Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Shortage

View on Wikipedia

In economics, a shortage or excess demand is a situation in which the demand for a product or service exceeds its supply in a market. It is the opposite of an excess supply (surplus).

Definitions

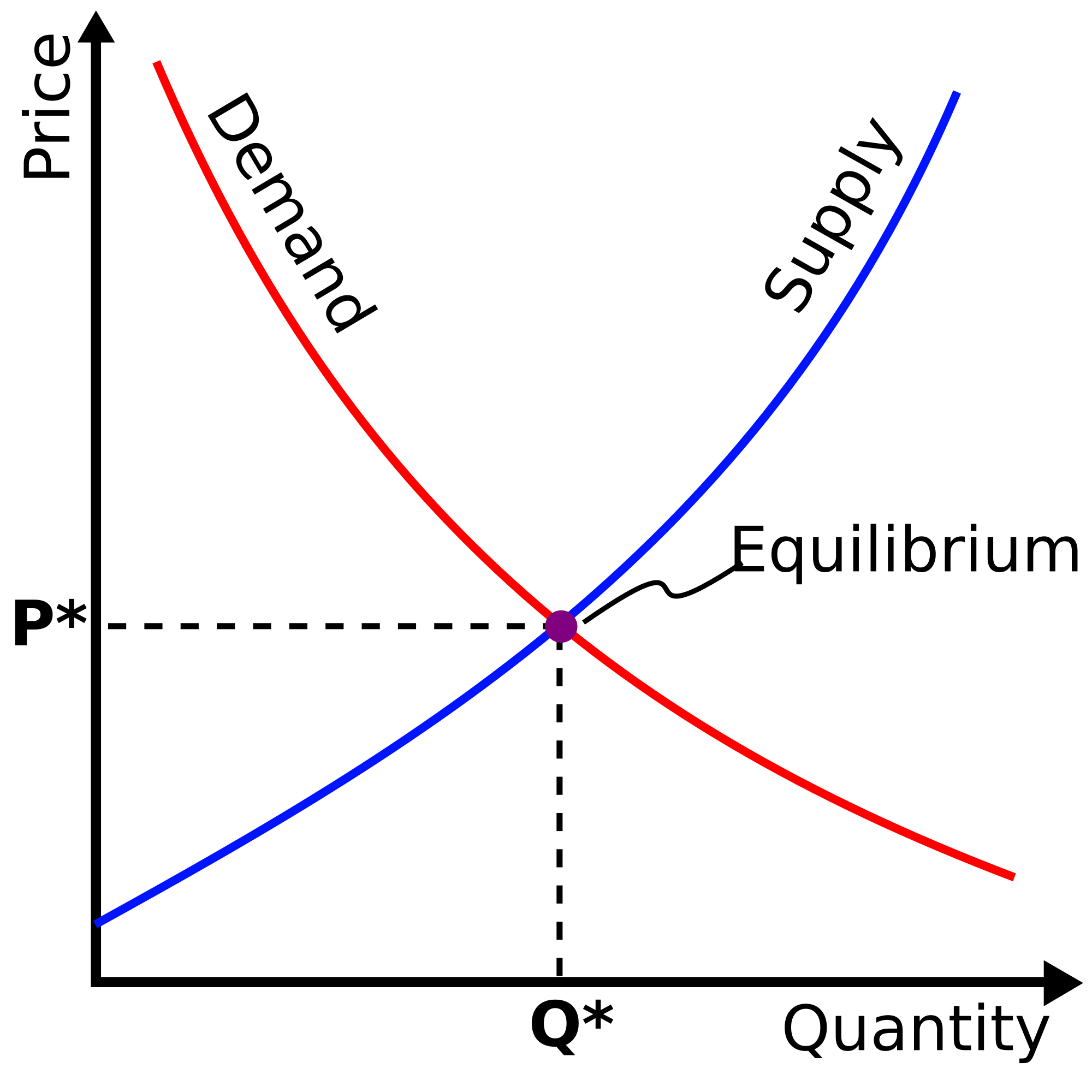

[edit]In a perfect market (one that matches a simple microeconomic model), an excess of demand will prompt sellers to increase prices until demand at that price matches the available supply, establishing market equilibrium.[1][2] In economic terminology, a shortage occurs when for some reason (such as government intervention, or decisions by sellers not to raise prices) the price does not rise to reach equilibrium. In this circumstance, buyers want to purchase more at the market price than the quantity of the good or service that is available, and some non-price mechanism (such as "first come, first served" or a lottery) determines which buyers are served. So in a perfect market the only thing that can cause a shortage is price.

In common use, the term "shortage" may refer to a situation where most people are unable to find a desired good at an affordable price, especially where supply problems have increased the price.[3] "Market clearing" happens when all buyers and sellers willing to transact at the prevailing price are able to find partners. There are almost always willing buyers at a lower-than-market-clearing price; the narrower technical definition doesn't consider failure to serve this demand as a "shortage", even if it would be described that way in a social or political context (which the simple model of supply and demand does not attempt to encompass).

Causes

[edit]Shortages (in the technical sense) may be caused by the following causes:

- Price ceilings, a type of price control which involves a government-imposed limit on the price of a product or service.

- Anti-price gouging laws.

- Government ban on the sale of a product or service, such as prostitution or certain recreational drugs.

- Decisions by suppliers not to raise prices, for example to maintain friendly relationships with potential future customers during a supply disruption.

- Artificial scarcity.

Effects

[edit]Decisions which result in a below-market-clearing price help some people and hurt others. In this case, shortages may be accepted because they theoretically enable a certain portion of the population to purchase a product that they couldn't afford at the market-clearing price. The cost is to those who are willing to pay for a product and either can't, or experience greater difficulty in doing so.

In the case of government intervention in the market, there is always a trade-off with positive and negative effects. For example, a price ceiling may cause a shortage, but it will also enable a certain percentage of the population to purchase a product that they couldn't afford at market costs.[3] Economic shortages caused by higher transaction costs and opportunity costs (e.g., in the form of lost time) also mean that the distribution process is wasteful. Both of these factors contribute to a decrease in aggregate wealth.

Shortages may or will cause:[3]

- Black (illegal) and Grey (unregulated) markets in which products that are unavailable in conventional markets are sold, or in which products with excess demand are sold at higher prices than in the conventional market.

- Artificial controls of demand, such as time (such as waiting in line at queues) and rationing.

- Non-monetary bargaining methods, such as time (for example queuing), nepotism, or even violence.

- Panic buying

- Price discrimination.

- The inability to purchase a product, and subsequent forced saving.

- Increase in demand for substitute goods.

- Deadweight loss due to artificial scarcity; a net loss of economic welfare to society occurs when an artificial limit of supply (by monopolies or oligopolies to maximise profits), limits the number of people who can enjoy the good.

Examples

[edit]

Many regions around the world have experienced shortages in the past.

- Food shortages have occurred in the United States during the Great Depression.[4]

- Rationing in the United Kingdom and the United States occurred mainly during and after the world wars[5][6]

- Potato shortages in the Netherlands triggered the 1917 Potato riots.[7][8]

- From 1920 to 1933 during prohibition in the United States, a black market for liquor was created due to the low supply of alcoholic beverages.[9]

- During the 1973 oil crisis, rationing and price controls were instituted in many countries, which caused shortages.

- In the former Soviet Union during the 1980s, prices were artificially low by fiat (i.e., high prices were outlawed).[10][11] Soviet citizens waited in line for various price-controlled goods and services such as cars, apartments, or some types of clothing. From the point of view of those waiting in line, such goods were in perpetual "short supply"; some of them were willing and able to pay more than the official price ceiling, but were legally prohibited from doing so. This method for determining the allocation of goods in short supply is known as "rationing".

- From the mid-2000s through the 2010s, shortages in Venezuela occurred, due to the Venezuelan government's economic policies;[12] such as relying on foreign imports while creating strict foreign exchange controls, put price controls in place and having expropriations result with lower domestic production. As a result of such shortages, Venezuelans had to search for products, wait in lines for hours and rationing was initiated, with the government allowing the purchase of a certain amount of products when it's available, through fingerprint recognition.[13][14][15]

- Shortages in Sudan sparked a revolution in 2019 which ended President Omar al-Bashir's 30-year rule. They continued into 2020.[16]

- Panic buying due to the COVID-19 pandemic caused food and product shortages around the world.[17]

Labour shortage

[edit]In its narrowest definition, a labour shortage is an economic condition in which employers believe there are insufficient qualified candidates (employees) to fill the marketplace demands for employment at a specific wage. Such a condition is sometimes referred to by economists as "an insufficiency in the labour force."[citation needed] According to the Frisch elasticity of labor supply lower wages reduce labour supply.[18]

In a wider definition, a widespread and persistent domestic labour shortage is caused by excessively low salaries (relative to the domestic cost of living) and adverse working conditions (excessive workload and working hours) in low-wage industries (hospitality and leisure, education, health care, rail transportation, aviation, retail, manufacturing, food, elderly care), which collectively lead to occupational burnout and attrition of existing workers, reduced incentives to attract domestic workers, short-staffing at workplaces and further exacerbation (positive feedback) of staff shortages.[19]

Labour shortages can occur even during economic periods of high unemployment or youth unemployment within specific industries due to low salaries offered.[20] In response to domestic labour shortages, some business associations such as chambers of commerce, trade associations or employers' organizations lobby for an increased immigration of foreign workers which accept lower salaries according to the global labor arbitrage.[21] In addition, business associations have campaigned for greater state provision of child care, which would enable more women to re-enter the labour workforce at a lower wage rate to achieve economic equilibrium.[22] However, lower salaries discourage local labour from entering the relevant industries and can cause labour shortages in developing countries.[23]

The Atlantic slave trade (which originated in the early 17th century but ended by the early 19th century) was said to have originated from perceived shortages of agricultural labour in the Americas (particularly in the Southern United States). It was thought that bringing African labor was the only means of malaria resistance available at the time.[24]

See also

[edit]- Aggregate demand

- Aggregate supply

- Aggregation problem

- Allocative efficiency

- Dependency ratio

- Eastern Bloc economies

- Disequilibrium

- Economic surplus

- Effective demand

- Excess demand function

- Excess supply

- Induced demand

- Keynesian formula

- Permanent Labor Certification

- Productivity-improving technologies

- Reproduction

- Scarcity

- Shortage economy

- Supply shock

References

[edit]- ^ Tucker (2014) Economics Today

- ^ "3.3 Demand, Supply, and Equilibrium". Principles of Economics. University of Minnesota. 2016-06-17.

- ^ a b c Pettinger, Tejvan (3 April 2020). "Shortages". Economics Help. Retrieved 2022-10-06.

- ^ "Depression and the Struggle for Survival". Library of Congress. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

The Great Depression of the 1930s hit Mexican immigrants especially hard. Along with the job crisis and food shortages that affected all U.S. workers, Mexicans and Mexican Americans had to face an additional threat: deportation.

- ^ "What You Need To Know About Rationing In The Second World War". Imperial War Museums. Retrieved 2022-10-06.

- ^ "Sacrificing for the Common Good: Rationing in WWII (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2022-10-06.

- ^ "Potato eaters shot". International Institute of Social History. 7 July 1917.

- ^ "Potato riots in Amsterdam". Bendigo Advertiser. 6 July 1917. p. 7 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Macias, Amanda (17 January 2020). "Prohibition began 100 years ago – here's a look at its economic impact". CNBC. Retrieved 2022-10-06.

- ^ "Why Price Controls Should Stay in the History Books". www.stlouisfed.org. Retrieved 2022-10-06.

- ^ Shapiro, Margaret (1992-01-02). "RUSSIA ENDS PRICE CONTROLS TODAY". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2022-10-06.

- ^ "Venezuela seizes warehouses packed with medical goods, food". Reuters. 2014-10-24. Retrieved 2015-12-07.

- ^ "Why are Venezuelans posting pictures of empty shelves?". BBC. 8 January 2015. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- ^ Cawthorne, Andrew (21 January 2015). "In shortages-hit Venezuela, lining up becomes a profession". Reuters. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ Schaefer Muñoz, Sara (22 October 2014). "Despite Riches, Venezuela Starts Food Rationing; Government Rolls Out Fingerprint Scanners to Limit Purchases of Basic Goods; 'How Is it Possible We've Gotten to This Extreme'". Dow Jones & Company Inc. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ^ "Sudan: Frustration grows over fuel, bread shortages". Al Jazeera. 11 March 2020.

- ^ Tyko, Kelly; Guynn, Jessica; Snider, Mike (29 February 2020). "Coronavirus Fears Empty Store Shelves of Toilet Paper, Bottled Water, Masks as Shoppers Stock up". USA Today.

- ^ Keane, Michael P. (2022). "Recent research on labor supply: Implications for tax and transfer policy". Labour Economics. 77 102026. doi:10.1016/j.labeco.2021.102026. hdl:1959.4/unsworks_80539. Retrieved 25 July 2025.

- ^ Bhattarai, Abha (2022-09-16). "Worker shortages are fueling America's biggest labor crises". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2022-10-06.

- ^ West, Darrell M. (April 10, 2013). "The Paradox of Worker Shortages at a Time of High National Unemployment". Brookings Institution. Retrieved 2022-10-06.

- ^ "U.S. Chamber's Bradley: The Current Labor Shortage is 'Unprecedented,' Urges Solutions on Immigration, Childcare". United States Chamber of Commerce. 6 May 2022. Retrieved 2022-10-06.

- ^ "Data Deep Dive: A Decline of Women in the Workforce". United States Chamber of Commerce. 27 April 2022. Retrieved 2022-10-06.

- ^ Daniel, Dana (2022-07-29). "Train your own nurses, Australia told amid global shortage". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2022-10-06.

- ^ "As American as…Plasmodium vivax?"

- Gomulka, Stanislaw: "Kornai's Soft Budget Constraint and the Shortage Phenomenon: A Criticism and Restatement", in: Economics of Planning, Vol. 19. 1985. No. 1.

- Kornai, János, Socialist Economy, Princeton University Press, 1992, ISBN 0-691-00393-9.

- Kornai, János, Economics of Shortage, Amsterdam: North Holland Press. Volume A, p. 27; Volume B, p. 196.

- Maskin, Eric, ed. (2000). Planning Shortage and Transformation: Essays in Honor of Janos Kornai, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 9780262527293

- Myant, Martin; Drahokoupil, Jan (2010). Transition Economies: Political Economy in Russia, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-470-59619-7.

External links

[edit]- János Kornai Home Page at Harvard University

- János Kornai Home Page at Collegium Budapest

- Part 1 and Part 2 of COMPARING AND ASSESSING ECONOMIC SYSTEMS, Shortage and Inflation: The Phenomenon, PPT (PowerPoint file presentation) at West Virginia University

- János Kornai 'The Soft Budget Constraint'

- David Lipton and Jeffrey Sachs 'The Consequences of Central Planning in Eastern Europe'

- On overview and critique of Kornai's account can be found in Myant, Martin; Jan Drahokoupil (2010). Transition Economies: Political Economy in Russia, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 19–23. ISBN 978-0-470-59619-7.

- Planning for the Looming Labor Shortage - A Supply Chain Perspective by HK Systems

- "America's New Immigrant Entrepreneurs" - A Duke University Study

- Criticism of high-tech shortage claims

- Disputation of High-tech Labor Shortage by Dr. Matloff

- RAND Study on Alleged Shortage of Scientists

- Shortage of skilled workers knocks red tape off top of business constraints league table - Grant Thornton IBR

- The Real Science Gap - "It's not insufficient schooling or a shortage of scientists. It's a lack of job opportunities."

Shortage

View on GrokipediaConceptual Foundations

Definition and Core Principles

A shortage occurs when the quantity demanded of a good or service exceeds the quantity supplied at the prevailing market price, resulting in excess demand and failure to achieve equilibrium.[6][7] This condition arises specifically from a disequilibrium in the supply-demand curve, where the market price is below the level at which quantities demanded and supplied would match.[8] Unlike a balanced market, shortages manifest as unmet consumer needs, often leading to visible indicators such as waiting lines or unfilled orders.[5] At its core, the principle of shortage underscores the role of price as a coordinating mechanism in markets: when demand outstrips supply, competitive pressures should drive prices upward, signaling producers to expand output and consumers to moderate purchases until equilibrium restores balance.[9] This self-correcting dynamic relies on flexible pricing without external distortions, as sustained shortages typically require interventions like price ceilings that cap adjustments and allocate goods via non-price methods such as first-come-first-served queues or government rationing.[6][10] Empirical observations, such as post-World War II housing shortages in the U.S. under rent controls, illustrate how suppressing price signals prolongs disequilibrium and fosters inefficiencies like under-maintenance of supplied units.[5] Fundamentally, shortages highlight allocative inefficiency, where resources fail to reach their highest-valued uses due to the absence of market-clearing prices; this contrasts with efficient outcomes where prices equate marginal benefit to marginal cost.[2] Producers facing shortages may ration output arbitrarily or prioritize certain buyers, distorting incentives and reducing overall welfare, as measured by deadweight loss in economic models.[10] In practice, resolving shortages demands either supply augmentation—through innovation or capacity expansion—or demand curbing, both facilitated by accurate price transmission rather than administrative overrides.[5]Distinction from Scarcity

Scarcity constitutes the perennial economic condition wherein available resources fall short of satisfying unlimited human wants, compelling individuals and societies to make allocative choices and incur opportunity costs.[11] This inherent limitation pervades all economies, driving production, trade, and innovation as agents prioritize competing ends with finite means.[12] A shortage, by comparison, manifests as a disequilibrium where quantity demanded surpasses quantity supplied at the existing price level, frequently stemming from interventions like price ceilings that suppress market signals or transient supply interruptions.[6] Unlike scarcity, shortages prove ephemeral in unregulated markets, as rising prices incentivize expanded production and curbed consumption to restore balance; persistence typically signals external barriers to adjustment.[13][12] This demarcation underscores causal mechanisms: scarcity reflects natural constraints on abundance, fostering voluntary exchanges, whereas shortages often arise from distorted incentives that hinder self-correcting price mechanisms, as evidenced in historical cases of rent controls yielding housing deficits or wartime rationing prolonging commodity gaps.[6][14]Historical Evolution of the Concept

The recognition of shortages as temporary imbalances between supply and demand predates formal economic theory, appearing in historical accounts of market disruptions such as crop failures or blockades, where quantities available fell short of needs at customary prices, prompting hoarding or black markets. For instance, during the Roman Empire's grain shortages in the 1st century BCE, state interventions like price controls under emperors such as Claudius exacerbated queues and speculation rather than resolving the disequilibrium. These events highlighted causal links between restricted supply and unmet demand, though analyzed retrospectively through modern lenses rather than as a conceptualized economic phenomenon. Classical economists in the late 18th and early 19th centuries laid foundational principles distinguishing potential shortages from inherent scarcity, emphasizing price mechanisms in competitive markets to prevent persistence. Adam Smith, in An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776), argued that if demand exceeds supply, prices rise, signaling producers to increase output until equilibrium is restored, thus viewing shortages as self-correcting signals rather than chronic states. David Ricardo extended this in On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (1817), noting that while land scarcity could drive food prices upward, free trade and specialization avert widespread shortages by reallocating resources efficiently. Thomas Malthus, in An Essay on the Principle of Population (1798), warned of population pressures creating subsistence shortages absent technological advances, but affirmed market adjustments as a natural corrective. This era shifted focus from fatalistic views of want to causal realism: shortages arise from mismatches but dissipate via incentives, contrasting with mercantilist hoarding or feudal allocations. The neoclassical synthesis in the late 19th century formalized shortage as a disequilibrium below the intersection of supply and demand curves, enabling quantitative analysis. Alfred Marshall's Principles of Economics (1890) introduced diagrammatic tools showing how a price cap creates excess demand—manifesting as queues or rationing—while equilibrium prices clear markets without surplus or deficit. This framework underscored that shortages are not inevitable but often policy-induced, as barriers like controls distort signals, a view empirically validated in wartime rationing, such as U.S. gasoline shortages under Office of Price Administration ceilings during World War II (1942–1945), where demand outstripped supply by up to 20% at fixed prices, leading to illegal markets. In the 20th century, the concept evolved to explain systemic failures in non-market systems, with János Kornai's Economics of Shortage (1980) theorizing chronic shortages in socialist economies due to centralized planning's inability to respond to dispersed knowledge, soft budget constraints allowing inefficient firms to persist, and suppressed prices fostering excess demand. Kornai's analysis, drawn from Eastern Bloc data showing persistent queues for basics like bread in Hungary (1970s), contrasted with scarcity's universality by attributing shortages to institutional distortions rather than resource limits, influencing critiques of interventionism. Empirical indices, such as those tracking U.S. newspaper mentions from 1900 onward, reveal shortages peaking during shocks like the 1918 influenza or 1973 oil embargo, confirming their episodic nature in market-oriented systems versus endemic in controlled ones.[15] This progression reflects growing emphasis on causal mechanisms—prices, incentives, and institutions—over mere observation of want.Economic Mechanisms

Supply-Demand Disequilibrium

![Supply and demand curves illustrating equilibrium][float-right] A shortage manifests as a state of market disequilibrium where the quantity demanded surpasses the quantity supplied at the prevailing price, resulting in excess demand.[6] This imbalance creates upward pressure on prices, incentivizing producers to increase output and consumers to reduce purchases until equilibrium is restored, where supply equals demand.[16] In graphical terms, the demand curve intersects the supply curve above the equilibrium point when price is fixed below its market-clearing level, leading to unfulfilled orders and rationing mechanisms such as queues or black markets.[17] Disequilibrium arises from shifts in supply or demand curves or from interventions preventing price adjustments. A sudden increase in demand, such as during a population surge or preference change, can outpace supply response, causing temporary shortages until production expands or prices rise.[18] Conversely, a supply contraction—due to resource constraints or disruptions—while demand remains steady, similarly generates excess demand at the original price.[9] Without barriers, competitive markets self-correct through price signals, but persistent disequilibrium often stems from artificial constraints like price ceilings, which cap prices below equilibrium and suppress supply incentives while stimulating demand.[19] In economic theory, this disequilibrium underscores the role of flexible prices in allocating scarce resources efficiently, as shortages signal producers to allocate more inputs toward the affected good.[20] Empirical observations, such as wartime rationing or regulated markets, confirm that enforced low prices exacerbate shortages by distorting producer responses and encouraging hoarding or diversion to unregulated channels.[5] Thus, supply-demand disequilibrium not only indicates inefficiency but also highlights the causal link between price rigidity and prolonged excess demand.[21]Role of Price Signals in Equilibrium

In competitive markets, price signals facilitate the coordination between buyers and sellers, guiding resource allocation toward equilibrium where quantity supplied equals quantity demanded. Prices act as decentralized communication devices, conveying information about relative scarcity: an increase in demand relative to supply raises prices, signaling producers to expand output while prompting consumers to reduce purchases through higher costs. This adjustment process ensures efficient rationing without central planning, as higher prices incentivize marginal producers to enter the market and existing ones to prioritize the good.[22][23] When a shortage emerges—defined as excess demand at the current price—the upward pressure on prices initiates a dynamic correction. Rising prices curb quantity demanded along the demand curve, as consumers substitute away or defer purchases, while simultaneously boosting quantity supplied by making production more profitable, shifting resources toward the scarce good. This convergence occurs at the equilibrium price, where the shortage dissipates, as evidenced by standard supply-demand models where market forces drive adjustments absent distortions. For instance, empirical observations in unregulated commodity markets, such as agricultural products during harvest fluctuations, show prices rapidly equilibrating supply shocks within weeks.[24][25][26] The efficacy of price signals hinges on their flexibility and responsiveness to underlying conditions, enabling predictive behavior: producers anticipate future scarcities via price trends, investing in capacity ahead of demand surges, as seen in energy markets where spot prices signal long-term contracts. In equilibrium, prices not only clear current markets but also incentivize innovation and efficiency, minimizing waste by aligning production with consumer valuations. Disruptions to this mechanism, such as fixed prices, impede signals and sustain disequilibria, underscoring prices' role as the primary equilibrating force in voluntary exchange systems.[27][28]Barriers to Market Clearing

Government-imposed price ceilings constitute a fundamental barrier to market clearing by capping prices below the equilibrium level where supply equals demand, thereby generating persistent excess demand and shortages. At such controlled prices, consumers seek to purchase more of the good than producers are willing or able to supply, as lower prices fail to incentivize increased production or entry by new suppliers to cover marginal costs.[29] This disequilibrium persists because the mechanism of price adjustment—rising prices signaling scarcity to ration goods and stimulate supply—is suppressed, leading producers to ration output, reduce quality, or exit the market entirely.[3] Empirical analyses confirm that price ceilings distort resource allocation, often exacerbating shortages rather than alleviating them, as seen in reduced investment and innovation in controlled sectors.[30] Regulatory restrictions, including licensing requirements and barriers to entry, further impede market clearing by raising the costs and time required for suppliers to respond to shortage signals. High regulatory hurdles, such as mandatory certifications or environmental compliance mandates, delay supply expansion even as prices attempt to rise, prolonging imbalances.[31] For instance, in industries like healthcare or transportation, protracted approval processes for new entrants prevent rapid scaling of supply to match demand surges, resulting in ongoing shortages despite potential profitability at market prices. These interventions, often justified as protecting consumers or ensuring safety, empirically hinder efficient adjustment by prioritizing non-price rationing mechanisms like queues or lotteries over voluntary exchange.[32] Historical precedents illustrate these barriers' effects. In the United States, the 1971 Economic Stabilization Act under President Nixon imposed wage and price controls that culminated in Phase IV (1973–1974), where ceilings on commodities like beef and gasoline triggered widespread shortages; meatpackers withheld supply due to unprofitable prices, and gasoline lines formed as refiners curtailed output amid the 1973 oil embargo.[33] Similarly, during World War II, U.S. price controls under the Office of Price Administration led to rationing and black markets for goods like sugar and tires, as fixed prices below equilibrium discouraged production expansions despite wartime demand.[34] In both cases, removal of controls allowed prices to rise and shortages to dissipate, underscoring the causal role of intervention in blocking clearing.[29] Additional barriers arise from market imperfections amplified by policy, such as laws prohibiting "price gouging" during emergencies, which effectively impose temporary ceilings and prevent opportunistic supply increases. Post-hurricane analyses show that such statutes correlate with prolonged shortages of essentials like water and fuel, as sellers fear penalties for raising prices to clear local markets and attract distant suppliers.[3] While proponents argue these measures curb exploitation, economic reasoning and evidence indicate they reduce overall welfare by favoring non-price allocation over efficient rationing via higher prices that reflect scarcity.[33] In command economies or heavily regulated sectors, the absence of flexible pricing altogether—replaced by administrative quotas—represents an extreme barrier, where shortages become chronic due to misaligned incentives divorced from consumer valuations.[29]Primary Causes

Exogenous Shocks and Natural Limits

Exogenous shocks refer to unanticipated external events that abruptly disrupt supply chains or production capacities, leading to shortages by reducing available goods below demand levels at prevailing prices. These shocks often originate outside the controlled economic variables, such as geopolitical conflicts or pandemics, and can propagate through global interdependence. For instance, the 1973 OPEC oil embargo against the United States and other nations supporting Israel in the Yom Kippur War halved oil exports from Arab producers, causing gasoline shortages, rationing, and price quadrupling from $3 to $12 per barrel within months.[35] [36] This event strained U.S. dependency on imported oil, which had risen to 35% of consumption by 1973, resulting in widespread fuel lines and economic contraction.[37] The COVID-19 pandemic exemplified a health-related exogenous shock, triggering factory shutdowns in China—accounting for 28% of global manufacturing—and port congestions that delayed shipments.[38] This led to acute shortages of personal protective equipment, with global demand surging 40-fold for masks and respirators while production lagged, exacerbating healthcare strains in early 2020.[39] Semiconductor shortages, intensified by automotive plant closures and a 20% drop in Taiwan's output due to quarantine measures, persisted into 2022, idling factories and inflating vehicle prices by up to 20% in affected markets.[40] Such disruptions highlight how localized shocks amplify via just-in-time inventory practices, reducing buffer stocks and magnifying supply inelasticity.[41] Natural limits impose structural constraints on supply due to finite geological or biological capacities, independent of human policy, often manifesting as chronic or escalating shortages when extraction rates exceed replenishment. Helium, a non-renewable byproduct of natural gas decay, faces recurrent global shortages because reserves are concentrated in depleting fields; the U.S. Federal Helium Reserve, once supplying 30% of world needs, ceased operations in 2021 after exhausting its primary aquifer.[42] [43] Production, limited to sites with at least 0.3% helium concentration in natural gas, dropped 10% globally post-2021 due to field closures in Algeria and Russia, driving prices from $20 to over $100 per cubic meter by 2025 and halting MRI operations and scientific experiments.[44] [45] Similarly, freshwater scarcity affects 2.4 billion people, driven by aquifer depletion where extraction exceeds recharge rates, as in California's Central Valley where groundwater levels fell 100 feet between 1960 and 2010 amid agricultural demands comprising 80% of usage.[46] These limits underscore causal realities of resource entropy, where thermodynamic and geological barriers preclude indefinite expansion without substitution or innovation.[47]Production and Supply Chain Failures

Production failures arise when manufacturing capacity is compromised, often due to operational breakdowns, quality issues, or insufficient investment in redundancy, resulting in output falling below demand levels. For instance, in February 2022, Abbott Nutrition voluntarily recalled several powdered infant formula products and shuttered its Sturgis, Michigan facility after discovering bacterial contamination linked to two infant illnesses and one death, which accounted for nearly half of U.S. production and triggered nationwide shortages peaking at 40-50% in some regions by May 2022.[48][49] This event exposed vulnerabilities from high market concentration, where four firms supply over 90% of U.S. formula, amplifying the impact of a single facility's halt.[50] Supply chain failures compound production shortfalls by interrupting the distribution of goods, frequently stemming from over-dependence on concentrated suppliers, logistical bottlenecks, or software errors in inventory systems. The 2021-2022 global semiconductor shortage exemplified this, driven partly by underinvestment in fabrication capacity and factory disruptions, leading to automotive production losses estimated at 7.7 million vehicles in 2021 alone as firms like Ford curtailed output due to chip unavailability.[51] Refined forecasts later pegged cumulative light-vehicle losses at over 9.5 million units that year, with ripple effects raising vehicle prices and delaying deliveries amid just-in-time manufacturing models that lack buffering stockpiles.[52] Historical precedents illustrate recurring patterns, such as Hershey's 1999 ERP implementation failure, which mismatched supply with Halloween demand, causing 20% of orders to go unfilled and contributing to a $150 million sales shortfall.[53] Similarly, Nike's 2001 demand-planning software glitch overordered excess inventory while underproducing popular items, resulting in over $100 million in lost sales and excess stock write-downs.[54] These cases underscore how internal mismanagement or technological glitches can sever production-to-market links, exacerbating shortages without external shocks.Policy-Induced Distortions

Government policies that interfere with market price signals, such as price ceilings, often generate shortages by capping prices below the equilibrium level where supply meets demand.[29] At these artificially low prices, quantity demanded exceeds quantity supplied, as producers reduce output due to insufficient incentives to cover costs, while consumers increase demand.[30] Empirical analyses confirm that such controls distort resource allocation, leading to inefficient outcomes including chronic shortages and black markets.[33] Rent control exemplifies this distortion in housing markets, where caps on rental prices discourage new construction and maintenance, reducing the overall supply of available units.[55] A review of empirical studies indicates that rent controls lower housing quality in regulated units and limit supply growth, exacerbating shortages for low-income tenants over time.[56] In cities like New York, long waiting lists for controlled apartments persist, with policies tying units to original tenants and stifling mobility.[57] The 1970s U.S. gasoline shortages illustrate price controls' role in amplifying supply constraints. Federal caps on fuel prices, implemented under the Nixon and Carter administrations, prevented market clearing despite the 1973 oil embargo, resulting in long queues and rationing at pumps.[58] These controls reduced incentives for domestic production and imports, prolonging shortages that might have self-corrected through higher prices signaling conservation and investment.[59] In Venezuela, extensive price controls on food and consumer goods, enacted from 2003 under Hugo Chávez, triggered widespread shortages by eroding producer incentives and domestic output.[60] By 2017, basic items like rice and milk were scarce, with scarcity indices reaching over 30% for regulated products, forcing reliance on imports and black markets amid hyperinflation.[61] These policies, intended to combat inflation, instead collapsed agricultural production, as farmers faced losses and shifted to unregulated crops or smuggling.[62] Other distortions, such as import quotas or excessive regulations, similarly hinder supply responses. For instance, agricultural subsidies in some nations favor certain crops, leading to surpluses in subsidized goods and shortages in others due to misallocated resources.[30] While minimum wage hikes can elevate labor costs, potentially causing employer-perceived shortages in low-skill sectors, evidence on employment effects remains debated, with some studies finding minimal disemployment and others documenting reduced hiring among youth.[63][64]Consequences and Impacts

Microeconomic Effects on Consumers and Producers

In microeconomic theory, a shortage arises when the quantity supplied falls short of the quantity demanded at the prevailing price, typically due to barriers preventing price adjustment such as ceilings or controls. This disequilibrium results in excess demand, quantified as the horizontal gap between the supply and demand curves at that price.[9][19] Consumers face reduced access to goods, often leading to non-price rationing mechanisms including queues, waiting lists, and purchase limits, which impose additional time and search costs beyond the monetary price.[5][7] For those who obtain the good, consumer surplus may temporarily increase due to the below-equilibrium price, but this benefit accrues unevenly, favoring early or connected buyers while excluding others, and overall societal welfare declines through deadweight loss—the foregone gains from unproduced units where marginal benefit exceeds marginal cost.[65][66] Shortages can also spur informal markets where prices rise to clear excess demand, though these carry risks like quality uncertainty or legal penalties.[34] Producers, facing guaranteed sales of their output at the controlled price but limited by the rationed demand, experience diminished producer surplus as total output contracts below the efficient level, reducing revenue relative to equilibrium.[65][66] With excess demand, incentives arise to cut quality, skimp on maintenance, or divert resources to unregulated markets, exacerbating inefficiencies over time.[67] In persistent shortages, marginal producers may exit, further contracting supply and amplifying the deadweight loss.[65]Macroeconomic Ramifications

Supply shortages represent negative aggregate supply shocks that curtail potential output, elevate production costs, and distort resource allocation across the economy. These disruptions reduce gross domestic product (GDP) by constraining industrial production and trade volumes, while simultaneously fueling inflation through heightened input prices and bottleneck pressures. For instance, econometric models estimate that a one-standard-deviation shock from supply chain disruptions—often manifesting as shortages—can lower real GDP and raise unemployment by about 0.2 percentage points in affected economies.[41] Such effects amplify when shortages propagate through interconnected sectors, leading to multiplier contractions in output as downstream industries face input scarcities.[69] Persistent shortages often engender stagflation, where inflationary surges coincide with economic stagnation and rising unemployment, challenging conventional monetary policy trade-offs. The 1973–1974 OPEC oil embargo illustrates this dynamic: production cuts quadrupled crude oil prices from approximately $3 to $12 per barrel, inducing energy shortages that propelled U.S. inflation to 11% in 1974 and contributed to a recession with GDP contracting by 0.5% that year, alongside unemployment climbing to 5.6%.[70] [36] In policy-distorted environments, shortages exacerbate fiscal imbalances; Venezuela's crisis from 2013 onward, driven by price controls and nationalizations causing chronic goods scarcities, yielded hyperinflation peaking at over 1 million percent in 2018 and a cumulative GDP collapse exceeding 75% by 2021 relative to 2013 levels.[71] [72] Longer-term, shortages inflict "scarring" on the macroeconomy by eroding capital investment, labor productivity, and potential growth trajectories, as firms defer expansions amid uncertainty and consumers reduce spending. Supply disruptions elevate inflation expectations, prompting central banks to tighten policy, which can deepen output gaps if demand remains rigid.[73] Empirical evidence from post-2020 global supply chain strains confirms these channels, with disruptions accounting for up to 40% of core goods inflation in advanced economies through mid-2022, while suppressing overall activity.[74] In import-dependent nations, shortages strain balance of payments, deplete foreign reserves, and heighten currency volatility, compounding contractionary forces.[75]Social and Political Repercussions

![Shortages in Venezuela supermarket][float-right] Shortages often intensify social divisions by disproportionately affecting lower-income groups, who lack access to black markets or alternative sources, leading to increased inequality and public health crises from malnutrition and untreated illnesses. In Venezuela during the 2010s, severe scarcities of food, medicine, and basic goods resulted in widespread looting, with reports of approximately 10 incidents per day, sometimes escalating to deadly riots amid hyperinflation exceeding 1,000,000% annually by 2018. These conditions prompted mass protests against the government, exacerbating social fragmentation and contributing to the exodus of over 7.7 million citizens by 2024, straining neighboring countries' resources and altering regional demographics.[76][71] Politically, shortages erode public trust in governing regimes, frequently catalyzing demands for accountability and policy reform, as seen in historical food riots that have toppled administrations when supply failures are attributed to mismanagement or interventionist policies. During the Arab Spring uprisings beginning in December 2010, spikes in global food prices—driven partly by weather-induced shortages—interacted with domestic scarcities to fuel protests in Tunisia, Egypt, and beyond, where bread affordability became a flashpoint for broader grievances against authoritarian rule, ultimately leading to the ouster of leaders like Zine El Abidine Ben Ali and Hosni Mubarak. In the Soviet Union, persistent bread lines in the 1980s symbolized systemic inefficiencies under central planning, fostering disillusionment that bolstered support for Mikhail Gorbachev's perestroika reforms and accelerated the USSR's dissolution in 1991.[77][78] Such repercussions extend to modern instances, where shortages from policy distortions or external shocks provoke electoral shifts or populist backlashes; for example, energy and food scarcities in Europe following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine correlated with surges in antigovernment demonstrations across multiple nations, highlighting how supply disruptions can undermine political stability even in advanced economies. Governments responding with rationing or price controls often face accusations of favoritism, further polarizing societies along class or ideological lines and inviting authoritarian measures to suppress dissent. Empirical analyses indicate that economic desperation from shortages heightens protest frequency, with data from 2022 showing inflation-driven unrest reaching record levels globally, underscoring the causal link between material deprivation and collective action against perceived state failures.[79]Mitigation and Resolution Strategies

Free-Market Adjustments

In free markets, shortages—defined as excess demand at prevailing prices—prompt automatic adjustments through the price mechanism, which rises to reflect scarcity. This elevation in price serves dual functions: it discourages low-value uses by reducing quantity demanded, as consumers shift to alternatives, delay purchases, or abstain, while signaling producers to expand output by reallocating resources from less profitable areas.[80][6] New entrants are also incentivized, as higher margins attract investment in production capacity or innovation to meet unmet demand.[81] Absent interventions like price ceilings, this process typically restores equilibrium efficiently, as evidenced by the self-correcting nature of commodity markets where temporary supply disruptions lead to price spikes followed by normalized availability.[82] Empirical instances underscore the efficacy of these dynamics. After a March 2017 windstorm in Michigan disrupted power and housing, hotel prices rose sharply from $59 to $400 per night, prompting homeowners to offer spare rooms and Airbnb listings to surge, thereby alleviating accommodation shortages without government mandates.[83] Similarly, in agricultural sectors, seasonal shortages of crops like wheat have historically resolved via price increases that curtail exports and boost domestic planting in subsequent cycles, averting persistent deficits.[84] These adjustments not only clear markets but also foster resource reallocation toward higher-value uses, contrasting with controlled environments where suppressed prices exacerbate and prolong shortages.[6] Critics of free-market responses often highlight short-term price hikes as exploitative, yet data indicate they minimize waste and expedite resolution; for example, unregulated energy markets post-1970s oil shocks saw supply expansions through exploration incentives tied to elevated prices, stabilizing availability faster than in regulated counterparts.[85] Long-term, sustained high prices from unresolved shortages drive innovation, such as hydraulic fracturing in U.S. natural gas markets during the early 2000s, which transformed perceived shortages into abundance via technological adaptation spurred by price signals.[16] This underscores the causal role of unfettered pricing in aligning supply with demand through decentralized decision-making.Government Interventions: Theoretical Basis and Empirical Critiques

Government interventions in response to shortages, such as price ceilings, subsidies, rationing, or production mandates, are theoretically grounded in addressing perceived market failures where supply disruptions cause rapid price spikes, potentially leading to inequitable access and excessive profiteering. Advocates, drawing from Keynesian frameworks, argue that state action can stabilize prices and ensure essential goods reach vulnerable populations by capping costs below equilibrium levels, thereby curbing hoarding and speculation while maintaining social welfare.[86] [87] These measures presuppose that markets alone fail to allocate scarce resources efficiently during crises, necessitating corrective policies to bridge gaps in private incentives and promote broader economic stability.[88] However, first-principles analysis of supply and demand reveals that price controls below market-clearing levels systematically generate excess demand while discouraging supply expansion, as producers face reduced profitability and consumers lack signals to moderate usage, resulting in queues, black markets, and underinvestment.[33] [30] Empirical studies corroborate this: During the 1973-1979 US energy crisis, federal price controls on gasoline—enacted under the Nixon and Ford administrations—prolonged shortages, creating mile-long lines and arbitrary rationing by preventing price signals from equilibrating supply and demand.[89] [58] In Venezuela, price controls imposed from 2003 intensified by 2010 led to shortages of staples like milk and toilet paper, with rates escalating from 5% in 2003 to over 22% by 2016 as firms ceased production amid unviable margins and currency controls.[61] [90] Similarly, rent controls—a persistent price ceiling variant—have been linked in multiple econometric analyses to diminished housing supply and maintenance, with a review of 31 studies finding consistent reductions in rental stock and quality due to muted investment incentives.[91] [55] Public choice theory further critiques these interventions by highlighting government failures: Policymakers, acting as self-interested agents, often prioritize electoral appeasement or interest-group capture over efficient outcomes, leading to distorted allocations via rent-seeking rather than genuine scarcity resolution.[92] [93] For instance, subsidies and mandates can foster dependency and moral hazard, as seen in historical cases where short-term relief extended into chronic inefficiencies, undermining long-run production capacity.[94] While some academic sources defend targeted interventions amid informational asymmetries, the preponderance of peer-reviewed evidence indicates net welfare losses, with shortages persisting or worsening absent market-price mechanisms.[95] [29]Long-Term Structural Reforms

Long-term structural reforms to address shortages emphasize enhancing the economy's supply-side capacity through institutional changes, reduced regulatory burdens, and investments in human and physical capital, thereby increasing resilience to demand fluctuations and exogenous pressures. These reforms target persistent distortions that hinder production responsiveness, such as rigid labor markets, barriers to market entry, and inadequate infrastructure, which can perpetuate mismatches between supply and demand. Empirical analyses from international organizations highlight that supply-boosting measures, including product and labor market liberalization, elevate potential output growth by fostering competition and innovation.[96][97] For instance, in transition economies during the 1990s and 2000s, implementing market-oriented reforms like privatization and price decontrols correlated positively with cumulative GDP growth and the elimination of chronic shortages, as producers responded to price signals by expanding output.[98] Labor market reforms constitute a core component, promoting flexibility through reductions in employment protection rigidities and enhancements in skills matching via vocational training and lifelong learning programs. Such measures mitigate sectoral shortages by aligning workforce skills with evolving demands, with evidence indicating that reforms increasing labor mobility and reducing firing costs improve employment rates and reduce vacancy durations over multi-year horizons.[99] In product markets, dismantling entry barriers and antitrust enforcement encourages new firm formation, which expands supply capacity; studies show these changes boost aggregate productivity by 0.5-1% annually in reformed sectors.[100] Trade liberalization further prevents shortages by integrating domestic markets with global supply chains, as demonstrated in case studies where tariff reductions in developing economies raised producer incentives and stabilized availability of inputs.[101] Infrastructure and innovation reforms, including public-private investments in logistics, digitalization, and R&D, address bottlenecks that amplify shortages during disruptions. For example, upgrading transport networks and port digitalization has been linked to 10-20% reductions in supply chain delays in analyzed economies, enabling faster replenishment and lower volatility in goods availability.[102] While short-term adjustment costs, such as temporary inequality increases from labor reallocation, may arise, long-term evidence from OECD countries confirms net gains in household incomes and output stability, underscoring the causal role of these reforms in preventing recurrent shortages through sustained supply expansion.[103][104]Case Studies and Examples

Historical Policy Failures

![Shortages of basic goods in a Venezuelan supermarket][float-right] Forced collectivization of agriculture in the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin's regime from 1928 to 1940 drastically reduced agricultural output, leading to widespread famines, particularly the Soviet famine of 1931-1934, which killed an estimated 5-7 million people.[105] The policy involved confiscating private farms and livestock, disrupting traditional farming incentives and causing a sharp decline in production as peasants slaughtered animals rather than surrender them to state collectives; grain output fell by nearly 25% between 1928 and 1933.[106] This disorganization of the rural economy, combined with excessive grain requisitions for export and urbanization, created acute food shortages across Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and other regions, exemplifying how central planning overrides local knowledge and market signals, resulting in inefficient resource allocation.[107] In the United States, President Richard Nixon's imposition of wage and price controls on August 15, 1971, under the Economic Stabilization Act, artificially suppressed gasoline prices below market-clearing levels, culminating in severe shortages during the 1973-1974 Arab oil embargo.[58] These controls discouraged domestic production and refining investments while encouraging excessive consumption, leading to long queues at pumps, rationing by odd-even license plate days in many states, and an estimated loss of 400,000 barrels per day in supply as refiners withheld output unprofitable under fixed prices.[59] The policy failure persisted until controls were phased out in 1981, after which shortages dissipated, demonstrating that price ceilings create imbalances by reducing supply incentives and fostering black markets rather than alleviating scarcity.[108] Venezuela's adoption of extensive price controls and nationalizations starting under Hugo Chávez in the late 1990s and intensified by Nicolás Maduro from 2013 onward triggered hyperinflation and chronic shortages of food, medicine, and consumer goods by the mid-2010s.[71] These measures, including fixing prices below production costs, led to producer bankruptcies and import reliance, with food production dropping 75% between 2007 and 2016, forcing supermarkets to ration essentials and citizens to queue for hours amid shelves emptied by 2016. The economy contracted by over 75% from 2014 to 2021, exacerbated by currency controls that distorted exchange rates and encouraged smuggling, underscoring how interventionist policies prioritizing redistribution over profitability erode supply chains and investment.[109]Modern Supply Disruptions (Post-2020)

![Dried pasta shelves empty in an Australian supermarket during COVID-19 shortages][float-right] The COVID-19 pandemic, beginning in early 2020, triggered widespread supply disruptions through global lockdowns, factory closures, and transportation bottlenecks, exposing vulnerabilities in just-in-time manufacturing and over-reliance on concentrated suppliers in Asia. These measures, implemented by governments to curb virus spread, halted production in key regions like China and led to port congestions, with shipping costs from Asia to the US nearly doubling by early 2022. The disruptions contributed significantly to inflation, as analyzed in studies linking supply chain frictions to price increases in goods like automobiles and consumer electronics.[41][110] A prominent example was the global semiconductor shortage, which intensified in 2021 due to surging demand for electronics amid remote work and learning, compounded by production halts in Taiwan and other hubs. This crisis cost the global automotive industry an estimated $210 billion in lost revenue in 2021, with manufacturers idling factories and reducing output by millions of vehicles, as firms like Ford and General Motors prioritized higher-margin models. The shortage stemmed from pre-existing capacity constraints exacerbated by pandemic demand shifts, rather than solely speculative hoarding, though recovery began in 2023 as inventories normalized.[51][52] Shipping container imbalances further amplified disruptions in 2021, as empty containers accumulated in the US and Europe while demand surged for imports from Asia, driven by consumer spending on goods during lockdowns. This led to delays and freight rate spikes, with transpacific shipping costs rising dramatically due to port backlogs and vessel shortages. In the US, the shortage hampered exports, illustrating how policy-induced demand distortions and logistical inefficiencies created artificial scarcities.[111] Sector-specific shortages emerged, such as the 2022 US infant formula crisis, caused by a bacterial contamination recall at Abbott Nutrition's Michigan plant in February 2022, which supplied nearly half the market, alongside lingering supply chain strains from the pandemic. This resulted in empty shelves and health risks for infants, with 81% of parents switching formulas and reporting adverse effects like digestive issues. Market concentration, with four firms dominating 90% of supply, amplified the impact of the single-plant failure.[48][50][112] Geopolitical events compounded issues, notably Europe's 2022 energy crisis following Russia's invasion of Ukraine in February, which reduced natural gas supplies via pipelines like Nord Stream by over 80%, driving wholesale prices to record highs. EU responses included diversifying imports and filling storage, averting blackouts but at the cost of industrial slowdowns and elevated poverty risks for millions. The crisis highlighted dependencies on Russian energy, with gas flows reoriented globally, underscoring how sudden supply cuts from state actors can induce shortages absent diversified reserves.[113][114][115]Sector-Specific Instances

In the housing sector, persistent shortages in the United States stem primarily from regulatory barriers that constrain new construction, including zoning restrictions and local opposition to development, which prevent supply from responding to demand pressures. As of 2023, the nation faced a shortage of over 7 million affordable rental homes for extremely low-income households, with no state or metro area offering sufficient units at prices they could afford without overburdening their budgets. Pandemic-era disruptions further slowed building, dropping new home starts and amplifying inventory constraints amid rising interest rates and inflation.[116][117][118] The semiconductor sector encountered a global shortage spanning 2020 to 2023, triggered by COVID-19-induced factory shutdowns, supply chain vulnerabilities, and surging demand for electronics, which halted production across industries. Automotive manufacturing bore significant impacts, with over 11 million vehicles idled worldwide in 2021 due to chip scarcity, incurring billions in losses and forcing plant closures by major firms like Ford and [General Motors](/page/General Motors). The crisis exposed overreliance on concentrated production in Asia and underinvestment in capacity, leading to price hikes and delays in consumer goods from appliances to medical devices.[119][120][121] Europe's energy sector grappled with a natural gas shortage in 2022, exacerbated by the Russian invasion of Ukraine severing pipeline supplies that previously met about 40% of EU needs, causing prices to spike over 10-fold from pre-crisis levels. Utilities rationed supplies, industrial output fell in gas-dependent sectors like chemicals and fertilizers, and governments mandated a 15% voluntary demand cut to avert blackouts, ultimately reducing consumption by around 100 billion cubic meters through efficiency gains and LNG imports from alternatives like the United States. This episode highlighted policy-driven dependencies on single suppliers, prompting accelerated shifts to coal and nuclear despite emissions goals.[122][114][115] In the agricultural sector, water shortages afflict production globally, with the industry accounting for 70% of freshwater withdrawals and facing risks to one-quarter of cropland from overexploitation and droughts. In California, for instance, surface water deficits during prolonged dry spells prompted a 4.2 million acre-feet surge in groundwater pumping in affected years, elevating costs and fallowing fields for crops like almonds and rice. Similar dynamics in arid regions of India and sub-Saharan Africa reduce yields of staples such as wheat and maize, compounding food price volatility without adaptive irrigation or policy reforms to curb inefficient use.[123][124][125]Labor Shortages as a Subcategory

Conceptual Framework

A labor shortage exists when the quantity of workers demanded by employers exceeds the quantity supplied at prevailing wage rates, resulting in unfilled job vacancies.[126] In economic theory, this represents a market disequilibrium where labor demand, derived from the marginal revenue product of labor, outstrips supply, which depends on workers' reservation wages influenced by alternatives, skills, and preferences.[127] Unlike temporary imbalances, persistent shortages indicate barriers to wage adjustment or structural mismatches preventing market clearing.[128] From first principles, labor demand shifts rightward due to factors like technological advancements increasing productivity or economic expansion raising output needs, while supply may contract from demographic declines, such as aging populations reducing workforce entrants, or policy-induced disincentives like high taxation on earnings.[129] Supply-side rigidities, including minimum wage laws, union bargaining power, or immigration restrictions, can prevent wages from rising to equilibrate the market, sustaining shortages as employers face higher hiring costs without attracting sufficient labor.[130] Skill mismatches arise when demand evolves faster than training systems adapt, leaving workers unqualified for available roles despite overall unemployment.[126] In a neoclassical framework, competitive markets should eliminate shortages through wage increases that draw in marginal workers or induce substitution via capital or offshoring, but empirical persistence suggests frictions like geographic immobility, asymmetric information, or institutional constraints dominate.[128] Critics argue that proclaimed "shortages" often reflect employer reluctance to offer market-clearing wages rather than absolute supply deficits, as evidenced by stagnant real wage growth amid reported vacancies.[131] Causal realism underscores that shortages are not exogenous but emerge from interplay of incentives: without addressing root supply constraints or demand pressures, interventions like subsidies risk distorting signals rather than resolving underlying disequilibria.[127]Evidence and Measurement Challenges

Measuring labor shortages empirically relies on indicators such as job vacancy rates from surveys like the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics' Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS), which tracks unfilled positions, hires, quits, and layoffs monthly, but these data face challenges from sampling variability, nonresponse adjustments, and benchmarking to payroll estimates that can introduce revisions.[132][133] For instance, JOLTS estimates for August 2025 reported 7.6 million job openings, yet methodological adjustments for unit and item nonresponse can distort disaggregated sector-specific insights, complicating assessments of true excess demand versus reporting artifacts.[133] Critics note that vacancy counts may overstate shortages if firms post duplicate or speculative openings to gauge interest without intent to hire, a practice amplified in tight markets.[134] A core tool, the Beveridge curve—plotting unemployment against vacancy rates—illustrates matching efficiency, with outward shifts signaling potential structural mismatches or shortages; post-2020, U.S. data showed such a shift, coinciding with vacancy rates exceeding 5% amid unemployment below 4%, but debates persist on whether this reflects genuine supply constraints or temporary reallocation frictions from pandemic disruptions like sector-specific quits and retirements.[135][136] Empirical challenges arise in disentangling these from policy factors, such as extended unemployment benefits or immigration restrictions, which reduced labor force participation by an estimated 2 million workers in 2021-2022 without clear evidence of skill gaps driving persistent vacancies.[136][137] Over-education in the workforce further undermines claims of qualification-based shortages, as data indicate workers often exceed job requirements rather than falling short.[137] Cross-national comparisons exacerbate measurement issues due to varying definitions: some studies define shortages via sustained high vacancy-unemployment ratios (e.g., above 1.5), while others require concurrent wage acceleration and employment growth, yet empirical tests show weak correlations, with post-COVID wage gains often tied to inflation or bargaining power rather than binding constraints.[126][138] Disaggregated employer data on job terms and applicant qualifications remain scarce, leading to reliance on aggregate proxies that overlook regional or occupational variances, such as clustered skill demands in industries like manufacturing where shortages may stem from geographic immobility rather than absolute scarcity.[138] Recent BLS payroll revisions, downward-adjusting 2024 hiring estimates by over 800,000 jobs, highlight broader data reliability concerns, potentially inflating perceived tightness if initial vacancy reports misalign with actual hires.[139] These evidentiary gaps foster debates on causality, with structural interpretations (e.g., aging populations or technological shifts) competing against cyclical or incentive-based explanations, but rigorous testing via firm-level hiring outcomes reveals tightness affects recruitment more than confirming absolute shortages, as quits and rehiring rates often equilibrate without supply expansions.[140][141] Prioritizing longitudinal, vacancy-specific data over snapshots is essential, yet institutional biases in academic assessments—favoring demand-side narratives—can undervalue supply elasticities from wage adjustments or migration, underscoring the need for unfiltered employer surveys to validate shortage claims.[138]Causal Debates and Policy Implications

Debates on the causes of labor shortages center on whether they reflect genuine supply constraints or failures in price signaling and adjustment. Economists like Peter Cappelli argue that historical data, such as stagnant or falling real wages during periods of alleged shortages in the 2000s, indicate relative labor surpluses rather than absolute deficits, suggesting firms often resist wage increases to maintain profitability margins.[142] In contrast, structural factors like demographic aging and sector-specific skills mismatches are cited as primary drivers; for instance, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics notes that no single empirical metric reliably identifies occupational shortages, but data from the 2020s show persistent gaps in fields like healthcare and manufacturing due to retirements and inadequate training pipelines.[127] Post-COVID analyses highlight temporary demand surges and supply disruptions, including early retirements and reduced participation from extended unemployment benefits, which elevated job vacancies above unemployed workers by ratios exceeding 1.5:1 in 2022, though quits rates also spiked as workers sought higher pay.[143][144] Policy-induced causes amplify these debates, with critics pointing to regulations like occupational licensing and minimum wages as distorting labor supply. Studies on minimum wage hikes, such as those analyzing U.S. county-level data, find they reduce job vacancies and hiring efforts by pricing out low-productivity workers, effectively creating shortages in entry-level roles without proportionally increasing employment.[145] Counterarguments from sources like the Economic Policy Institute claim minimal disemployment effects from wage floors, attributing shortages to employer reluctance to train or compete on non-wage factors, though this view overlooks evidence of concentrated job losses among low-skilled groups during rapid increases.[64][63] Generous unemployment insurance extensions during 2020-2021 are empirically linked to delayed workforce re-entry, prolonging tightness in leisure and hospitality sectors where participation fell by over 2 million workers.[141] Immigration policy emerges as a flashpoint in causal analysis, with data showing a post-2007 slowdown in low-skilled inflows correlating to tighter markets and declining skill premia in affected sectors.[146] Proponents argue immigrants fill gaps without displacing natives, as evidenced by their overrepresentation in shortage-prone industries like agriculture (where 70% of farmworkers are foreign-born) and construction, sustaining output amid native participation declines.[147] Skeptics, however, caution that unchecked inflows can suppress wage growth for comparable natives, though aggregate evidence from the 2010s indicates net supply expansion alleviates overall tightness.[148] Even when immigration increases, it may not fully resolve skilled labor shortages due to skill mismatches—particularly among humanitarian migrants who often lack qualifications for high-demand roles—slow integration processes including qualification recognition, training needs, and administrative hurdles; and lower employment integration rates leading to underutilization in shortage areas. These frictions persist alongside underlying demographic pressures, such as population aging, and insufficient domestic training.[149][150] Policy implications favor market-oriented responses over interventions that rigidify wages or restrict mobility. Allowing wage flexibility to clear markets, as implied by Beveridge curve shifts post-2020, could resolve mismatches faster than mandates, with empirical models showing labor constraints easing when firms face exogenous wage pressures from competing sectors. Targeted reforms, including deregulation of licensing (affecting 25% of U.S. jobs) and expanded vocational training, address structural deficits without inflating costs, as seen in sectors where apprenticeships reduced shortages by 15-20% in pilot programs.[151] Immigration adjustments, such as visa expansions for high-demand occupations, offer supply-side relief; simulations indicate that reversing recent low-inflow trends could add 1-2 million workers annually, mitigating demographic drags projected to shrink the prime-age labor force by 5 million by 2030.[152] Conversely, restrictive deportation policies risk exacerbating shortages, potentially contracting GDP by 2-6% through lost labor in construction and care sectors, underscoring the need for evidence-based calibration over ideological constraints.[153]References

- https://www.[investopedia](/page/Investopedia).com/terms/p/price-ceiling.asp