Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ballari

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2022) |

Ballari (formerly Bellary[6]) is a city in the Ballari district in state of Karnataka, India.

Key Information

Ballari houses many steel plants such as JSW Vijayanagar, one of the largest in Asia. Ballari district is also known as the ‘Steel city of South India’. Ballari is also the headquarters for Karnataka Gramina Bank which almost has more than 1100 + branches in Karnataka.[7]

History

[edit]

Ballari was a part of Rayalaseema (Ceded Districts) which was part of Madras Presidency till 1 November 1956.

The Ballari city municipal council was upgraded to a city corporation in 2004.[8]

The Union Ministry of Home Affairs of the Government of India approved a proposal[9] to rename the city in October 2014 and Bellary was renamed to "Ballari" on 1 November 2014.[10]

Geography

[edit]

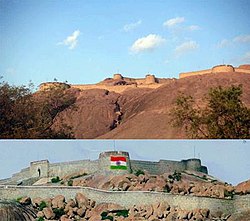

Ballari is located at 15°09′N 76°56′E / 15.15°N 76.93°E. The city stands in the midst of a wide, level plain of black cotton soil.[11]Granite rocks and hills form a prominent feature of Ballari. The city is spread mainly around two hills of granite composition, the Ballari Hill and the Kumbara Gudda.

Ballari Hill has a circumference of nearly 2 miles (3.2 km) and a height of 480 feet (150 m). The length of this rock from north-east to south-west is about 1,150 ft (350 m). To the east and south lies an irregular heap of boulders, to the west there is an unbroken monolith, and the north is walled by bare, rugged ridges.[11]

Kumbara Gudda looks like the profile of a human face from the south-east. It is also known as Face Hill.[11]

Climate

[edit]The climate is a hot semi arid one (BSh), primarily due to the rain shadow effect of the Western Ghats, but monsoons still influence the weather here, with light rain throughout the year, and a slight increase during the summer and autumn.

| Climate data for Bellary (1981–2010, extremes 1901–2012) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 37.6 (99.7) |

40.5 (104.9) |

43.0 (109.4) |

45.4 (113.7) |

44.6 (112.3) |

44.7 (112.5) |

39.5 (103.1) |

39.0 (102.2) |

38.4 (101.1) |

39.0 (102.2) |

38.4 (101.1) |

35.6 (96.1) |

44.7 (112.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 31.4 (88.5) |

34.4 (93.9) |

38.1 (100.6) |

40.4 (104.7) |

39.6 (103.3) |

35.3 (95.5) |

32.7 (90.9) |

31.9 (89.4) |

32.3 (90.1) |

31.8 (89.2) |

30.8 (87.4) |

30.2 (86.4) |

34.1 (93.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 15.6 (60.1) |

18.1 (64.6) |

21.1 (70.0) |

23.9 (75.0) |

24.4 (75.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.0 (73.4) |

22.7 (72.9) |

21.9 (71.4) |

20.9 (69.6) |

18.3 (64.9) |

15.6 (60.1) |

20.7 (69.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 7.0 (44.6) |

8.5 (47.3) |

10.0 (50.0) |

13.0 (55.4) |

14.5 (58.1) |

14.8 (58.6) |

15.5 (59.9) |

15.0 (59.0) |

15.0 (59.0) |

12.5 (54.5) |

8.4 (47.1) |

8.0 (46.4) |

7.0 (44.6) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 2.9 (0.11) |

2.3 (0.09) |

6.0 (0.24) |

17.2 (0.68) |

54.3 (2.14) |

59.2 (2.33) |

42.6 (1.68) |

70.0 (2.76) |

111.0 (4.37) |

89.0 (3.50) |

39.5 (1.56) |

5.5 (0.22) |

499.5 (19.67) |

| Average rainy days | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 1.5 | 3.4 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 4.7 | 5.4 | 5.8 | 2.4 | 0.5 | 32.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 17:30 IST) | 43 | 37 | 30 | 29 | 34 | 50 | 56 | 58 | 58 | 62 | 56 | 50 | 47 |

| Source: India Meteorological Department[12][13] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1931 | 47,573 | — |

| 1941 | 56,148 | +18.0% |

| 1951 | 70,332 | +25.3% |

| 1961 | 85,673 | +21.8% |

| 1971 | 125,183 | +46.1% |

| 1981 | 201,579 | +61.0% |

| 1991 | 245,391 | +21.7% |

| 2001 | 316,766 | +29.1% |

| 2011 | 410,445 | +29.6% |

| Source: [14] | ||

According to the 2011 Census of India, the urban population of Ballari was 410,445; of whom 206,149 were male and 204,296 female. 280,610 of the population were literate and 52,413 of the population were under 7 years of age.[16] The population in 2001 was recorded as 316,766.[17]

Languages

[edit]Kannada is the largest language, spoken by 42.06% of the population. Telugu is the second-largest, spoken by 25.03%, and Urdu 24.35%. 3.04% of the population spoke Hindi, 1.75% Marathi, 1.69% Tamil, 0.85% Marwari and 0.50% Lambadi.[17][18]

Economy

[edit]Industries

[edit]Textiles and garments

[edit]- Cotton processing

- With cotton being one of the major agricultural crops around Ballari historically, the city has had a thriving cotton processing industry in the form of ginning, spinning and weaving plants. The earliest steam cotton-spinning mill was established in 1894, which by 1901 had 17,800 spindles, and employed 520 hands.[11]

- The city continues to thrive in this sector with one spinning mill and numerous cotton ginning and pressing mills, hand looms and power looms.[19]

- Garment manufacture

- Ballari has a historic garment industry dating back to the First World War period, when the Marathi speaking "Darji" (tailor) community with its native skills in tailoring migrated from the current Maharashtra region to stitch uniforms for the soldiers of the colonial British Indian Army stationed at Ballari. After the war, the community switched to making uniforms for school children, and gradually the uniforms made here became popular all over the country.[20][21]

- Currently, Ballari is well known for its branded and unbranded denim garments, with brands like Point Blank, Walker, Dragonfly and Podium being successfully marketed nationally and internationally.[21] There are about 260 denim garment units in Ballari with nearly 3000 families working in these units.[19]

Transport

[edit]

Roadways

[edit]National Highway 67 (India), National Highway 150A (India), State Highway 128 and State Highway 132 pass through the city.

Rail

[edit]There is Ballari Junction railway station on the Guntakal–Vasco da Gama section.

Air

[edit]The closest functional commercial airport is Jindal Vijaynagar Airport.

Education

[edit]Notable people

[edit]See Category:People from Ballari

- Kolur Basavanagoud – Politician, Educationist, and Industrialist. He served as MP in 13th Lok Sabha from Ballari Lok Sabha constituency.

- Basavarajeshwari – Politician and Industrialist

- Ravi Belagere – Actor, writer, novelist, journalist, publisher of the Hai Bengaluru Tabloid

- Naveen Chandra – Actor in Telugu film industry

- Manjula Chellur −1st Woman Chief Justice of Calcutta High Court

- Nagarur Gopinath – One of the pioneers of cardiothoracic surgery in India, credited with the first successful performance of open heart surgery in India in 1962. Recipient of Padma Shri (1974) and Dr. B. C. Roy Award (1978)

- Jayanthi – cinema actress, born in Ballari

- K. C. Kondaiah – Politician and industrialist

- Arcot Ranganatha Mudaliar – Former Deputy Collector of Ballari, politician and theosophist. He served as the Minister of Public Health and Excise for the Madras Presidency from 1926 to 1928.

- A. Sabhapathy Mudaliar – Philanthropist; The Women & Children's Hospital or The District Hospital was initially named after him, following his donation of land and building to the hospital.[11]

- B Nagendra - Youth Welfare and Sports Minister of Karnataka

- Bellary Raghava (1880–1946) – Noted dramatist. The Raghava Kala Mandir auditorium in Ballari is named after him

- Suparna Rajaram – Distinguished Professor of Psychology at Stony Brook University

- Dharmavaram Ramakrishnamacharyulu (1853–1912) – Noted dramatist

- Bhargavi Rao – a Kannada-Telugu translator, winner of the prestigious Kendra Sahitya Academy award

- Kolachalam Srinivasa Rao (1854–1919) – Noted dramatist

- Gali Janardhan Reddy – Former minister and district in charge. He is one of the richest politicians in India

- B Sriramulu - Ex Minister of Health and Family Welfare of Karnataka

- Tekur Subramanyam – Indian Freedom Fighter, First post-independence MP of Ballari, elected thrice in a row since 1952, political secretary to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru[22][23][24]

- Ibrahim B. Syed – Indo-American Radiologist

- Allum Veerabhadrappa - former minister, Government of Karnataka

References

[edit]Maps

[edit]General

[edit]- ^ "Census Data Handbook 2011" (PDF). Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- ^ "Bellary City Staff". Archived from the original on 20 May 2006. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ^ "Indiapost PIN Search for 'bellary'". Archived from the original on 4 May 2007. Retrieved 8 May 2007.

- ^ "50th Report of the Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities in India (July 2012 to June 2013)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ^ a b "District Census Handbook – Guntur" (PDF). Census of India. The Registrar General & Census Commissioner. p. 22. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ^ "Bangalore becomes 'Bengaluru'; 11 other cities renamed". The Economic Times. Bangalore. PTI. 1 November 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ "Ballari District Profile". e-krishiuasb.karnataka.gov.in. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- ^ "Karnataka. Bellary City Municipal Council upgraded to corporation". The Hindu. 26 September 2004. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ "Government of India, Ministry of Home Affairs" (PDF).

- ^ New City, Names to Karnatka. "New name for cities". The Hindu. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d e The Imperial Gazetteer of India, volume 7. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1908. pp. 158–176.

- ^ "Station: Bellary Climatological Table 1981–2010" (PDF). Climatological Normals 1981–2010. India Meteorological Department. January 2015. pp. 119–120. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ "Extremes of Temperature & Rainfall for Indian Stations (Up to 2012)" (PDF). India Meteorological Department. December 2016. p. M90. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ "Census Tables". Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Retrieved 2 October 2023.

- ^ "Table C-01 Population By Religious Community - Karnataka". Census of India.

- ^ "Census of India 2011". Census Commission of India. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ a b "Census of India 2001" (PDF). Census Commission of India. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ a b "C-16 City: Population by mother tongue". Office Of The Registrar General & Census Commissioner India. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ a b "Karnataka Handloom". Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2010.

- ^ "Bellary Portal". Archived from the original on 20 July 2002. Retrieved 23 July 2010.

- ^ a b "Jeans Industry in Bellary". Archived from the original on 22 December 2008. Retrieved 23 July 2010.

- ^ "This jailhouse has a rich past". 26 April 2010. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- ^ "A Congress bastion since 1952". Archived from the original on 26 January 2013. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- ^ "Caste will play a vital role in Bellary". Retrieved 4 June 2010.

External links

[edit]Ballari

View on GrokipediaBallari, formerly Bellary, is a city in eastern Karnataka, India, serving as the administrative headquarters of Ballari district and recognized as the "Steel City of South India" due to its extensive iron ore deposits and steel manufacturing.[1][2] The city spans 81.95 square kilometers and had a population of 410,445 according to the 2011 census, with recent estimates projecting growth to around 560,000 in the metro area by 2023.[3][4] Historically, Ballari's prominence traces to the Vijayanagara Empire, with landmarks like Ballari Fort—built atop granite hills by local chieftains and later fortified under Hyder Ali—symbolizing its strategic past amid regional conflicts.[5] The district, encompassing the city, holds about 25% of India's iron ore reserves, fueling an economy dominated by mining and heavy industry, including major steel plants that contribute significantly to Karnataka's gross domestic district product.[6][1] Despite its industrial growth as the state's second-fastest urbanizing area, Ballari maintains a literacy rate of around 68% and relies on agriculture for pulses, oilseeds, and cotton in surrounding rural zones.[1][7]

History

Prehistoric and Ancient Periods

The Ballari region preserves substantial evidence of Neolithic activity, centered in the Sanganakallu-Kupgal archaeological complex approximately 6 km east of the city. This area includes multiple hilltop settlements, ashmounds formed from cattle dung and ritual fires, and extensive quarry sites exploiting dolerite dykes for stone axe production, with manufacturing commencing around 1900 BCE and reaching its zenith between 1400 and 1200 BCE.[8] The complex spans Mesolithic through Megalithic phases, featuring rock shelters and activity areas that reflect shifts from hunter-gatherer economies to agro-pastoralism, evidenced by ground stone tools, pottery, and faunal remains indicating domesticated cattle herding.[9] Petroglyphs at Kupgal, numbering in the thousands, depict cupules, animal figures, and abstract motifs carved into laterite boulders, dating to the Neolithic and suggesting symbolic or ritual functions amid early settled communities.[10] Megalithic dolmens, cairns, and cist burials appear in surrounding locales such as Kampli taluk and Kudligi, marking Iron Age transitions around 1200–300 BCE, with artifacts like black-and-red ware pottery and iron implements pointing to funerary practices and technological advancements in metallurgy.[11] A 2024 excavation in Sandur's forested hills uncovered a Stone Age cave site yielding microlithic tools and animal bones, confirming Paleolithic or Mesolithic habitation in the region's iron-rich terrain, which likely supported early resource extraction.[12] During the ancient period, from the 3rd century BCE, the area experienced Mauryan oversight, as inferred from broader Deccan edicts, transitioning to Satavahana influence by the 1st century BCE. Epigraphic traces are sparse, limited to a Pulumavi inscription in the district, challenging claims of Bellary as the dynasty's origin despite its proximity to early power centers; the scarcity of coins and records underscores reliance on regional archaeology over textual attribution.[13] Natural granite outcrops and Deccan Plateau access positioned Ballari strategically for resource control, facilitating prehistoric tool distribution and later administrative nodes.[8]Medieval Era and Vijayanagara Empire

The Ballari region formed part of the Vijayanagara Empire's territorial expanse following its establishment in 1336 CE by Harihara I and Bukka Raya I, serving as a frontier zone against northern threats from the Bahmani Sultanate and later Deccan powers.[14] Under Bukka Raya I's expansions from 1356 to 1377 CE, the empire consolidated control over Karnataka's interior, incorporating Ballari into its administrative framework through assigned nayakas who managed local governance and revenue collection.[15] This integration bolstered the empire's defensive perimeter, with Ballari's hilly terrain aiding in strategic fortifications. In the 16th century, during the empire's later phase under the Tuluva and Aravidu dynasties, local feudatory Hande Hanumappa Nayaka (r. c. 1497–1582 CE) constructed the upper portion of Ballari Fort atop Ballari Gudda to fortify the area against invasions.[5] As a palegar chief loyal to Vijayanagara, Hanumappa's fortification efforts enhanced regional security, enabling the maintenance of trade routes and agricultural production amid ongoing conflicts with Bahmani successors. The fort's robust granite walls and elevated position underscored its role in surveillance and rapid mobilization, reflecting the empire's reliance on decentralized military obligations from vassals. Economically, Ballari contributed to Vijayanagara's agrarian base, with land revenue from crops like millets, pulses, and cotton forming a key revenue stream assessed at one-sixth to one-fourth of produce.[15] Irrigation systems, including tanks and channels, supported cultivation in the semi-arid landscape, while the region's proximity to Hampi facilitated provisioning of the capital. Though mineral resources like iron were extracted empire-wide for metallurgy, Ballari's primary output remained agricultural, sustaining the nayaka system's fiscal demands. The empire's defeat at the Battle of Talikota on January 23, 1565 CE, by a coalition of Deccan sultanates, precipitated a rapid decline, with the sacking of Hampi eroding central authority and triggering fragmentation.[16] In Ballari, this power vacuum empowered local rulers like the Hande Nayakas to assert de facto independence, transitioning from feudatories to autonomous governors amid the Aravidu dynasty's futile restoration efforts. The ensuing instability invited subsequent incursions, yet the fort's defenses allowed the Hande lineage to retain control until Hyder Ali's conquest in 1769 CE, illustrating how the battle's causal disruption shifted power dynamics from imperial cohesion to regional polities.[17]Colonial Period and Independence

Following the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War in 1799, the Bellary region fell under British control, with the East India Company establishing formal administration around 1800 as part of the Madras Presidency. Bellary became the headquarters of its district in the presidency's Southern Division, serving as a major military cantonment garrisoned by British and native troops to secure southern India. The colonial administration emphasized revenue extraction from agriculture and land taxes, while surveys in the late 19th and early 20th centuries revealed substantial mineral resources, including iron ore deposits identified by British geologist Bruce Foote in the Bellary-Hospet-Sandur area around 1900.[18][19][20][21] Bellary residents contributed to the independence struggle, particularly through participation in the Non-Cooperation Movement of the 1920s. On October 1, 1921, Mahatma Gandhi visited the city, spending eight hours at the railway station where he addressed gatherings and provided guidance to local Kannada and Telugu Congress committees on non-violent resistance. Prominent local figures, including freedom fighter Bellary Siddamma, engaged in satyagraha campaigns and mobilized support against British policies, reflecting broader regional discontent with economic exploitation and administrative overreach.[22][23][24] After India's independence in 1947, Bellary district initially remained within Madras State. In 1953, amid the formation of Andhra State, its Kannada-speaking taluks were transferred to Mysore State to align linguistic boundaries, marking a key step in regional unification. Early post-integration priorities included bolstering rail infrastructure, originally developed under British rule for troop and commodity transport, to enhance mineral resource exports and connect Bellary more effectively to emerging national markets.[25][26]Post-Independence Developments

Following independence in 1947, Bellary district remained part of Madras State until 1953, when it was transferred to Mysore State (later renamed Karnataka in 1973) as part of linguistic boundary adjustments accompanying the formation of Andhra State, with Kannada-speaking areas reassigned to Mysore.[27] This reorganization aligned administrative divisions with regional languages, fostering local identity and governance suited to Kannada speakers. Urbanization in Ballari accelerated post-1950s, driven by expanding mining operations and ancillary industries, though the district's population growth rate remained moderate at around 25% in the 2001-2011 decade amid broader Karnataka trends of rural-to-urban migration for economic opportunities.[28] Economic pivots intensified after India's 1991 liberalization and the 1993 National Mineral Policy, which encouraged private participation in mining; iron ore extraction in Ballari surged, with production tripling between 2001 and 2006 due to global demand, particularly from China.[29] This boom generated substantial employment in direct mining activities—employing tens of thousands—and ancillary sectors like transportation, construction, and hospitality, transforming Ballari into a key contributor to Karnataka's mineral exports despite uneven local benefits.[30] To diversify beyond mining, the Karnataka Industrial Areas Development Board (KIADB) expanded infrastructure post-2000, including allotments in areas like Kuduthini for steel and manufacturing projects, such as the 1,828-acre site granted to ArcelorMittal around 2010, aiming to attract large-scale industries with improved roads, power, and logistics.[31] On November 1, 2014, the city of Bellary was officially renamed Ballari, reflecting Kannada heritage and phonetic accuracy, as part of a state-wide initiative updating 12 city names approved by the central government.[32] However, the mining sector faced severe disruptions in the 2010s when the Supreme Court imposed a ban on July 29, 2011, halting operations across Ballari, Hospet, and Sandur taluks due to widespread illegal mining and environmental degradation, leading to thousands of job losses and a contraction in local GDP as exports and related revenues plummeted.[33] Partial resumption followed in 2012-2013, but the episode underscored vulnerabilities in over-reliance on unregulated extraction.[34]Geography

Location and Physical Features

Ballari is situated in the eastern region of Karnataka state, India, at geographic coordinates approximately 15°09′N 76°55′E.[35] The city lies at an elevation of about 571 meters above sea level, contributing to its semi-arid landscape and positioning within the Deccan Plateau.[36] The surrounding Ballari district spans 8,447 square kilometers and shares boundaries with districts such as Chitradurga to the west, Raichur to the north, and Andhra Pradesh's Anantapur district to the east, influencing regional trade and migration patterns.[37][35] The Tungabhadra River, a major tributary of the Krishna River, flows in proximity to Ballari, originating from the Western Ghats and passing through the district's northern areas before reaching the Tungabhadra Dam near Hospet. This river system supports irrigation for agricultural lands in the region, enabling cultivation of crops like paddy and pulses during dry seasons through controlled releases from the dam.[38] However, heavy monsoon inflows and occasional dam gate failures have led to elevated water levels, prompting flood preparedness measures in Ballari, as seen in July 2025 when officials were alerted due to rising river levels.[39] Urban development in Ballari has followed patterns of radial expansion from the historic core around Ballari Fort, driven by mining-related growth and infrastructure, with the municipal area covering approximately 82 square kilometers as of recent municipal data, though ongoing sprawl incorporates adjacent villages into the urban fabric within the broader district expanse.[40] This expansion reflects the city's role as a regional hub, with transport corridors like National Highway 67 facilitating connectivity to Bengaluru and Hyderabad.Climate and Weather Patterns

Ballari exhibits a semi-arid climate under the Köppen-Geiger classification BSh, marked by hot temperatures, low humidity, and erratic precipitation primarily influenced by the southwest monsoon.[41] [42] The region receives an average annual rainfall of approximately 550 mm, with 70-80% concentrated between June and September, leading to prolonged dry periods outside the monsoon season that constrain water availability for local ecosystems and farming.[43] Summer months from March to May bring extreme heat, with maximum temperatures frequently surpassing 40°C and occasionally reaching 43°C as recorded by the India Meteorological Department (IMD), while relative humidity drops below 30%, intensifying aridity.[44] Winters from December to February are milder, with minimum temperatures averaging 15-18°C and rare dips to 12°C, accompanied by clear skies and minimal rainfall under 20 mm per month.[44] Post-monsoon (October-November) and pre-monsoon periods feature transitional weather with sporadic thunderstorms but overall low precipitation, averaging 50-100 mm combined. Analysis of IMD and Karnataka State Natural Disaster Monitoring Centre data post-2000 reveals empirical trends of lengthening dry spells, with Bellary among districts experiencing heightened frequency of extreme dry conditions—up to 20-30% more prolonged deficits in non-monsoon seasons compared to 1980-2000 baselines—correlating with reduced soil moisture and heightened drought vulnerability that undermines crop yields in rainfed areas.[45] [46] These patterns, driven by shifting monsoon dynamics rather than localized factors alone, have increased inter-annual rainfall variability by 10-15% in recent decades, per trend studies.[43] [47]Geology and Mineral Resources

The geological foundation of Ballari district is rooted in the Archaean Dharwar Craton, where the Sandur Schist Belt—a component of the Dharwar Supergroup—spans approximately 2,500 square kilometers across Ballari, Hospet, and Sandur regions, featuring volcano-sedimentary sequences of metavolcanics, metasediments, and banded iron formations (BIF).[48] These BIFs, dated to 2.9–2.6 billion years ago, represent chemical sediments deposited in shallow marine basins during periods of elevated oceanic iron concentrations in oxygen-poor environments, alternating with chert or jasper bands to form iron-rich layers up to several meters thick.[49] The craton's stabilization through tectonic accretion preserved these formations against significant metamorphism, unlike more deformed terrains elsewhere, enabling their exposure via erosion.[50] Primary BIF mineralogy includes magnetite, hematite, and siderite interbedded with quartz, but high-grade hematite ores (>60% Fe) predominant in the region result from subsequent hydrothermal fluid interactions and supergene weathering processes, where percolating meteoric waters leached silica and gangue minerals, concentrating residual iron oxides—a causal outcome of the craton's long-term exposure to tropical climates since the Proterozoic without major tectonic overprinting.[51] This enrichment mechanism contrasts with unaltered BIFs elsewhere, yielding massive hematite-quartzite lenses in the Hospet and Sandur belts, as mapped by Geological Survey of India (GSI) explorations starting from the 1940s and intensifying in the 1960s.[52] Initial GSI-linked estimates by Venkataram and Dutt in 1940 quantified reserves at 130 million tonnes, with later validations expanding assessments through drilling and geophysical surveys.[52] Verifiable iron ore resources in Ballari's BIF-hosted deposits are estimated at 1.148 billion tonnes of hematite ore, primarily in the Sandur-Hospet ranges, as per Indian Bureau of Mines (IBM) data from 2005, underscoring the district's role in national reserves through consistent high-Fe content averaging 58–65% in key outcrops.[53] These figures derive from systematic GSI and IBM resource categorization, distinguishing proved reserves from inferred resources based on density logging and assay data, though ongoing explorations refine boundaries amid structural complexities like strike-slip faults displacing BIF bands.[54] Associated minerals include minor manganese in interbedded cherts, but iron dominates, with no significant non-ferrous resources altering the BIF-centric profile.[48]Demographics

Population Dynamics and Growth

According to the 2011 Census of India, the population of Ballari city stood at 410,445, while the undivided Bellary district (encompassing present-day Ballari and Vijayanagara districts) recorded 2,452,595 residents.[55][56] The district's population grew by 20.99% over the 2001-2011 decade, from 2,027,515, reflecting net migration alongside natural increase, particularly inflows tied to mining opportunities.[56] Ballari city's population rose from 316,766 in 2001 to 410,445 in 2011, yielding a decadal growth of approximately 29.6%, outpacing the district average due to concentrated urban pull factors.[57] In the undivided district, 37.52% of the population resided in urban areas (920,239 persons), with the remainder in rural settings, indicating a moderate urbanization trajectory amid resource-driven settlement patterns.[56] The district's population density reached 290 persons per square kilometer by 2011, up from 240 in 2001, concentrated around mining hubs and transport nodes.[56] Post-2020 administrative bifurcation into Ballari and Vijayanagara districts reduced Ballari's jurisdictional population to approximately 1,400,970 as of provisional 2011-aligned estimates adjusted for the split, with urban share rising to about 45% (628,626 urban residents). Projections estimate Ballari city's population at around 586,000 by 2025, implying an average annual growth rate of roughly 2.4% since 2011, sustained by persistent in-migration and limited natural decline offsets.[59] This includes transient labor populations fluctuating with mining cycles, contributing to undercount risks in static censuses but bolstering short-term urban density.[4] Overall, Ballari's dynamics exhibit above-state-average expansion, with Karnataka's decadal growth at 15.6% for comparison, underscoring localized economic attractors over broader fertility trends.Linguistic Composition

According to the 2011 Indian census data for Ballari district, Kannada is the dominant mother tongue, reported by approximately 68% of the population, establishing it as the primary language of communication in rural and administrative contexts. Telugu follows as a significant minority language, spoken by around 17% of residents, attributable to geographic proximity to Telugu-speaking regions and labor migrations tied to mining and agriculture. Urdu accounts for about 9%, primarily among Muslim communities, while Hindi, Marathi, and Tamil each represent smaller shares under 3%. A notable historical linguistic element is the Marathi-speaking Darji (tailor) community, which migrated from Maharashtra during World War I to manufacture military uniforms for British forces, comprising less than 2% of the population but exerting outsized influence on Ballari's garment and textile trades through specialized stitching expertise.[60] This migration predates large-scale industrial shifts and underscores early 20th-century economic pulls rather than later policy incentives. Multilingual proficiency, encompassing Kannada, Telugu, and Urdu, prevails in Ballari's commercial spheres, particularly mining exports and cross-border trade, enabling pragmatic exchanges among diverse groups without enforced assimilation. Urban areas exhibit higher bilingualism rates due to workforce mobility, contrasting with more monolingual Kannada use in surrounding villages.Religious and Social Structure

In Ballari district, Hinduism predominates, accounting for 85.77% of the population, while Islam constitutes 13.08%, Christianity 0.57%, and other religions smaller shares, as per the 2011 Census of India.[61] This composition reflects a pattern of religious coexistence, with Hindu temples and Muslim mosques integrated into urban and rural landscapes, though localized frictions have occasionally arisen from resource competition in mining areas.[61] Social structure is marked by substantial Scheduled Caste (SC) and Scheduled Tribe (ST) populations, at 21.1% and 18.4% respectively, which shape community hierarchies and access to opportunities amid the district's mining economy.[61] Literacy rates stood at 67.43% overall in 2011, with males at 76.64% and females at 58.09%, indicating a persistent gender gap of about 18.6 percentage points, though state-wide trends show gradual narrowing through targeted interventions.[62] Mining prosperity has influenced family dynamics, particularly in Sandur taluk, where booms in iron ore extraction since the early 2000s have fostered extended household formations as wealth accumulation enables multi-generational co-residence and pooled resources, diverging from traditional nuclear units in agrarian contexts.[63] These shifts reinforce kinship networks but also amplify caste-based alliances in labor and land disputes.[63]Economy

Mining Sector Dominance

The mining sector, centered on iron ore extraction, has long dominated Ballari's economy, serving as the primary driver of local GDP and state-level mineral revenues. Prior to the Supreme Court-mandated bans in 2011, annual iron ore production in the Bellary-Hospet-Sandur region of Ballari district averaged around 25-30 million tonnes, representing a substantial share of Karnataka's output, which peaked at approximately 40 million tonnes statewide.[53][64] This production contributed significantly to Karnataka's mineral revenues, with estimates indicating iron ore from Ballari accounting for over 18-20% of the state's mining income during peak years, underscoring the district's pivotal role in national supply chains.[65] Major industrial players, including JSW Steel's Vijayanagar Works—a fully integrated facility spanning 10,000 acres in Toranagallu—have anchored operations by processing local high-grade hematite ore into steel, with captive mining supporting downstream manufacturing.[66] The sector's expansion generated direct employment for several thousand workers in extraction and processing, with empirical assessments pointing to over 100,000 jobs when including indirect roles in transportation, logistics, and ancillary services, though precise figures vary due to informal labor prevalence.[65][67] Post-1993 National Mineral Policy liberalization, which encouraged private participation, Ballari's mining output surged, transforming the district into a key exporter amid global demand spikes.[68] The 2000s boom, driven by iron ore exports to China—which absorbed up to 83% of India's shipments by 2005-06—created economic multipliers through heightened royalties, trade, and infrastructure investments, elevating local per capita income but tying growth tightly to commodity cycles.[33][69] This period saw annual exports from the region exceed 40 million tonnes at peaks, amplifying the sector's centrality before regulatory interventions curbed activities.[70]Agriculture and Allied Activities

Agriculture constitutes a foundational economic activity in Ballari district, engaging roughly 75% of the local labor force despite competition from the mining sector. Principal crops encompass groundnut as a major cash crop, bajra (pearl millet) suited to semi-arid conditions, and paddy in irrigated zones, alongside horticultural produce such as mango, pomegranate, fig, and sapota. These crops underpin food security and rural livelihoods, with groundnut and millets dominating rainfed areas while paddy benefits from canal systems.[71][72] Irrigation plays a pivotal role in enhancing productivity, primarily through the Tungabhadra Dam, constructed between 1949 and 1953 across the Tungabhadra River. The dam facilitates commanded irrigation over approximately 300,000 hectares in Ballari and adjacent districts like Raichur and Koppal, supporting paddy cultivation and enabling rabi-season crops such as groundnut and chickpea via right-bank and left-bank canals. This infrastructure, managed jointly by Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh under the Tungabhadra Board, has expanded cultivable land post-independence, mitigating rainfall variability in the region's drought-prone terrain.[73][74] Mining-induced environmental stressors, particularly airborne dust from iron ore extraction, have documented adverse effects on yields. Empirical analyses attribute productivity drops to dust accumulation on foliage, impairing photosynthesis and accelerating soil degradation, with affected zones registering notable declines compared to non-mining baselines. Field studies in Ballari's mining vicinities link these impacts to reduced biomass and grain output in crops like groundnut and millets.[75][68] Livestock rearing and dairy activities complement crop farming, providing income diversification amid yield uncertainties. The district sustains a livestock population dominated by indigenous cattle breeds, exceeding one million heads as per regional censuses, which bolsters milk production and draught power needs. Dairy cooperatives leverage this base for value addition, though low crossbred adoption limits yields relative to state averages.[76][77]Industrial Diversification and Textiles

Ballari's textile sector has evolved as a significant non-mining industrial activity, particularly through garment manufacturing focused on jeans production and processing. Clusters specializing in jeans pant manufacturing and washing units have developed in the district, including areas near Hospet, contributing to employment in small-scale operations. These units handle denim finishing processes such as washing and embroidery, supporting export-oriented garment supply chains. Steel processing represents another avenue of industrial diversification, with facilities utilizing locally available iron ore for value-added production. JSW Steel's Vijayanagar Works in Ballari district, commissioned in the mid-1990s, saw major capacity expansions post-2000, including integrated steel-making units that process ore into finished products like hot-rolled coils.[78] Planned investments, such as NMDC's proposed Rs 18,000 crore steel plant in 2014, aimed to further bolster downstream processing, though implementation faced delays amid regulatory hurdles.[79] The sector grapples with persistent challenges, including frequent power shortages that disrupt operations and lead to idle machinery and worker downtime.[80] [81] Water scarcity has forced closures of numerous jeans washing units, exacerbating production halts during peak seasons.[82] Labor shortages, partly due to migration following the 2011 mining restrictions, compound these issues, with many units operating below capacity as of 2024.[80] [83] To address skill gaps in textiles and manufacturing, Karnataka's District Skill Development Plan for 2024-25 includes targeted training programs for Ballari, emphasizing sectors like apparel processing and industrial operations to improve employability and retention.[84] These initiatives align with the state's broader industrial policy for 2025-30, which promotes MSME upskilling to foster sustainable diversification.[85]Environment and Resource Management

Ecological Impacts of Extraction

Mining activities in Ballari district, particularly iron ore extraction, have caused substantial deforestation, with a 2011 Central Empowered Committee report estimating a 45% loss of forest cover attributable to mining operations. Satellite-based assessments indicate that between 2001 and 2012, tree cover loss in the district exceeded 10,000 hectares in mining hotspots like the Sandur schist belt, where open-pit methods cleared vast areas of dry deciduous forests. This deforestation disrupts local ecosystems, reducing habitat for species adapted to the region's scrub and woodland biomes and altering microclimates through loss of canopy cover.[86][87] Soil erosion rates have intensified due to vegetation removal and overburden dumping, with Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation (RUSLE) models applied to Sandur taluk revealing annual potential losses of 20-46 tons per hectare in actively mined zones—rates 4-9 times higher than baseline erosion in undisturbed Karnataka landscapes (typically 5-10 t/ha/yr). Exposed pit walls and haul roads facilitate accelerated runoff, leading to gully formation and sedimentation in downstream valleys, which smother riparian zones and reduce soil fertility through nutrient stripping. These biophysical changes exacerbate land degradation, with geospatial analyses confirming that 15-20% of the district's area exhibits heightened vulnerability to erosion linked directly to mining topography alterations.[88][89] Water bodies, including the Tungabhadra River, experience contamination from mining tailings and overburden leachate, introducing sediments, iron oxides, and trace metals that elevate turbidity and alter aquatic chemistry. Downstream segments of the Tungabhadra exhibit discoloration to brown hues and elevated pollutant loads from industrial and mining effluents, impairing primary productivity in riverine habitats. Groundwater in mining vicinities shows pH stabilization around 7.2-7.4 amid heavy metal influx, though surface flows reflect episodic acidification from acid mine drainage, documented in regional hydrochemical surveys. These inputs degrade benthic communities and disrupt food webs by smothering substrates essential for macroinvertebrates.[90][91][92] Dust emissions from quarrying and transport elevate particulate matter (PM10) concentrations near extraction sites to levels often 2-3 times World Health Organization interim guidelines (45 µg/m³ for 24-hour averages), with environmental monitoring recording exceedances of India's National Ambient Air Quality Standards (100 µg/m³ 24-hour) across a 10 km radius of Ballari's mining clusters. Fine particulates settle on foliage, reducing photosynthetic efficiency in remnant vegetation and contributing to atmospheric deposition that acidifies soils, thereby hindering natural regeneration in overburdened landscapes. Central Pollution Control Board-aligned assessments link these elevations causally to haulage and blasting operations, underscoring mining's role in regional air-shed degradation.[68][93]Health and Community Effects

Mining activities in Ballari district, particularly iron ore extraction, have been associated with elevated rates of respiratory illnesses among local populations, primarily due to chronic exposure to airborne dust containing silica, iron oxides, and other particulates. A 2012 Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) report documented a significant rise in respiratory disorders in mining-intensive areas like Hospet taluk, where cases increased to 10,369 by 2010, alongside heightened tuberculosis incidence linked to dust inhalation and poor ventilation in surrounding communities.[94] Studies on mine workers indicate restrictive lung impairment in approximately 15% of cases, with symptoms including chronic cough, asthma, and reduced pulmonary function from prolonged particulate exposure.[95] In child populations near extraction sites, such as Sandur, asthma prevalence reaches about 20%, attributed to ambient dust settling on households and schools.[96] Dust pollution from open-cast operations has also contributed to oral mucosal damage, with genotoxic effects observed in buccal cells of exposed individuals, including elevated micronuclei frequencies indicative of cellular stress and potential carcinogenesis.[97] These health burdens show temporal patterns aligned with mining intensification; prior to the post-1990s export boom, respiratory case incidences were notably lower, with spikes correlating to expanded operations lacking adequate dust suppression, as evidenced by pre-boom baseline health surveys versus current epidemiological data.[28] This suggests limited efficacy of existing regulations in mitigating inhalation risks, despite threshold limits for respirable dust. Community-level effects extend to nutritional deficiencies stemming from mining-induced agricultural disruptions, where dust deposition on crops reduces yields and contaminates soil, exacerbating food insecurity in rural pockets.[68] The influx of migrant laborers during peak extraction phases has strained social fabrics, leading to family separations, increased HIV prevalence—Ballari reporting the highest rates in Karnataka—and disruptions in child care, with reports of heightened vulnerability to infectious diseases among left-behind households.[98] These strains, documented in socio-economic assessments of mining laborers, include elevated stress-related disorders and community conflicts over resources, underscoring causal links between labor mobility and localized social fragmentation without offsetting public health interventions.[99]Regulatory Responses and Sustainability

In response to rampant illegal mining, the Supreme Court of India imposed a ban on iron ore extraction in Bellary (now Ballari) district in July 2011, following recommendations from the Central Empowered Committee that documented extensive violations, including operations in forest areas and revenue losses exceeding ₹16,000 crore.[98] [100] This measure extended to probes by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), which arrested Gali Janardhana Reddy, a former Karnataka minister, in September 2011 for orchestrating illegal mining through entities like Obulapuram Mining Company, involving boundary manipulations and extraction beyond lease limits that caused an estimated ₹884 crore loss in one case alone.[101] [102] The ban triggered severe economic contraction, with local iron ore output plummeting by over 50% from pre-2011 peaks—Karnataka's production, of which Ballari contributed about 75%, fell sharply—and leading to approximately 150,000 direct job losses among miners and ancillary workers, many without alternative livelihoods.[103] [98] Surveys indicated 85% of affected workers lacked other income sources, exacerbating socio-economic distress in a region dependent on mining for 24% of India's iron ore supply.[104] Ecologically, the halt enabled partial forest regrowth in some abandoned sites, with satellite data showing modest vegetation recovery in monitored areas, though legacy degradation like soil erosion and water contamination persisted without comprehensive restoration.[105] [28] Mining resumed selectively post-2011 under stricter oversight, with full legal operations tied to auctions mandated by the Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Amendment Act of 2021, leading to e-auctions of Ballari leases from 2020 onward that prioritized compliant bidders.[106] Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) became mandatory for expansions, as evidenced by approvals for Sandur Manganese & Iron Ores Limited, which secured enhanced clearances in 2023-2024 to increase iron ore output from 1.6 million tonnes per annum (MTPA) to 4.5 MTPA, subject to pollution controls and reclamation plans.[107] However, enforcement gaps remain, with reports of ongoing illegal extraction in Ballari—spanning over 3,300 acres of forest since 2010—despite these frameworks, allowing expansions like those in Sandur while CBI trials, such as Reddy's, extended into 2025 with limited deterrence.[108] [109] Sustainability efforts emphasize balancing extraction with mitigation, including mandatory mine closure plans under the 2016 Sustainable Mining Guidelines, which require progressive reclamation in Ballari leases, though compliance varies; post-ban data show stabilized groundwater levels in some zones but persistent deforestation risks from renewed activities.[110] Critics argue that while bans curbed overt illegality, economic imperatives have led to lax oversight, with production rebounding to near pre-ban levels by 2020 without proportional ecological offsets, underscoring trade-offs where revenue recovery (e.g., via auctions generating billions in premiums) often prioritizes output over long-term viability.[106] [111] Proponents of regulated mining cite improved transparency in auctions as a step toward sustainability, yet independent assessments highlight the need for verifiable restoration metrics to prevent recurrence of 2011-scale violations.[112]Infrastructure

Transportation Networks

Ballari's transportation infrastructure centers on road and rail networks critical for passenger movement and freight, particularly iron ore from local mines. National Highway 67 (NH-67) traverses the city, connecting it to Hospet and beyond, with a six-lane section developed between Hospet and Ballari to handle increased traffic.[113] NH-150A, a spur from NH-50, links Ballari to surrounding areas, supporting ore transport logistics. These highways see heavy truck usage for mining exports, contributing to regional freight volumes exceeding passenger traffic.[114] Rail connectivity is provided by Ballari Junction under the South Western Railway zone, with approximately 44 train arrivals and 42 departures daily, including mail, express, and passenger services on the Hospet-Ballari line.[115] The station handles over 50 halting trains, serving passenger demands to major cities like Bengaluru and Mumbai while facilitating ore-laden freight trains.[116] Bus services, operated primarily by Karnataka State Road Transport Corporation (KSRTC), link Ballari to Bengaluru, approximately 307 km away, with hourly departures taking about 5 hours 15 minutes.[117] These routes carry significant passenger loads, supplemented by private operators for inter-state travel. Air access is limited at Jindal Vijayanagar Airport (VDY), located near Toranagallu, which primarily supports private and charter flights with no regular commercial services as of 2023.[118] The facility aids mining executives but relies on regional airports like Hubli for broader connectivity. Road networks face challenges from overloaded mining trucks, exacerbating wear on highways like NH-67 during peak export periods in the 2020s.[119]Urban Development Projects

Ballari's urban development has emphasized industrial expansion and skill enhancement to support its status as the second-fastest growing city in Karnataka.[1] Key projects include the acquisition of 154 acres in Sajjanjeerayanakote for the Ballari Jeans Park in August 2025, intended to bolster garment manufacturing by attracting global businesses relocating from regions like Bangladesh.[120] This initiative, overseen by the Karnataka Industrial Areas Development Board (KIADB), follows land purchase at Rs 40 crore per acre and issuance of work orders to develop infrastructure for jeans production units.[121] Complementing industrial growth, the KIADB Kudathini Women's Entrepreneur Park spans 48 acres to foster women-led enterprises in the district.[122] These parks contribute to urban land utilization for economic diversification, though total additions fall short of expansive targets and focus on targeted sectors like textiles. Skill development aligns with these efforts through the Ballari District Skill Development Plan for 2024-25, which prioritizes mobilization, counseling, and industry partnerships to build local workforce capabilities.[84] Despite progress, unchecked urbanization has exacerbated informal settlements, with slums housing approximately 22% of the city's urban population—90,404 individuals across 18,611 households as of the 2011 census.[55] This proliferation underscores challenges in integrating migrant inflows and planned housing, with ongoing slum coverage under schemes like the Integrated Housing and Slum Development Programme estimated at 20% of affected areas.[123]Utilities and Public Services

Ballari's electricity distribution is managed by the Gulbarga Electricity Supply Company Limited (GESCOM), covering the district with a high household electrification rate exceeding 95 percent as part of Karnataka's statewide push under schemes like Saubhagya. However, mining operations, including iron ore extraction and steel production at facilities like JSW Steel Vijayanagar Works, drive significant demand peaks, straining the grid and contributing to voltage fluctuations during high-consumption periods. Monsoon flooding, as seen in August 2025 when heavy rains disrupted infrastructure in Ballari and neighboring Raichur, frequently causes power outages, highlighting underinvestment in resilient transmission lines and substations amid climate vulnerabilities.[124][125] Public water supply in Ballari city draws primarily from the Tungabhadra River through the Low Level Canal and High Level Canal systems, supporting urban distribution but with intermittent supply affecting reliability. Approximately 60 percent of urban households receive piped connections, supplemented by groundwater sources that meet about 50 percent of urban needs, though contamination risks persist from industrial runoff. Shortages intensify during dry seasons, exacerbated by competing irrigation demands upstream, prompting projects like the proposed Ballari Augmentation Recycled Water Treatment Plant to recycle effluent for non-potable industrial use.[126] Solid waste management faces gaps, particularly from industrial effluents generated by mining, steel processing, and textile dyeing units, which have led to regulatory actions such as potential closures of non-compliant jeans dyeing facilities lacking effluent treatment plants as of June 2025. The Ballari City Corporation handles municipal solid waste collection, but processing capacity lags, with recent developments including a 20 TPD solid waste management facility proposed in Varalahalli village following public hearings in December 2021. Post-2018 initiatives under Karnataka's waste rules have established composting and landfill sites in the district, yet audits reveal incomplete implementation, resulting in open dumping and pollution risks tied to underfunded infrastructure.[127][128][129]Governance and Administration

Local Government Structure

The Ballari City Municipal Corporation (BMC), established in 2004, serves as the primary urban local body responsible for administering the city's municipal affairs across an area of approximately 90 square kilometers divided into more than 40 wards.[130][131] The corporation manages essential services including urban planning, waste management, water supply, and public health infrastructure, operating under the Karnataka Municipal Corporations Act with a council comprising elected ward representatives led by a mayor and commissioner.[132][133] At the district level, the Deputy Commissioner, also known as the District Collector, heads the collectrate and coordinates administrative functions, including the oversight of mining operations through approvals, compliance monitoring, and coordination with the state Department of Mines and Geology for lease allocations.[134][135] Royalties and revenues from iron ore mining leases, a dominant economic activity, are channeled into local development via the District Mineral Foundation (DMF), which mandates contributions from leaseholders—equivalent to 30% of royalty payments—for infrastructure, health, and rehabilitation projects in affected areas, with Ballari's DMF managing funds from over 140 active mines spanning thousands of hectares. Pursuant to the 73rd Constitutional Amendment for rural decentralization, governance in Ballari's outlying taluks, including mining-intensive regions like Sandur and Hosapete, operates through a three-tier Panchayati Raj system comprising gram panchayats at the village level, taluk panchayats, and the zilla panchayat at the district level.[136] Gram panchayats in these rural mining zones handle localized functions such as basic infrastructure maintenance, environmental mitigation, and community welfare, empowered to levy taxes and allocate DMF-derived funds for sustainable resource management amid extraction activities.[137] This structure promotes grassroots decision-making while integrating with district-level oversight for mineral revenue distribution.Political Representation and Elections

The Ballari Lok Sabha constituency, one of 28 in Karnataka, encompasses the district's urban and rural areas and has historically been influenced by mining interests, with the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) dominating from 2009 to 2019 due to alliances with local industrial lobbies.[138] In the 2024 general election, however, the Indian National Congress (INC) candidate E. Tukaram secured victory with 730,845 votes (approximately 50.6% of valid votes polled), defeating BJP's B. Sriramulu, who received 620,959 votes, in a contest marked by anti-incumbency against the ruling BJP-JD(S) coalition at the state level prior to the polls.[139] Voter turnout in the constituency stood at about 69.5%, reflecting typical participation rates in the region amid logistical challenges in rural mining pockets.[139] At the state level, Ballari district includes five assembly constituencies—Ballari City, Ballari Rural (ST), Ballari (ST), Kudligi, and Siruguppa—where elections in 2023 saw INC sweep all seats, reversing BJP's hold from 2018.[140] In Ballari City, INC's Nara Bharath Reddy won with 85,217 votes (margin of 37,863 over JD(S)), while in Ballari Rural (ST), INC's B. Nagendra triumphed with a similar margin; turnouts ranged from 72-76% across these segments, driven by local welfare promises countering mining-related discontent.[141][142] This shift aligned with INC's statewide gains, capturing 135 of 224 seats, as mining lobbies—historically aligned with BJP through figures like the Reddy brothers—faced probes and bans, diluting their sway.[143] Electoral dynamics in Ballari are shaped by caste blocs, including Telugu-speaking Reddys (a dominant mining community) and Kannada-speaking Lingayats and Scheduled Tribes, with Telugu influences often prioritizing pro-extraction policies over environmental regulations.[144] The 2011-2012 illegal mining scam, involving overexploitation worth billions and implicating BJP leaders like Gali Janardhana Reddy, led to Supreme Court interventions, CBI probes, and temporary mining halts, eroding incumbent support in subsequent cycles; for instance, Reddy's 2022 launch of Kalyana Rajya Pragati Paksha aimed to reclaim influence but yielded minimal seats, highlighting fragmented lobby power.[145][138] Despite such controversies, parties across the spectrum have courted mining voters, with BJP regaining ground in 2018 via promises of lease revivals, though INC's 2023-2024 successes underscore voter prioritization of enforcement against illicit operations.[146]Education and Human Capital

Educational Institutions

Vijayanagara Sri Krishnadevaraya University (VSKU), established in 2010 by the Government of Karnataka, functions as the principal public university in Ballari, encompassing 28 academic departments and affiliating approximately 120 colleges for undergraduate, postgraduate, and doctoral programs in fields including arts, science, commerce, and law.[147] The institution targets elevating the gross enrollment ratio in higher education, recorded at 9.57% for Ballari district as of recent assessments.[147] Engineering education features prominently due to the region's mining industry, with institutions such as Ballari Institute of Technology and Management (BITM), offering accredited bachelor's degrees in engineering disciplines including civil, mechanical, and computer science, alongside management programs.[148] Rao Bahadur Y. Mahabaleswarappa Engineering College provides similar technical courses, emphasizing sustainable mining technologies amid local iron ore extraction activities.[149] Polytechnics like T.M.A.E.S. in nearby Hosapete (Ballari district) deliver diploma programs in mining engineering, equipping students with practical skills for extractive industries through specialized labs and field training.[150] Primary and secondary schooling expanded under the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan initiative launched nationally in 2001, which funded infrastructure and enrollment drives in Ballari to achieve universal elementary education targets. The district hosts government higher primary schools and aided institutions, such as those affiliated with Kotturswamy College of Education for teacher training since 1963.[151] Vocational training aligns with mineral sector demands, including NMDC-operated centers in Ballari providing industry-specific skills in mining operations and safety protocols.[152] Private entities like Kishkinda University supplement offerings with programs in technology and business, fostering localized human capital development.[153]Literacy Rates and Skill Development

According to the 2011 Census of India, Ballari district recorded an overall literacy rate of 67.43%, with male literacy at 76.64% and female literacy at 58.22%.[56] Rural areas lagged significantly at 61.81%, reflecting a roughly 15 percentage point urban-rural gap, while urban literacy reached approximately 77%.[56] Female literacy trailed male rates by nearly 18 percentage points district-wide, exacerbated by socioeconomic factors in mining-dependent rural zones.[56] More recent data from the National Family Health Survey-5 (2019-21) indicates women's literacy at 64.4%, showing modest improvement but persistent gender disparities.[154] District-level projections for 2024 estimate overall literacy near 75-76%, driven by state-wide education drives, though official census updates remain pending.[155] These rates underscore Ballari's challenges in a resource-extraction economy, where basic education access has not fully translated to functional skills amid high school dropout rates in rural taluks. Skill development efforts in Ballari emphasize transitioning youth from mining reliance through targeted programs under the Karnataka Skill Development Corporation (KSDC). The District Skill Development Plan (DSDP) for 2024-25 prioritizes sectors like renewable energy, logistics, and manufacturing to address mining volatility, with expansions at Industrial Training Institutes (ITIs) in Ballari and Sandur focusing on vocational trades such as solar panel installation and heavy equipment operation.[84][156] The state approved a ₹4,432 crore Skill Development Policy in September 2025, allocating resources for reskilling 10 lakh youth annually, including AI-integrated training relevant to Ballari's emerging steel and green tech clusters.[157] Despite these initiatives, skill mismatches persist, with mining booms failing to absorb untrained labor, contributing to youth unemployment estimated at 5-7% in rural Karnataka districts like Ballari—higher than the state average of 3% for rural males.[158] Reports highlight over 33% non-workers among working-age groups, signaling underutilization amid economic growth, as short-term training often overlooks long-term employability in diversified sectors.[158] KSDC evaluations note placement rates below 50% for some programs, urging better industry linkages to mitigate these gaps.[84]Culture and Heritage

Historical Sites and Tourism

Ballari Fort, constructed during the Vijayanagara Empire in the 14th century on Ballari Gudda hill, stands as the district's primary historical attraction, featuring granite structures including watchtowers, gateways, and remnants of defensive walls that highlight medieval military architecture.[5] The fort's strategic elevation provided oversight of surrounding plains, with later additions by local rulers like Hanumappa Nayaka in the 18th century reinforcing its role in regional conflicts.[159] Visitors access the site via a series of steps and pathways, often combining exploration with views of the city below. Other notable historical sites include Neolithic settlements at Sanganakallu, dating back over 4,000 years, which reveal early human activity through rock shelters, petroglyphs, and megalithic structures evidencing prehistoric tool-making and burial practices.[160] In Hagari Bommanahalli taluk, a 9th-century Jain temple in Kogali village exemplifies Chalukya-era architecture, though now in disrepair and repurposed informally, underscoring preservation challenges for lesser-known ruins.[161] Ballari's tourism benefits from its 60-kilometer proximity to the UNESCO-listed Hampi ruins, facilitating day trips that integrate local sites into broader Vijayanagara heritage itineraries, though district bifurcation in 2020 transferred Hampi administratively to Vijayanagara district.[162] Iron ore mining landscapes offer niche exploratory potential, with vast red earth formations visible from afar, yet restricted access due to operational safety and environmental regulations limits organized tours.[6] Karnataka's post-2010 heritage circuit promotions have incrementally boosted regional visitation, though specific annual figures for Ballari remain underreported compared to state totals exceeding 200 million domestic tourists.[163]Festivals and Local Traditions

Ballari's residents celebrate a range of Hindu festivals with communal fervor, including Ugadi, Sankranti, Dasara, Diwali, Ganesh Chaturthi, Janmashtami, and Durga Puja, alongside observances like Ramzan that reflect the district's multicultural fabric shaped by Kannadiga and Andhra influences.[164] [165] These events emphasize devotion and social cohesion among the predominantly agricultural and mining-dependent population, with Sankranti incorporating Telugu customs such as ritual bathing, feasting on harvest produce, and kite-flying traditions brought by migrant communities from neighboring Andhra regions.[164] Dasara, observed in September-October, highlights Vijaya Utsava processions featuring folk performances like Dollu Kunitha (drum dances), Veeragase (vigorous Shiva devotionals), and Nandikolu Kunitha (bull dances by Shiva devotees), evoking historical victory themes tied to the region's Vijayanagara legacy.[164] The Mallara Festival, dedicated to Lord Shiva and held in February-March, draws participants for ritualistic pomp, underscoring local Shaivite practices.[164] Distinct local traditions include the annual car festival at the Jiva Samadhi of Yerri Tata, a saint who lived from 1897 to 1922, located in Chellagurki approximately 16 km from Ballari; it attracts statewide pilgrims, especially on new moon days, for chariot processions and homage.[166] These observances have scaled from rural village gatherings to urban spectacles amid Ballari's growth as a mining hub, though resource strains in arid locales occasionally limit elaborate preparations.[165]Notable Individuals

S. Nijalingappa (1902–2000), born in Haluvagalu village in Ballari district, served as Chief Minister of Mysore State (later Karnataka) from 1956 to 1958, 1962 to 1966, and 1968 to 1971; he was a key figure in the Indian independence movement and Congress party politics, including as President of the Indian National Congress from 1968 to 1969.[167] C. R. Rao (1920–2023), born on September 10, 1920, in Hadagali, Bellari district, was a pioneering statistician whose contributions include the Cramér–Rao bound and Rao–Blackwell theorem; he received the National Medal of Science in 2001 and served as director of the Indian Statistical Institute.[168] Jayanthi (1945–2021), born Kamala Kumari on January 6, 1945, in Ballari, was a leading actress in Kannada cinema, appearing in over 300 films across multiple South Indian languages from 1961 to the 1980s, known for roles in films like Jenu Goodu (1962).[169] G. Janardhana Reddy (born January 11, 1967, in Ballari), an industrialist and politician, founded the Obulapuram Mining Company and served as a Member of Parliament from 2004 to 2009 and Minister of State for Tourism from 2009 to 2011; he faced arrest in 2011 over allegations of illegal mining and corruption in the Karnataka mining scandal.[170][171]References

- https://ballari.nic.in/en/[demography](/page/Demography)/