Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Locomotive

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2022) |

| Part of a series on |

| Rail transport |

|---|

|

|

|

| Infrastructure |

|

|

| Rolling stock |

|

|

| Urban rail transit |

|

|

| Other topics |

|

|

A locomotive is a rail vehicle that provides the motive power for a train. Traditionally, locomotives pulled trains from the front. However, push–pull operation has become common, and in the pursuit for longer and heavier freight trains, companies are increasingly using distributed power: single or multiple locomotives placed at the front and rear and at intermediate points throughout the train under the control of the leading locomotive.[1]

Etymology

[edit]The word locomotive originates from the Latin loco 'from a place', ablative of locus 'place', and the Medieval Latin motivus 'causing motion', and is a shortened form of the term locomotive engine,[2] which was first used in 1814[3] to distinguish between self-propelled and stationary steam engines.

Classifications

[edit]Prior to locomotives, the motive force for railways had been generated by various lower-technology methods such as human power, horse power, gravity or stationary engines that drove cable systems. Few such systems are still in existence today. Locomotives may generate their power from fuel (wood, coal, petroleum or natural gas), or they may take power from an outside source of electricity. It is common to classify locomotives by their source of energy. The common ones include:

Steam

[edit]A steam locomotive is a locomotive whose primary power source is a steam engine. The most common form of steam locomotive also contains a boiler to generate the steam used by the engine. The water in the boiler is heated by burning combustible material – usually coal, wood, or oil – to produce steam. The steam moves reciprocating pistons which are connected to the locomotive's main wheels, known as the "driving wheels". Both fuel and water supplies are carried with the locomotive, either on the locomotive itself, in bunkers and tanks, (this arrangement is known as a "tank locomotive") or pulled behind the locomotive, in tenders, (this arrangement is known as a "tender locomotive").

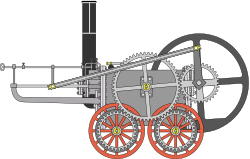

The first full-scale working railway steam locomotive was built by Richard Trevithick in 1802. It was constructed for the Coalbrookdale ironworks in Shropshire in England though no record of it working there has survived.[4] On 21 February 1804, the first recorded steam-hauled railway journey took place as another of Trevithick's locomotives hauled a train from the Penydarren ironworks, in Merthyr Tydfil, to Abercynon in South Wales.[5][6] Accompanied by Andrew Vivian, it ran with mixed success.[7] The design incorporated a number of important innovations including the use of high-pressure steam which reduced the weight of the engine and increased its efficiency.

In 1812, Matthew Murray's twin-cylinder rack locomotive Salamanca first ran on the edge-railed rack-and-pinion Middleton Railway;[8] this is generally regarded as the first commercially successful locomotive.[9][10] Another well-known early locomotive was Puffing Billy, built 1813–14 by engineer William Hedley for the Wylam Colliery near Newcastle upon Tyne. This locomotive is the oldest preserved, and is on static display in the Science Museum, London. George Stephenson built Locomotion No. 1 for the Stockton & Darlington Railway in the north-east of England, which was the first public steam railway in the world. In 1829, his son Robert built The Rocket in Newcastle upon Tyne. Rocket was entered into, and won, the Rainhill Trials. This success led to the company emerging as the pre-eminent early builder of steam locomotives used on railways in the UK, US and much of Europe.[11] The Liverpool & Manchester Railway, built by Stephenson, opened a year later making exclusive use of steam power for passenger and goods trains.

The steam locomotive remained by far the most common type of locomotive until after World War II.[12] Steam locomotives are less efficient than modern diesel and electric locomotives, and a significantly larger workforce is required to operate and service them.[13] British Rail figures showed that the cost of crewing and fuelling a steam locomotive was about two and a half times larger than the cost of supporting an equivalent diesel locomotive, and the daily mileage they could run was lower.[citation needed] Between about 1950 and 1970, the majority of steam locomotives were retired from commercial service and replaced with electric and diesel–electric locomotives.[14][15] While North America transitioned from steam during the 1950s, and continental Europe by the 1970s, in other parts of the world, the transition happened later. Steam was a familiar technology that used widely-available fuels and in low-wage economies did not suffer as wide a cost disparity. It continued to be used in many countries until the end of the 20th century. By the end of the 20th century, almost the only steam power remaining in regular use around the world was on heritage railways.

-

Trevithick's 1802 locomotive

-

The Locomotion No. 1 at Darlington Railway Centre and Museum

Internal combustion

[edit]

Internal combustion locomotives use an internal combustion engine, connected to the driving wheels by a transmission. They typically keep the engine running at a near-constant speed whether the locomotive is stationary or moving. Internal combustion locomotives are categorised by their fuel type and sub-categorised by their transmission type.

The first internal combustion rail vehicle was a kerosene-powered draisine built by Gottlieb Daimler in 1887,[16] but this was not technically a locomotive as it carried a payload.

The earliest gasoline locomotive in the western United States was built by the Best Manufacturing Company in 1891 for San Jose and Alum Rock Railroad. It was only a limited success and was returned to Best in 1892.[17]

The first commercially successful petrol locomotive in the United Kingdom was a petrol–mechanical locomotive built by the Maudslay Motor Company in 1902, for the Deptford Cattle Market in London. It was an 80 hp locomotive using a three-cylinder vertical petrol engine, with a two speed mechanical gearbox.

In 1903, the Hungarian Weitzer railmotor was the world's first petrol electric locomotive.

Diesel

[edit]Diesel locomotives are powered by diesel engines. In the early days of diesel propulsion development, various transmission systems were employed with varying degrees of success, with electric transmission proving to be the most popular. In 1914, Hermann Lemp, a General Electric electrical engineer, developed and patented a reliable direct current electrical control system (subsequent improvements were also patented by Lemp).[18] Lemp's design used a single lever to control both engine and generator in a coordinated fashion, and was the prototype for all diesel–electric locomotive control. In 1917–18, GE produced three experimental diesel–electric locomotives using Lemp's control design.[19] In 1924, a diesel–electric locomotive (Eel2 original number Юэ 001/Yu-e 001) started operations. It had been designed by a team led by Yury Lomonosov and built 1923–1924 by Maschinenfabrik Esslingen in Germany. It had five driving axles (1'E1'). After several test rides, it hauled trains for almost three decades from 1925 to 1954.[20]

Electric

[edit]

An electric locomotive is a locomotive powered only by electricity. Electricity is supplied to moving trains with a (nearly) continuous conductor running along the track that usually takes one of three forms: an overhead line, suspended from poles or towers along the track or from structure or tunnel ceilings; a third rail mounted at track level; or an onboard battery. Both overhead wire and third-rail systems usually use the running rails as the return conductor but some systems use a separate fourth rail for this purpose. The type of electrical power used is either direct current (DC) or alternating current (AC).

Various collection methods exist: a trolley pole, which is a long flexible pole that engages the line with a wheel or shoe; a bow collector, which is a frame that holds a long collecting rod against the wire; a pantograph, which is a hinged frame that holds the collecting shoes against the wire in a fixed geometry; or a contact shoe, which is a shoe in contact with the third rail. Of the three, the pantograph method is best suited for high-speed operation.

Electric locomotives almost universally use axle-hung traction motors, with one motor for each powered axle. In this arrangement, one side of the motor housing is supported by plain bearings riding on a ground and polished journal that is integral to the axle. The other side of the housing has a tongue-shaped protuberance that engages a matching slot in the truck (bogie) bolster, its purpose being to act as a torque reaction device, as well as a support. Power transfer from motor to axle is effected by spur gearing, in which a pinion on the motor shaft engages a bull gear on the axle. Both gears are enclosed in a liquid-tight housing containing lubricating oil. The type of service in which the locomotive is used dictates the gear ratio employed. Numerically high ratios are commonly found on freight units, whereas numerically low ratios are typical of passenger engines.

Electricity is typically generated in large and relatively efficient generating stations, transmitted to the railway network and distributed to the trains. Some electric railways have their own dedicated generating stations and transmission lines but most purchase power from an electric utility. The railway usually provides its own distribution lines, switches and transformers.

Electric locomotives usually cost 20% less than diesel locomotives, their maintenance costs are 25–35% lower, and cost up to 50% less to run.[21]

Direct current

[edit]

The earliest systems were DC systems. The first electric passenger train was presented by Werner von Siemens at Berlin in 1879. The locomotive was driven by a 2.2 kW, series-wound motor, and the train, consisting of the locomotive and three cars, reached a speed of 13 km/h. During four months, the train carried 90,000 passengers on a 300-meter-long (980-foot) circular track. The electricity (150 V DC) was supplied through a third insulated rail between the tracks. A contact roller was used to collect the electricity. The world's first electric tram line opened in Lichterfelde near Berlin, Germany, in 1881. It was built by Werner von Siemens (see Gross-Lichterfelde Tramway and Berlin Straßenbahn). The Volk's Electric Railway opened in 1883 in Brighton, and is the oldest surviving electric railway. Also in 1883, Mödling and Hinterbrühl Tram opened near Vienna in Austria. It was the first in the world in regular service powered from an overhead line. Five years later, in the U.S. electric trolleys were pioneered in 1888 on the Richmond Union Passenger Railway, using equipment designed by Frank J. Sprague.[22]

The first electrically worked underground line was the City & South London Railway, prompted by a clause in its enabling act prohibiting use of steam power.[23] It opened in 1890, using electric locomotives built by Mather & Platt. Electricity quickly became the power supply of choice for subways, abetted by the Sprague's invention of multiple-unit train control in 1897.

The first use of electrification on a main line was on a four-mile stretch of the Baltimore Belt Line of the Baltimore & Ohio (B&O) in 1895 connecting the main portion of the B&O to the new line to New York through a series of tunnels around the edges of Baltimore's downtown. Three Bo+Bo units were initially used, at the south end of the electrified section; they coupled onto the locomotive and train and pulled it through the tunnels.[24]

DC was used on earlier systems. These systems were gradually replaced by AC. Today, almost all main-line railways use AC systems. DC systems are confined mostly to urban transit such as metro systems, light rail and trams, where power requirement is less.

Alternating current

[edit]

The first practical AC electric locomotive was designed by Charles Brown, then working for Oerlikon, Zürich. In 1891, Brown had demonstrated long-distance power transmission, using three-phase AC, between a hydro-electric plant at Lauffen am Neckar and Frankfurt am Main West, a distance of 280 km. Using experience he had gained while working for Jean Heilmann on steam–electric locomotive designs, Brown observed that three-phase motors had a higher power-to-weight ratio than DC motors and, because of the absence of a commutator, were simpler to manufacture and maintain.[a] However, they were much larger than the DC motors of the time and could not be mounted in underfloor bogies: they could only be carried within locomotive bodies.[26]

In 1894, Hungarian engineer Kálmán Kandó developed a new type 3-phase asynchronous electric drive motors and generators for electric locomotives. The new 3-phase asynchronous electric drive motors were more effective than the synchronous electric motors of earlier locomotive designs. Kandó's early 1894 designs were first applied in a short three-phase AC tramway in Evian-les-Bains (France), which was constructed between 1896 and 1898.[27][28][29][30][31] In 1918,[32] Kandó invented and developed the rotary phase converter, enabling electric locomotives to use three-phase motors whilst supplied via a single overhead wire, carrying the simple industrial frequency (50 Hz) single phase AC of the high voltage national networks.[33]

In 1896, Oerlikon installed the first commercial example of the system on the Lugano Tramway. Each 30-tonne locomotive had two 110 kW (150 hp) motors run by three-phase 750 V 40 Hz fed from double overhead lines. Three-phase motors run at constant speed and provide regenerative braking, and are well suited to steeply graded routes, and the first main-line three-phase locomotives were supplied by Brown (by then in partnership with Walter Boveri) in 1899 on the 40 km Burgdorf—Thun line, Switzerland. The first implementation of industrial frequency single-phase AC supply for locomotives came from Oerlikon in 1901, using the designs of Hans Behn-Eschenburg and Emil Huber-Stockar; installation on the Seebach-Wettingen line of the Swiss Federal Railways was completed in 1904. The 15 kV, 50 Hz 345 kW (460 hp), 48 tonne locomotives used transformers and rotary converters to power DC traction motors.[34]

Italian railways were the first in the world to introduce electric traction for the entire length of a main line rather than just a short stretch. The 106 km Valtellina line was opened on 4 September 1902, designed by Kandó and a team from the Ganz works.[35][33] The electrical system was three-phase at 3 kV 15 Hz. The voltage was significantly higher than used earlier and it required new designs for electric motors and switching devices.[36][37] The three-phase two-wire system was used on several railways in Northern Italy and became known as "the Italian system". Kandó was invited in 1905 to undertake the management of Società Italiana Westinghouse and led the development of several Italian electric locomotives.[36]

Battery–electric

[edit]

A battery–electric locomotive (or battery locomotive) is an electric locomotive powered by onboard batteries; a kind of battery electric vehicle.

Such locomotives are used where a conventional diesel or electric locomotive would be unsuitable. An example is maintenance trains on electrified lines when the electricity supply is turned off. Another use is in industrial facilities where a combustion-powered locomotive (i.e., steam- or diesel-powered) could cause a safety issue due to the risks of fire, explosion or fumes in a confined space. Battery locomotives are preferred for mines where gas could be ignited by trolley-powered units arcing at the collection shoes, or where electrical resistance could develop in the supply or return circuits, especially at rail joints, and allow dangerous current leakage into the ground.[38] Battery locomotives in over-the-road service can recharge while absorbing dynamic-braking energy.[39]

The first known electric locomotive was built in 1837 by chemist Robert Davidson of Aberdeen, and it was powered by galvanic cells (batteries). Davidson later built a larger locomotive named Galvani, exhibited at the Royal Scottish Society of Arts Exhibition in 1841. The seven-ton vehicle had two direct-drive reluctance motors, with fixed electromagnets acting on iron bars attached to a wooden cylinder on each axle, and simple commutators. It hauled a load of six tons at four miles per hour (6 kilometers per hour) for a distance of one and a half miles (2.4 kilometres). It was tested on the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway in September of the following year, but the limited power from batteries prevented its general use.[40][41][42]

Another example was at the Kennecott Copper Mine, Latouche, Alaska, where in 1917 the underground haulage ways were widened to enable working by two battery locomotives of 4+1⁄2 tons.[43] In 1928, Kennecott Copper ordered four 700-series electric locomotives with on-board batteries. These locomotives weighed 85 tons and operated on 750-volt overhead trolley wire with considerable further range whilst running on batteries.[44] The locomotives provided several decades of service using Nickel–iron battery (Edison) technology. The batteries were replaced with lead-acid batteries, and the locomotives were retired shortly afterward. All four locomotives were donated to museums, but one was scrapped. The others can be seen at the Boone and Scenic Valley Railroad, Iowa, and at the Western Railway Museum in Rio Vista, California. The Toronto Transit Commission previously operated a battery electric locomotive built by Nippon Sharyo in 1968 and retired in 2009.[45]

London Underground regularly operates battery–electric locomotives for general maintenance work.

Other types

[edit]Fireless

[edit]Atomic–electric

[edit]In the early 1950s, Lyle Borst of the University of Utah was given funding by various US railroad line and manufacturers to study the feasibility of an electric-drive locomotive, in which an onboard atomic reactor produced the steam to generate the electricity. At that time, atomic power was not fully understood; Borst believed the major stumbling block was the price of uranium. With the Borst atomic locomotive, the center section would have a 200-ton reactor chamber and steel walls 5 feet thick to prevent releases of radioactivity in case of accidents. He estimated a cost to manufacture atomic locomotives with 7000 h.p. engines at approximately $1,200,000 each.[46] Consequently, trains with onboard nuclear generators were generally deemed unfeasible due to prohibitive costs.

Fuel cell–electric

[edit]In 2002, the first 3.6 tonne, 17 kW hydrogen-(fuel-cell)–powered mining locomotive was demonstrated in Val-d'Or, Quebec. In 2007 the educational mini-hydrail in Kaohsiung, Taiwan went into service. The Railpower GG20B finally is another example of a fuel cell–electric locomotive.

Hybrid locomotives

[edit]

There are many different types of hybrid or dual-mode locomotives using two or more types of motive power. The most common hybrids are electro-diesel locomotives powered either from an electricity supply or else by an onboard diesel engine. These are used to provide continuous journeys along routes that are only partly electrified. Examples include the EMD FL9 and Bombardier ALP-45DP

Use

[edit]There are three main uses of locomotives in rail transport operations: hauling passenger trains, freight trains, and switching (UK English: shunting).

Freight locomotives are normally designed to deliver high starting tractive effort and high sustained power. This allows them to start and move long, heavy trains, but usually comes at the cost of relatively low maximum speeds. Passenger locomotives usually develop lower starting tractive effort but are able to operate at the high speeds required to maintain passenger schedules. Mixed-traffic locomotives (US English: general purpose or road switcher locomotives) meant for both passenger and freight trains do not develop as much starting tractive effort as a freight locomotive but are able to haul heavier trains than a passenger locomotive.[dubious – discuss]

Most steam locomotives have reciprocating engines, with pistons coupled to the driving wheels by means of connecting rods, with no intervening gearbox. This means the combination of starting tractive effort and maximum speed is greatly influenced by the diameter of the driving wheels. Steam locomotives intended for freight service generally have smaller diameter driving wheels than passenger locomotives.

In diesel-electric and electric locomotives the control system between the traction motors and axles adapts the power output to the rails for freight or passenger service. Passenger locomotives may include other features, such as head-end power (also referred to as hotel power or electric train supply) or a steam generator.

Some locomotives are designed specifically to work steep grade railways, and feature extensive additional braking mechanisms and sometimes rack and pinion. Steam locomotives built for steep rack and pinion railways frequently have the boiler tilted relative to the locomotive frame, so that the boiler remains roughly level on steep grades.

Locomotives are also used on some high-speed trains. Some of them are operated in push-pull formation with trailer control cars at another end of a train, which often have a cabin with the same design as a cabin of locomotive; examples of such trains with conventional locomotives are Railjet and Intercity 225.

Also many high-speed trains, including all TGV, many Talgo (250 / 350 / Avril / XXI), some Korea Train Express, ICE 1/ICE 2 and Intercity 125, use dedicated power cars, which do not have places for passengers and technically are special single-ended locomotives. The difference from conventional locomotives is that these power cars are integral part of a train and are not adapted for operation with any other types of passenger coaches. On the other hand, many high-speed trains such as the Shinkansen network never use locomotives. Instead of locomotive-like power-cars, they use electric multiple units (EMUs) or diesel multiple units (DMUs) – passenger cars that also have traction motors and power equipment. Using dedicated locomotive-like power cars allows for a high ride quality and less electrical equipment;[47] but EMUs have less axle weight, which reduces maintenance costs, and EMUs also have higher acceleration and higher seating capacity.[47] Also some trains, including TGV PSE, TGV TMST and TGV V150, use both non-passenger power cars and additional passenger motor cars.

Operational role

[edit]Locomotives occasionally work in a specific role, such as:

- Train engine is the technical name for a locomotive attached to the front of a railway train to haul that train. Alternatively, where facilities exist for push-pull operation, the train engine might be attached to the rear of the train;

- Pilot engine – a locomotive attached in front of the train engine, to enable double-heading;

- Banking engine – a locomotive temporarily assisting a train from the rear, due to a difficult start or a sharp incline gradient;

- Light engine – a locomotive operating without a train behind it, for relocation or operational reasons. Occasionally, a light engine is referred to as a train in and of itself.

- Station pilot – a locomotive used to shunt passenger trains at a railway station.

Wheel arrangement

[edit]The wheel arrangement of a locomotive describes how many wheels it has; common methods include the AAR wheel arrangement, UIC classification, and Whyte notation systems.

Remote control locomotives

[edit]In the second half of the twentieth century remote control locomotives started to enter service in switching operations, being remotely controlled by an operator outside of the locomotive cab. The main benefit is one operator can control the loading of grain, coal, gravel, etc. into the cars. In addition, the same operator can move the train as needed. Thus, the locomotive is loaded or unloaded in about a third of the time.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Air brake

- Articulated locomotive

- Autorail

- Bank engine

- Builder's plate

- Control car

- Duplex locomotive

- Electric multiple unit

- Headboard (train)

- Headstock (rolling stock)

- Kryšpín's system

- List of locomotive builders

- List of locomotives

- Locomotives in art

- Railway brakes

- Regenerative (dynamic) brakes

- Traction engine

- Rail vehicle resistance

- Train horn

- Vacuum brake

- World's largest locomotive

Notes

[edit]- ^ Heilmann evaluated both AC and DC electric transmission for his locomotives, but eventually settled on a design based on Thomas Edison's DC system.[25]

References

[edit]- ^ "Home". Railways Africa. 19 December 2019. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- ^ "Locomotive". (etymology). Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ^ "Most Important and highly Valuable Sea-Sale Colliery, Near Newcastle-on-Tyne, to be sold by auction, by Mr. Burrell". Leeds Mercury. 12 February 1814. p. 2.

- ^ Francis Trevithick (1872). Life of Richard Trevithick: With an Account of His Inventions, Volume 1. E.&F.N.Spon.

- ^ "Richard Trevithick's steam locomotive | Rhagor". Museumwales.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 15 April 2011. Retrieved 3 November 2009.

- ^ "Steam train anniversary begins". BBC News. 21 February 2004. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2009.

A south Wales town has begun months of celebrations to mark the 200th anniversary of the invention of the steam locomotive. Merthyr Tydfil was the location where, on 21 February 1804, Richard Trevithick took the world into the railway age when he set one of his high-pressure steam engines on a local iron master's tram rails

- ^ Payton, Philip (2004). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Young, Robert (2000) [1923]. Timothy Hackworth and the Locomotive (reprint ed.). Lewes, UK: The Book Guild.

- ^ P. Mathur; K. Mathur; S. Mathur (2014). Developments and Changes in Science Based Technologies. Partridge Publishing. p. 139.

- ^ Nock, Oswald (1977). Encyclopedia of Railroads. Galahad Books.

- ^ Hamilton Ellis (1968). The Pictorial Encyclopedia of Railways. Hamlyn Publishing Group. pp. 24–30.

- ^ Ellis, p. 355

- ^ "Diesel Locomotives. The Construction of and Performance Obtained from the Oil Engine". 1935. Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ Meiklejohn, Bernard (January 1906). "New Motors on Railroads: Electric and Gasoline Cars Replacing the Steam Locomotive". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XIII: 8437–54. Retrieved 10 July 2009.

- ^ "Diesel locomotives". mikes.railhistory.railfan.net. Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ Winkler, Thomas. "Daimler Motorwagen". Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- ^ Quine, Dan (November 2024). "The Railroad Equipment of the Yellow Aster Gold Mine Part 1: The Locomotives". Narrow Gauge and Short Line Gazette. Vol. 50, no. 5.

- ^ Lemp, Hermann. US Patent No. 1,154,785, filed 8 April 1914, and issued 28 September 1915. Accessed via Google Patent Search at: US Patent #1,154,785 Archived 22 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine on 8 February 2007.

- ^ Pinkepank 1973, pp. 139–141

- ^ "The first russian diesel locos". izmerov.narod.ru. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- ^ "Electrification of U.S. Railways: Pie in the Sky, or Realistic Goal? | Article | EESI". eesi.org. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ "Richmond Union Passenger Railway". IEEE History Center. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 18 January 2008.

- ^ Badsey-Ellis, Antony (2005). London's Lost Tube Schemes. Harrow: Capital Transport. p. 36. ISBN 1-85414-293-3.

- ^ B&O Power, Sagle, Lawrence, Alvin Stauffer

- ^ Duffy (2003), pp. 39–41.

- ^ Duffy (2003), p. 129.

- ^ Andrew L. Simon (1998). Made in Hungary: Hungarian Contributions to Universal Culture. Simon Publications LLC. p. 264. ISBN 978-0-9665734-2-8.

Evian-les-Bains kando.

- ^ Francis S. Wagner (1977). Hungarian Contributions to World Civilization. Alpha Publications. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-912404-04-2.

- ^ C.W. Kreidel (1904). Organ für die fortschritte des eisenbahnwesens in technischer beziehung. p. 315.

- ^ Elektrotechnische Zeitschrift: Beihefte, Volumes 11–23. VDE Verlag. 1904. p. 163.

- ^ L'Eclairage électrique, Volume 48. 1906. p. 554.

- ^ Duffy (2003), p. 137.

- ^ a b Hungarian Patent Office. "Kálmán Kandó (1869–1931)". mszh.hu. Archived from the original on 8 October 2010. Retrieved 10 August 2008.

- ^ Duffy (2003), p. 124.

- ^ Duffy (2003), p. 120–121.

- ^ a b "Kalman Kando". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- ^ "Kalman Kando". Archived from the original on 12 July 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2009.

- ^ Strakoš, Vladimír; et al. (1997). Mine Planning and Equipment Selection. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Balkema. p. 435. ISBN 90-5410-915-7.

- ^ Lustig, David (21 April 2023). "EMD Joule Battery Electric Locomotive arrives in Southern California". Trains. Kalmbach Media. Archived from the original on 28 April 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ Day, Lance; McNeil, Ian (1966). "Davidson, Robert". Biographical dictionary of the history of technology. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-06042-4.

- ^ Gordon, William (1910). "The Underground Electric". Our Home Railways. Vol. 2. London: Frederick Warne and Co. p. 156.

- ^ Renzo Pocaterra, Treni, De Agostini, 2003

- ^ Martin, George Curtis (1919). Mineral resources of Alaska. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. p. 144.

- ^ "List of Kennecott Copper locomotives". Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- ^ "A Rogue's Gallery: The TTC's Subway Work Car Fleet – Transit Toronto – Content". Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ "Atomic Locomotive Produces 7000 h.p." Archived 6 November 2023 at the Wayback Machine Popular Mechanics, April 1954, p. 86.

- ^ a b Hata, Hiroshi (1998). Wako, Kanji (ed.). "What Drives Electric Multiple Units?" (PDF). Japan Railway & Transport Review. Tokyo, Japan: East Japan Railway Culture Foundation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2022. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

Bibliography

[edit]- Churella, Albert J. (1998). From Steam To Diesel: Managerial Customs and Organizational Capabilities in the Twentieth-Century American Locomotive Industry. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02776-0.

- Duffy, Michael C. (2003). Electric Railways 1880–1990. IET. ISBN 978-0-85296-805-5.

- Ellis, Cuthbert Hamilton (12 December 1988). Pictorial Encyclopedia of Railways. Random House Value Publishing. ISBN 978-0-517-01305-2.

- Flowers, Andy (2020). International Passenger Locomotives: Since 1985. World Railways Series, Vol 1. Stamford, Lincs, UK: Key Publishing. ISBN 9781913295929. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- Pinkepank, Jerry A. (1973). The Second Diesel Spotter's Guide. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Kalmbach Publishing. ISBN 978-0-89024-026-7.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Locomotives at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Locomotives at Wikimedia Commons

- An engineer's guide from 1891 Archived 2 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Locomotive cutaways and historical locomotives of several countries ordered by dates

- Pickzone Locomotive Model[permanent dead link]

- International Steam Locomotives

- Turning a Locomotive into a Stationary Engine, Popular Science monthly, February 1919, page 72, Scanned by Google Books: Popular Science

Locomotive

View on GrokipediaTerminology and Overview

Etymology

The term "locomotive" originates from Medieval Latin locomotivus, a compound of loco ("from a place") and motivus ("causing motion" or "moving"), reflecting the concept of self-propelled movement from one location to another.[10] This etymological root entered English in the early 17th century as an adjective describing anything capable of locomotion, but its application to mechanical devices evolved significantly in the context of industrial innovation. By the 1650s, it connoted general mobility, such as animals or vehicles moving from place to place.[11] In the early 19th century, particularly amid the rapid development of steam technology in Britain, "locomotive" gained specificity as a descriptor for self-powered engines, distinguishing them from stationary steam engines fixed in factories or mines for pumping or milling.[10] The noun form "locomotive engine" first appeared around 1814 to denote machines with inherent mobility, marking a shift from immobile power sources like James Watt's atmospheric engines to portable ones suitable for transport.[10] This terminology became essential in British engineering discourse, where inventors like Richard Trevithick and George Stephenson applied it to experimental rail-hauling devices, emphasizing their ability to move independently along tracks.[12] By the 1820s and 1830s, the term had crossed the Atlantic and taken root in American rail contexts, similarly contrasting mobile rail engines with stationary industrial ones.[13] In the United States, early adopters like the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad used "locomotive" for prototypes such as the 1830 Tom Thumb, reinforcing its meaning as a self-propelled rail vehicle distinct from horse-drawn or fixed-engine systems.[13] A pivotal moment in standardizing the term occurred with George Stephenson's Rocket, unveiled in 1829, which not only won the Rainhill Trials but also exemplified the locomotive as a reliable, high-speed rail engine, influencing global nomenclature for such machines.[14]Definition and Basic Principles

A locomotive is a self-propelled rail vehicle designed primarily to provide motive power for hauling other rail equipment, such as freight cars or passenger coaches, without itself carrying significant freight or passengers.[15] This distinguishes it from railcars, which combine transport capacity with limited propulsion, or multiple units, where motive power is distributed across self-propelled passenger or freight vehicles forming a single operational trainset without a separate leading engine.[16] The basic operating principle of a locomotive centers on rail adhesion, the frictional interaction at the wheel-rail interface that enables the transmission of force from the locomotive's powered wheels to propel or brake the train. Adhesion arises from the contact patch where the steel wheel meets the steel rail, influenced by factors such as surface cleanliness, moisture, and contaminants, with typical dry coefficients ranging from 0.25 to 0.35 under normal conditions.[17] This friction limits the locomotive's ability to accelerate or maintain speed on grades, as excessive torque can cause wheel slip, reducing efficiency and risking loss of traction. Tractive effort, the pulling or pushing force generated at the wheel-rail interface, is fundamentally constrained by adhesion and quantified as the product of the adhesion coefficient and the vertical load on the driving wheels:where is tractive effort, is the coefficient of adhesion, and is the weight borne by the driving axles.[18] Locomotives are engineered to optimize this relationship by distributing weight over powered axles, often achieving utilized adhesion levels up to 25-30% of the adhesive weight to balance performance and stability.[19]