Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

China–United Kingdom relations

View on Wikipedia

| |

China |

United Kingdom |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Embassy of China, London | Embassy of the United Kingdom, Beijing |

| Envoy | |

| Ambassador Zheng Zeguang | Ambassador Caroline Wilson |

Chinese–United Kingdom relations (simplified Chinese: 中英关系; traditional Chinese: 中英關係; pinyin: Zhōng-Yīng guānxì), more commonly known as British–Chinese relations, Anglo-Chinese relations and Sino-British relations, are the interstate relations between China (with its various governments through history) and the United Kingdom. The People's Republic of China and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland established diplomatic relations on 17 June 1954.[1]

In the 19th century, the British Empire established several colonies in China, most prominently Hong Kong, which it gained after defeating the Qing dynasty in the First Opium War. Relations between the two nations have gone through ups and downs over the course of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. The UK and China were on opposing sides during the Cold War, and relations were strained over the issue of Hong Kong.[2][3] In 1984, both sides signed the Sino-British Joint Declaration, which eventually led to the handover of Hong Kong to China in 1997.

Following the conclusion of the Cold War and the handover of Hong Kong, a period known as the "Golden Era" of Sino-British relations began with multiple high-level state visits and bilateral trade and military agreements.[4][5] This roughly 20-year period came to an abrupt end during the 2019–2020 Hong Kong protests and the imposition of the 2020 Hong Kong national security law, which was viewed in the UK as a serious breach of the Sino-British Joint Declaration.[6][7] In the years following relations have deteriorated significantly over various issues including Chinese company Huawei's involvement in UK's 5G network development, espionage, and human rights abuses in Xinjiang.[8][9] However, despite this, China is the UK's fifth-largest trading partner as of 2025.[10]

Chronology

[edit]

England and the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644)

[edit]In the 1620s, English ships began arriving at Macau, a port city leased by China to Portugal. During this period, an English merchant vessel named The Unicorn sank near Macau. The Portuguese salvaged several cannons, specifically sakers, from the wreck and sold them to the Chinese around 1620. These cannons were then replicated by the Chinese as the Hongyipao, marking an early instance of military technology exchange.

On 27 June 1637, a fleet of four heavily armed English ships commanded by Captain John Weddell reached Macau in an effort to establish trade relations with China. This venture was not sanctioned by the East India Company but was instead organized by a private consortium led by Sir William Courten, with King Charles I personally investing £10,000. The Portuguese authorities in Macau, bound by their agreements with the Ming court, opposed the English expedition. This opposition, coupled with the English presence, quickly provoked the Ming authorities.

Later that summer, the English force captured one of the Bogue forts at the mouth of the Pearl River and engaged in several weeks of intermittent skirmishes and smuggling operations. The situation deteriorated further, leading the English to rely on Portuguese mediation for the release of three hostages. Eventually, the expedition withdrew from the Pearl River on 27 December 1637. The fate of the fleet afterward remained uncertain.[11][12][13]

Great Britain and the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911)

[edit]The relationship between Great Britain and the Qing Dynasty evolved over several centuries, shaped by diplomacy, trade, military conflict, and the broader dynamics of empire.

Early contact included the 1685 visit of Michael Shen Fu-Tsung, a Chinese Jesuit, to Britain, where he met King James II.[14] Trade officially began in 1699 when the East India Company was permitted to conduct business in Guangzhou (Canton), marking the start of sustained commercial relations.[15]

In 1784, the Lady Hughes Affair, where a British gunner's salute led to unintended deaths, heightened tensions. This foreshadowed the cultural and legal misunderstandings that would plague future interactions. High-level diplomatic efforts followed, such as the Macartney Embassy of 1793 and the Amherst Embassy of 1816, both of which failed to establish equal diplomatic footing with the Qing court.

By the 1820s and 1830s, British merchants had turned Lintin Island into a hub for the opium trade.[16][17] This illicit commerce contributed directly to the First Opium War (1839–42). Prior to the war, the East India Company's monopoly on Chinese trade was abolished (1833–35), prompting efforts by successive British governments to maintain peace. However, figures like Lord Napier took a more provocative stance, pushing for deeper market access, despite the Foreign Office under Lord Palmerston favoring a less confrontational approach [18]

The war culminated in a decisive British victory. British motivations were framed by Palmerston's biographer as a confrontation between a dynamic, modern trading nation and a stagnant autocracy.[19] However, critics such as the Chartists and young William Ewart Gladstone condemned the war as morally reprehensible, pointing to the devastation caused by opium addiction.[20][21][22]

A temporary peace was brokered with the Convention of Chuenpi in 1841, though it was never ratified. The conflict formally ended with the Treaty of Nanking in 1842, which ceded Hong Kong Island to Britain and opened five treaty ports to international trade.[23] The Treaty of the Bogue followed in 1843, granting Britain most-favoured-nation status and legal extraterritoriality.

Throughout the mid-19th century, British influence in China expanded. From 1845 to 1863, the British Concession in Shanghai was established, later becoming part of the Shanghai International Settlement. The Second Opium War (1856–60) further entrenched British power. Following military successes, including the sack of the Old Summer Palace in 1860, the Convention of Peking granted Britain control of the Kowloon Peninsula and led to the establishment of a British legation in Beijing by 1861.

British consulates soon appeared across Chinese territory, including in Wuhan, Kaohsiung, Taipei, Shanghai, and Xiamen. Meanwhile, domestic unrest occasionally erupted, such as the 1868 Yangzhou riot targeting Christian missionaries. Despite such challenges, skilled diplomats like Li Hongzhang (1823–1901) continued efforts to mediate Qing engagement with Western powers.

Technological integration followed. From 1870 to 1900, Britain developed and operated a telegraph network linking London to key Chinese ports.[24] Diplomatic ties were formalized further when China opened a legation in London in 1877, headed by Guo Songtao. Britain also advised on the Ili Crisis (1877–81), reflecting its growing influence in Qing foreign affairs.

The late 19th century saw geopolitical adjustments. After Britain's annexation of Burma in 1886, the Burma Convention acknowledged British occupation while maintaining China's symbolic suzerainty through continued tribute payments.[25][26] Conflict between Britain and Tibetan forces in Sikkim led to the Treaty of Calcutta (1890), by which China recognized British control over northern Sikkim. A further agreement in 1890 fixed the border between Sikkim and Tibet.[27]

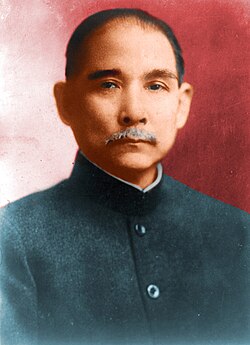

Britain's global influence was also felt in individual incidents, such as the 1896 detention of revolutionary Sun Yat-sen in the Chinese Legation in London. British public pressure led to his release, illustrating the political significance of diaspora activism.

The 1898 Convention for the Extension of Hong Kong leased the New Territories to Britain for 99 years, and that same year, Britain secured a lease on Weihai Harbour in Shandong. An odd footnote occurred in December 1898, when the arrival of four young English women in Shanghai sparked public commentary and minor diplomatic tensions.[28][29][30][31]

The turn of the century brought renewed conflict during the Boxer Rebellion (1900–1901), a violent anti-foreigner uprising suppressed by an allied force led by Britain and Japan. The resulting Boxer Protocol imposed heavy penalties on the Qing regime. Britain continued to assert influence over Tibetan affairs, most notably through the 1906 Anglo-Chinese Treaty on Tibet, which Britain interpreted as limiting China to nominal suzerainty.

By 1909, British consulates in Taiwan were closed following Japan's assertion of sovereignty, marking a shift in East Asian power dynamics. This period closed with Britain entrenched as a dominant force in China's foreign relations, trade, and territorial concessions.

Britain and the Republic of China (1912–1950)

[edit]

Between 1912 and 1950, relations between Britain and the Republic of China (ROC) evolved significantly, marked by shifting alliances, conflict, diplomacy, and eventual disengagement.

Although Sun Yat-sen, who later became the founding father of the Republic of China, was rescued by British diplomats from Qing agents in 1896, early British involvement with Chinese political affairs was often shaped by colonial interests and imperial competition.

During World War I, in 1916, Britain recruited tens of thousands of Chinese labourers into the Chinese Labour Corps to support the war effort on the Western Front. On 14 August 1917, China officially joined the Allies, aligning itself with Britain in opposition to the Central Powers.

However, tensions emerged after the war. On 4 May 1919, the May Fourth Movement erupted in response to the Chinese government's failure to secure benefits from the postwar settlement. Britain had supported its treaty ally Japan over the contentious Shandong Problem, contributing to a broader Chinese disillusionment with Western democracies and a turn toward the Soviet Union for ideological and political inspiration.

At the Washington Naval Conference (November 1921–February 1922), Britain joined other powers in signing the Nine-Power Treaty, which recognised Chinese sovereignty. As part of the agreements, Japan returned control of Shandong province to China, resolving the Shandong Problem[32]

In the years that followed (1922–1929), Britain, the United States, and Japan backed various Chinese warlords, often working against the revolutionary Nationalist government in Guangzhou (Canton). Britain and the U.S. supported Chen Jiongming's rebellion against the Nationalists, exacerbating tensions. These foreign interventions, and domestic instability, culminated in the Northern Expedition (1926–1927), which eventually brought most of China under Chiang Kai-shek’s control.[33]

On 30 May 1925, the killing of nine Chinese protesters by the British-led Shanghai Municipal Police triggered the May 30 Movement, a nationwide anti-British campaign. This incident highlighted growing Chinese resentment toward foreign imperialism.

Further unrest in Hankou (Wuhan) led to the Chen–O’Malley Agreement of 19 February 1927, under which Britain agreed to hand over its concession in Hankou to the Chinese authorities.

Between 1929 and 1931, China pursued full sovereignty by regaining control over its tariff rates, previously fixed at just 5% by foreign powers, and seeking to abolish extraterritorial privileges enjoyed by Britain and other nations in treaty ports like Shanghai. These goals were largely achieved by 1931.[34]

In 1930, Britain returned Weihai Harbour to Chinese control. Further diplomatic progress was marked by Britain's decision, on 17 May 1935, to elevate its Legation in Beijing to an Embassy; addressing longstanding Chinese complaints about the perceived disrespect of a lower diplomatic rank.[35]

Following the Chinese capital's move to Nanjing, the British Embassy also relocated there in 1936–1937. As Japan launched its invasion of China in 1937, British public opinion and government sympathy tilted in China's favour. Nonetheless, with Britain focused on defending its own empire, especially Singapore, direct support was limited. Britain did assist by training Chinese troops in India and providing airbases for American supply missions to China[36]

During World War II (1941–1945), Britain and China became official allies against Japan. Chinese troops trained in India fought alongside British forces in the Burma campaign. Close coordination continued throughout the war, symbolised by the wartime cooperation between Chiang Kai-shek and Winston Churchill. However, postwar diplomacy shifted dramatically. On 6 January 1950, His Majesty's Government withdrew its recognition from the Republic of China, now based in Taiwan, following the Communist victory on the mainland. Britain closed its Embassy in Nanjing but maintained a Consulate in Tamsui, nominally for liaison with the Taiwan Provincial Government.

Between the UK and the People's Republic of China (1949–present)

[edit]

Between 1949 and the present, the relationship between the United Kingdom and the People's Republic of China (PRC) has evolved through a series of pragmatic decisions, diplomatic tensions, and significant historical moments.

During World War II, Britain was aligned with the anti-Communist Nationalist Chinese government. Following the war, British priorities centred on preserving stability in China to protect over £300 million in investments; far exceeding U.S. interests in the region. While Britain agreed not to interfere in Chinese affairs as per the 1945 Moscow Agreement, it remained sympathetic to the Nationalists, who appeared dominant in the Chinese Civil War until 1947.[37]

However, by August 1948, the tide had turned. With the Communists gaining ground, the British government began to prepare for their potential victory. It maintained consular operations in Communist-controlled areas and declined Nationalist appeals for British assistance in defending Shanghai. By December, Whitehall concluded that although nationalisation of British assets was likely, long-term economic engagement with a stable, industrialising China could prove beneficial. Safeguarding Hong Kong remained paramount, and the UK bolstered its garrison there in 1949, even as the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) offered reassurances on non-interference.

On 1 October 1949, the PRC government announced its willingness to establish diplomatic relations with any nation that severed ties with the Nationalists. After consultation with Commonwealth and European partners, Britain formally recognised the PRC in January 1950.[37]

On 20 April 1949, the People's Liberation Army attacked HMS Amethyst (F116) travelling to the British Embassy in Nanjing in the Amethyst incident. The CCP do not recognise the unequal treaties and protest the ship's right to sail on the Yangtze.[38][39]

Following recognition on 6 January 1950, the UK posted a chargé d'affaires in Beijing, expecting swift ambassadorial exchange. However, the PRC insisted on conditions concerning the Chinese seat at the United Nations and the handling of Nationalist-held foreign assets.

Meanwhile, British commercial interests began adapting to the new reality. In 1950, a consortium of British businesses formed the Group of 48 (now the China-Britain Business Council) to facilitate trade with the PRC.[35][40] This effort was further institutionalised with the formation of the Sino-British Trade Committee in 1954.

Military interactions between the two countries also occurred indirectly during the Korean War. British Commonwealth Forces engaged in several key battles against Chinese forces, including the defence of Hill 282 at Pakchon in 1950, clashes at the Imjin River in 1951, and successful engagements at Kapyong, Maryang San, and Yong Dong in 1953.

In a diplomatic breakthrough, a British Labour Party delegation led by Clement Attlee visited China in 1954 at the invitation of PRC Premier Zhou Enlai.[41] Attlee became the first high-ranking western politician to meet CCP Chairman Mao Zedong.[42] That same year, the Geneva Conference paved the way for mutual diplomatic presence: the PRC agreed to post a chargé d’affaires in London, reopen the British office in Shanghai, and issue exit visas for British nationals detained since 1951.[43] In 1961, the UK began to vote in the General Assembly for PRC membership of the United Nations. It had abstained on votes since 1950.[44]

During the Suez Crisis in 1956, China condemned the UK and France and made strong statements in support of Egypt.[45]: xxxvii

Bilateral relations soured during China's Cultural Revolution. In June 1967, Red Guards attacked British diplomats in Beijing, and PRC authorities offered no condemnation.[46]

Riots broke out in Hong Kong in June 1967. The commander of the Guangzhou Military Region, Huang Yongsheng, secretly suggested invading Hong Kong, but his plan was vetoed by PRC Premier Zhou Enlai.[47] That same month, unrest spread to Hong Kong, with PRC military commanders even contemplating an invasion; though Zhou Enlai vetoed the idea.[48] In July, Chinese troops fatally shot five Hong Kong police officers.

Hostilities escalated on 23 August 1967, when Red Guards stormed the British Legation in Beijing, injuring chargé d'affaires Sir Donald Hopson and others, including Sir Percy Cradock. The attack was a reprisal for British arrests of CCP agents in Hong Kong. Days later, on 29 August, armed Chinese diplomats clashed with British police in London.[49]

A thaw began in March 1972, when the PRC extended full diplomatic recognition to the UK, allowing for ambassadorial exchange. The UK, in turn, acknowledged the PRC's position on Taiwan.[50]

In 1982, during negotiations over Hong Kong's future, Chinese paramount leader Deng Xiaoping bluntly told Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher that China could simply take the territory by force; later confirmed as a genuine consideration.[47] These talks culminated in the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration.

Queen Elizabeth II made a historic state visit to China in October 1986, becoming the first reigning British monarch to do so.[51]

The most symbolic moment in the bilateral relationship came on 30 June–1 July 1997, when Hong Kong was officially handed over from the United Kingdom to the People's Republic of China, marking the end of more than 150 years of British rule.

2000s

[edit]In the 2000s, significant developments shaped China–UK relations. On 29 October 2008, the United Kingdom formally recognised Tibet as an integral part of the People's Republic of China, marking a shift from its earlier position, which had only acknowledged Chinese suzerainty over the region.[52]

In November 2005, China and the UK signed a series of bilateral agreements, including announcing an initiative to jointly create "the world's first carbon neutral eco-city."[53]: 161 The contemplated development, Dongtan Eco-City, was not ultimately completed.[54]: 163–164 It later influenced other approaches to Chinese eco-cities.[54]: 163–164

Further strengthening bilateral ties, General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party and President Xi Jinping and Peng Liyuan paid a state visit to the UK from 20 to 23 October 2015. Their itinerary included stops in London and Manchester, with engagements involving Queen Elizabeth II and then-Prime Minister David Cameron. The visit culminated in the signing of trade deals valued at over £30 billion, symbolising deepening economic cooperation between the two nations.[55][56][57]

This spirit of engagement continued under Prime Minister Theresa May, who travelled to China in February 2018 for a three-day trade mission. During the visit, she met with Xi Jinping, affirming the continuation of what was described as the "Golden Era" in UK–China relations.[58]

Both countries share common membership of the G20, the UNSC P5, the United Nations, and the World Trade Organization. Bilaterally the two countries have a Double Taxation Agreement,[59] an Investment Agreement,[60] and the Sino-British Joint Declaration.

2020s

[edit]Throughout the 2020s, relations between China and the United Kingdom became increasingly strained, marked by disputes over human rights, national security, and espionage.

Tensions rose sharply in 2020 when the UK openly opposed China's imposition of the Hong Kong national security law. Lord Patten, the last British governor of Hong Kong, described the move as a breach of the "one country, two systems" framework and a violation of the Sino-British Joint Declaration.[61][62] Prime Minister Boris Johnson echoed this sentiment in Parliament, calling the law a "clear and serious breach" of the joint declaration. In response, the UK government announced a pathway to full British citizenship for around three million Hong Kong residents holding British National (Overseas) status.[63] That same year, the UK suspended its extradition treaty with China, citing concerns over the treatment of the Uyghur minority in Xinjiang.[64]

Also in 2020, citing security concerns, the UK government banned the use of Huawei's equipment in its 5G infrastructure.[65] The following year, the UK implemented a visa scheme for Hongkongers affected by the national security law, resulting in over 200,000 Hong Kong residents relocating to Britain.[66]

In April 2021, a cross-party group of MPs, led by Sir Iain Duncan Smith, passed a parliamentary motion declaring China's mass detention of Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang as genocide. This made the UK the fourth country globally to make such a declaration. In retaliation, China's embassy in London condemned the accusation as “the most preposterous lie of the century” and accused the UK of interfering in its internal affairs.[67]

UK-China relations were further tested in October 2022, when Chinese consulate officials in Manchester allegedly dragged a pro-democracy protester onto consulate grounds and assaulted him.[68] Six Chinese diplomats, including the consul-general, were subsequently recalled by Beijing.[69]

After becoming Prime Minister in July 2024, Keir Starmer signalled a tougher stance toward China, particularly regarding human rights abuses and China's support for Russia during its invasion of Ukraine.[70] However, diplomatic efforts to restore dialogue continued. In November 2024, Starmer met Chinese leader Xi Jinping at the G20 summit in an attempt to reset relations, balancing economic cooperation with national security concerns. The meeting was marred by an incident in which British journalists were forcibly removed by Chinese officials as Starmer raised human rights issues.[71][72]

In January 2025, UK Chancellor Rachel Reeves visited China in an effort to stabilise economic ties and normalise relations.[73] Yet friction persisted. In April 2025, the UK government introduced emergency legislation to prevent the closure of British Steel’s Scunthorpe plant by its Chinese owner, Jingye Group, citing national security reasons.[74][75] In a rare Saturday sitting, Parliament passed the law allowing the government to take control of the site, with Prime Minister Starmer framing the move as essential for national and economic security.[76][77] In May 2025, the National Health Service launched an investigation into breaches of two NHS hospitals targeted by Chinese state-linked hackers.[78] In September 2025, the Eastern Theater Command of the PLA accused Britain of "trouble-making and provocation" when it and the U.S. jointly sailed warships through the Taiwan Strait.[79]

In October 2025 the Director of Public Prosecutions controversially dropped charges under the Official Secrets Act 1911 against Christopher Cash and Christopher Berry. Cash had been a Parliamentary researcher for Alicia Kearns MP. He had also been director of the Conservative MP's China Research Group.[80]

In November 2025, it was reported that Sheffield Hallam University faced pressure from the Chinese government to halt research by Professor Laura Murphy on alleged forced labour of Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang. Threats to staff and restrictions on the university’s websites in China aimed to protect access to Chinese students. After legal action and scrutiny, the university lifted the ban on the research in October 2025 and issued an apology, while UK authorities condemned foreign interference in academic freedom.[81]

Diplomacy

[edit]In 1954, UK Foreign Minister Anthony Eden and PRC Premier Zhou Enlai reached an agreement to exchange charges d'affaires.[82]: 93 As a result of the Korean War and other disagreements, the two countries did not exchange ambassadors until 1972.[82]: 93

|

|

Security concerns

[edit]British counter-terrorism authorities have reported a rise in hostile state activity linked to China within the United Kingdom, with operations allegedly involving threats to life such as planned attacks and covert actions. In July 2025, Dominic Murphy, head of London's Counter Terrorism Command, stated that the breadth, complexity, and volume of hostile operations from China among other countries had grown at a rate that neither British authorities, their international partners, nor the wider intelligence community had predicted. Officials also highlighted the increasing use of criminal proxies and vulnerable individuals, including minors, in carrying out these activities. Specific details regarding China's involvement were not disclosed.[83]

In July 2025, the UK Joint Committee on Human Rights labelled the China a "flagrant" perpetrator of transnational repression and presented a series of recommended responses to the UK government.[84]

Espionage

[edit]Academic freedom

[edit]Chinese intelligence agencies have threatened academic freedom at British universities. Sheffield Hallam University was threatened and pressured to stop the publication of research on Uyghur forced labor by Laura Murphy.[90][91][92]

Academics in British universities teaching on Chinese topics have been warned by the Chinese government to support the Chinese Communist Party or be refused entry to the country. Professors who disregarded the warnings to speak more positively about the CCP have had their visas cancelled which prevents them from doing fieldwork in China. Academics are warned to avoid the The Three Ts.[93] In March 2021, British Uyghur expert Joanne Smith Finley was sanctioned by China after she referred to the situation in Xinjiang as a genocide in comments given to the Associated Press.[94][95]

Transport

[edit]Air transport

[edit]All three major Chinese airlines, Air China, China Eastern & China Southern fly between the UK and China, principally between London-Heathrow and the three major air hubs of Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. China Southern also flies between Heathrow and Wuhan. Among China's other airlines; Hainan Airlines flies between Manchester and Beijing, Beijing Capital Airlines offers Heathrow to Qingdao, while Tianjin Airlines offers flights between Tianjin, Chongqing and Xi'an to London-Gatwick. Hong Kong's flag carrier Cathay Pacific also flies between Hong Kong to Heathrow, Gatwick and Manchester. The British flag carrier British Airways flies to just three destinations in China; Beijing, Shanghai and Hong Kong, and in the past Chengdu. Rival Virgin Atlantic flies between Heathrow to Shanghai and Hong Kong. British Airways has mentioned that it is interested in leasing China's new Comac C919 in its pool of aircraft of Boeing and Airbus.[96]

Rail transport

[edit]In January 2017, China Railways and DB Cargo launched the Yiwu-London Railway Line connecting the city of Yiwu and the London borough of Barking, and creating the longest railway freight line in the world. Hong Kong's MTR runs the London's TfL Rail service and has a 30% stake in South Western Railway. In 2017, train manufacturer CRRC won a contract to build 71 engineering wagons for London Underground. This is the first time a Chinese manufacturer has won a railway contract.[97]

Press

[edit]The weekly-published Europe edition of China Daily is available in a few newsagents in the UK, and on occasions a condensed version called China Watch is published in the Daily Telegraph.[98] The monthly NewsChina,[99] the North American English-language edition of China Newsweek (中国新闻周刊) is available in a few branches of WHSmith. Due to local censorship, British newspapers and magazines are not widely available in mainland China, however the Economist and Financial Times are available in Hong Kong.[citation needed]

British in China

[edit]Statesmen

[edit]- Sir Robert Hart was a Scots-Irish statesman who served the Chinese Imperial Government as Inspector General of Maritime Customs from 1863 to 1907.

- George Ernest Morrison resident correspondent of The Times, London, at Peking in 1897, and political adviser to the President of China from 1912 to 1920.

Diplomats

[edit]- Sir Thomas Wade – first professor of Chinese at Cambridge University

- Herbert Giles – second professor of Chinese at Cambridge University

- Harry Parkes

- Sir Claude MacDonald

- Sir Ernest Satow served as Minister in China, 1900–06.

- John Newell Jordan[100] followed Satow

- Sir Christopher Hum

- Augustus Raymond Margary

Merchants

[edit]Military

[edit]Missionaries

[edit]Academics

[edit]- Frederick W. Baller

- James Legge (first professor of Chinese at the University of Oxford)

- Joseph Needham

- Jonathan Spence

Chinese statesmen

[edit]Cultural relations

[edit]Sports

[edit]Table tennis, originating from the United Kingdom, became one of the most iconic sports in China in the 20th century.[101]

Public opinion

[edit]A survey published in 2025 by the Pew Research Center found that 56% of British people had an unfavorable view of China, while 39% had a favorable view. It also found that 56% of the people in the 18-35 age group had positive opinions of China.[102]

See also

[edit]- British Hong Kong (1841–1997)

- Foreign relations of the United Kingdom

- History of foreign relations of China

- China Policy Institute

- Foreign relations of China

- British Chinese (Chinese people in the UK)

- Sustainable Agriculture Innovation Network (between the UK and China)

References

[edit]- ^ "Overview on China-UK Relations". Embassy of the People's Republic of China in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. 10 April 2010. Archived from the original on 5 April 2024. Retrieved 5 April 2024.

- ^ Ives, Mike; Chen, Elsie (2019-09-16). "In 1967, Hong Kong's Protesters Were Communist Sympathizers". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2022-09-04. Retrieved 2022-09-04.

- ^ Griffiths, James (2017-06-18). "The secret negotiations that sealed Hong Kong's future". CNN. Archived from the original on 2022-09-04. Retrieved 2022-09-04.

- ^ "UK-China relations: from 'golden era' to the deep freeze". Financial Times. 2020-07-14. Archived from the original on 2022-09-04. Retrieved 2022-09-04.

- ^ Rao, Presented by Rachel Humphreys with Tania Branigan; produced by Mythili; Maynard, Axel Kacoutié; executive producers Phil; Jackson, Nicole (2020-07-14). "Is the UK's 'golden era' of relations with China now over? – podcast". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2022-09-04. Retrieved 2022-09-04.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Foreign Secretary declares breach of Sino-British Joint Declaration". GOV.UK. Archived from the original on 2023-06-14. Retrieved 2022-09-04.

- ^ "Hong Kong: UK accuses China of breaching joint declaration". The Guardian. 2021-03-13. Archived from the original on 2022-06-08. Retrieved 2022-09-04.

- ^ "Britain bans new Huawei 5G kit installation from September 2021". Reuters. 2020-11-30. Archived from the original on 2022-09-04. Retrieved 2022-09-04.

- ^ "Spies, trade and tech: China's relationship with Britain". The Economist. May 16, 2024. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2024-12-14.

- ^ "Trade and investment core statistics book". GOV.UK. Retrieved 2024-12-14.

- ^ Mundy, William Walter (1875). Canton and the Bogue: The Narrative of an Eventful Six Months in China. London: Samuel Tinsley. pp. 51.. The full text of this book is available.

- ^ Dodge, Ernest Stanley (1976). Islands and Empires: Western impact on the Pacific and East Asia (vol.VII). University of Minnesota Press. pp. 261–262. ISBN 978-0-8166-0788-4. Dodge says the fleet was dispersed off Sumatra, and Wendell was lost with all hands.

- ^ J.H.Clapham (1927). "Review of The Chronicles of the East India Company Trading to China, 1635-1834 by Hosea Ballou Morse". The English Historical Review. 42 (166). Oxford University Press: 289–292. doi:10.1093/ehr/XLII.CLXVI.289. JSTOR 551695. Clapham summarizes Morse as saying that Wendell returned home with a few goods.

- ^ "BBC - Radio 4 - Chinese in Britain". BBC. Archived from the original on 2008-12-07. Retrieved 2008-05-03.

- ^ "East India Company".

- ^ "Shameen: A Colonial Heritage" Archived 2008-12-29 at the Wayback Machine, By Dr Howard M. Scott

- ^ "China in Maps – A Library Special Collection". Archived from the original on December 17, 2008.

- ^ Glenn Melancon, "Peaceful intentions: the first British trade commission in China, 1833–5." Historical Research 73.180 (2000): 33-47.

- ^ Jasper Ridley, Lord Palmerston (1970) p. 249.

- ^ Ridley, 254-256.

- ^ May Caroline Chan, “Canton, 1857” Victorian Review (2010), 36#1 pp 31-35.

- ^ Glenn Melancon, Britain's China Policy and the Opium Crisis: Balancing Drugs, Violence and National Honour, 1833–1840 (2003)

- ^ Koon, Yeewan (2012). "The Face of Diplomacy in 19th-Century China: Qiying's Portrait Gifts". In Johnson, Kendall (ed.). Narratives of Free Trade: The Commercial Cultures of Early US-China Relations. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 131–148. Archived from the original on 2024-02-21. Retrieved 2024-04-23.

- ^ Ariane Knuesel, "British diplomacy and the telegraph in nineteenth-century China." Diplomacy and Statecraft 18.3 (2007): 517-537.

- ^ Alfred Stead (1901). China and her mysteries. London: Hood, Douglas, & Howard. p. 100.

- ^ Rockhill, William Woodville (1905). China's intercourse with Korea from the XVth century to 1895. London: Luzac & Co. p. 5.

- ^ "Convention Between Great Britain and China relating to Sikkim & Tibet". Tibet Justice Center. Archived from the original on 2006-09-09. Retrieved 2024-04-23.

- ^ Alicia E. Neva Little (10 June 2010). Intimate China: The Chinese as I Have Seen Them. Cambridge University Press. pp. 210–. ISBN 978-1-108-01427-4.

- ^ Mrs. Archibald Little (1899). Intimate China: The Chinese as I Have Seen Them. Hutchinson & Company. pp. 210–. ISBN 9780461098969. Archived from the original on 2024-04-23. Retrieved 2016-05-06.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ [1]

- ^ Little, Archibald (June 3, 1899). "Intimate China. The Chinese as I have seen them". London : Hutchinson & co. – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Office of the Historian - Milestones - 1921-1936 - the Washington Naval Conference". Archived from the original on 2013-10-22. Retrieved 2020-12-27.

- ^ Erik Goldstein, and John Maurer, The Washington Conference, 1921–22: Naval Rivalry, East Asian Stability and the Road to Pearl Harbor (2012).

- ^ L. Ethan Ellis, Republican foreign policy, 1921-1933 (Rutgers University Press, 1968), pp 311–321. online

- ^ a b "Britain Recognizes Chinese Communists: Note delivered in Peking". The Times. London. 7 January 1950. p. 6. ISSN 0140-0460.

- ^ J. K. Perry, "Powerless and Frustrated: Britain's Relationship With China During the Opening Years of the Second Sino-Japanese War, 1937–1939," Diplomacy and Statecraft, (Sept 2011) 22#3 pp 408–430,

- ^ a b Wolf, David C. (1983). "'To Secure a Convenience': Britain Recognizes China – 1950". Journal of Contemporary History. 18 (2): 299–326. doi:10.1177/002200948301800207. JSTOR 260389. S2CID 162218504.

- ^ Murfett, Malcolm H. (May 1991). "A Pyrrhic Victory: HMS Amethyst and the Damage to Anglo-Chinese Relations in 1949". War & Society. 9 (1): 121–140. doi:10.1179/072924791791202396. ISSN 0729-2473.

- ^ Murfett, Malcolm H. (2014-07-15). Hostage on the Yangtze: Britain, China, and the Amethyst Crisis of 1949. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-61251-321-8.

- ^ "British Envoy for Peking". The Times. London. 2 February 1950. p. 4. ISSN 0140-0460.

- ^ Mishra, Pankaj (December 20, 2010). "Staying Power: Mao and the Maoists". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on August 28, 2012. Retrieved September 21, 2011.

- ^ "Letter from Mao Zedong to Clement Attlee sells for £605,000". The Guardian. 2015-12-15. Archived from the original on 2020-07-28. Retrieved 2020-01-05.

- ^ "Backgrounder: China and the United Kingdom". Xinhua. 2003. Archived from the original on 2012-10-23. Retrieved 2008-12-10. "Chinese Envoy for London: A chargé d'affaires". The Times. London. 18 June 1955. p. 6. ISSN 0140-0460.

- ^ David C. Wolf, "'To Secure a Convenience': Britain Recognizes China-1950." Journal of Contemporary History (1983): 299–326.

- ^ Har-El, Shai (2024). China and the Palestinian Organizations: 1964–1971. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3-031-57827-4.

- ^ Harold Munthe-Kaas; Pat Healy (23 August 1967). "Britain's Tough Diplomatist in Peking". The Times. London. p. 6. ISSN 0140-0460.

- ^ a b "Revealed: the Hong Kong invasion plan", Michael Sheridan, Sunday Times, June 24, 2007

- ^ "Red Guard Attack as Ultimatum Expires". The Times. London. 23 August 1967. p. 1. ISSN 0140-0460.

- ^ Peter Hopkirk (30 August 1967). "Dustbin Lids Used as Shields". The Times. London. p. 1. ISSN 0140-0460.

- ^ "Backgrounder: China and the United Kingdom". Xinhua. 2003. Archived from the original on 2012-10-23. Retrieved 2008-12-10. "Ambassador to China after 22-year interval". The Times. London. 14 March 1972. p. 1. ISSN 0140-0460.

- ^ "Queen to Visit China". The New York Times. 11 September 1986. Archived from the original on 16 March 2018. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ^ Foreign and Commonwealth Office Written Ministerial Statement on Tibet Archived December 2, 2008, at the Wayback Machine 29 October 2008. Retrieved on 10 December 2008.

- ^ Lin, Zhongjie (2025). Constructing Utopias: China's New Town Movement in the 21st Century. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-779330-5.

- ^ a b Wu, Fulong; Zhang, Fangzhu (2025). Governing Urban Development in China: Critical Urban Studies. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-003-35517-5.

- ^ "Hong Kong billionaire puts China UK investments in shade". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 2023-10-30. Retrieved 2024-04-23.

- ^ Elgot, Jessica (20 October 2015). "Xi Jinping visit: Queen and Chinese president head to Buckingham Palace – live". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 December 2023. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Todd (20 October 2015). "Five places that Chinese President Xi Jinping should visit during his trip to Manchester with David Cameron". Manchester Evening News. Archived from the original on 20 October 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ Xiaoming, Liu (2018). "The UK-China 'Golden Era' can bear new fruit". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 2018-01-31. Retrieved 2018-02-01.

- ^ HM Revenue and Customs (17 December 2013). "China: tax treaties". GOV.UK. Archived from the original on 21 February 2025. Retrieved 21 March 2025.

- ^ "China - United Kingdom BIT (1986)". UN Trade and Development. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2025.

- ^ Lawler, Dave (2 July 2020). "The 53 countries supporting China's crackdown on Hong Kong". Axios. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ "Hong Kong: UK says new security law is 'deeply troubling'". BBC News. 30 June 2020. Archived from the original on 1 July 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ James, William (1 July 2020). "UK says China's security law is serious violation of Hong Kong treaty". Reuters. Archived from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ "U.K. suspends extradition treaty with Hong Kong amid public outrage over human rights in China". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 20 July 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ "Huawei 5G kit must be removed from UK by 2027". BBC News. 14 July 2020. Archived from the original on 11 August 2020. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ "Safe and Legal (Humanitarian) routes to the UK". Home Office. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ "Uyghurs: MPs state genocide is taking place in China". BBC News. 2021-04-23. Archived from the original on 2021-04-23. Retrieved 2021-04-23.

- ^ "I was dragged into China consulate, protester Bob Chan says". BBC News. 20 October 2022. Archived from the original on 1 November 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- ^ "China diplomats leave UK over Manchester protester attack". BBC. 14 December 2022. Archived from the original on 14 December 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ "Starmer vows to be 'robust' with China". The Telegraph. 10 July 2024.

- ^ "UK PM Starmer seeks 'pragmatic' Chinese ties in meeting with Xi". Reuters. 17 November 2024. Retrieved 19 November 2024.

- ^ "UK journalists forcibly removed from Xi-Starmer G20 meeting during rights debate". First Post. 18 November 2024.

- ^ "Rachel Reeves heads to China to build bridges, but a new golden era of relations is impossible". 9 January 2025. Archived from the original on 9 January 2025. Retrieved 9 January 2025.

- ^ "British government takes over running of UK's last major steel plant from Chinese owner Jingye". CNN. 2025-04-12. Retrieved 2025-04-13.

- ^ Landler, Mark (2025-04-15). "A Crisis at a British Steel Mill Has Cast a Shadow Over U.K.-China Relations". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2025-04-15.

- ^ "Government aims to take control of British Steel". www.surinametimes.com. Retrieved 2025-04-14.

- ^ "UK will set 'high trust bar' for future Chinese investment after British Steel rescue, minister says". AP News. 2025-04-13. Retrieved 2025-04-17.

- ^ Field, Matthew (2025-05-29). "Chinese state accused of hacking NHS hospitals". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 2025-05-30.

- ^ Lendon, Brad (2025-09-16). "Exercises show Washington keeping alliances strong as Pacific adversaries bring new threats". CNN. Retrieved 2025-09-17.

- ^ https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/crime/china-spying-chris-berry-chris-cash-parliament-researcher-b2532634.html

- ^ tibetanreview (2025-11-03). "Pressuring UK university ultimately fails to stop research on rights abuses in China". Tibetan Review. Retrieved 2025-11-04.

- ^ a b Crean, Jeffrey (2024). The Fear of Chinese Power: an International History. New Approaches to International History series. London, UK: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-350-23394-2.

- ^ Holden, Michael (2025-07-15). "Russia, Iran and China intensifying life-threatening operations in UK, police say". Reuters. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ Alecci, Scilla (2025-08-01). "Parliamentary committee labels China 'flagrant' perpetrator of transnational repression on UK soil". International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. Retrieved 2025-08-02.

- ^ Boycott-Owen, Mason (2025-10-16). "MI5 boss: Threats from states like China on a par with terrorists". Politico Europe. Retrieved 2025-10-19.

- ^ Dawson, Bethany (2025-10-16). "China conducted 'large scale espionage operations' against UK, top official warned in collapsed spy case". Politico Europe. Archived from the original on 2025-10-16. Retrieved 2025-10-19.

- ^ Smith, Michael (2009-03-29). "Spy chiefs fear Chinese cyber attack". The Times. Archived from the original on 2025-04-19. Retrieved 2025-10-17.

- ^ "MI5 alert on China's cyberspace spy threat". The Times. 2007-12-01. Archived from the original on 2025-04-19. Retrieved 2025-10-17.

- ^ "Huawei 5G kit must be removed from UK by 2027". BBC News. 14 July 2020. Archived from the original on 11 August 2020. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ Norden, Jasmine. "UK university halted forced labour research after China pressure, lawyers claim". independent.co.uk. The Independent. Retrieved 3 November 2025.

- ^ Wood, Poppy. "China pressured British university to stop human rights research". telegraph.co.uk. The Telegraph. Retrieved 3 November 2025.

- ^ Hawkins, Amy. "UK university halted human rights research after pressure from China". theguardian.com. The Guardian. Retrieved 3 November 2025.

- ^ Das, Shanti (23 June 2019). "Beijing leans on UK dons to praise Communist Party and avoid 'the three Ts — Tibet, Tiananmen and Taiwan'". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- ^ Kang, Dake (20 May 2021). "Chinese authorities order video denials by Uyghurs of abuses". apnews.com. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 7 November 2023. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ Wintour, Patrick. "China imposes sanctions on UK MPs, lawyers and academic in Xinjiang row". theguardian.com. The Guardian. Retrieved 3 November 2025.

- ^ 大汉网络. "Air Asia, British Airways considering C919". english.ningbo.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 2018-01-01. Retrieved 2017-12-31.

- ^ Templeton, Dan. "CRRC wins first British contract". International Rail Journal. Archived from the original on 2017-12-31. Retrieved 2017-12-31.

- ^ "China Watch". The Telegraph. 2016-08-17. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 2016-09-15. Retrieved 2017-12-31.

- ^ "NewsChina Magazine". www.newschinamag.com. Archived from the original on 2018-01-11. Retrieved 2017-12-31.

- ^ Kit-ching Chan Lau (1 December 1978). Anglo-Chinese Diplomacy 1906–1920: In the Careers of Sir John Jordan and Yuan Shih-kai. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 168–. ISBN 978-962-209-010-1. Archived from the original on 23 April 2024. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ "China Brings Its Past to Ping-Pong's Birthplace". The New York Times. 29 July 2012.

- ^ "International Views of China Turn Slightly More Positive". Pew Research Center. 15 July 2025. Retrieved 16 July 2025.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bickers, Robert A. Britain in China: Community, Culture and Colonialism, 1900-49 (1999)

- Bickers, Robert A. and Jonathan Howlett, eds. Britain and China, 1840-1970: Empire, Finance and War (Routledge, 2015) online review of major scholarly survey

- Brunero, Donna. Britain's Imperial Cornerstone in China: The Chinese Maritime Customs Service, 1854–1949 (Routledge, 2006). Online review

- Carroll, John M. Edge of empires: Chinese elites and British colonials in Hong Kong (Harvard UP, 2009.)

- Cooper, Timothy S. "Anglo-Saxons and Orientals: British-American interaction over East Asia, 1898–1914." (PhD dissertation U of Edinburgh, 2017). online

- Cox, Howard, and Kai Yiu Chan. "The changing nature of Sino-foreign business relationships, 1842–1941." Asia Pacific Business Review (2000) 7#2 pp: 93–110. online

- Dean, Britten (1976). "British informal empire: The case of China 1". Journal of Commonwealth & Comparative Politics. 14 (1): 64–81. doi:10.1080/14662047608447250.

- Dean, Britten. China and Great Britain: The Diplomacy of Commercial Relations, 1860–1864 (1974)

- Fairbank, John King. Trade and diplomacy on the China coast: The opening of the treaty ports, 1842-1854 (Harvard UP, 1953), a major scholarly study; online

- Gerson, J.J. Horatio Nelson Lay and Sino-British relations. (Harvard University Press, 1972)

- Gregory, Jack S. Great Britain and the Taipings (1969) online

- Gull E. M. British Economic Interests In The Far East (1943) online

- Hanes, William Travis, and Frank Sanello. The opium wars: the addiction of one empire and the corruption of another (2002)

- Hinsley, F.H. ed. British Foreign Policy under Sir Edward Grey (Cambridge UP, 1977) ch 19, 21, 27, covers 1905 to 1916..

- Horesh, Niv. Shanghai's bund and beyond: British banks, banknote issuance, and monetary policy in China, 1842–1937 (Yale UP, 2009)

- Keay, John. The Honourable Company: a history of the English East India Company (1993)

- Kirby, William C. "The Internationalization of China: Foreign Relations at home and abroad in the Republican Era." The China Quarterly 150 (1997): 433–458. online

- Le Fevour, Edward. Western enterprise in late Ch'ing China: A selective survey of Jardine, Matheson and Company's operations, 1842–1895 (East Asian Research Center, Harvard University, 1968)

- Lodwick, Kathleen L. Crusaders against opium: Protestant missionaries in China, 1874–1917 (UP Kentucky, 1996)

- Louis, Wm Roger. British strategy in the Far East, 1919-1939 (1971) online

- McCordock, Stanley. British Far Eastern Policy 1894–1900 (1931) online

- Melancon, Glenn. "Peaceful intentions: the first British trade commission in China, 1833–5." Historical Research 73.180 (2000): 33–47.

- Melancon, Glenn. Britain's China Policy and the Opium Crisis: Balancing Drugs, Violence and National Honour, 1833–1840 (2003) excerpt and text search

- Murfett, Malcolm H. "An Old Fashioned Form of Protectionism: The Role Played by British Naval Power in China from 1860–1941." American Neptune 50.3 (1990): 178–191.

- Porter, Andrew, ed. The Oxford history of the British Empire: The nineteenth century. Vol. 3 (1999) pp 146–169. online

- Ridley, Jasper. Lord Palmerston (1970) pp 242–260, 454–470; online

- Spence, Jonathan. "Western Perceptions of China from the Late Sixteenth Century to the Present" in Paul S. Ropp, ed. Heritage of China: Contemporary Perspectives on Chinese Civilization (1990) excerpts

- Suzuki, Yu. Britain, Japan and China, 1876–1895: East Asian International Relations before the First Sino–Japanese War (Routledge, 2020).

- Swan, David M. "British Cotton Mills in Pre-Second World War China." Textile History (2001) 32#2 pp: 175–216.

- Wang, Gungwu. Anglo-Chinese Encounters since 1800: War, Trade, Science, and Governance (Cambridge University Press, 2003)

- Woodcock, George. The British in the Far East (1969) online

- Yen-p’ing, Hao. The Commercial Revolution in Nineteenth- Century China: the rise of Sino-Western Mercantile Capitalism (1986)

Since 1931

[edit]- Albers, Martin, ed. Britain, France, West Germany and the People's Republic of China, 1969–1982 (2016) online

- Barnouin, Barbara, and Yu Changgen. Chinese Foreign Policy during the Cultural Revolution (1998).

- Bickers, Robert. Britain in China: Community, Culture and Colonialism, 1900–49 (1999)

- Boardman, Robert. Britain and the People's Republic of China, 1949–1974 (1976) online

- Breslin, Shaun. "Beyond diplomacy? UK relations with China since 1997." British Journal of Politics & International Relations 6#3 (2004): 409–425.0

- Brown, Kerry. What's Wrong With Diplomacy?: The Future of Diplomacy and the Case of China and the UK (Penguin, 2015)

- Buchanan, Tom. East Wind: China and the British Left, 1925–1976 (Oxford UP, 2012).

- Clayton, David. Imperialism Revisited: Political and Economic Relations between Britain and China, 1950–54 (1997)

- Clifford, Nicholas R. Retreat from China: British policy in the Far East, 1937-1941 (1967) online

- Feis, Herbert. The China Tangle (1967), diplomacy during World War II; online

- Friedman, I.S. British Relations with China: 1931–1939 (1940) online

- Garver, John W. Foreign relations of the People's Republic of China (1992) online

- Kaufman, Victor S. "Confronting Communism: U.S. and British Policies toward China (2001) * Keith, Ronald C. The Diplomacy of Zhou Enlai (1989)

- MacDonald, Callum. Britain and the Korean War (1990)

- Mark, Chi-Kwan. The Everyday Cold War: Britain and China, 1950–1972 (2017) online review

- Martin, Edwin W. Divided Counsel: The Anglo-American Response to Communist Victory in China (1986)

- Osterhammel, Jürgen. "British business in China, 1860s–1950s." in British Business in Asia since 1860 (1989): 189–216. online

- Ovendale, Ritchie."Britain, the United States, and the Recognition of Communist China." Historical Journal (1983) 26#1 pp 139–58.

- Porter, Brian Ernest. Britain and the rise of communist China: a study of British attitudes, 1945–1954 (Oxford UP, 1967).

- Rath, Kayte. "The Challenge of China: Testing Times for New Labour’s ‘Ethical Dimension." International Public Policy Review 2#1 (2006): 26–63.

- Roberts, Priscilla, and Odd Arne Westad, eds. China, Hong Kong, and the Long 1970s: Global Perspectives (2017) excerpt

- Shai, Aron. Britain and China, 1941–47 (1999) online.

- Shai, Aron. "Imperialism Imprisoned: the closure of British firms in the People's Republic of China." English Historical Review 104#410 (1989): 88–109 online.

- Silverman, Peter Guy. "British naval strategy in the Far East, 1919-1942 : a study of priorities in the question of imperial defense" (PhD dissertation U of Toronto, 1976) online

- Tang, James Tuck-Hong. Britain's Encounter with Revolutionary China, 1949—54 (1992)

- Tang, James TH. "From empire defence to imperial retreat: Britain's postwar China policy and the decolonization of Hong Kong." Modern Asian Studies 28.2 (1994): 317–337.

- Thorne, Christopher G. The limits of foreign policy; the West, the League, and the Far Eastern crisis of 1931-1933 (1972) online

- Trotter, Ann. Britain and East Asia 1933–1937 (1975) online.

- Wolf, David C. "`To Secure a Convenience': Britain Recognizes China— 1950." Journal of Contemporary History 18 (April 1983): 299–326. online

- Xiang, Lanxin. Recasting the imperial Far East : Britain and America in China, 1945-1950 (1995) online

Primary sources

[edit]- Lin Zexu, Deng Tingzhen 鄧廷楨 (1839) ["Letter to the Queen of England from the imperial commissioner and the provincial authorities requiring the interdiction of opium"], translation published in The Chinese Repository volume 8, number 1, May 1839, p. 9; also available at HathiTrust; an image of the original letter is also available

- Ruxton, Ian (ed.), The Diaries of Sir Ernest Satow, British Envoy in Peking (1900–06) in two volumes, Lulu Press Inc., April 2006 ISBN 978-1-4116-8804-9 (Volume One); ISBN 978-1-4116-8805-6 (Volume Two)fu

External links

[edit]China–United Kingdom relations

View on GrokipediaHistory

Early Trade and Diplomatic Contacts (17th–18th Centuries)

The earliest documented personal contact between individuals from China and Britain occurred in the late 17th century when Shen Fuzong, a Chinese Catholic convert from Nanjing born around 1658, visited England in 1687 as part of a Jesuit entourage promoting missions in China. Shen, also known as Michael Alphonsus Shen Fu-Tsung, met King James II, who commissioned a portrait by Godfrey Kneller, and traveled to Oxford University, where he assisted in cataloging Chinese books at the Bodleian Library under Thomas Hyde. This visit marked the first recorded instance of a Chinese person in Britain, though Shen died in 1691 near Mozambique while attempting to return to China via Lisbon after joining the Jesuits.[11][12] British trade with China during this period was primarily conducted through the English East India Company (EIC), established in 1600 initially for Indian Ocean commerce but expanding to East Asia by the mid-17th century. Sporadic EIC voyages to Chinese ports began around 1637, focusing on silk, porcelain, and rhubarb, but faced restrictions under the Qing dynasty's haijin maritime bans and the Canton System, which confined foreign trade to Guangzhou (Canton). By the close of the 17th century, the EIC secured a foothold by establishing a trading factory in Canton circa 1699, importing Chinese luxuries while exporting woolens and metals, though volumes remained modest compared to later tea-dominated exchanges.[13][12] Diplomatic engagement was negligible until the 1793 Macartney Embassy, the first formal British mission to the Qing court, dispatched by King George III to address growing trade imbalances—British demand for Chinese tea, silk, and porcelain outstripping exports of British goods—and to seek expanded access beyond Canton. Led by George Macartney, the expedition departed Portsmouth in September 1792 with two warships, arriving at Dagu near Tianjin in June 1793 before proceeding to Beijing for an audience with Emperor Qianlong on his 83rd birthday. The mission proposed opening additional ports like Ningbo and Zhoushan, a resident British envoy in Beijing, and tariff reductions, but Qianlong rebuffed these as tributary overtures unnecessary to a self-sufficient empire, while Macartney refused the kowtow ritual, citing incompatibility with British customs. The embassy returned in 1794 without concessions, highlighting mutual incomprehension: British mercantilist ambitions clashing with Qing tributary worldview.[14][15][16]19th Century Conflicts and Unequal Treaties

British trade with China in the early 19th century was restricted under the Qing dynasty's Canton System, confining foreign commerce to the port of Canton (Guangzhou) and requiring dealings through licensed guilds, which favored Chinese merchants and imposed unfavorable terms on British traders facing a persistent trade deficit due to high demand for Chinese tea, silk, and porcelain.[17] To address this imbalance and stem the outflow of silver, British merchants, supported by the East India Company, increasingly exported opium grown in India, with imports rising to over 1,000 tonnes annually by the 1830s, exacerbating addiction and social issues in China while generating profits for Britain.[17] In 1839, Qing commissioner Lin Zexu enforced an imperial ban on opium by besieging foreign warehouses in Canton, compelling the surrender and destruction of approximately 20,000 chests (over 1,000 tonnes) of British-owned opium at Humen, which the British government viewed as unlawful confiscation of private property worth millions, prompting demands for compensation and freer trade.[18] [17] These tensions escalated into the First Opium War (1839–1842), initiated by British naval expeditions under commanders like Charles Elliot, who blockaded ports and captured key sites such as Ningbo and Zhenjiang, exploiting Qing military weaknesses including outdated junks against steam-powered warships and disciplined infantry.[3] The conflict ended with the Treaty of Nanking, signed on August 29, 1842, aboard HMS Cornwallis, which imposed on China the cession of Hong Kong Island to Britain in perpetuity, the opening of five treaty ports (Canton, Amoy, Foochow, Ningpo, and Shanghai) to foreign residence and trade, payment of 21 million silver dollars in indemnities (6 million for destroyed opium, 3 million for Hong Kong debts, and 12 million for war costs), and the abolition of the Canton System's monopolies, establishing fixed low tariffs at 5% ad valorem that disadvantaged China's fiscal sovereignty.[3] These provisions exemplified the "unequal treaties" framework, granting extraterritorial legal privileges to Britons in China and prioritizing Western commercial access over Qing regulatory authority, though Britain framed the war as a defense of free trade principles against restrictive policies.[3] Dissatisfaction with Nanking's limitations, including unlegalized opium trade and restricted inland access, fueled the Second Opium War (1856–1860), sparked by the Arrow incident on October 8, 1856, when Chinese authorities boarded the British-registered lorcha Arrow in Canton, arresting crew members suspected of piracy and removing the flag, which Britain claimed violated treaty rights and demanded apology for, leading to escalated bombardment and capture of Canton by Anglo-French forces.[4] Allied British and French troops, later joined by U.S. observers, advanced northward, capturing the Taku Forts in 1858 and 1860 despite fierce resistance, and in 1860 sacked Beijing's Summer Palace in retaliation for Qing violation of truce terms, forcing Emperor Xianfeng's flight.[4] The resulting Treaty of Tianjin (signed June 26–28, 1858, and ratified 1860) legalized the opium trade, opened 11 additional ports including Niuzhuang, Danshui, and Hankou, permitted foreign travel and trade inland, allowed Christian missionary propagation, established permanent diplomatic legations in Beijing, and imposed indemnities of 8 million taels; supplemented by the Convention of Peking (October 24–25, 1860), which ceded the Kowloon Peninsula to Britain, enhancing Hong Kong's defenses, and confirmed prior concessions amid China's internal Taiping Rebellion weakening its position.[4] These treaties collectively eroded Qing sovereignty by embedding foreign concessions, tariff controls, and extraterritoriality, enabling British economic penetration—such as Jardine Matheson firm's dominance in shipping and trade—while exposing China to further vulnerabilities, though the conflicts stemmed from mutual incomprehension of legal and commercial norms, with Britain's naval superiority enforcing outcomes that prioritized property restitution and market access over moral critiques of opium.[4] The unequal framework persisted, influencing subsequent spheres of influence and contributing to China's "Century of Humiliation" narrative, yet reflected Britain's strategic response to perceived trade barriers rather than unprovoked imperialism alone.[4]Republican Era and World War II (1912–1949)

![INF3-331 Unity of Strength Chiang-Kai-Shek and Winston Churchill heads, with Nationalist China flag and Union Jack.jpg][float-right] The Republic of China was established on January 1, 1912, following the overthrow of the Qing dynasty. Britain extended de facto recognition to the provisional Republican government under Sun Yat-sen and subsequently to Yuan Shikai's presidency, with British Minister Sir John Jordan playing a key role in facilitating the transition through diplomatic engagement in Beijing.[19] In 1913, Britain joined a five-power consortium (including France, Germany, Japan, and Russia) to provide the Reorganization Loan of approximately £25 million (equivalent to about 300 million Mexican dollars at the time) to Yuan's government, aimed at consolidating central authority amid warlord fragmentation, though the funds were partly diverted to military purposes rather than reforms.[20] Relations deteriorated in the 1920s amid rising Chinese nationalism during the warlord era and the Northern Expedition. The May Thirtieth Movement erupted on May 30, 1925, after British-led Municipal Police in Shanghai's International Settlement killed 13 Chinese protesters and wounded over 50 during demonstrations against Japanese mill management following a worker strike; this sparked nationwide boycotts of British goods, strikes, and the Canton-Hong Kong strike of 1925–1926, which paralyzed Hong Kong's economy for 16 months and involved over 250,000 participants, costing Britain an estimated £5 million in lost trade.[21] These events pressured Britain to concede tariff autonomy to China at the Nanjing Tariff Conference in 1928, allowing the Nationalist government under Chiang Kai-shek—established in Nanjing in 1927—to set its own customs duties for the first time since the unequal treaties, marking a partial revision of imperial privileges in exchange for stabilized relations.[22] Japanese aggression complicated Anglo-Chinese ties in the 1930s, with Britain adopting a policy of non-intervention after the 1931 Mukden Incident and 1937 Marco Polo Bridge Incident, prioritizing appeasement of Japan to safeguard interests in Hong Kong and concessions amid global economic depression.[23] The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) aligned the two nations as wartime partners after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 drew Britain into direct conflict; the UK supplied China via the Burma Road until its closure in 1940, reopened in 1941 under pressure, and coordinated military efforts, including British forces defending Burma against Japanese invasion in 1942, where Chinese expeditionary troops under Chiang aided Allied retreats.[24] At the 1943 Cairo Conference, Prime Minister Winston Churchill met with Chiang Kai-shek and U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt to affirm China's sovereignty over territories lost to Japan, such as Taiwan and Manchuria.[25] A pivotal diplomatic achievement came with the Sino-British Treaty signed on January 11, 1943, in Chongqing, under which Britain relinquished extraterritorial rights, British settlements (including the Shanghai International Settlement and concessions in Tianjin, Guangzhou, and Xiamen), and legation guards, while China agreed to protect British property and religious freedoms; this treaty, negotiated amid U.S. pressure and wartime solidarity, symbolized the end of most unequal treaty remnants and restored Chinese judicial sovereignty over British subjects.[26] Post-1945, as the Chinese Civil War resumed between Nationalists and Communists, Britain maintained sympathy for Chiang's government, providing limited surplus military equipment like Sten guns post-WWII and adhering to non-interference per the 1945 Moscow Agreement, though economic restoration efforts faltered amid hyperinflation and corruption under the Nationalists. By 1949, advancing Communist forces prompted British evacuations from mainland concessions, setting the stage for the Republic's retreat to Taiwan.[27]Recognition of the People's Republic and Early Cold War (1949–1970s)

The United Kingdom became the first major Western power to recognize the People's Republic of China (PRC), proclaimed on October 1, 1949, as the sole legal government of all China on January 6, 1950.[28] This de jure recognition, issued by the Attlee Labour government via a formal diplomatic note, reflected a pragmatic assessment of the communists' effective control over the mainland following the Chinese Civil War, prioritizing the protection of extensive British economic assets, trade routes, and consular interests in China over ideological opposition to the regime.[29] [30] Unlike the United States, which continued recognizing the Republic of China on Taiwan until 1979, the UK sought to mitigate losses from the communist victory by engaging Beijing directly, though the PRC delayed reciprocal full diplomatic ties.[31] The Korean War, erupting in June 1950, severely tested this early recognition, as British Commonwealth forces fought under United Nations command against North Korean invaders and subsequent Chinese "volunteer" armies, leading to a diplomatic standoff.[32] Beijing interpreted UK participation alongside the US as complicity in encirclement, resulting in frozen relations, expulsion of British diplomats from key areas, and heightened tensions that persisted into the 1950s.[33] Despite a US-led trade embargo, the UK maintained limited bilateral commerce, exporting machinery, chemicals, and metals to support China's post-war reconstruction; these exports averaged 0.2% of total UK exports from 1949 to 1954, increasing modestly to 0.6% in subsequent years as British firms defended pre-1949 market positions.[34] [35] Diplomatic contacts remained at the chargé d'affaires level through the 1950s and 1960s, hampered by China's alignment with the Soviet bloc and mutual suspicions amid Cold War divisions. Relations further soured during the Cultural Revolution, culminating in the August 22, 1967, assault by Red Guards on the British mission in Beijing, where the building was set ablaze, staff were besieged for days, and Donald Hopson, the chargé d'affaires, was briefly detained before evacuation.[36] This incident, amid broader attacks on foreign legations, prompted the UK to withdraw its remaining diplomats and reduce ties to a minimal mission in Shanghai, underscoring Beijing's internal chaos and anti-imperialist fervor.[37] A gradual thaw emerged in the early 1970s, influenced by China's rift with the Soviet Union and US overtures to Beijing. On March 13, 1972, the two governments issued a joint communiqué agreeing to exchange ambassadors, elevating relations to full diplomatic status; in reciprocity, the UK closed its consulate in Tamsui, Taiwan, affirming the "One China" principle as articulated by the PRC.[38] [39] This upgrade, following Richard Nixon's February 1972 visit to China, marked the end of two decades of constrained engagement, enabling resumed high-level dialogue while the UK balanced recognition of PRC sovereignty with unofficial links to Taiwan.Détente and Normalization (1970s–1990s)

In March 1972, the United Kingdom and the People's Republic of China upgraded their diplomatic relations from chargé d'affaires to full ambassadorial level, marking a significant step toward normalization after over two decades of limited engagement. This agreement, formalized in a joint communiqué signed in Beijing on 13 March, reflected mutual commitments to improved bilateral ties amid broader Cold War détente dynamics, including the United States' rapprochement with China.[2][31] The move followed the UK's early recognition of the PRC in 1950 but addressed lingering barriers, such as the UK's prior support for Taiwan in the UN until 1971. Former British Prime Minister Edward Heath played a pivotal role in fostering this thaw, visiting China from 21 May to 2 June 1974 as leader of the opposition Conservative Party. Heath met Chairman Mao Zedong and Premier Zhou Enlai, receiving high-level ceremonies comparable to those for heads of state, and discussed economic cooperation and global issues.[40] His trip, the first by a major Western opposition leader post-Nixon's 1972 visit, signaled London's intent to prioritize pragmatic engagement over ideological confrontation, paving the way for increased trade delegations and contracts in sectors like energy and manufacturing. Bilateral trade volumes began expanding steadily, with UK exports to China rising from modest levels in the early 1970s to support China's post-Cultural Revolution reforms under Deng Xiaoping.[41] Tensions over Hong Kong emerged as a core challenge to normalization. British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher visited Beijing in September 1982 to negotiate the territory's future, as the New Territories lease was set to expire in 1997, threatening the viability of Hong Kong's economy reliant on contiguous land. Chinese leaders, including Deng Xiaoping, insisted on reclaiming sovereignty, rejecting extensions of British administration and warning of unilateral action if needed. These talks, spanning 1982–1984, involved 22 rounds of negotiations and culminated in the Sino-British Joint Declaration signed on 19 December 1984. The treaty committed China to establishing Hong Kong as a Special Administrative Region with a "high degree of autonomy" for 50 years post-handover under the "one country, two systems" framework, preserving its capitalist system, legal traditions, and freedoms except in foreign and defense affairs.[42][43] The 1980s saw sustained economic détente, with UK firms securing major contracts, such as Rolls-Royce engine deals and North Sea oil technology transfers, amid China's opening to foreign investment. However, the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown tested relations. Thatcher condemned the military suppression of protests on 4 June 1989 as "indiscriminate shooting of unarmed people," leading to UK suspension of arms sales and high-level contacts, though diplomatic channels remained open due to Hong Kong obligations. By the early 1990s, ties stabilized, with resumed ministerial visits and focus on implementing the Joint Declaration, reflecting pragmatic mutual interests despite ideological divergences and Western sanctions.[44]Hong Kong Handover and Post-Cold War Engagement (1997–2010)

The handover of Hong Kong from the United Kingdom to the People's Republic of China occurred at midnight on July 1, 1997, transferring sovereignty over the territory, which had been under British administration since 1841, in accordance with the Sino-British Joint Declaration signed on December 19, 1984.[45][42] Under the declaration, registered as a UN treaty, China committed to preserving Hong Kong's capitalist system, high degree of autonomy, independent judiciary, and civil liberties for 50 years through the "one country, two systems" framework, with these obligations outlined in Hong Kong's Basic Law, which entered force upon handover.[42] The ceremony in Hong Kong featured British Prime Minister Tony Blair and Prince Charles attending, symbolizing the formal end of British extraterritorial rights in China stemming from 19th-century treaties.[45] Immediately following the handover, China implemented measures that prompted UK concerns regarding adherence to the Joint Declaration, including the dissolution of Hong Kong's partially elected Legislative Council on July 1, 1997, and its replacement with a Provisional Legislative Council appointed by Beijing, which excluded democratic representatives and passed laws restricting civil society groups.[46] The UK government, through Foreign Secretary Robin Cook, publicly stated that these actions placed China in a "state of ongoing non-compliance" with commitments to democratic processes and autonomy, though London lacked enforcement mechanisms post-sovereignty transfer.[46] Despite these frictions, the UK maintained diplomatic channels to monitor implementation, including through the Sino-British Joint Liaison Group, which continued until its dissolution in 2000, and emphasized that Hong Kong's prosperity depended on upholding promised freedoms to sustain its role as a global financial hub.[42] Post-Cold War engagement shifted toward economic and strategic cooperation, with the UK prioritizing commercial opportunities amid China's rapid growth following its 2001 WTO accession, which the UK supported to integrate Beijing into global rules.[47] Bilateral trade volume reached approximately $7.874 billion in 1999, reflecting a 19.6% year-on-year increase driven by UK exports of machinery and services alongside rising Chinese imports of consumer goods.[48] High-level visits underscored this pivot: Blair's October 6–9, 1998, trip to Beijing and Shanghai focused on business ties, including the opening of the first British insurance firm in China, and established a strategic dialogue mechanism for regular prime ministerial exchanges.[49][50] UK imports from China grew annually from 1999 onward, fueled by manufacturing offshoring, though this widened the trade deficit; by 2008, Prime Minister Gordon Brown's visit to Beijing emphasized doubling bilateral trade volumes, green technology collaboration, and investment, while privately raising human rights issues without derailing economic priorities.[51][52] Tensions persisted over Hong Kong's political evolution, with the UK critiquing Beijing's 2004 intervention to block full democracy legislation under Article 23 of the Basic Law and the National People's Congress's 2007 decision deferring universal suffrage beyond 2012, viewing these as erosions of electoral autonomy pledged in the Joint Declaration.[46] Nonetheless, UK policy under Blair and Brown balanced advocacy for reforms—such as retaining British judges on Hong Kong's Court of Final Appeal until their phased withdrawal around 2009—with pragmatic engagement, recognizing China's economic leverage and the mutual benefits of deepened ties in education, science, and finance during this decade of globalization.[53] This approach reflected a causal prioritization of verifiable economic gains over unenforceable political ideals, though critics in Westminster argued it understated risks to Hong Kong's rule of law.[51]The "Golden Era" and Subsequent Cooling (2010–2020)

Under Prime Minister David Cameron, the United Kingdom pursued intensified economic engagement with China following the 2010 coalition government's formation, emphasizing trade and investment over human rights concerns. Chancellor George Osborne advocated for a "golden decade" in UK-China relations during a 2015 visit to China, framing the partnership as mutually beneficial amid Britain's post-financial crisis recovery. This shift was marked by Cameron's December 2013 trip to Beijing, the first bilateral visit since 2009, which resulted in agreements on financial services and infrastructure.[54][47] The pinnacle of this "Golden Era" occurred during President Xi Jinping's state visit to the UK from October 19 to 23, 2015, hosted by Queen Elizabeth II and Cameron. Cameron described the visit as inaugurating a "golden era" of stronger economic ties, yielding commercial deals valued at approximately £40 billion, including investments in nuclear energy and aviation. Notable outcomes included Chinese state-owned CGN's stake in the Hinkley Point C nuclear reactor project and Queen's University Belfast's £100 million campus in Dongguan. Bilateral trade in goods and services grew significantly, with UK exports to China tripling to £30 billion by 2019 from 2010 levels, though the UK maintained a persistent goods trade deficit exceeding £20 billion annually.[55][56][57] Signs of cooling emerged under Prime Minister Theresa May from 2016, as security reviews delayed Hinkley Point approval until September 2016 amid espionage concerns. The 2016 Brexit referendum further complicated dynamics, yet engagement persisted until escalating frictions in 2019. Protests in Hong Kong against a proposed extradition bill drew UK criticism, rooted in the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration guaranteeing the territory's autonomy until 2047. China's imposition of a National Security Law on Hong Kong in June 2020 prompted the UK to suspend its extradition treaty with China in July and extend residency rights to up to 3 million British National (Overseas) passport holders by the end of 2020.[58][59] Parallel tensions arose over Huawei's role in UK 5G networks. Despite initial allowances for non-sensitive equipment in 2019, mounting intelligence concerns about backdoors and US pressure led to a July 2020 decision by the Johnson government to ban Huawei from core infrastructure by 2027, citing national security risks. These developments, compounded by allegations of Uyghur repression in Xinjiang—which the UK labeled potential genocide in 2020—marked a decisive pivot from economic optimism to strategic caution, with trade volumes reaching £79 billion in goods and services by 2020 but bilateral trust eroded.[60][61][62]Developments in the 2020s