Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

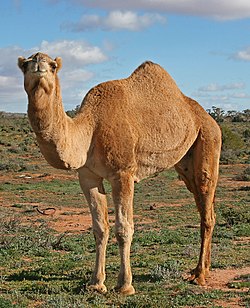

Camel

View on Wikipedia

| Camel Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Dromedary (Camelus dromedarius) | |

| |

| Bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Camelidae |

| Tribe: | Camelini |

| Genus: | Camelus Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Type species | |

| Camelus dromedarius [6] Linnaeus, 1758

| |

| Species | |

| |

| |

| Distribution of camels worldwide | |

| Synonyms | |

A camel (from Latin: camelus and Ancient Greek: κάμηλος (kamēlos) from Ancient Semitic: gāmāl[7][8]) is an even-toed ungulate in the genus Camelus that bears distinctive fatty deposits known as "humps" on its back. Camels have long been domesticated and, as livestock, they provide food (camel milk and meat) and textiles (fiber and felt from camel hair). Camels are working animals especially suited to their desert habitat and are a vital means of transport for passengers and cargo. There are three surviving species of camel. The one-humped dromedary makes up 94% of the world's camel population, and the two-humped Bactrian camel makes up 6%. The wild Bactrian camel is a distinct species that is not ancestral to the domestic Bactrian camel, and is now critically endangered, with fewer than 1,000 individuals.

The word camel is also used informally in a wider sense, where the more correct term is "camelid", to include all seven species of the family Camelidae: the true camels (the above three species), along with the "New World" camelids: the llama, the alpaca, the guanaco, and the vicuña, which belong to the separate tribe Lamini.[9] Camelids originated in North America during the Eocene, with the ancestor of modern camels, Paracamelus, migrating across the Bering land bridge into Asia during the late Miocene, around 6 million years ago.

Taxonomy

[edit]Extant species

[edit]Three species are extant:[10][11]

| Common name | Scientific name and subspecies | Range | Size and ecology | IUCN status and estimated population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bactrian camel | Camelus bactrianus Linnaeus, 1758 |

Domesticated; Central Asia, including the historical region of Bactria and Turkey.

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

NE

|

| Dromedary / Arabian camel | Camelus dromedarius Linnaeus, 1758 |

Domesticated; the Middle East, Sahara Desert, and South Asia; introduced to Australia

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

NE

|

| Wild Bactrian camel | Camelus ferus Przewalski, 1878 |

Remote areas of northwest China and Mongolia

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

EN

|

Biology

[edit]The average life expectancy of a camel is 40 to 50 years.[12] A full-grown adult dromedary camel stands 1.85 m (6 ft 1 in) at the shoulder and 2.15 m (7 ft 1 in) at the hump.[13] Bactrian camels can be a foot taller. Camels can run at up to 65 km/h (40 mph) in short bursts and sustain speeds of up to 40 km/h (25 mph).[14] Bactrian camels weigh 300 to 1,000 kg (660 to 2,200 lb) and dromedaries 300 to 600 kg (660 to 1,320 lb). The widening toes on a camel's hoof provide supplemental grip for varying soil sediments.[15]

The male dromedary camel has an organ called a dulla in his throat, a large, inflatable sac that he extrudes from his mouth when in rut to assert dominance and attract females. It resembles a long, swollen, pink tongue hanging out of the side of the camel's mouth.[16] Camels mate by having both male and female sitting on the ground, with the male mounting from behind.[17] The male usually ejaculates three or four times within a single mating session.[18] Camelids are the only ungulates to mate in a sitting position.[19]

Ecological and behavioral adaptations

[edit]

It is a common myth that a camel stores water in its hump,[20] but the humps in fact are reservoirs of fatty tissue, which can be used as a reserve source of calories, not water. When this tissue is metabolized, it yields a greater mass of water than that of the fat processed. This fat metabolization, while releasing energy, causes water to evaporate from the lungs during respiration (as oxygen is required for the metabolic process): overall, there is a net decrease in water.[21][22]

Camels have a series of physiological adaptations that allow them to withstand long periods of time without any external source of water.[24] The dromedary camel can drink as seldom as once every 10 days even under very hot conditions, and can lose up to 30% of its body mass due to dehydration.[25] They can drink as much as 30 imperial gallons (140 litres) at a time[26] but this is stored in the animal's bloodstream, not, as popularly believed, in its humps.[20]

Unlike other mammals, camels' red blood cells are oval rather than circular in shape. This facilitates the flow of red blood cells during dehydration[27] and makes them better at withstanding high osmotic variation without rupturing when drinking large amounts of water.[28][29]

Camels are able to withstand changes in body temperature and water consumption that would kill most other mammals. Their temperature ranges from 34 °C (93 °F) at dawn and steadily increases to 40 °C (104 °F) by sunset, before they cool off at night again.[24] In general, to compare between camels and the other livestock, camels lose only 1.3 liters of fluid intake every day while the other livestock lose 20 to 40 liters per day.[30] Maintaining the brain temperature within certain limits is critical for animals; to assist this, camels have a rete mirabile, a complex of arteries and veins lying very close to each other which utilizes countercurrent blood flow to cool blood flowing to the brain.[31] Camels rarely sweat, even when ambient temperatures reach 49 °C (120 °F).[32] Any sweat that does occur evaporates at the skin level rather than at the surface of their coat; the heat of vaporization therefore comes from body heat rather than ambient heat. Camels can withstand losing 25% of their body weight in water, whereas most other mammals can withstand only about 12–14% dehydration before cardiac failure results from circulatory disturbance.[29]

When the camel exhales, water vapor becomes trapped in their nostrils and is reabsorbed into the body as a means to conserve water.[33] Camels eating green herbage can ingest sufficient moisture in milder conditions to maintain their bodies' hydrated state without the need for drinking.[34]

Camels have three-chambered stomachs and perform rumination as part of their digestive process, even though they are not part of the ruminant sub-order.[35]

The camel's thick coat insulates it from the intense heat radiated from desert sand; a shorn camel must sweat 50% more to avoid overheating.[36] During the summer the coat becomes lighter in color, reflecting light as well as helping avoid sunburn.[29] The camel's long legs help by keeping its body farther from the ground, which can heat up to 70 °C (158 °F).[37][38] Dromedaries have a pad of thick tissue over the sternum called the pedestal. When the animal lies down in a sternal recumbent position, the pedestal raises the body from the hot surface and allows cooling air to pass under the body.[31]

Camels' mouths have a thick leathery lining, allowing them to chew thorny desert plants. Long eyelashes and ear hairs, together with nostrils that can close, form a barrier against sand. If sand gets lodged in their eyes, they can dislodge it using their translucent third eyelid (also known as the nictitating membrane). The camels' gait and widened feet help them move without sinking into the sand.[37][39]

The kidneys and intestines of a camel are very efficient at reabsorbing water. Camels' kidneys have a 1:4 cortex to medulla ratio.[40] Thus, the medullary part of a camel's kidney occupies twice as much area as a cow's kidney. Secondly, renal corpuscles have a smaller diameter, which reduces surface area for filtration. These two major anatomical characteristics enable camels to conserve water and limit the volume of urine in extreme desert conditions.[41] Camel urine comes out as a thick syrup, and camel faeces are so dry that they do not require drying when used to fuel fires.[42][43][44][45]

The camel immune system differs from those of other mammals. Normally, the Y-shaped antibody molecules consist of two heavy (or long) chains along the length of the Y, and two light (or short) chains at each tip of the Y.[46] Camels, in addition to these, also have antibodies made of only two heavy chains, a trait that makes them smaller and more durable.[46] These "heavy-chain-only" antibodies, discovered in 1993, are thought to have developed 50 million years ago, after camelids split from ruminants and pigs.[46]

The parasite Trypanosoma evansi causes the disease surra in camels.[47]: 2

Genetics

[edit]The karyotypes of different camelid species have been studied earlier by many groups,[48][49][50][51][52][53] but no agreement on chromosome nomenclature of camelids has been reached. A 2007 study flow sorted camel chromosomes, building on the fact that camels have 37 pairs of chromosomes (2n=74), and found that the karyotype consisted of one metacentric, three submetacentric, and 32 acrocentric autosomes. The Y is a small metacentric chromosome, while the X is a large metacentric chromosome.[54]

The hybrid camel, a hybrid between Bactrian and dromedary camels, has one hump, though it has an indentation 4–12 cm (1.6–4.7 in) deep that divides the front from the back. The hybrid is 2.15 m (7 ft 1 in) at the shoulder and 2.32 m (7 ft 7 in) tall at the hump. It weighs an average of 650 kg (1,430 lb) and can carry around 400 to 450 kg (880 to 990 lb), which is more than either the dromedary or Bactrian can.[55]

According to molecular data, the wild Bactrian camel (C. ferus) separated from the domestic Bactrian camel (C. bactrianus) about 1 million years ago.[56][57] New World and Old World camelids diverged about 11 million years ago.[58] In spite of this, these species can hybridize and produce viable offspring.[59] The cama is a camel-llama hybrid bred by scientists to see how closely related the parent species are.[60] Scientists collected semen from a camel via an artificial vagina and inseminated a llama after stimulating ovulation with gonadotrophin injections.[61] The cama is halfway in size between a camel and a llama and lacks a hump. It has ears intermediate between those of camels and llamas, longer legs than the llama, and partially cloven hooves.[62][63] Like the mule, camas are sterile, despite both parents having the same number of chromosomes.[61]

Evolution

[edit]The earliest known camel, called Protylopus, lived in North America 40 to 50 million years ago (during the Eocene).[18] It was about the size of a rabbit and lived in the open woodlands of what is now South Dakota.[64][65] By 35 million years ago, the Poebrotherium was the size of a goat and had many more traits similar to camels and llamas.[66][67] The hoofed Stenomylus, which walked on the tips of its toes, also existed around this time, and the long-necked Aepycamelus evolved in the Miocene.[68] The split between the tribes Camelini, which contains modern camels and Lamini, modern llamas, alpacas, vicuñas, and guanacos, is estimated to have occurred over 16 million years ago.[69]

The ancestor of modern camels, Paracamelus, migrated into Eurasia from North America via Beringia during the late Miocene, between 7.5 and 6.5 million years ago.[70][71][72] During the Pleistocene, around 3 to 1 million years ago, the North American Camelidae spread to South America as part of the Great American Interchange via the newly formed Isthmus of Panama, where they gave rise to guanacos and related animals.[18][64][65] Populations of Paracamelus continued to exist in the North American Arctic into the Early Pleistocene.[71][73] This creature is estimated to have stood around nine feet (2.7 metres) tall. The Bactrian camel diverged from the dromedary about 1 million years ago, according to the fossil record.[74]

The last camel native to North America was Camelops hesternus, which vanished along with horses, short-faced bears, mammoths and mastodons, ground sloths, sabertooth cats, and many other megafauna as part of the Quaternary extinction event, coinciding with the migration of humans from Asia at the end of the Pleistocene, around 13–11,000 years ago.[75][76]

An extinct giant camel species, Camelus knoblochi roamed Asia during the Late Pleistocene, before becoming extinct around 20,000 years ago.[77]

-

Stenomylus illustration

-

Stenomylus skeleton

-

Poebrotherium skeleton

-

Procamelus skull

-

Camelops hesternus, the last true camel native to North America

Domestication

[edit]

Like horses, camels originated in North America and eventually spread across Beringia to Asia. They survived in the Old World, and eventually humans domesticated them and spread them globally. Along with many other megafauna in North America, the original wild camels were wiped out during the spread of the first indigenous peoples of the Americas from Asia into North America, 10 to 12,000 years ago; although fossils have never been associated with definitive evidence of hunting.[75][76]

Most camels surviving today are domesticated.[45][78] Although feral populations exist in Australia, India and Kazakhstan, wild camels survive only in the wild Bactrian camel population of the Gobi Desert.[12]

History

[edit]When humans first domesticated camels is disputed. Dromedaries may have first been domesticated by humans in Somalia or South Arabia sometime during the 3rd millennium BC, the Bactrian in central Asia around 2,500 BC,[18][79][80][81] as at Shar-i Sokhta (also known as the Burnt City), Iran.[82] A study from 2016, which genotyped and used world-wide sequencing of modern and ancient mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), suggested that they were initially domesticated in the southeast Arabian Peninsula,[83] with the Bactrian type later being domesticated around Central Asia.[84]

Martin Heide's 2010 work on the domestication of the camel tentatively concludes that humans had domesticated the Bactrian camel by at least the middle of the third millennium somewhere east of the Zagros Mountains, with the practice then moving into Mesopotamia. Heide suggests that mentions of camels "in the patriarchal narratives may refer, at least in some places, to the Bactrian camel", while noting that the camel is not mentioned in relationship to Canaan.[85] Heide and Joris Peters reasserted that conclusion in their 2021 study on the subject.[86]

In 2009–2013, excavations in the Timna Valley by Lidar Sapir-Hen and Erez Ben-Yosef discovered what may be the earliest domestic camel bones yet found in Israel or even outside the Arabian Peninsula, dating to around 930 BC. This garnered considerable media coverage, as it is strong evidence that the stories of Abraham, Jacob, Esau, and Joseph were written after this time.[87][88]

The existence of camels in Mesopotamia and Arabia but not in Syria is not a new idea. The historian Richard Bulliet thought that although camels were occasionally mentioned in the Bible, this didn't mean that the domestic camels were common in the Holy Land at that time.[89] The archaeologist William F. Albright, writing even earlier, saw camels in the Bible as an anachronism.[90]

The official report by Sapir-Hen and Ben-Joseph says:

The introduction of the dromedary camel (Camelus dromedarius) as a pack animal to the southern Levant ... substantially facilitated trade across the vast deserts of Arabia, promoting both economic and social change (e.g., Kohler 1984; Borowski 1998: 112–116; Jasmin 2005). This ... has generated extensive discussion regarding the date of the earliest domestic camel in the southern Levant (and beyond) (e.g., Albright 1949: 207; Epstein 1971: 558–584; Bulliet 1975; Zarins 1989; Köhler-Rollefson 1993; Uerpmann and Uerpmann 2002; Jasmin 2005; 2006; Heide 2010; Rosen and Saidel 2010; Grigson 2012). Most scholars today agree that the dromedary was exploited as a pack animal sometime in the early Iron Age (not before the 12th century [BC])

and concludes:

Current data from copper smelting sites of the Arabah Valley enable us to pinpoint the introduction of domestic camels to the southern Levant more precisely based on stratigraphic contexts associated with an extensive suite of radiocarbon dates. The data indicate that this event occurred not earlier than the last third of the 10th century [BC] and most probably during this time. The coincidence of this event with a major reorganization of the copper industry of the region—attributed to the results of the campaign of Pharaoh Shoshenq I—raises the possibility that the two were connected, and that camels were introduced as part of the efforts to improve efficiency by facilitating trade.[88]

-

A camel serving as a draft animal in Pakistan (2009)

-

A camel in a ceremonial procession, its rider playing kettledrums, Mughal Empire (c. 1840)

-

Joseph Sells Grain by Bartholomeus Breenbergh (1655), showing camel with rider at left

Textiles

[edit]Desert tribes and Mongolian nomads use camel hair for tents, yurts, clothing, bedding and accessories. Camels have outer guard hairs and soft inner down, and the fibers may also be sorted by color and age of the animal. The guard hairs can be felted for use as waterproof coats for the herdsmen, while the softer hair is used for premium goods.[91] The fiber can be spun for use in weaving or made into yarns for hand knitting or crochet. Pure camel hair is recorded as being used for western garments from the 17th century onwards, and from the 19th century a mixture of wool and camel hair was used.[92]

Military uses

[edit]

By at least 1200 BC the first camel saddles had appeared, and Bactrian camels could be ridden. The first saddle was positioned to the back of the camel, and control of the Bactrian camel was exercised by means of a stick. However, between 500 and 100 BC, Bactrian camels came into military use. New saddles, which were inflexible and bent, were put over the humps and divided the rider's weight over the animal. In the seventh century BC the military Arabian saddle evolved, which again improved the saddle design slightly.[93][94]

Military forces have used camel cavalries in wars throughout Africa, the Middle East, and their use continues into the modern-day within the Border Security Force (BSF) of India. The first documented use of camel cavalries occurred in the Battle of Qarqar in 853 BC.[95][96][97] Armies have also used camels as freight animals instead of horses and mules.[98][99]

The East Roman Empire used auxiliary forces known as dromedarii, whom the Romans recruited in desert provinces.[100][101] The camels were used mostly in combat because of their ability to scare off horses at close range (horses are afraid of the camels' scent),[19] a quality famously employed by the Achaemenid Persians when fighting Lydia in the Battle of Thymbra (547 BC).[55][102][103]

19th and 20th centuries

[edit]

The United States Army established the U.S. Camel Corps, stationed in California, in the 19th century.[19] One may still see stables at the Benicia Arsenal in Benicia, California, where they nowadays serve as the Benicia Historical Museum.[104] Though the experimental use of camels was seen as a success (John B. Floyd, Secretary of War in 1858, recommended that funds be allocated towards obtaining a thousand more camels), the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 saw the end of the Camel Corps: Texas became part of the Confederacy, and most of the camels were left to wander away into the desert.[99]

France created a méhariste camel corps in 1912 as part of the Armée d'Afrique in the Sahara[105] in order to exercise greater control over the camel-riding Tuareg and Arab insurgents, as previous efforts to defeat them on foot had failed.[106] The Free French Camel Corps fought during World War II, and camel-mounted units remained in service until the end of French rule over Algeria in 1962.[107]

In 1916, the British created the Imperial Camel Corps. It was originally used to fight the Senussi, but was later used in the Sinai and Palestine Campaign in World War I. The Imperial Camel Corps comprised infantrymen mounted on camels for movement across desert, though they dismounted at battle sites and fought on foot. After July 1918, the Corps began to become run down, receiving no new reinforcements, and was formally disbanded in 1919.[108]

In World War I, the British Army also created the Egyptian Camel Transport Corps, which consisted of a group of Egyptian camel drivers and their camels. The Corps supported British war operations in Sinai, Palestine, and Syria by transporting supplies to the troops.[109][110][111]

The Somaliland Camel Corps was created by colonial authorities in British Somaliland in 1912; it was disbanded in 1944.[112]

Bactrian camels were used by Romanian forces during World War II in the Caucasian region.[113] At the same period the Soviet units operating around Astrakhan in 1942 adopted local camels as draft animals due to shortage of trucks and horses, and kept them even after moving out of the area. Despite severe losses, some of these camels ended up as far west as to Berlin itself.[114]

The Bikaner Camel Corps of British India fought alongside the British Indian Army in World Wars I and II.[115]

The Tropas Nómadas (Nomad Troops) were an auxiliary regiment of Sahrawi tribesmen serving in the colonial army in Spanish Sahara (today Western Sahara). Operational from the 1930s until the end of the Spanish presence in the territory in 1975, the Tropas Nómadas were equipped with small arms and led by Spanish officers. The unit guarded outposts and sometimes conducted patrols on camelback.[116][117]

21st century competition

[edit]The annual King Abdulaziz Camel Festival is held in Saudi Arabia. In addition to camel racing and camel milk tasting, the festival holds a camel "beauty pageant" with prize money of $57m (£40m). In 2018, 12 camels were disqualified from the beauty contest after their owners were found to have injected them with botox.[118] In a similar incident in 2021, over 40 camels were disqualified.[119]

Food uses

[edit]Camel meat and milk are foods that are found in many cuisines, typically in Middle Eastern, North African and some Australian cuisines.[120][121][122][123] Camels provide food in the form of meat and milk.[124]

Dairy

[edit]

Camel milk is a staple food of desert nomad tribes and is sometimes considered a meal itself; a nomad can live on only camel milk for almost a month.[19][42][125][126]

Camel milk can readily be made into yogurt, but can only be made into butter if it is soured first, churned, and a clarifying agent is then added.[19] Until recently, camel milk could not be made into camel cheese because rennet was unable to coagulate the milk proteins to allow the collection of curds.[127] Developing less wasteful uses of the milk, the FAO commissioned Professor J.P. Ramet of the École Nationale Supérieure d'Agronomie et des Industries Alimentaires, who was able to produce curdling by the addition of calcium phosphate and vegetable rennet in the 1990s.[128] The cheese produced from this process has low levels of cholesterol and is easy to digest, even for the lactose intolerant.[129][130]

Camel milk can also be made into ice cream.[131][132]

Meat

[edit]

Approximately 3.3 million camels and camelids are slaughtered each year for meat worldwide.[133] A camel carcass can provide a substantial amount of meat. The male dromedary carcass can weigh 300–400 kg (661–882 lb), while the carcass of a male Bactrian can weigh up to 650 kg (1,433 lb). The carcass of a female dromedary weighs less than the male, ranging between 250 and 350 kg (550 and 770 lb).[18] The brisket, ribs and loin are among the preferred parts, and the hump is considered a delicacy.[134] The hump contains "white and sickly fat", which can be used to make the khli (preserved meat) of mutton, beef, or camel.[135] On the other hand, camel milk and meat are rich in protein, vitamins, glycogen, and other nutrients making them essential in the diet of many people. From chemical composition to meat quality, the dromedary camel is the preferred breed for meat production. It does well even in arid areas due to its unusual physiological behaviors and characteristics, which include tolerance to extreme temperatures, radiation from the sun, water paucity, rugged landscape and low vegetation.[136] Camel meat is reported to taste like coarse beef, but older camels can prove to be very tough,[13][18] although camel meat becomes tenderer the more it is cooked.[137]

Camel is one of the animals that can be ritually slaughtered and divided into three portions (one for the home, one for extended family/social networks, and one for those who cannot afford to slaughter an animal themselves) for the qurban of Eid al-Adha.[138][139]

The Abu Dhabi Officers' Club serves a camel burger mixed with beef or lamb fat in order to improve the texture and taste.[140] In Karachi, Pakistan, some restaurants prepare nihari from camel meat.[141] Specialist camel butchers provide expert cuts, with the hump considered the most popular.[142]

Camel meat has been eaten for centuries. It has been recorded by ancient Greek writers as an available dish at banquets in ancient Persia, usually roasted whole.[143] The Roman emperor Heliogabalus enjoyed camel's heel.[42] Camel meat is mainly eaten in certain regions, including Eritrea, Somalia, Djibouti, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Syria, Libya, Sudan, Ethiopia, Kazakhstan, and other arid regions where alternative forms of protein may be limited or where camel meat has had a long cultural history.[18][42][134] Camel blood is also consumable, as is the case among pastoralists in northern Kenya, where camel blood is drunk with milk and acts as a key source of iron, vitamin D, salts and minerals.[18][134][144]

A 2005 report issued jointly by the Saudi Ministry of Health and the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention details four cases of human bubonic plague resulting from the ingestion of raw camel liver.[145]

Camel meat is also occasionally found in Australian cuisine: for example, a camel lasagna is available in Alice Springs.[143][144] Australia has exported camel meat, primarily to the Middle East but also to Europe and the US, for many years.[146] The meat is very popular among East African Australians, such as Somalis, and other Australians have also been buying it. The feral nature of the animals means they produce a different type of meat to farmed camels in other parts of the world,[121] and it is sought after because it is disease-free, and a unique genetic group. Demand is outstripping supply, and governments are being urged not to cull the camels, but redirect the cost of the cull into developing the market. Australia has seven camel dairies, which produce milk, cheese and skincare products in addition to meat.[147]

Religion

[edit]Islam

[edit]Muslims consider camel meat halal (Arabic: حلال, 'allowed'). However, according to some Islamic schools of thought, a state of impurity is brought on by the consumption of it. Consequently, these schools hold that Muslims must perform wudhu (ablution) before the next time they pray after eating camel meat.[148] Also, some Islamic schools of thought consider it haram (Arabic: حرام, 'forbidden') for a Muslim to perform Salat in places where camels lie, as it is said to be a dwelling place of the Shaytan (Arabic: شيطان, 'Devil').[148] According to Abu Yusuf (d.798), the urine of camels may be used for medical treatment if necessary, but according to Abū Ḥanīfah, the drinking of camel urine is discouraged.[149]

Islamic texts contain several stories featuring camels. In the story of the people of Thamud, the prophet Salih miraculously brings forth a naqat (Arabic: ناقة, 'milch-camel') out of a rock. After Muhammad migrated from Mecca to Medina (the Hijrah), he allowed his she-camel to roam there; the location where the camel stopped to rest determined the location where he would build his house in Medina.[150]

Judaism

[edit]According to Jewish tradition, camel meat and milk are not kosher.[151] Camels possess only one of the two kosher criteria; although they chew their cud, they do not have cloven hooves: "But these you shall not eat among those that bring up the cud and those that have a cloven hoof: the camel, because it brings up its cud, but does not have a [completely] cloven hoof; it is unclean for you."[152]

The Palestinian Muslim Makhamara clan in Yatta, who claim descent from Jews, reportedly avoid eating camel meat, a practice cited as evidence of their Jewish origins.[153][154]

Cultural depictions

[edit]What may be the oldest carvings of camels were discovered in 2018 in Saudi Arabia. They were analysed by researchers from several scientific disciplines and, in 2021, were estimated to be 7,000 to 8,000 years old.[155] The dating of rock art is made difficult by the lack of organic material in the carvings that may be tested, so the researchers attempting to date them tested animal bones found associated with the carvings, assessed erosion patterns, and analysed tool marks in order to determine a correct date for the creation of the sculptures. This Neolithic dating would make the carvings significantly older than Stonehenge (5,000 years old) and the Egyptian pyramids at Giza (4,500 years old) and it predates estimates for the domestication of camels.

-

Shadda (cover,detail), Karabagh region, southwest Caucasus, early 19th century

-

Vessel in the form of a recumbent camel with jugs, 250 BC – 224 AD, Brooklyn Museum

-

Maru Ragini (Dhola and Maru Riding on a Camel), c. 1750, Brooklyn Museum

-

The Magi Journeying (Les rois mages en voyage)—James Tissot, c. 1886, Brooklyn Museum

-

How the Camel Got His Hump (From Rudyard Kipling's Just So Stories)

Distribution and numbers

[edit]

There are approximately 14 million camels alive as of 2010[update], with 90% being dromedaries.[156] Dromedaries alive today are domesticated animals (mostly living in the Horn of Africa, the Sahel, Maghreb, Middle East and South Asia). The Horn region alone has the largest concentration of camels in the world,[23] where the dromedaries constitute an important part of local nomadic life. They provide nomadic people in Somalia[18] and Ethiopia with milk, food, and transportation.[126][157][158][159]

Over one million dromedary camels are estimated to be feral in Australia, descended from those introduced as a method of transport in the 19th and early 20th centuries.[160] This population is growing about 8% per year;[161] it was estimated at 700,000 in 2008.[144][156][162] Representatives of the Australian government have culled more than 100,000 of the animals in part because the camels use too much of the limited resources needed by sheep farmers.[163]

A small population of introduced camels, dromedaries and Bactrians, wandered through Southwestern United States after having been imported in the 19th century as part of the U.S. Camel Corps experiment. When the project ended, they were used as draft animals in mines and escaped or were released. Twenty-five U.S. camels were bought and exported to Canada during the Cariboo Gold Rush.[99]

The Bactrian camel is, as of 2010[update], reduced to an estimated 1.4 million animals, most of which are domesticated.[45][156][164] The Wild Bactrian camel is the only truly wild (as opposed to feral) camel in the world. It is a distinct species that is not ancestral to the domestic Bactrian camel. The wild camels are critically endangered and number approximately 950, inhabiting the Gobi and Taklamakan Deserts in China and Mongolia.[165]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

- ^ "Fossilworks: Camelus". fossilworks.org. Archived from the original on 2021-12-12. Retrieved 2021-12-17.

- ^ Geraads, D.; Barr, W. A.; Reed, D.; Laurin, M.; Alemseged, Z. (2019). "New Remains of Camelus grattardi (Mammalia, Camelidae) from the Plio-Pleistocene of Ethiopia and the Phylogeny of the Genus" (PDF). Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 28 (2): 359–370. doi:10.1007/s10914-019-09489-2. ISSN 1064-7554. S2CID 209331892. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-10-03.

- ^ Titov, V. V. (2008). "Habitat conditions for Camelus knoblochi and factors in its extinction". Quaternary International. 179 (1): 120–125. Bibcode:2008QuInt.179..120T. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2007.10.022.

- ^ Falconer, Hugh (1868). Palæontological Memoirs and Notes of the Late Hugh Falconer: Fauna antiqua sivalensis. R. Hardwicke. p. 231.

- ^ Martini, P.; Geraads, D. (2019). "Camelus thomasi Pomel, 1893 from the Pleistocene type-locality Tighennif (Algeria). Comparisons with modern Camelus". Geodiversitas. 40 (1): 115–134. doi:10.5252/geodiversitas2018v40a5.

- ^ Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M., eds. (2005). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ "camel". The New Oxford American Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press, Inc. 2005.

- ^ Herper, Douglas. "camel". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ^ Bornstein, Set (2010). "Important ectoparasites of Alpaca (Vicugna pacos)". Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica. 52 (Suppl 1) S17. doi:10.1186/1751-0147-52-S1-S17. ISSN 1751-0147. PMC 2994293.

- ^ Burger, P. A.; Ciani, E.; Faye, B. (2019-09-18). "Old World camels in a modern world – a balancing act between conservation and genetic improvement". Animal Genetics. 50 (6): 598–612. doi:10.1111/age.12858. PMC 6899786. PMID 31532019.

- ^ Chuluunbat, B.; Charruau, P.; Silbermayr, K.; Khorloojav, T.; Burger, P. A. (2014). "Genetic diversity and population structure of Mongolian domestic Bactrian camels (Camelus bactrianus)". Anim Genet. 45 (4): 550–558. doi:10.1111/age.12158. PMC 4171754. PMID 24749721.

- ^ a b "Bactrian Camel: Camelus bactrianus". National Geographic. 10 May 2011. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ^ a b "The amazing characteristics of the camels". Camello Safari. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- ^ "How Fast Can Camels Run and How Long Can They Run For?". Big Site of Amazing Facts. 17 April 2010. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ^ Fayed, R. H. "Adaptation of the Camel to Desert environment". ESARF. Retrieved 21 April 2025.

- ^ Abu-Zidana, Fikri M.; Eida, Hani O.; Hefnya, Ashraf F.; Bashira, Masoud O.; Branickia, Frank (18 December 2011). "Camel bite injuries in United Arab Emirates: A 6 year prospective study". Injury. 43 (9): 1617–1620. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2011.10.039. PMID 22186231.

The male mature camel has a specialized inflatable diverticulum of the soft palate called the "Dulla". and During rutting the Dulla enlarges on filling with air from the trachea until it hangs out of the mouth of the camel and comes to resemble a pink ball. This occurs in only the one-humped camel. Copious saliva turns to foam covering the mouth as the male gurgles and makes metallic sounds. [6 cites to 5 references omitted]

- ^ Two Male Camels Fighting Over One Female. Youtube.com. Archived from the original on 2015-12-19. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Mukasa-Mugerwa, E. (1981). The Camel (Camelus Dromedarius): A Bibliographical Review. International Livestock Centre for Africa Monograph. Vol. 5. Ethiopia: International Livestock Centre for Africa. pp. 1, 3, 20–21, 65, 67–68.

- ^ a b c d e "Bactrian & Dromedary Camels". Factsheets. San Diego Zoo Global Library. March 2009. Archived from the original on 22 September 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- ^ a b "How much water does a camel's hump hold?". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2025-05-06.

- ^ Vann Jones, Kerstin. "What secrets lie within the camel's hump?". Sweden: Lund University. Archived from the original on 23 May 2009. Retrieved 7 January 2008.

- ^ Rastogi, S. C. (1971). Essentials Of Animal Physiology. New Age International. pp. 180–181. ISBN 9788122412796.

- ^ a b Bernstein, William J. (2009). A Splendid Exchange: How Trade Shaped the World. Grove Press. p. 56. ISBN 9780802144164.

- ^ a b Roberts, Michael Bliss Vaughan (1986). Biology: A Functional Approach. Nelson Thornes. pp. 234–235, 241. ISBN 9780174480198.

- ^ UNESCO. "The Camel from Tradition To Modern Times" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-11-09.

- ^ Crupi, Sarah (2021-04-06). "Truth or Tail: A camel's hump". www.clevelandzoosociety.org. Retrieved 2025-08-04.

- ^ Eitan, A; Aloni, B; Livne, A (1976). "Unique properties of the camel erythrocyte membraneII. Organization of membrane proteins". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 426 (4): 647–58. doi:10.1016/0005-2736(76)90129-2. PMID 816376.

- ^ "Dromedary". Hannover Zoo. Archived from the original on 25 October 2005. Retrieved 8 January 2008.

- ^ a b c Halpern, E. Anette (1999). "Camel". In Mares; Michael A. (eds.). Deserts. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 96–97. ISBN 9780806131467. Archived from the original on 2016-04-29.

- ^ Breulmann, M., Böer, B., Wernery, U., Wernery, R., El Shaer, H., Alhadrami, G., ... Norton, J. (2007). "The Camel From Tradition to Modern Times" (PDF). UNESCO DOHA OFFICE.

- ^ a b Inside Nature's Giants. Channel 4 (UK) documentary. Transmitted 30 August 2011

- ^ "Arabian (Dromedary) Camel". National Geographic. National Geographic Society. 10 May 2011. Archived from the original on 19 November 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ^ Lewis, Paul (12 July 1981). "A Pilgrimage To A Mystic's Hermitage In Algeria". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 August 2009. Retrieved 7 March 2009.

- ^ "Camels, llamas and alpacas". A manual for primary animal health care worker. FAO Animal Health Manual. FAO Agriculture and Consumer Protection. 1994. Archived from the original on 2008-07-27.

- ^ Fowler, M.E. (2010). Medicine and Surgery of Camelids, Ames, Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell.

- ^ Schmidt-Nielsen, K. (1964). Desert Animals: Physiological Problems of Heat and Water. New York: Oxford University Press (OUP). Cited in "Coat of fur on the camel". Davidson College. Archived from the original on February 25, 2003.

- ^ a b Bronx Zoo. "Camel Adaptations". Wildlife Conservation Society. Archived from the original (Flash) on 26 June 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ^ Rundel, Philip Wilson; Gibson, Arthur C. (30 September 2005). "Adaptations of Mojave Desert Animals". Ecological Communities And Processes in a Mojave Desert Ecosystem: Rock Valley, Nevada. Cambridge University Press (CUP). p. 130. ISBN 9780521021418.

- ^ Silverstein, Alvin; Silverstein, Virginia B; Silverstein, Virginia; Silverstein Nunn, Laura (2008). Adaptation. Twenty-First Century Books. pp. 42–43. ISBN 9780822534341.

- ^ "Morphometric analysis of heart, kidneys and adrenal glands in dromedary camel calves (PDF Download Available)". ResearchGate. Archived from the original on 2017-03-04. Retrieved 2017-03-03.

- ^ Rehan S and AS Qureshi, 2006. Microscopic evaluation of the heart, kidneys and adrenal glands of one-humped camel calves (Camelus dromedarius) using semi automated image analysis system. J Camel Pract Res. 13(2): 123

- ^ a b c d Davidson, Alan; Davidson, Jane (15 October 2006). Jaine, Tom (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Food (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press, US. pp. 68, 129, 266, 762. ISBN 978-0192806819.

- ^ "Kidneys and Concentrated Urine". Temperature and Water Relations in Dromedary Camels (Camelus dromedarius). Davidson College. Archived from the original on February 25, 2003.

- ^ "Fun facts about the Camel". The Jungle Store. Archived from the original on 17 November 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- ^ a b c Fedewa, Jennifer L. (2000). "Camelus bactrianus". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- ^ a b c Koenig, R. (2007). "'Camelized' Antibodies Make Waves". Veterinary Medicine. Science. 318 (5855): 1373. doi:10.1126/science.318.5855.1373. PMID 18048665. S2CID 71028674.

- ^ Sazmand, Alireza; Joachim, Anja (2017). "Parasitic diseases of camels in Iran (1931–2017) – a literature review". Parasite. 24. EDP Sciences: 1–15. doi:10.1051/parasite/2017024. ISSN 1776-1042. PMC 5479402. PMID 28617666. S2CID 13783061. Article Number 21.

- ^ Taylor, K.M.; Hungerford, D.A.; Snyder, R.L.; Ulmer Jr., F.A. (1968). "Uniformity of karyotypes in the Camelidae". Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 7 (1): 8–15. doi:10.1159/000129967. PMID 5659175.

- ^ Koulischer, L; Tijskens, J; Mortelmans, J (1971). "Mammalian cytogenetics. IV. The chromosomes of two male Camelidae: Camelus bactrianus and Lama vicugna". Acta Zoologica et Pathologica Antverpiensia. 52: 89–92. PMID 5163286.

- ^ Bianchi, N. O.; Larramendy, M. L.; Bianchi, M. S.; Cortés, L. (1986). "Karyological conservatism in South American camelids". Experientia. 42 (6): 622–4. doi:10.1007/BF01955563. S2CID 23440910.

- ^ Bunch, Thomas D.; Foote, Warren C.; Maciulis, Alma (1985). "Chromosome banding pattern homologies and NORs for the Bactrian camel, guanaco, and llama". Journal of Heredity. 76 (2): 115–8. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a110034.

- ^ O'Brien, Stephen J.; Menninger, Joan C.; Nash, William G., eds. (2006). Atlas of Mammalian Chromosomes. New York: Wiley-Liss. p. 547. ISBN 978-0-471-35015-6.

- ^ Di Berardino, D.; Nicodemo, D.; Coppola, G.; King, A.W.; Ramunno, L.; Cosenza, G.F.; Iannuzzi, L.; Di Meo, G.P.; et al. (2006). "Cytogenetic characterization of alpaca (Lama pacos, fam. Camelidae) prometaphase chromosomes". Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 115 (2): 138–44. doi:10.1159/000095234. PMID 17065795. S2CID 21378633.

- ^ Balmus, Gabriel; Trifonov, Vladimir A.; Biltueva, Larisa S.; O'Brien, Patricia C.M.; Alkalaeva, Elena S.; Fu, Beiyuan; Skidmore, Julian A.; Allen, Twink; et al. (2007). "Cross-species chromosome painting among camel, cattle, pig and human: further insights into the putative Cetartiodactyla ancestral karyotype". Chromosome Research. 15 (4): 499–515. doi:10.1007/s10577-007-1154-x. PMID 17671843. S2CID 23226488.

- ^ a b Potts, Danel. "Bactrian Camels and Bactrian-Dromedary Hybrids". Silkroad. 3 (1). Archived from the original on 2016-06-23. Retrieved 2012-11-29.

- ^ Mohandesan, Elmira; Fitak, Robert R.; Corander, Jukka; Yadamsuren, Adiya; Chuluunbat, Battsetseg; Abdelhadi, Omer; Raziq, Abdul; Nagy, Peter; Stalder, Gabrielle (30 August 2017). "Mitogenome Sequencing in the Genus Camelus Reveals Evidence for Purifying Selection and Long-term Divergence between Wild and Domestic Bactrian Camels". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 9970. Bibcode:2017NatSR...7.9970M. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-08995-8. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5577142. PMID 28855525.

- ^ Ji, R; Cui, P; Ding, F; Geng, J; Gao, H; Zhang, H; Yu, J; Hu, S; Meng, H (August 2009). "Monophyletic origin of domestic bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus) and its evolutionary relationship with the extant wild camel (Camelus bactrianus ferus)". Animal Genetics. 40 (4): 377–382. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2052.2008.01848.x. ISSN 0268-9146. PMC 2721964. PMID 19292708.

- ^ Stanley, H. F.; Kadwell, M.; Wheeler, J. C. (1994). "Molecular Evolution of the Family Camelidae: A Mitochondrial DNA Study". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 256 (1345): 1–6. Bibcode:1994RSPSB.256....1S. doi:10.1098/rspb.1994.0041. PMID 8008753. S2CID 40857282.

- ^ Skidmore, J. A.; Billah, M.; Binns, M.; Short, R. V.; Allen, W. R. (1999). "Hybridizing Old and New World camelids: Camelus dromedarius x Lama guanicoe". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 266 (1420): 649–56. doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0685. PMC 1689826. PMID 10331286.

- ^ "Meet Rama the cama ..." BBC. 21 January 1998. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ^ a b Fahmy, Miral (21 March 2002). "'Cama' camel/llama hybrids born in UAE research centre". Science in the News. The Royal Society of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ^ Campbell, Duncan (15 July 2002). "Bad karma for cross llama without a hump". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 26 August 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

- ^ "Joy for world's first camel and llama cross". Metro UK. 6 April 2008. Archived from the original on 25 November 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ^ a b Harington, C. R. (June 1997). "Ice Age Yukon and Alaskan Camels". Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre. Government of Yukon, Department of Tourism and Culture, Museums Unit. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- ^ a b Bernstein, William J. (6 May 2009). A Splendid Exchange: How Trade Shaped the World. Grove Press. pp. 54–55. ISBN 9780802144164.

- ^ "Poebrotherium" (PDF). North Dakota Industrial Commission Department of Mineral Resources. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- ^ "Fossil camel skull (Poebrotherium sp.)". Science Buzz. Science Museum of Minnesota. January 2004. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- ^ Kindersley, Dorling (2 June 2008). "Camels". Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Life. Penguin. pp. 266–7. ISBN 9780756682415.

- ^ Lynch, Sinéad; Sánchez-Villagra, Marcelo R.; Balcarcel, Ana (December 2020). "Description of a fossil camelid from the Pleistocene of Argentina, and a cladistic analysis of the Camelinae". Swiss Journal of Palaeontology. 139 (1): 5. Bibcode:2020SwJP..139....8L. doi:10.1186/s13358-020-00208-6. ISSN 1664-2376. PMC 7590954. PMID 33133011.

- ^ Heintzman, Peter D.; Zazula, Grant D.; Cahill, James A.; Reyes, Alberto V.; MacPhee, Ross D.E.; Shapiro, Beth (September 2015). "Genomic Data from Extinct North American Camelops Revise Camel Evolutionary History" (PDF). Molecular Biology and Evolution. 32 (9): 2433–2440. doi:10.1093/molbev/msv128. ISSN 0737-4038. PMID 26037535.

- ^ a b Rybczynski, Natalia; Gosse, John C.; Richard Harington, C.; Wogelius, Roy A.; Hidy, Alan J.; Buckley, Mike (June 2013). "Mid-Pliocene warm-period deposits in the High Arctic yield insight into camel evolution". Nature Communications. 4 (1): 1550. Bibcode:2013NatCo...4.1550R. doi:10.1038/ncomms2516. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 3615376. PMID 23462993.

- ^ Singh; Tomar. Evolutionary Biology (8th revised ed.). New Delhi: Rastogi Publications. p. 334. ISBN 9788171336395.

- ^ Buckley, Michael; Lawless, Craig; Rybczynski, Natalia (March 2019). "Collagen sequence analysis of fossil camels, Camelops and c.f. Paracamelus, from the Arctic and sub-Arctic of Plio-Pleistocene North America" (PDF). Journal of Proteomics. 194: 218–225. doi:10.1016/j.jprot.2018.11.014. PMID 30468917. S2CID 53713960.

- ^ Geraads, Denis; Didier, Gilles; Barr, Andrew; Reed, Denne; Laurin, Michel (April 2020). "The fossil record of camelids demonstrates a late divergence between Bactrian camel and dromedary=Acta Palaeontologica Polonica". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 65 (2): 251–260. doi:10.4202/app.00727.2020. eISSN 1732-2421. ISSN 0567-7920.

- ^ a b Worboys, Graeme L.; Francis, Wendy L.; Lockwood, Michael (30 March 2010). Connectivity Conservation Management: A Global Guide. Earthscan. p. 142. ISBN 9781844076048.

- ^ a b MacPhee, Ross D. E.; Sues, Hans-Dieter (30 June 1999). Extinctions in Near Time: Causes, Contexts, and Consequences. Springer. pp. 18, 20, 26. ISBN 9780306460920.

- ^ Yuan, Junxia; Hu, Jiaming; Liu, Wenhui; Chen, Shungang; Zhang, Fengli; Wang, Siren; Zhang, Zhen; Wang, Linying; Xiao, Bo; Li, Fuqiang; Hofreiter, Michael; Lai, Xulong; Westbury, Michael V.; Sheng, Guilian (May 2024). "Camelus knoblochi genome reveals the complex evolutionary history of Old World camels". Current Biology. 34 (11): 2502–2508.e5. Bibcode:2024CBio...34.2502Y. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2024.04.050. PMID 38754423.

- ^ Walker, Matt (22 July 2009). "Wild camels 'genetically unique'". Earth News. BBC. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- ^ Scarre, Chris (15 September 1993). Smithsonian Timelines of the Ancient World. London: D. Kindersley. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-56458-305-5.

Both the dromedary (the seven-humped camel of Arabia) and the Bactrian camel (the two-humped camel of Central Asia) had been domesticated since before 2000 BC.

- ^ Bulliet, Richard (20 May 1990) [1975]. The Camel and the Wheel. Morningside Book Series. Columbia University Press. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-231-07235-9.

As has already been mentioned, this type of utilization [camels pulling wagons] goes back to the earliest known period of two-humped camel domestication in the third millennium B.C.

—Note that Bulliet has many more references to early use of camels - ^ Richard, Suzanne (2003). Near Eastern Archaeology: A Reader. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575060835. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ^ Hirst, K. Kris. "Camels". About.com Archaeology. Archived from the original on 5 January 2014. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ Almathen, Faisal; Charruau, Pauline; Mohandesan, Elmira; Mwacharo, Joram M.; Orozco-terWengel, Pablo; Pitt, Daniel; Abdussamad, Abdussamad M.; Uerpmann, Margarethe; Uerpmann, Hans-Peter; De Cupere, Bea; Magee, Peter; Alnaqeeb, Majed A.; Salim, Bashir; Raziq, Abdul; Dessie, Tadelle (2016-06-14). "Ancient and modern DNA reveal dynamics of domestication and cross-continental dispersal of the dromedary". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (24): 6707–6712. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113.6707A. doi:10.1073/pnas.1519508113. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4914195. PMID 27162355.

- ^ Ming, Liang; Yuan, Liyun; Yi, Li; Ding, Guohui; Hasi, Surong; Chen, Gangliang; Jambl, Tuyatsetseg; Hedayat-Evright, Nemat; Batmunkh, Mijiddorj; Badmaevna, Garyaeva Khongr; Gan-Erdene, Tudeviin; Ts, Batsukh; Zhang, Wenbin; Zulipikaer, Azhati; Hosblig (2020-01-07). "Whole-genome sequencing of 128 camels across Asia reveals origin and migration of domestic Bactrian camels". Communications Biology. 3 (1) 1: 1–9. doi:10.1038/s42003-019-0734-6. ISSN 2399-3642. PMC 6946651. PMID 31925316.

- ^ Heide, Martin (2011). "The Domestication of the Camel: Biological, Archaeological and Inscriptional Evidence from Mesopotamia, Egypt, Israel and Arabia, and Literary Evidence from the Hebrew Bible". Ugarit-Forschungen. 42: 367–68. doi:10.13140/2.1.2090.8161.

- ^ Heide, Martin; Peters, Joris (2021). Camels in the Biblical World. Penn State Press. p. 302. ISBN 978-1-64602-169-7.

- ^ Hasson, Nir (Jan 17, 2014). "Hump stump solved: Camels arrived in region much later than biblical reference". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 30 January 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ^ a b Sapir-Hen, Lidar; Erez Ben-Yosef (2013). "The Introduction of Domestic Camels to the Southern Levant: Evidence from the Aravah Valley" (PDF). Tel Aviv. 40 (2): 277–285. doi:10.1179/033443513x13753505864089. S2CID 44282748. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 February 2014. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ^ Dias, Elizabeth (Feb 11, 2014). "The Mystery of the Bible's Phantom Camels". Time. Archived from the original on 15 February 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ Heide, Martin (2011). "The Domestication of the Camel: Biological, Archaeological and Inscriptional Evidence from Mesopotamia, Egypt, Israel and Arabia, and Literary Evidence from the Hebrew Bible". Ugarit-Forschungen. 42: 368.

- ^ Petrie, OJ (1995). Harvesting of textile animal fibres. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. ISBN 978-92-5-103759-1. Archived from the original on 15 March 2017. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ^ Cumming, Valerie; Cunnington, CW; Cunnington, PE (2010). The Dictionary of Fashion History. Oxford: Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781847887382.

- ^ Fagan, Brian M, ed. (2004). "Transportation". The Seventy Great Inventions of the Ancient World. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 150–152. ISBN 978-0-500-05130-6.[page needed]

- ^ Baum, Doug (1 November 2018). "The Art of Saddling a Camel". Saudi Aramco World. Archived from the original on 10 December 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- ^ Gabriel, Richard A. (2007). Soldiers' Lives Through History: The Ancient World. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. xvi. ISBN 9780313333484.

- ^ Bhatia, Vimal (23 July 2012). "BSF to ditch camels to ride sand scooters". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- ^ Gann, Lewis Henry; Duignan, Peter (1972). Africa and the World: An Introduction to the History of Sub-Saharan Africa from Antiquity to 1840. University Press of America. p. 156. ISBN 9780761815204.

The camel was acclimatized in Egypt long before the time of Christ and was subsequently adopted by the Berbers of the desert, who used camel cavalry to fight the Romans. The Berbers spread the use of the camel across the Sahara.

- ^ Fleming, Walter L. (February 1909). "Jefferson Davis's Camel Experiment". The Popular Science Monthly. Vol. 74, no. 8. Bonnier Corporation. p. 150. ISSN 0161-7370. Archived from the original on 2016-05-04.

Other trials of the camel were made in 1859 by Major D. H. Vinton, who used twenty-four of them in carrying burdens for a surveying party...All in all, he concluded, the camel was much superior to the mule.

- ^ a b c Mantz, John (20 April 2006). "Camels in the Cariboo". In Basque, Garnet (ed.). Frontier Days in British Columbia. Heritage House Publishing Co. pp. 51–54. ISBN 9781894384018. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016.

- ^ Southern, Pat (1 October 2007). The Roman Army: A Social and Institutional History. Oxford University Press. p. 123. ISBN 9780195328783.

- ^ Nicolle, David (26 March 1991). The Desert Frontier. Rome's Enemies. Vol. 5 (illustrated, reprint ed.). Osprey Publishing. p. 4. ISBN 9781855321663.

Nevertheless the military prowess of desert peoples impressed the Romans, who recruited large numbers as auxiliary cavalry and archers. In addition to providing the Roman Army with its best archers, the Easterners (largely Arabs but generally known as 'Syrians') served as Rome's most effective dromedarii or camel-mounted troops.

- ^ Herodotus (440). The History of Herodotus. Translated by Rawlinson, George. Archived from the original on 1 December 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2012 – via The Internet Classics Archive.

He collected together all the camels that had come in the train of his army to carry the provisions and the baggage, and taking off their loads, he mounted riders upon them accoutred as horsemen. These he commanded to advance in front of his other troops against the Lydian horse; behind them were to follow the foot soldiers, and last of all the cavalry. When his arrangements were complete, he gave his troops orders to slay all the other Lydians who came in their way without mercy, but to spare Croesus and not kill him, even if he should be seized and offer resistance. The reason why Cyrus opposed his camels to the enemy's horse was because the horse has a natural dread of the camel, and cannot abide either the sight or the smell of that animal. By this stratagem he hoped to make Croesus's horse useless to him, the horse being what he chiefly depended on for victory. The two armies then joined battle, and immediately the Lydian war-horses, seeing and smelling the camels, turned round and galloped off; and so it came to pass that all Croesus's hopes withered away.

- ^ "Cameliers and camels at war". New Zealand History online. History Group of the New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 30 August 2009. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ^ "The Posts at Benicia". The California State Military Museum. Archived from the original on 28 September 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- ^ "Vitrine N° 108 (partie droite): LES PELOTONS MEHARISTES" (in French). Musée de l'infanterie. Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ^ Hall, Bruce S. (6 June 2011). A History of Race in Muslim West Africa, 1600–1960. Cambridge University Press. p. 143. ISBN 9781107002876.

- ^ Guillaume, Philippe (16 June 2012). "L'incroyable épopée des méharistes français" [The incredible epic of the French méharistes]. BDSphère (in French). Archived from the original on 22 May 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ^ "Cameliers and camels at war". New Zealand History online. History Group of the New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 30 August 2009. pp. 1, 2, 4, 5. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ^ Woodward, David R. (2006). Hell in the Holy Land: World War I in the Middle East. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 36, 39, 43, 56, 133. ISBN 9780813123837.

- ^ Murray, Archibald James (1920). Sir Archibald Murray's despatches (June 1916 – June 1917). J.M. Dent. p. 123.

A great deal of the work of supplying the troops on both fronts has been done by the Camel Transport Corps

- ^ McGregor, Andrew James (30 May 2006). A Military History of Modern Egypt: From the Ottoman Conquest to the Ramadan War. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 215. ISBN 9780275986018.

- ^ Federal Research Division (30 June 2004). Somalia a Country Study. Area handbook series (3rd ed.). Kessinger Publishing. pp. 230–231. ISBN 9781419147999.

- ^ "Romanian troops using camels". WWII in Color. Archived from the original on 2013-09-21.

- ^ "Наш советский верблюд покарает!". WARHEAD.SU. March 2, 2020. Archived from the original on March 19, 2020. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- ^ Jupiter Infomedia Ltd (28 November 2012). "Bikaner Camel Corps, Presidency Armies in British India". IndiaNetzone.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Shelley, Toby (December 2007). "Sons of the Clouds". Red Pepper. Location. Archived from the original on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ Hermandad de Veteranos Tropas Nómadas del Sáhara. "Los Medios" [The Means]. Historia: Agrupación de Tropas Nómadas (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ "Camels banned from Saudi beauty contest over Botox". BBC News. 24 January 2018. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ Adams, Abigail (9 December 2021). "Over 40 Camels Disqualified From Beauty Contest in Saudi Arabia For Receiving Botox Injections". PEOPLE.com.

- ^ "Wild Camel – Windy Hills". Archived from the original on August 22, 2016.

- ^ a b Burin, Margaret (7 August 2015). "Australians urged to develop taste for camel meat". ABC News. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ "Australia's Growing Camel Meat Trade Reveals a Hidden History of Early Muslim Migrants". 16 May 2019.

- ^ "SAMEX : Australian Meat Exporters".

- ^ Tariq, M., Rabia, R., Jamil, A., Sakhwat, A., Aadil, A., & Muhammad S., 2010. Minerals and Nutritional Composition of Camel (Camelus Dromedarius) Meat in Pakistan. Journal- Chemical Society of Pakistan, Vol 33(6).

- ^ Bulliet, Richard W. (1975). The Camel and the Wheel. Columbia University Press. pp. 23, 25, 28, 35–36, 38–40. ISBN 9780231072359.

- ^ a b "Camel Milk". Milk & Dairy Products. FAO's Animal Production and Health Division. 25 September 2012. Archived from the original on 1 November 2012. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ Ramet. Camel milk and cheese making. Archived from the original on 2012-06-24.

- ^ "Fresh from your local drome'dairy'?". Food and Agriculture Organization. 6 July 2001. Archived from the original on 26 January 2012.

- ^ Ramet. Methods of processing camel milk into cheese. Archived from the original on 2012-06-24.

- ^ Young, Philippa. "In Mongolian the Word 'Gobi' Means 'Desert'". Archived from the original on 3 March 2013. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

As evening approaches we are offered camel meat boats, dumplings stuffed with a finely chopped mixture of meat and vegetables, followed by camel milk tea and finally, warm fresh camel's milk to aid digestion and help us sleep.

- ^ "Netherlands' 'crazy' camel farmer". BBC. 5 November 2011. Archived from the original on 6 November 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- ^ "Al Ain Dairy launches camel-milk ice cream". The National. 26 March 2015. Retrieved 2019-02-22.

- ^ "FAOSTAT". www.fao.org. Retrieved 2019-10-25.

- ^ a b c Yagil. Camels Products Other Than Milk. Archived from the original on 2011-02-20.

- ^ Madame Guinaudeau (2003). Traditional Moroccan Cooking: Recipes from Fez. London: Serif. ISBN 978-1-897959-43-5.

- ^ Aleme, A., D., 2013. A Review of Camel Meat as a Precious Source of Nutrition in some part of Ethiopia. Agricultural Science, Engineering and Technology Research. Vol. 1, No. 4, December 2013, PP: 40–43. Available online at "Agricultural Science, Engineering and Technology Research". Archived from the original on 2016-12-03. Retrieved 2016-12-03..

- ^ Rubenstein, Dustin (23 July 2010). "How to Cook Camel". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

He cut the pieces very small and cooked them for a long time. I decided to try something a bit different the following night and cut the pieces a bit bigger and cooked them for less time, as I like my meat rarer than he does. This was a bad idea. It seems that the more you cook camel, the more tender it becomes. So we had what amounted to two pounds or more of rubber for dinner that night.

- ^ "Eid al-Adha: More than just slaughtering animals". Daily Sabah. 2017-09-01. Retrieved 2022-10-04.

- ^ "Qurbani Meat Distribution Rules". Muslim Aid. Retrieved 2022-10-04.

- ^ Arthur, Rick (4 January 2012). "The Instant Expert: camels, the ships of the desert". The National. UAE: Abu Dhabi Media.

As the meat can be dry, however, the Abu Dhabi Officer's Club, for one, serves camel burger with beef or lamb fat mixed in, improving texture and taste.

- ^ Jasra, Abdel Wahid; Isani, G. B.; Camel Applied Research and Development Network (2000). Socio-economics of camel herders in Pakistan. The Camel Applied Research and Development Network. p. 164. Archived from the original on 2016-06-10.

- ^ Anyone for camel meat? One hump or two? Archived 2017-01-26 at the Wayback MachineThe Guardian, Word of Mouth

- ^ a b Sherwood, Andy (17 September 2012). "Camel burgers in Abu Dhabi". Time Out Abu Dhabi. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ^ a b c Webster, George (9 February 2010). "Dubai diners flock to eat new 'camel burger'". CNN World. CNN. Archived from the original on 29 September 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ^ Bin Saeed, Abdulaziz A.; Al-Hamdan, Nasser A.; Fontaine, Robert E. (2005). "Plague from eating raw camel liver". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (9): 1456–7. doi:10.3201/eid1109.050081. PMC 3310619. PMID 16229781.

- ^ McBride, Louise (14 June 2010). "SA hits world camel meat supply hump". Stock Journal. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ Bazckowski, Halina (22 March 2020). "The beasts that beat the drought: Camels sought after for meat, milk and cheese". ABC News. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ a b "Book 1, Number 0184". Purification (Kitab al-Taharah). Partial Translation of Sunan Abu-Dawud, Book 1. Center for Muslim-Jewish Engagement. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011.

Narrated Al-Bara' ibn Azib: The Messenger of Allah (peace_be_upon_him) was asked about performing ablution after eating the flesh of the camel. He replied: Perform ablution, after eating it. He was asked about performing ablution after eating meat. He replied: Do not perform ablution after eating it. He was asked about saying prayer in places where the camels lie down. He replied: Do not offer prayer in places where the camels lie down. These are the places of Satan. He was asked about saying prayer in the sheepfolds. He replied: You may offer prayer in such places; these are the places of blessing.

- ^ Williams, John Alden (1994). The Word of Islam. University of Texas Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-292-79076-6. Archived from the original on 8 April 2017. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- ^ Campo, Juan Eduardo (2009). Encyclopedia of Islam. Infobase Publishing. p. 128.

- ^ Heinemann, Moshe (2013-08-20). "Cholov Yisroel: Does a Neshama Good". Kashrus Kurrents. Star-K. Archived from the original on 30 April 2017. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- ^ http://www.chabad.org/library/bible_cdo/aid/9912#v=41 Archived 2015-02-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ben-Zvi, Itzhak (1967). שאר ישוב: מאמרים ופרקים בדברי ימי הישוב העברי בא"י ובחקר המולדת [She'ar Yeshuv] (in Hebrew). תל אביב תרפ"ז. pp. 407–413.

- ^ Sar-Avi, Doron (2019). "מניין באו הערבים 'היהודים'?". Segula Magazine. Retrieved 2024-02-18.

- ^ Saudi Arabia camel carvings dated to prehistoric era Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine, BBC, September 15, 2021

- ^ a b c Dolby, Karen (10 August 2010). You Must Remember This: Easy Tricks & Proven Tips to Never Forget Anything, Ever Again. Random House Digital, Inc. p. 170. ISBN 9780307716255.

- ^ Abokor, Axmed Cali (1987). The Camel in Somali Oral Tradition. Nordic Africa Institute. pp. 7, 10–11. ISBN 9789171062697.

- ^ "Drought threatening Somali nomads, UN humanitarian office says". UN News Centre. 14 November 2003. Archived from the original on 19 November 2011. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

A four-year drought is threatening the lives of Somali nomads, and those of the camel herds on which they depend for transportation and milk

- ^ Farah, K. O.; Nyariki, D. M.; Ngugi, R. K.; Noor, I. M.; Guliye, A. Y. (2004). "The Somali and the Camel: Ecology, Management and Economics". Anthropologist. 6 (1): 45–55. doi:10.1080/09720073.2004.11890828. S2CID 4980638.

Somali pastoralists are a camel community...There is no other community in the world where the camel plays such a pivotal role in the local economy and culture as in the Somali community. According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO, 1979) estimates, there are approximately 15 million dromedary camels in the world

Plain text version. Archived 2013-01-02 at the Wayback Machine - ^ "Feral camel". Northern Territory government. 17 August 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ Pople, A. R.; McLeod, S. R. (2010). "Demography of feral camels in central Australia and its relevance to population control". The Rangeland Journal. 32 (1): 11. Bibcode:2010RangJ..32...11P. doi:10.1071/RJ09053. S2CID 83822347. Archived from the original on Mar 29, 2024 – via DAF eResearch Archive.

- ^ Saalfeld, W.K.; Edwards, GP (2008). "Ecology of feral camels in Australia" (PDF). Managing the impacts of feral camels in Australia: a new way of doing business. Alice Springs: Desert Knowledge Cooperative Research Centre. ISBN 978-1-74158-094-5. ISSN 1832-6684. Report 47. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-29. Retrieved 2011-12-25.

- ^ Tsai, Vivian (14 September 2012). "Australia Culls 100,000 Feral Camels To Limit Environmental Damage, Many More Will Be Killed". International Business Times. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ^ "Bactrian Camel" (PDF). Denver Zoo. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ^ Jemmett, Anna M.; Groombridge, Jim J.; Hare, John; Yadamsuren, Adiya; Burger, Pamela A.; Ewen, John G. (March 2023). "What's in a name? Common name misuse potentially confounds the conservation of the wild camel Camelus ferus". Oryx. 57 (2): 175–179. doi:10.1017/S0030605322000114. ISSN 0030-6053.

Bibliography

- Camels and Camel Milk. Report Issued by Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (1982)

- Ramet, J. P. (2011). The technology of making cheese from camel milk (Camelus dromedarius). FAO Animal Production and Health Paper. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. ISBN 978-92-5-103154-4. ISSN 0254-6019. OCLC 476039542. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- Vannithone, S.; Davidson, A. (1999). "Camel". The Oxford companion to food. Oxford Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-19-211579-9.

- Wilson, R.T. (1984). The camel. New York: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-77512-1.

- Yagil, R. (1982). Camels and Camel Milk. FAO Animal Production and Health Paper. Vol. 26. Rome: Food And Agriculture Organization Of The United Nations. ISBN 978-92-5-101169-0. ISSN 0254-6019.

Further reading

- Gilchrist, W. (1851). A Practical Treatise on the Treatment of the Diseases of the Elephant, Camel & Horned Cattle: with instructions for improving their efficiency; also, a description of the medicines used in the treatment of their diseases; and a general outline of their anatomy. Calcutta, India: Military Orphan Press.