Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Haplogroup R1a

View on Wikipedia

| Haplogroup R1a | |

|---|---|

| |

| Possible time of origin | 22,000[1] to 25,000[2] years ago |

| Possible place of origin | Eurasia |

| Ancestor | Haplogroup R1 |

| Descendants | R-M459, R-YP4141 |

| Defining mutations |

|

| Highest frequencies | See List of R1a frequency by population |

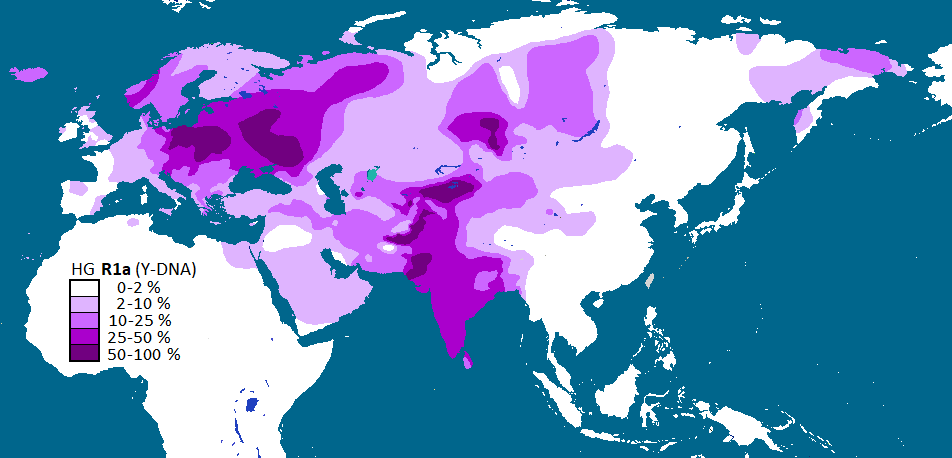

Haplogroup R1a (R-M420), is a human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup which is distributed in a large region in Eurasia, extending from Scandinavia and Central Europe to Central Asia, southern Siberia and South Asia.[3][2]

The R1a (R-M420) subclade diverged from R1 (R-M173) 15-25,000[2][4][5] years ago, its subclade M417 (R1a1a1) diversified c. 3,400-5,800 years ago.[6][5] The place of origin of the subclade plays a role in the debate about the origins of Proto-Indo-Europeans.

The SNP mutation R-M420 was discovered after R-M17 (R1a1a), which resulted in a reorganization of the lineage in particular establishing a new paragroup (designated R-M420*) for the relatively rare lineages which are not in the R-SRY10831.2 (R1a1) branch leading to R-M17.

Origins

[edit]R1a origins

[edit]The genetic divergence of R1a (M420) is estimated to have occurred 25,000[2] years ago, which is the time of the last glacial maximum. A 2014 study by Peter A. Underhill et al., using 16,244 individuals from over 126 populations from across Eurasia, concluded that there was "a compelling case for the Middle East, possibly near present-day Iran, as the geographic origin of hg R1a".[2] The ancient DNA record has shown the first R1a during the Mesolithic in Eastern Hunter-Gatherers (from Eastern Europe, c. 13,000 years ago),[7][8] and the earliest case of R* among Upper Paleolithic Ancient North Eurasians,[9] from which the Eastern Hunter-Gatherers predominantly derive their ancestry.[10] The genome of an individual belonging to the R1a5 subclade, dated to 10785–10626 BCE, from Peschanitsa, Arkhangelsk, Russia, and identified as a Western Russian Hunter-Gatherer, was published in January 2021.[11]

Diversification of R1a1a1 (M417) and ancient migrations

[edit]

According to Underhill et al. (2014), the downstream M417 (R1a1a1) subclade diversified into Z282 (R1a1a1b1a) and Z93 (R1a1a1b2) circa 5,800 years ago "in the vicinity of Iran and Eastern Turkey".[6][note 1] Even though R1a occurs as a Y-chromosome haplogroup among speakers of various languages such as Slavic and Indo-Iranian, the question of the origins of R1a1a is relevant to the ongoing debate concerning the urheimat of the Proto-Indo-European people, and may also be relevant to the origins of the Indus Valley civilization. R1a shows a strong correlation with Indo-European languages of Southern and Western Asia, Central and Eastern Europe and to Scandinavia[13][3] being most prevalent in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and South Asia. In Europe, Z282 is prevalent particularly while in Asia Z93 dominates. The connection between Y-DNA R-M17 and the spread of Indo-European languages was first noted by T. Zerjal and colleagues in 1999.[14]

Indo-European relation

[edit]Proposed steppe dispersal of R1a1a

[edit]Semino et al. (2000) proposed Ukrainian origins, and a postglacial spread of the R1a1 haplogroup during the Late Glacial Maximum, subsequently magnified by the expansion of the Kurgan culture into Europe and eastward.[15] Spencer Wells proposes Central Asian origins, suggesting that the distribution and age of R1a1 points to an ancient migration corresponding to the spread by the Kurgan people in their expansion from the Eurasian steppe.[16] According to Pamjav et al. (2012), R1a1a diversified in the Eurasian Steppes or the Middle East and Caucasus region:

Inner and Central Asia is an overlap zone for the R1a1-Z280 and R1a1-Z93 lineages [which] implies that an early differentiation zone of R1a1-M198 conceivably occurred somewhere within the Eurasian Steppes or the Middle East and Caucasus region as they lie between South Asia and Central- and Eastern Europe.[17]

Three genetic studies in 2015 gave support to the Kurgan theory of Gimbutas regarding the Indo-European Urheimat. According to those studies, haplogroups R1b and R1a, now the most common in Europe (R1a is also common in South Asia) would have expanded from the Pontic–Caspian steppes, along with the Indo-European languages; they also detected an autosomal component present in modern Europeans which was not present in Neolithic Europeans, which would have been introduced with paternal lineages R1b and R1a, as well as Indo-European languages.[18][19][20]

Silva et al. (2017) noted that R1a in South Asia most "likely spread from a single Central Asian source pool, there do seem to be at least three and probably more R1a founder clades within the Indian subcontinent, consistent with multiple waves of arrival."[21] According to Martin P. Richards, co-author of Silva et al. (2017), the prevalence of R1a in India was "very powerful evidence for a substantial Bronze Age migration from central Asia that most likely brought Indo-European speakers to India."[22][23]

Possible Yamnaya or Corded Ware origins

[edit]

David Anthony considers the Yamnaya culture to be the Indo-European Urheimat.[24][25] According to Haak et al. (2015), a massive migration from the Yamnaya culture northwards took place c. 2,500 BCE, accounting for 75% of the genetic ancestry of the Corded Ware culture, noting that R1a and R1b may have "spread into Europe from the East after 3,000 BCE".[26] Yet, all their seven Yamnaya samples belonged to the R1b-M269 subclade,[26] but no R1a1a has been found in their Yamnaya samples. This raises the question where the R1a1a in the Corded Ware culture came from, if it was not from the Yamnaya culture.[27]

According to Marc Haber, the absence of haplogroup R1a-M458 in Afghanistan does not support a Pontic-Caspian steppe origin for the R1a lineages in modern Central Asian populations.[28]

According to Leo Klejn, the absence of haplogroup R1a in Yamnaya remains (despite its presence in Eneolithic Samara and Eastern Hunter Gatherer populations) makes it unlikely that Europeans inherited haplogroup R1a from Yamnaya.[29]

Archaeologist Barry Cunliffe has said that the absence of haplogroup R1a in Yamnaya specimens is a major weakness in Haak's proposal that R1a has a Yamnaya origin.[30]

Semenov & Bulat (2016) do argue for a Yamnaya origin of R1a1a in the Corded Ware culture, noting that several publications point to the presence of R1a1 in the Comb Ware culture.[31][note 2]

Proposed South Asian origins

[edit]Kivisild et al. (2003) have proposed either South or West Asia,[32][note 3] while Mirabal et al. (2009) see support for both South and Central Asia.[13] Sengupta et al. (2006) have proposed Indian origins.[33] Thanseem et al. (2006) have proposed either South or Central Asia.[34] Sahoo et al. (2006) have proposed either South or West Asia.[35] Thangaraj et al. (2010) have also proposed a South Asian origin.[36] Sharma et al.(2009) theorizes the existence of R1a in India beyond 18,000 years to possibly 44,000 years in origin.[1]

A number of studies from 2006 to 2010 concluded that South Asian populations have the highest STR diversity within R1a1a,[37][38][13][3][1][39] and subsequent older TMRCA datings.[note 4] R1a1a is present among both higher (Brahmin) castes and lower castes, and while the frequency is higher among Brahmin castes, the oldest TMRCA datings of the R1a haplogroup occur in the Saharia tribe, a scheduled caste of the Bundelkhand region of Central India.[1][39]

From these findings some researchers argued that R1a1a originated in South Asia,[38][1][note 5] excluding a more recent, yet minor, genetic influx from Indo-European migrants in northwestern regions such as Afghanistan, Balochistan, Punjab, and Kashmir.[38][37][3][note 6]

The conclusion that R1a originated in India has been questioned by more recent research,[21][41][note 7] offering an argument that R1a arrived in India with multiple waves of migration.[21][42]

Proposed Transcaucasia and West Asian origins and possible influence on Indus Valley Civilization

[edit]Haak et al. (2015) found that part of the Yamnaya ancestry derived from the Middle East and that neolithic techniques probably arrived at the Yamnaya culture from the Balkans.[note 8] The Rössen culture (4,600–4,300 BC), which was situated on Germany and predates the Corded Ware culture, an old subclade of R1a, namely L664, can still be found.[note 9]

Part of the South Asian genetic ancestry derives from west Eurasian populations, and some researchers have implied that Z93 may have come to India via Iran[44] and expanded there during the Indus Valley civilization.[2][45]

Mascarenhas et al. (2015) proposed that the roots of Z93 lie in West Asia, and proposed that "Z93 and L342.2 expanded in a southeasterly direction from Transcaucasia into South Asia",[44] noting that such an expansion is compatible with "the archeological records of eastward expansion of West Asian populations in the 4th millennium BCE culminating in the so-called Kura-Araxes migrations in the post-Uruk IV period."[44] Yet, Lazaridis noted that sample I1635 of Lazaridis et al. (2016), their Armenian Kura-Araxes sample, carried Y-haplogroup R1b1-M415(xM269)[note 10] (also called R1b1a1b-CTS3187).[46][unreliable source?]

According to Underhill et al. (2014) the diversification of Z93 and the "early urbanization within the Indus Valley ... occurred at [5,600 years ago] and the geographic distribution of R1a-M780 (Figure 3d[note 11]) may reflect this."[2][note 12] Poznik et al. (2016) note that "striking expansions" occurred within R1a-Z93 at c. 4,500–4,000 years ago, which "predates by a few centuries the collapse of the Indus Valley Civilisation."[45][note 13]

However, according to Narasimhan et al. (2018), steppe pastoralists are a likely source for R1a in India.[48][note 14]

Phylogeny

[edit]The R1a family tree now has three major levels of branching, with the largest number of defined subclades within the dominant and best known branch, R1a1a (which will be found with various names such as "R1a1" in relatively recent but not the latest literature).

Topology

[edit]The topology of R1a is as follows (codes [in brackets] non-isogg codes):[12][49][verification needed][50][2][51] Tatiana et al. (2014) "rapid diversification process of K-M526 likely occurred in Southeast Asia, with subsequent westward expansions of the ancestors of haplogroups R and Q."[52]

- P P295/PF5866/S8 (also known as K2b2).

- R (R-M207)[50][12]

- R*

- R1 (R-M173)

- R1*[50]

- R1a (M420)[50] (Eastern Europe, Asia)[2]

- R1a*[12]

- R1a1[50] (M459/PF6235,[50] SRY1532.2/SRY10831.2[50])

- R1a1 (M459)[50][12]

- R1a1a (M17, M198)[50]

- R1a1a1 (M417, page7)[50]

- R1a1a1a (CTS7083/L664/S298)[50]

- R1a1a1b (S224/Z645, S441/Z647)[50]

- R1a1a1b1 (PF6217/S339/Z283)[50]

- R1a1a1b1a (Z282)[50] [R1a1a1a*] (Z282)[53] (Eastern Europe)

- R1a1a1b1a1[50] [The old topological code is R1a1a1b*,which is outdated and might lead to some confusion.][53] (M458)[50][53] [R1a1a1g] (M458)[51]

- R1a1a1b1a2[50] (S466/Z280, S204/Z91)[50]

- R1a1a1b1a2a[50]

- R1a1a1b1a2b (CTS1211)[50] [R1a1a1c*] (M558)[53] [R-CTS1211] (V2803/CTS3607/S3363/M558, CTS1211/S3357, Y34/FGC36457)[12]

- R1a1a1b1a2b3* (M417+, Z645+, Z283+, Z282+, Z280+, CTS1211+, CTS3402, Y33+, CTS3318+, Y2613+) (Gwozdz's Cluster K)[49][verification needed]

- R1a1a1b1a2b3a (L365/S468)[50]

- R1a1a1b1a3 (Z284)[50] [R1a1a1a1] (Z284)[53]

- R1a1a1b1a (Z282)[50] [R1a1a1a*] (Z282)[53] (Eastern Europe)

- R1a1a1b2 (F992/S202/Z93)[50] [R1a1a2*] (Z93, M746)[53] (Central Asia, South Asia and West Asia)

- R1a1a1b1 (PF6217/S339/Z283)[50]

- [R1a1a1c] (M64.2, M87, M204)[51]

- [R1a1a1d] (P98)[51]

- [R1a1a1d2a][54]

- [R1a1a1e] (PK5)[51]

- R1a1a1 (M417, page7)[50]

- R1b (M343) (Western Europe)

- R2 (India)

Haplogroup R

[edit]| Haplogroup R phylogeny |

R-M173 (R1)

[edit]R1a is distinguished by several unique markers, including the M420 mutation. It is a subclade of Haplogroup R-M173 (previously called R1). R1a has the sister-subclades Haplogroup R1b-M343, and the paragroup R-M173*.

R-M420 (R1a)

[edit]R1a, defined by the mutation M420, has two primary branches: R-M459 (R1a1) and R-YP4141 (R1a2).

As of 2025, ten ancient basal R1a* genotypes have been recovered and published, from remains found in Estonia, Poland, Russia, and Ukraine; the oldest sample (Vasilevka 497) dated to c. 8700 BCE, and excavated in the Vasylivka, Bakhmut Raion, Donetsk Oblast.[55][5]

R-YP4141 (R1a2)

[edit]R1a2 (R-YP4141) has two branches R1a2a (R-YP5018) and R1a2b (R-YP4132).[56]

This rare primary subclade was initially regarded as part of a paragroup of R1a*, defined by SRY1532.2 (and understood to always exclude M459 and its synonyms SRY10831.2, M448, L122, and M516).[3][57]

YP4141 later replaced SRY1532.2 – which was found to be unreliable – and the R1a(xR-M459) group was redefined as R1a2. It is relatively unusual, though it has been tested in more than one survey. Sahoo et al. (2006) reported R-SRY1532.2* for 1/15 Himachal Pradesh Rajput samples.[38] Underhill et al. (2009) reported 1/51 in Norway, 3/305 in Sweden, 1/57 Greek Macedonians, 1/150 (or 2/150) Iranians, 2/734 ethnic Armenians, 1/141 Kabardians, 1/121 Omanis, 1/164 in the United Arab Emirates, and 3/612 in Turkey. Testing of 7224 more males in 73 other Eurasian populations showed no sign of this category.[3]

The oldest known example genotyped is from a set of remains, dating to c. 3500 BCE, recovered from the Kumyshanskaya Cave, in Russia.[5]

R-M459 (R1a1)

[edit]The major subclade R-M459 includes an overwhelming majority of individuals within R1a more broadly.

Ancient R-M459 genotypes, dating to c. 8650 BCE, have been recovered from two sets of remains excavated at Minino, Russia.[5]

R-YP1272 (R1a1b)

[edit]R-YP1272, also known as R-M459(xM198), is an extremely rare primary subclade of R1a1. It has been found in three individuals, from Belarus, Tunisia and the Coptic community in Egypt respectively.[58]

R-M17/M198 (R1a1a)

[edit]The following SNPs are associated with R1a1a:

| SNP | Mutation | Y-position (NCBI36) | Y-position (GRCh37) | RefSNP ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M17 | INS G | 20192556 | 21733168 | rs3908 |

| M198 | C->T | 13540146 | 15030752 | rs2020857 |

| M512 | C->T | 14824547 | 16315153 | rs17222146 |

| M514 | C->T | 17884688 | 19375294 | rs17315926 |

| M515 | T->A | 12564623 | 14054623 | rs17221601 |

| L168 | A->G | 14711571 | 16202177 | - |

| L449 | C->T | 21376144 | 22966756 | - |

| L457 | G->A | 14946266 | 16436872 | rs113195541 |

| L566 | C->T | - | - | - |

R-M417 (R1a1a1)

[edit]R1a1a1 (R-M417) is the most widely found subclade, in two variations which are found respectively in Europe (R1a1a1b1 (R-Z282) ([R1a1a1a*] (R-Z282) (Underhill 2014)[2]) and Central and South Asia (R1a1a1b2 (R-Z93) ([R1a1a2*] (R-Z93) Underhill 2014)[2]).

The oldest known basal R1a1a1 genotype so far published has been dated to c. 5650 BCE, and was recovered from a site at Trestiana, Romania.[5]

R-Z282 (R1a1a1b1a) (Eastern Europe)

[edit]This large subclade appears to encompass most of the R1a1a found in Europe.[17]

- R1a1a1b1a [R1a1a1a* (Underhill (2014))] (R-Z282*) occurs in northern Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia at a frequency of c. 20%.[2]

- R1a1a1b1a3 [R1a1a1a1 (Underhill (2014))] (R-Z284) occurs in Northwest Europe and peaks at c. 20% in Norway.[2]

- R1a1a1c (M64.2, M87, M204) is apparently rare: it was found in 1 of 117 males typed in southern Iran.[59]

R-M458 (R1a1a1b1a1)

[edit]

R-M458 is a mainly Slavic SNP, characterized by its own mutation, and was first called cluster N. Underhill et al. (2009) found it to be present in modern European populations roughly between the Rhine catchment and the Ural Mountains and traced it to "a founder effect that ... falls into the early Holocene period, 7.9±2.6 KYA." (Zhivotovsky speeds, 3x overvalued)[3] M458 was found in one skeleton from a 14th-century grave field in Usedom, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany.[60] The paper by Underhill et al. (2009) also reports a surprisingly high frequency of M458 in some Northern Caucasian populations (18% among Ak Nogai,[61] 7.8% among Qara Nogai and 3.4% among Abazas).[62]

R-L260 (R1a1a1b1a1a)

[edit]R1a1a1b1a1a (R-L260), commonly referred to as West Slavic or Polish, is a subclade of the larger parent group R-M458, and was first identified as an STR cluster by Pawlowski et al. 2002. In 2010 it was verified to be a haplogroup identified by its own mutation (SNP).[63] It apparently accounts for about 8% of Polish men, making it the most common subclade in Poland. Outside of Poland it is less common.[64] In addition to Poland, it is mainly found in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, and is considered "clearly West Slavic". The founding ancestor of R-L260 is estimated to have lived between 2000 and 3000 years ago, i.e. during the Iron Age, with significant population expansion less than 1,500 years ago.[65]

R-M334

[edit]R-M334 ([R1a1a1g1],[51] a subclade of [R1a1a1g] (M458)[51] c.q. R1a1a1b1a1 (M458)[50]) was found by Underhill et al. (2009) only in one Estonian man and may define a very recently founded and small clade.[3]

R1a1a1b1a2 (S466/Z280, S204/Z91)

[edit]R1a1a1b1a2b3* (Gwozdz's Cluster K)

[edit]R1a1a1b1a2b3* (M417+, Z645+, Z283+, Z282+, Z280+, CTS1211+, CTS3402, Y33+, CTS3318+, Y2613+) (Gwozdz's Cluster K)[49][verification needed] is a STR based group that is R-M17(xM458). This cluster is common in Poland but not exclusive to Poland.[65]

R1a1a1b1a2b3a (R-L365)

[edit]R1a1a1b1a2b3a (R-L365)[50] was early called Cluster G.[citation needed]

R1a1a1b2 (R-Z93) (Asia)

[edit]| Region | People | N | R-M17 | R-M434 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Freq. (%) | Number | Freq. (%) | |||

| Pakistan | Baloch | 60 | 9 | 15% | 5 | 8% |

| Pakistan | Makrani | 60 | 15 | 25% | 4 | 7% |

| Middle East | Oman | 121 | 11 | 9% | 3 | 2.5% |

| Pakistan | Sindhi | 134 | 65 | 49% | 2 | 1.5% |

| Table only shows positive sets from N = 3667 derived from 60 Eurasian populations sample.[3] | ||||||

This large subclade appears to encompass most of the R1a1a found in Asia, being related to Indo-European migrations (including Scythians, Indo-Aryan migrations and so on).[17]

- R-Z93* or R1a1a1b2* (R1a1a2* in Underhill (2014)) is most common (>30%) in the South Siberian Altai region of Russia, cropping up in Kyrgyzstan (6%) and in all Iranian populations (1-8%).[2] The oldest published R-Z93 genotypes being sampled from graves, dated to c. 2650 - 2700 BCE, in Naumovskoye, and Khanevo, Vologda Oblast, and Khaldeevo, Rostov District, Russia.[5]

- R-Z2125 occurs at highest frequencies in Kyrgyzstan and in Afghan Pashtuns (>40%). At a frequency of >10%, it is also observed in other Afghan ethnic groups and in some populations in the Caucasus and Iran.[2]

- R-M560 is very rare and was only observed in four samples: two Burushaski speakers (north Pakistan), one Hazara (Afghanistan), and one Iranian Azerbaijani.[2]

- R-M780 (R1a1b2a2*) occurs at high frequency in South Asia: India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and the Himalayas. Turkey share R1a (12.1%) sublineages.[66] Roma from Slovakia share 3% of R1a[67] The group also occurs at >3% in some Iranian populations and is present at >30% in Roma from Croatia and Hungary.[2]

Geographic distribution of R1a1a

[edit]

Pre-historical

[edit]In Mesolithic Europe, R1a is characteristic of Eastern Hunter-Gatherers (EHGs).[68] A male EHG of the Veretye culture buried at Peschanitsa near Lake Lacha in Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia c. 10,700 BCE was found to be a carrier of the paternal haplogroup R1a5-YP1301 and the maternal haplogroup U4a.[69][70][68] A male, named PES001, from Peschanitsa in northwestern Russia was found to carry R1a5, and dates to at least 10,600 years ago.[7] More examples include the males Minino II (V) and Minino II (I/1), with the former carrying R1a1 and the latter R1a respectively, with the former being at 10,600 years old and the latter at least 10,400 years old respectively, both from Minino in northwestern Russia.[71] A Mesolithic male from Karelia c. 8,800 BCE to 7950 BCE has been found to be carrying haplogroup R1a.[72] A Mesolithic male buried at Deriivka c. 7000 BCE to 6700 BCE carried the paternal haplogroup R1a and the maternal U5a2a.[20] Another male from Karelia from c. 5,500 to 5,000 BC, who was considered an EHG, carried haplogroup R1a.[18] A male from the Comb Ceramic culture in Kudruküla c. 5,900 BCE to 3,800 BCE has been determined to be a carrier of R1a and the maternal U2e1.[73] According to archaeologist David Anthony, the paternal R1a-Z93 was found at the Oskol river near a no longer existing kolkhoz "Alexandria", Ukraine c. 4000 BCE, "the earliest known sample to show the genetic adaptation to lactase persistence (13910-T)."[74] R1a has been found in the Corded Ware culture,[75][76] in which it is predominant.[77] Examined males of the Bronze Age Fatyanovo culture belong entirely to R1a, specifically subclade R1a-Z93.[68][69][78]

Haplogroup R1a has later been found in ancient fossils associated with the Urnfield culture;[79] as well as the burial of the remains of the Sintashta,[19] Andronovo,[80] the Pazyryk,[81] Tagar,[80] Tashtyk,[80] and Srubnaya cultures, the inhabitants of ancient Tanais,[82] in the Tarim mummies,[83] and the aristocracy of Xiongnu.[84] The skeletal remains of a father and his two sons, from an archaeological site discovered in 2005 near Eulau (in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany) and dated to about 2600 BCE, tested positive for the Y-SNP marker SRY10831.2. The Ysearch number for the Eulau remains is 2C46S. The ancestral clade was thus present in Europe at least 4600 years ago, in association with one site of the widespread Corded Ware culture.[75]

Europe

[edit]In Europe, the R1a1a sub-clade is primarily characteristic of Balto-Slavic populations, with two exceptions: southern Slavs and northern Russians.[85] The highest frequency of R1a1a in Europe is observed in Sorbs (63%),[86] a West Slavic ethnic group, followed by Hungarians (60%).[15] Other groups with significant R1a1a, ranging from 27% to up to 58%, include Czechs, Poles, Slovenians, Slovaks, Moldovans, Belarusians, Rusyns, Ukrainians, and Russians.[85][86][15] R1a frequency decreases in northeastern Russian populations down to 20%–30%, in contrast to central-southern Russia, where its frequency is twice as high. In the Baltics, R1a1a frequencies decrease from Lithuania (45%) to Estonia (around 30%).[87][88][89][15][90]

There is also a significant presence in peoples of Germanic descent, with highest levels in Norway, Sweden and Iceland, where between 20 and 30% of men are in R1a1a.[91][92] Vikings and Normans may have also carried the R1a1a lineage further out, accounting for at least part of the small presence in the British Isles, the Canary Islands, and Sicily.[93][94] Haplogroup R1a1a averages between 10 and 30% in Germans, with a peak in Rostock at 31.3%.[95] R1a1a is found at a very low frequency among Dutch people (3.7%)[15] and is virtually absent in Danes.[96]

In Southern Europe R1a1a is not common, but significant levels have been found in pockets, such as in the Pas Valley in Northern Spain, areas of Venice, and Calabria in Italy.[97][better source needed] The Balkans shows wide variation between areas with significant levels of R1a1a, for example 36–39% in Slovenia,[98] 27–34% in Croatia,[88][99][100][101][102] and over 30% in Greek Macedonia, but less than 10% in Albania, Kosovo and parts of Greece south of Olympus gorge.[103][89][15]

R1a is virtually composed only of the Z284 subclade in Scandinavia. In Slovenia, the main subclade is Z282 (Z280 and M458), although the Z284 subclade was found in one sample of a Slovenian. There is a negligible representation of Z93 in Turkey, 12,1%[66][2] West Slavs and Hungarians are characterized by a high frequency of the subclade M458 and a low Z92, a subclade of Z280. Hundreds of Slovenian samples and Czechs lack the Z92 subclade of Z280, while Poles, Slovaks, Croats and Hungarians only show a very low frequency of Z92.[2] The Balts, East Slavs, Serbs, Macedonians, Bulgarians and Romanians demonstrate a ratio Z280>M458 and a high, up to a prevailing share of Z92.[2] Balts and East Slavs have the same subclades and similar frequencies in a more detailed phylogeny of the subclades.[104][105] The Russian geneticist Oleg Balanovsky speculated that there is a predominance of the assimilated pre-Slavic substrate in the genetics of East and West Slavic populations, according to him the common genetic structure which contrasts East Slavs and Balts from other populations may suggest the explanation that the pre-Slavic substrate of the East and West Slavs consisted most significantly of Baltic-speakers, which at one point predated the Slavs in the cultures of the Eurasian steppe according to archaeological and toponymic references.[note 15]

Asia

[edit]Central Asia

[edit]Zerjal et al. (2002) found R1a1a in 64% of a sample of the Tajiks of Tajikistan and 63% of a sample of the Kyrgyz of Kyrgyzstan.[106]

Haber et al. (2012) found R1a1a-M17 in 26.0% (53/204) of a set of samples from Afghanistan, including 60% (3/5) of a sample of Nuristanis, 51.0% (25/49) of a sample of Pashtuns, 30.4% (17/56) of a sample of Tajiks, 17.6% (3/17) of a sample of Uzbeks, 6.7% (4/60) of a sample of Hazaras, and in the only sampled Turkmen individual.[107]

Di Cristofaro et al. (2013) found R1a1a-M198/M17 in 56.3% (49/87) of a pair of samples of Pashtuns from Afghanistan (including 20/34 or 58.8% of a sample of Pashtuns from Baghlan and 29/53 or 54.7% of a sample of Pashtuns from Kunduz), 29.1% (37/127) of a pool of samples of Uzbeks from Afghanistan (including 28/94 or 29.8% of a sample of Uzbeks from Jawzjan, 8/28 or 28.6% of a sample of Uzbeks from Sar-e Pol, and 1/5 or 20% of a sample of Uzbeks from Balkh), 27.5% (39/142) of a pool of samples of Tajiks from Afghanistan (including 22/54 or 40.7% of a sample of Tajiks from Balkh, 9/35 or 25.7% of a sample of Tajiks from Takhar, 4/16 or 25.0% of a sample of Tajiks from Samangan, and 4/37 or 10.8% of a sample of Tajiks from Badakhshan), 16.2% (12/74) of a sample of Turkmens from Jawzjan, and 9.1% (7/77) of a pair of samples of Hazara from Afghanistan (including 7/69 or 10.1% of a sample of Hazara from Bamiyan and 0/8 or 0% of a sample of Hazara from Balkh).[108]

Malyarchuk et al. (2013) found R1a1-SRY10831.2 in 30.0% (12/40) of a sample of Tajiks from Tajikistan.[109]

Ashirbekov et al. (2017) found R1a-M198 in 6.03% (78/1294) of a set of samples of Kazakhs from Kazakhstan. R1a-M198 was observed with greater than average frequency in the study's samples of the following Kazakh tribes: 13/41 = 31.7% of a sample of Suan, 8/29 = 27.6% of a sample of Oshaqty, 6/30 = 20.0% of a sample of Qozha, 4/29 = 13.8% of a sample of Qypshaq, 1/8 = 12.5% of a sample of Tore, 9/86 = 10.5% of a sample of Jetyru, 4/50 = 8.0% of a sample of Argyn, 1/13 = 7.7% of a sample of Shanyshqyly, 8/122 = 6.6% of a sample of Alimuly, 3/46 = 6.5% of a sample of Alban. R1a-M198 also was observed in 5/42 = 11.9% of a sample of Kazakhs of unreported tribal affiliation.[110]

South Asia

[edit]In South Asia, R1a1a has often been observed in a number of demographic groups.[38][37]

South Asian populations have the highest STR diversity within R1a1a,[37][38][13][3][1][39] and subsequent older TMRCA datings.[note 16] In India, high frequencies of this haplogroup is observed in West Bengal Brahmins (72%) in the east,[37] Bhanushali (67%) and Gujarat Lohanas (60%) in the west,[3] Uttar Pradesh Brahmins (68%), Punjab/Haryana Khatris (67%) and Ahirs (63%) in the north,[1][37][3] and Karnataka Medars (39%) in the south.[111] It has also been found in several South Indian Dravidian-speaking Adivasis including the Chenchu (26%) of Andhra Pradesh and Kota of Andhra Pradesh (22.58%)[112] and the Kallar of Tamil Nadu suggesting that R1a1a is widespread in Tribal Southern Indians.[32]

Besides these, studies show high percentages in regionally diverse groups such as Manipuris (50%)[3] to the extreme North East and among Punjabis (47%)[32] to the extreme North West.

In Pakistan it is found at 80% among Yusufzai tribe of Pashtuns (51%) from Swat District,[113] 71% among the Mohanna community in Sindh province to the south and 46% among the Baltis of Gilgit-Baltistan to the north.[3]

Among the Sinhalese of Sri Lanka, 23% were found to be R1a1a (R-SRY1532) positive.[114] Hindus of Chitwan District in the Terai region Nepal show it at 69%.[115]

East Asia

[edit]The frequency of R1a1a is comparatively low among some Turkic-speaking groups like Yakuts, yet levels are higher (19 to 28%) in certain Turkic or Mongolic-speaking groups of Northwestern China, such as the Bonan, Dongxiang, Salar, and Uyghurs.[16][116][117]

A Chinese paper published in 2018 found R1a-Z94 in 38.5% (15/39) of a sample of Keriyalik Uyghurs from Darya Boyi / Darya Boye Village, Yutian County, Xinjiang (于田县达里雅布依乡), R1a-Z93 in 28.9% (22/76) of a sample of Dolan Uyghurs from Horiqol township, Awat County, Xinjiang (阿瓦提县乌鲁却勒镇), and R1a-Z93 in 6.3% (4/64) of a sample of Loplik Uyghurs from Karquga / Qarchugha Village, Yuli County, Xinjiang (尉犁县喀尔曲尕乡). R1a(xZ93) was observed only in one of 76 Dolan Uyghurs.[118] Note that Darya Boyi Village is located in a remote oasis formed by the Keriya River in the Taklamakan Desert. A 2011 Y-DNA study found Y-dna R1a1 in 10% of a sample of southern Hui people from Yunnan, 1.6% of a sample of Tibetan people from Tibet (Tibet Autonomous Region), 1.6% of a sample of Xibe people from Xinjiang, 3.2% of a sample of northern Hui from Ningxia, 9.4% of a sample of Hazak (Kazakhs) from Xinjiang, and rates of 24.0%, 22.2%, 35.2%, 29.2% in 4 different samples of Uyghurs from Xinjiang, 9.1% in a sample of Mongols from Inner Mongolia. A different subclade of R1 was also found in 1.5% of a sample of northern Hui from Ningxia.[119] in the same study there were no cases of R1a detected at all in 6 samples of Han Chinese in Yunnan, 1 sample of Han in Guangxi, 5 samples of Han in Guizhou, 2 samples of Han in Guangdong, 2 samples of Han in Fujian, 2 samples of Han in Zhejiang, 1 sample of Han in Shanghai, 1 samples of Han in Jiangxi, 2 samples of Han in Hunan, 1 sample of Han in Hubei, 2 samples of Han in Sichuan, 1 sample of Han in Chongqing, 3 samples of Han in Shandong, 5 samples of Han in Gansu, 3 samples of Han in Jilin and 2 samples of Han in Heilongjiang.[120] 40% of Salars, 45.2% of Tajiks of Xinjiang, 54.3% of Dongxiang, 60.6% of Tatars and 68.9% of Kyrgyz in Xinjiang in northwestern China tested in one sample had R1a1-M17. Bao'an (Bonan) had the most haplogroup diversity of 0.8946±0.0305 while the other ethnic minorities in northwestern China had a high haplogroup diversity like Central Asians, of 0.7602±0.0546.[121]

In Eastern Siberia, R1a1a is found among certain indigenous ethnic groups including Kamchatkans and Chukotkans, and peaking in Itel'man at 22%.[122]

Southeast Asia

[edit]Y-haplogroups R1a-M420 and R2-M479 are found in Ede (8.3% and 4.2%) and Giarai (3.7% and 3.7%) peoples in Vietnam. The Cham additionally have haplogroups R-M17 (13.6%) and R-M124 (3.4%).

R1a1a1b2a2a (R-Z2123) and R1a1 are found in Khmer peoples from Thailand (3.4%) and Cambodia (7.2%) respectively. Haplogroup R1a1a1b2a1b (R-Y6) is also found among Kuy peoples (5%).

According to Changmai et al. (2022), these haplogroup frequencies originate from South Asians, who left a cultural and genetic legacy in Southeast Asia since the first millennium CE.[123]

West Asia

[edit]R1a1a has been found in various forms, in most parts of Western Asia, in widely varying concentrations, from almost no presence in areas such as Jordan, to much higher levels in parts of Kuwait and Iran. The Shimar (Shammar) Bedouin tribe in Kuwait show the highest frequency in the Middle East at 43%.[124][125][126]

Wells 2001, noted that in the western part of the country, Iranians show low R1a1a levels, while males of eastern parts of Iran carried up to 35% R1a1a. Nasidze et al. 2004 found R1a1a in approximately 20% of Iranian males from the cities of Tehran and Isfahan. Regueiro 2006 in a study of Iran, noted much higher frequencies in the south than the north.

A newer study has found 20.3% R-M17* among Kurdish samples which were taken in the Kurdistan Province in western Iran, 19% among Azerbaijanis in West Azerbaijan, 9.7% among Mazandaranis in North Iran in the province of Mazandaran, 9.4% among Gilaks in province of Gilan, 12.8% among Persian and 17.6% among Zoroastrians in Yazd, 18.2% among Persians in Isfahan, 20.3% among Persians in Khorasan, 16.7% Afro-Iranians, 18.4% Qeshmi "Gheshmi", 21.4% among Persian Bandari people in Hormozgan and 25% among the Baloch people in Sistan and Baluchestan Province.[127]

Di Cristofaro et al. (2013) found haplogroup R1a in 9.68% (18/186) of a set of samples from Iran, though with a large variance ranging from 0% (0/18) in a sample of Iranians from Tehran to 25% (5/20) in a sample of Iranians from Khorasan and 27% (3/11) in a sample of Iranians of unknown provenance. All Iranian R1a individuals carried the M198 and M17 mutations except one individual in a sample of Iranians from Gilan (n=27), who was reported to belong to R1a-SRY1532.2(xM198, M17).[108]

Malyarchuk et al. (2013) found R1a1-SRY10831.2 in 20.8% (16/77) of a sample of Persians collected in the provinces of Khorasan and Kerman in eastern Iran, but they did not find any member of this haplogroup in a sample of 25 Kurds collected in the province of Kermanshah in western Iran.[109]

Further to the north of these Western Asian regions on the other hand, R1a1a levels start to increase in the Caucasus, once again in an uneven way. Several populations studied have shown no sign of R1a1a, while highest levels so far discovered in the region appears to belong to speakers of the Karachay-Balkar language among whom about one quarter of men tested so far are in haplogroup R1a1a.[3]

Historic naming of R1a

[edit]The historic naming system commonly used for R1a was inconsistent in different published sources, because it changed often; this requires some explanation.

In 2002, the Y Chromosome Consortium (YCC) proposed a new naming system for haplogroups (YCC 2002), which has now become standard. In this system, names with the format "R1" and "R1a" are "phylogenetic" names, aimed at marking positions in a family tree. Names of SNP mutations can also be used to name clades or haplogroups. For example, as M173 is currently the defining mutation of R1, R1 is also R-M173, a "mutational" clade name. When a new branching in a tree is discovered, some phylogenetic names will change, but by definition all mutational names will remain the same.

The widely occurring haplogroup defined by mutation M17 was known by various names, such as "Eu19", as used in (Semino et al. 2000) in the older naming systems. The 2002 YCC proposal assigned the name R1a to the haplogroup defined by mutation SRY1532.2. This included Eu19 (i.e. R-M17) as a subclade, so Eu19 was named R1a1. Note, SRY1532.2 is also known as SRY10831.2[citation needed] The discovery of M420 in 2009 has caused a reassignment of these phylogenetic names.(Underhill et al. 2009 and ISOGG 2012) R1a is now defined by the M420 mutation: in this updated tree, the subclade defined by SRY1532.2 has moved from R1a to R1a1, and Eu19 (R-M17) from R1a1 to R1a1a.

More recent updates recorded at the ISOGG reference webpage involve branches of R-M17, including one major branch, R-M417.

| 2002 scheme proposed in (YCC 2002) | 2009 scheme as per (Underhill et al. 2009) | ISOGG tree as per January 2011 [citation needed] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ According to Family Tree,[who?] they diversified c. 5,000 years ago.[12]

- ^ Semenov & Bulat (2016) refer to the following publications:

- Haak, Wolfgang (2015). "Massive migration from the steppe is a source for Indo-European languages in Europe". Nature. 522 (7555): 207–211. arXiv:1502.02783. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..207H. bioRxiv 10.1101/013433. doi:10.1038/NATURE14317. PMC 5048219. PMID 25731166.

- Mathieson, Iain (2015). "Eight thousand years of natural selection in Europe". bioRxiv 10.1101/016477.

- Chekunova Е.М., Yartseva N.V., Chekunov М.К., Мazurkevich А.N. The First Results of the Genotyping of the Aboriginals and Human Bone Remains of the Archeological Memorials of the Upper Podvin'e. // Archeology of the lake settlements of IV—II Thousands BC: The chronology of cultures and natural environment and climatic rhythms. Proceedings of the International Conference, Devoted to the 50-year Research of the Pile Settlements on the North-West of Russia. St. Petersburg, November 13–15, 2014.

- Jones, ER; Gonzalez-Fortes, G; Connell, S; Siska, V; Eriksson, A; Martiniano, R; McLaughlin, RL; Gallego Llorente, M; Cassidy, LM; Gamba, C; Meshveliani, T; Bar-Yosef, O; Müller, W; Belfer-Cohen, A; Matskevich, Z; Jakeli, N; Higham, TF; Currat, M; Lordkipanidze, D; Hofreiter, M; Manica, A; Pinhasi, R; Bradley, DG (2015). "Upper Palaeolithic genomes reveal deep roots of modern Eurasians". Nat Commun. 6: 8912. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.8912J. doi:10.1038/ncomms9912. PMC 4660371. PMID 26567969.

- ^ Kivisild et al. (2003): "Haplogroup R1a, previously associated with the putative Indo-Aryan invasion, was found at its highest frequency in Punjab but also at a relatively high frequency (26%) in the Chenchu tribe. This finding, together with the higher R1a-associated short tandem repeat diversity in India and Iran compared with Europe and central Asia, suggests that southern and western Asia might be the source of this haplogroup."[32]

- ^ Sengupta (2006): "We found that the influence of Central Asia on the pre-existing gene pool was minor. The ages of accumulated microsatellite variation in the majority of Indian haplogroups exceed 10,000–15,000 years, which attests to the antiquity of regional differentiation. Therefore, our data do not support models that invoke a pronounced recent genetic input from Central Asia to explain the observed genetic variation in South Asia."

- ^ South-Asian origins:

* Sahoo et al. (2006): "... one should expect to observe dramatically lower genetic variation among Indian Rla lineages. In fact, the opposite is true: the STR haplotype diversity on the background of R1a in Central Asia (and also in Eastern Europe) has already been shown to be lower than that in India (6). Rather, the high incidence of R1* and Rla throughout Central Asian European populations (without R2 and R* in most cases) is more parsimoniously explained by gene flow in the opposite direction, possibly with an early founder effect in South or West Asia.[40]

* Sharma et al. (2009): "A peculiar observation of the highest frequency (up to 72.22%) of Y-haplogroup R1a1* in Brahmins hinted at its presence as a founder lineage for this caste group. Further, observation of R1a1* in different tribal population groups, existence of Y-haplogroup R1a* in ancestors and extended phylogenetic analyses of the pooled dataset of 530 Indians, 224 Pakistanis and 276 Central Asians and Eurasians bearing the R1a1* haplogroup supported the autochthonous origin of R1a1 lineage in India and a tribal link to Indian Brahmins. However, it is important to discover novel Y-chromosomal binary marker(s) for a higher resolution of R1a1* and confirm the present conclusions." - ^ Though Sengupta (2006) did concede that "[R1a1 and R2] could have actually arrived in southern India from a southwestern Asian source region multiple times." In full: "The widespread geographic distribution of HG R1a1-M17 across Eurasia and the current absence of informative subdivisions defined by binary markers leave uncertain the geographic origin of HG R1a1-M17. However, the contour map of R1a1-M17 variance shows the highest variance in the northwestern region of India ... The question remains of how distinctive is the history of L1 relative to some or all of R1a1 and R2 representatives. This uncertainty neutralizes previous conclusions that the intrusion of HGs R1a1 and R2 from the northwest in Dravidian-speaking southern tribes is attributable to a single recent event. [R1a1 and R2] could have actually arrived in southern India from a southwestern Asian source region multiple times, with some episodes considerably earlier than others. Considerable archeological evidence exists regarding the presence of Mesolithic peoples in India (Kennedy 2000), some of whom could have entered the subcontinent from the northwest during the late Pleistocene epoch. The high variance of R1a1 in India (table 12), the spatial frequency distribution of R1a1 microsatellite variance clines (fig. 4), and expansion time (table 11) support this view."[37]

- ^ Lalueza-Fox: "Some years ago, local scientists supported the view that the existence of an R1a Y chromosome was not attributable to a foreign gene flow but instead that this lineage had emerged on the subcontinent and spread from there. But the phylogenetic reconstruction of this haplogroup did not support this view."[41]

- ^ Yet, Haak et al. also explicitly state: "a type of Near Eastern ancestry different from that which was introduced by early farmers".[clarification needed][43]

- ^ According to Family Tree DNA, L664 formed 4,700 ybp, that is, 2,700 BCE.[12]

- ^ Lazaridis, Twitter, 18 June 2016: "I1635 (Armenia_EBA) is R1b1-M415(xM269). We'll be sure to include in the revision. Thanks to the person who noticed! #ILovePreprints."[unreliable source?]

See also "Big deal of 2016: the territory of present-day Iran cannot be the Indo-European homeland". Eurogenes Blog. November 26, 2016,[unreliable source?] for a discussion of the same topic. - ^ See map for M780 distribution at Dieneke's Anthropology Blog, Major new article on the deep origins of Y-haplogroup R1a (Underhill et al. 2014)[47]

- ^ According to Family Tree DNA, M780 formed 4700 ybp.[12] This dating coincides with the eastward movement between 2800 and 2600 BCE of the Yamnaya culture into the region of the Poltavka culture, a predecessor of the Sintashta culture, from which the Indo-Iranians originated. M780 is concentrated in the Ganges Valley, the locus of the classic Vedic society.

- ^ Poznik et al. (2016) calculate with a generation time of 30 years; a generation time of 20 years yields other results.

- ^ "The evidence that the Steppe_MLBA [Middle to Late Bronze Age] cluster is a plausible source for the Steppe ancestry in South Asia is also supported by Y chromosome evidence, as haplogroup R1a which is of the Z93 subtype common in South Asia today [Underhill et al. (2014), Silva et al. (2017)] was of high frequency in Steppe_MLBA (68%) (16), but rare in Steppe_EMBA [Early to Middle Bronze Age] (absent in our data)."[48]

- ^ Балановский (2015), p. 208 (in Russian) Прежде всего, это преобладание в славянских популяциях дославянского субстрата — двух ассимилированных ими генетических компонентов – восточноевропейского для западных и восточных славян и южноевропейского для южных славян...Можно с осторожностью предположить, что ассимилированный субстратмог быть представлен по преимуществу балтоязычными популяциями. Действительно, археологические данные указыва ют на очень широкое распространение балтских групп перед началом расселения славян. Балтскийсубстрату славян (правда, наряду с финно-угорским) выявляли и антропологи. Полученные нами генетические данные — и на графиках генетических взаимоотношений, и по доле общих фрагментов генома — указывают, что современные балтские народы являются ближайшими генетически ми соседями восточных славян. При этом балты являются и лингвистически ближайшими род ственниками славян. И можно полагать, что к моменту ассимиляции их генофонд не так сильно отличался от генофонда начавших свое широкое расселение славян. Поэтому если предположить,что расселяющиеся на восток славяне ассимилировали по преимуществу балтов, это может объяснить и сходство современных славянских и балтских народов друг с другом, и их отличия от окружающих их не балто-славянских групп Европы...В работе высказывается осторожное предположение, что ассимилированный субстрат мог быть представлен по преимуществу балтоязычными популяциями. Действительно, археологические данные указывают на очень широкое распространение балтских групп перед началом расселения славян. Балтский субстрат у славян (правда, наряду с финно-угорским) выявляли и антропологи. Полученные в этой работе генетические данные — и на графиках генетических взаимоотношений, и по доле общих фрагментов генома — указывают, что современные балтские народы являются ближайшими генетическими соседями восточных славян.

- ^ Sengupta (2006): "We found that the influence of Central Asia on the pre-existing gene pool was minor. The ages of accumulated microsatellite variation in the majority of Indian haplogroups exceed 10,000–15,000 years, which attests to the antiquity of regional differentiation. Therefore, our data do not support models that invoke a pronounced recent genetic input from Central Asia to explain the observed genetic variation in South Asia."

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Sharma et al. 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Underhill et al. 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Underhill et al. 2009.

- ^ "YTree v13.01.00 - R1". YFull.Com.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Welcome to FamilyTreeDNA Discover". FamilyTreeDNA Discover. Retrieved January 19, 2025.

- ^ a b Underhill et al. 2014, p. 130.

- ^ a b Saag, Lehti; Vasilyev, Sergey V.; Varul, Liivi; Kosorukova, Natalia V.; Gerasimov, Dmitri V.; Oshibkina, Svetlana V.; Griffith, Samuel J.; Solnik, Anu; Saag, Lauri; D'Atanasio, Eugenia; Metspalu, Ene (January 2021). "Genetic ancestry changes in Stone to Bronze Age transition in the East European plain". Science Advances. 7 (4) eabd6535. Bibcode:2021SciA....7.6535S. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abd6535. PMC 7817100. PMID 33523926.

- ^ Haak, Wolfgang; Lazaridis, Iosif; Patterson, Nick; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Llamas, Bastien; Brandt, Guido; Nordenfelt, Susanne; Harney, Eadaoin; Stewardson, Kristin; Fu, Qiaomei (February 10, 2015). "Massive migration from the steppe is a source for Indo-European languages in Europe". bioRxiv 013433. arXiv:1502.02783. doi:10.1101/013433. S2CID 196643946. Archived from the original on December 23, 2019. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ^ Raghavan, Maanasa; Skoglund, Pontus; Graf, Kelly E.; Metspalu, Mait; Albrechtsen, Anders; Moltke, Ida; Rasmussen, Simon; Stafford Jr, Thomas W.; Orlando, Ludovic; Metspalu, Ene; Karmin, Monika (January 2014). "Upper Palaeolithic Siberian genome reveals dual ancestry of Native Americans". Nature. 505 (7481): 87–91. Bibcode:2014Natur.505...87R. doi:10.1038/nature12736. PMC 4105016. PMID 24256729.

- ^ Narasimhan, Vagheesh M.; Patterson, Nick; Moorjani, Priya; Rohland, Nadin; Bernardos, Rebecca; Mallick, Swapan; Lazaridis, Iosif; Nakatsuka, Nathan; Olalde, Iñigo; Lipson, Mark; Kim, Alexander M. (September 6, 2019). "The formation of human populations in South and Central Asia". Science. 365 (6457) eaat7487. doi:10.1126/science.aat7487. PMC 6822619. PMID 31488661.

Y chromosome haplogroup types R1b or R1a not represented in Iran and Turan in this period ...

- ^ Saag, Lehti; Vasilyev, Sergey V.; Varul, Liivi; Kosorukova, Natalia V.; Gerasimov, Dmitri V.; Oshibkina, Svetlana V.; Griffith, Samuel J.; Solnik, Anu; Saag, Lauri; D'Atanasio, Eugenia; Metspalu, Ene; Reidla, Maere; Rootsi, Siiri; Kivisild, Toomas; Scheib, Christiana Lyn (January 20, 2021). "Genetic ancestry changes in Stone to Bronze Age transition in the East European plain". Science Advances. 7 (4) eabd6535. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abd6535. PMC 7817100. PMID 33523926.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "R1a tree". YFull. Archived from the original on August 19, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Mirabal et al. 2009.

- ^ Zerjal, T.; et al. (1999). "The use of Y-chromosomal DNA variation to investigate population history: recent male spread in Asia and Europe". In Papiha, S. S.; Deka, R. & Chakraborty, R. (eds.). Genomic diversity: applications in human population genetics. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. pp. 91–101. ISBN 978-0-3064-6295-5.

- ^ a b c d e f Semino et al. 2000.

- ^ a b Wells 2001.

- ^ a b c Pamjav et al. 2012.

- ^ a b Haak et al. 2015.

- ^ a b Allentoft et al. 2015.

- ^ a b Mathieson et al. 2015.

- ^ a b c Silva et al. 2017.

- ^ Joseph, Tony (June 16, 2017). "How genetics is settling the Aryan migration debate". The Hindu. Archived from the original on October 4, 2023. Retrieved June 2, 2019.

- ^ Silva, Marina; Oliveira, Marisa; Vieira, Daniel; Brandão, Andreia; Rito, Teresa; Pereira, Joana B.; Fraser, Ross M.; Hudson, Bob; Gandini, Francesca; Edwards, Ceiridwen; Pala, Maria; Koch, John; Wilson, James F.; Pereira, Luísa; Richards, Martin B. (March 23, 2017). "A genetic chronology for the Indian Subcontinent points to heavily sex-biased dispersals". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 17 (1): 88. Bibcode:2017BMCEE..17...88S. doi:10.1186/s12862-017-0936-9. ISSN 1471-2148. PMC 5364613. PMID 28335724.

- ^ Anthony 2007.

- ^ Anthony & Ringe 2015.

- ^ a b Haak et al. 2015, p. 5.

- ^ Semenov & Bulat 2016.

- ^ Haber et al. 2012"R1a1a7-M458 was absent in Afghanistan, suggesting that R1a1a-M17 does not support, as previously thought [47], expansions from the Pontic Steppe [3], bringing the Indo-European languages to Central Asia and India."

- ^ Klejn, Leo S. (April 22, 2017). "The Steppe Hypothesis of Indo-European Origins Remains to be Proven". Acta Archaeologica. 88 (1): 193–204. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0390.2017.12184.x. ISSN 0065-101X. Archived from the original on December 25, 2022. Retrieved November 23, 2022. "As for the Y-chromosome, it was already noted in Haak, Lazaridis et al. (2015) that the Yamnaya from Samara had Y-chromosomes which belonged to R-M269 but did not belong to the clade common in Western Europe (p. 46 of supplement). Also, not a single R1a in Yamnaya unlike Corded Ware (R1a-dominated)."

- ^ Koch, John T.; Cunliffe, Barry (2016). Celtic from the West 3: Atlantic Europe in the Metal Ages. Oxbow Books. p. 634. ISBN 978-1-78570-228-0. Archived from the original on November 23, 2022. Retrieved November 23, 2022.

- ^ Semenov & Bulat 2016, p. 41.

- ^ a b c d Kivisild et al. 2003.

- ^ Sengupta S, Zhivotovsky LA, King R, Mehdi SQ, Edmonds CA, Chow CE, et al. (February 2006). "Polarity and temporality of high-resolution y-chromosome distributions in India identify both indigenous and exogenous expansions and reveal minor genetic influence of Central Asian pastoralists". American Journal of Human Genetics. 78 (2): 202–221. doi:10.1086/499411. PMC 1380230. PMID 16400607."Although considerable cultural impact on social hierarchy and language in South Asia is attributable to the arrival of nomadic Central Asian pastoralists, genetic data (mitochondrial and Y chromosomal) have yielded dramatically conflicting inferences on the genetic origins of tribes and castes of South Asia. We sought to resolve this conflict, using high-resolution data on 69 informative Y-chromosome binary markers and 10 microsatellite markers from a large set of geographically, socially, and linguistically representative ethnic groups of South Asia. We found that the influence of Central Asia on the pre-existing gene pool was minor. The ages of accumulated microsatellite variation in the majority of Indian haplogroups exceed 10,000–15,000 years, which attests to the antiquity of regional differentiation. Therefore, our data do not support models that invoke a pronounced recent genetic input from Central Asia to explain the observed genetic variation in South Asia. R1a1 and R2 haplogroups indicate demographic complexity that is inconsistent with a recent single history.ASSOCIATED MICROSATELLITE ANALYSES OF THE HIGH-FREQUENCY R1A1 HAPLOGROUP CHROMOSOMES INDICATE INDEPENDENT RECENT HISTORIES OF THE INDUS VALLEY AND THE PENINSULAR INDIAN REGION."

- ^ Thanseem I, Thangaraj K, Chaubey G, Singh VK, Bhaskar LV, Reddy BM, et al. (August 2006). "Genetic affinities among the lower castes and tribal groups of India: inference from Y chromosome and mitochondrial DNA". BMC Genetics. 7: 42. doi:10.1186/1471-2156-7-42. PMC 1569435. PMID 16893451.

- ^ Sahoo S, Singh A, Himabindu G, Banerjee J, Sitalaximi T, Gaikwad S, et al. (January 2006). "A prehistory of Indian Y chromosomes: evaluating demic diffusion scenarios". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (4): 843–848. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103..843S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0507714103. PMC 1347984. PMID 16415161.

- ^ Thangaraj K, Naidu BP, Crivellaro F, Tamang R, Upadhyay S, Sharma VK, et al. (December 2010). Cordaux R (ed.). "The influence of natural barriers in shaping the genetic structure of Maharashtra populations". PLOS ONE. 5 (12) e15283. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...515283T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015283. PMC 3004917. PMID 21187967.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sengupta 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f Sahoo et al. 2006.

- ^ a b c Thangaraj et al. 2010.

- ^ Sahoo et al. 2006, p. 845-846.

- ^ a b Lalueza-Fox, C. (2022). Inequality: A Genetic History. MIT Press. pp. 81–82. ISBN 978-0-262-04678-7. Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ^ Narasimhan et al. 2019.

- ^ Haak et al. 2015, p. 4.

- ^ a b c Mascarenhas et al. 2015, p. 9.

- ^ a b Poznik et al. 2016, p. 5.

- ^ Arame's English blog, Y DNA from ancient Near East Archived November 27, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Dienekes' Anthropology Blog: Major new article on the deep origins of Y-haplogroup R1a (Underhill et al. 2014)". March 27, 2014. Archived from the original on December 20, 2019. Retrieved December 20, 2019.[unreliable source?]

- ^ a b Narasimhan et al. 2018.

- ^ a b c "About Us". Family Tree DNA. Archived from the original on August 15, 2019. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa "ISOGG 2017 Y-DNA Haplogroup R". isogg.org. Archived from the original on February 10, 2007. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Haplogroup R (Y-DNA) - SNPedia". www.snpedia.com. Archived from the original on May 5, 2018. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

- ^ Karafet et al. 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Underhill et al. 2014, p. 125.

- ^ "R1a in Yamnaya". Eurogenes Blog. March 21, 2016. Archived from the original on May 5, 2018. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

- ^ "haplotree.info - ancientdna.info. Map based on All Ancient DNA v. 2.07.26". haplotree.info. Retrieved January 19, 2025.

- ^ "R1a YTree".

- ^ Krahn, Thomas. "Draft Y-Chromosome Tree". Family Tree DNA. Archived from the original on May 26, 2013. Retrieved December 7, 2012.

- ^ "R-M459 YTree".

- ^ Regueiro 2006.

- ^ Freder, Janine (2010). Die mittelalterlichen Skelette von Usedom: Anthropologische Bearbeitung unter besonderer Berücksichtigung des ethnischen Hintergrundes [Anthropological investigation in due consideration of the ethnical background] (Thesis) (in German). Freie Universität Berlin. p. 86. doi:10.17169/refubium-8995.

- ^ https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/tyurki-kavkaza-sravnitelnyy-analiz-genofondov-po-dannym-o-y-hromosome Archived November 7, 2023, at the Wayback Machine "высокая частота R1a среди кубанских ногайцев (субветвь R1a1a1g-M458 забирает 18%"

- ^ Underhill, P. A.; et al. (2009). "Separating the post-Glacial coancestry of European and Asian y chromosomes within haplogroup R1a". European Journal of Human Genetics. 18 (4): 479–484. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2009.194. PMC 2987245. PMID 19888303.

- ^ Gwozdz, Peter (August 6, 2018). "Polish Y-DNA Clades". Archived from the original on July 15, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- ^ Pawlowski et al. 2002.

- ^ a b Gwozdz 2009.

- ^ a b Kars, M. E.; Başak, A. N.; Onat, O. E.; Bilguvar, K.; Choi, J.; Itan, Y.; Çağlar, C.; Palvadeau, R.; Casanova, J. L.; Cooper, D. N.; Stenson, P. D.; Yavuz, A.; Buluş, H.; Günel, M.; Friedman, J. M.; Özçelik, T. (2021). "The genetic structure of the Turkish population reveals high levels of variation and admixture". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 118 (36) e2026076118. Bibcode:2021PNAS..11826076K. doi:10.1073/pnas.2026076118. PMC 8433500. PMID 34426522.

- ^ Petrejcíková, EVA; Soták, Miroslav; Bernasovská, Jarmila; Bernasovský, Ivan; Sovicová, Adriana; Bôziková, Alexandra; Boronová, Iveta; Švícková, Petra; Gabriková, Dana; MacEková, Sona (2009). "Y-haplogroup frequencies in the Slovak Romany population". Anthropological Science. 117 (2): 89–94. doi:10.1537/ase.080422.

- ^ a b c Saag et al. 2020, p. 5.

- ^ a b Saag et al. 2020, p. 29, Table 1.

- ^ Saag et al. 2020, Supplementary Data 2, Row 4.

- ^ Posth, Cosimo; Yu, He; Ghalichi, Ayshin; Rougier, Hélène; Crevecoeur, Isabelle; Huang, Yilei; Ringbauer, Harald; Rohrlach, Adam B.; Nägele, Kathrin; Villalba-Mouco, Vanessa; Radzeviciute, Rita; Ferraz, Tiago; Stoessel, Alexander; Tukhbatova, Rezeda; Drucker, Dorothée G. (March 1, 2023). "Palaeogenomics of Upper Palaeolithic to Neolithic European hunter-gatherers". Nature. 615 (7950): 117–126. Bibcode:2023Natur.615..117P. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-05726-0. hdl:10256/23099. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 9977688. PMID 36859578.

- ^ Fu et al. 2016.

- ^ Saag et al. 2017.

- ^ Anthony 2019, pp. 16, 17.

- ^ a b Haak et al. 2008.

- ^ Brandit et al. 2013.

- ^ Malmström et al. 2019, p. 2.

- ^ Saag et al. 2020, Supplementary Data 2, Rows 5-49.

- ^ Schweitzer, D. (March 23, 2008). "Lichtenstein Cave Data Analysis" (PDF). dirkschweitzer.net. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 14, 2011. Summary in English of Schilz (2006).

- ^ a b c Keyser et al. 2009.

- ^ Ricaut et al. 2004.

- ^ Korniyenko, I. V.; Vodolazhsky D. I. "Использование нерекомбинантных маркеров Y-хромосомы в исследованиях древних популяций (на примере поселения Танаис)" [The use of non-recombinant markers of the Y-chromosome in the study of ancient populations (on the example of the settlement of Tanais)]. Материалы Донских антропологических чтений [Materials of the Don Anthropological Readings]. Rostov-on-Don: Rostov Research Institute of Oncology, 2013.

- ^ Chunxiang Li et al. 2010.

- ^ Kim et al. 2010.

- ^ a b Balanovsky et al. 2008.

- ^ a b Behar et al. 2003.

- ^ Kasperaviciūte, Kucinskas & Stoneking 2005.

- ^ a b Battaglia et al. 2008.

- ^ a b Rosser et al. 2000.

- ^ Tambets et al. 2004.

- ^ Bowden et al. 2008.

- ^ Dupuy et al. 2005.

- ^ Passarino et al. 2002.

- ^ Capelli et al. 2003.

- ^ Kayser et al. 2005.

- ^ Sanchez, J; Børsting, C; Hallenberg, C; Buchard, A; Hernandez, A; Morling, N (2003). "Multiplex PCR and minisequencing of SNPs—a model with 35 Y chromosome SNPs". Forensic Science International. 137 (1): 74–84. doi:10.1016/S0379-0738(03)00299-8. PMID 14550618.

- ^ Scozzari et al. 2001.

- ^ Underhill, Peter A. (January 1, 2015). "The phylogenetic and geographic structure of Y-chromosome haplogroup R1a". European Journal of Human Genetics. 23 (1): 124–131. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2014.50. PMC 4266736. PMID 24667786.

- ^ L. Barać; et al. (2003). "Y chromosomal heritage of Croatian population and its island isolates". European Journal of Human Genetics. 11 (7): 535–42. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200992. PMID 12825075. S2CID 15822710.

- ^ S. Rootsi; et al. (2004). "Phylogeography of Y-Chromosome Haplogroup I Reveals Distinct Domains of Prehistoric Gene Flow in Europe" (PDF). American Journal of Human Genetics. 75 (1): 128–137. doi:10.1086/422196. PMC 1181996. PMID 15162323. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 5, 2020. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ M. Peričić; et al. (2005). "High-resolution phylogenetic analysis of southeastern Europe traces major episodes of paternal gene flow among Slavic populations". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 22 (10): 1964–75. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi185. PMID 15944443.

- ^ M. Peričić; et al. (2005). "Review of Croatian Genetic Heritage as Revealed by Mitochondrial DNA and Y Chromosomal Lineages". Croatian Medical Journal. 46 (4): 502–513. PMID 16100752.

- ^ Pericić et al. 2005.

- ^ "Untitled". pereformat.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on March 15, 2016. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- ^ "Untitled". www.rodstvo.ru. Archived from the original on September 16, 2021. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- ^ Zerjal et al. 2002.

- ^ Haber et al. 2012.

- ^ a b Di Cristofaro et al. 2013.

- ^ a b Malyarchuk et al. 2013.

- ^ Ashirbekov et al. 2017.

- ^ Shah 2011.

- ^ Arunkumar 2012.

- ^ Tariq, Muhammad; Ahmad, Habib; Hemphill, Brian E.; Farooq, Umar; Schurr, Theodore G. (2022). "Contrasting maternal and paternal genetic histories among five ethnic groups from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 1027. Bibcode:2022NatSR..12.1027T. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-05076-3. PMC 8770644. PMID 35046511.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Toomas Kivisild; Siiri Rootsi; Mait Metspalu; Ene Metspalu; Juri Parik; Katrin Kaldma; Esien Usanga; Sarabjit Mastana; Surinder S. Papiha; Richard Villems. "The Genetics of Language and Farming Spread in India" (PDF). In P. Bellwwood; C. Renfrew (eds.). Examining the farming/language dispersal hypothesis. McDonald Institute Monographs. Cambridge University. pp. 215–222. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 19, 2006. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

- ^ Fornarino et al. 2009.

- ^ Wang et al. 2003.

- ^ Zhou et al. 2007.

- ^ Liu Shu-hu et al. 2018.

- ^ Zhong et al. 2011.

- ^ Zhong, Hua; Shi, Hong; Qi, Xue-Bin; Duan, Zi-Yuan; Tan, Ping-Ping; Jin, Li; Su, Bing; Ma, Runlin Z. (2011). "Extended Y Chromosome Investigation Suggests Postglacial Migrations of Modern Humans into East Asia via the Northern Route". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 28 (1): 717–727. doi:10.1093/molbev/msq247. PMID 20837606.

- ^ Shou, Wei-Hua; Qiao, Wn-Fa; Wei, Chuan-Yu; Dong, Yong-Li; Tan, Si-Jie; Shi, Hong; Tang, Wen-Ru; Xiao, Chun-Jie (2010). "Y-chromosome distributions among populations in Northwest China identify significant contribution from Central Asian pastoralists and lesser influence of western Eurasians". Journal of Human Genetics. 55 (5): 314–322. doi:10.1038/jhg.2010.30. PMID 20414255. S2CID 23002493.

- ^ Lell et al. 2002.

- ^ Changmai, Piya; Jaisamut, Kitipong; Kampuansai, Jatupol; et al. (2022). "Indian genetic heritage in Southeast Asian populations". PLOS Genetics. 18 (2) e1010036. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1010036. PMC 8853555. PMID 35176016.

- ^ Mohammad et al. 2009.

- ^ Nasidze et al. 2004.

- ^ Nasidze et al. 2005.

- ^ Grugni et al. 2012.

Sources

[edit]- Allentoft, Morten E.; Sikora, Martin; Sjögren, Karl-Göran; Rasmussen, Simon; Rasmussen, Morten; Stenderup, Jesper; Damgaard, Peter B.; Schroeder, Hannes; et al. (2015). "Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia". Nature. 522 (7555): 167–172. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..167A. doi:10.1038/nature14507. PMID 26062507. S2CID 4399103. Archived from the original on July 13, 2019. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- Anthony, David W. (2007), The Horse The Wheel And Language. How Bronze-Age Riders From the Eurasian Steppes Shaped The Modern World, Princeton University Press

- Anthony, David (Spring–Summer 2019). "Archaeology, Genetics, and Language in the Steppes: A Comment on Bomhard". Journal of Indo-European Studies. 47 (1–2). Archived from the original on May 3, 2024. Retrieved January 9, 2020.

- Anthony, David; Ringe, Don (2015), "The Indo-European Homeland from Linguistic and Archaeological Perspectives", Annual Review of Linguistics, 1: 199–219, doi:10.1146/annurev-linguist-030514-124812

- Shah, A. M.; Tamang, R.; Moorjani, P.; Rani, D. S.; Govindaraj, P.; Kulkarni, G.; Bhattacharya, T.; Mustak, M. S.; Bhaskar, L. V. K. S.; Reddy, A. G.; Gadhvi, D.; Gai, P. B.; Chaubey, G.; Patterson, N.; Reich, D.; Tyler-Smith, C.; Singh, L.; Thangaraj, K. (2011). "Indian Siddis: African Descendants with Indian Admixture". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 89 (1): 154–61. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.05.030. PMC 3135801. PMID 21741027.

- ArunKumar, G; Soria-Hernanz, DF; Kavitha, VJ; Arun, VS; Syama, A; Ashokan, KS (2012). "Population Differentiation of Southern Indian Male Lineages Correlates with Agricultural Expansions Predating the Caste System". PLOS ONE. 7 (11) e50269. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...750269A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0050269. PMC 3508930. PMID 23209694.

- Ashirbekov, E. E.; et al. (2017). "Distribution of Y-Chromosome Haplogroups of the Kazakh from the South Kazakhstan, Zhambyl, and Almaty Regions" (PDF). Reports of the National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Kazakhstan. 6 (316): 85–95. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 23, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- Balanovsky O, Rootsi S, Pshenichnov A, Kivisild T, Churnosov M, Evseeva I, Pocheshkhova E, Boldyreva M, et al. (2008). "Two Sources of the Russian Patrilineal Heritage in Their Eurasian Context". American Journal of Human Genetics. 82 (1): 236–250. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.09.019. PMC 2253976. PMID 18179905.

- Балановский, О. П. (November 30, 2015). Генофонд Европы (in Russian). KMK Scientific Press. ISBN 978-5-9907157-0-7. Archived from the original on May 3, 2024. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Battaglia V, Fornarino S, Al-Zahery N, Olivieri A, Pala M, Myres NM, King RJ, Rootsi S, et al. (2008). "Y-chromosomal evidence of the cultural diffusion of agriculture in southeast Europe". European Journal of Human Genetics. 17 (6): 820–30. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2008.249. PMC 2947100. PMID 19107149.

- Behar D, Thomas MG, Skorecki K, Hammer MF, Bulygina E, Rosengarten D, Jones AL, Held K, et al. (2003). "Multiple Origins of Ashkenazi Levites: Y Chromosome Evidence for Both Near Eastern and European Ancestries" (PDF). American Journal of Human Genetics. 73 (4): 768–779. doi:10.1086/378506. PMC 1180600. PMID 13680527. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 17, 2007. Retrieved April 23, 2007.

- Bowden GR, Balaresque P, King TE, Hansen Z, Lee AC, Pergl-Wilson G, Hurley E, Roberts SJ, et al. (2008). "Excavating Past Population Structures by Surname-Based Sampling: The Genetic Legacy of the Vikings in Northwest England". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 25 (2): 301–309. doi:10.1093/molbev/msm255. PMC 2628767. PMID 18032405.

- Brandit, G.; et al. (The Genographic Consortium) (2013). "Ancient DNA Reveals Key Stages in the Formation of Central European Mitochondrial Genetic Diversity". Science. 342 (6155): 257–261. Bibcode:2013Sci...342..257B. doi:10.1126/science.1241844. PMC 4039305. PMID 24115443.

- Capelli C, Redhead N, Abernethy JK, Gratrix F, Wilson JF, Moen T, Hervig T, Richards M, et al. (2003). "A Y Chromosome Census of the British Isles" (PDF). Current Biology. 13 (11): 979–84. Bibcode:2003CBio...13..979C. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00373-7. PMID 12781138. S2CID 526263. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 8, 2021. Retrieved August 8, 2020. also at "University College London" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on January 17, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2007.

- Chunxiang Li; Hongjie Li; Yinqiu Cui; Chengzhi Xie; Dawei Cai; Wenying Li; Victor H Mair; Zhi Xu; et al. (2010). "Evidence that a West-East admixed population lived in the Tarim Basin as early as the early Bronze Age". BMC Biology. 8 (1): 15. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-8-15. PMC 2838831. PMID 20163704.

- Di Cristofaro J, Pennarun E, Mazières S, Myres NM, Lin AA, Temori SA, Metspalu M, Metspalu E, et al. (2013). "Afghan Hindu Kush: Where Eurasian Sub-Continent Gene Flows Converge". PLOS ONE. 8 (10). e76748. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...876748D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0076748. PMC 3799995. PMID 24204668.

- Dupuy BM, Stenersen M, Lu TT, Olaisen B (2005). "Geographical heterogeneity of Y-chromosomal lineages in Norway" (PDF). Forensic Science International. 164 (1): 10–19. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2005.11.009. PMID 16337760. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 22, 2012. Retrieved November 18, 2009.

- Fornarino, Simona; Pala, Maria; Battaglia, Vincenza; Maranta, Ramona; Achilli, Alessandro; Modiano, Guido; Torroni, Antonio; Semino, Ornella; et al. (2009). "Mitochondrial and Y-chromosome diversity of the Tharus (Nepal): a reservoir of genetic variation". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 9 (1): 154. Bibcode:2009BMCEE...9..154F. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-9-154. PMC 2720951. PMID 19573232.

- Fu, Qiaomei; et al. (May 2, 2016). "The genetic history of Ice Age Europe". Nature. 534 (7606): 200–205. Bibcode:2016Natur.534..200F. doi:10.1038/nature17993. hdl:10211.3/198594. PMC 4943878. PMID 27135931.

- Grugni V, Battaglia V, Kashani BH, Parolo S, Al-Zahery N, Achilli A, Olivieri A, Gandini F, Houshmand M, Sanati MH, Torroni A, Semino O (2012). "Ancient Migratory Events in the Middle East: New Clues from the Y-Chromosome Variation of Modern Iranians". PLOS ONE. 7 (7). e41252. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...741252G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041252. PMC 3399854. PMID 22815981.

- Gwozdz (2009). "Y-STR Mountains in Haplospace, Part II: Application to Common Polish Clades" (PDF). Journal of Genetic Genealogy. 5 (2). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved November 28, 2009.

- Haak, W.; Brandt, G.; Jong, H. N. d.; Meyer, C.; Ganslmeier, R.; Heyd, V.; Hawkesworth, C.; Pike, A. W. G.; et al. (2008). "Ancient DNA, Strontium isotopes, and osteological analyses shed light on social and kinship organization of the Later Stone Age". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (47): 18226–18231. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10518226H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0807592105. PMC 2587582. PMID 19015520.

- Haak, Wolfgang; Lazaridis, Iosif; Patterson, Nick; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Llamas, Bastien; Brandt, Guido; Nordenfelt, Susanne; et al. (2015). "Massive migration from the steppe is a source for Indo-European languages in Europe". Nature. 522 (7555): 207–211. arXiv:1502.02783. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..207H. bioRxiv 10.1101/013433. doi:10.1038/NATURE14317. PMC 5048219. PMID 25731166.

- Haber M, Platt DE, Ashrafian Bonab M, Youhanna SC, Soria-Hernanz DF, Martínez-Cruz B, Douaihy B, Ghassibe-Sabbagh M, et al. (2012). "Afghanistan's ethnic groups share a Y-chromosomal heritage structured by historical events". PLOS ONE. 7 (3). e34288. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...734288H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0034288. PMC 3314501. PMID 22470552.

- ISOGG (2012). "Y-DNA Haplogroup O and its Subclades - 2012".

- Karafet, Tatiana M.; Mendez, Fernando L.; Sudoyo, Herawati; Lansing, J. Stephen; Hammer, Michael F. (2014). "Improved phylogenetic resolution and rapid diversification of Y-chromosome haplogroup K-M526 in Southeast Asia". Nature. 23 (3): 369–373. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2014.106. PMC 4326703. PMID 24896152.

- Kasperaviciūte, D.; Kucinskas, V.; Stoneking, M. (2005). "Y Chromosome and Mitochondrial DNA Variation in Lithuanians". Annals of Human Genetics. 68 (5): 438–452. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2003.00119.x. PMID 15469421. S2CID 26562505.

- Kayser M, Lao O, Anslinger K, Augustin C, Bargel G, Edelmann J, Elias S, Heinrich M, et al. (2005). "Significant genetic differentiation between Poland and Germany follows present-day political borders, as revealed by Y-chromosome analysis" (PDF). Human Genetics. 117 (5): 428–443. doi:10.1007/s00439-005-1333-9. PMID 15959808. S2CID 11066186. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2009.

- Keyser, Christine; Bouakaze, Caroline; Crubézy, Eric; Nikolaev, Valery G.; Montagnon, Daniel; Reis, Tatiana; Ludes, Bertrand (2009). "Ancient DNA provides new insights into the history of south Siberian Kurgan people". Human Genetics. 126 (3): 395–410. doi:10.1007/s00439-009-0683-0. PMID 19449030. S2CID 21347353.

- Kim, Kijeong; Brenner, Charles H.; Mair, Victor H.; Lee, Kwang-Ho; Kim, Jae-Hyun; Gelegdorj, Eregzen; Batbold, Natsag; Song, Yi-Chung; et al. (2010). "A western Eurasian male is found in 2000-year-old elite Xiongnu cemetery in Northeast Mongolia". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 142 (3): 429–440. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21242. PMID 20091844.

- Kivisild, T; Rootsi, S; Metspalu, M; Mastana, S; Kaldma, K; Parik, J; Metspalu, E; Adojaan, M; et al. (2003). "The Genetic Heritage of the Earliest Settlers Persists Both in Indian Tribal and Caste Populations". AJHG. 72 (2): 313–32. doi:10.1086/346068. PMC 379225. PMID 12536373.

- Lazaridis, Iosif; et al. (2016). "Genomic insights into the origin of farming in the ancient Near East". Nature. 536 (7617): 419–424. Bibcode:2016Natur.536..419L. doi:10.1038/nature19310. PMC 5003663. PMID 27459054.

- Lell JT, Sukernik RI, Starikovskaya YB, Su B, Jin L, Schurr TG, Underhill PA, Wallace DC (2002). "The Dual Origin and Siberian Affinities of Native American Y Chromosomes" (PDF). American Journal of Human Genetics. 70 (1): 192–206. doi:10.1086/338457. PMC 384887. PMID 11731934. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 22, 2003.

- Liu Shu-hu; Nizam Yilihamu; Rabiyamu Bake; Abdukeram Bupatima; Dolkun Matyusup (2018). "A study of genetic diversity of three isolated populations in Xinjiang using Y-SNP". Acta Anthropologica Sinica. 37 (1): 146–156.

- Carlos Quiles (September 10, 2018). "A study of genetic diversity of three isolated populations in Xinjiang using Y-SNP". Indo-European.eu. Archived from the original on September 20, 2020. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

- Malmström, Helena; Günther, Torsten; Svensson, Emma M.; Juras, Anna; Fraser, Magdalena; Munters, Arielle R.; Pospieszny, Łukasz; Tõrv, Mari; et al. (October 9, 2019). "The genomic ancestry of the Scandinavian Battle Axe Culture people and their relation to the broader Corded Ware horizon". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 286 (1912). doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.1528. PMC 6790770. PMID 31594508.

- Malyarchuk, Boris; Derenko, Miroslava; Wozniak, Marcin; Grzybowski, Tomasz (2013). "Y-chromosome variation in Tajiks and Iranians". Annals of Human Biology. 40 (1): 48–54. doi:10.3109/03014460.2012.747628. PMID 23198991. S2CID 2752490.

- Mascarenhas, Desmond D.; Raina, Anupuma; Aston, Christopher E.; Sanghera, Dharambir K. (2015). "Genetic and Cultural Reconstruction of the Migration of an Ancient Lineage". BioMed Research International. 2015 651415. doi:10.1155/2015/651415. PMC 4605215. PMID 26491681.

- Mathieson, Iain; Lazaridis, Iosif; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Patterson, Nick; Alpaslan Roodenberg, Songul; Harney, Eadaoin; Stewardson, Kristin; et al. (2015). "Eight thousand years of natural selection in Europe". bioRxiv 10.1101/016477.

- Mirabal, Sheyla; Regueiro, M; Cadenas, AM; Cavalli-Sforza, LL; Underhill, PA; Verbenko, DA; Limborska, SA; Herrera, RJ; et al. (2009). "Y-Chromosome distribution within the geo-linguistic landscape of northwestern Russia". European Journal of Human Genetics. 17 (10): 1260–1273. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2009.6. PMC 2986641. PMID 19259129.

- Mohammad T, Xue Y, Evison M, Tyler-Smith C (2009). "Genetic structure of nomadic Bedouin from Kuwait". Heredity. 103 (5): 425–433. doi:10.1038/hdy.2009.72. PMC 2869035. PMID 19639002.

- Narasimhan, Vagheesh M.; Anthony, David; Mallory, James; Reich, David (2018). "The Genomic Formation of South and Central Asia". bioRxiv 10.1101/292581.

- Narasimhan, Vagheesh M.; Patterson, N.J.; Moorjani, Priya; Rohland, Nadin; et al. (2019), "The Formation of Human Populations in South and Central Asia", Science, 365 (6457) eaat7487, doi:10.1126/science.aat7487, PMC 6822619, PMID 31488661

- Nasidze I, Ling EY, Quinque D, Dupanloup I, Cordaux R, Rychkov S, Naumova O, Zhukova O, et al. (2004). "Mitochondrial DNA and Y-Chromosome Variation in the Caucasus" (PDF). Annals of Human Genetics. 68 (Pt 3): 205–221. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2004.00092.x. PMID 15180701. S2CID 27204150. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 30, 2004.

- Nasidze I, Quinque D, Ozturk M, Bendukidze N, Stoneking M (2005). "MtDNA and Y-chromosome Variation in Kurdish Groups" (PDF). Annals of Human Genetics. 69 (Pt 4): 401–412. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2005.00174.x. PMID 15996169. S2CID 23771698. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 23, 2009.

- Pamjav, Horolma; Fehér, Tibor; Németh, Endre; Pádár, Zsolt (2012), "Brief communication: new Y-chromosome binary markers improve phylogenetic resolution within haplogroup R1a1", American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 149 (4): 611–615, doi:10.1002/ajpa.22167, PMID 23115110, S2CID 4820868

- Passarino G, Cavalleri GL, Lin AA, Cavalli-Sforza LL, Børresen-Dale AL, Underhill (2002). "Different genetic components in the Norwegian population revealed by the analysis of mtDNA and Y chromosome polymorphisms". European Journal of Human Genetics. 10 (9): 521–529. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200834. PMID 12173029.