Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Eating

View on Wikipedia

Eating (also known as consuming) is the ingestion of food. In biology, this is typically done to provide a heterotrophic organism with energy and nutrients and to allow for growth. Animals and other heterotrophs must eat in order to survive – carnivores eat other animals, herbivores eat plants, omnivores consume a mixture of both plant and animal matter, and detritivores eat detritus. Fungi digest organic matter outside their bodies as opposed to animals that digest their food inside their bodies.

For humans, eating is more complex, but is typically an activity of daily living. Physicians and dieticians consider a healthful diet essential for maintaining peak physical condition. Some individuals may limit their amount of nutritional intake. This may be a result of a lifestyle choice: as part of a diet or as religious fasting. Limited consumption may be due to hunger or famine. Overconsumption of calories may lead to obesity and the reasons behind it are myriad, however, its prevalence has led some to declare an "obesity epidemic".

Eating practices among humans

[edit]

Many homes have a large kitchen area devoted to preparation of meals and food, and may have a dining room, dining hall, or another designated area for eating.

Most societies also have restaurants, food courts, and food vendors so that people may eat when away from home, when lacking time to prepare food, or as a social occasion.[1] At their highest level of sophistication, these places become "theatrical spectacles of global cosmopolitanism and myth."[2] At picnics, potlucks, and food festivals, eating is the primary purpose of a social gathering. At many social events, food and beverages are made available to attendees.

People usually have two or three meals a day.[3] Snacks of smaller amounts may be consumed between meals. Doctors in the UK recommend three meals a day (with between 400 and 600 kcal per meal),[4][5] with four to six hours between.[6] Having three well-balanced meals (described as: half of the plate with vegetables, 1/4 protein food as meat, [...] and 1/4 carbohydrates as pasta, rice)[7] will then amount to some 1800–2000 kcal, which is the average requirement for a regular person.[8]

In jurisdictions under Sharia law, it may be proscribed for Muslim adults during the daylight hours of Ramadan.[9][10][11]

Development in humans

[edit]Newborn babies do not eat adult foods. They survive solely on breast milk or infant formula.[12] Small amounts of pureed food are sometimes fed to young infants as young as two or three months old, but most infants do not eat adult food until they are between six and eight months old. Young babies eat pureed baby foods because they have few teeth and immature digestive systems. Between 8 and 12 months of age, the digestive system improves, and many babies begin eating finger foods. Their diet is still limited, however, because most babies lack molars or canines at this age, and often have a limited number of incisors. By 18 months, babies often have enough teeth and a sufficiently mature digestive system to eat the same foods as adults. Learning to eat is a messy process for children, and children often do not master neatness or eating etiquette until they are five or six years old.[13]

-

Eating with fork at a restaurant

-

Traditional way of eating in Uzbekistan

-

Girl eating with chopsticks

-

Ethiopians eating with hands

Eating positions

[edit]Eating positions vary according to the different regions of the world, as culture influences the way people eat their meals. For example, most of the Middle Eastern countries, eating while sitting on the floor is most common, and it is believed to be healthier than eating while sitting at a table.[14][15]

Eating in a reclining position was favored by the Ancient Greeks at a celebration they called a symposium, and this custom was adopted by the Ancient Romans.[16] Ancient Hebrews also adopted this posture for traditional celebrations of Passover.[17]

Compulsive overeating

[edit]Compulsive overeating, or emotional eating, is "the tendency to eat in response to negative emotions".[18] Empirical studies have indicated that anxiety leads to decreased food consumption in people with normal weight and increased food consumption in the obese.[19]

Many laboratory studies showed that overweight individuals are more emotionally reactive and are more likely to overeat when distressed than people of normal weight. Furthermore, it was consistently found that obese individuals experience negative emotions more frequently and more intensively than do normal weight persons.[20]

The naturalistic study by Lowe and Fisher compared the emotional reactivity and emotional eating of normal and overweight female college students. The study confirmed the tendency of obese individuals to overeat, but these findings applied only to snacks, not to meals. That means that obese individuals did not tend to eat more while having meals; rather, the amount of snacks they ate between meals was greater. One possible explanation that Lowe and Fisher suggest is obese individuals often eat their meals with others and do not eat more than average due to the reduction of distress because of the presence of other people. Another possible explanation would be that obese individuals do not eat more than the others while having meals due to social desirability. Conversely, snacks are usually eaten alone.[20]

Hunger and satiety

[edit]There are many physiological mechanisms that control starting and stopping a meal. The control of food intake is a physiologically complex, motivated behavioral system. Hormones such as cholecystokinin, bombesin, neurotensin, anorectin, calcitonin, enterostatin, leptin and corticotropin-releasing hormone have all been shown to suppress food intake.[21][22]

Eating rapidly leads to obesity and overeating, probably because the feelings of satiety can be slower.[23]

Initiation

[edit]

There are numerous signals given off that initiate hunger. There are environmental signals, signals from the gastrointestinal system, and metabolic signals that trigger hunger. The environmental signals come from the body's senses. The feeling of hunger could be triggered by the smell and thought of food, the sight of a plate, or hearing someone talk about food.[24] The signals from the stomach are initiated by the release of the peptide hormone ghrelin. Ghrelin is a hormone that increases appetite by signaling to the brain that a person is hungry.[25]

Environmental signals and ghrelin are not the only signals that initiate hunger, there are other metabolic signals as well. As time passes between meals, the body starts to take nutrients from long-term reservoirs.[24] When the glucose levels of cells drop (glucoprivation), the body starts to produce the feeling of hunger. The body also stimulates eating by detecting a drop in cellular lipid levels (lipoprivation).[24] Both the brain and the liver monitor the levels of metabolic fuels. The brain checks for glucoprivation on its side of the blood–brain barrier (since glucose is its fuel), while the liver monitors the rest of the body for both lipoprivation and glucoprivation.[26]

Termination

[edit]There are short-term signals of satiety that arise from the head, the stomach, the intestines, and the liver. The long-term signals of satiety come from adipose tissue.[24] The taste and odor of food can contribute to short-term satiety, allowing the body to learn when to stop eating. The stomach contains receptors to allow us to know when we are full. The intestines also contain receptors that send satiety signals to the brain. The hormone cholecystokinin is secreted by the duodenum, and it controls the rate at which the stomach is emptied.[27] This hormone is thought to be a satiety signal to the brain. Peptide YY 3-36 is a hormone released by the small intestine and it is also used as a satiety signal to the brain.[28] Insulin also serves as a satiety signal to the brain. The brain detects insulin in the blood, which indicates that nutrients are being absorbed by cells and a person is getting full. Long-term satiety comes from the fat stored in adipose tissue. Adipose tissue secretes the hormone leptin, and leptin suppresses appetite. Long-term satiety signals from adipose tissue regulates short-term satiety signals.[24]

Cessation of eating within two hours of sleeping can reduce body weight.[23]

Role of the brain

[edit]The brain stem can control food intake, because it contains neural circuits that detect hunger and satiety signals from other parts of the body.[24] The brain stem's involvement of food intake has been researched using rats. Rats that have had the motor neurons in the brain stem disconnected from the neural circuits of the cerebral hemispheres (decerebration), are unable to approach and eat food.[24] Instead, they must obtain their food in a liquid form. This research shows that the brain stem does in fact play a role in eating.

There are two peptides in the hypothalamus that produce hunger, melanin concentrating hormone (MCH) and orexin. MCH plays a bigger role in producing hunger. In mice, MCH stimulates feeding and a mutation causing the overproduction of MCH led to overeating and obesity.[29] Orexin plays a greater role in controlling the relationship between eating and sleeping. Other peptides in the hypothalamus that induce eating are neuropeptide Y (NPY) and agouti-related protein (AGRP).[24]

Satiety in the hypothalamus is stimulated by leptin. Leptin targets the receptors on the arcuate nucleus and suppresses the secretion of MCH and orexin. The arcuate nucleus also contains two more peptides that suppress hunger. The first one is cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART), the second is α-MSH (α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone).[24]

Disorders

[edit]Physiologically, eating is generally triggered by hunger, but there are numerous physical and psychological conditions that can affect appetite and disrupt normal eating patterns. These include depression, food allergies, ingestion of certain chemicals, bulimia, anorexia nervosa, pituitary gland malfunction and other endocrine problems, and numerous other illnesses and eating disorders. A chronic lack of nutritious food can cause various illnesses, and will eventually lead to starvation.

While changes in appetite can result from various physical and psychological conditions, including depression, allergies, and anxiety; anorexia and bulimia are specific eating disorders that profoundly impact the entire body.[30] In anorexia nervosa, people restrict their calorie intake out of fear of gaining weight. This malnutrition leads to an unhealthy weight, significantly impacting overall health.[31] Bulimia is characterized by recurrent episodes of binge eating, involving the consumption of a substantial amount of food within a short period. Subsequently, individuals engage in maladaptive behaviors, such as inducing vomiting, excessive physical activity, and using laxatives as compensatory measures.[32]

If eating and drinking is not possible, as is often the case when recovering from surgery, alternatives are enteral[33] nutrition and parenteral nutrition.[34]

Other animals

[edit]Birds

[edit]

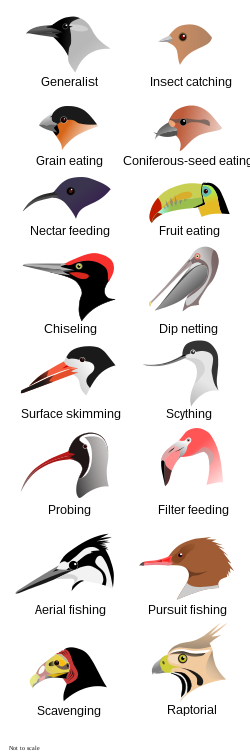

Birds' diets are varied and often include nectar, fruit, plants, seeds, carrion, and various small animals, including other birds.[35] The digestive system of birds is unique, with a crop for storage and a gizzard that contains swallowed stones for grinding food to compensate for the lack of teeth.[36] Some species such as pigeons and some psittacine species do not have a gallbladder.[37] Most birds are highly adapted for rapid digestion to aid with flight.[38] Some migratory birds have adapted to use protein stored in many parts of their bodies, including protein from the intestines, as additional energy during migration.[39]

Birds that employ many strategies to obtain food or feed on a variety of food items are called generalists, while others that concentrate time and effort on specific food items or have a single strategy to obtain food are considered specialists.[35] Avian foraging strategies can vary widely by species. Many birds glean for insects, invertebrates, fruit, or seeds. Some hunt insects by suddenly attacking from a branch. Those species that seek pest insects are considered beneficial 'biological control agents' and their presence encouraged in biological pest control programmes.[40] Combined, insectivorous birds eat 400–500 million metric tons of arthropods annually.[41]

Nectar feeders such as hummingbirds, sunbirds, lories, and lorikeets amongst others have specially adapted brushy tongues and in many cases bills designed to fit co-adapted flowers.[42] Kiwis and shorebirds with long bills probe for invertebrates; shorebirds' varied bill lengths and feeding methods result in the separation of ecological niches.[35][43] Divers, diving ducks, penguins and auks pursue their prey underwater, using their wings or feet for propulsion,[44] while aerial predators such as sulids, kingfishers and terns plunge dive after their prey. Flamingos, three species of prion, and some ducks are filter feeders.[45][46] Geese and dabbling ducks are primarily grazers.[47][48]

Some species, including frigatebirds, gulls,[49] and skuas,[50] engage in kleptoparasitism, stealing food items from other birds. Kleptoparasitism is thought to be a supplement to food obtained by hunting, rather than a significant part of any species' diet; a study of great frigatebirds stealing from masked boobies estimated that the frigatebirds stole at most 40% of their food and on average stole only 5%.[51] Other birds are scavengers; some of these, like vultures, are specialised carrion eaters, while others, like gulls, corvids, or other birds of prey, are opportunists.[52]Mammals

[edit]To maintain a high constant body temperature is energy expensive—mammals therefore need a nutritious and plentiful diet. While the earliest mammals were probably predators, different species have since adapted to meet their dietary requirements in a variety of ways. Some eat other animals—this is a carnivorous diet (and includes insectivorous diets). Other mammals, called herbivores, eat plants, which contain complex carbohydrates such as cellulose. An herbivorous diet includes subtypes such as granivory (seed eating), folivory (leaf eating), frugivory (fruit eating), nectarivory (nectar eating), gummivory (gum eating) and mycophagy (fungus eating). The digestive tract of an herbivore is host to bacteria that ferment these complex substances, and make them available for digestion, which are either housed in the multichambered stomach or in a large cecum.[53] Some mammals are coprophagous, consuming feces to absorb the nutrients not digested when the food was first ingested.[54]: 131–137 An omnivore eats both prey and plants. Carnivorous mammals have a simple digestive tract because the proteins, lipids and minerals found in meat require little in the way of specialised digestion. Exceptions to this include baleen whales who also house gut flora in a multi-chambered stomach, like terrestrial herbivores.[55]

The size of an animal is also a factor in determining diet type (Allen's rule). Since small mammals have a high ratio of heat-losing surface area to heat-generating volume, they tend to have high energy requirements and a high metabolic rate. Mammals that weigh less than about 18 ounces (510 g; 1.1 lb) are mostly insectivorous because they cannot tolerate the slow, complex digestive process of an herbivore. Larger animals, on the other hand, generate more heat and less of this heat is lost. They can therefore tolerate either a slower collection process (carnivores that feed on larger vertebrates) or a slower digestive process (herbivores).[56] Furthermore, mammals that weigh more than 18 ounces (510 g; 1.1 lb) usually cannot collect enough insects during their waking hours to sustain themselves. The only large insectivorous mammals are those that feed on huge colonies of insects (ants or termites).[57]

Some mammals are omnivores and display varying degrees of carnivory and herbivory, generally leaning in favour of one more than the other. Since plants and meat are digested differently, there is a preference for one over the other, as in bears where some species may be mostly carnivorous and others mostly herbivorous.[59] They are grouped into three categories: mesocarnivory (50–70% meat), hypercarnivory (70% and greater of meat), and hypocarnivory (50% or less of meat). The dentition of hypocarnivores consists of dull, triangular carnassial teeth meant for grinding food. Hypercarnivores, however, have conical teeth and sharp carnassials meant for slashing, and in some cases strong jaws for bone-crushing, as in the case of hyenas, allowing them to consume bones; some extinct groups, notably the Machairodontinae, had sabre-shaped canines.[58]

Some physiological carnivores consume plant matter and some physiological herbivores consume meat. From a behavioural aspect, this would make them omnivores, but from the physiological standpoint, this may be due to zoopharmacognosy. Physiologically, animals must be able to obtain both energy and nutrients from plant and animal materials to be considered omnivorous. Thus, such animals are still able to be classified as carnivores and herbivores when they are just obtaining nutrients from materials originating from sources that do not seemingly complement their classification.[60] For example, it is well documented that some ungulates such as giraffes, camels, and cattle, will gnaw on bones to consume particular minerals and nutrients.[61] Also, cats, which are generally regarded as obligate carnivores, occasionally eat grass to regurgitate indigestible material (such as hairballs), aid with haemoglobin production, and as a laxative.[62]

Many mammals, in the absence of sufficient food requirements in an environment, suppress their metabolism and conserve energy in a process known as hibernation.[63] In the period preceding hibernation, larger mammals, such as bears, become polyphagic to increase fat stores, whereas smaller mammals prefer to collect and stash food.[64] The slowing of the metabolism is accompanied by a decreased heart and respiratory rate, as well as a drop in internal temperatures, which can be around ambient temperature in some cases. For example, the internal temperatures of hibernating Arctic ground squirrels can drop to −2.9 °C (26.8 °F); however, the head and neck always stay above 0 °C (32 °F).[65] A few mammals in hot environments aestivate in times of drought or extreme heat, for example the fat-tailed dwarf lemur (Cheirogaleus medius).[66]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ John Raulston Saul (1995), "The Doubter's Companion", 155

- ^ David Grazian (2008), "On the Make: The Hustle of Urban Nightlife", 32

- ^ Lhuissier, Anne; Tichit, Christine; Caillavet, France; Cardon, Philippe; Masulo, Ana; Martin-Fernandez, Judith; Parizot, Isabelle; Chauvin, Pierre (December 2012). "Who Still Eats Three Meals a Day? Findings from a Quantitative Survey in the Paris Area". Appetite. 63: 59–69. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2012.12.012. PMID 23274963. S2CID 205609995. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ "Be calorie smart 400-600-600". nhs.uk. Archived from the original on 26 May 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ "Cut down on your calories". nhs.uk. 15 October 2015. Archived from the original on 4 June 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ Sen, Debarati (27 July 2016). "How often should you eat?". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 30 May 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ "Vegetables and Fruits". The Nutrition Source. Sep 18, 2012. Archived from the original on March 7, 2021. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ^ "Daily Calorie Requirements of An Adult Male, Female". www.iloveindia.com. Archived from the original on 2017-07-13. Retrieved 2008-06-03.

- ^ Sharia and Social Engineering: p 143, R. Michael Feener - 2013

- ^ FOOD & EATING IN MEDIEVAL EUROPE - Page 73, Joel T. Rosenthal - 1998

- ^ Conscious Eating: Second Edition - Page 9, Gabriel Cousens, M.D. - 2009

- ^ "How to combine breast and bottle feeding". nhs.uk. Archived from the original on 28 September 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ^ Insight, Food (2021-10-27). "Infant and Toddler Feeding from Birth to 23 Months: Making Every Bite Count". Food Insight. Retrieved 2024-05-11.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Donovan, Sandy (2010). The Middle Eastern American Experience. United States: Twenty-First Century Books. p. 68. ISBN 9780761363613.

- ^ Brito, Leonardo Barbosa Barreto de; Ricardo, Djalma Rabelo; Araújo, Denise Sardinha Mendes Soares de; Ramos, Plínio Santos; Myers, Jonathan; Araújo, Claudio Gil Soares de (2012-12-13). "Ability to sit and rise from the floor as a predictor of all-cause mortality". European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 21 (7): 892–898. doi:10.1177/2047487312471759. ISSN 2047-4873. PMID 23242910. S2CID 9652533. Archived from the original on 2013-01-12.

- ^ "The Roman Banquet". The Met. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 2019-04-13. Retrieved 2019-04-13.

- ^ "Reclining". A Virtual Passover. Archived from the original on 2019-10-23. Retrieved 2019-04-13.

- ^ Eldredge, K. L.; Agras, W. S. (1994). "Weight and Shape Overconcern and Emotional Eating in Binge Eating Disorder". International Journal of Eating Disorders. 19 (1): 73–82. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199601)19:1<73::AID-EAT9>3.0.CO;2-T. PMID 8640205.

- ^ McKenna, R. J. (1972). "Some Effects of Anxiety Level and Food Cues on the Eating Behavior of Obese and Normal Subjects: A Comparison of Schachterian and Psychosomatic Conceptions". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 22 (3): 311–319. doi:10.1037/h0032925. PMID 5047384.

- ^ a b Lowe, M. R.; Fisher, E. B. Jr (1983). "Emotional Reactivity, Emotional Eating, and Obesity: A Naturalistic Study". Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 6 (2): 135–149. doi:10.1007/bf00845377. PMID 6620370. S2CID 9682166.

- ^ Geiselman, P.J. (1996). Control of food intake. A physiologically complex, motivated behavioral system. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1996 Dec;25(4):815-29.

- ^ "omim". Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ a b Hurst Y, Fukuda H (2018). "Effects of changes in eating speed on obesity in patients with diabetes: a secondary analysis of longitudinal health check-up data". BMJ Open. 8 (1). Article no. e019589. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019589. PMC 5855475. PMID 29440054.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Carlson, Neil (2010). Physiology of Behavior. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. pp. 412–426.

- ^ Funai, M.D., Edmund. "Ghrelin, Hormone That Stimulates Appetite, Found to Be Higher in PWS". Archived from the original on 31 May 2012. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ^ Berg, JM. "Section 30.2Each Organ Has a Unique Metabolic Profile". Biochemistry 5th Edition. W H Freeman. Archived from the original on 13 December 2014. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ^ Little, TJ; Horowitz, M; Feinle-Bisset, C. (2005). "Role of cholecystokinin in appetite control and body weight regulation". Obesity Reviews. 6 (4): 297–306. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00212.x. PMID 16246215. S2CID 32196674.

- ^ Degen, L (2005). "Effect of peptide YY3-36 on food intake in humans". Gastroenterology. 129 (5): 1430–6. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2005.09.001. PMID 16285944.

- ^ Shimada, M. "MCH (Melanin Concentrating Hormone) and MCH-2 Receptor". Mice lacking Melanin-Concentrating Hormone are hypophagic and lean. Archived from the original on 5 September 2009. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ^ Baenas, I., Etxandi, M., & Fernández-Aranda, F. (2023). Medical complications in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Complicaciones médicas en anorexia y bulimia nerviosa. Medicina clinica, S0025-7753(23)00478-5. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcli.2023.07.028

- ^ Robatto, A. P., Magalhães Cunha, C., & Moreira, L. A. C. (2023). Diagnosis and treatment of eating disorders in children and adolescents. Jornal de pediatria, S0021-7557(23)00155-9. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2023.12.001

- ^ Yu, Z., & Muehleman, V. (2023). Eating Disorders and Metabolic Diseases. International journal of environmental research and public health, 20(3), 2446. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032446

- ^ "Pediatric Feeding Tube". Feeding Clinic of Santa Monica. Archived from the original on 2 March 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ Heisler, Jennifer. "Surgery." About.com. N.p., May–June 2010. Web. 13 Mar. 2013.

- ^ a b c Gill, Frank (1995). Ornithology. New York: WH Freeman and Co. ISBN 0-7167-2415-4.

- ^ Gionfriddo, James P.; Best (1 February 1995). "Grit Use by House Sparrows: Effects of Diet and Grit Size" (PDF). Condor. 97 (1): 57–67. doi:10.2307/1368983. JSTOR 1368983. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Hagey, Lee R.; Vidal, Nicolas; Hofmann, Alan F.; Krasowski, Matthew D. (2010). "Complex Evolution of Bile Salts in Birds". The Auk. 127 (4): 820–831. doi:10.1525/auk.2010.09155. PMC 2990222. PMID 21113274.

- ^ Attenborough, David (1998). The Life of Birds. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01633-X.

- ^ Battley, Phil F.; Piersma, T; Dietz, MW; Tang, S; Dekinga, A; Hulsman, K (January 2000). "Empirical evidence for differential organ reductions during trans-oceanic bird flight". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 267 (1439): 191–195. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.0986. PMC 1690512. PMID 10687826. (Erratum in Proceedings of the Royal Society B 267(1461):2567.)

- ^ Reid, N. (2006). "Birds on New England wool properties – A woolgrower guide" (PDF). Land, Water & Wool Northern Tablelands Property Fact Sheet. Australian Government – Land and Water Australia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 March 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ^ Nyffeler, M.; Şekercioğlu, Ç. H.; Whelan, C. J. (August 2018). "Insectivorous birds consume an estimated 400–500 million tons of prey annually". The Science of Nature. 105 (7–8): 47. Bibcode:2018SciNa.105...47N. doi:10.1007/s00114-018-1571-z. PMC 6061143. PMID 29987431.

- ^ Paton, D. C.; Collins, B.G. (1 April 1989). "Bills and tongues of nectar-feeding birds: A review of morphology, function, and performance, with intercontinental comparisons". Australian Journal of Ecology. 14 (4): 473–506. Bibcode:1989AusEc..14..473P. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9993.1989.tb01457.x.

- ^ Baker, Myron Charles; Baker, Ann Eileen Miller (1 April 1973). "Niche Relationships Among Six Species of Shorebirds on Their Wintering and Breeding Ranges". Ecological Monographs. 43 (2): 193–212. Bibcode:1973EcoM...43..193B. doi:10.2307/1942194. JSTOR 1942194.

- ^ Schreiber, Elizabeth Anne; Joanna Burger (2001). Biology of Marine Birds. Boca Raton: CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-9882-7.

- ^ Cherel, Yves; Bocher, P; De Broyer, C; Hobson, KA (2002). "Food and feeding ecology of the sympatric thin-billed Pachyptila belcheri and Antarctic P. desolata prions at Iles Kerguelen, Southern Indian Ocean". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 228: 263–281. Bibcode:2002MEPS..228..263C. doi:10.3354/meps228263.

- ^ Jenkin, Penelope M. (1957). "The Filter-Feeding and Food of Flamingoes (Phoenicopteri)". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 240 (674): 401–493. Bibcode:1957RSPTB.240..401J. doi:10.1098/rstb.1957.0004. JSTOR 92549.

- ^ Hughes, Baz; Green, Andy J. (2005). "Feeding Ecology". In Kear, Janet (ed.). Ducks, Geese and Swans. Oxford University Press. pp. 42–44. ISBN 978-0-19-861008-3.

- ^ Li, Zhiheng; Clarke, Julia A. (2016). "The Craniolingual Morphology of Waterfowl (Aves, Anseriformes) and Its Relationship with Feeding Mode Revealed Through Contrast-Enhanced X-Ray Computed Tomography and 2D Morphometrics". Evolutionary Biology. 43 (1): 12–25. Bibcode:2016EvBio..43...12L. doi:10.1007/s11692-015-9345-4.

- ^ Takahashi, Akinori; Kuroki, Maki; Niizuma, Yasuaki; Watanuki, Yutaka (December 1999). "Parental Food Provisioning Is Unrelated to Manipulated Offspring Food Demand in a Nocturnal Single-Provisioning Alcid, the Rhinoceros Auklet". Journal of Avian Biology. 30 (4): 486. doi:10.2307/3677021. JSTOR 3677021.

- ^ Bélisle, Marc; Giroux (1 August 1995). "Predation and kleptoparasitism by migrating Parasitic Jaegers" (PDF). The Condor. 97 (3): 771–781. doi:10.2307/1369185. JSTOR 1369185. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Vickery, J. A. (May 1994). "The Kleptoparasitic Interactions between Great Frigatebirds and Masked Boobies on Henderson Island, South Pacific". The Condor. 96 (2): 331–340. doi:10.2307/1369318. JSTOR 1369318.

- ^ Hiraldo, F. C.; Blanco, J. C.; Bustamante, J. (1991). "Unspecialized exploitation of small carcasses by birds". Bird Studies. 38 (3): 200–207. Bibcode:1991BirdS..38..200H. doi:10.1080/00063659109477089. hdl:10261/47141.

- ^ Langer P (July 1984). "Comparative anatomy of the stomach in mammalian herbivores". Quarterly Journal of Experimental Physiology. 69 (3): 615–625. doi:10.1113/expphysiol.1984.sp002848. PMID 6473699. S2CID 30816018.

- ^ Feldhamer GA, Drickamer LC, Vessey SH, Merritt JF, Krajewski C (2007). Mammalogy: Adaptation, Diversity, Ecology (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8695-9. OCLC 124031907.

- ^ Sanders JG, Beichman AC, Roman J, Scott JJ, Emerson D, McCarthy JJ, Girguis PR (September 2015). "Baleen whales host a unique gut microbiome with similarities to both carnivores and herbivores". Nature Communications. 6 8285. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.8285S. doi:10.1038/ncomms9285. PMC 4595633. PMID 26393325.

- ^ Speaksman JR (1996). "Energetics and the evolution of body size in small terrestrial mammals" (PDF). Symposia of the Zoological Society of London (69): 69–81. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- ^ Wilson DE, Burnie D, eds. (2001). Animal: The Definitive Visual Guide to the World's Wildlife. DK Publishing. pp. 86–89. ISBN 978-0-7894-7764-4. OCLC 46422124.

- ^ a b Van Valkenburgh B (July 2007). "Deja vu: the evolution of feeding morphologies in the Carnivora". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 47 (1): 147–163. doi:10.1093/icb/icm016. PMID 21672827.

- ^ Sacco T, van Valkenburgh B (2004). "Ecomorphological indicators of feeding behaviour in the bears (Carnivora: Ursidae)". Journal of Zoology. 263 (1): 41–54. doi:10.1017/S0952836904004856.

- ^ Singer MS, Bernays EA (2003). "Understanding omnivory needs a behavioral perspective". Ecology. 84 (10): 2532–2537. Bibcode:2003Ecol...84.2532S. doi:10.1890/02-0397.

- ^ Hutson JM, Burke CC, Haynes G (1 December 2013). "Osteophagia and bone modifications by giraffe and other large ungulates". Journal of Archaeological Science. 40 (12): 4139–4149. Bibcode:2013JArSc..40.4139H. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2013.06.004.

- ^ "Why Do Cats Eat Grass?". Pet MD. Archived from the original on 10 December 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ Geiser F (2004). "Metabolic rate and body temperature reduction during hibernation and daily torpor". Annual Review of Physiology. 66: 239–274. doi:10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032102.115105. PMID 14977403. S2CID 22397415.

- ^ Humphries MM, Thomas DW, Kramer DL (2003). "The role of energy availability in Mammalian hibernation: a cost-benefit approach". Physiological and Biochemical Zoology. 76 (2): 165–179. doi:10.1086/367950. PMID 12794670. S2CID 14675451.

- ^ Barnes BM (June 1989). "Freeze avoidance in a mammal: body temperatures below 0 degree C in an Arctic hibernator". Science. 244 (4912): 1593–1595. Bibcode:1989Sci...244.1593B. doi:10.1126/science.2740905. PMID 2740905.

- ^ Fritz G (2010). "Aestivation in Mammals and Birds". In Navas CA, Carvalho JE (eds.). Aestivation: Molecular and Physiological Aspects. Progress in Molecular and Subcellular Biology. Vol. 49. Springer-Verlag. pp. 95–113. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-02421-4. ISBN 978-3-642-02420-7.