Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Interferon

View on Wikipedia

| Interferon | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Interferons | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00143 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR000471 | ||||||||

| SMART | SM00076 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00225 | ||||||||

| CATH | 1au0 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1au1 / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| CDD | cd00095 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Interferon type II (γ) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

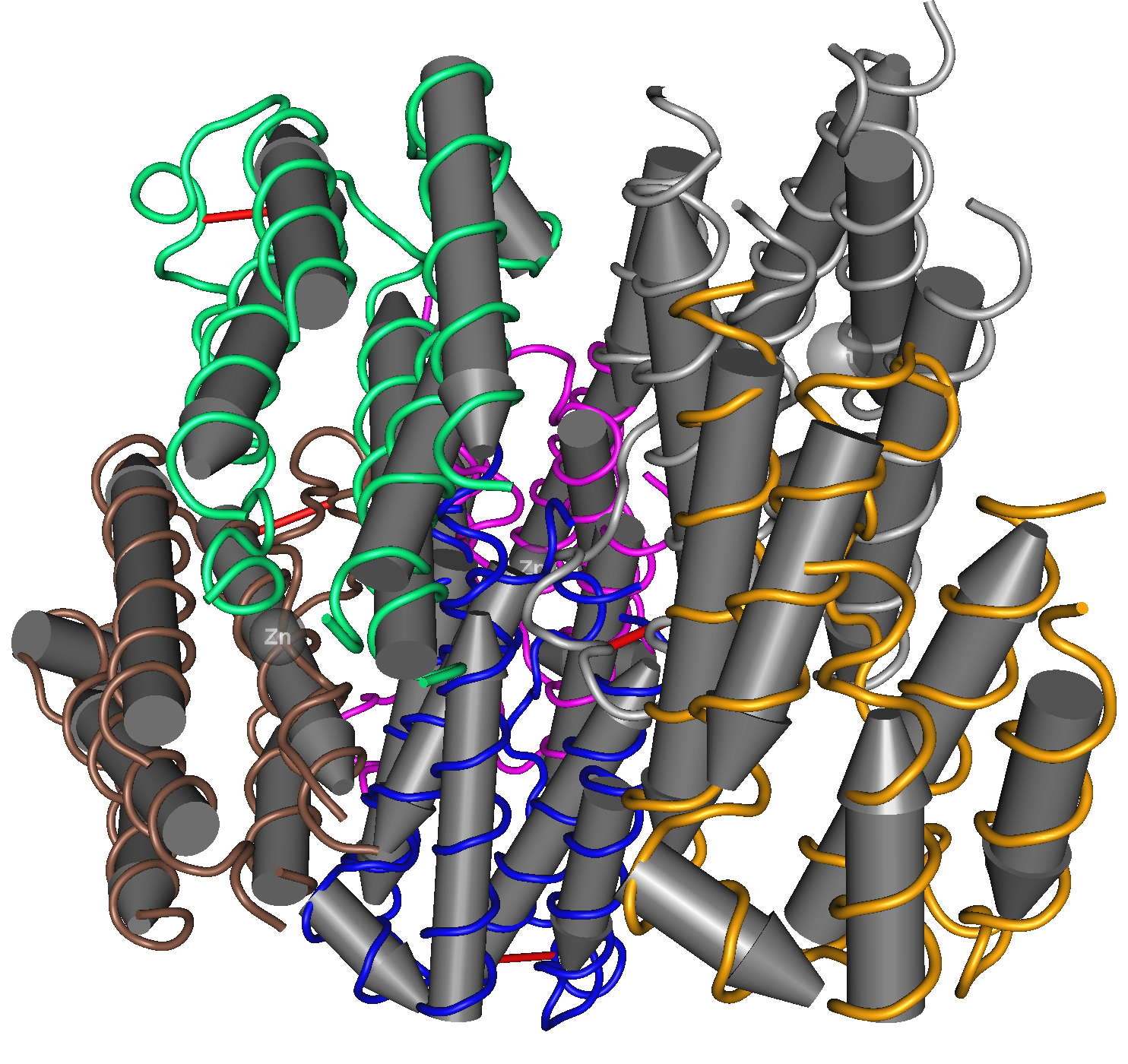

The three-dimensional structure of human interferon gamma (PDB: 1HIG) | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | IFN-gamma | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00714 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR002069 | ||||||||

| CATH | 1d9cA00 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | d1d9ca_ / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Interferon type III (λ) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | IL28A | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF15177 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR029177 | ||||||||

| CATH | 3og6A00 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Interferons (IFNs, /ˌɪntərˈfɪərɒn/ IN-tər-FEER-on[1]) are a group of signaling proteins[2] made and released by host cells in response to the presence of several viruses. In a typical scenario, a virus-infected cell will release interferons causing nearby cells to heighten their anti-viral defenses.

IFNs belong to the large class of proteins known as cytokines, molecules used for communication between cells to trigger the protective defenses of the immune system that help eradicate pathogens.[3] Interferons are named for their ability to "interfere" with viral replication[3] by protecting cells from virus infections. However, virus-encoded genetic elements have the ability to antagonize the IFN response, contributing to viral pathogenesis and viral diseases.[4] IFNs also have various other functions: they activate immune cells, such as natural killer cells and macrophages, and they increase host defenses by up-regulating antigen presentation by virtue of increasing the expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) antigens. Certain symptoms of infections, such as fever, muscle pain and "flu-like symptoms", are also caused by the production of IFNs and other cytokines.

More than twenty distinct IFN genes and proteins have been identified in animals, including humans. They are typically divided among three classes: Type I IFN, Type II IFN, and Type III IFN. IFNs belonging to all three classes are important for fighting viral infections and for the regulation of the immune system.

Types of interferon

[edit]Based on the type of receptor through which they signal, human interferons have been classified into three major types.

- Interferon type I: All type I IFNs bind to a specific cell surface receptor complex known as the IFN-α/β receptor (IFNAR) that consists of IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 chains.[5] The type I interferons present in humans are IFN-α, IFN-β, IFN-ε, IFN-κ and IFN-ω.[6] Interferon beta (IFN-β) can be produced by all nucleated cells when they recognize that a virus has invaded them. The most prolific producers of IFN-α and IFN-β are plasmacytoid dendritic cells circulating in the blood. Monocytes and macrophages can also produce large amounts of type I interferons when stimulated by viral molecular patterns. The production of type I IFN-α is inhibited by another cytokine known as Interleukin-10. Once released, type I interferons bind to the IFN-α/β receptor on target cells, which leads to expression of proteins that will prevent the virus from producing and replicating its RNA and DNA.[7] Overall, IFN-α can be used to treat hepatitis B and C infections, while IFN-β can be used to treat multiple sclerosis.[3]

- Interferon type II (IFN-γ in humans): This is also known as immune interferon and is activated by Interleukin-12.[3] Type II interferons are also released by cytotoxic T cells and type-1 T helper cells. However, they block the proliferation of type-2 T helper cells. The previous results in an inhibition of Th2 immune response and a further induction of Th1 immune response.[8] IFN type II binds to IFNGR, which consists of IFNGR1 and IFNGR2 chains.[3]

- Interferon type III: Signal through a receptor complex consisting of IL10R2 (also called CRF2-4) and IFNLR1 (also called CRF2-12). Although discovered more recently than type I and type II IFNs,[9] recent information demonstrates the importance of Type III IFNs in some types of virus or fungal infections.[10][11][12]

In general, type I and II interferons are responsible for regulating and activating the immune response.[3] Expression of type I and III IFNs can be induced in virtually all cell types upon recognition of viral components, especially nucleic acids, by cytoplasmic and endosomal receptors, whereas type II interferon is induced by cytokines such as IL-12, and its expression is restricted to immune cells such as T cells and NK cells.[13]

Function

[edit]All interferons share several common effects: they are antiviral agents and they modulate functions of the immune system. Administration of Type I IFN has been shown experimentally to inhibit tumor growth in animals, but the beneficial action in human tumors has not been widely documented. A virus-infected cell releases viral particles that can infect nearby cells. However, the infected cell can protect neighboring cells against a potential infection of the virus by releasing interferons. In response to interferon, cells produce large amounts of an enzyme known as protein kinase R (PKR). This enzyme phosphorylates a protein known as eIF-2 in response to new viral infections; the phosphorylated eIF-2 forms an inactive complex with another protein, called eIF2B, to reduce protein synthesis within the cell. Another cellular enzyme, RNAse L—also induced by interferon action—destroys RNA within the cells to further reduce protein synthesis of both viral and host genes. Inhibited protein synthesis impairs both virus replication and infected host cells. In addition, interferons induce production of hundreds of other proteins—known collectively as interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs)—that have roles in combating viruses and other actions produced by interferon.[14][15] They also limit viral spread by increasing p53 activity, which kills virus-infected cells by promoting apoptosis.[16][17] The effect of IFN on p53 is also linked to its protective role against certain cancers.[16]

Another function of interferons is to up-regulate major histocompatibility complex molecules, MHC I and MHC II, and increase immunoproteasome activity. All interferons significantly enhance the presentation of MHC I dependent antigens. Interferon gamma (IFN-gamma) also significantly stimulates the MHC II-dependent presentation of antigens. Higher MHC I expression increases presentation of viral and abnormal peptides from cancer cells to cytotoxic T cells, while the immunoproteasome processes these peptides for loading onto the MHC I molecule, thereby increasing the recognition and killing of infected or malignant cells. Higher MHC II expression increases presentation of these peptides to helper T cells; these cells release cytokines (such as more interferons and interleukins, among others) that signal to and co-ordinate the activity of other immune cells.[18][19][20]

Interferons can also suppress angiogenesis by down regulation of angiogenic stimuli deriving from tumor cells. They also suppress the proliferation of endothelial cells. Such suppression causes a decrease in tumor angiogenesis, a decrease in its vascularization and subsequent growth inhibition. Interferons, such as interferon gamma, directly activate other immune cells, such as macrophages and natural killer cells.[18][19][20]

Induction of interferons

[edit]Production of interferons occurs mainly in response to microbes, such as viruses and bacteria, and their products. Binding of molecules uniquely found in microbes—viral glycoproteins, viral RNA, bacterial endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide), bacterial flagella, CpG motifs—by pattern recognition receptors, such as membrane bound toll like receptors or the cytoplasmic receptors RIG-I or MDA5, can trigger release of IFNs. Toll Like Receptor 3 (TLR3) is important for inducing interferons in response to the presence of double-stranded RNA viruses; the ligand for this receptor is double-stranded RNA (dsRNA). After binding dsRNA, this receptor activates the transcription factors IRF3 and NF-κB, which are important for initiating synthesis of many inflammatory proteins. RNA interference technology tools such as siRNA or vector-based reagents can either silence or stimulate interferon pathways.[21] Release of IFN from cells (specifically IFN-γ in lymphoid cells) is also induced by mitogens. Other cytokines, such as interleukin 1, interleukin 2, interleukin-12, tumor necrosis factor and colony-stimulating factor, can also enhance interferon production.[22]

Downstream signaling

[edit]By interacting with their specific receptors, IFNs activate signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) complexes; STATs are a family of transcription factors that regulate the expression of certain immune system genes. Some STATs are activated by both type I and type II IFNs. However each IFN type can also activate unique STATs.[23]

STAT activation initiates the most well-defined cell signaling pathway for all IFNs, the classical Janus kinase-STAT (JAK-STAT) signaling pathway.[23] In this pathway, JAKs associate with IFN receptors and, following receptor engagement with IFN, phosphorylate both STAT1 and STAT2. As a result, an IFN-stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3) complex forms—this contains STAT1, STAT2 and a third transcription factor called IRF9—and moves into the cell nucleus. Inside the nucleus, the ISGF3 complex binds to specific nucleotide sequences called IFN-stimulated response elements (ISREs) in the promoters of certain genes, known as IFN stimulated genes ISGs. Binding of ISGF3 and other transcriptional complexes activated by IFN signaling to these specific regulatory elements induces transcription of those genes.[23] A collection of known ISGs is available on Interferome, a curated online database of ISGs (www.interferome.org);[24] Additionally, STAT homodimers or heterodimers form from different combinations of STAT-1, -3, -4, -5, or -6 during IFN signaling; these dimers initiate gene transcription by binding to IFN-activated site (GAS) elements in gene promoters.[23] Type I IFNs can induce expression of genes with either ISRE or GAS elements, but gene induction by type II IFN can occur only in the presence of a GAS element.[23]

In addition to the JAK-STAT pathway, IFNs can activate several other signaling cascades. For instance, both type I and type II IFNs activate a member of the CRK family of adaptor proteins called CRKL, a nuclear adaptor for STAT5 that also regulates signaling through the C3G/Rap1 pathway.[23] Type I IFNs further activate p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAP kinase) to induce gene transcription.[23] Antiviral and antiproliferative effects specific to type I IFNs result from p38 MAP kinase signaling. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling pathway is also regulated by both type I and type II IFNs. PI3K activates P70-S6 Kinase 1, an enzyme that increases protein synthesis and cell proliferation; phosphorylates ribosomal protein s6, which is involved in protein synthesis; and phosphorylates a translational repressor protein called eukaryotic translation-initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 (EIF4EBP1) in order to deactivate it.[23]

Interferons can disrupt signaling by other stimuli. For example, interferon alpha induces RIG-G, which disrupts the CSN5-containing COP9 signalosome (CSN), a highly conserved multiprotein complex implicated in protein deneddylation, deubiquitination, and phosphorylation.[25] RIG-G has shown the capacity to inhibit NF-κB and STAT3 signaling in lung cancer cells, which demonstrates the potential of type I IFNs.[26]

Viral resistance to interferons

[edit]Many viruses have evolved mechanisms to resist interferon activity.[27] They circumvent the IFN response by blocking downstream signaling events that occur after the cytokine binds to its receptor, by preventing further IFN production, and by inhibiting the functions of proteins that are induced by IFN.[28] Viruses that inhibit IFN signaling include Japanese Encephalitis Virus (JEV), dengue type 2 virus (DEN-2), and viruses of the herpesvirus family, such as human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) and Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV or HHV8).[28][29] Viral proteins proven to affect IFN signaling include EBV nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1) and EBV nuclear antigen 2 (EBNA-2) from Epstein-Barr virus, the large T antigen of Polyomavirus, the E7 protein of Human papillomavirus (HPV), and the B18R protein of vaccinia virus.[29][30] Reducing IFN-α activity may prevent signaling via STAT1, STAT2, or IRF9 (as with JEV infection) or through the JAK-STAT pathway (as with DEN-2 infection).[28] Several poxviruses encode soluble IFN receptor homologs—like the B18R protein of the vaccinia virus—that bind to and prevent IFN interacting with its cellular receptor, impeding communication between this cytokine and its target cells.[30] Some viruses can encode proteins that bind to double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) to prevent the activity of RNA-dependent protein kinases; this is the mechanism reovirus adopts using its sigma 3 (σ3) protein, and vaccinia virus employs using the gene product of its E3L gene, p25.[31][32][33] The ability of interferon to induce protein production from interferon stimulated genes (ISGs) can also be affected. Production of protein kinase R, for example, can be disrupted in cells infected with JEV.[28] Some viruses escape the anti-viral activities of interferons by gene (and thus protein) mutation. The H5N1 influenza virus, also known as bird flu, has resistance to interferon and other anti-viral cytokines that is attributed to a single amino acid change in its Non-Structural Protein 1 (NS1), although the precise mechanism of how this confers immunity is unclear.[34] The relative resistance of hepatitis C virus genotype I to interferon-based therapy has been attributed in part to homology between viral envelope protein E2 and host protein kinase R, a mediator of interferon-induced suppression of viral protein translation,[35][36] although mechanisms of acquired and intrinsic resistance to interferon therapy in HCV are polyfactorial.[37][38]

Coronavirus response

[edit]Coronaviruses evade innate immunity during the first ten days of viral infection.[39] In the early stages of infection, SARS-CoV-2 induces an even lower interferon type I (IFN-I) response than SARS-CoV, which itself is a weak IFN-I inducer in human cells.[39][40] SARS-CoV-2 limits the IFN-III response as well.[41] Reduced numbers of plasmacytoid dendritic cells with age is associated with increased COVID-19 severity, possibly because these cells are substantial interferon producers.[42]

Ten percent of patients with life-threatening COVID-19 have autoantibodies against type I interferon.[42]

Delayed IFN-I response contributes to the pathogenic inflammation (cytokine storm) seen in later stages of COVID-19 disease.[43] Application of IFN-I prior to (or in the very early stages of) viral infection can be protective,[39] which should be validated in randomized clinical trials.[43]

With pegylated IFN lambda, the relative risk for hospitalization with the Omicron strains is reduced by about 80 %.[44]

Interferon therapy

[edit]

Diseases

[edit]Interferon beta-1a and interferon beta-1b are used to treat and control multiple sclerosis, an autoimmune disorder. This treatment may help in reducing attacks in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis[45] and slowing disease progression and activity in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis.[46]

Interferon therapy is used (in combination with chemotherapy and radiation) as a treatment for some cancers.[47] This treatment can be used in hematological malignancy, such as in leukemia and lymphomas including hairy cell leukemia, chronic myeloid leukemia, nodular lymphoma, and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.[47] Patients with recurrent melanomas receive recombinant IFN-α2b.[48]

Both hepatitis B and hepatitis C can be treated with IFN-α, often in combination with other antiviral drugs.[49][50] Some of those treated with interferon have a sustained virological response and can eliminate hepatitis virus in the case of hepatitis C. The most common strain of hepatitis C virus (HCV) worldwide—genotype I—[51] can be treated with interferon-α, ribavirin and protease inhibitors such as telaprevir,[52] boceprevir[53][54] or the nucleotide analog polymerase inhibitor sofosbuvir.[55] Biopsies of patients given the treatment show reductions in liver damage and cirrhosis. Control of chronic hepatitis C by IFN is associated with reduced hepatocellular carcinoma.[56] A single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the gene encoding the type III interferon IFN-λ3 was found to be protective against chronic infection following proven HCV infection[57] and predicted treatment response to interferon-based regimens. The frequency of the SNP differed significantly by race, partly explaining observed differences in response to interferon therapy between European-Americans and African-Americans.[58]

Unconfirmed results suggested that interferon eye drops may be an effective treatment for people who have herpes simplex virus epithelial keratitis, a type of eye infection.[59] There is no clear evidence to suggest that removing the infected tissue (debridement) followed by interferon drops is an effective treatment approach for these types of eye infections.[59] Unconfirmed results suggested that the combination of interferon and an antiviral agent may speed the healing process compared to antiviral therapy alone.[59]

When used in systemic therapy, IFNs are mostly administered by an intramuscular injection. The injection of IFNs in the muscle or under the skin is generally well tolerated. The most frequent adverse effects are flu-like symptoms: increased body temperature, feeling ill, fatigue, headache, muscle pain, convulsion, dizziness, hair thinning, and depression. Erythema, pain, and hardness at the site of injection are also frequently observed. IFN therapy causes immunosuppression, in particular through neutropenia and can result in some infections manifesting in unusual ways.[60]

Drug formulations

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2021) |

| Generic name | Brand name |

|---|---|

| Interferon alfa | Multiferon |

| Interferon alpha 2a | Roferon A |

| Interferon alpha 2b | Intron A/Reliferon/Uniferon |

| Human leukocyte Interferon-alpha (HuIFN-alpha-Le) | Multiferon |

| Interferon beta 1a, liquid form | Rebif |

| Interferon beta 1a, lyophilized | Avonex |

| Interferon beta 1a, biogeneric (Iran) | Cinnovex |

| Interferon beta 1b | Betaseron / Betaferon |

| Interferon gamma 1b | Actimmune |

| PEGylated interferon alpha 2a | Pegasys |

| PEGylated interferon alpha 2a (Egypt) | Reiferon Retard |

| PEGylated interferon alpha 2b | PegIntron |

| Ropeginterferon alfa-2b | Besremi |

| PEGylated interferon alpha 2b plus ribavirin (Canada) | Pegetron |

Several different types of interferons are approved for use in humans. One was first approved for medical use in 1986.[61] For example, in January 2001, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the use of PEGylated interferon-alpha in the USA; in this formulation, PEGylated interferon-alpha-2b (Pegintron), polyethylene glycol is linked to the interferon molecule to make the interferon last longer in the body. Approval for PEGylated interferon-alpha-2a (Pegasys) followed in October 2002. These PEGylated drugs are injected once weekly, rather than administering two or three times per week, as is necessary for conventional interferon-alpha. When used with the antiviral drug ribavirin, PEGylated interferon is effective in treatment of hepatitis C; at least 75% of people with hepatitis C genotypes 2 or 3 benefit from interferon treatment, although this is effective in less than 50% of people infected with genotype 1 (the more common form of hepatitis C virus in both the U.S. and Western Europe).[62][63][64] Interferon-containing regimens may also include protease inhibitors such as boceprevir and telaprevir.

There are also interferon-inducing drugs, notably tilorone[65] that is shown to be effective against Ebola virus.[66]

History

[edit]

Interferons were first described in 1957 by Alick Isaacs and Jean Lindenmann at the National Institute for Medical Research in London;[67][68][69] the discovery was a result of their studies of viral interference. Viral interference refers to the inhibition of virus growth caused by previous exposure of cells to an active or a heat-inactivated virus. Isaacs and Lindenmann were working with a system that involved the inhibition of the growth of live influenza virus in chicken embryo chorioallantoic membranes by heat-inactivated influenza virus. Their experiments revealed that this interference was mediated by a protein released by cells in the heat-inactivated influenza virus-treated membranes. They published their results in 1957 naming the antiviral factor they had discovered interferon.[68] The findings of Isaacs and Lindenmann have been widely confirmed and corroborated in the literature.[70]

Furthermore, others may have made observations on interferons before the 1957 publication of Isaacs and Lindenmann. For example, during research to produce a more efficient vaccine for smallpox, Yasu-ichi Nagano and Yasuhiko Kojima—two Japanese virologists working at the Institute for Infectious Diseases at the University of Tokyo—noticed inhibition of viral growth in an area of rabbit-skin or testis previously inoculated with UV-inactivated virus. They hypothesised that some "viral inhibitory factor" was present in the tissues infected with virus and attempted to isolate and characterize this factor from tissue homogenates.[71] Independently, Monto Ho, in John Enders's lab, observed in 1957 that attenuated poliovirus conferred a species specific anti-viral effect in human amniotic cell cultures. They described these observations in a 1959 publication, naming the responsible factor viral inhibitory factor (VIF).[72] It took another fifteen to twenty years, using somatic cell genetics, to show that the interferon action gene and interferon gene reside in different human chromosomes.[73][74][75] The purification of human beta interferon did not occur until 1977. Y.H. Tan and his co-workers purified and produced biologically active, radio-labeled human beta interferon by superinducing the interferon gene in fibroblast cells, and they showed its active site contains tyrosine residues.[76][77] Tan's laboratory isolated sufficient amounts of human beta interferon to perform the first amino acid, sugar composition and N-terminal analyses.[78] They showed that human beta interferon was an unusually hydrophobic glycoprotein. This explained the large loss of interferon activity when preparations were transferred from test tube to test tube or from vessel to vessel during purification. The analyses showed the reality of interferon activity by chemical verification.[78][79][80][81] The purification of human alpha interferon was not reported until 1978. A series of publications from the laboratories of Sidney Pestka and Alan Waldman between 1978 and 1981, describe the purification of the type I interferons IFN-α and IFN-β.[69] By the early 1980s, genes for these interferons had been cloned, adding further definitive proof that interferons were responsible for interfering with viral replication.[82][83] Gene cloning also confirmed that IFN-α was encoded by a family of many related genes.[84] The type II IFN (IFN-γ) gene was also isolated around this time.[85]

Interferon was first synthesized manually at Rockefeller University in the lab of Dr. Bruce Merrifield, using solid phase peptide synthesis, one amino acid at a time. He later won the Nobel Prize in chemistry. Interferon was scarce and expensive until 1980, when the interferon gene was inserted into bacteria using recombinant DNA technology, allowing mass cultivation and purification from bacterial cultures[86] or derived from yeasts. Interferon can also be produced by recombinant mammalian cells.[87] Before the early 1970s, large scale production of human interferon had been pioneered by Kari Cantell. He produced large amounts of human alpha interferon from large quantities of human white blood cells collected by the Finnish Blood Bank.[88] Large amounts of human beta interferon were made by superinducing the beta interferon gene in human fibroblast cells.[89][90]

Cantell's and Tan's methods of making large amounts of natural interferon were critical for chemical characterisation, clinical trials and the preparation of small amounts of interferon messenger RNA to clone the human alpha and beta interferon genes. The superinduced human beta interferon messenger RNA was prepared by Tan's lab for Cetus. to clone the human beta interferon gene in bacteria and the recombinant interferon was developed as 'betaseron' and approved for the treatment of MS. Superinduction of the human beta interferon gene was also used by Israeli scientists to manufacture human beta interferon.

Human interferons

[edit]Teleost fish interferons

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Interferon | Definition of Interferon by Lexico". Archived from the original on 2020-12-22. Retrieved 2019-10-17.

- ^ De Andrea M, Ravera R, Gioia D, Gariglio M, Landolfo S (2002). "The interferon system: an overview". European Journal of Paediatric Neurology. 6 (6 Suppl A): A41–6, discussion A55–8. doi:10.1053/ejpn.2002.0573. PMID 12365360. S2CID 4523675.

- ^ a b c d e f Parkin J, Cohen B (June 2001). "An overview of the immune system". Lancet. 357 (9270): 1777–1789. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04904-7. PMID 11403834. S2CID 165986.

- ^ Elrefaey AM, Hollinghurst P, Reitmayer CM, Alphey L, Maringer K (October 2021). "Innate Immune Antagonism of Mosquito-Borne Flaviviruses in Humans and Mosquitoes". Viruses. 13 (11): 2116. doi:10.3390/v13112116. PMC 8624719. PMID 34834923.

- ^ de Weerd NA, Samarajiwa SA, Hertzog PJ (July 2007). "Type I interferon receptors: biochemistry and biological functions". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 282 (28): 20053–20057. doi:10.1074/jbc.R700006200. PMID 17502368.

- ^ a b Liu YJ (2005). "IPC: professional type 1 interferon-producing cells and plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors". Annual Review of Immunology. 23: 275–306. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115633. PMID 15771572.

- ^ Levy DE, Marié IJ, Durbin JE (December 2011). "Induction and function of type I and III interferon in response to viral infection". Current Opinion in Virology. 1 (6): 476–486. doi:10.1016/j.coviro.2011.11.001. PMC 3272644. PMID 22323926.

- ^ Kidd P (August 2003). "Th1/Th2 balance: the hypothesis, its limitations, and implications for health and disease". Alternative Medicine Review. 8 (3): 223–246. PMID 12946237.

- ^ Kalliolias GD, Ivashkiv LB (2010). "Overview of the biology of type I interferons". Arthritis Research & Therapy. 12 (Suppl 1): S1. doi:10.1186/ar2881. PMC 2991774. PMID 20392288.

- ^ Vilcek, Novel interferons, Nature Immunol. 4, 8-9. 2003

- ^ Hermant P, Michiels T (2014). "Interferon-λ in the context of viral infections: production, response and therapeutic implications". Journal of Innate Immunity. 6 (5): 563–574. doi:10.1159/000360084. PMC 6741612. PMID 24751921.

- ^ Espinosa V, Dutta O, McElrath C, Du P, Chang YJ, Cicciarelli B, et al. (October 2017). "Type III interferon is a critical regulator of innate antifungal immunity". Science Immunology. 2 (16) eaan5357. doi:10.1126/sciimmunol.aan5357. PMC 5880030. PMID 28986419.

- ^ Levy DE, Marié IJ, Durbin JE (2011). "Induction and function of type I and III interferon in response to viral infection". Current Opinion in Virology. 1 (6): 476–486. doi:10.1016/j.coviro.2011.11.001. ISSN 1879-6257. PMC 3272644. PMID 22323926.

- ^ Fensterl V, Sen GC (2009). "Interferons and viral infections". BioFactors. 35 (1): 14–20. doi:10.1002/biof.6. PMID 19319841. S2CID 27209861.

- ^ de Veer MJ, Holko M, Frevel M, Walker E, Der S, Paranjape JM, et al. (June 2001). "Functional classification of interferon-stimulated genes identified using microarrays". Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 69 (6): 912–920. doi:10.1189/jlb.69.6.912. PMID 11404376. S2CID 1714991.

- ^ a b Takaoka A, Hayakawa S, Yanai H, Stoiber D, Negishi H, Kikuchi H, et al. (July 2003). "Integration of interferon-alpha/beta signalling to p53 responses in tumour suppression and antiviral defence". Nature. 424 (6948): 516–523. Bibcode:2003Natur.424..516T. doi:10.1038/nature01850. PMID 12872134.

- ^ Moiseeva O, Mallette FA, Mukhopadhyay UK, Moores A, Ferbeyre G (April 2006). "DNA damage signaling and p53-dependent senescence after prolonged beta-interferon stimulation". Molecular Biology of the Cell. 17 (4): 1583–1592. doi:10.1091/mbc.E05-09-0858. PMC 1415317. PMID 16436515.

- ^ a b Ikeda H, Old LJ, Schreiber RD (April 2002). "The roles of IFN gamma in protection against tumor development and cancer immunoediting". Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews. 13 (2): 95–109. doi:10.1016/s1359-6101(01)00038-7. PMID 11900986.

- ^ a b Dunn GP, Bruce AT, Sheehan KC, Shankaran V, Uppaluri R, Bui JD, et al. (July 2005). "A critical function for type I interferons in cancer immunoediting". Nature Immunology. 6 (7): 722–729. doi:10.1038/ni1213. PMID 15951814. S2CID 20374688.

- ^ a b Borden EC, Sen GC, Uze G, Silverman RH, Ransohoff RM, Foster GR, et al. (December 2007). "Interferons at age 50: past, current and future impact on biomedicine". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 6 (12): 975–990. doi:10.1038/nrd2422. PMC 7097588. PMID 18049472.

- ^ Whitehead KA, Dahlman JE, Langer RS, Anderson DG (2011). "Silencing or stimulation? siRNA delivery and the immune system". Annual Review of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering. 2: 77–96. doi:10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-061010-114133. PMID 22432611. S2CID 28803811.

- ^ Haller O, Kochs G, Weber F (October–December 2007). "Interferon, Mx, and viral countermeasures". Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews. 18 (5–6): 425–433. doi:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2007.06.001. PMC 7185553. PMID 17683972.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Platanias LC (May 2005). "Mechanisms of type-I- and type-II-interferon-mediated signalling". Nature Reviews. Immunology. 5 (5): 375–386. doi:10.1038/nri1604. PMID 15864272. S2CID 1472195.

- ^ Samarajiwa SA, Forster S, Auchettl K, Hertzog PJ (January 2009). "INTERFEROME: the database of interferon regulated genes". Nucleic Acids Research. 37 (Database issue): D852 – D857. doi:10.1093/nar/gkn732. PMC 2686605. PMID 18996892.

- ^ Xu GP, Zhang ZL, Xiao S, Zhuang LK, Xia D, Zou QP, et al. (March 2013). "Rig-G negatively regulates SCF-E3 ligase activities by disrupting the assembly of COP9 signalosome complex". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 432 (3): 425–430. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.01.132. PMID 23415865.

- ^ Li D, Sun J, Liu W, Wang X, Bals R, Wu J, et al. (2016-10-04). "Rig-G is a growth inhibitory factor of lung cancer cells that suppresses STAT3 and NF-κB". Oncotarget. 7 (40): 66032–66050. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.11797. ISSN 1949-2553. PMC 5323212. PMID 27602766.

- ^ Navratil V, de Chassey B, Meyniel L, Pradezynski F, André P, Rabourdin-Combe C, et al. (July 2010). "System-level comparison of protein-protein interactions between viruses and the human type I interferon system network". Journal of Proteome Research. 9 (7): 3527–3536. doi:10.1021/pr100326j. PMID 20459142.

- ^ a b c d Lin RJ, Liao CL, Lin E, Lin YL (September 2004). "Blocking of the alpha interferon-induced Jak-Stat signaling pathway by Japanese encephalitis virus infection". Journal of Virology. 78 (17): 9285–9294. doi:10.1128/JVI.78.17.9285-9294.2004. PMC 506928. PMID 15308723.

- ^ a b Sen GC (2001). "Viruses and interferons". Annual Review of Microbiology. 55: 255–281. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.255. PMID 11544356.

- ^ a b Alcamí A, Symons JA, Smith GL (December 2000). "The vaccinia virus soluble alpha/beta interferon (IFN) receptor binds to the cell surface and protects cells from the antiviral effects of IFN". Journal of Virology. 74 (23): 11230–11239. doi:10.1128/JVI.74.23.11230-11239.2000. PMC 113220. PMID 11070021.

- ^ Minks MA, West DK, Benvin S, Baglioni C (October 1979). "Structural requirements of double-stranded RNA for the activation of 2',5'-oligo(A) polymerase and protein kinase of interferon-treated HeLa cells". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 254 (20): 10180–10183. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)86690-5. PMID 489592.

- ^ Miller JE, Samuel CE (September 1992). "Proteolytic cleavage of the reovirus sigma 3 protein results in enhanced double-stranded RNA-binding activity: identification of a repeated basic amino acid motif within the C-terminal binding region". Journal of Virology. 66 (9): 5347–5356. doi:10.1128/JVI.66.9.5347-5356.1992. PMC 289090. PMID 1501278.

- ^ Chang HW, Watson JC, Jacobs BL (June 1992). "The E3L gene of vaccinia virus encodes an inhibitor of the interferon-induced, double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 89 (11): 4825–4829. Bibcode:1992PNAS...89.4825C. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.11.4825. PMC 49180. PMID 1350676.

- ^ Seo SH, Hoffmann E, Webster RG (September 2002). "Lethal H5N1 influenza viruses escape host anti-viral cytokine responses". Nature Medicine. 8 (9): 950–954. doi:10.1038/nm757. PMID 12195436. S2CID 8293109.

- ^ Taylor DR, Shi ST, Romano PR, Barber GN, Lai MM (July 1999). "Inhibition of the interferon-inducible protein kinase PKR by HCV E2 protein". Science. 285 (5424): 107–110. doi:10.1126/science.285.5424.107. PMID 10390359.

- ^ Taylor DR, Tian B, Romano PR, Hinnebusch AG, Lai MM, Mathews MB (February 2001). "Hepatitis C virus envelope protein E2 does not inhibit PKR by simple competition with autophosphorylation sites in the RNA-binding domain". Journal of Virology. 75 (3): 1265–1273. doi:10.1128/JVI.75.3.1265-1273.2001. PMC 114032. PMID 11152499.

- ^ Abid K, Quadri R, Negro F (March 2000). "Hepatitis C virus, the E2 envelope protein, and alpha-interferon resistance". Science. 287 (5458): 1555. doi:10.1126/science.287.5458.1555a. PMID 10733410.

- ^ Pawlotsky JM (December 2003). "The nature of interferon-alpha resistance in hepatitis C virus infection". Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 16 (6): 587–592. doi:10.1097/00001432-200312000-00012. PMID 14624110. S2CID 72191620.

- ^ a b c Sa Ribero M, Jouvenet N, Dreux M, Nisole S (July 2020). "Interplay between SARS-CoV-2 and the type I interferon response". PLOS Pathogens. 16 (7) e1008737. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1008737. PMC 7390284. PMID 32726355.

- ^ Palermo E, Di Carlo D, Sgarbanti M, Hiscott J (August 2021). "Type I Interferons in COVID-19 Pathogenesis". Biology. 10 (9): 829. doi:10.3390/biology10090829. PMC 8468334. PMID 34571706.

- ^ Toor SM, Saleh R, Sasidharan Nair V, Taha RZ, Elkord E (January 2021). "T-cell responses and therapies against SARS-CoV-2 infection". Immunology. 162 (1): 30–43. doi:10.1111/imm.13262. PMC 7730020. PMID 32935333.

- ^ a b Bartleson JM, Radenkovic D, Covarrubias AJ, Furman D, Winer DA, Verdin E (September 2021). "SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19 and the Ageing Immune System". Nature Aging. 1 (9): 769–782. doi:10.1038/s43587-021-00114-7. PMC 8570568. PMID 34746804.

- ^ a b Park A, Iwasaki A (June 2020). "Type I and Type III Interferons - Induction, Signaling, Evasion, and Application to Combat COVID-19". Cell Host & Microbe. 27 (6): 870–878. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2020.05.008. PMC 7255347. PMID 32464097.

- ^ Reis G, Moreira Silva EA, Medeiros Silva DC, Thabane L, Campos VH, Ferreira TS, et al. (February 2023). "Early Treatment with Pegylated Interferon Lambda for Covid-19". The New England Journal of Medicine. 388 (6): 518–528. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2209760. PMC 9933926. PMID 36780676.

- ^ Rice GP, Incorvaia B, Munari L, Ebers G, Polman C, D'Amico R, et al. (2001). "Interferon in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2001 (4) CD002002. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002002. PMC 7017973. PMID 11687131.

- ^ Paolicelli D, Direnzo V, Trojano M (14 September 2009). "Review of interferon beta-1b in the treatment of early and relapsing multiple sclerosis". Biologics. 3: 369–376. PMC 2726074. PMID 19707422.

- ^ a b Goldstein D, Laszlo J (Sep 1988). "The role of interferon in cancer therapy: a current perspective". CA. 38 (5): 258–277. doi:10.3322/canjclin.38.5.258. PMID 2458171. S2CID 9160289.

- ^ Hauschild A, Gogas H, Tarhini A, Middleton MR, Testori A, Dréno B, et al. (March 2008). "Practical guidelines for the management of interferon-alpha-2b side effects in patients receiving adjuvant treatment for melanoma: expert opinion". Cancer. 112 (5): 982–994. doi:10.1002/cncr.23251. PMID 18236459.

- ^ Cooksley WG (March 2004). "The role of interferon therapy in hepatitis B". MedGenMed. 6 (1): 16. PMC 1140699. PMID 15208528.

- ^ Shepherd J, Waugh N, Hewitson P (2000). "Combination therapy (interferon alfa and ribavirin) in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a rapid and systematic review". Health Technology Assessment. 4 (33): 1–67. doi:10.3310/hta4330. PMID 11134916.

- ^ "Genotypes of hepatitis C". Hepatitis C Trust. 2023. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ Cunningham M, Foster GR (March 2012). "Efficacy and safety of telaprevir in patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C infection". Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology. 5 (2): 139–151. doi:10.1177/1756283X11426895. PMC 3296085. PMID 22423262.

- ^ Poordad F, McCone J, Bacon BR, Bruno S, Manns MP, Sulkowski MS, et al. (March 2011). "Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection". The New England Journal of Medicine. 364 (13): 1195–1206. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1010494. PMC 3766849. PMID 21449783.

- ^ Bacon BR, Gordon SC, Lawitz E, Marcellin P, Vierling JM, Zeuzem S, et al. (March 2011). "Boceprevir for previously treated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection". The New England Journal of Medicine. 364 (13): 1207–1217. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1009482. PMC 3153125. PMID 21449784.

- ^ Lawitz E, Mangia A, Wyles D, Rodriguez-Torres M, Hassanein T, Gordon SC, et al. (May 2013). "Sofosbuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infection". The New England Journal of Medicine. 368 (20): 1878–1887. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1214853. PMID 23607594.

- ^ Ishikawa T (October 2008). "Secondary prevention of recurrence by interferon therapy after ablation therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis C patients". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 14 (40): 6140–6144. doi:10.3748/wjg.14.6140. PMC 2761574. PMID 18985803.

- ^ Thomas DL, Thio CL, Martin MP, Qi Y, Ge D, O'Huigin C, et al. (October 2009). "Genetic variation in IL28B and spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus". Nature. 461 (7265): 798–801. Bibcode:2009Natur.461..798T. doi:10.1038/nature08463. PMC 3172006. PMID 19759533.

- ^ Ge D, Fellay J, Thompson AJ, Simon JS, Shianna KV, Urban TJ, et al. (September 2009). "Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance". Nature. 461 (7262): 399–401. Bibcode:2009Natur.461..399G. doi:10.1038/nature08309. PMID 19684573. S2CID 1707096.

- ^ a b c Wilhelmus KR (January 2015). "Antiviral treatment and other therapeutic interventions for herpes simplex virus epithelial keratitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1) CD002898. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002898.pub5. PMC 4443501. PMID 25879115.

- ^ Bhatti Z, Berenson CS (February 2007). "Adult systemic cat scratch disease associated with therapy for hepatitis C". BMC Infectious Diseases. 7 8. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-7-8. PMC 1810538. PMID 17319959.

- ^ Long SS, Pickering LK, Prober CG (2012). Principles and Practice of Pediatric Infectious Disease. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1502. ISBN 978-1437727029. Archived from the original on 2019-12-29. Retrieved 2017-09-01.

- ^ Jamall IS, Yusuf S, Azhar M, Jamall S (November 2008). "Is pegylated interferon superior to interferon, with ribavarin, in chronic hepatitis C genotypes 2/3?". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 14 (43): 6627–6631. doi:10.3748/wjg.14.6627. PMC 2773302. PMID 19034963.

- ^ "NIH Consensus Statement on Management of Hepatitis C: 2002". NIH Consensus and State-of-the-Science Statements. 19 (3): 1–46. 2002. PMID 14768714.

- ^ Sharieff KA, Duncan D, Younossi Z (February 2002). "Advances in treatment of chronic hepatitis C: 'pegylated' interferons". Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 69 (2): 155–159. doi:10.3949/ccjm.69.2.155 (inactive 1 July 2025). PMID 11990646.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ Stringfellow DA, Glasgow LA (August 1972). "Tilorone hydrochloride: an oral interferon-inducing agent". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2 (2): 73–78. doi:10.1128/aac.2.2.73. PMC 444270. PMID 4670490.

- ^ Ekins S, Lingerfelt MA, Comer JE, Freiberg AN, Mirsalis JC, O'Loughlin K, et al. (February 2018). "Efficacy of Tilorone Dihydrochloride against Ebola Virus Infection". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 62 (2). doi:10.1128/AAC.01711-17. PMC 5786809. PMID 29133569.

- ^ Kolata G (2015-01-22). "Jean Lindenmann, Who Made Interferon His Life's Work, Is Dead at 90". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2019-12-27. Retrieved 2015-02-12.

- ^ a b Isaacs A, Lindenmann J (September 1957). "Virus interference. I. The interferon". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 147 (927): 258–267. Bibcode:1957RSPSB.147..258I. doi:10.1098/rspb.1957.0048. PMID 13465720. S2CID 202574492.

- ^ a b Pestka S (July 2007). "The interferons: 50 years after their discovery, there is much more to learn". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 282 (28): 20047–20051. doi:10.1074/jbc.R700004200. PMID 17502369.

- ^ Stewart II WE (2013-04-17). The Interferon System. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 1. ISBN 978-3-7091-3432-0.

- ^ Nagano Y, Kojima Y (October 1954). "[Immunizing property of vaccinia virus inactivated by ultraviolets rays]" [Immunizing property of vaccinia virus inactivated by ultraviolets rays]. Comptes Rendus des Séances de la Société de Biologie et de Ses Filiales (in French). 148 (19–20): 1700–1702. PMID 14364998.

- ^ Ho M, Enders JF (March 1959). "An Inhibitor of Viral Activity Appearing in Infected Cell Cultures". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 45 (3): 385–389. Bibcode:1959PNAS...45..385H. doi:10.1073/pnas.45.3.385. PMC 222571. PMID 16590396.

- ^ Tan YH, Tischfield J, Ruddle FH (February 1973). "The linkage of genes for the human interferon-induced antiviral protein and indophenol oxidase-B traits to chromosome G-21". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 137 (2): 317–330. doi:10.1084/jem.137.2.317. PMC 2139494. PMID 4346649.

- ^ Tan YH (March 1976). "Chromosome 21 and the cell growth inhibitory effect of human interferon preparations". Nature. 260 (5547): 141–143. Bibcode:1976Natur.260..141T. doi:10.1038/260141a0. PMID 176593. S2CID 4287343.

- ^ Meager A, Graves H, Burke DC, Swallow DM (August 1979). "Involvement of a gene on chromosome 9 in human fibroblast interferon production". Nature. 280 (5722): 493–495. Bibcode:1979Natur.280..493M. doi:10.1038/280493a0. PMID 460428. S2CID 4315307.

- ^ Berthold W, Tan C, Tan YH (June 1978). "Chemical modifications of tyrosyl residue(s) and action of human-fibroblast interferon". European Journal of Biochemistry. 87 (2): 367–370. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1978.tb12385.x. PMID 678325.

- ^ Berthold W, Tan C, Tan YH (July 1978). "Purification and in vitro labeling of interferon from a human fibroblastoid cell line". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 253 (14): 5206–5212. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)34678-1. PMID 670186.

- ^ a b Tan YH, Barakat F, Berthold W, Smith-Johannsen H, Tan C (August 1979). "The isolation and amino acid/sugar composition of human fibroblastoid interferon". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 254 (16): 8067–8073. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)36051-4. PMID 468807.

- ^ Zoon KC, Smith ME, Bridgen PJ, Anfinsen CB, Hunkapiller MW, Hood LE (February 1980). "Amino terminal sequence of the major component of human lymphoblastoid interferon". Science. 207 (4430): 527–528. Bibcode:1980Sci...207..527Z. doi:10.1126/science.7352260. PMID 7352260.

- ^ Okamura H, Berthold W, Hood L, Hunkapiller M, Inoue M, Smith-Johannsen H, et al. (August 1980). "Human fibroblastoid interferon: immunosorbent column chromatography and N-terminal amino acid sequence". Biochemistry. 19 (16): 3831–3835. doi:10.1021/bi00557a028. PMID 6157401.

- ^ Knight E, Hunkapiller MW, Korant BD, Hardy RW, Hood LE (February 1980). "Human fibroblast interferon: amino acid analysis and amino terminal amino acid sequence". Science. 207 (4430): 525–526. Bibcode:1980Sci...207..525K. doi:10.1126/science.7352259. PMID 7352259.

- ^ Weissenbach J, Chernajovsky Y, Zeevi M, Shulman L, Soreq H, Nir U, et al. (December 1980). "Two interferon mRNAs in human fibroblasts: in vitro translation and Escherichia coli cloning studies". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 77 (12): 7152–7156. Bibcode:1980PNAS...77.7152W. doi:10.1073/pnas.77.12.7152. PMC 350459. PMID 6164058.

- ^ Taniguchi T, Fujii-Kuriyama Y, Muramatsu M (July 1980). "Molecular cloning of human interferon cDNA". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 77 (7): 4003–4006. Bibcode:1980PNAS...77.4003T. doi:10.1073/pnas.77.7.4003. PMC 349756. PMID 6159625.

- ^ Nagata S, Mantei N, Weissmann C (October 1980). "The structure of one of the eight or more distinct chromosomal genes for human interferon-alpha". Nature. 287 (5781): 401–408. Bibcode:1980Natur.287..401N. doi:10.1038/287401a0. PMID 6159536. S2CID 29500779.

- ^ Gray PW, Goeddel DV (August 1982). "Structure of the human immune interferon gene". Nature. 298 (5877): 859–863. Bibcode:1982Natur.298..859G. doi:10.1038/298859a0. PMID 6180322. S2CID 4275528.

- ^ Nagata S, Taira H, Hall A, Johnsrud L, Streuli M, Ecsödi J, et al. (March 1980). "Synthesis in E. coli of a polypeptide with human leukocyte interferon activity". Nature. 284 (5754): 316–320. Bibcode:1980Natur.284..316N. doi:10.1038/284316a0. PMID 6987533. S2CID 4310807.

- ^ US patent 6207146, Tan YH, Hong WJ, "Gene expression in mammalian cells.", issued 27 April 2001, assigned to Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology

- ^ Cantell K (1998). The story of interferon: the ups and downs in the life of a scientis. Singapore; New York: World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-02-3148-4.

- ^ Tan YH, Armstrong JA, Ke YH, Ho M (September 1970). "Regulation of cellular interferon production: enhancement by antimetabolites". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 67 (1): 464–471. Bibcode:1970PNAS...67..464T. doi:10.1073/pnas.67.1.464. PMC 283227. PMID 5272327.

- ^ US patent 3773924, Ho M, Armstrong JA, Ke YH, Tan YH, "Interferon Production", issued 20 November 1973

- ^ Bekisz J, Schmeisser H, Hernandez J, Goldman ND, Zoon KC (December 2004). "Human interferons alpha, beta and omega". Growth Factors. 22 (4): 243–251. doi:10.1080/08977190400000833. PMID 15621727. S2CID 84918367.

- ^ Laghari ZA, Chen SN, Li L, Huang B, Gan Z, Zhou Y, et al. (July 2018). "Functional, signalling and transcriptional differences of three distinct type I IFNs in a perciform fish, the mandarin fish Siniperca chuatsi". Developmental and Comparative Immunology. 84 (1): 94–108. doi:10.1016/j.dci.2018.02.008. PMID 29432791. S2CID 3455413.

- ^ Boudinot P, Langevin C, Secombes CJ, Levraud JP (November 2016). "The Peculiar Characteristics of Fish Type I Interferons". Viruses. 8 (11): 298. doi:10.3390/v8110298. PMC 5127012. PMID 27827855.

Further reading

[edit]- Taylor MW (2014). "Interferons". Viruses and Man: A History of Interactions. pp. 101–119. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-07758-1_7. ISBN 978-3-319-07757-4. PMC 7123835.

External links

[edit] Media related to Interferons at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Interferons at Wikimedia Commons