Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Extratropical cyclone

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Weather |

|---|

|

|

Extratropical cyclones, sometimes called mid-latitude cyclones or wave cyclones, are low-pressure areas which, along with the anticyclones of high-pressure areas, drive the weather over much of the Earth. Extratropical cyclones are capable of producing anything from cloudiness and mild showers to severe hail, thunderstorms, blizzards, and tornadoes. These types of cyclones are defined as large scale (synoptic) low pressure weather systems that occur in the middle latitudes of the Earth. In contrast with tropical cyclones, extratropical cyclones produce rapid changes in temperature and dew point along broad lines, called weather fronts, about the center of the cyclone.[1]

Terminology

[edit]The term "cyclone" applies to numerous types of low pressure areas, one of which is the extratropical cyclone. The descriptor extratropical signifies that this type of cyclone generally occurs outside the tropics and in the middle latitudes of Earth between 30° and 60° latitude. They are termed mid-latitude cyclones if they form within those latitudes, or post-tropical cyclones if a tropical cyclone has intruded into the mid latitudes.[1][2] Weather forecasters and the general public often describe them simply as "depressions" or "lows". Terms like frontal cyclone, frontal depression, frontal low, extratropical low, non-tropical low and hybrid low are often used as well.[citation needed]

Extratropical cyclones are classified mainly as baroclinic, because they form along zones of temperature and dewpoint gradient known as frontal zones. They can become barotropic late in their life cycle, when the distribution of heat around the cyclone becomes fairly uniform with its radius.[3]

Formation

[edit]

Extratropical cyclones form anywhere within the extratropical regions of the Earth (usually between 30° and 60° latitude from the equator), either through cyclogenesis or extratropical transition. In a climatology study with two different cyclone algorithms, a total of 49,745–72,931 extratropical cyclones in the Northern Hemisphere and 71,289–74,229 extratropical cyclones in the Southern Hemisphere were detected between 1979 and 2018 based on reanalysis data.[4] A study of extratropical cyclones in the Southern Hemisphere shows that between the 30th and 70th parallels, there are an average of 37 cyclones in existence during any 6-hour period.[5] A separate study in the Northern Hemisphere suggests that approximately 234 significant extratropical cyclones form each winter.[6]

Cyclogenesis

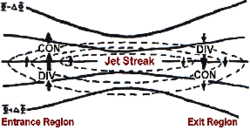

[edit]Extratropical cyclones form along linear bands of temperature/dew point gradient with significant vertical wind shear, and are thus classified as baroclinic cyclones. Initially, cyclogenesis, or low pressure formation, occurs along frontal zones near a favorable quadrant of a maximum in the upper level jetstream known as a jet streak. The favorable quadrants are usually at the right rear and left front quadrants, where divergence ensues.[7] The divergence causes air to rush out from the top of the air column. As mass in the column is reduced, atmospheric pressure at surface level (the weight of the air column) is reduced. The lowered pressure strengthens the cyclone (a low pressure system). The lowered pressure acts to draw in air, creating convergence in the low-level wind field. Low-level convergence and upper-level divergence imply upward motion within the column, making cyclones cloudy. As the cyclone strengthens, the cold front sweeps towards the equator and moves around the back of the cyclone. Meanwhile, its associated warm front progresses more slowly, as the cooler air ahead of the system is denser, and therefore more difficult to dislodge. Later, the cyclones occlude as the poleward portion of the cold front overtakes a section of the warm front, forcing a tongue, or trowal, of warm air aloft. Eventually, the cyclone will become barotropically cold and begin to weaken.[citation needed]

Atmospheric pressure can fall very rapidly when there are strong upper level forces on the system. When pressures fall more than 1 millibar (0.030 inHg) per hour, the process is called explosive cyclogenesis, and the cyclone can be described as a bomb.[8][9][10] These bombs rapidly drop in pressure to below 980 millibars (28.94 inHg) under favorable conditions such as near a natural temperature gradient like the Gulf Stream, or at a preferred quadrant of an upper-level jet streak, where upper level divergence is best. The stronger the upper level divergence over the cyclone, the deeper the cyclone can become. Hurricane-force extratropical cyclones are most likely to form in the northern Atlantic and northern Pacific oceans in the months of December and January.[11] On 14 and 15 December 1986, an extratropical cyclone near Iceland deepened to below 920 millibars (27 inHg),[12] which is a pressure equivalent to a category 5 hurricane. In the Arctic, the average pressure for cyclones is 980 millibars (28.94 inHg) during the winter, and 1,000 millibars (29.53 inHg) during the summer.[13]

Extratropical transition

[edit]

Tropical cyclones often transform into extratropical cyclones at the end of their tropical existence, usually between 30° and 40° latitude, where there is sufficient forcing from upper-level troughs or shortwaves riding the Westerlies for the process of extratropical transition to begin.[14] During this process, a cyclone in extratropical transition (known across the eastern North Pacific and North Atlantic oceans as the post-tropical stage),[15][16] will invariably form or connect with nearby fronts and/or troughs consistent with a baroclinic system. Due to this, the size of the system will usually appear to increase, while the core weakens. However, after transition is complete, the storm may re-strengthen due to baroclinic energy, depending on the environmental conditions surrounding the system.[14] The cyclone will also distort in shape, becoming less symmetric with time.[17][18][19]

During extratropical transition, the cyclone begins to tilt back into the colder airmass with height, and the cyclone's primary energy source converts from the release of latent heat from condensation (from thunderstorms near the center) to baroclinic processes. The low pressure system eventually loses its warm core and becomes a cold-core system.[19][17]

The peak time of subtropical cyclogenesis (the midpoint of this transition) in the North Atlantic is in the months of September and October, when the difference between the temperature of the air aloft and the sea surface temperature is the greatest, leading to the greatest potential for instability.[20] On rare occasions, an extratropical cyclone can transform into a tropical cyclone if it reaches an area of ocean with warmer waters and an environment with less vertical wind shear.[21] An example of this happening is in the 1991 Perfect Storm.[22] The process known as "tropical transition" involves the usually slow development of an extratropically cold core vortex into a tropical cyclone.[23][24]

The Joint Typhoon Warning Center uses the extratropical transition (XT) technique to subjectively estimate the intensity of tropical cyclones becoming extratropical based on visible and infrared satellite imagery. Loss of central convection in transitioning tropical cyclones can cause the Dvorak technique to fail;[25] the loss of convection results in unrealistically low estimates using the Dvorak technique.[26] The system combines aspects of the Dvorak technique, used for estimating tropical cyclone intensity, and the Hebert-Poteat technique, used for estimating subtropical cyclone intensity.[27] The technique is applied when a tropical cyclone interacts with a frontal boundary or loses its central convection while maintaining its forward speed or accelerating.[28] The XT scale corresponds to the Dvorak scale and is applied in the same way, except that "XT" is used instead of "T" to indicate that the system is undergoing extratropical transition.[29] Also, the XT technique is only used once extratropical transition begins; the Dvorak technique is still used if the system begins dissipating without transition.[28] Once the cyclone has completed transition and become cold-core, the technique is no longer used.[29]

Structure

[edit]

Surface pressure and wind distribution

[edit]The windfield of an extratropical cyclone constricts with distance in relation to surface level pressure, with the lowest pressure being found near the center, and the highest winds typically just on the cold/poleward side of warm fronts, occlusions, and cold fronts, where the pressure gradient force is highest.[30] The area poleward and west of the cold and warm fronts connected to extratropical cyclones is known as the cold sector, while the area equatorward and east of its associated cold and warm fronts is known as the warm sector.[citation needed]

The wind flow around an extratropical cyclone is counterclockwise in the northern hemisphere, and clockwise in the southern hemisphere, due to the Coriolis effect (this manner of rotation is generally referred to as cyclonic). Near this center, the pressure gradient force (from the pressure at the center of the cyclone compared to the pressure outside the cyclone) and the Coriolis force must be in an approximate balance for the cyclone to avoid collapsing in on itself as a result of the difference in pressure.[31] The central pressure of the cyclone will lower with increasing maturity, while outside of the cyclone, the sea-level pressure is about average. In most extratropical cyclones, the part of the cold front ahead of the cyclone will develop into a warm front, giving the frontal zone (as drawn on surface weather maps) a wave-like shape. Due to their appearance on satellite images, extratropical cyclones can also be referred to as frontal waves early in their life cycle. In the United States, an old name for such a system is "warm wave".[32]

In the northern hemisphere, once a cyclone occludes, a trough of warm air aloft—or "trowal" for short—will be caused by strong southerly winds on its eastern periphery rotating aloft around its northeast, and ultimately into its northwestern periphery (also known as the warm conveyor belt), forcing a surface trough to continue into the cold sector on a similar curve to the occluded front. The trowal creates the portion of an occluded cyclone known as its comma head, due to the comma-like shape of the mid-tropospheric cloudiness that accompanies the feature. It can also be the focus of locally heavy precipitation, with thunderstorms possible if the atmosphere along the trowal is unstable enough for convection.[33]

Vertical structure

[edit]Extratropical cyclones slant back into colder air masses and strengthen with height, sometimes exceeding 30,000 feet (approximately 9 km) in depth.[34] Above the surface of the earth, the air temperature near the center of the cyclone is increasingly colder than the surrounding environment. These characteristics are the direct opposite of those found in their counterparts, tropical cyclones; thus, they are sometimes called "cold-core lows".[35] Various charts can be examined to check the characteristics of a cold-core system with height, such as the 700 millibars (20.67 inHg) chart, which is at about 10,000 feet (3,048 meters) altitude. Cyclone phase diagrams are used to tell whether a cyclone is tropical, subtropical, or extratropical.[36]

Cyclone evolution

[edit]

There are two models of cyclone development and life cycles in common use: the Norwegian model and the Shapiro–Keyser model.[37]

Norwegian cyclone model

[edit]Of the two theories on extratropical cyclone structure and life cycle, the older is the Norwegian Cyclone Model, developed during World War I. In this theory, cyclones develop as they move up and along a frontal boundary, eventually occluding and reaching a barotropically cold environment.[38] It was developed completely from surface-based weather observations, including descriptions of clouds found near frontal boundaries. This theory still retains merit, as it is a good description for extratropical cyclones over continental landmasses.[citation needed]

Shapiro–Keyser model

[edit]A second competing theory for extratropical cyclone development over the oceans is the Shapiro–Keyser model, developed in 1990.[39] Its main differences with the Norwegian Cyclone Model are the fracture of the cold front, treating warm-type occlusions and warm fronts as the same, and allowing the cold front to progress through the warm sector perpendicular to the warm front. This model was based on oceanic cyclones and their frontal structure, as seen in surface observations and in previous projects which used aircraft to determine the vertical structure of fronts across the northwest Atlantic.[citation needed]

Warm seclusion

[edit]A warm seclusion is the mature phase of the extratropical cyclone life cycle. This was conceptualized after the ERICA field experiment of the late 1980s, which produced observations of intense marine cyclones that indicated an anomalously warm low-level thermal structure, secluded (or surrounded) by a bent-back warm front and a coincident chevron-shaped band of intense surface winds.[40] The Norwegian Cyclone Model, as developed by the Bergen School of Meteorology, largely observed cyclones at the tail end of their lifecycle and used the term occlusion to identify the decaying stages.[citation needed]

Warm seclusions may have cloud-free, eye-like features at their center (reminiscent of tropical cyclones), significant pressure falls, hurricane-force winds, and moderate to strong convection. The most intense warm seclusions often attain pressures less than 950 millibars (28.05 inHg) with a definitive lower to mid-level warm core structure.[40] A warm seclusion, the result of a baroclinic lifecycle, occurs at latitudes well poleward of the tropics.[citation needed]

As latent heat flux releases are important for their development and intensification, most warm seclusion events occur over the oceans; they may impact coastal nations with hurricane force winds and torrential rain.[39][41] Climatologically, the Northern Hemisphere sees warm seclusions during the cold season months, while the Southern Hemisphere may see a strong cyclone event such as this during all times of the year.[citation needed]

In all tropical basins, except the Northern Indian Ocean, the extratropical transition of a tropical cyclone may result in reintensification into a warm seclusion. For example, Hurricane Maria (2005) and Hurricane Cristobal (2014) each re-intensified into a strong baroclinic system and achieved warm seclusion status at maturity (or lowest pressure).[42][43]

Motion

[edit]

Extratropical cyclones are generally driven, or "steered", by deep westerly winds in a general west to east motion across both the Northern and Southern hemispheres of the Earth. This general motion of atmospheric flow is known as "zonal".[44] Where this general trend is the main steering influence of an extratropical cyclone, it is known as a "zonal flow regime".[citation needed]

When the general flow pattern buckles from a zonal pattern to the meridional pattern,[45] a slower movement in a north or southward direction is more likely. Meridional flow patterns feature strong, amplified troughs and ridges, generally with more northerly and southerly flow.[citation needed]

Changes in direction of this nature are most commonly observed as a result of a cyclone's interaction with other low pressure systems, troughs, ridges, or with anticyclones. A strong and stationary anticyclone can effectively block the path of an extratropical cyclone. Such blocking patterns are quite normal, and will generally result in a weakening of the cyclone, the weakening of the anticyclone, a diversion of the cyclone towards the anticyclone's periphery, or a combination of all three to some extent depending on the precise conditions. It is also common for an extratropical cyclone to strengthen as the blocking anticyclone or ridge weakens in these circumstances.[46]

Where an extratropical cyclone encounters another extratropical cyclone (or almost any other kind of cyclonic vortex in the atmosphere), the two may combine to become a binary cyclone, where the vortices of the two cyclones rotate around each other (known as the "Fujiwhara effect"). This most often results in a merging of the two low pressure systems into a single extratropical cyclone, or can less commonly result in a mere change of direction of either one or both of the cyclones.[47] The precise results of such interactions depend on factors such as the size of the two cyclones, their strength, their distance from each other, and the prevailing atmospheric conditions around them.[citation needed]

Effects

[edit]

General

[edit]Extratropical cyclones can bring little rain and surface winds of 15–30 km/h (10–20 mph), or they can be dangerous with torrential rain and winds exceeding 119 km/h (74 mph),[48] and so they are sometimes referred to as windstorms in Europe. The band of precipitation that is associated with the warm front is often extensive. In mature extratropical cyclones, an area known as the comma head on the northwest periphery of the surface low can be a region of heavy precipitation, frequent thunderstorms, and thundersnows. Cyclones tend to move along a predictable path at a moderate rate of progress. During fall, winter, and spring, the atmosphere over continents can be cold enough through the depth of the troposphere to cause snowfall.[citation needed]

Severe weather

[edit]Squall lines, or solid bands of strong thunderstorms, can form ahead of cold fronts and lee troughs due to the presence of significant atmospheric moisture and strong upper level divergence, leading to hail and high winds.[49] When significant directional wind shear exists in the atmosphere ahead of a cold front in the presence of a strong upper-level jet stream, tornado formation is possible.[50] Although tornadoes can form anywhere on Earth, the greatest number occur in the Great Plains in the United States, because downsloped winds off the north–south oriented Rocky Mountains, which can form a dry line, aid their development at any strength.[citation needed]

Explosive development of extratropical cyclones can be sudden. The storm known in Great Britain and Ireland as the "Great Storm of 1987" deepened to 953 millibars (28.14 inHg) with a highest recorded wind of 220 km/h (140 mph), resulting in the loss of 19 lives, 15 million trees, widespread damage to homes and an estimated economic cost of £1.2 billion (US$2.3 billion).[51]

Although most tropical cyclones that become extratropical quickly dissipate or are absorbed by another weather system, they can still retain winds of hurricane or gale force. In 1954, Hurricane Hazel became extratropical over North Carolina as a strong Category 3 storm. The Columbus Day Storm of 1962, which evolved from the remains of Typhoon Freda, caused heavy damage in Oregon and Washington, with widespread damage equivalent to at least a Category 3. In 2005, Hurricane Wilma began to lose tropical characteristics while still sporting Category 3-force winds (and became fully extratropical as a Category 1 storm).[52]

In summer, extratropical cyclones are generally weak, but some of the systems can cause significant floods overland because of torrential rainfall. The July 2016 North China cyclone never brought gale-force sustained winds, but it caused devastating floods in mainland China, resulting in at least 184 deaths and ¥33.19 billion (US$4.96 billion) of damage.[53][54]

An emerging topic is the co-occurrence of wind and precipitation extremes, so-called compound extreme events, induced by extratropical cyclones. Such compound events account for 3–5% of the total number of cyclones.[4]

Climate and general circulation

[edit]In the classic analysis by Edward Lorenz (the Lorenz energy cycle),[55] extratropical cyclones (so-called atmospheric transients) acts as a mechanism in converting potential energy that is created by pole to equator temperature gradients to eddy kinetic energy. In the process, the pole-equator temperature gradient is reduced (i.e. energy is transported poleward to warm up the higher latitudes).[citation needed]

The existence of such transients are also closely related to the formation of the Icelandic and Aleutian Low — the two most prominent general circulation features in the mid- to sub-polar northern latitudes.[56] The two lows are formed by both the transport of kinetic energy and the latent heating (the energy released when water phase changed from vapor to liquid during precipitation) from the mid- latitude cyclones.[citation needed]

Historic storms

[edit]

The most intense extratropical cyclone on record was a cyclone in the Southern Ocean in October 2022. An analysis by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts estimated a pressure of 900.7 mbar (26.60 inHg) and a subsequent analysis published in Geophysical Research Letters estimated a pressure of 899.91 mbar (26.574 inHg).[57][58] The same Geophysical Research Letters article notes at least five other extratropical cyclones in the Southern Ocean with a pressure under 915 mbar (27.0 inHg).[58]

In the North Atlantic Ocean, the most intense extratropical cyclone was the Braer Storm, which reached a pressure of 914 mbar (27.0 inHg) in early January 1993.[59] Before the Braer Storm, an extratropical cyclone near Greenland in December 1986 reached a minimum pressure of at least 916 mbar (27.0 inHg). The West German Meteorological Service marked a pressure of 915 mbar (27.0 inHg), with the possibility of a pressure between 912–913 mbar (26.9–27.0 inHg), lower than the Braer Storm.[60]

The most intense extratropical cyclone across the North Pacific Ocean occurred in November 2014, when a cyclone partially related to Typhoon Nuri reached a record low pressure of 920 mbar (27 inHg).[61][62] In October 2021, the most intense Pacific Northwest windstorm occurred off the coast of Oregon, peaking with a pressure of 942 mbar (27.8 inHg).[63] One of the strongest nor'easters occurred in January 2018, in which a cyclone reached a pressure of 950 mbar (28 inHg).[64]

Extratropical cyclones have been responsible for some of the most damaging floods in European history. The Great storm of 1703 killed over 8,000 people and the North Sea flood of 1953 killed over 2,500 and destroyed 3,000 houses.[65][66] In 2002, floods in Europe caused by two genoa lows caused $27.115 billion in damages and 232 fatalities, the most damaging flood in European since at least 1985.[67][68] In late December 1999, Cyclones Lothar and Martin caused 140 deaths combined and over $23 billion in damages in Central Europe, the costliest European windstorms in history.[69][70]

In October 2012, Hurricane Sandy transitioned into an extratropical cyclone off the coast of the Northeastern United States. The storm killed over 100 people and caused $65 billion in damages, the second costliest tropical cyclone at the time.[71][72] Other extratropical cyclones have been related to major tornado outbreaks. The tornado outbreaks of April 1965, April 1974 and April 2011 were all large, violent, and deadly tornado outbreaks related to extratropical cyclones.[73][74][75][76] Similarly, winter storms in March 1888, November 1950 and March 1993 were responsible for over 300 deaths each.[77][78][79]

In December 1960 a nor'easter caused at least 286 deaths in the Northeastern United States, one of the deadliest nor'easters on record.[80] 62 years later in 2022, a winter storm caused $8.5 billion in damages and 106 deaths across the United States and Canada.[81]

In September 1954, the extratropical remnants of Typhoon Marie caused the Tōya Maru to run aground and capsize in the Tsugaru Strait. 1,159 out of the 1,309 on board were killed, making it one of the deadliest typhoons in Japanese history.[82][83] In July 2016, a cyclone in Northern China left 184 dead, 130 missing, and caused over $4.96 billion in damages.[84][85]

For older extratropical storms occurring before the 20th century, new paleotempestological methods can be used to assess their intensity. Cross-referencing environmental and historical records in Western Europe has highlighted the intense storms of 1351-1352, 1469, 1645, 1711 and 1751, which caused severe damage and long-lasting flooding along much of Europe's coastline.[86]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b DeCaria (2005-12-07). "ESCI 241 – Meteorology; Lesson 16 – Extratropical Cyclones". Department of Earth Sciences, Millersville University. Archived from the original on 2008-02-08. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ Robert Hart; Jenni Evans (2003). "Synoptic Composites of the Extratropical Transition Lifecycle of North Atlantic TCs as Defined Within Cyclone Phase Space" (PDF). American Meteorological Society. Retrieved 2006-10-03.

- ^ Ryan N. Maue (2004-12-07). "Chapter 3: Cyclone Paradigms and Extratropical Transition Conceptualizations". Archived from the original on 2008-05-10. Retrieved 2008-06-15.

- ^ a b Messmer, Martina; Ian Simmonds (2021). "Global analysis of cyclone-induced compound precipitation and wind extreme events". Weather and Climate Extremes. 32 100324. Bibcode:2021WCE....3200324M. doi:10.1016/j.wace.2021.100324. ISSN 2212-0947.

- ^ Ian Simmonds; Kevin Keay (February 2000). "Variability of Southern Hemisphere Extratropical Cyclone Behavior, 1958–97". Journal of Climate. 13 (3): 550–561. Bibcode:2000JCli...13..550S. doi:10.1175/1520-0442(2000)013<0550:VOSHEC>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0442.

- ^ S. K. Gulev; O. Zolina; S. Grigoriev (2001). "Winter Storms in the Northern Hemisphere (1958–1999)". Climate Dynamics. 17 (10): 795–809. Bibcode:2001ClDy...17..795G. doi:10.1007/s003820000145. S2CID 129364159.

- ^ Carlyle H. Wash; Stacey H. Heikkinen; Chi-Sann Liou; Wendell A. Nuss (February 1990). "A Rapid Cyclogenesis Event during GALE IOP 9". Monthly Weather Review. 118 (2): 234–257. Bibcode:1990MWRv..118..375W. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1990)118<0375:ARCEDG>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0493.

- ^ Jack Williams (2005-05-20). "Bomb cyclones ravage northwestern Atlantic". USA Today. Retrieved 2006-10-04.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology (June 2000). "Bomb". American Meteorological Society. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ Frederick Sanders; John R. Gyakum (October 1980). "Synoptic-Dynamic Climatology of the "Bomb"". Monthly Weather Review. 108 (10): 1589. Bibcode:1980MWRv..108.1589S. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1980)108<1589:SDCOT>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Joseph M. Sienkiewicz; Joan M. Von Ahn; G. M. McFadden (2005-07-18). "Hurricane Force Extratropical Cyclones" (PDF). American Meteorology Society. Retrieved 2006-10-21.

- ^ "Great weather events — A record-breaking Atlantic weather system". U.K. Met Office. Archived from the original on 2008-07-07. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ^ Brümmer B.; Thiemann S.; Kirchgässner A. (2000). "A cyclone statistics for the Arctic based on European Centre re-analysis data (Abstract)". Meteorology and Atmospheric Physics. 75 (3–4): 233–250. Bibcode:2000MAP....75..233B. doi:10.1007/s007030070006. ISSN 0177-7971. S2CID 119849630. Retrieved 2006-10-04.

- ^ a b Robert E. Hart; Jenni L. Evans (February 2001). "A climatology of extratropical transition of tropical cyclones in the North Atlantic". Journal of Climate. 14 (4): 546–564. Bibcode:2001JCli...14..546H. doi:10.1175/1520-0442(2001)014<0546:ACOTET>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ "Glossary of Hurricane Terms". Canadian Hurricane Center. 2003-07-10. Archived from the original on 2006-10-02. Retrieved 2006-10-04.

- ^ National Hurricane Center (2011-07-11). "Glossary of NHC Terms: P". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2011-07-23.

- ^ a b Jenni L. Evans; Robert E. Hart (May 2003). "Objective indicators of the life cycle evolution of extratropical transition for Atlantic tropical cyclones". Monthly Weather Review. 131 (5): 909–925. Bibcode:2003MWRv..131..909E. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(2003)131<0909:OIOTLC>2.0.CO;2. S2CID 3744671.

- ^ Robert E. Hart (April 2003). "A Cyclone Phase Space Derived from Thermal Wind and Thermal Asymmetry". Monthly Weather Review. 131 (4): 585–616. Bibcode:2003MWRv..131..585H. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(2003)131<0585:ACPSDF>2.0.CO;2. S2CID 3753455.

- ^ a b Robert E. Hart; Clark Evans; Jenni L. Evans (February 2006). "Synoptic composites of the extratropical transition lifecycle of North Atlantic tropical cyclones: Factors determining post-transition evolution". Monthly Weather Review. 134 (2): 553–578. Bibcode:2006MWRv..134..553H. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.488.5251. doi:10.1175/MWR3082.1. S2CID 3742254.

- ^ Mark P. Guishard; Jenni L. Evans; Robert E. Hart (July 2009). "Atlantic Subtropical Storms. Part II: Climatology". Journal of Climate. 22 (13): 3574–3594. Bibcode:2009JCli...22.3574G. doi:10.1175/2008JCLI2346.1. S2CID 51435473.

- ^ Jenni L. Evans; Mark P. Guishard (July 2009). "Atlantic Subtropical Storms. Part I: Diagnostic Criteria and Composite Analysis". Monthly Weather Review. 137 (7): 2065–2080. Bibcode:2009MWRv..137.2065E. doi:10.1175/2009MWR2468.1.

- ^ David M. Roth (2002-02-15). "A Fifty year History of Subtropical Cyclones" (PDF). Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved 2006-10-04.

- ^ Michelle L. Stewart; M. A. Bourassa (2006-04-25). "Cyclogenesis and Tropical Transition in decaying frontal zones". Retrieved 2006-10-24.

- ^ Christopher A. Davis; Lance F. Bosart (November 2004). "The TT Problem — Forecasting the Tropical Transition of Cyclones". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 85 (11): 1657–1662. Bibcode:2004BAMS...85.1657D. doi:10.1175/BAMS-85-11-1657. S2CID 122903747.

- ^ Velden, C.; et al. (Aug 2006). "The Dvorak Tropical Cyclone Intensity Estimation Technique: A Satellite-Based Method that Has Endured for over 30 Years" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 87 (9): 1195–1210. Bibcode:2006BAMS...87.1195V. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.669.3855. doi:10.1175/BAMS-87-9-1195. S2CID 15193271. Retrieved 2008-11-07.

- ^ Lander, Mark A. (2004). "Monsoon depressions, monsoon gyres, midget tropical cyclones, TUTT cells, and high intensity after recurvature: Lessons learned from the use of Dvorak's techniques in the world's most prolific tropical-cyclone basin" (PDF). 26th Conference on Hurricanes and Tropical Meteorology. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- ^ "JTWC TN 97/002 Page 1". Archived from the original on 2012-02-08.

- ^ a b "JTWC TN 97/002 Page 8". Archived from the original on 2012-02-08.

- ^ a b "JTWC TN 97/002 Page 2". Archived from the original on 2012-02-08.

- ^ "WW2010 - Pressure Gradient Force". University of Illinois. 1999-09-02. Retrieved 2006-10-11.

- ^ "The Atmosphere in Motion" (PDF). University of Aberdeen. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-09-07. Retrieved 2011-09-11.

- ^ "The Atmosphere in motion: Pressure & mass" (PDF). Ohio State University. 2006-04-26. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-09-05. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ "What is a TROWAL?". St. Louis University. 2003-08-04. Archived from the original on 2006-09-16. Retrieved 2006-11-02.

- ^ Andrea Lang (2006-04-20). "Mid-Latitude Cyclones: Vertical Structure". University of Wisconsin-Madison Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences. Archived from the original on 2006-09-03. Retrieved 2006-10-03.

- ^ Robert Hart (2003-02-18). "Cyclone Phase Analysis and Forecast: Help Page". Florida State University Department of Meteorology. Retrieved 2006-10-03.

- ^ Robert Harthi (2006-10-04). "Cyclone phase evolution: Analyses & Forecasts". Florida State University Department of Meteorology. Retrieved 2006-10-03.

- ^ David M. Roth (2005-12-15). "Unified Surface Analysis Manual" (PDF). Hydrometeorological Prediction Center (NOAA). Retrieved 2006-10-11.

- ^ Shaye Johnson (2001-09-25). "The Norwegian Cyclone Model" (PDF). University of Oklahoma, School of Meteorology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-09-01. Retrieved 2006-10-11.

- ^ a b David M. Schultz; Heini Werli (2001-01-05). "Determining Midlatitude Cyclone Structure and Evolution from the Upper-Level Flow". Cooperative Institute for Mesoscale Meteorological Studies. Retrieved 2006-10-09.

- ^ a b Ryan N. Maue (2006-04-25). "Warm seclusion cyclone climatology". American Meteorological Society Conference. Retrieved 2006-10-06.

- ^ Jeff Masters (2006-02-14). "Blizzicanes". JeffMasters' Blog on Wunderground.Com. Retrieved 2006-11-01.

- ^ Richard J. Pasch; Eric S. Blake (February 8, 2006). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Maria (PDF) (Report). Miami Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ Fontaine, Andie Sophia (September 1, 2014). "Stormy Weather Is Hurricane Cristobal Petering Out". The Reykjavík Grapevine. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology (June 2000). "Zonal Flow". American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2007-03-13. Retrieved 2006-10-03.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology (June 2000). "Meridional Flow". American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2006-10-26. Retrieved 2006-10-03.

- ^ Anthony R. Lupo; Phillip J. Smith (February 1998). "The Interactions between a Midlatitude Blocking Anticyclone and Synoptic-Scale Cyclones That Occurred during the Summer Season". Monthly Weather Review. 126 (2): 502–515. Bibcode:1998MWRv..126..502L. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1998)126<0502:TIBAMB>2.0.CO;2. hdl:10355/2398. ISSN 1520-0493.

- ^ B. Ziv; P. Alpert (December 2003). "Theoretical and Applied Climatology — Rotation of mid-latitude binary cyclones: a potential vorticity approach". Theoretical and Applied Climatology. 76 (3–4): 189–202. Bibcode:2003ThApC..76..189Z. doi:10.1007/s00704-003-0011-x. ISSN 0177-798X. S2CID 54982309.

- ^ Joan Von Ahn; Joe Sienkiewicz; Greggory McFadden (April 2005). "Mariners Weather Log, Vol 49, No. 1". Voluntary Observing Ship Program. Retrieved 2006-10-04.

- ^ "WW2010 - Squall Lines". University of Illinois. 1999-09-02. Retrieved 2006-10-21.

- ^ "Tornadoes: Nature's Most Violent Storms". National Severe Storms Laboratory (NOAA). 2002-03-13. Archived from the original on 2006-10-26. Retrieved 2006-10-21.

- ^ "The Great Storm of 1987". Met Office. Archived from the original on 2007-04-02. Retrieved 2006-10-30.

- ^ Richard J. Pasch; Eric S. Blake; Hugh D. Cobb III & David P Roberts (2006-01-12). "Tropical Cyclone Report — Hurricane Wilma" (PDF). National Hurricane Center (NOAA). Retrieved 2006-10-11.

- ^ "华北东北黄淮强降雨致289人死亡失踪" (in Chinese). Ministry of Civil Affairs. July 25, 2016. Archived from the original on July 25, 2016. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ^ "西南部分地区洪涝灾害致80余万人受灾" (in Chinese). Ministry of Civil Affairs. July 25, 2016. Archived from the original on July 25, 2016. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ^ Holton, James R. 1992 An introduction to dynamic meteorology / James R. Holton Academic Press, San Diego : https://www.loc.gov/catdir/toc/els032/91040568.html

- ^ Linear Stationary Wave Simulations of the Time-Mean Climatological Flow, Paul J. Valdes, Brian J. Hoskins, Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 1989 46:16, 2509–2527

- ^ Hewson, Tim; Day, Jonathan; Hersbach, Hans (January 2023). "The deepest extratropical cyclone of modern times?". Newsletter. European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- ^ a b Lin, Peiyi; Zhong, Rui; Yang, Qinghua; Clem, Kyle R.; Chen, Dake (28 July 2023). "A Record-Breaking Cyclone Over the Southern Ocean in 2022". Geophysical Research Letters. 50 (14). Bibcode:2023GeoRL..5004012L. doi:10.1029/2023GL104012.

- ^ Odell, Luke; Knippertz, Peter; Pickering, Steven; Parkes, Ben; Roberts, Alexander (April 2013). "The Braer storm revisited" (PDF). Weather. 68 (4): 105–111. Bibcode:2013Wthr...68..105O. doi:10.1002/wea.2097. S2CID 120025537. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- ^ Burt, S. D. (February 1987). "A New North Atlantic Low Pressure Record" (PDF). Weather. 42 (2): 53–56. Bibcode:1987Wthr...42...53B. doi:10.1002/j.1477-8696.1987.tb06919.x. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ^ "Marine Weather Warning for GMDSS Metarea XI 2014-11-08T06:00:00Z". Japan Meteorological Agency. 8 November 2014. Archived from the original on 8 November 2014. Retrieved 12 November 2023.

- ^ Wiltgen, Nick; Erdman, Jonatha (9 November 2014). "Bering Sea Superstorm Among the Strongest Extratropical Cyclones on Record". The Weather Channel. Retrieved 12 November 2023.

- ^ Zaffino, Matt (27 October 2021). "Bomb cyclone: What it is, where the term came from and why it's not a hurricane". KGW. Retrieved 12 November 2023.

- ^ Kong (4 January 2018). "STORM SUMMARY NUMBER 5 FOR EASTERN U.S. WINTER STORM". Wea. Archived from the original on 5 January 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ "Freak storm dissipates over England". HISTORY. 13 November 2009. Retrieved 6 December 2023.

- ^ "The flood of 1953 - Rescue and consequences". Deltawerken. Archived from the original on 6 May 2019. Retrieved 6 December 2023.

- ^ "System Explanation of Floods in Central Europe". Natural Disaster Networking Platform. Archived from the original on 4 March 2008. Retrieved 6 December 2023.

- ^ Kundzewicz, Zbigniew W.; Pińskwar, Iwona; Brakenridge, G. Robert (January 2013). "Large floods in Europe, 1985–2009" (PDF). Hydrological Sciences Journal. 58 (1). Hydrological Sciences Journal: 1–7. Bibcode:2013HydSJ..58....1K. doi:10.1080/02626667.2012.745082. Retrieved 6 December 2023.

- ^ Tatge, Yörn (9 December 2009). "Looking Back, Looking Forward: Anatol, Lothar and Martin Ten Years Later". Verisk. Retrieved 6 December 2023.

- ^ "Christmas 20 years ago: Storms Lothar and Martin wreak havoc across Europe". Swiss Re. Retrieved 6 December 2023.

- ^ Blake, Eric S; Kimberlain, Todd B; Berg, Robert J; Cangialosi, John P; Beven II, John L (12 February 2013). Hurricane Sandy: October 22 – 29, 2012 (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ Costliest U.S. tropical cyclones tables updated (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. 26 January 2018. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ "Storm Events Database". National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ Mike Soltow (25 April 2011). "Storm Summary Number 11 For Central U.S. Heavy Rain Event". Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ Corfidi, Stephen F.; Levit, Jason J.; Weiss, Steven J. "The Super Outbreak: Outbreak of the Century" (PDF). Storm Prediction Center. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ "April 11th 1965 Palm Sunday Tornado Outbreak". National Weather Service. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ "On Mar 12 in weather history..." National Weather Service. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 20 January 2024.

- ^ "NOAA's Top U.S. Weather, Water and Climate Events of the 20th Century". National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 15 August 2000. Retrieved 20 January 2024.

- ^ "Superstorm of 1993 "Storm of the Century"". National Weather Service. Retrieved 20 January 2024.

- ^ "East Thaws Out From Freeze; 286 Left Dead". Newspapers.com. Pasadena Independent. 15 December 1960. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- ^ "Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters". National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- ^ "洞爺丸台風 昭和29年(1954年) 9月24日~9月27日". www.data.jma.go.jp (in Japanese). Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- ^ 第2版,日本大百科全書(ニッポニカ) , 百科事典マイペディア,デジタル大辞泉プラス,世界大百科事典 . "洞爺丸台風(とうやまるたいふう)とは". コトバンク (in Japanese). Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- ^ "华北东北黄淮强降雨致289人死亡失踪" (in Chinese). Ministry of Civil Affairs. 23 July 2016. Archived from the original on 25 July 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- ^ "西南部分地区洪涝灾害致80余万人受灾" (in Chinese). Ministry of Civil Affairs. 25 July 2016. Archived from the original on 25 July 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- ^ Pouzet, Pierre; Maanan, Mohamed (2020-07-21). "Climatological influences on major storm events during the last millennium along the Atlantic coast of France". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 12059. Bibcode:2020NatSR..1012059P. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-69069-w. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 7374694. PMID 32694711.

External links

[edit] Media related to Extratropical cyclones at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Extratropical cyclones at Wikimedia Commons

Extratropical cyclone

View on GrokipediaTerminology

Definitions and distinctions

An extratropical cyclone, also known as a mid-latitude cyclone, is a large-scale low-pressure weather system that forms primarily in the extratropical regions, typically between 30° and 60° latitude in either hemisphere. These systems derive their primary energy from baroclinic instability, arising from horizontal temperature contrasts between warm and cold air masses, which drives the release of potential energy through atmospheric motions. Unlike smaller-scale disturbances, extratropical cyclones exhibit synoptic-scale circulation, often spanning hundreds to thousands of kilometers, and are associated with the development of fronts—boundaries separating distinct air masses—that lead to organized bands of clouds, precipitation, and wind.[1][8] The key distinctions between extratropical cyclones and tropical cyclones lie in their formation environments, energy sources, and structural features. Tropical cyclones originate over warm tropical or subtropical waters (sea surface temperatures of at least 26.5°C), where they gain energy from the latent heat released by condensing water vapor in deep convective clouds, resulting in a warm-core structure throughout the troposphere with no associated fronts. In contrast, extratropical cyclones form in cooler mid-latitude environments, often over land or ocean, and feature a cold core in the lower troposphere due to the influx of colder air; their energy comes from temperature gradients rather than ocean heat flux, leading to frontal systems (warm, cold, and occluded fronts) that produce asymmetric weather patterns. Additionally, tropical cyclones have a compact, nearly circular structure with maximum sustained winds close to the center, whereas extratropical cyclones are larger, more elongated, with peak winds occurring farther from the center in the comma-shaped cloud patterns visible on satellite imagery.[9][3][10] Extratropical cyclones also differ from subtropical cyclones, which represent a transitional or hybrid category. Subtropical cyclones exhibit a mix of tropical and extratropical traits: they lack well-defined fronts but have a larger, often cloud-free eye-like center and maximum winds displaced 100 miles or more from the center, with energy drawn partially from latent heat and partially from baroclinic processes; their core may be warm at upper levels but cooler aloft compared to fully tropical systems. In essence, extratropical cyclones are fully baroclinic and frontally organized, while subtropical ones bridge the gap toward tropical characteristics without achieving the symmetric, convection-dominated intensity of hurricanes.[9] A related concept is the post-tropical cyclone, which refers to a former tropical cyclone that has lost its tropical characteristics—such as organized deep convection and warm-core structure—often through extratropical transition (ET), where it interacts with mid-latitude baroclinicity and cooler waters. During ET, the system acquires frontal boundaries and a cold core, effectively becoming an extratropical cyclone, though it may retain significant wind and rain hazards; if the circulation dissipates without redeveloping, it is classified as a remnant low. This distinction highlights how tropical systems can evolve into extratropical ones, blurring boundaries in transitional cases but maintaining clear energetic and structural differences in their mature forms.[1][8]Nomenclature and classifications

Extratropical cyclones are synoptic-scale low-pressure systems that develop poleward of the subtropics, typically between 30° and 60° latitude in either hemisphere.[3] They are distinguished from tropical cyclones by their association with frontal boundaries and baroclinic instability rather than warm-core convection.[11] Common synonyms include mid-latitude cyclones, reflecting their prevalence in middle latitudes; wave cyclones, due to their initial development as waves along the polar front; and frontal cyclones, emphasizing the role of fronts in their structure.[11] Other terms such as temperate cyclones or simply "lows" are used interchangeably in meteorological contexts to denote these systems.[12] Nomenclature also encompasses transitional states, such as post-tropical cyclones, which refer to systems that have lost tropical characteristics but retain significant intensity while adopting extratropical features like asymmetry and frontal structure.[3] Regional naming conventions further specify types based on formation areas or tracks; for example, nor'easters (or northeasters) describe intense storms along the U.S. East Coast that draw moisture from the Atlantic, while Alberta clippers are fast-moving systems originating near the Rocky Mountains in Canada, and Colorado lows form in the lee of the Rockies.[11] These names highlight geographic influences, such as lee-side lows that develop in the wake of mountain ranges due to topographic forcing.[11] Classifications of extratropical cyclones vary by criteria, including dynamical forcing, structural evolution, and intensity. A seminal dynamical classification, proposed by Petterssen and Smebye (1971), divides cyclogenesis into Type A and Type B based on the interaction between upper-level troughs and surface baroclinicity.[12] Type A cyclones develop primarily from upper-level divergence ahead of a short-wave trough, with the surface low forming beneath it in a region of strong baroclinicity; these are common in the North Pacific and Atlantic.[12] Type B cyclones arise from the deformation of a preexisting surface frontal zone by an approaching upper trough, leading to enhanced vorticity through confluence; they constitute about 38% of North Atlantic cyclones.[12] A Type C category, introduced later, encompasses mixed or weakly forced cases where neither mechanism dominates.[13] Structural classifications often reference idealized models, such as the Norwegian cyclone model, which categorizes cyclones by frontal configurations (cold, warm, and occluded fronts) during their lifecycle stages: incipient (wave formation), mature (frontal development), and occluded (frontal occlusion).[11] An alternative, the Shapiro-Keyser model, classifies cyclones by the bending of the warm front equatorward and the development of a bent-back front, particularly relevant for intense North Atlantic storms.[12] Intensity-based schemes include "bomb cyclones," defined by Sanders and Gyakum (1980) as extratropical systems undergoing explosive deepening, with a central pressure decrease of at least 24 hPa in 24 hours at 60° latitude (adjusted latitudinally as 24 (sin φ / sin 60°) hPa, where φ is latitude).[14] These rapid intensifications often occur over ocean basins and are associated with severe weather.[14] Additional classifications focus on location or impacts, such as European cyclone tracks divided into Mediterranean, Atlantic, and Scandinavian pathways based on reanalysis data, or by precipitation patterns into types with warm-sector, cold-frontal, or occluded rainbands.[15] These schemes aid in climate studies by linking cyclone types to regional weather extremes and long-term trends.[12]Formation

Cyclogenesis processes

Extratropical cyclogenesis refers to the initiation and intensification of low-pressure systems in middle and high latitudes, driven primarily by the release of available potential energy through atmospheric instabilities. These processes typically occur along zones of strong baroclinicity, where horizontal temperature gradients create vertical wind shear conducive to disturbance growth.[4] The fundamental mechanism underlying most extratropical cyclogenesis is baroclinic instability, in which small-scale perturbations amplify by extracting energy from the mean zonal flow's potential energy reservoir, generated by differential solar heating between the equator and poles. This meridional temperature gradient maintains a strong thermal wind, enabling the conversion of potential energy into eddy kinetic energy via slanting convection and ageostrophic circulations.[12][16] Baroclinic instability explains the formation of synoptic-scale waves that evolve into cyclones, with growth rates peaking for wavelengths around 3,000–4,500 km, aligning with observed midlatitude storm scales.[17] Theoretical foundations for baroclinic instability were established in seminal quasi-geostrophic models. The Eady model (1949) idealizes a uniform zonal flow with constant vertical shear between rigid boundaries, demonstrating baroclinic instability for realistic midlatitude conditions (large Richardson numbers), leading to growing modes that tilt against the shear vector to facilitate energy transfer.[18] Complementing this, the Charney model (1947) incorporates a realistic tropospheric stratification with a resting interior and rigid lower boundary, yielding similar growth rates but emphasizing the role of the planetary vorticity gradient (beta effect) in selecting eastward-propagating waves.[19] These models predict e-folding growth times of 1–3 days for typical midlatitude conditions, consistent with observed cyclone development.[4] Practical cyclogenesis often begins with a weak disturbance along a frontal boundary or within a barotropic region, where confluence and diffluence enhance frontogenesis—the sharpening of temperature contrasts through deformation fields. Upper-level positive vorticity advection from jet stream dynamics induces surface convergence and ascent, lowering central pressure and amplifying the initial low.[4] In moist environments, latent heat release from ascending warm, moist air further intensifies the system by increasing buoyancy and reducing static stability, contributing up to 20–50% of the total deepening in some cases.[20] Additional forcing includes interactions with orography or upstream troughs, which can trigger lee cyclogenesis by generating localized vorticity anomalies. Explosive cyclogenesis, or "bomb" development, occurs when these processes align rapidly, with pressure falls exceeding 1 hPa/hour, often linked to enhanced baroclinicity over warm ocean currents.[21] Overall, these interconnected mechanisms ensure that extratropical cyclones efficiently transport heat and momentum poleward, maintaining the general circulation.[12]Extratropical transition

Extratropical transition (ET) is the evolutionary process by which a tropical cyclone loses its primarily symmetric warm-core structure and acquires the characteristics of a baroclinic extratropical cyclone, typically as it moves poleward into midlatitudes. This transformation occurs when the storm encounters environmental conditions such as reduced sea surface temperatures (SSTs) below 26°C, increased vertical wind shear exceeding 10 m/s, and a baroclinic atmosphere with strong horizontal temperature gradients.[22] During ET, the cyclone's energy source shifts from latent heat release in deep convection to baroclinic instability, leading to the development of frontal boundaries and an asymmetric thermal structure. The process is generally divided into two phases. In the first phase, the tropical cyclone becomes embedded within a baroclinic zone, where the low-level center of the storm becomes displaced from the upper-level center due to wind shear, resulting in initial weakening as the symmetric convection diminishes. This phase often involves the formation of a nascent cold front ahead of the cyclone and a warm front to its east, marking the onset of extratropical features. The second phase involves re-intensification, where the cyclone interacts with the midlatitude jet stream, potentially leading to rapid deepening as an extratropical low, with maximum winds shifting to the cold sector. Observational studies indicate that this re-intensification can produce winds comparable to or exceeding the tropical phase, particularly in the North Atlantic and western North Pacific basins. ET outcomes vary based on environmental factors and cyclone intensity. Stronger tropical cyclones at the onset of transition are more likely to complete ET and re-intensify, while weaker systems may dissipate entirely. In the North Atlantic, approximately 35-50% of tropical cyclones undergo ET annually, often contributing to major midlatitude storms. The transition can also induce downstream impacts, such as Rossby wave amplification and altered predictability in the midlatitude waveguide, sometimes leading to high-impact weather events like European windstorms. For instance, Hurricane Sandy in 2012 underwent ET off the U.S. East Coast, resulting in a hybrid storm that caused extensive coastal flooding and over $65 billion in damages. Predicting ET remains challenging due to the complex interactions between the tropical cyclone and midlatitude dynamics, with forecast errors often propagating downstream. Numerical models like the ECMWF Integrated Forecasting System have improved ET simulations by better resolving baroclinic processes, but uncertainties persist in moisture distribution and jet interactions. Research emphasizes the role of tropical cyclone moisture in fueling post-ET precipitation, which can exceed 200 mm in affected regions, highlighting ET's broader hydrological impacts.Structure

Surface analysis

Surface analysis of extratropical cyclones typically depicts a closed low-pressure center surrounded by concentric isobars that indicate counterclockwise circulation in the Northern Hemisphere, with pressure gradients strongest near the center where winds are most intense.[11] The central sea-level pressure often falls below 990 hPa in developing systems, driving geostrophic winds that veer with distance from the low, transitioning from southerly in the warm sector to northerly behind the cold front.[23] A hallmark of the surface structure is the presence of frontal boundaries, which mark sharp temperature contrasts and serve as foci for weather activity. The warm front extends from the low-pressure center eastward or northeastward, sloping gently upward over cooler air, and is characterized by rising warm air leading to stratiform precipitation and cirrus clouds ahead of the front.[24] Trailing the warm front is the cold front, which stretches southward or southwestward from the center, featuring a steeper slope and more intense lifting of warm air, often producing cumuliform clouds, gusty winds, and heavy, showery precipitation along its length.[25] As the cyclone matures, an occluded front forms where the cold front overtakes the warm front, wrapping westward around the low center and lifting the warm sector aloft; this occlusion is evident on surface maps as a merging of frontal symbols, with the lowest pressure often shifting toward the triple point where the three fronts intersect.[11] The overall pattern contrasts with high-pressure ridges to the north or west, creating a wavy jet stream influence at upper levels that reinforces the surface low.[10] Weather features on the surface chart include widespread cloud cover and precipitation belts aligned with the fronts: light to moderate rain in the warm frontal zone, potentially severe squalls along the cold front, and drier conditions in the post-frontal northerly flow.[24] Surface winds generally follow the isobars with minor friction-induced deviations, strongest in the right entrance region relative to the storm's motion, and temperatures drop markedly across the cold front while rising ahead of the warm front.[23] This configuration underscores the baroclinic nature of extratropical cyclones, where horizontal temperature gradients at the surface fuel the system's development.Vertical structure

The vertical structure of an extratropical cyclone features a characteristic westward tilt with height in the Northern Hemisphere, where the low-pressure center deepens and shifts northwestward aloft, with the upper-level trough positioned west of the surface low. This tilt arises from the displacement of cold air masses behind the cold front, which extend upward into the mid-troposphere, creating an upper low while warm air advection ahead thickens the atmospheric column.[11][26] The configuration promotes baroclinic instability, as the horizontal temperature gradient tilts into a vertical one, driving differential vertical motions.[26] Upper-level dynamics are dominated by a jet stream trough, where positive vorticity advection at around 500 hPa induces divergence aloft, exceeding surface convergence to intensify the cyclone through enhanced ascent.[27][11] Jet streaks within the jet amplify this divergence, particularly in the left exit region for Northern Hemisphere systems, fostering widespread upward motion and cloud formation.[26] In mature cyclones, a potential vorticity (PV) tower often develops, vertically aligning surface warm anomalies, low-level positive PV anomalies (0.5–2 PVU), and upper-level PV disturbances (1–4 PVU), with the dynamical tropopause depressed to approximately 500 hPa in intense systems compared to around 300 hPa in weaker ones.[28][29] Surface potential temperature anomalies reach about 5 K, up to 6 K in strong cyclones, reflecting pronounced baroclinicity.[28] The airstreams define much of the vertical organization, as conceptualized in isentropic analyses. The warm conveyor belt (WCB) originates at low levels southeast of the surface low, ascends isentropically over the warm front to mid-tropospheric heights, transporting moisture and heat poleward while generating stratiform precipitation and cloud bands.[30] The cold conveyor belt (CCB) flows westward and northward around the cyclone's western flank, rising more gradually in the occlusion region to contribute to post-frontal precipitation.[30] Complementing these, the dry intrusion descends from the upper troposphere behind the upper trough, subsiding to create a dry slot aloft with clear skies and subsidence warming.[30] During occlusion, the fronts wrap cyclonically, leading to a more vertically stacked structure with reduced tilt, as the upper trough aligns over the surface center, diminishing intensity.[26]Lifecycle and Models

Norwegian cyclone model

The Norwegian cyclone model, developed in the early 1920s by meteorologists at the Bergen School of Meteorology in Norway, provides a foundational conceptual framework for understanding the lifecycle and structure of extratropical cyclones.[31] Pioneered by Jacob Bjerknes in his 1919 paper "On the Structure of Moving Cyclones" and further elaborated in collaborative works such as Bjerknes and Solberg (1922), the model drew on extensive surface weather observations collected via Europe's telegraph network during and after World War I. It emphasizes the role of frontal boundaries in cyclone development, integrating surface-level frontal systems with upper-level atmospheric dynamics to explain cyclone intensification and occlusion.[31] The model outlines a progressive lifecycle typically divided into five key stages, beginning with a perturbation along a polar front—a quasi-stationary boundary separating cold polar air masses from warmer subtropical air.[32] In the initial condition, the front is depicted as a nearly straight line with minimal curvature, where geostrophic winds flow parallel but in opposite directions on either side, setting the stage for instability.[32] This stage highlights the precondition of baroclinic instability, where temperature contrasts drive potential energy for cyclone formation. During the beginning stage, an upper-level shortwave trough or low-pressure perturbation embedded in the jet stream approaches the front from the west, inducing a cyclonic wave that bulges the frontal boundary equatorward.[32] The low-pressure center forms at the wave's apex, with divergence aloft promoting surface convergence and the initial development of warm and cold sectors; light precipitation may occur along the nascent front.[32] As the system progresses to the intensification stage, the cyclone deepens rapidly due to continued upper-level support, with the warm front extending eastward and the cold front advancing southwestward, narrowing the warm sector between them.[32] Weather patterns intensify here, featuring widespread stratiform precipitation ahead of the warm front and convective showers along the cold front, often accompanied by strong winds in the comma-shaped cloud pattern visible in satellite imagery.[33] In the mature stage, the cyclone reaches peak intensity as the cold front catches up to the warm front near the surface low center, initiating occlusion where the warm air mass is progressively lifted aloft.[32] The occluded front trails behind the low, forming a characteristic "T"-shaped frontal structure, with the cyclone's isobars becoming more circular and the central pressure dropping to its minimum.[32] This phase underscores the model's insight into frontogenesis, where convergence along the fronts enhances the cyclone's vorticity and sustains severe weather, including gales and heavy rain.[31] Finally, in the dissipation stage, the occluded warm air rises into a stable, barotropic environment aloft, cutting off the upper-level support; the surface low fills, the fronts weaken, and the system merges with broader pressure patterns or dissipates over land or warmer waters.[32] Although refined by later models like the Shapiro–Keyser cyclone model to account for regional variations, the Norwegian model remains a cornerstone of synoptic meteorology for its clear depiction of frontal dynamics and cyclone evolution, influencing modern forecasting techniques. It prioritizes the interplay between surface fronts and jet stream perturbations, providing a template for analyzing mid-latitude weather systems that drive seasonal precipitation and storm tracks.[33]Shapiro–Keyser cyclone model

The Shapiro–Keyser cyclone model describes the evolution of extratropical cyclones, particularly those undergoing explosive development over oceanic regions like the North Atlantic, based on numerical simulations and observational data from satellites, surface analyses, and numerical weather prediction models. Developed in 1990 by meteorologists Melvyn A. Shapiro and Daniel Keyser, the model addresses frontal structures and life cycles that diverge from the classical Norwegian cyclone model, emphasizing processes observed in rapidly intensifying marine cyclones.[34][35] It highlights the role of upper-level jet streams and tropopause folding in cyclone dynamics, integrating these with surface frontal evolutions.[34] Key distinctions from the Norwegian model include the absence of a traditional occlusion process, where the cold front overtakes the warm sector; instead, the Shapiro–Keyser model features frontal fracture, where the cold front undergoes frontolysis (dissipation of the thermal gradient) near the low-pressure center during early intensification, preventing a full cold front from forming.[33][36] This leads to a bent-back warm front that curls westward around the cyclone center, forming a characteristic T-bone configuration with the remnant cold front, and culminates in warm-core seclusion, where a pocket of warm air from the original warm sector becomes isolated at the cyclone's core, enhancing intensification through latent heat release and reduced baroclinicity at the center.[35][37] These features make the model especially relevant for forecasting severe extratropical cyclones, as the warm seclusion often coincides with peak winds and precipitation.[38] The model delineates four primary stages in the cyclone's lifecycle, each marked by distinct frontal and dynamic changes:- Wave Stage (Phase I): An initial baroclinic wave develops along a frontal zone, with a surface low-pressure center forming between a warm front extending eastward and a nascent cold front to the south, accompanied by diffluent upper-level flow. This stage mirrors the early Norwegian model but sets the stage for deviation through westward propagation of the low relative to the steering flow.[39][35]

- Frontal Fracture Stage (Phase II): As cyclogenesis accelerates, frontolysis erodes the cold front's baroclinity near the low center due to ageostrophic circulations and deformation, causing the low to migrate poleward and westward. The cold front fractures, with its southern segment weakening and failing to advance toward the warm front, while the cyclone deepens rapidly under divergent upper-level support.[36][37]

- Bent-Back Front Stage (Phase III): The warm front bends backward (cyclonically) toward the west, forming a hook that intersects the fractured cold front in a T-bone pattern. This configuration traps warm air equatorward of the fronts, with the cyclone center embedded in a region of intense baroclinicity along the bent-back front, often associated with a folded tropopause and strong jet streak.[35][34]

- Mature Stage (Phase IV): The bent-back front fully encircles the low center, completing the warm seclusion and creating a comma-shaped cloud pattern observable in satellite imagery. The cyclone achieves maximum intensity, with the secluded warm core aloft contributing to sustained deepening, though no classical occlusion forms; dissipation follows as the system moves over land or baroclinicity wanes.[40][38]