Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Zooming user interface

View on Wikipedia

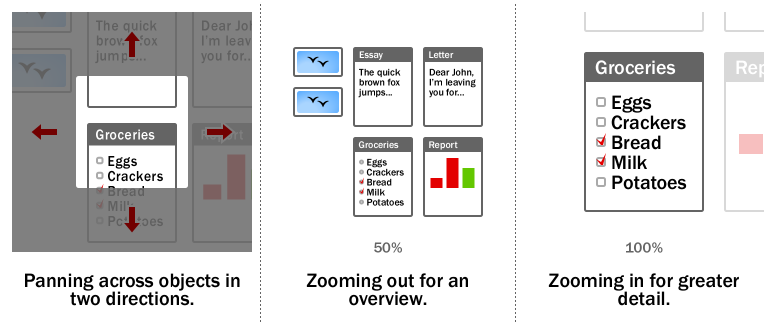

In computing, a zooming user interface or zoomable user interface (ZUI, pronounced zoo-ee) is a type of graphical user interface (GUI) on which users can change the scale of the viewed area in order to see more detail or less, and browse through different documents. Information elements appear directly on an infinite virtual desktop (usually created using vector graphics), instead of in windows. Users can pan across the virtual surface in two dimensions and zoom into objects of interest. For example, as you zoom into a text object it may be represented as a small dot, then a thumbnail of a page of text, then a full-sized page and finally a magnified view of the page.

ZUIs use zooming as the main metaphor for browsing through hyperlinked or multivariate information. Objects present inside a zoomed page can in turn be zoomed themselves to reveal further detail, allowing for recursive nesting and an arbitrary level of zoom.

When the level of detail present in the resized object is changed to fit the relevant information into the current size, instead of being a proportional view of the whole object, it's called semantic zooming.[1]

Some consider the ZUI paradigm as a flexible and realistic successor to the traditional windowing GUI, being a Post-WIMP interface.[citation needed]

History

[edit]Ivan Sutherland presented the first program for zooming through and creating graphical structures with constraints and instancing, on a CRT in his Sketchpad program in 1962.[2]

A more general interface was done by the Architecture Machine Group in the 1970s at MIT. Hand tracking, touchscreen, joystick, and voice control were employed to control an infinite plane of projects, documents, contacts, video and interactive programs. One of the instances of this project was called Spatial Dataland.[3]

Another GUI environment of the 70's, which used the zooming idea was Smalltalk at Xerox PARC, which had infinite desktops (only later named such by Apple Computer), that could be zoomed in upon from a birds eye view after the user had recognized a miniature of the window setup for the project.

The longest running effort to create a ZUI has been the Pad++ project begun by Ken Perlin, Jim Hollan, and Ben Bederson at New York University and continued at the University of New Mexico under Hollan's direction. After Pad++, Bederson developed Jazz, then Piccolo,[4] and now Piccolo2D[5] at the University of Maryland, College Park, which is maintained in Java and C#. More recent ZUI efforts include Archy by the late Jef Raskin, ZVTM developed at INRIA (which uses the Sigma lens[6] technique), and the simple ZUI of the Squeak Smalltalk programming environment and language. The term ZUI itself was coined by Franklin Servan-Schreiber and Tom Grauman while they worked together at the Sony Research Laboratories. They were developing the first Zooming User Interface library based on Java 1.0, in partnership with Prof. Ben Bederson, University of New Mexico, and Prof. Ken Perlin, New York University.

GeoPhoenix, a Cambridge, MA, startup associated with the MIT Media Lab, founded by Julian Orbanes, Adriana Guzman, Max Riesenhuber, released the first mass-marketed commercial Zoomspace in 2002–03 on the Sony CLIÉ personal digital assistant (PDA) handheld, with Ken Miura of Sony

In 2002, Pieter Muller extended the Oberon System with a zooming user interface and named it Active Object System (AOS).[7] In 2005, due to copyright issues, it was renamed to Bluebottle, and in 2008, to A2.

In 2005, Franklin Servan-Schreiber founded Zoomorama, based on work he did at the Sony Research Laboratories in the mid-1990s. The Zooming Browser for Collage of High Resolution Images was released in Alpha in October 2007. Zoomorama's browser is all Flash-based. In 2010, project development ended, but many examples are still available on the site.

In 2006, Hillcrest Labs introduced the HoME television navigation system, the first graphical, zooming interface for television.[8]

In 2007, Microsoft's Live Labs released a zooming UI for web browsing called Microsoft Live Labs Deepfish for the Windows Mobile 5 platform.

Apple's iPhone (premiered June 2007) uses a stylized form of ZUI, in which panning and zooming are performed through a touch user interface (TUI). A more fully realised ZUI is present in the iOS home screen (as of iOS 7), with zooming from the homescreen in to folders and finally in to apps. The photo app zooms out from a single photo to moments, to collections, to years, and similarly in the calendar app with day, month and year views.[9] It is not a full ZUI implementation since these operations are applied to bounded spaces (such as web pages or photos) and have a limited range of zooming and panning.

From 2008 to 2010, GNOME Shell used a zooming user interface for virtual workspaces management.[10] This ZUI was eventually replaced by a different, scrolling-based design.

In 2017, bigpictu.re offered an infinite (pan and zoom) notepad as a web application based on one of the first ZUI open-source libraries.[11]

In 2017, Zircle UI was released. It is an open source UI library that uses zoomable navigation and circular shapes.[12]

In 2022, the Miro collaboration platform, which uses a zooming user interface, reported 40 million users. It was released in 2011 as RealtimeBoard, eventually being rebranded to Miro in 2019.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Peter Bright (13 September 2011). "Hands-on with Windows 8: A PC operating system for the tablet age". Ars Technica.

- ^ Sketchpad: A man-machine graphical communication system

- ^ Dataland: the MIT's '70s media room concept that influenced the Mac

- ^ Piccolo (formerly Jazz): ZUI toolkit for Java and C# (no longer actively maintained)

- ^ Piccolo2D: Piccolo's successor.

- ^ "Sigma lenses: focus-context transitions combining space, time and translucence", Proceedings of the twenty-sixth annual SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems, 2008

- ^ Muller, Pieter Johannes (2002). The active object system design and multiprocessor implementation (PDF) (PhD). Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Zürich (ETH Zurich). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-05-28. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

- ^ Popular Mechanics 2007. Retrieved November 11, 2011. Glen Derene. Wii 2.0: Loop remote lets you click by gesture.

- ^ "iOS 7". Archived from the original on 2013-09-06. Retrieved 2017-09-19.

- ^ "GNOME Shell, 2010-02-20 build: a Zoomable User Interface". YouTube. 2010-02-20. Archived from the original on 2021-12-12. Retrieved 2020-12-26.

- ^ "bigpicture.js, a library that allows infinite panning and infinite zooming in HTML pages". GitHub. 2015.

- ^ "Zircle UI: A frontend library to develop zoomable user interfaces". GitHub. 2017–2021.

External links

[edit]Zooming user interface

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Fundamentals

Core Concept

A zooming user interface (ZUI) is a graphical user interface paradigm that enables users to navigate vast information spaces by continuously scaling the view of content on a virtual canvas, treating the entire interface as a unified, scalable plane rather than discrete windows or fixed layouts. In this approach, information objects—ranging from text and images to complex data structures—are embedded within a continuous two-dimensional space, allowing seamless exploration without traditional boundaries like menus or scrollbars. Central to the ZUI is the infinite canvas metaphor, which conceptualizes the display as an unbounded, high-resolution plane where content can be organized hierarchically or spatially across multiple scales, free from the constraints of fixed window sizes or hierarchical menus. This setup supports the representation of large datasets by dynamically adjusting detail levels based on the current magnification, preserving the overall structure while revealing or abstracting elements as needed. The core mechanics of a ZUI revolve around two primary operations: panning, which facilitates lateral movement across the canvas at a constant scale, and zooming, which adjusts the magnification to delve into finer details or gain a broader overview, thereby enabling fluid transitions between global and local views. These actions work in tandem to provide exponential navigation efficiency in expansive virtual environments, with zooming acting as an accelerator for traversing scale rather than just spatial extent. Unlike traditional scrolling interfaces, which shift content linearly within a fixed viewport and often disrupt contextual awareness by clipping elements, a ZUI maintains the relative positions and interconnections of all items during navigation, ensuring users retain a persistent sense of the information's spatial and hierarchical relationships. This preservation of context distinguishes ZUI as a multiscale navigation tool, particularly suited for exploring complex, interconnected data. The concept originated in early 1990s research on alternative interface physics to overcome limitations of window-based systems.Comparison to Traditional Interfaces

Traditional user interfaces, such as those relying on fixed windows, hierarchical menus, and linear scrolling, typically fragment the information space into discrete, compartmentalized views that separate overviews from details, often requiring users to navigate through rigid structures like page flips or window switches.[6] This approach limits scalability for large datasets by enforcing spatial separation, where context is lost during transitions between views, increasing the mechanical and cognitive effort needed to reassemble relationships between elements.[6] In comparison, zooming user interfaces (ZUIs) employ a continuous, infinite canvas model that integrates navigation and interaction through panning and semantic zooming, offering fluid, temporal separation between scales rather than discrete compartmentalization.[6] This unified plane preserves spatial continuity, allowing users to explore relationships across multiple levels of detail without abrupt mode changes, thereby reducing disorientation common in traditional hierarchical navigation.[7] A key advantage of ZUIs lies in their ability to maintain contextual awareness at varying magnifications, lowering cognitive load by enabling seamless transitions that reveal element interconnections, unlike the split-attention demands of overview+detail interfaces or the clutter of multiple windows in traditional systems.[6] For instance, folder-based file explorers in conventional UIs often cause disorientation during deep traversals due to repeated overview-detail switches, whereas ZUIs support 30% faster task completion in grouping and navigation by embedding details within a zoomable hierarchy.[7] However, traditional interfaces like multiple windows excel in parallel visual comparisons by leveraging rapid eye movements across simultaneous views, avoiding the reorientation costs of zooming, though they demand more screen real estate and initial setup.[8] ZUIs, by contrast, prioritize immersive exploration over such parallelism, proving more efficient for single-focus tasks in expansive spaces but potentially incurring higher error rates in multi-object assessments due to visual working memory limits.[8]Historical Development

Origins and Early Research

The conceptual foundations of zooming user interfaces (ZUIs) trace back to early computer graphics research. Ivan Sutherland's Sketchpad system in 1963 introduced basic zooming capabilities for interactive drawing on a vector display, allowing users to scale views dynamically.[9] Subsequent developments included the Spatial Data Management System (SDMS) in 1978, developed by William Donelson at the University of North Carolina, which employed zooming as a navigation metaphor for visualizing and interacting with large databases containing graphical, textual, and filmic information on a large-scale display.[10] The concept of ZUIs gained prominence in the early 1990s within human-computer interaction (HCI) research, primarily at institutions such as New York University (NYU) and Bellcore (a research arm succeeding parts of Bell Labs). This period built on earlier work to address limitations in traditional interfaces by enabling fluid navigation through vast information spaces via continuous magnification and scaling. This approach was inspired by the need for more intuitive ways to explore complex digital environments, drawing on principles from information visualization to create seamless transitions between overview and detail views.[11][12] Early explorations in the 1990s were influenced by ideas from cartography, where zooming simulates real-world map navigation to reveal finer details without losing spatial context, and from hyperbolic geometry, which provided a mathematical foundation for non-Euclidean representations of hierarchical or expansive data structures. Researchers like Ken Perlin and David Fox at NYU introduced these concepts in their Pad system, first demonstrated in 1989 at an NSF workshop and formally presented in 1993, an infinite-resolution canvas that allowed users to zoom smoothly across scales, motivated by the desire to transcend fixed-window constraints and support emergent applications like electronic marketplaces. Building on this, Ben Bederson and James Hollan at Bellcore developed Pad++ in 1994, emphasizing multiscale physics to handle dynamic content organization.[13][14] Theoretical advancements solidified these foundations through works on "information landscapes," conceptualizing digital content as navigable terrains where scale becomes an explicit dimension. George Furnas and Ben Bederson's 1995 space-scale diagrams formalized how multiscale interfaces could represent spatial and magnification relationships, enabling analysis of navigation efficiency in large datasets. These efforts highlighted the need for scalable UIs beyond the Windows, Icons, Menus, and Pointers (WIMP) paradigm, which faltered with exponentially growing hypermedia and datasets by imposing rigid hierarchies and limited viewport sizes. Initial motivations centered on empowering users to manage overwhelming volumes of information, such as scientific data or interconnected documents, through cognitively natural zooming rather than discrete page flips or scrolling.[15][16]Key Projects and Milestones

The Pad++ project, initiated in 1993 at New York University by Ben Bederson and James Hollan, represented one of the first practical implementations of a zooming user interface (ZUI) for document editing and information visualization on affordable hardware, running through 2000 and enabling fluid scaling of graphical content across multiple levels of detail.[17] This system introduced core ZUI mechanics, such as infinite canvas navigation and hierarchical object rendering, which supported exploratory tasks in large datasets.[1] Building on Pad++, the Jazz framework emerged in the late 1990s as an open-source Java library developed by Bederson, Jonathon Meyer, and Lance Good, providing extensible tools for creating ZUI applications with scene graph structures.[18] Jazz facilitated developer adoption by abstracting rendering and interaction complexities, allowing integration into diverse graphical environments.[19] Similarly, the Piccolo framework, released in 2001 for both Java (as Piccolo2D) and .NET platforms, extended these concepts into a monolithic toolkit optimized for structured 2D graphics and ZUIs, further promoting cross-platform use.[20] These libraries marked a shift toward accessible ZUI development, influencing subsequent tools for browser-based implementations. Key milestones in ZUI advancement included the 1994 UIST paper on Pad++, which formalized the interface physics and garnered significant attention in human-computer interaction research.[17] The 2001 Piccolo release accelerated ZUI experimentation in web contexts, enabling scalable vector graphics for dynamic content.[20] By around 2005, ZUI principles began integrating with emerging touch interfaces, adapting zooming gestures for portable devices and enhancing natural interaction paradigms.[21] Early steps toward commercial viability appeared with Keyhole Inc.'s EarthViewer software in 2001, a mapping tool employing ZUI techniques for seamless zooming across global satellite imagery, which later evolved into Google Earth after Google's 2004 acquisition.[22] This project demonstrated ZUI's potential in real-world applications, bridging academic prototypes to practical geospatial visualization.[23]Design Principles

Navigation and Interaction

In zooming user interfaces (ZUIs), primary interactions revolve around continuous zooming and panning to navigate vast information spaces organized by scale and position. Zooming is typically achieved through mouse wheel scrolling on desktop systems, which provides precise control over magnification levels, or multi-touch pinch gestures on mobile devices, where users spread or contract fingers to scale the view dynamically.[24] Panning complements these by allowing users to drag the viewport across the canvas, simulating spatial movement at the current scale. To balance rapid traversal with accurate positioning, many ZUIs employ rate-based control, where the speed of zooming or panning adjusts proportionally to user input velocity, preventing overshooting in detailed views while enabling quick overviews.[1] Focus+context techniques enhance navigation by providing temporary magnification without requiring a full scene zoom, thus preserving the overall spatial layout. Distortion lenses, such as fisheye views, create localized magnification bubbles that expand details under the cursor or touch point while compressing peripheral areas, allowing users to inspect elements while maintaining awareness of surrounding context. These lenses can be applied dynamically via drag operations, supporting fluid exploration in hierarchical or dense datasets.[25][1] Accessibility in ZUIs extends standard input methods to inclusive alternatives, ensuring equitable navigation for diverse users. Keyboard shortcuts, such as arrow keys for panning and dedicated keys (e.g., '+' or '-') for incremental zooming, enable precise control without relying on pointing devices. Usability studies reveal a characteristic learning curve for ZUIs, with users often experiencing initial disorientation due to the fluid scale changes and lack of fixed anchors, leading to higher error rates in early spatial orientation tasks compared to traditional scrolling interfaces. However, after familiarization, participants demonstrate improved efficiency, particularly for spatial memory and large-scale exploration, as users leverage the integrated overview to build mental maps more effectively.[26][27]Semantic Zooming

Semantic zooming in zooming user interfaces (ZUIs) involves the dynamic transformation of content based on zoom levels, where the semantic meaning and structure of elements change rather than merely scaling graphically. This technique enables a seamless shift from high-level overviews to detailed inspections by altering representations, such as converting icons into editable text or aggregating data into summaries at predefined magnification thresholds. Introduced in the seminal Pad system, semantic zooming operates through expose events that notify objects of the current magnification, prompting them to generate contextually appropriate display items for optimal information density.[13] Central to this process are levels of detail (LOD) mechanisms, which define discrete or continuous representations ranging from coarse overviews—featuring thumbnails or simplified aggregates—to fine details like interactive or editable components. LOD algorithms enhance performance by selecting and rendering only necessary detail levels, avoiding computational overload in expansive ZUI spaces; for instance, low LOD might employ "greeked" outlines for rapid previews, refining to full fidelity at higher magnifications. In implementations like Pad++, spatial indexing via R-trees efficiently manages visibility culling for thousands of objects, while adaptive rendering maintains frame rates above 10 fps by dynamically adjusting detail during animations.[1] Illustrative examples highlight semantic zooming's versatility. In document-based ZUIs, content morphs hierarchically: at distant views, paragraphs collapse into outlines or titles; closer inspection reveals abstracts, then full text with annotations, as seen in Pad's hierarchical text editor where elements fade via transparency ranges for graceful transitions. In mapping applications, semantic zooming progressively unveils geographic details—starting with regional thumbnails, then streets upon moderate zoom, and building labels at finer scales—leveraging LOD for simplified representations that preserve context without clutter.[13][28] Key design challenges include orchestrating smooth transitions to prevent disorienting "pops" between LODs, requiring precise threshold selection based on magnification ranges and user context. Abrupt changes can disrupt spatial cognition, so techniques like dissolve effects or gradual fades—where objects become translucent outside visibility bounds—are essential for continuity. Balancing these thresholds demands careful rules to align with perceptual expectations, often validated through usability studies to minimize cognitive load while upholding rendering efficiency.[13][1]Implementations

Software Frameworks

Software frameworks for zooming user interfaces (ZUIs) typically rely on core components such as rendering engines optimized for scalable vector graphics (SVG) and hierarchical data structures to manage levels of detail (LOD). Rendering engines like Java2D or GDI+ enable efficient drawing of vector-based elements that scale without loss of quality during zoom operations.[20] Hierarchical scene graphs serve as the primary data structure, organizing graphical nodes in a tree-like manner to facilitate LOD management, where detail levels adjust dynamically based on zoom scale to maintain performance.[29] Key frameworks include Piccolo2D, a Java-based toolkit developed from 2005 onward for 2D structured graphics and ZUIs, which uses a scene graph model with cameras for navigation and supports efficient event handling across scales.[20] Its predecessor, Jazz, an extensible Java toolkit from the late 1990s, introduced polylithic architecture for customizable 2D scene graphs tailored to ZUI applications.[29] For web-based ZUIs, D3.js provides the d3-zoom module, which enables panning and zooming on SVG, HTML, or Canvas elements through affine transformations, integrating seamlessly with data visualization primitives.[30] Modern JavaScript libraries like Zumly, emerging in the 2010s, offer ZUI support via an infinite canvas metaphor, with customizable zoom transitions on web standards.[31] Performance optimizations in these frameworks often involve culling off-screen elements using bounds management to avoid unnecessary rendering and multi-resolution tiling, such as pyramid structures for images, to load only relevant detail levels during zooms.[20] Piccolo2D, for instance, employs efficient repainting and picking algorithms to handle large hierarchies without degradation.[20] Cross-platform challenges arise from adapting ZUI implementations between desktop environments like Qt or Windows Presentation Foundation (WPF) and web technologies such as the Canvas API or WebGL. Desktop frameworks like Piccolo2D.NET leverage GDI+ for Windows-specific rendering, while Java variants ensure broader compatibility, but porting requires handling divergent input and graphics APIs.[20] In contrast, web frameworks like D3.js achieve cross-browser support through standardized DOM manipulations, though they face limitations in native performance compared to desktop engines.[30] WPF supports zooming via controls like Viewbox for scalable layouts, but integrating full ZUI hierarchies demands custom scene graph extensions.[32]Notable Examples

One prominent desktop example of a zooming user interface (ZUI) is Adobe's Dynamic Media Classic, formerly known as Scene7, which provided zoomable image viewers for e-commerce and media applications starting in the 2000s. This platform enables users to interactively zoom into high-resolution images using mouse or touch gestures, such as double-tapping to magnify or pinching to adjust scale, while maintaining contextual navigation across image sets via swatches. Acquired by Adobe in 2011, Scene7's viewers supported fixed-size, responsive, and pop-up embedding modes, facilitating seamless detail exploration without page reloads.[33] Another desktop implementation is the Infinite Canvas feature in Autodesk SketchBook, a digital drawing application that allows artists to pan and zoom freely across an unbounded workspace. Introduced in updates during the 2010s, this ZUI-like system supports continuous zooming from broad overviews to fine details, enabling users to expand their canvas dynamically with pinch gestures or keyboard shortcuts, ideal for iterative sketching and layout design.[34] In web-based contexts, Prezi, launched in 2009, exemplifies a ZUI for dynamic presentations, where users navigate non-linear content via zooming and panning on a single infinite canvas rather than sequential slides. This approach integrates semantic zooming to reveal layered details, such as expanding thumbnails into full visuals, and has been used in over 460 million presentations worldwide.[35][36] OpenStreetMap viewers also demonstrate web-based ZUIs through their slippy map interface, which uses tile-based rendering to enable smooth zooming across 19+ levels, from global overviews to street-level details. Launched in 2004, this system loads 256x256 pixel PNG tiles dynamically via JavaScript libraries like Leaflet, allowing panning and zoom adjustments without disrupting the map's continuity.[37] On mobile platforms, the iOS Photos app incorporates partial ZUI elements, particularly since iOS 14 in 2020, where users can infinitely zoom into images and galleries using pinch gestures, transitioning from thumbnails to full-resolution views while preserving navigational context. This feature supports cropping for further magnification and integrates with the app's library for seamless exploration of photo collections.[38] Early 2000s experiments extended ZUIs to PDAs for medical data visualization, such as interfaces tested on devices like the HP iPAQ for pharmaceutical analysis and patient information retrieval. These prototypes, including starfield displays with semantic zooming, allowed doctors to pan and zoom through datasets like drug interactions or timelines, improving mobility in clinical settings despite small screen constraints. Frameworks like Piccolo were occasionally referenced in such builds.[21] A hybrid example is Google Earth, released in 2005, which blends 2D/3D ZUI navigation with globe rotation for geospatial exploration. Users zoom from orbital views to street-level imagery using mouse wheels or gestures, combining continuous scaling with rotational panning to access satellite data and terrain models.[39]Applications

Information Visualization

Zooming user interfaces (ZUIs) play a pivotal role in information visualization by enabling seamless navigation through complex datasets, allowing users to transition fluidly from high-level overviews to detailed inspections without losing contextual awareness.[40] This approach aligns with Ben Shneiderman's visual information-seeking mantra of "overview first, zoom and filter, then details-on-demand," which has become a foundational principle for designing effective visualization tools.[41] In ZUIs, zooming facilitates the exploration of spatialized information, where data points are arranged in a continuous canvas that reveals patterns at varying scales. In data exploration tasks, ZUIs support drilling down into structures such as graphs, trees, or networks by leveraging zoom operations to uncover hierarchical or relational details. For instance, in social network visualization, tools like Vizster employ panning and zooming to navigate large online communities, enabling users to identify clusters and connections in datasets representing millions of relationships.[42] Similarly, for genomic data, the Integrated Genome Browser (IGB) implements animated semantic zooming to explore sequence alignments and annotations, allowing researchers to zoom into specific chromosomal regions while maintaining an overview of the entire genome.[43] These capabilities are particularly valuable for multivariate datasets, where spatial layouts position elements to encode multiple attributes, and zooming exposes hidden correlations—such as co-expression patterns in gene networks—that are obscured in aggregated views.[44] Key techniques in ZUI-based information visualization include semantic zooming, which dynamically adjusts content detail based on zoom level, integrated with spatial layouts for multivariate data. In these layouts, data dimensions are mapped to positions, sizes, or colors on an infinite canvas, where zooming reveals finer-grained attributes like edge weights in network graphs or variable interactions in scatterplot matrices.[40] Academic case studies, such as zoomable treemaps (ZTMs), extend traditional treemaps by incorporating ZUI paradigms to navigate hierarchical datasets efficiently; for example, ZTMs allow users to zoom into subtrees representing file systems or organizational structures, supporting structure-aware navigation techniques like fisheye views during panning.[45] Commercially, business intelligence dashboards like TIBCO Spotfire integrate zooming sliders and marking-based zoom to explore multivariate analytics, such as sales trends or customer segments, in interactive visualizations that scale to enterprise-level data volumes.[46] For analysts, ZUIs in information visualization offer significant benefits, including the reduction of cognitive load by minimizing the need for multiple linked views or window management, thus fostering serendipitous discoveries during exploration.[44] By maintaining a single, cohesive spatial context, these interfaces enable iterative zooming and filtering that can reveal unexpected insights, such as emergent patterns in network communities or outliers in genomic sequences, enhancing analytical productivity in data-intensive fields.[40]Mobile and Web Interfaces

Zooming user interfaces (ZUIs) have evolved from experimental implementations on personal digital assistants (PDAs) in the early 2000s to integrated elements in responsive web and mobile design post-2010. Early PDA adaptations, such as the Pocket PhotoMesa browser introduced in 2004, utilized zooming for photo navigation on constrained screens around 300x300 pixels, leveraging frameworks like Pad++ from the 1990s to enable semantic and geometric scaling.[21] By the 2010s, the rise of touch-enabled devices and responsive web principles incorporated ZUI elements, allowing seamless scaling across desktops, tablets, and smartphones without fixed page breaks, as seen in multi-device browsing paradigms.[47] In mobile environments, ZUIs rely heavily on gesture-based interactions to accommodate small screens, particularly in mapping applications and photo editors. Pinch-to-zoom and multi-touch panning, standard since the iPhone's introduction in 2007, enable users to fluidly explore large datasets like city maps in tools such as Google Maps. Speed-dependent automatic zooming (SDAZ) is a technique that couples panning with scale changes for efficient navigation.[21] Photo editors like Pocket PhotoMesa employ tap-and-hold gestures (with a 150ms delay) to initiate zooming into image collections, preserving context through focus+context techniques.[21] However, these implementations face challenges including precision demands on touch interfaces, which increase cognitive load and orientation difficulties during rapid scaling, and performance constraints from rendering high-zoom levels on resource-limited devices, potentially straining processing without dedicated hardware acceleration.[21] Web applications adapt ZUIs through infinite canvases that combine scrolling with zooming, enhancing e-commerce experiences in product galleries. Users can pan across expansive layouts and zoom into item details, as in dynamic product views that reveal textures or variants without page reloads, improving immersion over traditional thumbnails.[47] Dynamic infographics further leverage this by allowing zooming and panning to disclose layered data, such as in interactive charts where users adjust scale to focus on specific metrics, aligning with progressive disclosure principles in responsive designs.[48] Notable examples include Figma's collaborative canvas, launched in the 2010s, which supports infinite panning and continuous zooming (via keyboard shortcuts or trackpad gestures) for design workflows, enabling teams to navigate vast prototypes fluidly.[49] Similarly, mapping apps like Google Maps integrate ZUI for mobile web access, supporting gesture-based interactions to mitigate fatigue on touchscreens.[21] These adaptations highlight ZUIs' shift toward touch-optimized, cross-platform utility while addressing legacy web constraints through hybrid navigation models.[47]Advantages and Limitations

Benefits

Zooming user interfaces (ZUIs) provide enhanced context awareness by enabling seamless transitions from overview to detailed views, which reduces user disorientation compared to traditional paginated or scrolling interfaces. This approach leverages human spatial perception and memory, allowing users to build a mental map of the information space as they navigate through panning and zooming operations.[50] Animated transitions further support this by providing pre-conscious understanding of spatial relationships, thereby lowering short-term memory demands during exploration.[50] ZUIs demonstrate strong scalability for large datasets through the use of level-of-detail (LOD) techniques, which adjust rendering quality based on zoom level to maintain performance without degradation. In systems like Pad++, LOD culls small or off-screen objects and employs low-resolution approximations during animations, achieving frame rates of at least 10 frames per second even with up to 20,000 objects.[1] This adaptive rendering ensures smooth interaction for infinite or expansive information spaces, such as document hierarchies or image collections, by prioritizing visible content and refining details only when stationary.[1] Improved user engagement in ZUIs arises from fluid animations and spatial metaphors that make navigation more intuitive and visually compelling. These elements capitalize on human visual perception, drawing attention through smooth "visual flow" and fostering a sense of immersion in the information landscape.[50] Usability studies confirm these gains, showing that animations in ZUIs can reduce reading errors by up to 54% and task completion times by 3% to 24% for activities like counting or reading, depending on animation duration.[50] Users also report better recall of content structure, enhancing overall interaction satisfaction.[50] ZUIs offer accessibility benefits particularly for spatial thinkers and users of large-screen or touch-enabled devices, as the continuous spatial model aligns with natural navigation intuitions. Multi-touch gestures, such as pinch-to-zoom, are straightforward to learn and operate, facilitating inclusive interaction without complex controls.[50] This design supports diverse cognitive styles by emphasizing visual and gestural continuity over discrete page flips, making information exploration more approachable on varied hardware.[50]Challenges and Criticisms

Early implementations of zooming user interfaces (ZUIs) faced significant performance challenges due to the high computational demands of rendering vast information spaces at multiple scales, particularly on mid-1990s hardware. Implementing efficient rendering for elements like text and images requires optimized techniques, such as font caching and spatial indexing, to maintain interactive frame rates; without these, systems like Pad++ achieved only 2.7 frames per second for text rendering, compared to 15 frames per second with caching. On low-end devices of the era, these demands exacerbated issues, as dynamic layout adjustments and scene graph maintenance strained limited resources, leading to slower interactions and reduced usability in resource-constrained environments like early mobile devices.[1] Advancements in GPU technologies and web standards like WebGL and WebGPU have since improved performance on modern devices.[51] Users accustomed to traditional hierarchical or linear interfaces often encountered a steep learning curve with ZUIs, as the paradigm lacks familiar navigational anchors such as persistent menus or fixed hierarchies, requiring reliance on spatial memory for orientation. Discovery of zoom controls—such as double-clicking or scroll wheel gestures—proves particularly challenging, with studies showing that even experienced users struggle to identify and utilize them efficiently, contributing to initial frustration and slower task completion. This cognitive load is heightened by inconsistent implementations across applications, demanding additional training to master non-linear panning and zooming behaviors. Design pitfalls in ZUIs frequently result in navigation difficulties, including the "lost in space" problem, where users become disoriented in expansive, multiscale environments without clear landmarks, leading to inefficient exploration and higher error rates. A related issue is "desert fog," where zooming into empty areas between objects removes contextual cues, severely impairing multiscale navigation and spatial awareness; human-computer interaction surveys highlight these limits in focus+context techniques, noting that abrupt transitions and lack of orienting features increase reorientation time and cognitive strain. Over-reliance on zoom can thus trap users in vast white spaces, undermining the interface's exploratory potential. Early adoption of ZUIs was hindered by technical barriers, including limited browser support for essential features like scalable vector graphics and canvas rendering prior to the 2010s, which restricted web-based implementations to rudimentary or plugin-dependent solutions. Accessibility remains a critical hurdle, particularly for visually impaired users, as screen readers struggle with the dynamic, spatial nature of ZUI content, making it difficult to linearly traverse or comprehend zoomed layouts without specialized adaptations. These factors historically confined ZUIs to niche applications, though as of 2025, ZUI principles are widely incorporated in mainstream tools such as collaborative platforms like Figma and Miro.[52][53] Recent developments, including GPU-accelerated rendering and integration with AR/VR, continue to address remaining challenges.[54]Current Research and Future Directions

Ongoing Developments

Recent research has explored user-adaptive visualizations using machine learning techniques to infer user characteristics and tailor content dynamically. Extensions of ZUIs to virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) environments have advanced 3D interactions in immersive settings. For example, the Marvis framework combines mobile devices and head-mounted AR for visual data analysis, enabling ZUI-like navigation in spatial data.[55] Studies continue to evaluate zooming techniques in VR for spatial data visualization, comparing them to overview+detail methods to enhance navigation and comprehension. Furthermore, spatial computing platforms like Apple Vision Pro, introduced in 2023, support 3D ZUI-like experiences by blending digital content with physical spaces through eye, hand, and voice controls for immersive 3D manipulation.[56] Standardization efforts for zoomable web interfaces continue through W3C specifications, particularly SVG, which provides built-in support for scalable vector graphics with zooming and panning capabilities to ensure consistent interactive experiences across browsers.[57] Open-source frameworks like Piccolo2D remain available for ZUI development, with its Java and .NET versions hosted on GitHub for structured 2D graphics applications.[58] Empirical studies at recent CHI conferences have assessed ZUIs in contexts relevant to remote collaboration, such as visualization tools that facilitate shared editing and navigation.Emerging Trends

Recent advancements in zooming user interfaces (ZUIs) are exploring multimodal integration, combining visual zooming with voice commands, haptic feedback, and eye-tracking to facilitate hands-free navigation. For example, the HeadZoom framework, introduced in 2025, uses head movements to control zooming and panning in 2D interfaces, which can be augmented with eye-tracking for precise targeting and voice for semantic queries, enhancing accessibility in constrained environments.[59] In metaverse applications, ZUIs enable seamless exploration of infinite virtual worlds within VR social platforms, particularly for virtual real estate navigation. Events like Imagine the Metaverse 2024 showcased immersive technologies for interacting with virtual venues and performances, allowing dynamic scaling of views from broad landscapes to fine details without traditional menus. This approach supports navigable spaces that mimic physical exploration. Sustainability efforts in HCI focus on optimization for edge computing, aiming to minimize energy consumption in mobile and IoT devices through efficient rendering and local processing. This aligns with broader pushes for energy-efficient interfaces in wearable and embedded systems. Broader adoption of ZUIs is occurring in education and e-learning through immersive and interactive platforms. Tools like Prezi, leveraging ZUI for dynamic presentations, support student engagement in subjects such as physics.References

- https://wiki.openstreetmap.org/wiki/Slippy_map