Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

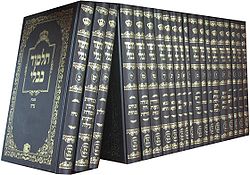

Talmud

View on Wikipedia

| Rabbinic literature | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

| Talmudic literature | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Halakhic Midrash | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Aggadic Midrash | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Targum | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Judaism |

|---|

|

The Talmud (/ˈtɑːlmʊd, -məd, ˈtæl-/; Hebrew: תַּלְמוּד, romanized: Talmūḏ, lit. 'study, learning, teaching, instruction') is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism second in authority only to the Jewish Bible (Tanakh), whose core is the Torah.[2][3][4] It is the primary source of Jewish religious law (halakha) and Jewish theology.[5][6][7][8] It consists of the Oral Torah compiled in the Mishnah, and its commentaries, the Gemara. It records the teachings, opinions and disagreements of thousands of rabbis on a variety of subjects, including halakha, Jewish ethics, philosophy, customs, history, and folklore, and many other topics. Until the Haskalah era in the 18th and 19th centuries (sometimes called the "Jewish Enlightenment"), the Talmud was the centerpiece of cultural life in nearly all Jewish communities, and was foundational to "all Jewish thought and aspirations", serving also as "the guide for the daily life" of Jews.[9]

The Talmud is a commentary on the Mishnah.[a][10] This text is made up of 63 tractates, each covering one subject area. The language of the Talmud is Jewish Babylonian Aramaic. Talmudic tradition emerged and was compiled between the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE and the Arab conquest in the early seventh century.[11] Traditionally, it is thought that the Talmud itself was compiled by Rav Ashi and Ravina II around 500 CE, although it is more likely that this happened in the middle of the sixth century.[12]

The word 'Talmud' commonly refers to the Babylonian Talmud (Talmud Bavli) and not the earlier Jerusalem Talmud (Talmud Yerushalmi).[13] The Babylonian Talmud is the more extensive of the two and is considered the more important.[14]

Various collections of quotes from the Talmud circulate on the Internet and elsewhere, purporting to show that the Talmud promotes immoral practices and regards non-Jews as lesser beings. Some of these quotes are genuine (the Talmud dates from the early Middle Ages), some have been taken out of context in a way that changes their meaning and many are outright fakes.

Etymology

[edit]Talmud translates as "instruction, learning", from the Semitic root lmd, meaning "teach, study".[15]

The two Talmuds

[edit]In antiquity, the two major centres of Jewish scholarship were located in Galilee and Babylonia. A Talmud was compiled in each of these regional centres. The earlier of the two compilations took place in Galilee, either in the late fourth or early fifth century, and it came to be known as the Jerusalem Talmud (or Talmud Yerushalmi). Later on, and likely some time in the sixth century, the Babylonian Talmud was compiled (Talmud Bavli). This later Talmud is usually what is being referred to when the word "Talmud" is used without qualification.[16] Traditions of the Jerusalem Talmud and its sages had a significant influence on the milieu out of which the Babylonian Talmud arose.[17][18]

Jerusalem Talmud

[edit]

The Jerusalem Talmud (Talmud Yerushalmi) is known by several other names, including the Palestinian Talmud[19] (which is more accurate, as it was not compiled in Jerusalem), or the Talmuda de-Eretz Yisrael ("Talmud of the Land of Israel").[20] The Jerusalem Talmud was a written codification of oral tradition that had been circulating for centuries[21] and represents a compilation of scholastic teachings and analyses on the Mishnah (especially those concerning agricultural laws) found across regional centres of the Land of Israel now known as the Academies in Galilee (principally those of Tiberias, Sepphoris, and Caesarea). It is written largely in Jewish Palestinian Aramaic, a Western Aramaic language that differs from its Babylonian counterpart.[22][23] The compilation was likely made between the late fourth to the first half of the fifth century.[24][25]

Despite its incomplete state, the Jerusalem Talmud remains an indispensable source of knowledge of the development of the Jewish Law in the Holy Land. It was also an important primary source for the study of the Babylonian Talmud by the Kairouan school of Chananel ben Chushiel and Nissim ben Jacob, with the result that opinions ultimately based on the Jerusalem Talmud found their way into both the Tosafot and the Mishneh Torah of Maimonides. Ethical maxims contained in the Jerusalem Talmud are scattered and interspersed in the legal discussions throughout the several treatises, many of which differ from those in the Babylonian Talmud.[26]

Babylonian Talmud

[edit]

The Babylonian Talmud (Talmud Bavli) consists of documents compiled over the period of late antiquity (3rd to 6th centuries).[27] During this time, the most important of the Jewish centres in Mesopotamia, a region called "Babylonia" in Jewish sources (see Talmudic academies in Babylonia) and later known as Iraq, were Nehardea, Nisibis (modern Nusaybin), Mahoza (al-Mada'in, just to the south of what is now Baghdad), Pumbedita (near present-day al Anbar Governorate), and the Sura Academy, probably located about 60 km (37 mi) south of Baghdad.[28]

The Babylonian Talmud comprises the culmination of centuries of analysis and dialectic surrounding the Mishnah in the Talmudic Academies in Babylonia. According to tradition, the foundations of this process of analysis were laid by Abba Arika (175–247), a disciple of Judah ha-Nasi. Tradition ascribes the compilation of the Babylonian Talmud in its present form to two Babylonian sages, Rav Ashi and Ravina II.[29] Rav Ashi was president of the Sura Academy from 375 to 427. In this time, he began the creation of the written Talmud, a written project passed onto and completed by Ravina, the final Amoraic expounder. Accordingly, the latest traditional date for the Talmud is often placed at 475, the year Ravina died. However, even on traditional views, a final redaction is still thought to have been made by the Savoraim ("reasoners", "considerers") in the sixth century.[30][31]

Comparison

[edit]Unlike the Western Aramaic dialect of the Jerusalem Talmud, the Babylonian Talmud has a Babylonian Aramaic dialect. The Jerusalem is also more fragmentary (and difficult to read) due to a less complete redactional process.[32] Discussions in the Babylonian Talmud are more discursive, rambling, rely more on anecdote and argumentation by syllogism and induction, whereas those in the Jerusalem Talmud are more factual and apply argumentation through logical deduction. The Babylonian Talmud is much longer, with about 2.5 million words in total. Proportionally, more Babylonian material is non-legal (aggadah), constituting a third of its material, compared to a sixth of the Jerusalem.[33] The Babylonian Talmud has received significantly more interest and coverage from commentators.[34]

Maimonides drew influence from both Babylonian and Jerusalem Talmuds, although he favored the latter over the former when principles between them conflicted.[35] As the Palestinian Jewish community declined in influence and the Babylonian community became the intellectual center of the Diaspora, the Babylonian Talmud became the more widely accepted and popular version.[33] Whereas the Jerusalem Talmud only includes the opinions of Israelite rabbis (the Ma'arava), the Babylonian Talmud also includes Babylonian authorities, in addition to later authorities because of its later date. As such, it is regarded as more comprehensive.[36][37]

Neither covers the entire Mishnah. For example, the Babylonian commentary only covers 37 of 63 Mishnaic tractates. In particular:

- The Jerusalem Talmud covers all the tractates of Zeraim, while the Babylonian Talmud covers only tractate Berachot. This might be because the agricultural concerns of Zeraim were not as notable in Babylonia.[38] As the Jerusalem Talmud was produced in the Land of Israel, it consequently has a greater interest in Israelite geography.

- Unlike the Babylonian Talmud, the Jerusalem Talmud does not cover the Mishnaic Kodashim, which deals with sacrificial rites and laws pertaining to the Temple. A good explanation for this is not available, although there is some evidence that a now-lost commentary on this text once existed in the Jerusalem Talmud.

- In both Talmuds, only one tractate of Tohorot (ritual purity laws) is examined, that of the menstrual laws (Niddah).

Structure

[edit]The structure of the Talmud follows that of the Mishnah, divided into Six Orders (known as the Shisha Sedarim, or Shas) of general subject matter are divided into 63 tractates (masekhtot; singular: masekhet) of more focused subject compilations, though not all tractates have Gemara. Each tractate is divided into chapters (perakim; singular: perek), 517 in total, that are both numbered according to the Hebrew alphabet and given names, usually using the first one or two words in the first Mishnah. A perek may continue over several (up to tens of) pages. Each perek will contain several mishnayot.[39]

Mishnah

[edit]The Mishnah is a compilation of legal opinions and debates. Statements in the Mishnah are typically terse, recording brief opinions of the rabbis debating a subject; or recording only an unattributed ruling, apparently representing a consensus view. The rabbis recorded in the Mishnah are known as the Tannaim (literally, "repeaters", or "teachers"). These tannaim—rabbis of the second century CE—"who produced the Mishnah and other tannaic works, must be distinguished from the rabbis of the third to fifth centuries, known as amoraim (literally, "speakers"), who produced the two Talmudim and other amoraic works".[40]

Since it sequences its laws by subject matter instead of by biblical context, the Mishnah discusses individual subjects more thoroughly than the Midrash, and it includes a much broader selection of halakhic subjects than the Midrash. The Mishnah's topical organization thus became the framework of the Talmud as a whole. But not every tractate in the Mishnah has a corresponding Gemara. Also, the order of the tractates in the Talmud differs in some cases from that in the Mishnah.

Gemara

[edit]The Gemara constitutes the commentary portion of the Talmud. The Mishnah, and its commentary (the Gemara), together constitute the Talmud. This commentary arises from a longstanding tradition of rabbis analyzing, debating, and discussing the Mishnah ever since it was compiled. The rabbis who participated in the process that produced this commentarial tradition are known as the Amoraim.[41] Each discussion is presented in a self-contained, edited passage known as a sugya.[42]

Much of the Gemara is legal in nature. Each analysis begins with a Mishnaic legal statement. With each sugya, the statement may be analyzed and compared with other statements. This process can be framed as an exchange between two (often anonymous, possibly metaphorical) disputants, termed the makshan (questioner) and tartzan (answerer). Gemara also commonly tries to find the correct biblical basis for a given law in the Mishnah as well as the logical process that connects the biblical to the Mishnaic tradition. This process was known as talmud, long before the "Talmud" itself became a text.[43]

In addition, the Gemara contains a wide range of narratives, homiletical or exegetical passages, sayings, and other non-legal content, termed aggadah. A story told in a sugya of the Babylonian Talmud may draw upon the Mishnah, the Jerusalem Talmud, midrash, and other sources.[44]

Baraita

[edit]The traditions that the Gemara comments on are not limited to what is found in the Mishnah, but the Baraita as well (a term that broadly designates Oral Torah traditions that did not end up in the Mishnah). The baraitot cited in the Gemara are often quotations from the Tosefta (a tannaitic compendium of halakha parallel to the Mishnah) and the Midrash halakha (specifically Mekhilta, Sifra and Sifre). Some baraitot, however, are known only through traditions cited in the Gemara, and are not part of any other collection.[45]

Minor tractates

[edit]In addition to the Six Orders, the Talmud contains a series of short treatises of a later date, usually printed at the end of Seder Nezikin. These are not divided into Mishnah and Gemara.

Language

[edit]The work is largely in Jewish Babylonian Aramaic, although quotations in the Gemara of the Mishnah, the Baraitas and Tanakh appear in Mishnaic or Biblical Hebrew.[46] Some other dialects of Aramaic occur in quotations of other older works, like the Megillat Taanit. The reason why earlier texts occur in Hebrew, and later texts in Aramaic, is because of the adoption of the latter (which was the spoken vernacular) by rabbinic circles during the period of the Amoraim (rabbis cited in the Gemara) beginning around the year 200.[47] A second Aramaic dialect is used in Nedarim, Nazir, Temurah, Keritot, and Me'ilah; the second is closer in style to the Targum.[48]

Manuscripts

[edit]The only complete manuscript of the Talmud, Munich Codex Hebraica 95, dates from 1342 (view scan). Other manuscripts of the Talmud include:[49]

- Cairo Genizah fragments[50]

- Date: earliest ones from the late 7th or 8th century

- Context: earliest manuscript fragment of the Talmud of any kind

- Ms. Oxford 2673[51]

- Date: 1123

- Context: Contains a significant portion of tractate Keritot; earliest Talmudic manuscript whose precise date is known

- Ms. Firenze 7

- Date: 1177

- Context: earliest Talmudic whose precise date is known and contains complete tractates

- MS JTS Rab. 15[52]

- Date: 1290

- Location: Spain

- Bologna, Archivio di Stato Fr. ebr. 145[49]

- Date: 13th century

- Vatican 130[49]

- Date: January 14, 1381

- Oxford Opp. 38 (368)[49]

- Date: 14th century

- Arras 889[49]

- Date: 14th century

- Vatican 114[53]

- Date: 14th century

- Vatican 140[49]

- Date: late 14th century

- Bazzano, Archivio Storico Comunale Fr. ebr. 21[49]

- Date: 12th–15th centuries

- St. Petersburg, RNL Evr. I 187[49]

- Date: 13th or 15th century

Dating

[edit]Premodern estimates

[edit]The Talmud itself (BM 86a) incorporates a statement that "Ravina and Rav Ashi were the end of instruction". Likewise, Sherira ben Hanina writes that "instruction ended" with the death of Ravina II in 811 SE (500 CE), and "the Talmud stopped with the end of instruction in the days of Rabbah Jose (fl. 476-514)".[29] Seder Olam Zutta records that "in 811 SE (500 CE) Ravina the End of Instruction died, and the Talmud was stopped", and the same text is found in Codex Gaster 83.[54] Another medieval chronicle records that "On Wednesday, 13 Kislev, 811 SE (500 CE), Ravina the End of Instruction son of Rav Huna died, and the Talmud stopped."[54] Abraham ibn Daud gives 821 SE (510 CE) for the same event, and Joseph ibn Tzaddik writes that "Mareimar and Mar bar Rav Assi et al. completed the Babylonian Talmud . . . in 4265 AM (505 CE)".[54] Nachmanides dated the Talmud's compilation to "400 years after the Destruction", which is 470 CE if taken as exact.[55] According to Moses da Rieti, "Ravina and Rav Ashi compiled the Talmud but they did not complete it, and Mar bar Rav Ashi and Mareimar et al. sealed it in the days of Rabbah Jose . . . he headed the academy for 38 years after succeeding Ravina, until 4274 AM (514 CE), and in his days the Babylonian Talmud was sealed, which was begun and largely redacted in the days of Rav Ashi and Ravina".[56]

The Wikkuah, a description of the 1240 Disputation of Paris, records that Yechiel of Paris claimed that "the Talmud is 1,500 years old", which would put it in the 3rd century BCE. Pietro Capelli suggests that it must have been traditional among medieval Ashkenazic Jews to date the Talmud from its beginning instead of its completion. Later manuscripts of the Wikkuah adopt the usual system of dating it to the time of Ravina II. Nicholas Donin, by contrast, claimed that the Talmud was only composed "400 years" before, i.e. around 840 CE.[55]

Modern estimates

[edit]A wide range of dates have been proposed for the Babylonian Talmud by historians.[57][58] The text was most likely completed, however, in the 6th century, or prior to the early Muslim conquests in the mid-7th century at the latest,[59] on the basis that the Talmud lacks loanwords or syntax deriving from Arabic. By comparison, Islamic-era rabbinic documents are heavily influenced by Arabic writing, convention, and loanwords, and rabbinic writings came to be exclusively written in Arabic by the 8th century.[60]

Recently, it has been extensively argued that Talmud is an expression and product of Sasanian culture,[61][62][63] as well as other Greek-Roman, Middle Persian, and Syriac sources up to the same period of time.[64] The contents of the text likely trace to this time regardless of the date of the final redaction/compilation.[65]

Additional external evidence for a latest possible date for the composition of the Babylonian Talmud are uses of it by external sources such as Letter of Baboi (c. 813)[66] and chronicles like the Seder Tannaim veAmoraim (9th century) and the Iggeret of Rabbi Sherira Gaon (987).[60] As for a lower boundary on the dating of the Babylonian Talmud, it must post-date the early 5th century given its reliance on the Jerusalem Talmud.[67]

In Jewish scholarship

[edit]From the time of its completion, the Talmud became integral to Jewish scholarship. A maxim in Pirkei Avot advocates its study from the age of 15.[68]

Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz writes that "If the Bible is the cornerstone of Judaism, then the Talmud is the central pillar ... No other work has had a comparable influence on the theory and practice of Jewish life, shaping influence on the theory and practice of Jewish life" and states:[69]

The Talmud is the repository of thousands of years of Jewish wisdom, and the oral law, which is as ancient and significant as the written law (the Torah) finds expression therein. It is a conglomerate of law, legend, and philosophy, a blend of unique logic and shrewd pragmatism, of history and science, anecdotes and humor... Although its main objective is to interpret and comment on a book of law, it is, simultaneously, a work of art that goes beyond legislation and its practical application. And although the Talmud is, to this day, the primary source of Jewish law, it cannot be cited as an authority for purposes of ruling...

Though based on the principles of tradition and the transmission of authority from generation to generation, it is unparalleled in its eagerness to question and reexamine convention and accepted views and to root out underlying causes. The talmudic method of discussion and demonstration tries to approximate mathematical precision, but without having recourse to mathematical or logical symbols.

...the Talmud is the embodiment of the great concept of mitzvat talmud Torah - the positive religious duty of studying Torah, of acquiring learning and wisdom, study which is its own end and reward.[69]

The following subsections outline some of the major areas of Talmudic study.

Legal interpretation

[edit]One area of Talmudic scholarship developed out of the need to ascertain the Halakha (Jewish rabbinical law). Early commentators such as Isaac Alfasi (North Africa, 1013–1103) attempted to extract and determine the binding legal opinions from the vast corpus of the Talmud. Alfasi's work was highly influential, attracted several commentaries in its own right and later served as a basis for the creation of halakhic codes. Another influential medieval Halakhic work following the order of the Babylonian Talmud, and to some extent modelled on Alfasi, was "the Mordechai", a compilation by Mordechai ben Hillel (c. 1250–1298). A third such work was that of Asher ben Yechiel (d. 1327). All these works and their commentaries are printed in the Vilna and many subsequent editions of the Talmud.

A 15th-century Spanish rabbi, Jacob ibn Habib (d. 1516), compiled the Ein Yaakov, which extracts nearly all the Aggadic material from the Talmud. It was intended to familiarize the public with the ethical parts of the Talmud and to dispute many of the accusations surrounding its contents.

Commentaries

[edit]Geonic-era (6th-11th centuries) commentaries have largely been lost, but are known to exist from partial quotations in later medieval and early modern texts. Because of this, it is known that now-lost commentaries on the Talmud were written by Paltoi Gaon, Sherira, Hai Gaon, and Saadya (though in this case, Saadiya is not likely to be the true author).[70] Of these, the commentary of Paltoi ben Abaye (c. 840) is the earliest. His son, Zemah ben Paltoi paraphrased and explained the passages which he quoted; and he composed, as an aid to the study of the Talmud, a lexicon which Abraham Zacuto consulted in the fifteenth century. Saadia Gaon is said to have composed commentaries on the Talmud, aside from his Arabic commentaries on the Mishnah.[71]

The first surviving commentary on the entire Talmud is that of Chananel ben Chushiel. Many medieval authors also composed commentaries focusing on the content of specific tractates, including Nissim ben Jacob and Gershom ben Judah.[72] The commentary of Rashi, covering most of the Talmud, has become a classic. Sections in the commentary covering a few tractates (Pes, BB and Mak) were completed by his students, especially Judah ben Nathan, and a sections dealing with specific tractates (Ned, Naz, Hor and MQ) of the commentary that appear in some print editions of Rashi's commentary today were not composed by him. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, a genre of rabbinic literature emerged surrounding Rashi's commentary, with the purpose of supplementing it and addressing internal contradictions via the technique of pilpul. This genre of commentary is known as the Tosafot and focuses on specific passages instead of a running continuous commentary across the entire Talmud.[73]

Many Talmudic passages are difficult to understand, sometimes owing to the use of Greek or Persian loanwords whose meaning had become obscure. A major area of Talmudic scholarship developed to explain these passages and words. Some early commentators such as Rabbenu Gershom of Mainz (10th century) and Rabbenu Ḥananel (early 11th century) produced running commentaries to various tractates. These commentaries could be read with the text of the Talmud and would help explain the meaning of the text. Another important work is the Sefer ha-Mafteaḥ (Book of the Key) by Nissim Gaon, which contains a preface explaining the different forms of Talmudic argumentation and then explains abbreviated passages in the Talmud by cross-referring to parallel passages where the same thought is expressed in full. Commentaries (ḥiddushim) by Joseph ibn Migash on two tractates, Bava Batra and Shevuot, based on Ḥananel and Alfasi, also survive, as does a compilation by Zechariah Aghmati called Sefer ha-Ner.[74]

The Tosafot are collected commentaries by various medieval Ashkenazic rabbis on the Talmud (known as Tosafists or Ba'alei Tosafot). One of the main goals of the Tosafot is to explain and interpret contradictory statements in the Talmud. Unlike Rashi, the Tosafot is not a running commentary, but rather comments on selected matters. Often the explanations of Tosafot differ from those of Rashi.[71] Among the founders of the Tosafist school were Rabbeinu Tam, who was a grandson of Rashi, and, Rabbenu Tam's nephew, Isaac ben Samuel. The Tosafot commentaries were collected in different editions in the various schools. The benchmark collection of Tosafot for Northern France was that of Eliezer of Touques. The standard collection for Spain was Rabbenu Asher's Tosefot haRosh. The Tosafot that are printed in the standard Vilna edition of the Talmud are an edited version compiled from the various medieval collections, predominantly that of Touques.[75]

Over time, the approach of the Tosafists spread to other Jewish communities, particularly those in Spain. This led to the composition of many other commentaries in similar styles. Among these are the commentaries of Nachmanides (Ramban), Solomon ben Adret (Rashba), Yom Tov of Seville (Ritva) and Nissim of Gerona (Ran); these are often titled “Chiddushei ...” (“Novellae of ...”). A comprehensive anthology consisting of extracts from all these is the Shitah Mekubezet of Bezalel Ashkenazi. Other commentaries produced in Spain and Provence were not influenced by the Tosafist style. Two of the most significant of these are the Yad Ramah by rabbi Meir Abulafia and Bet Habechirah by rabbi Menahem haMeiri, commonly referred to as "Meiri". While the Bet Habechirah is extant for all of Talmud, we only have the Yad Ramah for Tractates Sanhedrin, Baba Batra and Gittin. Like the commentaries of Ramban and the others, these are generally printed as independent works, though some Talmud editions include the Shitah Mekubezet in an abbreviated form.

In later centuries, focus partially shifted from direct Talmudic interpretation to the analysis of previously written Talmudic commentaries. Well known are "Maharshal" (Solomon Luria), "Maharam" (Meir Lublin) and "Maharsha" (Samuel Edels), which analyze Rashi and Tosafot together; other such commentaries include Ma'adanei Yom Tov by Yom-Tov Lipmann Heller, in turn a commentary on the Rosh (see below), and the glosses by Zvi Hirsch Chajes. These later commentaries are generally appended to the tractate.

Commentaries discussing the Halachik-legal content - outlined above - include "Rosh", "Rif" and "Mordechai"; these are now standard appendices to each volume. Rambam's Mishneh Torah is invariably studied alongside these three; although a code, and therefore not in the same order as the Talmud, the relevant location is identified via the "Ein Mishpat", following. (A recent project, Halacha Brura, founded by Abraham Isaac Kook, presents the Talmud and a summary of the halachic codes side by side, so as to enable the "collation" of Talmud with resultant Halacha.[76])

Found in almost all editions of the Talmud, is the "study-aid" consisting of the marginal notes Torah Or, Ein Mishpat Ner Mitzvah and Masoret ha-Shas by the Italian rabbi Joshua Boaz, which give references respectively: to the cited Biblical passages, to the relevant halachic codes (Mishneh Torah, Tur, Shulchan Aruch, and Se'mag) and to related Talmudic passages. Most editions of the Talmud include also the brief marginal notes by Akiva Eger under the name Gilyon ha-Shas, and textual notes by Joel Sirkes and the Vilna Gaon.

Pilpul

[edit]During the 15th and 16th centuries, a new intensive form of Talmud study arose. Complicated logical arguments were used to explain minor points of contradiction within the Talmud. The term pilpul was applied to this type of study. Usage of pilpul in this sense (that of "sharp analysis") harks back to the Talmudic era and refers to the intellectual sharpness this method demanded.

Pilpul practitioners posited that the Talmud could contain no redundancy or contradiction whatsoever. New categories and distinctions (hillukim) were therefore created, resolving seeming contradictions within the Talmud by novel logical means.

In the Ashkenazi world the founders of pilpul are generally considered to be Jacob Pollak (1460–1541) and Shalom Shachna. This kind of study reached its height in the 16th and 17th centuries when expertise in pilpulistic analysis was considered an art form and became a goal in and of itself within the yeshivot of Poland and Lithuania. But the popular new method of Talmud study was not without critics; already in the 15th century, the ethical tract Orhot Zaddikim ("Paths of the Righteous" in Hebrew) criticized pilpul for an overemphasis on intellectual acuity. Many 16th- and 17th-century rabbis were also critical of pilpul. Among them are Judah Loew ben Bezalel (the Maharal of Prague), Isaiah Horowitz, and Yair Bacharach.

By the 18th century, pilpul study waned. Other styles of learning such as that of the school of Elijah b. Solomon, the Vilna Gaon, became popular. The term "pilpul" was increasingly applied derogatorily to novellae deemed casuistic and hairsplitting. Authors referred to their own commentaries as "al derekh ha-peshat" (by the simple method)[77] to contrast them with pilpul.[78]

Sephardic approaches

[edit]Among Sephardi and Italian Jews from the 15th century on, some authorities sought to apply the methods of Aristotelian logic, as reformulated by Averroes.[79] This method was first recorded, though without explicit reference to Aristotle, by Isaac Campanton (d. Spain, 1463) in his Darkhei ha-Talmud ("The Ways of the Talmud"),[80] and is also found in the works of Moses Chaim Luzzatto.[81]

According to the present-day Sephardi scholar José Faur, traditional Sephardic Talmud study could take place on any of three levels.[82]

- The most basic level consists of literary analysis of the text without the help of commentaries, designed to bring out the tzurata di-shema'ta, i.e. the logical and narrative structure of the passage.[83]

- The intermediate level, iyyun (concentration), consists of study with the help of commentaries such as Rashi and the Tosafot, similar to that practiced among the Ashkenazim.[84] Historically Sephardim studied the Tosefot ha-Rosh and the commentaries of Nahmanides in preference to the printed Tosafot.[85] A method based on the study of Tosafot, and of Ashkenazi authorities such as Maharsha (Samuel Edels) and Maharshal (Solomon Luria), was introduced in late seventeenth century Tunisia by rabbis Abraham Hakohen (d. 1715) and Tsemaḥ Tsarfati (d. 1717) and perpetuated by rabbi Isaac Lumbroso[86] and is sometimes referred to as 'Iyyun Tunisa'i.[87]

- The highest level, halachah (Jewish law), consists of collating the opinions set out in the Talmud with those of the halachic codes such as the Mishneh Torah and the Shulchan Aruch, so as to study the Talmud as a source of law; the equivalent Ashkenazi approach is sometimes referred to as being "aliba dehilchasa".

Brisker method

[edit]In the late 19th century another trend in Talmud study arose. Hayyim Soloveitchik (1853–1918) of Brisk (Brest-Litovsk) developed and refined this style of study. Brisker method involves a reductionistic analysis of rabbinic arguments within the Talmud or among the Rishonim, explaining the differing opinions by placing them within a categorical structure. The Brisker method is highly analytical and is often criticized as being a modern-day version of pilpul. Nevertheless, the influence of the Brisker method is great. Most modern-day Yeshivot study the Talmud using the Brisker method in some form. One feature of this method is the use of Maimonides' Mishneh Torah as a guide to Talmudic interpretation, as distinct from its use as a source of practical halakha.

Rival methods were those of the Mir and Telz yeshivas.[88] See Chaim Rabinowitz § Telshe and Yeshiva Ohel Torah-Baranovich § Style of learning.

Textual criticism

[edit]Medieval era

[edit]The text of the Talmud has been subject to some level of critical scrutiny throughout its history. Rabbinic tradition holds that the people cited in both Talmuds did not have a hand in its writings; rather, their teachings were edited into a rough form around 450 CE (Talmud Yerushalmi) and 550 CE (Talmud Bavli.) The text of the Bavli especially was not firmly fixed at that time.

Gaonic responsa literature addresses this issue. Teshuvot Geonim Kadmonim, section 78, deals with mistaken biblical readings in the Talmud. This Gaonic responsum states:

... But you must examine carefully in every case when you feel uncertainty [as to the credibility of the text] – what is its source? Whether a scribal error? Or the superficiality of a second rate student who was not well versed?....after the manner of many mistakes found among those superficial second-rate students, and certainly among those rural memorizers who were not familiar with the biblical text. And since they erred in the first place... [they compounded the error.]

— Teshuvot Geonim Kadmonim, Ed. Cassel, Berlin 1858, Photographic reprint Tel Aviv 1964, 23b.

In the early medieval era, Rashi already concluded that some statements in the extant text of the Talmud were insertions from later editors. On Shevuot 3b Rashi writes "A mistaken student wrote this in the margin of the Talmud, and copyists [subsequently] put it into the Gemara."[b]

Early modern era

[edit]The emendations of Yoel Sirkis and the Vilna Gaon are included in all standard editions of the Talmud, in the form of marginal glosses entitled Hagahot ha-Bach and Hagahot ha-Gra respectively; further emendations by Solomon Luria are set out in commentary form at the back of each tractate. The Vilna Gaon's emendations were often based on his quest for internal consistency in the text rather than on manuscript evidence;[89] nevertheless many of the Gaon's emendations were later verified by textual critics, such as Solomon Schechter, who had Cairo Genizah texts with which to compare our standard editions.[90]

Contemporary scholarship

[edit]In the 19th century, Raphael Nathan Nota Rabinovicz published a multi-volume work entitled Dikdukei Soferim, showing textual variants from the Munich and other early manuscripts of the Talmud, and further variants are recorded in the Complete Israeli Talmud and Gemara Shelemah editions (see Critical editions, above).

Today many more manuscripts have become available, in particular from the Cairo Geniza. The Academy of the Hebrew Language has prepared a text on CD-ROM for lexicographical purposes, containing the text of each tractate according to the manuscript it considers most reliable,[91] and images of some of the older manuscripts may be found on the website of the National Library of Israel (formerly the Jewish National and University Library).[92] The NLI, the Lieberman Institute (associated with the Jewish Theological Seminary of America), the Institute for the Complete Israeli Talmud (part of Yad Harav Herzog) and the Friedberg Jewish Manuscript Society all maintain searchable websites on which the viewer can request variant manuscript readings of a given passage.[93]

Some trends within contemporary Talmud scholarship are listed below.

- Orthodox Judaism maintains that the oral Torah was revealed, in some form, together with the written Torah. As such, some adherents, most notably Samson Raphael Hirsch and his followers, resisted any effort to apply historical methods that imputed specific motives to the authors of the Talmud. Other major figures in Orthodoxy, however, took issue with Hirsch on this matter, most prominently David Tzvi Hoffmann[94] and Joseph Hirsch Dünner.

- Some scholars hold that there has been extensive editorial reshaping of the stories and statements within the Talmud. Lacking outside confirming texts, they hold that we cannot confirm the origin or date of most statements and laws, and that we can say little for certain about their authorship. In this view, the questions above are impossible to answer. See, for example, the works of Louis Jacobs and Shaye J.D. Cohen.

- Some scholars hold that the Talmud has been extensively shaped by later editorial redaction, but that it contains sources we can identify and describe with some level of reliability. In this view, sources can be identified by tracing the history and analyzing the geographical regions of origin. See, for example, the works of Lee I. Levine and David Kraemer.

- Some scholars hold that many or most of the statements and events described in the Talmud usually occurred more or less as described, and that they can be used as serious sources of historical study. In this view, historians do their best to tease out later editorial additions (itself a very difficult task) and skeptically view accounts of miracles, leaving behind a reliable historical text. See, for example, the works of Saul Lieberman, David Weiss Halivni, and Avraham Goldberg.

- Modern academic study attempts to separate the different "strata" within the text, to try to interpret each level on its own, and to identify the correlations between parallel versions of the same tradition. In recent years, the works of David Weiss Halivni and Shamma Friedman have suggested a paradigm shift in the understanding of the Talmud (Encyclopaedia Judaica 2nd ed. entry "Talmud, Babylonian"). The traditional understanding was to view the Talmud as a unified homogeneous work. While other scholars had also treated the Talmud as a multi-layered work, Halivni's innovation (primarily in the second volume of his Mekorot u-Mesorot) was to differentiate between the Amoraic statements, which are generally brief Halachic decisions or inquiries, and the writings of the later "Stammaitic" (or Saboraic) authors, which are characterised by a much longer analysis that often consists of lengthy dialectic discussion. The Jerusalem Talmud is very similar to the Babylonian Talmud minus Stammaitic activity (Encyclopaedia Judaica (2nd ed.), entry "Jerusalem Talmud"). Shamma Y. Friedman's Talmud Aruch on the sixth chapter of Bava Metzia (1996) is the first example of a complete analysis of a Talmudic text using this method. S. Wald has followed with works on Pesachim ch. 3 (2000) and Shabbat ch. 7 (2006). Further commentaries in this sense are being published by Friedman's "Society for the Interpretation of the Talmud".[95]

- Some scholars are indeed using outside sources to help give historical and contextual understanding of certain areas of the Babylonian Talmud. See for example the works of Yaakov Elman[96] and of his student Shai Secunda,[97] which seek to place the Talmud in its Iranian context, for example by comparing it with contemporary Zoroastrian texts.

Translations

[edit]| Part of a series of articles on |

| Editions of the Babylonian Talmud |

|---|

|

There are six contemporary translations of the Talmud into English:

Steinsaltz

[edit]- Adin Steinsaltz began his translation of the Babylonian Talmud into modern Hebrew (the original is mostly Aramaic with some Mishnaic Hebrew) in 1969 and completed it in 2010. (He also translated some tractates of the Jerusalem Talmud.) The Hebrew edition is printed in two formats: the original one in a new layout and the later one in the format of the traditional Vilna Talmud page; both are available in several sizes. The first attempt to translate the Steinsaltz edition into English was The Talmud: The Steinsaltz Edition (Random House), which contains the original Hebrew-Aramaic text with punctuation and an English translation based on Steinsaltz' complete Hebrew language translation of and commentary on the entire Talmud. This edition began to be released in 1989 but was never completed; only four tractates were printed in 21 volumes, with a matching Reference Guide translated from a separate work of Steinsaltz. Portions of the Steinsaltz Talmud have also been translated into French, Russian, and other languages.

- The Noé Edition of the Koren Talmud Bavli, published by Koren Publishers Jerusalem was launched in 2012. It has a new, modern English translation and the commentary of Adin Steinsaltz, and was praised for its "beautiful page" with "clean type".[98] From the right side cover (the front side of Hebrew and Aramaic books), the Steinsaltz Talmud edition has the traditional Vilna page with vowels and punctuation in the original Aramaic text. The Rashi commentary appears in Rashi script with vowels and punctuation. From the left side cover the edition features bilingual text with side-by-side English/Aramaic translation. The margins include color maps, illustrations and notes based on Adin Steinsaltz's Hebrew language translation and commentary of the Talmud. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb serves as the Editor-in-Chief. The entire set was completed in 42 volumes.

- In February 2017, the William Davidson Talmud was released to Sefaria.[99] This translation is a version of the Noé Steinsaltz edition above, which was released under Creative Commons license.[100]

Artscroll

[edit]

- The Schottenstein Edition of the Talmud (Artscroll/Mesorah Publications), is 73 volumes,[101] in an English translation edition[102] and a Hebrew translation edition.[103] In the translated editions, each English or Hebrew page faces the Aramaic/Hebrew page it translates. Each Aramaic/Hebrew page of Talmud typically requires three to six English or Hebrew pages of translation and notes. The Aramaic/Hebrew pages are printed in the traditional Vilna format, with a gray bar added that shows the section translated on the facing page. The facing pages provide an expanded paraphrase in English or Hebrew, with translation of the text shown in bold and explanations interspersed in normal type, along with extensive footnotes. Pages are numbered in the traditional way but with a superscript added, e.g. 12b4 is the fourth page translating the Vilna page 12b. Larger tractates require multiple volumes. The first volume was published in 1990, and the series was completed in 2004.

Soncino

[edit]- The Soncino Talmud (34 volumes, 1935–1948, with an additional index volume published in 1952 and a two-volume translation of the Minor Tractates later),[104][105] Isidore Epstein, Soncino Press. An 18 volume edition was published in 1961. Notes on each page provide additional background material. This translation: Soncino Babylonian Talmud is published both in English and in a parallel text edition, in which each English page faces the Aramaic/Hebrew page. It is also available on CD-ROM. Complete.

- In addition, a 7x5in travel or pocket edition[106] was published in 1959. This edition opens from the left for English and the notes, and from the right for the Aramaic, which, unlike the other editions, does not use standard Vilna Talmud page; instead, another older edition is used, in which each standard Talmud page is divided in two.[107]

Other English translations

[edit]- The Talmud of Babylonia. An American Translation, Jacob Neusner, Tzvee Zahavy, others. Atlanta: 1984–1995: Scholars Press for Brown Judaic Studies. Complete.

- Rodkinson: Portions[108] of the Babylonian Talmud were translated by Michael L. Rodkinson (1903). It has been linked to online, for copyright reasons (initially it was the only freely available translation on the web), but this has been wholly superseded by the Soncino translation. (see below, under Full text resources).

- The Babylonian Talmud: A Translation and Commentary, edited by Jacob Neusner[109] and translated by Jacob Neusner, Tzvee Zahavy, Alan Avery-Peck, B. Barry Levy, Martin S. Jaffe, and Peter Haas, Hendrickson Pub; 22-Volume Set Ed., 2011. It is a revision of "The Talmud of Babylonia: An Academic Commentary," published by the University of South Florida Academic Commentary Series (1994–1999). Neusner gives commentary on transition in use langes from Biblical Aramaic to Biblical Hebrew. Neusner also gives references to Mishnah, Torah, and other classical works in Orthodox Judaism.

Translations into other languages

[edit]- The Extractiones de Talmud, a Latin translation of some 1,922 passages from the Talmud, was made in Paris in 1244–1245. It survives in two recensions. There is a critical edition of the sequential recension:

- Cecini, Ulisse; Cruz Palma, Óscar Luis de la, eds. (2018). Extractiones de Talmud per ordinem sequentialem. Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Mediaevalis 291. Brepols.

- A circa 1000 CE translation of (some parts of)[110] the Talmud to Arabic is mentioned in Sefer ha-Qabbalah. This version was commissioned by the Fatimid Caliph Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah and was carried out by Joseph ibn Abitur.[111]

- The Talmud was translated by Shimon Moyal into Arabic in 1909.[112] There is one translation of the Talmud into Arabic, published in 2012 in Jordan by the Center for Middle Eastern Studies. The translation was carried out by a group of 90 Muslim and Christian scholars.[113] The introduction was characterized by Raquel Ukeles, Curator of the Israel National Library's Arabic collection, as "racist", but she considers the translation itself as "not bad".[114]

- In 2018 Muslim-majority Albania co-hosted an event at the United Nations with Catholic-majority Italy and Jewish-majority Israel celebrating the translation of the Talmud into Italian for the first time.[115] Albanian UN Ambassador Besiana Kadare opined: "Projects like the Babylonian Talmud Translation open a new lane in intercultural and interfaith dialogue, bringing hope and understanding among people, the right tools to counter prejudice, stereotypical thinking and discrimination. By doing so, we think that we strengthen our social traditions, peace, stability — and we also counter violent extremist tendencies."[116]

- In 2012, a first volume of the Talmud Bavli was published in Spanish by Tashema. It was translated in Jerusalem under the yeshiva directed by Rav Yaakov Benaim. It includes the translation and explanation of the Mishnah and Gemara, and the commentaries by Rashi and Tosafot. By 2023, 19 volumes have been published.[117][118]

Index

[edit]"A widely accepted and accessible index"[119] was the goal driving several such projects.:

- Mafteah haTalmud (1910-1930). Breslau: D. Rotenberg. The individual work of Michael Guttmann. Only four volumes were released before the remainder was lost in manuscript during The Holocaust.[120]

- Index Volume to the Soncino Talmud (1952). Soncino Press. 749 pages.[121][122]

- Thesaurus Talmudis (1954-2004). 45 volumes covering the Bavli and 10 covering the Yerushalmi. Prepared by Chaim Josua Kasowski and sons.

- Subject Concordance to the Babylonian Talmud (1959). Ejnar Munksgaard. By Lazarus Goldschmidt, revised by Rafael Edelmann.

- Otzar Imrei Avot (1959-1961), Ruben Mass. 5 volumes. Prepared by Zevi Larinman.

- Michlul haMa'amarim (1960). Mossad Harav Kook. A three-volume index of the Bavli and Yerushalmi, containing more than 100,000 entries.[123]

- Shevilei haTalmud (1996). Prepared by Uri Hain.

- HaMafteah (2011). Feldheim Publishers. Has over 30,000 entries.[119]

Editions

[edit]Bomberg Talmud 1523

[edit]The first complete edition of the Babylonian Talmud was printed in Venice by Daniel Bomberg 1520–23[124][125][126][127] with the support of Pope Leo X.[128][129][130][131] In addition to the Mishnah and Gemara, Bomberg's edition contained the commentaries of Rashi and Tosafot. Almost all printings since Bomberg have followed the same pagination. Bomberg's edition was considered relatively free of censorship.[132]

Froben Talmud 1578

[edit]Ambrosius Frobenius collaborated with the scholar Israel Ben Daniel Sifroni from Italy. His most extensive work was a Talmud edition published, with great difficulty, in 1578–81.[133]

Benveniste Talmud 1645

[edit]Following Ambrosius Frobenius's publication of most of the Talmud in installments in Basel, Immanuel Benveniste published the whole Talmud in installments in Amsterdam 1644–1648,[134] Although according to Raphael Rabbinovicz the Benveniste Talmud may have been based on the Lublin Talmud and included many of the censors' errors.[135] "It is noteworthy due to the inclusion of Avodah Zarah, omitted due to Church censorship from several previous editions, and when printed, often lacking a title page.[136]

Slavita Talmud 1795 and Vilna Talmud 1835

[edit]The edition of the Talmud published by the Szapira brothers in Slavita[137] was published in 1817,[138] and it is particularly prized by many rebbes of Hasidic Judaism. In 1835, after a religious community copyright[139][140] was nearly over,[141] and following an acrimonious dispute with the Szapira family, a new edition of the Talmud was printed by Menachem Romm of Vilna.

Known as the Vilna Edition Shas, this edition (and later ones printed by his widow and sons, the Romm publishing house) has been used in the production of more recent editions of Talmud Bavli.

A page number in the Vilna Talmud refers to a double-sided page, known as a daf, or folio in English; each daf has two amudim labeled א and ב, sides A and B (recto and verso). The convention of referencing by daf is relatively recent and dates from the early Talmud printings of the 17th century, though the actual pagination goes back to the Bomberg edition. Earlier rabbinic literature generally refers to the tractate or chapters within a tractate (e.g. Berachot Chapter 1, ברכות פרק א׳). It sometimes also refers to the specific Mishnah in that chapter, where "Mishnah" is replaced with "Halakha", here meaning route, to "direct" the reader to the entry in the Gemara corresponding to that Mishna (e.g. Berachot Chapter 1 Halakha 1, ברכות פרק א׳ הלכה א׳, would refer to the first Mishnah of the first chapter in Tractate Berachot, and its corresponding entry in the Gemara). However, this form is nowadays more commonly (though not exclusively) used when referring to the Jerusalem Talmud. Nowadays, reference is usually made in format [Tractate daf a/b] (e.g. Berachot 23b, ברכות כג ב׳). Increasingly, the symbols "." and ":" are used to indicate Recto and Verso, respectively (thus, e.g. Berachot 23:, :ברכות כג). These references always refer to the pagination of the Vilna Talmud.

Critical editions

[edit]The text of the Vilna editions is considered by scholars not to be uniformly reliable, and there have been a number of attempts to collate textual variants.

- In the late 19th century, Nathan Rabinowitz published a series of volumes called Dikduke Soferim showing textual variants from early manuscripts and printings.

- In 1960, work started on a new edition under the name of Gemara Shelemah (complete Gemara) under the editorship of Menachem Mendel Kasher: only the volume on the first part of tractate Pesachim appeared before the project was interrupted by his death. This edition contained a comprehensive set of textual variants and a few selected commentaries.

- Some thirteen volumes have been published by the Institute for the Complete Israeli Talmud (a division of Yad Harav Herzog), on lines similar to Rabinowitz, containing the text and a comprehensive set of textual variants (from manuscripts, early prints and citations in secondary literature) but no commentaries.[142]

There have been critical editions of particular tractates (e.g., Henry Malter's edition of Ta'anit), but there is no modern critical edition of the whole Talmud. Modern editions such as those of the Oz ve-Hadar Institute correct misprints and restore passages that in earlier editions were modified or excised by censorship but do not attempt a comprehensive account of textual variants. One edition, by Yosef Amar,[143] represents the Yemenite tradition, and takes the form of a photostatic reproduction of a Vilna-based print to which Yemenite vocalization and textual variants have been added by hand, together with printed introductory material. Collations of the Yemenite manuscripts of some tractates have been published by Columbia University.[144]

Editions for a wider audience

[edit]A number of editions have been aimed at bringing the Talmud to a wider audience. Aside from the Steinsaltz and Artscroll/Schottenstein sets there are:

- The Metivta edition, published by the Oz ve-Hadar Institute. This contains the full text in the same format as the Vilna-based editions,[145] with a full explanation in modern Hebrew on facing pages as well as an improved version of the traditional commentaries.[146]

- A previous project of the same kind, called Talmud El Am, "Talmud to the people", was published in Israel in the 1960s–80s. It contains Hebrew text, English translation and commentary by Arnost Zvi Ehrman, with short 'realia', marginal notes, often illustrated, written by experts in the field for the whole of Tractate Berakhot, 2 chapters of Bava Mezia and the halachic section of Qiddushin, chapter 1.

- Tuvia's Gemara Menukad:[145] includes vowels and punctuation (Nekudot), including for Rashi and Tosafot.[145] It also includes "all the abbreviations of that amud on the side of each page."[147]

Incomplete sets from prior centuries

[edit]- Amsterdam (1714, Proops Talmud and Marches/de Palasios Talmud): Two sets were begun in Amsterdam in 1714, a year in which "acrimonious disputes between publishers within and between cities" regarding reprint rights also began. The latter ran 1714–1717. Neither set was completed, although a third set was printed 1752–1765.[139]

Other notable editions

[edit]Lazarus Goldschmidt published an edition from the "uncensored text" of the Babylonian Talmud with a German translation in 9 volumes (commenced Leipzig, 1897–1909, edition completed, following emigration to England in 1933, by 1936).[148]

Twelve volumes of the Babylonian Talmud were published by Mir Yeshiva refugees during the years 1942 thru 1946 while they were in Shanghai.[149] The major tractates, one per volume, were: "Shabbat, Eruvin, Pesachim, Gittin, Kiddushin, Nazir, Sotah, Bava Kama, Sanhedrin, Makot, Shevuot, Avodah Zara"[150] (with some volumes having, in addition, "Minor Tractates").[151]

A Survivors' Talmud was published, encouraged by President Truman's "responsibility toward these victims of persecution" statement. The U.S. Army (despite "the acute shortage of paper in Germany") agreed to print "fifty copies of the Talmud, packaged into 16-volume sets" during 1947–1950.[152] The plan was extended: 3,000 copies, in 19-volume sets.

In visual arts

[edit]In Carl Schleicher's paintings

[edit]Rabbis and Talmudists studying and debating Talmud abound in the art of Austrian painter Carl Schleicher (1825–1903); active in Vienna, especially c. 1859–1871.

-

Jewish Scene I

-

Jewish Scene II

-

A Controversy Whatsoever on Talmud[153]

-

At the Rabbi's

Jewish art and photography

[edit]-

Jews studying Talmud, París, c. 1880–1905

-

Samuel Hirszenberg, Talmudic School, c. 1895–1908

-

Ephraim Moses Lilien, The Talmud Students, engraving, 1915

-

Maurycy Trębacz, The Dispute, c. 1920–1940

-

Solomon's Haggadoth, bronze relief from the Knesset Menorah, Jerusalem, by Benno Elkan, 1956

-

Hilel's Teachings, bronze relief from the Knesset Menorah

-

Jewish Mysticism: Jochanan ben Sakkai, bronze relief from the Knesset Menorah

-

Yemenite Jews studying Torah in Sana'a

Reception outside of Judaism

[edit]Christianity

[edit]The study of Talmud is not restricted to those of the Jewish religion and has attracted interest in other cultures. Christian scholars have long expressed an interest in the study of Talmud, which has helped illuminate their own scriptures. Talmud contains biblical exegesis and commentary on Tanakh that will often clarify elliptical and esoteric passages. The Talmud contains possible references to Jesus and his disciples, while the Christian canon makes mention of Talmudic figures and contains teachings that can be paralleled within the Talmud and Midrash. The Talmud provides cultural and historical context to the Gospel and the writings of the Apostles.[154]

South Korea

[edit]South Koreans reportedly hope to emulate Jews' high academic standards by studying Jewish literature. Almost every household has a translated copy of a book they call "Talmud", which parents read to their children, and the book is part of the primary-school curriculum.[155][156] The "Talmud" in this case is usually one of several possible volumes, the earliest translated into Korean from the Japanese. The original Japanese books were created through the collaboration of Japanese writer Hideaki Kase and Marvin Tokayer, an Orthodox American rabbi serving in Japan in the 1960s and 70s. The first collaborative book was 5,000 Years of Jewish Wisdom: Secrets of the Talmud Scriptures, created over a three-day period in 1968 and published in 1971. The book contains actual stories from the Talmud, proverbs, ethics, Jewish legal material, biographies of Talmudic rabbis, and personal stories about Tokayer and his family. Tokayer and Kase published a number of other books on Jewish themes together in Japanese.[157]

The first South Korean publication of 5,000 Years of Jewish Wisdom was in 1974, by Tae Zang publishing house. Many different editions followed in both Korea and China, often by black-market publishers. Between 2007 and 2009, Yong-soo Hyun of the Shema Yisrael Educational Institute published a 6-volume edition of the Korean Talmud, bringing together material from a variety of Tokayer's earlier books. He worked with Tokayer to correct errors and Tokayer is listed as the author. Tutoring centers based on this and other works called "Talmud" for both adults and children are popular in Korea and "Talmud" books (all based on Tokayer's works and not the original Talmud) are widely read and known.[157]

Iran

[edit]In 2012, then-Vice President of Iran, Mohammad Reza Rahimi, claimed that the Talmud was the cause of the spread of narcotics in the country.[158]

Criticism

[edit]| This article is of a series on |

| Criticism of religion |

|---|

Historian Michael Levi Rodkinson, in his book The History of the Talmud, wrote that detractors of the Talmud, both during and subsequent to its formation, "have varied in their character, objects and actions" and the book documents a number of critics and persecutors, including Nicholas Donin, Johannes Pfefferkorn, Johann Andreas Eisenmenger, the Frankists, and August Rohling.[159] Many of the attacks come from antisemitic sources such as in modern times Justinas Pranaitis, Elizabeth Dilling, and David Duke. Criticisms also arise from Christian, Muslim,[160][161][162] and Jewish sources,[163] as well as from atheists and skeptics.[164]

Accusations against the Talmud, particularly those from antisemitic sources, include alleged:[159][165][166][167][168]

- Anti-Christian or anti-gentile content[169][170][171][172]

- Absurd or sexually immoral content[173]

- Falsification of scripture[174][175][176]

Scholars point out that many of these criticisms are either outright falsehoods or based on quotations that are misrepresented or taken out of context, and that some critics misrepresent the meaning of the Talmud's text and its basic character as a detailed record of discussions that preserved statements by a variety of sages, from which statements and opinions that were rejected were never edited out.[177]

Middle Ages

[edit]At the very time that the Babylonian savoraim put the finishing touches to the redaction of the Talmud, the emperor Justinian issued his edict against deuterosis (doubling, repetition) of the Hebrew Bible.[178] It is disputed whether, in this context, deuterosis means "Mishnah" or "Targum": in patristic literature, the word is used in both senses.

Full-scale attacks on the Talmud took place in the 13th century in France, where Talmudic study was then flourishing. In the 1230s Nicholas Donin, a Jewish convert to Christianity, pressed 35 charges against the Talmud to Pope Gregory IX by translating a series of allegedly blasphemous passages about Jesus, Mary or Christianity. There is a quoted Talmudic passage, for example, where a person named Yeshu who some people have claimed is Jesus of Nazareth is sent to Gehenna to be boiled in excrement for eternity. Donin also selected an injunction of the Talmud that permits Jews to kill non-Jews. This led to the Disputation of Paris, which took place in 1240 at the court of Louis IX of France, where four rabbis, including Yechiel of Paris and Moses ben Jacob of Coucy, defended the Talmud against the accusations of Nicholas Donin. The translation of the Talmud from Aramaic to non-Jewish languages stripped Jewish discourse from its covering, something that was resented by Jews as a profound violation.[179] The Disputation of Paris led to the condemnation and the first burning of copies of the Talmud in Paris in 1242.[180][181][c] The burning of copies of the Talmud continued.[182]

The Talmud was likewise the subject of the Disputation of Barcelona in 1263 between Nahmanides and Pablo Christiani, a Jewish convert to Christianity, in which they argued whether Jesus was the messiah prophesized in Judaism. This same Pablo Christiani made an attack on the Talmud that resulted in a papal bull against the Talmud and in the first censorship, which was undertaken at Barcelona by a commission of Dominicans, who ordered the cancellation of passages deemed objectionable from a Christian perspective (1264).[183][184]

At the Disputation of Tortosa in 1413, Geronimo de Santa Fé brought forward a number of accusations, including the fateful assertion that the condemnations of "pagans", "heathens", and "apostates" found in the Talmud were, in reality, veiled references to Christians. These assertions were denied by the Jewish community and its scholars, who contended that Judaic thought made a sharp distinction between those classified as heathen or pagan, being polytheistic, and those who acknowledge one true God (such as the Christians) even while worshipping the true monotheistic God incorrectly. Thus, Jews viewed Christians as misguided and in error, but not among the "heathens" or "pagans" discussed in the Talmud.[184]

Both Pablo Christiani and Geronimo de Santa Fé, in addition to criticizing the Talmud, also regarded it as a source of authentic traditions, some of which could be used as arguments in favor of Christianity. Examples of such traditions were statements that the Messiah was born around the time of the destruction of the Temple and that the Messiah sat at the right hand of God.[185]

In 1415, Antipope Benedict XIII, who had convened the Tortosa disputation, issued a papal bull (which was destined, however, to remain inoperative) forbidding the Jews to read the Talmud, and ordering the destruction of all copies of it. Far more important were the charges made in the early part of the 16th century by the convert Johannes Pfefferkorn, the agent of the Dominicans. The result of these accusations was a struggle in which the emperor and the pope acted as judges, the advocate of the Jews being Johann Reuchlin, who was opposed by the obscurantists; and this controversy, which was carried on for the most part by means of pamphlets, became in the eyes of some a precursor of the Reformation.[184][186]

Renaissance

[edit]An unexpected result of this affair was the complete printed edition of the Babylonian Talmud issued in 1520 by Daniel Bomberg at Venice, under the protection of a papal privilege.[187] Three years later, in 1523, Bomberg published the first edition of the Jerusalem Talmud. In 1553, during the heightened tensions of the Counter-Reformation and following the Bragadin-Giustiniani dispute, new attacks were made again the Talmud and the Roman Inquisition advocated the burning of the Talmud.[188] The primary reason was not that the Talmud contained alleged blasphemies but that the Inquisition saw the Talmud as an obstacle in the conversion of Jews to Christianity.[189] Thus, on the New Year, Rosh Hashanah (September 9, 1553) the copies of the Talmud confiscated by a decree of the Inquisition and burned in Campo de' Fiori in Rome.[188] Other burnings took place in other Italian cities, such as the one instigated by Joshua dei Cantori at Cremona in 1559.

Censorship of the Talmud and other Hebrew works was introduced by a papal bull issued in 1554; five years later the Talmud was included in the first Index Expurgatorius. In 1564, Pope Pius IV abolished the prohibition against the Talmud, but decreed that it would need to be censored and could not have Talmud written on its title page.[189] The convention of referring to the work as "Shas" (shishah sidre Mishnah) instead of "Talmud" dates from this time.[190]

The first edition of the expurgated Talmud, on which most subsequent editions were based, appeared at Basel (1578–1581) with the omission of the entire treatise of 'Abodah Zarah and of passages considered inimical to Christianity, together with modifications of certain phrases. In 1581, however, Pope Gregory XIII ordered the confiscation of all Hebrew books including the Talmud and though his successor Sixtus V renounced this policy and preparations were made for a new edition of the Talmud, the successor of Sixtus V, Clement VIII Clement VIII renewed in his bull Cum hebraeorum malitia the 1557 ban on all Hebrew books except the Bible.[189] The increasing study of the Talmud in Poland led to the issue of a complete edition (Kraków, 1602–05), with a restoration of the original text; an edition containing, so far as known, only two treatises had previously been published at Lublin (1559–76). After an attack on the Talmud took place in Poland (in what is now Ukrainian territory) in 1757, when Bishop Dembowski, at the instigation of the Frankists, convened a public disputation at Kamieniec Podolski, and ordered all copies of the work found in his bishopric to be confiscated and burned.[191] A "1735 edition of Moed Katan, printed in Frankfurt am Oder" is among those that survived from that era.[149] "Situated on the Oder River, Three separate editions of the Talmud were printed there between 1697 and 1739."

The external history of the Talmud includes also the literary attacks made upon it by some Christian theologians after the Reformation since these onslaughts on Judaism were directed primarily against that work, the leading example being Eisenmenger's Entdecktes Judenthum (Judaism Unmasked) (1700).[192][193][194] In contrast, the Talmud was a subject of rather more sympathetic study by many Christian theologians, jurists and Orientalists from the Renaissance on, including Johann Reuchlin, John Selden, Petrus Cunaeus, John Lightfoot and Johannes Buxtorf father and son.[195] The Flemish scholar Andreas Masius considered that the attack on the Talmud and Hebrew literature would result in greatest damage to Christianity and that a certain knowledge of rabbinic literature was necessary for Christian studies.[189]

19th century and after

[edit]The Vilna edition of the Talmud was subject to Russian government censorship, or self-censorship to meet government expectations, though this was less severe than some previous attempts: the title "Talmud" was retained and the tractate Avodah Zarah was included. Most modern editions are either copies of or closely based on the Vilna edition, and therefore still omit most of the disputed passages. Although they were not available for many generations, the removed sections of the Talmud, Rashi, Tosafot and Maharsha were preserved through rare printings of lists of errata, known as Chesronos Hashas ("Omissions of the Talmud").[196] Many of these censored portions were recovered from uncensored manuscripts in the Vatican Library. Some modern editions of the Talmud contain some or all of this material, either at the back of the book, in the margin, or in its original location in the text.[197]

In 1830, during a debate in the French Chamber of Peers regarding state recognition of the Jewish faith, Admiral Verhuell declared himself unable to forgive the Jews whom he had met during his travels throughout the world either for their refusal to recognize Jesus as the Messiah or for their possession of the Talmud.[198] In the same year the Abbé Chiarini published a voluminous work entitled Théorie du Judaïsme, in which he announced a translation of the Talmud, advocating for the first time a version that would make the work generally accessible, and thus serve for attacks on Judaism: only two out of the projected six volumes of this translation appeared.[199] In a like spirit 19th-century antisemitic agitators often urged that a translation be made; and this demand was even brought before legislative bodies, as in Vienna. The Talmud and the "Talmud Jew" thus became objects of antisemitic attacks, for example in August Rohling's Der Talmudjude (1871), although, on the other hand, they were defended by many Christian students of the Talmud, notably Hermann Strack.[200]

Further attacks from antisemitic sources include Justinas Pranaitis' The Talmud Unmasked: The Secret Rabbinical Teachings Concerning Christians (1892)[201] and Elizabeth Dilling's The Plot Against Christianity (1964).[202] The criticisms of the Talmud in many modern pamphlets and websites are often recognizable as verbatim quotations from one or other of these.[203]

Historians Will and Ariel Durant noted a lack of consistency between the many authors of the Talmud, with some tractates in the wrong order, or subjects dropped and resumed without reason. According to the Durants, the Talmud "is not the product of deliberation, it is the deliberation itself."[204]

Contemporary accusations

[edit]The Internet is another source of criticism of the Talmud.[203] The Anti-Defamation League's report on this topic states that antisemitic critics of the Talmud frequently use erroneous translations or selective quotations in order to distort the meaning of the Talmud's text, and sometimes fabricate passages. In addition, the critics rarely provide the full context of the quotations and fail to provide contextual information about the culture that the Talmud was composed in, nearly 2,000 years ago.[205]

One such example concerns the line: "If a Jew be called upon to explain any part of the rabbinic books, he ought to give only a false explanation. One who transgresses this commandment will be put to death." This is alleged to be a quote from a book titled Libbre David (alternatively Livore David ). No such book exists in the Talmud or elsewhere.[206] The title is assumed to be a corruption of Dibre David, a work published in 1671.[207] Reference to the quote is found in an early Holocaust denial book, The Six Million Reconsidered by William Grimstad.[208]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The Mishnah is a written compendium of the Oral Torah. In this context, the terms 'Talmud' and 'Gemara' are essentially interchangeable.

- ^ As Yonah Fraenkel shows in his book Darko Shel Rashi be-Ferusho la-Talmud ha-Bavli, one of Rashi's major accomplishments was textual emendation. Rabbenu Tam, Rashi's grandson and one of the central figures in the Tosafist academies, polemicizes against textual emendation in his less studied work Sefer ha-Yashar. However, the Tosafists, too, emended the Talmudic text (see, e.g., Baba Kamma 83b s.v. af haka'ah ha'amurah or Gittin 32a s.v. mevutelet), as did many other medieval commentators (see, e.g., R. Shlomo ben Aderet, Hiddushei ha-Rashb"a al ha-Sha"s to Baba Kamma 83b, or Rabbenu Nissim's commentary to Alfasi on Gittin 32a).

- ^ For a Hebrew account of the Paris Disputation, see Jehiel of Paris, "The Disputation of Jehiel of Paris" (Hebrew), in Collected Polemics and Disputations, ed. J.D. Eisenstein, Hebrew Publishing Company, 1922; Translated and reprinted by Hyam Maccoby in Judaism on Trial: Jewish-Christian Disputations in the Middle Ages, 1982

Citations

[edit]- ^ "Catrina Langenegger on the Basel Talmud". 13 October 2022.

- ^ "BBC - Religions - Judaism: The Torah". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2025-10-01.

- ^ Youvan, Douglas C (August 2024). "Torah vs. Talmud: Divergent Paths in Jewish Thought and Practice Across Sects and Cultures". ResearchGate. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.17472.14082.

- ^ "Tanakh | Sefaria". www.sefaria.org. Retrieved 2025-10-01.

- ^ Fishman, Talya (2011). Becoming the People of the Talmud: Oral Torah as Written Tradition in Medieval Jewish Cultures. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-4313-0.

- ^ Neusner, Jacob (2003). The Formation of the Babylonian Talmud. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. ix. ISBN 9781592442195.

- ^ Steinsaltz, Adin (1976). The Essential Talmud. BasicBooks. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-465-02063-8.

- ^ Steinberg, Paul; Greenstein Potter, Janet (2007). Celebrating the Jewish Year: The Fall Holidays: Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur. The Jewish Publication Society. p. 42. ISBN 9780827608429.

- ^ Safrai, S. (1969). "The Era of the Mishnah and Talmud (70–640)". In Ben-Sasson, H.H. (ed.). A History of the Jewish People. Translated by Weidenfeld, George. Harvard University Press (published 1976). p. 379. ISBN 9780674397316.

The influence of the Babylonian geonim ... also weighted the scales in favour of the Talmud of their land, which they introduced and taught in all the Diaspora communities of the Middle Ages, as well as in the Land of Israel. Thus the Babylonian Talmud gained primary influence on Jewish history throughout the ages. It became the basic - and in many places almost the exclusive ~ asset of Jewish tradition, the foundation of all Jewish thought and aspirations and the guide for the daily life of the Jew. Other components of national culture were made known only in so far as they were embedded in the Talmud. In almost every period and community until the modern age, the Talmud was the main object of Jewish study and education; all the external conditions and events of life seemed to be but passing incidents, and the only true, permanent reality was that of the Talmud.

- ^ Brand, Ezra. "Beyond the Mystique: Correcting Common Misconceptions About the Talmud, and Pathways to Accessibility". www.ezrabrand.com. Retrieved 2025-05-18.

- ^ Safrai 1969, p. 305, 307.

- ^ Eisenberg, Ronald L. (2010). What the Rabbis Said: 250 Topics From the Talmud. Praeger. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-313-38450-9. OCLC 548555671.

- ^ Goldberg, Abraham (1987). "The Palestinian Talmud". In Safrai, Shmuel (ed.). The Literature of the Jewish People in the Period of the Second Temple and the Talmud, Volume 3 The Literature of the Sages. Brill. pp. 303–322. doi:10.1163/9789004275133_008. ISBN 9789004275133.

- ^ Jacob Neusner, The Talmud: What It Is and What It Says (2006). Rowman & Littlefield.

- ^ "HIS 155 1.7 the Talmud | Henry Abramson". 19 November 2013.

- ^ Hatch, Trevan G. (2019). A stranger in Jerusalem: seeing Jesus as a Jew. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-5326-4671-3.

- ^ Cohen, Barak S. (2017). For Out of Babylonia Shall Come Torah and the Word of the Lord from Nehar Peqod: The Quest for Babylonian Tannaitic Traditions. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-34702-1.

- ^ Cohen, Barak Shlomo (2009). "In Quest of Babylonian Tannaitic Traditions: The Case of Tanna D'Bei Shmuel". AJS Review. 33 (2): 271–303. doi:10.1017/S036400940999002X. ISSN 1475-4541.

- ^ Moscovitz, Leib (January 12, 2021). "Palestinian Talmud/Yerushalmi". Oxford Bibliographies Online. doi:10.1093/OBO/9780199840731-0151. ISBN 978-0-19-984073-1. Retrieved December 19, 2022.

- ^ Schiffman, Lawrence (1991). From Text to Tradition: A History of Second Temple and Rabbinic Judaism. Ktav Publishing House. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-88125-372-6.

- ^ "Palestinian Talmud". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2010. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- ^ Levine, Baruch A. (2005). "Scholarly Dictionaries of Two Dialects of Jewish Aramaic". AJS Review. 29 (1): 131–144. doi:10.1017/S0364009405000073. JSTOR 4131813. S2CID 163069011.

- ^ Reynold Nicholson (2011). A Literary History of the Arabs. Project Gutenberg, with Fritz Ohrenschall, Turgut Dincer, Sania Ali Mirza. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

- ^ Amsler, Monika (2023). The Babylonian Talmud and late antique book culture. Cambridge: Cambridge university press. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-009-29733-2.

- ^ Hezser, Catherine (2018). "The Creation of the Talmud Yerushalmi and Apophthegmata Patrum as Monuments to the Rabbinic and Monastic Movements in Early Byzantine Times". Jewish Studies Quarterly. 25 (4): 368–393. doi:10.1628/jsq-2018-0019. ISSN 0944-5706.

- ^ Mielziner, M. (Moses), Introduction to the Talmud (3rd edition), New York 1925, p. xx

- ^ "Talmud and Midrash (Judaism) / The making of the Talmuds: 3rd–6th century". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- ^ Moshe Gil (2004). Jews in Islamic Countries in the Middle Ages. BRILL. p. 507. ISBN 9789004138827.

- ^ a b Nosson Dovid Rabinowich (ed), The Iggeres of Rav Sherira Gaon, Jerusalem 1988, pp. 79, 116

- ^ Nosson Dovid Rabinowich (ed), The Iggeres of Rav Sherira Gaon, Jerusalem 1988, p. 116

- ^ Eisenberg, Ronald L. (2010). What the Rabbis Said: 250 Topics From the Talmud. Praeger. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-313-38450-9. OCLC 548555671.

- ^ AM Gray (2005). Talmud in Exile: The Influence of Yerushalmi Avodah Zarah. Brown Judaic Studies. ISBN 978-1-93067-523-0.

- ^ a b Pasachoff, Naomi E.; Littman, Robert J. (2005). A concise history of the Jewish people. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-7425-4366-9.

- ^ Encyclopaedia Judaica Bavli and Yerushalmi – Similarities and Differences, Gale

- ^ Ben-Menahem, Hanina; Edrei, Arye; Hecht, Neil S., eds. (2024). Windows onto Jewish Legal Culture: Fourteen Exploratory Essays. Routledge. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-415-50049-4.

- ^ "Judaism: The Oral Law -Talmud & Mishna", Jewish Virtual Library

- ^ Joseph Telushkin (26 April 1991), Literacy: The Most Important Things to Know About the Jewish Religion, Its People and Its History, HarperCollins, ISBN 0-68808-506-7

- ^ Steinsaltz, Adin (1976). The Essential Talmud. BasicBooks, A Division of HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-465-02063-8.[page needed]

- ^ Jacobs, Louis, Structure and form in the Babylonian Talmud, Cambridge University Press, 1991, p. 2

- ^ Cohen, Shaye J. D. (January 2006). From the Maccabees to the Mishnah (Second ed.). Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-664-22743-2. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Singer, Isidore; Adler, Cyrus (1916). The Jewish Encyclopedia: A Descriptive Record of the History, Religion, Literature, and Customs of the Jewish People from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. Funk and Wagnalls. pp. 527–528.

- ^ Strack, Hermann L.; Stemberger, Günter; Bockmuehl, Markus N. A.; Strack, Hermann L. (1996). Introduction to the Talmud and Midrash (2. Fortress Press ed., with amendations and updates ed.). Minneapolis, Minn: Fortress Press. ISBN 978-0-8006-2524-5.

- ^ e.g. Pirkei Avot 5.21: "five for the Torah, ten for Mishnah, thirteen for the commandments, fifteen for talmud".