Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Monsoon

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Weather |

|---|

|

|

A monsoon (/mɒnˈsuːn/) is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation[1] but is now used to describe seasonal changes in atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annual latitudinal oscillation of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) between its limits to the north and south of the equator. Usually, the term monsoon is used to refer to the rainy phase of a seasonally changing pattern, although technically there is also a dry phase. The term is also sometimes used to describe locally heavy but short-term rains.[2][3]

The major monsoon systems of the world consist of the West African, Asian–Australian, the North American, and South American monsoons.

The term was first used in English in British India and neighbouring countries to refer to the big seasonal winds blowing from the Bay of Bengal and Arabian Sea in the southwest bringing heavy rainfall to the area.[4][5]

Etymology

[edit]

The etymology of the word monsoon is not wholly certain.[6] The English monsoon came from Portuguese monção ultimately from Arabic موسم (mawsim, "season"), "perhaps partly via early modern Dutch monson".[7]

History

[edit]Asian monsoon

[edit]Strengthening of the Asian monsoon has been linked to the uplift of the Tibetan Plateau after the collision of the Indian subcontinent and Asia around 50 million years ago.[8] Because of studies of records from the Arabian Sea and that of the wind-blown dust in the Loess Plateau of China, many geologists believe the monsoon first became strong around 8 million years ago. More recently, studies of plant fossils in China and new long-duration sediment records from the South China Sea led to a timing of the monsoon beginning 15–20 million years ago and linked to early Tibetan uplift.[9] Testing of this hypothesis awaits deep ocean sampling by the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program.[10] The monsoon has varied significantly in strength since this time, largely linked to global climate change, especially the cycle of the Pleistocene ice ages.[11] A study of Asian monsoonal climate cycles from 123,200 to 121,210 years BP, during the Eemian interglacial, suggests that they had an average duration of around 64 years, with the minimum duration being around 50 years and the maximum approximately 80 years, similar to today.[12]

A study of marine plankton suggested that the South Asian Monsoon (SAM) strengthened around 5 million years ago. Then, during ice periods, the sea level fell and the Indonesian Seaway closed. When this happened, cold waters in the Pacific were impeded from flowing into the Indian Ocean. It is believed that the resulting increase in sea surface temperatures in the Indian Ocean increased the intensity of monsoons.[13] In 2018, a study of the SAM's variability over the past million years found that precipitation resulting from the monsoon was significantly reduced during glacial periods compared to interglacial periods like the present day.[14] The Indian Summer Monsoon (ISM) underwent several intensifications during the warming following the Last Glacial Maximum, specifically during the time intervals corresponding to 16,100–14,600 BP, 13,600–13,000 BP, and 12,400–10,400 BP as indicated by vegetation changes in the Tibetan Plateau displaying increases in humidity brought by an intensifying ISM.[15] Though the ISM was relatively weak for much of the Late Holocene, significant glacial accumulation in the Himalayas still occurred due to cold temperatures brought by westerlies from the west.[16]

During the Middle Miocene, the July ITCZ, the zone of rainfall maximum, migrated northwards, increasing precipitation over southern China during the East Asian Summer Monsoon (EASM) while making Indochina drier.[17] During the Late Miocene Global Cooling (LMCG), from 7.9 to 5.8 million years ago, the East Asian Winter Monsoon (EAWM) became stronger as the subarctic front shifted southwards.[18] An abrupt intensification of the EAWM occurred 5.5 million years ago.[19] The EAWM was still significantly weaker relative to today between 4.3 and 3.8 million years ago but abruptly became more intense around 3.8 million years ago[20] as crustal stretching widened the Tsushima Strait and enabled greater inflow of the warm Tsushima Current into the Sea of Japan.[21] Circa 3.0 million years ago, the EAWM became more stable, having previously been more variable and inconsistent, in addition to being enhanced further amidst a period of global cooling and sea level fall.[22] The EASM was weaker during cold intervals of glacial periods such as the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) and stronger during interglacials and warm intervals of glacial periods.[23] Another EAWM intensification event occurred 2.6 million years ago, followed by yet another one around 1.0 million years ago.[19] During Dansgaard–Oeschger events, the EASM grew in strength, but it has been suggested to have decreased in strength during Heinrich events.[24] The EASM expanded its influence deeper into the interior of Asia as sea levels rose following the LGM;[25] it also underwent a period of intensification during the Middle Holocene, around 6,000 years ago, due to orbital forcing made more intense by the fact that the Sahara at the time was much more vegetated and emitted less dust.[26] This Middle Holocene interval of maximum EASM was associated with an expansion of temperate deciduous forest steppe and temperate mixed forest steppe in northern China.[27] By around 5,000 to 4,500 BP, the East Asian monsoon's strength began to wane, weakening from that point until the present day.[28] A particularly notable weakening took place ~3,000 BP.[29] The location of the EASM shifted multiple times over the course of the Holocene: first, it moved southward between 12,000 and 8,000 BP, followed by an expansion to the north between approximately 8,000 and 4,000 BP, and most recently retreated southward once more between 4,000 and 0 BP.[30]

Australian monsoon

[edit]The January ITCZ migrated further south to its present location during the Middle Miocene, strengthening the summer monsoon of Australia that had previously been weaker.[17]

Five episodes during the Quaternary at 2.22 Ma ([clarification needed]PL-1), 1.83 Ma (PL-2), 0.68 Ma (PL-3), 0.45 Ma (PL-4) and 0.04 Ma (PL-5) were identified which showed a weakening of the Leeuwin Current (LC). The weakening of the LC would have an effect on the sea surface temperature (SST) field in the Indian Ocean, as the Indonesian Throughflow generally warms the Indian Ocean. Thus these five intervals could probably be those of considerable lowering of SST in the Indian Ocean and would have influenced Indian monsoon intensity. During the weak LC, there is the possibility of reduced intensity of the Indian winter monsoon and strong summer monsoon, because of change in the Indian Ocean dipole due to reduction in net heat input to the Indian Ocean through the Indonesian Throughflow. Thus a better understanding of the possible links between El Niño, Western Pacific Warm Pool, Indonesian Throughflow, wind pattern off western Australia, and ice volume expansion and contraction can be obtained by studying the behaviour of the LC during Quaternary at close stratigraphic intervals.[31]

South American monsoon

[edit]The South American summer monsoon (SASM) is known to have become weakened during Dansgaard–Oeschger events. The SASM has been suggested to have been enhanced during Heinrich events.[24]

Process

[edit]Monsoons were once considered as a large-scale sea breeze[32] caused by higher temperature over land than in the ocean. This is no longer considered as the cause and the monsoon is now considered a planetary-scale phenomenon involving the annual migration of the Intertropical Convergence Zone between its northern and southern limits. The limits of the ITCZ vary according to the land–sea heating contrast and it is thought that the northern extent of the monsoon in South Asia is influenced by the high Tibetan Plateau.[33][34] These temperature imbalances happen because oceans and land absorb heat in different ways. Over oceans, the air temperature remains relatively stable for two reasons: water has a relatively high heat capacity (3.9 to 4.2 J g−1 K−1),[35] and because both conduction and convection will equilibrate a hot or cold surface with deeper water (up to 50 metres). In contrast, dirt, sand, and rocks have lower heat capacities (0.19 to 0.35 J g−1 K−1),[36] and they can only transmit heat into the earth by conduction and not by convection. Therefore, bodies of water stay at a more even temperature, while land temperatures are more variable.

During warmer months sunlight heats the surfaces of both land and oceans, but land temperatures rise more quickly. As the land's surface becomes warmer, the air above it expands and an area of low pressure develops. Meanwhile, the ocean remains at a lower temperature than the land, and the air above it retains a higher pressure. This difference in pressure causes sea breezes to blow from the ocean to the land, bringing moist air inland. This moist air rises to a higher altitude over land and then it flows back toward the ocean (thus completing the cycle). However, when the air rises, and while it is still over the land, the air cools. This decreases the air's ability to hold water, and this causes precipitation over the land. This is why summer monsoons cause so much rain over land.

In the colder months, the cycle is reversed. Then the land cools faster than the oceans and the air over the land has higher pressure than air over the ocean. This causes the air over the land to flow to the ocean. When humid air rises over the ocean, it cools, and this causes precipitation over the oceans. (The cool air then flows towards the land to complete the cycle.)

Most summer monsoons have a dominant westerly component and a strong tendency to ascend and produce copious amounts of rain (because of the condensation of water vapor in the rising air). The intensity and duration, however, are not uniform from year to year. Winter monsoons, by contrast, have a dominant easterly component and a strong tendency to diverge, subside and cause drought.[37]

Similar rainfall is caused when moist ocean air is lifted upwards by mountains,[38] surface heating,[39] convergence at the surface,[40] divergence aloft, or from storm-produced outflows at the surface.[41] However the lifting occurs, the air cools due to expansion in lower pressure, and this produces condensation.

Global monsoon

[edit]Summary table

[edit]| Location | Monsoon/sub-system | Average date of arrival | Average date of withdrawal | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Mexico | North American/Gulf of California-Southwest USA | late May[42] | September | incomplete wind reversal, waves |

| Tucson, Arizona, USA | North American/Gulf of California-Southwest USA | early July[42] | September | incomplete wind reversal, waves |

| Central America | Central/South American Monsoon | April[citation needed] | October[citation needed] | true monsoon |

| Amazon Brazil | South American monsoon | September[citation needed] | May[citation needed] | waves |

| Southeast Brazil | South American monsoon | November[citation needed] | March[citation needed] | waves |

| West Africa | West African | June 22[43] | Sept[44] /October[43] | waves |

| Southeast Africa | Southeast Africa monsoon w/ Harmattan | Jan[44] | March[44] | waves |

| Kerala, India | Indo-Australian/Indian-Indochina/East Asian monsoon | Jun 1[45] | Dec 1[45] | persistent |

| Mumbai, India | Indo-Australian/Indian-Indochina/East Asian monsoon | June 10[45] | Oct 1[45] | persistent |

| Karachi, Pakistan | Indo-Australian/Indian-Indochina/East Asian monsoon | late June - early July[45] | September[45] | abrupt |

| Lahore, Pakistan | Indo-Australian/Indian-Indochina/East Asian monsoon | late June[45] | end of September[45] | abrupt |

| Phuket, Thailand | Indo-Australian/Indian-Indochina/East Asian monsoon | February/March | December | persistent |

| Colombo, Sri Lanka | Indo-Australian/Indian-Indochina/East Asian monsoon | May 25[45] | Dec 15[45] | persistent |

| Bangkok, Thailand | Indo-Australian/Indian-Indochina/East Asian monsoon | April–May | October/November | persistent |

| Yangon, Myanmar | Indo-Australian/Indian-Indochina/East Asian monsoon | May 25[45] | Nov 1[45] | persistent |

| Dhaka, Bangladesh | Indo-Australian/Indian-Indochina/East Asian monsoon | mid-June | October | abrupt |

| Cebu, Philippines | Indo-Australian/Borneo-Australian/Australian monsoon | October | March | abrupt |

| Kelantan, Malaysia | Indo-Australian/Borneo-Australian/Australian monsoon | October | March | waves |

| Jakarta, Indonesia | Indo-Australian/Borneo-Australian/Australian monsoon | November | March | abrupt |

| Kaohsiung, Taiwan | Indo-Australian/Indian-Indochina/East Asian monsoon | May 10[45] | October | abrupt |

| Taipei, Taiwan | Indo-Australian/Indian-Indochina/East Asian monsoon | May 20[45] | October | abrupt |

| Hanoi, Vietnam | Indo-Australian/Indian-Indochina/East Asian monsoon | May 20[45] | October | abrupt |

| Kagoshima, Japan | Indo-Australian/Indian-Indochina/East Asian monsoon | Jun 10[45] | October | abrupt |

| Seoul, South Korea | Indo-Australian/Indian-Indochina/East Asian monsoon | July 10[45] | September | abrupt |

| Beijing, China | Indo-Australian/Indian-Indochina/East Asian monsoon | July 20[45] | September | abrupt |

| Darwin, Australia | Indo-Australian/Borneo-Australian/Australian monsoon | Oct[44] | April[44] | persistent |

Africa (West African and Southeast African)

[edit]

The monsoon of western Sub-Saharan Africa is the result of the seasonal shifts of the Intertropical Convergence Zone and the great seasonal temperature and humidity differences between the Sahara and the equatorial Atlantic Ocean.[46] The ITCZ migrates northward from the equatorial Atlantic in February, reaches western Africa on or near June 22, then moves back to the south by October.[43] The dry, northeasterly trade winds, and their more extreme form, the harmattan, are interrupted by the northern shift in the ITCZ and resultant southerly, rain-bearing winds during the summer. The semiarid Sahel and Sudan depend upon this pattern for most of their precipitation.

North America

[edit]

The North American monsoon (NAM) occurs from late June or early July into September, originating over Mexico and spreading into the southwest United States by mid-July. It affects Mexico along the Sierra Madre Occidental as well as Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, West Texas and California. It pushes as far west as the Peninsular Ranges and Transverse Ranges of Southern California, but rarely reaches the coastal strip (a wall of desert thunderstorms only a half-hour's drive away is a common summer sight from the sunny skies along the coast during the monsoon). The North American monsoon is known to many as the Summer, Southwest, Mexican or Arizona monsoon.[47][48] It is also sometimes called the Desert monsoon as a large part of the affected area are the Mojave and Sonoran deserts. However, it is controversial whether the North and South American weather patterns with incomplete wind reversal should be counted as true monsoons.[49][50]

Asia

[edit]The Asian monsoons may be classified into a few sub-systems, such as the Indian Subcontinental Monsoon which affects the Indian subcontinent and surrounding regions including Nepal, and the East Asian Monsoon which affects southern China, Taiwan, Korea and parts of Japan.

South Asian monsoon

[edit]Southwest monsoon

[edit]

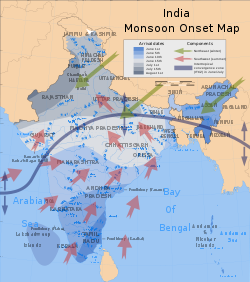

The southwestern summer monsoons occur from June to September. The Thar Desert and adjoining areas of the northern and central Indian subcontinent heat up considerably during the hot summers. This causes a low pressure area over the northern and central Indian subcontinent. To fill this void, the moisture-laden winds from the Indian Ocean rush into the subcontinent. These winds, rich in moisture, are drawn towards the Himalayas. The Himalayas act like a high wall, blocking the winds from passing into Central Asia, and forcing them to rise. As the clouds rise, their temperature drops, and precipitation occurs. Some areas of the subcontinent receive up to 10,000 mm (390 in) of rain annually.

The southwest monsoon is generally expected to begin between the end of May and beginning of June and fade away between the end of September and start of October. The moisture-laden winds on reaching the southernmost point of the Indian Peninsula, due to its topography, become divided into two parts: the Arabian Sea Branch and the Bay of Bengal Branch.

The Arabian Sea Branch of the Southwest Monsoon first hits the Western Ghats of the coastal state of Kerala, India, thus making this area the first state in India to receive rain from the Southwest Monsoon. This branch of the monsoon moves northwards along the Western Ghats (Konkan and Goa) with precipitation on coastal areas, west of the Western Ghats. The eastern areas of the Western Ghats do not receive much rain from this monsoon as the wind does not cross the Western Ghats.

The Bay of Bengal Branch of Southwest Monsoon flows over the Bay of Bengal heading towards north-east India and Bengal, picking up more moisture from the Bay of Bengal. The winds arrive at the Eastern Himalayas with large amounts of rain. Mawsynram, situated on the southern slopes of the Khasi Hills in Meghalaya, India, is one of the wettest places on Earth. After the arrival at the Eastern Himalayas, the winds turns towards the west, travelling over the Indo-Gangetic Plain at a rate of roughly 1–2 weeks per state,[51] pouring rain all along its way. June 1 is regarded as the date of onset of the monsoon in India, as indicated by the arrival of the monsoon in the southernmost state of Kerala.

The monsoon accounts for nearly 80% of the rainfall in India.[52][53] Indian agriculture (which accounts for 25% of the GDP and employs 70% of the population) is heavily dependent on the rains, for growing crops especially like cotton, rice, oilseeds and coarse grains. A delay of a few days in the arrival of the monsoon can badly affect the economy, as evidenced in the numerous droughts in India in the 1990s.

The monsoon is widely welcomed and appreciated by city-dwellers as well, for it provides relief from the climax of summer heat in June.[54] However, the roads take a battering every year. Often houses and streets are waterlogged and slums are flooded despite drainage systems. A lack of city infrastructure coupled with changing climate patterns causes severe economic loss including damage to property and loss of lives, as evidenced in the 2005 flooding in Mumbai that brought the city to a standstill. Bangladesh and certain regions of India like Assam and West Bengal, also frequently experience heavy floods during this season. Recently, areas in India that used to receive scanty rainfall throughout the year, like the Thar Desert, have surprisingly ended up receiving floods due to the prolonged monsoon season.

The influence of the Southwest Monsoon is felt as far north as in China's Xinjiang. It is estimated that about 70% of all precipitation in the central part of the Tian Shan Mountains falls during the three summer months, when the region is under the monsoon influence; about 70% of that is directly of "cyclonic" (i.e., monsoon-driven) origin (as opposed to "local convection").[55] The effects also extend westwards to the Mediterranean, where however the impact of the monsoon is to induce drought via the Rodwell-Hoskins mechanism.[56]

Northeast monsoon

[edit]

Around September, with the sun retreating south, the northern landmass of the Indian subcontinent begins to cool off rapidly, and air pressure begins to build over northern India. The Indian Ocean and its surrounding atmosphere still hold their heat, causing cold wind to sweep down from the Himalayas and Indo-Gangetic Plain towards the vast spans of the Indian Ocean south of the Deccan peninsula. This is known as the Northeast Monsoon or Retreating Monsoon.

While travelling towards the Indian Ocean, the cold dry wind picks up some moisture from the Bay of Bengal and pours it over peninsular India and parts of Sri Lanka. Cities like Chennai, which get less rain from the Southwest Monsoon, receive rain from this Monsoon. About 50% to 60% of the rain received by the state of Tamil Nadu is from the Northeast Monsoon.[57] In Southern Asia, the northeastern monsoons take place from October to December when the surface high-pressure system is strongest.[58] The jet stream in this region splits into the southern subtropical jet and the polar jet. The subtropical flow directs northeasterly winds to blow across southern Asia, creating dry air streams which produce clear skies over India. Meanwhile, a low pressure system known as a monsoon trough develops over South-East Asia and Australasia and winds are directed toward Australia. In the Philippines, northeast monsoon is called Amihan.[59]

East Asian monsoon

[edit]

The East Asian monsoon affects large parts of Indochina, the Philippines, China, Taiwan, Korea, Japan, and Siberia. It is characterised by a warm, rainy summer monsoon and a cold, dry winter monsoon. The rain occurs in a concentrated belt that stretches east–west except in East China where it is tilted east-northeast over Korea and Japan. The seasonal rain is known as Meiyu in China, Jangma in Korea, and Bai-u in Japan, with the latter two resembling frontal rain.

The onset of the summer monsoon is marked by a period of premonsoonal rain over South China and Taiwan in early May. From May through August, the summer monsoon shifts through a series of dry and rainy phases as the rain belt moves northward, beginning over Indochina and the South China Sea (May), to the Yangtze River Basin and Japan (June) and finally to northern China and Korea (July). When the monsoon ends in August, the rain belt moves back to southern China.

Australia

[edit]

The rainy season occurs from September to February and it is a major source of energy for the Hadley circulation during boreal winter. It is associated with the development of the Siberian High and the movement of the heating maxima from the Northern Hemisphere to the Southern Hemisphere. North-easterly winds flow down Southeast Asia, are turned north-westerly/westerly by Borneo topography towards Australia. This forms a cyclonic circulation vortex over Borneo, which together with descending cold surges of winter air from higher latitudes, cause significant weather phenomena in the region. Examples are the formation of a rare low-latitude tropical storm in 2001, Tropical Storm Vamei, and the devastating flood of Jakarta in 2007.

The onset of the monsoon over Australia tends to follow the heating maxima down Vietnam and the Malay Peninsula (September), to Sumatra, Borneo and the Philippines (October), to Java, Sulawesi (November), Irian Jaya and northern Australia (December, January). However, the monsoon is not a simple response to heating but a more complex interaction of topography, wind and sea, as demonstrated by its abrupt rather than gradual withdrawal from the region. The Australian monsoon (the "Wet") occurs in the southern summer when the monsoon trough develops over Northern Australia. Over three-quarters of annual rainfall in Northern Australia falls during this time.

Europe

[edit]The European Monsoon (more commonly known as the return of the westerlies) is the result of a resurgence of westerly winds from the Atlantic, where they become loaded with wind and rain.[60] These westerly winds are a common phenomenon during the European winter, but they ease as spring approaches in late March and through April and May. The winds pick up again in June, which is why this phenomenon is also referred to as "the return of the westerlies".[61]

The rain usually arrives in two waves, at the beginning of June, and again in mid- to late June. The European monsoon is not a monsoon in the traditional sense in that it doesn't meet all the requirements to be classified as such. Instead, the return of the westerlies is more regarded as a conveyor belt that delivers a series of low-pressure centres to Western Europe where they create unsettled weather. These storms generally feature significantly lower-than-average temperatures, fierce rain or hail, thunder, and strong winds.[62]

The return of the westerlies affects Europe's Northern Atlantic coastline, more precisely Ireland, Great Britain, the Benelux countries, western Germany, northern France and parts of Scandinavia.

See also

[edit]- Monsoon (photographs) – New Zealand photographer (1927–1988)

- Tropical monsoon climate

- North American monsoon

References

[edit]- ^ Ramage, C. (1971). Monsoon Meteorology. International Geophysics Series. Vol. 15. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- ^ "Welcome to Monsoon Season – Why You Probably Are Using This Term Wrong". 29 June 2016. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016.

- ^ "Definition of Monsoon". 28 July 2016. Archived from the original on 19 July 2016.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology (June 2000). "Monsoon". American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2008-03-22. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

- ^ International Committee of the Third Workshop on Monsoons. The Global Monsoon System: Research and Forecast. Archived 2008-04-08 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2008-03-16.

- ^ Wang, Pinxian; Clemens, Steven; Tada, Ryuji; Murray, Richard (2019). "Blowing in the Monsoon Wind". Oceanography. 32 (1): 48. Bibcode:2019Ocgpy..32a..48W. doi:10.5670/oceanog.2019.119. ISSN 1042-8275.

- ^ "monsoon, n." OED Online. June 2018. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ^ Zhisheng, An; Kutzbach, John E.; Prell, Warren L.; Porter, Stephen C. (2001). "Evolution of Asian monsoons and phased uplift of the Himalaya–Tibetan plateau since Late Miocene times". Nature. 411 (6833): 62–66. Bibcode:2001Natur.411...62Z. doi:10.1038/35075035. PMID 11333976. S2CID 4398615.

- ^ P. D. Clift, M. K. Clark, and L. H. Royden. An Erosional Record of the Tibetan Plateau Uplift and Monsoon Strengthening in the Asian Marginal Seas. Archived 2008-05-27 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2008-05-11.

- ^ Integrated Ocean Drilling Program. Earth, Oceans, and Life. Archived 2007-10-26 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2008-05-11.

- ^ Gupta, A. K.; Thomas, E. (2003). "Initiation of Northern Hemisphere glaciation and strengthening of the northeast Indian monsoon: Ocean Drilling Program Site 758, eastern equatorial Indian Ocean" (PDF). Geology. 31 (1): 47–50. Bibcode:2003Geo....31...47G. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(2003)031<0047:IONHGA>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Wang, Zhenjun; Chen, Shitao; Wang, Yongjin; Cheng, Hai; Liang, Yijia; Yang, Shaohua; Zhang, Zhenqiu; Zhou, Xueqin; Wang, Meng (1 March 2020). "Sixty-year quasi-period of the Asian monsoon around the Last Interglacial derived from an annually resolved stalagmite δ18O record". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 541 109545. Bibcode:2020PPP...54109545W. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2019.109545. S2CID 214283369. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ Srinivasan, M. S.; Sinha, D. K. (2000). "Ocean circulation in the tropical Indo-Pacific during early Pliocene (5.6–4.2 Ma): Paleobiogeographic and isotopic evidence". Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences - Earth and Planetary Sciences. 109 (3): 315–328. Bibcode:2000JESS..109..315S. doi:10.1007/BF03549815. ISSN 0253-4126. S2CID 127257455.

- ^ Gebregiorgis, D.; Hathorne, E. C.; Giosan, L.; Clemens, S.; Nürnberg, D.; Frank, M. (8 November 2018). "Southern Hemisphere forcing of South Asian monsoon precipitation over the past ~1 million years". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 4702. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.4702G. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-07076-2. PMC 6224551. PMID 30410007.

- ^ Ma, Qingfeng; Zhu, Liping; Lü, Xinmiao; Wang, Junbo; Ju, Jianting; Kasper, Thomas; Daut, Gerhard; Haberzettl, Torsten (March 2019). "Late glacial and Holocene vegetation and climate variations at Lake Tangra Yumco, central Tibetan Plateau". Global and Planetary Change. 174: 16–25. Bibcode:2019GPC...174...16M. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2019.01.004. S2CID 134300820. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Peng, Xu; Chen, Yixin; Li, Yingkui; Liu, Beibei; Liu, Qing; Yang, Weilin; Cui, Zhijiu; Liu, Gengnian (April 2020). "Late Holocene glacier fluctuations in the Bhutanese Himalaya". Global and Planetary Change. 187 103137. Bibcode:2020GPC...18703137P. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2020.103137. S2CID 213557014. Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- ^ a b Liu, Chang; Clift, Peter D.; Giosan, Liviu; Miao, Yunfa; Warny, Sophie; Wan, Shiming (1 July 2019). "Paleoclimatic evolution of the SW and NE South China Sea and its relationship with spectral reflectance data over various age scales". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 525: 25–43. Bibcode:2019PPP...525...25L. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2019.02.019. S2CID 135413974. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ Matsuzaki, Kenji M.; Ikeda, Masayuki; Tada, Ryuji (20 July 2022). "Weakened pacific overturning circulation, winter monsoon dominance and tectonism re-organized Japan Sea paleoceanography during the Late Miocene global cooling". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 11396. Bibcode:2022NatSR..1211396M. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-15441-x. PMC 9300741. PMID 35859095.

- ^ a b Han, Wenxia; Fang, Xiaomin; Berger, André; Yin, Qiuzhen (22 December 2011). "An astronomically tuned 8.1 Ma eolian record from the Chinese Loess Plateau and its implication on the evolution of Asian monsoon". Journal of Geophysical Research. 116 (D24): 1–13. Bibcode:2011JGRD..11624114H. doi:10.1029/2011JD016237. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ Igarashi, Yaeko; Irino, Tomohisa; Sawada, Ken; Song, Lu; Furota, Satoshi (April 2018). "Fluctuations in the East Asian monsoon recorded by pollen assemblages in sediments from the Japan Sea off the southwestern coast of Hokkaido, Japan, from 4.3 Ma to the present". Global and Planetary Change. 163: 1–9. Bibcode:2018GPC...163....1I. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2018.02.001. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ Gallagher, Stephen J.; Kitamura, Akihisa; Iryu, Yasufumi; Itaki, Takuya; Koizumi, Itaru; Hoiles, Peter W. (27 June 2015). "The Pliocene to recent history of the Kuroshio and Tsushima Currents: a multi-proxy approach". Progress in Earth and Planetary Science. 2 17. Bibcode:2015PEPS....2...17G. doi:10.1186/s40645-015-0045-6. hdl:11343/57355. S2CID 129045722.

- ^ Kim, Yongmi; Yi, Sangheon; Kim, Gil-Young; Lee, Eunmi; Kong, Sujin (15 April 2019). "Palynological study of paleoclimate and paleoceanographic changes in the Eastern South Korea Plateau, East Sea, during the Plio-Pleistocene climate transition". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 520: 18–29. Bibcode:2019PPP...520...18K. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2019.01.021. S2CID 134641370. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ^ Vats, Nishant; Mishra, Sibasish; Singh, Raj K.; Gupta, Anil K.; Pandey, D. K. (June 2020). "Paleoceanographic changes in the East China Sea during the last ~400 kyr reconstructed using planktic foraminifera". Global and Planetary Change. 189 103173. Bibcode:2020GPC...18903173V. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2020.103173. S2CID 216428856. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ a b Ahn, Jinho; Brooks, Edward J.; Schmittner, Andreas; Kreutz, Karl (28 September 2012). "Abrupt change in atmospheric CO2 during the last ice age". Geophysical Research Letters. 39 (18) 2012GL053018: 1–5. Bibcode:2012GeoRL..3918711A. doi:10.1029/2012GL053018. S2CID 15020102.

- ^ Li, Qin; Wu, Haibin; Yu, Yanyan; Sun, Aizhi; Marković, Slobodan B.; Guo, Zhengtang (October 2014). "Reconstructed moisture evolution of the deserts in northern China since the Last Glacial Maximum and its implications for the East Asian Summer Monsoon". Global and Planetary Change. 121: 101–112. Bibcode:2014GPC...121..101L. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2014.07.009. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ Piao, Jinling; Chen, Wen; Wang, Lin; Pausata, Francesco S.R.; Zhang, Qiong (January 2020). "Northward extension of the East Asian summer monsoon during the mid-Holocene". Global and Planetary Change. 184 103046. Bibcode:2020GPC...18403046P. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2019.103046. S2CID 210319430. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ^ Wang, Wei; Liu, Lina; Li, Yanyan; Niu, Zhimei; He, Jiang; Ma, Yuzhen; Mensing, Scott A. (15 August 2019). "Pollen reconstruction and vegetation dynamics of the middle Holocene maximum summer monsoon in northern China". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 528: 204–217. Bibcode:2019PPP...528..204W. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2019.05.023. S2CID 182641708. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ Chen, Xu; McGowan, Suzanne; Xiao, Xiayun; Stevenson, Mark A.; Yang, Xiangdong; Li, Yanling; Zhang, Enlou (1 August 2018). "Direct and indirect effects of Holocene climate variations on catchment and lake processes of a treeline lake, SW China". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 502: 119–129. Bibcode:2018PPP...502..119C. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2018.04.027. S2CID 135099188. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ Cheng, Bei; Liu, Jianbao; Chen, Shengqian; Zhang, Zhiping; Shen, Zhongwei; Yan, Xinwei; Li, Fanyi; Chen, Guangjie; Zhang, Xiaosen; Wang, Xin; Chen, Jianhui (5 February 2020). "Impact of Abrupt Late Holocene Monsoon Climate Change on the Status of an Alpine Lake in North China". Journal of Geophysical Research. 125 (4) e2019JD031877. Bibcode:2020JGRD..12531877C. doi:10.1029/2019JD031877. S2CID 214431404. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- ^ Cheng, Ying; Liu, Hongyan; Dong, Zhibao; Duan, Keqin; Wang, Hongya; Han, Yue (April 2020). "East Asian summer monsoon and topography co-determine the Holocene migration of forest-steppe ecotone in northern China". Global and Planetary Change. 187 103135. Bibcode:2020GPC...18703135C. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2020.103135. S2CID 213786940. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ D. K. Sinha; A. K. Singh & M. Tiwari (2006-05-25). "Palaeoceanographic and palaeoclimatic history of ODP site 763A (Exmouth Plateau), South-east Indian Ocean: 2.2 Ma record of planktic foraminifera". Current Science. 90 (10): 1363–1369. JSTOR 24091985.

- ^ "Sea breeze – definition of sea breeze by The Free Dictionary". TheFreeDictionary.com.

- ^ Gadgil, Sulochana (2018). "The monsoon system: Land–sea breeze or the ITCZ?". Journal of Earth System Science. 127 (1) 1. doi:10.1007/s12040-017-0916-x. ISSN 0253-4126.

- ^ Chou, C. (2003). "Land-sea heating contrast in an idealized Asian summer monsoon". Climate Dynamics. 21 (1): 11–25. Bibcode:2003ClDy...21...11C. doi:10.1007/s00382-003-0315-7. ISSN 0930-7575. S2CID 53701462.

- ^ "Liquids and Fluids – Specific Heats". Archived from the original on 2007-08-09. Retrieved 2012-10-01.

- ^ "Solids – Specific Heats". Archived from the original on 2012-09-22. Retrieved 2012-10-01.

- ^ "Monsoon". Britannica. Archived from the original on 2007-10-13. Retrieved 2007-05-15.

- ^ Dr. Michael Pidwirny (2008). CHAPTER 8: Introduction to the Hydrosphere (e). Cloud Formation Processes. Archived 2008-12-20 at the Wayback Machine Physical Geography. Retrieved on 2009-01-01.

- ^ Bart van den Hurk and Eleanor Blyth (2008). Global maps of Local Land–Atmosphere coupling. Archived 2009-02-25 at the Wayback Machine KNMI. Retrieved on 2009-01-02.

- ^ Robert Penrose Pearce (2002). Meteorology at the Millennium. Archived 2016-04-27 at the Wayback Machine Academic Press, p. 66. ISBN 978-0-12-548035-2. Retrieved on 2009-01-02.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology (June 2000). "Gust Front". American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2011-05-05. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- ^ a b "Southwest Monsoon 2017 Forecast: Warmer-Than-Average Conditions Could Lead to More Storms". 2 June 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-06-06. Retrieved 2017-06-06.

- ^ a b c Innovations Report. Monsoon in West Africa: Classic continuity hides a dual-cycle rainfall regime. Archived 2011-09-19 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2008-05-25.

- ^ a b c d e "West African monsoon". Archived from the original on 2016-06-25. Retrieved 2017-06-06.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "Indian monsoon | meteorology". Archived from the original on 2016-08-01. Retrieved 2017-06-06.

- ^ African Monsoon Multidisciplinary Analyses (AMMA). "Characteristics of the West African Monsoon". AMMA. Archived from the original on July 12, 2007. Retrieved 2009-10-15.

- ^ Arizona State University Department of Geography. Basics of Arizona Monsoon. Archived 2009-05-31 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2008-02-29.

- ^ New Mexico Tech. Lecture 17: 1. North American Monsoon System. Retrieved on 2008-02-29. Archived October 30, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Rohli, Robert V.; Vega, Anthony J. (2011). Climatology. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 187. ISBN 978-0763791018. Archived from the original on 2013-06-19. Retrieved 2011-07-23.

Although the North American monsoon region experiences pronounced precipitation seasonally, it differs from a true monsoon, which is characterized by a distinct seasonal reversal of prevailing surface winds. No such situation occurs in [North America]

- ^ Cook, Ben; Seager, Richard. "The Future of the North American Monsoon".

- ^ Explore, Team (2005). Weather and Climate: India in Focus. EdPower21 Education Solutions. p. 28.

- ^ Ahmad, Latief; Kanth, Raihana Habib; Parvaze, Sabah; Mahdi, Syed Sheraz (2017). Experimental Agrometeorology: A Practical Manual. Springer. p. 121. ISBN 978-3-319-69185-5.

- ^ "Why India's Twin Monsoons Are Critical To Its Well-Being | The Weather Channel". The Weather Channel. Archived from the original on 2018-09-05. Retrieved 2018-09-05.

- ^ Official Web Site of District Sirsa, India. District Sirsa. Archived 2010-12-28 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2008-12-27.

- ^ Blumer, Felix P. (1998). "Investigations of the precipitation conditions in the central part of the Tianshan mountains". In Kovar, Karel (ed.). Hydrology, water resources and ecology in headwaters. Volume 248 of IAHS publication (PDF). International Association of Hydrological Sciences. pp. 343–350. ISBN 978-1-901502-45-9.

- ^ Rodwell, Mark J.; Hoskins, Brian J. (1996). "Monsoons and the dynamics of deserts". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. 122 (534): 1385–1404. Bibcode:1996QJRMS.122.1385R. doi:10.1002/qj.49712253408. ISSN 1477-870X.

- ^ "NORTHEAST MONSOON". Archived from the original on 2015-12-29. Retrieved 2011-11-07.

- ^ Robert V. Rohli; Anthony J. Vega (2007). Climatology. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-7637-3828-0. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- ^ Arceo, Acor (2023-10-20). "Philippines' northeast monsoon season underway". RAPPLER. Retrieved 2024-01-06.

- ^ Visser, S.W. (1953). Some remarks on the European monsoon. Birkhäuser: Basel.

- ^ Leo Hickman (2008-07-09). "The Question: What is the European monsoon?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2013-09-02. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- ^ Paul Simons (2009-06-07). "'European Monsoon' to blame for cold and rainy start to June". The Times. Archived from the original on 2011-06-04. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

Further reading

[edit]- Chang, C.P., Wang, Z., Hendon, H., 2006, The Asian Winter Monsoon. The Asian Monsoon, Wang, B. (ed.), Praxis, Berlin, pp. 89–127.

- International Committee of the Third Workshop on Monsoons. The Global Monsoon System: Research and Forecast.

External links

[edit]Monsoon

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Definition and Characteristics

A monsoon is defined as a seasonal reversal in the prevailing wind direction over large continental areas, typically leading to distinct wet and dry seasons characterized by heavy rainfall during the summer phase. This phenomenon arises primarily from differential heating between landmasses and adjacent oceans, where warmer land draws in moist air from the sea, resulting in prolonged periods of precipitation.[2][5] Key characteristics of monsoons include persistent, large-scale wind shifts, such as from northeast trades in winter to southwest flows in summer over regions like South Asia, which facilitate the influx of moisture-laden air. These systems are closely associated with the intertropical convergence zone (ITCZ), a band of low pressure where trade winds from both hemispheres converge, enhancing convective activity and rainfall. Monsoon seasons generally last 3 to 6 months, with the wet phase delivering the majority of annual precipitation—in many affected areas, exceeding 70% of the total yearly rainfall.[2][5][6] Unlike steady global circulation patterns such as the trade winds, which blow consistently from the northeast or southeast throughout the year, or the westerlies that dominate mid-latitudes, monsoons feature dramatic, predictable reversals tied to seasonal solar heating over continents rather than year-round ocean-driven flows. They are primarily distributed in tropical and subtropical zones worldwide, generally from about 20°S to 40°N, influencing diverse regions including parts of Asia, Africa, Australia, and the Americas, and directly affecting more than half of the world's population through their impacts on water availability and agriculture.[5][7][8]Etymology

The term "monsoon" derives from the Portuguese "monção," which traces back to the Arabic "mawsim," signifying "season" or a marked time of year, particularly the favorable period for navigation.[9][2] This linguistic root emerged among Arabic navigators describing the reliable seasonal wind shifts in the Indian Ocean, later adopted by Portuguese explorers in the 16th century during their voyages to India and the East Indies, where the winds enabled predictable maritime routes from April to October.[10][11] The word spread to other European languages through colonial trade networks, entering Dutch as "monson" and English by the 1580s to denote these alternating trade winds, initially focused on their utility for sailing rather than precipitation.[9] In regional contexts, parallel terms developed independently; for instance, Hindi "barsaat" refers to the rainy season tied to these winds, derived from Sanskrit roots meaning "raining night" or seasonal downpour.[12][13] By the 18th century, English usage had expanded to include the heavy rains accompanying the winds in India, reflecting observations by figures like Edmund Halley, who mapped the patterns in 1686.[9][10] In the 19th century, as meteorology formalized, "monsoon" transitioned from a navigational descriptor to a scientific term encompassing large-scale, seasonal atmospheric circulations driven by land-sea temperature contrasts, influenced by early systematic studies from Alexander von Humboldt in 1817 and the establishment of the Indian Meteorological Department in 1875.[10] This evolution distinguished it from earlier, more localized references to seasonal winds in ancient texts like the Rigveda.[10] Distinct from the wind pattern itself, the related concept of "monsoonal climate" in the Köppen-Geiger classification identifies regions with pronounced wet summers and dry winters, specifically under subtypes Cwa (humid subtropical with hot summers) and Cwb (subtropical highland with warm summers), where seasonal reversals dominate precipitation regimes.[14][15]Mechanisms

Driving Forces

The primary driver of monsoon systems is the seasonal land-sea thermal contrast, where continental surfaces heat more rapidly than adjacent oceans during summer due to differences in specific heat capacity and albedo. This differential heating establishes low-pressure cells over landmasses, drawing moist maritime air inland and initiating convective rainfall. For instance, the intense solar heating over the Tibetan Plateau generates a prominent thermal low, which enhances the pressure gradient and promotes monsoon circulation.[16][17] Large-scale atmospheric circulations, including the Hadley cells and associated jet streams, further amplify monsoon dynamics by facilitating the poleward transport of heat and moisture. The Hadley cells, characterized by rising motion in the tropics and subsidence in the subtropics, shift seasonally, with subtropical high-pressure systems migrating to allow influx of moist air from ocean basins toward continental lows. This process is governed by the atmospheric momentum equation, which in vector form expresses the pressure gradient as , where is air density, is velocity, is the Coriolis parameter, and is geopotential; during monsoon onset, this approximates geostrophic balance where the Coriolis force counters the pressure gradient, sustaining strong cross-equatorial flows.[18][19][20] Orographic features exacerbate monsoon precipitation through forced ascent of incoming moist air. Mountain barriers, such as the Himalayas, compel air masses to rise adiabatically, leading to condensation and enhanced orographic rainfall. The Tibetan Plateau, with elevations exceeding 4 km, acts as a elevated heat source that intensifies surface sensible heating and thereby strengthens the overlying thermal low, amplifying regional monsoon intensity.[21][22] The migration of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) provides a key thermodynamic framework for monsoon convergence. This zone of low-level air mass convergence shifts annually by approximately 20–25° latitude, following the solar zenith and aligning with continental thermal lows to concentrate moisture transport and upward motion over monsoon regions.[19][23]Seasonal Dynamics

The seasonal dynamics of monsoons involve a cyclical progression through onset, active, and withdrawal phases, driven by the interplay of atmospheric circulation and moisture transport. In the South Asian summer monsoon, onset typically begins around early June over the southern peninsula, with northward advancement completing coverage of the region by mid-July, leading to a sharp increase in rainfall and low-level wind reversal.[24] The active phase peaks during July and August, delivering the bulk of seasonal precipitation, though it features intermittent breaks in rainfall. Withdrawal occurs gradually from September through early October, as continental cooling diminishes the moisture influx.[25] These phases are initiated by seasonal land-sea thermal contrasts that establish the large-scale pressure gradients.[26] A hallmark of monsoon dynamics is the reversal of prevailing winds, shifting from dry northeasterlies in winter—originating from continental high-pressure systems—to moisture-laden southerlies in summer that cross the equator and bring oceanic vapor inland. This reversal arises as the Intertropical Convergence Zone migrates northward, prompting cross-equatorial flow from the Southern Hemisphere; the Coriolis effect then deflects this airflow to the right in the Northern Hemisphere, resulting in southwesterly winds over the region.[25] Intra-seasonal variability manifests as alternating active and break spells, often lasting several days to weeks, which disrupt the steady rainfall during the active phase. These spells are primarily caused by the westward propagation of Rossby waves, where anomalous vorticity patterns move from the Bay of Bengal into central and northwest India, suppressing convection and initiating breaks. The phase speed of these Rossby waves is approximated by the equation where represents the planetary vorticity gradient (the meridional derivative of the Coriolis parameter) and is the zonal wavenumber; this yields westward propagation characteristic of the breaks.[27] Additionally, the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO) modulates these dynamics on 30- to 60-day cycles, enhancing or suppressing convective activity and thereby influencing the timing and intensity of active periods within the season.[28] On longer timescales, interannual cycles like the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) exert significant influence, with El Niño events typically weakening the Asian monsoon by reducing rainfall by 10-20% through altered Walker circulation and suppressed convection.[29]Historical Development

Early Observations

Ancient civilizations in the Indian subcontinent documented seasonal rains through mythological narratives in the Rigveda, composed around 1500 BCE, where the Maruts are depicted as storm gods accompanying Indra to release waters and bring monsoon-like downpours essential for fertility. In parallel, Chinese oracle bone inscriptions from the Shang Dynasty, dating to approximately 1600 BCE, record summer floods in the Yellow River basin, attributing them to heavy seasonal precipitation that necessitated multiple capital relocations due to inundation.[30] Maritime traders recognized the predictability of these winds for navigation. By the 8th century, Arab merchants in the Indian Ocean referred to the seasonal shifts as mawsim, timing their dhow voyages to coincide with the reliable monsoon patterns that facilitated safe passage between East Africa, Arabia, and India.[31] This knowledge was later leveraged by European explorers; in 1498, Vasco da Gama's fleet exploited the northeast monsoon winds, guided by an Arab navigator, to cross from East Africa to the Malabar Coast, establishing a direct sea route to India.[32] Indigenous communities integrated monsoon cycles into their cultural lore. Australian Aboriginal groups, such as the Yanyuwa in northern Australia, observed wet and dry seasons through environmental indicators like wind directions and plant behaviors, embedding these patterns in creation stories that guided resource management across monsoonal regions.[33] A key early textual account appears in the 1st century AD Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, an anonymous Greek merchant's guide that details the southwest monsoon enabling direct voyages from the Red Sea to India's west coast, starting around July, while the return used northeast winds, underscoring the winds' role in structuring ancient trade networks.[34] These observations laid anecdotal foundations that later informed systematic meteorological studies in the 19th century.Scientific Understanding

In the 19th century, foundational work on monsoon dynamics began with observations linking regional topography and seasonal snow cover to rainfall variability in India. Henry Blanford, a British meteorologist serving with the India Meteorological Department, proposed in the 1870s that reduced Himalayan snowfall during winter and spring led to weaker summer monsoons by diminishing moisture availability and altering atmospheric circulation patterns.[35] This insight, detailed in his 1884 paper, enabled early seasonal drought forecasts, such as the successful prediction of deficient rainfall in 1885 based on low snow observations.[36] Building on these empirical foundations, Gilbert Walker advanced monsoon understanding in the early 20th century through global pressure analyses. As director of the India Meteorological Department from 1904 to 1920, Walker identified the Southern Oscillation in the 1920s, a large-scale seesaw in atmospheric pressure between the eastern and western equatorial Pacific that inversely correlated with Indian summer monsoon rainfall—high pressure in the east typically weakened the monsoon.[37] His datasets from the 1920s revealed an inverse pressure correlation between India and parts of Africa, where high pressures over the equatorial South Atlantic and Africa coincided with low pressures over India, foreshadowing later links between the Southern Oscillation and monsoon variability akin to ENSO influences.[38] Early theoretical frameworks for monsoons emerged even earlier, with Edmond Halley's 1686 treatise analogizing monsoon winds to an amplified land-sea breeze driven by differential heating between continents and oceans.[39] This thermal concept was modernized in the mid-20th century through numerical modeling; T. N. Krishnamurti's simulations in the 1960s and 1970s used primitive equation models to replicate the seasonal migration of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), demonstrating how land-ocean contrasts propelled monsoon circulations in tropical regions.[40] Key milestones in the mid-20th century included the recognition of elevated heat sources in Asia. In the 1940s, German meteorologist Hermann Flohn identified the Tibetan Plateau as a massive summer heat low, where intense solar heating generated upper-level divergence that strengthened the South Asian monsoon trough and cross-equatorial flows.[41] This concept was empirically validated during the 1970s through the Global Atmospheric Research Program (GARP), particularly the Monsoon Experiment (MONEX) under the First GARP Global Experiment (FGGE) in 1978–1979, which deployed aircraft, ships, and buoys to confirm robust cross-equatorial low-level winds from the Southern to Northern Hemisphere, sustaining the Indian Ocean monsoon circulation.[42]Regional Variations

Asian Monsoons

The Asian monsoons, encompassing the South Asian and East Asian subtypes, represent the most extensive and influential monsoon systems globally, affecting over half the world's population through their seasonal rainfall patterns. These systems drive agriculture, water resources, and economies across the continent, with the South Asian monsoon delivering approximately 80% of India's annual precipitation during its active period.[43] Regions affected by the Asian monsoon, such as central Myanmar and eastern India (e.g., Odisha), experience less extreme heat than arid deserts like Death Valley, Turpan, or Middle Eastern deserts. This is due to seasonal monsoon rains providing moisture, supporting vegetation cover, and offering occasional cooling, which prevents the development of completely dry-heat conditions typical of persistent arid environments. The East Asian monsoon, meanwhile, contributes a significant 40-60% of annual rainfall in regions including China, Japan, and Korea, shaping their hydrological cycles and flood risks.[44] Both subtypes exhibit pronounced variability, influenced by regional geography and ocean-atmosphere interactions, leading to events that have historically altered human settlements and triggered disasters. Recent extremes, such as the 2024-2025 monsoon floods across South and Southeast Asia, have resulted in numerous fatalities and widespread displacement, underscoring ongoing variability.[45] The South Asian monsoon, often termed the Indian monsoon, is characterized by southwest winds prevailing from June to September, transporting moisture northward from the Indian Ocean. Rainfall during this period typically ranges from 700 to 3000 mm across the subcontinent, with higher amounts in the Himalayan foothills (up to 1800 mm in peak seasons) due to orographic lift as moist air ascends the mountain barriers.[43] The Bay of Bengal serves as a primary moisture source, where converging winds enhance precipitation through low-level convergence and convective activity.[46] Variability in this system can be extreme; for instance, the weak monsoon of 1877 resulted in severe rainfall failure, contributing to the Great Famine that affected over 5 million people in India due to crop shortfalls and inadequate response.[47] In contrast, excessive rainfall events, such as the 2005 Mumbai floods, saw 942 mm fall in 24 hours, overwhelming urban infrastructure and causing over 500 deaths.[48] The East Asian monsoon features summer southerlies drawing moisture from the Pacific Ocean and South China Sea, leading to a northward-migrating rainband that brings bimodal rainfall peaks—typically one in late June associated with the Mei-yu front over the Yangtze River valley and another in late July over northern China.[49] These southerlies are notably strong at low levels, exceeding those in other monsoon domains, and drive interannual fluctuations that result in floods or droughts across the region.[50] The Mei-yu front, a quasi-stationary boundary, intensifies precipitation through frontal lifting, particularly affecting Japan and Korea in early summer.[51] Historically, Asian monsoons have profoundly shaped civilizations; the ancient Indus Valley Civilization (circa 5300–3300 years BP) relied on robust summer monsoon rains for agriculture, with its expansion tied to wet phases and deurbanization linked to a weakening monsoon around 4100 years BP that reduced river flows and prompted eastward migrations.[52] The subtypes differ markedly: the South Asian monsoon is predominantly ocean-driven, reliant on Indian Ocean warmth and Bay of Bengal dynamics for moisture convergence, whereas the East Asian monsoon exhibits more continental characteristics, with rainfall modulated by land-sea thermal contrasts and frequent interactions with Pacific typhoons that amplify late-season precipitation.[53]African Monsoons

The West African monsoon is characterized by the seasonal northward migration of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) from approximately 5°N in late May to early June, advancing rapidly to around 20°N by late July or August, and persisting through October before retreating southward. This progression delivers the bulk of the region's annual precipitation, with totals ranging from 500 to 1500 mm across the Sahel, concentrating in intense bursts during July and August that account for 75-90% of yearly rainfall in these arid-influenced zones. Along the Guinea coast, the pattern exhibits bimodality, featuring two peaks—typically in May-June and September-October—due to the ITCZ's oscillatory movement influenced by local topography and coastal dynamics. The system is primarily driven by the Saharan heat low, a thermal depression forming over the desert that intensifies the land-sea temperature contrast, drawing moist southwesterly winds from the Atlantic and fostering low-level convergence.[54][55][55][54] In contrast, the Southeast African monsoon unfolds during the Southern Hemisphere summer from November to March, bringing easterly winds laden with moisture from the warm Indian Ocean that penetrate inland, primarily affecting Mozambique, eastern Zimbabwe, and Madagascar. These flows establish a diffuse convergence zone over the region, promoting convective rainfall that supports savanna ecosystems and seasonal agriculture, often enhanced by interactions with the East African Highlands. The Mascarene High, a persistent subtropical anticyclone centered around 20°S and 60°E off Madagascar's coast, plays a key role by strengthening during the austral winter to suppress southern convection, thereby facilitating the northward surge of moist air in summer and modulating the monsoon's intensity through its influence on cross-equatorial pressure gradients.[56][56][56] Rainfall variability in these systems profoundly shapes Sahel ecology, where shifts in monsoon strength can trigger widespread drought or flooding, altering vegetation patterns and water availability. The severe Sahel droughts of the 1970s and 1980s resulted in a roughly 30% decline in precipitation compared to prior wet decades, attributed to anomalous sea surface temperature patterns across the tropical Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans that weakened the meridional temperature gradient and displaced the ITCZ southward. Conversely, extreme wet events like the 2010 floods across West Africa—exacerbated by prolonged heavy monsoon rains—displaced over 2 million people in Nigeria alone and affected millions more in neighboring countries such as Niger and Chad, leading to crop destruction and humanitarian crises. More recently, in 2024, severe flooding across West and East Africa, influenced by El Niño, displaced millions and caused significant agricultural losses.[57][57][58][59][60] These monsoons underpin rainfed agriculture for approximately 60% of Africa's population, particularly in sub-Saharan regions where livelihoods hinge on seasonal rains, though the equatorial Congo Basin stands as a notable exception with its near-continuous precipitation regime decoupled from strict monsoon cycles.[57]North American Monsoon

The North American monsoon is a seasonal weather pattern characterized by a marked increase in rainfall from late June to early July, peaking through September and typically retreating by mid- to late September, primarily affecting the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico.[61] Its core region centers on the Sierra Madre Occidental mountain range in Mexico, extending northward into Arizona, New Mexico, and parts of Utah and Colorado, with moisture influences reaching into southern California and occasionally Central America as part of the broader American monsoon systems.[62] During this period, the monsoon delivers 150–500 mm of precipitation, largely sourced from evaporative moisture over the Gulf of California, which fuels widespread thunderstorms and contributes up to 50% of the annual rainfall in Arizona's desert regions.[63] The primary driving factors include the northward migration and westward expansion of the subtropical ridge, often associated with the Bermuda High, which shifts low-level winds to draw moist air from the Gulf of California and Gulf of Mexico into the region.[61] This process is augmented by interactions with mid-latitude troughs, where upper-level disturbances propagate around the monsoon ridge, enhancing convective instability and moisture influx.[64] Topographic features, such as the elevated terrain of the Sierra Madre Occidental, play a crucial role by lifting the moist air, promoting orographic precipitation and intensifying the seasonal shift from arid spring conditions to wet summers.[62] Rainfall exhibits significant variability, often occurring in pulses driven by "gulf surges"—episodic increases in low-level moisture transport from the Gulf of California, leading to clusters of intense, convective thunderstorms with diurnal cycles peaking in the late afternoon or nocturnally in lower deserts.[61] These surges can result in extreme events, such as the September 2014 floods in Arizona triggered by remnants of Hurricane Norbert, where some areas received over 300 mm of rain in a few days, causing widespread flash flooding in the Phoenix metropolitan region.[65] More recently, the 2024 monsoon season was below normal, exacerbating drought conditions in the Southwest and highlighting interannual fluctuations.[66] Interannual fluctuations are influenced by factors like sea surface temperatures in the eastern Pacific and large-scale circulation patterns, contributing to wetter or drier seasons. Unlike tropical monsoons, which rely on persistent land-sea thermal contrasts to drive steady southwesterly winds over vast oceanic fetches, the North American monsoon is more episodic and convective, with less consistent wind reversals due to the blocking effect of the Rocky Mountains, which inhibit westerly flow and allow subtropical influences to dominate.[64] This mid-latitude positioning integrates interactions between tropical moisture sources and extratropical dynamics, such as jet stream perturbations colliding with coastal topography, resulting in highly localized and variable precipitation rather than broad, stratiform rains.Australian Monsoon

The Australian monsoon is a seasonal weather pattern centered on the tropical north of the continent, particularly the Top End region encompassing the Northern Territory and northern Western Australia. It features persistent northwesterly winds originating from the Indian Ocean, blowing from late December to March, which transport moist air inland. These winds are driven by the maritime continent heat low, a region of low atmospheric pressure over Indonesia and surrounding seas that intensifies during the Southern Hemisphere summer, creating a monsoon trough that pulls humid air toward northern Australia. Rainfall during this period typically ranges from 1000 to 2000 mm in the Top End, transforming the arid landscape into lush, water-filled environments.[67] Variability in the Australian monsoon is significantly influenced by the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD), a climate oscillation that affects sea surface temperatures across the Indian Ocean and alters moisture availability. Positive IOD phases, characterized by cooler waters near Indonesia, often lead to delayed monsoon onset and reduced rainfall by weakening the northwesterly winds, while negative phases enhance moisture transport and result in wetter conditions. A notable example of monsoon intensity occurred in December 1974, when Severe Tropical Cyclone Tracy struck Darwin at the peak of the season, bringing extreme winds and heavy rain as part of an active monsoon burst. For instance, the negative IOD in 2023 led to above-average rainfall and flooding in northern Australia.[68][69][67][70] The shared Indian Ocean moisture sources also link the Australian monsoon briefly to broader Asian patterns.[67] Ecologically, the Australian monsoon plays a defining role in shaping the biomes of the Kimberley region in Western Australia and Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory, supporting savannas, wetlands, and seasonal rainforests through dramatic wet-dry cycles. The monsoon trough delivers 80-90% of northern Australia's annual rainfall, enabling the regeneration of vegetation, filling rivers and billabongs, and sustaining biodiversity in these fire-prone ecosystems. This heavy precipitation is essential for the growth of monsoon-dependent flora and fauna, preventing desertification and maintaining the region's unique tropical savanna characteristics.[67] In Indigenous Australian contexts, the monsoon aligns with the traditional "wet season" observed in Aboriginal calendars across northern communities, marking a time of abundant water, new plant growth, and cultural activities tied to the landscape's renewal. These calendars, such as those of the Bininj people in Kakadu (where it is called Kudjewk) or the Tiwi (Jamutakari), emphasize environmental cues like consistent northwest winds and rainfall to guide hunting, gathering, and ceremonial practices during this period.[71]South American Monsoon

The South American Monsoon System (SAMS) encompasses a vast domain covering approximately 45% of the continent, from the Amazon Basin to the La Plata River region, and is essential for sustaining the world's largest rainforest through its seasonal rainfall.[72] Active primarily from October to April during the austral summer, the system features low-level jets originating over the tropical Atlantic that transport moisture westward into the continent, delivering 2000–3000 mm of annual rainfall to the Amazon Basin.[73] These jets converge with easterly trade winds, fostering widespread convective activity, while the thermally induced Chaco low-pressure center over northern Argentina and Paraguay drives southerly winds that further enhance moisture convergence and precipitation across central and southeastern South America.[72] Distinct regional subtypes characterize the SAMS, including a pronounced summer precipitation maximum over the Central Brazilian Plateau, where intense surface heating triggers deep convection and peak rainfall from December to February.[73] Along the eastern Andes, orographic lift amplifies the monsoon's effects as Atlantic-derived moist air ascends the slopes, leading to enhanced orographically forced rainfall and the formation of mesoscale convective systems that propagate southeastward.[72] The SAMS exhibits significant interannual variability, largely modulated by sea surface temperature anomalies in the tropical Pacific Ocean, where warm El Niño phases suppress equatorial Amazon rainfall but boost it in the subtropics, while cool La Niña phases produce the opposite pattern.[72] This variability can prolong monsoon activity, contributing to extreme events such as the 2013 La Plata floods in Argentina, where anomalous low-level circulation sustained heavy rainfall exceeding 300 mm in hours, causing widespread inundation. In 2024, an extreme drought during the monsoon season affected the Amazon Basin, linked to El Niño, severely impacting ecosystems and water availability.[74][75] Some studies suggest connections to the North American Monsoon under a broader "Americas monsoon hypothesis," positing shared influences from hemispheric circulation patterns.[76]European Influences

The European monsoon refers to a debated mid-latitude analog of tropical monsoon systems, manifesting as seasonal convective precipitation primarily in central and eastern Europe during June to August. This period features increased rainfall driven by intense land surface heating over the continent, which generates low-pressure systems that draw moist air from the Black Sea and, to a lesser extent, the Mediterranean Sea. Typical additional summer rainfall in affected regions ranges from 100 to 300 mm above seasonal norms, supporting a wet early summer phase contrasted with drier winters. Unlike classic tropical monsoons, these patterns lack a pronounced reversal of prevailing winds, instead involving a strengthening of southerly and easterly flows that enhance moisture convergence without fully inverting the dominant westerlies.[77][78] Historical observations of these monsoon-like features date back to the 19th century, with early Russian and Polish meteorologists documenting the recurrent summer rains as a distinct seasonal phenomenon influencing regional climates. By the mid-20th century, the term "European monsoon" gained traction in scientific literature to describe these mid-latitude dynamics, building on earlier assumptions about seasonal wind shifts and precipitation cycles across the continent. These accounts emphasized the role of continental heating in initiating the rainy season, distinguishing it from the more uniform westerly influences in western Europe.[79][80] The variability of the European monsoon is strongly modulated by the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), where positive NAO phases enhance westerly moisture transport and intensify summer precipitation, while negative phases lead to drier conditions. Notable extremes include the 2002 Central European floods, triggered by persistent low-pressure systems that delivered over 300 mm of rain in just a few days across the Czech Republic, Germany, and Austria, exacerbating river overflows and causing widespread damage. A more recent example is the 2021 floods in Germany and Belgium, where extreme summer rainfall caused over 200 deaths and significant infrastructure damage due to enhanced moisture convergence.[81][82][83] Such events underscore the system's potential for high-impact variability, though overall intensities remain weaker than those of tropical monsoons due to the absence of robust ocean-land thermal contrasts.[81] These patterns play a vital role in European agriculture, particularly in central and eastern regions, by supplying essential summer moisture for grain and forage crops that constitute a substantial portion of continental production. Reliable convective rains during this period mitigate drought risks and support yields, though extremes like floods can disrupt harvesting and infrastructure. As a marginal extension of broader global monsoon domains, the European system highlights mid-latitude sensitivities to large-scale atmospheric teleconnections.[84]Global Patterns and Summary

Overview Table

The global monsoon systems influence more than half the world's population (over 4 billion people as of 2025), providing essential seasonal rainfall that contributes significantly to precipitation in tropical and subtropical regions, accounting for up to 70% of annual totals in affected areas.[8][85] These systems typically last 3-6 months, driven by land-sea thermal contrasts and solar heating, with durations varying by hemisphere (Northern: May-September; Southern: November-March).[8]| Region | Season/Timing | Wind Direction | Avg. Rainfall (summer season) | Key Drivers | Variability Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asia (Indian/East Asian) | June-September | Southwest (summer); Northeast (winter) | 600-1,000 mm | Tibetan Plateau heating, land-sea contrast, ITCZ migration | ENSO, Indian Ocean Dipole, intraseasonal oscillations (20-50 days) |

| Africa (West/North African) | June-September | Southwest (summer); Northeast (winter) | 200-1,000 mm (Sahel ~500 mm) | ITCZ northward migration, land-atmosphere interactions, solar insolation | ENSO, Atlantic SST variability, decadal shifts (e.g., wet 1950s vs. dry 1970s-1990s) |

| North America | June-August (onset in Mexico, progresses north) | Easterly/southerly | 150-300 mm (SW U.S.); 60-80% annual total in NW Mexico | Heating of Mexican Plateau, Gulf of Mexico moisture | ENSO, Pacific Decadal Oscillation, interannual precipitation variability |

| Australia | December-March | Northwesterly (summer); Southeasterly (winter) | 1,000-2,000 mm (northern regions) | ITCZ southward migration, land-sea thermal contrast | ENSO, Indian Ocean Dipole, Madden-Julian Oscillation |

| South America | November-April (peak Dec-Feb) | Easterly/northeasterly | 1,000-2,000 mm (Amazon basin) | Andes heating, South Atlantic Convergence Zone, ITCZ shift | ENSO, decadal oscillations (e.g., wetter 1980s), interannual drying trends |

| European Influences | Summer (June-August) | Westerly (Atlantic inflow) | 200-500 mm (variable, showery) | Land-sea contrast with Europe-Asia, mid-latitude cyclones | North Atlantic Oscillation, blocking patterns |

Interconnections and Variability

Monsoons worldwide are linked through atmospheric teleconnections that transmit variability across vast distances. The El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) exemplifies this, with El Niño phases typically reducing Asian summer monsoon rainfall by about 10% due to enhanced subsidence and weakened moisture convergence over South Asia, driven by a shift in the Pacific Walker circulation.[94] Similarly, El Niño events lead to drier conditions in the Australian summer monsoon, suppressing convection in the Maritime Continent and northern Australia through the same anomalous zonal circulation pattern.[95] The Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO), an eastward-propagating intraseasonal disturbance, further connects Asian and African monsoons by modulating convective activity across the Indo-Pacific and into the African continent, where MJO phases can enhance or suppress rainfall in the Sahel region through excited equatorial waves.[96] Decadal-scale variability also influences monsoon interconnections, notably via the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), which alters the North American monsoon's intensity. During positive PDO phases, cooler eastern Pacific sea surface temperatures strengthen the monsoon low-level jet and increase precipitation over the southwestern United States and Mexico, whereas negative phases weaken these features and reduce rainfall.[97] Globally, monsoon systems exhibited a weakening trend in precipitation from the 1950s to the 1970s, linked to reduced land-sea thermal contrasts and shifts in hemispheric circulation patterns, affecting multiple regions simultaneously.[98] Inter-regional dependencies are prominently illustrated by the linkage between the Asian and Australian monsoons, mediated by the Walker circulation. Strong Asian monsoon convection can induce compensatory descent over the Australian sector, leading to anti-phased rainfall variability, particularly during transitions influenced by ENSO.[95] The strength of such teleconnections is commonly assessed using Empirical Orthogonal Function (EOF) analysis of global rainfall datasets, where the leading EOF modes capture coherent monsoon patterns. Regression coefficients from this analysis quantify the linkage, modeled as: where is the rainfall anomaly at location , is the principal component of the -th EOF mode, is the regression coefficient indicating teleconnection intensity (e.g., negative values for anti-correlations), and is the residual; is computed as , revealing scales like 0.1–0.3 standardized units of rainfall per unit PC variance in Asian-Australian links.[99] Anthropogenic factors, particularly aerosols, introduce additional variability by dimming solar radiation over South Asia, which cools the land surface and weakens the monsoon circulation through a reduced meridional temperature gradient.[100] This effect has contributed to observed declines in monsoon clarity and intensity in the region over recent decades.[101]Impacts and Human Interactions

Environmental Effects