Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Scale model

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2022) |

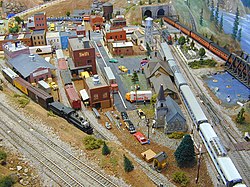

A scale model is a physical model that is geometrically similar to an object (known as the prototype). Scale models are generally smaller than large prototypes such as vehicles, buildings, or people; but may be larger than small prototypes such as anatomical structures or subatomic particles. Models built to the same scale as the prototype are called mockups.

Scale models are used as tools in engineering design and testing, promotion and sales, filmmaking special effects, military strategy, and hobbies such as rail transport modeling, wargaming and racing; and as toys. Model building is also pursued as a hobby for the sake of artisanship.

Scale models are constructed of plastic, wood, or metal. They are usually painted with enamel, lacquer, or acrylics. Model prototypes include all types of vehicles (railroad trains, cars, trucks, military vehicles, aircraft, and spacecraft), buildings, people, and science fiction themes (spaceships and robots).

Methods

[edit]

The models are built to scale, defined as the ratio of any linear dimension of the model to the equivalent dimension on the full-size subject (called the "prototype"), expressed either as a ratio with a colon (ex. 1:8 scale), or as a fraction with a slash (1/8 scale). This designates that 1 length unit on the model represents 8 such units on the prototype. In English-speaking countries, the scale is sometimes expressed as the number of feet on the prototype corresponding to one inch on the model, e.g. 1:48 scale = "1 inch to 4 feet", 1:96 = "1 inch to 8 feet", etc.

Models are obtained by three different means: kit assembly, scratch building, and collecting pre-assembled models. Scratch building is the only option available to structural engineers, and among hobbyists requires the highest level of skill, craftsmanship, and time; scratch builders tend to be the most concerned with accuracy and detail.[citation needed] Kit assembly is done either "out of the box", or with modifications (known as "kitbashing"). Many kit manufacturers, for various reasons leave something to be desired in terms of accuracy, but using the kit parts as a baseline and adding after-market conversion kits, alternative decal sets, and some scratch building can correct this without the master craftsmanship or time expenditure required by scratch building.

Purposes

[edit]

Scale models are generally of two types: static and animated. They are used for several purposes in many fields, including:

Hobby

[edit]Most hobbyist models are built for static display, but some have operational features, such as railroad trains that roll, and airplanes and rockets that fly. Flying airplane models may be simple unpowered gliders, or have sophisticated features such as radio control powered by miniature methanol/nitromethane engines.

Slot car racing

[edit]Cars in 1:24, 1:32, or HO scale are fitted with externally powered electric motors which run on plastic road track fitted with metal rails on slots. The track may or may not be augmented with miniature buildings, trees, and people.

Wood car racing

[edit]Children can build and race their own gravity-powered, uncontrolled cars carved out of a wood such as pine, with plastic wheels on metal axles, which run on inclined tracks.

The most famous wood racing event is the Boy Scouts of America's annual Pinewood Derby which debuted in 1953. Entry is open to Cub Scouts. Entrants are supplied with a kit containing a wooden block out of which to carve the body, four plastic wheels, and four axle nails; or they may purchase their own commercially available kit. Regulations generally limit the car's weight to 5 ounces (141.7 g), width to 2.75 inches (7.0 cm), and length to 7 inches (17.8 cm). The rules permit the cars to be augmented with tungsten carbide weights up to the limit, and graphite axle lubricant.

Wargaming

[edit]Miniature wargames are played using miniature soldiers, artillery, vehicles, and scenery built by the players.

Television and film production

[edit]Before the advent of computer-generated imagery (CGI), visual effects of vehicles such as marine ships and cyber vehicles were created by filming "miniature" models. These were considerably larger scale than hobby versions to allow inclusion of a high degree of surface detail, and electrical features such as interior lighting and animation. For Star Trek: The Original Series, a 33-inch (0.84 m) pre-production model of the Starship Enterprise was created in December 1964, mostly of pine, with Plexiglass and brass details, at a cost of $600.[1] This was followed by a 135.5-inch (3.44 m) production model constructed from plaster, sheet metal, and wood, at ten times the cost of the first.[2][3] As the Enterprise was originally reckoned to be 947 feet (289 m) long, this put the models at 1:344 and 1:83.9 scale respectively. The Polar Lights company sells a large plastic Enterprise model kit essentially the same size as the first TV model, in 1:350 scale (32 inches long). It can be purchased with an optional electronic lighting and animation (rotating engine domes) kit.

Engineering

[edit]Structural

[edit]

Although structural engineering has been a field of study for thousands of years and many of the great problems have been solved using analytical and numerical techniques, many problems are still too complicated to understand in an analytical manner or the current numerical techniques lack real world confirmation. When this is the case, for example a complicated reinforced concrete beam-column-slab interaction problem, scale models can be constructed observing the requirements of similitude to study the problem. Many structural labs exist to test these structural scale models such as the Newmark Civil Engineering Laboratory at the University of Illinois, UC.[5]

For structural engineering scale models, it is important for several specific quantities to be scaled according to the theory of similitude. These quantities can be broadly grouped into three categories: loading, geometry, and material properties. A good reference for considering scales for a structural scale model under static loading conditions in the elastic regime is presented in Table 2.2 of the book Structural Modeling and Experimental Techniques.[6]

Structural engineering scale models can use different approaches to satisfy the similitude requirements of scale model fabrication and testing. A practical introduction to scale model design and testing is discussed in the paper "Pseudodynamic Testing of Scaled Models".[7]

Aerodynamic

[edit]Aerodynamic models may be used for testing new aircraft designs in a wind tunnel or in free flight. Models of scale large enough to permit piloting may be used for testing of a proposed design.

Architectural

[edit]

Architecture firms usually employ model makers or contract model making firms to make models of projects to sell their designs to builders and investors. These models are traditionally hand-made, but advances in technology have turned the industry into a very high tech process than can involve Class IV laser cutters, five-axis CNC machines as well as rapid prototyping or 3D printing. Typical scales are 1:12, 1:24, 1:48, 1:50, 1:100, 1:200, 1:500, etc.

Advertising and sales

[edit]This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (January 2025) |

Military

[edit]

With elements similar to miniature wargaming, building models and architectural models, a plan-relief is a means of geographical representation in relief as a scale model for military use, to visualize building projects on fortifications or campaigns involving fortifications.

In the first half of the 20th century, navies used hand-made models of warships for identification and instruction in a variety of scales. That of 1:500 was called "teacher scale." Besides models made in 1:1200 and 1:2400 scales, there were also ones made to 1:2000 and 1:5000. Some, made in Britain, were labelled "1 inch to 110 feet", which would be 1:1320 scale, but are not necessarily accurate.

Manned ships

[edit]Many research workers, hydraulics specialists and engineers have used scale models for over a century, in particular in towing tanks. Manned models are small scale models that can carry and be handled by at least one person on an open expanse of water. They must behave just like real ships, giving the shiphandler the same sensations. Physical conditions such as wind, currents, waves, water depths, channels, and berths must be reproduced realistically.

Manned models are used for research (e.g. ship behaviour), engineering (e.g. port layout) and for training in shiphandling (e.g. maritime pilots, masters and officers). They are usually at 1:25 scale.

Materials

[edit]Models, and their constituent parts, can be built out of a variety of materials, such as:

Plastic

[edit]This includes injection molded or extruded plastics such as polystyrene, acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), butyrate, and clear acrylic and copolyester (PETG). Parts can also be cast from synthetic resins.

Wood

[edit]Pine wood is sometimes used; balsa wood, a light wood, is good for flying airplane models.

Metal

[edit]Aluminum or brass can be used in tubing form, or can be used in flat sheets with photo-etched surface detail. Model figures used in wargaming can be made of white metal.

Glue

[edit]Styrene parts are welded together using plastic cement, which comes both in a thick form to be carefully applied to a bonding surface, or in a thin liquid which is applied into a joint by capillary action using a brush or syringe needle. Ethyl cyanoacrylate (ECA) aka "super-glue", or fast-setting epoxy, must be used to bond styrene to other materials.

Paint

[edit]Glossy colors are generally used for car and commercial truck exteriors. Flat colors are generally desirable for military vehicles, aircraft, and spacecraft. Metallic colors simulate the various metals (silver, gold, aluminum, steel, copper, brass, etc.)

Enamel paint has classically been used for model making and is generally considered the most durable paint for plastics. It is available in small bottles for brushing and airbrushing, and aerosol spray cans. Disadvantages include toxicity and a strong chemical smell of the paint and its mineral spirit thinner/brush cleaner. Modern enamels are made of alkyd resin to limit toxicity. Popular brands include Testor's in the US and Humbrol (now Hornby) in the UK.

Lacquer paint produces a hard, durable finish, and requires its own lacquer thinner.

Enamels have been generally replaced in popularity by acrylic paint, which is water-based. Advantages include decreased toxicity and chemical smell, and brushes clean with soap and water. Disadvantages include possibly limited durability on plastic, requiring priming coats, at least two color coats, and allowing adequate cure time. Popular brands include the Japanese import Tamiya.

Some beginner's level kits avoid the necessity to paint the model by adding pigments and chrome plating to the plastic.

Decals

[edit]Decals are generally applied to models after painting and assembly, to add details such as lettering, flags, insignia, or other decorations too small to paint. Water transfer (slide-on) decals are generally used, but beginner's kits may use dry transfer stickers instead.

Subjects

[edit]Vehicles

[edit]Trains

[edit]

Model railroading (US and Canada; known as railway modelling in UK, Australia, New Zealand, and Ireland) is done in a variety of scales from 1:4 to 1:450 (T scale). Each scale has its own strengths and weaknesses, and fills a different niche in the hobby:

- The largest scales are used outdoors, for "Live steam" railroads with trains large enough for people to ride on, as much as 3 meters (9.8 ft) longs are built in several scales such as 1-1/2", 1", and 3/4 inches to the foot. Common gauges are 7-1/2" (Western US) and 7-1/4" (Eastern US & rest of the world), 5", and 4-3/4". Smaller live steam gauges do exist, but as the scale gets smaller, pulling power decreases. One of the smallest gauges on which a live steam engine can pull a passenger is the now almost defunct 2+1⁄2-inch gauge.

- The next largest scale range, G scale (1:22.5) in the US and 16 mm scale (1:19.05) in the UK, and as large as 1:12 scale, is too small for riding but is used for outdoor garden railways, which allow use of natural landscaping. G scale is also sometimes used indoors, with the track mounted adjacent to walls at eye level of standing adults. A franchise chain of restaurants and coffeehouses named Výtopna in the Czech Republic acquired a trademark for the use of G-scale trains mounted on the countertops to serve customers beverages, and pick up their orders and empty glasses.[8][9][10]

- Smaller scales are used indoors. O scale (1:48) sets were introduced as early "toy trains" by companies such as Lionel Corporation, but has developed a following among serious adult hobbyists. American Flyer purchased by A. C. Gilbert Company popularized S scale (1:64) trains starting in 1946. Even smaller scales have become the most popular, allowing larger, more complex layouts to be built in smaller spaces. Dedicated model railroaders often mount indoor layouts on homemade plywood tables, at a height in the range of 30 to 42 inches (76 to 107 cm), putting the track optimally close to eye level for children or adults.[11] As of 2022, the two most popular sizes are HO scale (1:87) and N scale (1:160).[12]

| Name | Scale | Standard

gauge |

Narrow

gauge |

Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | 1:450 | Indoor | ||

| ZZ | 1:300 | Indoor | ||

| Z | 1:220 | Indoor | ||

| N | 1:160 | 9 mm | Indoor | |

| 2mm | 1:152 | Indoor | ||

| TT | 1:120 | 12 mm | Indoor | |

| 3mm | 1:101 | Indoor | ||

| HO | 1:87 | 16.5 mm | Indoor | |

| OO | 1:76.2 | 16.5 mm | Indoor | |

| S | 1:64 | Indoor | ||

| O | 1:48 | Indoor | ||

| 1 | 1:32 | 44.45 | Garden; live steam | |

| H | 1:24 | 45 mm | Garden; live steam | |

| G | 1:22.5 | 45 mm | Garden; live steam | |

| 1:12 | Garden; live steam | |||

| 1:4 | Live steam |

Gauge vs scale

[edit]Model railroads originally used the term gauge, which refers to the distance between the rails, just as full-size railroads continue to do. Although model railroads were also built to different gauges, standard gauge in full-size railroads is 4' 8.5". Therefore, a model railroad reduces that standard to scale. An HO scale model railroad runs on track that is 1/87 of 4' 8.5", or 0.649" from rail to rail. Today model railroads are more typically referred to using the term scale instead of "gauge" in most usages.

Confusion arises from indiscriminate use of "scale" and "gauge" synonymously. The word "scale" strictly refers to the proportional size of the model, while "gauge" strictly applies to the measurement between the inside faces of the rails. It is completely incorrect to refer to the mainstream scales as "HO gauge", "N gauge, "Z gauge", etc. This is further complicated by the fact some scales use several different gauges; for example, HO scale uses 16.5 mm as the standard gauge of 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm), 12 mm to represent 1,000 mm (3 ft 3+3⁄8 in) gauge (HOm), and 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) (HOn3-1/2), and 9 mm to represent a prototype gauge of 2 ft (610 mm).

The most popular scale to go with a given gauge was often arrived at through the following roundabout process: German artisans would take strips of metal of standard metric size to construct their products from blueprints dimensioned in inches. "Four mm to the foot" yielded the 1:76.2 size of the British "OO scale", which is anomalously used on the standard HO/OO scale (16.5 mm gauge from 3.5 mm/foot scale) tracks, because early electric motors weren't available commercially in smaller sizes. Today, most scale sizes are internationally standardized, with the notable exceptions of O scale and N scale.

There are three different versions of the "O" scale, each of which uses tracks of 32 mm for the standard gauge. The American version follows a dollhouse scale of 1:48, sometimes called "quarter-gauge" as in "one-quarter-inch to the foot". The British version continued the pattern of sub-contracting to Germans, so, at 7 mm to the foot, it works out to a scale of 1:43.5. Later, the European authority of model railroad firms MOROP declared that the "O" gauge (still 32 mm) must use the scale of 1:45, to allow wheel, tire, and splasher clearance for smaller than realistic curved sections.

N scale trains were first commercially produced at 1:160 scale in 1962 by the Arnold company of Nuremberg.[13][12] This standard size was imported to the US by firms such as the Aurora Plastics Corporation. However, the early N-scale motors would not fit in the smaller models of British locomotives, so the British N gauge was standardized to allow a slightly larger body size. Similar sizing problems with Japanese prototypes led to adoption of a 1:150 scale standard there. Since space is more limited in Japanese houses, N scale has become more popular there than HO scale.

Aircraft

[edit]

Static model aircraft are commonly built using plastic, but wood, metal, card and paper can also be used. Models are sold painted and assembled, painted but not assembled (snap-fit), or unpainted and not assembled. The most popular types of aircraft to model are commercial airliners and military aircraft. Popular aircraft scales are, in order of increasing size: 1:144, 1:87 (also known as HO, or "half-O scale"), 1:72 (the most numerous), 1:48 (known as "O scale"), 1:32, 1:24, 1:16, 1:6, and 1:4. Some European models are available at more metric scales such as 1:50. The highest quality models are made from injection molded plastic or cast resin. Models made from Vacuum formed plastic are generally for the more skilled builder. More inexpensive models are made from heavy paper or card stock. Ready-made die-cast metal models are also very popular. As well as the traditional scales, die-cast models are available in 1:200, 1:250, 1:350, 1:400, 1:500 and 1:600 scale.

The majority of aircraft modelers concern themselves with depiction of real-life aircraft, but there are some modelers who 'bend' history by modeling aircraft that either never actually flew or existed, or by painting them in a color scheme that did not actually exist. This is commonly referred to as 'What-if' or 'Alternative' modeling, and the most common theme is 'Luftwaffe 1946' or 'Luftwaffe '46'. This theme stems from the idea of modeling German secret projects that never saw the light of day due to the close of World War II. This concept has been extended to include British, Russian, and US experimental projects that never made it into production.

Flying model aircraft are built for aerodynamic research and for recreation (aeromodeling).

Recreational models are often made to resemble some real type. However the aerodynamic requirements of a small model are different from those of a full-size craft, so flying models are seldom fully accurate to scale. Flying model aircraft are one of three types: free flight, control line, and radio controlled. Some flying model kits take many hours to put together, and some kits are almost ready to fly or ready to fly.

Rockets and spacecraft

[edit]Model rocketry dates back to the Space Race of the 1950s. The first model rocket engine was designed in 1954 by Orville Carlisle, a licensed pyrotechnics expert, and his brother Robert, a model airplane enthusiast.[14]

Static model rocket kits began as a development of model aircraft kits, yet the scale of 1:72 [V.close to 4 mm.::1foot] never caught on. Scales 1:48 and 1:96 are most frequently used. There are some rockets of scales 1:128, 1:144, and 1:200, but Russian firms put their large rockets in 1:288. Heller SA offers some models in the scale of 1:125.

Science fiction space ships are heavily popular in the modeling community. In 1966, with the release of the television show Star Trek: The Original Series, AMT corporation released an 18-inch (46 cm) model of the Starship Enterprise. This has been followed over the decades by a complete array of various starships, shuttlecraft, and space stations from the Star Trek franchise. The 1977 release of the first Star Wars film and the 1978 TV series Battlestar Galactica also spawned lines of licensed model kits in scales ranging from 1:24 for fighters and smaller ships, to 1:1000, 1:1400, and 1:2500 for most main franchise ships, and up to 1:10000 for the larger Star Wars ships (for especially objects like the Death Stars and Super Star Destroyers, even smaller scales are used). Finemolds in Japan have recently released a series of high quality injection molded Star Wars kits in 1:72, and this range is supplemented by resin kits from Fantastic Plastic.

Cars

[edit]

Although the British scale for 0 gauge was first used for model cars made of rectilinear and circular parts, it was the origin of the European scale for cast or injection molded model cars. MOROP's specification of 1:45 scale for European 0 does not alter the series of cars in 1:43 scale, as it has the widest distribution in the world.

In America, a series of cars was developed from at first cast metal and later styrene models ("promos") offered at new-car dealerships to drum up interest. The firm Monogram, and later Tamiya, first produced them in a scale derived from the Architect's scale: 1:24 scale, while the firms AMT, Jo-Han, and Revell chose the scale of 1:25. Monogram later switched to this scale after the firm was purchased by Revell. Some cars are also made in 1:32 scale, and rolling toys are often made on the scale 1:64 scale. Chinese die-cast manufacturers have introduced 1/72 scale into their range. The smaller scales are usually die-cast cars and not the in the class as model cars. Except in rare occasions, Johnny Lightning and Ertl-made die-cast cars were sold as kits for buyers to assemble. Model cars are also used in car design.

Buses and trucks

[edit]Typically found in 1:50 scale, most manufacturers of commercial vehicles and heavy equipment commission scale models made of die-cast metal as promotional items to give to prospective customers. These are also popular children's toys and collectibles. The major manufacturers of these items are Conrad and NZG in Germany. Corgi also makes some 1:50 models, as well as Dutch maker Tekno.

Trucks are also found as diecast models in 1:43 scale and injection molded kits (and children's toys) in 1:24 scale. Recently some manufacturers have appeared in 1:64 scale like Code 3.

Construction vehicles

[edit]

A model construction vehicle (or engineering vehicle) is a scale model or die-cast toy that represents a construction vehicle such as a bulldozer, excavator, crane, concrete pump, backhoe, etc.

Construction vehicle models are almost always made in 1:50 scale, particularly because the cranes at this scale are often three to four feet tall when extended and larger scales would be unsuited for display on a desk or table. These models are popular as children's toys in Germany. In the US they are commonly sold as promotional models for new construction equipment, commissioned by the manufacturer of the prototype real-world equipment. The major manufacturers in Germany are Conrad and NZG, with some competition from Chinese firms that have been entering the market.

Robots

[edit]Japanese firms have marketed toys and models of what are often called mecha, nimble humanoid fighting robots. The robots, which appear in animated shows (anime), are often depicted at a size between 15-20m in height, and so scales of 1:100 and 1:144 are common for these subjects, though other scales such as 1:72 are commonly used for robots and related subjects of different size.

The most prolific manufacturer of mecha models is Bandai, whose Gundam kit lines were a strong influence in the genre in the 1980s. Even today, Gundam kits are the most numerous in the mecha modeling genre, usually with dozens of new releases every year. The features of modern Gundam kits, such as color molding and snap-fit construction, have become the standard expectations for other mecha model kits.

Due to the fantasy nature of most anime robots, and the necessary simplicity of cel-animated designs, mecha models lend themselves well to stylized work, improvisations, and simple scratchbuilds. One of Gundam's contributions to the genre was the use of a gritty wartime backstory as a part of the fantasy, and so it is almost equally fashionable to build the robots in a weathered, beaten style, as would often be expected for AFV kits as to build them in a more stylish, pristine manner.

Live action figures

[edit]Scale models of people and animals are found in a wide variety of venues, and may be either single-piece objects or kits that must be assembled, usually depending on the purpose of the model. For instance, models of people as well as both domestic and wild animals are often produced for display in model cities or railroads to provide a measure of detail or realism, and scaled relative to the trains, buildings, and other accessories of a certain line of models. If a line of trains or buildings does not feature models of living creatures, those who build the models often buy these items separately from another line so they can feature people or animals. In other cases, scale model lines feature living creatures exclusively, often focusing on educational interests.

Model kits of superheroes and super-villains from popular franchises such as DC Entertainment and Marvel Entertainment are also sold, as are models of real-world celebrities, such as Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley.

One type of assembly kit sold as educational features skeletons and anatomical structure of humans and animals. Such kits may have unique features such as glow-in-the-dark pieces. Dinosaurs are a popular subject for such models. There are also garage kits, which are often figures of anime characters in multiple parts that require assembly.

Ships and naval war-gaming

[edit]

Michele Morciano says small scale ship models were produced in about 1905 linked to the wargaming rules and other publications of Fred T. Jane. The company that standardized on 1:1200 was Bassett-Lowke in 1908. The British Admiralty subsequently contracted with Bassett-Lowke and other companies and individual craftsmen to produce large numbers of recognition models, to this scale, in 1914–18.[15]

Just before the Second World War, the American naval historian (and science fiction author) Fletcher Pratt published a book on naval wargaming as could be done by civilians using ship models cut off at the waterline to be moved on the floors of basketball courts and similar locales. The scale he used was non-standard (reported as 1:666), and may have been influenced by toy ships then available, but as the hobby progressed, and other rule sets came into use, it was progressively supplemented by the series 1:600, 1:1200, and 1:2400. In Britain, 1:3000 became popular and these models also have come into use in the USA. These had the advantage of approximating the nautical mile as 120 inches, 60 inches, and 30 inches, respectively. As the knot is based on this mile and a 60-minute hour, this was quite handy.

After the war, firms emerged to produce models from the same white metal used to make toy soldiers. Lines Bros. Ltd, a British firm, offered a tremendously wide range of waterline merchant and naval ships as well as dockyard equipment in the scale 1:1200 which were die-cast in Zamak. In the US, at least one manufacturer, of the wartime 1:1200 recognition models, Comet, made them available for the civilian market postwar, which also drove the change to this scale. In addition, continental European manufacturers and European ship book publishers had adopted the 1:1250 drawing scale because of its similar convenience in size for both models and comparison drawings in books.

A prestige scale for boats, comparable to that of 1:32 for fighter planes, is 1:72, producing huge models, but there are very few kits marketed in this scale. There are now several clubs around the world for those who choose to scratch-build radio-controlled model ships and submarines in 1:72, which is often done because of the compatibility with naval aircraft kits. For the smaller ships, plank-on-frame or other wood construction kits are offered in the traditional shipyard scales of 1:96, 1:108, or 1:192 (half of 1:96). In injection-molded plastic kits, Airfix makes full-hull models in the scale the Royal Navy has used to compare the relative sizes of ships: 1:600. Revell makes some kits to half the scale of the US Army standard: 1:570. Some American and foreign firms have made models in a proportion from the Engineer's scale: "one-sixtieth-of-an-inch-to-the-foot", or 1:720.

Tanks and wargaming

[edit]

Early in the 20th century, the British historian and science fiction author H. G. Wells published a book, Little Wars, on how to play at battles in miniature. His books use 2" lead figures,[16] particularly those manufactured by Britains. His fighting system employed spring-loaded model guns that shot matchsticks.

This use of physical mechanisms was echoed in the later games of Fred Jane, whose rules required throwing darts at ship silhouettes; his collection of data on the world's fleets was later published and became renowned. Dice have largely replaced this toy mayhem for consumers.

For over a century, toy soldiers were made of white metal, a lead-based alloy, often in architect's scale-based ratios in the English-speaking countries, and called tin soldiers. After the Second World War, such toys were on the market for children but now made of a safe plastic softer than styrene. American children called these "army men". Many sets were made in the new scale of 1:40. A few styrene model kits of land equipment were offered in this and in 1:48 and 1:32 scales. However, these were swept away by the number of kits in the scale of 1:35.

Those who continued to develop miniature wargaming preferred smaller scale models, the soldiers still made of soft plastic. Airfix particularly wanted people to buy 1:76 scale soldiers and tanks to go with "00" gauge train equipment. Roco offered 1:87 scale styrene military vehicles to go with "HO" gauge model houses. However, although there is no 1:72 scale model railroad, more toy soldiers are now offered in this scale because it is the same as the popular aircraft scale. The number of fighting vehicles in this scale is also increasing, although the number of auxiliary vehicles available is far fewer than in 1:87 scale.

A more recent development, especially in wargaming of land battles, is 15 mm white metal miniatures, often referred to as 1:100. The use of 15 mm scale metals has grown quickly since the early 1990s as they allow a more affordable option over 28 mm if large battles are to be refought, or a large number of vehicles represented. The rapid rise in the detail and quality of castings at 15 mm scale has also helped to fuel their uptake by the wargaming community.

Armies use smaller scales still. The US Army specifies models of the scale 1:285 for its sand table wargaming. There are metal ground vehicles and helicopters in this scale, which is a near "one-quarter-inch-to-six-feet" scale. The continental powers of NATO have developed the similar scale of 1:300, even though metric standardizers really don't like any divisors other than factors of 10, 5, and 2, so maps are not commonly offered in Europe in scales with a "3" in the denominator.

Consumer wargaming has since expanded into fantasy realms, employing scales large enough to be painted in imaginative detail - so called "heroic" 28 mm figures, (roughly 1:64 scale). Firms that produce these make small production lots of white metal.

Alternatively to the commercial models, some modelers also tend to use scraps to achieve home-made warfare models. While it doesn't always involve wargaming, some modelers insert realistic procedures, enabling a certain realism such as firing guns or shell deflection on small scale models.

Engines

[edit]Kits for building an engine model are available, especially for kids. The most popular are the internal combustion, steam, jet, and Stirling model engine. Usually they move using an electric motor or a hand crank, and many of them have a transparent case to show the internal process in action.

Buildings

[edit]

Most hobbyists who build models of buildings do so as part of a diorama to enhance their other models, such as a model railroad or model war machines. As a stand-alone hobby, building models are probably most popular among enthusiasts of construction toys such as Erector, Lego and K'Nex. Famous landmarks such as the Empire State Building, Big Ben and the White House are common subjects. Standard scales have not emerged in this hobby. Model railroaders use railroad scales for their buildings: HO scale (1:87), OO scale (1:76), N scale (1:160), and O scale (1:43). Lego builders use miniland scale (1:20), minifig scale (1:48), and micro scale (1:192)[note 1] Generally, the larger the building, the smaller the scale. Model buildings are commonly made from plastic, foam, balsa wood or paper. Card models are published in the form of a book, and some models are manufactured like 3-D puzzles. Professionally, building models are used by architects and salesmen.

House portrait

[edit]Typically found in 1:50 scale and also called model house, model home or display house, this type of model is usually found in stately homes or specially designed houses. Sometimes this kind of model is commissioned to mark a special date like an anniversary or the completion of the architecture, or these models might be used by salesmen selling homes in a new neighborhood.

Miniatures in contemporary art

[edit]

Miniatures and model kits are used in contemporary art whereby artists use both scratch built miniaturizations or commercially manufactured model kits to construct a dialogue between object and viewer. The role of the artist in this type of miniature is not necessarily to re-create an historical event or achieve naturalist realism, but rather to use scale as a mode of articulation in generating conceptual or theoretical exploration. Political, conceptual, and architectural examples are provided by noted artists such as Bodys Isek Kingelez, Jake and Dinos Chapman (otherwise known as the Chapman Brothers), Ricky Swallow, Shaun Wilson, Sven Christoffersen, or the Psikhelekedana artists from Mozambique, James Casebere, Oliver Boberg, and Daniel Dorall.

See also

[edit]- Autofest City

- Computer-aided design

- Cutaway drawing

- International Plastic Modellers' Society

- Maquette

- Miniature faking

- Miniature figure (disambiguation)

- Miniature park

- Miniature pioneering

- Rail transport modelling scale standards

- Solar System model

- Standard gauge in model railways

- Similitude

- Terrain model

- List of scale model sizes

- List of scale-model industry people

- List of scale model kit manufacturers

References and notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ McCullars, William S. (2001). "Enterprise '64, Part 1". Star Trek Communicator (132): 51.

- ^ Eaglemoss 2013, p. 17.

- ^ Weitekamp 2016, p. 5.

- ^ "Civil Engineering Photos » Search Results » load and confinement box". Archived from the original on 2013-12-13. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- ^ "Research Facilities | Civil and Environmental Engineering at Illinois". Archived from the original on 2013-10-20. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- ^ Harris, H., et al. 1999, p. 62

- ^ Kumar, et al. 1997, p. 1

- ^ "Model train delivers restaurant drinks". Reuters. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- ^ Vytopna Prague Review | Fodor's

- ^ Velinger, Jan (March 14, 2012). "Prague's Výtopna restaurant a hit with families, tourists & train fans". Radio Prague. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- ^ "Benchwork". National Model Railroad Association. 2014-01-07. Archived from the original on 2021-03-23. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

- ^ a b "Model Train Scale and Gauge". Railroad Model Craftsman. White River Productions. December 25, 2016. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- ^ "The German pioneer of N gauge". Hornby Arnold. Hornby Hobbies. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- ^ "Rocket (Black Powder)". PyroGuide. 2010-04-10. Archived from the original on 2007-09-05. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- ^ Morciano, Michele (2003). Classic Waterline Ship Models in the 1:1200/1250 scale. Rome: self published. p. 5.

- ^ Wells, H.G. (1913). LittleWars. London: Frank Palmer. p. 61 "The soldiers used should all be of one size. The best British makers have standardized sizes, and sell infantry and cavalry in exactly proportioned dimension; the infantry being nearly two inches tall. There is a lighter, cheaper make of perhaps an inch and a half that is also available. Foreign-made soldiers are of variable sizes".

Notes

[edit]- ^ In the Lego community, micro scale can refer to anything smaller than minifig scale (1:48), but 1:192 is occasionally set as a standard micro scale. This ratio is arrived at by scaling a person (6 feet) to the height of a Lego brick (3/8 inches). See Bedford, Alan (2005). The Unofficial LEGO Builder's Guide. No Starch Press.

References

[edit]- Crowe, Clayton t.; Elger, Donald F.; Williams, Barbara C.; Roberson, John A. (2010). Engineering Fluid Mechanics. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-0-470-40943-5.

- Eaglemoss (2013), U.S.S. Enterprise NCC-1701 Refit, Eaglemoss Productions Ltd.

- Harris, Harry G.; Sagnis, Gajanan M. (1999). Structural Modeling and Experimental Techniques. CRC Press LLC. ISBN 9780849324697.

- Kumar; et al. (1997). "Pseudodynamic Testing of Scaled Models". J. Struct. Eng. 123 (4): 524–526. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9445(1997)123:4(524).

- Weitekamp, Margaret A. (2016), "Two Enterprises: Star Trek's Iconic Starship As Studio Model and Celebrity", Journal of Popular Film and Television, 44: 2–13, doi:10.1080/01956051.2015.1075955, S2CID 191380605

- "Progress in Scale Modeling, an International Journal (PSMIJ)". Retrieved 19 September 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Crowe, Clayton t.; Elger, Donald F.; Williams, Barbara C.; Roberson, John A. (2010). Engineering Fluid Mechanics. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-0-470-40943-5.

- Harris, Harry G.; Sagnis, Gajanan M. (1999). Structural Modeling and Experimental Techniques. CRC Press LLC. ISBN 9780849324697.

- Lune, Peter van. "FROG Penguin plastic scale model kits 1936 - 1950". Zwolle, The Netherlands, 2017, published by author ISBN 978-90-9030180-8

- Saito, Kozo, ed. (2008). Progress in Scale Modeling. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-8681-6.

- Saito, Kozo; et al. (2015). Progress in Scale Modeling Vol. II. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-10308-2.

External links

[edit]Scale model

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Principles

A scale model is a physical, three-dimensional representation of a real-world object, structure, or system, constructed at a proportionally reduced or enlarged size while preserving geometric similarity in all dimensions to the original subject. This similarity ensures that the model's shape and proportions mirror those of the prototype, allowing it to serve as a reliable analog for visualization, analysis, or experimentation.[6] The core principles underlying scale models derive from similitude theory, which establishes conditions for the model to predictably replicate the prototype's behavior under scaled parameters. Geometric similarity mandates uniform scaling of all linear dimensions by a single factor, typically denoted as for reduced models, where the model's length is the prototype's length divided by . Kinematic similarity requires that motion patterns, including velocities and accelerations, correspond proportionally between model and prototype. Dynamic similarity ensures that the ratios of all relevant forces—such as inertial, gravitational, and elastic—are identical, enabling valid comparisons of responses like stresses or deflections. As a direct consequence of these principles, if the linear scale is , cross-sectional areas scale as and volumes as , which is critical for applications involving fluid dynamics or structural loading.[6][7] Scale models differ in functionality based on design intent: static models lack moving components and focus on fixed representations for display or equilibrium-based testing, such as assessing static loads on a bridge replica, while functional or operational models include articulated parts to simulate dynamic interactions, like aeroelastic effects in wind tunnel setups.[2] Fidelity in scale models denotes the extent of detail and representational accuracy, often varying with the model's purpose—from decorative versions emphasizing aesthetic proportions for educational or promotional use to high-fidelity testable ones engineered for precise validation of physical phenomena, such as structural integrity under load.[8]Scale Ratios and Standards

Scale ratios in scale modeling represent the proportional relationship between the dimensions of a model and its full-sized prototype, typically expressed as a simple fraction in the form 1:n, where n is the scale factor indicating how many times smaller the model is than the original. For instance, a 1:100 scale means every linear dimension of the model is 1/100th the length of the corresponding dimension on the prototype. This convention ensures uniformity across all axes in uniform scaling, maintaining the geometric proportions of the original subject.[9][10] The derivation of model dimensions from prototype measurements follows a straightforward proportional formula: for any linear dimension, the model size equals the prototype dimension divided by the scale factor, or equivalently, model dimension = prototype dimension × (1 / scale factor). To calculate a model's height in a 1:48 scale from a prototype height of 10 meters (approximately 32.8 feet), one would use height_model = 10 m / 48 ≈ 0.208 m (or about 20.8 cm). Conversely, to determine the scale factor when both prototype and model dimensions are known, divide the prototype length by the model length in consistent units (e.g., convert prototype meters to cm by multiplying by 100 if the model is in cm), yielding n in 1:n, rounded to the nearest whole number; for ranges in prototype length, calculate a scale range accordingly. For example, a dinosaur prototype of 10 meters with a 20 cm model yields n = (10 × 100) / 20 = 50, or 1:50 scale.[11] This approach applies to length, width, and other linear features, with areas scaling by the square of the reciprocal factor and volumes by the cube, though linear ratios are the primary focus for dimensional accuracy.[9][12] Industry standards establish specific ratios to promote interoperability and consistency, varying by category and sometimes reflecting metric or imperial origins. In model railroading, the National Model Railroad Association (NMRA) standard S-1.2 defines HO scale as 1:87.1, derived from imperial measurements to approximate 3/8 inch per foot of prototype track. For aircraft modeling, 1:72 is a widely adopted standard, originating from imperial aviation drafting practices where 1 inch represents 6 feet. Variations between metric and imperial systems arise in scales like OO (1:76.2), which aligns closely with metric gauges for European compatibility, compared to the more imperial-oriented HO. These standards facilitate shared accessories and layouts but may require conversions, such as scaling from 1:87 to 1:76.2 by multiplying dimensions by (76.2 / 87.1) ≈ 0.875.[13][10] While uniform scaling preserves shape, non-uniform scales apply different factors to individual dimensions (e.g., compressing height by 1:50 but width by 1:100), which can distort proportions but is occasionally used in specialized engineering models to emphasize certain aspects or fit constraints. Conversion in such cases involves separate calculations per axis, ensuring the model remains functional despite asymmetry.[14] The selection of a scale ratio is influenced by practical considerations, including available space—smaller ratios like 1:144 suit compact displays, while larger ones like 1:48 demand more room; detail visibility, as bigger scales (lower n) permit finer engravings visible to the naked eye; and compatibility with accessories, where adhering to standards like NMRA's ensures seamless integration of tracks, figures, or parts from multiple manufacturers.[15]| Category | Common Scale | Ratio | Notes on Origin/Variation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Railroads | HO | 1:87.1 | Imperial-based; NMRA standard for U.S./global use.[13] |

| Model Railroads | OO | 1:76.2 | Metric approximation; common in UK/Europe.[13] |

| Aircraft | Standard | 1:72 | Imperial (1 inch = 6 feet); widely used for military/commercial planes.[10] |