Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Air handler

View on Wikipedia

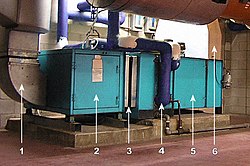

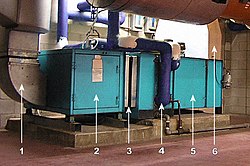

1 – Supply duct

2 – Fan compartment

3 – Vibration isolator ('flex joint')

4 – Heating and/or cooling coil

5 – Filter compartment

6 – Mixed (recirculated + outside) air duct

An air handler, or air handling unit (often abbreviated to AHU), is a device used to regulate and circulate air as part of a heating, ventilating, and air-conditioning (HVAC) system.[1] An air handler is usually a large metal box containing a blower, furnace or A/C elements, filter racks or chambers, sound attenuators, and dampers.[2] Air handlers usually connect to a ductwork ventilation system that distributes the conditioned air through the building and returns it to the AHU, sometimes exhausting air to the atmosphere and bringing in fresh air.[3] Sometimes AHUs discharge (supply) and admit (return) air directly to and from the space served without ductwork[4]

Small air handlers, for local use, are called terminal units, and may only include an air filter, coil, and blower; these simple terminal units are called blower coils or fan coil units. A larger air handler that conditions 100% outside air, and no recirculated air, is known as a makeup air unit (MAU) or fresh air handling unit (FAHU). An air handler designed for outdoor use, typically on roofs, is known as a packaged unit (PU), heating and air conditioning unit (HCU), or rooftop unit (RTU).

Construction

[edit]The air handler is normally constructed around a framing system with metal infill panels as required to suit the configuration of the components. In its simplest form the frame may be made from metal channels or sections, with single skin metal infill panels. The metalwork is normally galvanized for long term protection. For outdoor units some form of weatherproof lid and additional sealing around joints is provided.[2]

Larger air handlers will be manufactured from a square section steel framing system with double skinned and insulated infill panels. Such constructions reduce heat loss or heat gain from the air handler, as well as providing acoustic attenuation.[2] Larger air handlers may be several meters long and are manufactured in a sectional manner and therefore, for strength and rigidity, steel section base rails are provided under the unit.[2]

Where supply and extract air is required in equal proportions for a balanced ventilation system, it is common for the supply and extract air handlers to be joined together, either in a side-by-side or a stacked configuration.

Air handling units types

[edit]There are six factors for air handlers classifications and determine types of them, based on:

- Application (air handling unit usage)

- Air flow control (CAV or VAV air handlers)

- Zone control (single zone or multi zone air handlers)

- Fan location (draw-through or blow-through)

- Direction of outlet air flow (front, up, or down)

- Package model (horizontal or vertical)

But, the first method is very usual in HVAC market. In fact, most of the company advertise their products by air handling unit applications:

- Normal

- Hygienic

- Ceiling mounted

Components

[edit]The major types of components are described here in approximate order, from the return duct (input to the AHU), through the unit, to the supply duct (AHU output).[1][2]

Filters

[edit]

Air filtration is almost always present in order to provide clean dust-free air to the building occupants. It may be via simple low-MERV pleated media, HEPA, electrostatic, or a combination of techniques. Gas-phase and ultraviolet air treatments may be employed as well.

Filtration is typically placed first in the AHU in order to keep all the downstream components clean. Depending upon the grade of filtration required, typically filters will be arranged in two (or more) successive banks with a coarse-grade panel filter provided in front of a fine-grade bag filter, or other "final" filtration medium. The panel filter is cheaper to replace and maintain, and thus protects the more expensive bag filters.[1]

The life of a filter may be assessed by monitoring the pressure drop through the filter medium at design air volume flow rate. This may be done by means of a visual display using a pressure gauge, or by a pressure switch linked to an alarm point on the building control system. Failure to replace a filter may eventually lead to its collapse, as the forces exerted upon it by the fan overcome its inherent strength, resulting in collapse and thus contamination of the air handler and downstream ductwork.

Hot (heat A.K.A furnace) and cold (air conditioning) elements

[edit]Air handlers may need to provide hot air, cold air, or both to change the supply air temperature, and humidity level depending on the location and the application. Such conditioning is provided by heat exchanger coils within the air handling unit air stream, such coils may be direct or indirect in relation to the medium providing the heating or cooling effect.[1][2]

Direct heat exchangers include those for gas-fired fuel-burning heaters or a refrigeration evaporator, placed directly in the air stream. Electric resistance heaters and heat pumps can be used as well. Evaporative cooling is possible in dry climates.

Indirect coils use hot water or steam for heating, and chilled water or glycol for cooling (prime energy for heating and air conditioning is provided by central plant elsewhere in the building). Coils are typically manufactured from copper for the tubes, with copper or aluminum fins to aid heat transfer. Cooling coils will also employ eliminator plates to remove and drain condensate. The hot water or steam is provided by a central boiler, and the chilled water is provided by a central chiller. Downstream temperature sensors are typically used to monitor and control "off coil" temperatures, in conjunction with an appropriate motorized control valve prior to the coil.

If dehumidification is required, then the cooling coil is employed to over-cool so that the dew point is reached and condensation occurs. A heater coil placed after the cooling coil re-heats the air (therefore known as a re-heat coil) to the desired supply temperature. This process has the effect of reducing the relative humidity level of the supply air.

In colder climates, where winter temperatures regularly drop below freezing, then frost coils or pre-heat coils are often employed as a first stage of air treatment to ensure that downstream filters or chilled water coils are protected against freezing. The control of the frost coil is such that if a certain off-coil air temperature is not reached then the entire air handler is shut down for protection.

Humidifier

[edit]Humidification is often necessary in colder climates where continuous heating will make the air drier, resulting in uncomfortable air quality and increased static electricity. Various types of humidification may be used:

- Evaporative: dry air blown over a reservoir will evaporate some of the water. The rate of evaporation can be increased by spraying the water onto baffles in the air stream.

- Vaporizer: steam or vapor from a boiler is blown directly into the air stream.

- Spray mist: water is diffused either by a nozzle or other mechanical means into fine droplets and carried by the air.

- Ultrasonic: A tray of fresh water in the airstream is excited by an ultrasonic device forming a fog or water mist.

- Wetted medium: A fine fibrous medium in the airstream is kept moist with fresh water from a header pipe with a series of small outlets. As the air passes through the medium it entrains the water in fine droplets. This type of humidifier can quickly clog if the primary air filtration is not maintained in good order.

Mixing chamber

[edit]In order to maintain indoor air quality, air handlers commonly have provisions to allow the introduction of outside air into, and the exhausting of air from the building. In temperate climates, mixing the right amount of cooler outside air with warmer return air can be used to approach the desired supply air temperature. A mixing chamber is therefore used which has dampers controlling the ratio between the return, outside, and exhaust air.

Blower/fan

[edit]Air handlers typically employ a large squirrel cage blower driven by an AC induction electric motor to move the air. The blower may operate at a single speed, offer a variety of set speeds, or be driven by a variable-frequency drive to allow a wide range of air flow rates. Flow rate may also be controlled by inlet vanes or outlet dampers on the fan. Some residential air handlers in USA (central "furnaces" or "air conditioners") use a brushless DC electric motor that has variable speed capabilities.[1] Air handlers in Europe and Australia and New Zealand now commonly use backward curve fans without scroll or "plug fans". These are driven using high efficiency EC (electronically commutated) motors with built in speed control. The higher the RTU temperature, the slower the air will flow. And the lower the RTU temperature, the faster the air will flow.

Multiple blowers may be present in large commercial air handling units, typically placed at the end of the AHU and the beginning of the supply ductwork (therefore also called "supply fans"). They are often augmented by fans in the return air duct ("return fans") pushing the air into the AHU.

Balancing

[edit]Un-balanced fans wobble and vibrate. For home AC fans, this can be a major problem: air circulation is greatly reduced at the vents (as wobble is lost energy), efficiency is compromised, and noise is increased. Another major problem in fans that are not balanced is longevity of the bearings (attached to the fan and shaft) is compromised. This can cause failure to occur long before the bearings life expectancy.

Weights can be strategically placed to correct for a smooth spin (for a ceiling fan, trial and error placement typically resolves the problem). Home/central AC fans or other big fans are typically taken to shops, which have special balancers for more complicated balancing (trial and error can cause damage before the correct points are found). The fan motor itself does not typically vibrate.

Heat recovery device

[edit]A heat recovery device heat exchanger may be fitted to the air handler between supply and extract airstreams for energy savings and increasing capacity. These types more commonly include for:

- Recuperator, or Plate Heat exchanger: A sandwich of plastic or metal plates with interlaced air paths. Heat is transferred between airstreams from one side of the plate to the other. The plates are typically spaced at 4 to 6mm apart. Heat recovery efficiency up to 70%.

- Thermal wheel, or Rotary heat exchanger: A slowly rotating matrix of finely corrugated metal, operating in both opposing airstreams. When the air handling unit is in heating mode, heat is absorbed as air passes through the matrix in the exhaust airstream, during one half rotation, and released during the second half rotation into the supply airstream in a continuous process. When the air handling unit is in cooling mode, heat is released as air passes through the matrix in the exhaust airstream, during one half rotation, and absorbed during the second half rotation into the supply airstream. Heat recovery efficiency up to 85%. Wheels are also available with a hygroscopic coating to provide latent heat transfer and also the drying or humidification of airstreams.

- Run around coil: Two air to liquid heat exchanger coils, in opposing airstreams, piped together with a circulating pump and using water or a brine as the heat transfer medium. This device, although not very efficient, allows heat recovery between remote and sometimes multiple supply and exhaust airstreams. Heat recovery efficiency up to 50%.

- Heat pipe: Operating in both opposing air paths, using a confined refrigerant as a heat transfer medium. The heat pipe uses multiple sealed pipes mounted in a coil configuration with fins to increase heat transfer. Heat is absorbed on one side of the pipe, by evaporation of the refrigerant, and released at the other side, by condensation of the refrigerant. Condensed refrigerant flows by gravity to the first side of the pipe to repeat the process. Heat recovery efficiency up to 65%.

Controls

[edit]Controls are necessary to regulate every aspect of an air handler, such as: flow rate of air, supply air temperature, mixed air temperature, humidity, air quality. They may be as simple as an off/on thermostat or as complex as a building automation system using BACnet or LonWorks, for example.

Common control components include temperature sensors, humidity sensors, sail switches, actuators, motors, and controllers.

Vibration isolators

[edit]The blowers in an air handler can create substantial vibration and the large area of the duct system would transmit this noise and vibration to the occupants of the building. To avoid this, vibration isolators (flexible sections) are normally inserted into the duct immediately before and after the air handler and often also between the fan compartment and the rest of the AHU. The rubberized canvas-like material of these sections allows the air handler components to vibrate without transmitting this motion to the attached ducts.

The fan compartment can be further isolated by placing it on spring suspension, neoprene pads, or hung on spring hangers, which will mitigate the transfer of vibration through the structure.

Sound attenuators

[edit]The blower in the air handler also generates noise, which should be attenuated before ductwork enters a noise-sensitive room. To achieve meaningful noise reduction in a relatively short length, a sound attenuator is used.[1] The attenuator is a specialty duct accessory that typically consists of an inner perforated baffle with sound-absorptive insulation. Sound attenuators may take the place of ductwork; conversely, inline attenuators are located close to the blower and have a bellmouth profile to minimize system effects.

Major manufacturers

[edit]- AAON

- Carrier Corporation (also makes Bryant and Payne brands)

- CIAT Group

- Daikin Industries (also makes McQuay International, Goodman, and Airfel brands)

- Johnson Controls (also makes York International brand)

- Lennox International

- Rheem (also makes Ruud)

- Trane

- Vertiv

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f 2008 ASHRAE handbook : heating, ventilating, and air-conditioning systems and equipment (Inch-Pound ed.). Atlanta, Ga.: ASHRAE American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers. 2008. ISBN 9781933742335.

- ^ a b c d e f Carrier Design Manual part 2: Air Distribution (1974 tenth ed.). Carrier Corporation. 1960.

- ^ "Air Handling Units Explained". The Engineering Mindset. 26 September 2018.

- ^ HVAC, experts. "how air handling unit work?".

Air handler

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and Purpose

An air handler is a fundamental device in heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems that conditions and circulates air by drawing in indoor or outdoor air, filtering it to remove contaminants, modifying its temperature through heating or cooling, adjusting humidity levels via humidification or dehumidification, and distributing the conditioned air through a network of ductwork to various spaces.[3][4] Typically positioned indoors, such as in attics, basements, or closets, the air handler serves as the primary mechanism for air movement and treatment within residential, commercial, and industrial buildings.[5] The core purposes of an air handler encompass ventilation by introducing fresh outdoor air to dilute indoor pollutants, temperature control to maintain occupant comfort through precise heating or cooling, humidity regulation to prevent issues like mold growth or excessive dryness, and improvement of indoor air quality via filtration and purification processes that capture particulates, allergens, and pathogens.[6] These functions collectively ensure a healthy and comfortable indoor environment while supporting energy efficiency in broader HVAC operations.[7] In its basic operational cycle, an air handler intakes return air from the building and mixes it with fresh outdoor air if needed, conditions the blend through integrated processes, and uses a fan or blower to distribute the treated air via supply ducts, while facilitating the return of used air for recirculation or exhaust.[4][8] Performance is quantified by airflow capacity in cubic feet per minute (CFM), which measures the volume of air circulated, and tonnage, representing cooling or heating capacity where one ton equates to 12,000 British thermal units per hour (BTU/h) of heat removal, with a standard guideline of approximately 400 CFM per ton for efficient operation.[9][10] Air handlers emerged in the early 20th century as integral components of modern HVAC evolution, with pioneering developments including Willis Carrier's 1902 air conditioning system for humidity control and the 1907 invention of the unit ventilator, an early prototype featuring a fan and radiator for localized air treatment.[11]Role in HVAC Systems

Air handlers serve as a central component in heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems, integrating with ductwork to distribute conditioned air throughout buildings for uniform temperature control and ventilation. They connect to external sources such as chillers for cooling via chilled water coils or boilers for heating through hot water or steam coils, enabling efficient temperature exchange without housing the primary generation equipment. Additionally, air handlers incorporate economizers that utilize outdoor air for "free cooling" when conditions permit, reducing reliance on mechanical refrigeration and lowering overall system energy demands.[12][13][14] In various HVAC configurations, air handlers function as the core unit for air distribution and conditioning. In all-air systems, they handle the full load of heating, cooling, and ventilation by processing and supplying conditioned air directly through ducts to zones, providing comprehensive control over indoor environments. Air-water systems, by contrast, use air handlers primarily for fresh air introduction and circulation, while local fan coil units manage zone-specific temperature adjustments using water from central plants, allowing for hybrid efficiency in diverse building layouts. As part of variable air volume (VAV) setups, air handlers modulate airflow and temperature based on demand from multiple zones, optimizing delivery to prevent over-conditioning unoccupied areas.[15][16] Air handlers act as the dynamic "lungs" of HVAC systems, facilitating air circulation that manages a substantial portion of a building's thermal energy load, with fan operations often accounting for 20-30% of total HVAC energy consumption in commercial structures.[17] This circulation supports the transfer of heating or cooling energy, contributing to overall building comfort while influencing system-wide efficiency. Through features like zoning and modulation—enabled by VAV integration—air handlers reduce unnecessary energy use by adjusting supply volumes, potentially cutting fan power by up to 50% during low-demand periods. As of 2025, integrated HVAC systems incorporating air handlers typically achieve SEER2 ratings ranging from 14 to 25, reflecting their role in enhancing cooling performance over seasonal variations, with minimums of 14 SEER2 in northern U.S. regions and 15 SEER2 in southern regions per DOE regulations.[18] As of 2025, new air handlers in split systems must incorporate evaporator coils compatible with low global warming potential (GWP) refrigerants such as R-32 or R-454B, following the EPA's phase-down of R-410A to reduce climate impacts.[19]Design and Construction

Materials and Assembly

Air handlers are typically constructed using durable materials that ensure longevity, corrosion resistance, and efficient thermal performance. The casings are commonly made from galvanized steel, which provides a protective zinc coating to prevent rust and degradation in humid environments. [20] Insulated panels, often filled with polyurethane foam, are integrated into the structure to minimize heat loss or gain, offering R-values ranging from 6 to 13 depending on thickness and foam density. [21] Aluminum is frequently used for heat exchanger coils due to its lightweight properties and superior thermal conductivity, facilitating effective heat transfer without excessive weight. [22] In corrosive environments, such as coastal areas or chemical processing facilities, stainless steel or fiberglass-reinforced casings may be used for enhanced resistance.[23] Assembly of air handlers emphasizes modular design for flexibility and maintenance ease. Frames are often welded for structural integrity, while panels are secured with bolts to allow quick access for servicing internal components. Double-wall constructions are standard, featuring an outer metal skin and an inner liner separated by insulation, which helps prevent condensation buildup and reduces the risk of microbial proliferation within the unit. [24] To meet hygiene requirements, materials in air handlers must comply with standards such as ASHRAE 62.1, which mandates resistance to mold growth through standardized testing methods like the Mold Growth and Humidity Test. Indoor units often incorporate protective coatings, such as epoxy, applied to surfaces to inhibit mold and bacterial adhesion, enhancing indoor air quality. [25] Air handlers vary significantly in size to accommodate different applications; for example, compact residential units rated around 600 CFM typically measure about 18 inches wide by 45 inches high, while large industrial models can handle up to 100,000 CFM and exceed 15 feet in length. [26] [27] Recent trends post-2020 highlight sustainability in air handler construction, including the use of recycled steel for casings to reduce environmental impact, as steel is nearly 100% recyclable. [28] Additionally, the integration of low global warming potential (GWP) refrigerants in associated coils aligns with regulatory shifts like the AIM Act, promoting lower emissions without compromising performance. [29]Sizing and Capacity Considerations

Sizing an air handler involves evaluating key environmental and structural factors to ensure it meets the heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) demands of a building without excess or deficiency. Primary considerations include the building's volume, which determines the overall space requiring conditioned air; the climate zone, influencing external temperature extremes and humidity levels; occupancy load, accounting for heat generated by people and equipment; and precise heat gain or loss calculations. These calculations typically follow established methods such as the Air Conditioning Contractors of America (ACCA) Manual J, which integrates factors like insulation, window orientations, and infiltration to compute peak loads for residential applications.[30] For commercial buildings, the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) Load Calculation Applications Manual provides detailed heat balance and radiant time series approaches, incorporating similar inputs to estimate sensible and latent loads. Manual J, recognized as the ANSI standard in its 8th edition, emphasizes accurate inputs for these factors to avoid common errors in load estimation.[31] Capacity metrics for air handlers focus on airflow, pressure handling, and power requirements to match system performance. Airflow is commonly rated in cubic feet per minute (CFM), with a standard guideline of approximately 400 CFM per ton of cooling capacity to achieve efficient heat transfer in typical systems. Static pressure, measured in inches of water gauge (in. wg.), indicates the resistance the fan must overcome in ductwork and components, typically ranging from 0.5 to 2 in. wg. depending on system complexity and design. Fan horsepower varies widely by application, from 1 HP for small residential units to 50 HP or more for large commercial installations, selected based on required CFM and static pressure curves. A fundamental equation for sensible heat load in air handlers is: where represents the sensible heat in British thermal units per hour (BTU/hr), CFM is the airflow rate, and is the temperature difference in degrees Fahrenheit between supply and return air. This formula derives from the product of air's specific heat (0.24 BTU/lb·°F), density (approximately 0.075 lb/ft³ at standard conditions), and the conversion factor for units (60 minutes/hour), yielding the constant 1.08 for practical HVAC calculations.[32] It applies directly to sizing by linking airflow needs to calculated loads from Manual J or ASHRAE methods.[33] Improper sizing carries significant risks that compromise system efficiency and occupant comfort. Oversizing an air handler can lead to short cycling, where the unit frequently starts and stops, reducing dehumidification effectiveness and causing high indoor humidity levels, uneven temperatures, and increased energy consumption. Undersizing results in prolonged runtime to meet demands, leading to inadequate temperature control, discomfort, and potential overheating of components like the compressor. Both issues shorten equipment lifespan and elevate operational costs.[34][35] Modern software tools enhance precision in air handler sizing by simulating hourly loads and integrating contemporary energy standards. The Carrier Hourly Analysis Program (HAP) performs comprehensive load calculations, system sizing, and annual energy modeling for commercial HVAC designs, incorporating variables like climate data and occupancy to align with codes such as the International Energy Conservation Code (IECC). Recent IECC editions from the 2020s emphasize right-sizing to meet minimum efficiency requirements, with HAP's updates supporting compliance through detailed reporting of peak loads and energy use.[36]Types of Air Handlers

Centralized vs. Decentralized Units

Centralized air handlers are large-scale systems designed to condition and distribute air throughout an entire building using a single primary unit connected to extensive ductwork. This configuration allows for uniform temperature and humidity control across multiple zones, leveraging economies of scale in operation and maintenance for larger structures. However, the high initial installation costs associated with ducting and the potential for single-point failure, where a malfunction affects the whole building, are notable drawbacks.[37] In contrast, decentralized air handlers consist of multiple smaller units, such as fan coil units (FCUs), installed in individual zones or rooms to provide localized conditioning without relying on central ductwork. These systems offer greater flexibility for retrofitting existing buildings and independent control per space, enabling energy savings in partially occupied areas. Drawbacks include the need for redundancy across units to avoid localized failures and challenges in uniform maintenance due to dispersed locations. Examples of decentralized units include FCUs with typical capacities of 400-1,000 CFM per unit, suitable for apartments or small offices.[37][38] Applications of centralized air handlers are prevalent in large commercial buildings like offices and hotels, where capacities often exceed 10,000 CFM to serve expansive areas efficiently. Decentralized units, by comparison, are more common in residential or multi-family settings, such as apartments, with per-unit capacities in the 400-1,000 CFM range to address variable loads in individual spaces.[39][38] Efficiency comparisons highlight centralized systems' advantage in energy use, with significantly higher efficiency through lower kW/ton ratios of 0.5-0.7 for centralized chillers compared to 1.0-1.3 for decentralized units, enabled by integrated heat recovery mechanisms that capture and reuse exhaust air energy on a building-wide scale. Decentralized systems, while less efficient in aggregate due to the absence of centralized recovery, excel in adapting to variable occupancy and loads, reducing waste in intermittently used zones.[40][37] Post-2015 trends in decentralized air handlers have increasingly incorporated Internet of Things (IoT) integration for smart building applications, enabling real-time monitoring, predictive maintenance, and demand-responsive control to optimize energy use in dynamic environments like multi-tenant facilities. As of 2025, trends continue with AI-enhanced IoT for predictive maintenance and demand-responsive controls in multi-tenant facilities.[41][42]| Aspect | Centralized Air Handlers | Decentralized Air Handlers |

|---|---|---|

| Scale and Distribution | Single unit with ductwork for whole-building (10,000+ CFM) | Multiple units per zone (400-1,000 CFM/unit) |

| Pros | Uniform control, economies of scale, integrated heat recovery | Flexibility, easy retrofits, zone-specific efficiency |

| Cons | High installation cost, single-point failure | Redundancy needs, uneven maintenance |

| Efficiency Edge | Higher via lower kW/ton (0.5-0.7) and central recovery | Suited for variable loads, lower waste in partial use |