Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Carbohydrate

View on Wikipedia

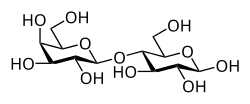

A carbohydrate (/ˌkɑːrboʊˈhaɪdreɪt/) is a sugar (saccharide) or a sugar derivative.[1] For the simplest carbohydrates, the carbon-to-hydrogen-to-oxygen atomic ratio is 1:2:1, i.e. they are often represented by the empirical formula C(H2O)n. Together with amino acids, fats, and nucleic acids, the carbohydrates are one of the major families of biomolecules.[2]

Carbohydrates perform numerous roles in living organisms.[3] Polysaccharides serve as an energy store (e.g., starch and glycogen) and as structural components (e.g., cellulose in plants and chitin in arthropods and fungi). The 5-carbon monosaccharide ribose is an important component of coenzymes (e.g., ATP, FAD and NAD) and the backbone of the genetic molecule known as RNA. The related deoxyribose is a component of DNA. Saccharides and their derivatives play key roles in the immune system, fertilization, preventing pathogenesis, blood clotting, and development.[4]

Carbohydrates are central to nutrition and are found in a wide variety of natural and processed foods. Starch is a polysaccharide and is abundant in cereals (wheat, maize, rice), potatoes, and processed food based on cereal flour, such as bread, pizza or pasta. Sugars appear in human diet mainly as table sugar (sucrose, extracted from sugarcane or sugar beets), lactose (abundant in milk), glucose and fructose, both of which occur naturally in honey, many fruits, and some vegetables. Table sugar, milk, or honey is often added to drinks and many prepared foods such as jam, biscuits and cakes.

Terminology

[edit]The term "carbohydrate" has many synonyms and the definition can depend on context. Terms associated with carbohydrate include "sugar", "saccharide", "glucan",[5] and "glucide".[6] In food science and the term "carbohydrate" often means any food that is rich in the starch (such as cereals, bread and pasta) or simple carbohydrates, or fairly simple sugars such as sucrose (found in candy, jams, and desserts). Carbohydrates can also refer to dietary fiber, like cellulose.[7][8]

Saccharides

[edit]The starting point for discussion of carbohydrates are the saccharides. Monosaccharides are the simplest carbohydrates in that they cannot be hydrolyzed to smaller carbohydrates. Monosaccharides usually have the formula Cm (H2O)n. Disaccharides (e.g. sucrose) are common as are polysaccharides/oligosaccharides (e.g., starch, cellulose). Saccharides are polyhydroxy aldehydes, ketones as well as derived polymers having linkages of the acetal type. They may be classified according to their degree of polymerization. Many polyols are also classified as carbohydrates. In many carbohydrates the OH groups are appended to or replaced by N-acetyl (e.g., chitin), sulfate (e.g., glycosaminoglycans), carboxylic acid and deoxy modifications (e.g., fucose and sialic acid).[6]

| Class (degree of polymerization) |

Subgroup | Components |

|---|---|---|

| Sugars (1–2) | Monosaccharides | Glucose, galactose, fructose, xylose |

| Disaccharides | Sucrose, lactose, maltose, isomaltulose, trehalose | |

| Polyols | Sorbitol, mannitol | |

| Oligosaccharides (3–9) | Malto-oligosaccharides | Maltodextrins |

| Other oligosaccharides | Raffinose, stachyose, fructo-oligosaccharides | |

| Polysaccharides (>9) | Starch | Amylose, amylopectin, modified starches |

| Non-starch polysaccharides | Glycogen, Cellulose, Hemicellulose, Pectins, Hydrocolloids |

Complex carbohydrates

[edit]

Sugars may be linked to other types of biological molecules to form glycoconjugates. The enzymatic process of glycosylation creates sugars/saccharides linked to themselves and to other molecules by the glycosidic bond, thereby producing glycans. Glycoproteins, proteoglycans and glycolipids are the most abundant glycoconjugates found in mammalian cells. They are found predominantly on the outer cell membrane and in secreted fluids. Glycoconjugates have been shown to be important in cell-cell interactions due to the presence on the cell surface of various glycan binding receptors in addition to the glycoconjugates themselves.[10][11] In addition to their function in protein folding and cellular attachment, the N-linked glycans of a protein can modulate the protein's function, in some cases acting as an on-off switch.[12]

History

[edit]

The history of carbohydrates, to some extent, is the history of sugar cane, which was first grown in New Guinea. The mass cultivation occurred in India where techniques were developed for the isolatoin of crystalline sugar.[13] Cane sugar and its cultivation reached Europe around the 13th Century and then expanded to the New World, where industrialization occurred.

The chemistry and biochemistry of carbohydrates can be traced to 1811. On that year Constantin Kirchhoff discovered that grape sugar (glucose) forms when starch is boiled with acid. The starch industry started the following year. Henri Braconnot discovered in 1819 that sugar is formed through the action of sulfuric acid on cellulose. William Prout, after chemical analyses of sugar and starch by Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac and Thénard, gave this group of substances the group name "saccharine." The term "carbohydrate" was first proposed by German chemist Carl Schmidt (chemist) in 1844. In 1856, glycogen, a form of carbohydrate storage in animal livers, was discovered by French physiologist Claude Bernard.[14] Emil Fischer received the 1902 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work on sugars and purines. For the discovery of glucose metabolism, Otto Meyerhof received the 1922 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Hans von Euler-Chelpin, together with Arthur Harden, received the 1929 Nobel Prize in Chemistry "for their research on sugar fermentation and the role of enzymes in this process." In 1947, both Bernardo Houssay for his discovery of the role of the pituitary gland in carbohydrate metabolism and Carl and Gerty Cori for their discovery of the conversion of glycogen received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. For the discovery of sugar nucleotides in carbohydrate biosynthesis, Luis Leloir received the 1970 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

The term glycobiology[15] was coined in 1988 by Raymond Dwek to recognize the coming together of the traditional disciplines of carbohydrate chemistry and biochemistry.[16] This coming together was as a result of a much greater understanding of the cellular and molecular biology of glycans. "Glycoscience" is a field that explores the structures and functions of glycans.[17]

Nutrition

[edit]

Carbohydrate consumed in food yields 3.87 kilocalories of energy per gram for simple sugars,[18] and 3.57 to 4.12 kilocalories per gram for complex carbohydrate in most other foods.[19] Relatively high levels of carbohydrate are associated with processed foods or refined foods made from plants, including sweets, cookies and candy, table sugar, honey, soft drinks, breads and crackers, jams and fruit products, pastas and breakfast cereals. Refined carbohydrates from processed foods such as white bread or rice, soft drinks, and desserts are readily digestible, and many are known to have a high glycemic index, which reflects a rapid assimilation of glucose. By contrast, the digestion of whole, unprocessed, fiber-rich foods such as beans, peas, and whole grains produces a slower and steadier release of glucose and energy into the body.[20] Animal-based foods generally have the lowest carbohydrate levels, although milk does contain a high proportion of lactose.

Organisms typically cannot metabolize all types of carbohydrate to yield energy. Glucose is a nearly universal and accessible source of energy. Many organisms also have the ability to metabolize other monosaccharides and disaccharides but glucose is often metabolized first. In Escherichia coli, for example, the lac operon will express enzymes for the digestion of lactose when it is present, but if both lactose and glucose are present, the lac operon is repressed, resulting in the glucose being used first (see: Diauxie). Polysaccharides are also common sources of energy. Many organisms can easily break down starches into glucose; most organisms, however, cannot metabolize cellulose or other polysaccharides such as chitin and arabinoxylans. These carbohydrate types can be metabolized by some bacteria and protists. Ruminants and termites, for example, use microorganisms to process cellulose, fermenting it to caloric short-chain fatty acids. Even though humans lack the enzymes to digest fiber, dietary fiber represents an important dietary element for humans. Fibers promote healthy digestion, help regulate postprandial glucose and insulin levels, reduce cholesterol levels, and promote satiety.[21]

The Institute of Medicine recommends that American and Canadian adults get between 45 and 65% of dietary energy from whole-grain carbohydrates.[22] The Food and Agriculture Organization and World Health Organization jointly recommend that national dietary guidelines set a goal of 55–75% of total energy from carbohydrates, but only 10% directly from sugars (their term for simple carbohydrates).[23] A 2017 Cochrane Systematic Review concluded that there was insufficient evidence to support the claim that whole grain diets can affect cardiovascular disease.[24]

Carbohydrates are one of the main components of insoluble dietary fiber. Although it is not digestible by humans, cellulose and insoluble dietary fiber generally help maintain a healthy digestive system by facilitating bowel movements.[7] Other polysaccharides contained in dietary fiber include resistant starch and inulin, which feed some bacteria in the microbiota of the large intestine, and are metabolized by these bacteria to yield short-chain fatty acids.[7][25][26]

Classification

[edit]The term complex carbohydrate was first used in the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs publication Dietary Goals for the United States (1977) where it was intended to distinguish sugars from other carbohydrates (which were perceived to be nutritionally superior).[27] However, the report put "fruit, vegetables and whole-grains" in the complex carbohydrate column, despite the fact that these may contain sugars as well as polysaccharides. The standard usage, however, is to classify carbohydrates chemically: simple if they are sugars (monosaccharides and disaccharides) and complex if they are polysaccharides (or oligosaccharides).[7][28] Carbohydrates are sometimes divided into "available carbohydrates", which are absorbed in the small intestine and "unavailable carbohydrates", which pass to the large intestine, where they are subject to fermentation by the gastrointestinal microbiota.[7]

Glycemic index

[edit]The glycemic index (GI) and glycemic load concepts characterize the potential for carbohydrates in food to raise blood glucose compared to a reference food (generally pure glucose).[29] Expressed numerically as GI, carbohydrate-containing foods can be grouped as high-GI (score more than 70), moderate-GI (56–69), or low-GI (less than 55) relative to pure glucose (GI=100).[29] Consumption of carbohydrate-rich, high-GI foods causes an abrupt increase in blood glucose concentration that declines rapidly following the meal, whereas low-GI foods with lower carbohydrate content produces a lower blood glucose concentration that returns gradually after the meal.[29]

Glycemic load is a measure relating the quality of carbohydrates in a food (low- vs. high-carbohydrate content – the GI) by the amount of carbohydrates in a single serving of that food.[29]

Health effects of dietary carbohydrate restriction

[edit]Low-carbohydrate diets may miss the health advantages – such as increased intake of dietary fiber and phytochemicals – afforded by high-quality plant foods such as legumes and pulses, whole grains, fruits, and vegetables.[30][31] A "meta-analysis, of moderate quality," included as adverse effects of the diet halitosis, headache and constipation.[32][better source needed]

Carbohydrate-restricted diets can be as effective as low-fat diets in helping achieve weight loss over the short term when overall calorie intake is reduced.[33] An Endocrine Society scientific statement said that "when calorie intake is held constant [...] body-fat accumulation does not appear to be affected by even very pronounced changes in the amount of fat vs carbohydrate in the diet."[33] In the long term, low-carbohydrate diets do not appear to confer a "metabolic advantage," and effective weight loss or maintenance depends on the level of calorie restriction,[33] not the ratio of macronutrients in a diet.[34] The reasoning of diet advocates that carbohydrates cause undue fat accumulation by increasing blood insulin levels, but a more balanced diet that restricts refined carbohydrates can also reduce serum glucose and insulin levels and may also suppress lipogenesis and promote fat oxidation.[35] However, as far as energy expenditure itself is concerned, the claim that low-carbohydrate diets have a "metabolic advantage" is not supported by clinical evidence.[33][36] Further, it is not clear how low-carbohydrate dieting affects cardiovascular health, although two reviews showed that carbohydrate restriction may improve lipid markers of cardiovascular disease risk.[37][38]

Carbohydrate-restricted diets are no more effective than a conventional healthy diet in preventing the onset of type 2 diabetes, but for people with type 2 diabetes, they are a viable option for losing weight or helping with glycemic control.[39][40][41] There is limited evidence to support routine use of low-carbohydrate dieting in managing type 1 diabetes.[42] The American Diabetes Association recommends that people with diabetes should adopt a generally healthy diet, rather than a diet focused on carbohydrate or other macronutrients.[41]

An extreme form of low-carbohydrate diet – the ketogenic diet – is established as a medical diet for treating epilepsy.[43] Through celebrity endorsement during the early 21st century, it became a fad diet as a means of weight loss, but with risks of undesirable side effects, such as low energy levels and increased hunger, insomnia, nausea, and gastrointestinal discomfort.[scientific citation needed][43] The British Dietetic Association named it one of the "top 5 worst celeb diets to avoid in 2018".[43]

Sources

[edit]

Most dietary carbohydrates contain glucose, either as their only building block (as in the polysaccharides starch and glycogen), or together with another monosaccharide (as in the hetero-polysaccharides sucrose and lactose).[44] Unbound glucose is one of the main ingredients of honey. Glucose is extremely abundant and has been isolated from a variety of natural sources across the world, including male cones of the coniferous tree Wollemia nobilis in Rome,[45] the roots of Ilex asprella plants in China,[46] and straws from rice in California.[47]

| Food item |

Carbohydrate, total,A including dietary fiber |

Total sugars |

Free fructose |

Free glucose |

Sucrose | Ratio of fructose/ glucose |

Sucrose as proportion of total sugars (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fruits | |||||||

| Apple | 13.8 | 10.4 | 5.9 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 19.9 |

| Apricot | 11.1 | 9.2 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 5.9 | 0.7 | 63.5 |

| Banana | 22.8 | 12.2 | 4.9 | 5.0 | 2.4 | 1.0 | 20.0 |

| Fig, dried | 63.9 | 47.9 | 22.9 | 24.8 | 0.9 | 0.93 | 0.15 |

| Grapes | 18.1 | 15.5 | 8.1 | 7.2 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 1 |

| Navel orange | 12.5 | 8.5 | 2.25 | 2.0 | 4.3 | 1.1 | 50.4 |

| Peach | 9.5 | 8.4 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 4.8 | 0.9 | 56.7 |

| Pear | 15.5 | 9.8 | 6.2 | 2.8 | 0.8 | 2.1 | 8.0 |

| Pineapple | 13.1 | 9.9 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 6.0 | 1.1 | 60.8 |

| Plum | 11.4 | 9.9 | 3.1 | 5.1 | 1.6 | 0.66 | 16.2 |

| Vegetables | |||||||

| Beet, red | 9.6 | 6.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 6.5 | 1.0 | 96.2 |

| Carrot | 9.6 | 4.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 3.6 | 1.0 | 77 |

| Red pepper, sweet | 6.0 | 4.2 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 0.0 |

| Onion, sweet | 7.6 | 5.0 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 14.3 |

| Sweet potato | 20.1 | 4.2 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 0.9 | 60.3 |

| Yam | 27.9 | 0.5 | Traces | Traces | Traces | — | Traces |

| Sugar cane | 13–18 | 0.2–1.0 | 0.2–1.0 | 11–16 | 1.0 | high | |

| Sugar beet | 17–18 | 0.1–0.5 | 0.1–0.5 | 16–17 | 1.0 | high | |

| Grains | |||||||

| Corn, sweet | 19.0 | 6.2 | 1.9 | 3.4 | 0.9 | 0.61 | 15.0 |

^A The carbohydrate value is calculated in the USDA database and does not always correspond to the sum of the sugars, the starch, and the "dietary fiber".

Metabolism

[edit]Carbohydrate metabolism is the series of biochemical processes responsible for the formation, breakdown and interconversion of carbohydrates in living organisms.

The most important carbohydrate is glucose, a simple sugar (monosaccharide) that is metabolized by nearly all known organisms. Glucose and other carbohydrates are part of a wide variety of metabolic pathways across species: plants synthesize carbohydrates from carbon dioxide and water by photosynthesis storing the absorbed energy internally, often in the form of starch or lipids. Plant components are consumed by animals and fungi, and used as fuel for cellular respiration. Oxidation of one gram of carbohydrate yields approximately 16 kJ (4 kcal) of energy, while the oxidation of one gram of lipids yields about 38 kJ (9 kcal). The human body stores between 300 and 500 g of carbohydrates depending on body weight, with the skeletal muscle contributing to a large portion of the storage.[49] Energy obtained from metabolism (e.g., oxidation of glucose) is usually stored temporarily within cells in the form of ATP.[50] Organisms capable of anaerobic and aerobic respiration metabolize glucose and oxygen (aerobic) to release energy, with carbon dioxide and water as byproducts.

Catabolism

[edit]Catabolism is the metabolic reaction which cells undergo to break down larger molecules, extracting energy. There are two major metabolic pathways of monosaccharide catabolism: glycolysis and the citric acid cycle.

In glycolysis, oligo- and polysaccharides are cleaved first to smaller monosaccharides by enzymes called glycoside hydrolases. The monosaccharide units can then enter into monosaccharide catabolism. A 2 ATP investment is required in the early steps of glycolysis to phosphorylate Glucose to Glucose 6-Phosphate (G6P) and Fructose 6-Phosphate (F6P) to Fructose 1,6-biphosphate (FBP), thereby pushing the reaction forward irreversibly.[49] In some cases, as with humans, not all carbohydrate types are usable as the digestive and metabolic enzymes necessary are not present.

Analytical tools

[edit]Many techniques are used in the analysis of glycans.[51] NMR spectroscopy is common, the major challenge being spectral overlap.[52] [53]

High-resolution mass spectrometry (MS) and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)

[edit]MS and HPLC are commonly applied to glycan cleaved either enzymatically or chemically from the target.[54] In case of glycolipids, they can be analyzed directly without separation of the lipid component.

N-glycans from glycoproteins are analyzed routinely by high-performance-liquid-chromatography (reversed phase, normal phase and ion exchange HPLC) after tagging the reducing end of the sugars with a fluorescent compound (reductive labeling).[55] A large variety of different labels were introduced in the recent years, where 2-aminobenzamide (AB), anthranilic acid (AA), 2-aminopyridin (PA), 2-aminoacridone (AMAC) and 3-(acetylamino)-6-aminoacridine (AA-Ac) are just a few of them.[56] Different labels have to be used for different ESI modes and MS systems used.[57]

O-glycans are usually analysed without any tags.

Fractionated glycans from high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) instruments can be further analyzed by MALDI-TOF-MS(MS) to get further information about structure and purity. Sometimes glycan pools are analyzed directly by mass spectrometry without prefractionation, although a discrimination between isobaric glycan structures is more challenging or even not always possible. Anyway, direct MALDI-TOF-MS analysis can lead to a fast and straightforward illustration of the glycan pool.[58]

High performance liquid chromatography online coupled to mass spectrometry is useful. By choosing porous graphitic carbon as a stationary phase for liquid chromatography, even non derivatized glycans can be analyzed. Detection is here done by mass spectrometry, but in instead of MALDI-MS, electrospray ionisation (ESI) is more frequently used.[59][60][61]

Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM)

[edit]Although MRM has been used extensively in metabolomics and proteomics, its high sensitivity and linear response over a wide dynamic range make it especially suited for glycan biomarker research and discovery. MRM is performed on a triple quadrupole (QqQ) instrument, which is set to detect a predetermined precursor ion in the first quadrupole, a fragmented in the collision quadrupole, and a predetermined fragment ion in the third quadrupole. It is a non-scanning technique, wherein each transition is detected individually and the detection of multiple transitions occurs concurrently in duty cycles. This technique is being used to characterize the immune glycome.[12][62]

Chemical synthesis and manipulation of carbohydrates

[edit]Carbohydrate synthesis is a sub-field of organic chemistry concerned specifically with the generation of natural and unnatural carbohydrate structures. Carbohydrate chemistry is a large and economically important branch of organic chemistry. This can include the synthesis of monosaccharide residues or structures containing more than one monosaccharide, known as oligosaccharides. Selective formation of glycosidic linkages and selective reactions of hydroxyl groups are very important, and the usage of protecting groups is extensive.

Some of the main organic reactions that involve carbohydrates are:

- Amadori rearrangement

- Carbohydrate acetalisation

- Carbohydrate digestion

- Cyanohydrin reaction

- Koenigs–Knorr reaction

- Lobry de Bruyn–Van Ekenstein transformation

- Nef reaction

- Wohl degradation

- Tipson-Cohen reaction

- Ferrier rearrangement

- Ferrier II reaction

Related topics

See also

[edit]- Gluconeogenesis – A process where glucose can be synthesized by non-carbohydrate sources.

- Glycobiology

- Glycogen

- Glycoinformatics

- Glycolipid

- Glycome

- Glycomics

- Glycosyl

- Macromolecule

- Saccharic acid

References

[edit]- ^ "Carbohydrate". IUPAC Gold Book.

- ^ "Essentials of Glycobiology". National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Nelson, David L.; Cox, Michael M. (2005). Principles of Biochemistry (4th ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman. p. 293-324. ISBN 0-7167-4339-6.

- ^ Maton A, Hopkins J, McLaughlin CW, Johnson S, Warner MQ, LaHart D, Wright JD (1993). Human Biology and Health. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. pp. 52–59. ISBN 978-0-13-981176-0.

- ^ Avenas P (2012). "Etymology of main polysaccharide names" (PDF). In Navard P (ed.). The European Polysaccharide Network of Excellence (EPNOE). Wien: Springer-Verlag. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 9, 2018. Retrieved January 28, 2018.

- ^ a b Matthews CE, Van Holde KE, Ahern KG (1999). Biochemistry (3rd ed.). Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 978-0-8053-3066-3.[page needed]

- ^ a b c d e "Fiber". Micronutrient Information Center, Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University. March 2019. Retrieved January 19, 2025.

- ^ "Chapter 1 – The role of carbohydrates in nutrition". Carbohydrates in human nutrition. FAO Food and Nutrition Paper – 66. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved December 21, 2015.

- ^ Alquwaizani M, Buckley L, Adams C, Fanikos J (June 2013). "Anticoagulants: A Review of the Pharmacology, Dosing, and Complications". Current Emergency and Hospital Medicine Reports. 1 (2): 83–97. doi:10.1007/s40138-013-0014-6. PMC 3654192. PMID 23687625.

- ^ Ma BY, Mikolajczak SA, Yoshida T, Yoshida R, Kelvin DJ, Ochi A (2004). "CD28 T cell costimulatory receptor function is negatively regulated by N-linked carbohydrates". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 317 (1): 60–7. Bibcode:2004BBRC..317...60M. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.03.012. PMID 15047148.

- ^ Takahashi M, Tsuda T, Ikeda Y, Honke K, Taniguchi N (2004). "Role of N-glycans in growth factor signaling". Glycoconj. J. 20 (3): 207–12. doi:10.1023/B:GLYC.0000024252.63695.5c. PMID 15090734. S2CID 1110879.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

immune_glycanwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Denham, Tim (October 2011). "Early Agriculture and Plant Domestication in New Guinea and Island Southeast Asia". Current Anthropology. 52 (54): S161 – S512. doi:10.1086/658682. ISSN 0011-3204 – via The University of Chicago Press Journals.

- ^ Young, F. G. (June 22, 1957). "Claude Bernard and the Discovery of Glycogen". British Medical Journal. 1 (5033): 1431–1437. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5033.1431. ISSN 0007-1447. PMC 1973429. PMID 13436813.

- ^ "Essentials of Glycobiology". National Library of Medicine. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

- ^ Rademacher TW, Parekh RB, Dwek RA (1988). "Glycobiology". Annu. Rev. Biochem. 57 (1): 785–838. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.57.070188.004033. PMID 3052290.

- ^ "U.S. National Research Council Report, Transforming Glycoscience: A Roadmap for the Future". Archived from the original on October 20, 2014. Retrieved October 3, 2012.

- ^ "Show Foods". usda.gov. Archived from the original on October 3, 2017. Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- ^ "Calculation of the Energy Content of Foods – Energy Conversion Factors". fao.org. Archived from the original on May 24, 2010. Retrieved August 2, 2013.

- ^ "Carbohydrate reference list" (PDF). www.diabetes.org.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 14, 2016. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ Pichon L, Huneau JF, Fromentin G, Tomé D (May 2006). "A high-protein, high-fat, carbohydrate-free diet reduces energy intake, hepatic lipogenesis, and adiposity in rats". The Journal of Nutrition. 136 (5): 1256–1260. doi:10.1093/jn/136.5.1256. PMID 16614413.

- ^ Food and Nutrition Board (2002/2005). Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein and Amino Acids. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press. Page 769 Archived September 12, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 0-309-08537-3.

- ^ Joint WHO/FAO expert consultation (2003). [1] (PDF). Geneva: World Health Organization. pp. 55–56. ISBN 92-4-120916-X.

- ^ Kelly SA, Hartley L, Loveman E, Colquitt JL, Jones HM, Al-Khudairy L, et al. (August 2017). "Whole grain cereals for the primary or secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8 (8) CD005051. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005051.pub3. PMC 6484378. PMID 28836672. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2018. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ^ Cummings JH (2001). The Effect of Dietary Fiber on Fecal Weight and Composition (3rd ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-8493-2387-4. Archived from the original on April 2, 2019. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- ^ Byrne CS, Chambers ES, Morrison DJ, Frost G (September 2015). "The role of short chain fatty acids in appetite regulation and energy homeostasis". International Journal of Obesity. 39 (9): 1331–1338. doi:10.1038/ijo.2015.84. PMC 4564526. PMID 25971927.

- ^ Joint WHO/FAO expert consultation (1998), Carbohydrates in human nutrition, chapter 1 Archived January 15, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 92-5-104114-8.

- ^ "Carbohydrates". The Nutrition Source. Harvard School of Public Health. September 18, 2012. Archived from the original on May 7, 2013. Retrieved April 3, 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load". Micronutrient Information Center, Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University. 2025. Retrieved January 19, 2025.

- ^ Seidelmann SB, Claggett B, Cheng S, Henglin M, Shah A, Steffen LM, et al. (September 2018). "Dietary carbohydrate intake and mortality: a prospective cohort study and meta-analysis". The Lancet. Public Health (Meta-analysis). 3 (9): e419 – e428. doi:10.1016/s2468-2667(18)30135-x. PMC 6339822. PMID 30122560.

- ^ Reynolds A, Mann J, Cummings J, Winter N, Mete E, Te Morenga L (February 2019). "Carbohydrate quality and human health: a series of systematic reviews and meta-analyses" (PDF). Lancet (Review). 393 (10170): 434–445. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31809-9. PMID 30638909. S2CID 58632705. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 11, 2021. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- ^ Churuangsuk C, Kherouf M, Combet E, Lean M (December 2018). "Low-carbohydrate diets for overweight and obesity: a systematic review of the systematic reviews" (PDF). Obesity Reviews (Systematic review). 19 (12): 1700–1718. doi:10.1111/obr.12744. PMID 30194696. S2CID 52174104. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 23, 2019. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Schwartz MW, Seeley RJ, Zeltser LM, Drewnowski A, Ravussin E, Redman LM, Leibel RL (August 2017). "Obesity Pathogenesis: An Endocrine Society Scientific Statement". Endocrine Reviews. 38 (4): 267–296. doi:10.1210/er.2017-00111. PMC 5546881. PMID 28898979.

- ^ Butryn ML, Clark VL, Coletta MC (2012). "Behavioral approaches to the treatment of obesity". In Akabas SR, Lederman SA, Moore BJ (eds.). Textbook of Obesity. New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 259. ISBN 978-0-470-65588-7.

Taken together, these findings indicate that calorie intake, not macronutrient composition, determines long-term weight loss maintenance.

- ^ Lopes da Silva MV, de Cassia Goncalves Alfenas R (2011). "Effect of the glycemic index on lipid oxidation and body composition". Nutrición Hospitalaria. 26 (1): 48–55. doi:10.3305/nh.2011.26.1.5008 (inactive September 5, 2025). PMID 21519729.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of September 2025 (link) - ^ Hall KD (March 2017). "A review of the carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (Review). 71 (3): 323–326. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2016.260. PMID 28074888. S2CID 54484172.

- ^ Mansoor N, Vinknes KJ, Veierød MB, Retterstøl K (February 2016). "Effects of low-carbohydrate diets v. low-fat diets on body weight and cardiovascular risk factors: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". The British Journal of Nutrition. 115 (3): 466–479. doi:10.1017/S0007114515004699. PMID 26768850. S2CID 21670516.

- ^ Gjuladin-Hellon T, Davies IG, Penson P, Amiri Baghbadorani R (March 2019). "Effects of carbohydrate-restricted diets on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in overweight and obese adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis" (PDF). Nutrition Reviews (Systematic review). 77 (3): 161–180. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuy049. PMID 30544168. S2CID 56488132. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 6, 2020. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- ^ Brouns F (June 2018). "Overweight and diabetes prevention: is a low-carbohydrate-high-fat diet recommendable?". European Journal of Nutrition (Review). 57 (4): 1301–1312. doi:10.1007/s00394-018-1636-y. PMC 5959976. PMID 29541907.

- ^ Meng Y, Bai H, Wang S, Li Z, Wang Q, Chen L (September 2017). "Efficacy of low carbohydrate diet for type 2 diabetes mellitus management: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 131: 124–131. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2017.07.006. PMID 28750216.

- ^ a b American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee (January 2019). "5. Lifestyle Management: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2019". Diabetes Care. 42 (Suppl 1): S46 – S60. doi:10.2337/dc19-S005. PMID 30559231. Archived from the original on December 18, 2018. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- ^ Seckold R, Fisher E, de Bock M, King BR, Smart CE (March 2019). "The ups and downs of low-carbohydrate diets in the management of Type 1 diabetes: a review of clinical outcomes". Diabetic Medicine (Review). 36 (3): 326–334. doi:10.1111/dme.13845. PMID 30362180. S2CID 53102654.

- ^ a b c "Top 5 worst celeb diets to avoid in 2018". British Dietetic Association. December 7, 2017. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

The British Dietetic Association (BDA) today revealed its much-anticipated annual list of celebrity diets to avoid in 2018. The line-up this year includes Raw Vegan, Alkaline, Pioppi and Ketogenic diets as well as Katie Price's Nutritional Supplements.

- ^ "Carbohydrates and Blood Sugar". The Nutrition Source. August 5, 2013. Archived from the original on January 30, 2017. Retrieved January 30, 2017 – via Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

- ^ Venditti A, Frezza C, Vincenti F, Brodella A, Sciubba F, Montesano C, et al. (February 2019). "A syn-ent-labdadiene derivative with a rare spiro-β-lactone function from the male cones of Wollemia nobilis". Phytochemistry. 158: 91–95. Bibcode:2019PChem.158...91V. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2018.11.012. PMID 30481664. S2CID 53757166.

- ^ Lei Y, Shi SP, Song YL, Bi D, Tu PF (May 2014). "Triterpene saponins from the roots of Ilex asprella". Chemistry & Biodiversity. 11 (5): 767–775. doi:10.1002/cbdv.201300155. PMID 24827686. S2CID 40353516.

- ^ Balan V, Bals B, Chundawat SP, Marshall D, Dale BE (2009). "Lignocellulosic Biomass Pretreatment Using AFEX". Biofuels. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 581. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. pp. 61–77. Bibcode:2009biof.book...61B. doi:10.1007/978-1-60761-214-8_5. ISBN 978-1-60761-213-1. PMID 19768616.

- ^ "FoodData Central". fdc.nal.usda.gov.

- ^ a b Maughan R (June 2013). "Surgery Oxford". www.onesearch.cuny.edu.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Mehta S (October 9, 2013). "Energetics of Cellular Respiration (Glucose Metabolism)". Biochemistry Notes, Notes. Archived from the original on January 25, 2018. Retrieved October 15, 2015.

- ^ Essentials of Glycobiology (2nd ed.). Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. 2009. ISBN 978-0-87969-770-9.

- ^ Fontana, Carolina; Widmalm, Göran (2023). "Primary Structure of Glycans by NMR Spectroscopy". Chemical Reviews. 123 (3): 1040–1102. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.2c00580. PMC 9912281. PMID 36622423.

- ^ Aizpurua-Olaizola, O.; Toraño, J. Sastre; Falcon-Perez, J.M.; Williams, C.; Reichardt, N.; Boons, G.-J. (2018). "Mass spectrometry for glycan biomarker discovery". TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry. 100: 7–14. doi:10.1016/j.trac.2017.12.015. hdl:1874/364403.

- ^ Wada Y, Azadi P, Costello CE, et al. (April 2007). "Comparison of the methods for profiling glycoprotein glycans—HUPO Human Disease Glycomics/Proteome Initiative multi-institutional study". Glycobiology. 17 (4): 411–22. doi:10.1093/glycob/cwl086. PMID 17223647.

- ^ Hase S, Ikenaka T, Matsushima Y (November 1978). "Structure analyses of oligosaccharides by tagging of the reducing end sugars with a fluorescent compound". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 85 (1): 257–63. Bibcode:1978BBRC...85..257H. doi:10.1016/S0006-291X(78)80037-0. PMID 743278.

- ^ Pabst M, Kolarich D, Pöltl G, et al. (January 2009). "Comparison of fluorescent labels for oligosaccharides and introduction of a new postlabeling purification method". Anal. Biochem. 384 (2): 263–73. doi:10.1016/j.ab.2008.09.041. PMID 18940176.

- ^ Šoić, Dinko; Mlinarić, Zvonimir; Lauc, Gordan; Gornik, Olga; Novokmet, Mislav; Keser, Toma (2022). "In a pursuit of optimal glycan fluorescent label for negative MS mode for high-throughput N-glycan analysis". Frontiers in Chemistry. 10 999770. Bibcode:2022FrCh...10.9770S. doi:10.3389/fchem.2022.999770. ISSN 2296-2646. PMC 9574008. PMID 36262345.

- ^ Harvey DJ, Bateman RH, Bordoli RS, Tyldesley R (2000). "Ionisation and fragmentation of complex glycans with a quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer fitted with a matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation ion source". Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 14 (22): 2135–42. Bibcode:2000RCMS...14.2135H. doi:10.1002/1097-0231(20001130)14:22<2135::AID-RCM143>3.0.CO;2-#. PMID 11114021.

- ^ Schulz, BL; Packer NH, NH; Karlsson, NG (December 2002). "Small-scale analysis of O-linked oligosaccharides from glycoproteins and mucins separated by gel electrophoresis". Anal. Chem. 74 (23): 6088–97. doi:10.1021/ac025890a. PMID 12498206.

- ^ Pabst M, Bondili JS, Stadlmann J, Mach L, Altmann F (July 2007). "Mass plus retention time equals structure: a strategy for the analysis of N-glycans by carbon LC-ESI-MS and its application to fibrin N-glycans". Anal. Chem. 79 (13): 5051–7. doi:10.1021/ac070363i. PMID 17539604.

- ^ Ruhaak LR, Deelder AM, Wuhrer M (May 2009). "Oligosaccharide analysis by graphitized carbon liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry". Anal Bioanal Chem. 394 (1): 163–74. doi:10.1007/s00216-009-2664-5. PMID 19247642.

- ^ Flowers, Sarah A.; Ali, Liaqat; Lane, Catherine S.; Olin, Magnus; Karlsson, Niclas G. (April 1, 2013). "Selected reaction monitoring to differentiate and relatively quantitate isomers of sulfated and unsulfated core 1 O-glycans from salivary MUC7 protein in rheumatoid arthritis". Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 12 (4): 921–931. doi:10.1074/mcp.M113.028878. ISSN 1535-9484. PMC 3617339. PMID 23457413.

Further reading

[edit]- "Compolition of foods raw, processed, prepared" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture. September 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 31, 2016. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

External links

[edit]- Carbohydrates, including interactive models and animations (Requires MDL Chime)

- IUPAC-IUBMB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature (JCBN): Carbohydrate Nomenclature

- Carbohydrates detailed

- Carbohydrates and Glycosylation – The Virtual Library of Biochemistry, Molecular Biology and Cell Biology

- Functional Glycomics Gateway, a collaboration between the Consortium for Functional Glycomics and Nature Publishing Group