Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

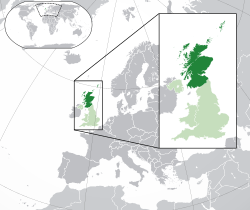

History of the Jews in Scotland

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 6,448 | — |

| 2011 | 5,887 | −8.7% |

| 2022 | 5,847 | −0.7% |

| Religious Affiliation was not recorded in the census prior to 2001. Source: National Records of Scotland | ||

| History of Scotland |

|---|

|

|

|

The history of the Jews in Scotland goes back to at least the 17th century. It is not known when Jews first arrived in Scotland, with the earliest concrete historical references to a Jewish presence in Scotland being from the late 17th century.[2] Most Scottish Jews today are of Ashkenazi background who mainly settled in Edinburgh, then in Glasgow in the mid-19th century. In 2013 the Edinburgh Jewish Studies Network curated an online exhibition based on archival holdings and maps in the National Library of Scotland exploring the influence of the community on the city.[3]

According to the 2011 census, 5,887 Jews lived in Scotland; a decline of 8.7% from the 2001 census.[4] The total population of Scotland at the time was 5,313,600, making Scottish Jews 0.1% of the population.

Middle Ages to union with England

[edit]There is only scant evidence of a Jewish presence in medieval Scotland. In 1180, the Bishop of Glasgow forbade churchmen to "ledge their benefices for money borrowed from Jews".[5] This was around the time of anti-Jewish riots in England and so it is possible that Jews may have arrived in Scotland as refugees, or it may refer to Jews domiciled in England from whom Scots were borrowing money.

In the Middle Ages, much of Scotland's trade was with Continental Europe, with wool of the Borders abbeys being the country's main export to Flanders and the Low Countries. Scottish merchants from Aberdeen and Dundee had close trading links to Baltic ports in Poland and Lithuania. It is possible, therefore, that Jews may have come to Scotland to do business with their Scottish counterparts, but no direct evidence of that exists.[6]

The late-18th-century author Henry Mackenzie speculated that the high incidence of biblical place names around the village of Morningside near Edinburgh might indicate that Jews had settled in the area during the Middle Ages. This belief has, however, been shown to be incorrect, with the names originating instead from the presence of a local farm named "Egypt" mentioned in historical documents from the 16th century and believed to indicate a Romani presence.[7]

17th–19th centuries

[edit]

The first recorded Jew in Edinburgh was one David Brown who made a successful application to reside and trade in the city in 1691.[8]

Most Jewish immigration appears to have occurred post-industrialisation, and post-1707, by which time Jews in Scotland were subject to various anti-Jewish laws that applied to Britain as a whole. Oliver Cromwell readmitted Jews to the Commonwealth of England in 1656, and would have had influence over whether they could reside north of the border. Scotland was under the jurisdiction of the Jewish Naturalisation Act, enacted in 1753, but repealed the next year. It has been theorised that some Jews who arrived in Scotland promptly assimilated, with some converting to Christianity.[9]

Unlike their English contemporaries, Scottish university students were not required to take a religious oath. Joseph Hart Myers, born in New York, was the first Jewish student to study medicine in Scotland; he graduated from the University of Edinburgh in 1779.[10] The first graduate from the University of Glasgow who was openly known to be Jewish was Levi Myers, in 1787. In 1795, Herman Lyon, a dentist and chiropodist, bought a burial plot in Edinburgh. Originally from Mogendorf, Germany he left there around 1764 and spent some time in Holland before arriving in London. He moved to Scotland in 1788. The presence of the plot on Calton Hill is no longer obvious today, but it is marked on the Ordnance Survey map of 1852 as "Jew's Burial vault".[8]

The first Jewish congregation in Edinburgh was founded in 1817, when the Edinburgh community consisted of 20 families.[8] The first congregation in Glasgow was founded in 1821.[11] Much of the first influx of Jews to Scotland were Dutch and German merchants attracted to the commercial economies of Scottish cities.[12]

Isaac Cohen, a hatter resident in Glasgow, was admitted a burgess of the city on 22 September 1812. The first interment in the Glasgow Necropolis was that of Joseph Levi, a quill merchant and cholera victim who was buried there on 12 September 1832. This occurred in the year before the formal opening of the burial ground, a part of it having been sold to the Jewish community beforehand for one hundred guineas.[13] Glasgow-born Asher Asher (1837–1889) was the first Scottish Jew to enter the medical profession. He was the author of The Jewish Rite of Circumcision (1873).

The story of his own family's experience was immortalised in Jack Ronder's book and TV series called The Lost Tribe, starring Miriam Margolyes and Bill Paterson.

In 1878, Jewish Hannah de Rothschild (1851–1890), the richest woman in Britain at the time, married Scottish aristocrat Archibald Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery, despite strong antisemitic sentiments in court and the aristocracy. They had four children. Their son, Harry, would become Secretary of State for Scotland in 1945 during Winston Churchill's post-war caretaker government.

To avoid persecution and pogroms in the Russian Empire in the 1880s, many Jews settled in the larger cities of Britain, including Scotland, most notably in Glasgow (especially the poorer part of the city, the Gorbals, alongside Irish and Italian immigrants).[14] Smaller numbers settled in Edinburgh and even smaller groups in Dundee (first synagogue founded in 1878[15] and cemetery acquired in 1888) and Aberdeen (synagogue founded 1893). Small communities also existed for a time in Ayr, Dunfermline, Falkirk, Greenock, and Inverness.[16] Russian Jews tended to come from the lands in the west of the empire known as the Pale of Settlement, in particular Lithuania and Poland, many using Scotland as a stopping post en route to North America. This explains why Glasgow was their favoured location. However, those who were not able to earn enough to afford the transatlantic voyage ended up settling in the city.[17] In 1897, after the influx, the Jewish population of Glasgow was 6,500.

This second influx of Jews was notably larger than the first, and came from Eastern Europe as opposed to Western European countries like Germany and the Netherlands. This led to the informal distinction between the Westjuden, who tended to be middle-class and assimilated into Scottish society, and the much bigger Ostjuden community, consisting of poor Yiddish-speakers who fled pogroms in Eastern Europe.[12] The Westjuden had settled in more affluent areas such as Garnethill in Glasgow where Garnethill Synagogue was built between 1879 and 1881 in Victorian Romanesque style. It remains the oldest active synagogue in Scotland and now houses the Scottish Jewish Archives Centre[18] and Scottish Jewish Heritage Centre.[19] The Ostjuden in contrast mostly settled in slums in the Gorbals. This led to the building in 1901 of the South Portland Street Synagogue, also known at various times as the South Side Synagogue, the Great Synagogue and the Great Central Synagogue,[20] regarded for many years as the religious centre of the Jewish community until its closure and demolition in 1974.

20th and 21st centuries

[edit]

Immigration continued into the 20th century, with over 9,000 Jews in 1901 and around 12,000 in 1911. Jewish life in the Gorbals in Glasgow initially mirrored that of traditional shtetl life; however, concerns around this being a contributing factor to a rise in anti-semitism led to the established Jewish community establishing various philanthropic and welfare organisations with the goals of offering assistance to the refugees, including support in assimilating into Scottish society.[21] Similarly the Edinburgh Jewish Literary Society was founded in 1888 for the purpose of teaching British culture to the Jewish immigrant population of Edinburgh[22] and is still active today, albeit with a different focus. The passing of the Aliens Act 1905 and the onset of World War I led to a substantial decrease in the number of Jewish refugees arriving in Scotland.[23]

In Edinburgh, the appointment of Rabbi Dr. Salis Daiches in 1918 was the catalyst for the unification of several disparate communities into a single Edinburgh Hebrew Congregation serving both the established anglicised Jews and the more recent Yiddish-speaking Eastern European immigrants.[24] Daiches also worked to foster good relations between the Jewish community and wider secular society,[25] and under his influence funds were raised for the building of the Edinburgh Synagogue, opened in 1932, the only purpose–built synagogue in the city.

Refugees from Nazi Germany and the Second World War further augmented the Scottish Jewish community, which has been estimated to have reached over 20,000 in the mid-20th century. By way of comparison, the Jewish population in the United Kingdom peaked at 500,000, but declined to just over half that number by 2008.[26]

Whittinghame Farm School operated from 1939 to 1941 as a shelter for 160 children who had arrived in Britain as part of the Kindertransport mission.[27] It was established in Whittinghame House in East Lothian, the family home of the Earl of Balfour and the birthplace of Arthur Balfour, author of the Balfour Declaration. The children were taught agricultural techniques in anticipation of settling in Palestine after the war.

The practising Jewish population continues to fall in Scotland, as many younger Jews either became secular, or intermarried with other faiths. Scottish Jews have also emigrated in large numbers to England, the United States, Israel, Canada, Australia and New Zealand for economic reasons, as other Scots have done. According to the 2001 census, 6,448 Jews lived in Scotland,[28] According to the 2011 census, 5,887 Jews lived in Scotland; a decline of 8.7% from 2001.[4][29] 41% (2,399) of Scottish Jews live in the local authority area of East Renfrewshire, Greater Glasgow, making up 2.65% of the population there. 25% of Scottish Jews live in the Greater Glasgow suburb of Newton Mearns alone. Many Jewish families slowly moved southwards to more prosperous suburban areas in Greater Glasgow, from more central areas of Glasgow over the generations.[14] Glasgow city itself has 897 Jews (15% of the Jewish population) living there, whilst Edinburgh has 855 (also 15%). The area with the least Jewish people was the Outer Hebrides, which reported just 3 Jews (0.05%) living there.

In March 2008, a Jewish tartan was designed by Brian Wilton[30] for Chabad rabbi Mendel Jacobs of Glasgow and certified by the Scottish Tartans Authority.[31] The tartan's colors are blue, white, silver, red and gold. According to Jacobs: "The blue and white represent the colours of the Scottish and Israeli flags, with the central gold line representing the gold from the Biblical Tabernacle, the Ark of the Covenant and the many ceremonial vessels ... the silver is from the decorations that adorn the Scroll of Law and the red represents the traditional red Kiddush wine."[32]

Jewish communities in Scotland are represented by the Scottish Council of Jewish Communities.

Historic antisemitism

[edit]In the Middle Ages, while Jews in England faced state persecution culminating in the Edict of Expulsion of 1290, there was never a corresponding expulsion from Scotland, suggesting either greater religious tolerance or the simple fact that there was no Jewish presence at that time. In his autobiographical work Two Worlds, the eminent Scottish-Jewish scholar David Daiches, son of Rabbi Salis Daiches, wrote that his father would often declare that Scotland is one of the few European countries with no history of state persecution of Jews.[33]

Modern antisemitism

[edit]Some elements of the British Union of Fascists formed in 1932 were anti-Jewish and Alexander Raven Thomson, one of its main ideologues, was a Scot. Blackshirt meetings were physically attacked in Edinburgh by communists and "Protestant Action", which believed the group to be an Italian (i.e. Roman Catholic) intrusion.[34] In fact, William Kenefick of Dundee University has claimed that bigotry was diverted away from Jews by anti-Catholicism, particularly in Glasgow where the main ethnic chauvinist agitation was against Irish Catholics.[35] Archibald Maule Ramsay, a Scottish Unionist MP claimed that World War II was a "Jewish war" and was the only MP in the UK interned under Defence Regulation 18B. In the Gorbals at least, neither Louise Sless nor Woolf Silver recall antisemitic sentiment.[36] (See also Jews escaping from Nazi Europe to Britain.) As a result of rising anti-semitism in the United Kingdom by the 1930s, Jewish leadership bodies including the Glasgow Jewish Representative Council adopted a position of trying to prevent drawing attention to the city's Jewish population, such as through the promotion of assimilation.[37] This was in line with the national leadership at the Board of Deputies of British Jews, although the Edinburgh Jewish Representative Council was notably more active and visible in its campaigning for support to be offered to German Jews.[38]

In 2012, the Scottish Jewish Student Chaplaincy and the Scottish Council of Jewish Communities reported a "toxic atmosphere" at the University of Edinburgh, in which Jewish students were forced to hide their identity.[39]

In September 2013, the Scottish Council of Jewish Communities published the "Being Jewish in Scotland" project, which researched the situation of Jewish people in Scotland through interviews and focus group attended by approximately 180 participants. The report included data from the Community Security Trust that, during 2011, there were 10 antisemitic incidents of abusive behaviour, 9 incidents of damage and desecration to Jewish property, and one assault. Some participants described experiences of antisemitism in their workplace, campus and at school.[40]

During the Operation Protective Edge, in August 2014, the Scottish Council of Jewish Communities reported a sharp increase in antisemitic incidents. During the first week of August, there were 12 antisemitic incidents – almost as many as in the whole of 2013.[41] A few months later, an irritating chemical was thrown on a member of staff selling Kedem (Israeli cosmetics) products in Glasgow's St Enoch Centre.[42] In 2015, the Scottish government published statistics on abusive behaviour in Religiously Aggravated Offending in Scotland in 2014–15, covering the Protective Edge period, which noted an increase in the number of charges filed for anti-Jewish acts from 9 in 2014 (2% of those charged with religious offences) to 25 in 2015 (4% of total). Most dealt with "threatening and abusive behavior" and "offensive communications". The penalty imposed on those convicted was typically a fine.[43]

Anti-semitism continues to be a topic of political debate in Scotland.[44][45][46] In 2017 the Scottish Government formally adopted the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s (IHRA) definition of anti-Semitism.[47]

Scots-Yiddish

[edit]Scots-Yiddish is the name given to a Jewish hybrid vernacular between Scots and Yiddish, which had a brief currency in the Lowlands in the first half of the 20th century. The Scottish literary historian David Daiches describes it in his autobiographical account of his Edinburgh Jewish childhood, Two Worlds.[48]

Daiches explores the social stratification of Edinburgh's Jewish society in the interwar period, noting what is effectively a class divide between two parts of the community, on the one hand a highly educated and well-integrated group who sought a synthesis of Orthodox Rabbinical and modern secular thinking, on the other a Yiddish-speaking group most comfortable maintaining the lifestyle of the Eastern European ghetto. The Yiddish-speaking population grew up in Scotland in the 19th century, but by the late 20th century had mostly switched to using English. The creolisation of Yiddish with Scots was therefore a phenomenon of the middle part of this period.[citation needed]

Daiches describes how this language was spoken by the band of itinerant salesmen known as "trebblers" who travelled by train to the coastal towns of Fife peddling their wares from battered suitcases. He notes that Scots preserves some Germanic words lost in standard English but preserved in Yiddish, for example "licht" for light or "lift" for air (German "Luft").[48][49]

The Glaswegian Jewish poet A C Jacobs also refers to his language as Scots-Yiddish.[50] The playwright and director Avrom Greenbaum also published a handful of Scots-Yiddish poems in the Glasgow Jewish Echo in the 1960s; these are now housed in the Scottish Jewish Archives Centre in Glasgow.[51] In 2020 the poet David Bleiman[52] won the first prize and Hugh MacDiarmaid Tassie in the Scots Language Association Sangschaw competition for his poem "The Trebbler's Tale" written in "macaronic" Scots-Yiddish.[53] Bleiman describes the poem as being 5% "found" Scots-Yiddish, the rest being reimagined and reconstituted from the component languages.[51]

Mythical history of the Jews in Scotland

[edit]List of Scottish Jews

[edit]

- Ronni Ancona, comedian[54]

- Jenni Calder, writer

- Hazel, Lady Cosgrove,[55] first female Court of Session judge

- Ivor Cutler, musician, teacher and comedian

- Noam Dar, professional wrestler

- Sir Monty Finniston, industrialist

- Hannah Frank, artist and sculptor

- Myer Lord Galpern, MP, Lord Provost of Glasgow

- Ralph Glasser, psychologist and economist (born in Leeds but grew up in Glasgow)

- Professor Sir Abraham Goldberg KB MD DSc FRCP FRSE, leading medical academic

- Muriel Gray, author and presenter of The Tube

- Jeremy Isaacs, broadcaster, born in Glasgow from what were described as "Scottish Jewish roots".[56]

- A C Jacobs, poet

- Mark Knopfler, Dire Straits co-founder, lead vocalist and lead guitarist

- Kevin Macdonald, director, known for Touching the Void

- Isi Metzstein, architect

- Saul Metzstein, filmmaker

- Neil Primrose, MP and soldier, younger son of Hannah de Rothschild

- Malcolm Rifkind, politician

- Hugo Rifkind, broadcaster

- Harry Primrose, 6th Earl of Rosebery, Secretary of State for Scotland, elder son of Hannah de Rothschild

- Jerry Sadowitz, controversial comedian and conjurer

- Benno Schotz, sculptor

- Sara Sheridan, writer

- Manny Shinwell, politician

- J. David Simons, novelist

- Dame Muriel Spark, novelist[57]

- Harry, Lord Woolf, judge, brought up and educated in Scotland

- Scottie Wilson, artist

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]- ^ "Scotland's Census 2022 – Ethnic group, national identity, language and religion – Chart data". Scotland's Census. National Records of Scotland. 21 May 2024. Retrieved 21 May 2024. Alternative URL 'Search data by location' > 'All of Scotland' > 'Ethnic group, national identity, language and religion' > 'Religion'

- ^ Daiches, Salis (1929). The Jew in Scotland. Scottish Church History Society. pp. 196–209. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ^ "Exhibition: Edinburgh Jews". Edinburgh Jewish Studies Network. 20 May 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Scotland's Census 2011 – Table KS209SCb" (PDF). scotlandscensus.gov.uk. Retrieved 26 September 2013.,

- ^ "Scotland Virtual Jewish History Tour". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ "Edinburgh Jewish Community". Electric Scotland. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ C J Smith, Historic South Edinburgh, Edinburgh & London 1978, p. 205: "At the distance of less than a mile from Edinburgh there are places with Jewish names—Canaan, the river or brook called Jordan, Egypt—a place called Transylvania, a little to the east of Egypt. There are two traditions of the way in which they got their names: one, that there was a considerable eruption of gypsies into the county of Edinburgh who got a grant of these lands, then chiefly a moor; the other, which I have heard from rather better authority, that some rich Jews happened to migrate into Scotland and got from one of the Kings (James I, I think it was said) a grant of these lands in consideration of a sum of money which they advanced him."

- ^ a b c "Edinburgh Jewish History". Edinburgh Jewish Community. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ Collins, Kenneth E. (1987). Aspects of Scottish Jewry. Glasgow: Glasgow Jewish Representative Council. p. 4.

- ^ "Joseph Hart Myers | RCP Museum". history.rcplondon.ac.uk. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ "Glasgow – SJAC". Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- ^ a b Alderman, Geoffrey (1992). Modern British Jewry. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 25–26.

- ^ D Daiches, Glasgow, Andre Deutsch, 1977, pp. 139–140

- ^ a b Pupils at Queen's Park Secondary 1936 (Scottish Jewish Archives Centre), The Glasgow Story

- ^ Abrams, Nathan (2009). Caledonian Jews: a study of seven small communities in Scotland. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-5432-7. OCLC 646854050.

- ^ "JCR-UK: Scotland Jewish Community and Congregations (Synagogues)". www.jewishgen.org. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ^ R Glasser, Growing Up in the Gorbals, Chatto & Windus, 1986

- ^ "SJAC – The Scottish Jewish Archives Centre". Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ^ "Home". Scottish Jewish Heritage Centre. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ^ "JCR-UK: Great Central Synagogue (formerly known as Great Synagogue) Glasgow, Scotland". www.jewishgen.org. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ^ Adler, Cyrus (1920). American Jewish Yearbook. New York City: American Jewish Yearbook. p. 183.

- ^ "About". Edinburgh Jewish Literary Society. 5 June 2011. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ^ Bermant, Chaim (1970). Troubled Eden: An Anatomy of British Jewry. New York City: Basic Books. p. 74.

- ^ Holtschneider, K. Hannah (2019). Jewish Orthodoxy in Scotland: Rabbi Dr Salis Daiches and religious leadership. Edinburgh. ISBN 978-1-4744-5261-8. OCLC 1128271833.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Gilfillan, M.D. (2019). Jewish Edinburgh: a history, 1880–1950. Jefferson, NC. ISBN 978-1-4766-3565-1. OCLC 1086210748.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Pigott, Robert (21 May 2008). "Jewish population on the increase". BBC News.

- ^ "Home Front – Whittingehame Farm School". www.eastlothianatwar.co.uk. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ Scottish Government (28 February 2005). "Analysis of Religion in the 2001 Census". scotland.gov.uk.

- ^ "Census 2011".

- ^ "Jewish Tartan". Scottish Tartans Authority. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ Schwartzapfel, Beth (17 July 2008). "Sound the Bagpipes: Scots Design Jewish Tartan". Forward. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ Hamilton, Tom (16 May 2008). "Rabbi creates first official Jewish tartan". Daily Record. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ David Daiches, Two Worlds, 1956, Cannnongate edition 1987, ISBN 0-86241-148-3, p. 93.

- ^ Cullen, Stephen (26 December 2008), "Nationalism and sectarianism 'stopped rise of Scots fascists'", Herald

- ^ Boztas, Senay (17 October 2004), "Why Scotland has never hated Jews ... it was too busy hating Catholics", Sunday Herald, archived from the original on 31 January 2006, retrieved 1 May 2010

- ^ Fleischmann, Kurt. "The Gorbals and the Jews of Glasgow". European Sephardic Institute.

- ^ Braber, Ben (2007). Jews in Glasgow 1879–1939: Immigration and Integration. London: Vallentine Mitchell. p. 38.

- ^ Gilfillan, Mark (2015). "Jewish responses to fascism and antisemitism in Edinburgh, 1933–1945". Journal of Scottish Historical Studies. 35 (2): 211–239. doi:10.3366/jshs.2015.0155.

- ^ "Jewish students warn of 'toxic' atmosphere at uni". The Scotsman. 15 December 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ^ Granat, Leah; Borowski, Ephraim; Frank, Fiona. "Being Jewish in Scotland" (PDF). The Scottish Council of Jewish Communities (scojec). Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ^ "Large Spike in Antisemitic Incidents in Scotland". The Scottish Council of Jewish Communities. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ^ "Kedem staff member doused in 'burning' chemical in hate attack". Jewish Chronicle. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- ^ Davidson, Neil. "Religiously Aggravated Offending in Scotland in 2014–15" (PDF). Justice Analytical Services – The Scottish Government. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ "Labour MSP 'ashamed of party' over anti-Semitism". BBC News. 28 November 2020. Retrieved 14 November 2021.

- ^ "Tories call for Greens to be removed from government after concerns by Jewish community". www.scotsman.com. Retrieved 14 November 2021.

- ^ "Jackson Carlaw: Scotland's Jews are entitled to feel safe and valued". HeraldScotland. 6 January 2019. Retrieved 14 November 2021.

- ^ "Scottish Government adoption of full IHRA definition of anti-Semitism: FOI release". www.gov.scot. Retrieved 14 November 2021.

- ^ a b Daiches, David (1987). Two worlds : an Edinburgh Jewish childhood. Edinburgh: Canongate. pp. 117–129. ISBN 0-86241-148-3. OCLC 16758930.

- ^ "The Secret Yiddish History of Scotland". The Forward. 16 September 2014. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ Relich, Mario. "The Strange Case of A. C. Jacobs" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2006.

- ^ a b "Scotslanguage.com – Scots-Yiddish: A Dialect Re-imagined". www.scotslanguage.com. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ "David Bleiman – Poet". Scottish Poetry Library. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ "SCoJeC's Macaronic World Premiere". www.scojec.org. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ Diary p. 66, "Could there be a hint of racial stereotyping in the Almeida's decision to cast two Jewish actors – Ronni Ancona and Henry Goodman – in its upcoming production of The Hypochondriac?", Jewish Chronicle, 28 September 2005,

- ^ "Feature article". Culham College Institute. Archived from the original on 20 October 2007.

- ^ Attias, Elaine. "Britain's exciting Channel 4 breaking all the TV rules", Toronto Star, 1 November 1986. Accessed 31 August 2011. "In his early 50s, he is a personal and passionate man who went from Scottish Jewish roots to a philosophy degree at Oxford, presidency of the Oxford Union and on to top programming positions at Thames and Granada television, Britain's powerful commercial independents."

- ^ Jewish father; mother Anglican but Muriel Spark's son says that she had Jewish parents; converted to Catholicism later in life

Further reading

[edit]- Collins Dr. KE, Borowski E, and Granat L – Scotland's Jews – A Guide to the History and Community of the Jews in Scotland (2008)

- Daiches, David – Two Worlds, Canongate Classics (1987)

- Levy, A – The Origins of Scottish Jewry

- Phillips, Abel – A History of the Origins of the First Jewish Community in Scotland: Edinburgh, 1816 (1979)

- Glasser, R – Growing Up in the Gorbals, Chatto & Windus (1986)

- Shinwell, Manny – Conflict Without Malice (1955) – autobiography

- Conn, A (editor) – Serving Their Country- Wartime Memories of Scottish Jews (2002)

- Kaplan, H L – Jewish Cemeteries in Scotland in Avotaynu, Vol. VII, No. 4, Winter 1991

- Ronder, Jack – The Lost Tribe, W.H. Allen (1978)

External links

[edit]- Jewish Year Book (JYB)

- Jewish Community of Edinburgh – Chabad on Campus

- Scottish Council of Jewish Communities

- Jewish Encyclopedia on Scotland

- Scottish Jewish Archives Centre

- Scottish Jewish Archives Centre Digital Collection

- Edinburgh Burgh Records, 1691

- The Virtual Jewish History Tour – Scotland

- Curious Edinburgh Jewish History walking tour

- Jewish burial ground in the Glasgow Necropolis

- Edinburgh Hebrew Congregation

- Aberdeen Hebrew Congregation

- Sukkat Shalom Edinburgh – the Edinburgh Liberal Jewish Community

- The Secret Yiddish History of Scotland

History of the Jews in Scotland

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Early Presence

Legendary and Mythical Accounts

Various speculative theories propose an early Jewish presence in Scotland predating documented history, though these lack empirical support and are classified as mythical by scholars. One prominent modern narrative, detailed in Elizabeth Caldwell Hirschman and Donald N. Yates's When Scotland Was Jewish (2007), claims Sephardic Jews from France, Spain, and Portugal migrated to Scotland in waves between the 11th and 17th centuries, intermarrying with clans such as the Bruces, Campbells, Douglases, Gordons, and Stewarts. The authors interpret DNA haplogroups (e.g., Mediterranean and Cohen modal haplotypes), surname etymologies, heraldic symbols like the Lion of Judah, and architectural motifs as evidence of crypto-Jewish practices among Scottish nobility, linking Presbyterianism to hidden Judaic traditions and suggesting figures like John Knox had Marrano ancestry.[9][10] These assertions rely on selective reinterpretations of genealogical records and genetic data, but mainstream historians dismiss them as pseudohistorical, citing the absence of archaeological sites, medieval charters, synagogues, or tax rolls indicating Jewish communities—contrasting sharply with England's documented 11th–13th-century settlements expelled in 1290. No contemporary Scottish chronicles or ecclesiastical records reference Jews before the 17th century, when the first verified resident, David Brown, arrived in 1691.[6][11] Folklore in Celtic regions, including Scotland, occasionally romanticizes interfaith harmony, with a persistent myth portraying non-Jewish Scots as uniquely hospitable to Jews due to shared "Old Testament" values in Presbyterianism. This notion, echoed in 19th–20th-century community histories, overlooks documented anti-alien rhetoric in World War I-era newspapers and earlier exclusionary policies. Such accounts serve more as cultural idealization than verifiable legend, underscoring Scotland's historical insularity rather than substantive early contact.[12]Medieval to Pre-Union Period (Up to 1707)

In the medieval period, there is no evidence of a settled Jewish population in Scotland, unlike in neighboring England where Jews resided from the 11th century until their expulsion in 1290.[6] The earliest documented reference to Jews appears in 1180, when the Bishop of Glasgow issued a regulation prohibiting churchmen from pledging their benefices as collateral for loans from Jews, suggesting that Jewish moneylenders operated transiently or held financial interests in the region without establishing residence.[6] [13] This indicates occasional commercial interactions, likely by merchants from England or continental Europe, but no permanent communities formed, possibly due to Scotland's peripheral economic position and lack of royal invitations to Jewish financiers as occurred elsewhere in medieval Europe.[14] By the 17th century, records of individual Jews emerge, marking the onset of sporadic settlement. The first professing Jew recorded in Scotland was David Brown, a merchant who in 1691 successfully petitioned the Edinburgh Town Council for permission to reside and trade in the city.[15] [3] Earlier, Jews occasionally attended Edinburgh University; for instance, a Jewish individual is noted in connection with the institution by 1641, though details of settlement remain unclear.[16] Other early arrivals included merchants and traders from England, Holland, and Germany, drawn to burgeoning markets in Edinburgh and Glasgow, as well as figures like Julius Conradus Otto, a convert to Christianity who later reverted to Judaism.[3] [14] These individuals operated primarily as traders or professionals, with no formal synagogue or communal institutions established before the 18th century.[17] The Jewish presence remained negligible, numbering likely fewer than a dozen by 1707, reflecting Scotland's relative religious and economic insularity compared to England, where readmission occurred in 1656 under Cromwell.[13] No anti-Jewish legislation akin to expulsions or blood libels is recorded in Scotland during this era, allowing quiet integration for the few present, though systemic exclusion from guilds and land ownership persisted.[2] This pre-Union phase laid minimal groundwork for later growth, with Jews viewed pragmatically as economic actors rather than a distinct minority warranting targeted policy.[6]Immigration and Community Formation (18th–19th Centuries)

Initial Settlements and Legal Integration

The earliest organized Jewish community in Scotland formed in Edinburgh during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, with the first synagogue established in 1816 by approximately 20 families in a rented room off Nicholson Street.[18] These initial settlers were primarily merchants and peddlers originating from England, the Netherlands, and Germany, drawn by opportunities in trade amid Scotland's growing economy.[1] By 1817, the congregation had secured space at 22 North Richmond Street, accommodating up to 67 worshippers, marking Scotland's inaugural purpose for Jewish religious practice.[19] In Glasgow, Jewish presence emerged slightly later, with the first documented settler recorded in 1812, followed by the formal community foundation in 1823.[6] Early arrivals numbered in the dozens, focusing on commerce in tobacco, textiles, and hawking goods, which facilitated gradual community building without large-scale influxes until later decades.[20] A small burial ground was acquired in Edinburgh around 1820, underscoring the community's intent for permanence despite modest size.[21] Legally, Jews in Scotland encountered fewer barriers than in England, as the nation lacked a history of medieval expulsion or codified anti-Jewish statutes post-Union in 1707.[22] Scotland's independent legal system and Presbyterian establishment avoided Anglican sacramental tests, permitting Jews to reside, trade, and own property as resident aliens or through naturalization under British acts.[13] Individuals registered as aliens from the 1790s, but no specific disabilities prevented synagogue formation or burial rights, reflecting relative tolerance rooted in the absence of entrenched religious hierarchies imposing oaths on non-Christians.[23] Full civic equality aligned with broader UK emancipation efforts, culminating in 1858 when parliamentary oaths were reformed to allow Jewish members without Christian affirmations, though Scottish Jews had earlier accessed municipal offices and universities due to localized practices.[24] This framework enabled initial integration, with early community leaders petitioning for and obtaining legal recognition for religious institutions, fostering stability amid economic adaptation.[14]Economic Contributions and Social Adaptation

The earliest Jewish settlers in Scotland during the early 19th century, primarily merchants from Germany and the Netherlands, contributed to the commercial economies of Glasgow and Edinburgh by engaging in import-export trades such as furs, jewelry, and haberdashery.[25] Isaac Cohen, admitted as a Freeman of Glasgow in 1812, operated as a hatter and tobacconist, exemplifying early involvement in retail and tobacco-related commerce, a sector tied to Scotland's transatlantic trade networks.[26] Other pioneers included P. Levy, who established a fur manufacturing business in 1817, and merchants like M. H. Schwabe in 1819, who dealt in general goods, helping to stimulate urban markets amid Scotland's industrial expansion.[26] Peddling emerged as a key entry point for many Jewish immigrants, allowing them to distribute textiles, small wares, and household items to rural and mining communities accessible from Glasgow and Edinburgh, with significant numbers active before World War I.[27] By the mid-19th century, Jewish occupational patterns diversified into stationers, quill merchants, and fancy goods dealers, as seen with Philip Asher in 1838 and G. T. Ascher, fostering retail innovation in city centers.[26] These activities supported economic mobility, with the Jewish population growing from 323 in 1841 to approximately 9,000 by 1901, though high transiency rates reflected ongoing migration patterns.[25] Socially, Jews adapted by leveraging post-Union legal frameworks that permitted settlement without medieval-era expulsions, establishing the first formal community in Edinburgh in 1816 and a synagogue in Glasgow's High Street in 1823.[27] Integration advanced through civic participation, such as Michael Simons becoming a Bailie in Glasgow during the 1880s, signaling acceptance among local elites, and the formation of welfare organizations like the Glasgow Hebrew Philanthropic Society in 1858 to aid newcomers.[27] Synagogues like Garnethill in Glasgow, opened in 1879 with 445 seats, served as hubs for religious and social cohesion, enabling Jews to balance commercial pursuits with communal life amid urban dispersal.[26] This adaptation contrasted with more restrictive environments elsewhere, as Scottish authorities granted freeman status and business licenses relatively readily, facilitating economic embedding without widespread formal naturalization barriers until later waves.[26]20th Century Expansion and Challenges

Eastern European Influx and Peak Growth

The influx of Jews from Eastern Europe to Scotland accelerated in the 1880s, primarily fleeing pogroms and economic restrictions in the Russian Empire following the assassination of Tsar Alexander II on March 13, 1881, which triggered widespread anti-Jewish riots across Ukraine, Poland, and other regions.[28] These pogroms, involving mob violence, property destruction, and murders, displaced hundreds of thousands, with many seeking refuge in Britain due to its relative religious tolerance and industrial opportunities.[29] Scotland, though receiving fewer immigrants than London or Leeds—estimated at under 10% of total UK Jewish arrivals—saw its Jewish population rise from approximately 1,600 in the 1881 census to around 6,000 by the early 1900s, concentrated in Glasgow's Gorbals and Cowcaddens districts.[30][20] Glasgow emerged as the primary destination due to its textile and manufacturing industries, where newcomers initially worked as peddlers, tailors, and cigarette makers before establishing small workshops.[3] By 1897, the city's Jewish population reached 4,000, surging to 6,500 by 1902 amid continued arrivals from Lithuania, Poland, and Russia, often via Hamburg or direct ports like Leith.[20] The Aliens Act of 1905 curtailed unrestricted entry but did not halt the flow entirely until World War I restrictions in 1914, by which time Scotland's Jewish community had grown to over 7,000 in Glasgow alone, with smaller numbers in Edinburgh (around 1,000) and Dundee.[31] This period marked peak growth, with the total Scottish Jewish population exceeding 13,000 between the world wars, reflecting family reunifications and natural increase alongside initial migration waves.[30] Community institutions expanded to accommodate the influx, including the Garnethill Synagogue's consolidation as Glasgow's central Orthodox house of worship and the founding of Hebrew schools and mutual aid societies to support Yiddish-speaking immigrants transitioning to urban Scottish life.[20] Economic adaptation was rapid, with Jews contributing to sectors like confectionery and retail, though initial overcrowding in tenements fueled localized tensions; however, systemic antisemitism remained limited compared to Eastern Europe, enabling upward mobility for subsequent generations.[31] By the 1920s, interwar policies and economic pressures slowed further immigration, solidifying the demographic peak achieved through this Eastern European migration.[32]Impacts of World Wars and Holocaust Refugees

During World War I, Scotland's Jewish population of approximately 12,000—predominantly recent immigrants from the Russian Empire—encountered heightened scrutiny and anti-alienist sentiments, as local press portrayed them as potential security risks amid wartime paranoia.[33] [34] Nevertheless, around 1,500 Scottish Jews enlisted in the British armed forces, demonstrating loyalty through service; over 100 lost their lives in combat.[35] [36] In Edinburgh alone, 153 Jewish men served, with 20 fatalities, honored by a memorial unveiled in Piershill Cemetery on November 11, 1921.[37] Postwar commemorations and public affirmations of patriotism largely overshadowed pre-armistice suspicions, reinforcing community integration.[33] The Aliens Act of 1905, compounded by wartime restrictions, curtailed further Eastern European immigration, stabilizing but not expanding the population.[34] World War II brought renewed military contributions from Scottish Jews, alongside refuge for those fleeing Nazi persecution; Scotland hosted around 1,000 Jewish soldiers among 30,000 Polish servicemen stationed there, fostering alliances amid the Holocaust's devastation in Poland.[38] From 1938 to 1939, approximately 700 unaccompanied Jewish children arrived via the Kindertransport, primarily from Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia, placed with host families or institutions in Glasgow and Edinburgh through efforts by synagogues and aid groups like the Glasgow Jewish Representative Council.[39] [14] Adult refugees also settled, often in urban centers, supported by communal networks that provided housing, kosher provisions, and employment assistance despite wartime rationing.[40] These arrivals, part of a broader 1930s influx escaping pogroms and Kristallnacht, bolstered the community to a postwar peak of about 18,000 by the 1950s, though many Kindertransportees faced trauma from family losses in concentration camps like Auschwitz.[41] [42] Integration varied: some anglicized names and assimilated, while others preserved traditions, contributing economically—e.g., in catering and nursing—and culturally, with survivors like Henry Wuga founding businesses in Glasgow.[42] The refugee experience highlighted Scotland's relative openness compared to stricter UK policies elsewhere, though bureaucratic hurdles and occasional local resentment persisted until Allied victory in 1945.[14]Post-War Institutional Development

In the immediate post-war years, the Scottish Jewish community focused on welfare infrastructure to address the needs of survivors, veterans, and an aging population, with Newark Lodge, a Jewish old age home, opening in Pollokshields, Glasgow, in 1949 to provide residential care; it subsequently relocated to Giffnock and later Newton Mearns amid suburbanization.[27] The Association of Jewish Ex-Servicemen and Women (AJEX) maintained active involvement in commemorations and community events, reflecting the contributions of Jewish servicemen during the war.[2] Educational development marked a significant institutional milestone with the establishment of Calderwood Lodge Primary School in Glasgow in 1962, initiated by the Glasgow Zionist Organisation and the Board of Jewish Education as Scotland's first dedicated Jewish day school, offering integrated Jewish studies and secular curriculum to counter assimilation pressures and support communal continuity; it enrolled pupils from the growing suburban communities and was incorporated into the state system in 1982 while preserving its religious ethos through dedicated funding.[27][2] This initiative responded to the community's peak population of approximately 18,000 in the 1950s, concentrated in Greater Glasgow, enabling formalized Jewish education previously limited to supplementary classes.[41] Synagogue infrastructure adapted to demographic shifts, with pre-existing congregations like Giffnock and Newlands expanding facilities post-war to include a mikvah, kollel for advanced Torah study, and a community centre, accommodating migration from inner-city Gorbals to southern suburbs and sustaining religious observance for thousands.[27] In Dundee, the aging 1919 synagogue was demolished in 1973 under urban renewal, replaced by a modern facility in 1978 to serve the diminished but persistent local community.[2] Representative and archival bodies strengthened communal coordination and historical preservation; the Glasgow Jewish Representative Council, dating to 1914 and the oldest of its kind in Britain, amplified post-war efforts in advocacy, welfare oversight, and liaison with civic authorities for Glasgow's majority of Scottish Jews.[41] The Scottish Jewish Archives Centre opened in 1987 at Garnethill Synagogue, Glasgow's historic 1879 edifice, to document migration, religious life, and institutional records, serving as an educational resource amid declining numbers.[27] Jewish Care Scotland evolved to deliver expanded services, including day care and residential support, from bases like the Maccabi Centre in Giffnock.[27] These developments underscored a shift toward professionalized, localized institutions amid integration and gradual population stabilization, with later formations like the Scottish Council of Jewish Communities in 1999 addressing devolved governance and nationwide representation.[27][41]Contemporary Developments (Late 20th–21st Centuries)

Population Dynamics and Decline

The Jewish population in Scotland reached an estimated peak of approximately 18,000 in the 1950s, following influxes from Eastern Europe and earlier settlements, but began a sustained decline thereafter.[41] This contraction continued into the late 20th and early 21st centuries, with official census figures reflecting a drop from 6,448 self-identified Jews in 2001 to 5,887 in 2011 and 5,847 in 2022.[7] These numbers represent declines of 8.7% over the first decade and 0.7% over the second, amid Scotland's overall population growth.[7] Community estimates suggest actual figures may be higher due to undercounting in censuses—potentially by up to 33%—arising from reluctance to disclose religion or non-response to voluntary questions, placing the contemporary total closer to 7,000–10,000 individuals.[7][41]| Census Year | Jewish Population | Percentage Change from Prior Census |

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 6,448 | - |

| 2011 | 5,887 | -8.7% |

| 2022 | 5,847 | -0.7% |