Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Glycerol

View on Wikipedia | |||

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Propan-1,2,3-triol[1] | |||

Other names

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| DrugBank | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.263 | ||

| E number | E422 (thickeners, ...) | ||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C3H8O3 | |||

| Molar mass | 92.094 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Colorless hygroscopic liquid | ||

| Odor | Odorless | ||

| Density | 1.261 g/cm3 | ||

| Melting point | 17.8 °C (64.0 °F; 290.9 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 290 °C (554 °F; 563 K)[5] | ||

| miscible[2] | |||

| log P | −2.32[3] | ||

| Vapor pressure | 0.003 mmHg (0.40 Pa) at 50 °C[2] | ||

| −57.06×10−6 cm3/mol | |||

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.4746 | ||

| Viscosity | 1.412 Pa·s (20 °C)[4] | ||

| Pharmacology | |||

| A06AG04 (WHO) A06AX01 (WHO), QA16QA03 (WHO) | |||

| Hazards | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | 160 °C (320 °F; 433 K) (closed cup) 176 °C (349 °F; 449 K) (open cup) | ||

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |||

PEL (Permissible)

|

TWA 15 mg/m3 (total) TWA 5 mg/m3 (resp)[2] | ||

REL (Recommended)

|

None established[2] | ||

IDLH (Immediate danger)

|

N.D.[2] | ||

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | JT Baker ver. 2008 archive | ||

| Supplementary data page | |||

| Glycerol (data page) | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

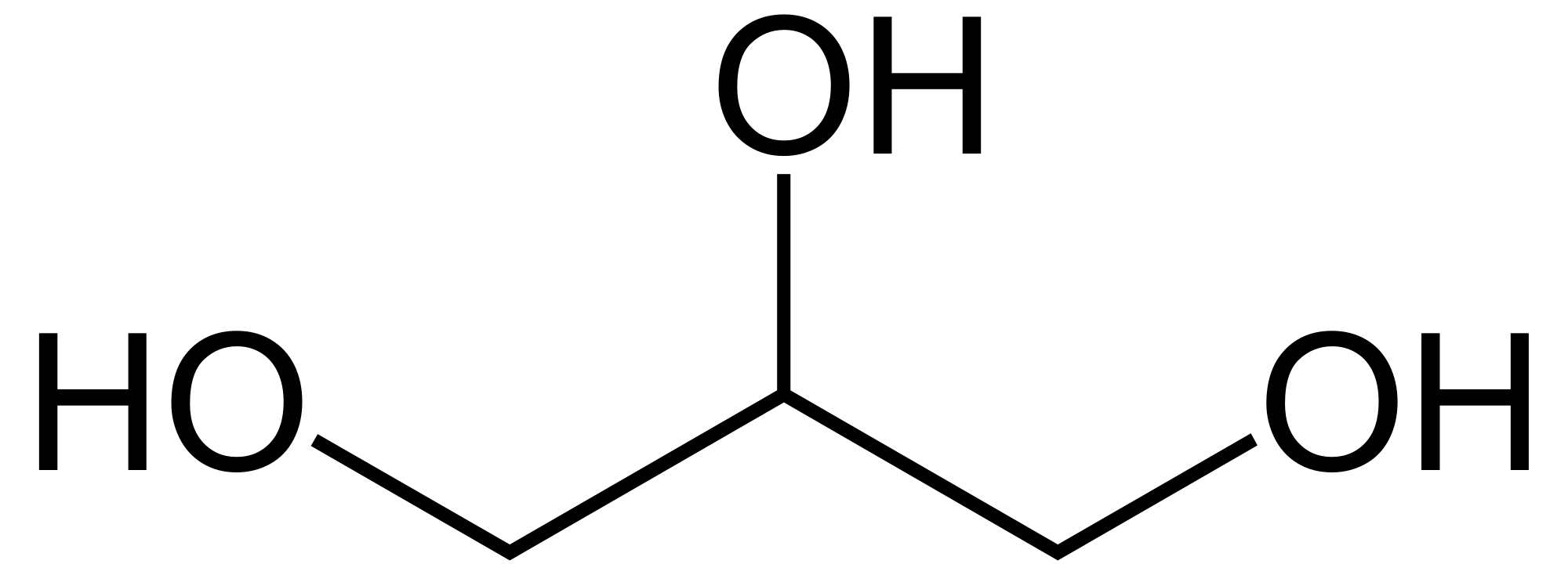

Glycerol (/ˈɡlɪsərɒl/)[6] is a simple triol compound. It is a colorless, odorless, sweet-tasting, viscous liquid. The glycerol backbone is found in lipids known as glycerides. It is also widely used as a sweetener in the food industry and as a humectant in pharmaceutical formulations. Because of its three hydroxyl groups, glycerol is miscible with water and is hygroscopic in nature.[7]

Modern use of the word glycerine (alternatively spelled glycerin) refers to commercial preparations of less than 100% purity, typically 95% glycerol.[8]

Structure

[edit]Although achiral, glycerol is prochiral with respect to reactions of one of the two primary alcohols. Thus, in substituted derivatives, the stereospecific numbering labels the molecule with a sn- prefix before the stem name of the molecule.[9][10][11]

Production

[edit]Natural sources

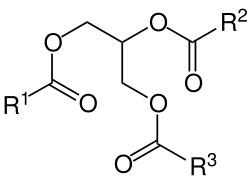

[edit]Glycerol is generally obtained from plant and animal sources where it occurs in triglycerides, esters of glycerol with long-chain carboxylic acids. The hydrolysis, saponification, or transesterification of these triglycerides produces glycerol as well as the fatty acid derivative:

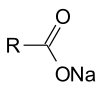

Triglycerides can be saponified with sodium hydroxide to give glycerol and fatty sodium salt or soap.

Typical plant sources include soybeans or palm. Animal-derived tallow is another source. From 2000 to 2004, approximately 950,000 tons per year were produced in the United States and Europe; 350,000 tons of glycerol were produced in the U.S. alone.[12] Since around 2010, there is a large surplus of glycerol as a byproduct of biofuel, enforced for example by EU directive 2003/30/EC that required 5.75% of petroleum fuels to be replaced with biofuel sources across all member states.[7] Crude glycerol produced from triglycerides is of variable quality, with a selling price as low as US$0.02–0.05 per kilogram in 2011.[13] It can be purified in a rather expensive process by treatment with activated carbon to remove organic impurities, alkali to remove unreacted glycerol esters, and ion exchange to remove salts. High purity glycerol (greater than 99.5%) is obtained by multi-step distillation; a vacuum chamber is necessary due to its high boiling point (290 °C).[7]

Consequently, glycerol recycling is more of a challenge than its production, for instance by conversion to glycerol carbonate[14] or to synthetic precursors, such as acrolein and epichlorohydrin.[15]

Synthetic glycerol

[edit]Although more expensive than production from plant or animal triglycerides, glycerol can be synthesized by various routes. During World War II, synthetic glycerol processes became a national defense priority because it is a precursor to nitroglycerine. Epichlorohydrin is the most important precursor. Chlorination of propylene gives allyl chloride, which is oxidized with hypochlorite to dichlorohydrin, which reacts with a strong base to give epichlorohydrin. Epichlorohydrin can be hydrolyzed to glycerol. Chlorine-free processes from propylene include the synthesis of glycerol from acrolein and propylene oxide.[7]

Applications

[edit]Food industry

[edit]In food and beverages, glycerol serves as a humectant, solvent, and sweetener, and may help preserve foods. It is also used as filler in commercially prepared low-fat foods (e.g., cookies), and as a thickening agent in liqueurs. Glycerol and water are used to preserve certain types of plant leaves.[16]

It is recommended as an additive when polyol sweeteners such as erythritol and xylitol are used, as its heating effect in the mouth will counteract these sweeteners' cooling effect.[17]

Medical

[edit]

Glycerol is used in medical, pharmaceutical and personal care preparations, often as a means of improving smoothness, providing lubrication, and as a humectant.

Ichthyosis and xerosis have been relieved by the topical use of glycerin.[18][19] It is found in allergen immunotherapies, cough syrups, elixirs and expectorants, toothpaste, mouthwashes, skin care products, shaving cream, hair care products, soaps, and water-based personal lubricants. In solid dosage forms like tablets, glycerol is used as a tablet holding agent. For human consumption, glycerol is classified by the FDA among the sugar alcohols as a caloric macronutrient. Glycerol is also used in blood banking to preserve red blood cells prior to freezing.[20]

Taken rectally, glycerol functions as a laxative by irritating the anal mucosa and inducing a hyperosmotic effect,[21] expanding the colon by drawing water into it to induce peristalsis resulting in evacuation.[22] It may be administered undiluted either as a suppository or as a small-volume (2–10 ml) enema. Alternatively, it may be administered in a dilute solution, such as 5%, as a high-volume enema.[23]

Taken orally (often mixed with fruit juice to reduce its sweet taste), glycerol can cause a rapid, temporary decrease in the internal pressure of the eye. This can be useful for the initial emergency treatment of severely elevated eye pressure.[24]

In 2017, researchers showed that the probiotic Limosilactobacillus reuteri bacteria can be supplemented with glycerol to enhance its production of antimicrobial substances in the human gut. This was confirmed to be as effective as the antibiotic vancomycin at inhibiting Clostridioides difficile infection without having a significant effect on the overall microbial composition of the gut.[25]

Glycerol solutions have been used for the preservation and storage of tissue grafts at ambient conditions as an alternative to frozen storage.[26]

Glycerol has also been incorporated as a component of bio-ink formulations in the field of bioprinting.[27] The glycerol content acts to add viscosity to the bio-ink without adding large protein, saccharide, or glycoprotein molecules.

It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[28]

Botanical extracts

[edit]When utilized in tincture method extractions, specifically as a 10% solution, glycerol prevents tannins from precipitating in ethanol extracts of plants (tinctures). It is also used as an "alcohol-free" alternative to ethanol as a solvent in preparing herbal extractions. It is less extractive when utilized in a standard tincture methodology. Alcohol-based tinctures can also have the alcohol removed and replaced with glycerol for its preserving properties. Such products are not "alcohol-free" in a scientific or FDA regulatory sense, as glycerol contains three hydroxyl groups. Fluid extract manufacturers often extract herbs in hot water before adding glycerol to make glycerites.[29][30]

When used as a primary "true" alcohol-free botanical extraction solvent in non-tincture based methodologies, glycerol has been shown to possess a high degree of extractive versatility for botanicals including removal of numerous constituents and complex compounds, with an extractive power that can rival that of alcohol and water–alcohol solutions.[31] That glycerol possesses such high extractive power assumes it is utilized with dynamic (critical) methodologies as opposed to standard passive "tincturing" methodologies that are better suited to alcohol. Glycerol does not denature or render a botanical's constituents inert as alcohols (ethanol, methanol, and so on) do. Glycerol is a stable preserving agent for botanical extracts that, when utilized in proper concentrations in an extraction solvent base, does not allow inverting or reduction-oxidation of a finished extract's constituents, even over several years.[citation needed] Both glycerol and ethanol are viable preserving agents. Glycerol is bacteriostatic in its action, and ethanol is bactericidal in its action.[32][33][34]

Electronic cigarette liquid

[edit]

Glycerin, along with propylene glycol, is a common component of e-liquid, a solution used with electronic vaporizers (electronic cigarettes). This glycerol is heated with an atomizer (a heating coil often made of Kanthal wire), producing the aerosol that delivers nicotine to the user.[35]

Antifreeze

[edit]Like ethylene glycol and propylene glycol, glycerol is a non-ionic kosmotrope that forms strong hydrogen bonds with water molecules, competing with water-water hydrogen bonds. This interaction disrupts the formation of ice. The minimum freezing point temperature is about −38 °C (−36 °F) corresponding to 70% glycerol in water.

Glycerol was historically used as an anti-freeze for automotive applications before being replaced by ethylene glycol, which has a lower freezing point. While the minimum freezing point of a glycerol-water mixture is higher than an ethylene glycol-water mixture, glycerol is not toxic and is being re-examined for use in automotive applications.[36][37]

In the laboratory, glycerol is a common component of solvents for enzymatic reagents stored at temperatures below 0 °C (32 °F) due to the depression of the freezing temperature. It is also used as a cryoprotectant where the glycerol is dissolved in water to reduce damage by ice crystals to laboratory organisms that are stored in frozen solutions, such as fungi, bacteria, nematodes, and mammalian embryos. Some organisms like the moor frog produce glycerol to survive freezing temperatures during hibernation.[38]

Chemical intermediate

[edit]Glycerol is used to produce a variety of useful derivatives.

Nitration gives nitroglycerin, an essential ingredient of various explosives such as dynamite, gelignite, and propellants like cordite. Nitroglycerin under the name glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) is commonly used to relieve angina pectoris, taken in the form of sub-lingual tablets, patches, or as an aerosol spray.

Trifunctional polyether polyols are produced from glycerol and propylene oxide.

Oxidation of glycerol affords mesoxalic acid.[39] Dehydrating glycerol affords hydroxyacetone.

Chlorination of glycerol gives the 1-chloropropane-2,3-diol:

- HOCH(CH2OH)2 + HCl → HOCH(CH2Cl)(CH2OH) + H2O

The same compound can be produced by hydrolysis of epichlorohydrin.[40]

Epoxidation by reaction with epichlorohydrin and a Lewis acid yields Glycerol triglycidyl ether.[41][42]

Vibration damping

[edit]Glycerol is used as fill for pressure gauges to damp vibration. External vibrations, from compressors, engines, pumps, etc., produce harmonic vibrations within Bourdon gauges that can cause the needle to move excessively, giving inaccurate readings. The excessive swinging of the needle can also damage internal gears or other components, causing premature wear. Glycerol, when poured into a gauge to replace the air space, reduces the harmonic vibrations that are transmitted to the needle, increasing the lifetime and reliability of the gauge.[43]

Niche uses

[edit]Entertainment industry

[edit]Glycerol is used by set decorators when filming scenes involving water to prevent an area meant to look wet from drying out too quickly.[44]

Glycerine is also used in the generation of theatrical smoke and fog as a component of the fluid used in fog machines as a replacement for glycol, which has been shown to be an irritant if exposure is prolonged.

Ultrasonic couplant

[edit]Glycerol can be sometimes used as replacement for water in ultrasonic testing, as it has favourably higher acoustic impedance (2.42 MRayl versus 1.483 MRayl for water) while being relatively safe, non-toxic, non-corrosive and relatively low cost.[45]

Internal combustion fuel

[edit]Glycerol is also used to power diesel generators supplying electricity for the FIA Formula E series of electric race cars.[46]

Research on additional uses

[edit]Research continues into potential value-added products of glycerol obtained from biodiesel production.[47] Examples (aside from combustion of waste glycerol):

- Hydrogen gas production.[48]

- Glycerine acetate is a potential fuel additive.[49]

- Additive for starch thermoplastic.[50][51]

- Conversion to various other chemicals:

- Propylene glycol[52]

- Acrolein[53][54][55]

- Ethanol[56][57]

- Epichlorohydrin,[58] a raw material for epoxy resins

Metabolism

[edit]Glycerol is a precursor for synthesis of triacylglycerols and of phospholipids in the liver and adipose tissue. When the body uses stored fat as a source of energy, glycerol and fatty acids are released into the bloodstream.

Glycerol is mainly metabolized in the liver. Glycerol injections can be used as a simple test for liver damage, as its rate of absorption by the liver is considered an accurate measure of liver health. Glycerol metabolism is reduced in both cirrhosis and fatty liver disease.[59][60]

Blood glycerol levels are highly elevated during diabetes, and is believed to be the cause of reduced fertility in patients who suffer from diabetes and metabolic syndrome. Blood glycerol levels in diabetic patients average three times higher than healthy controls. Direct glycerol treatment of testes has been found to cause significant long-term reduction in sperm count. Further testing on this subject was abandoned due to the unexpected results, as this was not the goal of the experiment.[61]

Circulating glycerol does not glycate proteins as do glucose or fructose, and does not lead to the formation of advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs). In some organisms, the glycerol component can enter the glycolysis pathway directly and, thus, provide energy for cellular metabolism (or, potentially, be converted to glucose through gluconeogenesis).

Before glycerol can enter the pathway of glycolysis or gluconeogenesis (depending on physiological conditions), it must be converted to their intermediate glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate in the following steps:

The enzyme glycerol kinase is present mainly in the liver and kidneys, but also in other body tissues, including muscle and brain.[62][63][64] In adipose tissue, glycerol 3-phosphate is obtained from dihydroxyacetone phosphate with the enzyme glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Toxicity and safety

[edit]Glycerol has very low toxicity when ingested; its LD50 oral dose for rats is 12600 mg/kg and 8700 mg/kg for mice. It does not appear to cause toxicity when inhaled, although changes in cell maturity occurred in small sections of lung in animals under the highest dose measured. A sub-chronic 90-day nose-only inhalation study in Sprague Dawley rats exposed to 0.03, 0.16 and 0.66 mg of glycerin per liter of air for 6-hour continuous sessions revealed no treatment-related toxicity other than minimal metaplasia of the epithelium lining at the base of the epiglottis in rats exposed to 0.66 mg/L glycerin.[65][66]

Glycerol intoxication

[edit]Excessive consumption by children can lead to glycerol intoxication.[67] Symptoms of intoxication include hypoglycemia, nausea and a loss of consciousness. While intoxication as a result of excessive glycerol consumption is rare and its symptoms generally mild, occasional reports of hospitalization have occurred.[68] In the United Kingdom in August 2023, manufacturers of syrup used in slush ice drinks were advised to reduce the amount of glycerol in their formulations by the Food Standards Agency to reduce the risk of intoxication.[69] A 2025 study reported that between 2018 and 2024, at least 21 children aged 2–7 in the UK and Ireland received emergency treatment for symptoms of glycerol intoxication following the consumption of slush ice drinks.[70][71]

Food Standards Scotland advises that slush ice drinks containing glycerol should not be given to children under the age of 4, owing to the risk of intoxication. It also recommends that businesses do not use free refill offers for the drinks in venues where children under the age of 10 are likely to consume them, and that products should be appropriately labelled to inform consumers of the presence of glycerol.[72]

Historical cases of contamination with diethylene glycol

[edit]On 4 May 2007, the FDA advised all U.S. makers of medicines to test all batches of glycerol for diethylene glycol contamination.[73] This followed an occurrence of hundreds of fatal poisonings in Panama resulting from a falsified import customs declaration by Panamanian import/export firm Aduanas Javier de Gracia Express, S. A. The cheaper diethylene glycol was relabeled as the more expensive glycerol.[74][75] Between 1990 and 1998, incidents of DEG poisoning reportedly occurred in Argentina, Bangladesh, India, and Nigeria, and resulted in hundreds of deaths. In 1937, more than one hundred people died in the United States after ingesting DEG-contaminated elixir sulfanilamide, a drug used to treat infections.[76]

Etymology

[edit]The origin of the gly- and glu- prefixes for glycols and sugars is from Ancient Greek γλυκύς glukus which means sweet.[77] Name glycérine was coined ca. 1811 by Michel Eugène Chevreul to denote what was previously called "sweet principle of fat" by its discoverer Carl Wilhelm Scheele. It was borrowed into English ca. 1838 and in the 20th c. displaced by 1872 term glycerol featuring an alcohols' suffix -ol.

Properties

[edit]Table of thermal and physical properties of saturated liquid glycerin:[78][79]

Temperature (°C) Density (kg/m3) Specific heat (kJ/kg·K) Kinematic viscosity (m2/s) Conductivity (W/m·K) Thermal diffusivity (m2/s) Prandtl number Bulk modulus (K−1) 0 1276.03 2.261 8.31×10−3 0.282 9.83×10−8 84700 4.7×10−4 10 1270.11 2.319 3.00×10−3 0.284 9.65×10−8 31000 4.7×10−4 20 1264.02 2.386 1.18×10−3 0.286 9.47×10−8 12500 4.8×10−4 30 1258.09 2.445 5.00×10−4 0.286 9.29×10−8 5380 4.8×10−4 40 1252.01 2.512 2.20×10−4 0.286 9.14×10−8 2450 4.9×10−4 50 1244.96 2.583 1.50×10−4 0.287 8.93×10−8 1630 5.0×10−4

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (2014). Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry: IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013. The Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 690. doi:10.1039/9781849733069. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

- ^ a b c d e NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0302". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ "glycerin_msds". Archived from the original on 8 March 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ^ Segur, J. B.; Oberstar, H. E. (1951). "Viscosity of Glycerol and Its Aqueous Solutions". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry. 43 (9): 2117–2120. doi:10.1021/ie50501a040.

- ^ Lide, D. R., ed. (1994). CRC Handbook of Data on Organic Compounds (3rd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. 4386.

- ^ "glycerol – Definition of glycerol in English by Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries – English. Archived from the original on 21 June 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d Christoph, Ralf; Schmidt, Bernd; Steinberner, Udo; Dilla, Wolfgang; Karinen, Reetta (2006). "Glycerol". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a12_477.pub2. ISBN 3-527-30673-0.

- ^ "Is There any Difference Between Glycerin and Glycerol?". Oxford Dictionaries – English. 9 April 2024. Retrieved 20 October 2024.

- ^ Hirschmann, H. (1 October 1960). "The Nature of Substrate Asymmetry in Stereoselective Reactions". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 235 (10): 2762–2767. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)64537-5. PMID 13714619.

- ^ "IUPAC-IUB Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature (CBN)". European Journal of Biochemistry. 2 (2): 127–131. 1 September 1967. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1967.tb00116.x. PMID 6078528.

- ^ Alfieri A, Imperlini E, Nigro E, Vitucci D, Orrù S, Daniele A, Buono P, Mancini A (2017). "Effects of Plant Oil Interesterified Triacylglycerols on Lipemia and Human Health". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 19 (1) E104. MDPI (published 30 December 2017). doi:10.3390/ijms19010104. eISSN 1422-0067. PMC 5796054. PMID 29301208. S2CID 5123735.

- ^ Nilles, Dave (2005). "A Glycerin Factor". Biodiesel Magazine. Archived from the original on 8 November 2007. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ San Kong, Pei; Kheireddine Aroua, Mohamed; Ashri Wan Daud, Wan Mohd (2016). "Conversion of crude and pure glycerol into derivatives: A feasibility evaluation". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 63: 533–555. Bibcode:2016RSERv..63..533K. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2016.05.054.

- ^ Das, Arpita; Kodgire, Pravin; Li, Hu; Basumatary, Sanjay; Baskar, Gurunathan; Rokhum, Samuel Lalthazuala (2023). "Recent Advances in Conversion of Glycerol: A Byproduct of Biodiesel Production to Glycerol Carbonate". Journal of Chemistry. 2023 (1) 8730221. doi:10.1155/2023/8730221. ISSN 2090-9071.

- ^ Yu, Bin (2014). "Glycerol". Synlett. 25 (4): 601–602. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1340636.

- ^ Gouin, Francis R. (1994). "Preserving flowers and leaves" (PDF). Maryland Cooperative Extension Fact Sheet. 556: 1–6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 January 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ^ Nikolov, Ivan (20 April 2014). "Functional Food Design Rules". Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ Ichthyosis: New Insights for the Healthcare Professional. ScholarlyEditions. 22 July 2013. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-4816-5966-6.

- ^ Mark G. Lebwohl; Warren R. Heymann; John Berth-Jones; Ian Coulson (19 September 2017). Treatment of Skin Disease E-Book: Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-0-7020-6913-0.

- ^ Lagerberg, Johan W. (2015). "Cryopreservation of Red Blood Cells". Cryopreservation and Freeze-Drying Protocols. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 1257. Humana Press. pp. 353–367. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-2193-5_17. ISBN 978-1-4939-2192-8. PMID 25428017.

- ^ "Glycerin Enema". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ^ "glycerin enema". NCI Drug Dictionary. National Cancer Institute. 2 February 2011. Archived from the original on 2 May 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ^ E. Bertani; A. Chiappa; R. Biffi; P. P. Bianchi; D. Radice; V. Branchi; S. Spampatti; I. Vetrano; B. Andreoni (2011). "Comparison of oral polyethylene glycol plus a large volume glycerine enema with a large volume glycerine enema alone in patients undergoing colorectal surgery for malignancy: a randomized clinical trial". Colorectal Disease. 13 (10): e327 – e334. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02689.x. PMID 21689356. S2CID 32872781.

- ^ "Glycerin (Oral Route)". Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Archived from the original on 27 November 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ^ Spinler, Jennifer K.; Auchtung, Jennifer; Brown, Aaron; Boonma, Prapaporn; Oezguen, Numan; Ross, Caná L.; Luna, Ruth Ann; Runge, Jessica; Versalovic, James; Peniche, Alex; Dann, Sara M. (October 2017). "Next-Generation Probiotics Targeting Clostridium difficile through Precursor-Directed Antimicrobial Biosynthesis". Infection and Immunity. 85 (10): e00303–17. doi:10.1128/IAI.00303-17. ISSN 1098-5522. PMC 5607411. PMID 28760934.

- ^ Samsell, Brian; Softic, Davorka; Qin, Xiaofei; McLean, Julie; Sohoni, Payal; Gonzales, Katrina; Moore, Mark A. (13 February 2019). "Preservation of allograft bone using a glycerol solution: a compilation of original preclinical research". Biomaterials Research. 23 (1). Science Partner Journals: 5. doi:10.1186/s40824-019-0154-1. eISSN 2055-7124. PMC 6373109. PMID 30805200. S2CID 67860055 – via Atypon Journals.

- ^ Atala, Anthony; Yoo, James J.; Carlos Kengla; Ko, In Kap; Lee, Sang Jin; Kang, Hyun-Wook (March 2016). "A 3D bioprinting system to produce human-scale tissue constructs with structural integrity". Nature Biotechnology. 34 (3): 312–319. doi:10.1038/nbt.3413. ISSN 1546-1696. PMID 26878319. S2CID 9073831.

- ^ World Health Organization (2025). The selection and use of essential medicines, 2025: WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, 24th list. Geneva: World Health Organization. doi:10.2471/B09474. hdl:10665/382243.

- ^ Long, Walter S. (14 January 1916). "The Composition of Commercial Fruit Extracts". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 28: 157–161. doi:10.2307/3624347. JSTOR 3624347.

- ^ Does alcohol belong in herbal tinctures? Archived 12 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine newhope.com

- ^ "Glycerine: An Overview" (PDF). aciscience.org. The Soap and Detergent Association. 1990. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 June 2019.

- ^ Lawrie, James W. (1928) Glycerol and the glycols – production, properties and analysis. The Chemical Catalog Company, Inc., New York, NY.

- ^ Leffingwell, Georgia and Lesser, Miton (1945) Glycerin – its industrial and commercial applications. Chemical Publishing Co., Brooklyn, NY.[page needed]

- ^ The manufacture of glycerol – Vol. III (1956). The Technical Press, LTD., London.[page needed]

- ^ Dasgupta, Amitava; Klein, Kimberly (2014). "4.2.5 Are Electronic Cigarettes Safe?". Antioxidants in Food, Vitamins and Supplements: Prevention and Treatment of Disease. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-405917-7. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ^ Hudgens, R. Douglas; Hercamp, Richard D.; Francis, Jaime; Nyman, Dan A.; Bartoli, Yolanda (2007). "An Evaluation of Glycerin (Glycerol) as a Heavy Duty Engine Antifreeze/Coolant Base". SAE Technical Paper Series. Vol. 1. doi:10.4271/2007-01-4000.

- ^ Proposed ASTM Engine Coolant Standards Focus on Glycerin Archived 14 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Astmnewsroom.org. Retrieved on 15 August 2012

- ^ Shekhovtsov, Sergei V.; Bulakhova, Nina A.; Tsentalovich, Yuri P.; Zelentsova, Ekaterina A.; Meshcheryakova, Ekaterina N.; Poluboyarova, Tatiana V.; Berman, Daniil I. (January 2022). "Metabolomic Analysis Reveals That the Moor Frog Rana arvalis Uses Both Glucose and Glycerol as Cryoprotectants". Animals. 12 (10). MDPI (published 17 May 2022): 1286. doi:10.3390/ani12101286. ISSN 2076-2615. PMC 9137551. PMID 35625132. S2CID 248879904.

- ^ Ciriminna, Rosaria; Pagliaro, Mario (2003). "One-Pot Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Oxidation of Glycerol to Ketomalonic Acid Mediated by TEMPO". Advanced Synthesis & Catalysis. 345 (3): 383–388. doi:10.1002/adsc.200390043.

- ^ Sutter, Marc; Silva, Eric Da; Duguet, Nicolas; Raoul, Yann; Métay, Estelle; Lemaire, Marc (2015). "Glycerol Ether Synthesis: A Bench Test for Green Chemistry Concepts and Technologies" (PDF). Chemical Reviews. 115 (16): 8609–8651. doi:10.1021/cr5004002. PMID 26196761.

- ^ Crivello, James V. (2006). "Design and synthesis of multifunctional glycidyl ethers that undergo frontal polymerization". Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 44 (21): 6435–6448. Bibcode:2006JPoSA..44.6435C. doi:10.1002/pola.21761. ISSN 0887-624X.

- ^ US 5162547, Roth, Martin; Wolleb, Heinz & Truffer, Marc-Andre, "Process for the preparation of glycidyl ethers", published 10 November 1992, assigned to Ciba-Geigy Corp.

- ^ Pneumatic Systems: Principles and Maintenance by S. R. Majumdar. McGraw-Hill, 2006, p. 74 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Hawthorne, Amy (4 May 2015). "Chemicals in Film: 20th Century Fox orders Products". ReAgent. Archived from the original on 29 September 2015.

- ^ Acoustic Properties for Liquids Archived 27 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine nde-ed.org

- ^ Formula E uses pollution-free glycerine to charge cars. fiaformulae.com. 13 September 2014

- ^ Johnson, Duane T.; Taconi, Katherine A. (2007). "The glycerin glut: Options for the value-added conversion of crude glycerol resulting from biodiesel production". Environmental Progress. 26 (4): 338–348. Bibcode:2007EnvPr..26..338J. doi:10.1002/ep.10225.

- ^ Marshall, A. T.; Haverkamp, R. G. (2008). "Production of hydrogen by the electrochemical reforming of glycerol-water solutions in a PEM electrolysis cell". International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 33 (17): 4649–4654. Bibcode:2008IJHE...33.4649M. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2008.05.029.

- ^ Melero, Juan A.; Van Grieken, Rafael; Morales, Gabriel; Paniagua, Marta (2007). "Acidic mesoporous silica for the acetylation of glycerol: Synthesis of bioadditives to petrol fuel". Energy & Fuels. 21 (3): 1782–1791. Bibcode:2007EnFue..21.1782M. doi:10.1021/ef060647q.

- ^ Özeren, Hüsamettin D.; Olsson, Richard T.; Nilsson, Fritjof; Hedenqvist, Mikael S. (1 February 2020). "Prediction of plasticization in a real biopolymer system (starch) using molecular dynamics simulations". Materials & Design. 187 108387. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2019.108387. ISSN 0264-1275.

- ^ Özeren, Hüsamettin Deniz; Guivier, Manon; Olsson, Richard T.; Nilsson, Fritjof; Hedenqvist, Mikael S. (7 April 2020). "Ranking Plasticizers for Polymers with Atomistic Simulations; PVT, Mechanical Properties and the Role of Hydrogen Bonding in Thermoplastic Starch". ACS Applied Polymer Materials. 2 (5): 2016–2026. Bibcode:2020AAPM....2.2016O. doi:10.1021/acsapm.0c00191.

- ^ "Dow achieves another major milestone in its quest for sustainable chemistries" (Press release). Dow Chemical Company. 15 March 2007. Archived from the original on 16 September 2009. Retrieved 13 July 2007.

- ^ Ott, L.; Bicker, M.; Vogel, H. (2006). "The catalytic dehydration of glycerol in sub- and supercritical water: a new chemical process for acrolein production". Green Chemistry. 8 (2): 214–220. doi:10.1039/b506285c.

- ^ Watanabe, Masaru; Iida, Toru; Aizawa, Yuichi; Aida, Taku M.; Inomata, Hiroshi (2007). "Acrolein synthesis from glycerol in hot-compressed water". Bioresource Technology. 98 (6): 1285–1290. Bibcode:2007BiTec..98.1285W. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2006.05.007. PMID 16797980.

- ^ Abdullah, Anas; Zuhairi Abdullah, Ahmad; Ahmed, Mukhtar; Khan, Junaid; Shahadat, Mohammad; Umar, Khalid; Alim, Md Abdul (March 2022). "A review on recent developments and progress in sustainable acrolein production through catalytic dehydration of bio-renewable glycerol". Journal of Cleaner Production. 341 130876. Bibcode:2022JCPro.34130876A. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.130876. S2CID 246853148.

- ^ Yazdani, S. S.; Gonzalez, R. (2007). "Anaerobic fermentation of glycerol: a path to economic viability for the biofuels industry". Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 18 (3): 213–219. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2007.05.002. PMID 17532205.

- ^ "Engineers Find Way To Make Ethanol, Valuable Chemicals From Waste Glycerin". ScienceDaily (Press release). 27 June 2007.

- ^ "Dow Epoxy advances glycerine-to-epichlorohydrin and liquid epoxy resins projects by choosing Shanghai site" (Press release). Dow Chemical Company. 26 March 2007. Archived from the original on 8 December 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ Glycerol clearance in alcoholic liver disease. Gut (British Society of Gastroenterology). 1982 Apr; 23(4): 257–264. D G Johnston, K G Alberti, R Wright, P G Blain

- ^ "Fatty liver disrupts glycerol metabolism in gluconeogenic and lipogenic pathways in humans". September 2018 The Journal of Lipid Research, 59, 1685–1694. Jeffrey D. Browning, Eunsook S. Jin1, Rebecca E. Murphy, and Craig R. Malloy

- ^ Molecular Human Reproduction, Volume 23, Issue 11, November 2017, pp. 725–737

- ^ Tildon, J. T.; Stevenson, J. H. Jr.; Ozand, P. T. (1976). "Mitochondrial glycerol kinase activity in rat brain". The Biochemical Journal. 157 (2): 513–516. doi:10.1042/bj1570513. PMC 1163884. PMID 183753.

- ^ Newsholme, E. A.; Taylor, K (May 1969). "Glycerol kinase activities in muscles from vertebrates and invertebrates". Biochem. J. 112 (4): 465–474. doi:10.1042/bj1120465. PMC 1187734. PMID 5801671.

- ^ Jenkins, BT, Hajra, AK (1976). "Glycerol Kinase and Dihydroxyacetone Kinase in Rat Brain" (PDF). Journal of Neurochemistry. 26 (2): 377–385. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1976.tb04491.x. hdl:2027.42/65297. PMID 3631. S2CID 14965948. Archived from the original on 21 February 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- ^ Phillips, Blaine; Titz, Bjoern; Kogel, Ulrike; Sharma, Danilal; Leroy, Patrice; Xiang, Yang; Vuillaume, Grégory; Lebrun, Stefan; Sciuscio, Davide; Ho, Jenny; Nury, Catherine; Guedj, Emmanuel; Elamin, Ashraf; Esposito, Marco; Krishnan, Subash; Schlage, Walter K.; Veljkovic, Emilija; Ivanov, Nikolai V.; Martin, Florian; Peitsch, Manuel C.; Hoeng, Julia; Vanscheeuwijck, Patrick (2017). "Toxicity of the main electronic cigarette components, propylene glycol, glycerin, and nicotine, in Sprague–Dawley rats in a 90-day OECD inhalation study complemented by molecular endpoints". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 109 (Pt 1): 315–332. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2017.09.001. PMID 28882640.

- ^ Renne, R. A.; Wehner, A. P.; Greenspan, B. J.; Deford, H. S.; Ragan, H. A.; Westerberg, R. B. (1992). "2-Week and 13-Week Inhalation Studies of Aerosolized Glycerol in Rats". International Forum for Respiratory Research. 4 (2): 95–111. Bibcode:1992InhTx...4...95R. doi:10.3109/08958379209145307.

- ^ Burrell, Chloe (2 June 2023). "Perth and Kinross parents warned as 'intoxicated' kids hospitalised by slushy drinks". The Courier. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ "Toddler 'turned grey and passed out' after drinking Slush Puppie". www.bbc.com. 31 July 2024. Retrieved 31 July 2024.

- ^ "'Not suitable for under-4s': New industry guidance issued on glycerol in slush-ice drinks". Food Standards Agency. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- ^ Hayward, Eleanor (12 March 2025). "Slushie drinks have put at least 21 young children in hospital". The Times. Archived from the original on 12 March 2025. Retrieved 12 March 2025.

- ^ "Doctors try to stop under-eights drinking slushies". BBC News. 12 March 2025. Retrieved 12 March 2025.

- ^ "Glycerol in slush ice drinks | Food Standards Scotland". www.foodstandards.gov.scot. Retrieved 4 August 2024.

- ^ "FDA Advises Manufacturers to Test Glycerin for Possible Contamination". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 4 May 2007. Archived from the original on 7 May 2007. Retrieved 8 May 2007.

- ^ Walt Bogdanich (6 May 2007). "From China to Panama, a Trail of Poisoned Medicine". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2007.

- ^ "10 Biggest Medical Scandals in History". 20 February 2013. Archived from the original on 8 January 2022. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ Lang, Les (1 July 2007). "FDA Issues Statement on Diethylene Glycol and Melamine Food Contamination". Gastroenterology. 133 (1): 5–6. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.013. ISSN 0016-5085. PMID 17631118. Archived from the original on 21 February 2022. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- ^ glyco- Archived 30 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine, dictionary.com

- ^ Holman, Jack P. (2002). Heat Transfer (9th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. pp. 600–606. ISBN 978-0-07-240655-9.

- ^ Incropera 1 Dewitt 2 Bergman 3 Lavigne 4, Frank P. 1 David P. 2 Theodore L. 3 Adrienne S. 4 (2007). Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer (6th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. pp. 941–950. ISBN 978-0-471-45728-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

External links

[edit]Glycerol

View on GrokipediaStructure and Properties

Molecular Structure

Glycerol possesses the molecular formula C₃H₈O₃ and the systematic IUPAC name propan-1,2,3-triol (EC number 200-289-5).[1] [9] Its structure consists of a linear three-carbon propane backbone with hydroxyl (-OH) groups attached to each carbon atom at positions 1, 2, and 3, represented as HOCH₂CH(OH)CH₂OH.[1] [10] This trihydric alcohol configuration features primary hydroxyl groups on the terminal carbons and a secondary hydroxyl group on the central carbon, enabling extensive hydrogen bonding.[1] The molecule exhibits a plane of symmetry bisecting the central C-H and C-OH bonds, rendering it achiral despite the potential for stereoisomerism in substituted derivatives.[1] In its most stable conformation, the carbon chain adopts a gauche arrangement to minimize steric repulsion between the hydroxyl groups, as determined by quantum chemical calculations and spectroscopic data.[1] The molecular weight is 92.09 g/mol, with bond lengths typical of aliphatic alcohols: C-O approximately 1.43 Å and O-H around 0.96 Å.[10]Physical Properties

Glycerol is a clear, colorless, odorless, syrupy viscous liquid at room temperature, which solidifies upon cooling but often supercools to remain liquid below its melting point.[1] It is hygroscopic, readily absorbing atmospheric moisture.[1] Key physical properties are summarized below:- Molecular formula: C₃H₈O₃

- Molar mass: 92.09 g/mol[1]

- Density: 1.261 g/cm³ at 20 °C[1]

- Melting point: 18 °C[1]

- Boiling point: 290 °C (decomposes)[1]

- Vapor pressure: Low, contributing to its stability[1]

- Dynamic viscosity: 1.5 Pa·s at 20 °C[11]

- Refractive index: 1.475 at 20 °C[1]

- Chromatic dispersion: Glycerol exhibits normal dispersion (refractive index decreases with increasing wavelength), which can be modeled using Cauchy's empirical equation n(λ) = A + B/λ² + C/λ⁴ (where λ is the wavelength in micrometers), with fitted coefficients A, B, and C depending on temperature and the wavelength range; detailed fits are available in studies of hygroscopic liquids including glycerol.[12]

- Flash point: 177 °C (open cup)[1]

- Autoignition temperature: 393 °C[13]

- Solubility: Miscible with water and ethanol; soluble in acetone and dioxane; sparingly soluble in hydrocarbons[1][4]