Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

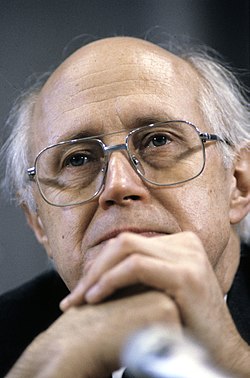

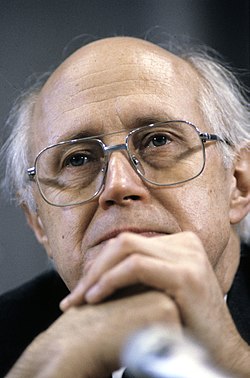

Mstislav Rostropovich

View on Wikipedia

Mstislav Leopoldovich Rostropovich[a] (27 March 1927 – 27 April 2007) was a Russian cellist and conductor. In addition to his interpretations and technique, he was well known for both inspiring and commissioning new works, which enlarged the cello repertoire more than any cellist before or since. He inspired and premiered over 100 pieces,[1] forming long-standing friendships and artistic partnerships with composers including Dmitri Shostakovich, Sergei Prokofiev, Nikolai Myaskovsky, Henri Dutilleux, Witold Lutosławski, Olivier Messiaen, Luciano Berio, Krzysztof Penderecki, Alfred Schnittke, Norbert Moret, Andreas Makris, Leonard Bernstein, Aram Khachaturian, and Benjamin Britten.

Key Information

Rostropovich was internationally recognized as a staunch advocate of human rights, and was awarded the 1974 Award of the International League of Human Rights. He was married to the soprano Galina Vishnevskaya and had two daughters, Olga and Elena Rostropovich. He received numerous accolades, including a Polar Music Prize.

Early years

[edit]

Mstislav Rostropovich was born in Baku, Azerbaijan SSR, to parents who had moved from Orenburg in Russia: Leopold Vitoldovich Rostropovich, a renowned cellist and former student of Pablo Casals,[2] and Sofiya Nikolaevna Fedotova-Rostropovich, a talented pianist. Leopold (1892–1942) was born in Voronezh to Witold Rostropowicz, a composer of Polish noble descent with distant Belarusian roots, and Matilda Rostropovich (née Pule) of German and Huguenot descent. The Polish part of his family bore the Bogoria coat of arms, which was located at the family palace in Skotniki.[3]

Mstislav's mother, Sofiya Fedotova, of Russian descent,[4] was the daughter of musicians and herself a conservatory-trained pianist.[5] Her elder sister, Nadezhda, married cellist Semyon Kozolupov, who was thus Rostropovich's uncle by marriage.[6]

Rostropovich grew up in Baku and spent his youth there. During World War II his family moved back to Orenburg and then, in 1943, to Moscow.[7]

At age four, Rostropovich began studying piano with his mother. He began learning the cello at age eight from his father. In 1943, at age 16, he entered the Moscow Conservatory, where he studied cello with his uncle Semyon Kozolupov, piano with Nikolai Kuvshinnikov, and composition with Vissarion Shebalin. His teachers also included Dmitri Shostakovich. In 1945, he came to prominence as a cellist when he won the gold medal in the Soviet Union's first ever competition for young musicians.[2] He graduated from the Conservatory in 1948 and became professor of cello there in 1956.[citation needed]

First concerts

[edit]

Rostropovich gave his first cello concert in 1942. He won first prize at the International Music Awards of Prague and Budapest in 1947, 1949 and 1950. In 1950, at age 23, he was awarded what was then considered the highest distinction in the Soviet Union, the Stalin Prize.[8] At that time, Rostropovich was already well known in his country and, while actively pursuing his solo career, taught at the Leningrad Conservatory and the Moscow Conservatory. In 1955, he married Galina Vishnevskaya, a leading soprano at the Bolshoi Theatre.[9]

Rostropovich had working relationships with Soviet composers of the era. He was the dedicatee of the Cello Sonata no.2, Op. 81, by Nikolai Myaskovsky who premiered it with the 21-year old Rostropovich in 1949. Inspired by the performance, Sergei Prokofiev wrote his own Cello Sonata, Op. 119, for Rostropovich, who gave the first performance in 1950 with Sviatoslav Richter. Prokofiev also dedicated his Symphony-Concerto to him; this was premiered in 1952. Rostropovich and Dmitry Kabalevsky completed Prokofiev's Cello Concertino after the composer's death. Shostakovich wrote both his first and second cello concertos for Rostropovich, who also gave their first performances.[10]

Rostropovich went on several tours in Western Europe and met several composers, including Benjamin Britten, who dedicated his Cello Sonata, three Solo Suites, and his Cello Symphony to Rostropovich. Rostropovich gave their first performances, and the two had a special affinity; Rostropovich's family described him as "always smiling" when discussing "Ben", and on his deathbed he was said to have expressed no fear, as he and Britten would, he believed, be reunited in Heaven.[11]

Britten was also renowned as a pianist, and together they recorded, among other works, Schubert's Sonata for Arpeggione and Piano in A minor. His daughter claimed that this recording moved her father to tears of joy even on his deathbed.[12]

Rostropovich also had artistic partnerships with Henri Dutilleux (Tout un monde lointain... for cello and orchestra, Trois strophes sur le nom de Sacher for solo cello),[13] Witold Lutosławski (Cello Concerto, Sacher-Variation for solo cello),[14] Krzysztof Penderecki (cello concerto n°2, Largo for cello and orchestra, Per Slava for solo cello, sextet for piano, clarinet, horn, violin, viola, and cello),[15] Luciano Berio (Ritorno degli snovidenia for cello and thirty instruments, Les mots sont allés... for solo cello),[16] and Olivier Messiaen (Concert à quatre for piano, cello, oboe, flute, and orchestra).[17][circular reference][18]

Rostropovich took private lessons in conducting with Leo Ginzburg,[19] and first conducted in public in Gorky in November 1962, performing the four entr'actes from Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District and Shostakovich's orchestration of Mussorgsky's Songs and Dances of Death with Vishnevskaya singing.[20]

In 1967, at the invitation of the Bolshoi Theatre's director Mikhail Chulaki, he conducted Tchaikovsky's opera Eugene Onegin at the Bolshoi.[21]

August 1968 proms

[edit]Rostropovich played at The Proms on the night of 21 August 1968. He played with the USSR State Symphony Orchestra; it was the orchestra's debut performance at the Proms. The programme featured Czech composer Antonín Dvořák's Cello Concerto in B minor and took place on the same day that the Warsaw Pact invaded Czechoslovakia to end Alexander Dubček's Prague Spring.[22] After the performance, which had been preceded by heckling and demonstrations, the orchestra and soloist were cheered by the Proms audience.[23] Rostropovich stood and held aloft the conductor's score of the Dvořák as a gesture of solidarity for the composer's homeland and the city of Prague.[24]

Exile

[edit]

Rostropovich fought for art without borders, freedom of speech, and democratic values, resulting in harassment from the Soviet regime. An early example was in 1948, when he was a student at the Moscow Conservatory. In response to the 10 February 1948 decree on "formalist" composers, his teacher Dmitri Shostakovich was dismissed from his professorships in Leningrad and Moscow; the 21-year-old Rostropovich quit the conservatory in protest.[25] Rostropovich also smuggled to the West the manuscript of Shostakovich's Symphony No. 13, which set verses by Yevgeny Yevtushenko; the subject of its first movement was the Babi Yar massacre.[26]

In 1970, Rostropovich sheltered Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who otherwise would have had nowhere to go, in his own home. His friendship with Solzhenitsyn and support for dissidents led to official disgrace in the early 1970s. As a result, Rostropovich was restricted from foreign touring,[27] as was his wife, Galina Vishnevskaya, and his appearances performing in Moscow were curtailed, as increasingly were his appearances in such major cities as Leningrad and Kiev.[28]

Rostropovich left the Soviet Union in 1974 with his wife and children and settled in the United States. He was banned from touring his homeland with foreign orchestras, and, in 1977, the Soviet leadership instructed musicians from the Soviet bloc not to take part in an international competition he had organised.[29] In 1978, Rostropovich was deprived of his Soviet citizenship because of his public opposition to the Soviet Union's restriction of cultural freedom. He did not return to the Soviet Union until 1990.[8]

Further career

[edit]

On 17 December 1988, Rostropovich gave a special concert at Barbican Hall in London, after postponing a trip to India for the 1988 Armenian earthquake relief program. The event was part of an effort called Musicians for Armenia, which was expected to raise more than $450,000 from donations worldwide, including gifts from musicians, concert proceeds, and film and recording rights. Prince Charles and the Princess of Wales attended the concert in the sold-out 2,026-seat hall.[30]

On 7 February 1989, a cello concert was organized by the Armenian Relief Society and the Volunteers Technical Assistance (VTA) for the victims of the earthquake. At the concert, Rostropovich played his favorite cello repertoire, including Dvořák's Cello Concerto in B minor; Haydn's cello concerti in C and D; Prokofiev's Symphony-Concerto; and Shostakovich's two cello concerti. The evening raised awareness and helped hundreds of earthquake victims put food on their tables. The concert was held at the Kennedy Center, and over 2,300 were in attendance.[31]

From 1977 to 1994, Rostropovich was music director and conductor of the National Symphony Orchestra in Washington, D.C., while still performing with famous musicians such as Martha Argerich, Sviatoslav Richter, and Vladimir Horowitz.[32] He was also the director and founder of the Mstislav Rostropovich Baku International Festival and a regular performer at the Aldeburgh Festival.[33]

His impromptu performance during the fall of the Berlin Wall as events unfolded was reported throughout the world.[34] His Soviet citizenship was restored in 1990. When, in August 1991, news footage was broadcast of tanks in the streets of Moscow, Rostropovich responded with a characteristically brave, impetuous, and patriotic gesture: he bought a plane ticket to Japan on a flight that stopped at Moscow, talked his way out of the airport and went to join Boris Yeltsin in the hope that his fame might make some difference to the chance of tanks moving in.[35] Rostropovich supported Yeltsin during the 1993 constitutional crisis and conducted the U.S. National Symphony Orchestra in Red Square at the height of the crackdown.[36]

In 1993, he was instrumental in the foundation of the Kronberg Academy and was a patron until his death. He commissioned Rodion Shchedrin to compose the opera Lolita and conducted its premiere in 1994 at the Royal Swedish Opera. Rostropovich received many international awards, including the French Legion of Honor and honorary doctorates from many universities. He was an activist, fighting for freedom of expression in art and politics. An ambassador for the UNESCO, he supported many educational and cultural projects.[37] Rostropovich performed several times in Madrid and was a close friend of Queen Sofía of Spain.

With his wife, Galina Vishnevskaya, he founded the Rostropovich-Vishnevskaya Foundation, a publicly supported nonprofit 501(c)(3) organization based in Washington, D.C., in 1991 to improve the health and future of children in the former Soviet Union. The Rostropovich Home Museum opened on 4 March 2002, in Baku.[38] The couple visited Azerbaijan occasionally. Rostropovich also presented cello master classes at the Azerbaijan State Conservatory. Together they formed a valuable art collection. In September 2007, when it was slated to be sold at auction by Sotheby's in London and dispersed, Russian billionaire Alisher Usmanov stepped forward and negotiated the purchase of all 450 lots to keep the collection intact and bring it to Russia as a memorial to Rostropovich. Christie's reported that the buyer paid a "substantially higher" sum than the £20 million pre-sale estimate[39]

In 2006, he was featured in Alexander Sokurov's documentary Elegy of a life: Rostropovich, Vishnevskaya.[40]

Later life

[edit]

Rostropovich's health declined in 2006, with the Chicago Tribune reporting rumours of unspecified surgery in Geneva and later treatment for an aggravated ulcer. Russian President Vladimir Putin visited Rostropovich to discuss details of a celebration the Kremlin was planning for 27 March 2007, Rostropovich's 80th birthday. Rostropovich attended the celebration but was reportedly in frail health.

Though Rostropovich's last home was in Paris, he maintained residences in Moscow, Saint Petersburg, London, Lausanne, and Jordanville, New York. He was admitted to a Paris hospital at the end of January 2007, but then decided to fly to Moscow, where he had been receiving care.[41] On 6 February 2007 Rostropovich was admitted to a hospital in Moscow. "He is just feeling unwell", Natalya Dolezhale, Rostropovich's secretary in Moscow, said.[42] Asked if there was serious cause for concern about his health, she said: "No, right now there is no cause whatsoever." She refused to specify the nature of his illness. The Kremlin said that Putin had visited him in the hospital, which prompted speculation that he was in serious condition. Dolezhale said the visit was to discuss arrangements for marking Rostropovich's 80th birthday. On 27 March 2007, Putin issued a statement praising Rostropovich.[43]

On 7 April 2007, Rostropovich reentered the Blokhin Russian Cancer Research Centre, where he was treated for intestinal cancer. He died on 27 April, aged 80.[34][44][45] On 28 April, Rostropovich's body lay in an open casket at the Moscow Conservatory,[46] and was then moved to the Church of Christ the Saviour. Thousands of mourners, including Putin, bade farewell. Spain's Queen Sofia, French first lady Bernadette Chirac and President Ilham Aliyev of Azerbaijan, where Rostropovich was born, as well as Naina Yeltsina, Yeltsin's widow, were among those who attended the funeral on 29 April. Rostropovich was buried in Novodevichy Cemetery.[47]

Stature

[edit]

Rostropovich was a huge influence on the younger generation of cellists. Many have openly acknowledged their debt to his example. In the Daily Telegraph, Julian Lloyd Webber called him "probably the greatest cellist of all time".[48]

Rostropovich either commissioned or was the recipient of compositions by many composers including Dmitri Shostakovich, Sergei Prokofiev, Nikolai Miaskovsky, Benjamin Britten, Henri Dutilleux, Olivier Messiaen, André Jolivet, Witold Lutosławski, Luciano Berio, Krzysztof Penderecki, Leonard Bernstein, Alfred Schnittke, Aram Khachaturian, Astor Piazzolla, Andreas Makris, Sofia Gubaidulina, Arthur Bliss, Colin Matthews and Lopes Graça. His commissions of new works enlarged the cello repertoire more than any previous cellist: he gave the premiere of 117 compositions.[1]

Rostropovich is also well known for his interpretations of standard repertoire works, including Dvořák's Cello Concerto in B minor.

Between 1997 and 2001, he was intimately involved in the development and testing of the BACH.Bow,[49] a curved bow designed by the cellist Michael Bach. In 2001 he invited Bach to present his BACH.Bow to Paris (7th Concours de violoncelle Rostropovitch).[50] In 2011, the city of Moscow announced plans to erect a statue of Rostropovich in a central square;[51] the statue was unveiled in 2012.[52]

He was also a notably generous spirit. Seiji Ozawa relates an anecdote: on hearing of the death of the baby daughter of his friend the sumo wrestler Chiyonofuji, Rostropovich flew unannounced to Tokyo, took a 1+1⁄2-hour cab ride to Chiyonofuji's house and played his Bach sarabande outside, as his gesture of sympathy—then got back in the taxi and returned to the airport to fly back to Europe.

Rostropovich is included in the Russian-American Chamber of Fame of Congress of Russian Americans, which is dedicated to Russian immigrants who made outstanding contributions to American science or culture.[53]

Awards and recognition

[edit]Rostropovich received about 50 awards during his life, including:

Russian Federation and USSR

[edit]- Order of Merit for the Fatherland;

- 1st class (24 February 2007) – for outstanding contribution to world music and many years of creative activity

- 2nd class (25 March 1997) – for services to the state and the great personal contribution to the world of music

- Medal Defender of a Free Russia (2 February 1993) – for courage and dedication shown during the defence of democracy and constitutional order of 19–21 August 1991

- Jubilee Medal "60 Years of Victory in the Great Patriotic War 1941-1945"

- Medal "For Valiant Labor. To commemorate the 100th anniversary of the birth of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin"

- Medal "For the Victory over Germany in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945"

- Medal "For Valiant Labour in the Great Patriotic War 1941-1945"

- Medal "For the Development of Virgin Lands"

- Medal "In Commemoration of the 800th Anniversary of Moscow"

- People's Artist of the USSR

- People's Artist of the RSFSR (1964)

- Honoured Artist of the RSFSR (1955)

- State Prize of the Russian Federation (1995)

- Lenin Prize (1964)

- Stalin Prize (1951)

- Commemorative Medal for the 850th anniversary of Moscow

Other governmental awards

[edit]- Praemium Imperiale (1993)

- Austrian Cross of Honour for Science and Art, 1st class (2001)[54]

- Heydar Aliyev Order (Azerbaijan, 2007)

- Order "Independence" (Azerbaijan, 3 March 2002)[55]

- Order of "Glory" (Azerbaijan, 1998)

- Order de Mayo (Argentina, 1991)

- Order of Freedom (Argentina, 1994)

- Commander of the Order of the Liberator General San Martín (Argentina, 1994)

- Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold (Belgium, 1989)

- Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Hungary (2003)

- Order of Francisco de Miranda (Venezuela, 1979)

- Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (2001)

- Commander of the Order of the Phoenix (Greece)

- Commander of the Order of the Dannebrog (Denmark, 1983)

- Commander of the Order of Isabella the Catholic (Spain, 1985)

- Commander of the Order of Charles III (Spain, 2004)

- Grand Officer of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic (31 August 1984)[56]

- Grand Officer of the National Order of the Cedar (Lebanon, 1997)

- Grand Officer of the Order of the Lithuanian Grand Duke Gediminas (Lithuania, 24 November 1995)

- 13 January Commemorative Medal (Lithuania, 10 June 1992)

- Commander of the Order of Merit of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg (1999; previously Knight, 1982)

- Commander of the Order of Adolphe of Nassau (Luxembourg, 1991)

- Commander of the Order of Saint-Charles (Monaco, 1989)

- Commander of the Order of Cultural Merit (Monaco, November 1999)[57]

- Commander of the Order of the Dutch Lion (Netherlands, 1989)

- Commander of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland (1997)

- Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Saint James of the Sword (Portugal)

- Order "For merits in the sphere of culture" (Romania, 2004)

- Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands awarded him the rare Medal for Art and Science (Dutch: "Eremedaille voor Kunst en Wetenschap") of the House-Order of Orange.

- Presidential Medal of Freedom (USA, 1987)

- Kennedy Center Honoree (USA, 1992)

- Knight of the Order of Brilliant Star (Taiwan, 1977)

- Knight of the Order of the Lion of Finland

- Grand Officer of the Legion of Honour (France, 1998; previously Commander, 1987, and Officer, 1981)

- Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters (France, 1975)

- Order of Arts and Letters (Sweden) (1984)

- National Order "For Merit" (Ecuador, 1993)

- Order of the Rising Sun, Gold and Silver Star (2nd class) (Japan, 2003)

- Sharaf Order (Order of Honor) of the Republic of Azerbaijan

- Honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (1987)

Honorary citizenships

[edit]- Citizen of honor of Orenburg, Russia (1993)

- Citizen of honor of Vilnius, Lithuania (2000)

- Citizen of honor of Cremona, Italy (2002)

Honorary degrees

[edit]- Honorary Doctorate, University of British Columbia (1984)

- Honorary Doctor of Humane Letters (L.H.D.), Northern Illinois University (1989)

- Laurea ad honorem at the University of Bologna in Political Science (2006)

Competitive awards

[edit]- Grammy Award for Best Chamber Music Performance (1984): Mstislav Rostropovich & Rudolf Serkin for Brahms: Sonata for Cello and Piano in E Minor, Op. 38 and Sonata in F, Op. 99

Other awards

[edit]- Polar Music Prize (1995)

- Gold Medal of the Royal Philharmonic Society (1970)

- Ernst von Siemens Music Prize (1976)

- Sonning Award (1981; Denmark)

- Prince of Asturias Award (in the concord category), 1997 (jointly with Yehudi Menuhin)

- Konex Decoration granted by the Konex Foundation of Argentina in 2002.

- Wolf Prize in Arts (2004)

- Sanford Medal (Yale University)[58]

- Honorary Membership of the Royal Academy of Music, London.[59]

- Gold UNESCO Mozart Medal (2007)[60]

- Roosevelt Institute's Four Freedoms Award for the Freedom of Speech (1992)[61]

See also

[edit]- Slava! A Political Overture, a 1977 composition by Leonard Bernstein

Notes

[edit]- ^ Russian: Мстислав Леопольдович Ростропович, pronounced [rəstrɐˈpovʲɪtɕ]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Мстислав Леопольдович Ростропович. Биографическая справка". RIA Novosti (in Russian). 27 March 2012.

- ^ a b "Mstislav Rostropovich biography". Sony Classical. Archived from the original on 6 February 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ Дмитрий Иванов [in Russian]. "РОСТРОПОВИЧИ (дополненная версия родового герба)". Геральдика.ру (in Russian). Archived from the original on 6 September 2013.

- ^ "Благородный романтик". Vecherniyorenburg.ru (in Russian). 19 March 2022.

- ^ "Софья Николаевна Федотова-Ростропович" (in Russian).

- ^ Elizabeth Wilson, Mstislav Rostropovich: Cellist, Teacher, Legend. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ^ "Mstislav Rostropovich: Obituary". The Times. London. 28 April 2007. Archived from the original on 13 October 2008. Retrieved 4 August 2007.

- ^ a b "Mirė maestro M. Rostropovičius" (in Lithuanian). Lietuvos rytas. 28 April 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ "Biography of Mstislav Rostropovitch". UNESCO. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ Judd, Timothy (18 January 2021). "Shostakovich's Second Cello Concerto: Written for Mstislav Rostropovich". The Listeners' Club. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ John Bridcut, Galina Vishnevskaya, Elena and Olga Rostropovich, Seiji Ozawa, Gennady Rozhdestvensky, Natalia Gutman, and Mischa Maisky (13 December 2011). Rostropovich: The Genius of the Cello (Television). BBC Four.

- ^ "Slava! Courageous Humanitarian". Beethoven Festival Orchestra. 1 September 2007. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- ^ International, MusicWeb (5 May 2022). "DUTILLEUX – Trois Strophes sur le nom de Sacher, Tout un monde lointain; DEBUSSY – Sonata for cello and piano Harmonia Mundi HMC902209 [BBu] Classical Music Reviews: April 2016". MusicWeb-International. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ "Slava and Sacher – conductor". Kenneth Woods. 30 April 2007. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ "Krzysztof Penderecki (1933 – 2020)". HarrisonParrott. 27 February 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2023.

- ^ "Universal Edition". Universal Edition. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ "Concert à quatre". Wikipedia. 8 February 2009. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ Tim Janof (5 August 2019). "Conversation with Mstislav Rostropovich (April, 2006)". CelloBello. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ Wilson: p. 34

- ^ Wilson: p. 188

- ^ Wilson: pp. 287–289.

- ^ "For One Night Only – The Prom of Peace". BBC Radio 4. 1 September 2007. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- ^ Wilson: pp. 292–293

- ^ "1968 Proms". YourClassical from American Public Media and Minnesota Public Radio. 21 August 2019. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ Wilson: p. 45

- ^ "Mstislav Rostropovich, 80; Russian cello virtuoso, iconic political figure - Los Angeles Times". www.latimes.com. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020.

- ^ Wilson: p. 320

- ^ Wilson: p. 329

- ^ "12 May 1977*, 958-A". wordpress.com. 5 July 2016. Archived from the original on 16 March 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ "A Concert in London For Quake Survivors". The New York Times. 19 December 1988.

- ^ "Armenian Relief Society Was at the Center of Earthquake Relief Efforts". Asbarez.com. 6 December 2018.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica (27 April 2007). "National Symphony Orchestra". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ Rostropovich remembered – Britten-Pears Foundation, Undated.Retrieved on 2007-07-31.

- ^ a b "Russian maestro Rostropovich dies". BBC News. 27 April 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ Wilson: p. 345

- ^ Steven Erlanger (27 September 1993). "Isolated Foes of Yeltsin Are Sad but Still Defiant". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- ^ "UNESCO Celebrity Advocates: Mstislav Rostropovitch". UNESCO. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ Gulnar Aydamirova (Summer 2003). "Rostropovich The Home Museum". Azerbaijan International. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ News.BBC.co.uk, 17 September 2007.

- ^ "Elegy Of Life: Rostropovich. Vishnevskaya. Review - Read Variety's Analysis Of The Movie Elegy Of Life: Rostropovich. Vishnevskaya". Variety.com. Archived from the original on 23 September 2010. Retrieved 27 March 2025.

- ^ Allan Kozinn (27 April 2007). "Mstislav Rostropovich, Cellist and Conductor, Dies". The New York Times.

- ^ "Мстислав Ростропович попал в больницу". InterMedia (in Russian). 7 February 2007.

- ^ "Russian President Marks World-renowned Musician's 80th Birthday". VOA News. 27 March 2007. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- ^ "Russian Conductor, Composer, Cellist Rostropovich Dies". Voice of America News. 27 April 2007. Archived from the original on 19 November 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "Russian cellist Rostropovish 'seriously ill'". Contactmusic. Archived from the original on 31 October 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ "Russian Musician Rostropovich Honored Before Burial". VOA News. 28 April 2007. Archived from the original on 19 November 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "Russian farewell to Rostropovich". BBC News. 29 April 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ Julian Lloyd Webber (28 April 2007). "The greatest cellist of all time". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 6 August 2007.

- ^ "Mstislav Rostropovich". Bach-bogen.de.

- ^ "Presentation of the BACH.Bogen®". Cello.org. 6 October 2001. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ "Rostropovich statue set to be unveiled in Moscow for cellist's 85th anniversary". The Strad. 15 July 2011. Archived from the original on 5 July 2015. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ "Putin Praises Cellist Rostropovich at Monument Opening". The Moscow Times. 30 March 2012. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ "Hall of Fame". russian-americans.org. 20 June 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ "Reply to a parliamentary question" (PDF) (in German). p. 1447. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ "M. L. Rostropoviçin "İstiqlal"ordeni ilə təltif edilməsi haqqında AZƏRBAYCAN RESPUBLİKASI PREZİDENTİNİN FƏRMANI" [Order of the President of Azerbaijan Republic on awarding M. L. Rostropovich with Istiglal Order of Azerbaijan Republic]. Archived from the original on 20 November 2011. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ^ "Onorificenze: parametri di ricerca" (in Italian). Italian Presidency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ Sovereign Ordonnance n° 14.274 of 18 Nov. 1999 : promotions or nominations

- ^ Leading clarinetist to receive Sanford Medal Archived 2012-07-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Botstein, L. (2007). "Unforgettable Life in Music: Mstislav Rostropovich (1927–2007)". The Musical Quarterly. pp. 153–163. doi:10.1093/musqtl/gdm001. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- ^ "Death of master Russian cellist and UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador mourned". 27 April 2007. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ^ "Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Awards – Roosevelt Institute". rooseveltinstitute.org. 29 September 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

Sources

[edit]- Wilson, Elizabeth, Mstislav Rostropovich: Cellist, Teacher, Legend. London: Faber & Faber, 2007. ISBN 978-0-571-22051-9

Further reading

[edit]- Mstislav Rostropovich and Galina Vishnevskaya. Russia, Music, and Liberty. Conversations with Claude Samuel, Amadeus Press, Portland (1995), ISBN 0-931340-76-4

- Rostrospektive. Zum Leben und Werk von Mstislaw Rostropowitsch. On the Life and Achievement of Mstislav Rostropovich, Alexander Ivashkin and Josef Oehrlein, Internationale Kammermusik-Akademie Kronberg, Schweinfurt: Maier (1997), ISBN 3-926300-30-2

- Inside the Recording Studio. Working with Callas, Rostropovich, Domingo, and the Classical Elite, Peter Andry, with Robin Stringer and Tony Locantro, The Scarecrow Press, Lanham MD (2008). ISBN 978-0-8108-6026-1

External links

[edit]- Rostropovich Vishnevskaya Foundation

- Home-museum of Leopold and Mstislav Rostropovich dead link

- Rostropovich: The Home Museum (Baku, Azerbaijan) by Gulnar Aydamirova. AZER.com, Azerbaijan International, Vol. 11:2 (Summer 2003), pp. 40-42.

- Mstislav Rostropovich: Cellist, Conductor, Humanitarian Cellist Arash Amini shares his personal experiences with Slava, a feature from the Bloomingdale School of Music (October 2007)

- "Why the cello is a hero", interview with The Daily Telegraph

- Interview by Tim Janof

- Famous People: Then and Now: Mstislav Rostropovich: Cellist and Conductor (1927-2007). AZER.com, Azerbaijan International, Vol. 7:4 (Winter 1999), pp. 24-25.

- Intellectual Responsibility. When Silence Is Not Golden: Conversations with Mstislav Rostropovich and Galina Vishnevskaya by Claude Samuel. AZER.com Azerbaijan International, Vol. 13:2 (Summer 2005), 28-29.

- Hearing Mstislav Rostropovich Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine survey of Rostropovich recordings, by Jens F. Laurson (WETA, 4 May 2007)

- 1987 Presidential Medal of Freedom Recipients Archived 2015-10-16 at the Wayback Machine

- The first Prague Spring International Cello Competition in 1950 in photographs, documents and reminiscences Archived 2011-08-19 at the Wayback Machine

- National Symphony Orchestra Pays Homage to Rostropovich, WQXR Live Broadcast, Spring for Music Festival, Carnegie Hall, New York (11 May 2013)

- Interview with Mstislav Rostropovich by Bruce Duffie, 30 April 2004

- Playing Brahms

- Conference in Brescia, 4 June 2003 ed. by Carlo Bianchi