Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Christian cross variants

View on Wikipedia

The Christian cross, with or without a figure of Christ included, is the main religious symbol of Christianity. A cross with a figure of Christ affixed to it is termed a crucifix and the figure is often referred to as the corpus (Latin for "body").

The term Greek cross designates a cross with arms of equal length, as in a plus sign, while the Latin cross designates a cross with an elongated descending arm. Numerous other variants have been developed during the medieval period.

Christian crosses are used widely in churches, on top of church buildings, on bibles, in heraldry, in personal jewelry, on hilltops, and elsewhere as an attestation or other symbol of Christianity. Crosses are a prominent feature of Christian cemeteries, either carved on gravestones or as sculpted stelae. Because of this, planting small crosses is sometimes used in countries of Christian culture to mark the site of fatal accidents, or, such as the Zugspitze or Mount Royal, so as to be visible over the entire surrounding area. Catholic, Anglican and Lutheran depictions of the cross are often crucifixes, in order to emphasize that it is Jesus that is important, rather than the cross in isolation. Large crucifixes are a prominent feature of some Lutheran churches, e.g. as a rood. However, some other Protestant traditions depict the cross without the corpus, interpreting this form as an indication of belief in the resurrection rather than as representing the interval between the death and the resurrection of Jesus.

Several Christian cross variants are available in computer-displayed text. A Latin cross ("†") is included in the extended ASCII character set,[1] and several variants have been added to Unicode, starting with the Latin cross in version 1.1.[2] For others, see Religious and political symbols in Unicode.

Basic forms

[edit]Basic variants, or early variants widespread since antiquity. A total number of 15 variants.

| Image | Name | Description | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Latin (or Roman) cross | Cross with a longer descending arm, whereby the top of the upright shaft extends above the transverse beam. It represents the cross of Jesus's crucifixion. In Latin, it was referred to as crux immissa or crux capitata. | [3] |

|

Greek cross | A type of cross with arms of equal length, used as a national symbol of Greece, Switzerland, and Tonga. Along with the Latin cross, it is one of the most common Christian forms, in common use by the 4th century. | [4][5] |

|

Byzantine cross | Upright cross with outwardly widening ends. It is often seen in relics from the late antique and early medieval Byzantine Empire (until c. 800) and was adopted by other Christian cultures of the time, such as the Franks and Goths. | [6] |

|

Patriarchal cross (two-bar cross) | Also called an archiepiscopal cross or a crux gemina. A double-cross, with the two crossbars near the top. The upper one is shorter, representing the plaque nailed to Jesus's cross. Similar to the Cross of Lorraine, though in the original version of the latter, the bottom arm is lower. The Eastern Orthodox (Slavic) cross adds a slanted bar near the foot. | [5] |

|

Double cross | The Cross of the eight-point cross-stone ceremony.[clarification needed] | [7] |

|

Cross of Lorraine (two-barred cross) | The Cross of Lorraine consists of one vertical and two horizontal bars. The two-barred cross consists of a vertical line crossed by two shorter horizontal bars. In most renditions, the horizontal bars are "graded" with the upper bar being the shorter, though variations with the bars of equal length are also seen. | [8] |

|

Papal cross | A cross with three bars near the top. The bars are of unequal length, each one shorter than the one below. | [9][10] |

|

Sacred Heart | A depiction of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, featuring flames, a crown of thorns, and a Latin Cross. | [11] |

|

Cross of Salem | Also known as a pontifical cross, it is similar to a patriarchal cross, but with an additional crossbar below the main crossbar, equal in length to the upper crossbar. | [12] |

|

Staurogram | The earlier visual image of the cross, already present in New Testament manuscripts as P66, P45 and P75. | [13] |

|

Chi Rho | The Chi Rho (/ˈkaɪ ˈroʊ/; also known as chrismon) is one of the earliest forms of christogram, formed by superimposing the first two (capital) letters—chi and rho (ΧΡ)—of the Greek word ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ (Christos) in such a way that the vertical stroke of the rho intersects the center of the chi. | [14] |

|

Stepped cross | A cross resting on a base with several steps (usually three), also called a graded or a Calvary cross. This symbol first appears on coinage from the time of Byzantine Emperor Heraclius (r. 610–641). The three steps represent Faith, Hope and Charity, and are sometimes marked Fides (top), Spes (middle) and Caritas (bottom), the Latin forms of these words. | [15] |

|

Jerusalem cross | Also known as the Crusader's Cross. A large cross with a smaller cross in each of its angles. It was used as a symbol of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. | [16][17] |

|

Ringed cross | A cross featuring a ring or nimbus. This type has several variants, including the cruciform halo and the Celtic cross. A cruciform halo is used to represent the persons of the Holy Trinity, especially Jesus, and it was used especially in medieval art. | [18][19] |

|

Forked cross | A cross in the form of the letter Y that gained popularity in the late 13th or early 14th century in the German Rhineland. Also known as a crucifixus dolorosus, furca, ypsilon cross, Y-cross, thief's cross or robber's cross. | [20][21] |

Saints' crosses

[edit]| Image | Name | Description | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Cross of Saint Peter | A cross with the crossbeam placed near the foot, that is associated with Saint Peter because of the tradition that he was crucified head down. In modern culture, the cross is often also associated with Satanism or anti-Christian sentiment. | [22][23] |

|

Tau cross | A T-shaped cross. Also called the Saint Anthony's cross, the Saint Francis' cross and crux commissa. | [24] |

|

Saltire or crux decussata (Saint Andrew's cross) | An X-shaped cross associated with St. Andrew, patron of Scotland, and so a national symbol of that country. The shape is that of the cross on which Saint Andrew is said to have been martyred. Also known as St. Andrew's Cross or Andrew Cross. | [5][25] |

|

Brigid's cross | Bride's cross, also known as Brigid's cross or Brighid's cross, these are usually woven of rushes or wheat stalks. They can be Christian or pagan symbols depending on context. They may have three or four arms. | [26][27] |

|

Saint George's Cross | Sometimes associated with Saint George, the military saint, often depicted as a crusader from the Late Middle Ages, the cross has appeared on many flags, emblems, standards, and coats of arms. Its first documented use was as the ensign of the Republic of Genoa, whereafter it was used successively by the crusaders. Notable uses are on the Flag of England and the Georgian flag. | [28][29] |

|

Anchored cross | A stylized cross in the shape of an anchor. A varied symbol, the mariner's cross is also referred to as the cross of Saint Clement in reference to the way he was martyred, or the cross of Hope, as a reference to Hebrews 6:19. It traditionally symbolizes security, hope, steadfastness, and composure. | [5][30] |

|

Pectoral cross of Cuthbert | A relic associated with Cuthbert. | [31][32] |

|

Cross of Saint Gilbert (Portate cross) | A cross is usually shown erect, as it would be when used for crucifixion. The Portate Cross differs in that it is borne diagonally, as it would be when the victim bears the cross-bar over his shoulder as he drags it along the ground to the crucifixion site. | [33] |

|

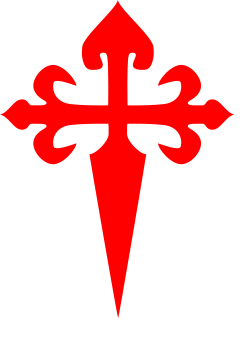

Cross of Saint James (sword cross) |

A red Cross of Saint James with flourished arms, surmounted with an escallop, was the emblem of the twelfth-century Galician and Castillian military Order of Santiago, named after Saint James the Greater. | [34][35] |

|

Saint Julian Cross | A Cross Crosslet tilted at 45 degrees. It is sometimes referred to as the Missionary Cross. | [7] |

|

Grapevine cross (Saint Nino's cross) | Also known as the cross of Saint Nino of Cappadocia, who Christianised Georgia. | [36] |

|

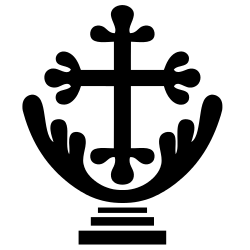

Saint Thomas cross | The ancient cross used by Saint Thomas Christians (also known as Syrian Christians or Nasrani) in Kerala, India. | [37] |

|

Cross of Saint Philip | A sideways cross associated with Philip the Apostle due to a story of him being crucified sideways. | [38] |

|

Cross of Saint Florian | The cross of Saint Florian, the patron saint of firefighters, is often confused with the Maltese Cross. | [39] |

|

Catherine wheel | Seven Catherines have been granted sainthood. This cross is composed of wagon wheels and is attributed to (at least) three saints: Saint Catherine of Alexandria, Saint Jarlath and Saint Quentin. | [40][41] |

|

Cross of Saint John | A Latin cross with the crossing point, starting initially as wide permanent and widening only at its end to the outside arms. It is not to be confused with the Maltese cross, also known as the St. John's cross. In heraldry, it is a common figure in coat of arms. | |

|

Cross of Saint Chad | The cross is a combination of a Potent Cross and Quadrate Cross, which appears in the arms of the episcopal see of Lichfield & Coventry. | [42] |

|

Cross of Jeremiah | The cross of the prophet Jeremiah, also known as the "Weeping Prophet". | [7] |

|

Cross of Lazarus | A green Maltese cross associated with St. Lazarus. | [43] |

|

Cross of Saint Maurice | A white cross bottony associated with Saint Maurice. | [44] |

Denominational or regional variants

[edit]| Image | Name | Description | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Cross of the Angels | Symbol of the city of Oviedo and the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Oviedo. Donated by king Alfonso II of Asturias in 808. | [45][46] |

|

Armenian cross | Symbol of the Armenian Apostolic Church, and a typical feature of khachkars. Also known as the "Blooming Cross" owing to the trefoil emblems at the ends of each branch. A khachkar (cross-stone) is a popular symbol of Armenian Christianity. | [47] |

|

Bolnisi cross | Ancient Georgian cross and national symbol from the 5th century AD. | [48] |

|

Caucasian Albanian cross | Ancient Caucasian Albanian cross and national symbol from the 4th century AD. | |

|

Cross of Burgundy | A saw toothed form of the St. Andrews cross, symbolizing the rough branches he was crucified on. A historic symbol of the Burgundy region, dating back to the 15th century when supporters of the Duke of Burgundy adopted the badge to show allegiance in the Armagnac–Burgundian Civil War. | [49] |

|

Byzantine cross-crosslet | A Byzantine cross variant seen on several coins and artifacts of the Late Macedonian, Doukas, and Early Komnenos dynasties of the Byzantine Empire (c.950–1092). Combines aspects of the Patriarchal cross, Greek cross, and Calvary cross into a unique variation that may have inspired the later Jerusalem cross. | |

|

Canterbury cross | A cross with four arms of equal length which widen to a hammer shape at the outside ends. Each arm has a triangular panel inscribed in a triquetra (three-cornered knot) pattern. There is a small square panel in the center of the cross. A symbol of the Anglican and Episcopal Churches. | [50] |

|

Celtic cross | Essentially a Greek or Latin cross, with a circle enclosing the intersection of the upright and crossbar, as in the standing High crosses. | [51] |

|

Crux Ansata | Shaped like the letter T usually surmounted by a circle. Not to be confused with an Ankh which is usually surmounted by a drop shape. Adopted from the Egyptian Ankh by the Copts (Egyptian Christians) and Ethiopian Orthodox Christians. | [52] |

|

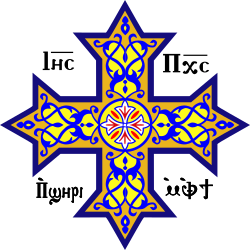

Coptic cross | The original Coptic cross has its origin in the Coptic ankh. Many Coptic Christians have the cross tattooed as a sign of faith. | [53][54] |

|

New Coptic cross | This new Coptic cross is the cross currently used by the Coptic Catholic Church and the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria. | |

|

Lalibela cross | This is one of many variations of Ethiopian crosses and generally made up of latticework, used by Ethiopian Christians and associated with the churches of Lalibela. | [55] |

|

Cossack cross | A type of cross used by Zaporozhian Cossacks and the Armed Forces of Ukraine. Frequently used in Ukraine as a memorial sign to fallen soldiers and in military awards. | [56] |

|

East Syrian cross | Church of the East cross. | |

|

Huguenot cross | The cross represents not only the death of Christ but also victory over death and impiety. This is represented also in the Maltese cross. It is boutonné, the eight points symbolising the eight Beatitudes (Matthew 5:3–12) Between the arms of the cross is the stylised fleur-de-lys (on the French Coat of Arms), each has 3 petals; the total of twelve petals of the fleur-de-lys signify the twelve apostles. Between each fleur-de-lys and the arms of the Maltese cross with which it is joined, an open space in the form of a heart, the symbol of loyalty, suggests the seal of the French Reformer, John Calvin. The pendant dove symbolises the Holy Spirit (Romans 8:16). In times of persecution a pearl, symbolizing a teardrop, replaced the dove. | [57] |

|

Maltese cross | An eight-pointed cross having the form of four V-shaped elements, each joining the others at its vertex, leaving the other two tips spread outward symmetrically. It is the cross symbol associated with the Order of St. John since the Middle Ages, shared with the traditional Knights Hospitaller and the Sovereign Military Order of Malta, and by extension with the island of Malta. | [39][58] |

|

Maronite cross | Cross of the Syriac Maronite Church. Reminiscent of the Papal cross and cross of Lazarus. | [59][60] |

|

Nestorian cross | In Eastern Christian art found on tombs in China, these crosses are sometimes simplified and depicted as resting on a lotus flower or on a stylized cloud. | [61][62] |

|

Occitan cross | Based on the counts of Toulouse's traditional coat of arms, it soon became the symbol of Occitania as a whole. | [63] |

|

"Carolingian cross" | Cross of triquetras, called "Carolingian" by Rudolf Koch for its appearance in Carolingian-era art. | [64] |

|

Rose Cross | A cross with a rose blooming at the center. The central symbol to all groups embracing the philosophy of the Rosicrucians. | [65] |

|

Serbian cross | A Greek cross with four Cyrillic S's (C) in each of its angles, inspired by the imperial motto of the Palaiologos dynasty, but with the meaning of "Only unity saves the Serbs" (Само Слога Србина Спасава), generally attributed to Serbian patron saint, St. Sava. A national symbol of Serbia and symbol of the Serbian Orthodox Church. The cross is used on the coat of arms of Serbia and the flag of Serbia. | [66] |

|

Orthodox cross | Also known as the Russian cross, Slavic, Slavonic cross, or Eastern Orthodox, Russian Orthodox cross. A three-barred cross in which the short top bar represents the inscription over Jesus' head, and the lowest (usually slanting) short bar, placed near the foot, represents his footrest (in Latin, suppedaneum). This cross existed in a slightly different form (with the bottom crossbeam pointing upwards) in Byzantium, and it was changed and adopted by the Russian Orthodox Church and especially popularized in the East Slavic countries. | [67] |

|

Russian cross | Six-pointed variant of Russian Orthodox cross. Also called the suppedaneum cross, meaning under-foot cross, referring to the bar where Jesus put his feet while crucified. | [68] |

|

Macedonian Cross, also known as Veljusa Cross. | Macedonian Christian symbol. | [69] |

|

Anuradhapura cross | A symbol of Christianity in Sri Lanka. | [70][71][72] |

|

Nordic cross/Scandinavian cross | A sideways cross typically used on flags of Scandinavian countries, originally derived from the flag of Denmark. | [73][74] |

|

West Syrian cross | Syriac Orthodox cross. | [75] |

|

Gion-mamori mon | The mon of the Gion Shrine, depicting two crossed amulets and a horn, adopted by Kakure Kirishitans persecuted under the Tokugawa Shogunate. | [76] |

|

Troll cross | A Christian cross engraved on objects in Scandinavia to ward off evil spirits such as trolls. | [77] |

|

Cross of Alcoraz | A red cross surrounded by four moor's heads, used in the coat of arms of Aragon and the flag of Sardinia. | [78] |

Non-denominational symbols

[edit]| Image | Name | Description | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Cross and Crown | A Christian symbol used by various Christian denominations, particularly the Bible Student movement and the Church of Christ, Scientist. It has also been used in heraldry. The emblem is often interpreted as symbolizing the reward in heaven (the crown) coming after the trials in this life (the cross) (James 1:12). | [79][80] |

|

Gamma cross | A Greek cross. Each gamma represents one of the four Evangelists, radiating from the central Greek Cross, which represents Christ. The term "Gamma cross" can refer to either a voided cross or a swastika. | [81] |

|

Cross of passion | The Passion Cross has sharpened points at the end of one or more of the cross members. It is also referred to as the Cross of Suffering representing the nails that Christ suffered at his Crucifixion. In heraldry, it is known as the Cross aiguisée. | [82] |

Modern innovations

[edit]| Image | Name | Description | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Marian Cross | A term invented to refer to Pope John Paul II's combination of a Latin cross and the letter M, representing Mary being present on Calvary. | [83] |

|

Off Center Cross of Christian Universalism. | The off-center cross was invented in late April, 1946, in a hotel room in Akron, Ohio, during the Universalist General Assembly, where a number of Universalist ministers pooled their ideas. | [84][85] |

| Ordnance Survey cross symbols | Used on Ordnance Survey maps to represent churches and chapels. A cross on a filled square represents a church with a tower; and a cross on a filled circle represents a church with a spire. Churches without towers or spires are represented by plain Greek crosses. These symbols also now refer to non-Christian places of worship, and the cross on a filled circle also represents a place of worship with a minaret or dome. | [86] | |

|

Cross of Camargue | Symbol for the French region of Camargue, created in 1926 by the painter Hermann-Paul at the request of Folco de Baroncelli-Javon to represent the "Camargue nation" of herdsmen and fishermen. It embodies the three theological virtues of Christianity: faith (represented by tridents of gardians on a Christian cross), hope (represented by the anchor of sinners), and charity (represented by the heart of The Three Marys). | [87] |

|

Ecumenical cross | Symbol of ecumenism, the concept that all church denominations should work together to promote Christian unity. Adopted in 1948, symbolizing the message of the ecumenical movement and tracing its origins to the gospel story of the calling of the disciples by Jesus and the stilling of the storm on Lake Galilee. | [88] |

Crosses of Orders

[edit]| Image | Name | Description | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Iron Cross | A German military cross originating as a military decoration in Prussia. Later used in various military and security force decorations in the unified German Empire, Weimar Republic, Nazi Germany and the modern Federal Republic, particularly as a symbol of the German Air Force (Luftwaffe). | [89] |

|

Order of Christ Cross | A red Greek cross starting initially as wide permanent and widening only at its end to the outside arms, with a white inner simple Greek cross. Not to be confused with the Cross of Saint John nor the Maltese cross. It's the insignia of the Military Order of Christ (Portuguese: Ordem Militar de Cristo), former Knights Templar order as it was reconstituted in Portugal after the Templars were abolished on 22 March 1312, being the Grand Master the current President of Portugal. It's an honorific symbol of the Portuguese Navy, and current symbol of the Portuguese Air Force. | [90] |

|

Supreme Order of Christ Cross | A red Latin cross starting initially as wide permanent and widening only at its end to the outside arms, with a white inner simple Latin cross. Not to be confused with the Cross of Saint John nor the Maltese cross. It's the symbol of the Papal Supreme Order of Christ (Italian: Ordine Supremo del Cristo), the highest order of chivalry awarded by the Pope, and it's the Papal parallel to the Order of Christ in both Portugal and Brazil. | [90] |

Types of artifacts

[edit]| Image | Name | Description | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Crucifix | A cross with a representation of Jesus' body hanging from it. It is primarily used in Catholic, Anglican, Lutheran, and Eastern Orthodox churches (where the figure is painted), and it emphasizes Christ's sacrifice—his death by crucifixion. It is also used on most rosaries, a Catholic tool for prayer. | [91] |

|

Altar cross | A cross on a flat base to rest upon the altar of a church. The earliest known representation of an altar cross appears in a miniature in a 9th-century manuscript. By the 10th century such crosses were in common use, but the earliest extant altar cross is a 12th-century one in the Great Lavra on Mount Athos. Mass in the Roman Rite requires the presence of a cross (more exactly, a crucifix) "on or close to" the altar. Accordingly, the required cross may rest on the reredos rather than on the altar, or it may be on the wall behind the altar or be suspended above the altar. | [92][93] |

|

Blessing cross | Used by priests of the Eastern Catholic, Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox Churches to bestow blessings upon the faithful. | [94] |

|

Cross necklace | A small cross or crucifix worn as a pendant on a necklace. | [95][96] |

|

High cross | A large stone cross that is richly decorated. From the 19th century, many large modern versions have been erected for various functions, and smaller Celtic crosses have become popular for individual grave monuments, usually featuring only abstract ornament, usually interlace. | [97] |

|

Processional cross | Used to lead religious processions; sometimes, after the procession it is placed behind the altar to serve as an altar cross. | [98] |

|

Crux gemmata | A cross inlaid with gems with the Greek letters Alpha and Omega suspended from the arms. | [99] |

|

Pectoral cross | A large cross worn in front of the chest (in Latin, pectus) by some clergy. | [100] |

|

Rood | Large crucifix high in a church; most medieval Western churches had one, often with figures of the Virgin Mary and John the Evangelist alongside, and often mounted on a rood screen | [101] |

|

Globus cruciger | An artifact consisting of a golden orb (representing the world) surmounted by a cross, used in Imperial imagery since the Late Roman Empire. The globus cruciger made its way into the Imperial regalia of the Byzantine Empire, and was later adopted by the Papacy, Holy Roman Empire, and many other countries of the Late Medieval and Early Modern era to signify Imperial authority over Christendom. | [102][103] |

|

Conciliation cross | A type of cross erected where murders or accidents have occurred, typically in Central Europe. | [104] |

|

Wayside cross | A cross erected near a path near the edge of a field or forest serve as waymarks for walkers or pilgrims. | [105][106] |

|

Battlefield cross | A cross made to commemorate a military serviceperson killed in action, made from their rifle, boots, and helmet. It is a military tradition in the United States. | [107] |

Unicode

[edit]For use in documents made using a computer, there are Unicode code-points for multiple types of Christian crosses.

- U+16ED ᛭ RUNIC CROSS PUNCTUATION

- U+205C ⁜ DOTTED CROSS

- U+2626 ☦ ORTHODOX CROSS

- U+2627 ☧ CHI RHO

- U+2628 ☨ CROSS OF LORRAINE

- U+2629 ☩ CROSS OF JERUSALEM

- U+2670 ♰ WEST SYRIAC CROSS

- U+2671 ♱ EAST SYRIAC CROSS

- U+2719 ✙ OUTLINED GREEK CROSS

- U+271A ✚ HEAVY GREEK CROSS

- U+271B ✛ OPEN CENTRE CROSS

- U+271C ✜ HEAVY OPEN CENTRE CROSS

- U+271D ✝ LATIN CROSS

- U+271E ✞ SHADOWED WHITE LATIN CROSS

- U+271F ✟ OUTLINED LATIN CROSS

- U+2720 ✠ MALTESE CROSS

- U+01F548 🕈 CELTIC CROSS

There are code points for other crosses in the block Miscellaneous Symbols and Pictographs, mainly variants of the Greek cross, but their usage may be limited by availability of a computer font that can display them.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "ASCII Code—The extended ASCII table". ASCII-Code.com. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ "Unicode Character "✝" (U+271D)". Compart.com. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ Curl, James Stevens (2015). "Cross: Latin" in Oxford Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture. Oxford University Press. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-19-860678-9. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ "Greek cross". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ a b c d "Meek Baptist Church - Historical Crosses". Meek Baptist Church. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ Processional Cross, ca. 1000–1050, Metropolitan Museum of Art, retrieved 4 March 2025

- ^ a b c "Meaning of the Christian Cross". Lord's Guidance. 24 August 2023. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "This cross was chosen by Charles de Gaulle as a response to Hitler's swastika". Aleteia — Catholic Spirituality, Lifestyle, World News, and Culture. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "Papal Cross". Ancient Symbols. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "Definition of PAPAL CROSS". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "Sacred Heart | Symbol, Meaning, Feast of, History, & Devotion". Encyclopædia Britannica. 20 January 2025. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "The Salem Cross". www.seiyaku.com. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ Hutado, Larry (2006). "The staurogram in early Christian manuscripts: the earliest visual reference to the crucified Jesus?". In Kraus, Thomas (ed.). New Testament Manuscripts. Leiden: Brill. pp. 207–26. hdl:1842/1204. ISBN 978-90-04-14945-8.

- ^ "What Is the Meaning of the Chi Rho Symbol?". Christianity.com. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ Treasures of Britain and Treasures of Ireland (1976 ed.). Drive Publications Limited. p. 678.

- ^ "What Is the Jerusalem Cross?". National Catholic Register. 17 November 2024. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ Giannopoulos, Bill (17 November 2024). "The Jerusalem Cross: Pete Hegseth's Tattoo And The Significance Of Christian And Greek Symbols". Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ Herren, Michael W.; Brown, Shirley Ann (2002). Christ in Celtic Christianity: Britain and Ireland from the Fifth to the Tenth Century. Boydell Press. pp. 192–200. ISBN 0851158897.

- ^ James-Griffiths, Paul (7 May 2021). "Symbolism of the Celtic Cross". Christian Heritage Edinburgh. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "Crucifixus Dolorosus or the Forked Crucifix from c. 1300". Medieval Histories. 17 April 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "Forked Cross". www.seiyaku.com. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ Molina, Hector. "What Does an Upside-Down Cross Mean?". Catholic Answers. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "What Does an Upside Down Cross (Inverted) Really Mean?". Christianity.com. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ Ryan, George (15 May 2020). "Did You Know? The History Behind the Tau Cross & the Staurogram". uCatholic. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "Saltire". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "St Brigid's Crosses". National Museum of Ireland. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "St. Brigid's Day". Ulster Folk Museum. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "Identity parade: What do flags say about nations – and human". The Independent. 22 April 2010. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "Cross of St. George". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "What is the origin of the anchor as a Christian symbol, and why do we no longer use it?". Christianity Today. 8 August 2008. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "The treasures of Saint Cuthbert". Durham Cathedral. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "The Keeper of the Shrine". Durham World Heritage Site. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "Portate Cross". www.seiyaku.com. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "The Cross of Santiago: Its origin and meaning". vivecamino.com. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ Pombo, Maite (30 November 2023). "The Cross of St. James (or Cruz de Santiago in Spanish): Origin, Meaning and History". Pilgrim. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ Webley, Kayla (19 April 2010). "The Grapevine Cross". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "NSC NETWORK—Analogical review on Saint Thomas Cross—The symbol of Nasranis—Interpretation of the Inscriptions". Nasrani.net. 29 February 2008. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ Roberts, George (11 October 2020). "Philip's faithfulness in the face of challenge". Grow Christians. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ a b "The Maltese vs. Florian cross: Which one is correct?". FireRescue1. 11 March 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "Recognising saints: wheel | Saints | National Gallery, London". www.nationalgallery.org.uk. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: St. Catherine of Alexandria". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "St. Chad's Cross". www.seiyaku.com. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "Insignia and Cross". The Grand Priory of America.

- ^ "Knight's Cross of St. Maurice and St. Lazarus - Finest Known". 13 April 2023. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "The Cathedral of Oviedo". Asturias.com. Archived from the original on 26 January 2025. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ Schlunk, Helmut (1 June 1950). "The Crosses of Oviedo: A Contribution to the History of Jewelry in Northern Spain in the Ninth and Tenth Centuries". The Art Bulletin. 32 (2): 91–114. doi:10.1080/00043079.1950.11407915. ISSN 0004-3079.

- ^ Russell, J. R. (1986). "ARMENIA AND IRAN iii. Armenian Religion". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica. Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. II/4: Architecture IV–Armenia and Iran IV. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 438–444. ISBN 978-0-71009-104-8.

- ^ "Bolnisi". www.heraldika.ge. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ Moncada, Andrea (25 October 2021). "What's With All the Imperial Spanish Flags in Peru (and Elsewhere)?". Americas Quarterly. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "The Canterbury Cross". T & B Cousins & Sons. 2009. Archived from the original on 14 January 2010. Retrieved 23 February 2010.

- ^ Sunshine, Glenn (16 March 2024). "The Story of the Celtic Cross". Every Square Inch Ministries. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ Muc, Agnieszka (2008). "Cruz Ansata. Remarks on the Meaning of the Symbol and Its Use on Coptic Funerary Stelae". Studies in Ancient Art and Civilization. 12: 97–103.

- ^ Liungman, Carl G. (2004). Symbols: Encyclopedia of Western Signs and Ideograms. Ionfox AB. p. 228. ISBN 9789197270502. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- ^ "The Story Behind the Coptic Cross Tattoo". Coptic Solidarity. 3 March 2022. Retrieved 14 October 2024.

- ^ "The Ethiopian Cross". www.seiyaku.com. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "Cross Cossack fighters for freedom". discover.ua. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ Hunnewell, Sumner. "The Huguenot Cross". The National Huguenot Society. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "The Origin of the Maltese Cross | Merrimack NH". www.merrimacknh.gov. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "The Maronite Cross". www.seiyaku.com. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ The Maronite Antiochian Cross. Our Lady of Lebanon Co Cathedral - Sydney. 2 September 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2025 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Mark W. Brown Nestorian Cross Collection". Drew University. 19 August 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "Nestorian Cross". www.seiyaku.com. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "The Cross of Toulouse". www.midi-france.info. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "Rudolf Koch: Christian Symbols". catholic-resources.org. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "What Does the Rosy Cross Mean?". Learn Religions. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "Flag of Serbia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "The Russian Orthodox Cross - Questions & Answers". Orthodox Church in America. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "Suppedaneum Cross". www.seiyaku.com. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ Parmeniov (27 September 2022). "The Macedonian Cross". History.mk. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ Oswald Gomis, Emiretus (22 April 2011). "The Cross of Anuradhapura". Daily News. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- ^ Pinto, Leonard (20 September 2013). "A Brief History Of Christianity In Sri Lanka". Colombo Telegraph. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- ^ Antony, Thomas (29 February 2008). "Analogical review on Saint Thomas Cross- The symbol of Nasranis-Interpretation of the Inscriptions". Nasrani Syrian Christians Network. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- ^ "The Nordic flags | Nordic cooperation". www.norden.org. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "Why do all Nordic flags have the same design?". The Viking Herald. 28 April 2024. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "♰ West Syriac Cross Emoji". www.sweasy26.com. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ Boxer, C.R. (1951). The Christian Century in Japan: 1549–1650. University of California Press. p. vi.

- ^ Ålenius, Nils (1940). "De uppländska portlidersstolparna". Årsboken Uppland (PDF). Uppland, Sweden: aarsbokenuppland.se. pp. 51–60.

- ^ CONDE, Rafael, "La bula de plomo de los reyes de Aragón y la cruz «de Alcoraz»", Emblemata, XI (2005), pp. 59–82 ISSN 1137-1056.

- ^ "The history of the Cross and Crown emblem". Mary Baker Eddy Library. 10 March 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "Cross and Crown". The United Methodist Church. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "Gammadion Cross". www.seiyaku.com. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "Passion Cross". www.seiyaku.com. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "Mater Dei Apostolate — Logo". Mater Dei Apostolate. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "The Off-Center Cross". The New Massachusetts Universalist Convention. Archived from the original on 28 December 2018. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ^ "About the CUA logo". Christian Universalist Association. 26 May 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ Ordnance Survey map legend, accessed 13 May 2016

- ^ Verlinden, Patrick (30 March 2016). "Croix Camarguaise". Provence 7 (in French). Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "About the WCC logo". World Council of Churches. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "Iron Cross | German Military Award & History". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ a b "Order of Christ Cross". www.seiyaku.com. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "Crucifix | Definition, Images, & Symbol". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "General Instruction of the Roman Missal, 117" (PDF). Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ Tribe, Shawn. "A Florentine Altar Cross from the Early 1500's". Liturgical Arts Journal. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "Coptic Orthodox Blessing Cross - History of the Catholic Church in Singapore -". - History of the Catholic Church in Singapore -. 2 July 2019. Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "Cardinal Keith O'Brien urges Christians to 'proudly' wear cross". BBC News. 4 April 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "The return of the cross pendant". Harper Bazar. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ Werner, Martin (1990). "On the Origin of the Form of the Irish High Cross". Gesta. 29 (1): 98–110. doi:10.2307/767104. ISSN 0016-920X. JSTOR 767104.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ "Dictionary : CRUX GEMMATA". www.catholicculture.org. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Pectorale". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Rood". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ Pyrgies, Joanna (20 February 2021). "'Globus cruciger' in the Hands of Monarchs". ARCHAEOTRAVEL.eu. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "Globus Cruciger". Ancient Symbols. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "Jeden z nejvyšších kamenných smírčích křížů v Čechách najdete na Libinách u Jaroměře" (in Czech). Czech Radio. 4 January 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ Scott-Walker, Johnny (2 January 2024). "Wayside Crosses, What Exactly Are They?". RuralHistoria. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ Joly, Diane. "Wayside Crosses". www.ameriquefrancaise.org (in French). Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ "The battlefield cross". National Museum of American History. 21 May 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2025.

Christian cross variants

View on GrokipediaHistorical Origins

Pre-Christian Influences and Early Adoption

The cross shape, consisting of two intersecting lines, appeared in pre-Christian artifacts across various cultures, often as a geometric or symbolic motif rather than an instrument of execution. Archaeological evidence from ancient Egypt includes the ankh, a tau-shaped cross topped with a loop, used as a hieroglyph for life and held by deities in temple reliefs dating back to the Old Kingdom around 2500 BCE.[8] Similarly, tau forms without the loop appear on Egyptian monuments and in Mesopotamian contexts, potentially associated with fertility symbols or the god Tammuz, as noted in historical analyses of Chaldean iconography predating the Common Era by millennia.[9] These usages, while visually akin to later Christian variants, served distinct purposes tied to life, resurrection, or cosmic order, with no direct causal link to Christian symbolism established beyond superficial resemblance.[10] In the Roman Empire, the cross—specifically the crux immissa or latina—functioned primarily as a tool of capital punishment, with records of its use for crucifixion tracing to the 6th century BCE under Persian influence and widespread by the 1st century CE.[1] Early Christians, viewing crucifixion as a degrading Roman penalty, avoided the cross as a visual emblem in the first centuries, favoring abstract symbols like the ichthys or Chi-Rho monogram, as evidenced by catacomb art from the 2nd-3rd centuries CE.[1] The earliest integration appears in the staurogram, a ligature of tau (Τ) and rho (Ρ) from Greek stauros (cross), found in New Testament papyri such as P66 and P75 dated to circa 200 CE, representing an abbreviated crucifixion image predating figural depictions by two centuries.[11] Adoption accelerated post-312 CE following Emperor Constantine's reported vision of the Chi-Rho with "In hoc signo vinces" before the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, leading to the cross's incorporation into military standards (labarum) and public veneration after the Edict of Milan in 313 CE legalized Christianity.[12] By the 4th century, the gesture of tracing the cross on the forehead or body emerged in baptismal rites, as described by Tertullian around 200 CE, evolving into a protective sign against evil.[12] The first surviving public crucifix image dates to the 5th-century doors of Santa Sabina Basilica in Rome, marking the symbol's shift from esoteric abbreviation to triumphant emblem of resurrection, detached from pre-Christian connotations through theological reframing centered on Christ's atonement.[1]Development in Early Christianity

Early Christians largely avoided depicting the cross as a symbol due to its association with the humiliating Roman punishment of crucifixion, reserved for slaves and criminals, preferring indirect representations such as the fish (ichthys), anchor, or the Chi-Rho monogram.[1] The earliest explicit Christian reference to the cross in visual form appears in the staurogram, a ligature combining the Greek letters tau (Τ) and rho (Ρ) to abbreviate stauros (σταυρός, meaning "cross" or "stake"), which visually evoked the crucifixion with the tau forming the crossbeam and the rho's loop suggesting Christ's head.[13] This symbol emerged in New Testament papyri around the late 2nd to early 3rd centuries AD, predating other crucifixion imagery by approximately 200 years and serving as the initial Christian adaptation of cross iconography in manuscripts like Papyrus 66 and Papyrus 75.[1] The practice of making the sign of the cross, initially a small trace on the forehead, originated in apostolic times and was used in baptismal rites and prayers by the 2nd century, as attested by Tertullian around 200 AD, evolving from a gesture of blessing to a fuller sign across the body by the 4th century.[12] This tactile symbolism preceded widespread visual depictions, reflecting a theological emphasis on the cross's redemptive power without overt imagery that might invite persecution. The tau cross, a T-shaped form linked to Ezekiel 9:4's protective mark, gained traction among some early groups like the Franciscans later, but in the primitive church, it aligned with the staurogram's tau element as a precursor to basic cross variants.[14] The cross's prominence surged after Emperor Constantine's vision before the Battle of the Milvian Bridge on October 28, 312 AD, where he reportedly saw a cross-like symbol with the words "In this sign, conquer," leading to the adoption of the labarum standard incorporating the Chi-Rho overlaid on a cross, marking the transition from secretive symbols to public Christian emblems under imperial patronage.[1] By the 4th century, post-Edict of Milan (313 AD), crosses appeared in church architecture and art, such as the gemmed cross (crux gemmata) in mosaics, evolving toward the equal-armed Greek cross in Eastern traditions and the elongated Latin cross in Western ones, though distinct variants remained fluid until later standardization.[15] Devotion to the cross as an artifact, including veneration of the True Cross fragments purportedly discovered by Helena in 326 AD, further entrenched its role, shifting from abstract monograms to physical representations by the mid-4th century.[16]Medieval Evolution and Standardization

In the medieval period, the Christian cross evolved from simpler early forms into more elaborate variants tailored to ecclesiastical hierarchy, regional traditions, and emerging heraldic practices, reflecting both theological symbolism and practical uses in liturgy and governance. The patriarchal cross, featuring two horizontal bars with the upper shorter than the lower, originated in the 10th century within the Byzantine Empire as a mark of patriarchal authority, later adopted in Western contexts for archbishops to denote spiritual jurisdiction.[17] This design symbolized the dual nature of Christ's kingship and priesthood, appearing on seals, croziers, and processional standards by the 11th century.[18] Concurrently, the Latin cross (crux immissa), with its extended lower vertical arm evoking the footrest of the crucifixion, solidified as the dominant form in Western Europe, while the equal-armed Greek cross prevailed in Eastern Orthodox architecture and icons, underscoring doctrinal divergences post-Schism in 1054.[19] The Crusades catalyzed further innovation, particularly the Jerusalem cross—a large central cross potent surrounded by four smaller Greek crosses—adopted as the emblem of the Kingdom of Jerusalem following its establishment in 1099 by Godfrey de Bouillon, representing the five wounds of Christ or the spread of the Gospel to the world's quarters.[20] This variant appeared on banners, coins, and seals of Crusader states, blending military and devotional elements.[21] Heraldry's rise around 1150 in Western Europe standardized stylized crosses for armorial bearings, yielding forms like the cross pattée (broadened ends) and cross fleury (floral tips), used to distinguish knights and orders such as the Templars, who incorporated the patriarchal cross into their insignia.[22] By the 12th century, ornate decorations proliferated, as seen in the Irish Cross of Cong (1123), crafted with gold filigree and crystal, exemplifying Celtic influences on processional crosses that transitioned toward altar crucifixes by the 13th-14th centuries.[19] Standardization accelerated through liturgical reforms and artistic realism; the Quinisext Council of 692 mandated realistic depictions over allegorical ones, paving the way for suffering Christ figures on crucifixes by the 8th-9th centuries, with full agony emphasized in 13th-century works like those of Cimabue.[17] The Tau cross, resembling the Greek letter τ, gained renewed prominence via the Franciscan order in the 13th century, inspired by St. Francis of Assisi's vision and its association with Ezekiel 9:4 as a mark of the faithful.[19] These developments entrenched cross variants in medieval Christian identity, from monastic seals to cathedral facades, balancing symbolic universality with contextual specificity.[17]Basic Forms

Latin Cross

The Latin cross, known technically as the crux immissa, features a vertical post intersected by a horizontal beam positioned approximately two-thirds of the way up from the base, creating a longer lower arm and shorter upper segment above the crossbeam. [19] This design distinguishes it from the equal-armed Greek cross and is traditionally viewed as mirroring the Roman crucifixion apparatus employed during the execution of Jesus Christ, dated to circa AD 30–33.[23] Roman practice typically involved a fixed upright stake (stipes) with a removable crossarm (patibulum) carried by the condemned, aligning with the Latin cross's proportions for stability and elevation.[23] Early Christian adoption of the cross as a symbol was limited due to its connotation of criminal punishment under Roman law, with simpler signs like the staurogram or Chi-Rho monogram preferred until the 4th century.[17] Following Emperor Constantine's reported vision of the cross before the Battle of the Milvian Bridge on October 28, 312 AD, and the Edict of Milan in 313 AD legalizing Christianity, the Latin cross emerged as a prominent emblem, appearing on coins, standards, and architecture.[17] By the late 4th century, it symbolized victory over death through Christ's resurrection, supplanting earlier abstract representations.[17] In Western Christianity, encompassing Roman Catholic and Protestant denominations, the Latin cross serves as the primary icon of the faith, denoting redemption and sacrifice.[24] Its form influenced church architecture, with naves extending longitudinally to evoke the cross's shape, as seen in basilicas from the 4th century onward.[19] While no canonical proportions exist, artistic depictions often approximate a 3:2 height-to-width ratio for the vertical beam relative to the horizontal, emphasizing the vertical ascent to heaven.[23] In contrast to Eastern Orthodox variants with additional slanted bars, the plain Latin cross underscores simplicity and direct reference to the Gospel accounts of the crucifixion.[25]Greek Cross

The Greek cross consists of four arms of equal length extending from a central intersection at right angles, forming a symmetrical plus-like shape.[26] This distinguishes it from the Latin cross, where the vertical arm is significantly longer than the horizontal one, with the crossbar positioned nearer the top.[25] The design evokes balance and uniformity, predating the Latin cross's dominance in Western Christianity and aligning more closely with early symbolic uses.[27] Early Christians adopted the Greek cross as a symbol, possibly drawing from pre-Christian geometric forms while avoiding direct depiction of the crucifixion's historical T-shaped or stake-like apparatus until later centuries.[28] Its equilateral structure symbolized equality among the four cardinal directions and, by extension, the universal reach of the faith, as evidenced in catacomb art and early liturgical objects from the 3rd to 4th centuries CE.[29] Following Emperor Constantine's vision at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312 CE, which featured a chi-rho overlaid with cross elements, the Greek cross gained prominence in imperial iconography, appearing on coins and standards by the 4th century.[30] In Byzantine architecture, the Greek cross plan became a hallmark, structuring churches around a central dome supported by four equal arms, as seen in the Myrelaion Church (Bodrum Mosque) in Istanbul, constructed around 922 CE under Emperor Romanos I.[31] This layout facilitated spatial harmony and liturgical processions, influencing structures like the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople (dedicated 370 CE, rebuilt 5th century) and later adaptations in Venice's St. Mark's Basilica (consecrated 1085 CE).[32] The form persisted in Eastern Orthodox contexts, symbolizing theological equality of Christ's divine and human natures, and appeared in heraldry, such as the white Greek cross on red in the flag of England, associated with St. George since the 12th century.[33] The Greek cross's symbolism extends to representing the four Evangelists or the elements of creation in equilibrium, though interpretations vary; some sources link it to the Greek letter chi (Χ), an early Christogram, underscoring its pre-Latin roots in Hellenistic Christian communities.[28] Unlike variants with added serifs or bars, the plain Greek cross emphasizes simplicity, making it suitable for mosaics, seals, and vestments across denominations, with documented use in 6th-century Ravenna artifacts like those in San Vitale.[29] Its enduring form underscores a preference for geometric purity over narrative elongation in Eastern rites.[27]Tau Cross

The Tau cross, also known as the crux commissa, is a T-shaped variant of the Christian cross, resembling the Greek letter tau (Τ). This form consists of a vertical post with a horizontal beam affixed at its summit, distinguishing it from the more common Latin cross with its extended lower arm.[17] Its Christian symbolism traces to the Old Testament in Ezekiel 9:4, where God instructs a mark—interpreted as the ancient Hebrew letter tau, resembling a T or X—to be placed on the foreheads of the faithful in Jerusalem to spare them from destruction, prefiguring divine protection akin to the salvific sign of the cross. Early Christians adopted the tau as a symbol of the crucifixion, viewing its shape as evocative of the instrument of Christ's death and associating it with redemption and the Last Judgment, as the final letter of the Hebrew alphabet.[34][35] Roman executioners employed the crux commissa among various cross forms for crucifixion, potentially including the one used for Jesus, as suggested by early patristic texts like the Epistle of Barnabas, which describes the outstretched arms implying a transverse beam at the top. Historical evidence indicates Romans utilized multiple designs, including T-shaped gallows, for affixing victims, though the precise shape of Christ's cross remains debated among scholars due to sparse archaeological and textual corroboration.[23][36] In the medieval period, the Tau gained prominence through St. Francis of Assisi, who adopted it as his personal sigil following the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215, where Pope Innocent III invoked Ezekiel 9 in a sermon urging penance and reform under the tau's sign of conversion. Francis signed his letters with the Tau, incorporated it into Franciscan habits, and viewed it as emblematic of Christ's cross, personal renewal, and a badge of those committed to evangelical poverty and peace. The symbol endures in Franciscan orders as a reminder of incomplete earthly pilgrimage and fidelity to Gospel imperatives.[35][37] Additionally, the Tau cross, termed the Crux Antonii, associates with St. Anthony the Abbot and later served as a protective emblem against ergotism, known as St. Anthony's Fire, in medieval Europe, where Antonine hospitallers bore it in their mission to treat afflicted victims.[38]Other Fundamental Variants

The crux decussata, formed by two bars crossing diagonally to create an X shape, serves as the fourth basic iconographic form of the Christian cross alongside the crux quadrata, immissa, and commissa.[39] This variant differs from the vertical-horizontal orientations of the prior types by employing diagonal axes, providing a distinct geometric expression in early Christian and subsequent symbolic representations.[14] Roman crucifixion practices included the crux decussata among possible structures, with victims affixed in manners similar to other forms, though evidence for its specific use in Christ's execution remains speculative.[23] In Christian tradition, it gained prominence through associations with apostolic martyrdoms, yet as a fundamental shape, it underscores the adaptability of cross iconography beyond strictly perpendicular designs.[19] Its deployment in heraldry and architecture, such as in Scottish national symbols, reflects enduring versatility while rooted in basic cruciform principles.[40]Saints' and Martyrs' Crosses

St. Andrew's Cross

The St. Andrew's Cross, also known as the saltire or crux decussata, consists of two diagonal beams intersecting to form an X shape, distinguishing it from upright Christian cross variants.[41] This form is traditionally associated with the martyrdom of Saint Andrew the Apostle, the brother of Saint Peter and one of Jesus' first disciples, who preached in regions including Scythia and Greece.[42] Historical accounts place his crucifixion in Patras, Achaia (modern-day Greece), circa 60 AD under the Roman proconsul Aegeas, following Andrew's conversion of Aegeas's wife.[43] [42] Early patristic sources, such as Eusebius of Caesarea's Ecclesiastical History (c. 325 AD), confirm Andrew's crucifixion in Patras but provide no details on the cross's configuration, focusing instead on his evangelistic efforts and martyrdom.[43] The specific attribution of an X-shaped cross to Andrew emerges from later hagiographical traditions, likely medieval in development, rather than contemporary eyewitness testimony; these narratives claim Andrew, deeming himself unworthy of dying on a cross like Christ's, requested an oblique form and continued preaching while bound to it for two to three days.[43] [44] Apocryphal texts like the Acts of Andrew (2nd–3rd century) describe his binding to a cross but omit the diagonal shape, suggesting the X iconography evolved as symbolic emphasis on his humility.[43] In Christian symbolism, the St. Andrew's Cross represents apostolic sacrifice, humility, and the spread of the Gospel to the Gentiles, as Andrew is venerated as the patron of fishermen, Scotland, Russia, and Greece.[45] Eastern Orthodox variants sometimes feature additional horizontal bars, reflecting Byzantine influences and Andrew's foundational role in churches like Constantinople, though the plain saltire remains the core form.[46] Its adoption in heraldry and flags, such as Scotland's Saltire (white X on blue, documented from the 12th century), underscores its enduring role beyond liturgy into national identity tied to Andrew's patronage, established by the 8th century.[47] The cross's pre-Christian structural use in ancient architecture, including Minoan examples from circa 2000 BCE, indicates the X motif's antiquity, repurposed in Christianity for saintly commemoration.[48]St. Peter's Cross

The St. Peter's Cross, also known as the Petrine Cross, is an inverted Latin cross symbolizing the martyrdom of the Apostle Peter. According to early Christian tradition, Peter was crucified upside down in Rome during the persecution under Emperor Nero around AD 64-67, at his own request, as he deemed himself unworthy to die in the same posture as Jesus Christ.[49] This account derives primarily from the apocryphal Acts of Peter, a second-century text, though earlier church fathers such as Tertullian and Origen affirm Peter's crucifixion in Rome without specifying the orientation.[50][51] In Christian iconography, the inverted cross represents Peter's humility and apostolic authority, particularly within Catholic tradition where he is regarded as the first pope. It appears in artworks depicting his martyrdom, such as Caravaggio's Crucifixion of Saint Peter (1601), and in heraldry associated with papal or Petrine themes.[49] The symbol underscores themes of self-abnegation and devotion, aligning with Peter's biblical role as the "rock" upon which the church was built (Matthew 16:18).[52] Despite its orthodox Christian origins, the inverted cross has been misinterpreted in contemporary culture as an anti-Christian or satanic emblem, a usage traceable to occult figures like Eugène Vintras in the 19th century and amplified in modern media.[53] This perversion contrasts with its historical veneration; for instance, it features in Vatican symbolism without demonic connotations.[54] Christian sources consistently affirm its legitimacy as a marker of Petrine sacrifice rather than opposition to the faith.[49][55]St. George's Cross and Similar

The St. George's Cross consists of a red upright cross extending to the edges of a white field, symbolizing the martyrdom and patronage of Saint George, an early Christian soldier executed under Emperor Diocletian around 303 AD.[56] This design emerged as a heraldic emblem during the Crusades in the 12th century, when European knights adopted red crosses on white or other backgrounds to denote Christian combatants against Muslim forces, with Saint George invoked as a protector of warriors.[57] King Richard I of England (r. 1189–1199) is credited with popularizing the specific red-on-white variant during the Third Crusade (1189–1192), using it to identify his troops and linking it to chivalric Christian ideals.[58] In Christian symbolism, the cross represents George's triumph over persecution and his role as a model of faith under trial, distinct from the Passion cross of Christ by emphasizing military devotion rather than salvific atonement.[59] By the 14th century, English monarchs such as Edward III (r. 1327–1377) incorporated it into royal banners, establishing Saint George as England's patron saint by 1348, which reinforced its use in ecclesiastical heraldry across the Anglican Communion, including arms of churches in Australia and Canada.[60][61] The Knights Templar and other crusading orders employed similar red crosses, blending George's emblem with broader militant Christian iconography, though the Templars' version often featured a more ornate or charged form.[59] Similar variants include the Genoese cross, a red cross on white adopted by the Republic of Genoa from Byzantine influences around the 11th century and used by its crusading fleets, which parallels the English adoption in denoting maritime Christian defense.[57] Another is the cross of the Order of Saint George, founded in 1326 by King Charles I Robert of Hungary, featuring a red Greek cross on white or argent, evoking George's patronage for royal and military protection in Eastern European Christianity.[62] These forms maintain the straight-armed, equilateral proportions of the Greek cross but adapt colors or charges for regional or institutional contexts, always rooted in George's legacy as a dragon-slaying martyr emblematic of orthodoxy against heresy.[56]Denominational and Regional Variants

Eastern Orthodox Crosses

The Eastern Orthodox cross, a distinctive variant prevalent in traditions such as Russian, Serbian, and other Slavic Orthodox churches, features three horizontal bars: a short upper bar symbolizing the titulus inscribed above Christ's head ("Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews" as per John 19:19), a longer central bar representing the crossbeam to which his arms were nailed, and a slanted lower bar depicting the footrest. The slant of the lower bar conventionally points upward on the right (symbolizing the penitent thief's ascent to paradise) and downward on the left (the impenitent thief's descent to perdition), drawing from Luke 23:39-43.[63][64] This design underscores themes of divine judgment and redemption, with the cross's vertical beam evoking the connection between heaven and earth. Variations include the eight-pointed form, where short diagonal bars at the ends of the horizontal ones represent suppedaneum supports for Christ's feet and a sedile for his body, enhancing the depiction of his physical suffering and victory over death. Inscriptions like "Царь Славы" ("King of Glory") may appear on the top bar in Byzantine-influenced renderings, particularly in Greek traditions. While the three-barred cross with slanted footrest is iconic in Russian Orthodoxy—often appearing in icons, church domes, and personal devotional items—Greek Orthodox usage favors simpler forms or the equilateral Greek cross integrated with ornate Byzantine motifs, reflecting regional liturgical emphases rather than a uniform denominational mandate.[65][66] Historically, elements of the three-barred design trace to Byzantine iconography as early as the 6th century, with the slanted footrest appearing in Eastern Christian art to convey perspective and theological asymmetry in salvation. It gained prominence in Slavic contexts by the 16th century, coinciding with Russia's self-identification as the "Third Rome" after Constantinople's fall in 1453, and was standardized in Russian ecclesiastical metalwork and architecture thereafter. Archaeological claims link proto-forms to 4th-century relics, such as a cross attributed to Emperor Constantine preserved at Mount Athos' Vatopedi Monastery, though scholarly consensus views the full slanted variant as a post-Byzantine elaboration rather than a direct apostolic form.[65][64]Catholic and Papal Variants

The papal cross consists of a vertical post intersected by three horizontal bars of decreasing length from bottom to top, distinguishing it as a symbol of supreme ecclesiastical authority within the Catholic Church. This form appears in heraldry to denote the pope's unique position, where the graduated bars signify hierarchical precedence above archbishops (two bars) and bishops (one bar).[67] The design has been associated with the papacy since at least the medieval period, often mounted on a staff known as the ferula, which popes carried to represent both spiritual and temporal governance during processions and liturgies.[68] Symbolism attributed to the three bars includes representations of the Trinity or the pope's jurisdiction over diverse rites and patriarchates, though primary evidence points to its role as a rank indicator in ecclesiastical insignia rather than doctrinal theology.[69] In practice, the papal cross features prominently in Vatican heraldry, papal seals, and processional standards, such as those used in conclaves and major feasts. For instance, during Pope Paul VI's reign (1963–1978), a modern ferula with a crucifix-topped staff was introduced, designed by artist Lello Scorzelli, blending traditional elements with contemporary form, and subsequently used by Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI.[70] Beyond the papal emblem, Catholic variants emphasize the Latin cross form, often elaborated as crucifixes to highlight Christ's sacrifice, a practice rooted in early Church traditions but formalized in medieval liturgy. Specific to Catholic orders, the Tau cross—shaped like the Greek letter tau (T)—holds significance among Franciscans, adopted by St. Francis of Assisi in the 13th century as a symbol of penance and the cross of Ezekiel's vision (Ezekiel 9:4), frequently incorporated into habits and seals.[71] These variants underscore Catholicism's integration of symbolic crosses into devotional life, heraldry, and institutional identity, prioritizing corporeal representation and hierarchical markers over abstract forms prevalent in other denominations.Protestant and Reformed Symbols

In Protestant traditions, the primary cross variant is the empty Latin cross, devoid of the corpus of Christ, emphasizing the resurrection and the completed work of atonement rather than ongoing suffering. This symbolism underscores Christ's victory over death, distinguishing it from the Catholic crucifix which focuses on the sacrifice.[72] The adoption of the empty cross gained prominence during the Reformation as Protestants rejected ornate religious imagery associated with perceived idolatry, though early reformers like some Anabaptists initially avoided crosses altogether. By the early 20th century, empty crosses became standard on Protestant church steeples and interiors in the United States and elsewhere.[73] Within the Reformed tradition, which includes Presbyterian and Calvinist churches, the use of crosses is more restrained due to a strict interpretation of the Second Commandment prohibiting graven images. The Heidelberg Catechism (1563), a foundational Reformed confessional document, in Lord's Day 35 (Q&A 96-98), forbids the making or retention of images purporting to represent God, including Christ, to prevent idolatry and ensure worship focuses on the preached Word.[74] Consequently, many Reformed church sanctuaries omit crosses entirely, viewing even plain symbols as potentially distracting from scriptural truth or evocative of forbidden representations.[75] Where employed, the cross remains simple and empty, serving as a reminder of redemption without visual depiction of divine persons.[76] Stricter Reformed groups, such as Covenanters, extend this aniconism to reject the cross symbol itself, arguing it constitutes an unauthorized representation of Christ's crucifixion invented in later ecclesiastical tradition.[77] This approach aligns with historical Calvinist iconoclasm, as seen in the removal of religious images during the 16th-century Reformation in places like Geneva and Scotland, prioritizing sola scriptura over visual aids. Despite variations, the Reformed emphasis remains on doctrinal purity, with any cross use subordinated to theological precision rather than liturgical centrality.[78]Regional and Cultural Adaptations

In regions with ancient Christian communities, the cross has been stylized to reflect local artistic traditions and cultural contexts while preserving its core symbolism of Christ's sacrifice. Coptic Christians in Egypt, whose church traces its origins to the evangelization by St. Mark around 42 AD, employ a distinctive cross variant featuring equal arms often encircled or adorned with intricate geometric patterns derived from Pharaonic motifs adapted to Christian iconography. This form serves as a tattoo symbol among Copts, historically marking believers during periods of persecution under Roman and later Islamic rule to affirm identity and faith.[79][80] Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity, established by the 4th century following the conversion of King Ezana in 330 AD, features highly elaborate cross variants known as Abyssinian crosses, characterized by latticework, curved arms, and motifs like the gammadion swastika repurposed from pre-Christian Ethiopian symbolism to denote eternity and protection. These crosses appear in three primary forms: small pendants for personal devotion, hand-held processional crosses for liturgical use, and larger altar or rooftop versions often topped with ostrich eggs symbolizing resurrection and vigilance. Crafted by hereditary artisan families using alloys like brass or silver, they number in the thousands across Ethiopian churches, embodying a fusion of Aksumite geometric styles with biblical typology.[81][82] In Armenia, the world's first nation to adopt Christianity as state religion in 301 AD under King Tiridates III, the khachkar— a freestanding stone stele bearing a central cross—represents a monumental adaptation erected as memorials, vows, or markers of holy sites from the 9th century onward, with over 50,000 surviving examples documented by the early 20th century. Typically 1-1.5 meters tall, khachkars feature a potent cross (with flared ends) resting on a solar wheel or eternity symbol, surrounded by vegetal, rosette, or interlace ornaments influenced by local stonemasonry traditions; UNESCO recognized this art form in 2010 for its unique synthesis of Christian theology and Armenian cosmology, where the cross evokes the Tree of Life.[83] Latin American adaptations emerged during 16th-century Spanish evangelization, as seen in open-air atrial crosses in Mexico, such as the mid-1500s example at Acolman convent, which blend Latin cross proportions with indigenous motifs like floral reliefs and solar discs to facilitate conversion among Mesoamerican populations familiar with similar pre-Columbian symbols of sacrifice and renewal. These courtyard crosses, numbering dozens in central Mexico by 1600, served didactic purposes in newly built mission complexes, adapting European forms to local cosmology without altering the cross's salvific meaning.[84]Symbolic and Non-Denominational Crosses

Jerusalem Cross

The Jerusalem cross consists of a large central cross potent, characterized by arms that terminate in T-shapes, overlaid with four smaller Greek crosses—one in each quadrant formed by the central cross's arms—creating a five-fold design.[20] This heraldic form emerged in the context of the First Crusade and served as the coat of arms for the Kingdom of Jerusalem after the city's capture on July 15, 1099.[85] Tradition attributes its adoption to Godfrey de Bouillon, the first Latin ruler of Jerusalem, who declined the title of king but used the symbol to represent Christian authority in the Holy Land.[86] [87] Symbolically, the central cross evokes Christ's crucifixion, while the four smaller crosses signify the proclamation of the Gospel from Jerusalem to the four corners of the earth, aligning with the biblical commission in Acts 1:8.[21] Alternative interpretations link the five crosses to the wounds of Christ during the Passion or the four evangelists surrounding the Savior.[20] The design's potency—referring to the cranked ends—may derive from Byzantine influences or practical heraldic needs for visibility on seals and banners during the Crusades.[88] It appeared on coins, flags, and seals of the kingdom until its fall in 1291, embodying the Crusader states' aspirations for a Christian dominion.[85] In subsequent centuries, the Jerusalem cross became the emblem of the Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem, founded in the 12th century to protect pilgrims and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.[89] The order, elevated to a pontifical institution by Pope Pius X in 1906, continues to employ the symbol in gold on a red field for its insignia, signifying fidelity to the faith and support for Christians in the Holy Land.[90] Beyond knighthood orders, the cross features in ecclesiastical heraldry and devotional items, maintaining its association with pilgrimage and evangelization without evolving into denominational exclusivity.[91]Celtic Cross

The Celtic cross consists of a Latin cross with a circular ring, or nimbus, intersecting and often extending beyond the arms at their junction, typically adorned with intricate interlaced knotwork derived from Insular artistic traditions.[92] This design distinguishes it from simpler cross variants and reflects the fusion of Christian iconography with Celtic metalworking and manuscript illumination techniques prevalent in early medieval monasteries.[93] The earliest documented examples appear in Ireland and parts of Britain from the late 7th century onward, with stone-carved high crosses emerging prominently between the 8th and 12th centuries at monastic centers such as Monasterboice and Clonmacnoise.[94] These freestanding monuments, sometimes exceeding 3 meters in height, served as outdoor sermons in stone, featuring figural panels depicting scenes from the Old and New Testaments to instruct illiterate congregations on Christian doctrine.[95] Archaeological evidence, including dated inscriptions and associated monastic remains, confirms their Christian context, with no verified pre-Christian precursors matching the full ringed form despite speculative links to ancient wheel or sun symbols.[96] Symbolically, the vertical beam and crossbar evoke the crucifixion of Jesus Christ, while the encircling ring is interpreted in Christian theology as representing eternity, the unbroken cycle of divine love, or a radiant halo signifying Christ's divinity and resurrection light.[97] Some historical analyses propose the ring adapted pagan solar motifs to assert Christianity's supremacy, overlaying the cross upon the sun to symbolize Christ's triumph over celestial deities in Celtic cosmology.[92] This adaptation aligns with missionary strategies in Celtic regions, where incoming monks like those from Iona integrated local aesthetics without endorsing prior pagan rituals, as evidenced by the crosses' exclusive biblical carvings.[98] In modern contexts, the Celtic cross endures as a emblem of Celtic heritage and Christianity, appearing on gravestones, jewelry, and national symbols in Ireland and Scotland, though its appropriation by non-religious or fringe groups underscores the need to distinguish its original ecclesiastical purpose.[99] Over 200 surviving high crosses attest to its role in preserving Insular Christianity amid Viking raids and Norman influences, with conservation efforts by institutions like the National Museum of Ireland dating restorations to the 19th century Celtic Revival.[96]Anchored and Chi-Rho Derived Forms

The anchored cross consists of a Latin cross with its lower extremity shaped like the fluke of an anchor, symbolizing steadfast hope in Christ as described in Hebrews 6:19, which portrays faith as "an anchor of the soul, both sure and steadfast."[100] This biblical metaphor, emphasizing stability amid life's tempests, led early Christians to adopt the anchor as a symbol of salvation and endurance, particularly during periods of persecution when overt cross imagery was avoided.[101] The form's etymology traces to the Greek ankyra (ἀγκύρα), meaning "hook" or "anchor," evolving into Latin ancora, and by the 2nd century AD, anchors appeared in Christian catacomb art as disguised crosses.[102] By combining the anchor with the cross, early believers explicitly linked Christ's passion to this emblem of security, with examples found in 3rd-century Roman sarcophagi and later medieval heraldry associated with maritime saints like St. Nicholas.[103] Its use persists in ecclesiastical insignia, such as in the seals of missionary orders, underscoring communal anchoring in faith.[104] Chi-Rho derived forms stem from the Christogram formed by superimposing the Greek letters chi (Χ) and rho (Ρ)—the first two of Christos (ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ)—creating a cruciform monogram evoking the cross despite not being a literal cross shape.[105] Originating in the late 2nd century AD in Christian manuscripts and inscriptions, it gained prominence under Emperor Constantine I, who reportedly envisioned it overlaid with the words In hoc signo vinces ("In this sign, you will conquer") before his victory at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge on October 28, 312 AD, leading to its adoption on military standards like the labarum.[106] Derived variants integrate the Chi-Rho into cross structures, such as the labarum's vexillum featuring the symbol atop a crossbar, or Byzantine icons where it crowns a cross potent, symbolizing Christ's eternal sovereignty with added alpha (Α) and omega (Ω) loops.[107] These adaptations proliferated in 4th-century Roman coinage and Eastern Orthodox art, evolving into monograms like the staurogram (a tau cross with rho overlay), an even earlier 2nd-century cruciform Christogram found in Egyptian papyri, predating widespread cross veneration.[102] Such forms underscore the Chi-Rho's role in bridging pre-Constantinian secrecy with public imperial Christianity, prioritizing christological abbreviation over pagan solar interpretations sometimes alleged but unsubstantiated in primary patristic sources.[105]Crosses in Orders and Institutions

Military and Chivalric Orders