Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Radar

View on Wikipedia

Radar is a system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (ranging), direction (azimuth and elevation angles), and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It is a radiodetermination method[1] used to detect and track aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, weather formations and terrain. The term RADAR was coined in 1940 by the United States Navy as an acronym for "radio detection and ranging".[2][3][4][5][6] The term radar has since entered English and other languages as an anacronym, a common noun, losing all capitalization.

A radar system consists of a transmitter producing electromagnetic waves in the radio or microwave domain, a transmitting antenna, a receiving antenna (often the same antenna is used for transmitting and receiving) and a receiver and processor to determine properties of the objects. Radio waves (pulsed or continuous) from the transmitter reflect off the objects and return to the receiver, giving information about the objects' locations and speeds. This device was developed secretly for military use by several countries in the period before and during World War II. A key development was the cavity magnetron in the United Kingdom, which allowed the creation of relatively small systems with sub-meter resolution.

The modern uses of radar are highly diverse, including air and terrestrial traffic control, radar astronomy, air-defense systems, anti-missile systems, marine radars to locate landmarks and other ships, aircraft anti-collision systems, ocean surveillance systems, outer space surveillance and rendezvous systems, meteorological precipitation monitoring, radar remote sensing, altimetry and flight control systems, guided missile target locating systems, self-driving cars, and ground-penetrating radar for geological observations. Modern high tech radar systems use digital signal processing and machine learning and are capable of extracting useful information from very high noise levels.

Other systems which are similar to radar make use of other regions of the electromagnetic spectrum. One example is lidar, which uses predominantly infrared light from lasers rather than radio waves. With the emergence of driverless vehicles, radar is expected to assist the automated platform to monitor its environment, thus preventing unwanted incidents.[7]

History

[edit]First experiments

[edit]As early as 1886, German physicist Heinrich Hertz showed that radio waves could be reflected from solid objects. In 1895, Alexander Popov, a physics instructor at the Imperial Russian Navy school in Kronstadt, developed an apparatus using a coherer tube for detecting distant lightning strikes. The next year, he added a spark-gap transmitter. In 1897, while testing this equipment for communicating between two ships in the Baltic Sea, he took note of an interference beat caused by the passage of a third vessel. In his report, Popov wrote that this phenomenon might be used for detecting objects, but he did nothing more with this observation.[8]

The German inventor Christian Hülsmeyer was the first to use radio waves to detect "the presence of distant metallic objects". In 1904, he demonstrated the feasibility of detecting a ship in dense fog, but not its distance from the transmitter.[9] He obtained a patent[10] for his detection device in April 1904 and later a patent[11] for a related amendment for estimating the distance to the ship. He also obtained a British patent on 23 September 1904[12] for a full radar system, that he called a telemobiloscope. It operated on a 50 cm wavelength and the pulsed radar signal was created via a spark-gap. His system already used the classic antenna setup of horn antenna with parabolic reflector and was presented to German military officials in practical tests in Cologne and Rotterdam harbour but was rejected.[13]

In 1915, Robert Watson-Watt used radio technology to provide advance warning of thunderstorms to airmen[14][15] and during the 1920s went on to lead the U.K. research establishment to make many advances using radio techniques, including the probing of the ionosphere and the detection of lightning at long distances. Through his lightning experiments, Watson-Watt became an expert on the use of radio direction finding before turning his inquiry to shortwave transmission. Requiring a suitable receiver for such studies, he told the "new boy" Arnold Frederic Wilkins to conduct an extensive review of available shortwave units. Wilkins would select a General Post Office model after noting its manual's description of a "fading" effect (the common term for interference at the time) when aircraft flew overhead.

By placing a transmitter and receiver on opposite sides of the Potomac River in 1922, U.S. Navy researchers A. Hoyt Taylor and Leo C. Young discovered that ships passing through the beam path caused the received signal to fade in and out. Taylor submitted a report, suggesting that this phenomenon might be used to detect the presence of ships in low visibility, but the Navy did not immediately continue the work. Eight years later, Lawrence A. Hyland at the Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) observed similar fading effects from passing aircraft; this revelation led to a patent application[16] as well as a proposal for further intensive research on radio-echo signals from moving targets to take place at NRL, where Taylor and Young were based at the time.[17]

Similarly, in the UK, L. S. Alder took out a secret provisional patent for Naval radar in 1928.[18] W.A.S. Butement and P. E. Pollard developed a breadboard test unit, operating at 50 cm (600 MHz) and using pulsed modulation which gave successful laboratory results. In January 1931, a writeup on the apparatus was entered in the Inventions Book maintained by the Royal Engineers. This is the first official record in Great Britain of the technology that was used in coastal defence and was incorporated into Chain Home as Chain Home (low).[19][20]

Before World War II

[edit]

Before World War II, researchers in the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands,[21] the Soviet Union, and the United States, independently and in great secrecy, developed technologies that led to the modern version of radar. Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and South Africa followed prewar Great Britain's radar development, while Hungary and Sweden generated their radar technology during the war.[citation needed]

In France in 1934, following systematic studies on the split-anode magnetron, the research branch of the Compagnie générale de la télégraphie sans fil (CSF) headed by Maurice Ponte with Henri Gutton, Sylvain Berline and M. Hugon, began developing an obstacle-locating radio apparatus, aspects of which were installed on the ocean liner Normandie in 1935.[22][23]

During the same period, Soviet military engineer P.K. Oshchepkov, in collaboration with the Leningrad Electrotechnical Institute, produced an experimental apparatus, RAPID, capable of detecting an aircraft within 3 km of a receiver.[24] The Soviets produced their first mass production radars RUS-1 and RUS-2 Redut in 1939 but further development was slowed following the arrest of Oshchepkov and his subsequent gulag sentence. In total, only 607 Redut stations were produced during the war. The first Russian airborne radar, Gneiss-2, entered into service in June 1943 on Pe-2 dive bombers. More than 230 Gneiss-2 stations were produced by the end of 1944.[25] The French and Soviet systems, however, featured continuous-wave operation that did not provide the full performance ultimately synonymous with modern radar systems.

Full radar evolved as a pulsed system, and the first such elementary apparatus was demonstrated in December 1934 by the American Robert M. Page, working at the Naval Research Laboratory.[26] The following year, the United States Army successfully tested a primitive surface-to-surface radar to aim coastal battery searchlights at night.[27] This design was followed by a pulsed system demonstrated in May 1935 by Rudolf Kühnhold and the firm GEMA in Germany and then another in June 1935 by an Air Ministry team led by Robert Watson-Watt in Great Britain.

In 1935, Watson-Watt was asked to judge recent reports of a German radio-based death ray and turned the request over to Wilkins. Wilkins returned a set of calculations demonstrating the system was basically impossible. When Watson-Watt then asked what such a system might do, Wilkins recalled the earlier report about aircraft causing radio interference. This revelation led to the Daventry Experiment of 26 February 1935, using a powerful BBC shortwave transmitter as the source and their GPO receiver setup in a field while a bomber flew around the site. When the plane was clearly detected, Hugh Dowding, the Air Member for Supply and Research, was very impressed with their system's potential and funds were immediately provided for further operational development.[28] Watson-Watt's team patented the device in patent GB593017.[29][30][31]

Development of radar greatly expanded on 1 September 1936, when Watson-Watt became superintendent of a new establishment under the British Air Ministry, Bawdsey Research Station located in Bawdsey Manor, near Felixstowe, Suffolk. Work there resulted in the design and installation of aircraft detection and tracking stations called "Chain Home" along the East and South coasts of England in time for the outbreak of World War II in 1939. This system provided the vital advance information that helped the Royal Air Force win the Battle of Britain; without it, significant numbers of fighter aircraft, which Great Britain did not have available, would always have needed to be in the air to respond quickly. The radar formed part of the "Dowding system" for collecting reports of enemy aircraft and coordinating the response.

Given all required funding and development support, the team produced working radar systems in 1935 and began deployment. By 1936, the first five Chain Home (CH) systems were operational and by 1940 stretched across the entire UK including Northern Ireland. Even by standards of the era, CH was crude; instead of broadcasting and receiving from an aimed antenna, CH broadcast a signal floodlighting the entire area in front of it, and then used one of Watson-Watt's own radio direction finders to determine the direction of the returned echoes. This fact meant CH transmitters had to be much more powerful and have better antennas than competing systems but allowed its rapid introduction using existing technologies.

During World War II

[edit]

A key development was the cavity magnetron in the UK, which allowed the creation of relatively small systems with sub-meter resolution. Britain shared the technology with the U.S. during the 1940 Tizard Mission.[32][33]

In April 1940, Popular Science showed an example of a radar unit using the Watson-Watt patent in an article on air defence.[34] Also, in late 1941 Popular Mechanics had an article in which a U.S. scientist speculated about the British early warning system on the English east coast and came close to what it was and how it worked.[35] Watson-Watt was sent to the U.S. in 1941 to advise on air defense after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor.[36] Alfred Lee Loomis organized the secret MIT Radiation Laboratory at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts which developed microwave radar technology in the years 1941–45. Later, in 1943, Page greatly improved radar with the monopulse technique that was used for many years in most radar applications.[37]

The war precipitated research to find better resolution, more portability, and more features for radar, including small, lightweight sets to equip night fighters (aircraft interception radar) and maritime patrol aircraft (air-to-surface-vessel radar), and complementary navigation systems like Oboe used by the RAF's Pathfinder.

Applications

[edit]

The information provided by radar includes the bearing and range (and therefore position) of the object from the radar scanner. It is thus used in many different fields where the need for such positioning is crucial. The first use of radar was for military purposes: to locate air, ground and sea targets. This evolved in the civilian field into applications for aircraft, ships, and automobiles.[38][39]

In aviation, aircraft can be equipped with radar devices that warn of aircraft or other obstacles in or approaching their path, display weather information, and give accurate altitude readings. The first commercial device fitted to aircraft was a 1938 Bell Lab unit on some United Air Lines aircraft.[35] Aircraft can land in fog at airports equipped with radar-assisted ground-controlled approach systems in which the plane's position is observed on precision approach radar screens by operators who thereby give radio landing instructions to the pilot, maintaining the aircraft on a defined approach path to the runway. Military fighter aircraft are usually fitted with air-to-air targeting radars, to detect and target enemy aircraft. In addition, larger specialized military aircraft carry powerful airborne radars to observe air traffic over a wide region and direct fighter aircraft towards targets.[40]

Marine radars are used to measure the bearing and distance of ships to prevent collision with other ships, to navigate, and to fix their position at sea when within range of shore or other fixed references such as islands, buoys, and lightships. In port or in harbour, vessel traffic service radar systems are used to monitor and regulate ship movements in busy waters.[41]

Meteorologists use radar to monitor precipitation and wind. It has become the primary tool for short-term weather forecasting and watching for severe weather such as thunderstorms, tornadoes, winter storms, precipitation types, etc. Geologists use specialized ground-penetrating radars to map the composition of Earth's crust. Police forces use radar guns to monitor vehicle speeds on the roads. Automotive radars are used for adaptive cruise control and emergency braking on vehicles by ignoring stationary roadside objects that could cause incorrect brake application and instead measuring moving objects to prevent collision with other vehicles. As part of Intelligent Transport Systems, fixed-position stopped vehicle detection (SVD) radars are mounted on the roadside to detect stranded vehicles, obstructions and debris by inverting the automotive radar approach and ignoring moving objects.[42] Smaller radar systems are used to detect human movement. Examples are breathing pattern detection for sleep monitoring[43] and hand and finger gesture detection for computer interaction.[44] Automatic door opening, light activation and intruder sensing are also common.

Principles

[edit]Radar signal

[edit]

A radar system has a transmitter that emits radio waves known as radar signals in predetermined directions. When these signals contact an object they are usually reflected or scattered in many directions, although some of them will be absorbed and penetrate into the target.[45] Radar signals are reflected especially well by materials of considerable electrical conductivity—such as most metals, seawater, and wet ground. This makes the use of radar altimeters possible in certain cases. The radar signals that are reflected back towards the radar receiver are the desirable ones that make radar detection work. If the object is moving either toward or away from the transmitter, there will be a slight change in the frequency of the radio waves due to the Doppler effect.

Radar receivers are usually, but not always, in the same location as the transmitter. The reflected radar signals captured by the receiving antenna are usually very weak. They can be strengthened by electronic amplifiers. More sophisticated methods of signal processing are also used in order to recover useful radar signals.

The weak absorption of radio waves by the medium through which they pass is what enables radar sets to detect objects at relatively long ranges—ranges at which other electromagnetic wavelengths, such as visible light, infrared light, and ultraviolet light, are too strongly attenuated. Weather phenomena, such as fog, clouds, rain, falling snow, and sleet, that block visible light are usually transparent to radio waves. Certain radio frequencies that are absorbed or scattered by water vapour, raindrops, or atmospheric gases (especially oxygen) are avoided when designing radars, except when their detection is intended.

Illumination

[edit]Radar relies on its own transmissions rather than light from the Sun or the Moon, or from electromagnetic waves emitted by the target objects themselves, such as infrared radiation (heat). This process of directing artificial radio waves towards objects is called illumination, although radio waves are invisible to the human eye as well as optical cameras.

Reflection

[edit]

If electromagnetic waves travelling through one material meet another material, having a different dielectric constant or diamagnetic constant from the first, the waves will reflect or scatter from the boundary between the materials. This means that a solid object in air or in a vacuum, or a significant change in atomic density between the object and what is surrounding it, will usually scatter radar (radio) waves from its surface. This is particularly true for electrically conductive materials such as metal and carbon fibre, making radar well-suited to the detection of aircraft and ships. Radar absorbing material, containing resistive and sometimes magnetic substances, is used on military vehicles to reduce radar reflection. This is the radio equivalent of painting something a dark colour so that it cannot be seen by the eye at night.

Radar waves scatter in a variety of ways depending on the size (wavelength) of the radio wave and the shape of the target. If the wavelength is much shorter than the target's size, the wave will bounce off in a way similar to the way light is reflected by a mirror. If the wavelength is much longer than the size of the target, the target may not be visible because of poor reflection. Low-frequency radar technology is dependent on resonances for detection, but not identification, of targets. This is described by Rayleigh scattering, an effect that creates Earth's blue sky and red sunsets. When the two length scales are comparable, there may be resonances. Early radars used very long wavelengths that were larger than the targets and thus received a vague signal, whereas many modern systems use shorter wavelengths (a few centimetres or less) that can image objects as small as a loaf of bread.

Short radio waves reflect from curves and corners in a way similar to glint from a rounded piece of glass. The most reflective targets for short wavelengths have 90° angles between the reflective surfaces. A corner reflector consists of three flat surfaces meeting like the inside corner of a cube. The structure will reflect waves entering its opening directly back to the source. They are commonly used as radar reflectors to make otherwise difficult-to-detect objects easier to detect. Corner reflectors on boats, for example, make them more detectable to avoid collision or during a rescue. For similar reasons, objects intended to avoid detection will not have inside corners or surfaces and edges perpendicular to likely detection directions, which leads to "odd" looking stealth aircraft. These precautions do not totally eliminate reflection because of diffraction, especially at longer wavelengths. Half wavelength long wires or strips of conducting material, such as chaff, are very reflective but do not direct the scattered energy back toward the source. The extent to which an object reflects or scatters radio waves is called its radar cross-section.

Radar range equation

[edit]The power Pr returning to the receiving antenna is given by the equation:

where

- Pt = transmitter power

- Gt = gain of the transmitting antenna

- Ar = effective aperture (area) of the receiving antenna; this can also be expressed as , where

- = transmitted wavelength

- Gr = gain of receiving antenna[45]: 4–6

- σ = radar cross section, or scattering coefficient, of the target

- F = pattern propagation factor

- Rt = distance from the transmitter to the target

- Rr = distance from the target to the receiver.

In the common case where the transmitter and the receiver are at the same location, Rt = Rr and the term Rt² Rr² can be replaced by R4, where R is the range. This yields:

This shows that the received power declines as the fourth power of the range, which means that the received power from distant targets is relatively very small.

Additional filtering and pulse integration modifies the radar equation slightly for pulse-Doppler radar performance, which can be used to increase detection range and reduce transmit power.

The equation above with F = 1 is a simplification for transmission in a vacuum without interference. The propagation factor accounts for the effects of multipath and shadowing and depends on the details of the environment. In a real-world situation, pathloss effects are also considered.

Doppler effect

[edit]

Frequency shift is caused by motion that changes the number of wavelengths between the reflector and the radar. This can degrade or enhance radar performance depending upon how it affects the detection process. As an example, moving target indication can interact with Doppler to produce signal cancellation at certain radial velocities, which degrades performance.[45]: 10–11

Sea-based radar systems, semi-active radar homing, active radar homing, weather radar, military aircraft, and radar astronomy rely on the Doppler effect to enhance performance. This produces information about target velocity during the detection process. This also allows small objects to be detected in an environment containing much larger nearby slow moving objects.

Doppler shift depends upon whether the radar configuration is active or passive. Active radar transmits a signal that is reflected back to the receiver. Passive radar depends upon the object sending a signal to the receiver.

The Doppler frequency shift for active radar is as follows, where is Doppler frequency, is transmit frequency, is radial velocity, and is the speed of light:[46]

- .

Passive radar is applicable to electronic countermeasures and radio astronomy as follows:

- .

Only the radial component of the velocity is relevant. When the reflector is moving at right angle to the radar beam, it has no relative velocity. Objects moving parallel to the radar beam produce the maximum Doppler frequency shift.

When the transmit frequency () is pulsed, using a pulse repeat frequency of , the resulting frequency spectrum will contain harmonic frequencies above and below with a distance of . As a result, the Doppler measurement is only non-ambiguous if the Doppler frequency shift is less than half of , called the Nyquist frequency, since the returned frequency otherwise cannot be distinguished from shifting of a harmonic frequency above or below, thus requiring:

Or when substituting with :

As an example, a Doppler weather radar with a pulse rate of 2 kHz and transmit frequency of 1 GHz can reliably measure weather speed up to at most 150 m/s (340 mph), thus cannot reliably determine radial velocity of aircraft moving 1,000 m/s (2,200 mph).

Polarization

[edit]In all electromagnetic radiation, the electric field is perpendicular to the direction of propagation, and the electric field direction is the polarization of the wave. For a transmitted radar signal, the polarization can be controlled to yield different effects. Radars use horizontal, vertical, linear, and circular polarization to detect different types of reflections. For example, circular polarization is used to minimize the interference caused by rain. Linear polarization returns usually indicate metal surfaces. Random polarization returns usually indicate a fractal surface, such as rocks or soil, and are used by navigation radars.

Limiting factors

[edit]Beam path and range

[edit]

Where :

r : distance radar-target

ke : 4/3

ae : Earth radius

θe : elevation angle above the radar horizon

ha : height of the feedhorn above ground

A radar beam follows a linear path in vacuum but follows a somewhat curved path in atmosphere due to variation in the refractive index of air, which is called the radar horizon. Even when the beam is emitted parallel to the ground, the beam rises above the ground as the curvature of the Earth sinks below the horizon. Furthermore, the signal is attenuated by the medium the beam crosses, and the beam disperses.

The maximum range of conventional radar can be limited by a number of factors:

- Line of sight, which depends on the height above the ground. Without a direct line of sight, the path of the beam is blocked.

- The maximum non-ambiguous range, which is determined by the pulse repetition frequency. The maximum non-ambiguous range is the distance the pulse can travel to and return from before the next pulse is emitted.

- Radar sensitivity and the power of the return signal as computed in the radar equation. This component includes factors such as the environmental conditions and the size (or radar cross section) of the target.

Noise

[edit]Signal noise is an internal source of random variations in the signal, which is generated by all electronic components.

Reflected signals decline rapidly as distance increases, so noise introduces a radar range limitation. The noise floor and signal-to-noise ratio are two different measures of performance that affect range performance. Reflectors that are too far away produce too little signal to exceed the noise floor and cannot be detected. Detection requires a signal that exceeds the noise floor by at least the signal-to-noise ratio.

Noise typically appears as random variations superimposed on the desired echo signal received in the radar receiver. The lower the power of the desired signal, the more difficult it is to discern it from the noise. The noise figure is a measure of the noise produced by a receiver compared to an ideal receiver, and this needs to be minimized.

Shot noise is produced by electrons in transit across a discontinuity, which occurs in all detectors. Shot noise is the dominant source in most receivers. There will also be flicker noise caused by electron transit through amplification devices, which is reduced using heterodyne amplification. Another reason for heterodyne processing is that for fixed fractional bandwidth, the instantaneous bandwidth increases linearly in frequency. This allows improved range resolution. The one notable exception to heterodyne (downconversion) radar systems is ultra-wideband radar. Here a single cycle, or transient wave, is used similar to UWB communications, see List of UWB channels.

Noise is also generated by external sources, most importantly the natural thermal radiation of the background surrounding the target of interest. In modern radar systems, the internal noise is typically about equal to or lower than the external noise. An exception is if the radar is aimed upwards at clear sky, where the scene is so "cold" that it generates very little thermal noise. The thermal noise is given by kB T B, where T is temperature, B is bandwidth (post matched filter) and kB is the Boltzmann constant. There is an appealing intuitive interpretation of this relationship in a radar. Matched filtering allows the entire energy received from a target to be compressed into a single bin (be it a range, Doppler, elevation, or azimuth bin). On the surface it appears that then within a fixed interval of time, perfect, error free, detection could be obtained. This is done by compressing all energy into an infinitesimal time slice. What limits this approach in the real world is that, while time is arbitrarily divisible, current is not. The quantum of electrical energy is an electron, and so the best that can be done is to match filter all energy into a single electron. Since the electron is moving at a certain temperature (Planck spectrum) this noise source cannot be further eroded. Ultimately, radar, like all macro-scale entities, is profoundly impacted by quantum theory.

Noise is random and target signals are not. Signal processing can take advantage of this phenomenon to reduce the noise floor using two strategies. The kind of signal integration used with moving target indication can improve noise up to for each stage. The signal can also be split among multiple filters for pulse-Doppler signal processing, which reduces the noise floor by the number of filters. These improvements depend upon coherence.

Interference

[edit]Radar systems must overcome unwanted signals in order to focus on the targets of interest. These unwanted signals may originate from internal and external sources, both passive and active. The ability of the radar system to overcome these unwanted signals defines its signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). SNR is defined as the ratio of the signal power to the noise power within the desired signal; it compares the level of a desired target signal to the level of background noise (atmospheric noise and noise generated within the receiver). The higher a system's SNR the better it is at discriminating actual targets from noise signals.

Clutter

[edit]

Clutter refers to radio frequency (RF) echoes returned from targets which are uninteresting to radar operators. Such targets include man-made objects such as buildings and — intentionally — by radar countermeasures such as chaff. Such targets also include natural objects such as ground, sea, and — when not being tasked for meteorological purposes — precipitation, hail spike, dust storms, animals (especially birds), turbulence in the atmospheric circulation, and meteor trails. Radar clutter can also be caused by other atmospheric phenomena, such as disturbances in the ionosphere caused by geomagnetic storms or other space weather events. This phenomenon is especially apparent near the geomagnetic poles, where the action of the solar wind on the earth's magnetosphere produces convection patterns in the ionospheric plasma.[47] Radar clutter can degrade the ability of over-the-horizon radar to detect targets.[47][48]

Some clutter may also be caused by a long radar waveguide between the radar transceiver and the antenna. In a typical plan position indicator (PPI) radar with a rotating antenna, this will usually be seen as a "sun" or "sunburst" in the center of the display as the receiver responds to echoes from dust particles and misguided RF in the waveguide. Adjusting the timing between when the transmitter sends a pulse and when the receiver stage is enabled will generally reduce the sunburst without affecting the accuracy of the range since most sunburst is caused by a diffused transmit pulse reflected before it leaves the antenna. Clutter is considered a passive interference source since it only appears in response to radar signals sent by the radar.

Clutter is detected and neutralized in several ways. Clutter tends to appear static between radar scans; on subsequent scan echoes, desirable targets will appear to move, and all stationary echoes can be eliminated. Sea clutter can be reduced by using horizontal polarization, while rain is reduced with circular polarization (meteorological radars wish for the opposite effect, and therefore use linear polarization to detect precipitation). Other methods attempt to increase the signal-to-clutter ratio.

Clutter moves with the wind or is stationary. Two common strategies to improve measures of performance in a clutter environment are:

- Moving target indication, which integrates successive pulses

- Doppler processing, which uses filters to separate clutter from desirable signals

The most effective clutter reduction technique is pulse-Doppler radar. Doppler separates clutter from aircraft and spacecraft using a frequency spectrum, so individual signals can be separated from multiple reflectors located in the same volume using velocity differences. This requires a coherent transmitter. Another technique uses a moving target indicator that subtracts the received signal from two successive pulses using phase to reduce signals from slow-moving objects. This can be adapted for systems that lack a coherent transmitter, such as time-domain pulse-amplitude radar.

Constant false alarm rate, a form of automatic gain control (AGC), is a method that relies on clutter returns far outnumbering echoes from targets of interest. The receiver's gain is automatically adjusted to maintain a constant level of overall visible clutter. While this does not help detect targets masked by stronger surrounding clutter, it does help to distinguish strong target sources. In the past, radar AGC was electronically controlled and affected the gain of the entire radar receiver. As radars evolved, AGC became computer-software-controlled and affected the gain with greater granularity in specific detection cells.

Clutter may also originate from multipath echoes from valid targets caused by ground reflection, atmospheric ducting or ionospheric reflection/refraction (e.g., anomalous propagation). This clutter type is especially bothersome since it appears to move and behave like other normal (point) targets of interest. In a typical scenario, an aircraft echo is reflected from the ground below, appearing to the receiver as an identical target below the correct one. The radar may try to unify the targets, reporting the target at an incorrect height, or eliminating it on the basis of jitter or a physical impossibility. Terrain bounce jamming exploits this response by amplifying the radar signal and directing it downward.[49] These problems can be overcome by incorporating a ground map of the radar's surroundings and eliminating all echoes which appear to originate below ground or above a certain height. Monopulse can be improved by altering the elevation algorithm used at low elevation. In newer air traffic control radar equipment, algorithms are used to identify the false targets by comparing the current pulse returns to those adjacent, as well as calculating return improbabilities.

Jamming

[edit]Radar jamming refers to radio frequency signals originating from sources outside the radar, transmitting in the radar's frequency and thereby masking targets of interest. Jamming may be intentional, as with an electronic warfare tactic, or unintentional, as with friendly forces operating equipment that transmits using the same frequency range. Jamming is considered an active interference source, since it is initiated by elements outside the radar and in general unrelated to the radar signals.

Jamming is problematic to radar since the jamming signal only needs to travel one way (from the jammer to the radar receiver) whereas the radar echoes travel two ways (radar-target-radar) and are therefore significantly reduced in power by the time they return to the radar receiver in accordance with inverse-square law. Jammers therefore can be much less powerful than their jammed radars and still effectively mask targets along the line of sight from the jammer to the radar (mainlobe jamming). Jammers have an added effect of affecting radars along other lines of sight through the radar receiver's sidelobes (sidelobe jamming).

Mainlobe jamming can generally only be reduced by narrowing the mainlobe solid angle and cannot fully be eliminated when directly facing a jammer which uses the same frequency and polarization as the radar. Sidelobe jamming can be overcome by reducing receiving sidelobes in the radar antenna design and by using an omnidirectional antenna to detect and disregard non-mainlobe signals. Other anti-jamming techniques are frequency hopping and polarization.

Signal processing

[edit]Distance measurement

[edit]Transit time

[edit]

One way to obtain a distance measurement (ranging) is based on the time-of-flight: transmit a short pulse of radio signal (electromagnetic radiation) and measure the time it takes for the reflection to return. The distance is one-half the round trip time multiplied by the speed of the signal. The factor of one-half comes from the fact that the signal has to travel to the object and back again. Since radio waves travel at the speed of light, accurate distance measurement requires high-speed electronics. In most cases, the receiver does not detect the return while the signal is being transmitted.[45] Through the use of a duplexer, the radar switches between transmitting and receiving at a predetermined rate. A similar effect imposes a maximum range as well. In order to maximize range, longer times between pulses should be used, referred to as a pulse repetition time, or its reciprocal, pulse repetition frequency.

These two effects tend to be at odds with each other, and it is not easy to combine both good short range and good long range in a single radar. This is because the short pulses needed for a good minimum range broadcast have less total energy, making the returns much smaller and the target harder to detect. This could be offset by using more pulses, but this would shorten the maximum range. So each radar uses a particular type of signal. Long-range radars tend to use long pulses with long delays between them, and short range radars use smaller pulses with less time between them. As electronics have improved many radars now can change their pulse repetition frequency, thereby changing their range. The newest radars fire two pulses during one cell, one for short range (about 10 km (6.2 miles)) and a separate signal for longer ranges (about 100 km (62 miles)).

Distance may also be measured as a function of time. The radar mile is the time it takes for a radar pulse to travel one nautical mile, reflect off a target, and return to the radar antenna. Since a nautical mile is defined as 1,852 m, then dividing this distance by the speed of light (299,792,458 m/s), and then multiplying the result by 2 yields a result of 12.36 μs in duration.

Frequency modulation

[edit]

Another form of distance measuring radar is based on frequency modulation. In these systems, the frequency of the transmitted signal is changed over time. Since the signal takes a finite time to travel to and from the target, the received signal is a different frequency than what the transmitter is broadcasting at the time the reflected signal arrives back at the radar. By comparing the frequency of the two signals the difference can be easily measured.[45]: 7 This is easily accomplished with very high accuracy even in 1940s electronics. A further advantage is that the radar can operate effectively at relatively low frequencies. This was important in the early development of this type when high-frequency signal generation was difficult or expensive.

This technique can be used in continuous wave radar and is often found in aircraft radar altimeters. In these systems a "carrier" radar signal is frequency modulated in a predictable way, typically varying up and down with a sine wave or sawtooth pattern at audio frequencies. The signal is then sent out from one antenna and received on another, typically located on the bottom of the aircraft, and the signal can be continuously compared using a simple beat frequency modulator that produces an audio frequency tone from the returned signal and a portion of the transmitted signal.

The modulation index riding on the receive signal is proportional to the time delay between the radar and the reflector. The frequency shift becomes greater with greater time delay. The frequency shift is directly proportional to the distance travelled. That distance can be displayed on an instrument, and it may also be available via the transponder. This signal processing is similar to that used in speed detecting Doppler radar. Example systems using this approach are AZUSA, MISTRAM, and UDOP.

Terrestrial radar uses low-power FM signals that cover a larger frequency range. The multiple reflections are analyzed mathematically for pattern changes with multiple passes creating a computerized synthetic image. Doppler effects are used which allows slow moving objects to be detected as well as largely eliminating "noise" from the surfaces of bodies of water.

Pulse compression

[edit]The two techniques outlined above both have their disadvantages. The pulse timing technique has an inherent tradeoff in that the accuracy of the distance measurement is inversely related to the length of the pulse, while the energy, and thus direction range, is directly related. Increasing power for longer range while maintaining accuracy demands extremely high peak power, with 1960s early warning radars often operating in the tens of megawatts. The continuous wave methods spread this energy out in time and thus require much lower peak power compared to pulse techniques, but requires some method of allowing the sent and received signals to operate at the same time, often demanding two separate antennas.

The introduction of new electronics in the 1960s allowed the two techniques to be combined. It starts with a longer pulse that is also frequency modulated. Spreading the broadcast energy out in time means lower peak energies can be used, with modern examples typically on the order of tens of kilowatts. On reception, the signal is sent into a system that delays different frequencies by different times. The resulting output is a much shorter pulse that is suitable for accurate distance measurement, while also compressing the received energy into a much higher energy peak and thus improving the signal-to-noise ratio. The technique is largely universal on modern large radars.

Speed measurement

[edit]Speed is the change in distance to an object with respect to time. Thus the existing system for measuring distance, combined with a memory capacity to see where the target last was, is enough to measure speed. At one time the memory consisted of a user making grease pencil marks on the radar screen and then calculating the speed using a slide rule. Modern radar systems perform the equivalent operation faster and more accurately using computers.

If the transmitter's output is coherent (phase synchronized), there is another effect that can be used to make almost instant speed measurements (no memory is required), known as the Doppler effect. Most modern radar systems use this principle into Doppler radar and pulse-Doppler radar systems (weather radar, military radar). The Doppler effect is only able to determine the relative speed of the target along the line of sight from the radar to the target. Any component of target velocity perpendicular to the line of sight cannot be determined by using the Doppler effect alone, but it can be determined by tracking the target's azimuth over time.

It is possible to make a Doppler radar without any pulsing, known as a continuous-wave radar (CW radar), by sending out a very pure signal of a known frequency. CW radar is ideal for determining the radial component of a target's velocity. CW radar is typically used by traffic enforcement to measure vehicle speed quickly and accurately where the range is not important.

When using a pulsed radar, the variation between the phase of successive returns gives the distance the target has moved between pulses, and thus its speed can be calculated. Other mathematical developments in radar signal processing include time-frequency analysis (Weyl Heisenberg or wavelet), as well as the chirplet transform which makes use of the change of frequency of returns from moving targets ("chirp").

Pulse-Doppler signal processing

[edit]

Pulse-Doppler signal processing includes frequency filtering in the detection process. The space between each transmit pulse is divided into range cells or range gates. Each cell is filtered independently much like the process used by a spectrum analyzer to produce the display showing different frequencies. Each different distance produces a different spectrum. These spectra are used to perform the detection process. This is required to achieve acceptable performance in hostile environments involving weather, terrain, and electronic countermeasures.

The primary purpose is to measure both the amplitude and frequency of the aggregate reflected signal from multiple distances. This is used with weather radar to measure radial wind velocity and precipitation rate in each different volume of air. This is linked with computing systems to produce a real-time electronic weather map. Aircraft safety depends upon continuous access to accurate weather radar information that is used to prevent injuries and accidents. Weather radar uses a low PRF. Coherency requirements are not as strict as those for military systems because individual signals ordinarily do not need to be separated. Less sophisticated filtering is required, and range ambiguity processing is not normally needed with weather radar in comparison with military radar intended to track air vehicles.

The alternate purpose is "look-down/shoot-down" capability required to improve military air combat survivability. Pulse-Doppler is also used for ground based surveillance radar required to defend personnel and vehicles.[50][51] Pulse-doppler signal processing increases the maximum detection distance using less radiation close to aircraft pilots, shipboard personnel, infantry, and artillery. Reflections from terrain, water, and weather produce signals much larger than aircraft and missiles, which allows fast moving vehicles to hide using nap-of-the-earth flying techniques and stealth technology to avoid detection until an attack vehicle is too close to destroy. Pulse-Doppler signal processing incorporates more sophisticated electronic filtering that safely eliminates this kind of weakness. This requires the use of medium pulse-repetition frequency with phase coherent hardware that has a large dynamic range. Military applications require medium PRF which prevents range from being determined directly, and range ambiguity resolution processing is required to identify the true range of all reflected signals. Radial movement is usually linked with Doppler frequency to produce a lock signal that cannot be produced by radar jamming signals. Pulse-Doppler signal processing also produces audible signals that can be used for threat identification.[50]

Reduction of interference effects

[edit]Signal processing is employed in radar systems to reduce the radar interference effects. Signal processing techniques include moving target indication, Pulse-Doppler signal processing, moving target detection processors, correlation with secondary surveillance radar targets, space-time adaptive processing, and track-before-detect. Constant false alarm rate and digital terrain model processing are also used in clutter environments.

Plot and track extraction

[edit]A track algorithm is a radar performance enhancement strategy. Tracking algorithms provide the ability to predict the future position of multiple moving objects based on the history of the individual positions being reported by sensor systems.

Historical information is accumulated and used to predict future position for use with air traffic control, threat estimation, combat system doctrine, gun aiming, and missile guidance. Position data is accumulated by radar sensors over the span of a few minutes.

There are four common track algorithms:[52]

- Nearest neighbour algorithm

- Probabilistic Data Association

- Multiple Hypothesis Tracking

- Interactive Multiple Model (IMM)

Radar video returns from aircraft can be subjected to a plot extraction process whereby spurious and interfering signals are discarded. A sequence of target returns can be monitored through a device known as a plot extractor.

The non-relevant real time returns can be removed from the displayed information and a single plot displayed. In some radar systems, or alternatively in the command and control system to which the radar is connected, a radar tracker is used to associate the sequence of plots belonging to individual targets and estimate the targets' headings and speeds.

Engineering

[edit]

A radar's components are:

- A transmitter that generates the radio signal with an oscillator such as a klystron or a magnetron and controls its duration by a modulator.

- A waveguide that links the transmitter and the antenna.

- A duplexer that serves as a switch between the antenna and the transmitter or the receiver for the signal when the antenna is used in both situations.

- A receiver. Knowing the shape of the desired received signal (a pulse), an optimal receiver can be designed using a matched filter.

- A display processor to produce signals for human readable output devices.

- An electronic section that controls all those devices and the antenna to perform the radar scan ordered by software.

- A link to end user devices and displays.

Antenna design

[edit]

Radio signals broadcast from a single antenna will spread out in all directions, and likewise a single antenna will receive signals equally from all directions. This leaves the radar with the problem of deciding where the target object is located.

Early systems tended to use omnidirectional broadcast antennas, with directional receiver antennas which were pointed in various directions. For instance, the first system to be deployed, Chain Home, used two straight antennas at right angles for reception, each on a different display. The maximum return would be detected with an antenna at right angles to the target, and a minimum with the antenna pointed directly at it (end on). The operator could determine the direction to a target by rotating the antenna so one display showed a maximum while the other showed a minimum. One serious limitation with this type of solution is that the broadcast is sent out in all directions, so the amount of energy in the direction being examined is a small part of that transmitted. To get a reasonable amount of power on the "target", the transmitting aerial should also be directional.

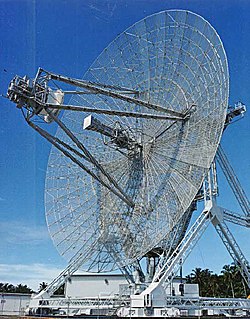

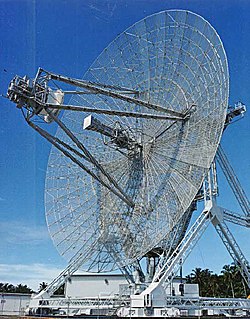

Parabolic reflector

[edit]

More modern systems use a steerable parabolic "dish" to create a tight broadcast beam, typically using the same dish as the receiver. Such systems often combine two radar frequencies in the same antenna in order to allow automatic steering, or radar lock.

Parabolic reflectors can be either symmetric parabolas or spoiled parabolas: Symmetric parabolic antennas produce a narrow "pencil" beam in both the X and Y dimensions and consequently have a higher gain. The NEXRAD Pulse-Doppler weather radar uses a symmetric antenna to perform detailed volumetric scans of the atmosphere. Spoiled parabolic antennas produce a narrow beam in one dimension and a relatively wide beam in the other. This feature is useful if target detection over a wide range of angles is more important than target location in three dimensions. Most 2D surveillance radars use a spoiled parabolic antenna with a narrow azimuthal beamwidth and wide vertical beamwidth. This beam configuration allows the radar operator to detect an aircraft at a specific azimuth but at an indeterminate height. Conversely, so-called "nodder" height finding radars use a dish with a narrow vertical beamwidth and wide azimuthal beamwidth to detect an aircraft at a specific height but with low azimuthal precision.

Types of scan

[edit]- Primary Scan: A scanning technique where the main antenna aerial is moved to produce a scanning beam, examples include circular scan, sector scan, etc.

- Secondary Scan: A scanning technique where the antenna feed is moved to produce a scanning beam, examples include conical scan, unidirectional sector scan, lobe switching, etc.

- Palmer Scan: A scanning technique that produces a scanning beam by moving the main antenna and its feed. A Palmer Scan is a combination of a Primary Scan and a Secondary Scan.

- Conical scanning: The radar beam is rotated in a small circle around the "boresight" axis, which is pointed at the target.

Slotted waveguide

[edit]

Applied similarly to the parabolic reflector, the slotted waveguide is moved mechanically to scan and is particularly suitable for non-tracking surface scan systems, where the vertical pattern may remain constant. Owing to its lower cost and less wind exposure, shipboard, airport surface, and harbour surveillance radars now use this approach in preference to a parabolic antenna.

Phased array

[edit]

Another method of steering is used in a phased array radar.

Phased array antennas are composed of evenly spaced similar antenna elements, such as aerials or rows of slotted waveguide. Each antenna element or group of antenna elements incorporates a discrete phase shift that produces a phase gradient across the array. For example, array elements producing a 5 degree phase shift for each wavelength across the array face will produce a beam pointed 5 degrees away from the centerline perpendicular to the array face. Signals travelling along that beam will be reinforced. Signals offset from that beam will be cancelled. The amount of reinforcement is antenna gain. The amount of cancellation is side-lobe suppression.[53]

Phased array radars have been in use since the earliest years of radar in World War II (Mammut radar), but electronic device limitations led to poor performance. Phased array radars were originally used for missile defence (see for example Safeguard Program). They are the heart of the ship-borne Aegis Combat System and the Patriot Missile System. The massive redundancy associated with having a large number of array elements increases reliability at the expense of gradual performance degradation that occurs as individual phase elements fail. To a lesser extent, phased array radars have been used in weather surveillance. As of 2017, NOAA plans to implement a national network of multi-function phased array radars throughout the United States within 10 years, for meteorological studies and flight monitoring.[54]

Phased array antennas can be built to conform to specific shapes, like missiles, infantry support vehicles, ships, and aircraft.

As the price of electronics has fallen, phased array radars have become more common. Almost all modern military radar systems are based on phased arrays, where the small additional cost is offset by the improved reliability of a system with no moving parts. Traditional moving-antenna designs are still widely used in roles where cost is a significant factor such as air traffic surveillance and similar systems.

Phased array radars are valued for use in aircraft since they can track multiple targets. The first aircraft to use a phased array radar was the B-1B Lancer. The first fighter aircraft to use phased array radar was the Mikoyan MiG-31. The MiG-31M's SBI-16 Zaslon passive electronically scanned array radar was considered to be the world's most powerful fighter radar,[citation needed] until the AN/APG-77 active electronically scanned array was introduced on the Lockheed Martin F-22 Raptor.

Phased-array interferometry or aperture synthesis techniques, using an array of separate dishes that are phased into a single effective aperture, are not typical for radar applications, although they are widely used in radio astronomy. Because of the thinned array curse, such multiple aperture arrays, when used in transmitters, result in narrow beams at the expense of reducing the total power transmitted to the target. In principle, such techniques could increase spatial resolution, but the lower power means that this is generally not effective.

Aperture synthesis by post-processing motion data from a single moving source, on the other hand, is widely used in space and airborne radar systems.

Frequency bands

[edit]Antennas generally have to be sized similar to the wavelength of the operational frequency, normally within an order of magnitude. This provides a strong incentive to use shorter wavelengths as this will result in smaller antennas. Shorter wavelengths also result in higher resolution due to diffraction, meaning the shaped reflector seen on most radars can also be made smaller for any desired beamwidth.

Opposing the move to smaller wavelengths are a number of practical issues. For one, the electronics needed to produce high power very short wavelengths were generally more complex and expensive than the electronics needed for longer wavelengths or did not exist at all. Another issue is that the radar equation's effective aperture figure means that for any given antenna (or reflector) size will be more efficient at longer wavelengths. Additionally, shorter wavelengths may interact with molecules or raindrops in the air, scattering the signal. Very long wavelengths also have additional diffraction effects that make them suitable for over the horizon radars. For this reason, a wide variety of wavelengths are used in different roles.

The traditional band names originated as code-names during World War II and are still in military and aviation use throughout the world. They have been adopted in the United States by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers and internationally by the International Telecommunication Union. Most countries have additional regulations to control which parts of each band are available for civilian or military use.

Other users of the radio spectrum, such as the broadcasting and electronic countermeasures industries, have replaced the traditional military designations with their own systems.

| Band name | Frequency range | Wavelength range | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| HF | 3–30 MHz | 10–100 m | Coastal radar systems, over-the-horizon (OTH) radars; 'high frequency' |

| VHF | 30–300 MHz | 1–10 m | Very long range, ground penetrating; 'very high frequency'. Early radar systems generally operated in VHF as suitable electronics had already been developed for broadcast radio. Today this band is heavily congested and no longer suitable for radar due to interference. |

| P | < 300 MHz | > 1 m | 'P' for 'previous', applied retrospectively to early radar systems; essentially HF + VHF. Often used for remote sensing because of good vegetation penetration. |

| UHF | 300–1000 MHz | 0.3–1 m | Very long range (e.g. ballistic missile early warning), ground penetrating, foliage penetrating; 'ultra high frequency'. Efficiently produced and received at very high energy levels, and also reduces the effects of nuclear blackout, making them useful in the missile detection role. |

| L | 1–2 GHz | 15–30 cm | Long range air traffic control and surveillance; 'L' for 'long'. Widely used for long range early warning radars as they combine good reception qualities with reasonable resolution. |

| S | 2–4 GHz | 7.5–15 cm | Moderate range surveillance, Terminal air traffic control, long-range weather, marine radar; 'S' for 'sentimetric', its code-name during WWII. Less efficient than L, but offering higher resolution, making them especially suitable for long-range ground controlled interception tasks. |

| C | 4–8 GHz | 3.75–7.5 cm | Satellite transponders; a compromise (hence 'C') between X and S bands; weather; long range tracking |

| X | 8–12 GHz | 2.5–3.75 cm | Missile guidance, marine radar, weather, medium-resolution mapping and ground surveillance; in the United States the narrow range 10.525 GHz ±25 MHz is used for airport radar; short-range tracking. Named X band because the frequency was a secret during WW2. Diffraction off raindrops during heavy rain limits the range in the detection role and makes this suitable only for short-range roles or those that deliberately detect rain. |

| Ku | 12–18 GHz | 1.67–2.5 cm | High-resolution, also used for satellite transponders, frequency under K band (hence 'u') |

| K | 18–24 GHz | 1.11–1.67 cm | From German kurz, meaning 'short'. Limited use due to absorption by water vapor at 22 GHz, so Ku and Ka on either side used instead for surveillance. K-band is used for detecting clouds by meteorologists, and by police for detecting speeding motorists. K-band operates at 24.150 ± 0.100 GHz. |

| Ka | 24–40 GHz | 0.75–1.11 cm | Mapping, short range, airport surveillance; frequency just above K band (hence 'a') Photo radar, used to trigger cameras which take pictures of license plates of cars running red lights, and by police for detecting speeding motorists. Operates at 34.300 ± 0.100 GHz. |

| mm | 40–300 GHz | 1.0–7.5 mm | Millimetre band, subdivided as below. Oxygen in the air is an extremely effective attenuator around 60 GHz, as are other molecules at other frequencies, leading to the so-called propagation window at 94 GHz. Even in this window the attenuation is higher than that due to water at 22.2 GHz. This makes these frequencies generally useful only for short-range highly specific radars, like power line avoidance systems for helicopters or use in space where attenuation is not a problem. Multiple letters are assigned to these bands by different groups. These are from Baytron, a now defunct company that made test equipment. |

| V | 40–75 GHz | 4.0–7.5 mm | Very strongly absorbed by atmospheric oxygen, which resonates at 60 GHz. |

| W | 75–110 GHz | 2.7–4.0 mm | Used as a visual sensor for experimental autonomous vehicles, high-resolution meteorological observation, and imaging. |

Modulators

[edit]Modulators act to provide the waveform of the RF-pulse. There are two different radar modulator designs:

- High voltage switch for non-coherent keyed power-oscillators.[55] These modulators consist of a high voltage pulse generator formed from a high voltage supply, a pulse forming network, and a high voltage switch such as a thyratron. They generate short pulses of power to feed, e.g., the magnetron, a special type of vacuum tube that converts DC (usually pulsed) into microwaves. This technology is known as pulsed power. In this way, the transmitted pulse of RF radiation is kept to a defined and usually very short duration.

- Hybrid mixers,[56] fed by a waveform generator and an exciter for a complex but coherent waveform. This waveform can be generated by low power/low-voltage input signals. In this case the radar transmitter must be a power-amplifier, e.g., a klystron or a solid state transmitter. In this way, the transmitted pulse is intrapulse-modulated and the radar receiver must use pulse compression techniques.

Coolant

[edit]Coherent microwave amplifiers operating above 1,000 watts microwave output, like travelling wave tubes and klystrons, require liquid coolant. The electron beam must contain 5 to 10 times more power than the microwave output, which can produce enough heat to generate plasma. This plasma flows from the collector toward the cathode. The same magnetic focusing that guides the electron beam forces the plasma into the path of the electron beam but flowing in the opposite direction. This introduces FM modulation which degrades Doppler performance. To prevent this, liquid coolant with minimum pressure and flow rate is required, and deionized water is normally used in most high power surface radar systems that use Doppler processing.[57]

Coolanol (silicate ester) was used in several military radars in the 1970s. However, it is hygroscopic, leading to hydrolysis and formation of highly flammable alcohol. The loss of a U.S. Navy aircraft in 1978 was attributed to a silicate ester fire.[58] Coolanol is also expensive and toxic. The U.S. Navy has instituted a program named Pollution Prevention (P2) to eliminate or reduce the volume and toxicity of waste, air emissions, and effluent discharges. Because of this, Coolanol is used less often today.

Regulations

[edit]Radar (also: RADAR) is defined by article 1.100 of the International Telecommunication Union's (ITU) ITU Radio Regulations (RR) as:[59]

A radiodetermination system based on the comparison of reference signals with radio signals reflected, or retransmitted, from the position to be determined. Each radiodetermination system shall be classified by the radiocommunication service in which it operates permanently or temporarily. Typical radar utilizations are primary radar and secondary radar, these might operate in the radiolocation service or the radiolocation-satellite service.

Configurations

[edit]Radar come in a variety of configurations in the emitter, the receiver, the antenna, wavelength, scan strategies, etc.

See also

[edit]- Terrain-following radar

- Radar imaging

- Radar navigation

- Inverse-square law

- Wave radar

- Radar signal characteristics

- Pulse doppler radar

- Mmwave sensing

- Acronyms and abbreviations in avionics

- Definitions

- Application

- Hardware

- Cavity magnetron

- Crossed-field amplifier

- Gallium arsenide

- Klystron

- Omniview technology

- Radar engineering details

- Radar tower

- Radio

- Travelling-wave tube

- Similar detection and ranging methods

- Historical radars

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ ITU (2020). "Chapter I – Terminology and technical characteristics" (PDF). Radio Regulations. International Telecommunications Union (ITU). Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ Translation Bureau (2013). "Radar definition". Public Works and Government Services Canada. Archived from the original on 4 January 2014. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ^ McGraw-Hill dictionary of scientific and technical terms / Daniel N. Lapedes, editor in chief. Lapedes, Daniel N. New York; Montreal : McGraw-Hill, 1976. [xv], 1634, A26 p.

- ^ "Radio Detection and Ranging". Nature. 152 (3857): 391–392. 2 October 1943. Bibcode:1943Natur.152..391.. doi:10.1038/152391b0.

- ^ "Remote Sensing Core Curriculum: Radio Detection and Ranging (RADAR)". University of Minnesota. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ Duda, Jeffrey D. "History of Radar Meteorology" (PDF). Archived from the original on 2 March 2023. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

Note: the word radar is actually an acronym that stands for RAdio Detection and Ranging. It was officially coined by U.S. Navy Lieutenant Commanders Samuel M. Tucker and F.R. Furth in November 1940

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Fakhrul Razi Ahmad, Zakuan; et al. (2018). "Performance Assessment of an Integrated Radar Architecture for Multi-Types Frontal Object Detection for Autonomous Vehicle". 2018 IEEE International Conference on Automatic Control and Intelligent Systems (I2CACIS). Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ Kostenko, A.A., A.I. Nosich, and I.A. Tishchenko, "Radar Prehistory, Soviet Side," Proc. of IEEE APS International Symposium 2001, vol. 4. p. 44, 2003

- ^ "Christian Huelsmeyer, the inventor". radarworld.org. Archived from the original on 27 December 2017. Retrieved 18 February 2007.

- ^ Patent DE165546; Verfahren, um metallische Gegenstände mittels elektrischer Wellen einem Beobachter zu melden.

- ^ Verfahren zur Bestimmung der Entfernung von metallischen Gegenständen (Schiffen o. dgl.), deren Gegenwart durch das Verfahren nach Patent 16556 festgestellt wird.

- ^ GB 13170 Telemobiloscope [dead link]

- ^ "gdr_zeichnungpatent.jpg". Archived from the original on 24 February 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ^ "Making waves: Robert Watson-Watt, the pioneer of radar". BBC. 16 February 2017. Archived from the original on 28 February 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ^ "Robert Wattson-Watt". The Lemelson-MIT Program. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Hyland, L.A, A.H. Taylor, and L.C. Young; "System for detecting objects by radio," U.S. Patent No. 1981884, granted 27 November 1934

- ^ Howeth, Linwood S. (1963). "Ch. XXXVIII Radar". History of Communications-Electronics in the United States Navy. Washington.

- ^ Coales, J.F. (1995). The Origins and Development of Radar in the Royal Navy, 1935–45 with Particular Reference to Decimetric Gunnery Equipments. Springer. pp. 5–66. ISBN 978-1-349-13457-1.

- ^ Butement, W. A. S., and P. E. Pollard; "Coastal Defence Apparatus", Inventions Book of the Royal Engineers Board, Jan. 1931

- ^ Swords, S. S.; tech. History of the Beginnings of Radar, Peter Peregrinus, Ltd, 1986, pp. 71–74

- ^ "The "Electric listening device" (1936 – 1941)". museumwaalsdorp.nl. Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- ^ "Radio Waves Warn Liner of Obstacles in Path". Popular Mechanics. Hearst Magazines. December 1935. p. 844. Archived from the original on 7 October 2024. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ Frederick Seitz, Norman G. Einspruch, Electronic Genie: The Tangled History of Silicon – 1998 – page 104

- ^ John Erickson. Radio-Location and the Air Defence Problem: The Design and Development of Soviet Radar. Science Studies, vol. 2, no. 3 (Jul. 1972), pp. 241–263

- ^ "The history of radar, from aircraft radio detectors to airborne radar". kret.com. 17 February 2015. Archived from the original on 20 June 2015. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ^ Page, Robert Morris, The Origin of Radar, Doubleday Anchor, New York, 1962, p. 66

- ^ "Mystery Ray Locates 'Enemy'". Popular Science. Bonnier Corporation. October 1935. p. 29. Archived from the original on 7 October 2024. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ Alan Dower Blumlein (2002). "The story of RADAR Development". Archived from the original on 10 July 2011. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- ^ "Nouveau système de repérage d'obstacles et ses applications" [New obstacle detection system and its applications]. BREVET D'INVENTION (in French). 20 July 1934. Archived from the original on 16 January 2009 – via radar-france.fr.

- ^ "British man first to patent radar". Media Centre (Press release). The Patent Office. 10 September 2001. Archived from the original on 19 July 2006.

- ^ GB 593017 Improvements in or relating to wireless systems

- ^ Angela Hind (5 February 2007). "Briefcase 'that changed the world'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 15 November 2007. Retrieved 16 August 2007.

It not only changed the course of the war by allowing us to develop airborne radar systems, it remains the key piece of technology that lies at the heart of your microwave oven today. The cavity magnetron's invention changed the world.

- ^ Harford, Tim (9 October 2017). "How the search for a 'death ray' led to radar". BBC World Service. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

But by 1940, it was the British who had made a spectacular breakthrough: the resonant cavity magnetron, a radar transmitter far more powerful than its predecessors.... The magnetron stunned the Americans. Their research was years off the pace.

- ^ "Night Watchmen of the Skies". Popular Science. Bonnier Corporation. December 1941. p. 56. Archived from the original on 7 October 2024. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ a b "Odd-shaped Boats Rescue British Engineers". Popular Mechanics. Hearst Magazines. September 1941. p. 26.

- ^ "Scotland's little-known WWII hero who helped beat the Luftwaffe with invention of radar set to be immortalised in film". Daily Record. 16 February 2017. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- ^ Goebel, Greg (1 January 2007). "The Wizard War: WW2 & The Origins of Radar". Archived from the original on 12 July 2024. Retrieved 24 March 2007.

- ^ Kline, Aaron. "AIS vs Radar: Vessel Tracking Options". portvision.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ Quain, John (26 September 2019). "These High-Tech Sensors May Be the Key to Autonomous Cars". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 June 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ ""AWACS: Nato's eyes in the sky"" (PDF). NATO. 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 October 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ "Terma". 8 April 2019.

- ^ "Stopped Vehicle Detection (SVD) Comparison with Automotive Radar" (PDF). Ogier Electronics. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 June 2024.

- ^ "The Technology Behind S+". Sleep.mysplus.com. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ "Project Soli". Atap.google.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Stimson, George (1998). Introduction to Airborne Radar. SciTech Publishing Inc. p. 98. ISBN 978-1-891121-01-2.: 98

- ^ M. Castelaz. "Exploration: The Doppler Effect". Pisgah Astronomical Research Institute.

- ^ a b Riddolls, Ryan J (December 2006). A Canadian Perspective on High-Frequency Over-the-Horizon Radar (PDF) (Technical report). Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Defence Research and Development Canada. p. 38. DRDC Ottawa TM 2006-285. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ Elkins, TJ (March 1980). A model for high frequency radar auroral clutter (PDF) (Technical report). RADC Technical Reports. Vol. 1980. Rome, New York: Rome Air Development Center. p. 9. RADC-TR-80-122. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ Strasser, Nancy C. (December 1980). Investigation of Terrain Bounce Electronic Countermeasure (PDF) (Thesis). Wright-Patterson AFB, Dayton, Ohio: Air Force Institute of Technology. pp. 1–104. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 October 2024. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ a b "Ground Surveillance Radars and Military Intelligence" (PDF). Syracuse Research Corporation; Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 September 2010.

- ^ "AN/PPS-5 Ground Surveillance Radar". 29 December 2009. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021 – via YouTube; jaglavaksoldier's Channel.

- ^ "Fundamentals of Radar Tracking". Applied Technology Institute. Archived from the original on 24 August 2011.

- ^ "Side-Lobe Suppression". MIT. Archived from the original on 31 March 2012. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- ^ National Severe Storms Laboratory. "Multi-function Phased Array Radar (MPAR) Project". NOAA. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- ^ "Radar Modulator". radartutorial.eu. Archived from the original on 7 December 2015. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- ^ "Fully Coherent Radar". radartutorial.eu. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- ^ J.L. de Segovia. "Physics of Outgassing" (PDF). Madrid, Spain: Instituto de Física Aplicada, CETEF "L. Torres Quevedo", CSIC. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 January 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- ^ Stropki, Michael A. (1992). "Polyalphaolefins: A New Improved Cost Effective Aircraft Radar Coolant" (PDF). Melbourne, Australia: Aeronautical Research Laboratory, Defense Science and Technology Organisation, Department of Defense. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- ^ ITU Radio Regulations, Section IV. Radio Stations and Systems – Article 1.100, definition: radar / RADAR

Bibliography

[edit]This "further reading" section may need cleanup. (November 2014) |

References

[edit]- Barrett, Dick, "All you ever wanted to know about British air defence radar". The Radar Pages. (History and details of various British radar systems)

- Buderi, "Telephone History: Radar History". Privateline.com. (Anecdotal account of the carriage of the world's first high power cavity magnetron from Britain to the US during WW2.)

- Ekco Radar WW2 Shadow Factory Archived 12 December 2005 at the Wayback Machine The secret development of British radar.

- ES310 "Introduction to Naval Weapons Engineering.". (Radar fundamentals section)

- Hollmann, Martin, "Radar Family Tree". Radar World.

- Penley, Bill, and Jonathan Penley, "Early Radar History—an Introduction". 2002.

- Pub 1310 Radar Navigation and Maneuvering Board Manual, National Imagery and Mapping Agency, Bethesda, MD 2001 (US govt publication '...intended to be used primarily as a manual of instruction in navigation schools and by naval and merchant marine personnel.')

- Wesley Stout, 1946 "Radar – The Great Detective" Early development and production by Chrysler Corp. during WWII.

- Swords, Seán S., "Technical History of the Beginnings of Radar", IEE History of Technology Series, Vol. 6, London: Peter Peregrinus, 1986

General

[edit]- Reg Batt (1991). The radar army: winning the war of the airwaves. R. Hale. ISBN 978-0-7090-4508-3.

- E.G. Bowen (1 January 1998). Radar Days. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-7503-0586-0.

- Michael Bragg (1 May 2002). RDF1: The Location of Aircraft by Radio Methods 1935–1945. Twayne Publishers. ISBN 978-0-9531544-0-1.

- Louis Brown (1999). A radar history of World War II: technical and military imperatives. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-7503-0659-1.

- Robert Buderi (1996). The invention that changed the world: how a small group of radar pioneers won the Second World War and launched a technological revolution. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-81021-8.

- Burch, David F., Radar For Mariners, McGraw Hill, 2005, ISBN 978-0-07-139867-1.

- Ian Goult (2011). Secret Location: A witness to the Birth of Radar and its Postwar Influence. History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-5776-5.

- Peter S. Hall (March 1991). Radar. Potomac Books Inc. ISBN 978-0-08-037711-7.

- Derek Howse; Naval Radar Trust (February 1993). Radar at sea: the royal Navy in World War 2. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-704-4.

- R.V. Jones (August 1998). Most Secret War. Wordsworth Editions Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85326-699-7.

- Kaiser, Gerald, Chapter 10 in "A Friendly Guide to Wavelets", Birkhauser, Boston, 1994.

- Colin Latham; Anne Stobbs (January 1997). Radar: A Wartime Miracle. Sutton Pub Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7509-1643-1.

- François Le Chevalier (2002). Principles of radar and sonar signal processing. Artech House Publishers. ISBN 978-1-58053-338-6.

- David Pritchard (August 1989). The radar war: Germany's pioneering achievement 1904-45. Harpercollins. ISBN 978-1-85260-246-8.

- Merrill Ivan Skolnik (1 December 1980). Introduction to radar systems. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-066572-9.

- Merrill Ivan Skolnik (1990). Radar handbook. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-057913-2.

- George W. Stimson (1998). Introduction to airborne radar. SciTech Publishing. ISBN 978-1-891121-01-2.