Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Astrology

View on Wikipedia

| Astrology |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Traditions |

| Branches |

| Astrological signs |

| Symbols |

| Part of a series on the |

| Paranormal |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Esotericism |

|---|

|

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century,[1][2] that propose that information about human affairs and terrestrial events may be discerned by studying the apparent positions of celestial objects.[3][4][5][6][7] Different cultures have employed forms of astrology since at least the 2nd millennium BCE, these practices having originated in calendrical systems used to predict seasonal shifts and to interpret celestial cycles as signs of divine communications.[8]

Most, if not all, cultures have attached importance to what they observed in the sky, and some—such as the Hindus, Chinese, and the Maya—developed elaborate systems for predicting terrestrial events from celestial observations. Western astrology, one of the oldest astrological systems still in use, can trace its roots to 19th–17th century BCE Mesopotamia, from where it spread to Ancient Greece, Rome, the Islamic world, and eventually Central and Western Europe. Contemporary Western astrology is often associated with systems of horoscopes that purport to explain aspects of a person's personality and predict significant events in their lives based on the positions of celestial objects; the majority of professional astrologers rely on such systems.[9]

Throughout its history, astrology has had its detractors, competitors and skeptics who opposed it for moral, religious, political, and empirical reasons.[10][11][12] Nonetheless, prior to the Enlightenment, astrology was generally considered a scholarly tradition and was common in learned circles, often in close relation with astronomy, meteorology, medicine, and alchemy.[13] It was present in political circles and is mentioned in various works of literature, from Dante Alighieri and Geoffrey Chaucer to William Shakespeare, Lope de Vega, and Pedro Calderón de la Barca. During the Enlightenment, however, astrology lost its status as an area of legitimate scholarly pursuit.[14][15]

Following the end of the 19th century and the wide-scale adoption of the scientific method, researchers have successfully challenged astrology on both theoretical[16][17] and experimental grounds,[18][19] and have shown it to have no scientific validity or explanatory power.[20] Astrology thus lost its academic and theoretical standing in the western world, and common belief in it largely declined, until a continuing resurgence starting in the 1960s.[21]

Etymology

[edit]

The word astrology comes from the early Latin word astrologia,[22] which derives from the Greek ἀστρολογία—from ἄστρον astron ("star") and -λογία -logia, ("study of"—"account of the stars"). The word entered the English language via Latin and medieval French, and its use overlapped considerably with that of astronomy (derived from the Latin astronomia). By the 17th century, astronomy became established as the scientific term, with astrology referring to divinations and schemes for predicting human affairs.[23]

History

[edit]

Many cultures have attached importance to astronomical events, and the Indians, Chinese, and Maya developed elaborate systems for predicting terrestrial events from celestial observations. A form of astrology was practised in the Old Babylonian period of Mesopotamia, c. 1800 BCE.[24][8] Vedāṅga Jyotiṣa is one of earliest known Hindu texts on astronomy and astrology (Jyotisha). The text is dated between 1400 BCE to final centuries BCE by various scholars according to astronomical and linguistic evidences. Chinese astrology was elaborated in the Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BCE). Hellenistic astrology after 332 BCE mixed Babylonian astrology with Egyptian Decanic astrology in Alexandria, creating horoscopic astrology. Alexander the Great's conquest of Asia allowed astrology to spread to Ancient Greece and Rome. In Rome, astrology was associated with "Chaldean wisdom". After the conquest of Alexandria in the 7th century, astrology was taken up by Islamic scholars, and Hellenistic texts were translated into Arabic and Persian. In the 12th century, Arabic texts were imported to Europe and translated into Latin. Major astronomers including Tycho Brahe, Johannes Kepler and Galileo practised as court astrologers. Astrological references appear in literature in the works of poets such as Dante Alighieri and Geoffrey Chaucer, and of playwrights such as Christopher Marlowe and William Shakespeare.

Throughout most of its history, astrology was considered a scholarly tradition. It was accepted in political and academic contexts, and was connected with other studies, such as astronomy, alchemy, meteorology, and medicine.[13] At the end of the 17th century, new scientific concepts in astronomy and physics (such as heliocentrism and Newtonian mechanics) called astrology into question. Astrology thus lost its academic and theoretical standing, and common belief in astrology has largely declined.[21]

Ancient world

[edit]Ancient applications

[edit]Astrology, in its broadest sense, is the search for meaning in the sky.[25] Early evidence for humans making conscious attempts to measure, record, and predict seasonal changes by reference to astronomical cycles, appears as markings on bones and cave walls, which show that lunar cycles were being noted as early as 25,000 years ago.[26] This was a first step towards recording the Moon's influence upon tides and rivers, and towards organising a communal calendar.[26] Farmers addressed agricultural needs with increasing knowledge of the constellations that appear in the different seasons—and used the rising of particular star-groups to herald annual floods or seasonal activities.[27] By the 3rd millennium BCE, civilisations had sophisticated awareness of celestial cycles, and may have oriented temples in alignment with heliacal risings of the stars.[28]

Scattered evidence suggests that the oldest known astrological references are copies of texts made in the ancient world. The Venus tablet of Ammisaduqa is thought to have been compiled in Babylon around 1700 BCE.[29] A scroll documenting an early use of electional astrology is doubtfully ascribed to the reign of the Sumerian ruler Gudea of Lagash (c. 2144 – 2124 BCE). This describes how the gods revealed to him in a dream the constellations that would be most favourable for the planned construction of a temple.[30] However, there is controversy about whether these were genuinely recorded at the time or merely ascribed to ancient rulers by posterity. The oldest undisputed evidence of the use of astrology as an integrated system of knowledge is therefore attributed to the records of the first dynasty of Babylon (1950–1651 BCE). This astrology had some parallels with Hellenistic Greek (western) astrology, including the zodiac, a norming point near 9 degrees in Aries, the trine aspect, planetary exaltations, and the dodekatemoria (the twelve divisions of 30 degrees each).[31] The Babylonians viewed celestial events as possible signs rather than as causes of physical events.[31]

The system of Chinese astrology was elaborated during the Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BCE) and flourished during the Han dynasty (2nd century BCE to 2nd century CE), during which all the familiar elements of traditional Chinese culture – the Yin-Yang philosophy, theory of the five elements, Heaven and Earth, Confucian morality – were brought together to formalise the philosophical principles of Chinese medicine and divination, astrology, and alchemy.[32]

The ancient Arabs that inhabited the Arabian Peninsula before the advent of Islam used to profess a widespread belief in fatalism (ḳadar) alongside a fearful consideration for the sky and the stars, which they held to be ultimately responsible for every phenomena that occurs on Earth and for the destiny of humankind.[33] Accordingly, they shaped their entire lives in accordance with their interpretations of astral configurations and phenomena.[33]

Ancient objections

[edit]

The Hellenistic schools of philosophical skepticism criticized astrology, alongside all other beliefs.[34] Criticism of astrology by academic skeptics such as Carneades,[10] Cicero,[35] and Favorinus;[36] Pyrrhonists such as Sextus Empiricus;[37] and neoplatonists such as Plotinus,[38][39] has been preserved.

Carneades argued that belief in fate denies free will and morality; that people born at different times can all die in the same accident or battle; and that contrary to uniform influences from the stars, tribes and cultures are all different.[40]

Cicero, in De Divinatione, leveled a critique of astrology that some modern philosophers consider to be the first working definition of pseudoscience and the answer to the demarcation problem.[35] The philosopher of science Massimo Pigliucci, building on the work of the historian of science, Damian Fernandez-Beanato, argues that Cicero outlined a "convincing distinction between astrology and astronomy that remains valid in the twenty-first century."[41] Cicero stated the twins objection (that with close birth times, personal outcomes can be very different), later developed by Augustine.[42] He argued that since the other planets are much more distant from the Earth than the Moon, they could have only very tiny influence compared to the Moon's.[43] He also argued that if astrology explains everything about a person's fate, then it wrongly ignores the visible effect of inherited ability and parenting, changes in health worked by medicine, or the effects of the weather on people.[44] The historian Stefano Rapisarda notes that the text is formally "equally balanced between pro and contra, and no final or definite answer is given."[45]

Favorinus argued that it was absurd to imagine that stars and planets would affect human bodies in the same way as they affect the tides, and equally absurd that small motions in the heavens cause large changes in people's fates.[36]

Sextus Empiricus argued that it was absurd to link human attributes with myths about the signs of the zodiac, and wrote an entire book, Against the Astrologers (Πρὸς ἀστρολόγους, Pros astrologous), compiling arguments against astrology. Against the Astrologers was the fifth section of a larger work arguing against philosophical and scientific inquiry in general, Against the Professors (Πρὸς μαθηματικούς, Pros mathematikous).[37]

Plotinus, a neoplatonist, had a lasting interest in astrology, including the question of how the world of humans could be affected by the stars, and (if so) whether astrology could predict events on Earth.[46] He argued that since the fixed stars are much more distant than the planets, it is laughable to imagine the planets' effect on human affairs should depend on their position with respect to the zodiac. He also argues that the interpretation of the Moon's conjunction with a planet as good when the moon is full, but bad when the moon is waning, is clearly wrong, as from the Moon's point of view, half of its surface is always in sunlight; and from the planet's point of view, waning should be better, as then the planet sees some light from the Moon, but when the Moon is full to us, it is dark, and therefore bad, on the side facing the planet in question.[39]

Hellenistic Egypt

[edit]

In 525 BCE, Egypt was conquered by the Persians. The 1st century BCE Egyptian Dendera Zodiac shares two signs – the Balance and the Scorpion – with Mesopotamian astrology.[47]

With the occupation by Alexander the Great in 332 BCE, Egypt became Hellenistic. The city of Alexandria was founded by Alexander after the conquest, becoming the place where Babylonian astrology was mixed with Egyptian Decanic astrology to create Horoscopic astrology. This contained the Babylonian zodiac with its system of planetary exaltations, the triplicities of the signs and the importance of eclipses. It used the Egyptian concept of dividing the zodiac into thirty-six decans of ten degrees each, with an emphasis on the rising decan, and the Greek system of planetary Gods, sign rulership and four elements.[48] 2nd century BCE texts predict positions of planets in zodiac signs at the time of the rising of certain decans, particularly Sothis.[49] The astrologer and astronomer Ptolemy lived in Alexandria. Ptolemy's work the Tetrabiblos formed the basis of Western astrology, and, "...enjoyed almost the authority of a Bible among the astrological writers of a thousand years or more."[50]

Greece and Rome

[edit]The conquest of Asia by Alexander the Great exposed the Greeks to ideas from Syria, Babylon, Persia and central Asia.[51] Around 280 BCE, Berossus, a priest of Bel from Babylon, moved to the Greek island of Kos, teaching astrology and Babylonian culture.[52] By the 1st century BCE, there were two varieties of astrology, one using horoscopes to describe the past, present and future; the other, theurgic, emphasising the soul's ascent to the stars.[53] Greek influence played a crucial role in the transmission of astrological theory to Rome.[54]

The first definite reference to astrology in Rome comes from the orator Cato, who in 160 BCE warned farm overseers against consulting with Chaldeans,[55] who were described as Babylonian 'star-gazers'.[56] Among both Greeks and Romans, Babylonia (also known as Chaldea) became so identified with astrology that 'Chaldean wisdom' became synonymous with divination using planets and stars.[57] The 2nd-century Roman poet and satirist Juvenal complains about the pervasive influence of Chaldeans, saying, "Still more trusted are the Chaldaeans; every word uttered by the astrologer they will believe has come from Hammon's fountain."[58]

One of the first astrologers to bring Hermetic astrology to Rome was Thrasyllus, astrologer to the emperor Tiberius,[54] the first emperor to have had a court astrologer,[59] though his predecessor Augustus had used astrology to help legitimise his Imperial rights.[60]

Medieval world

[edit]Hindu

[edit]The main texts upon which classical Indian astrology is based are early medieval compilations, notably the Bṛhat Parāśara Horāśāstra, and Sārāvalī by Kalyāṇavarma. The Horāshastra is a composite work of 71 chapters, of which the first part (chapters 1–51) dates to the 7th to early 8th centuries and the second part (chapters 52–71) to the later 8th century. The Sārāvalī likewise dates to around 800 CE.[61] English translations of these texts were published by N.N. Krishna Rau and V.B. Choudhari in 1963 and 1961, respectively.

Islamic

[edit]

Astrology was taken up by Islamic scholars[62] following the collapse of Alexandria to the Arabs in the 7th century, and the founding of the Abbasid empire in the 8th. The second Abbasid caliph, Al Mansur (754–775) founded the city of Baghdad to act as a centre of learning, and included in its design a library-translation centre known as Bayt al-Hikma 'House of Wisdom', which continued to receive development from his heirs and was to provide a major impetus for Arabic-Persian translations of Hellenistic astrological texts. The early translators included Mashallah, who helped to elect the time for the foundation of Baghdad,[63] and Sahl ibn Bishr, (a.k.a. Zael), whose texts were directly influential upon later European astrologers such as Guido Bonatti in the 13th century, and William Lilly in the 17th century.[64] Knowledge of Arabic texts started to become imported into Europe during the Latin translations of the 12th century.

Jewish

[edit]Medieval Jewish astrology developed significantly in the Islamic World, where Jewish scholars studied, adapted, and debated astrological knowledge inherited from Greek and Arabic sources. While some, like Maimonides, famously rejected astrology as unscientific and theologically problematic, others, including Saadia Gaon, Sherira Gaon, and Hai Gaon, addressed astrological ideas in their commentaries and responsa.[65] Dunash ibn Tamim, active in Kairouan, incorporated astrology into biblical exegesis and authored a critical treatise on its principles.[65] Astrological texts circulated widely among Jewish communities, as evidenced by hundreds of Hebrew and Judeo-Arabic fragments preserved in the Cairo Geniza, including horoscopes, almanacs, and medical or meteorological prognostications.[65]

The most influential figure was Abraham Ibn Ezra (1089–1164), who was born in Tudela, in Al-Andalus, and later traveled extensively throughout the Mediterranean and Western Europe. His astrological corpus includes treatises on horoscopy (Sefer ha-She’elot), electional astrology (Sefer ha-Mivḥarim), medical astrology (Sefer ha-Me'orot), and introductions to theory (Reshit Ḥokhmah, Mishpeṭei ha-Mazalot). His writings served as a bridge between Arabic and Latin astrological traditions and shaped Jewish and Christian astrology in medieval Europe.[65]

Europe

[edit]

In the seventh century, Isidore of Seville argued in his Etymologiae that astronomy described the movements of the heavens, while astrology had two parts: one was scientific, describing the movements of the Sun, the Moon and the stars, while the other, making predictions, was theologically erroneous.[66][67]

The first astrological book published in Europe was the Liber Planetis et Mundi Climatibus ("Book of the Planets and Regions of the World"), which appeared between 1010 and 1027 AD, and may have been authored by Gerbert of Aurillac.[68] Ptolemy's second century AD Tetrabiblos was translated into Latin by Plato of Tivoli in 1138.[68] The Dominican theologian Thomas Aquinas followed Aristotle in proposing that the stars ruled the imperfect 'sublunary' body, while attempting to reconcile astrology with Christianity by stating that God ruled the soul.[69] The thirteenth century mathematician Campanus of Novara is said to have devised a system of astrological houses that divides the prime vertical into 'houses' of equal 30° arcs,[70] though the system was used earlier in the East.[71] The thirteenth century astronomer Guido Bonatti wrote a textbook, the Liber Astronomicus, a copy of which King Henry VII of England owned at the end of the fifteenth century.[70]

In Paradiso, the final part of the Divine Comedy, the Italian poet Dante Alighieri referred "in countless details"[72] to the astrological planets, though he adapted traditional astrology to suit his Christian viewpoint,[72] for example using astrological thinking in his prophecies of the reform of Christendom.[73]

John Gower in the fourteenth century defined astrology as essentially limited to the making of predictions.[66][74][75] The influence of the stars was in turn divided into natural astrology, with for example effects on tides and the growth of plants, and judicial astrology, with supposedly predictable effects on people.[76][77] The fourteenth-century sceptic Nicole Oresme however included astronomy as a part of astrology in his Livre de divinacions.[78] Oresme argued that current approaches to prediction of events such as plagues, wars, and weather were inappropriate, but that such prediction was a valid field of inquiry. However, he attacked the use of astrology to choose the timing of actions (so-called interrogation and election) as wholly false, and rejected the determination of human action by the stars on grounds of free will.[78][79] The friar Laurens Pignon (c. 1368–1449)[80] similarly rejected all forms of divination and determinism, including by the stars, in his 1411 Contre les Devineurs.[81] This was in opposition to the tradition carried by the Arab astronomer Albumasar (787–886) whose Introductorium in Astronomiam and De Magnis Coniunctionibus argued the view that both individual actions and larger scale history are determined by the stars.[82]

In the late 15th century, Giovanni Pico della Mirandola forcefully attacked astrology in Disputationes contra Astrologos, arguing that the heavens neither caused, nor heralded earthly events.[83] His contemporary, Pietro Pomponazzi, a "rationalistic and critical thinker", was much more sanguine about astrology and critical of Pico's attack.[84]

Renaissance and Early Modern

[edit]

Renaissance scholars commonly practised astrology. Gerolamo Cardano cast the horoscope of king Edward VI of England, while John Dee was the personal astrologer to queen Elizabeth I of England. Catherine de Medici paid Michael Nostradamus in 1566 to verify the prediction of the death of her husband, king Henry II of France, made by her astrologer Lucus Gauricus. Major astronomers who practised as court astrologers included Tycho Brahe in the royal court of Denmark, Johannes Kepler to the Habsburgs, Galileo Galilei to the Medici, and Giordano Bruno who was burnt at the stake for heresy in Rome in 1600.[85] The distinction between astrology and astronomy was not entirely clear. Advances in astronomy were often motivated by the desire to improve the accuracy of astrology.[86] Kepler, for example, was driven by a belief in harmonies between Earthly and celestial affairs, yet he disparaged the activities of most astrologers as "evil-smelling dung".[87]

Ephemerides with complex astrological calculations, and almanacs interpreting celestial events for use in medicine and for choosing times to plant crops, were popular in Elizabethan England.[88] In 1597, the English mathematician and physician Thomas Hood made a set of paper instruments that used revolving overlays to help students work out relationships between fixed stars or constellations, the midheaven, and the twelve astrological houses.[89] Hood's instruments also illustrated, for pedagogical purposes, the supposed relationships between the signs of the zodiac, the planets, and the parts of the human body adherents believed were governed by the planets and signs.[89][90] While Hood's presentation was innovative, his astrological information was largely standard and was taken from Gerard Mercator's astrological disc made in 1551, or a source used by Mercator.[91][92] Despite its popularity, Renaissance astrology had what historian Gabor Almasi calls "elite debate", exemplified by the polemical letters of Swiss physician Thomas Erastus who fought against astrology, calling it "vanity" and "superstition." Then around the time of the new star of 1572 and the comet of 1577 there began what Almasi calls an "extended epistemological reform" which began the process of excluding religion, astrology and anthropocentrism from scientific debate.[93] By 1679, the yearly publication La Connoissance des temps eschewed astrology as a legitimate topic.[94]

Enlightenment period and onwards

[edit]

During the Enlightenment, intellectual sympathy for astrology fell away, leaving only a popular following supported by cheap almanacs.[14][15] One English almanac compiler, Richard Saunders, followed the spirit of the age by printing a derisive Discourse on the Invalidity of Astrology, while in France Pierre Bayle's Dictionnaire of 1697 stated that the subject was puerile.[14] The Anglo-Irish satirist Jonathan Swift ridiculed the Whig political astrologer John Partridge.[14]

In the second half of the 17th century, the Society of Astrologers (1647–1684), a trade, educational, and social organization, sought to unite London's often fractious astrologers in the task of revitalizing astrology. Following the template of the popular "Feasts of Mathematicians" they endeavored to defend their art in the face of growing religious criticism. The Society hosted banquets, exchanged "instruments and manuscripts", proposed research projects, and funded the publication of sermons that depicted astrology as a legitimate biblical pursuit for Christians. They commissioned sermons that argued Astrology was divine, Hebraic, and scripturally supported by Bible passages about the Magi and the sons of Seth. According to historian Michelle Pfeffer, "The society's public relations campaign ultimately failed." Modern historians have mostly neglected the Society of Astrologers in favor of the still extant Royal Society (1660), even though both organizations initially had some of the same members.[95]

Astrology saw a popular revival starting in the 19th century, as part of a general revival of spiritualism and—later, New Age philosophy,[96] and through the influence of mass media such as newspaper horoscopes.[97] Early in the 20th century the psychiatrist Carl Jung developed some concepts concerning astrology,[98] which led to the development of psychological astrology.[99][100][101]

Principles and practice

[edit]Advocates have defined astrology as a symbolic language, an art form, a science, and a method of divination.[102][103] Though most cultural astrology systems share common roots in ancient philosophies that influenced each other, many use methods that differ from those in the West. These include Hindu astrology (also known as "Indian astrology" and in modern times referred to as "Vedic astrology") and Chinese astrology, both of which have influenced the world's cultural history.

Western

[edit]Western astrology is a form of divination based on the construction of a horoscope for an exact moment, such as a person's birth.[104] It uses the tropical zodiac, which is aligned to the equinoctial points.[105]

Western astrology is founded on the movements and relative positions of celestial bodies such as the Sun, Moon and planets, which are analysed by their movement through signs of the zodiac (twelve spatial divisions of the ecliptic) and by their aspects (based on geometric angles) relative to one another. They are also considered by their placement in houses (twelve spatial divisions of the sky).[106] Astrology's modern representation in western popular media is usually reduced to sun sign astrology, which considers only the zodiac sign of the Sun at an individual's date of birth, and represents only 1/12 of the total chart.[107]

The horoscope visually expresses the set of relationships for the time and place of the chosen event. These relationships are between the seven 'planets', signifying tendencies such as war and love; the twelve signs of the zodiac; and the twelve houses. Each planet is in a particular sign and a particular house at the chosen time, when observed from the chosen place, creating two kinds of relationship.[108] A third kind is the aspect of each planet to every other planet, where for example two planets 120° apart (in 'trine') are in a harmonious relationship, but two planets 90° apart ('square') are in a conflicted relationship.[109][110] Together these relationships and their interpretations are said to form "...the language of the heavens speaking to learned men."[108]

Along with tarot divination, astrology is one of the core studies of Western esotericism, and as such has influenced systems of magical belief not only among Western esotericists and Hermeticists, but also belief systems such as Wicca, which have borrowed from or been influenced by the Western esoteric tradition. Tanya Luhrmann has said that "all magicians know something about astrology," and refers to a table of correspondences in Starhawk's The Spiral Dance, organised by planet, as an example of the astrological lore studied by magicians.[111]

Hindu

[edit]

The earliest Vedic text on astronomy is the Vedanga Jyotisha; Vedic thought later came to include astrology as well.[112]

Hindu natal astrology originated with Hellenistic astrology by the 3rd century BCE,[113][114] though incorporating the Hindu lunar mansions.[115] The names of the signs (e.g. Greek 'Krios' for Aries, Hindi 'Kriya'), the planets (e.g. Greek 'Helios' for Sun, astrological Hindi 'Heli'), and astrological terms (e.g. Greek 'apoklima' and 'sunaphe' for declination and planetary conjunction, Hindi 'apoklima' and 'sunapha' respectively) in Varaha Mihira's texts are considered conclusive evidence of a Greek origin for Hindu astrology.[116] The Indian techniques may also have been augmented with some of the Babylonian techniques.[117]

Chinese and East Asian

[edit]Chinese astrology has a close relation with Chinese philosophy (theory of the three harmonies: heaven, earth and man) and uses concepts such as yin and yang, the Five phases, the 10 Celestial stems, the 12 Earthly Branches, and shichen (時辰 a form of timekeeping used for religious purposes). The early use of Chinese astrology was mainly confined to political astrology, the observation of unusual phenomena, identification of portents and the selection of auspicious days for events and decisions.[118]

The constellations of the Zodiac of western Asia and Europe were not used; instead the sky is divided into Three Enclosures (三垣 sān yuán), and Twenty-Eight Mansions (二十八宿 èrshíbā xiù) in twelve Ci (十二次).[119] The Chinese zodiac of twelve animal signs is said to represent twelve different types of personality. It is based on cycles of years, lunar months, and two-hour periods of the day (the shichen). The zodiac traditionally begins with the sign of the Rat, and the cycle proceeds through 11 other animal signs: the Ox, Tiger, Rabbit, Dragon, Snake, Horse, Goat, Monkey, Rooster, Dog, and Pig.[120] Complex systems of predicting fate and destiny based on one's birthday, birth season, and birth hours, such as ziping and Zi Wei Dou Shu (simplified Chinese: 紫微斗数; traditional Chinese: 紫微斗數; pinyin: zǐwēidǒushù) are still used regularly in modern-day Chinese astrology. They do not rely on direct observations of the stars.[121]

The Korean zodiac is identical to the Chinese one. The Vietnamese zodiac is almost identical to the Chinese, except for second animal being the Water Buffalo instead of the Ox, and the fourth animal the Cat instead of the Rabbit. The Japanese have since 1873 celebrated the beginning of the new year on 1 January as per the Gregorian calendar. The Thai zodiac begins, not at Chinese New Year, but either on the first day of the fifth month in the Thai lunar calendar, or during the Songkran festival (now celebrated every 13–15 April), depending on the purpose of the use.[122]

Theological viewpoints

[edit]Ancient

[edit]Augustine (354–430) believed that the determinism of astrology conflicted with the Christian doctrines of man's free will and responsibility, and God not being the cause of evil,[123] but he also grounded his opposition philosophically, citing the failure of astrology to explain twins who behave differently although conceived at the same moment and born at approximately the same time.[124]

Medieval

[edit]

Some of the practices of astrology were contested on theological grounds by medieval Muslim astronomers such as Al-Farabi (Alpharabius), Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) and Avicenna. They said that the methods of astrologers conflicted with orthodox religious views of Islamic scholars, by suggesting that the Will of God can be known and predicted.[125] For example, Avicenna's 'Refutation against astrology', Risāla fī ibṭāl aḥkām al-nojūm, argues against the practice of astrology while supporting the principle that planets may act as agents of divine causation. Avicenna considered that the movement of the planets influenced life on earth in a deterministic way, but argued against the possibility of determining the exact influence of the stars.[126] Essentially, Avicenna did not deny the core dogma of astrology, but denied our ability to understand it to the extent that precise and fatalistic predictions could be made from it.[127] Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya (1292–1350), in his Miftah Dar al-SaCadah, also used physical arguments in astronomy to question the practice of judicial astrology.[128] He recognised that the stars are much larger than the planets, and argued:

And if you astrologers answer that it is precisely because of this distance and smallness that their influences are negligible, then why is it that you claim a great influence for the smallest heavenly body, Mercury? Why is it that you have given an influence to al-Ra's [the head] and al-Dhanab [the tail], which are two imaginary points [ascending and descending nodes]?[128]

Modern

[edit]

Martin Luther denounced astrology in his Table Talk. He asked why twins like Esau and Jacob had two different natures yet were born at the same time. Luther also compared astrologers to those who say their dice will always land on a certain number. Although the dice may roll on the number a couple of times, the predictor is silent for all the times the dice fails to land on that number.[129]

What is done by God, ought not to be ascribed to the stars. The upright and true Christian religion opposes and confutes all such fables.[129]

— Martin Luther, Table Talk

The Catechism of the Catholic Church maintains that divination, including predictive astrology, is incompatible with modern Catholic beliefs[130] such as free will:[124]

All forms of divination are to be rejected: recourse to Satan or demons, conjuring up the dead or other practices falsely supposed to "unveil" the future. Consulting horoscopes, astrology, palm reading, interpretation of omens and lots, the phenomena of clairvoyance, and recourse to mediums all conceal a desire for power over time, history, and, in the last analysis, other human beings, as well as a wish to conciliate hidden powers. They contradict the honor, respect, and loving fear that we owe to God alone.[131]

— Catechism of the Catholic Church

Scientific analysis and criticism

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

| Paranormal |

|---|

The scientific community rejects astrology as having no explanatory power for describing the universe, and considers it a pseudoscience.[132][133][134] Scientific testing of astrology has been conducted, and no evidence has been found to support any of the premises or purported effects outlined in astrological traditions.[135][136][137] There is no proposed mechanism of action by which the positions and motions of stars and planets could affect people and events on Earth that does not contradict basic and well understood aspects of biology and physics.[138][17] Those who have faith in astrology have been characterised by scientists including Bart J. Bok as doing so "...in spite of the fact that there is no verified scientific basis for their beliefs, and indeed that there is strong evidence to the contrary".[139]

Confirmation bias is a form of cognitive bias, a psychological factor that contributes to belief in astrology.[140][141][142][143][a] Astrology believers tend to selectively remember predictions that turn out to be true, and do not remember those that turn out false. Another, separate, form of confirmation bias also plays a role, where believers often fail to distinguish between messages that demonstrate special ability and those that do not.[141] Thus there are two distinct forms of confirmation bias that are under study with respect to astrological belief.[144]

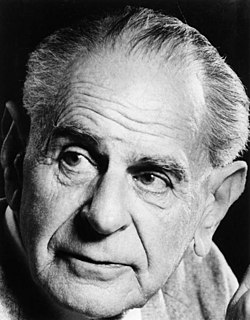

Demarcation

[edit]Under the criterion of falsifiability, first proposed by the philosopher of science Karl Popper, astrology is a pseudoscience.[145] Popper regarded astrology as "pseudo-empirical" in that "it appeals to observation and experiment," but "nevertheless does not come up to scientific standards."[146] In contrast to scientific disciplines, astrology has not responded to falsification through experiment.[147]: 206

In contrast to Popper, the philosopher Thomas Kuhn argued that it was not lack of falsifiability that makes astrology unscientific, but rather that the process and concepts of astrology are non-empirical.[148]: 401 Kuhn thought that, though astrologers had, historically, made predictions that categorically failed, this in itself does not make astrology unscientific, nor do attempts by astrologers to explain away failures by saying that creating a horoscope is very difficult. Rather, in Kuhn's eyes, astrology is not science because it was always more akin to medieval medicine; astrologers followed a sequence of rules and guidelines for a seemingly necessary field with known shortcomings, but they did no research because the fields are not amenable to research,[149]: 8 and so "they had no puzzles to solve and therefore no science to practise."[148]: 401, [149]: 8 While an astronomer could correct for failure, an astrologer could not. An astrologer could only explain away failure but could not revise the astrological hypothesis in a meaningful way. As such, to Kuhn, even if the stars could influence the path of humans through life, astrology is not scientific.[149]: 8

The philosopher Paul Thagard asserts that astrology cannot be regarded as falsified in this sense until it has been replaced with a successor. In the case of predicting behaviour, psychology is the alternative.[6]: 228 To Thagard a further criterion of demarcation of science from pseudoscience is that the state-of-the-art must progress and that the community of researchers should be attempting to compare the current theory to alternatives, and not be "selective in considering confirmations and disconfirmations."[6]: 227–228 Progress is defined here as explaining new phenomena and solving existing problems, yet astrology has failed to progress having only changed little in nearly 2000 years.[6]: 228 [150]: 549 To Thagard, astrologers are acting as though engaged in normal science believing that the foundations of astrology were well established despite the "many unsolved problems", and in the face of better alternative theories (psychology). For these reasons Thagard views astrology as pseudoscience.[6][150]: 228

For the philosopher Edward W. James, astrology is irrational not because of the numerous problems with mechanisms and falsification due to experiments, but because an analysis of the astrological literature shows that it is infused with fallacious logic and poor reasoning.[151]: 34

What if throughout astrological writings we meet little appreciation of coherence, blatant insensitivity to evidence, no sense of a hierarchy of reasons, slight command over the contextual force of critieria, stubborn unwillingness to pursue an argument where it leads, stark naivete concerning the efficacy of explanation and so on? In that case, I think, we are perfectly justified in rejecting astrology as irrational. ... Astrology simply fails to meet the multifarious demands of legitimate reasoning.

— Edward W. James[151]: 34

Effectiveness

[edit]Astrology has not demonstrated its effectiveness in controlled studies and has no scientific validity.[152][19] Where it has made falsifiable predictions under controlled conditions, they have been falsified.[153] One famous experiment included 28 astrologers who were asked to match over a hundred natal charts to psychological profiles generated by the California Psychological Inventory (CPI) questionnaire.[154][155] The double-blind experimental protocol used in this study was agreed upon by a group of physicists and a group of astrologers[19] nominated by the National Council for Geocosmic Research, who advised the experimenters, helped ensure that the test was fair[18]: 420, [155]: 117 and helped draw the central proposition of natal astrology to be tested.[18]: 419 They also chose 26 out of the 28 astrologers for the tests (two more volunteered afterwards).[18]: 420 The study, published in Nature in 1985, found that predictions based on natal astrology were no better than chance, and that the testing "...clearly refutes the astrological hypothesis."[18]

In 1955, the astrologer and psychologist Michel Gauquelin stated that though he had failed to find evidence that supported indicators like zodiacal signs and planetary aspects in astrology, he did find positive correlations between the diurnal positions of some planets and success in professions that astrology traditionally associates with those planets.[156][157] The best-known of Gauquelin's findings is based on the positions of Mars in the natal charts of successful athletes and became known as the Mars effect.[158]: 213 A study conducted by seven French scientists attempted to replicate the claim, but found no statistical evidence.[158]: 213–214 They attributed the effect to selective bias on Gauquelin's part, accusing him of attempting to persuade them to add or delete names from their study.[159]

Geoffrey Dean has suggested that the effect may be caused by self-reporting of birth dates by parents rather than any issue with the study by Gauquelin. The suggestion is that a small subset of the parents may have had changed birth times to be consistent with better astrological charts for a related profession. The number of births under astrologically undesirable conditions was also lower, indicating that parents choose dates and times to suit their beliefs. The sample group was taken from a time when belief in astrology was more common. Gauquelin had failed to find the Mars effect in more recent populations, where a nurse or doctor recorded the birth information.[155]: 116

Dean, a scientist and former astrologer, and psychologist Ivan Kelly conducted a large scale scientific test that involved more than one hundred cognitive, behavioural, physical, and other variables—but found no support for astrology.[160][161] Furthermore, a meta-analysis pooled 40 studies that involved 700 astrologers and over 1,000 birth charts. Ten of the tests—which involved 300 participants—had the astrologers pick the correct chart interpretation out of a number of others that were not the astrologically correct chart interpretation (usually three to five others). When date and other obvious clues were removed, no significant results suggested there was any preferred chart.[161]

Lack of mechanisms and consistency

[edit]Testing the validity of astrology can be difficult, because there is no consensus amongst astrologers as to what astrology is or what it can predict.[162] Most professional astrologers are paid to predict the future or describe a person's personality and life, but most horoscopes only make vague untestable statements that can apply to almost anyone.[20][163]

Many astrologers believe that astrology is scientific,[164] while some have proposed conventional causal agents such as electromagnetism and gravity.[164] Scientists reject these mechanisms as implausible[164] since, for example, the magnetic field, when measured from Earth, of a large but distant planet such as Jupiter is far smaller than that produced by ordinary household appliances.[165]

Western astrology has taken the earth's axial precession (also called precession of the equinoxes) into account since Ptolemy's Almagest, so the "first point of Aries", the start of the astrological year, continually moves against the background of the stars.[166] The tropical zodiac has no connection to the stars; tropical astrologers distinguish the constellations from their historically associated sign, thereby avoiding complications involving precession.[167] Charpak and Broch, noting this, referred to astrology based on the tropical zodiac as being "...empty boxes that have nothing to do with anything and are devoid of any consistency or correspondence with the stars."[167] Sole use of the tropical zodiac is inconsistent with references made, by the same astrologers, to the Age of Aquarius, which depends on when the vernal point enters the constellation of Aquarius.[19]

Astrologers usually have only a small knowledge of astronomy, and often do not take into account basic principles—such as the precession of the equinoxes, which changes the position of the sun with time. They commented on the example of Élizabeth Teissier, who wrote that, "The sun ends up in the same place in the sky on the same date each year", as the basis for the idea that two people with the same birthday, but a number of years apart, should be under the same planetary influence. Charpak and Broch noted that, "There is a difference of about twenty-two thousand miles between Earth's location on any specific date in two successive years", and that thus they should not be under the same influence according to astrology. Over a 40-year period there would be a difference greater than 780,000 miles.[167]

Reception in the social sciences

[edit]The general consensus of astronomers and other natural scientists is that astrology is a pseudoscience which carries no predictive capability, with many philosophers of science considering it a "paradigm or prime example of pseudoscience."[168] Some scholars in the social sciences have cautioned against categorizing astrology, especially ancient astrology, as "just" a pseudoscience or projecting the distinction backwards into the past.[169] Thagard, while demarcating it as a pseudoscience, notes that astrology "should be judged as not pseudoscientific in classical or Renaissance times...Only when the historical and social aspects of science are neglected does it become plausible that pseudoscience is an unchanging category."[170] Historians of science such as Tamsyn Barton, Roger Beck, Francesca Rochberg, and Wouter J. Hanegraaff argue that such a wholesale description is anachronistic when applied to historical contexts, stressing that astrology was not pseudoscience before the 18th century and the importance of the discipline to the development of medieval science.[171][172][173][174][175] R. J. Hakinson writes in the context of Hellenistic astrology that "the belief in the possibility of [astrology] was, at least some of the time, the result of careful reflection on the nature and structure of the universe."[176]

Nicholas Campion, both an astrologer and academic historian of astrology, argues that Indigenous astronomy is largely used as a synonym for astrology in academia, and that modern Indian and Western astrology are better understood as modes of cultural astronomy or ethnoastronomy.[177] Roy Willis and Patrick Curry draw a distinction between propositional episteme and metaphoric metis in the ancient world, identifying astrology with the latter and noting that the central concern of astrology "is not knowledge (factual, let alone scientific) but wisdom (ethical, spiritual and pragmatic)".[178] Similarly, historian of science Justin Niermeier-Dohoney writes that astrology was "more than simply a science of prediction using the stars and comprised a vast body of beliefs, knowledge, and practices with the overarching theme of understanding the relationship between humanity and the rest of the cosmos through an interpretation of stellar, solar, lunar, and planetary movement." Scholars such as Assyriologist Matthew Rutz have begun using the term "astral knowledge" rather than astrology "to better describe a category of beliefs and practices much broader than the term 'astrology' can capture."[179][180]

Cultural impact

[edit]Western politics and society

[edit]In the West, political leaders have sometimes consulted astrologers. For example, the British intelligence agency MI5 employed Louis de Wohl as an astrologer after it was reported that Adolf Hitler used astrology to time his actions. The War Office was "...interested to know what Hitler's own astrologers would be telling him from week to week."[181] In fact, de Wohl's predictions were so inaccurate that he was soon labelled a "complete charlatan", and later evidence showed that Hitler considered astrology "complete nonsense".[182] After John Hinckley's attempted assassination of US President Ronald Reagan, first lady Nancy Reagan commissioned astrologer Joan Quigley to act as the secret White House astrologer. However, Quigley's role ended in 1988 when it became public through the memoirs of former chief of staff, Donald Regan.[183][184][185]

There was a boom in interest in astrology in the late 1960s. The sociologist Marcello Truzzi described three levels of involvement of "Astrology-believers" to account for its revived popularity in the face of scientific discrediting. He found that most astrology-believers did not think that it was a scientific explanation with predictive power. Instead, those superficially involved, knowing "next to nothing" about astrology's 'mechanics', read newspaper astrology columns, and could benefit from "tension-management of anxieties" and "a cognitive belief-system that transcends science."[186] Those at the second level usually had their horoscopes cast and sought advice and predictions. They were much younger than those at the first level, and could benefit from knowledge of the language of astrology and the resulting ability to belong to a coherent and exclusive group. Those at the third level were highly involved and usually cast horoscopes for themselves. Astrology provided this small minority of astrology-believers with a "meaningful view of their universe and [gave] them an understanding of their place in it."[b] This third group took astrology seriously, possibly as an overarching religious worldview (a sacred canopy, in Peter L. Berger's phrase), whereas the other two groups took it playfully and irreverently.[186]

In 1953, the sociologist Theodor W. Adorno conducted a study of the astrology column of a Los Angeles newspaper as part of a project examining mass culture in capitalist society.[187]: 326 Adorno believed that popular astrology, as a device, invariably leads to statements that encouraged conformity—and that astrologers who go against conformity, by discouraging performance at work etc., risk losing their jobs.[187]: 327 Adorno concluded that astrology is a large-scale manifestation of systematic irrationalism, where individuals are subtly led—through flattery and vague generalisations—to believe that the author of the column is addressing them directly.[188] Adorno drew a parallel with the phrase opium of the people, by Karl Marx, by commenting, "occultism is the metaphysic of the dopes."[187]: 329

A 2005 Gallup poll and a 2009 survey by the Pew Research Center reported that 25% of US adults believe in astrology,[189][190] while a 2024 Pew survey found a figure of 27%.[191] According to data released in the National Science Foundation's 2014 Science and Engineering Indicators study, "Fewer Americans rejected astrology in 2012 than in recent years."[192] The NSF study noted that in 2012, "slightly more than half of Americans said that astrology was 'not at all scientific,' whereas nearly two-thirds gave this response in 2010. The comparable percentage has not been this low since 1983."[192] Astrology apps became popular in the late 2010s, some receiving millions of dollars in Silicon Valley venture capital.[193]

India and Japan

[edit]

In India, there is a long-established and widespread belief in astrology. It is commonly used for daily life, particularly in matters concerning marriage and career, and makes extensive use of electional, horary and karmic astrology.[194][195] Indian politics have also been influenced by astrology.[196] It is still considered a branch of the Vedanga.[197][198] In 2001, Indian scientists and politicians debated and critiqued a proposal to use state money to fund research into astrology,[199] resulting in permission for Indian universities to offer courses in Vedic astrology.[200]

In February 2011, the Bombay High Court reaffirmed astrology's standing in India when it dismissed a case that challenged its status as a science.[201]

In Japan, strong belief in astrology has led to dramatic changes in the fertility rate and the number of abortions in the years of Fire Horse. Adherents believe that women born in hinoeuma years are unmarriageable and bring bad luck to their father or husband. In 1966, the number of babies born in Japan dropped by over 25% as parents tried to avoid the stigma of having a daughter born in the hinoeuma year.[202][203]

Literature and music

[edit]

The fourteenth-century English poets John Gower and Geoffrey Chaucer both referred to astrology in their works, including Gower's Confessio Amantis and Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales.[204] Chaucer commented explicitly on astrology in his Treatise on the Astrolabe, demonstrating personal knowledge of one area, judicial astrology, with an account of how to find the ascendant or rising sign.[205]

In the fifteenth century, references to astrology, such as with similes, became "a matter of course" in English literature.[204]

In the sixteenth century, John Lyly's 1597 play, The Woman in the Moon, is wholly motivated by astrology,[206] while Christopher Marlowe makes astrological references in his plays Doctor Faustus and Tamburlaine (both c. 1590),[206] and Sir Philip Sidney refers to astrology at least four times in his romance The Countess of Pembroke's Arcadia (c. 1580).[206] Edmund Spenser uses astrology both decoratively and causally in his poetry, revealing "...unmistakably an abiding interest in the art, an interest shared by a large number of his contemporaries."[206] George Chapman's play, Byron's Conspiracy (1608), similarly uses astrology as a causal mechanism in the drama.[207] William Shakespeare's attitude towards astrology is unclear, with contradictory references in plays including King Lear, Antony and Cleopatra, and Richard II.[207] Shakespeare was familiar with astrology and made use of his knowledge of astrology in nearly every play he wrote,[207] assuming a basic familiarity with the subject in his commercial audience.[207] Outside theatre, the physician and mystic Robert Fludd practised astrology, as did the quack doctor Simon Forman.[207] In Elizabethan England, "The usual feeling about astrology ... [was] that it is the most useful of the sciences."[207]

In seventeenth century Spain, Lope de Vega, with a detailed knowledge of astronomy, wrote plays that ridicule astrology. In his pastoral romance La Arcadia (1598), it leads to absurdity; in his novela Guzman el Bravo (1624), he concludes that the stars were made for man, not man for the stars.[208] Calderón de la Barca wrote the 1641 comedy Astrologo Fingido (The Pretended Astrologer); the plot was borrowed by the French playwright Thomas Corneille for his 1651 comedy Feint Astrologue.[209]

The most famous piece of music influenced by astrology is the orchestral suite The Planets. Written by the British composer Gustav Holst (1874–1934), and first performed in 1918, the framework of The Planets is based upon the astrological symbolism of the planets.[210] Each of the seven movements of the suite is based upon a different planet, though the movements are not in the order of the planets from the Sun. The composer Colin Matthews wrote an eighth movement entitled Pluto, the Renewer, first performed in 2000, as the suite was written prior to Pluto's discovery.[211] In 1937, another British composer, Constant Lambert, wrote a ballet on astrological themes, called Horoscope.[212] In 1974, the New Zealand composer Edwin Carr wrote The Twelve Signs: An Astrological Entertainment[213] for orchestra without strings.[214] Camille Paglia acknowledges astrology as an influence on her work of literary criticism Sexual Personae (1990).[215] The American comedian Harvey Sid Fisher is known for his comedic songs about astrology.[216]

Astrology features strongly in Eleanor Catton's The Luminaries, recipient of the 2013 Man Booker Prize.[217]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ see Heuristics in judgement and decision making

- ^ Italics in original.

References

[edit]- ^ Hanegraaff, Wouter J. (2012). Esotericism and the Academy: Rejected Knowledge in Western Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-521-19621-5. Archived from the original on 26 January 2023. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ Thagard 1978, p. 229.

- ^ "astrology". Oxford Dictionary of English. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 19 July 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- ^ "astrology". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Merriam-Webster Inc. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- ^ Bunnin, Nicholas; Yu, Jiyuan (2008). The Blackwell Dictionary of Western Philosophy. John Wiley & Sons. p. 57. doi:10.1002/9780470996379. ISBN 978-0-470-99721-5.

- ^ a b c d e Thagard, Paul R. (1978). "Why Astrology is a Pseudoscience". Proceedings of the Biennial Meeting of the Philosophy of Science Association. 1 (1): 223–234. doi:10.1086/psaprocbienmeetp.1978.1.192639. ISSN 0270-8647. S2CID 147050929. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ Jarry, Jonathan (9 October 2020). "How Astrology Escaped the Pull of Science". Office for Science and Society. McGill University. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ a b Koch-Westenholz, Ulla (1995). Mesopotamian astrology: an introduction to Babylonian and Assyrian celestial divination. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. pp. Foreword, 11. ISBN 978-87-7289-287-0.

- ^ Bennett 2007, p. 83.

- ^ a b Hughes 2004, p. 87.

- ^ Pigliucci 2024.

- ^ Fernandez-Beanato, Damian (2020). "Cicero's demarcation of science: a report of shared criteria". Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A. 83: 97–102. Bibcode:2020SHPSA..83...97F. doi:10.1016/j.shpsa.2020.04.002. PMID 32958286. S2CID 216477897.

- ^ a b Kassell, Lauren (5 May 2010). "Stars, spirits, signs: towards a history of astrology 1100–1800". Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences. 41 (2): 67–69. doi:10.1016/j.shpsc.2010.04.001. PMID 20513617.

- ^ a b c d Porter, Roy (2001). Enlightenment: Britain and the Creation of the Modern World. Penguin. pp. 151–152. ISBN 978-0-14-025028-2.

he did not even trouble readers with formal disproofs!

- ^ a b Rutkin, H. Darell (2006). "Astrology". In K. Park; L. Daston (eds.). Early Modern Science. The Cambridge History of Science. Vol. 3. Cambridge University Press. pp. 541–561. ISBN 0-521-57244-4. Archived from the original on 22 December 2022. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

As is well known, astrology finally disappeared from the domain of legitimate natural knowledge during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, although the precise contours of this story remain obscure.

- ^ Biswas, Mallik & Vishveshwara 1989, p. 249.

- ^ a b Peter D. Asquith, ed. (1978). Proceedings of the Biennial Meeting of the Philosophy of Science Association, vol. 1 (PDF). Dordrecht: Reidel. ISBN 978-0-917586-05-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.; "Chapter 7: Science and Technology: Public Attitudes and Understanding". science and engineering indicators 2006. National Science Foundation. Archived from the original on 1 February 2013. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

About three-fourths of Americans hold at least one pseudoscientific belief; i.e., they believed in at least 1 of the 10 survey items[29]"... " Those 10 items were extrasensory perception (ESP), that houses can be haunted, ghosts/that spirits of dead people can come back in certain places/situations, telepathy/communication between minds without using traditional senses, clairvoyance/the power of the mind to know the past and predict the future, astrology/that the position of the stars and planets can affect people's lives, that people can communicate mentally with someone who has died, witches, reincarnation/the rebirth of the soul in a new body after death, and channeling/allowing a "spirit-being" to temporarily assume control of a body.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b c d e Carlson, Shawn (1985). "A double-blind test of astrology" (PDF). Nature. 318 (6045): 419–425. Bibcode:1985Natur.318..419C. doi:10.1038/318419a0. S2CID 5135208. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ a b c d Zarka 2011.

- ^ a b Bennett 2007.

- ^ a b Pingree, David E.; Gilbert, Robert Andrew (14 February 2025). "Astrology - Astrology in modern times". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 April 2025.

In countries such as India, where only a small intellectual elite has been trained in Western physics, astrology manages to retain here and there its position among the sciences. Its continued legitimacy is demonstrated by the fact that some Indian universities offer advanced degrees in astrology. In the West, however, Newtonian physics and Enlightenment rationalism largely eradicated the widespread belief in astrology, yet Western astrology is far from dead, as demonstrated by the strong popular following it gained in the 1960s.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "astrology". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 27 June 2017. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

Differentiation between astrology and astronomy began late 1400s and by 17c. this word was limited to "reading influences of the stars and their effects on human destiny."

- ^ "astrology, n.". Oxford English Dictionary (Third ed.). Oxford University Press. December 2021. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

In medieval French, and likewise in Middle English, astronomie is attested earlier, and originally covered the whole semantic field of the study of celestial objects, including divination and predictions based on observations of celestial phenomena. In early use in French and English, astrologie is generally distinguished as the 'art' or practical application of astronomy to mundane affairs, but there is considerable semantic overlap between the two words (as also in other European languages). With the rise of modern science from the Renaissance onwards, the modern semantic distinction between astrology and astronomy gradually developed, and had become largely fixed by the 17th cent. [...] The word is not used by Shakespeare.

- ^ Rochberg, Francesca (1998). Babylonian Horoscopes. American Philosophical Society. p. ix. ISBN 978-0-87169-881-0.

- ^ Campion 2009, pp. 2, 3.

- ^ a b Marshack, Alexander (1991). The roots of civilization: the cognitive beginnings of man's first art, symbol and notation (Rev. and expanded ed.). Moyer Bell. pp. 81ff. ISBN 978-1-55921-041-6.

- ^ Homer; Hesiod (23 March 2017). "#1 — Hesiod's Works and Days". In Page, T.E. (Litt.D.); Rouse, W.H.D. (Litt.D.) (eds.). Works and Days (Collection (Didactic Poetry; Hymns; Epigrams)). Homeric Hymns. Translated by Evelyn-White, Hugh Gerard. Additional Research from Prof. Alois Rzach (1st ed.). London, England: Heinemann (published 9 September 1914). pp. 51–53. ISBN 978-0-674-99063-0. LCCN 16000741. OCLC 3125044. OL 23303325M. Retrieved 2024-08-26 – via Wikisource — The Homeric Hymns and Homerica.

Fifty days after the solstice, when the season of wearisome heat is come to an end, is the right time for men to go sailing. Then you will not wreck your ship, nor will the sea destroy the sailors, unless Poseidon the Earth-Shaker be set upon it, or Zeus, the king of the deathless gods, wish to slay them; for the issues of good and evil alike are with them.

- ^ Kelley, David H.; Milone, Eugene F. (19 March 2022). "Chapter 8.1.5: African Cultures — Egypt and Nubia – Alignments". Exploring Ancient Skies: An Encyclopedic Survey of Archæoastronomy (eBook). Foreword by Anthony F. Aveni. NYC: Springer Publishing (published 6 December 2005). p. 268. doi:10.1007/b137471. ISBN 978-0-387-26356-4. LCCN 2001032842. OCLC 62767201. OL 7448852M. Retrieved 2024-08-26.

…that the temple was aligned on the heliacal rising of Sirius (Sopdet) at the New Year, as Lockyer pointed out.

- ^ Russell Hobson, The Exact Transmission of Texts in the First Millennium B.C.E., Published PhD Thesis. Department of Hebrew, Biblical and Jewish Studies. University of Sydney. 2009 PDF File Archived 2 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ From scroll A of the ruler Gudea of Lagash, I 17 – VI 13. O. Kaiser, Texte aus der Umwelt des Alten Testaments, Bd. 2, 1–3. Gütersloh, 1986–1991. Also quoted in A. Falkenstein, 'Wahrsagung in der sumerischen Überlieferung', La divination en Mésopotamie ancienne et dans les régions voisines. Paris, 1966.

- ^ a b Rochberg-Halton, F. (1988). "Elements of the Babylonian Contribution to Hellenistic Astrology". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 108 (1): 51–62. doi:10.2307/603245. JSTOR 603245. S2CID 163678063.

- ^ Sun, Xiaochun; Kistemaker, Jacob (1997). The Chinese Sky During the Han: Constellating Stars and Society. Leiden: Brill. pp. 3, 4. Bibcode:1997csdh.book.....S. doi:10.1163/9789004488755. ISBN 978-90-04-10737-3.

- ^ a b al-Abbasi, Abeer Abdullah (August 2020). "The Arabsʾ Visions of the Upper Realm". Marburg Journal of Religion. 22 (2). University of Marburg: 1–28. doi:10.17192/mjr.2020.22.8301. ISSN 1612-2941. Archived from the original on 23 May 2022. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius 9:80–88

- ^ a b Fernandez-Beanato 2020.

- ^ a b Long 2005, p. 184.

- ^ a b Long 2005, p. 186.

- ^ Long, A. A. (2005). "6: Astrology: arguments pro and contra". In Barnes, Jonathan; Brunschwig, J. (eds.). Science and Speculation. Studies in Hellenistic Theory and Practice. Cambridge University Press. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-521-02218-7.

- ^ a b Long 2005, p. 174.

- ^ Hughes, Richard (2004). Lament, Death, and Destiny. Peter Lang. p. 87.

- ^ Pigliucci, Massimo (January–February 2024). "Pseudoscience:An Ancient Problem". Skeptical Inquirer. 48 (1): 18, 19.

- ^ Long 2005, p. 173.

- ^ Long 2005, pp. 173–174.

- ^ Long 2005, p. 177.

- ^ Rapisarda, Stefano (9 November 2020). "Traditions and Practices in the Medieval Western Christian World". Prognostication in the Medieval World. De Gruyter. pp. 429–445. doi:10.1515/9783110499773-021. ISBN 978-3-11-049977-3.

- ^ Adamson, Peter (6 November 2008). "Plotinus On Astrology". Oxford Studies In Ancient Philosophy. Oxford University PressOxford. pp. 265–292. doi:10.1093/oso/9780199557790.003.0009. ISBN 978-0-19-955779-0.

- ^ Barton, Tamsyn (1994). Ancient Astrology. Routledge. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-415-11029-7.

- ^ Holden, James Herschel (2006). A History of Horoscopic Astrology (2nd ed.). AFA. pp. 11–13. ISBN 978-0-86690-463-6.

- ^ Barton 1994, p. 20.

- ^ Robbins, Frank E., ed. (1940). Ptolemy Tetrabiblos. Harvard University Press (Loeb Classical Library). p. xii "Introduction". ISBN 978-0-674-99479-9.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Campion, Nicholas (2008). A History of Western Astrology. Vol. I: The Ancient World. London: Continuum. p. 173. ISBN 978-1-4411-2737-2.

- ^ Campion 2008, p. 84.

- ^ Campion 2008, pp. 173–174.

- ^ a b Barton 1994, p. 32.

- ^ Barton 1994, p. 32–33.

- ^ Campion 2008, pp. 227–228.

- ^ Parker, Derek; Parker, Julia (1983). A History of Astrology. Deutsch. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-233-97576-4.

- ^ Juvenal (c. 100). . Translated by Ramsay, George Gilbert. G. P. Putnam's Sons (published 1918) – via Wikisource.

- ^ Barton 1994, p. 43.

- ^ Barton 1994, p. 63.

- ^ David Pingree, Jyotiḥśāstra (J. Gonda (Ed.) A History of Indian Literature, Vol VI Fasc 4), p.81

- ^ Ayduz, Salim; Kalin, Ibrahim; Dagli, Caner (2014). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Science, and Technology in Islam. Oxford University Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-19-981257-8.

- ^ Bīrūnī, Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad (1879). "VIII". The chronology of ancient nations. London, Pub. for the Oriental translations fund of Great Britain & Ireland by W. H. Allen and co. LCCN 01006783.

- ^ Houlding, Deborah (2010). "6: Historical sources and traditional approaches". Essays on the History of Western Astrology. STA. pp. 2–7.

- ^ a b c d Ferrario, Gabriele; Kozodoy, Maud (2021), Lieberman, Phillip I. (ed.), "Science and Medicine", The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 5: Jews in the Medieval Islamic World, The Cambridge History of Judaism, vol. 5, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 840–842, ISBN 978-0-521-51717-1, retrieved 14 July 2025

- ^ a b Wood 1970, p. 5.

- ^ Isidore of Seville (c. 600). Etymologiae. pp. L, 82, col. 170.

- ^ a b Campion 1982, p. 44.

- ^ Campion 1982, p. 45.

- ^ a b Campion 1982, p. 46.

- ^ North, John David (1986). "The eastern origins of the Campanus (Prime Vertical) method. Evidence from al-Bīrūnī". Horoscopes and history. Warburg Institute. pp. 175–176.

- ^ a b Durling, Robert M. (January 1997). "Dante's Christian Astrology. by Richard Kay. Review". Speculum. 72 (1): 185–187. doi:10.2307/2865916. JSTOR 2865916.

Dante's interest in astrology has only slowly been gaining the attention it deserves. In 1940 Rudolf Palgen published his pioneering eighty-page "Dantes Sternglaube: Beiträge zur Erklärung des Paradiso", which concisely surveyed Dante's treatment of the planets and of the sphere of fixed stars; he demonstrated that it is governed by the astrological concept of the "children of the planets" (in each sphere the pilgrim meets souls whose lives reflected the dominant influence of that planet) and that in countless details the imagery of the Paradiso is derived from the astrological tradition. ... Like Palgen, he [Kay] argues (again, in more detail) that Dante adapted traditional astrological views to his own Christian ones; he finds this process intensified in the upper heavens.

- ^ Woody, Kennerly M. (1977). "Dante and the Doctrine of the Great Conjunctions". Dante Studies, with the Annual Report of the Dante Society. 95 (95): 119–134. JSTOR 40166243.

It can hardly be doubted, I think, that Dante was thinking in astrological terms when he made his prophecies. [The attached footnote cites Inferno. I, lOOff.; Purgatorio. xx, 13-15 and xxxiii, 41; Paradiso. xxii, 13-15 and xxvii, 142-148.]

- ^ Gower, John (1390). Confessio Amantis. pp. VII, 670–84. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

Assembled with Astronomie / Is ek that ilke Astrologie / The which in juggementz acompteth / Theffect, what every sterre amonteth, / And hou thei causen many a wonder / To tho climatz that stonde hem under.

- ^ Wedel, Theodore Otto (1920). "Astrology in Gower and Chaucer". The Medieval Attitude Toward Astrology: Particularly in England. Yale University Press. pp. 132–156.

- ^ Wood 1970, p. 6.

- ^ Allen, Don Cameron (1941). Star-crossed Renaissance. Duke University Press. p. 148.

- ^ a b Wood 1970, pp. 8–11.

- ^ Coopland, G. W. (1952). Nicole Oresme and the Astrologers: A Study of his Livre de Divinacions. Harvard University Press; Liverpool University Press.

- ^ Vanderjagt, A.J. (1985). Laurens Pignon, O.P.: Confessor of Philip the Good. Venlo, The Netherlands: Jean Mielot.

- ^ Veenstra, J. R. (1997). Magic and Divination at the Courts of Burgundy and France: Text and Context of Laurens Pignon's 'Contre les Devineurs' (1411). Brill. pp. 5, 32, passim. ISBN 978-90-04-10925-4.

- ^ Veenstra 1997, p. 184.

- ^ Dijksterhuis, Eduard Jan (1986). The mechanization of the world picture. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Martin, Craig (2021). "Pietro Pomponazzi". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University. Archived from the original on 17 March 2019. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ Campion, Nicholas (1982). An Introduction to the History of Astrology. ISCWA. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-9508412-0-5..

- ^ Rabin, Sheila J. (2010). "Pico and the historiography of Renaissance astrology". Explorations in Renaissance Culture. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ^ Caspar, Max (1993). Kepler. Translated by Hellman, C. Doris. New York: Dover Publications. pp. 181–182. ISBN 0-486-67605-6. OCLC 28293391.

- ^ Harkness, Deborah E. (2007). The Jewel House. Elizabethan London and the Scientific Revolution. Yale University Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-300-14316-4.

- ^ a b Harkness, Deborah E. (2007). The Jewel House. Elizabethan London and the Scientific Revolution. Yale University Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-300-14316-4.

- ^ Astronomical diagrams by Thomas Hood, Mathematician (Vellum, in oaken cases). British Library: British Library. c. 1597.

- ^ Johnston, Stephen (July 1998). "The astrological instruments of Thomas Hood". XVII International Scientific Instrument Symposium. Soro. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ^ Vanden Broeke, Steven (2001). "Dee, Mercator, and Louvain Instrument Making: An Undescribed Astrological Disc by Gerard Mercator (1551)". Annals of Science. 58 (3): 219–240. doi:10.1080/00033790016703. S2CID 144443271.

- ^ Almasi, Gabor (11 February 2022). "Astrology in the crossfire: the stormy debate after the comet of 1577". Annals of Science. 79 (2): 137–163. doi:10.1080/00033790.2022.2030409. PMID 35147491. S2CID 246749889. Archived from the original on 7 June 2023. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- ^ Hoskin, Michael, ed. (2003). The Cambridge Concise History of Astronomy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-521-57291-0.

- ^ Pfeffer, Michelle (2021). "The Society of Astrologers (c.1647–1684): sermons, feasts and the resuscitation of astrology in seventeenth-century London". The British Journal for the History of Science. 54 (2): 133–153. doi:10.1017/S0007087421000029. PMID 33719982. S2CID 232232073. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ Campion 2009, pp. 239–249.

- ^ Campion 2009, pp. 259–263.

- ^ Jung, C.G.; Hull (1973). Adler, Gerhard (ed.). C.G. Jung Letters: 1906–1950. in collaboration with Aniela Jaffé; translations from the German by R.F.C. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-09895-1.

Letter from Jung to Freud, 12 June 1911 "I made horoscopic calculations in order to find a clue to the core of psychological truth."

- ^ Campion 2009, pp. 251–256: "At the same time, in Switzerland, the psychologist Carl Gustav Jung (1875–1961) was developing sophisticated theories concerning astrology ..."

- ^ Gieser, Suzanne. The Innermost Kernel, Depth Psychology and Quantum Physics. Wolfgang Pauli's Dialogue with C.G.Jung, (Springer, Berlin, 2005) p. 21 ISBN 3-540-20856-9

- ^ Campion, Nicholas. "Prophecy, Cosmology and the New Age Movement. The Extent and Nature of Contemporary Belief in Astrology."(Bath Spa University College, 2003) via Campion 2009, pp. 248, 256.

- ^ The New Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, v.5, 1974, p. 916

- ^ Dietrich, Thomas: The Origin of Culture and Civilization, Phenix & Phenix Literary Publicists, 2005, p. 305

- ^ Philip P. Wiener, ed. (1974). Dictionary of the history of ideas. New York: Scribner. ISBN 978-0-684-13293-8. Archived from the original on 25 September 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ^ James R. Lewis, 2003. The Astrology Book: the Encyclopedia of Heavenly Influences. Visible Ink Press. Online at Google Books.

- ^ Hone, Margaret (1978). The Modern Text-Book of Astrology. Romford: L. N. Fowler. pp. 21–89. ISBN 978-0-85243-357-7.

- ^ Riske, Kris (2007). Llewellyn's Complete Book of Astrology. Minnesota, US: Llewellyn Publications. pp. 5–6, 27. ISBN 978-0-7387-1071-6.

- ^ a b Kremer, Richard (1990). "Horoscopes and History. by J. D. North; A History of Western Astrology. by S. J. Tester". Speculum. 65 (1): 206–209. doi:10.2307/2864524. JSTOR 2864524.

- ^ Pelletier, Robert; Cataldo, Leonard (1984). Be Your Own Astrologer. Pan. pp. 57–60.

- ^ Fenton, Sasha (1991). Rising Signs. Aquarian Press. pp. 137–9.

- ^ Luhrmann, Tanya (1991). Persuasions of the witch's craft: ritual magic in contemporary England. Harvard University Press. pp. 147–151. ISBN 978-0-674-66324-4.

- ^ Subbarayappa, B. V. (14 September 1989). "Indian astronomy: An historical perspective". In Biswas, S. K.; Mallik, D. C. V.; Vishveshwara, C. V. (eds.). Cosmic Perspectives. Cambridge University Press. pp. 25–40. ISBN 978-0-521-34354-1.

In the Vedic literature Jyotis[h]a, which connotes 'astronomy' and later began to encompass astrology, was one of the most important subjects of study... The earliest Vedic astronomical text has the title, Vedanga Jyotis[h]a...

- ^ Pingree, David (18 December 1978). "Indian Astronomy". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. American Philosophical Society. 122 (6): 361–364. JSTOR 986451.

- ^ Pingree, David (2001). "From Alexandria to Baghdād to Byzantium. The Transmission of Astrology". International Journal of the Classical Tradition. 8 (1): 3–37. Bibcode:2003IJCT...10..487G. doi:10.1007/bf02700227. JSTOR 30224155. S2CID 162030487.

- ^ Werner, Karel (1993). "The Circle of Stars: An Introduction to Indian Astrology by Valerie J. Roebuck. Review". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 56 (3): 645–646. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00008326. JSTOR 620756. S2CID 162270467.

- ^ Burgess, James (October 1893). "Notes on Hindu Astronomy and the History of Our Knowledge of It". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland: 717–761. JSTOR 25197168.

- ^ Pingree, David (June 1963). "Astronomy and Astrology in India and Iran". Isis. The University of Chicago Press on behalf of The History of Science Society. 54 (2): 232. Bibcode:1963Isis...65..229P. doi:10.1086/349703. JSTOR 228540. S2CID 128083594.

- ^ Sun & Kistemaker 1997, pp. 22, 85, 176.

- ^ Stephenson, F. Richard (26 June 1980). "Chinese roots of modern astronomy". New Scientist. 86 (1207): 380–383.

- ^ Theodora Lau, The Handbook of Chinese Horoscopes, pp 2–8, 30–5, 60–4, 88–94, 118–24, 148–53, 178–84, 208–13, 238–44, 270–78, 306–12, 338–44, Souvenir Press, New York, 2005

- ^ Selin, Helaine, ed. (1997). "Astrology in China". Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. Springer. ISBN 978-0-7923-4066-9. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ^ "การเปลี่ยนวันใหม่ การนับวัน ทางโหราศาสตร์ไทย การเปลี่ยนปีนักษัตร โหราศาสตร์ ดูดวง ทำนายทายทัก ('The transition to the new astrological dates Thailand. Changing zodiac astrology horoscope prediction')". Archived from the original on 3 January 2011. (in Thai)

- ^ Veenstra 1997, pp. 184–185.

- ^ a b Hess, Peter M.J.; Allen, Paul L. (2007). Catholicism and science (1st ed.). Westport: Greenwood. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-313-33190-9.

- ^ Saliba, George (1994b). A History of Arabic Astronomy: Planetary Theories During the Golden Age of Islam. New York University Press. pp. 60, 67–69. ISBN 978-0-8147-8023-7.

- ^ Belo, Catarina (23 February 2007). Chance and Determinism in Avicenna and Averroes. Brill. p. 228. doi:10.1163/ej.9789004155879.i-252. ISBN 978-90-474-1915-0.

- ^ Saliba, George (17 August 2011) [First published 15 December 1987]. "AVICENNA viii. Mathematics and Physical Sciences". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. 3. pp. 88–92. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2023.