Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Persian alphabet

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Persian alphabet |

|---|

| ا ب پ ت ث ج چ ح خ د ذ ر ز ژ س ش ص ض ط ظ ع غ ف ق ک گ ل م ن و ه ی |

|

Perso-Arabic script |

| Part of a series on |

| Writing systems in India |

|---|

|

The Persian alphabet (Persian: الفبای فارسی, romanized: Alefbâ-ye Fârsi), also known as the Perso-Arabic script, is the right-to-left alphabet used for the Persian language. This is like the Arabic script with four additional letters: پ چ ژ گ (the sounds 'g', 'zh', 'ch', and 'p', respectively), in addition to the obsolete ڤ that was used for the sound /β/. This letter is no longer used in Persian, as the [β]-sound changed to [b], e.g. archaic زڤان /zaβɑn/ > زبان /zæbɒn/ 'language'.[2][3] Although the sound /β/ (ڤ) is written as "و" nowadays in Farsi (Dari-Parsi/New Persian), it is different to the Arabic /w/ (و) sound, which uses the same letter.

It was the basis of many Arabic-based scripts used in Central and South Asia. It is used for both Iranian and Dari: standard varieties of Persian; and is one of two official writing systems for the Persian language, alongside the Cyrillic-based Tajik alphabet.

The script is mostly but not exclusively right-to-left; mathematical expressions, numeric dates and numbers bearing units are embedded from left to right. The script is cursive, meaning most letters in a word connect to each other; when they are typed, contemporary word processors automatically join adjacent letter forms. Persian is unusual among Arabic scripts because a zero-width non-joiner is sometimes entered in a word, causing a letter to become disconnected from others in the same word.

History

[edit]The Persian alphabet is directly derived and developed from the Arabic alphabet. The Arabic alphabet was introduced to the Persian-speaking world after the Muslim conquest of Persia and the fall of the Sasanian Empire in the 7th century. Following this, the Arabic language became the principal language of government and religious institutions in Persia, which led to the widespread usage of the Arabic script. Classical Persian literature and poetry were affected by this simultaneous usage of Arabic and Persian. A new influx of Arabic vocabulary soon entered the Persian language.[4] In the 8th century, the Tahirid dynasty and Samanid dynasty officially adopted the Arabic script for writing Persian, followed by the Saffarid dynasty in the 9th century, gradually displacing the various Pahlavi scripts used for the Persian language earlier. By the 9th-century, the Perso-Arabic alphabet became the dominant form of writing in Greater Khorasan.[4][5][6]

Under the influence of various Persian Empires, many languages in Central and South Asia that adopted the Arabic script use the Persian Alphabet as the basis of their writing systems. Today, extended versions of the Persian alphabet are used to write a wide variety of Indo-Iranian languages, including Kurdish, Balochi, Pashto, Urdu (from Classical Hindustani), Saraiki, Panjabi, Sindhi and Kashmiri. In the past the use of the Persian alphabet was common amongst Turkic languages, but today is relegated to those spoken within Iran, such as Azerbaijani, Turkmen, Qashqai, Chaharmahali and Khalaj. The Uyghur language in western China is the most notable exception to this.

During the Soviet period many languages in Central Asia, including Persian, were reformed by the government. This ultimately resulted in the Cyrillic-based alphabet used in Tajikistan today. See: Tajik alphabet § History.

Letters

[edit]

Below are the 32 letters of the modern Persian alphabet. Since the script is cursive, the appearance of a letter changes depending on its position: isolated, initial (joined on the left), medial (joined on both sides) and final (joined on the right) of a word.[7] These include 28 letters of the Arabic alphabet, in addition to 4 other letters.

The names of the letters are mostly the ones used in Arabic except for the Persian pronunciation. The only ambiguous name is he, which is used for both ح and ه. For clarification, they are often called hâ-ye jimi (literally "jim-like he" after jim, the name for the letter ج that uses the same base form) and hâ-ye do-češm (literally "two-eyed he", after the contextual middle letterform ـهـ), respectively. There are eight Persian letters that are mainly used in Arabic or foreign loanwords and not in native words: ث, ح, ذ, ص, ض, ط, ظ, ع and غ. These eight letters are also commonly used only in proper names. Unlike Arabic, the Persian language does not have pharyngealization at all. Although the letter غ is mainly used in Arabic loanwords, there are some native Persian words with this letter: آغاز, زغال, etc. The pronunciation of these letters in Persian can differ from their pronunciation in Arabic. For example, the letter ث is pronounced as /s/ in Persian, while it is pronounced as /θ/ in Arabic.

| Letter | Persian | Arabic |

|---|---|---|

| ث | /s/ | /θ/ |

| ح | /h/ | /ħ/ |

| ذ | /z/ | /ð/ |

| ص | /s/ | /sˤ/ |

| ض | /z/ | /dˤ/ |

| ط | /t/ | /tˤ/ |

| ظ | /z/ | /ðˤ/ |

| ع | /ʔ/ | /ʕ/ |

| غ | [ɢ] or [ɣ] | /ɣ/ |

Overview table

[edit]| # | Name (in Persian) |

Name (transliterated) |

Transliteration | IPA | Unicode | Contextual forms | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final | Medial | Initial | Isolated | ||||||

| 0 | همزه | hamze[8] | ʾ | Glottal stop [ʔ] | U+0621 | — | — | — | ء |

| U+0623 | ـأ | أ | |||||||

| U+0626 | ـئ | ـئـ | ئـ | ئ | |||||

| U+0624 | ـؤ | ؤ | |||||||

| 1 | الف | alef | ā | [ɒ] | U+0627 | ـا | ا | ||

| 2 | ب | be | b | [b] | U+0628 | ـب | ـبـ | بـ | ب |

| 3 | پ | pe | p | [p] | U+067E | ـپ | ـپـ | پـ | پ |

| 4 | ت | te | t | [t] | U+062A | ـت | ـتـ | تـ | ت |

| 5 | ث | se | s̱ / s | [s] | U+062B | ـث | ـثـ | ثـ | ث |

| 6 | جیم | jim | ǧ / j | [d͡ʒ] | U+062C | ـج | ـجـ | جـ | ج |

| 7 | چ | če | č | [t͡ʃ] | U+0686 | ـچ | ـچـ | چـ | چ |

| 8 | ح | he (hâ-ye jimi) | ḥ / h | [h] | U+062D | ـح | ـحـ | حـ | ح |

| 9 | خ | xe | x | [x] | U+062E | ـخ | ـخـ | خـ | خ |

| 10 | دال | dâl | d | [d] | U+062F | ـد | د | ||

| 11 | ذال | zâl | ẕ / z | [z] | U+0630 | ـذ | ذ | ||

| 12 | ر | re | r | [r] | U+0631 | ـر | ر | ||

| 13 | ز | ze | z | [z] | U+0632 | ـز | ز | ||

| 14 | ژ | že | ž | [ʒ] | U+0698 | ـژ | ژ | ||

| 15 | سین | sin | s | [s] | U+0633 | ـس | ـسـ | سـ | س |

| 16 | شین | šin | š | [ʃ] | U+0634 | ـش | ـشـ | شـ | ش |

| 17 | صاد | sâd | ṣ / s | [s] | U+0635 | ـص | ـصـ | صـ | ص |

| 18 | ضاد | zâd | ż / z | [z] | U+0636 | ـض | ـضـ | ضـ | ض |

| 19 | طا | tâ | ṭ / t | [t] | U+0637 | ـط | ـطـ | طـ | ط |

| 20 | ظا | zâ | ẓ / z | [z] | U+0638 | ـظ | ـظـ | ظـ | ظ |

| 21 | عین | ʿeyn | ʿ | [ʔ], [æ]/[a] | U+0639 | ـع | ـعـ | عـ | ع |

| 22 | غین | ġeyn | ġ | [ɢ], [ɣ] | U+063A | ـغ | ـغـ | غـ | غ |

| 23 | ف | fe | f | [f] | U+0641 | ـف | ـفـ | فـ | ف |

| 24 | قاف | qâf | q | [q] | U+0642 | ـق | ـقـ | قـ | ق |

| 25 | کاف | kâf | k | [k] | U+06A9 | ـک | ـکـ | کـ | ک |

| 26 | گاف | gâf | g | [ɡ] | U+06AF | ـگ | ـگـ | گـ | گ |

| 27 | لام | lâm | l | [l] | U+0644 | ـل | ـلـ | لـ | ل |

| 28 | میم | mim | m | [m] | U+0645 | ـم | ـمـ | مـ | م |

| 29 | نون | nun | n | [n] | U+0646 | ـن | ـنـ | نـ | ن |

| 30 | واو | vâv (in Farsi) | v / ū / ow / o | [uː], [ow], [v], [o] (only word-finally) | U+0648 | ـو | و | ||

| wâw (in Dari) | w / ū / aw / ō | [uː], [w], [aw], [oː] | |||||||

| 31 | ه | he (hā-ye do-češm) | h | [h], or [e] and [a] (word-finally) | U+0647 | ـه | ـهـ | هـ | ه |

| 32 | ی | ye | y / ī / á / (Also ay / ē in Dari) | [j], [i], [ɒː] ([aj] / [eː] in Dari) | U+06CC | ـی | ـیـ | یـ | ی |

Historically, in Early New Persian, there was a special letter for the sound /β/. This letter is no longer used, as the /β/-sound changed to /b/, e.g. archaic زڤان /zaβān/ > زبان /zæbɒːn/ 'language'.[9]

| Name (in Persian) |

Name (transliterated) |

Transliteration | Sound | Isolated form | Final form | Medial form | Initial form |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ڤ | ve | v / ḇ / ꞵ | /β/ | ڤ | ـڤ | ـڤـ | ڤـ |

Another obsolete variant of the twenty-sixth letter گ /ɡ/ is ݣ which used to appear in old manuscripts.[3]

| Sound | Isolated form | Final form | Medial form | Initial form | Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /ɡ/ | ݣ | ـݣ | ـݣـ | ڭـ | gâf |

Another obsolete variant of the twenty-fifth letter ک /k/ is ك which used to appear in old manuscripts.

| Sound | Isolated form | Final form | Medial form | Initial form | Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /k/ | ك | ـك | ـكـ | كـ | kâf |

The archaic letter ݿ /ɡ/ was also used as a substitute for the twenty-sixth letter of the Persian alphabet, گ, which was used to appear in the older manuscripts of Persian in the late 18th century to the early 19th century.

| Sound | Isolated form | Final form | Medial form | Initial form | Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /ɡ/ | ݿ | ـݿ | ـݿـ | ݿـ | gâf |

Variants

[edit]| ی ه و ن م ل گ ک ق ف غ ع ظ ط ض ص ش س ژ ز ر ذ د خ ح چ ج ث ت پ ب ا ء | ||

|

• | Noto Nastaliq Urdu |

| • | Scheherazade | |

| • | Lateef | |

| • | Noto Naskh Arabic | |

| • | Markazi Text | |

| • | Noto Sans Arabic | |

| • | Baloo Bhaijaan | |

| • | El Messiri SemiBold | |

| • | Lemonada Medium | |

| • | Changa Medium | |

| • | Mada | |

| • | Noto Kufi Arabic | |

| • | Reem Kufi | |

| • | Lalezar | |

| • | Jomhuria | |

| • | Rakkas | |

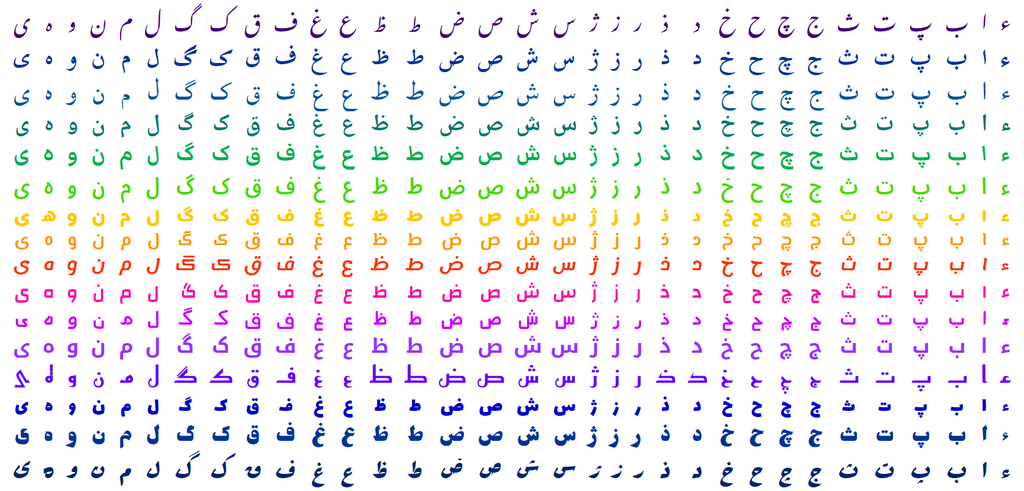

| The alphabet in 16 fonts: Noto Nastaliq Urdu, Scheherazade, Lateef, Noto Naskh Arabic, Markazi Text, Noto Sans Arabic, Baloo Bhaijaan, El Messiri SemiBold, Lemonada Medium, Changa Medium, Mada, Noto Kufi Arabic, Reem Kufi, Lalezar, Jomhuria, and Rakkas. | ||

Letter construction

[edit]| forms (i) | isolated | ء | ا | ى | ں | ٮ | ح | س | ص | ط | ع | ڡ | ٯ | ک | ل | م | د | ر | و | ه | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| start | ء | ا | ٮـ | حـ | سـ | صـ | طـ | عـ | ڡـ | کـ | لـ | مـ | د | ر | و | هـ | ||||||

| mid | ء | ـا | ـٮـ | ـحـ | ـسـ | ـصـ | ـطـ | ـعـ | ـڡـ | ـکـ | ـلـ | ـمـ | ـد | ـر | ـو | ـهـ | ||||||

| end | ء | ـا | ـى | ـں | ـٮ | ـح | ـس | ـص | ـط | ـع | ـڡ | ـٯ | ـک | ـل | ـم | ـد | ـر | ـو | ـه | |||

| i'jam (i) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Unicode | 0621 .. | 0627 .. | 0649 .. | 06BA .. | 066E .. | 062D .. | 0633 .. | 0635 .. | 0637 .. | 0639 .. | 06A1 .. | 066F .. | 066F .. | 0644 .. | 0645 .. | 062F .. | 0631 .. | 0648. .. | 0647 .. | |||

| 1 dot below | ﮳ | ب | ج | |||||||||||||||||||

| Unicode | FBB3. | 0628 .. | 062C .. | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1 dot above | ﮲ | ن | خ | ض | ظ | غ | ف | ذ | ز | |||||||||||||

| Unicode | FBB2. | 0646 .. | 062E .. | 0636 .. | 0638 .. | 063A .. | 0641 .. | 0630 .. | 0632 .. | |||||||||||||

| 2 dots below (ii) | ﮵ | ی | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Unicode | FBB5. | 06CC .. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 dots above | ﮴ | ت | ق | ة | ||||||||||||||||||

| Unicode | FBB4. | 062A .. | 0642 .. | 0629 .. | ||||||||||||||||||

| 3 dots below | ﮹ | پ | چ | |||||||||||||||||||

| Unicode | FBB9. FBB7. | 067E .. | 0686 .. | |||||||||||||||||||

| 3 dots above | ﮶ | ث | ش | ژ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Unicode | FBB6. | 062B .. | 0634 .. | 0698 .. | ||||||||||||||||||

| line above | ‾ | گ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Unicode | 203E. | 06AF .. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| none | ء | ا | ی | ں | ح | س | ص | ط | ع | ک | ل | م | د | ر | و | ه | ||||||

| Unicode | 0621 .. | 0627 .. | 0649 .. | 06BA .. | 062D .. | 0633 .. | 0635 .. | 0637 .. | 0639 .. | 066F .. | 0644 .. | 0645 .. | 062F .. | 0631 .. | 0648. .. | 0647 .. | ||||||

| madda above | ۤ | آ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Unicode | 06E4. 0653. | 0622 .. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Hamza below | ــٕـ | إ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Unicode | 0655. | 0625 .. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Hamza above | ــٔـ | أ | ئ | ؤ | ۀ | |||||||||||||||||

| Unicode | 0674. 0654. | 0623 .. | 0626 .. | 0624 .. | 06C0 .. | |||||||||||||||||

^i. The i'jam diacritic characters are illustrative only; in most typesetting the combined characters in the middle of the table are used.

^ii. Persian yē has 2 dots below in the initial and middle positions only. The standard Arabic version ي يـ ـيـ ـي always has 2 dots below.

Letters that do not link to a following letter

[edit]Seven letters (و, ژ, ز, ر, ذ, د, ا) do not connect to the following letter, unlike the rest of the letters of the alphabet. The seven letters have the same form in isolated and initial position and a second form in medial and final position. For example, when the letter ا alef is at the beginning of a word such as اینجا injâ ("here"), the same form is used as in an isolated alef. In the case of امروز emruz ("today"), the letter ر re takes the final form and the letter و vâv takes the isolated form, but they are in the middle of the word, and ز also has its isolated form, but it occurs at the end of the word.

Diacritics

[edit]Persian script has adopted a subset of Arabic diacritics: zabar /æ/ (fatḥah in Arabic), zēr /e/ (kasrah in Arabic), and pēš /ou̯/ or /o/ (ḍammah in Arabic, pronounced zamme in Western Persian), tanwīne nasb /æn/ and šaddah (gemination). Other Arabic diacritics may be seen in Arabic loanwords in Persian.

Short vowels

[edit]Of the four Arabic diacritics, the Persian language has adopted the following three for short vowels. The last one, sukūn, which indicates the lack of a vowel, has not been adopted.

| Short vowels (fully vocalized text) |

Name (in Persian) |

Name (transliterated) |

Trans.(a) | Value (b)

(Farsi/Dari) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 064E ◌َ |

زبر (فتحه) |

zebar/zibar | a | /æ/ | /a/ |

| 0650 ◌ِ |

زیر (کسره) |

zer/zir | e; i | /e/ | /ɪ/; /ɛ/ |

| 064F ◌ُ |

پیش (ضمّه) |

peš/piš | o; u | /o/ | /ʊ/ |

^a. There is no standard transliteration for Persian. The letters 'i' and 'u' are only ever used as short vowels when transliterating Dari or Tajik Persian. See Persian Phonology

^b. Diacritics differ by dialect, due to Dari having 8 distinct vowels compared to the 6 vowels of Farsi. See Persian Phonology

In Farsi, none of these short vowels may be the initial or final grapheme in an isolated word, although they may appear in the final position as an inflection, when the word is part of a noun group. In a word that starts with a vowel, the first grapheme is a silent alef which carries the short vowel, e.g. اُمید (omid, meaning "hope"). In a word that ends with a vowel, letters ع, ه and و respectively become the proxy letters for zebar, zir and piš, e.g. نو (now, meaning "new") or بسته (bast-e, meaning "package").

Tanvin (nunation)

[edit]Nunation (Persian: تنوین, tanvin) is the addition of one of three vowel diacritics to a noun or adjective to indicate that the word ends in an alveolar nasal sound without the addition of the letter nun.

| Nunation (fully vocalized text) |

Name (in Persian) |

Name (transliterated) |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 064B َاً، ـاً، ءً |

تنوین نَصْبْ | Tanvine nasb | |

| 064D ٍِ |

تنوین جَرّ | Tanvine jarr | Never used in the Persian language. |

| 064C ٌ |

تنوین رَفْعْ | Tanvine rafʿ |

Tašdid

[edit]| Symbol | Name (in Persian) |

Name (transliteration) |

|---|---|---|

| 0651 ّ |

تشدید | tašdid |

Other characters

[edit]The following are not actual letters but different orthographical shapes for letters, a ligature in the case of the lâm alef. As to ﺀ (hamza), it has only one graphical form since it is never tied to a preceding or following letter. However, it is sometimes 'seated' on a vâv, ye or alef, and in that case, the seat behaves like an ordinary vâv, ye or alef respectively. Technically, hamza is not a letter but a diacritic.

| Name | Pronunciation | IPA | Unicode | Final | Medial | Initial | Stand-alone | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| alef madde | â | [ɒ] | U+0622 | ـآ | — | آ | The final form is very rare and is freely replaced with ordinary alef. | |

| he ye | -eye or -eyeh | [eje] | U+06C0 | ـۀ | — | ۀ | Validity of this form depends on region and dialect. Some may use the two-letter ـهی or هی combinations instead. | |

| lām alef | lā | [lɒ] | U+0644 (lām) and U+0627 (alef) | ـلا | لا | |||

| kašida | U+0640 | — | ـ | — | This is the medial character which connects other characters | |||

Although at first glance, they may seem similar, there are many differences in the way the different languages use the alphabets. For example, similar words are written differently in Persian and Arabic, as they are used differently.

Unicode has accepted U+262B ☫ FARSI SYMBOL in the Miscellaneous Symbols range.[10] In Unicode 1.0 this symbol was known as SYMBOL OF IRAN.[11] It is a stylization of الله (Allah) used as the emblem of Iran. It is also a part of the flag of Iran.

The Unicode Standard has a compatibility character defined U+FDFC ﷼ RIAL SIGN that can represent ریال, the Persian name of the currency of Iran.[12]

Novel letters

[edit]The Persian alphabet has four extra letters that are not in the Arabic alphabet: /p/, /t͡ʃ/ (ch in chair), /ʒ/ (s in measure), /ɡ/. An additional fifth letter ڤ was used for /β/ (v in Spanish huevo) but it is no longer used.

| Sound | Shape | Name | Unicode code point |

|---|---|---|---|

| /p/ | پ | pe | U+067E |

| /t͡ʃ/ (ch) | چ | če | U+0686 |

| /ʒ/ (zh) | ژ | že | U+0698 |

| /ɡ/ | گ | gâf | U+06AF |

Deviations from the Arabic script

[edit]Persian uses the Eastern Arabic numerals, but the shapes of the digits 'four' (۴), 'five' (۵), and 'six' (۶) are different from the shapes used in Arabic. All the digits also have different codepoints in Unicode:[13]

| Hindu-Arabic | Persian | Name | Unicode | Arabic | Unicode |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | ۰ | صفر

sefr |

U+06F0 | ٠ | U+0660 |

| 1 | ۱ | يک

yek |

U+06F1 | ١ | U+0661 |

| 2 | ۲ | دو

do |

U+06F2 | ٢ | U+0662 |

| 3 | ۳ | سه

se |

U+06F3 | ٣ | U+0663 |

| 4 | ۴ | چهار

čahâr |

U+06F4 | ٤ | U+0664 |

| 5 | ۵ | پنج

panj |

U+06F5 | ٥ | U+0665 |

| 6 | ۶ | شش

šeš |

U+06F6 | ٦ | U+0666 |

| 7 | ۷ | هفت

haft |

U+06F7 | ٧ | U+0667 |

| 8 | ۸ | هشت

hašt |

U+06F8 | ٨ | U+0668 |

| 9 | ۹ | نه

no |

U+06F9 | ٩ | U+0669 |

| - | ی | ye | U+06CC | ي[c] | U+064A |

| ک | kâf | U+06A9 | ك | U+0643 |

- ^ The alphabet Mazanderani uses is identical to that of Persian's, having no additional modified letters

- ^ Many Perso-Arabic scripts in South Asia share close similarities (use of Nastaliq, use of superscript ط to represent retroflex consonants, etc.) due to mutual contact during development. It is inaccurate to say that one Indo-Persian script directly descends from another, and instead, they are best seen as a cluster of scripts with common origin.

- ^ However, the Arabic variant continues to be used in its traditional style in the Nile Valley, similarly as it is used in Persian and Ottoman Turkish.

Comparison of different numerals

[edit]| Western Arabic | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Eastern Arabic[a] | ٠ | ١ | ٢ | ٣ | ٤ | ٥ | ٦ | ٧ | ٨ | ٩ | ١٠ |

| Persian[b] | ۰ | ۱ | ۲ | ۳ | ۴ | ۵ | ۶ | ۷ | ۸ | ۹ | ۱۰ |

| Urdu[c] | ۰ | ۱ | ۲ | ۳ | ۴ | ۵ | ۶ | ۷ | ۸ | ۹ | ۱۰ |

| Abjad numerals | ا | ب | ج | د | ه | و | ز | ح | ط | ي |

- ^ U+0660 through U+0669

- ^ U+06F0 through U+06F9. The numbers 4, 5, and 6 are different from Eastern Arabic.

- ^ Same Unicode characters as the Persian, but language is set to Urdu. The numerals 4, 6 and 7 are different from Persian. On some devices, this row may appear identical to Persian.

Word boundaries

[edit]Typically, words are separated from each other by a space. Certain morphemes (such as the plural ending '-hâ'), however, are written without a space. On a computer, they are separated from the word using the zero-width non-joiner.

Cyrillic Persian alphabet in Tajikistan

[edit]As part of the russification of Central Asia, the Cyrillic script was introduced in the late 1930s.[14][15][16][17] The alphabet has remained Cyrillic since then. In 1989, with the growth in Tajik nationalism, a law was enacted declaring Tajik the state language. In addition, the law officially equated Tajik with Persian, placing the word Farsi (the endonym for the Persian language) after Tajik. The law also called for a gradual reintroduction of the Perso-Arabic alphabet.[18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][excessive citations]

The Persian alphabet was introduced into education and public life, although the banning of the Islamic Renaissance Party in 1993 slowed adoption. In 1999, the word Farsi was removed from the state-language law, reverting the name to simply Tajik.[1] As of 2004[update] the de facto standard in use is the Tajik Cyrillic alphabet,[2] and as of 1996[update] only a very small part of the population can read the Persian alphabet.[3]

See also

[edit]- Scripts used for Persian

- Romanization of Persian

- Persian braille

- Persian phonology

- Abjad numerals

- Nastaʿlīq, the calligraphy used to write Persian before the 20th century

References

[edit]- ^ "THE ARABI - MALAYALAM SCRIPTURE". 2008-03-18. Archived from the original on 18 March 2008. Retrieved 2023-01-11.

- ^ "PERSIAN LANGUAGE i. Early New Persian". Iranica Online. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ^ a b Orsatti, Paola (2019). "Persian Language in Arabic Script: The Formation of the Orthographic Standard and the Different Graphic Traditions of Iran in the First Centuries of the Islamic Era". Creating Standards (Book).

- ^ a b Lapidus, Ira M. (2012). Islamic Societies to the Nineteenth Century: A Global History. Cambridge University Press. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-521-51441-5.

- ^ Lapidus, Ira M. (2002). A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge University Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-521-77933-3.

- ^ Ager, Simon. "Persian (Fārsī / فارسی)". Omniglot.

- ^ "ویژگىهاى خطّ فارسى". Academy of Persian Language and Literature. Archived from the original on 2017-09-07. Retrieved 2017-08-05.

- ^ "??" (PDF). Persianacademy.ir. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2015-09-05.

- ^ "PERSIAN LANGUAGE i. Early New Persian". Iranica Online. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ^ "Miscellaneous Symbols". p. 4. The Unicode Standard, Version 13.0. Unicode.org

- ^ "3.8 Block-by-block Charts" § Miscellaneous Dingbats p. 325 (155 electronically). The Unicode Standard Version 1.0. Unicode.org

- ^ For the proposal, see Pournader, Roozbeh (2001-09-20). "Proposal to add Arabic Currency Sign Rial to the UCS" (PDF). It proposes the character under the name of ARABIC CURRENCY SIGN RIAL, which was changed by the standard committees to RIAL SIGN.

- ^ "Unicode Characters in the 'Number, Decimal Digit' Category".

- ^ Hämmerle, Christa (2008). Gender Politics in Central Asia: Historical Perspectives and Current Living Conditions of Women. Böhlau Verlag Köln Weimar. ISBN 978-3-412-20140-1.

- ^ Cavendish, Marshall (September 2006). World and Its Peoples. Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 978-0-7614-7571-2.

- ^ Landau, Jacob M.; Landau, Yaʿaqov M.; Kellner-Heinkele, Barbara (2001). Politics of Language in the Ex-Soviet Muslim States: Azerbayjan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, and Tajikistan. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-11226-5.

- ^ Buyers, Lydia M. (2003). Central Asia in Focus: Political and Economic Issues. Nova Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59033-153-8.

- ^ Ehteshami, Anoushiravan (1994). From the Gulf to Central Asia: Players in the New Great Game. University of Exeter Press. ISBN 978-0-85989-451-7.

- ^ Malik, Hafeez (1996). Central Asia: Its Strategic Importance and Future Prospects. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-16452-2.

- ^ Banuazizi, Ali; Weiner, Myron (1994). The New Geopolitics of Central Asia and Its Borderlands. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-20918-4.

- ^ Westerlund, David; Svanberg, Ingvar (1999). Islam Outside the Arab World. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-22691-6.

- ^ Gillespie, Kate; Henry, Clement M. (1995). Oil in the New World Order. University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-1367-1.

- ^ Badan, Phool (2001). Dynamics of Political Development in Central Asia. Lancers' Books.

- ^ Winrow, Gareth M. (1995). Turkey in Post-Soviet Central Asia. Royal Institute of International Affairs. ISBN 978-0-905031-99-6.

- ^ Parsons, Anthony (1993). Central Asia, the Last Decolonization. David Davies Memorial Institute.

- ^ Report on the USSR. RFE/RL, Incorporated. 1990.

- ^ Middle East Monitor. Middle East Institute. 1990.

- ^ Ochsenwald, William; Fisher, Sydney Nettleton (2010-01-06). The Middle East: A History. McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-0-07-338562-4.

- ^ Gall, Timothy L.; Hobby, Jeneen (2009). Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life. Gale. ISBN 978-1-4144-4892-3.

External links

[edit]- Dastoore khat – The Official document in Persian by Academy of Persian Language and Literature

Persian alphabet

View on GrokipediaHistorical Development

Pre-Islamic Scripts

In ancient Persia, the Old Persian cuneiform script emerged around 520 BCE under Darius I of the Achaemenid Empire as the first dedicated writing system for the Old Persian language. This semi-alphabetic system comprised approximately 36 signs—23 syllabic, 8 alphabetic, and 5 ideographic—adapted from Mesopotamian cuneiform traditions but simplified to better suit Iranian phonology, marking a deliberate innovation for royal inscriptions on monuments like the Behistun Inscription.[7] Its wedge-shaped impressions on stone or clay facilitated trilingual records alongside Elamite and Babylonian, though it remained primarily monumental and fell out of use by the 4th century BCE following Alexander's conquests.[8] During the subsequent Seleucid, Parthian (247 BCE–224 CE), and Sassanid (224–651 CE) periods, Aramaic-derived cursive scripts supplanted cuneiform for Middle Persian and related Iranian languages, evolving into the Pahlavi family of scripts. Inscriptional Pahlavi, attested from the 2nd century BCE in Parthian rock reliefs and coins, transitioned to Sassanid royal usage by the 3rd century CE, employing about 20 consonantal letters with Aramaic heterograms—logographic elements pronounced in Persian but written in Aramaic form—to denote abstract or foreign terms.[9] Book Pahlavi, a more fluid variant used for Zoroastrian texts, legal documents, and literature from the 3rd to 9th centuries CE, lacked dedicated vowel markers, relying on matres lectionis and reader familiarity, which contributed to ambiguities in transmission.[8] Parallel to Pahlavi developments, the Avestan script was devised in the Sassanid era, likely between the 3rd and 6th centuries CE, to preserve the sacred Avestan texts of Zoroastrianism, which predated the script by over a millennium. This 53-character alphabet, an extension of Pahlavi with added signs for archaic sounds like aspirates and fricatives, prioritized phonological accuracy over cursive efficiency, enabling precise rendering of liturgical chants absent in everyday Pahlavi usage. These pre-Islamic systems underscored a progression from syllabo-ideographic to abjad-like forms, influenced by administrative Aramaic but tailored to Iranian linguistic needs, until the 7th-century Arab conquests prompted script replacement.[8]Adoption of Arabic Script Post-Conquest

The Arab Muslim conquest of the Sasanian Empire, spanning 633 to 651 CE, marked the beginning of Persia's integration into the Umayyad (661–750 CE) and subsequent Abbasid (750–1257 CE) caliphates, where Arabic served as the primary language of administration, governance, and religious practice.[10][8] This political and cultural shift facilitated the gradual replacement of the Pahlavi script—derived from Aramaic and used for Middle Persian—with the Arabic script, driven by the need for compatibility with Islamic textual traditions, including the Quran and legal documents, as Persian elites converted to Islam and participated in caliphal bureaucracy.[10][8] Pahlavi continued in limited Zoroastrian and private contexts into the 9th century, but its cursive complexity and association with pre-Islamic traditions diminished under the prestige of Arabic as the script of revelation and empire.[10] The adoption was not abrupt but evolved through pragmatic adaptation, as Persians retained their language's Indo-European structure while borrowing the Arabic abjad for its established utility in Semitic phonology and right-to-left cursive flow, which paralleled aspects of Pahlavi.[10] By the late 9th century, under the Tahirid dynasty (821–873 CE) in eastern Iran, administrative incentives accelerated the shift, with governors promoting written Persian for local records amid Abbasid oversight.[11] The earliest surviving Persian annotations in Arabic script appear as marginal notes on Quran juz' booklets dated 292 AH (905 CE), penned by Ahmad Khayqānī of Tūs, indicating initial use for personal or scholarly glosses rather than full literary works.[12] The Samanid dynasty (819–1005 CE), ruling from Bukhara, played a pivotal role in formalizing the transition by patronizing a revival of Persian as a literary medium in Arabic script, fostering Early New Persian (ENP) prose and poetry from the 9th to early 10th centuries.[10] This era saw the first dated ENP prose texts around the mid-10th century, reflecting a causal link between dynastic autonomy from Baghdad—allowing cultural reassertion—and the script's entrenchment for expressing Persian identity within an Islamic framework.[10][13] Subsequent dynasties like the Ghaznavids (977–1186 CE) extended this, solidifying Arabic script as the standard for Persian by the 11th century, despite initial phonological mismatches that later prompted letter additions.[10]Post-Adoption Evolutions and Standardizations

Following the adoption of the Arabic script for Persian in the early Islamic period, scribes modified the system to accommodate phonemes absent in standard Arabic, introducing four additional letters: پ for the sound /p/, چ for /tʃ/, ژ for /ʒ/, and گ for /ɡ/.[14][15] These adaptations emerged gradually in the centuries after the 7th-century Muslim conquest, enabling more accurate representation of Persian consonants during the Abbasid era and under subsequent Persian dynasties like the Tahirids and Samanids in the 8th and 9th centuries.[16][17] In the realm of calligraphic styles, the 14th century marked a pivotal evolution with the development of the nastaʿlīq script, tailored for Persian literary works. Formalized by the calligrapher Mir ʿAlī Tabrīzī in the second half of the 1300s, nastaʿlīq derived from earlier hanging scripts like taʿlīq but emphasized fluidity and aesthetic proportion suited to Persian poetry and prose.[18][19] This style, originating in regions like Shiraz or Tabriz, became dominant for Persian manuscripts by the Timurid period, supplanting angular scripts like naskh for non-Quranic texts due to its visual harmony with the language's rhythm.[20][21] Modern standardizations accelerated with the introduction of printing technology in the 19th and 20th centuries, which posed challenges for rendering cursive nastaʿlīq digitally and typographically. In Iran, 20th-century language planning under the Pahlavi dynasty formalized orthographic rules, including consistent spelling conventions and diacritic usage, to promote literacy and uniformity in print media.[11][22] Afghanistan's Dari variant saw less centralized standardization, retaining regional variations amid political instability, though both nations preserved the Perso-Arabic base despite 19th-century reform proposals for simplification or Latinization, which ultimately failed to gain traction.[23][24] Efforts in digital typesetting, such as those enabling nastaʿlīq fonts, continue to refine compatibility with contemporary computing standards.[22]Script Composition and Mechanics

Letter Forms and Positional Variants

The Persian script, a cursive variant of the Arabic abjad adapted for Persian phonology, features letters that assume distinct shapes based on their position in a word, facilitating fluid right-to-left writing. This positional variation results in up to four glyph forms per letter: isolated (standalone or non-connected), initial (word-initial, joining rightward), medial (intermediary, joining both sides), and final (word-final, joining leftward).[25][26] Most of the 32 letters in the Persian alphabet—derived from 28 Arabic letters plus additions like پ (p), چ (ch), ژ (zh), and گ (g)—exhibit all four forms when contextually appropriate, with shapes designed for seamless cursive connection. Joining occurs between compatible letters, where a preceding letter's final or medial form links to the succeeding letter's initial or medial form, except for non-joining letters that break the chain.[27][25] Six letters do not join to the following letter (leftward in writing direction), limiting them to isolated and final forms: ا (ʾalef), د (dāl), ذ (ḏāl), ر (rāʾ), ز (zāy), ژ (žāy), and و (wāw). These non-linkers, inherited from Arabic but including the Persian-specific ژ, prevent medial or initial appearances in connected sequences, enforcing orthographic spaces or adjustments for readability. For instance, د in medial-like positions uses its final form without rightward linkage.[25][26] The letter ه (hāʾ) exhibits a characteristic looped final form distinct from its simpler isolated, initial, and medial variants, enhancing cursive elegance. In dominant styles like Nastaʿlīq, positional forms incorporate proportional elongations and curves, with initial forms often more upright and finals more extended, as standardized in Persian manuscript traditions since the Timurid era (14th–15th centuries).[27][25] Persian adaptations introduce positional variants for added letters: پ mirrors ب (bāʾ) but with three dots; چ parallels ج (jīm); گ extends ك (kāf) with a loop and dots. These maintain Arabic-derived joining behaviors while accommodating Persian consonants absent in Arabic, such as /p/, /ch/, /g/.[25][28]Diacritics and Vowel Indicators

The Persian script, an adaptation of the Arabic abjad, primarily represents consonants while vowels are often implied by context, with diacritics used optionally to mark short vowels or resolve ambiguities, particularly in pedagogical texts or early manuscripts. Short vowels—/a/, /e/, and /o/—are indicated by three harakat diacritics derived from Arabic: fatḥah (َ) for /a/, kasrah (ِ) for /e/ under the letter, and ḍammah (ُ) for /o/. These marks are positioned above or below the consonant they follow, but their use is minimal in standard writing, as Persian readers rely on familiarity with vocabulary to infer them, leading to potential homographs without voweling.[25][29] Long vowels—/ɒː/ (ā), /iː/, and /uː/—are denoted by matres lectionis rather than diacritics: alef (ا) for /ɒː/, typically at word-initial or medial positions; ye (ی or ى) for /iː/ (or /e/ in diphthongs); and waw (و) for /uː/. At the word's start, alef may carry diacritics to specify short variants, such as اَ for /a/ or اُ for /o/, though this is rare outside explicit instruction. This system reflects Persian's phonetic inventory of six monophthongs, where long vowels are consistently orthographically represented to maintain readability, unlike the frequently elided short ones.[30][29][31] Additional diacritics include the sukūn (ْ), a small circle indicating a consonant without a following vowel, which appears in fully vowelled texts to denote syllable boundaries or quiescence, such as in consonant clusters uncommon in native Persian but present in loanwords. The tašdid or shadda (ّ), a doubled waw-like mark, signifies gemination (consonant doubling) for emphasis or length, as in تَپِّه (tape "hill" with emphatic /p/). These marks, while standardized in printing since the 19th century with lithographic presses, remain supplementary, with full vocalization (tashkīl) confined to religious texts, children's books, or linguistic analyses to aid non-native learners.[25][5]Non-Linking Letters and Orthographic Rules

In the Perso-Arabic script employed for writing Persian, the system is inherently cursive, with most letters joining to both preceding and following letters within words, resulting in positional variants (initial, medial, final, and isolated forms). However, seven letters refuse to connect to the succeeding letter, disrupting the continuous ligature: ا (alef), د (dāl), ذ (zāl), ر (re), ز (zāy), ژ (žāy), and و (vāv).[25][32] These non-joining letters link only from the right (to a preceding letter) but maintain their final or isolated form when followed by another letter, forcing the subsequent letter to adopt its initial form and creating a visual break in the word's flow.[33][25] This property stems from the script's Arabic origins, where such letters—originally designed without rightward extensions—were retained in Persian adaptations, including the addition of ژ for the /ʒ/ sound.[25] In practice, words containing these letters exhibit segmented cursive lines; for example, in "در" (dar, 'door'), the ر assumes its isolated form after د, preventing fusion.[33] Non-joining letters comprise about 20% of Persian's 32-letter inventory and appear frequently in native vocabulary, influencing readability and aesthetic justification in typesetting.[25] Orthographic rules mandate contextual shaping in digital and manuscript rendering, where font engines automatically apply joins except after non-joining letters. To override default joining at morphological or semantic boundaries—such as prefixes (e.g., می in "میرود", mi-ravad, 'goes'), suffixes (e.g., ها in "کتابها", ketāb-hā, 'books'), or compounds—the zero-width non-joiner (ZWNJ, Unicode U+200C) is inserted without visible space.[27][34] This invisible character enforces separation, preserving etymological clarity in a script that historically prioritizes consonantal roots over phonetic transparency.[25][27] Further conventions include obligatory ligatures, such as لام-alef (ل + ا forming لا), and the use of tatweel (ـ, U+0640) for line justification without altering meaning, though sparingly to avoid distorting proportions.[25] Persian orthography also accommodates short vowel omission in everyday texts, relying on reader familiarity with these connection rules to infer pronunciation, which can lead to ambiguities resolved only by diacritics in pedagogical or religious contexts.[3][25] These rules, standardized in modern printing since the 19th-century adoption of movable type in Iran, balance tradition with legibility in a right-to-left, abjad system.[25]Phonological Mapping

Consonant Representation

The Perso-Arabic script employed for Persian primarily functions as an abjad, explicitly denoting consonant phonemes while largely omitting short vowels unless diacritics are applied. Persian distinguishes 23 consonant phonemes, mapped onto 32 letters that include the 28 of the standard Arabic alphabet plus four innovations: پ for /p/, چ for /tʃ/, ژ for /ʒ/, and گ for /ɡ/, accommodating sounds absent in Classical Arabic.[25][33] These additions emerged during the script's adaptation following the Arab conquest of Persia in the 7th century, enabling representation of indigenous Indo-Iranian phonology.[25] Phonological mergers relative to Arabic result in multiple letters per phoneme, preserving etymological origins—particularly from Arabic loanwords comprising up to 40% of modern Persian vocabulary—despite simplified pronunciation. For example, the sibilant /s/ is rendered by س (sīn), ث (sā), or ص (sād); the alveolar /z/ by ز (zāy), ذ (zāl), ض (zād), or ظ (zāʾ); dentals /t/ and /d/ occasionally by emphatic Arabic ط (ṭā) and ض in loans but pronounced identically to ت (tā) and د (dāl). Velar and uvular fricatives /x/ (خ, xā) and /ɣ/ (غ, ġayn) are native, while /q/ (ق, qāf) appears mainly in loans and variably realizes as [ɢ], [ɡ], or depending on dialect and idiolect, with Iranian standard often merging it toward /ɡ/. Glottal /ʔ/ uses ء (hamza) or ع (ʿayn), the latter also serving vowel-adjacent roles.[25][33] The following table summarizes primary consonant mappings, with IPA phonemes and representative letters (Unicode forms provided for precision):| IPA Phoneme | Primary Letters | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| /p/ | پ | Persian addition; absent in Arabic.[33] |

| /b/ | ب | Bilabial stop. |

| /t/ | ت, ط | /t/ merges emphatic ط in pronunciation.[25] |

| /d/ | د | Alveolar stop; non-joining form. |

| /k/ | ک | Variant of Arabic ك. |

| /ɡ/ | گ, ق (variant) | Persian addition گ; ق often [ɡ] in Iran.[25] |

| /tʃ/ | چ | Affricate; Persian addition.[33] |

| /dʒ/ | ج | Affricate. |

| /f/ | ف | Labiodental fricative. |

| /v/ | و | Also denotes /uː, oː/; context-dependent.[25] |

| /s/ | س, ث, ص | Multiple for etymology; ث, ص from Arabic loans.[25] |

| /z/ | ز, ذ, ض, ظ | Four variants; ذ, ض, ظ Arabic-derived.[25] |

| /ʃ/ | ش | Postalveolar fricative. |

| /ʒ/ | ژ | Persian addition; rare in native words.[33] |

| /x/ | خ | Velar fricative. |

| /ɣ/ or /ɢ/ | غ, ق (variant) | Ghayn variably fricative or stop.[25] |

| /h/ | ه, ح | Both /h/; ح Arabic emphatic, merged. |

| /ʔ/ | ء, ع | Glottal stop; ع often elided.[25] |

| /m/ | م | Bilabial nasal. |

| /n/ | ن | Alveolar nasal. |

| /r/ | ر | Trilled; non-joining. |

| /l/ | ل | Alveolar lateral. |

| /j/ | ی | Also /iː/; semi-vowel.[25] |