Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

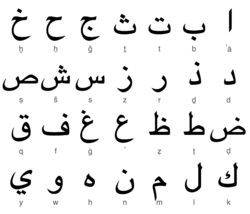

Arabic script

View on Wikipedia

| Arabic script | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

Period | 3rd century CE to the present[1] |

| Direction | Right-to-left |

| Official script | 21 sovereign states Official script at regional level in: |

| Languages | See below |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Child systems | N'Ko Hanifi script Persian alphabet |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Arab (160), Arabic |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Arabic |

| |

The Arabic script is the writing system used for Arabic (Arabic alphabet) and several other languages of Asia and Africa. It is the second-most widely used alphabetic writing system in the world (after the Latin script),[2] the second-most widely used writing system in the world by number of countries using it, and the third-most by number of users (after the Latin and Chinese scripts).[3]

The script was first used to write texts in Arabic, most notably the Quran, the holy book of Islam. With the religion's spread, it came to be used as the primary script for many language families, leading to the addition of new letters and other symbols. Such languages still using it are Arabic, Persian (Farsi and Dari), Urdu, Uyghur, Kurdish, Pashto, Punjabi (Shahmukhi), Sindhi, Azerbaijani (Torki in Iran), Malay (Jawi), Javanese, Sundanese, Madurese and Indonesian (Pegon), Balti, Balochi, Luri, Kashmiri, Cham (Akhar Srak),[4] Rohingya, Somali, Mandinka, and Mooré, among others.[5] Until the 16th century, it was also used for some Spanish texts, and—prior to the script reform in 1928—it was the writing system of Turkish.[6]

The script is written from right to left in a cursive style, in which most of the letters are written in slightly different forms according to whether they stand alone or are joined to a following or preceding letter. The script is unicase and does not have distinct capital or lowercase letters.[7] In most cases, the letters transcribe consonants, or consonants and a few vowels, so most Arabic alphabets are abjads, with the versions used for some languages, such as Sorani dialect of Kurdish, Uyghur, Mandarin, and Serbo-Croatian, being alphabets. It is the basis for the tradition of Arabic calligraphy.

| Part of a series on |

| Calligraphy |

|---|

|

History

[edit]The Arabic alphabet is derived either from the Nabataean alphabet[8][9] or (less widely believed) directly from the Syriac alphabet,[10] which are both derived from the Aramaic alphabet, which, in turn, descended from the Phoenician alphabet. The Phoenician script also gave rise to the Greek alphabet (and, therefore, both the Cyrillic alphabet and the Latin alphabet used in North and South America and most European countries).

Origins

[edit]In the 6th and 5th centuries BCE, northern Arab tribes emigrated and founded a kingdom centred around Petra, Jordan. This people (now named Nabataeans from the name of one of the tribes, Nabatu) spoke Nabataean Arabic, a dialect of the Arabic language. In the 2nd or 1st centuries BCE,[11][12] the first known records of the Nabataean alphabet were written in the Aramaic language (which was the language of communication and trade), but included some Arabic language features: the Nabataeans did not write the language which they spoke. They wrote in a form of the Aramaic alphabet, which continued to evolve; it separated into two forms: one intended for inscriptions (known as "monumental Nabataean") and the other, more cursive and hurriedly written and with joined letters, for writing on papyrus.[13] This cursive form influenced the monumental form more and more and gradually changed into the Arabic alphabet.

Overview

[edit]| خ | ح | ج | ث | ت | ب | ا |

| khā’ | ḥā’ | jīm | tha’ | tā’ | bā’ | alif |

| ص | ش | س | ز | ر | ذ | د |

| ṣād | shīn | sīn | zāy / zayn |

rā’ | dhāl | dāl |

| ق | ف | غ | ع | ظ | ط | ض |

| qāf | fā’ | ghayn | ‘ayn | ẓā’ | ṭā’ | ḍād |

| ي | و | ه | ن | م | ل | ك |

| yā’ | wāw | hā’ | nūn | mīm | lām | kāf |

| أ | آ | إ | ئ | ؠ | ء | ࢬ |

| alif hamza↑ | alif madda | alif hamza↓ | yā’ hamza↑ | kashmiri yā’ | hamza | rohingya yā’ |

| ى | ٱ | ی | ە | ً | ٌ | ٍ |

| alif maksura | alif wasla | farsi yā’ | ae | fathatan | dammatan | kasratan |

| َ | ُ | ِ | ّ | ْ | ٓ | ۤ |

| fatha | damma | kasra | shadda | sukun | maddah | madda |

| ں | ٹ | ٺ | ٻ | پ | ٿ | ڃ |

| nūn ghunna | ttā’ | ttāhā’ | bāā’ | pā’ | tāhā’ | nyā’ |

| ڄ | چ | ڇ | ڈ | ڌ | ڍ | ڎ |

| dyā’ | tchā’ | tchahā’ | ddāl | dāhāl | ddāhāl | duul |

| ڑ | ژ | ڤ | ڦ | ک | ڭ | گ |

| rrā’ | jā’ | vā’ | pāḥā’ | kāḥā’ | ng | gāf |

| ڳ | ڻ | ھ | ہ | ة | ۃ | ۅ |

| gueh | rnūn | hā’ doachashmee | hā’ goal | tā’ marbuta | tā’ marbuta goal | kirghiz oe |

| ۆ | ۇ | ۈ | ۉ | ۋ | ې | ے |

| oe | u | yu | kirghiz yu | ve | e | yā’ barree |

| (see below for other alphabets) | ||||||

The Arabic script has been adapted for use in a wide variety of languages aside from Arabic, including Persian, Malay and Urdu, which are not Semitic. Such adaptations may feature altered or new characters to represent phonemes that do not appear in Arabic phonology. For example, the Arabic language lacks a voiceless bilabial plosive (the [p] sound), therefore many languages add their own letter to represent [p] in the script, though the specific letter used varies from language to language. These modifications tend to fall into groups: Indian and Turkic languages written in the Arabic script tend to use the Persian modified letters, whereas the languages of Indonesia tend to imitate those of Jawi. The modified version of the Arabic script originally devised for use with Persian is known as the Perso-Arabic script by scholars.

When the Arabic script is used to write Serbo-Croatian, Sorani, Kashmiri, Mandarin Chinese, or Uyghur, vowels are mandatory. The Arabic script can, therefore, be used as a true alphabet as well as an abjad, although it is often strongly, if erroneously, connected to the latter due to it being originally used only for Arabic.

Use of the Arabic script in West African languages, especially in the Sahel, developed with the spread of Islam. To a certain degree the style and usage tends to follow those of the Maghreb (for instance the position of the dots in the letters fāʼ and qāf).[14][15] Additional diacritics have come into use to facilitate the writing of sounds not represented in the Arabic language. The term ʻAjamī, which comes from the Arabic root for "foreign", has been applied to Arabic-based orthographies of African languages.

Table of writing styles

[edit]| Script or style | Alphabet(s) | Language(s) | Region | Derived from | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naskh | Arabic, Pashto, & others |

Arabic, Pashto, Sindhi, & others |

Every region where Arabic scripts are used | Sometimes refers to a very specific calligraphic style, but sometimes used to refer more broadly to almost every font that is not Kufic or Nastaliq. | |

| Nastaliq | Urdu, Shahmukhi, Persian, & others |

Urdu, Punjabi, Persian, Kashmiri & others |

Southern and Western Asia | Taliq | Used for almost all modern Urdu and Punjabi text, but only occasionally used for Persian. (The term "Nastaliq" is sometimes used by Urdu-speakers to refer to all Perso-Arabic scripts.) |

| Taliq | Persian | Persian | A predecessor of Nastaliq. | ||

| Kufic | Arabic | Arabic | Middle East and parts of North Africa | ||

| Rasm | Restricted Arabic alphabet | Mainly historical | Omits all diacritics including i'jam. Digital replication usually requires some special characters. See: ٮ ڡ ٯ (links to Wiktionary). |

Table of alphabets

[edit]| Alphabet | Letters | Additional Characters |

Script or Style | Languages | Region | Derived from: (or related to) |

Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabic | 28 | ^(see above) | Naskh, Kufi, Rasm, & others | Arabic | North Africa, West Asia | Phoenician, Aramaic, Nabataean | |

| Ajami script | 33 | ٻ تٜ تٰٜ | Naskh | Hausa, Yoruba, Swahili | West Africa, East Africa | Arabic | Abjad | documented use likely between the 15th to 18th century for Hausa, Mande, Pulaar, Swahili, Wolof, and Yoruba Languages |

| Aljamiado | 28 | Maghrebi, Andalusi variant; Kufic | Old Spanish, Andalusi Romance, Ladino, Aragonese, Valencian, Old Galician-Portuguese | Southwest Europe | Arabic | 8th–13th centuries for Andalusi Romance, 14th–16th centuries for the other languages | |

| Arebica | 30 | ڄ ە اٖى ي ڵ ںٛ ۉ ۆ | Naskh | Serbo-Croatian | Southeastern Europe | Perso-Arabic | Latest stage has full vowel marking |

| Arwi alphabet | 41 | ڊ ڍ ڔ صٜ ۻ ࢳ ڣ ࢴ ڹ ݧ | Naskh | Tamil | Southern India, Sri Lanka | Perso-Arabic | |

| Belarusian Arabic alphabet | 32 | ࢮ ࢯ | Naskh | Belarusian | Eastern Europe | Perso-Arabic | 15th / 16th century |

| Balochi Standard Alphabet(s) | 29 | ٹ ڈ ۏ ݔ ے | Naskh and Nastaliq | Balochi | South-West Asia | Perso-Arabic, also borrows multiple glyphs from Urdu | This standardization is based on the previous orthography. For more information, see Balochi writing. |

| Berber Arabic alphabet(s) | 33 | چ ژ ڞ ݣ ء | Various Berber languages | North Africa | Arabic | ||

| Burushaski | 53 | ݳ ݴ ݼ څ ڎ ݽ ڞ ݣ ݸ ݹ ݶ ݷ ݺ ݻ (see note) |

Nastaliq | Burushaski | South-West Asia (Pakistan) | Urdu | Also uses the additional letters shown for Urdu.(see below) Sometimes written with just the Urdu alphabet, or with the Latin alphabet. |

| Chagatai alphabet | 32 | ݣ | Nastaliq and Naskh | Chagatai | Central Asia | Perso-Arabic | ݣ is interchangeable with نگ and ڭ. |

| Dobrujan Tatar | 32 | Naskh | Dobrujan Tatar | Southeastern Europe | Chagatai | ||

| Galal | 32 | Naskh | Somali | Horn of Africa | Arabic | ||

| Jawi | 36 | چ ڠ ڤ ݢ ڽ ۏ | Naskh | Malay | Peninsular Malaysia, Sumatra and part of Borneo | Arabic | Since 1303 AD (Trengganu Stone) |

| Kashmiri | 44 | ۆ ۄ ؠ ێ | Nastaliq | Kashmiri | South Asia | Urdu | This orthography is fully voweled. 3 out of the 4 (ۆ, ۄ, ێ) additional glyphs are actually vowels. Not all vowels are listed here since they are not separate letters. For further information, see Kashmiri writing. |

| Kazakh Arabic alphabet | 35 | ٵ ٶ ۇ ٷ ۋ ۆ ە ھ ى ٸ ي | Naskh | Kazakh | Central Asia, China | Chagatai | In use since 11th century, reformed in the early 20th century, now official only in China |

| Khowar | 45 | ݯ ݮ څ ځ ݱ ݰ ڵ | Nastaliq | Khowar | South Asia | Urdu, however, borrows multiple glyphs from Pashto | |

| Kyrgyz Arabic alphabet | 33 | ۅ ۇ ۉ ۋ ە ى ي | Naskh | Kyrgyz | Central Asia | Chagatai | In use since 11th century, reformed in the early 20th century, now official only in China |

| Pashto | 45 | ټ څ ځ ډ ړ ږ ښ ګ ڼ ۀ ي ې ۍ ئ | Naskh and occasionally, Nastaliq | Pashto | South-West Asia, Afghanistan and Pakistan | Perso-Arabic | ګ is interchangeable with گ. Also, the glyphs ی and ې are often replaced with ے in Pakistan. |

| Pegon script | 35 | چ ڎ ڟ ڠ ڤ ڮ ۑ | Naskh | Javanese, Sundanese, Madurese | South-East Asia (Indonesia) | Arabic | |

| Persian | 32 | پ چ ژ گ | Naskh and Nastaliq | Persian (Farsi) | West Asia (Iran etc. ) | Arabic | Also known as Perso-Arabic. |

| Shahmukhi | 41 | ݪ ݨ | Nastaliq | Punjabi | South Asia (Pakistan) | Perso-Arabic | |

| Saraiki | 45 | ٻ ڄ ݙ ڳ | Nastaliq | Saraiki | South Asia (Pakistan) | Urdu | |

| Sindhi | 52 | ڪ ڳ ڱ گ ک پ ڀ ٻ ٽ ٿ ٺ ڻ ڦ ڇ چ ڄ ڃ ھ ڙ ڌ ڏ ڎ ڍ ڊ |

Naskh | Sindhi | South Asia (Pakistan) | Perso-Arabic | |

| Sorabe | 28 | Naskh | Malagasy | Madagascar | Arabic | ||

| Soranî | 33 | ڕ ڤ ڵ ۆ ێ | Naskh | Kurdish languages | Middle-East | Perso-Arabic | Vowels are mandatory, i.e. alphabet |

| Swahili Arabic script | 28 | Naskh | Swahili | Western and Southern Africa | Arabic | ||

| İske imlâ | 35 | ۋ | Naskh | Tatar | Volga region | Chagatai | Used prior to 1920. |

| Ottoman Turkish | 32 | ﭖ ﭺ ﮊ ﮒ ﯓ ئە | Ottoman Turkish | Ottoman Empire | Chagatai | Official until 1928 | |

| Urdu | 39+ (see notes) |

ٹ ڈ ڑ ں پ ھ چ ژ آ گ ے (see notes) |

Nastaliq | Urdu | South Asia | Perso-Arabic | 58 [citation needed] letters including digraphs representing aspirated consonants. بھ پھ تھ ٹھ جھ چھ دھ ڈھ کھ گھ |

| Uyghur | 32 | ئا ئە ھ ئو ئۇ ئۆ ئۈ ۋ ئې ئى | Naskh | Uyghur | China, Central Asia | Chagatai | Reform of older Arabic-script Uyghur orthography that was used prior to the 1950s. Vowels are mandatory, i.e. alphabet |

| Wolofal | 33 | ݖ گ ݧ ݝ ݒ | Naskh | Wolof | West Africa | Arabic, however, borrows at least one glyph from Perso-Arabic | |

| Xiao'erjing | 36 | ٿ س﮲ ڞ ي | Naskh | Sinitic languages | China, Central Asia | Chagatai | Used to write Chinese languages by Muslims living in China such as the Hui people. |

| Yaña imlâ | 29 | ئا ئە ئی ئو ئۇ ئ ھ | Naskh | Tatar | Volga region | İske imlâ alphabet | 1920–1927 replaced with Cyrillic |

| Huit | 29 | is dead ـع |

Current use

[edit]Today Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, and China are the main non-Arabic speaking states using the Arabic alphabet to write one or more official national languages, including Azerbaijani, Baluchi, Brahui, Persian, Pashto, Central Kurdish, Urdu, Sindhi, Kashmiri, Punjabi and Uyghur.[citation needed]

An Arabic alphabet is currently used for the following languages:[citation needed]

Middle East and Central Asia

[edit]- Arabic

- Azerbaijani (Torki) in Iran.

- Baluchi in Iran, in Pakistan's Balochistan region, Afghanistan and Oman[16]

- Garshuni (or Karshuni) originated in the 7th century, when Arabic became the dominant spoken language in the Fertile Crescent, but Arabic script was not yet fully developed or widely read, and so the Syriac alphabet was used. There is evidence that writing Arabic in this other set of letters (known as Garshuni) influenced the style of modern Arabic script. After this initial period, Garshuni writing has continued to the present day among some Syriac Christian communities in the Arabic-speaking regions of the Levant and Mesopotamia.

- Kazakh in Kazakhstan, China, Iran and Afghanistan

- Kurdish in Northern Iraq and Northwest Iran. (In Turkey and Syria the Latin script is used for Kurdish)

- Kyrgyz by its 150,000 speakers in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in northwestern China, Pakistan, Kyrgyzstan and Afghanistan

- Pashto in Afghanistan and Pakistan, and Tajikistan

- Persian in Iranian Persian and Dari in Afghanistan. It had former use in Tajikistan but is no longer used in Standard Tajik

- Southwestern Iranian languages as Lori dialects and Bakhtiari language[17][18]

- Turkmen in Turkmenistan,[verification needed] Afghanistan and Iran

- Uyghur changed to Latin script in 1969 and back to a simplified, fully voweled Arabic script in 1983

- Uzbek in Uzbekistan[verification needed] and Afghanistan

East Asia

[edit]- The Chinese language is written by some Hui in the Arabic-derived Xiao'erjing alphabet (see also Sini (script))

- The Turkic Salar language is written by some Salar in the Arabic alphabet

- Uyghur alphabet

South Asia

[edit]- Balochi in Pakistan and Iran

- Dari in Afghanistan

- Kashmiri in India and Pakistan (also written in Sharada and Devanagari although Kashmiri is more commonly written in Perso-Arabic Script)

- Pashto in Afghanistan and Pakistan

- Khowar in Northern Pakistan, also uses the Latin script

- Punjabi (Shahmukhi) in Pakistan, also written in the Brahmic script known as Gurmukhi in India

- Saraiki, written with a modified Arabic script – that has 45 letters

- Sindhi, a British commissioner in Sindh on August 29, 1857, ordered to change Arabic script[vague],[19] also written in Devanagari in India

- Aer language[20]

- Bhadrawahi language[21]

- Ladakhi (India), although it is more commonly written using the Tibetan script

- Balti (a Sino-Tibetan language), also rarely written in the Tibetan script

- Brahui language in Pakistan and Afghanistan[22]

- Burushaski or Burusho language, a language isolated to Pakistan.

- Urdu in Pakistan and India (and historically several other Hindustani languages). Urdu is the national language of Pakistan and a scheduled language in India. It is also one of several official languages in the Indian states of Jammu and Kashmir, Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, West Bengal and Telangana.

- Dogri, spoken by about five million people in India and Pakistan, chiefly in the Jammu region of Jammu and Kashmir and in Himachal Pradesh, but also in northern Punjab, although Dogri is more commonly written in Devanagari

- Arwi language (a mixture of Arabic and Tamil) uses the Arabic script together with the addition of 13 letters. It is mainly used in Sri Lanka and the South Indian state of Tamil Nadu for religious purposes. Arwi language is the language of Tamil Muslims

- Arabi Malayalam is Malayalam written in the Arabic script. The script has particular letters to represent the peculiar sounds of Malayalam. This script is mainly used in madrasas of the South Indian state of Kerala and of Lakshadweep.

- Rohingya language (Ruáingga) is a language spoken by the Rohingya people of Rakhine State, formerly known as Arakan (Rakhine), Burma (Myanmar). It is similar to Chittagonian language in neighboring Bangladesh[23] and sometimes written using the Roman script, or an Arabic-derived script known as Hanifi

- Ishkashimi language (Ishkashimi) in Afghanistan

Southeast Asia

[edit]- Malay in the Arabic script known as Jawi. In some cases it can be seen in the signboards of shops and market stalls, especially in rural or conservative areas of Malaysia, but it is no longer commonly used for everyday writing, being relegated instead to religious studies. Particularly in Brunei, Jawi is used in terms of writing or reading for Islamic religious educational programs in primary school, secondary school, college, or even higher educational institutes such as universities. In addition, some television programming uses Jawi, such as announcements, advertisements, news, social programs or Islamic programs

- co-official in Brunei

- co-official in the Malaysian states of Kelantan, Kedah, Pahang, and Terengganu.

- Indonesia, Jawi script is co-used with Latin in provinces of Aceh, Riau, Riau Islands and Jambi. The Javanese, Madurese and Sundanese also use another Arabic variant, the Pegon in Islamic writings and pesantren community.

- Southern Thailand

- Predominantly Muslim areas of the Philippines (especially Maguindanaon and Tausug)

- Ida'an language (also Idahan) a Malayo-Polynesian language spoken by the Ida'an people of Sabah, Malaysia[24]

- Cham language in Cambodia and Vietnam besides Western Cham script.

Europe

[edit]- Dobrujan Tatar in Romania and Bulgaria

Africa

[edit]- North Africa

- Arabic

- Berber languages have often been written in an adaptation of the Arabic alphabet. The use of the Arabic alphabet, as well as the competing Latin and Tifinagh scripts, has political connotations

- Tuareg language, (sometimes called Tamasheq) which is also a Berber language

- Coptic language of Egyptians as Coptic text written in Arabic letters[25]

- Northeast Africa

- Bedawi or Beja, mainly in northeastern Sudan

- Wadaad's writing, used in Somalia

- Nubian languages

- Dongolawi language or Andaandi language of Nubia, in the Nile Vale of northern Sudan

- Nobiin language, the largest Nubian language (previously known by the geographic terms Mahas and Fadicca/Fiadicca) is not yet standardized, being written variously in both Latinized and Arabic scripts; also, there have been recent efforts to revive the Old Nubian alphabet.[26][27]

- Fur language of Darfur, Sudan

- Southeast Africa

- Comorian, in the Comoros, currently side by side with the Latin alphabet (neither is official)

- Swahili, was originally written in Arabic alphabet, Swahili orthography is now based on the Latin alphabet that was introduced by Christian missionaries and colonial administrators

- West Africa

- Zarma language of the Songhay family. It is the language of the southwestern lobe of the West African nation of Niger, and it is the second leading language of Niger, after Hausa, which is spoken in south central Niger[28]

- Tadaksahak is a Songhay language spoken by the pastoralist Idaksahak of the Ménaka area of Mali[29]

- Hausa language uses an adaptation of the Arabic script known as Ajami, for many purposes, especially religious, but including newspapers, mass mobilization posters and public information[30]

- Dyula language is a Mandé language spoken in Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire and Mali.[31]

- Jola-Fonyi language of the Casamance region of Senegal[32]

- Balanta language a Bak language of west Africa spoken by the Balanta people and Balanta-Ganja dialect in Senegal

- Mandinka, widely but unofficially (known as Ajami), (another non-Latin script used is the N'Ko script)

- Fula, especially the Pular of Guinea (known as Ajami)

- Wolof (at zaouia schools), known as Wolofal.

- Yoruba, earliest attested history of use since 17th century, however earliest verifiable history of use dates to the 19th century. Yoruba Ajami used in Muslim praise verse, poetry, personal and esoteric use[33]

- Arabic script outside Africa

- In writings of African American slaves

- Writings of by Omar Ibn Said (1770–1864) of Senegal[34]

- The Bilali Document also known as Bilali Muhammad Document is a handwritten, Arabic manuscript[35] on West African Islamic law. It was written by Bilali Mohammet in the 19th century. The document is currently housed in the library at the University of Georgia

- Letter written by Ayuba Suleiman Diallo (1701–1773)

- Arabic Text From 1768[36]

- Letter written by Abdul Rahman Ibrahima Sori (1762–1829)

- In writings of African American slaves

Former use

[edit]With the establishment of Muslim rule in the subcontinent, one or more forms of the Arabic script were incorporated among the assortment of scripts used for writing native languages.[37] In the 20th century, the Arabic script was generally replaced by the Latin alphabet in the Balkans,[dubious – discuss] parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, and Southeast Asia, while in the Soviet Union, after a brief period of Latinisation,[38] use of Cyrillic was mandated. Turkey changed to the Latin alphabet in 1928 as part of an internal Westernizing revolution. After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, many of the Turkic languages of the ex-USSR attempted to follow Turkey's lead and convert to a Turkish-style Latin alphabet. However, renewed use of the Arabic alphabet has occurred to a limited extent in Tajikistan, whose language's close resemblance to Persian allows direct use of publications from Afghanistan and Iran.[39]

Africa

[edit]- Afrikaans (as it was first written among the "Cape Malays", see Arabic Afrikaans)

- Berber in North Africa, particularly Shilha in Morocco (still being considered, along with Tifinagh and Latin, for Central Atlas Tamazight)

- French by the Arabs and Berbers in Algeria and other parts of North Africa during the French colonial period

- Harari, by the Harari people of the Harari Region in Ethiopia. Now uses the Geʻez and Latin alphabets

- For the West African languages—Hausa, Fula, Mandinka, Wolof and others—the Latin alphabet has officially replaced Arabic transcriptions for use in literacy and education

- Kinyarwanda in Rwanda

- Kirundi in Burundi

- Malagasy in Madagascar (script known as Sorabe)

- Nubian

- Shona in Zimbabwe

- Somali (see wadaad's Arabic) has mostly used the Latin alphabet since 1972

- Songhay in West Africa, particularly in Timbuktu

- Swahili (has used the Latin alphabet since the 19th century)

- Yoruba in West Africa

Europe

[edit]- Albanian called Elifbaja shqip

- Aljamiado (Mozarabic, Berber, Aragonese, Portuguese[citation needed], Ladino, and Spanish, during and residually after the Muslim rule in the Iberian peninsula)

- Belarusian (among ethnic Tatars; see Belarusian Arabic alphabet)

- Bosnian (only for literary purposes; currently written in the Latin alphabet; Text example: مۉلٖىمۉ سه تهبٖى بۉژه = Molimo se tebi, Bože (We pray to you, O God); see Arebica)

- Crimean Tatar

- Greek in certain areas in Greece and Anatolia. In particular, Cappadocian Greek written in Perso-Arabic

- Polish (among ethnic Lipka Tatars)

Central Asia and Caucasus

[edit]- Adyghe language also known as West Circassian, is an official languages of the Republic of Adygea in the Russian Federation. It used Arabic alphabet before 1927

- Avar as well as other languages of Daghestan: Nogai, Kumyk, Lezgian, Lak and Dargwa

- Azeri in Azerbaijan (now written in the Latin alphabet and Cyrillic script in Azerbaijan)

- Bashkir (officially for some years from the October Revolution of 1917 until 1928, changed to Latin, now uses the Cyrillic script)

- Chaghatay across Central Asia

- Chechen (sporadically from the adoption of Islam; officially from 1917 until 1928)[40]

- Circassian and some other members of the Abkhaz–Adyghe family in the western Caucasus and sporadically – in the countries of Middle East, like Syria

- Ingush

- Karachay-Balkar in the central Caucasus

- Karakalpak

- Kazakh in Kazakhstan (until the 1930s, changed to Latin, currently using Cyrillic, phasing in Latin)

- Kyrgyz in Kyrgyzstan (until the 1930s, changed to Latin, now uses the Cyrillic script)

- Mandarin Chinese and Dungan, among the Hui people (script known as Xiao'erjing)

- Ottoman Turkish

- Tat in South-Eastern Caucasus

- Tatar before 1928 (changed to Latin Yañalif), reformed in the 1880s (İske imlâ), 1918 (Yaña imlâ – with the omission of some letters)

- Turkmen in Turkmenistan (changed to Latin in 1929, then to the Cyrillic script, then back to Latin in 1991)

- Uzbek in Uzbekistan (changed to Latin, then to the Cyrillic script, then back to Latin in 1991)

- Some Northeast Caucasian languages of the Muslim peoples of the USSR between 1918 and 1928 (many also earlier), including Chechen, Lak, etc. After 1928, their script became Latin, then later[when?] Cyrillic[citation needed]

South and Southeast Asia

[edit]- Acehnese in Sumatra, Indonesia

- Assamese in Assam, India

- Banjarese in Kalimantan, Indonesia

- Bengali in Bengal, Arabic scripts have been used historically in Bengali literature. See Dobhashi for further information.

- Maguindanaon in the Philippines

- Malay in Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia. Although Malay speakers in Brunei and Southern Thailand still use the script on a daily basis

- Minangkabau in Sumatra, Indonesia

- Pegon script of Javanese, Madurese and Sundanese in Indonesia, used only in Islamic schools and institutions

- Tausug in the Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia it can be used in Islamic schools in the Philippines

- Ternate-Tidore in Maluku, Indonesia

- Wolio in Buton, Indonesia

- Yakan practiced in Islamic schools in Basilan

Middle East

[edit]- Hebrew was written in Arabic letters in a number of places in the past[41][42]

- Northern Kurdish in Turkey and Syria was written in Arabic script until 1932, when a modified Kurdish Latin alphabet was introduced by Jaladat Ali Badirkhan in Syria

- Turkish in the Ottoman Empire was written in Arabic script until Mustafa Kemal Atatürk declared the change to Latin script in 1928. This form of Turkish is now known as Ottoman Turkish and is held by many to be a different language, due to its much higher percentage of Persian and Arabic loanwords (Ottoman Turkish alphabet)

Unicode

[edit]As of Unicode 17.0, the following ranges encode Arabic characters:

- Arabic (0600–06FF)

- Arabic Supplement (0750–077F)

- Arabic Extended-A (08A0–08FF)

- Arabic Extended-B (0870–089F)

- Arabic Extended-C (10EC0–10EFF)

- Arabic Presentation Forms-A (FB50–FDFF)

- Arabic Presentation Forms-B (FE70–FEFF)

- Arabic Mathematical Alphabetic Symbols (1EE00–1EEFF)

- Rumi Numeral Symbols (10E60–10E7F)

- Indic Siyaq Numbers (1EC70–1ECBF)

- Ottoman Siyaq Numbers (1ED00–1ED4F)

Additional letters used in other languages

[edit]Assignment of phonemes to graphemes

[edit]- ∅ = phoneme absent from language

| Language family | Austron. | Dravid. | Turkic | Indo-European | Niger–Con. | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language/script | Pegon | Jawi | Arwi | Azeri | Kazakh | Uyghur | Uzbek | Sindhi | Punjabi | Urdu | Persian | Pashto[a] | Balochi | Kurdish | Swahili |

| /t͡ʃ/ | چ | ||||||||||||||

| /ʒ/ | ∅ | ژ | |||||||||||||

| /p/ | ڤ | ڣ | پ | ||||||||||||

| /g/ | ؼ | ݢ | ࢴ | ق | گ | ڠ | |||||||||

| /v/ | ∅ | ۏ | و | ۆ | ۋ | و | ∅ | ڤ | |||||||

| /ŋ/ | ڠ | ࢳ | ∅ | ڭ | نگ | ڱ | ن | ∅ | نݝ | ||||||

| /ɲ/ | ۑ | ڽ | ݧ | ∅ | ڃ | ن | ∅ | نْي | |||||||

| /ɳ/ | ∅ | ڹ | ∅ | ڻ | ݨ | ن | ∅ | ڼ | ∅ | ||||||

Table of additional letters in other languages

[edit]| Letter[A] | Use & Pronunciation | Unicode | i'jam & other additions | Shape | Similar Arabic Letter(s) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U+ | [B] | [C] | above | below | ||||

| Additional letters with additional marks | ||||||||

| پ | Pe, used to represent the phoneme /p/ in Persian, Pashto, Punjabi, Khowar, Sindhi, Urdu, Kurdish, Kashmiri; it can be used in Arabic to describe the phoneme /p/ otherwise it is written ب /b/. | U+067E | ﮹ | none | 3 dots | ٮ | ب | |

| ݐ | used to represent the equivalent of the Latin letter Ƴ (palatalized glottal stop /ʔʲ/) in some African languages such as Fulfulde. | U+0750 | ﮳﮳﮳ | none | 3 dots (horizontal) |

ٮ | ب | |

| ٻ | B̤ē, used to represent a voiced bilabial implosive /ɓ/ in Hausa, Sindhi and Saraiki. | U+067B | ﮾ | none | 2 dots (vertically) |

ٮ | ب | |

| ڀ | represents an aspirated voiced bilabial plosive /bʱ/ in Sindhi. | U+0680 | ﮻ | none | 4 dots | ٮ | ب | |

| ٺ | Ṭhē, represents the aspirated voiceless retroflex plosive /ʈʰ/ in Sindhi. | U+067A | ﮽ | 2 dots (vertically) |

none | ٮ | ت | |

| ټ | Ṭē, used to represent the phoneme /ʈ/ in Pashto. | U+067C | ﮿ | ﮴ | 2 dots | ring | ٮ | ت |

| ٽ | Ṭe, used to represent the phoneme (a voiceless retroflex plosive /ʈ/) in Sindhi | U+067D | ﮸ | 3 dots (inverted) |

none | ٮ | ت | |

| ﭦ | Ṭe, used to represent Ṭ (a voiceless retroflex plosive /ʈ/) in Punjabi, Kashmiri, Urdu. | U+0679 | ◌ؕ | small ط |

none | ٮ | ت | |

| ٿ | Teheh, used in Sindhi and Rajasthani (when written in Sindhi alphabet); used to represent the phoneme /t͡ɕʰ/ (pinyin q) in Chinese Xiao'erjing. | U+067F | ﮺ | 4 dots | none | ٮ | ت | |

| ڄ | represents the "c" voiceless dental affricate /t͡s/ phoneme in Bosnian | U+0684 | ﮾ | none | 2 dots (vertically) |

ح | ج | |

| ڃ | represents the "ć" voiceless alveolo-palatal affricate /t͡ɕ/ phoneme in Bosnian. | U+0683 | ﮵ | none | 2 dots | ح | ج | |

| چ | Che, used to represent /t͡ʃ/ ("ch"). It is used in Persian, Pashto, Punjabi, Urdu, Kashmiri and Kurdish. /ʒ/ in Egypt. | U+0686 | ﮹ | none | 3 dots | ح | ج | |

| څ | Ce, used to represent the phoneme /t͡s/ in Pashto. | U+0685 | ﮶ | 3 dots | none | ح | خ | |

| ݗ | represents the "đ" voiced alveolo-palatal affricate /d͡ʑ/ phoneme in Bosnian. Also used to represent the letter X in Afrikaans. | U+0757 | ﮴ | 2 dots | none | ح | خ | |

| ځ | Źim, used to represent the phoneme /d͡z/ in Pashto. | U+0681 | ◌ٔ | Hamza | none | ح | خ | |

| ڎ | Used to represent the phoneme /ɖ/ in Somali | U+068E | 3 dots | |||||

| ݙ | used in Saraiki to represent a Voiced alveolar implosive /ɗ̢/. | U+0759 | ﯀ | ﮾ | small ط |

2 dots (vertically) |

د | د |

| ڊ | used in Saraiki to represent a voiced retroflex implosive /ᶑ/. | U+068A | ﮳ | none | 1 dot | د | د | |

| ڈ | Ḍal, used to represent a Ḍ (a voiced retroflex plosive /ɖ/) in Punjabi, Kashmiri and Urdu. | U+0688 | ◌ؕ | small ط | none | د | د | |

| ڌ | Dhal, used to represent the phoneme /d̪ʱ/ in Sindhi | U+068C | ﮴ | 2 dots | none | د | د | |

| ډ | Ḍal, used to represent the phoneme /ɖ/ in Pashto. | U+0689 | ﮿ | none | ring | د | د | |

| ڑ | Ṛe, represents a retroflex flap /ɽ/ in Punjabi and Urdu. | U+0691 | ◌ؕ | small ط | none | ر | ر | |

| ړ | Ṛe, used to represent a retroflex lateral flap in Pashto. | U+0693 | ﮿ | none | ring | ر | ر | |

| ݫ | used in Ormuri to represent a voiced alveolo-palatal fricative /ʑ/, as well as in Torwali. | U+076B | ﮽ | 2 dots (vertically) |

none | ر | ر | |

| ژ | Že / zhe, used to represent the voiced postalveolar fricative /ʒ/ in, Persian, Pashto, Kurdish, Urdu, Punjabi and Uyghur. | U+0698 | ﮶ | 3 dots | none | ر | ز | |

| ږ | Ǵe / ẓ̌e, used to represent the phoneme /ʐ/ /ɡ/ /ʝ/ in Pashto. | U+0696 | ﮲ | ﮳ | 1 dot | 1 dot | ر | ز |

| ڕ | used in Kurdish to represent rr /r/ in Soranî dialect. | U+0695 | ٚ | none | V pointing down | ر | ر | |

| ݭ | used in Kalami to represent a voiceless retroflex fricative /ʂ/, and in Ormuri to represent a voiceless alveolo-palatal fricative /ɕ/. | U+076D | ﮽ | 2 dots vertically | none | س | س | |

| ݜ | used in Shina to represent a voiceless retroflex fricative /ʂ/. | U+075C | ﮺ | 4 dots | none | س | ش | |

| ښ | X̌īn / ṣ̌īn, used to represent the phoneme /x/ /ʂ/ /ç/ in Pashto. | U+069A | ﮲ | ﮳ | 1 dot | 1 dot | س | س |

| ڜ | Used in Wakhi to represent the phoneme /ʂ/. | U+069C | ﮶ | ﮹ | 3 dots | 3 dots | س | ش |

| ڞ | Used to represent the phoneme /tsʰ/ (pinyin c) in Chinese. | U+069E | ﮶ | 3 dots | none | ص | ض | |

| ڠ | Nga /ŋ/ in the Jawi script and Pegon script. | U+06A0 | ﮶ | 3 dots | none | ع | غ | |

| ڤ | Ve, used in Kurdish to represent /v/, it can be used in Arabic to describe the phoneme /v/ otherwise it is written ف /f/. Pa, used in the Jawi script and Pegon script to represent /p/. | U+06A4 | ﮶ | 3 dots | none | ڡ | ف | |

| ڥ | Vi, used in Algerian Arabic and Tunisian Arabic when written in Arabic script to represent the sound /v/ if needed. | U+06A5 | ﮹ | none | 3 dots | ڡ | ف | |

| ڨ | Ga, used to represent the voiced velar plosive /ɡ/ in Algerian and Tunisian. | U+06A8 | ﮶ | 3 dots | none | ٯ | ق | |

| ڭ | Ng, used to represent the /ŋ/ phone in Ottoman Turkish, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, and Uyghur.

Used to represent /ɡ/ in Morocco and in many dialects of Algerian. |

U+06AD | ﮶ | 3 dots | none | ك | ك | |

| ڬ | Gaf, represents a voiced velar plosive /ɡ/ in the Jawi script of Malay. | U+06AC | ﮲ | 1 dot | none | ك | ك | |

| ݢ | U+0762 | ﮲ | 1 dot | none | ک | ك | ||

| گ | Gaf, represents a voiced velar plosive /ɡ/ in Persian, Pashto, Punjabi, Somali, Kyrgyz, Kazakh, Kurdish, Uyghur, Mesopotamian Arabic, Urdu and Ottoman Turkish. | U+06AF | line | horizontal line | none | ک | ك | |

| ګ | Gaf, used to represent the phoneme /ɡ/ in Pashto. | U+06AB | ﮿ | ring | none | ک | ك | |

| ؼ | Gaf, represents a voiced velar plosive /ɡ/ in the Pegon script of Indonesian. | U+08B4 | ﮳ | none | 3 dots | ک | ك | |

| ڱ | represents the Velar nasal /ŋ/ phoneme in Sindhi. | U+06B1 | ﮴ | 2 dots + horizontal line |

none | ک | ك | |

| ڳ | represents a voiced velar implosive /ɠ/ in Sindhi and Saraiki | U+06B1 | ﮾ | horizontal line |

2 dots | ک | ك | |

| ݣ | used to represent the phoneme /ŋ/ (pinyin ng) in Chinese. | U+0763 | ﮹ | none | 3 dots | ک | ك | |

| ݪ | used in Marwari to represent a retroflex lateral flap /ɺ̢/, and in Kalami to represent a voiceless lateral fricative /ɬ/. | U+076A | line | horizontal line |

none | ل | ل | |

| ࣇ | ࣇ – or alternately typeset as لؕ – is used in Punjabi to represent voiced retroflex lateral approximant /ɭ/[43] | U+08C7 | ◌ؕ | small ط | none | ل | ل | |

| لؕ | U+0644 U+0615 | |||||||

| ڵ | used in Kurdish to represent ll /ɫ/ in Soranî dialect. Represents the "lj" palatal lateral approximant /ʎ/ phoneme in Bosnian. | U+06B5 | ◌ٚ | V pointing down | none | ل | ل | |

| ڼ | represents the retroflex nasal /ɳ/ phoneme in Pashto. | U+06BC | ﮲ | ﮿ | 1 dot | ring | ں | ن |

| ڻ | represents the retroflex nasal /ɳ/ phoneme in Sindhi. | U+06BB | ◌ؕ | small ط | none | ں | ن | |

| ݨ | used in Punjabi to represent /ɳ/ and Saraiki to represent /ɲ/. | U+0768 | ﮲ | ﯀ | 1 dot + small ط | none | ں | ن |

| ڽ | Nya /ɲ/ in the Jawi script ڽـ ـڽـ ڽ., The isolated ڽ and final ـڽ resemble the form ڽ, while the initial ڽـ and medial forms ـڽـ, resemble the form پ. | U+06BD | ﮶ | 3 dots | none | ں | ن | |

| ݩ | represents the "nj" palatal nasal /ɲ/ phoneme in Bosnian. | U+0769 | ﮲ | ◌ٚ | 1 dot V pointing down |

none | ں | ن |

| ۅ | Ö, used to represent the phoneme /ø/ in Kyrgyz. | U+0624 | ◌̵ | Strikethrough[D] | none | و | و | |

| ﻭٓ | Uu, used to represent the phoneme /uː/ in Somali. | ﻭ + ◌ٓ U+0648 U+0653 | ◌ٓ | Madda | none | و | ﻭ + ◌ٓ | |

| ۏ | Va in the Jawi script. | U+06CF | ﮲ | 1 dot | none | و | و | |

| ۋ | represents a /v/ in Kyrgyz, Uyghur, and Old Tatar; and /w, ʊw, ʉw/ in Kazakh; also formerly used in Nogai. | U+06CB | ﮶ | 3 dots | none | و | و | |

| ۆ | represents "o" /oː/ in Kurdish, "ü" /y/ in Azerbaijani, and /ø/ in Uyghur as part of the digraph ئۆ. It represents the "u" /u/ phoneme in Bosnian. | U+06C6 | ◌ٚ | V pointing down | none | و | و | |

| ۇ | U, used to represents the /u/ phoneme in Azerbaijani, Kazakh, Kyrgyz and Uyghur. | U+06C7 | ◌ُ | Damma[E] | none | و | و | |

| ۉ | represents the "o" /ɔ/ phoneme in Bosnian. Also used to represent /ø/ in Kyrgyz. | U+06C9 | ◌ٛ | V pointing up | none | و | و | |

| ىٓ | Ii, used to represent the phoneme /iː/ in Somali and Saraiki. | U+0649 U+0653 | ◌ٓ | Madda | none | ى | ي | |

| ې | Pasta Ye, used to represent the phoneme /e/ in Pashto and Uyghur. | U+06D0 | ﮾ | none | 2 dots vertical | ى | ي | |

| ۍ | X̌əźīna ye Ye, used to represent the phoneme [əi] in Pashto. | U+06CD | line | horizontal line |

none | ى | ي | |

| ۑ | Nya /ɲ/ in the Pegon script. | U+06D1 | ﮹ | none | 3 dots | ى | ي | |

| ێ | represents ê /eː/ in Kurdish. | U+06CE | ◌ٚ | V pointing down | 2 dots (start + mid) |

ى | ي | |

| Additional letters with shape alteration | ||||||||

| ک | Khē, represents /kʰ/ in Sindhi. | U+06A9 | none | none | none | ک | ك | |

| ڪ | "Swash kāf" is a stylistic variant of ك in Arabic, but represents un- aspirated /k/ in Sindhi. | U+06AA | none | none | none | ڪ | ك | |

| ھ ھ |

Do-chashmi he (two-eyed hāʼ), used in digraphs for aspiration /ʰ/ and breathy voice /ʱ/ in Punjabi and Urdu. Also used to represent /h/ in Kazakh, Sorani and Uyghur.[F] | U+06BE | none | none | none | ھ | ه / هـ | |

| ە | Ae, used represent /æ/ and /ɛ/ in Kazakh, Sorani and Uyghur. | U+06D5 | none | none | none | ه | ه / هـ | |

| ے | Baṛī ye ('big yāʼ'), is a stylistic variant of ي in Arabic, but represents "ai" or "e" /ɛː/, /eː/ in Urdu and Punjabi. | U+06D2 | none | none | none | ے | ي | |

| Additional Digraph letters | ||||||||

| أو | Oo, used to represent the phoneme /oː/ in Somali. | U+0623 U+0648 | ◌ٔ | Hamza | none | او | أ + و | |

| اٖى | represents the "i" /i/ phoneme in Bosnian. | U+0627 U+0656 U+0649 | ◌ٖ | Alef | none | اى | اٖ + ى | |

| أي | Ee, used to represent the phoneme /eː/ in Somali. | U+0623 U+064A | ◌ٔ | ﮵ | Hamza | 2 dots | اى | أ + ي |

- ^ letter or digraph

- ^ Joined to the letter, closest to the letter, on the first letter, or above.

- ^ Further away from the letter, or on the second letter, or below.

- ^ A variant that end up with loop also exists.

- ^ Although the letter also known as Waw with Damma, some publications and fonts features filled Damma that looks similar to comma.

- ^ Shown in Naskh (top) and Nastaliq (bottom) styles. The Nastaliq version of the connected forms are connected to each other, because the tatweel character U+0640 used to show the other forms does not work in many Nastaliq fonts.

Letter construction

[edit]Most languages that use alphabets based on the Arabic alphabet use the same base shapes. Most additional letters in languages that use alphabets based on the Arabic alphabet are built by adding (or removing) diacritics to existing Arabic letters. Some stylistic variants in Arabic have distinct meanings in other languages. For example, variant forms of kāf ك ک ڪ are used in some languages and sometimes have specific usages. In Urdu and some neighbouring languages, the letter Hā has diverged into two forms ھ dō-čašmī hē and ہ ہـ ـہـ ـہ gōl hē,[44] while a variant form of ي yā referred to as baṛī yē ے is used at the end of some words.[44]

Table of letter components

[edit]See also

[edit]- Arabic (Unicode block)

- Eastern Arabic numerals (digit shapes commonly used with Arabic script)

- History of the Arabic alphabet

- Transliteration of Arabic

- Xiao'erjing

Explanatory notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Daniels, Peter T.; Bright, William, eds. (1996). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press, Inc. p. 559. ISBN 978-0195079937.

- ^ "Arabic Alphabet". Encyclopædia Britannica online. Archived from the original on 26 April 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ Vaughan, Don. "The World's 5 Most Commonly Used Writing Systems". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 29 July 2023. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- ^ Cham romanization table background. Library of Congress

- ^ Mahinnaz Mirdehghan. 2010. Persian, Urdu, and Pashto: A comparative orthographic analysis. Writing Systems Research Vol. 2, No. 1, 9–23.

- ^ "Exposición Virtual. Biblioteca Nacional de España". Bne.es. Archived from the original on 18 February 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ Ahmad, Syed Barakat. (11 January 2013). Introduction to Qur'anic script. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-11138-9. OCLC 1124340016.

- ^ Gruendler, Beatrice (1993). The Development of the Arabic Scripts: From the Nabatean Era to the First Islamic Century According to Dated Texts. Scholars Press. p. 1. ISBN 9781555407100.

- ^ Healey, John F.; Smith, G. Rex (13 February 2012). "II - The Origin of the Arabic Alphabet". A Brief Introduction to The Arabic Alphabet. Saqi. ISBN 9780863568817.

- ^ Senner, Wayne M. (1991). The Origins of Writing. U of Nebraska Press. p. 100. ISBN 0803291671.

- ^ "Nabataean abjad". www.omniglot.com. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ Naveh, Joseph. "Nabatean Language, Script and Inscriptions" (PDF).

- ^ Taylor, Jane (2001). Petra and the Lost Kingdom of the Nabataeans. I.B.Tauris. p. 152. ISBN 9781860645082.

- ^ "Zribi, I., Boujelbane, R., Masmoudi, A., Ellouze, M., Belguith, L., & Habash, N. (2014). A Conventional Orthography for Tunisian Arabic. In Proceedings of the Language Resources and Evaluation Conference (LREC), Reykjavík, Iceland".

- ^ Brustad, K. (2000). The syntax of spoken Arabic: A comparative study of Moroccan, Egyptian, Syrian, and Kuwaiti dialects. Georgetown University Press.

- ^ "Sayad Zahoor Shah Hashmii". baask.com.

- ^ Sarlak, Riz̤ā (2002). "Dictionary of the Bakhtiari dialect of Chahar-lang". google.com.eg.

- ^ Iran, Mojdeh (5 February 2011). "Bakhtiari Language Video (bak) بختياري ها! خبری مهم" – via Vimeo.

- ^ "Pakistan should mind all of its languages!". tribune.com.pk. June 2011.

- ^ "Ethnologue". Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ "Ethnologue". Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ "The Bible in Brahui". Worldscriptures.org. Archived from the original on 30 October 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ "Rohingya Language Book A-Z". Scribd.

- ^ "Ida'an". scriptsource.org.

- ^ "The Coptic Studies' Corner". stshenouda.com. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ^ "--The Cradle of Nubian Civilisation--". thenubian.net. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ^ "2 » AlNuba egypt". 19 July 2012. Archived from the original on 19 July 2012.

- ^ "Zarma". scriptsource.org.

- ^ "Tadaksahak". scriptsource.org.

- ^ "Lost Language — Bostonia Summer 2009". bu.edu.

- ^ "Dyula". scriptsource.org.

- ^ "Jola-Fonyi". scriptsource.org.

- ^ "African Arabic-Script Languages Title: From the 'Sacred' to the 'Profane': the Yoruba Ajami Script and the Challenges of a Standard Orthography". ResearchGate. October 2021.

- ^ "Ibn Sayyid manuscript". Archived from the original on 8 September 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ^ "Muhammad Arabic letter". Archived from the original on 8 September 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ^ "Charno Letter". Muslims In America. Archived from the original on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ Asani, Ali S. (2002). Ecstasy and enlightenment : the Ismaili devotional literature of South Asia. Institute of Ismaili Studies. London: I.B. Tauris. p. 124. ISBN 1-86064-758-8. OCLC 48193876.

- ^ Alphabet Transitions – The Latin Script: A New Chronology – Symbol of a New Azerbaijan Archived 2007-04-03 at the Wayback Machine, by Tamam Bayatly

- ^ Sukhail Siddikzoda. "Tajik Language: Farsi or Not Farsi?" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 June 2006.

- ^ "Brief history of writing in Chechen". Archived from the original on 23 December 2008.

- ^ p. 20, Samuel Noel Kramer. 1986. In the World of Sumer: An Autobiography. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

- ^ J. Blau. 2000. Hebrew written in Arabic characters: An instance of radical change in tradition. (In Hebrew, with English summary). In Heritage and Innovation in Judaeo-Arabic Culture: Proceedings of the Sixth Conference of the Society For Judaeo-Arabic Studies, p. 27–31. Ramat Gan.

- ^ Lorna Priest Evans; M. G. Abbas Malik. "Proposal to encode ARABIC LETTER LAM WITH SMALL ARABIC LETTER TAH ABOVE in the UCS" (PDF). www.unicode.org. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ a b "Urdu Alphabet". www.user.uni-hannover.de. Archived from the original on 11 September 2019. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

External links

[edit]- Unicode collation charts—including Arabic letters, sorted by shape

- "Why the right side of your brain doesn't like Arabic"

- Arabic fonts by SIL's Non-Roman Script Initiative

- Alexis Neme and Sébastien Paumier (2019), "Restoring Arabic vowels through omission-tolerant dictionary lookup", Lang Resources & Evaluation, Vol. 53, pp. 1–65. arXiv:1905.04051; doi:10.1007/s10579-019-09464-6

- "Preliminary proposal to encode Arabic Crown Letters" (PDF). Unicode.

- "Proposal to encode Arabic Crown Letters" (PDF). Unicode.

Arabic script

View on GrokipediaHistory

Origins and early development

The Arabic script traces its distant origins to ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs through the Proto-Sinaitic script (ca. 1850–1500 BCE). Semitic-speaking peoples in the Sinai Peninsula and Egypt adapted select Egyptian hieroglyphs using the acrophonic principle—assigning the initial consonant sound of the Semitic word for the depicted object—to form the earliest known abjad, representing consonants in a simplified linear manner. This Proto-Sinaitic script evolved into Proto-Canaanite and subsequently the Phoenician alphabet (ca. 11th century BCE), which gave rise to the Aramaic alphabet. The Nabataean variant of late Aramaic then developed into the distinct Arabic script by the 4th century CE.[8][9] Although sharing this ancestral lineage, the Arabic script differs profoundly from Egyptian hieroglyphs in appearance and function. Hieroglyphs comprised a complex pictorial and logographic system with hundreds of symbols that could represent words, syllables, or sounds, whereas Arabic is a cursive, right-to-left abjad primarily denoting consonants with connected letter forms in fluid, joined writing. The Arabic script originated as a derivative of the Nabataean variant of the late Aramaic alphabet, which itself evolved from the earlier Phoenician script around the 4th century CE in the Arabian Peninsula and surrounding regions.[10] This development occurred among Arab tribes in northern Arabia and the Levant, where the Nabataean kingdom (c. 320 BCE–106 CE) facilitated cultural and linguistic exchanges through trade routes connecting Petra, Syria, and the Hijaz.[11] The script's emergence reflects a gradual adaptation of Aramaic's 22-letter consonantal system to accommodate Arabic phonetics, expanding to 28 letters by incorporating additional sounds unique to Arabic.[12] Key evidence of proto-Arabic forms appears in early inscriptions, such as the Namara inscription from 328 CE, discovered near Damascus in modern-day Syria. This funerary stele for the Lakhmid king Imru' al-Qays is written in the Nabataean script but employs classical Arabic language, marking it as one of the oldest dated attestations of written Arabic and demonstrating the script's transitional use for Arabic texts.[13] Similarly, the Zabad inscription from 512 CE, found near Aleppo, is a trilingual dedication in Greek, Syriac, and Arabic on a church lintel, with the Arabic portion showcasing emerging cursive tendencies and terms like "al-ilah" (the God), highlighting the script's role in pre-Islamic religious and communal contexts.[14] These artifacts, primarily from funerary and dedicatory purposes, illustrate the script's initial application in northern Arabian and Syrian territories influenced by nomadic and settled Arab communities.[11] The transition from angular, monumental forms to more fluid, cursive styles was driven by practical needs in trade, administration, and everyday writing on perishable materials like papyrus during the pre-Islamic era. Nabataean inscriptions, often chiseled in stone for durability, featured rigid lines suited to lapidary work, but as Arabic speakers adopted the script for broader commercial exchanges along caravan routes, ligatures and connections between letters began to appear, smoothing the forms for quicker inscription.[10] This evolution is evident in the semi-cursive Nabataean examples from the 2nd century BCE onward, which prefigure the interconnected nature of mature Arabic writing.[11] A representative example of letter evolution is the Arabic alif (ا), which developed from the Phoenician aleph (𐤀), an ox-head symbol simplified in Aramaic to a vertical stroke and further adapted in Nabataean to a slanted or hooked form before straightening in proto-Arabic by the 4th century CE.[11] Such changes preserved the consonantal value while aligning with Arabic's phonetic requirements, laying the groundwork for the script's later refinements.[12]Spread and evolution in the Islamic era

The rise of Islam in the 7th century facilitated the rapid dissemination of the Arabic script across vast territories through military conquests, transforming it from a regional writing system into a vehicle for religious, administrative, and cultural expression. Following the death of Prophet Muhammad in 632 CE, Arab Muslim armies expanded into Persia by 651 CE under the Rashidun Caliphate and later the Umayyads, conquering the Sasanian Empire and introducing Arabic script for Quranic dissemination and governance. Similarly, conquests reached North Africa by the late 7th century, with Umayyad forces capturing Egypt in 642 CE and advancing westward to establish script use in official documents and Islamic texts, laying the groundwork for regional linguistic integrations. These expansions, extending to the Iberian Peninsula and Central Asia by the 8th century, prompted initial adaptations, such as the incorporation of Persian sounds into the script for administrative purposes in conquered regions.[15][16][17] Under the Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE), efforts to standardize the Arabic script intensified to support the empire's administrative needs and the accurate transmission of the Quran. Caliph ʿAbd al-Malik (r. 685–705 CE) played a pivotal role, commissioning the codification of the Kufic script between 684 and 692 CE, an angular, geometric style suited for monumental inscriptions like those on the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. This script, derived from earlier Hijazi forms, became the primary medium for Quranic manuscripts, emphasizing clarity and aesthetic rigidity without vowels or extensive diacritics in early versions. The Abbasid Caliphate (750–1258 CE) further refined this standardization in the 8th and 9th centuries, with Baghdad emerging as a center for script evolution; Kufic continued for religious texts while transitioning toward more cursive styles to enhance legibility in expanding literary and bureaucratic contexts.[18][19][18] To address ambiguities in consonant differentiation, particularly for non-Arabic speakers reciting the Quran, diacritical marks known as i'jam were introduced around 684 CE by the grammarian Abu al-Aswad al-Du'ali (d. 688 CE), a companion of Ali ibn Abi Talib. Commissioned by the Umayyad governor of Basra, al-Du'ali devised a system of dots placed above, below, or beside letters to distinguish similar forms, such as ب (bāʾ), ت (tāʾ), ث (thāʾ), ن (nūn), ي (yāʾ), and ى (alif maqṣūrah), thereby preventing misreadings in sacred texts. This innovation, initially applied to Quranic codices, marked a crucial step in script legibility during the early Islamic expansions.[20][21] Building on this foundation, vowel pointing or tashkil was innovated in the 8th century by the Basran scholar Khalil ibn Ahmad al-Farahidi (d. 786 CE) to indicate short vowels and phonetic nuances more precisely. Al-Farahidi replaced earlier colored dots with a refined set of symbols—such as fatḥah (a horizontal line for /a/), kasrah (a diagonal line for /i/), and ḍammah (a curl for /u/)—derived from letter shapes, enabling accurate recitation for diverse linguistic communities. His system, integrated into Quranic and grammatical works like Kitāb al-ʿAyn, became standard by the 11th century, supporting the script's adaptability in Persian and North African contexts where vowel systems differed from Arabic.[22][23]Modern standardization and reforms

The Tanzimat reforms in the Ottoman Empire from 1839 to 1876 marked a pivotal era for the Arabic script's adaptation to modern printing technologies, as the expansion of printing presses enabled the widespread dissemination of official edicts and educational materials in Arabic script, overcoming earlier restrictions on Muslim use of movable type.[24] This period also saw early proposals for orthographic simplification to address the script's complexities in representing Turkish phonetics, notably through Iranian intellectual Mirza Malkum Khan's 1860s reform plan, which advocated adding diacritics and new letters to enhance readability and literacy rates.[25] These efforts laid groundwork for later script reforms by highlighting the need for standardization amid growing print culture. In post-colonial contexts, Egypt's 1920s intellectual and journalistic movements pushed for Arabic language consistency to support national identity and print media expansion, culminating in the 1932 founding of the Academy of the Arabic Language (Majmaʿ al-Lughah al-ʿArabīyah) by King Fuad I, which focused on unifying orthography, coining modern terms, and resolving ambiguities in diacritic usage.[26] Similar standardization initiatives occurred across Arab states, aiming to bridge classical Arabic with contemporary needs in education and administration. Reforms in non-Arab countries diverged more radically; in 1928, Turkey under Mustafa Kemal Atatürk enacted Law No. 1353, mandating a switch from the Arabic script to a Latin-based alphabet to boost literacy from around 10% to over 20% within a decade and align with Western modernization, effectively severing ties to Ottoman-Islamic traditions.[27] In Iran, Reza Shah Pahlavi's 1930s cultural policies included orthographic tweaks to the Perso-Arabic alphabet, such as standardizing short vowel markings and reducing optional ligatures through the 1935 Academy of Iran, to better suit Persian phonology without a full script change.[28] Contemporary efforts have emphasized digital adaptation and cultural preservation; in the 1980s, Saudi Arabia advanced Arabic script standards for computing, with initiatives at institutions like King Saud University developing early font encoding systems to accommodate the script's cursive forms in word processors and databases, paving the way for global digital typography.[29] Since the 2000s, UNESCO has supported projects to safeguard endangered Arabic script variants, including digitization of Ajami manuscripts—modified Arabic scripts for African languages like Wolof and Hausa—through partnerships like the British Library's Endangered Archives Programme, such as the pilot project EAP915, which identified and cataloged 807 endangered Arabic manuscripts in regions including Ivory Coast. More recently, as of 2023, the EAP has digitized over 100,000 pages of Ajami materials across West Africa, including projects for Mandinka and Wolof languages.[30][31]Core Features

Alphabet and basic letters

The Arabic script is fundamentally an abjad, a writing system that primarily represents consonants while vowels are either omitted in standard orthography or indicated through optional diacritics, setting it apart from full alphabets like the Latin script that include inherent vowel markers. This consonantal focus facilitates concise writing but requires contextual knowledge for accurate pronunciation, particularly among native speakers. The standard Arabic alphabet comprises 28 letters, each with a distinct name and phonemic value, derived from the ancient Nabataean and Aramaic scripts but refined over centuries. Unlike scripts with case distinctions, Arabic employs a unicase design, meaning there are no uppercase or lowercase forms; instead, letters adapt through four positional variants—initial (at the start of a word), medial (within a word), final (at the end of a word), and isolated (standalone or after a non-connecting letter)—to suit the cursive flow of connected writing. This positional flexibility is a core feature enabling the script's elegant, flowing appearance without altering the letter's essential identity. The following table lists the 28 core letters in their isolated forms, along with their conventional names and approximate International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) phonemic values, ordered from right to left as per Arabic reading direction. These phonemes represent standard Modern Standard Arabic pronunciations, though regional dialects may vary slightly.| Isolated Form | Name | IPA Phoneme |

|---|---|---|

| ا | alif | /ʔ/ or /aː/ |

| ب | bāʾ | /b/ |

| ت | tāʾ | /t/ |

| ث | thāʾ | /θ/ |

| ج | jīm | /dʒ/ |

| ح | ḥāʾ | /ħ/ |

| خ | khāʾ | /x/ |

| د | dāl | /d/ |

| ذ | dhāl | /ð/ |

| ر | rāʾ | /r/ |

| ز | zāy | /z/ |

| س | sīn | /s/ |

| ش | shīn | /ʃ/ |

| ص | ṣād | /sˤ/ |

| ض | ḍād | /dˤ/ |

| ط | ṭāʾ | /tˤ/ |

| ظ | ẓāʾ | /ðˤ/ |

| ع | ʿayn | /ʕ/ |

| غ | ghayn | /ɣ/ |

| ف | fāʾ | /f/ |

| ق | qāf | /q/ |

| ك | kāf | /k/ |

| ل | lām | /l/ |

| م | mīm | /m/ |

| ن | nūn | /n/ |

| ه | hāʾ | /h/ |

| و | wāw | /w/ or /uː/ |

| ي | yāʾ | /j/ or /iː/ |

Contextual forms and cursive nature

The Arabic script is fundamentally cursive, with letters designed to connect to one another within words, creating a continuous flow even in printed text. This connectivity is a core feature that distinguishes it from many other writing systems, facilitating efficient writing and aesthetic harmony in calligraphy. The script is written and read from right to left, with letters aligning along a horizontal baseline that serves as the primary anchor for glyph placement, ensuring uniform visual structure across words and lines.[32][33] Letters in the Arabic script assume one of four contextual forms depending on their position within a word: isolated (when standing alone or not connecting), initial (at the beginning of a word, connecting only to the following letter), medial (in the middle, connecting to both preceding and following letters), and final (at the end of a word, connecting only to the preceding letter). These forms allow each of the 28 basic letters to adapt its shape dynamically, often resulting in significant visual differences from their isolated counterparts—for instance, the letter beh (ب) appears as ب in isolated form, ﺑ in initial, ﺒ in medial, and ﺐ in final. This positional variation is governed by Unicode standards for rendering, where font systems select the appropriate glyph based on the letter's joining behavior and neighbors.[32][33] The cursive nature is further defined by specific joining rules: 22 letters are dual-joining, capable of connecting to both the preceding (right) and following (left) letters, while 6 letters are right-joining only, connecting solely to the preceding letter and leaving a gap to the left. Examples of right-joining letters include dal (د), which maintains its isolated or final form (د or ﺩ) without linking leftward, and reh (ر), similarly non-connective to the left (ر or ﺭ). Non-joining elements, such as the hamza (ء), do not connect at all. These rules ensure readability by preventing ambiguous merges, particularly for letters with similar shapes.[32][33] In word formation, these principles combine to create fluid sequences; for example, the word كتاب (kitāb, meaning "book") is rendered from right to left with the initial kāf (ك) connecting to the medial tāʾ (ﺘ), which connects to the final alif (ا); the beh (ب) appears isolated to the right of the alif since the right-joining alif terminates the connection without linking leftward. This example illustrates how dual-joining letters like kāf and tāʾ adapt across positions, while the right-joining alif prevents connection to the beh, maintaining the script's baseline alignment and cursive integrity.[32][33]Diacritics, vowels, and orthographic conventions

The Arabic script employs a system of diacritical marks known as harakat (حَرَكَاتْ) to indicate short vowels and other phonetic nuances, which are optional in most modern writing but essential for precise pronunciation. These marks are placed above or below consonants and include the fatha (ـَ), a short diagonal line above the letter representing the vowel sound /a/ as in "father"; the damma (ـُ), a small curl above the letter for /u/ as in "put"; and the kasra (ـِ), a short diagonal line below the letter for /i/ as in "bit". For example, the consonant ب (bāʾ) becomes بَ (ba), بُ (bu), and بِ (bi) respectively.[34][33] Absence of a vowel is denoted by the sukun (ـْ), a small circle placed above the consonant, indicating a consonant closure without a following short vowel, as in بْ (b, pronounced with a brief pause). The shadda (ـّ), resembling a small "w" above the letter, signifies gemination or consonant doubling, where the consonant is held longer and often stressed, effectively combining a sukun on the first instance and a vowel on the second; for instance, بّ (bb) in words like شَدَّة (shadda itself). Tanwin, or nunation, marks indefinite nouns with a doubled short vowel sound at the end, using fathatan (ـً) for /an/, dammatan (ـٌ) for /un/, and kasratan (ـٍ) for /in/, as seen in كِتَابٌ (kitābun, "a book"). These diacritics are encoded in Unicode as combining characters, such as U+064E for fatha and U+0651 for shadda, ensuring consistent digital representation.[34][33] Orthographic conventions in Arabic script govern the placement and form of elements like the hamza (ء), a glottal stop consonant that requires specific seating rules based on its position and surrounding vowels to maintain visual and phonetic clarity. In initial position, hamza is always seated on an alif (ا), forming أ (with fatha or damma) or إ (with kasra), as in أَب (ab, "father"). Medially, it seats on the nearest compatible letter: on a dotless yā (ي) for kasra (ئ), on wāw (و) for damma (ؤ), or on alif otherwise, as in سُؤَال (suʾāl, "question"). At the end of a word, it appears on the line (ء) after a long vowel or sukun, or seated on the appropriate carrier after a short vowel, such as نَشَأَ (nashaʾa, "he arose"). These rules prevent ambiguity and align with the script's cursive flow, though pronunciation of hamza may vary by dialect. Tajweed rules such as assimilation (idgham) and clear pronunciation (izhar) apply to the recitation of tanwin or nun sakinah before certain letters—for example, idgham merges the sound before ي, ر, م, ل, و, ن, while izhar pronounces it clearly before throat letters like ء, ه, ع, ح, غ, خ—but these affect pronunciation only and do not alter the written orthography or diacritic placement.[35][36] In modern usage, diacritics are fully employed in religious texts like the Quran for accurate tajweed recitation and in educational materials for learners, where they aid comprehension and reduce ambiguity in a script that otherwise relies on context for vowels. However, in everyday print media, newspapers, and literature, they are largely omitted to save space and reflect native reader proficiency, appearing sporadically only for disambiguation in poetry or proper names. Digital trends since the 2010s have seen increased optional use in social media and apps for clarity among non-native speakers, though full diacritization remains rare outside formal contexts; scholarly analyses note significant variation across genres, with religious and pedagogical texts showing near-complete marking rates compared to under 5% in general prose.[37]Styles and Variants

Calligraphic and typographic styles

The Arabic script has evolved through a rich tradition of calligraphic styles, each reflecting cultural, religious, and artistic influences across centuries. These styles originated in the early Islamic period and adapted to various media, from manuscripts to architecture, emphasizing the script's inherent cursive and contextual forms. Major styles like Kufic, Naskh, and Nastaliq emerged as foundational, balancing aesthetic elegance with readability, and later influenced typographic developments in printing and digital media. Kufic, one of the earliest formal styles, developed in the late 7th century in Kufa, Iraq, characterized by its angular, geometric letterforms with thick strokes and minimal curves. It flourished from the 7th to 10th centuries, primarily used for Qur'anic manuscripts and architectural inscriptions due to its bold, monumental appearance suitable for stone, metal, and coinage. Examples include early Qur'ans on vellum and decorations on mosques like the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. Naskh emerged in the 10th century as a more fluid, cursive alternative to angular scripts, designed for legibility in everyday and scholarly writing. It became the predominant bookhand by the 11th century, serving as the basis for copying Qur'ans, administrative documents, and literature across the Islamic world, with regional variations in Egypt, Iraq, and Syria. Its rounded, proportional letters facilitated widespread adoption and laid the groundwork for modern printed Arabic. Nastaliq, a highly stylized and flowing script, originated in 14th-century Persia, blending elements of Naskh and Ta'liq for poetic expression. It gained dominance in the 15th century for Persian and Urdu literature, poetry, and official documents, prized for its diagonal slant, elongated horizontals, and rhythmic curves that evoke motion. Prominent in regions like Iran, Pakistan, and India, it remains a staple in South Asian manuscript traditions. The transition to typography began with the introduction of movable type for Arabic script in the early 19th century, notably at Egypt's Bulaq Press established in 1815 under Ottoman rule, where naskh and nasta'liq typefaces were cast for books like dictionaries and Qur'ans. In the Ottoman Empire proper, widespread adoption occurred in the 1860s with innovations by typefounder Ohanis Mühendisoğlu, who adapted calligraphic proportions to metal type for naskh-based printing. This evolution addressed the script's cursive joining and contextual variants, enabling mass production of texts. By the 20th century, refined typefaces like that designed by Mohamed Bek Ja‘far in 1906 for Bulaq Press set standards for clarity in printed Qur'ans. Digital typography advanced in the 2010s with open-source fonts such as Amiri, a 2011 revival by Khaled Hosny of early 20th-century Bulaq naskh, optimized for book typesetting and Qur'anic text in software like LaTeX and web browsers.| Style | Period | Key Characteristics | Primary Regions | Notable Uses and Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kufic | 7th–10th centuries | Angular, geometric, bold strokes | Iraq, Syria, Arabia | Qur'anic manuscripts; architectural inscriptions (e.g., Dome of the Rock) |

| Naskh | 10th century onward | Cursive, rounded, legible proportions | Egypt, Iraq, broader Islamic world | Books, documents; basis for modern print (e.g., medieval Qur'ans) |

| Nastaliq | 14th–15th centuries onward | Flowing, slanted, rhythmic curves | Persia (Iran), South Asia (Pakistan, India) | Poetry, literature (e.g., Persian divans, Urdu manuscripts) |

Regional and language-specific variants

The Arabic script exhibits notable regional variations in letter forms and orthographic conventions, primarily distinguishing between the Western (Maghribi) and Eastern (Mashriqi) traditions. The Maghribi script, prevalent in North Africa including Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia, features rounded letterforms with curved vertical strokes for letters such as alif, lam, and ta, along with exaggerated horizontal extensions and open final curves that descend below the baseline.[38] These characteristics, which evolved from early Kufic influences softened by sweeping curves, facilitate a fluid, cursive appearance adapted to local manuscript traditions and still used in Moroccan Arabic texts today.[39] In contrast, the Eastern or Mashriqi script, dominant in the Middle East such as the Gulf states and Levant, employs sharper angles and more angular proportions in letters like dal and dhal, with less pronounced recurves and a straighter posture that aligns with styles like Naskh. This distinction, attested in medieval Arabic sources, reflects geographical and cultural divergences in scribal practices, where Mashriqi forms prioritize precision in angular connections.[39] Language-specific adaptations further diversify the script, particularly in Southeast Asia. The Jawi script, used for Malay in regions like Malaysia and Brunei, modifies the standard Arabic alphabet by adding diacritics to six letters to accommodate Malay phonemes, such as extra dots for sounds absent in Arabic.[40] This adaptation, introduced by Muslim traders and refined over centuries, incorporates all 31 Arabic letters plus six constructed ones, enabling representation of Malay's vowel and consonant inventory while maintaining right-to-left cursive flow.[41] Similarly, the Pegon script adapts Arabic for Javanese in Indonesia, employing 28 graphemes to denote 23 consonants through minimal modifications, such as added diacritics for Javanese-specific sounds like the ng phoneme, and requiring harakat for vowels to suit the language's syllabic structure.[42] These tweaks, developed in Islamic scholarly contexts, preserve the script's core while aligning with local phonetics, though Pegon usage has waned with the rise of Latin-based orthographies.[43] Historical variants in the Indian subcontinent illustrate further evolution and decline. The Bihari script, a regional Arabic calligraphy style from Bihar and surrounding areas, emerged in the 13th century as a blend of angular and cursive elements, featuring elongated horizontals and distinctive loops in letters like sin and sad.[44] Primarily used for Qur'anic manuscripts, it persisted into the 19th century with over 137 known examples, many dated to the 15th century, but gradually declined following the Mughal promotion of Nastaliq, which standardized more fluid Persian-influenced forms across northern India.[45] This shift marked the end of Bihari's prominence, confining it to a niche in pre-modern Islamic textual production.[46]Usage and Distribution

Current geographical and linguistic use

The Arabic script serves as the official writing system in the 22 member states of the Arab League, spanning North Africa and the Middle East, where it is used for government, education, media, and daily communication.[47] Collectively, these regions are home to approximately 420 million speakers of Arabic dialects, making the script essential for literacy and cultural expression among the world's fifth-most spoken language.[48] Beyond the Arab world, the Arabic script is adapted for several major languages in non-Arab regions, supporting diverse linguistic communities. In Iran and Afghanistan, the Perso-Arabic variant is used for Persian (Farsi) and Dari, with around 80 million speakers, primarily in official documents, literature, and signage.[49] In Pakistan and Afghanistan, the Nastaʿlīq style of the script writes Urdu and Pashto for approximately 230 million and 40 million speakers respectively, serving as the national language in administration, education, and print media.[49][50] In Iraq and Iran, a modified Arabic script is used for Sorani Kurdish, supporting about 6-7 million speakers in official and cultural contexts.[51] In Southeast Asia, the Jawi variant persists in Indonesia and Malaysia, particularly for religious texts, Islamic education, and regional signage in areas like Riau province, where it coexists with Latin script. As of 2025, the Arabic script's digital adoption continues to expand in Central Asia, notably for Uyghur in China's Xinjiang region, where the Uyghur Arabic alphabet remains the official standard for government publications, social media, and signage, reflecting efforts to integrate it into modern technology platforms.[52] This growth underscores the script's resilience in bilingual digital environments despite competing Latin and Cyrillic systems. UNESCO and World Bank data highlight the script's role in literacy across Arabic-script regions, with adult literacy rates in Arab states averaging around 75% as of recent assessments, though variations exist—such as 98% in Bahrain and 79% in Egypt—tied to educational access and script-based instruction.[53] In non-Arab contexts, literacy tied to the script, like in Persian- and Urdu-speaking areas, exceeds 80% in urban centers, supported by widespread schooling in the adapted forms.[54]Adaptations for non-Arabic languages

The Arabic script has been adapted for various non-Arabic languages by incorporating additional characters or diacritics to represent phonemes absent in Classical Arabic, particularly to accommodate Indo-Iranian and Bantu linguistic features.[55][56] In Persian (Farsi), the script adds four letters—چ (che), پ (pe), ژ (zhe), and گ (gaf)—to denote the sounds /tʃ/, /p/, /ʒ/, and /g/, which are not present in the standard Arabic alphabet.[55] These modifications emerged during the Islamicization of Persia in the 7th–9th centuries, enabling the script to fully represent Persian phonology while retaining the cursive, right-to-left structure.[57] Urdu, an Indo-Aryan language, extends the Perso-Arabic script with four additional letters—ٹ (ṭe), ڈ (ḍāl), ڑ (ṛe), and ڻ (ṇūn)—specifically for retroflex consonants /ʈ/, /ɖ/, /ɽ/, and /ɳ/, which are characteristic of its phonology influenced by Prakrit and Sanskrit substrates.[58] These letters, marked by a nukta (dot) diacritic below the base forms, were standardized in the 19th century during the development of modern Urdu literature in British India.[59] Swahili (also known as Kiswahili), a Bantu language, historically employed the Arabic script (known as Ajami) from the 10th century onward, adapting it with extra diacritics and vowel notations to capture its five-vowel system and syllable-timed structure, which differ from Arabic's consonant-heavy phonology.[60] This adaptation facilitated religious and trade-related writing along the East African coast until the 1930s, when colonial authorities mandated a shift to the Latin alphabet for standardization and education.[61] The following table illustrates key phoneme-to-grapheme mappings in these adaptations:| Language | Phoneme | Grapheme | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Persian | /p/ | پ | Modified bāʾ with three dots above for labial stop.[55] |

| Persian | /tʃ/ | چ | Modified jīm with three dots above for affricate.[55] |

| Persian | /ʒ/ | ژ | Modified rāʾ with three dots above for voiced fricative.[55] |

| Persian | /g/ | گ | Modified kāf with two dots above for voiced velar stop. |

| Urdu | /ʈ/ | ٹ | Ṭe: Dental tāʾ with nukta below for retroflex stop.[58] |

| Urdu | /ɖ/ | ڈ | Ḍāl: Dental dāl with nukta below for retroflex stop.[58] |

| Urdu | /ɽ/ | ڑ | Ṛe: Dental re with nukta below for retroflex flap.[59] |

| Urdu | /ɳ/ | ڻ | Ṇūn: Dental nūn with nukta below for retroflex nasal.[58] |

| Swahili (Ajami) | /ɪ/, /ʊ/ | ِ, ُ (with extensions) | Short vowels marked by kasra and damma, often with additional dots or lines for Bantu contrasts.[60] |

Historical and discontinued uses