Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

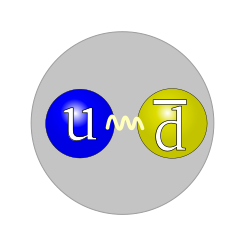

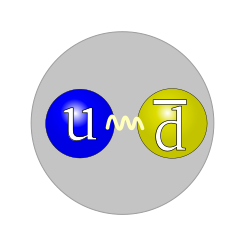

The quark structure of the positively charged pion. | |

| Composition |

|

|---|---|

| Statistics | Bosonic |

| Family | Mesons |

| Interactions | Strong, weak, electromagnetic, and gravity |

| Symbol | π+ , π0 , and π− |

| Antiparticle |

|

| Theorized | Hideki Yukawa (1935) |

| Discovered |

|

| Types | 3 |

| Mass | |

| Mean lifetime |

|

| Electric charge |

|

| Charge radius | π± : ±0.659(4) fm[1] |

| Color charge | 0 |

| Spin | 0 ħ |

| Isospin |

|

| Hypercharge | 0 |

| Parity | −1 |

| C parity | +1 |

In particle physics, a pion (/ˈpaɪ.ɒn/, PIE-on) or pi meson, denoted with the Greek letter pi (π), is any of three subatomic particles: π0

, π+

, and π−

. Each pion consists of a quark and an antiquark and is therefore a meson. Pions are the lightest mesons and, more generally, the lightest hadrons. They are unstable, with the charged pions π+

and π−

decaying after a mean lifetime of 26.033 nanoseconds (2.6033×10−8 seconds), and the neutral pion π0

decaying after a much shorter lifetime of 85 attoseconds (8.5×10−17 seconds).[1] Charged pions most often decay into muons and muon neutrinos, while neutral pions generally decay into gamma rays.

The exchange of virtual pions, along with vector, rho and omega mesons, provides an explanation for the residual strong force between nucleons. Pions are not produced in radioactive decay, but commonly are in high-energy collisions between hadrons. Pions also result from some matter–antimatter annihilation events. All types of pions are also produced in natural processes when high-energy cosmic-ray protons and other hadronic cosmic-ray components interact with matter in Earth's atmosphere. In 2013, the detection of characteristic gamma rays originating from the decay of neutral pions in two supernova remnants has shown that pions are produced copiously after supernovas, most probably in conjunction with production of high-energy protons that are detected on Earth as cosmic rays.[2]

The pion also plays a crucial role in cosmology, by imposing an upper limit on the energies of cosmic rays surviving collisions with the cosmic microwave background, through the Greisen–Zatsepin–Kuzmin limit.[3]

History

[edit]

The π0

meson contains an anti-quark, shown as travelling in the opposite direction, as per the Feynman–Stueckelberg interpretation.

Theoretical work by Hideki Yukawa in 1935 had predicted the existence of mesons as the carrier particles of the strong nuclear force. From the range of the strong nuclear force (inferred from the radius of the atomic nucleus), Yukawa predicted the existence of a particle having a mass of about 100 MeV/c2. Initially after its discovery in 1936, the muon (initially called the "mu meson") was thought to be this particle, since it has a mass of 106 MeV/c2. However, later experiments showed that the muon did not participate in the strong nuclear interaction. In modern terminology, this makes the muon a lepton, and not a meson. However, some communities of astrophysicists continue to call the muon a "mu-meson".[according to whom?] The pions, which turned out to be examples of Yukawa's proposed mesons, were discovered later: the charged pions in 1947, and the neutral pion in 1950.

In 1947, the first true mesons, the charged pions, were found by the collaboration led by Cecil Powell at the University of Bristol, in England. The discovery article had four authors: César Lattes, Giuseppe Occhialini, Hugh Muirhead and Powell.[4] Since the advent of particle accelerators had not yet come, high-energy subatomic particles were only obtainable from atmospheric cosmic rays. Photographic emulsions based on the gelatin-silver process were placed for long periods of time in sites located at high-altitude mountains, first at Pic du Midi de Bigorre in the Pyrenees, and later at Chacaltaya in the Andes Mountains, where the plates were struck by cosmic rays. After development, the photographic plates were inspected under a microscope by a team of about a dozen women.[5] Marietta Kurz was the first person to detect the unusual "double meson" tracks, characteristic for a pion decaying into a muon, but they were too close to the edge of the photographic emulsion and deemed incomplete. A few days later, Irene Roberts observed the tracks left by pion decay that appeared in the discovery paper. Both women are credited in the figure captions in the article.

In 1948, Lattes, Eugene Gardner, and their team first artificially produced pions at the University of California's cyclotron in Berkeley, California, by bombarding carbon atoms with high-speed alpha particles. Further advanced theoretical work was carried out by Riazuddin, who in 1959 used the dispersion relation for Compton scattering of virtual photons on pions to analyze their charge radius.[6]

Since the neutral pion is not electrically charged, it is more difficult to detect and observe than the charged pions are. Neutral pions do not leave tracks in photographic emulsions or Wilson cloud chambers. The existence of the neutral pion was inferred from observing its decay products from cosmic rays, a so-called "soft component" of slow electrons with photons. The π0

was identified definitively at the University of California's cyclotron in 1949 by observing its decay into two photons.[7] Later in the same year, they were also observed in cosmic-ray balloon experiments at Bristol University.

... Yukawa choose the letter π because of its resemblance to the Kanji character for 介 [kai], which means "to mediate", based on the idea that the meson works as a strong force mediator particle between hadrons.[8]

Possible applications

[edit]The use of pions in medical radiation therapy, such as for cancer, was explored at a number of research institutions, including the Los Alamos National Laboratory's Meson Physics Facility, which treated 228 patients between 1974 and 1981 in New Mexico,[9] and the TRIUMF laboratory in Vancouver, British Columbia.

Theoretical overview

[edit]In the standard understanding of the strong force interaction as defined by quantum chromodynamics, pions are loosely portrayed as Goldstone bosons of spontaneously broken chiral symmetry. That explains why the masses of the three kinds of pions are considerably less than that of the other mesons, such as the scalar or vector mesons. If their current quarks were massless particles, it could make the chiral symmetry exact and thus the Goldstone theorem would dictate that all pions have a zero mass.

In fact, it was shown by Gell-Mann, Oakes and Renner (GMOR)[10] that the square of the pion mass is proportional to the sum of the quark masses times the quark condensate: with B the quark condensate: This is often known as the GMOR relation and it explicitly shows that in the massless quark limit. The same result also follows from light-front holography.[11]

Empirically, since the light quarks actually have minuscule nonzero masses, the pions also have nonzero rest masses. However, those masses are almost an order of magnitude smaller than that of the nucleons, roughly[10] 45 MeV, where mq are the relevant current quark masses, around 5–10 MeV/c2.

The pion is one of the particles that mediate the residual strong interaction between a pair of nucleons. This interaction is attractive: it pulls the nucleons together. Written in a non-relativistic form, it is called the Yukawa potential. The pion, being spinless, has kinematics described by the Klein–Gordon equation. In the terms of quantum field theory, the effective field theory Lagrangian describing the pion-nucleon interaction is called the Yukawa interaction.

The nearly identical masses of π±

and π0

indicate that there must be a symmetry at play: this symmetry is called the SU(2) flavour symmetry or isospin. The reason that there are three pions, π+

, π−

and π0

, is that these are understood to belong to the triplet representation or the adjoint representation 3 of SU(2). By contrast, the up and down quarks transform according to the fundamental representation 2 of SU(2), whereas the anti-quarks transform according to the conjugate representation 2*.

With the addition of the strange quark, the pions participate in a larger, SU(3), flavour symmetry, in the adjoint representation, 8, of SU(3). The other members of this octet are the four kaons and the eta meson.

Pions are pseudoscalars under a parity transformation. Pion currents thus couple to the axial vector current and so participate in the chiral anomaly.

Basic properties

[edit]Pions, which are mesons with zero spin, are composed of first-generation quarks. In the quark model, an up quark and an anti-down quark make up a π+

, whereas a down quark and an anti-up quark make up the π−

, and these are the antiparticles of one another. The neutral pion π0

is a combination of an up quark with an anti-up quark, or a down quark with an anti-down quark. The two combinations have identical quantum numbers, and hence they are only found in superpositions. The lowest-energy superposition of these is the π0

, which is its own antiparticle. Together, the pions form a triplet of isospin. Each pion has overall isospin (I = 1) and third-component isospin equal to its charge (Iz = +1, 0, −1).

Charged pion decays

[edit]

meson (a) and two π+

mesons (b and c). The π−

meson interacts with a nucleus in the emulsion at B.

The π±

mesons have a mass of 139.6 MeV/c2 and a mean lifetime of 2.6033×10−8 s. They decay due to the weak interaction. The primary decay mode of a pion, with a branching fraction of 0.999877, is a leptonic decay into a muon and a muon neutrino:

The second most common decay mode of a pion, with a branching fraction of 0.000123, is also a leptonic decay into an electron and the corresponding electron antineutrino. This "electronic mode" was discovered at CERN in 1958:[12]

The suppression of the electronic decay mode with respect to the muonic one is given approximately (up to a few percent effect of the radiative corrections) by the ratio of the half-widths of the pion–electron and the pion–muon decay reactions, and is a spin effect known as helicity suppression.

Its mechanism is as follows: The negative pion has spin zero; therefore the lepton and the antineutrino must be emitted with opposite spins (and opposite linear momenta) to preserve net zero spin (and conserve linear momentum). However, because the weak interaction is sensitive only to the left chirality component of fields, the antineutrino has always left chirality, which means it is right-handed, since for massless anti-particles the helicity is opposite to the chirality. This implies that the lepton must be emitted with spin in the direction of its linear momentum (i.e., also right-handed). If, however, leptons were massless, they would only interact with the pion in the left-handed form (because for massless particles helicity is the same as chirality) and this decay mode would be prohibited. Therefore, suppression of the electron decay channel comes from the fact that the electron's mass is much smaller than the muon's. The electron is relatively massless compared with the muon, and thus the electronic mode is greatly suppressed relative to the muonic one, virtually prohibited.[13]

Although this explanation suggests that parity violation is causing the helicity suppression, the fundamental reason lies in the vector-nature of the interaction which dictates a different handedness for the neutrino and the charged lepton. Thus, even a parity conserving interaction would yield the same suppression.

Measurements of the above ratio have been considered for decades to be a test of lepton universality. Experimentally, this ratio is 1.233(2)×10−4.[1]

Beyond the purely leptonic decays of pions, some structure-dependent radiative leptonic decays (that is, decay to the usual leptons plus a gamma ray) have also been observed.

Also observed, for charged pions only, is the very rare "pion beta decay" (with branching fraction of about 10−8) into a neutral pion, an electron and an electron antineutrino (or for positive pions, a neutral pion, a positron, and electron neutrino).

The rate at which pions decay is a prominent quantity in many sub-fields of particle physics, such as chiral perturbation theory. This rate is parametrized by the pion decay constant (fπ), related to the wave function overlap of the quark and antiquark, which is about 130 MeV.[14]

Neutral pion decays

[edit]The π0

meson has a mass of 135.0 MeV/c2 and a mean lifetime of 8.5×10−17 s.[1] It decays via the electromagnetic force, which explains why its mean lifetime is much smaller than that of the charged pion (which can only decay via the weak force).

The dominant π0

decay mode, with a branching ratio of BRγγ = 0.98823, is into two photons:

The decay π0

→ 3 γ (as well as decays into any odd number of photons) is forbidden by the C-symmetry of the electromagnetic interaction: The intrinsic C-parity of the π0

is +1, while the C-parity of a system of n photons is (−1)n.

The second largest π0

decay mode (BRγee = 0.01174) is the Dalitz decay (named after Richard Dalitz), which is a two-photon decay with an internal photon conversion resulting in a photon and an electron-positron pair in the final state:

The third largest established decay mode (BR2e2e = 3.34×10−5) is the double-Dalitz decay, with both photons undergoing internal conversion which leads to further suppression of the rate:

The fourth largest established decay mode is the loop-induced and therefore suppressed (and additionally helicity-suppressed) leptonic decay mode (BRee = 6.46×10−8):

The neutral pion has also been observed to decay into positronium with a branching fraction on the order of 10−9. No other decay modes have been established experimentally. The branching fractions above are the PDG central values, and their uncertainties are omitted, but available in the cited publication.[1]

| Particle name |

Particle symbol |

Antiparticle symbol |

Quark content[15] |

Rest mass [MeV/c2] | IG | JPC | S | C | B′ | Mean lifetime [s] | Commonly decays to (> 5% of decays) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pion[1] | π+ |

π− |

ud | 139.57039 ± 0.00018 | 1− | 0− | 0 | 0 | 0 | (2.6033±0.0005)×10−8 | μ+ + ν μ |

| Pion[1] | π0 |

Self | [a] | 134.9768±0.0005 | 1− | 0−+ | 0 | 0 | 0 | (8.5±0.2)×10−17 | γ + γ |

[a] ^ The quark composition of the π0

is not exactly divided between up and down quarks, due to complications from non-zero quark masses.[16]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Zyla, P.A.; et al. (Particle Data Group) (2020). "Review of Particle Physics". Progress of Theoretical and Experimental Physics. 2020 (8): 083C01. doi:10.1093/ptep/ptaa104. hdl:11585/772320.

- ^ Ackermann, M.; et al. (2013). "Detection of the characteristic pion-decay signature in supernova remnants". Science. 339 (6424): 807–811. arXiv:1302.3307. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..807A. doi:10.1126/science.1231160. PMID 23413352. S2CID 29815601.

- ^ Greisen, K. (1966). "End to the Cosmic-Ray Spectrum?". Physical Review Letters. 16 (17): 748–750. Bibcode:1966PhRvL..16..748G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.16.748.

- ^ LATTES, C. M. G.; MUIRHEAD, H.; OCCHIALINI, G. P. S.; POWELL, C. F. (1947). "Processes Involving Charged Mesons". Nature. 159 (4047). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 694–697. Bibcode:1947Natur.159..694L. doi:10.1038/159694a0. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ Vieira, Cássio Leite; Videira, Antonio Augusto Passos (March 2014). "Carried by History: Cesar Lattes, Nuclear Emulsions, and the Discovery of the Pi-meson". Physics in Perspective. 16 (1): 2–36. Bibcode:2014PhP....16....3V. doi:10.1007/s00016-014-0128-6. ISSN 1422-6944. S2CID 122718292.

- ^ Riazuddin (1959-05-15). "Charge radius of the pion". Physical Review. 114 (4): 1184–1186. Bibcode:1959PhRv..114.1184R. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.114.1184. ISSN 0031-899X.

- ^ Bjorklund, R.; Crandall, W.E.; Moyer, B.J.; York, H.F. (1950-01-15). "High energy photons from proton–nucleon collisions" (PDF). Physical Review. 77 (2): 213–218. Bibcode:1950PhRv...77..213B. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.77.213. hdl:2027/mdp.39015086480236. ISSN 0031-899X.

- ^ Zee, Anthony (7 December 2013). Quantum Field Theory, Anthony Zee | Lecture 2 of 4 (lectures given in 2004) (video). aoflex. Quote at 57m04s of 1h26m39s – via YouTube.

- ^ von Essen, C. F.; Bagshaw, M. A.; Bush, S. E.; Smith, A. R.; Kligerman, M. M. (1987). "Long-term results of pion therapy at Los Alamos". International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 13 (9): 1389–1398. doi:10.1016/0360-3016(87)90235-5. PMID 3114189.

- ^ a b Gell-Mann, M.; Renner, B. (1968). "Behavior of current divergences under SU3×SU3" (PDF). Physical Review. 175 (5): 2195–2199. Bibcode:1968PhRv..175.2195G. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.175.2195.

- ^ Brodsky, S.J.; de Teramond, G. F.; Dosch, H.G.; Erlich, J. (2015). "Light-front holographic QCD and emerging confinement". Physics Reports. 584: 1–105. arXiv:1407.8131. Bibcode:2015PhR...584....1B. doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2015.05.001.

- ^ Fazzini, T.; Fidecaro, G.; Merrison, A.; Paul, H.; Tollestrup, A. (1958). "Electron Decay of the Pion". Physical Review Letters. 1 (7): 247–249. Bibcode:1958PhRvL...1..247F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.1.247.

- ^ "Mesons". Hyperphysics. Georgia State U.

- ^ Rosner, J.L.; Stone, S.; et al. (Particle Data Group) (18 December 2013). Leptonic decays of charged pseudo- scalar mesons (PDF). pdg.lbl.gov (Report). Lawrence, CA: Lawrence Berkeley Lab.

- ^ Amsler, C.; et al. (Particle Data Group) (2008). "Quark Model" (PDF). Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ Griffiths, D.J. (1987). Introduction to Elementary Particles. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-60386-4.

Further reading

[edit]- Brown, G.E.; Jackson, A.D. (1976). The Nucleon-Nucleon Interaction. Amsterdam, NL: North-Holland Publishing. ISBN 0-7204-0335-9.

External links

[edit]Overview

Definition and Composition

The pion is a fundamental pseudoscalar meson within the Standard Model of particle physics, classified as a bound state of a quark and an antiquark from the light up (u) and down (d) quark flavors.[10] As the lightest known meson, it plays a central role in the theory of strong interactions mediated by quantum chromodynamics (QCD).[10] The name "pion" is a contraction of "pi meson," reflecting its historical designation in early particle physics nomenclature. In the quark model, the charged pions consist of a valence quark-antiquark pair: the positively charged pion (π⁺) is composed of , while the negatively charged pion (π⁻) is .[11] The neutral pion (π⁰), in contrast, is a quantum mechanical superposition of two flavor states, described by the flavor wave function which ensures orthogonality to the isovector combination and reflects the approximate SU(2) flavor symmetry.[11] This composition arises from the non-relativistic quark model, where mesons are treated as color-singlet states with zero baryon number.[10] Pions belong to an SU(2) isospin triplet, with total isospin quantum number , where the states carry third-component isospin values (π⁺), (π⁰), and (π⁻).[11] This triplet structure emerges naturally from the approximate isospin symmetry between up and down quarks, treating them as degenerate in mass within the quark model framework.[10]Types of Pions

Pions are classified into three types based on their electric charge and isospin quantum numbers, forming an isospin triplet with total isospin . The charged pions, and , carry electric charges of and , respectively, where is the elementary charge, and have third-component isospin values and . The charged pions, together with the neutral pion, form an isospin triplet (I=1), in contrast to the isospin doublet (I=1/2) of the proton-neutron system in nucleon physics, and are key mediators in the strong nuclear force via pion exchange.[12][10] The neutral pion, , is electrically neutral with charge 0 and , completing the isospin triplet alongside the charged pions. Despite its neutrality, the possesses non-zero isospin , distinguishing it from isoscalar particles like the eta meson. In the quark model, the charged pions consist of for and for , while the neutral pion is a superposition .[13][10] Under approximate isospin symmetry, the three pions are treated as degenerate members of the triplet, arising as Nambu-Goldstone bosons from the spontaneous breaking of chiral SU(2)_L × SU(2)_R symmetry to the vector SU(2)_V in quantum chromodynamics. This symmetry breaking generates nearly massless pseudoscalar bosons, with the pions providing the longitudinal components for the axial currents. Observable distinctions, such as the small mass difference between charged and neutral pions (primarily ~4.6 MeV, with charged heavier), stem from electromagnetic effects that break isospin invariance, including quark charge differences and photon exchanges, while strong interaction contributions are smaller.[14][15][16][17]| Pion Type | Charge | Stability Note | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unstable | |||

| Unstable | |||

| 0 | 0 | Unstable |

Physical Properties

Quantum Numbers and Symmetry

Pions possess the intrinsic quantum numbers characteristic of pseudoscalar mesons: total angular momentum quantum number , parity , and, for the neutral pion , charge conjugation . These properties distinguish pions from scalar mesons and dictate their behavior in weak and electromagnetic interactions, where pseudoscalar nature influences decay angular distributions and coupling strengths. Additional conserved quantum numbers for pions include baryon number , strangeness , and hypercharge . These values reflect the absence of net baryonic content and lack of strange quark involvement, positioning pions as the lightest members of the up-down quark sector in the hadron spectrum. The charged pions do not possess a definite charge conjugation eigenvalue due to their non-neutral nature, but the overall pion multiplet maintains consistency under strong interaction symmetries. Under the Lorentz group, pions transform as spin-0 particles, forming a pseudoscalar representation due to their negative parity. The parity operator acts on the pion state as , which enforces selection rules in particle interactions, such as prohibiting parity-conserving transitions to scalar states without orbital angular momentum compensation and influencing the pseudoscalar coupling in effective field theories. This transformation property is crucial for understanding pion-mediated processes, where the negative intrinsic parity requires odd relative parity in initial and final states for allowed strong decays. In the framework of SU(3) flavor symmetry, the three pion states transform in the adjoint representation, specifically the octet (dimension 8), alongside other pseudoscalar mesons like kaons and eta.[18] This placement arises from the approximate symmetry among up, down, and strange quarks, allowing pions to participate in SU(3)-invariant interactions while breaking patterns reveal symmetry violations through mass differences. The isospin triplet structure of pions, with , embeds naturally within this octet under the SU(2) subgroup.Mass, Lifetime, and Charge Radius

The masses of the charged pions π⁺ and π⁻ are identical due to charge conjugation symmetry and are measured to be 139.57039 ± 0.00018 MeV/c².[12] The neutral pion π⁰ has a slightly lower mass of 134.9768 ± 0.0005 MeV/c².[13] This electromagnetic mass splitting of approximately 4.59 MeV arises primarily from the additional self-energy of the charged pions due to their coupling to the photon field in quantum electrodynamics, while the neutral pion lacks this contribution.[12] The mean lifetimes of pions differ significantly owing to their decay mechanisms. Charged pions decay primarily via the weak interaction, with a mean lifetime of (2.6033 ± 0.0005) × 10^{-8} s.[19] In contrast, the neutral pion decays electromagnetically, resulting in a much shorter mean lifetime of (8.43 ± 0.13) × 10^{-17} s.[13] The charge radius of the charged pion, characterized by the mean-square charge radius ⟨r²⟩, is measured to be 0.439 ± 0.008 fm² through analyses of the pion's electromagnetic vector form factor, obtained from processes such as e⁺e⁻ → π⁺π⁻ annihilation and pion electroproduction. This parameter quantifies the spatial distribution of the charge within the pion and is determined experimentally via the slope of the form factor at zero momentum transfer.[20] The following table summarizes the Particle Data Group (PDG) 2024 values for these key parameters, including uncertainties.[13][12]| Property | π⁺, π⁻ | π⁰ |

|---|---|---|

| Mass (MeV/c²) | 139.57039 ± 0.00018 | 134.9768 ± 0.0005 |

| Mean lifetime (s) | (2.6033 ± 0.0005) × 10^{-8} | (8.43 ± 0.13) × 10^{-17} |

| ⟨r²⟩ (fm²) | 0.439 ± 0.008 | — |

Decays and Interactions

Charged Pion Decay Modes

The dominant decay mode of the charged pion, (and similarly ), proceeds via the weak interaction and accounts for virtually all decays, with a branching ratio of .[12] This two-body leptonic process releases a Q-value of approximately 33.9 MeV, determined as the difference between the charged pion mass ( MeV/) and the muon mass ( MeV/), neglecting the massless neutrino.[12] In the pion rest frame, the decay kinematics are fixed by energy-momentum conservation. The muon momentum is given by yielding a precise value of MeV/, as measured in stopped-pion experiments.[21] This results in the muon carrying nearly all the visible energy, with the neutrino taking the remainder to balance momentum. A rare purely leptonic alternative is (and ), with a branching ratio of .[22] This mode is strongly suppressed relative to the muonic decay by a factor of about , primarily due to helicity suppression arising from the V-A structure of the weak interaction: the pseudoscalar pion requires the charged lepton to have the "wrong" helicity (left-handed for positrons/electrons in this chiral theory), which is disfavored for the lighter, more relativistic electron compared to the heavier muon.[22] The suppression has been experimentally verified through precise measurements of the decay ratio in pion decay experiments at facilities like CERN and Fermilab.[22] Another rare channel is the semileptonic decay (and charge conjugate), with a branching ratio of .[12] This process involves a hadronic transition between charged and neutral pions alongside the leptonic current, providing a clean probe of weak form factors but occurring at a much lower rate due to the three-body phase space and small energy release.Neutral Pion Decay Modes

The neutral pion decays almost exclusively through electromagnetic interactions, with the dominant mode being the two-photon decay π⁰ → γγ, which has a branching ratio of 98.823 ± 0.034%. The subdominant Dalitz decay π⁰ → γ e⁺ e⁻ accounts for the remaining fraction, with a branching ratio of 1.174 ± 0.035%. These branching ratios represent the Particle Data Group average as of 2024, incorporating high-statistics data from experiments including the PrimEx experiment at Jefferson Lab, where neutral pions were produced via Primakoff pair production in the Coulomb field of a nuclear target and their decays reconstructed through photon detection.[13] In the rest frame of the neutral pion, the two photons in the primary decay are emitted back-to-back due to conservation of momentum and parity, with each photon carrying equal energy MeV, where MeV/. This kinematic configuration facilitates the identification of the decay in experiments by requiring collinear photons with invariant mass consistent with the pion mass.[13] The extremely short lifetime of the neutral pion, s, is inferred from the partial decay width eV, which dominates the total width. This width is measured by observing the decay length of neutral pions produced in high-energy particle beams, where relativistic boosting extends the effective decay length to detectable scales using precision vertex reconstruction in experiments such as those at CERN's Super Proton Synchrotron. The theoretical prediction from the chiral anomaly in quantum chromodynamics yields eV, where is the fine-structure constant and MeV is the pion decay constant; this matches experimental values to within a few percent, confirming the underlying axial anomaly mechanism.[13] Neutral pion decays are experimentally observed primarily through the conversion of the decay photons into electron-positron pairs in thin detector materials or crystals, such as in the PrimEx setup using a bremsstrahlung-tagged photon beam incident on a diamond or carbon target to coherently produce π⁰ via pair production. This method allows for clean separation of the signal from backgrounds by reconstructing the invariant mass and angular correlations of the photon pairs.Pion Exchange and Nuclear Forces

The pion serves as the primary mediator of the strong nuclear force between nucleons, as proposed in Hideki Yukawa's seminal 1935 theory, where the exchange of a massive pseudoscalar meson accounts for the short-range nature of this interaction.[23] In the one-pion exchange (OPE) model, this force is described by a potential that dominates at longer ranges, approximately beyond 1 fm, and incorporates the pseudoscalar quantum numbers of the pion, which introduce spin and isospin dependencies essential for reproducing nucleon-nucleon (NN) scattering observables. The OPE potential for the NN interaction takes the form where is the pion-nucleon coupling constant, are the isospin Pauli matrices, are the spin Pauli matrices, is the pion mass, and is the nucleon separation.[23] This expression captures the central, spin-dependent component of the force, with the exponential decay yielding a characteristic range of about 1.4 fm, determined by the pion's mass ( MeV) via .[23] The pseudoscalar nature of the pion-nucleon coupling, arising from the interaction Lagrangian , generates not only the spin-spin interaction but also a tensor component that mixes spin and orbital angular momentum, crucial for the spin-dependent structure of nuclear forces.[23] This tensor force provides the primary attraction responsible for the binding of the deuteron, the sole bound NN system, with experimental binding energy of 2.224 MeV and quadrupole moment aligning with OPE predictions when supplemented by shorter-range effects; similarly, NN scattering data at low energies, such as phase shifts in and channels, confirm the spin-dependent OPE contributions.[23] At shorter distances, below about 1 fm, the OPE alone underpredicts the observed repulsion in NN interactions, necessitating extensions to multi-pion exchanges, particularly two-pion exchanges, which introduce intermediate-range attraction and contribute to the short-range repulsion through correlated pion dynamics and higher-order diagrams.[23] These multi-pion contributions, along with contact terms in effective field theory descriptions, model the core repulsion that prevents nucleons from overlapping, as evidenced by the rapid rise in NN scattering cross-sections at high momenta.[23]Theoretical Framework

Quark-Antiquark Model

In the non-relativistic constituent quark model, the pion is described as a spin-singlet, orbital-angular-momentum-zero bound state of a quark and antiquark, denoted as the state of , where is an up or down quark. The mass of the pion arises primarily from the sum of the constituent quark masses plus the binding energy from the confining potential, approximated as , with the constituent mass for up/down quarks MeV; this yields a significant negative binding contribution to account for the observed pion mass of about 140 MeV, reflecting the strong attractive dynamics in the light-quark sector.[24] Due to its total angular momentum , the pion exhibits no fine structure from spin-spin interactions in this model, as the quark and antiquark spins are antiparallel. In contrast, the rho meson, the vector partner in the same quark flavor configuration but in the spin-triplet state, experiences a positive hyperfine splitting from the spin-spin term in the potential, typically modeled as a contact interaction proportional to arising from one-gluon exchange. This results in the observed mass difference MeV, with the hyperfine contribution accounting for roughly 80% of the splitting in light meson systems.[25] The pion decay constant parametrizes the coupling of the pion to the axial current and is defined through the matrix element , where is the axial-vector current; experimental determinations yield MeV in the convention normalizing the low-energy chiral Lagrangian. In the quark model, is computed as an overlap integral of the pion wave function with the quark axial current, providing a measure of the pion's "size" and chiral structure, with predictions aligning closely with this value when using Gaussian or Coulombic wave functions.[26] The quark model also yields predictions for the pion's electromagnetic form factors, which describe its response to virtual photons and probe the internal quark structure. The charge form factor at low momentum transfer is predicted to follow a dipole form, with the mean squared charge radius fm² (corresponding to charge radius fm) extracted from wave function integrals, consistent with dispersive analyses and PDG value of 0.434 ± 0.008 fm². For the magnetic form factor, which vanishes at due to the pion's spin-zero nature, the model predicts a mean squared magnetic radius fm², arising from relativistic corrections and quark orbital contributions in light-front formulations. These form factors, computed via Drell-Yan frames or overlap integrals of the wave functions weighted by quark charges, emphasize the pion's compact size and validate the model's spectroscopic success. Recent lattice QCD calculations, such as those yielding fm, further support these predictions.[27][28][12][29]Role in Quantum Chromodynamics

In quantum chromodynamics (QCD), the pions arise as the pseudo-Nambu–Goldstone bosons resulting from the spontaneous breaking of the chiral symmetry group SU(2)_L × SU(2)_R down to the diagonal vector subgroup SU(2)_V in the vacuum.90623-1) This breaking is driven by the non-perturbative dynamics of QCD at low energies, where the vacuum develops a nonzero expectation value for the quark bilinear operator, leading to a preferred direction that selects the vector symmetry while breaking the axial part. In the chiral limit of vanishing up and down quark masses (m_u = m_d = 0), the three pions (π⁺, π⁻, π⁰) are exactly massless, corresponding to the three broken axial generators of the symmetry.90623-1) The small observed pion masses are induced by the explicit breaking of chiral symmetry due to the light but nonzero current quark masses m_u and m_d, as quantified by the Gell-Mann–Oakes–Renner relation:where f_π ≈ 92 MeV is the pion decay constant and ⟨\bar{q} q⟩ is the chiral condensate in the QCD vacuum, with |⟨\bar{q} q⟩| ≈ (250 MeV)^3.00219-5) This relation connects the pion mass squared to the strength of explicit symmetry breaking and the order parameter of spontaneous breaking, providing a key test of chiral symmetry in QCD. The effective low-energy theory capturing pion dynamics is chiral perturbation theory (ChPT), constructed as an expansion in powers of momentum p around the chiral limit. The leading-order Lagrangian, invariant under the full chiral group, takes the nonlinear sigma model form:

where Σ = exp(i \vec{\pi} \cdot \vec{\tau} / f_π) incorporates the pion fields \vec{π} in the adjoint representation of SU(2).90023-4) Higher-order terms, such as those at O(p^4), include explicit breaking effects from quark masses and are essential for precise calculations of pion scattering amplitudes and other processes.90195-8) The pion also appears as a pole in the two-point correlation function of the axial-vector current, reflecting partial conservation of the axial current (PCAC) and influencing weak interaction processes like beta decay through the axial form factor structure. Lattice QCD simulations, performed directly from the QCD path integral, confirm the pion mass values and their extrapolation to the physical point, aligning with ChPT predictions in the chiral limit.

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\pi ^{+}&\longrightarrow \mu ^{+}+\nu _{\mu }\\[2pt]\pi ^{-}&\longrightarrow \mu ^{-}+{\overline {\nu }}_{\mu }\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/696602558151fda06fcf1b466ef9ebeff066b068)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\pi ^{+}&\longrightarrow {\rm {e}}^{+}+\nu _{e}\\[2pt]\pi ^{-}&\longrightarrow {\rm {e}}^{-}+{\overline {\nu }}_{e}\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d8d650a562fd96e3ee01ebf26b6a08db0ddd34d2)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\pi ^{+}&\longrightarrow \pi ^{0}+{\rm {e}}^{+}+\nu _{e}\\[2pt]\pi ^{-}&\longrightarrow \pi ^{0}+{\rm {e}}^{-}+{\overline {\nu }}_{e}\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/177f4006b7d5e5a1caa09f1808e23d44f6a3a747)