Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Geodesy

View on Wikipedia| Geodesy |

|---|

|

| Part of a series of |

| Geophysics |

|---|

|

Geodesy or geodetics[1] is the science of measuring and representing the geometry, gravity, and spatial orientation of the Earth in temporally varying 3D. It is called planetary geodesy when studying other astronomical bodies, such as planets or circumplanetary systems.[2]

Geodynamical phenomena, including crustal motion, tides, and polar motion, can be studied by designing global and national control networks, applying space geodesy and terrestrial geodetic techniques, and relying on datums and coordinate systems.

Geodetic job titles include geodesist and geodetic surveyor.[3]

History

[edit]Geodesy began in pre-scientific antiquity, so the very word geodesy comes from the Ancient Greek word γεωδαισία or geodaisia (literally, "division of Earth").[4]

Early ideas about the figure of the Earth held the Earth to be flat and the heavens a physical dome spanning over it.[5] Two early arguments for a spherical Earth were that lunar eclipses appear to an observer as circular shadows and that Polaris appears lower and lower in the sky to a traveler headed South.[6]

Definition

[edit]Geodesy refers to the science of measuring and representing geospatial information, while geomatics encompasses practical applications of geodesy on local and regional scales, including surveying.

Geodesy originated as the science of measuring and understanding Earth's geometric shape, orientation in space, and gravitational field; it is now also applied to other astronomical bodies in the Solar System.[2]

To a large extent, Earth's shape is the result of rotation, which causes its equatorial bulge, and the competition of geological processes such as the collision of plates, as well as of volcanism, resisted by Earth's gravitational field. This applies to the solid surface, the liquid surface (dynamic sea surface topography), and Earth's atmosphere. For this reason, the study of Earth's gravitational field is called physical geodesy.

Geoid and reference ellipsoid

[edit]

The geoid essentially is the figure of Earth abstracted from its topographical features. It is an idealized equilibrium surface of seawater, the mean sea level surface in the absence of currents and air pressure variations, and continued under the continental masses. Unlike a reference ellipsoid, the geoid is irregular and too complicated to serve as the computational surface for solving geometrical problems like point positioning. The geometrical separation between the geoid and a reference ellipsoid is called geoidal undulation, and it varies globally between ±110 m based on the GRS 80 ellipsoid.

A reference ellipsoid, customarily chosen to be the same size (volume) as the geoid, is described by its semi-major axis (equatorial radius) a and flattening f. The quantity f = a − b/a, where b is the semi-minor axis (polar radius), is purely geometrical. The mechanical ellipticity of Earth (dynamical flattening, symbol J2) can be determined to high precision by observation of satellite orbit perturbations. Its relationship with geometrical flattening is indirect and depends on the internal density distribution or, in simplest terms, the degree of central concentration of mass.

The 1980 Geodetic Reference System (GRS 80), adopted at the XVII General Assembly of the International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics (IUGG), posited a 6,378,137 m semi-major axis and a 1:298.257 flattening. GRS 80 essentially constitutes the basis for geodetic positioning by the Global Positioning System (GPS) and is thus also in widespread use outside the geodetic community. Numerous systems used for mapping and charting are becoming obsolete as countries increasingly move to global, geocentric reference systems utilizing the GRS 80 reference ellipsoid.

The geoid is a "realizable" surface, meaning it can be consistently located on Earth by suitable simple measurements from physical objects like a tide gauge. The geoid can, therefore, be considered a physical ("real") surface. The reference ellipsoid, however, has many possible instantiations and is not readily realizable, so it is an abstract surface. The third primary surface of geodetic interest — the topographic surface of Earth — is also realizable.

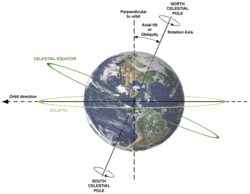

Coordinate systems in space

[edit]

The locations of points in 3D space most conveniently are described by three cartesian or rectangular coordinates, X, Y, and Z. Since the advent of satellite positioning, such coordinate systems are typically geocentric, with the Z-axis aligned to Earth's (conventional or instantaneous) rotation axis.

Before the era of satellite geodesy, the coordinate systems associated with a geodetic datum attempted to be geocentric, but with the origin differing from the geocenter by hundreds of meters due to regional deviations in the direction of the plumbline (vertical). These regional geodetic datums, such as ED 50 (European Datum 1950) or NAD 27 (North American Datum 1927), have ellipsoids associated with them that are regional "best fits" to the geoids within their areas of validity, minimizing the deflections of the vertical over these areas.

It is only because GPS satellites orbit about the geocenter that this point becomes naturally the origin of a coordinate system defined by satellite geodetic means, as the satellite positions in space themselves get computed within such a system.

Geocentric coordinate systems used in geodesy can be divided naturally into two classes:

- The inertial reference systems, where the coordinate axes retain their orientation relative to the fixed stars or, equivalently, to the rotation axes of ideal gyroscopes. The X-axis points to the vernal equinox.

- The co-rotating reference systems (also ECEF or "Earth Centred, Earth Fixed"), in which the axes are "attached" to the solid body of Earth. The X-axis lies within the Greenwich observatory's meridian plane.

The coordinate transformation between these two systems to good approximation is described by (apparent) sidereal time, which accounts for variations in Earth's axial rotation (length-of-day variations). A more accurate description also accounts for polar motion as a phenomenon closely monitored by geodesists.

Coordinate systems in the plane

[edit]

In geodetic applications like surveying and mapping, two general types of coordinate systems in the plane are in use:

- Plano-polar, with points in the plane defined by their distance, s, from a specified point along a ray having a direction α from a baseline or axis.

- Rectangular, with points defined by distances from two mutually perpendicular axes, x and y. Contrary to the mathematical convention, in geodetic practice, the x-axis points North and the y-axis East.

One can intuitively use rectangular coordinates in the plane for one's current location, in which case the x-axis will point to the local north. More formally, such coordinates can be obtained from 3D coordinates using the artifice of a map projection. It is impossible to map the curved surface of Earth onto a flat map surface without deformation. The compromise most often chosen — called a conformal projection — preserves angles and length ratios so that small circles get mapped as small circles and small squares as squares.

An example of such a projection is UTM (Universal Transverse Mercator). Within the map plane, we have rectangular coordinates x and y. In this case, the north direction used for reference is the map north, not the local north. The difference between the two is called meridian convergence.

It is easy enough to "translate" between polar and rectangular coordinates in the plane: let, as above, direction and distance be α and s respectively; then we have:

The reverse transformation is given by:

Heights

[edit]

In geodesy, point or terrain heights are "above sea level" as an irregular, physically defined surface. Height systems in use are:

Each system has its advantages and disadvantages. Both orthometric and normal heights are expressed in metres above sea level, whereas geopotential numbers are measures of potential energy (unit: m2 s−2) and not metric. The reference surface is the geoid, an equigeopotential surface approximating the mean sea level as described above. For normal heights, the reference surface is the so-called quasi-geoid, which has a few-metre separation from the geoid due to the density assumption in its continuation under the continental masses.[7]

One can relate these heights through the geoid undulation concept to ellipsoidal heights (also known as geodetic heights), representing the height of a point above the reference ellipsoid. Satellite positioning receivers typically provide ellipsoidal heights unless fitted with special conversion software based on a model of the geoid.

Geodetic datums

[edit]Because coordinates and heights of geodetic points always get obtained within a system that itself was constructed based on real-world observations, geodesists introduced the concept of a "geodetic datum" (plural datums): a physical (real-world) realization of a coordinate system used for describing point locations. This realization follows from choosing (therefore conventional) coordinate values for one or more datum points. In the case of height data, it suffices to choose one datum point — the reference benchmark, typically a tide gauge at the shore. Thus we have vertical datums, such as the NAVD 88 (North American Vertical Datum 1988), NAP (Normaal Amsterdams Peil), the Kronstadt datum, the Trieste datum, and numerous others.

In both mathematics and geodesy, a coordinate system is a "coordinate system" per ISO terminology, whereas the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS) uses the term "reference system" for the same. When coordinates are realized by choosing datum points and fixing a geodetic datum, ISO speaks of a "coordinate reference system", whereas IERS uses a "reference frame" for the same. The ISO term for a datum transformation again is a "coordinate transformation".[8]

Positioning

[edit]

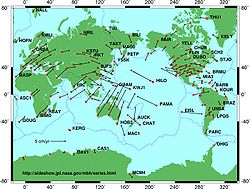

General geopositioning, or simply positioning, is the determination of the location of points on Earth, by myriad techniques. Geodetic positioning employs geodetic methods to determine a set of precise geodetic coordinates of a point on land, at sea, or in space. It may be done within a coordinate system (point positioning or absolute positioning) or relative to another point (relative positioning). One computes the position of a point in space from measurements linking terrestrial or extraterrestrial points of known location ("known points") with terrestrial ones of unknown location ("unknown points"). The computation may involve transformations between or among astronomical and terrestrial coordinate systems. Known points used in point positioning can be GNSS continuously operating reference stations or triangulation points of a higher-order network.

Traditionally, geodesists built a hierarchy of networks to allow point positioning within a country. The highest in this hierarchy were triangulation networks, densified into the networks of traverses (polygons) into which local mapping and surveying measurements, usually collected using a measuring tape, a corner prism, and the red-and-white poles, are tied.

Commonly used nowadays is GPS, except for specialized measurements (e.g., in underground or high-precision engineering). The higher-order networks are measured with static GPS, using differential measurement to determine vectors between terrestrial points. These vectors then get adjusted in a traditional network fashion. A global polyhedron of permanently operating GPS stations under the auspices of the IERS is the basis for defining a single global, geocentric reference frame that serves as the "zero-order" (global) reference to which national measurements are attached.

Real-time kinematic positioning (RTK GPS) is employed frequently in survey mapping. In that measurement technique, unknown points can get quickly tied into nearby terrestrial known points.

One purpose of point positioning is the provision of known points for mapping measurements, also known as (horizontal and vertical) control. There can be thousands of those geodetically determined points in a country, usually documented by national mapping agencies. Surveyors involved in real estate and insurance will use these to tie their local measurements.

Geodetic problems

[edit]In geometrical geodesy, there are two main problems:

- First geodetic problem (also known as direct or forward geodetic problem): given the coordinates of a point and the directional (azimuth) and distance to a second point, determine the coordinates of that second point.

- Second geodetic problem (also known as inverse or reverse geodetic problem): given the coordinates of two points, determine the azimuth and length of the (straight, curved, or geodesic) line connecting those points.

The solutions to both problems in plane geometry reduce to simple trigonometry and are valid for small areas on Earth's surface; on a sphere, solutions become significantly more complex as, for example, in the inverse problem, the azimuths differ going between the two end points along the arc of the connecting great circle.

The general solution is called the geodesic for the surface considered, and the differential equations for the geodesic are solvable numerically. On the ellipsoid of revolution, geodesics are expressible in terms of elliptic integrals, which are usually evaluated in terms of a series expansion — see, for example, Vincenty's formulae.

Observational concepts

[edit]

As defined in geodesy (and also astronomy), some basic observational concepts like angles and coordinates include (most commonly from the viewpoint of a local observer):

- Plumbline or vertical: (the line along) the direction of local gravity.

- Zenith: the (direction to the) intersection of the upwards-extending gravity vector at a point and the celestial sphere.

- Nadir: the (direction to the) antipodal point where the downward-extending gravity vector intersects the (obscured) celestial sphere.

- Celestial horizon: a plane perpendicular to the gravity vector at a point.

- Azimuth: the direction angle within the plane of the horizon, typically counted clockwise from the north (in geodesy and astronomy) or the south (in France).

- Elevation: the angular height of an object above the horizon; alternatively: zenith distance equal to 90 degrees minus elevation.

- Local topocentric coordinates: azimuth (direction angle within the plane of the horizon), elevation angle (or zenith angle), distance.

- North celestial pole: the extension of Earth's (precessing and nutating) instantaneous spin axis extended northward to intersect the celestial sphere. (Similarly for the south celestial pole.)

- Celestial equator: the (instantaneous) intersection of Earth's equatorial plane with the celestial sphere.

- Meridian plane: any plane perpendicular to the celestial equator and containing the celestial poles.

- Local meridian: the plane which contains the direction to the zenith and the celestial pole.

Measurements

[edit]

The reference surface (level) used to determine height differences and height reference systems is known as mean sea level. The traditional spirit level directly produces such (for practical purposes most useful) heights above sea level; the more economical use of GPS instruments for height determination requires precise knowledge of the figure of the geoid, as GPS only gives heights above the GRS80 reference ellipsoid. As geoid determination improves, one may expect that the use of GPS in height determination shall increase, too.

The theodolite is an instrument used to measure horizontal and vertical (relative to the local vertical) angles to target points. In addition, the tachymeter determines, electronically or electro-optically, the distance to a target and is highly automated or even robotic in operations. Widely used for the same purpose is the method of free station position.

Commonly for local detail surveys, tachymeters are employed, although the old-fashioned rectangular technique using an angle prism and steel tape is still an inexpensive alternative. As mentioned, also there are quick and relatively accurate real-time kinematic (RTK) GPS techniques. Data collected are tagged and recorded digitally for entry into Geographic Information System (GIS) databases.

Geodetic GNSS (most commonly GPS) receivers directly produce 3D coordinates in a geocentric coordinate frame. One such frame is WGS84, as well as frames by the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS). GNSS receivers have almost completely replaced terrestrial instruments for large-scale base network surveys.

To monitor the Earth's rotation irregularities and plate tectonic motions and for planet-wide geodetic surveys, methods of very-long-baseline interferometry (VLBI) measuring distances to quasars, lunar laser ranging (LLR) measuring distances to prisms on the Moon, and satellite laser ranging (SLR) measuring distances to prisms on artificial satellites, are employed.

Gravity is measured using gravimeters, of which there are two kinds. First are absolute gravimeters, based on measuring the acceleration of free fall (e.g., of a reflecting prism in a vacuum tube). They are used to establish vertical geospatial control or in the field. Second, relative gravimeters are spring-based and more common. They are used in gravity surveys over large areas — to establish the figure of the geoid over these areas. The most accurate relative gravimeters are called superconducting gravimeters, which are sensitive to one-thousandth of one-billionth of Earth-surface gravity. Twenty-some superconducting gravimeters are used worldwide in studying Earth's tides, rotation, interior, oceanic and atmospheric loading, as well as in verifying the Newtonian constant of gravitation.

In the future, gravity and altitude might become measurable using the special-relativistic concept of time dilation as gauged by optical clocks.

Units and measures on the ellipsoid

[edit]

Geographical latitude and longitude are stated in the units degree, minute of arc, and second of arc. They are angles, not metric measures, and describe the direction of the local normal to the reference ellipsoid of revolution. This direction is approximately the same as the direction of the plumbline, i.e., local gravity, which is also the normal to the geoid surface. For this reason, astronomical position determination – measuring the direction of the plumbline by astronomical means – works reasonably well when one also uses an ellipsoidal model of the figure of the Earth.

One geographical mile, defined as one minute of arc on the equator, equals 1,855.32571922 m. One nautical mile is one minute of astronomical latitude. The radius of curvature of the ellipsoid varies with latitude, being the longest at the pole and the shortest at the equator same as with the nautical mile.

A metre was originally defined as the 10-millionth part of the length from the equator to the North Pole along the meridian through Paris (the target was not quite reached in actual implementation, as it is off by 200 ppm in the current definitions). This situation means that one kilometre roughly equals (1/40,000) * 360 * 60 meridional minutes of arc, or 0.54 nautical miles. (This is not exactly so as the two units had been defined on different bases, so the international nautical mile is 1,852 m exactly, which corresponds to rounding the quotient from 1,000/0.54 m to four digits).

Temporal changes

[edit]

Various techniques are used in geodesy to study temporally changing surfaces, bodies of mass, physical fields, and dynamical systems. Points on Earth's surface change their location due to a variety of mechanisms:

- Continental plate motion, plate tectonics[9]

- The episodic motion of tectonic origin, especially close to fault lines

- Periodic effects due to tides and tidal loading[10]

- Postglacial land uplift due to isostatic adjustment

- Mass variations due to hydrological changes, including the atmosphere, cryosphere, land hydrology, and oceans

- Sub-daily polar motion[11]

- Length-of-day variability[12]

- Earth's center-of-mass (geocenter) variations[13]

- Anthropogenic movements such as reservoir construction or petroleum or water extraction

Geodynamics is the discipline that studies deformations and motions of Earth's crust and its solidity as a whole. Often the study of Earth's irregular rotation is included in the above definition. Geodynamical studies require terrestrial reference frames[14] realized by the stations belonging to the Global Geodetic Observing System (GGOS[15]).

Techniques for studying geodynamic phenomena on global scales include:

- Satellite positioning by GPS, GLONASS, Galileo, and BeiDou

- Very-long-baseline interferometry (VLBI)

- Satellite laser ranging (SLR)[16] and lunar laser ranging (LLR)

- DORIS

- Regionally and locally precise leveling

- Precise tachymeters

- Monitoring of gravity change using land, airborne, shipborne, and spaceborne gravimetry

- Satellite altimetry based on microwave and laser observations for studying the ocean surface, sea level rise, and ice cover monitoring

- Interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR) using satellite images.

Notable geodesists

[edit]See also

[edit]- Earth system science – Scientific study of the Earth's spheres and their natural integrated systems

- List of geodesists – Notable geodesists

- Geomatics engineering – Geographic data discipline

- History of geophysics

- Geodynamics – Study of dynamics of the Earth

- Planetary science – Science of planets and planetary systems

Fundamentals

- Geodesy

- Concepts and Techniques in Modern Geography

- Earth ellipsoid

- Earth's circumference

- Geodesics on an ellipsoid

- Geosciences

- History of geodesy

- Physical geodesy

- Physics

- Timeline of Earth estimates

Governmental agencies

- National mapping agencies

- U.S. National Geodetic Survey

- National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency

- Ordnance Survey

- United States Coast and Geodetic Survey

- United States Geological Survey

International organizations

- International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics (IUGG)

- International Association of Geodesy (IAG)

- International Federation of Surveyors (IFS)

- International Geodetic Student Organisation (IGSO)

Other

- Council of European Geodetic Surveyors [fr]

- EPSG Geodetic Parameter Dataset

- Meridian arc

- Surveying

References

[edit]- ^ "geodetics". Cambridge English Dictionary. Retrieved 2024-06-08.

- ^ a b Vaníček, Petr; Krakiwsky, Edward J., eds. (November 1, 1986). "Structure of Geodesy". Geodesy: The Concepts (Second ed.). Elsevier. pp. 45–51. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-87775-8.50009-5. ISBN 978-0-444-87775-8.

... geodesy was thought to occupy the space delimited by the following definition ... "the science of measuring and portraying the earth's surface." ... the new definition of geodesy ... "the discipline that deals with the measurement and representation of the earth, including its gravity field, in a three-dimensional time varying space." ... a virtually identical definition ... the inclusion of other celestial bodies and their respective gravity fields.

- ^ "Geodetic Surveyors". Occupational Information Network. 2020-11-26. Retrieved 2022-01-28.

- ^ Kent, Alexander; Vujakovic, Peter (4 October 2017). The Routledge Handbook of Mapping and Cartography. Routledge. p. 187. ISBN 978-1-317-56822-3. Retrieved 6 December 2024.

- ^ Webb, Stephen H. (1 January 2010). The Dome of Eden: A New Solution to the Problem of Creation and Evolution. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 214. ISBN 978-1-60608-741-1. Retrieved 6 December 2024.

- ^ Posamentier, Alfred S.; Maresch, Guenter; Thaller, Bernd; Spreitzer, Christian; Geretschlager, Robert; Stuhlpfarrer, David; Dorner, Christian (24 November 2021). Geometry In Our Three-dimensional World. World Scientific. pp. 113–115. ISBN 978-981-12-3712-6. Retrieved 6 December 2024.

- ^ Foroughi, Ismael; Tenzer, Robert (2017). "Comparison of different methods for estimating the geoid-to-quasi-geoid separation". Geophysical Journal International. 210 (2): 1001–1020. doi:10.1093/gji/ggx221. hdl:10397/75053. ISSN 0956-540X.

- ^ (ISO 19111: Spatial referencing by coordinates).

- ^ Altamimi, Zuheir; Métivier, Laurent; Rebischung, Paul; Rouby, Hélène; Collilieux, Xavier (June 2017). "ITRF2014 plate motion model". Geophysical Journal International. 209 (3): 1906–1912. doi:10.1093/gji/ggx136.

- ^ Sośnica, Krzysztof; Thaller, Daniela; Dach, Rolf; Jäggi, Adrian; Beutler, Gerhard (August 2013). "Impact of loading displacements on SLR-derived parameters and on the consistency between GNSS and SLR results" (PDF). Journal of Geodesy. 87 (8): 751–769. Bibcode:2013JGeod..87..751S. doi:10.1007/s00190-013-0644-1. S2CID 56017067. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-03-18.

- ^ Zajdel, Radosław; Sośnica, Krzysztof; Bury, Grzegorz; Dach, Rolf; Prange, Lars; Kazmierski, Kamil (January 2021). "Sub-daily polar motion from GPS, GLONASS, and Galileo". Journal of Geodesy. 95 (1): 3. Bibcode:2021JGeod..95....3Z. doi:10.1007/s00190-020-01453-w.

- ^ Zajdel, Radosław; Sośnica, Krzysztof; Bury, Grzegorz; Dach, Rolf; Prange, Lars (July 2020). "System-specific systematic errors in earth rotation parameters derived from GPS, GLONASS, and Galileo". GPS Solutions. 24 (3): 74. Bibcode:2020GPSS...24...74Z. doi:10.1007/s10291-020-00989-w.

- ^ Zajdel, Radosław; Sośnica, Krzysztof; Bury, Grzegorz (January 2021). "Geocenter coordinates derived from multi-GNSS: a look into the role of solar radiation pressure modeling". GPS Solutions. 25 (1) 1. Bibcode:2021GPSS...25....1Z. doi:10.1007/s10291-020-01037-3.

- ^ Zajdel, R.; Sośnica, K.; Drożdżewski, M.; Bury, G.; Strugarek, D. (November 2019). "Impact of network constraining on the terrestrial reference frame realization based on SLR observations to LAGEOS". Journal of Geodesy. 93 (11): 2293–2313. Bibcode:2019JGeod..93.2293Z. doi:10.1007/s00190-019-01307-0.

- ^ Sośnica, Krzysztof; Bosy, Jarosław (2019). "Global Geodetic Observing System 2015–2018". Geodesy and Cartography: 121–144. doi:10.24425/gac.2019.126090.

- ^ Pearlman, M.; Arnold, D.; Davis, M.; Barlier, F.; Biancale, R.; Vasiliev, V.; Ciufolini, I.; Paolozzi, A.; Pavlis, E. C.; Sośnica, K.; Bloßfeld, M. (November 2019). "Laser geodetic satellites: a high-accuracy scientific tool". Journal of Geodesy. 93 (11): 2181–2194. Bibcode:2019JGeod..93.2181P. doi:10.1007/s00190-019-01228-y. S2CID 127408940.

Further reading

[edit]- F. R. Helmert, Mathematical and Physical Theories of Higher Geodesy, Part 1, ACIC (St. Louis, 1964). This is an English translation of Die mathematischen und physikalischen Theorieen der höheren Geodäsie, Vol 1 (Teubner, Leipzig, 1880).

- F. R. Helmert, Mathematical and Physical Theories of Higher Geodesy, Part 2, ACIC (St. Louis, 1964). This is an English translation of Die mathematischen und physikalischen Theorieen der höheren Geodäsie, Vol 2 (Teubner, Leipzig, 1884).

- B. Hofmann-Wellenhof and H. Moritz, Physical Geodesy, Springer-Verlag Wien, 2005. (This text is an updated edition of the 1967 classic by W.A. Heiskanen and H. Moritz).

- W. Kaula, Theory of Satellite Geodesy : Applications of Satellites to Geodesy, Dover Publications, 2000. (This text is a reprint of the 1966 classic).

- Vaníček P. and E.J. Krakiwsky, Geodesy: the Concepts, pp. 714, Elsevier, 1986.

- Torge, W (2001), Geodesy (3rd edition), published by de Gruyter, ISBN 3-11-017072-8.

- Thomas H. Meyer, Daniel R. Roman, and David B. Zilkoski. "What does height really mean?" (This is a series of four articles published in Surveying and Land Information Science, SaLIS.)

- "Part I: Introduction" SaLIS Vol. 64, No. 4, pages 223–233, December 2004.

- "Part II: Physics and gravity" SaLIS Vol. 65, No. 1, pages 5–15, March 2005.

- "Part III: Height systems" SaLIS Vol. 66, No. 2, pages 149–160, June 2006.

- "Part IV: GPS heighting" SaLIS Vol. 66, No. 3, pages 165–183, September 2006.

External links

[edit]- Geodetic awareness guidance note, Geodesy Subcommittee, Geomatics Committee, International Association of Oil & Gas Producers

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 11 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 607–615.