. Jumpman (1983) upped the count to 30. Mr. Robot and His Robot Factory (1984) includes a level editor.

Donkey Kong received a sequel, Donkey Kong Jr. (1982) and then Mario Bros. (1983), a platformer with two-player cooperative play. It laid the groundwork for other two-player cooperative games such as Fairyland Story and Bubble Bobble.

Beginning in 1982, transitional games emerged with non-scrolling levels spanning multiple screens. David Crane's Pitfall! for the Atari 2600, with 256 horizontally connected screens, became one of the best-selling games on the system and was a breakthrough for the genre. Smurf: Rescue in Gargamel's Castle was released on the ColecoVision that same year, adding uneven terrain and scrolling pans between static screens. Manic Miner (1983) and its sequel Jet Set Willy (1984) continued this style of multi-screen levels on home computers. Wanted: Monty Mole won the first award for Best Platform game in 1984 from Crash magazine.[30] Later that year, Epyx released Impossible Mission, and Parker Brothers released Montezuma's Revenge, which further expanded on the exploration aspect.

Scrolling

[edit]

The first platformer to use scrolling graphics came years before the genre became popular.[31] Jump Bug is a platform-shooter developed by Alpha Denshi under contract for Hoei/Coreland[32] and released to arcades in 1981, only five months after Donkey Kong.[33] Players control a bouncing car that jumps on various platforms such as buildings, clouds, and hills. Jump Bug offered a glimpse of what was to come, with uneven, suspended platforms, levels that scroll horizontally (and in one section, vertically), and differently themed sections, such as a city, the interior of a large pyramid, and underwater.[31][34]

Irem's 1982 arcade game Moon Patrol combines jumping over obstacles and shooting attackers. A month later, Taito released Jungle King, a side-scrolling action game with some platform elements: jumping between vines, jumping or running beneath bouncing boulders. It was quickly re-released as Jungle Hunt because of similarities to Tarzan.[35]

The 1982 Apple II game Track Attack includes a scrolling platform level where the character runs and leaps along the top of a moving train.[36] The character is little more than a stick figure, but the acrobatics evoke the movement that games such as Prince of Persia would feature. B.C.'s Quest For Tires (1983) put a recognizable character from American comic strips into side-scrolling, jumping gameplay similar to Moon Patrol.[37] The same year, Snokie for the Commodore 64 and Atari 8-bit computers added uneven terrain to a scrolling platformer.[38]

Based on the Saturday morning cartoon rather than the maze game, Namco's 1984 Pac-Land is a bidirectional, horizontally-scrolling, arcade video game with walking, running, jumping, springboards, power-ups, and a series of unique levels.[39] Pac-Man creator Toru Iwatani described the game as "the pioneer of action games with horizontally running background."[40] According to Iwatani, Shigeru Miyamoto described Pac-Land as an influence on the development of Super Mario Bros..[41][42]

Nintendo's Super Mario Bros., released for the Nintendo Entertainment System in 1985, became the archetype for the genre. It was bundled with Nintendo systems in North America, Japan, and Europe, and sold over 40 million copies, according to the 1999 Guinness Book of World Records. Its success as a pack-in led many companies to see platformers as vital to their success, and contributed greatly to popularizing the genre during the third and fourth generations of video game consoles.

Sega attempted to emulate this success with their Alex Kidd series, which started in 1986 on the Master System with Alex Kidd in Miracle World. It has horizontal and vertical scrolling levels, the ability to punch enemies and obstacles, and shops for the player to buy power-ups and vehicles.[43] Another Sega series that began that same year is Wonder Boy. The original Wonder Boy in 1986 was inspired more by Pac-Land than Super Mario Bros., with skateboarding segments that gave the game a greater sense of speed than other platformers at the time,[44] while its sequel, Wonder Boy in Monster Land added action-adventure and role-playing elements.[45] Wonder Boy in turn inspired games such as Adventure Island, Dynastic Hero, Popful Mail, and Shantae.[44]

One of the first platformers to scroll in all four directions freely and follow the on-screen character's movement is in a vector game called Major Havoc, which comprises a number of mini-games, including a simple platformer.[46] One of the first raster-based platformers to scroll fluidly in all directions in this manner is 1985's Legend of Kage.[citation needed]

In 1985, Enix released the action-adventure platformer Brain Breaker.[47] The following year saw the release of Nintendo's Metroid, which was critically acclaimed for a balance between open-ended and guided exploration. Another platform-adventure released that year, Pony Canyon's Super Pitfall, was critically panned for its vagueness and weak game design. That same year Jaleco released Esper Boukentai, a sequel to Psychic 5 that scrolled in all directions and allowed the player character to make huge multistory jumps to navigate the vertically oriented levels.[48] Telenet Japan also released its own take on the platform-action game, Valis, which contained anime-style cut scenes.[49]

In 1987, Capcom's Mega Man introduced non-linear level progression where the player is able to choose the order in which they complete levels. This was a stark contrast to both linear games like Super Mario Bros. and open-world games like Metroid. GamesRadar credits the "level select" feature of Mega Man as the basis for the non-linear mission structure found in most open-world, multi-mission, sidequest-heavy games.[50] Another Capcom platformer that year was Bionic Commando, which popularized a grappling hook mechanic that has since appeared in dozens of games, including Earthworm Jim and Tomb Raider.[51]

Scrolling platformers went portable in the late 1980s with games such as Super Mario Land, and the genre continued to maintain its popularity, with many games released for the handheld Game Boy and Game Gear systems.

Second-generation side-scrollers

[edit]By the time the Genesis and TurboGrafx-16 launched, platformers were the most popular genre in console gaming. There was a particular emphasis on having a flagship platform title exclusive to a system, featuring a mascot character. In 1989, Sega released Alex Kidd in the Enchanted Castle, which was only modestly successful. That same year, Capcom released Strider in arcades, which scrolled in multiple directions and allowed the player to summon artificial intelligence partners, such as a droid, tiger, and hawk, to help fight enemies.[52] Another Sega release in 1989 was Shadow Dancer, which is a game that also included an AI partner: a dog who followed the player around and aid in battle.[53] In 1990, Hudson Soft released Bonk's Adventure, with a protagonist positioned as NEC's mascot.[54] The following year, Takeru's Cocoron, a late platformer for the Famicom allowed players to build a character from a toy box filled with spare parts.[51]

In 1990, the Super Famicom was released in Japan, along with the eagerly anticipated Super Mario World. The following year, Nintendo released the console as the Super Nintendo Entertainment System in North America, along with Super Mario World, while Sega released Sonic the Hedgehog for the Sega Genesis.[55][56] Sonic showcased a new style of design made possible by a new generation of hardware: large stages that scrolled in all directions, curved hills, loops, and a physics system allowing players to rush through its levels with well-placed jumps and rolls. Sega characterized Sonic as a teenager with a rebellious personality to appeal to gamers who saw the previous generation of consoles as being for kids.[57] The character's speed showed off the hardware capabilities of the Genesis, which had a CPU clock speed approximately double that of the Super NES.

Sonic's perceived rebellious attitude became a model for game mascots. Other companies attempted to duplicate Sega's success with their own brightly colored anthropomorphisms with attitude.[58] These often were characterized by impatience, sarcasm, and frequent quips.

A second generation of platformers for computers appeared alongside the new wave of consoles. In the latter half of the 1980s and early 1990s, the Amiga was a strong gaming platform with its custom video hardware and sound hardware.[59] The Atari ST was solidly supported as well. Games like Shadow of the Beast and Turrican showed that computer platformers could rival their console contemporaries. Prince of Persia, originally a late release for the 8-bit Apple II in 1989, featured a high quality of animation.

The 1988 shareware game The Adventures of Captain Comic was one of the first attempts at a Nintendo-style platformer for IBM PC compatibles.[60] It inspired Commander Keen, released by id Software in 1990, which became the first MS-DOS platformer with smooth scrolling graphics.[61] Keen's success resulted in numerous console-styled platformers for MS-DOS compatible operating systems, including Duke Nukem, Duke Nukem II, Cosmo's Cosmic Adventure, and Dark Ages all by Apogee Software. These fueled a brief burst of episodic platformers where the first was freely distributed and parts 2 and 3 were available for purchase.

Decline of 2D

[edit]The abundance of platformers for 16-bit consoles continued late into the generation, with successful games such as Vectorman (1995), Donkey Kong Country 2: Diddy's Kong Quest (1995), and Super Mario World 2: Yoshi's Island (1995), but the release of new hardware caused players' attention to move away from 2D genres.[3] The Saturn, PlayStation, and Nintendo 64 nevertheless featured a number of successful 2D platformers. The 2D Rayman was a big success on 32-bit consoles. Mega Man 8 and Mega Man X4 helped revitalize interest in Capcom's Mega Man character. Castlevania: Symphony of the Night revitalized its series and established a new foundation for later Castlevania games. Oddworld and Heart of Darkness kept the subgenre born from Prince of Persia alive.

The difficulties of adapting platformer gameplay to three dimensions led some developers to compromise by pairing the visual flash of 3D with traditional 2D side scrolling gameplay. These games are often referred to as 2.5D.[62] The first such game was Saturn launch title, Clockwork Knight (1994). The game featured levels and boss characters rendered in 3D, but retained 2D gameplay and used pre-rendered 2D sprites for regular characters, similar to Donkey Kong Country. Its sequel improved upon its design, featuring some 3D effects such as hopping between the foreground and background, and the camera panning and curving around corners. Meanwhile, Pandemonium and Klonoa brought the 2.5D style to the PlayStation. In a break from the past, the Nintendo 64 had the fewest side scrolling platformers with only four, those being Yoshi's Story, Kirby 64: The Crystal Shards, Goemon's Great Adventure, and Mischief Makers—and most met with a tepid response from critics at the time.[63][64] Despite this, Yoshi's Story sold over a million copies in the US,[65] and Mischief Makers rode high on the charts in the months following its release.[66][67]

Third dimension

[edit]The term 3D platformer usually refers to games with gameplay in three dimensions and polygonal 3D graphics. Games that have 3D gameplay but 2D graphics are usually included under the umbrella of isometric platformers, while those that have 3D graphics but gameplay on a 2D plane are called 2.5D, as they are a blend of 2D and 3D.

The first platformers to simulate a 3D perspective and moving camera emerged in the early-mid-1980s. An early example of this was Konami's Antarctic Adventure,[68] where the player controls a penguin in a forward-scrolling third-person perspective while having to jump over pits and obstacles.[68][69][70] Originally released in 1983 for the MSX computer, it was subsequently ported to various platforms the following year,[70] including an arcade video game version,[68] NES,[70] and ColecoVision.[69]

1986 saw the release of the sequel to forward-scrolling platformer Antarctic Adventure called Penguin Adventure, which was designed by Hideo Kojima.[71] It included more action game elements, a greater variety of levels, RPG elements such as upgrading equipment,[72] and multiple endings.[73]

In early 1987, Square released 3-D WorldRunner, designed by Hironobu Sakaguchi and Nasir Gebelli.[74][75] Using a forward-scrolling effect similar to Sega's 1985 third-person rail shooter Space Harrier.[74] 3-D WorldRunner was an early forward-scrolling pseudo-3D third-person platform-action game where players were free to move in any forward-scrolling direction and could leap over obstacles and chasms. It was notable for being one of the first stereoscopic 3-D games.[75] Square released its sequel, JJ, later that year.[76]

The earliest example of a true 3D platformer is a French computer game called Alpha Waves, created by Christophe de Dinechin and published by Infogrames in 1990 for the Atari ST, Amiga, and IBM PC compatibles.[77][78]

Bug!, released in 1995 for the Saturn, has a more conservative approach. It allows players to move in all directions, but it does not allow movement along more than one axis at once; the player can move orthogonally but not diagonally. Its characters were pre-rendered sprites, much like the earlier Clockwork Knight. The game plays very similarly to 2D platformers, but lets players walk up walls and on ceilings.

In 1995, Delphine Software released a 3D sequel to their 2D platformer Flashback. Entitled Fade to Black, it was the first attempt to bring a popular 2D platformer series into 3D. While it retained the puzzle-oriented level design style and step-based control, it did not meet the criteria of a platformer, and was billed as an action adventure.[79] It used true 3D characters and set pieces, but its environments were rendered using a rigid engine similar to the one used by Wolfenstein 3D, in that it could only render square, flat corridors, rather than suspended platforms that could be jumped between.

Sega had tasked their American studio, Sega Technical Institute, with bringing Sonic the Hedgehog into 3D. Their project, titled Sonic Xtreme, was to have featured a radically different approach for the series, with an exaggerated fisheye camera and multidirectional gameplay reminiscent of Bug!. Due in part to conflicts with Sega Enterprises in Japan and a rushed schedule, the game never made it to market.[55]

True 3D

[edit]In the 1990s, platforming games started to shift from pseudo-3D to "true 3D," which gave the player more control over the character and the camera. To render a 3D environment from any angle the user chose, the graphics hardware had to be sufficiently powerful, and the art and rendering model of the game had to be viewable from every angle. The improvement in graphics technology allowed publishers to make such games but introduced several new issues. For example, if the player could control the virtual camera, it had to be constrained to stop it from clipping through the environment.[4]

In 1994, a small developer called Exact released a game for the X68000 computer called Geograph Seal, which was a 3D first-person shooter game with platforming. Players piloted a frog-like mech that could jump and then double-jump or triple-jump high into the air as the camera panned down to help players line up their landings. In addition to shooting, jumping on enemies was a primary way to attack.[80] This was the first true 3D platform-action game with free-roaming environments, but it was never ported to another platform or released outside Japan, so it remains relatively unknown in the West.[81]

The following year, Exact released their follow-up to Geograph Seal. An early title for Sony's new PlayStation console, Jumping Flash!, released in April 1995, kept the gameplay from its precursor but traded the frog-like mech for a cartoony rabbit mech called Robbit.[82] The title was successful enough to get two sequels and is remembered for being the first 3D platformer on a console.[81] Rob Fahey of Eurogamer said Jumping Flash was perhaps "one of the most important ancestors of every 3D platformer in the following decade."[83] It holds the record of "First platform videogame in true 3D" according to Guinness World Records.[84] Another early 3D platformer was Floating Runner, developed by a Japanese company called Xing and released for PlayStation in early 1996, before the release of Super Mario 64. Floating Runner uses D-pad controls and a behind-the-character camera perspective.[85]

In 1996, Nintendo released Super Mario 64, which is a game that set the standard for 3D platformers. It let the player explore 3D environments with greater freedom than was found in any previous game in the genre. With this in mind, Nintendo put an analog control stick on its Nintendo 64 controller, a feature that had not been seen since the Vectrex but which has since become standard. The analog stick provided the fine precision needed with a free perspective.

In most 2D platformers, the player finished a level by following a path to a certain point, but in Super Mario 64, the levels were open and had objectives. Completing objectives earned the player stars, and stars were used to unlock more levels. This approach allowed for more efficient use of large 3D areas and rewarded the player for exploration, but it meant less jumping and more action-adventure. Even so, a handful of boss levels offered more traditional platforming.[86] Until then there was no settled way to make 3D platformers, but Super Mario 64 inspired a shift in design. Later 3D platformers like Banjo-Kazooie, Spyro the Dragon, and Donkey Kong 64 borrowed its format, and the "collect-a-thon" genre began to form.

In order to make this free-roaming model work, developers had to program dynamic, intelligent cameras. A free camera made it harder for players to judge the height and distance of platforms, making jumping puzzles more difficult. Some of the more linear 3D platformers like Tork: Prehistoric Punk and Wario World used scripted cameras that limited player control. Games with more open environments like Super Mario 64 and Banjo-Kazooie used intelligent cameras that followed the player's movements.[87] Still, when the view was obstructed or not facing what the player needed to see, these intelligent cameras needed to be adjusted by the player.

In the 1990s, RPGs, first-person shooters, and more complex action-adventure games captured significant market share. Even so, the platformer thrived. Tomb Raider became one of the bestselling series on the PlayStation, along with Insomniac Games' Spyro and Naughty Dog's Crash Bandicoot, one of the few 3D games to stick with linear levels. Moreover, many of the Nintendo 64's bestsellers were first- and second-party platformers like Super Mario 64, Banjo-Kazooie, and Donkey Kong 64.[88] On Windows and Mac, Pangea Software's Bugdom series and BioWare's MDK2 proved successful.

Several developers who found success with 3D platformers began experimenting with titles that, despite their cartoon art style, were aimed at adults. Examples include Rare's Conker's Bad Fur Day, Crystal Dynamics's Gex: Deep Cover Gecko and Legacy of Kain: Soul Reaver, and Shiny Entertainment's Messiah.

In 1998, Sega produced a 3D Sonic game, Sonic Adventure, for its Dreamcast console. It used a hub structure like Super Mario 64, but its levels were more linear, fast-paced, and action-oriented.[89]

Into the 21st century

[edit]Nintendo released Super Mario Sunshine for the GameCube in 2002, the second 3D Mario platformer.

Other notable 3D platformers trickled out during this generation. Maximo was a spiritual heir to the Ghosts'n Goblins series, Billy Hatcher and the Giant Egg offered Yuji Naka's take on a Mario 64-influenced platformer, Argonaut Software returned with a new platformer named Malice, games such as Dragon's Lair 3D: Return to the Lair and Pitfall: The Lost Expedition were attempts to modernise classic video games of the 1980s using the 3D platformer genre, Psychonauts became a critical darling based on its imaginative levels and colorful characters, and several franchises that debuted during the sixth generation of consoles such as Tak and Ty the Tasmanian Tiger each developed a cult following. In Europe specifically, the Kao the Kangaroo and Hugo series achieved popularity and sold well. Rayman's popularity continued, though the franchise's third game was not as well received as the first two.[90][91] Oddworld: Munch's Oddysee brought the popular Oddworld franchise into the third dimension, but future sequels to this game did not opt for the 3D platform genre.

Naughty Dog moved on from Crash Bandicoot to Jak and Daxter, a series that became less about traditional platforming with each sequel.[92] A hybrid platformer/shooter game from Insomniac Games called Ratchet & Clank further pushed the genre away from such gameplay, as did Universal Interactive Studios' rebooted Spyro trilogy and Microsoft's attempt to create a mascot for the Xbox in Blinx: The Time Sweeper. Ironically, Microsoft later found more success with their 2003 take on the genre, Voodoo Vince.

In 2008, Crackpot Entertainment released Insecticide. Crackpot, composed of former developers from LucasArts, for the first time combined influences from the point and click genre LucasArts had been known for on titles such as Grim Fandango with a platformer.

The platformer remained a vital genre, but it never regained its past popularity. Part of the reason for the platformer's decline in the 2000s was a lack of innovation compared to other genres. Platformers were either aimed at younger players or designed to avoid the platform label.[93] In 1998, platformers had a 15% share of the market, and an even higher share in their prime. Four years later that figure had dropped to 2%.[3] Even the acclaimed Psychonauts saw modest sales at first, leading publisher Majesco Entertainment to withdraw from high-budget console games,[94] though its sales in Europe were respectable.[95]

Recent developments

[edit]

In the seventh generation of consoles, despite the genre having a smaller presence in the gaming market, some platformers found success. In late 2007, Super Mario Galaxy and Ratchet & Clank Future: Tools of Destruction were received well by both critics and fans.[96][97][98] Super Mario Galaxy was awarded the Best Game of 2007 by high-profile gaming websites like GameSpot, IGN, and GameTrailers. At that point, according to GameRankings, it was the most critically acclaimed game of all time. In 2008, LittleBigPlanet paired traditional 2D-platformer gameplay with physics simulation and user created content, earning it strong sales and good reviews. Electronic Arts released Mirror's Edge, which coupled platformer gameplay with a first-person perspective, although they did not market the game as a platformer because of the association of the label with games made for kids.[citation needed] Sonic Unleashed featured stages with both 2D and 3D platformer gameplay, a formula used later in Sonic Colors and Sonic Generations. Moreover, two Crash Bandicoot platformers were released in 2007 and 2008, and in 2013, RobTop Games, an indie developer, made Geometry Dash.

The popularity of 2D platformers rose in the 2010s. Nintendo revived the genre. New Super Mario Bros. was released in 2006 and sold 30 million copies worldwide, making it the best-selling game for the Nintendo DS and the fourth best-selling non-bundled video game of all time.[99] Super Mario Galaxy eventually sold over eight million units,[99] while Super Paper Mario, Super Mario 64 DS, Sonic Rush, Yoshi's Island DS, Kirby Super Star Ultra, and Kirby: Squeak Squad also sold well.

After the success of New Super Mario Bros., there was a spate of 2D platformers. These ranged from revivals like Bionic Commando: Rearmed, Contra ReBirth, Sonic the Hedgehog 4, and Rayman Origins to original titles like Splosion Man and Henry Hatsworth in the Puzzling Adventure. Wario Land: The Shake Dimension, released in 2008, was a 2D platformer with a rich visual style. Later games like Limbo, Super Meat Boy, Braid, Geometry Dash, A Boy and His Blob, and The Behemoth's BattleBlock Theater also used 2D graphics. New Super Mario Bros. Wii is especially notable because unlike most 2D platformers in the twenty-first century, it came out for a non-portable console and was not restricted to a content delivery network. A year after the success of New Super Mario Bros. Wii, Nintendo released more 2D platformers in their classic franchises: Donkey Kong Country Returns and Kirby's Return to Dream Land. In 2012, they released two more 2D platformers: New Super Mario Bros. 2 for the 3DS and New Super Mario Bros. U for the Wii U. Nintendo also experimented with 3D platformers that had gameplay elements from 2D platformers, leading to Super Mario 3D Land (2011) for the 3DS and Super Mario 3D World (2013) for the Wii U, the latter having cooperative multiplayer. Both were critical and commercial successes.

Games from independent developers in the late 2000s and the 2010s helped grow the platform-game market. These had a stronger focus on story and innovation.[93] In 2009, Frozenbyte released Trine, a 2.5D platformer that mixed traditional elements with physics puzzles. The game sold more than 1.1 million copies, and a sequel, Trine 2, came out in 2011.[100]

The year 2017 saw the release of several 3D platformers, including Yooka-Laylee and A Hat in Time, both crowdfunded on the website Kickstarter. Super Mario Odyssey, which returned the series to the open-ended gameplay of Super Mario 64, became one of the best-selling and best-reviewed games in the franchise's history. Super Lucky's Tale came out for Microsoft Windows and Xbox One. Snake Pass was called a "puzzle-platformer without a jump button." The Crash Bandicoot N. Sane Trilogy for PlayStation 4 sold over 2.5 million copies in three months,[101] despite some critics noting it was harder than the original games. The next few years saw more remakes of 3D platformers: Spyro Reignited Trilogy (2018) and SpongeBob SquarePants: Battle for Bikini Bottom – Rehydrated (2020).

In the ninth generation of consoles, the platformer remains important. Astro Bot Rescue Mission (2018), a PlayStation VR game, was followed by Astro's Playroom (2020), which came pre-installed on every PlayStation 5. Sackboy: A Big Adventure (2020), developed by Sumo Digital, was a PlayStation 5 launch title. Crash Bandicoot 4: It's About Time (2020) was released to critical praise. Bowser's Fury (2021), a short campaign added to the Switch port of Super Mario 3D World, bridged the gap between the gameplay of 3D World and that of Odyssey. Ratchet & Clank: Rift Apart (2021) was one of the first PlayStation 5-exclusive games made by Insomniac. On August 25, 2021, the Kickstarter-funded Psychonauts 2 was released to critical acclaim. Fall Guys (2020) amalgamates platforming elements into the battle royale genre, and was a critical and commercial success. In 2024, the third game in the Astro Bot series, Astro Bot, was released to widespread critical acclaim, becoming the highest-rated game of the year on OpenCritic.[102]

Subgenres

[edit]This list some definable platformers in the following types, but there are also many vaguely defined subgenres games that have not been listed. These game categories are the prototypes genre that recognized by different platform styles.

Puzzle-platformer

[edit]Puzzle-platformers are characterized by their use of a platformer structure to drive a game whose challenge is derived primarily from puzzles.[103]

Enix's 1983 release Door Door and Sega's 1985 release Doki Doki Penguin Land (for the SG-1000) are perhaps the first examples, though the genre is diverse, and classifications can vary.[104] Doki Doki Penguin Land allowed players to run and jump in typical platform fashion, but they could also destroy blocks, and were tasked with guiding an egg to the bottom of the level without letting it break.[104]

The Lost Vikings (1993) was a popular game in this genre. It has three characters players can switch between, each with different abilities. All three characters are needed to complete the level goals.[105]

This subgenre has a strong presence on handheld systems. Wario Land 2 moved the Wario series into the puzzle-platform genre by eliminating the element of death and adding temporary injuries, such as being squashed or lit on fire, and specialized powers.[106] Wario Land 3 continued this tradition, while Wario Land 4 was more of a mix of puzzle and traditional platform elements. The Game Boy update of Donkey Kong was also successful and saw a sequel on Game Boy Advance: Mario vs. Donkey Kong. Klonoa: Empire of Dreams, the first handheld title in its series, is also a puzzle-platformer.[107]

Through independent game development, this genre has experienced a revival since 2014. Braid uses time manipulation for its puzzles, and And Yet It Moves uses frame of reference rotation.[108] In contrast to these side-scrollers, Narbacular Drop and its successor, Portal, are first-person games that use portals to solve puzzles in 3D. Since the release of Portal, there have been more puzzle-platformers which use a first-person camera, including Tag: The Power of Paint and Antichamber.[109] In 2014, Nintendo released Captain Toad: Treasure Tracker which uses compact level design and camera rotation in order to reach the goal and find secrets and collectibles. Despite lacking jump ability, Toad still navigates the environment via unique movement mechanics.

Run-and-gun platformer

[edit]

The run-and-gun platform genre was popularised by Konami's Contra.[110] Among the most popular games in this style are Gunstar Heroes and Metal Slug.[111] Side-scrolling run-and-gun games marry platformers with shoot 'em ups, with less tricky platforming and more shooting. These games are sometimes called platform shooters. The genre has arcade roots, so these games are generally linear and difficult.

There are games which have a lot of shooting but do not fall in this subgenre. Mega Man, Metroid, Ghosts 'n Goblins, Vectorman, Jazz Jackrabbit, Earthworm Jim, Turrican, Cuphead and Enchanted Portals are all platformers with shooting, but unlike Contra or Metal Slug, platforming, as well as exploring and back-tracking, figures prominently. Run-and-gun games are generally pure, and while they may have vehicular sequences or other shifts in style, they have shooting throughout.[opinion]

Cinematic platformer

[edit]Cinematic platformers are a small but distinct subgenre, usually distinguished by their relative realism. These games focus on fluid, lifelike movements, without the unnatural physics found in nearly all other platformers, and they additionally often have an absent or minimal HUD.[112] To achieve this realism, many cinematic platformers, beginning with Prince of Persia, have employed rotoscoping techniques to animate their characters based on video footage of live actors performing the same stunts.[113] Jumping abilities are typically roughly within the confines of an athletic human's capacity. To expand vertical exploration, many cinematic platformers feature the ability to grab onto ledges, or make extensive use of elevator platforms.[112]

As these games tend to feature vulnerable characters who may die as the result of a single enemy attack or by falling a relatively short distance, they almost never have limited lives or continues. Challenge is derived from trial and error problem solving, forcing the player to find the right way to overcome a particular obstacle.[114]

Prince of Persia was the first cinematic platformer and perhaps the most influential.[115] Impossible Mission pioneered many of the defining elements of cinematic platformers and is an important precursor to this genre.[116] Other games in the genre include Flashback (and its 2013 remake), ReCore, Another World, Heart of Darkness, the first two Oddworld games, Blackthorne, Bermuda Syndrome, Generations Lost, Heart of the Alien, Weird Dreams, Limbo, Inside, onEscapee, Deadlight, The Way, Lunark, Planet of Lana and Full Void. Tomb Raider was the first cinematic platformer to utilize real-time 3D graphics.

Comical action game

[edit]Games in the genre are most commonly called "comical action games" (CAGs) in Japan.[117][118] The original arcade Mario Bros. is generally recognized as the originator of this genre, though Bubble Bobble is also highly influential.[119] These games are characterized by single screen, non-scrolling levels and often contain cooperative two-player action. A level is cleared when all enemies on the screen have been defeated, and vanquished foes usually drop score bonuses in the form of fruit or other items. CAGs are almost exclusively developed in Japan and are either arcade games, or sequels to arcade games, though they are also a common genre among amateur doujinshi games. Other examples include Don Doko Don, Snow Bros. and Nightmare in the Dark.

Isometric platformer

[edit]

Isometric platformers present a three-dimensional environment using two-dimensional graphics in isometric projection. The use of isometric graphics was popularized by Sega's arcade isometric shooter Zaxxon (1981),[120] which Sega followed with the arcade isometric platformer Congo Bongo, released in February 1983.[121] Another early isometric platformer, the ZX Spectrum game Ant Attack, was later released in November 1983.[122]

Knight Lore, an isometric sequel to Sabre Wulf, helped to establish the conventions of early isometric platformers. This formula was repeated in later games like Head Over Heels and Monster Max. These games were generally heavily focused on exploring indoor environments, usually a series of small rooms connected by doors, and have distinct adventure and puzzle elements. Japanese developers blended this gameplay style with that of Japanese action-adventure games like The Legend of Zelda to create games like Land Stalker and Light Crusader. This influence later traveled to Europe with Adeline Software's sprawling epic Little Big Adventure, which blended RPG, adventure, and isometric platforming elements.[123]

Before consoles were able to display true polygonal 3D graphics, the ¾ isometric perspective was used to move some popular 2D platformers into three-dimensional gameplay. Spot Goes To Hollywood was a sequel to the popular Cool Spot, and Sonic 3D Blast was Sonic's outing into the isometric subgenre.

Platform-adventure game

[edit]This section may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (July 2024) |

Many games fuse platformer fundamentals with elements of action-adventure games[failed verification], such as The Legend of Zelda, or with elements of RPGs.[failed verification] Typically these elements include the ability to explore an area freely, with access to new areas granted by either gaining new abilities or using inventory items. Many 2D games in the Metroid and Castlevania franchises are among the most popular games of this sort, and so games that take this type of approach are often labeled as "Metroidvania" games.[124] Castlevania: Symphony of the Night popularized this approach in the Castlevania series.[failed verification][125] Other examples of such games include Hollow Knight, both games in the Ori series (Ori and the Blind Forest and Ori and the Will of the Wisps), Wonder Boy III: The Dragon's Trap, Tails Adventure, Cave Story, Mega Man ZX, Shadow Complex, DuckTales: Remastered).[126][127][128][129][130][131]

Early examples of free-roaming, side-scrolling, 2D platform-adventures in the vein of "Metroidvania" include Nintendo's Metroid in 1986 and Konami's Castlevania games: Vampire Killer in 1986[132][133][unreliable source?] and Simon's Quest in 1987,[134][135] The Goonies II in 1987 again by Konami,[136] as well as Enix's sci-fi Sharp X1 computer game Brain Breaker in 1985,[47][137] Pony Canyon's Super Pitfall in 1986,[48] System Sacom's Euphory in 1987,[47] Bothtec's The Scheme in 1988,[47] and several Dragon Slayer action RPGs by Nihon Falcom such as the 1985 release Xanadu[138][139] and 1987 releases Faxanadu[138] and Legacy of the Wizard.[140]

Auto-runner games

[edit]Auto-runner games are platformers where the player-character is nearly always moving in one constant direction through the level, with less focus on tricky jumping but more on quick reflexes as obstacles appear on screen. The subcategory of endless runner games have levels that effectively go on forever, typically through procedural generation. Auto-runner games have found success on mobile platforms, because they are well-suited to the small set of controls these games require, often limited to a single screen tap for jumping.

Game designer Scott Rogers named side-scrolling shooters like Scramble (1981) and Moon Patrol (1982) and chase-style gameplay in platformers like Disney's Aladdin (1994 8-bit version) and Crash Bandicoot (1996) as forerunners of the genre.[141] B.C.'s Quest for Tires (1983) has elements of runner games,[142] keeping the jumping of Moon Patrol, but replacing the vehicle with a cartoon character.

In February 2003, Gamevil published Nom for mobile phones in Korea. The game's designer Sin Bong-gu, stated that he wanted to create a game that was only possible on mobile phones, therefore he made the player character walk up walls and ceilings, requiring players to turn around their mobile phones while playing. To compensate for this complication, he limited the game's controls to a single button and let the character run automatically and indefinitely, "like the people in modern society, who must always look forward and keep running".[143]

While the concept thus was long known in Korea, journalists credit Canabalt (2009) as "the title that single-handedly invented the smartphone-friendly single-button running genre" and spawned a wave of clones.[142][144] Fotonica (2011), a one-button endless runner viewed from the first person, that was described as a "hybrid of Canabalt's running, Mirror's Edge's perspective (and hands) and Rez's visual style".[145]

Temple Run (2011) and its successor Temple Run 2 were popular endless running games. The latter became the world's fastest-spreading mobile game in January 2013, with 50 million installations within thirteen days.[146]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "What is a Platform Game? | 10 Design Types & Video Game Examples". iD Tech. Retrieved 2021-03-29.

- ^ This estimate is based on the number of platform games released on specific systems. For example, on the Master System, 113 of the 347 games (32.5 percent) listed on vgmuseum.com are platform games, and 264 of the 1044 Genesis games (25.2 percent) are platformers

- ^ a b c "A Detailed Cross-Examination of Yesterday and Today's Best-Selling Platform Games". Gamasutra. 2006-08-04. Archived from the original on 2007-10-27. Retrieved 2006-11-21.

- ^ a b c Bycer, Joshua (2019). Game Design Deep Dive: Platformers. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0429560576.

- ^ Paumgarten, Nick (December 13, 2010). "Master of Play". The New Yorker. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- ^ Yamashita, Akira (8 January 1989). "Shigeru Miyamoto Interview: The Culmination of The Athletic Game Genre". Micom BASIC (in Japanese) (1989–02).

- ^ Gifford, Kevin. "Super Mario Bros.' 25th: Miyamoto Reveals All". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on January 5, 2015. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ a b Altice, Nathan (2015). "Chapter 2: Ports". I Am Error: The Nintendo Family Computer / Entertainment System Platform. MIT Press. pp. 53–80. ISBN 9780262028776.

- ^ "Gorilla Keeps on Climbing! Kong". Computer and Video Games. No. 26 (December 1983). 16 November 1983. pp. 40–1.

- ^ a b Bloom, Steve (1982). Video Invaders. Arco Publishing. p. 29. ISBN 978-0668055208.

- ^ "The Player's Guide to Climbing Games". Electronic Games. 1 (11): 49. January 1983. Archived from the original on 2016-03-19. Retrieved 2015-03-19.

- ^ "Reviews Explained: The Game Categories". TV Gamer. London: 76. March 1983.

- ^ "Stocking Stuffers: Beer Run". Creative Computing. 8 (12): 62, 64. December 1982.

- ^ "Video Games Player 1983 Golden Joystick Awards". Video Games Player. Vol. 2, no. 1. United States: Carnegie Publications. September 1983. pp. 49–51.

- ^ Horowitz, Ken (21 October 2016). Playing at the Next Level: A History of American Sega Games. McFarland & Company. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-7864-9994-6.

- ^ Conference Proceedings: Conference, March 15–19 : Expo, March 16–18, San Jose, CA : the Game Development Platform for Real Life. The Conference. 1999. p. 299.

what do you get if you put Sonic the Hedgehog (or any other character action game for that matter) in 3D

- ^ "Now Playing". Nintendo Power. No. 50. July 1993. pp. 102–4.

- ^ "Viewpoint". GameFan. Vol. 1, no. 10. September 1993. pp. 14–5.

- ^ Kohler, Chris (2016). "Chapter 3: The Play Control of Power Fantasies: Nintendo, Super Mario, and Shigeru Miyamoto". Power-Up: How Japanese Video Games Gave the World an Extra Life, 2016 Edition. Brady Games. pp. 23–76. ISBN 9780744004243.

- ^ "Complete Games Guide" (PDF). Computer and Video Games (Complete Guide to Consoles): 46–77. 16 October 1989. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 January 2021.

- ^ "Capcom: A Captive Audience". The Games Machine. No. 19 (June 1989). United Kingdom: Newsfield. 18 May 1989. pp. 24–5.

- ^ Crawford, Chris (2003). Chris Crawford on Game Design. New Riders. ISBN 0-88134-117-7.

- ^ Crazy Climber at the Killer List of Videogames

- ^ "Hard Hat - Mattel Intellivision - Games Database".

- ^ "Donkey Kong". Arcade History. 2006-11-21. Archived from the original on 2007-10-20. Retrieved 2006-11-21.

- ^ "Gaming's most important evolutions". GamesRadar. October 8, 2010. p. 3. Archived from the original on March 19, 2012. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ "ColecoVision FAQ". Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2018-06-11.

- ^ "Coleco Donkey Kong". Handheld Museum. Archived from the original on 2018-01-05. Retrieved 2018-06-11.

- ^ Harris, Blake J. (2014-05-14). "The Rise of Nintendo: A Story in 8 Bits". Grantland. Retrieved 2021-03-29.

- ^ Readers' Awards, Crash, 1984–1985, archived from the original on 18 April 2012, retrieved 13 May 2012

- ^ a b "The Leif Ericson Awards". IGN. 2008-03-24. Archived from the original on 2012-03-09. Retrieved 2013-01-10.

- ^ "ジャンプバグ レトロゲームしま専科". Archived from the original on 2008-04-12. Retrieved 2008-06-18.

- ^ "Jump Bug". Arcade History. Archived from the original on 2012-10-07. Retrieved 2006-11-21.

- ^ Lendino, Jamie (27 September 2020). Attract Mode: The Rise and Fall of Coin-Op Arcade Games. Steel Gear Press. pp. 222–3.

- ^ Lendino, Jamie (27 September 2020). Attract Mode: The Rise and Fall of Coin-Op Arcade Games. Steel Gear Press. p. 222.

- ^ "Reviews: Track Attack". ROM (1): 23. September 1983.

- ^ "BC's Quest for Tires". MobyGames. Archived from the original on 2007-10-15. Retrieved 2007-02-08.

- ^ "Snokie". Atari Mania. Archived from the original on 2018-06-12. Retrieved 2018-06-11.

- ^ "Pac-Land". Arcade History. Archived from the original on 2018-06-03. Retrieved 2018-06-11.

- ^ Szczepaniak, John (4 November 2015). The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers Vol. 2 (1 ed.). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. pp. 207–208. ISBN 978-1518655319. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- ^ HSals (22 May 2015). "EXCLUSIVE: Interview with Toru Iwatani, creator of Pac-Man". GeekCulture. Archived from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ Bevan, Mike (22 March 2014). "The Ultimate Guide to Pac-Land". No. 127. Retro Gamer. pp. 67–72. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ Kurt Kalata, Alex Kidd Archived 2016-01-18 at the Wayback Machine, Hardcore Gaming 101

- ^ a b The Legend of Wonder Boy Archived 2011-07-13 at the Wayback Machine, IGN, November 14, 2008

- ^ "Hardcore Gaming 101: Wonderboy". Hardcore Gaming 101. Archived from the original on 2010-01-07. Retrieved 2010-02-04.

- ^ "Major Havoc". Killer List of Videogames. Archived from the original on 2006-03-07. Retrieved 2006-11-21.

- ^ a b c d John Szczepaniak. "Retro Japanese Computers: Gaming's Final Frontier". Hardcore Gaming 101. p. 4. Archived from the original on 2011-01-13. Retrieved 2011-03-16. Reprinted from "Retro Japanese Computers: Gaming's Final Frontier". Retro Gamer (67). 2009.

- ^ a b "Gamasutra - Gems In The Rough: Yesterday's Concepts Mined For Today". www.gamasutra.com. Archived from the original on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ Column: 'Might Have Been' - Telenet Japan Archived 2011-07-11 at the Wayback Machine, GameSetWatch, December 17, 2007

- ^ "Gaming's most important evolutions". GamesRadar. October 8, 2010. Retrieved 2011-01-09.

- ^ a b "Playing With Power: Great Ideas That Have Changed Gaming Forever from 1UP.com". 17 June 2006. Archived from the original on 17 June 2006. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ Capcom. Strider 2 (PlayStation). Level/area: Instruction manual, page 18.

- ^ Shadow Dancer at the Killer List of Videogames

- ^ "Series Guide". Bonk Compendium. Archived from the original on 2007-01-25. Retrieved 2007-01-27.

- ^ a b Horowitz, Ken (2005-06-22). "History of: The Sonic The Hedgehog Series". Sega-16. Archived from the original on January 14, 2010. Retrieved 2010-11-14.

- ^ "Overview". Sonic Cult. Archived from the original on 2016-03-11. Retrieved 2007-01-27.

- ^ Lee, Dave. "Twenty years of Sonic the Hedgehog". BBC News. Archived from the original on 11 January 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ Boutros, Daniel (August 4, 2006). "A Detailed Cross-Examination of Yesterday and Today's Best-Selling Platform Games". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on October 27, 2007. Retrieved November 21, 2006.

- ^ "Amiga 600 Technical Specifications". Amiga History. December 15, 2002. Retrieved 2006-11-21.

- ^ Edwards, Benj (January 22, 2012). "The 12 Greatest PC Shareware Games of All-Time". PC World. Archived from the original on October 4, 2018. Retrieved September 17, 2018.

- ^ "A Look Back at Commander Keen". 3DRealms.com. Archived from the original on 2016-04-02. Retrieved 2006-11-21.

- ^ "It's a Viewtiful Day". Gamasutra. 2004-08-24. Archived from the original on 2007-10-27. Retrieved 2007-01-23.

- ^ "Yoshi's Story Reviews". GameRankings. Archived from the original on 2009-04-02. Retrieved 2006-11-21.

- ^ "Mischief Makers Reviews". GameRankings. Archived from the original on 2009-03-19. Retrieved 2006-11-21.

- ^ "US Platinum Game Chart". The Magic Box. Archived from the original on 2007-04-21. Retrieved 2007-01-23.

- ^ Johnston, Chris (1997-11-06). "N64 Back on Top". SF Kosmo (archived from GameSpot). Archived from the original on 2009-01-01. Retrieved 2007-01-23.

- ^ Johnston, Chris (1997-10-02). "Sony Closes the Gap". SF Kosmo (archived from GameSpot). Archived from the original on 2011-05-25. Retrieved 2007-01-23.

- ^ a b c Antarctic Adventure at the Killer List of Videogames

- ^ a b "Antarctic Adventure". AllGame. Archived from the original on 2014-01-01.

- ^ a b c Antarctic Adventure at MobyGames

- ^ "KONAMIのMSX往年の名作がWiiバーチャルコンソールに登場、第2弾として『メタルギア』の配信も決定 - ファミ通.com". www.famitsu.com. Archived from the original on 30 October 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ Penguin Adventure at MobyGames

- ^ Penguin Adventure, GameSpot

- ^ a b "Hironobu Sakaguchi: The Man Behind the Fantasies". Next Generation Magazine, vol 50.

- ^ a b "3-D WorldRunner". AllGame. Archived from the original on 2014-01-01.

- ^ "JJ: Tobidase Daisakusen Part II". AllGame. Archived from the original on 2014-01-01.

- ^ de Dinechin, Christophe (2007-11-08). "The dawn of 3D games". Grenouille Bouillie. Archived from the original on 2011-02-28. Retrieved 2007-11-08.

- ^ Fahs, Travis (2007-01-08). "Before Their Time: Cover Art". GotNext. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-01-08.

- ^ "Fade to Black - DOS Cover Art". MobyGames. Archived from the original on 2007-10-15. Retrieved 2007-01-28.

- ^ "Geograph Seal". Archived from the original on 2006-12-10. Retrieved 2006-12-29.

- ^ a b Travis Fahs, Geograph Seal (X68000) Archived 2016-01-29 at the Wayback Machine, The Next Level, November 25, 2006

- ^ "Forgotten Gem: Jumping Flash". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2006-11-21.

- ^ Fahey, Rob (9 June 2007). "Jumping Flash (1995)". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- ^ "First platform videogame in true 3D". guinnessworldrecords.com. Archived from the original on 11 December 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ John Szczepaniak, Floating Runner: Quest for the 7 Crystals (フローティングランナー 7つの水晶の物語) - PlayStation (1996) Archived 2016-09-15 at the Wayback Machine, Hardcore Gaming 101 (September 26, 2011)

- ^ "Super Mario 64 Overview". Polygon. 26 October 2012. Retrieved 2021-03-29.

- ^ Cozic, Laurent; et al. "Intuitive Interaction and Expressive Cinematography in Video Games". Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-20. Retrieved 2006-01-27.

- ^ "US Platinum Game Chart". Magic Box. Archived from the original on 2007-04-21. Retrieved 2006-01-24.

- ^ "Sega of Japans Comments on Dreamcast Discontinuance". IGN. 2001-01-31. Archived from the original on 2007-10-19. Retrieved 2007-02-08.

- ^ "Rayman 2: The Great Escape Reviews". Game Rankings. Archived from the original on 2009-03-12. Retrieved 2006-12-29.

- ^ "Rayman 3: Hoodlum Havoc Reviews". Game Rankings. Archived from the original on 2009-03-04. Retrieved 2006-12-29.

- ^ Avard, Alex (12 March 2021). ""We might have overachieved, to be honest": The making of Jak and Daxter: The Precursor Legacy". gamesradar. Retrieved 2021-03-29.

- ^ a b Henley, Stacey (December 16, 2020). "Blast from the past: How this generation enabled platformers to crash back into the mainstream". GamesRadar. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ Sinclair, Brendan (2005-12-20). "Bitter medicine: What does the game industry have against innovation?". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 2006-12-08. Retrieved 2006-11-21.

- ^ Life After Shelf Death Archived 2007-11-15 at the Wayback Machine, The Escapist, November 13, 2007

- ^ "Super Mario Galaxy (Wii: 2007): Reviews". Metacritic. CNET. Archived from the original on 2017-05-06. Retrieved 2007-11-09.

- ^ "Ratchet and Clank Future (PS3: 2007): Reviews". Metacritic. CNET. Archived from the original on 2012-08-27. Retrieved 2007-11-09.

- ^ "Super Mario Galaxy Reviews". GameRankings. CNET. Archived from the original on 2011-11-06. Retrieved 2007-11-09.

- ^ a b "Financial Results Briefing for Fiscal Year Ended March 2009" (PDF). Nintendo. 2009-05-08. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-06-29. Retrieved 2009-05-08.

- ^ Williams, M.H. (2011-12-08). "Trine Sells 1.1 Million Copies Ahead of Sequel Release". industrygamers.com. Archived from the original on 2012-01-09. Retrieved 2012-01-22.

- ^ Kain, Erik (September 24, 2017). "'Crash Bandicoot N Sane Trilogy' Has Sold Over 2.5 Million Copies On PS4". Forbes. Archived from the original on December 22, 2017. Retrieved December 18, 2017.

- ^ "Best Games of 2024". OpenCritic. Retrieved 2024-11-27.

- ^ "Rob's Retro Reviews: 17 Sub-Genres of Platformer Games | List". Archived from the original on 2019-01-09. Retrieved 2019-01-09.

- ^ a b Derboo, Sam (2015). "Doki Doki Penguin Land". Hard Core Gaming.

- ^ Top 100 SNES Games of All Time - IGN.com, retrieved 2020-10-31

- ^ "Review: Wario Land II (3DS eShop / Game Boy)". Nintendo Life. 2012-07-20. Retrieved 2020-10-31.

- ^ "Donkey Kong Game Ranking". Game Ranking. Archived from the original on 2019-12-09.

- ^ "And Yet It Moves". 2011-06-19. Archived from the original on 2011-06-19. Retrieved 2020-10-31.

- ^ Gad, Joshua (2020-01-11). "Valve's Elusive F-STOP". Medium. Retrieved 2020-10-31.

- ^ Keil, Alyssa (February 11, 2020). "A History of Run-and-Gun Shooters". Mega Cat Studios. Retrieved 2020-10-31.

- ^ "The Best Run And Gun Games of All Time". Ranker. Retrieved 2020-10-31.

- ^ a b Bexander, Cecilia (January 2014). "The Cinematic Platformer Art Guide" (PDF). The making of a strategy game art guide. Uppsala Universitet. p. 70. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 March 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ Therrien, Carl. "Visual Design in Video Games" (PDF). Video Game History: From Bouncing Blocks to a Global Industry. Greenwood Press. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 March 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ Lalone, Nicholas (2012). "DIFFERENCES IN DESIGN: VIDEO GAME DESIGN IN PRE AND POST 9/11 AMERICA" (Thesis). pp. 77–78. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 March 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ Rybicki, Joe (5 May 2008). "Prince of Persia Retrospective". GameTap. Turner Broadcasting System. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ Bevan, Mike (December 2013). "The History of... Impossible Mission". Retro Gamer. No. 122. Imagine Publishing. pp. 44–49.

- ^ "Arcade Flyers: Cover Art". arcadeflyers.com. Archived from the original on 2015-09-04. Retrieved 2007-01-18.

- ^ "Arcade Flyers Cover Art". arcadeflyers.com. Archived from the original on 2015-09-04. Retrieved 2007-01-18.

- ^ Scullion, Chris (2019-03-30). The NES Encyclopedia: Every Game Released for the Nintendo Entertainment System. Pen and Sword. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-5267-3780-9.

- ^ Electronic Games - Volume 01 Number 11 (1983-01)(Reese Communications)(US). January 1983.

- ^ "Congo Bongo (Registration Number PA0000184737)". United States Copyright Office. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ^ "Awesome Ants Leap to the Attack!". Computer and Video Games. No. 26 (December 1983). 16 November 1983. pp. 31, 33.

- ^ "Little Big Adventure – Hardcore Gaming 101". Retrieved 2023-02-07.

- ^ Fletcher, JC (August 20, 2009). "These Metroidvania games are neither Metroid nor Vania". Joystiq. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- ^ Matulef, Jeffery (2014-03-21). "Koji Igarashi says Castlevania: SotN was inspired by Zelda, not Metroid". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on 2014-03-22. Retrieved 2014-03-21.

- ^ Parish, Jeremy (2009-07-23). "Metroidvania: Rekindling a Love Affair with the Old and the New". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on 2011-06-05. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- ^ Alexander, Leigh (2009-07-09). "Microsoft Confirms 'Summer Of Arcade' XBLA Line-Up". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on 2009-07-12. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- ^ Cook, Jim (2009-07-14). "Castlevania: Symphony of the Night (XBLA)". Gamers Daily News. Archived from the original on 2009-07-17. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- ^ Parish, Jeremy. "Metroidvania". Game Sprite. Archived from the original on 2016-06-27. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- ^ Caoili, Eric (2009-05-01). "Commodore Castleroid: Knight 'n' Grail". Game Set Watch. Archived from the original on 2009-05-15. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- ^ Bailey, Kat (2020-02-26). "Ori and the Will of the Wisps is "Three Times the Scope and Scale" of Blind Forest". USgamer. Retrieved 2020-06-19.

- ^ Parish, Jeremy (August 1, 2008). "Famicom 25th, Part 17: Live from The Nippon edition". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on June 29, 2012. Retrieved July 2, 2024.

- ^ Kurt Kalata and William Cain, Castlevania 2: Simon's Quest (1988) Archived 2011-07-23 at the Wayback Machine, Castlevania Dungeon, accessed 2011-02-27

- ^ Jeremy Parish, Metroidvania Chronicles II: Simon's Quest Archived 2011-06-29 at the Wayback Machine 1UP.com, June 28, 2006

- ^ Mike Whalen, Giancarlo Varanini. "The History of Castlevania - Castlevania II: Simon's Quest". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 2008-07-25. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ^ Parish, Jeremy. "Metroidvania Chronicles IV: The Goonies II". Telebunny. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ "Brain Breaker". hardcoregaming101.net. 6 October 2017. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ a b Jeremy Parish. "Metroidvania". Metroidvania.com. GameSpite.net. Archived from the original on 2016-06-27. Retrieved 2011-03-25.

- ^ Jeremy Parish (August 18, 2009). "8-Bit Cafe: The Shadow Complex Origin Story". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on June 20, 2012. Retrieved 2011-03-25.

- ^ Harris, John (September 26, 2007). "Game Design Essentials: 20 Open World Games". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on June 24, 2008. Retrieved July 25, 2008.

- ^ Swipe This!: The Guide to Great Touchscreen Game Design by Scott Rogers, Wiley and Sons, 2012

- ^ a b Parkin, Simon (June 7, 2013). "DON'T STOP: THE GAME THAT CONQUERED SMARTPHONES". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on December 17, 2016. Retrieved December 17, 2016.

- ^ Han, Ji-suk (May 28, 2004). "[Geim Keurieiteo] Geimbil 'Nom' gihoek Sin Bong-gu siljang" [게임 크리에이터] 게임빌 `놈` 기획 신봉구 실장 [[Game Creator] Director Sin Bong-Gu, planner of Gamevil's `Nom`]. DigitalTimes (in Korean). Archived from the original on July 9, 2016. Retrieved July 9, 2016.

- ^ Faraday, Owen (21 January 2013). "Temple Run 2 review". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on 2 February 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ nofi (January 19, 2011). "Fotonica: You Need This Game Now". The Sixth Axis. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved May 25, 2016.

- ^ Purchese, Robert (February 1, 2013). "Temple Run 2 is the fastest-spreading mobile game ever". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on February 4, 2013. Retrieved February 1, 2013.