Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Subatomic particle

View on Wikipedia

In physics, a subatomic particle is a particle smaller than an atom.[1] According to the Standard Model of particle physics, a subatomic particle can be either a composite particle, which is composed of other particles (for example, a baryon, like a proton or a neutron, composed of three quarks; or a meson, composed of two quarks), or an elementary particle, which is not composed of other particles (for example, quarks; or electrons, muons, and tau particles, which are called leptons).[2] Particle physics and nuclear physics study these particles and how they interact.[3] Most force-carrying particles like photons or gluons are called bosons and, although they have quanta of energy, do not have rest mass or discrete diameters (other than pure energy wavelength) and are unlike the former particles that have rest mass and cannot overlap or combine which are called fermions. The W and Z bosons, however, are an exception to this rule and have relatively large rest masses at approximately 80 GeV/c2 and 90 GeV/c2 respectively.

Experiments show that light could behave like a stream of particles (called photons) as well as exhibiting wave-like properties. This led to the concept of wave–particle duality to reflect that quantum-scale particles behave both like particles and like waves; they are occasionally called wavicles to reflect this.[4]

Another concept, the uncertainty principle, states that some of their properties taken together, such as their simultaneous position and momentum, cannot be measured exactly.[5] Interactions of particles in the framework of quantum field theory are understood as creation and annihilation of quanta of corresponding fundamental interactions. This blends particle physics with field theory.

Even among particle physicists, the exact definition of a particle has diverse descriptions. These professional attempts at the definition of a particle include:[6]

- A particle is a collapsed wave function

- A particle is an excitation of a quantum field

- A particle is an irreducible representation of the Poincaré group

- A particle is an observed thing

| Subatomic particle | Symbol | Type | Location in atom | Charge [e] |

Mass [Da] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| proton | p+ | composite | nucleus | +1 | ≈ 1 |

| neutron | n0 | composite | nucleus | 0 | ≈ 1 |

| electron | e− | elementary | shells | −1 | ≈ 1/2000 |

Classification

[edit]By composition

[edit]Subatomic particles are either "elementary", i.e. not made of multiple other particles, or "composite" and made of more than one elementary particle bound together.

The elementary particles of the Standard Model are:[7]

- Six "flavors" of quarks: up, down, strange, charm, bottom, and top;

- Six types of leptons: electron, electron neutrino, muon, muon neutrino, tau, tau neutrino;

- Twelve gauge bosons (force carriers): the photon of electromagnetism, the three W and Z bosons of the weak force, and the eight gluons of the strong force;

- The Higgs boson.

All of these have now been discovered through experiments, with the latest being the top quark (1995), tau neutrino (2000), and Higgs boson (2012).

Various extensions of the Standard Model predict the existence of an elementary graviton particle and many other elementary particles, but none have been discovered as of 2021.

Hadrons

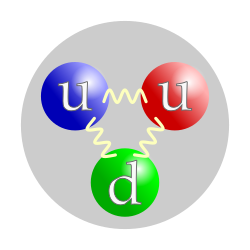

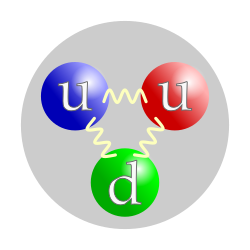

[edit]The word hadron comes from Greek and was introduced in 1962 by Lev Okun.[8] Nearly all composite particles contain multiple quarks (and/or antiquarks) bound together by gluons (with a few exceptions with no quarks, such as positronium and muonium). Those containing few (≤ 5) quarks (including antiquarks) are called hadrons. Due to a property known as color confinement, quarks are never found singly but always occur in hadrons containing multiple quarks. The hadrons are divided by number of quarks (including antiquarks) into the baryons containing an odd number of quarks (almost always 3), of which the proton and neutron (the two nucleons) are by far the best known; and the mesons containing an even number of quarks (almost always 2, one quark and one antiquark), of which the pions and kaons are the best known.

Except for the proton and neutron, all other hadrons are unstable and decay into other particles in microseconds or less. A proton is made of two up quarks and one down quark, while the neutron is made of two down quarks and one up quark. These commonly bind together into an atomic nucleus, e.g. a helium-4 nucleus is composed of two protons and two neutrons. Most hadrons do not live long enough to bind into nucleus-like composites; those that do (other than the proton and neutron) form exotic nuclei.

By statistics

[edit]

Any subatomic particle, like any particle in the three-dimensional space that obeys the laws of quantum mechanics, can be either a boson (with integer spin) or a fermion (with odd half-integer spin).

In the Standard Model, all the elementary fermions have spin 1/2, and are divided into the quarks which carry color charge and therefore feel the strong interaction, and the leptons which do not. The elementary bosons comprise the gauge bosons (photon, W and Z, gluons) with spin 1, while the Higgs boson is the only elementary particle with spin zero.

The hypothetical graviton is required theoretically to have spin 2, but is not part of the Standard Model. Some extensions such as supersymmetry predict additional elementary particles with spin 3/2, but none have been discovered as of 2023.

Due to the laws for spin of composite particles, the baryons (3 quarks) have spin either 1/2 or 3/2 and are therefore fermions; the mesons (2 quarks) have integer spin of either 0 or 1 and are therefore bosons.

By mass

[edit]In special relativity, the energy of a particle at rest equals its mass times the speed of light squared, E = mc 2. That is, mass can be expressed in terms of energy and vice versa. If a particle has a frame of reference in which it lies at rest, then it has a positive rest mass and is referred to as massive.

All composite particles are massive. Baryons (meaning "heavy") tend to have greater mass than mesons (meaning "intermediate"), which in turn tend to be heavier than leptons (meaning "lightweight"), but the heaviest lepton (the tau particle) is heavier than the two lightest flavours of baryons (nucleons). It is also certain that any particle with an electric charge is massive.

When originally defined in the 1950s, the terms baryons, mesons and leptons referred to masses; however, after the quark model became accepted in the 1970s, it was recognised that baryons are composites of three quarks, mesons are composites of one quark and one antiquark, while leptons are elementary and are defined as the elementary fermions with no color charge.

All massless particles (particles whose invariant mass is zero) are elementary. These include the photon and gluon, although the latter cannot be isolated.

By decay

[edit]Most subatomic particles are not stable. All leptons, as well as baryons decay by either the strong force or weak force (except for the proton). Protons are not known to decay, although whether they are "truly" stable is unknown, as some very important Grand Unified Theories (GUTs) actually require it. The μ and τ muons, as well as their antiparticles, decay by the weak force. Neutrinos (and antineutrinos) do not decay, but a related phenomenon of neutrino oscillations is thought to exist even in vacuums. The electron and its antiparticle, the positron, are theoretically stable due to charge conservation unless a lighter particle having magnitude of electric charge ≤ e exists (which is unlikely). Its charge is not shown yet.

Other properties

[edit]All observable subatomic particles have their electric charge an integer multiple of the elementary charge. The Standard Model's quarks have "non-integer" electric charges, namely, multiple of 1/3 e, but quarks (and other combinations with non-integer electric charge) cannot be isolated due to color confinement. For baryons, mesons, and their antiparticles the constituent quarks' charges sum up to an integer multiple of e.

Through the work of Albert Einstein, Satyendra Nath Bose, Louis de Broglie, and many others, current scientific theory holds that all particles also have a wave nature.[9] This has been verified not only for elementary particles but also for compound particles like atoms and even molecules. In fact, according to traditional formulations of non-relativistic quantum mechanics, wave–particle duality applies to all objects, even macroscopic ones; although the wave properties of macroscopic objects cannot be detected due to their small wavelengths.[10]

Interactions between particles have been scrutinized for many centuries, and a few simple laws underpin how particles behave in collisions and interactions. The most fundamental of these are the laws of conservation of energy and conservation of momentum, which let us make calculations of particle interactions on scales of magnitude that range from stars to quarks.[11] These are the prerequisite basics of Newtonian mechanics, a series of statements and equations in Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, originally published in 1687.

Dividing an atom

[edit]The negatively charged electron has a mass of about 1/1836 of that of a hydrogen atom. The remainder of the hydrogen atom's mass comes from the positively charged proton. The atomic number of an element is the number of protons in its nucleus. Neutrons are neutral particles having a mass slightly greater than that of the proton. Different isotopes of the same element contain the same number of protons but different numbers of neutrons. The mass number of an isotope is the total number of nucleons (neutrons and protons collectively).

Chemistry concerns itself with how electron sharing binds atoms into structures such as crystals and molecules. The subatomic particles considered important in the understanding of chemistry are the electron, the proton, and the neutron. Nuclear physics deals with how protons and neutrons arrange themselves in nuclei. The study of subatomic particles, atoms and molecules, and their structure and interactions, requires quantum mechanics. Analyzing processes that change the numbers and types of particles requires quantum field theory. The study of subatomic particles per se is called particle physics. The term high-energy physics is nearly synonymous to "particle physics" since creation of particles requires high energies: it occurs only as a result of cosmic rays, or in particle accelerators. Particle phenomenology systematizes the knowledge about subatomic particles obtained from these experiments.[12]

History

[edit]The term "subatomic particle" is largely a retronym of the 1960s, used to distinguish a large number of baryons and mesons (which comprise hadrons) from particles that are now thought to be truly elementary. Before that hadrons were usually classified as "elementary" because their composition was unknown.

A list of important discoveries follows:

| Particle | Composition | Theorized | Discovered | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| electron e− |

elementary (lepton) | G. Johnstone Stoney (1874)[13] | J. J. Thomson (1897)[14] | Minimum unit of electrical charge, for which Stoney suggested the name in 1891.[15] First subatomic particle to be identified.[16] |

| alpha particle α | composite (atomic nucleus) | never | Ernest Rutherford (1899)[17] | Proven by Rutherford and Thomas Royds in 1907 to be helium nuclei. Rutherford won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1908 for this discovery.[18] |

| photon γ | elementary (quantum) | Max Planck (1900)[19] | Albert Einstein (1905)[20] | Necessary to solve the thermodynamic problem of black-body radiation. |

| proton p | composite (baryon) | William Prout (1815)[21] | Ernest Rutherford (1919, named 1920)[22][23] | The nucleus of 1 H. |

| neutron n | composite (baryon) | Ernest Rutherford (c.1920[24]) | James Chadwick (1932) [25] | The second nucleon. |

| antiparticles | Paul Dirac (1928)[26] | Carl D. Anderson (e+ , 1932) |

Revised explanation uses CPT symmetry. | |

| pions π | composite (mesons) | Hideki Yukawa (1935) | César Lattes, Giuseppe Occhialini, Cecil Powell (1947) | Explains the nuclear force between nucleons. The first meson (by modern definition) to be discovered. |

| muon μ− |

elementary (lepton) | never | Carl D. Anderson (1936)[27] | Called a "meson" at first; but today classed as a lepton. |

| tau τ− |

elementary (lepton) | Antonio Zichichi (1960) [28] | Martin Lewis Perl (1975) | |

| kaons K | composite (mesons) | never | G. D. Rochester, C. C. Butler (1947)[29] | Discovered in cosmic rays. The first strange particle. |

| lambda baryons Λ | composite (baryons) | never | University of Melbourne (Λ0 , 1950)[30] |

The first hyperon discovered. |

| neutrino ν | elementary (lepton) | Wolfgang Pauli (1930), named by Enrico Fermi | Clyde Cowan, Frederick Reines (ν e, 1956) |

Solved the problem of energy spectrum of beta decay. |

| quarks (u, d, s) |

elementary | Murray Gell-Mann, George Zweig (1964) | No particular confirmation event for the quark model. | |

| charm quark c | elementary (quark) | Sheldon Glashow, John Iliopoulos, Luciano Maiani (1970) | B. Richter, S. C. C. Ting (J/ψ, 1974) | |

| bottom quark b | elementary (quark) | Makoto Kobayashi, Toshihide Maskawa (1973) | Leon M. Lederman (ϒ, 1977) | |

| gluons | elementary (quantum) | Harald Fritzsch, Murray Gell-Mann (1972)[31] | DESY (1979) | |

| weak gauge bosons W± , Z0 |

elementary (quantum) | Sheldon Glashow, Steven Weinberg, Abdus Salam (1968)[32][33][34] | CERN (1983) | Properties verified through the 1990s. |

| top quark t | elementary (quark) | Makoto Kobayashi, Toshihide Maskawa (1973)[35] | Fermilab (1995)[36] | Does not hadronize, but is necessary to complete the Standard Model. |

| Higgs boson | elementary (quantum) | Peter Higgs (1964)[37][38] | CERN (2012)[39] | Only known spin zero elementary particle.[40] |

| tetraquark | composite | ? | Zc(3900), 2013, yet to be confirmed as a tetraquark | A new class of hadrons. |

| pentaquark | composite | ? | Yet another class of hadrons. As of 2019[update] several are thought to exist. | |

| graviton | elementary (quantum) | Albert Einstein (1916) | Interpretation of a gravitational wave as particles is controversial.[41] | |

| magnetic monopole | elementary (unclassified) | Paul Dirac (1931)[42] | hypothetical[43]: 25 | |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Subatomic particles". NTD. Archived from the original on 16 February 2014. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- ^ Bolonkin, Alexander (2011). Universe, Human Immortality and Future Human Evaluation. Elsevier. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-12-415801-6.

- ^ Fritzsch, Harald (2005). Elementary Particles. World Scientific. pp. 11–20. ISBN 978-981-256-141-1.

- ^ Hunter, Geoffrey; Wadlinger, Robert L. P. (August 23, 1987). Honig, William M.; Kraft, David W.; Panarella, Emilio (eds.). Quantum Uncertainties: Recent and Future Experiments and Interpretations. Springer US. pp. 331–343. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-5386-7_18.

The finite-field model of the photon is both a particle and a wave, and hence we refer to it by Eddington's name "wavicle".

- ^ Heisenberg, W. (1927). "Über den anschaulichen Inhalt der quantentheoretischen Kinematik und Mechanik". Zeitschrift für Physik (in German). 43 (3–4): 172–198. Bibcode:1927ZPhy...43..172H. doi:10.1007/BF01397280. S2CID 122763326.

- ^ "What is a Particle?". 12 November 2020.

- ^ Cottingham, W. N.; Greenwood, D.A. (2007). An introduction to the standard model of particle physics. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-521-85249-4.

- ^ Okun, Lev (1962). "The theory of weak interaction". Proceedings of 1962 International Conference on High-Energy Physics at CERN. International Conference on High-Energy Physics (plenary talk). CERN, Geneva, CH. p. 845. Bibcode:1962hep..conf..845O.

- ^ Greiner, Walter (2001). Quantum Mechanics: An Introduction. Springer. p. 29. ISBN 978-3-540-67458-0.

- ^

Eisberg, R. & Resnick, R. (1985). Quantum Physics of Atoms, Molecules, Solids, Nuclei, and Particles (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 59–60. ISBN 978-0-471-87373-0.

For both large and small wavelengths, both matter and radiation have both particle and wave aspects. [...] But the wave aspects of their motion become more difficult to observe as their wavelengths become shorter. [...] For ordinary macroscopic particles the mass is so large that the momentum is always sufficiently large to make the de Broglie wavelength small enough to be beyond the range of experimental detection, and classical mechanics reigns supreme.

- ^ Newton, Isaac (1687). "Axioms or Laws of Motion". The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy. England.

- ^ Taiebyzadeh, Payam (2017). String Theory: A Unified Theory and Inner Dimension Of Elementary Particles (Baz Dahm). Iran: Shamloo Publications. ISBN 978-6-00-116684-6.

- ^ Stoney, G. Johnstone (1881). "LII. On the physical units of nature". The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 11 (69): 381–390. doi:10.1080/14786448108627031. ISSN 1941-5982.

- ^ Thomson, J. J. (1897). "Cathode Rays". The Electrician. 39: 104.

- ^ Klemperer, Otto (1959). "Electron physics: The physics of the free electron". Physics Today. 13 (6): 64–66. Bibcode:1960PhT....13R..64K. doi:10.1063/1.3057011.

- ^ Alfred, Randy (April 30, 2012). "April 30, 1897: J.J. Thomson Announces the Electron ... Sort Of". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 2022-08-22.

- ^ Rutherford, E. (1899). "VIII. Uranium radiation and the electrical conduction produced by it". The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 47 (284): 109–163. doi:10.1080/14786449908621245. ISSN 1941-5982.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1908". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 2022-08-22.

- ^ Klein, Martin J. (1961). "Max Planck and the beginnings of the quantum theory". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 1 (5): 459–479. doi:10.1007/BF00327765. ISSN 0003-9519. S2CID 121189755.

- ^ Einstein, Albert (1905). "Über einen die Erzeugung und Verwandlung des Lichtes betreffenden heuristischen Gesichtspunkt". Annalen der Physik (in German). 322 (6): 132–148. Bibcode:1905AnP...322..132E. doi:10.1002/andp.19053220607.

- ^ Lederman, Leon (1993). The God Particle. Delta. ISBN 978-0-385-31211-0.

- ^ Rutherford, Ernest (1920). "The Stability of Atoms". Proceedings of the Physical Society of London. 33 (1): 389–394. Bibcode:1920PPSL...33..389R. doi:10.1088/1478-7814/33/1/337. ISSN 1478-7814.

- ^ There was early debate on what to name the proton as seen in the follow commentary articles by Soddy 1920 and Lodge 1920.

- ^ Rutherford, Ernest (1920). "Bakerian Lecture: Nuclear constitution of atoms". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character. 97 (686): 374–400. Bibcode:1920RSPSA..97..374R. doi:10.1098/rspa.1920.0040. ISSN 0950-1207.

- ^ Chadwick, J. (1932). "The existence of a neutron". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character. 136 (830): 692–708. Bibcode:1932RSPSA.136..692C. doi:10.1098/rspa.1932.0112. ISSN 0950-1207.

- ^ Dirac, P. A. M. (1928). "The quantum theory of the electron". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character. 117 (778): 610–624. Bibcode:1928RSPSA.117..610D. doi:10.1098/rspa.1928.0023. ISSN 0950-1207.

- ^ Anderson, Carl D.; Neddermeyer, Seth H. (1936-08-15). "Cloud Chamber Observations of Cosmic Rays at 4300 Meters Elevation and Near Sea-Level". Physical Review. 50 (4): 263–271. Bibcode:1936PhRv...50..263A. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.50.263. ISSN 0031-899X.

- ^ Zichichi, A. (1996). "Foundations of sequential heavy lepton searches" (PDF). In Newman, H.B.; Ypsilantis, T. (eds.). History of Original Ideas and Basic Discoveries in Particle Physics. NATO ASI Series (Series B: Physics). Vol. 352. Boston, MA: Springer. pp. 227–275.

- ^ Rochester, G. D.; Butler, C. C. (December 1947). "Evidence for the Existence of New Unstable Elementary Particles". Nature. 160 (4077): 855–857. Bibcode:1947Natur.160..855R. doi:10.1038/160855a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 18917296. S2CID 33881752.

- ^ Some sources such as "The Strange Quark". indicate 1947.

- ^ Fritzsch, Harald; Gell-Mann, Murray (1972). "Current algebra: Quarks and what else?". EConf. C720906V2: 135–165. arXiv:hep-ph/0208010.

- ^ Glashow, Sheldon L. (1961). "Partial-symmetries of weak interactions". Nuclear Physics. 22 (4): 579–588. Bibcode:1961NucPh..22..579G. doi:10.1016/0029-5582(61)90469-2.

- ^ Weinberg, Steven (1967). "A Model of Leptons". Physical Review Letters. 19 (21): 1264–1266. Bibcode:1967PhRvL..19.1264W. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.19.1264.

- ^ Salam, Abdus (1968). "Weak and electromagnetic interactions". Selected Papers of Abdus Salam. World Scientific Series in 20th Century Physics. Vol. 680519. pp. 367–377. doi:10.1142/9789812795915_0034. ISBN 978-981-02-1662-7.

- ^ Kobayashi, Makoto; Maskawa, Toshihide (1973). "C P Violation in the Renormalizable Theory of Weak Interaction". Progress of Theoretical Physics. 49 (2): 652–657. Bibcode:1973PThPh..49..652K. doi:10.1143/PTP.49.652. hdl:2433/66179. ISSN 0033-068X. S2CID 14006603.

- ^ Abachi, S.; Abbott, B.; Abolins, M.; Acharya, B. S.; Adam, I.; Adams, D. L.; Adams, M.; Ahn, S.; Aihara, H.; Alitti, J.; Álvarez, G.; Alves, G. A.; Amidi, E.; Amos, N.; Anderson, E. W. (1995-04-03). "Observation of the Top Quark". Physical Review Letters. 74 (14): 2632–2637. arXiv:hep-ex/9503003. Bibcode:1995PhRvL..74.2632A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.74.2632. hdl:1969.1/181526. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 10057979. S2CID 42826202.

- ^ "Letters from the Past – A PRL Retrospective". Physical Review Letters. 2014-02-12. Retrieved 2022-08-22.

- ^ Higgs, Peter W. (1964-10-19). "Broken Symmetries and the Masses of Gauge Bosons". Physical Review Letters. 13 (16): 508–509. Bibcode:1964PhRvL..13..508H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.13.508. ISSN 0031-9007.

- ^ Aad, G.; Abajyan, T.; Abbott, B.; Abdallah, J.; Abdel Khalek, S.; Abdelalim, A.A.; Abdinov, O.; Aben, R.; Abi, B.; Abolins, M.; AbouZeid, O.S.; Abramowicz, H.; Abreu, H.; Acharya, B.S.; Adamczyk, L. (2012). "Observation of a new particle in the search for the Standard Model Higgs boson with the ATLAS detector at the LHC". Physics Letters B. 716 (1): 1–29. arXiv:1207.7214. Bibcode:2012PhLB..716....1A. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2012.08.020. S2CID 119169617.

- ^ Jakobs, Karl; Zanderighi, Giulia (2024-02-05). "The profile of the Higgs boson: status and prospects". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 382 (2266). arXiv:2311.10346. Bibcode:2024RSPTA.38230087J. doi:10.1098/rsta.2023.0087. ISSN 1364-503X. PMID 38104616.

- ^ Moskowitz, Clara (March 31, 2014). "Multiverse Controversy Heats Up over Gravitational Waves". Scientific American. Retrieved 2022-08-22.

- ^ Dirac, Paul A. M. (1931). "Quantised singularities in the electromagnetic field". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character. 133 (821): 60–72. Bibcode:1931RSPSA.133...60D. doi:10.1098/rspa.1931.0130. ISSN 0950-1207.

- ^ Navas, S.; Amsler, C.; Gutsche, T.; Hanhart, C.; Hernández-Rey, J. J.; Lourenço, C.; Masoni, A.; Mikhasenko, M.; Mitchell, R. E.; Patrignani, C.; Schwanda, C.; Spanier, S.; Venanzoni, G.; Yuan, C. Z.; Agashe, K. (2024-08-01). "Review of Particle Physics". Physical Review D. 110 (3) 030001. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.110.030001. hdl:20.500.11850/695340. ISSN 2470-0010.

Further reading

[edit]General readers

[edit]- Feynman, Richard P.; Weinberg, Steven, eds. (2001). Elementary particles and the laws of physics: the 1986 Dirac memorial lectures (Repr ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-65862-1.

- Greene, Brian (2003). The elegant universe: superstrings, hidden dimensions, and the quest for the ultimate theory. New York; London, England: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-05858-1.

- Oerter, Robert (2006). The theory of almost everything: the Standard Model, the unsung triumph of modern physics. New York, New York: Pi Press. ISBN 978-0-452-28786-0.

- Schumm, Bruce A. (2004). Deep down things: the breathtaking beauty of particle physics. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-7971-5.

- Veltman, Martinus (2003). Facts and mysteries in elementary particle physics. River Edge, New Jersey: World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-238-148-4.

Textbooks

[edit]- Coughlan, Guy D.; Dodd, J. E.; Gripaios, Ben M. (2006). The ideas of particle physics: an introduction for scientists (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-67775-2. An undergraduate text for those not majoring in physics.

- Griffiths, David J. (2007). Introduction to elementary particles. Weinheim: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-60386-3.

- Kane, Gordon L. (2017). Modern elementary particle physics (2nd ed.). Cambridge, England, United Kingdom; New York, New York, USA: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-16508-3.