Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tidal force

View on Wikipedia

The tidal force or tide-generating force is the difference in gravitational attraction between different points in a gravitational field, causing bodies to be pulled unevenly and as a result are being stretched towards the attraction. It is the differential force of gravity, the net between gravitational forces, the derivative of gravitational potential, the gradient of gravitational fields. Therefore tidal forces are a residual force, a secondary effect of gravity, highlighting its spatial elements, making the closer near-side more attracted than the more distant far-side.

This produces a range of tidal phenomena, such as ocean tides. Earth's tides are mainly produced by the relative close gravitational field of the Moon and to a lesser extent by the stronger, but further away gravitational field of the Sun. The ocean on the side of Earth facing the Moon is being pulled by the gravity of the Moon away from Earth's crust, while on the other side of Earth there the crust is being pulled away from the ocean, resulting in Earth being stretched, bulging on both sides, and having opposite high-tides. Tidal forces viewed from Earth, that is from a rotating reference frame, appear as centripetal and centrifugal forces, but are not caused by the rotation.[2]

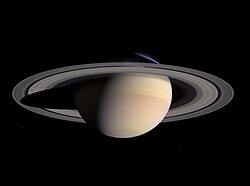

Further tidal phenomena include solid-earth tides, tidal locking, breaking apart of celestial bodies and formation of ring systems within the Roche limit, and in extreme cases, spaghettification of objects. Tidal forces have also been shown to be fundamentally related to gravitational waves.[3]

In celestial mechanics, the expression tidal force can refer to a situation in which a body or material (for example, tidal water) is mainly under the gravitational influence of a second body (for example, the Earth), but is also perturbed by the gravitational effects of a third body (for example, the Moon). The perturbing force is sometimes in such cases called a tidal force[4] (for example, the perturbing force on the Moon): it is the difference between the force exerted by the third body on the second and the force exerted by the third body on the first.[5]

Explanation

[edit]

When a body (body 1) is acted on by the gravity of another body (body 2), the field can vary significantly on body 1 between the side of the body facing body 2 and the side facing away from body 2. Figure 2 shows the differential force of gravity on a spherical body (body 1) exerted by another body (body 2).

These tidal forces cause strains on both bodies and may distort them or even, in extreme cases, break one or the other apart.[6] The Roche limit is the distance from a planet at which tidal effects would cause an object to disintegrate because the differential force of gravity from the planet overcomes the attraction of the parts of the object for one another.[7] These strains would not occur if the gravitational field were uniform, because a uniform field only causes the entire body to accelerate together in the same direction and at the same rate.

Size and distance

[edit]The relationship of an astronomical body's size, to its distance from another body, strongly influences the magnitude of tidal force.[8] The tidal force acting on an astronomical body, such as the Earth, is directly proportional to the diameter of the Earth and inversely proportional to the cube of the distance from another body producing a gravitational attraction, such as the Moon or the Sun. Tidal action on bath tubs, swimming pools, lakes, and other small bodies of water is negligible.[9]

Figure 3 is a graph showing how gravitational force declines with distance. In this graph, the attractive force decreases in proportion to the square of the distance (Y = 1/X2), while the slope (Y′ = −2/X3) is inversely proportional to the cube of the distance.

The tidal force corresponds to the difference in Y between two points on the graph, with one point on the near side of the body, and the other point on the far side. The tidal force becomes larger, when the two points are either farther apart, or when they are more to the left on the graph, meaning closer to the attracting body.

For example, even though the Sun has a stronger overall gravitational pull on Earth, the Moon creates a larger tidal bulge because the Moon is closer. This difference is due to the way gravity weakens with distance: the Moon's closer proximity creates a steeper decline in its gravitational pull as you move across Earth (compared to the Sun's very gradual decline from its vast distance). This steeper gradient in the Moon's pull results in a larger difference in force between the near and far sides of Earth, which is what creates the bigger tidal bulge.

Gravitational attraction is inversely proportional to the square of the distance from the source. The attraction will be stronger on the side of a body facing the source, and weaker on the side away from the source. The tidal force is proportional to the difference.[9]

Sun, Earth, and Moon

[edit]The Sun is about 20 million times the Moon's mass, and acts on the Earth over a distance about 400 times larger than that of the Moon. Because of the cubic dependence on distance, this results in the solar tidal force on the Earth being about half that of the lunar tidal force.

| Gravitational body causing tidal force | Body subjected to tidal force | Tidal acceleration | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body | Mass () | Body | Radius () | Distance () | |

| Sun | 1.99×1030 kg | Earth | 6.37×106 m | 1.50×1011 m | 5.05×10−7 m⋅s−2 |

| Moon | 7.34×1022 kg | Earth | 6.37×106 m | 3.84×108 m | 1.10×10−6 m⋅s−2 |

| Earth | 5.97×1024 kg | Moon | 1.74×106 m | 3.84×108 m | 2.44×10−5 m⋅s−2 |

| G is the gravitational constant = 6.674×10−11 m3⋅kg−1⋅s−2[10] | |||||

Effects

[edit]

In the case of an infinitesimally small elastic sphere, the effect of a tidal force is to distort the shape of the body without any change in volume. The sphere becomes an ellipsoid with two bulges, pointing towards and away from the other body. Larger objects distort into an ovoid, and are slightly compressed, which is what happens to the Earth's oceans under the action of the Moon. All parts of the Earth are subject to the Moon's gravitational forces, causing the water in the oceans to redistribute, forming bulges on the sides near the Moon and far from the Moon.[12]

When a body rotates while subject to tidal forces, internal friction results in the gradual dissipation of its rotational kinetic energy as heat. In the case for the Earth, and Earth's Moon, the loss of rotational kinetic energy results in a gain of about 2 milliseconds per century. If the body is close enough to its primary, this can result in a rotation which is tidally locked to the orbital motion, as in the case of the Earth's moon. Tidal heating produces dramatic volcanic effects on Jupiter's moon Io. Stresses caused by tidal forces also cause a regular monthly pattern of moonquakes on Earth's Moon.[8]

Tidal forces contribute to ocean currents, which moderate global temperatures by transporting heat energy toward the poles. It has been suggested that variations in tidal forces correlate with cool periods in the global temperature record at 6- to 10-year intervals,[13] and that harmonic beat variations in tidal forcing may contribute to millennial climate changes. No strong link to millennial climate changes has been found to date.[14]

Tidal effects become particularly pronounced near small bodies of high mass, such as neutron stars or black holes, where they are responsible for the "spaghettification" of infalling matter. Tidal forces create the oceanic tide of Earth's oceans, where the attracting bodies are the Moon and, to a lesser extent, the Sun. Tidal forces are also responsible for tidal locking, tidal acceleration, and tidal heating. Tides may also induce seismicity.

By generating conducting fluids within the interior of the Earth, tidal forces also affect the Earth's magnetic field.[15]

Formulation

[edit]

For a given (externally generated) gravitational field, the tidal acceleration at a point with respect to a body is obtained by vector subtraction of the gravitational acceleration at the center of the body (due to the given externally generated field) from the gravitational acceleration (due to the same field) at the given point. Correspondingly, the term tidal force is used to describe the forces due to tidal acceleration. Note that for these purposes the only gravitational field considered is the external one; the gravitational field of the body (as shown in the graphic) is not relevant. (In other words, the comparison is with the conditions at the given point as they would be if there were no externally generated field acting unequally at the given point and at the center of the reference body. The externally generated field is usually that produced by a perturbing third body, often the Sun or the Moon in the frequent example-cases of points on or above the Earth's surface in a geocentric reference frame.)

Tidal acceleration does not require rotation or orbiting bodies; for example, the body may be freefalling in a straight line under the influence of a gravitational field while still being influenced by (changing) tidal acceleration.

By Newton's law of universal gravitation and laws of motion, a body of mass m at distance R from the center of a sphere of mass M feels a force ,

equivalent to an acceleration ,

where is a unit vector pointing from the body M to the body m (here, acceleration from m towards M has negative sign).

Consider now the acceleration due to the sphere of mass M experienced by a particle in the vicinity of the body of mass m. With R as the distance from the center of M to the center of m, let ∆r be the (relatively small) distance of the particle from the center of the body of mass m. For simplicity, distances are first considered only in the direction pointing towards or away from the sphere of mass M. If the body of mass m is itself a sphere of radius ∆r, then the new particle considered may be located on its surface, at a distance (R ± ∆r) from the centre of the sphere of mass M, and ∆r may be taken as positive where the particle's distance from M is greater than R. Leaving aside whatever gravitational acceleration may be experienced by the particle towards m on account of m's own mass, we have the acceleration on the particle due to gravitational force towards M as:

Pulling out the R2 term from the denominator gives:

The Maclaurin series of is which gives a series expansion of:

The first term is the gravitational acceleration due to M at the center of the reference body , i.e., at the point where is zero. This term does not affect the observed acceleration of particles on the surface of m because with respect to M, m (and everything on its surface) is in free fall. When the force on the far particle is subtracted from the force on the near particle, this first term cancels, as do all other even-order terms. The remaining (residual) terms represent the difference mentioned above and are tidal force (acceleration) terms. When ∆r is small compared to R, the terms after the first residual term are very small and can be neglected, giving the approximate tidal acceleration for the distances ∆r considered, along the axis joining the centers of m and M:

When calculated in this way for the case where ∆r is a distance along the axis joining the centers of m and M, is directed outwards from to the center of m (where ∆r is zero).

Tidal accelerations can also be calculated away from the axis connecting the bodies m and M, requiring a vector calculation. In the plane perpendicular to that axis, the tidal acceleration is directed inwards (towards the center where ∆r is zero), and its magnitude is in linear approximation as in Figure 2.

The tidal accelerations at the surfaces of planets in the Solar System are generally very small. For example, the lunar tidal acceleration at the Earth's surface along the Moon–Earth axis is about 1.1×10−7 g, while the solar tidal acceleration at the Earth's surface along the Sun–Earth axis is about 0.52×10−7 g, where g is the gravitational acceleration at the Earth's surface. Hence the tide-raising force (acceleration) due to the Sun is about 45% of that due to the Moon.[17] The solar tidal acceleration at the Earth's surface was first given by Newton in the Principia.[18]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Hubble Views a Cosmic Interaction". nasa.gov. NASA. February 11, 2022. Retrieved 2022-07-09.

- ^ Matsuda, Takuya; Isaka, Hiromu; Boffin, Henri M. J. (2015), Confusion around the tidal force and the centrifugal force, arXiv:1506.04085, retrieved 2025-02-14

- ^ arXiv, Emerging Technology from the (2019-12-14). "Tidal forces carry the mathematical signature of gravitational waves". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 2023-11-12.

- ^ "On the tidal force", I. N. Avsiuk, in "Soviet Astronomy Letters", vol. 3 (1977), pp. 96–99.

- ^ See p. 509 in "Astronomy: a physical perspective", M. L. Kutner (2003).

- ^

R Penrose (1999). The Emperor's New Mind: Concerning Computers, Minds, and the Laws of Physics. Oxford University Press. p. 264. ISBN 978-0-19-286198-6.

tidal force.

- ^ Thérèse Encrenaz; J -P Bibring; M Blanc (2003). The Solar System. Springer. p. 16. ISBN 978-3-540-00241-3.

- ^ a b "The Tidal Force | Neil deGrasse Tyson". www.haydenplanetarium.org. Retrieved 2016-10-10.

- ^ a b Sawicki, Mikolaj (1999). "Myths about gravity and tides". The Physics Teacher. 37 (7): 438–441. Bibcode:1999PhTea..37..438S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.695.8981. doi:10.1119/1.880345. ISSN 0031-921X.

- ^ "2022 CODATA Value: Newtonian constant of gravitation". The NIST Reference on Constants, Units, and Uncertainty. NIST. May 2024. Retrieved 2024-05-18.

- ^ R. S. MacKay; J. D. Meiss (1987). Hamiltonian Dynamical Systems: A Reprint Selection. CRC Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-85274-205-1.

- ^ Rollin A Harris (1920). The Encyclopedia Americana: A Library of Universal Knowledge. Vol. 26. Encyclopedia Americana Corp. pp. 611–617.

- ^ Keeling, C. D.; Whorf, T. P. (5 August 1997). "Possible forcing of global temperature by the oceanic tides". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 94 (16): 8321–8328. Bibcode:1997PNAS...94.8321K. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.16.8321. PMC 33744. PMID 11607740.

- ^ Munk, Walter; Dzieciuch, Matthew; Jayne, Steven (February 2002). "Millennial Climate Variability: Is There a Tidal Connection?". Journal of Climate. 15 (4): 370–385. Bibcode:2002JCli...15..370M. doi:10.1175/1520-0442(2002)015<0370:MCVITA>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ "Hungry for Power in Space". New Scientist. 123: 52. 23 September 1989. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ "Inseparable galactic twins". ESA/Hubble Picture of the Week. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ The Admiralty (1987). Admiralty manual of navigation. Vol. 1. The Stationery Office. p. 277. ISBN 978-0-11-772880-6., Chapter 11, p. 277

- ^

Newton, Isaac (1729). The mathematical principles of natural philosophy. Vol. 2. p. 307. ISBN 978-0-11-772880-6.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help), Book 3, Proposition 36, Page 307 Newton put the force to depress the sea at places 90 degrees distant from the Sun at "1 to 38604600" (in terms of g), and wrote that the force to raise the sea along the Sun-Earth axis is "twice as great" (i.e., 2 to 38604600) which comes to about 0.52 × 10−7 g as expressed in the text.

External links

[edit]- Analysis and Prediction of Tides: GeoTide

- Gravitational Tides by J. Christopher Mihos of Case Western Reserve University

- Audio: Cain/Gay – Astronomy Cast Tidal Forces – July 2007.

- Gray, Meghan; Merrifield, Michael. "Tidal Forces". Sixty Symbols. Brady Haran for the University of Nottingham.

- Pau Amaro Seoane. "Stellar collisions: Tidal disruption of a star by a massive black hole". Retrieved 2018-12-28.

- Myths about Gravity and Tides by Mikolaj Sawicki of John A. Logan College and the University of Colorado.

- Tidal Misconceptions by Donald E. Simanek

- Tides and centrifugal force by Paolo Sirtoli

Tidal force

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Basic Concept

Tidal force refers to the differential gravitational attraction experienced by different parts of an extended body due to the varying strength of gravity from a distant massive object, resulting in a tendency for the body to stretch along the line connecting the centers of mass or compress perpendicular to it.[1] This arises because gravity does not act uniformly across the body's extent but weakens with distance according to the inverse-square law, creating a net force that deforms rather than simply accelerates the body as a whole.[6] To illustrate, consider a simple thought experiment involving an astronaut in a spacecraft approaching Earth: the gravitational pull on the astronaut's feet, closer to the planet, is slightly stronger than on their head, causing a subtle stretching effect as the body aligns with the gravitational gradient.[7] This contrasts with a uniform gravitational field, where every part of the body experiences the same acceleration, leading to no relative deformation—much like free fall in a small elevator where objects inside float weightlessly together.[8] At its foundation, tidal force stems from Newton's law of universal gravitation, which describes the attractive force between two masses as proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between their centers.[3] Unlike the overall gravitational force on a point mass, which follows an inverse-square dependence on distance, the tidal force—being a difference across a finite separation—varies inversely with the cube of the distance, making it significant only when the attracting body is relatively close compared to its size.[3] Mathematical formulations of this concept, such as the tidal potential, provide a precise framework for quantifying these effects.[6]Historical Development

Early observations of tides date back to ancient civilizations, where scholars linked tidal cycles to lunar phases. Aristotle (384–322 BCE) noted a connection between tides and the Moon, though he attributed the phenomenon primarily to winds and the Earth's rocky coastline rather than gravitational pull.[9] By the 2nd century BCE, Seleucus of Seleucia proposed that tides were caused by the Moon's position, observing diurnal inequalities in the Red Sea and aligning tidal maxima with lunar phases.[10] Ptolemy (c. 100–170 CE) further attributed tides to a "virtue or power" exerted by the Moon on terrestrial waters, incorporating these ideas into his geocentric model without detailed mechanics.[11] The modern theoretical foundation for tidal forces emerged in the late 17th century with Isaac Newton's work. In his Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687), Newton explained tidal bulges as resulting from the differential gravitational attractions of the Moon and Sun on Earth's oceans, combined with centrifugal effects from Earth's rotation, marking the first comprehensive gravitational basis for tides.[12] This equilibrium theory predicted two high tides per lunar day, with amplitudes varying by lunar phase, though it idealized oceans as static and underestimated complexities like friction.[13] Advancements in the 18th and 19th centuries refined Newton's ideas into more dynamic models. Pierre-Simon Laplace, building on equilibrium theory in the 1770s–1790s and detailed in Mécanique Céleste (1799–1825), incorporated Earth's rotation and ocean hydrodynamics, developing equations that separated tides into long-period, diurnal, and semidiurnal components while analyzing real tidal data from sites like Brest, France.[14] In the 1880s, George Darwin advanced dynamical theory through harmonic analysis, studying tidal friction's role in Earth-Moon evolution and confirming Earth tides via long-term observations, as published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society (e.g., 1887 paper on long-period tides).[15][13] Twentieth-century efforts confirmed tidal theory through direct measurements, including satellite data. The Apollo missions (1969–1972) deployed instruments, including passive seismometers and the Lunar Surface Gravimeter, that recorded tidal-related moonquakes and gravity variations associated with Earth-induced lunar tides, validating predictions of tidal deformation on airless bodies.[16][17] Tidal forces, conceptualized over two centuries before general relativity, align with Einstein's framework in weak-field approximations, where the Riemann curvature tensor reduces to the Newtonian tidal tensor.[18]Physical Principles

Gravitational Basis

Tidal forces originate from the spatial variation in the gravitational field produced by a massive body, where the field's strength decreases according to the inverse-square law with increasing distance from the source.[19] This gradient results in a stronger gravitational pull on the portion of an extended body closer to the gravitating mass compared to the farther portion, creating differential accelerations across the body's extent.[20] For instance, points nearer the source experience greater attraction, while those farther away are pulled less intensely, leading to a stretching effect along the line connecting the centers of the two bodies.[21] The net gravitational force on the extended body can be decomposed into a uniform component, which acts equally on all parts as if applied at the center of mass, and a tidal component representing the deviation due to the field's gradient.[20] The uniform component accelerates the entire body as a whole toward the gravitating mass, but the tidal component—effectively a "difference" force—varies across the body: it is zero at the center of mass, directed toward the source on the near side (enhancing the pull), and away from the source on the far side (due to the relative weakness of the field there).[19] This differential action qualitatively elongates the body along the axis toward the gravitating mass while compressing it perpendicularly, as the varying pulls create tension along that line.[22] In equilibrium tide theory, these forces lead to a static deformation in an isolated system, where the body adjusts to form a tidal ellipsoid with bulges aligned toward and away from the gravitating mass, balanced by internal pressure gradients.[23] This contrasts with dynamic tides, which involve time-varying responses due to orbital motion or rotation, but the foundational static case illustrates the pure gravitational basis.[23] Tidal forces apply to any extended body, regardless of composition, inducing stress that can deform solids as well as fluids; for example, they exert disruptive tidal stress on asteroids during close planetary encounters, potentially leading to fragmentation.[24]Differential Forces

Tidal forces arise from the nonuniform gravitational field of a massive body acting on an extended object, leading to the formation of two characteristic bulges. The bulge on the near side forms because points closer to the perturbing body experience a stronger gravitational attraction than the object's center, pulling material outward relative to the center. Conversely, the far-side bulge develops as points farther away are attracted less strongly, resulting in a net outward displacement compared to the center. These bulges align along the line connecting the centers of the two bodies and lie in the orbital plane, creating an elongated prolate spheroid aligned along the line connecting the centers of the two bodies in non-rotating approximations.[25] In addition to radial elongation, tidal forces induce compression in the transverse directions perpendicular to the line of centers. This squeezing effect occurs because the gravitational acceleration decreases with distance, causing points offset laterally from the center line to experience a component of force directed toward the axis, effectively compressing the body along its equatorial plane while it stretches radially. The overall pattern resembles a stretching along one axis and crushing orthogonally, often described as the "noodle" or tidal distortion effect.[26] The extent of tidal deformation depends on the size of the affected body, as larger separations between points within the body amplify the differential gravitational forces acting across it. For instance, extended objects like planets or moons exhibit more pronounced bulges than compact ones, since the gradient in the gravitational field integrates over greater distances. Qualitatively, these differentials generate normal stresses that produce tension along the radial axis and compression transversely, alongside shear stresses that promote internal shearing and potential fracturing without specifying magnitudes.[26][27] In rotating systems, such as planets with significant spin, the Coriolis effect modifies the differential tidal forces by deflecting moving material perpendicular to its velocity, leading to dynamic asymmetries in the bulge positions and shapes. This interaction causes the tidal response to deviate from equilibrium, introducing phase lags and rotational distortions in the deformation pattern.[28]Mathematical Description

Tidal Potential

The tidal potential represents the scalar gravitational potential variation across an extended body due to the differential gravitational field of a distant point mass, such as a moon or planet, and serves as the mathematical foundation for describing tidal forces. In the multipole expansion of the gravitational potential from the external mass located at a large distance from the body's center, the potential at a point within the body (where ) is expressed as with denoting the Legendre polynomials of degree and the angle between and the position vector to the external mass.[29] The tidal potential isolates the differential effects by subtracting the uniform monopole () term, which is constant and exerts no force, and the dipole () term, which represents a uniform field equivalent to the acceleration of the body's center of mass. This leaves the higher-order terms, with the leading quadrupole () term dominating: where . Higher-order terms () are negligible for most astrophysical contexts, as decreases rapidly for when the body is compact relative to the separation.[29][30] The tidal force per unit mass, or tidal acceleration, arises as the negative gradient of this potential: . This yields a vector field that elongates the body along the axis toward the external mass (where or , ) and compresses it in the perpendicular directions (where , ), consistent with observed tidal bulges.[29] This formulation of the tidal potential is frame-dependent, as the subtraction of the uniform terms relies on the choice of reference frame, but it becomes invariant when evaluated in the body's center-of-mass frame, where the net force on the center vanishes by construction.[29]Tidal Acceleration Formula

The tidal acceleration arises from the differential gravitational field across an extended body, such as a planet, due to a distant mass. To derive it, consider the gravitational acceleration produced by a point mass at a large distance from the body's center of mass, evaluated at a displacement from that center where . The acceleration at the center is , and the relative tidal acceleration is obtained via a first-order Taylor expansion: . This linear approximation captures the dominant tidal effect, neglecting higher-order terms.[31][32] In the simplified one-dimensional case along the line connecting the centers (taken as the radial direction toward ), for a small separation from the body's center, the tidal acceleration is . This expression shows that the relative acceleration stretches the body along the line, with the near side experiencing an additional pull toward and the far side a reduced pull, resulting in both sides moving away from the center relative to the uniform field.[31][33] The full three-dimensional vector form relates to the tidal potential from the previous section, with . Assuming the perturber lies along the positive -axis at distance , the Cartesian components of the tidal acceleration at position are: This form indicates elongation along the -direction (toward and away from ) and compression in the perpendicular - plane, consistent with the quadrupolar nature of the tidal field.[29][32] The magnitude of the tidal acceleration scales with the inverse cube of the distance to the perturber, as , emphasizing that tidal effects weaken rapidly with separation despite the perturber's mass. For the Earth-Moon system, this inverse-cube dependence makes the Moon's tidal influence dominant over the Sun's, as the Moon's closer proximity more than compensates for the Sun's greater mass.[1][31] This formula assumes the perturber is a point mass; for extended bodies with significant size relative to , the tidal acceleration requires integrating the gravitational field over the perturber's mass distribution.[29]Applications in the Earth-Moon-Sun System

Moon's Tidal Influence on Earth

The Moon's mass is kg, and it orbits Earth at an average distance of 384,400 km.[34][35] These parameters produce a differential gravitational force that results in a tidal acceleration of approximately m/s² across Earth's surface.[36] This acceleration arises from the inverse-cube dependence of tidal forces on distance, making the Moon's influence dominant despite the Sun's greater overall gravity, with the lunar tidal force about 2.2 times stronger than the solar contribution at Earth.[37] In the equilibrium theory of tides, the Moon induces semi-diurnal bulges in Earth's oceans, with a theoretical amplitude of roughly 0.5 m at the equator.[38] However, actual tidal heights are amplified by dynamic effects, including ocean basin resonances and coastal geometry, reaching up to 16 m in extreme cases such as the Bay of Fundy.[39] These bulges align with the Earth-Moon line, creating two high tides daily as Earth rotates beneath them. The Moon's sidereal orbital period is 27.3 days, while Earth rotates once every 24 hours, leading to a lunar day of 24 hours and 50 minutes—the interval between successive moonrises or high tides at a given location.[41] This mismatch drives the semi-diurnal tidal cycle, with orbital resonance ensuring consistent twice-daily peaks. Tidal friction, primarily from ocean currents interacting with the bulges, dissipates rotational energy, slowing Earth's spin by about 2.3 milliseconds per century.[38] This process transfers angular momentum to the Moon's orbit, gradually increasing its distance from Earth at a rate of approximately 3.8 cm per year.Sun's Tidal Contribution

The Sun, with a mass of kg and an average distance from Earth of 149.6 million km, exerts a tidal acceleration on Earth of approximately m/s².[43][36] This value represents about 46% of the Moon's tidal acceleration of roughly m/s².[36][44] Despite the Sun's mass being vastly greater than the Moon's, its much larger distance results in a weaker tidal influence, underscoring the inverse-cube scaling of tidal forces with distance.[3] The Sun's tidal effects interact with those of the Moon through vector addition, modulating the overall tidal pattern in the Earth-Moon-Sun system. When the Sun, Moon, and Earth are aligned—during new and full moons—the solar tides reinforce the lunar tides, producing spring tides with enhanced high and low water levels. In contrast, during the first and third quarter moons, when the Sun and Moon are positioned at right angles relative to Earth, the solar tides partially oppose the lunar tides, leading to neap tides with reduced range. This interference results in a variation of approximately 20% in the tidal range between spring and neap conditions.[45] Over long timescales, the Sun's gravitational tides contribute to the gradual slowing of Earth's rotation, though this effect is less dominant than the lunar contribution. Solar tides account for roughly one-third of the total tidal deceleration, compared to two-thirds from lunar tides, primarily through frictional dissipation in Earth's oceans and atmosphere.[46]Observable Effects

Oceanic Tides

Oceanic tides arise primarily from the differential gravitational forces exerted by the Moon and Sun on Earth's oceans, creating two theoretical bulges of water: one facing the perturbing body and the other on the opposite side of Earth.[47] In the equilibrium tide model, proposed by Isaac Newton and later refined, a hypothetical global ocean covering a rigid, non-rotating Earth would respond instantaneously to these forces, resulting in a static tidal deformation that follows the Moon's or Sun's position.[23] As Earth rotates beneath this deformation, coastal locations experience two high tides and two low tides each lunar day (approximately 24 hours and 50 minutes), with the Moon's influence dominating due to its proximity, contributing about 2.2 times the tidal force of the Sun.[47] This model predicts a tidal range of less than 1 meter for the Moon alone in an idealized ocean, though real ranges vary widely.[45] In reality, oceanic tides deviate significantly from the equilibrium model due to Earth's rotation, irregular bathymetry, continental barriers, and the Coriolis effect, leading to dynamic tides that amplify and distort the basic pattern.[45] Shallow coastal seas and enclosed basins funnel and resonate tidal waves, often increasing amplitudes by factors of 10 or more compared to the open ocean equilibrium prediction; for instance, the English Channel experiences heightened semidiurnal tides due to its geometry.[45] The Coriolis force introduces rotational components, forming amphidromic systems in semi-enclosed regions like the North Sea, where tides propagate as rotating waves around a central node of zero amplitude, with cotidal lines radiating outward.[48] These dynamic interactions result in complex tidal patterns that can lag or lead the equilibrium tide by hours, depending on local geography.[49] Tidal cycles are classified into three main types based on the number and equality of daily highs and lows: semidiurnal, diurnal, and mixed.[50] Semidiurnal tides, common along the U.S. East Coast and in the English Channel, feature two high tides and two low tides per day of approximately equal height, driven predominantly by the Moon's M2 constituent with a period of about 12.4 hours.[50] Diurnal tides, characterized by one high and one low tide daily, prevail in regions like the Gulf of Mexico and parts of Southeast Asia, where the Sun's K1 and Moon's O1 constituents dominate due to resonance in broad, shallow basins.[50] Mixed tides, blending elements of both, occur widely on the U.S. West Coast and in the Pacific, with successive high tides of unequal height reflecting interference between semidiurnal and diurnal components.[50] These variations arise from local bathymetric and frictional effects that selectively amplify certain tidal harmonics.[51] Tidal heights and patterns are measured using a combination of in-situ tide gauges and satellite altimetry, providing both local and global insights.[52] Tide gauges, deployed at over 2,000 coastal stations worldwide by organizations like NOAA, record water levels continuously to capture site-specific cycles and extremes, essential for navigation and coastal engineering.[52] Satellite missions, such as NASA's TOPEX/Poseidon launched in 1992, use radar altimetry to map sea surface heights globally every 10 days, revealing basin-scale tidal patterns and confirming the dominance of semidiurnal waves in the deep ocean with amplitudes up to 0.5 meters. More recent missions, such as the Surface Water and Ocean Topography (SWOT) satellite launched in 2022, continue to refine global tidal mapping with higher resolution data.[53][54] These observations have mapped amphidromic systems across oceans, showing how tides propagate as Kelvin and Poincaré waves influenced by Earth's rotation.[53] The global tidal energy input from the Moon and Sun totals approximately 3.7 terawatts (TW), with the vast majority dissipated in the oceans through friction and turbulence, primarily in shallow marginal seas.[55] This dissipation drives vertical mixing in the water column, enhancing nutrient upwelling from deeper layers to support marine ecosystems, and contributes to about 10% of the ocean's overall energy budget for internal wave generation.[56] Seminal estimates from satellite data and models indicate that roughly 2.5 TW is associated with the principal lunar semidiurnal tide alone, underscoring its role in oceanic circulation.[55]Geological and Solid-Body Deformations

Tidal forces induce elastic deformations in the solid Earth, known as solid Earth tides, which cause the planet's surface to bulge and subside periodically. These deformations reach vertical amplitudes of up to approximately 30 cm, primarily driven by the Moon's gravitational pull during semidiurnal cycles, and are detectable using high-precision gravimeters and GPS instruments. The Earth's response is characterized by Love numbers, dimensionless parameters that describe its rigidity; the second-degree vertical Love number is approximately 0.60, indicating moderate elasticity compared to a fully rigid body.[25][57][58] These tidal deformations impose periodic stresses on the Earth's crust, on the order of kilopascals, which can influence seismic activity in critically stressed regions. Micro-earthquakes, particularly those with magnitudes below 2.5, show statistically significant correlations with tidal stress peaks, where extensional or shear components align with fault orientations to promote slip. For instance, at mid-ocean ridges, earthquakes cluster during low tides when tidal stresses maximize horizontal extension. In volcanic settings, tidal modulation has been linked to heightened activity; studies from the 1960s onward, including analyses at Mount Etna, Italy, revealed alignments between eruption onsets and tidal maxima, suggesting that tidal strains of a few microstrains can trigger magma movement in conduit systems.[59][60] Beyond Earth, tidal forces cause pronounced solid-body deformations in other celestial bodies, often leading to internal heating through frictional dissipation. Jupiter's moon Io experiences extreme tidal flexing due to its 1:2:4 orbital resonance with Europa and Ganymede, resulting in surface height variations of up to 100 m along the sub-Jovian axis. This repeated deformation generates heat fluxes exceeding 100 TW, powering over 400 active volcanoes and making Io the most volcanically active body in the Solar System. Similarly, Saturn's moon Enceladus undergoes tidal kneading from its eccentric orbit and 2:1 resonance with Dione, dissipating energy in its icy shell and rocky core to maintain a subsurface ocean; this process sustains south polar geysers by driving hydrothermal circulation and fracturing, with observed plume activity varying on tidal timescales.[61][62][63][64] Over geological timescales, tidal deformations leave imprints in the rock record, particularly in sedimentary strata formed near ancient coastlines. Tidal rhythmites—layered deposits reflecting neap-spring cycles—preserve evidence of past tidal ranges and periods, which were modulated by supercontinent configurations like Rodinia or Pangaea that altered ocean basin geometries and resonance properties. For example, Proterozoic strata show enhanced tidal signatures during supercontinent dispersal, with bundle thicknesses indicating stronger tides than today due to closer lunar distances. These records provide proxies for Earth's rotational history and orbital evolution.[65][66][67] The viscoelastic properties of the Earth's mantle cause solid tides to lag the driving tidal potential by a small phase angle, typically 0.2° for semidiurnal components, equivalent to about 25 seconds, reflecting minor energy dissipation. In contrast, oceanic (fluid) tides lag the equilibrium position by 1–2 hours on average due to frictional drag and basin resonances, resulting in solid tides preceding fluid tides in phase. This differential lag arises from the solid Earth's higher rigidity and the oceans' dynamic response.[68][69]Broader Astrophysical Implications

Tidal Locking and Synchronization

Tidal locking arises from the gravitational interaction between two orbiting bodies, where tidal forces distort the less massive body into elongated bulges that do not perfectly align with the line connecting the centers of mass. If the body's rotation is initially faster than its orbital period, these bulges lag behind, generating a torque that transfers angular momentum from the spin to the orbit, progressively slowing the rotation while expanding the semi-major axis until a synchronous 1:1 resonance is achieved, with rotation matching the orbital period.[4] This process relies on internal friction dissipating energy as heat within the body, converting rotational kinetic energy into orbital energy and heat.[4] In the Earth-Moon system, the Moon exemplifies this synchronization, having achieved tidal locking early in its history—within hundreds of thousands of years after formation—such that it always presents the same hemisphere to Earth.[4] Similarly, the Pluto-Charon system demonstrates mutual tidal locking, where both bodies are synchronized to each other, each rotating once per orbital period around their common center of mass, a configuration stabilized by their comparable masses and close proximity.[4] Mercury provides a variant case, captured into a stable 3:2 spin-orbit resonance with the Sun due to tidal torques and orbital eccentricity, rotating three times for every two orbits. The timescales for achieving such resonances vary with system parameters like separation, mass ratio, and dissipation rates; for large moons like those of Jupiter and Saturn, locking occurs rapidly post-formation, often within millions of years.[4] In the ongoing Earth-Moon evolution, tidal friction—linked to the Moon's influence on Earth's oceans and solid body—drives the Moon's recession at approximately 3.8 cm per year, gradually transferring Earth's rotational energy to the orbit.[70] All large moons in the solar system are tidally locked to their primaries, a prevalence that extends to close binary star systems where synchronization is nearly ubiquitous.[4]Tidal Disruption and Roche Limit

Tidal disruption occurs when a smaller celestial body approaches a more massive primary too closely, causing the differential gravitational forces—known as tidal forces—to overcome the body's self-gravity, leading to its structural breakup. This phenomenon is quantified by the Roche limit, the critical distance from the primary beyond which the smaller body remains intact. Within this limit, the tidal acceleration across the body's diameter exceeds its surface gravitational binding, stretching and fragmenting it into streams of debris.[71] The Roche limit for a fluid body, assuming no rotation and negligible cohesion, is given bywhere is the radius of the primary body with density , and is the density of the secondary body. This formula arises from equating the tidal acceleration difference across the secondary's diameter to its self-gravitational acceleration at the surface. Specifically, the tidal field from the primary produces a relative acceleration of approximately , where is the primary's mass and is the secondary's radius; setting this equal to the secondary's surface gravity (with its mass) and substituting densities yields the distance . For rigid bodies, which resist deformation better, the limit is smaller, approximately , as the body can withstand greater tidal stress before fracturing.[72][71] A prominent example of tidal disruption is the breakup of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 in 1992, when it passed within about 1.3 Jupiter radii of the planet's center—well inside Jupiter's Roche limit of approximately 3 Jupiter radii for the comet's low density—splitting into multiple fragments that later impacted Jupiter in 1994. Theoretical models suggest Saturn's rings formed from similar tidal disruption of an icy moon or planetesimal that ventured inside Saturn's Roche limit around 100–200 million years ago, with the resulting debris spreading into a stable disk due to the planet's low density and oblateness. Following disruption, the ejected material often forms elongated tidal streams that can evolve into rings, accretion disks, or further scatter, depending on the geometry and orbital dynamics. Stability of such debris is governed by the Hill sphere, the region around the secondary where its gravity dominates over the primary's tidal perturbations; material escaping this sphere during breakup contributes to broader streams, while bound portions coalesce within it. In the context of neutron star mergers, tidal disruption effects are parameterized by the dimensionless tidal deformability , which measures how easily the stars deform under mutual tides before coalescing; observations of the GW170817 event in 2017 constrained the effective at 90% confidence, indicating compact neutron stars resistant to extreme tidal stretching and supporting equation-of-state models with radii around 11–13 km.[73][74]

References

- https://science.[nasa](/page/NASA).gov/moon/facts/

- https://science.[nasa](/page/NASA).gov/moon/tidal-locking/