Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

| Qoph | |

|---|---|

| Phoenician | 𐤒 |

| Hebrew | ק |

| Aramaic | 𐡒 |

| Syriac | ܩ |

| Arabic | ق |

| Geʽez | ቀ |

| Phonemic representation | q, g, ʔ, k |

| Position in alphabet | 19 |

| Numerical value | 100 |

| Alphabetic derivatives of the Phoenician | |

| Greek | Ϙ, Φ |

| Latin | Q |

| Cyrillic | Ҁ, Ф, Ԛ |

Qoph is the nineteenth letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician qōp 𐤒, (ancestor of Q ) Hebrew qūp̄ ק, Aramaic qop 𐡒, Syriac qōp̄ ܩ, and Arabic qāf ق. It is also related to the Ancient North Arabian 𐪄, South Arabian 𐩤, and Ge'ez ቀ.

Its original sound value was a West Semitic emphatic stop, presumably [kʼ]. In Maltese the q is an explosive stop sound e.g. qalb, qattus, baqq. In Hebrew numerals, it has the numerical value of 100.

Origins

[edit]

The origin of the glyph shape of qōp (![]() ) is uncertain. It is usually suggested to have originally depicted either a sewing needle, specifically the eye of a needle (Hebrew קוף quf and Aramaic קופא qopɑʔ both refer to the eye of a needle), or the back of a head and neck (qāf in Arabic meant "nape").[1]

According to an older suggestion, it may also have been a picture of a monkey and its tail (the Hebrew קוף means "monkey").[2]

) is uncertain. It is usually suggested to have originally depicted either a sewing needle, specifically the eye of a needle (Hebrew קוף quf and Aramaic קופא qopɑʔ both refer to the eye of a needle), or the back of a head and neck (qāf in Arabic meant "nape").[1]

According to an older suggestion, it may also have been a picture of a monkey and its tail (the Hebrew קוף means "monkey").[2]

Besides Aramaic Qop, which gave rise to the letter in the Semitic abjads used in classical antiquity, Phoenician qōp is also the origin of the Latin letter Q and Greek Ϙ (qoppa) and Φ (phi).[3]

Arabic qāf

[edit]The Arabic letter ق is named قاف qāf. It is written in several ways depending on its position in the word:

| Qāf قاف | |

|---|---|

| ق | |

| Usage | |

| Writing system | Arabic script |

| Type | Abjad |

| Language of origin | Arabic language |

| Sound values | |

| Alphabetical position | 21 |

| History | |

| Development | 𐤒

|

| Other | |

| Writing direction | Right-to-left |

| Position in word: | Isolated | Final | Medial | Initial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glyph form: (Help) |

ق | ـق | ـقـ | قـ |

Traditionally in the scripts of the Maghreb it is written with a single dot, similarly to how the letter fā ف is written in Mashreqi scripts:[4]

| Position in word: | Isolated | Final | Medial | Initial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glyph form: (Help) |

ڧ | ـڧ | ـڧـ | ڧـ |

It is usually transliterated into Latin script as q, though some scholarly works use ḳ.[5]

Pronunciation

[edit]According to Sibawayh, author of the first book on Arabic grammar, the letter is pronounced voiced (maǧhūr),[6] although some scholars argue, that Sibawayh's term maǧhūr implies lack of aspiration rather than voice.[7] As noted above, Modern Standard Arabic has the voiceless uvular plosive /q/ as its standard pronunciation of the letter, but dialectal pronunciations vary as follows:

The three main pronunciations:

- [q]: in most of Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco, Southern and Western Yemen and parts of Oman, Northern Iraq, parts of the Levant (especially the Alawite and Druze dialects). In fact, it is so characteristic of the Alawites and the Druze that Levantines invented a verb "yqaqi" /jqæqi/ that means "speaking with a /q/".[8] However, most other dialects of Arabic will use this pronunciation in learned words that are borrowed from Standard Arabic into the respective dialect or when Arabs speak Modern Standard Arabic.

- [ɡ]: in most of the Arabian Peninsula, Northern and Eastern Yemen and parts of Oman, Southern Iraq, some parts within Jordan, eastern Syria and southern Palestine, Upper Egypt (Ṣaʿīd), Sudan, Libya, Mauritania and to lesser extent in some parts of Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco but it is also used partially across those countries in some words.[9]

- [ʔ]: in most of the Levant and Egypt, as well as some North African towns such as Tlemcen and Fez.

Other pronunciations:

- [ɢ]: In Sudanese and some forms of Yemeni, even in loanwords from Modern Standard Arabic or when speaking Modern Standard Arabic.

- [k]: In rural Palestinian it is often pronounced as a voiceless velar plosive [k], even in loanwords from Modern Standard Arabic or when speaking Modern Standard Arabic.

Marginal pronunciations:

- [d͡z]: In some positions in Najdi, though this pronunciation is fading in favor of [ɡ].[10][11]

- [d͡ʒ]: Optionally in Iraqi and in Gulf Arabic, it is sometimes pronounced as a voiced postalveolar affricate [d͡ʒ], even in loanwords from Modern Standard Arabic or when speaking Modern Standard Arabic.

- [ɣ] ~ [ʁ]: in Sudanese and some Yemeni dialects (Yafi'i), and sometimes in Gulf Arabic by Persian influence, even in loanwords from Modern Standard Arabic or when speaking Modern Standard Arabic.

Velar gāf

[edit]It is not well known when the pronunciation of qāf ⟨ق⟩ as a velar [ɡ] occurred or the probability of it being connected to the pronunciation of jīm ⟨ج⟩ as an affricate [d͡ʒ], but the Arabian peninsula, there are two sets of pronunciations, either the ⟨ج⟩ represents a [d͡ʒ] and ⟨ق⟩ represents a [ɡ][12] which is the main pronunciation in most of the peninsula except for western and southern Yemen and parts of Oman where ⟨ج⟩ represents a [ɡ] and ⟨ق⟩ represents a [q].

The Standard Arabic (MSA) combination of ⟨ج⟩ as a [d͡ʒ] and ⟨ق⟩ as a [q] does not occur in any natural modern dialect in the Arabian peninsula, which shows a strong correlation between the palatalization of ⟨ج⟩ to [d͡ʒ] and the pronunciation of the ⟨ق⟩ as a [ɡ] as shown in the table below:

| Language varieties | Pronunciation of the letters | |

|---|---|---|

| ج | ق | |

| Proto-Semitic | [ɡ] | [kʼ] |

| Dialects in parts of Oman and Yemen1 | [q] | |

| Modern Standard Arabic2 | [d͡ʒ] | |

| Dialects in most of the Arabian Peninsula | [ɡ] | |

Notes:

- Western and southern Yemen: Taʽizzi, Adeni and Tihamiyya dialects (coastal Yemen), in addition to southwestern (Salalah region) and eastern Oman, including Muscat, the capital.

- As used in the Arabian Peninsula: in Sanaa; ق is [ɡ] in Sanʽani dialect and also in the literary standard (local MSA), whereas the literary standard pronunciation in Sudan is [ɢ] or [ɡ]. For the pronunciation of ج in Modern Standard Arabic, check Jīm.

Pronunciation across other languages

[edit]| Language | Dialect(s) / Script(s) | Pronunciation (IPA) |

|---|---|---|

| Azeri | Arabic alphabet | /g/ |

| Kurdish | Sorani | /q/ |

| Malay | Jawi | /q/ or /k/ |

| Pashto | /q/ or /k/ | |

| Persian | Dari | /q/ |

| Iranian | /ɢ/~/ɣ/ or /q/ | |

| Punjabi | Shahmukhi | /q/ or /k/ |

| Urdu | /q/ or /k/ | |

| Uyghur | /q/ | |

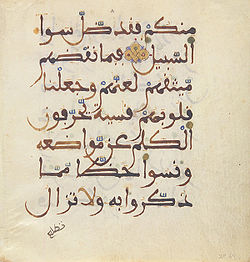

Maghrebi variant

[edit]The Maghrebi style of writing qāf is different: having only a single point (dot) above; when the letter is isolated or word-final, it may sometimes become unpointed.[13]

| Position in word: | Isolated | Final | Medial | Initial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Form of letter: | ڧ ࢼ |

ـڧ ـࢼ |

ـڧـ | ڧـ |

The earliest Arabic manuscripts show qāf in several variants: pointed (above or below) or unpointed.[14] Then the prevalent convention was having a point above for qāf and a point below for fāʼ; this practice is now only preserved in manuscripts from the Maghribi,[15] with the exception of Libya and Algeria, where the Mashriqi form (two dots above: ق) prevails.

Within Maghribi texts, there is no possibility of confusing it with the letter fāʼ, as it is instead written with a dot underneath (ڢ) in the Maghribi script.[16]

Hebrew qof

[edit]The Oxford Hebrew-English Dictionary transliterates the letter Qoph (קוֹף) as q or k; and, when word-final, it may be transliterated as ck.[citation needed] The English spellings of Biblical names (as derived via Latin from Biblical Greek) containing this letter may represent it as c or k, e.g. Cain for Hebrew Qayin, or Kenan for Qenan (Genesis 4:1, 5:9).

| Orthographic variants | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Various print fonts | Cursive Hebrew |

Rashi script | ||

| Serif | Sans-serif | Monospaced | ||

| ק | ק | ק | ||

Pronunciation

[edit]In modern Israeli Hebrew the letter is also called kuf. The letter represents /k/; i.e., no distinction is made between the pronunciations of Qof and Kaph with Dagesh (in modern Hebrew).

However, many historical groups have made that distinction, with Qof being pronounced [q] by Iraqi Jews and other Mizrahim, or even as [ɡ] by Yemenite Jews influenced by Yemeni Arabic.

Qoph is consistently transliterated into classical Greek with the unaspirated〈κ〉/k/, while Kaph (both its allophones) is transliterated with the aspirated〈χ〉/kʰ/. Thus Qoph was unaspirated /k/ where Kaph was /kʰ/, this distinction is no longer present. Further we know that Qoph is one of the emphatic consonants through comparison with other Semitic languages, and most likely was ejective /kʼ/. In Arabic the emphatics are pharyngealised and this causes a preference for back vowels, this is not shown in Hebrew orthography. Though the gutturals show a preference for certain vowels, Hebrew emphatics do not in Tiberian Hebrew (the Hebrew dialect recorded with vowels) and therefore were most likely not pharyngealised, but ejective, pharyngealisation being a result of Arabisation.[citation needed]

Numeral

[edit]Qof in Hebrew numerals represents the number 100. Sarah is described in Genesis Rabba as בת ק' כבת כ' שנה לחטא, literally "At Qof years of age, she was like Kaph years of age in sin", meaning that when she was 100 years old, she was as sinless as when she was 20.[17]

Syriac qop

[edit]| Position in word: | Isolated | Final | Medial | Initial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glyph form: (Help) |

ܩ | ـܩ | ـܩـ | ܩـ |

Unicode

[edit]| Preview | ק | ق | ڧ | ࢼ | ܩ | ࠒ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unicode name | HEBREW LETTER QOF | ARABIC LETTER QAF | ARABIC LETTER QAF WITH DOT ABOVE | ARABIC LETTER AFRICAN QAF | SYRIAC LETTER QAPH | SAMARITAN LETTER QUF | ||||||

| Encodings | decimal | hex | dec | hex | dec | hex | dec | hex | dec | hex | dec | hex |

| Unicode | 1511 | U+05E7 | 1602 | U+0642 | 1703 | U+06A7 | 2236 | U+08BC | 1833 | U+0729 | 2066 | U+0812 |

| UTF-8 | 215 167 | D7 A7 | 217 130 | D9 82 | 218 167 | DA A7 | 224 162 188 | E0 A2 BC | 220 169 | DC A9 | 224 160 146 | E0 A0 92 |

| Numeric character reference | ק |

ק |

ق |

ق |

ڧ |

ڧ |

ࢼ |

ࢼ |

ܩ |

ܩ |

ࠒ |

ࠒ |

| Preview | 𐎖 | 𐡒 | 𐤒 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unicode name | UGARITIC LETTER QOPA | IMPERIAL ARAMAIC LETTER QOPH | PHOENICIAN LETTER QOF | |||

| Encodings | decimal | hex | dec | hex | dec | hex |

| Unicode | 66454 | U+10396 | 67666 | U+10852 | 67858 | U+10912 |

| UTF-8 | 240 144 142 150 | F0 90 8E 96 | 240 144 161 146 | F0 90 A1 92 | 240 144 164 146 | F0 90 A4 92 |

| UTF-16 | 55296 57238 | D800 DF96 | 55298 56402 | D802 DC52 | 55298 56594 | D802 DD12 |

| Numeric character reference | 𐎖 |

𐎖 |

𐡒 |

𐡒 |

𐤒 |

𐤒 |

References

[edit]- ^ Travers Wood, Henry Craven Ord Lanchester, A Hebrew Grammar, 1913, p. 7. A. B. Davidson, Hebrew Primer and Grammar, 2000, p. 4. The meaning is doubtful. "Eye of a needle" has been suggested, and also "knot" Harvard Studies in Classical Philology vol. 45.

- ^ Isaac Taylor, History of the Alphabet: Semitic Alphabets, Part 1, 2003, p. 174: "The old explanation, which has again been revived by Halévy, is that it denotes an 'ape,' the character Q being taken to represent an ape with its tail hanging down. It may also be referred to a Talmudic root which would signify an 'aperture' of some kind, as the 'eye of a needle,' ... Lenormant adopts the more usual explanation that the word means a 'knot'.

- ^ Qop may have been assigned the sound value /kʷʰ/ in early Greek; as this was allophonic with /pʰ/ in certain contexts and certain dialects, the letter qoppa continued as the letter phi. C. Brixhe, "History of the Alpbabet", in Christidēs, Arapopoulou, & Chritē, eds., 2007, A History of Ancient Greek.

- ^ al-Banduri, Muhammad (2018-11-16). "الخطاط المغربي عبد العزيز مجيب بين التقييد الخطي والترنح الحروفي" [Moroccan calligrapher Abd al-Aziz Mujib: between calligraphic restriction and alphabetic staggering]. Al-Quds (in Arabic). Retrieved 2019-12-17.

- ^ e.g., The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition

- ^ Kees Versteegh, The Arabic Language, pg. 131. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2001. Paperback edition. ISBN 9780748614363

- ^ Al-Jallad, Ahmad (2020). A Manual of the Historical Grammar of Arabic (Draft). p. 47.

- ^ Samy Swayd (10 March 2015). Historical Dictionary of the Druzes (2 ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-4422-4617-1.

- ^ This variance has led to the confusion over the spelling of Libyan leader Muammar al-Gaddafi's name in Latin letters. In Western Arabic dialects the sound [q] is more preserved but can also be sometimes pronounced [ɡ] or as a simple [k] under Berber and French influence.

- ^ Bruce Ingham (1 January 1994). Najdi Arabic: Central Arabian. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 14. ISBN 90-272-3801-4.

- ^ Lewis, Robert Jr. (2013). Complementizer Agreement in Najdi Arabic (PDF) (MA thesis). University of Kansas. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 19, 2018.

- ^ al Nassir, Abdulmunʿim Abdulamir (1985). Sibawayh the Phonologist (PDF) (in Arabic). University of New York. p. 80. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ van den Boogert, N. (1989). "Some notes on Maghrebi script" (PDF). Manuscript of the Middle East. 4. p. 38 shows qāf with a superscript point in all four positions.

- ^ Gacek, Adam (2008). The Arabic Manuscript Tradition. Brill. p. 61. ISBN 978-90-04-16540-3.

- ^ Gacek, Adam (2009). Arabic Manuscripts: A Vademecum for Readers. Brill. p. 145. ISBN 978-90-04-17036-0.

- ^ Muhammad Ghoniem, M S M Saifullah, cAbd ar-Rahmân Robert Squires & cAbdus Samad, Are There Scribal Errors In The Qur'ân?, see qif on a traffic sign written ڧڢ which is written elsewhere as قف, Retrieved 2011-August-27

- ^ Rabbi Ari Kahn (20 October 2013). "A deeper look at the life of Sarah". aish.com. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

External links

[edit]Origins and History

Proto-Semitic and Early Attestations

In Proto-Semitic, the phoneme *q was reconstructed as an emphatic voiceless uvular stop [qˤ], articulated with pharyngealization or ejectives, and distinctly contrasted with the plain voiceless velar stop *k.[5][6] This distinction maintained a robust dorsal stop series in the language's consonant inventory, influencing subsequent Semitic scripts where *q required a dedicated grapheme.[7] The grapheme for *q, later known as qoph, originated in the Proto-Sinaitic script through the acrophonic principle, adapting Egyptian hieroglyphs to represent Semitic sounds based on the initial consonant of the depicted object's name.[8] It derived from a pictographic symbol possibly evoking a monkey (from the Semitic root *qop- meaning "monkey") or the back of the head, with interpretations in later traditions linking it to the "eye of a needle" due to its looped form.[8][9] By around 1900–1700 BCE, this evolved into more abstract linear representations within the script's 22 consonantal signs.[8] The earliest attestations of the qoph grapheme appear in Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions from Serabit el-Khadim in the Sinai Peninsula, dated to circa 1850–1800 BCE and associated with Middle Kingdom Egyptian mining expeditions under pharaohs like Senwosret III and Amenemhat III.[10] These inscriptions, carved on rock faces, plaques, and statuettes, feature the letter in a characteristic circular form with a descending vertical line, reflecting its pictographic heritage while adapting to linear writing.[8] Examples include brief dedications or labels by Semitic workers, marking the script's role in early alphabetic experimentation.[10] From these origins, the qoph symbol transitioned through the intermediate Proto-Canaanite phase into the Paleo-Hebrew script by the 10th century BCE, as evidenced by inscriptions from sites like Jerusalem that show stabilized forms amid regional adaptations.[11] This evolution paralleled the script's spread across early Semitic-speaking communities in the Levant, solidifying qoph as a consistent marker for the emphatic uvular phoneme.[11]Phoenician Qoph

The Phoenician qoph served as the nineteenth letter in the 22-letter abjad, representing the voiceless uvular stop /q/, a guttural rasping sound produced deep in the throat that is characteristic of Semitic phonology.[12] This phonetic value distinguished it from other velar or pharyngeal consonants in the script, enabling precise representation of sounds essential to Phoenician speech.[13] Graphically, qoph typically appeared as a circle or loop from which a vertical stroke descended, often attached at the base, a form that evolved slightly across inscriptions but maintained its core structure. This design was inscribed on stone, metal, and other surfaces from roughly 1050 BCE to 150 BCE, reflecting the script's widespread application in Phoenician society. The letter's form showed minor positional variations—such as subtle adjustments in stroke length or loop closure—depending on whether it appeared in initial, medial, or final positions within words, adapting to the linear flow of right-to-left writing.[14] Qoph featured prominently in core Phoenician texts and extended to derivative scripts like Punic, where it retained its /q/ value while accommodating regional dialects in colonial contexts.[15] A notable early example appears in the Ahiram sarcophagus inscription from Byblos, dated to the 10th century BCE, where qoph occurs in the curse formula (e.g., in words like pqdr, "he will disturb"), demonstrating its use in formal royal dedications and protective incantations.[14] Such attestations highlight qoph's integration into monumental epigraphy, underscoring the alphabet's maturity by this period. Through Phoenician maritime trade networks, qoph and the broader alphabet facilitated record-keeping, contracts, and cultural exchange across the Mediterranean, notably in colonies like Carthage, where the script supported economic administration and persisted in Punic variants long after the mainland's decline.[15] This dissemination via commerce helped standardize communication in diverse settings, from ship manifests to treaties, amplifying Phoenicia's influence on subsequent writing systems.[12]Evolution to Greek Koppa and Latin Q

The Phoenician letter qoph was adopted into the Archaic Greek alphabet as koppa (Ϙ, ϙ) around the late 9th or early 8th century BCE, where it came to represent the /k/ sound, particularly before rounded vowels like /o/ and /u/, distinguishing it from kappa (Κ) in some early dialects.[16] In early Greek dialects, koppa served to denote this back velar sound, particularly before rounded vowels like /o/ and /u/, distinguishing it from kappa's broader application.[17] This adoption occurred as part of the broader adaptation of the Phoenician script by Greek speakers in regions like Euboea and Crete, where the full set of 22 Phoenician letters was initially incorporated before refinements.[16] Graphically, koppa evolved from the Phoenician qoph's looped form into variations such as a vertical line intersecting a circle or a circle with a horizontal crossbar, reflecting regional inscriptional styles in early Greek artifacts from sites like Corinth and Crete.[17] By the classical period, following phonetic shifts in Greek that eliminated the /q/ phoneme, koppa fell into disuse for writing words and was retained primarily for its numerical value of 90 in the Ionic numeral system, appearing in texts from areas like Miletus.[17] The letter transmitted to the Etruscan script via the Euboean Greek alphabet in the late 8th century BCE, where it retained a form resembling koppa and a phonetic value akin to /k/ before /u/, before passing to early Latin around the 7th century BCE.[18] In Latin, Q adopted an initial graphical shape mirroring the Greek koppa—a circle with a short vertical stroke—but developed a distinctive downward tail by the 4th century BCE, as seen in inscriptions like the Duenos inscription (c. 600–550 BCE) featuring "QOI" for /kʷi/.[18] Phonetically, Latin Q represented the labiovelar /kʷ/, typically in combination with V (as QV) before back vowels, distinguishing it from C and K used elsewhere; this usage appears in early artifacts such as the Forum inscription (c. 700–500 BCE) with "QVOI" meaning "who."[19] While koppa vanished from Greek literary use after the 4th century BCE due to sound mergers, Q persisted in Latin for denoting /kʷ/ in native words like quaestor and later loanwords, such as those entering English as "queen" from Proto-Germanic kwēnō.[18]Hebrew Qof

Form and Pronunciation

In the modern Hebrew alphabet, the letter qof (ק) features a distinctive curved, hook-like shape formed by a vertical or slightly inclined stem topped by a small horizontal or angled stroke, with the lower part descending below the baseline to create an elongated tail.[20] This form appears consistently without positional variants, as Hebrew script does not employ joining or contextual modifications like cursive Arabic; qof remains isolated in both print and handwriting.[21] Variants include the standard block (square) script used in most printed texts, a flowing cursive style for everyday handwriting, and the semi-cursive Rashi script employed in rabbinic commentaries, where the hook is often more rounded but retains the descending element.[21][22] In contemporary Israeli Hebrew, qof is pronounced as a voiceless velar plosive /k/, identical to the sound of kaf (כ) without distinction.[21][22] However, traditional pronunciations differ: in the Tiberian Masoretic tradition (8th–10th centuries CE), foundational to liturgical reading, qof was realized as a voiceless uvular plosive , articulated with the back of the tongue against the uvula, as documented in medieval orthoepic treatises and preserved in manuscripts like the Aleppo Codex.[23] This uvular quality persists in Sephardic and Yemenite traditions, where qof maintains /q/, contrasting with the velar /k/ of Ashkenazic usage.[23][24] Historically, qof's phonetic value shifted from an emphatic uvular or velar stop /qˤ/ in Biblical Hebrew—reflecting pharyngealization common to Semitic emphatics—to the non-emphatic uvular in the post-Exilic Tiberian system, as evidenced by consistent vocalizations in Masoretic texts such as the Codex Leningradensis, where words like קוֹל (qôl, "voice") are pointed to indicate the uvular articulation.[24][23] Qof appears in key biblical words such as qol ("voice") and qadosh ("holy"). By the revival of Hebrew in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, sociolinguistic simplification merged it with /k/ in everyday Israeli speech, though traditional readings in synagogues retain the uvular form among communities adhering to Sephardic or Yemenite rites; as of 2025, some Israeli speakers maintain subtle distinctions in formal or religious contexts.[23] In gematria, qof holds the numerical value of 100.[21]Numerical and Symbolic Uses

In Hebrew gematria, the letter qof (ק) is assigned the numerical value of 100, serving as a foundational element in the system where letters double as numerals for calculations, dates, and symbolic interpretations.[1] This value positions qof among the higher letters (from qof to tav, valued 100 to 400), enabling its use in representing larger quantities without additional symbols.[21] For cardinal and ordinal notations, qof commonly appears with a geresh (׳) as ק׳ to denote 100, as seen in compound numbers like קט"ו for 115.[25] Qof plays a key role in abbreviations for the Hebrew calendar, particularly in year designations where gematria condenses dates. For instance, the year 150 CE is abbreviated as ק"ן, combining qof with nun for precise historical or chronological references.[25] Unlike letters such as kaf, mem, nun, pe, and tsadi, which adopt distinct final forms (sofit) at word ends, qof maintains its standard shape regardless of position, simplifying its application in numerical contexts.[26] Symbolically, qof holds profound significance in Kabbalistic thought, often embodying the tension between holiness (kedushah) and unholiness (kelipah). Its form evokes the back of the head—derived from the root q-w-p, meaning to bend or encircle—symbolizing hidden potentials, divine encirclement, and the emergence of wisdom from concealed realms.[1] In the Sefer Yetzirah, a foundational Kabbalistic text, qof is one of the twelve "simple" letters associated with cosmic structure: it corresponds to the zodiac sign Pisces, the month of Adar, the organ of the spleen, and the sense of laughter, illustrating its role in balancing physical and spiritual dimensions.[27] These associations underscore qof's mystical link to divine wisdom and the transcendence of mundane boundaries.[28]Arabic Qāf

Standard Form and Pronunciation

The standard form of the Arabic letter qāf is ق, characterized by a curved stem with two dots positioned above it, distinguishing it from similar letters like fāʾ (ف). In the cursive Arabic script, qāf exhibits contextual variation across four primary positions: isolated (ﻕ), initial (ﻗ), medial (ـﻘـ), and final (ﻖ). These forms are defined in the Unicode standard for Arabic presentation, where the isolated form is encoded as U+FED5, final as U+FED6, initial as U+FED7, and medial as U+FED8. In calligraphic styles such as Naskh, qāf commonly forms ligatures with adjacent letters, particularly when medial, to ensure smooth connectivity in words.[29][30] Qāf represents the 21st letter in the Arabic abjad. Its pronunciation is a voiceless uvular stop , articulated by elevating the back of the tongue to contact the uvula before releasing a burst of air, creating a deep, guttural sound distinct from the velar stop of kāf (ك). This phoneme has no direct equivalent in English but approximates a emphatic "k" produced farther back in the throat. In Quranic recitation under Tajwid rules, qāf's makhraj (point of articulation) is the uppermost part of the throat near the uvula, and it is classified as a heavy (mufakhkham) letter requiring elevation (istilāʾ) of the tongue, often with an echoing quality (qalqalah) when vowelless. For example, in the word qurʾān (قُرْآن), qāf initiates with a forceful uvular closure followed by a subtle vibration if sukkūn applies.[31][32] Historically, qāf retains the Proto-Arabic phoneme /q/, a voiceless uvular plosive inherited from Proto-Semitic *q, without significant alteration in Classical Arabic, where it maintains its emphatic depth and uvular articulation as a core consonant of the language's phonology. This stability contrasts with shifts in other Semitic branches, preserving its role in root-derived vocabulary.[33]Regional Variants and Adaptations

In adaptations of the Arabic letter qāf (ق) for non-Arabic languages, significant graphical and phonetic modifications occur to accommodate local phonologies. In Persian, the letter evolves into gāf (گ, U+06AF), representing the voiced velar plosive /ɡ/, formed by adding a horizontal stroke above the kāf (ک); this form is also adopted in Urdu for the same sound.[34] In Sindhi, a further variant appears as gāf with three dots above (ڳ, U+06B3), distinguishing /ɡ/ while maintaining the base shape derived from qāf.[35] In North African Maghrebi scripts, such as those used in Algerian and Tunisian Arabic, qāf often appears in a dotless form (ق without the two upper dots), particularly in isolated and final positions, while retaining the dots in initial and medial forms; this variant is pronounced as /ɡ/ or /q/ depending on the regional dialect.[36] Modern printed Qurans in the Maghrebi tradition sometimes use a single-dotted qāf (ڧ, U+06A7) to reflect these conventions.[37] Other adaptations include the Ottoman Turkish usage of qāf (ق), which was pronounced as /k/ before front vowels due to vowel harmony influences in the language's phonology. Historical shifts in Turkic languages following the 1928 script reform in Turkey, which replaced the Perso-Arabic script with a Latin-based alphabet, led to the discontinuation of qāf; uvular and velar sounds previously represented by it were merged into /k/ or /g/ in the new orthography, influencing subsequent adaptations in other Turkic scripts.[38]Usage in Dialects and Languages

In Arabic dialects, the pronunciation of qāf varies significantly, reflecting regional phonetic shifts from the standard uvular /q/. In Levantine dialects, including Syrian and Palestinian varieties, qāf is commonly realized as a glottal stop /ʔ/, as in the word qalb (heart), pronounced /ʔalb/.<grok:render type="render_inline_citation">Syriac Qop

Script Forms

The Syriac letter qop (ܩ), the nineteenth letter in the 22-letter abjad, traces its historical development to the 1st century CE, evolving from the Aramaic script of the Achaemenid Persian period (539–330 BCE), which itself derived from the Phoenician alphabet through Aramean adaptations in regions like Syria.[39] The earliest known Syriac inscriptions, including those featuring qop, date to around 6 CE near Birecik, marking the script's emergence as a distinct system for writing Eastern Aramaic dialects.[39] In the Eastern variant, known as Madnhaya or Swadaya, qop appears as ܩ, characterized by an angular structure with a prominent loop at the base, reflecting the script's block-like, angular aesthetic developed by the 13th century in East Syriac traditions.[40] By contrast, the Western Serṭā form exhibits more fluid curves, with a rounded head transitioning into a descending tail, while the classical Estrangela variant presents even fuller curves and a rounded body, emphasizing elegance in early manuscripts.[40][41] Syriac scripts lack the extensive cursive joining of Arabic, but qop connects to adjacent letters in Estrangela and Serṭā styles, yielding positional variants such as isolated (ܩ), right-joining (ܩـ), left-joining (ـܩ), and dual-joining (ـܩـ) forms to facilitate word flow.[41] These connections are evident in Estrangela manuscripts of the Peshitta Bible, where qop integrates seamlessly into connected text while retaining its looped or curved baseline.[42] In Garshuni, an adaptation of the Syriac script for writing Arabic and other languages, qop serves to represent the uvular /q/ sound corresponding to Arabic qāf, appearing in the same forms as in standard Syriac but applied to non-Syriac phonology in texts from the Islamic era onward.[43][44]Pronunciation and Phonetic Value

In Classical Syriac, the letter qop (ܩ) represents the voiceless uvular plosive /q/, a consonant articulated with the back of the tongue against the soft palate, often described as an emphatic sound due to its pharyngeal quality in Semitic phonology. This phonetic value is preserved in religious texts and liturgical readings, where qop serves as a distinct phoneme contrasting with kaph (/k/), ensuring accurate differentiation in words such as qūšāyā ("hardness," from the root q-š-y denoting rigidity) versus forms with kaph like kūšāyā (hypothetical variant for "bow," from k-š-y). The sound is illustrated in biblical terms like ʾīsaḥāq ("Isaac," pronounced /ʔisˈħɑq/), where the initial qop maintains its uvular stop quality.[45] In modern Neo-Aramaic dialects derived from Syriac, the pronunciation of qop exhibits variations influenced by regional and communal traditions. In Assyrian Neo-Aramaic (Sureth), qop is typically realized as /q/, a uvular plosive similar to Classical Syriac, though some dialects may show softening in casual speech while preserving the full /q/ in formal contexts. Chaldean Neo-Aramaic retains /q/ in conservative pronunciations, with regional variations reflecting influences from Arabic. Liturgically, East Syriac traditions (e.g., Assyrian Church of the East) emphasize the emphatic /q/ in readings from lectionaries, distinguishing it from kaph to uphold phonemic contrasts in sacred texts like the Peshitta, whereas West Syriac traditions (e.g., Syriac Orthodox) maintain a similar /q/ but with slight palatalization in connected speech.[46][45] In Turoyo, a Central Neo-Aramaic dialect spoken in Tur Abdin, qop is generally pronounced as /q/, as in qməstɒ ("shirt"). This preservation of qop's role in religious texts, such as Syriac Orthodox lectionaries, underscores its importance for maintaining historical phonology amid dialectal evolution.[45]Digital Representation

Unicode and Encoding

In the Unicode Standard, the Hebrew letter qof is encoded as U+05E7 ק (HEBREW LETTER QOF) within the Hebrew block (U+0590–U+05FF), which resides in the Basic Multilingual Plane (BMP). This code point supports the letter's use in pointed Hebrew text, where it combines with niqqud diacritics (such as those in U+0591–U+05C7) to indicate vowels and other phonetic features, enabling full vocalization in digital representations of biblical and modern Hebrew. The Arabic letter qāf is represented by U+0642 ق (ARABIC LETTER QAF) in the Arabic block (U+0600–U+06FF). Due to the cursive nature of the Arabic script, contextual shaping is handled through presentation forms in the Arabic Presentation Forms-B block (U+FE70–U+FEFF), including isolated (U+FED5), final (U+FED6), initial (U+FED7), and medial (U+FED8) variants of qāf, which allow for proper joining behavior in connected text rendering.[29] For the Syriac script, the letter qop (or qaph) is encoded as U+0729 ܩ (SYRIAC LETTER QAPH) in the Syriac block (U+0700–U+074F).[47] In Garshuni adaptations—where Syriac script is used to write Arabic—the standard qaph code point is typically employed, often with additional diacritics from the Syriac block (e.g., U+0730–U+074A for vowels and punctuation) to distinguish phonetic values, though no dedicated punctuated variant for qaph exists separately.[47] Related historical and derivative forms include the Greek letter koppa, encoded as U+03DE Ϟ (GREEK LETTER KOPPA, uppercase) and U+03DF ϟ (GREEK SMALL LETTER KOPPA, lowercase) in the Greek and Coptic block (U+0370–U+03FF). Additionally, the modern Latin letter Q derives from qoph influences and is encoded as U+0051 Q in the Basic Latin block (U+0000–U+007F).| Script | Letter Name | Code Point | Character | Block |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hebrew | Qof | U+05E7 | ק | Hebrew (U+0590–U+05FF) |

| Arabic | Qāf | U+0642 | ق | Arabic (U+0600–U+06FF) |

| Syriac | Qaph | U+0729 | ܩ | Syriac (U+0700–U+074F) |

| Greek | Koppa (upper) | U+03DE | Ϟ | Greek (U+0370–U+03FF) |

| Greek | Koppa (lower) | U+03DF | ϟ | Greek (U+0370–U+03FF) |

| Latin | Q | U+0051 | Q | Basic Latin (U+0000–U+007F) |