Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

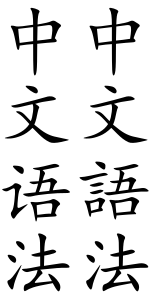

Chinese grammar

View on Wikipedia

[中文語法],

meaning "Chinese grammar", written vertically in simplified (left) and traditional (right) forms

The grammar of Standard Chinese shares many features with other varieties of Chinese. The language almost entirely lacks inflection; words typically have only one grammatical form. Categories such as number (singular or plural) and verb tense are often not expressed by grammatical means, but there are several particles that serve to express verbal aspect and, to some extent, mood.

The basic word order is subject–verb–object (SVO), as in English. Otherwise, Chinese is chiefly a head-final language, meaning that modifiers precede the words that they modify. In a noun phrase, for example, the head noun comes last, and all modifiers, including relative clauses, come in front of it. This phenomenon, however, is more typically found in subject–object–verb languages, such as Turkish and Japanese.

Chinese frequently uses serial verb constructions, which involve two or more verbs or verb phrases in sequence. Chinese prepositions behave similarly to serialized verbs in some respects,[a] and they are often referred to as coverbs. There are also location markers, which are placed after nouns and are thus often called postpositions; they are often used in combination with coverbs. Predicate adjectives are normally used without a copular verb ("to be") and so can be regarded as a type of verb.

As in many other East Asian languages, classifiers (or measure words) are required when numerals (and sometimes other words, such as demonstratives) are used with nouns. There are many different classifiers in the language, and each countable noun generally has a particular classifier associated with it. Informally, however, it is often acceptable to use the general classifier gè (个; 個) in place of other specific classifiers.

Word formation

[edit]In Chinese, the difference between words and Chinese characters is often not clear,[b] this is one of the reasons the Chinese script does not use spaces to separate words. A string of characters can be translated as a single English word, but these characters have some kind of independence. For example, tiàowǔ (跳舞; 'jump-dance'), meaning 'to dance', can be used as a single intransitive verb, or may be regarded as comprising two single lexical words. However, it does in fact function as a compound of the verb tiào (跳; 'to jump') and the object wǔ (舞; 'a dance').[1] Additionally, the present progressive aspect marker zhe (着) can be inserted between these two parts to form tiàozhewǔ (跳着舞; 'to be dancing').

Chinese morphemes (the smallest units of meaning) are mostly monosyllabic. In most cases, morphemes are represented by single characters. However, two or more monosyllabic morphemes can be translated as a single English word. These monosyllabic morphemes can be either free or bound – that is, in particular usage, they may or may not be able to stand independently. Most two-syllable compound nouns often have the head on the right (e.g. 蛋糕; dàngāo; 'egg-cake' means "cake"), while compound verbs often have the head on the left (e.g. 辩论; biànlùn; 'debate-discuss' means "debate").[2]

Some Chinese morphemes are polysyllabic; for example, the loanwords shāfā (沙发; 沙發; 'sofa') is the compound of shā (沙; 'sand') and fā (发; 發; 'to send', 'to issue'), but this compound is actually simply a transliteration of "sofa". Many native disyllabic morphemes, such as zhīzhū (蜘蛛; 'spider'), have consonant alliteration.[citation needed]

Many monosyllabic words have alternative disyllabic forms with virtually the same meaning, such as dàsuàn (大蒜; 'big-garlic') for suàn (蒜; 'garlic'). Many disyllabic nouns are produced by adding the suffix zi (子; 'child') to a monosyllabic word or morpheme. There is a strong tendency for monosyllables to be avoided in certain positions; for example, a disyllabic verb will not normally be followed by a monosyllabic object. This may be connected with the preferred metrical structure of the language.

Reduplication

[edit]Reduplication (i.e. the repetition of a syllable or word stem) is common in modern Chinese.

Noun Reduplication

[edit]- Family member: ex. mā-ma (妈妈; 媽媽, "mother"); dì-di (弟弟, "younger brother"); mèi-mei(妹妹, "younger sister")

- Fixed Expression: In modern Chinese, some noun are necessarily replicated, but their morphemes in classical Chinese are often directly used without any replication. ex. xīng-xīng (星星, "star"), from xīng (星, "star"). However, in Classical Chinese (then it become a modern Chengyus) pī-xīng-dài-yuè(披星戴月, literally "wearing stars like a coat and wearing moon like a hat", means "working day and night"[3])

- Diminutive or Childish Expression: treating the noun(mostly animal) as a "lovely child", even if it may be old or big. ex. gǒu-gǒu (狗狗, "puppy/doggy"), from gǒu (狗, "dog"); Māo-māo (貓貓, "pussy/kitty"), from Māo (貓, "cat").

Adjectives and Adverb Reduplication

[edit](1)AA reduplication: to emphasize the state described by the adjective/adverb,[4] or as a childish expression.chángcháng

- cháng-cháng(常常, "often"), from cháng (常, "constant, constantly");

- hóng-hóng-de (红红的; 紅紅的 "red"), from hóng (红; 紅, "red");

- ex. 手心看起来红红的; 手心看起來紅紅的(Shǒuxīn kàn qǐlái hóng-hóng-de, "palm looks red")

- gāo-gāo-xìng-xìng-de (高高兴兴地; 高高興興地 "very happily"), from gāo-xìng (高兴; 高興, "happy, happiness");

- ex. 高高兴兴地吃; 高高興興地吃 (Gāo-gāo-xìng-xìng-de chī, "eat happily")

- bīng-bīng-liáng-liáng-de (冰冰凉凉的, "ice-cool" ), from bīng-liáng (冰凉, "ice-cool");

- ex. 冰冰凉凉的饮料; 冰冰涼涼的飲料 (Bīng-bīng-liáng-liáng de yǐnliào, "ice-cold drink")

(2)ABB reduplication: to emphasize the state described by the adjective/adverb.

- xiāng-pēn-pēn (香喷喷; 香噴噴, literally" good smell spray out", means "smell very good"), from xiāng (香, "good smell") and pēn (喷; 噴, "spray")

- liàng-jīng-jīng (亮晶晶, "shining, bright and clear"), from liàng (亮, "bright") and jīng (晶, "shiny like a star")

Verb Reduplication

[edit](1)To mark the delimitative aspect (i.e. do something for a while) or for general emphasis – see the § Aspects section:

- xiě-xiě-zuòyè (写写作业; 寫寫作業 "write homework / write homework for a while"), from the verb xiě (写; 寫 "write") and the noun zuò-yè (作业; 作業 "homework")

Reduplication of Chinese classifier

[edit](1)means "every":

- Nǐmen yī gè gè dōu zhǎng dé yī fù cōng-míng xiāng (你們一個個都長得一副聰明相, "You all look smart", from Crystal Boys), where ordinarily gè (个; 個) is the general classifier. Literally, the phrase 一個個; yī gè gè means "every", and the character 都; dōu means "all".

(2)means "many":

- Yī-zuò-zuò qīng-shān (一座座青山, "many green hills"), where ordinarily zuò (座) is a proper classifier for shān (山, "hill").

Prefixes

[edit]- 可 — "-able"

- 可 靠 — "reliable"

- 可 敬 — "respectable"

- 反 — "anti-"

- 反 恐 [反恐] — "anti-terror"

- 反 教权的 [反教權的] — "anti-clerical"

- 反 法西斯 [反法西斯] — "anti-fascist"

Suffixes

[edit]- 化 — used to form verbs from nouns or adjectives

- 国际 化 [國際化] — "internationalize", from 国际 ("internationality")

- 恶 化 [惡化] — "worsen", from 恶 ("bad")

- 性 — "attribute"

- 安全 性 — "safety"

- 有效 性 — "effectiveness"

Intrafixes

[edit]Sentence structure

[edit]Chinese, like Spanish or English, is classified as an SVO (subject–verb–object) language. Transitive verbs precede their objects in typical simple clauses, while the subject precedes the verb. For example:[5]

他

tā

He

打

dǎ

hit

人。

rén

person

He hits someone.

Chinese can also be considered a topic-prominent language:[6] there is a strong preference for sentences that begin with the topic, usually "given" or "old" information; and end with the comment, or "new" information. Certain modifications of the basic subject–verb–object order are permissible and may serve to achieve topic-prominence. In particular, a direct or indirect object may be moved to the start of the clause to create topicalization. It is also possible for an object to be moved to a position in front of the verb for emphasis.[7]

Another type of sentence is what has been called an ergative structure,[8] where the apparent subject of the verb can move to object position; the empty subject position is then often occupied by an expression of location. Compare locative inversion in English. This structure is typical of the verb yǒu (有, "there is/are"; in other contexts the same verb means "have"), but it can also be used with many other verbs, generally denoting position, appearance or disappearance. An example:

院子

yuànzi

Courtyard

里

lǐ

in

停着

tíngzhe

park

车。

chē

vehicle

[院子裡停著車。/ 院子裏停着車。]

In the courtyard is parked a vehicle.

Chinese is also to some degree a pro-drop or null-subject language, meaning that the subject can be omitted from a clause if it can be inferred from the context.[9] In the following example, the subject of the verbs for "hike" and "camp" is left to be inferred—it may be "we", "I", "you", "she", etc.

今天

jīntiān

Today

爬

pá

climb

山

shān

mountain,

明天

míngtiān

tomorrow

露

lù

outdoors

营。

yíng

camp

[今天爬山,明天露營。]

Today hike up mountains, tomorrow camp outdoors.

In the next example the subject is omitted and the object is topicalized by being moved into subject position, to form a passive-type sentence. For passive sentences with a marker such as 被; bèi, see the passive section.

Adverbs and adverbial phrases that modify the verb typically come after the subject but before the verb, although other positions are sometimes possible; see Adverbs and adverbials. For constructions that involve more than one verb or verb phrase in sequence, see Serial verb constructions. For sentences consisting of more than one clause, see Conjunctions.

Objects

[edit]Some verbs can take both an indirect object and a direct object. Indirect normally precedes direct, as in English:

With many verbs, however, the indirect object may alternatively be preceded by prepositional gěi (给; 給); in that case it may either precede or follow the direct object. (Compare the similar use of to or for in English.)

To emphasize the direct object, it can be combined with the accusative marker bǎ (把, literally "hold") to form a "bǎ + direct object" phrase.[10] This phrase is placed before the verb. For example:

Other markers can be used in a similar way as bǎ, such as the formal jiāng (将; 將, literally "lead") :

将

Jiāng

Jiāng

办理

bàn-lǐ

handle

情形

qíng-xíng

status

签

qiān

sign

报

bào

report

长官。

zhǎng-guān

superior

[將辦理情形簽報長官。]

Submit the implementation status report to the superior, and ask for approval.

and colloquial ná (拿, literally "get")

他

Tā

he

能

néng

can

拿

ná

ná

我

wǒ

me

怎样?

zěn-yàng

what

[他能拿我怎樣?]

What can he do to me? (He can't do anything to me.)

To explain this kind of usage, some linguists assume that some verbs can take two direct objects, called the called "inner" and "outer" object.[11] Typically, the outer object will be placed at the start of the sentence (which is the topic) or introduced via the bǎ phrase. For example:

Noun phrases

[edit]The head noun of a noun phrase comes at the end of the phrase; this means that everything that modifies the noun comes before it. This includes attributive adjectives, determiners, quantifiers, possessives, and relative clauses.

Chinese does not have articles as such; a noun may stand alone to represent what in English would be expressed as "the ..." or "a[n] ...". However the word yī (一, "one"), followed by the appropriate classifier, may be used in some cases where English would have "a" or "an". It is also possible, with many classifiers, to omit the yī and leave the classifier on its own at the start of the noun phrase.

The demonstratives are zhè (这; 這, "this"), and nà (那, "that"). When used before a noun, these are often followed by an appropriate classifier (for discussion of classifiers, see Classifiers below and the article Chinese classifiers). However this use of classifiers is optional.[12] When a noun is preceded by a numeral (or a demonstrative followed by a numeral), the use of a classifier or measure word is in most cases considered mandatory. (This does not apply to nouns that function as measure words themselves; this includes many units of measurement and currency.)

The plural marker xiē (些, "some, several"; also used to pluralize demonstratives) is used without a classifier. However jǐ (几; 幾, "some, several, how many") takes a classifier.[13]

For adjectives in noun phrases, see the Adjectives section. For noun phrases with pronouns rather than nouns as the head, see the Pronouns section.

Possessives are formed by adding de (的)—the same particle that is used after relative clauses and sometimes after adjectives—after the noun, noun phrase or pronoun that denotes the possessor.

Relative clauses

[edit]Chinese relative clauses, like other noun modifiers, precede the noun they modify. Like possessives and some adjectives, they are marked with the final particle de (的). A free relative clause is produced if the modified noun following the de is omitted. A relative clause usually comes after any determiner phrase, such as a numeral and classifier. For emphasis, it may come before the determiner phrase.[14]

There is usually no relative pronoun in the relative clause. Instead, a gap is left in subject or object position as appropriate. If there are two gaps—the additional gap being created by pro-dropping—ambiguity may arise. For example, chī de (吃的) may mean "[those] who eat" or "[that] which is eaten". When used alone, it usually means "things to eat".

If the relative item is governed by a preposition in the relative clause, then it is denoted by a pronoun, e.g. tì tā (替他, "for him"), to explain "for whom". Otherwise the whole prepositional phrase is omitted, the preposition then being implicitly understood.

For example sentences, see Relative clause → Mandarin.

Classifiers

[edit]Some English words are paired with specific nouns to indicate their counting units. For example, Bottle in "two bottles of wine" and sheet in "three sheets of paper". However, most English nouns can be counted directly without specifying units, while counting of most Chinese nouns must be associated with a specific classifier, namely liàng-cí (量词; 量詞, "measure words"), to represent their counting units.[15] Every Chinese noun can only be associated with a limited number of classifiers. For example

一

yī

one

瓶

píng

bottle

酒

jiǔ

wine

[一瓶酒]

a bottle of wine

两

liǎng

two

杯

bēi

cup

酒

jiǔ

wine

[兩杯酒]

two glasses of wine

píng (瓶, "bottle") and bēi (杯, "cup") are both proper classifiers of the countable noun jiǔ (酒), while liǎng zuò jiǔ (两座酒) and liǎng-jiǔ (两酒) are unacceptable.

While there are dozens of classifiers, the general classifier gè (个; 個) is colloquially (i.e. in informal conversations) acceptable for most nouns. However, there are still some exceptions. For example, liǎng gè jiǔ (两个酒) is weird and unacceptable.

Most classifiers originated as independent words in Classical Chinese, so they are generally associated with certain groups of nouns with common properties related to their own classical meaning, for example:[3]

| Classifier

(Original meaning) |

Common Properties | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| tiáo (条; 條, "twig") | long or thin

(twigs are long and thin) |

yī-tiáo-shéngzi (一条绳子; 一條繩子, "a rope")

liǎng-tiáo-shé (两条蛇; 兩條蛇, "two snakes") |

| bǎ (把, "hold") | with a handle

(a handle to hold) |

yī-bǎ-dāo (一把刀, "a knife")

liǎng-bǎ-sǎn (两把伞; 兩把傘, "two umbrellas") |

| zhāng (张; 張, "draw a bow") | flat or sheet-like

("extended" like a bow) |

yī zhāng zhào-piàn (一张照片; 一張照片, "a photograph")

liǎng zhāng máo-pí (两张毛皮; 兩張毛皮, "two furs") |

Therefore, collocation of classifiers and noun sometimes depends on how native speakers realize them. For example, the noun zhuōzi (桌子, "table") is associated with the classifier zhāng (张; 張), due to the sheet-like table-top. Additionally, yǐ-zi (椅子, "chair") is associated with bǎ (把, "hold"), because a chair can be moved by holding its top like a handle. Furthermore, due to the invention of the folding chair, yǐ-zi (椅子, "chair") is also associated with the classifier zhāng (张; 張) to express a folding chair can be "extended" (unfolded).

Classifiers are also used optionally after demonstratives, and in certain other situations. See the Noun phrases section, and the article Chinese classifier.

Numerals

[edit]Pronouns

[edit]The Chinese personal pronouns are wǒ (我, "I, me"), nǐ (你; 你/妳,[d] "you"), and tā (他/她/牠/它, "he, him / she, her / it (animals) / it (inanimate objects)". Plurals are formed by adding men (们; 們): wǒmen (我们; 我們, "we, us"), nǐmen (你们; 你們, "you"), tāmen (他们/她们/它们/它们; 他們/她們/牠們/它們, "they/them"). There is also nín (您), a formal, polite word for singular "you", as well as a less common plural form, nínmen (您们). Some northern dialects have a third-person formal, polite word 怹 (他+心, he/him + heart) similar to 您 (你+心, you + heart).[16] The alternative inclusive word for "we/us"—zán (咱) or zá[n]men (咱们; 咱們), specifically including the listener[17] —is used colloquially. The third-person pronouns are not often used for inanimates, with demonstratives used instead.

Possessives are formed with de (的), such as wǒde (我的, "my, mine"), wǒmende (我们的; 我們的, "our[s]"), etc. The de may be omitted in phrases denoting inalienable possession, such as wǒ māma (我妈妈; 我媽媽, "my mom").

The demonstrative pronouns are zhè (这; 這, "this", colloquially pronounced zhèi as a shorthand for 这一; 這一[18]) and nà (那, "that", colloquially pronounced nèi as a shorthand for 那一[19]). They are optionally pluralized by the addition of plural quantifiers xiē (些) or qún (群). There is a reflexive pronoun zìjǐ (自己) meaning "oneself, myself, etc.", which can stand alone as an object or a possessive, or may follow a personal pronoun for emphasis. The reciprocal pronoun "each other" can be translated from bǐcǐ (彼此), usually in adverb position. An alternative is hùxiāng (互相, "mutually").

Adjectives

[edit]Adjectives can be used attributively, before a noun. The relative marker de (的)[e] may be added after the adjective, but this is not always required; "black horse" may be either hēi mǎ (黑马; 黑馬) or hēi de mǎ (黑的马; 黑的馬). When multiple adjectives are used, the order "quality/size – shape – color" is followed, although this is not necessary when each adjective is made into a separate phrase with the addition of de.[20]

Gradable adjectives can be modified by words meaning "very", etc.; such modifying adverbs normally precede the adjective, although some, such as jíle (极了; 極了, "extremely"), come after it.

When adjectives co-occur with classifiers, they normally follow the classifier. However, with most common classifiers, when the number is "one", it is also possible to place adjectives like "big" and "small" before the classifier for emphasis.

Adjectives can also be used predicatively. In this case they behave more like verbs; there is no need for a copular verb in sentences like "he is happy" in Chinese; one may say simply tā gāoxìng (他高兴; 他高興, "he happy"), where the adjective may be interpreted as a verb meaning "is happy". In such sentences it is common for the adjective to be modified by a word meaning "very" or the like; in fact the word hěn (很, "very") is often used in such cases with gradable adjectives, even without carrying the meaning of "very".

It is nonetheless possible for a copula to be used in such sentences, to emphasize the adjective. In the phrase tā shì gāoxìng le, (他是高兴了; 他是高興了, "he is now truly happy"), shì is the copula meaning "is", and le is the inceptive marker discussed later.[21] This is similar to the cleft sentence construction. Sentences can also be formed in which an adjective followed by de (的) stands as the complement of the copula.

Adverbs and adverbials

[edit]Adverbs and adverbial phrases normally come in a position before the verb, but after the subject of the verb. In sentences with auxiliary verbs, the adverb usually precedes the auxiliary verb as well as the main verb. Some adverbs of time and attitude ("every day", "perhaps", etc.) may be moved to the start of the clause, to modify the clause as a whole. However, some adverbs cannot be moved in this way. These include three words for "often", cháng (常), chángcháng (常常) and jīngcháng (经常; 經常); dōu (都, "all"); jiù (就, "then"); and yòu (又, "again").[22]

Adverbs of manner can be formed from adjectives using the clitic de (地).[f] It is generally possible to move these adverbs to the start of the clause, although in some cases this may sound awkward, unless there is a qualifier such as hěn (很, "very") and a pause after the adverb.

Some verbs take a prepositional phrase following the verb and its direct object. These are generally obligatory constituents, such that the sentence would not make sense if they were omitted. For example:

There are also certain adverbial "stative complements" which follow the verb. The character de (得)[g] followed by an adjective functions the same as the phrase "-ly" in English, turning the adjective into an adverb. The second is hǎo le (好了, "complete"). It is not generally possible for a single verb to be followed by both an object and an adverbial complement of this type, although there are exceptions in cases where the complement expresses duration, frequency or goal.[24] To express both, the verb may be repeated in a special kind of serial verb construction; the first instance taking an object, the second taking the complement. Aspect markers can then appear only on the second instance of the verb.

The typical Chinese word order "XVO", where an oblique complement such as a locative prepositional phrase precedes the verb, while a direct object comes after the verb, is very rare cross-linguistically; in fact, it is only in varieties of Chinese that this is attested as the typical ordering.[25]

Locative phrases

[edit]

Expressions of location in Chinese may include a preposition, placed before the noun; a postposition, placed after the noun; both preposition and postposition; or neither. Chinese prepositions are commonly known as coverbs – see the Coverbs section. The postpositions—which include shàng (上, "up, on"), xià (下, "down, under"), lǐ (里; 裡, "in, within"), nèi (内, "inside") and wài (外, "outside")—may also be called locative particles.[26]

In the following examples locative phrases are formed from a noun plus a locative particle:

桌子

zhuōzi

table

上

shàng

on

on the table

房子

fángzi

house

里

lǐ

in

[房子裡]

in the house

The most common preposition of location is zài (在, "at, on, in"). With certain nouns that inherently denote a specific location, including nearly all place names, a locative phrase can be formed with zài together with the noun:

在

zài

in

美国

měiguó

America

[在美國]

in America

However other types of nouns still require a locative particle as a postposition in addition to zài:

在

zài

in

报纸

bàozhǐ

newspaper

上

shàng

on

[在報紙上]

in the newspaper

If a noun is modified so as to denote a specific location, as in "this [object]...", then it may form locative phrases without any locative particle. Some nouns which can be understood to refer to a specific place, like jiā (家, home) and xuéxiào (学校; 學校, "school"), may optionally omit the locative particle. Words like shàngmiàn (上面, "top") can function as specific-location nouns, like in zài shàngmiàn (在上面, "on top"), but can also take the role of locative particle, not necessarily with analogous meaning. The phrase zài bàozhǐ shàngmiàn (在报纸上面; 在報紙上面; 'in newspaper-top'), can mean either "in the newspaper" or "on the newspaper".[27]

In certain circumstances zài can be omitted from the locative expression. Grammatically, a noun or noun phrase followed by a locative particle is still a noun phrase. For instance, zhuōzi shàng can be regarded as short for zhuōzi shàngmiàn, meaning something like "the table's top". Consequently, the locative expression without zài can be used in places where a noun phrase would be expected – for instance, as a modifier of another noun using de (的), or as the object of a different preposition, such as cóng (从; 從, "from"). The version with zài, on the other hand, plays an adverbial role. However, zài is usually omitted when the locative expression begins a sentence with the ergative structure, where the expression, though having an adverbial function, can be seen as filling the subject or noun role in the sentence. For examples, see sentence structure section.

The word zài (在), like certain other prepositions or coverbs, can also be used as a verb. A locative expression can therefore appear as a predicate without the need for any additional copula. For example, "he is at school" (他在学校; 他在學校; tā zài xuéxiào, literally "he at school").

Comparatives and superlatives

[edit]Comparative sentences are commonly expressed simply by inserting the standard of comparison, preceded by bǐ (比, "than"). The adjective itself is not modified. The bǐ (比, "than") phrase is an adverbial, and has a fixed position before the verb. See also the section on negation.

If there is no standard of comparison—i.e., a than phrase—then the adjective can be marked as comparative by a preceding adverb bǐjiào (比较; 比較), jiào (较; 較) or gèng (更), all meaning "more". Similarly, superlatives can be expressed using the adverb zuì (最, "most"), which precedes a predicate verb or adjective.

Adverbial phrases meaning "like [someone/something]" or "as [someone/something]" can be formed using gēn (跟), tóng (同) or xiàng (像) before the noun phrase, and yīyàng (一样; 一樣) or nàyàng (那样; 那樣) after it.[28]

The construction yuè ... yuè ... 越...越... can be translated into statements of the type "the more ..., the more ...".

Copula

[edit]The Chinese copular verb is shì (是). This is the equivalent of English "to be" and all its forms—"am", "is", "are", "was", "were", etc. However, shì is normally only used when its complement is a noun or noun phrase. As noted above, predicate adjectives function as verbs themselves, as does the locative preposition zài (在), so in sentences where the predicate is an adjectival or locative phrase, shì is not required.

For another use of shì, see shì ... [de] construction in the section on cleft sentences. The English existential phrase "there is" ["there are", etc.] is translated using the verb yǒu (有), which is otherwise used to denote possession.

Aspects

[edit]Chinese does not have grammatical markers of tense. The time at which action is conceived as taking place—past, present, future—can be indicated by expressions of time—"yesterday", "now", etc.—or may simply be inferred from the context. However, Chinese does have markers of aspect, which is a feature of grammar that gives information about the temporal flow of events. There are two aspect markers that are especially commonly used with past events: the perfective-aspect le (了) and the experiential guo (过; 過). Some authors, however, do not regard guo (or zhe; see below) as markers of aspect.[29] Both le and guo immediately follow the verb.

There is also a sentence-final inchoative le (了), which is an aspect-marking particle that indicates a change in state. Following a convention used by some textbooks, it is listed with the modal particles below, even though it does not indicate a grammatical mood.

The perfective le presents the viewpoint of "an event in its entirety".[30] It is sometimes considered to be a past tense marker, although it can also be used with future events, given appropriate context. Some examples of its use:

我

wǒ

I

当

dāng

serve as

了

le

le

兵。

bīng

soldier.

[我當了兵。]

I became a soldier.

Using le (了) shows this event that has taken place or took place at a particular time.

他

tā

He

看

kàn

watch

了

le

le

三

sān

three

场

chǎng

sports-CL

球赛。

qiúsài

ballgames.

[他看了三場球賽。]

He watched three ballgames.

This format of le (了) is usually used in a time-delimited context such as "today" or "last week".

The above may be compared with the following examples with guo, and with the examples with sentence-final le given under Particles.

The experiential guo "ascribes to a subject the property of having experienced the event".[31]

我

wǒ

I

当

dāng

serve-as

过

guo

guo

兵。

bīng

soldier.

[我當過兵。]

I have been a soldier before.

This also implies that the speaker no longer is a soldier.

他

tā

He

看

kàn

watch

过

guo

guo

三

sān

three

场

chǎng

sports-CL

球赛。

qiúsài

ballgames.

[他看過三場球賽。]

He has watched three ballgames up to now.

There are also two imperfective aspect markers: zhèngzài (正在) or zài (在), and zhe (着; 著), which denote ongoing actions or states. Zhèngzài and zài precede the verb, and are usually used for ongoing actions or dynamic events – they may be translated as "[be] in the process of [-ing]" or "[be] in the middle of [-ing]". Zhe follows the verb, and is used mostly for static situations.

我

wǒ

I

[正] 在

zhèng zài

in-middle-of

挂

guà

hang

画。

huà

pictures

[我[正]在掛畫。]

I'm hanging pictures up.

墙

qiáng

Wall

上

shàng

on

挂

guà

hang

着

zhe

ongoing

一

yì

one

幅

fú

picture-CL

画。

huà

picture

[牆上掛著一幅畫。]

A picture is hanging on the wall.

Both markers may occur in the same clause, however. For example, tā zhèngzai dǎ [zhe] diànhuà, "he is in the middle of telephoning someone" (他正在打[着]电话; 他正在打[著]電話; 'he [', 'in-middle-of]', '[', 'verb form]', '[', 'ongoing]', 'telephone').[32]

The delimitative aspect denotes an action that goes on only for some time, "doing something 'a little bit'".[33] This can be expressed by reduplication of a monosyllabic verb, like the verb zǒu (走 "walk") in the following sentence:

我

wǒ

I

到

dào

to

公园

gōngyuán

park

走

zǒu

walk

走。

zǒu

walk

[我到公園走走。]

I'm going for a walk in the park.

An alternative construction is reduplication with insertion of "one" (一 yī). For example, zǒu yi zǒu (走一走), which might be translated as "walk a little walk". A further possibility is reduplication followed by kàn (看 "to see"); this emphasizes the "testing" nature of the action. If the verb has an object, kàn follows the object.

Some compound verbs, such as restrictive-resultative and coordinate compounds, can also be reduplicated on the pattern tǎolùn-tǎolùn (讨论讨论; 討論討論), from the verb tǎolùn (讨论; 討論), meaning "discuss". Other compounds may be reduplicated, but for general emphasis rather than delimitative aspect. In compounds that are verb–object combinations, like tiào wǔ (跳舞; 'to jump a dance', "dance"), a delimitative aspect can be marked by reduplicating the first syllable, creating tiào-tiào wǔ (跳跳舞), which may be followed with kàn (看).

Passive

[edit]As mentioned above, the fact that a verb is intended to be understood in the passive voice is not always marked in Chinese. However, it may be marked using the passive marker 被 bèi, followed by the agent, though bèi may appear alone, if the agent is not to be specified.[h] Certain causative markers can replace bèi, such as those mentioned in the Other cases section, gěi, jiào and ràng. Of these causative markers, only gěi can appear alone without a specified agent. The construction with a passive marker is normally used only when there is a sense of misfortune or adversity.[34] The passive marker and agent occupy the typical adverbial position before the verb. See the Negation section for more. Some examples:

我们

wǒmen

We

被

bèi

by

他

tā

him

骂

mà

scolded

了。

le

PFV

[我們被他罵了。]

We were scolded by him.

他

tā

He

被

bèi

by

我

wǒ

me

打

dǎ

beaten

了

le

PFV

一

yí

one

顿。

dùn

event-CL

[他被我打了一頓。]

He was beaten up by me once.

Negation

[edit]The most commonly used negating element is bù (不), pronounced with second tone when followed by a fourth tone. This can be placed before a verb, preposition or adverb to negate it. For example: "I don't eat chicken" (我不吃鸡; 我不吃雞; wǒ bù chī jī; 'I not eat chicken'). For the double-verb negative construction with bù, see Complement of result, below. However, the verb yǒu (有)—which can mean either possession, or "there is/are" in existential clauses—is negated using méi (没; 沒) to produce méiyǒu (没有; 沒有; 'not have').

For negation of a verb intended to denote a completed event, méi or méiyǒu is used instead of bù (不), and the aspect marker le (了) is then omitted. Also, méi[yǒu] is used to negate verbs that take the aspect marker guo (过; 過); in this case the aspect marker is not omitted.[35]

In coverb constructions, the negator may come before the coverb (preposition) or before the full verb, the latter being more emphatic. In constructions with a passive marker, the negator precedes that marker; similarly, in comparative constructions, the negator precedes the bǐ phraseNot clear (unless the verb is further qualified by gèng (更, "even more"), in which case the negator may follow the gèng to produce the meaning "even less").[36]

The negator bié (别) precedes the verb in negative commands and negative requests, such as in phrases meaning "don't ...", "please don't ...".

The negator wèi (未) means "not yet". Other items used as negating elements in certain compound words include wú (无; 無),wù (勿), miǎn (免) and fēi (非).

A double negative makes a positive, as in sentences like wǒ bú shì bù xǐhuān tā (我不是不喜欢她; 我不是不喜歡她, "It's not that I don't like her" ). For this use of shì (是), see the Cleft sentences section.

Questions

[edit]In wh-questions in Chinese, the question word is not fronted. Instead, it stays in the position in the sentence that would be occupied by the item being asked about. For example, "What did you say?" is phrased as nǐ shuō shé[n]me (你说什么?; 你說什麼?, literally "you say what"). The word shénme (什么; 什麼, "what" or "which"), remains in the object position after the verb.

Other interrogative words include:

- "Who": shuí/shéi (谁; 誰)

- "What": shénme (什么; 什麼); shá (啥, used informally)

- "Where": nǎr (哪儿; 哪兒); nǎlǐ (哪里; 哪裡); héchù (何处; 何處)

- "When": shénme shíhòu (什么时候; 什麼時候); héshí (何时; 何時)

- "Which": nǎ (哪)

- When used to mean "which ones", nǎ is used with a classifier and noun, or with xiē (些) and noun. The noun may be omitted if understood through context.

- "Why": wèishé[n]me (为什么; 為什麼); gànmá (干吗; 幹嘛)

- "How many": duōshǎo (多少)

- When the number is quite small, jǐ (几; 幾) is used, followed by a classifier.

- "How": zěnme[yang] (怎么[样]; 怎麼[樣]); rúhé (如何).

Disjunctive questions can be made using the word háishì (还是; 還是) between the options, like English "or". This differs from the word for "or" in statements, which is huòzhě (或者).

Yes–no questions can be formed using the sentence-final particle ma (吗; 嗎), with word order otherwise the same as in a statement. For example, nǐ chī jī ma? (你吃鸡吗?; 你吃雞嗎?; 'you eat chicken MA', "Do you eat chicken?").

An alternative is the A-not-A construction, using phrases like chī bu chī (吃不吃, "eat or not eat").[i] With two-syllable verbs, sometimes only the first syllable is repeated: xǐ-bu-xǐhuān ( 喜不喜欢; 喜不喜歡, "like or not like"), from xǐhuān (喜欢; 喜歡, "like"). It is also possible to use the A-not-A construction with prepositions (coverbs) and phrases headed by them, as with full verbs.

The negator méi (没; 沒) can be used rather than bù in the A-not-A construction when referring to a completed event, but if it occurs at the end of the sentence—i.e. the repetition is omitted—the full form méiyǒu (没有; 沒有) must appear.[37]

For answering yes–no questions, Chinese has words that may be used like the English "yes" and "no" – duì (对; 對) or shì de (是的) for "yes"; bù (不) for "no" – but these are not often used for this purpose; it is more common to repeat the verb or verb phrase (or entire sentence), negating it if applicable.

Imperatives

[edit]Second-person imperative sentences are formed in the same way as statements, and like in English, the subject "you" is often omitted.

Orders may be softened by preceding them with an element such as qǐng (请, "to ask"), in this use equivalent to English "please". See Particles for more. The sentence-final particle ba (吧) can be used to form first-person imperatives, equivalent to "let's...".

Serial verb constructions

[edit]Chinese makes frequent use of serial verb constructions, or verb stacking, where two or more verbs or verb phrases are concatenated together. This frequently involves either verbal complements appearing after the main verb, or coverb phrases appearing before the main verb, but other variations of the construction occur as well.

Auxiliaries

[edit]A main verb may be preceded by an auxiliary verb, as in English. Chinese auxiliaries include néng and nénggòu (能 and 能够; 能夠, "can"); huì (会; 會, "know how to"); kéyǐ (可以, "may"); gǎn (敢, "dare"); kěn (肯, "be willing to"); yīnggāi (应该; 應該, "should"); bìxū (必须; 必須, "must"); etc. The auxiliary normally follows an adverb, if present. In shortened sentences an auxiliary may be used without a main verb, analogously to English sentences such as "I can."

Verbal complements

[edit]The active verb of a sentence may be suffixed with a second verb, which usually indicates either the result of the first action, or the direction in which it took the subject. When such information is applicable, it is generally considered mandatory. The phenomenon is sometimes called double verbs.

Complement of result

[edit]A complement of result, or resultative complement (结果补语; 結果補語; jiéguǒ bǔyǔ) is a verbal suffix which indicates the outcome, or possible outcome, of the action indicated by the main verb. In the following examples, the main verb is tīng (听; 聽 "to listen"), and the complement of result is dǒng (懂, "to understand/to know").

听

tīng

hear

懂

dǒng

understand

[聽懂]

to understand something you hear

Since they indicate an absolute result, such double verbs necessarily represent a completed action, and are thus negated using méi (没; 沒):

没

méi

not

听

tīng

hear

懂

dǒng

understand

[沒聽懂]

to have not understood something you hear

The morpheme de (得) is placed between the double verbs to indicate possibility or ability. This is not possible with "restrictive" resultative compounds such as jiéshěng (节省, literally "reduce-save", meaning "to save, economize").[38]

听

tīng

hear

得

de

possible/able

懂

dǒng

understand

[聽得懂]

to be able to understand something you hear

This is equivalent in meaning to néng tīng dǒng (能听懂; 能聽懂), using the auxiliary néng (能), equivalent to "may" or "can".[j]

To negate the above construction, de (得) is replaced by bù (不):

听

tīng

hear

不

bù

impossible/unable

懂

dǒng

understand

[聽不懂]

to be unable to understand something you hear

With some verbs, the addition of bù and a particular complement of result is the standard method of negation. In many cases the complement is liǎo, represented by the same character as the perfective or modal particle le (了). This verb means "to finish", but when used as a complement for negation purposes it may merely indicate inability. For example: shòu bù liǎo (受不了, "to be unable to tolerate").

The complement of result is a highly productive and frequently used construction. Sometimes it develops into idiomatic phrases, as in è sǐ le (饿死了; 餓死了, literally "hungry-until-die already", meaning "to be starving") and qì sǐ le (气死了; 氣死了, literally "mad-until-die already", meaning "to be extremely angry"). The phrases for "hatred" (看不起; kànbùqǐ), "excuse me" (对不起; 對不起; duìbùqǐ), and "too expensive to buy" (买不起; 買不起; mǎi bùqǐ) all use the character qǐ (起, "to rise up") as a complement of result, but their meanings are not obviously related to that meaning. This is partially the result of metaphorical construction, where kànbùqǐ (看不起) literally means "to be unable to look up to"; and duìbùqǐ (对不起; 對不起) means "to be unable to face someone".

Some more examples of resultative complements, used in complete sentences:

他

tā

he

把

bǎ

object-CL

盘子

pánzi

plate

打

dǎ

hit

破

pò

break

了。

le

PRF

[他把盤子打破了。]

He hit/dropped the plate, and it broke.

Double-verb construction where the second verb, "break", is a suffix to the first, and indicates what happens to the object as a result of the action.

这

zhè(i)

this

部

bù

电影

diànyǐng

movie

我

wǒ

I

看

kàn

watch

不

bù

impossible/unable

懂。

dǒng

understand

[這部電影我看不懂。]

I can't understand this movie even though I watched it.

Another double-verb where the second verb, "understand", suffixes the first and clarifies the possibility and success of the relevant action.

Complement of direction

[edit]A complement of direction, or directional complement (趋向补语; 趨向補語; qūxiàng bǔyǔ) indicates the direction of an action involving movement. The simplest directional complements are qù (去, "to go") and lái (来; 來, "to come"), which may be added after a verb to indicate movement away from or towards the speaker, respectively. These may form compounds with other verbs that further specify the direction, such as shàng qù (上去, "to go up"), gùo lái (过来; 過來, "to come over"), which may then be added to another verb, such as zǒu (走, "to walk"), as in zǒu gùo qù (走过去; 走過去, "to walk over"). Another example, in a whole sentence:

他

tā

he

走

zǒu

walk

上

shàng

up

来

lái

come

了。

le

PRF

[他走上來了。]

He walked up towards me.

- The directional suffixes indicate "up" and "towards".

If the preceding verb has an object, the object may be placed either before or after the directional complement(s), or even between two directional complements, provided the second of these is not qù (去).[39]

The structure with inserted de or bù is not normally used with this type of double verb. There are exceptions, such as "to be unable to get out of bed" (起不来床; 起不來床; qǐ bù lái chuáng or 起床不来; 起床不來; qǐ chuáng bù lái).

Coverbs

[edit]Chinese has a class of words, called coverbs, which in some respects resemble both verbs and prepositions. They appear with a following object (or complement), and generally denote relationships that would be expressed by prepositions (or postpositions) in other languages. However, they are often considered to be lexically verbs, and some of them can also function as full verbs. When a coverb phrase appears in a sentence together with a main verb phrase, the result is essentially a type of serial verb construction. The coverb phrase, being an adverbial, precedes the main verb in most cases. For instance:

我

wǒ

I

帮

bāng

help

你

nǐ

you

找

zhǎo

find

他。

tā.

him

[我幫你找他。]

I will find him for you.

Here the main verb is zhǎo (找, "find"), and bāng (帮; 幫) is a coverb. Here bāng corresponds to the English preposition "for", even though in other contexts it might be used as a full verb meaning "help".

我

wǒ

I

坐

zuò

sit

飞机

fēijī

airplane

从

cóng

from

上海

Shànghǎi

Shanghai

到

dào

arrive(to)

北京

Běijīng

Beijing

去。

qù.

go

[我坐飛機從上海到北京去。]

I'll go from Shanghai to Beijing by plane.

Here there are three coverbs: zuò (坐 "by"), cóng (从; 從, "from"), and dào (到, "to"). The words zuò and dào can also be verbs, meaning "sit" and "arrive [at]" respectively. However, cóng is not normally used as a full verb.

A very common coverb that can also be used as a main verb is zài (在), as described in the Locative phrases section. Another example is gěi (给), which as a verb means "give". As a preposition, gěi may mean "for", or "to" when marking an indirect object or in certain other expressions.

我

wǒ

I

给

gěi

to

你

nǐ

you

打

dǎ

strike

电话。

diànhuà

telephone

[我給你打電話。]

I'll give you a telephone call

Because coverbs essentially function as prepositions, they can also be referred to simply as prepositions. In Chinese they are called jiè cí (介词; 介詞), a term which generally corresponds to "preposition", or more generally, "adposition". The situation is complicated somewhat by the fact that location markers—which also have meanings similar to those of certain English prepositions—are often called "postpositions".

Coverbs normally cannot take aspect markers, although some of them form fixed compounds together with such markers, such as gēnzhe (跟着; 跟著; 'with +[aspect marker]'), ànzhe (按着; 按著, "according to"), yánzhe (沿着; 沿著, "along"), and wèile (为了; 為了 "for").[40]

Other cases

[edit]Serial verb constructions can also consist of two consecutive verb phrases with parallel meaning, such as hē kāfēi kàn bào, "drink coffee and read the paper" (喝咖啡看报; 喝咖啡看報; 'drink coffee read paper'). Each verb may independently be negated or given the le aspect marker.[41] If both verbs would have the same object, it is omitted the second time.

Consecutive verb phrases may also be used to indicate consecutive events. Use of the le aspect marker with the first verb may imply that this is the main verb of the sentence, the second verb phrase merely indicating the purpose. Use of this le with the second verb changes this emphasis, and may require a sentence-final le particle in addition. On the other hand, the progressive aspect marker zài (在) may be applied to the first verb, but not normally the second alone. The word qù (去, "go") or lái (来; 來, "come") may be inserted between the two verb phrases, meaning "in order to".

For constructions with consecutive verb phrases containing the same verb, see under Adverbs. For immediate repetition of a verb, see Reduplication and Aspects.

Another case is the causative or pivotal construction.[42] Here the object of one verb also serves as the subject of the following verb. The first verb may be something like gěi (给, "allow", or "give" in other contexts), ràng (让; 讓, "let"), jiào (叫, "order" or "call") or shǐ (使, "make, compel"), qǐng (请; 請, "invite"), or lìng (令, "command"). Some of these cannot take an aspect marker such as le when used in this construction, like lìng, ràng, shǐ. Sentences of this type often parallel the equivalent English pattern, except that English may insert the infinitive marker "to". In the following example the construction is used twice:

他

tā

he

要

yào

want

我

wǒ

me

请

qǐng

invite

他

tā

him

喝

hē

drink

啤酒。

píjiǔ

beer

[他要我請他喝啤酒。]

He wants me to treat him [to] beer.

Particles

[edit]Chinese has a number of sentence-final particles – these are weak syllables, spoken with neutral tone, and placed at the end of the sentence to which they refer. They are often called modal particles or yǔqì zhùcí (语气助词; 語氣助詞), as they serve chiefly to express grammatical mood, or how the sentence relates to reality and/or intent. They include:[43]

- ma (吗; 嗎), which changes a statement into a yes–no question

- ne (呢), which expresses surprise, produces a question "with expectation", or expresses a currently ongoing event when answering a question

- ba (吧), which serves as a tag question, e.g. "don't you think so?"; produces a suggestion e.g. "let's..."; or lessens certainty of a decision.

- a (啊),[k] which reduces forcefulness, particularly of an order or question. It can also be used to add positive connotation to certain phrases or inject uncertainty when responding to a question.

- ou (呕; 噢), which signals a friendly warning

- zhe (着; 著), which marks the inchoative aspect, or need for change of state, in imperative sentences. Compare the imperfective aspect marker zhe in the section above)

- le (了), which marks a "currently relevant state". This precedes any other sentence-final particles, and can combine with a (啊) to produce la (啦); and with ou (呕; 噢) to produce lou (喽; 囉).

This sentence-final le (了) should be distinguished from the verb suffix le (了) discussed in the Aspects section. Whereas the sentence-final particle is sometimes described as an inceptive or as a marker of perfect aspect, the verb suffix is described as a marker of perfective aspect.[44] Some examples of its use:

我

wǒ

I

没

méi

no

钱

qián

money

了。

le

PRF

[我沒錢了。]

I have no money now or I've gone broke.

我

wǒ

I

当

dāng

work

兵

bīng

soldier

了。

le

PRF

[我當兵了。]

I have become a soldier.

The position of le in this example emphasizes his present status as a soldier, rather than the event of becoming. Compare with the post-verbal le example given in the Aspects section, wǒ dāng le bīng. However, when answering a question, the ending should be 呢 instead of 了. For example, to answer a question like "你现在做什么工作?" (What's your job now?), instead of using le, a more appropriate answer should be

我

wǒ

I

当

dāng

work

兵

bīng

soldier

呢。

ne

ongoing

[我當兵呢。]

I am being a soldier.

他

tā

He

看

kàn

watch

三

sān

three

场

chǎng

sports-CL

球赛

qiúsài

ballgames

了。

le

PRF

[他看三場球賽了。]

He [has] watched three ballgames.

Compared with the post-verbal le and guo examples, this places the focus on the number three, and does not specify whether he is going to continue watching more games.

The two uses of le may in fact be traced back to two entirely different words.[45][46] The fact that they are now written the same way in Mandarin can cause ambiguity, particularly when the verb is not followed by an object. Consider the following sentence:

妈妈

māma

来

lái

了!

le

[媽媽來了!]

Mom come le

This le might be interpreted as either the suffixal perfective marker or the sentence-final perfect marker. In the former case it might mean "mother has come", as in she has just arrived at the door, while in the latter it might mean "mother is coming!", and the speaker wants to inform others of this fact. It is even possible for the two kinds of le to co-occur:[47]

他

tā

He

吃

chī

eat

了

le

PFV

饭

fàn

food

了。

le

PRF

[他吃了飯了]。

He has eaten.

Without the first le, the sentence could again mean "he has eaten", or it could mean "he wants to eat now". Without the final le the sentence would be ungrammatical without appropriate context, as perfective le cannot appear in a semantically unbounded sentence.

Plural

[edit]Chinese nouns and other parts of speech are not generally marked for number, meaning that plural forms are mostly the same as the singular. However, there is a plural marker men (们; 們), which has limited usage. It is used with personal pronouns, as in wǒmen (我们; 我們, "we" or "us"), derived from wǒ (我, "I, me"). It can be used with nouns representing humans, most commonly those with two syllables, like in péngyoumen (朋友们; 朋友們, "friends"), from péngyou (朋友, "friend"). Its use in such cases is optional.[48] It is never used when the noun has indefinite reference, or when it is qualified by a numeral.[49]

The demonstrative pronouns zhè (这; 這, "this"), and nà (那, "that") may be optionally pluralized by the addition of xiē (些,"few"), making zhèxiē (这些; 這些, "these") and nàxiē (那些, "those").

Cleft sentences

[edit]There is a construction in Chinese known as the shì ... [de] construction, which produces what may be called cleft sentences.[50] The copula shì (是) is placed before the element of the sentence which is to be emphasized, and the optional possessive particle de (的) is placed at the end of the sentence if the sentence ends in a verb, or after the last verb of the sentence if the sentence ends with a complement of the verb. For example:

他

tā

He

是

shì

shi

昨天

zuótiān

yesterday

来

lái

come

[的]。

[de]

[de].

[他是昨天來[的]。]

It was yesterday that he came.

Example with a sentence that ends with a complement:

他

tā

He

是

shì

shi

昨天

zuótiān

yesterday

买

mǎi

buy

[的]

[de]

[de]

菜。

cài

food

[他是昨天買[的]菜。]

It was yesterday that he bought food.

If an object following the verb is to be emphasized in this construction, the shì precedes the object, and the de comes after the verb and before the shì.

他

tā

He

昨天

zuótiān

yesterday

买

mǎi

buy

的

de

de

是

shì

shi

菜。

cài

vegetable.

[他昨天買的是菜。]

What he bought yesterday was vegetable.

Sentences with similar meaning can be produced using relative clauses. These may be called pseudo-cleft sentences.

昨天

zuótiān

yesterday

是

shì

is

他

tā

he

买

mǎi

buy

菜

cài

food

的

de

de

时间。

shíjiān

time

[昨天是他買菜的時間。]

Yesterday was the time he bought food.[51]

Conjunctions

[edit]Chinese has various conjunctions (连词; 連詞; liáncí) such as hé (和, "and"), dànshì (但是, "but"), huòzhě (或者, "or"), etc. However Chinese quite often uses no conjunction where English would have "and".[52]

Two or more nouns may be joined by the conjunctions hé (和, "and") or huò (或 "or"); for example dāo hé chā (刀和叉, "knife and fork"), gǒu huò māo (狗或貓, "dog or cat").

Certain adverbs are often used as correlative conjunctions, where correlating words appear in each of the linked clauses, such as búdàn ... érqiě (不但 ... 而且; 'not only ... (but) also'), suīrán ... háishì (虽然 ... 还是; 雖然...還是; 'although ... still'), yīnwèi ... suǒyǐ (因为 ... 所以; 因為...所以; 'because ... therefore'). Such connectors may appear at the start of a clause or before the verb phrase.[53]

Similarly, words like jìrán (既然, "since/in response to"), rúguǒ (如果) or jiǎrú (假如) "if", zhǐyào (只要 "provided that") correlate with an adverb jiù (就, "then") or yě (也, "also") in the main clause, to form conditional sentences.

In some cases, the same word may be repeated when connecting items; these include yòu ... yòu ... (又...又..., "both ... and ..."), yībiān ... yībiān ... (一边...一边..., "... while ..."), and yuè ... yuè ... (越...越..., "the more ..., the more ...").

Conjunctions of time such as "when" may be translated with a construction that corresponds to something like "at the time (+relative clause)", where as usual, the Chinese relative clause comes before the noun ("time" in this case). For example:[54]

当

dāng

At

我

wǒ

I

回

huí

return

家

jiā

home

的

de

de

时候...

shíhòu...

time

[當我回家的時候...]

When I return[ed] home...

Variants include dāng ... yǐqián (当...以前; 當...以前 "before ...") and dāng ... yǐhòu (当...以后; 當...以後, "after ..."), which do not use the relative marker de. In all of these cases, the initial dāng may be replaced by zài (在), or may be omitted. There are also similar constructions for conditionals: rúguǒ /jiǎrú/zhǐyào ... dehuà (如果/假如/只要...的话, "if ... then"), where huà (话; 話) literally means "narrative, story".

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Several of the common prepositions can also be used as full verbs.

- ^ The first Chinese scholar to consider the concept of a word (词; 詞; cí) as opposed to the character (字; zì) is claimed to have been Shizhao Zhang in 1907. However, defining the word has proved difficult, and some linguists consider that the concept is not applicable to Chinese at all. See San, Duanmu (2000). The Phonology of Standard Chinese. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198299875.

- ^ A more common way to express this would be wǒ bǎ júzi pí bō le (我把橘子皮剥了; 我把橘子皮剝了, "I BA tangerine's skin peeled"), or wǒ bō le júzi pí (我剥了橘子皮; 我剝了橘子皮, "I peeled tangerine's skin").

- ^ 妳 is an alternative character for nǐ (你, "you") when referring to a female; it is used mainly in script written in traditional characters.

- ^ Also used after possessives and relative clauses

- ^ Not the same character as the de used to mark possessives and relative clauses.

- ^ This is a different character again from the two types of de previously mentioned.

- ^ This is similar to the English "by", though it is always followed by an agent.

- ^ Either the verb or the whole verb phrase may be repeated after the negator bù; it is also possible to place bù after the verb phrase and omit the repetition entirely.

- ^ Néng (能) does not mean "may" or "can" in the sense of "know how to" or "have the skill to".

- ^ alternately ya (呀), wa (哇), etc. depending on the preceding sound

References

[edit]- ^ However, like 'dance', 舞 can also be used as a verb: for example, 「項莊舞劍」; "Xiang Zhuang danced with a sword"

- ^ Sun (2006), p. 50.

- ^ a b Etymologically, it was "披星帶月; pī-xīng-dài-yuè(literally "wearing stars like a coat and bringing moon" ). It first appears in a religious poem of Lü Dongbin([1]).

- ^ Melloni, Chiara; Basciano, Bianca (2018). "Reduplication across boundaries: The case of Mandarin". The Lexeme in Theoretical and Descriptive Morphology. 4: 331 – via OAPEN.

- ^ Sun (2006), p. 147.

- ^ Sun (2006), p. 184.

- ^ Sun (2006), p. 185.

- ^ Li (1990), p. 234 ff..

- ^ Sun (2006), p. 161.

- ^ Li & Thompson (1981), pp. 463–491.

- ^ Li (1990), p. 195.

- ^ Sun (2006), p. 159.

- ^ a b Sun (2006), p. 165.

- ^ Sun (2006), p. 188.

- ^ However, classifiers are not commonly used in Classical Chinese, for example 三人行 (sān-rén-xíng, literally "three-person-walk", means "three persons walk together", from Analects).

- ^ ""怹"字的解释 | 汉典". www.zdic.net (in Chinese (China)). Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- ^ "汉语我们和咱们有区别吗?". Retrieved 2022-01-08.

- ^ ""这"字的解释 | 汉典". www.zdic.net (in Chinese (China)).

- ^ ""那"字的解释 | 汉典". www.zdic.net (in Chinese (China)).

- ^ Sun (2006), pp. 152, 160.

- ^ Sun (2006), p. 151.

- ^ Sun (2006), p. 154.

- ^ Sun (2006), p. 163.

- ^ Sun (2006), p. 203.

- ^ "Chapter 84: Order of Object, Oblique, and Verb". World Atlas of Language Structures. 2011.

- ^ Sun (2006), p. 81 ff.

- ^ Sun (2006), p. 85.

- ^ Sun (2006), p. 199.

- ^ Yip & Rimmington (2004), p. 107.

- ^ Li & Thompson (1981), p. 185.

- ^ Sun (2006), p. 70.

- ^ Yip & Rimmington (2004), p. 109.

- ^ Li & Thompson (1981), pp. 29, 234.

- ^ Sun (2006), p. 211.

- ^ Yip & Rimmington (2004), p. 110.

- ^ Sun (2006), pp. 209–211.

- ^ Sun (2006), p. 181.

- ^ Sun (2006), p. 52.

- ^ Sun (2006), p. 53.

- ^ Sun (2006), p. 208.

- ^ Sun (2006), p. 200.

- ^ Sun (2006), p. 205.

- ^ Sun (2006), p. 76 ff.

- ^ Li & Thompson (1981), quoted in Sun (2006), p. 80.

- ^ Li & Thompson (1981), pp. 296–300.

- ^ Chao (1968), p. 246.

- ^ Sun (2006), p. 80.

- ^ Sun (2006), p. 64.

- ^ Yip & Rimmington (2004), p. 8.

- ^ Sun (2006), p. 190.

- ^ Sun (2006), p. 191.

- ^ Yip & Rimmington (2004), p. 12.

- ^ Sun (2006), p. 197.

- ^ Sun (2006), p. 198.

Bibliography

[edit]- Chao, Yuen Ren (1968). A Grammar of Spoken Chinese. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-00219-7.

- Li, Charles N.; Thompson, Sandra A. (1981). Mandarin Chinese: A functional reference grammar. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06610-6.

- Li, Yen-hui Audrey (1990). Order and Constituency in Mandarin Chinese. Springer. ISBN 978-0-792-30500-2.

- Lin, Helen T. (1981). Essential Grammar for Modern Chinese. Cheng & Tsui. ISBN 978-0-917056-10-9.

- Ross, Claudia; Ma, Jing-Heng Sheng (2006). Modern Mandarin Chinese Grammar: A Practical Guide. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-70009-2.

- Sun, Chaofen (2006). Chinese: A Linguistic Introduction. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82380-7.

- Yip, Po-Ching; Rimmington, Don (2004). Chinese: A Comprehensive Grammar. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-15031-0.

- Yip, Po-Ching; Rimmington, Don (2006). Chinese: An Essential Grammar (2nd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-96979-3.

- Lü Shuxiang (吕叔湘) (1957). Zhongguo wenfa yaolüe 中国文法要略 [Summary of Chinese grammar]. Shangwu yinshuguan. OCLC 466418461.

- Wang Li (1955). Zhongguo xiandai yufa 中国现代语法 [Modern Chinese grammar]. Zhonghua shuju.

Further reading

[edit]- W. Lobscheid (1864). Grammar of the Chinese language: in two parts, Volume 2. Office of Daily Press. p. 178. Retrieved 2011-07-06.

- Joshua Marshman, Confucius (1814). Elements of Chinese grammar: with a preliminary dissertation on the characters, and the colloquial medium of the Chinese, and an appendix containing the Tahyoh of Confucius with a translation. Printed at the Mission press. p. 622. Retrieved 2011-07-06.