Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

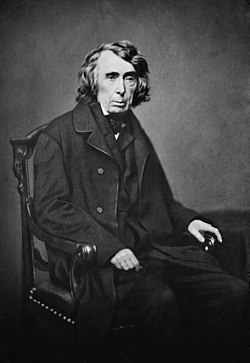

Roger B. Taney

View on Wikipedia

Roger Brooke Taney (/ˈtɔːni/ TAW-nee; March 17, 1777 – October 12, 1864) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the fifth chief justice of the United States, holding that office from 1836 until his death in 1864. Taney delivered the majority opinion in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), ruling that African Americans could not be considered U.S. citizens and that Congress could not prohibit slavery in the U.S. territories. Prior to joining the U.S. Supreme Court, Taney served as the U.S. attorney general and U.S. secretary of the treasury under President Andrew Jackson. He was the first Catholic to serve on the Supreme Court.[1]

Key Information

Taney was born into a wealthy, slave-owning family in Calvert County, Maryland. He won election to the Maryland House of Delegates as a member of the Federalist Party but later broke with the party over the War of 1812. After switching to the Democratic-Republican Party, Taney was elected to the Maryland Senate in 1816. He emerged as one of the most prominent attorneys in the state and was appointed as the Attorney General of Maryland in 1827. Taney supported Andrew Jackson's presidential campaigns in 1824 and 1828, and he became a member of Jackson's Democratic Party. After a cabinet shake-up in 1831, President Jackson appointed Taney as his attorney general. Taney became one of the most important members of Jackson's cabinet and played a major role in the Bank War. Beginning in 1833, Taney served as secretary of the treasury under a recess appointment, but his nomination to that position was rejected by the United States Senate.

In 1835, after Democrats took control of the Senate, Jackson appointed Taney to succeed the late John Marshall on the Supreme Court as Chief Justice. Taney presided over a jurisprudential shift toward states' rights, but the Taney Court did not reject federal authority to the degree that many of Taney's critics had feared. By the early 1850s, he was widely respected, and some elected officials looked to the Supreme Court to settle the national debate over slavery. Despite emancipating his own slaves and giving pensions to those who were too old to work, Taney was outraged by Northern attacks on the institution, and sought to use his Dred Scott decision to permanently end the slavery debate. His broad ruling deeply angered many Northerners and strengthened the anti-slavery Republican Party; its nominee Abraham Lincoln won the 1860 presidential election.

After Lincoln's election, Taney sympathized with the seceding Southern states and blamed Lincoln for the war, but he did not resign from the Supreme Court. He strongly disagreed with President Lincoln's broader interpretation of executive power in the American Civil War. In Ex parte Merryman, Taney held that the president could not suspend the writ of habeas corpus. Lincoln retaliated to the ruling by invoking nonacquiescence. Taney later tried to hold George Cadwalader, one of Lincoln's generals, in contempt of court and the Lincoln Administration again invoked nonacquiescence in response. In 1863, Lincoln delivered the Emancipation Proclamation notwithstanding Taney's rulings on slavery. Taney finally relented, saying: "I have exercised all the power which the Constitution and laws confer on me, but that power has been resisted by a force too strong for me to overcome." Taney died in 1864, and Lincoln appointed Salmon P. Chase as his successor. At the time of Taney's death in 1864, he was widely reviled in the North, and Lincoln declined to make a public statement in response to his death. He continues to have a controversial historical reputation, and his Dred Scott ruling is widely considered to be the worst Supreme Court decision ever made.[2][3][4]

Early life and career

[edit]Taney was born in Calvert County, Maryland, on March 17, 1777, to Michael Taney V and Monica Brooke Taney. Taney's ancestor, Michael Taney I, had settled in Maryland from England in 1660. He and his family established themselves as prominent Catholic landowners of a flourishing tobacco plantation powered by slave labor.[5] As Taney's older brother, Michael Taney VI, was expected to inherit the family's plantation, their father encouraged Roger to study law. At the age of fifteen, Taney was sent to Dickinson College, where he studied ethics, logic, languages, mathematics, and other subjects. After graduating from Dickinson in 1796, he read law under Judge Jeremiah Townley Chase in Annapolis. Taney was admitted to the Maryland bar in 1799.[6] In 1844, Taney was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society.[7]

Marriage and family

[edit]Taney married Anne Phoebe Charlton Key, the sister of Francis Scott Key. They had six daughters together. Though Taney himself remained a Catholic, all of his daughters were raised as members of Anne's Episcopal Church.[8] Taney rented an apartment during his years of service with the federal government, but he and his wife maintained a permanent home in Baltimore. After Anne died in 1855, Taney and two of his unmarried daughters moved permanently to Washington, D.C.[9]

Early political career

[edit]After gaining admission to the state bar, Taney established a successful legal practice in Frederick, Maryland. At his father's urging, he ran for the Maryland House of Delegates as a member of the Federalist Party. With the help of his father, Taney won election to the House of Delegates, but he lost his campaign for a second term. Taney remained a prominent member of the Federalist Party for several years until he broke with the party due to his support of the War of 1812. In 1816, He won election to a five-year term in the Maryland State Senate.[10] In 1823, Taney moved his legal practice to Baltimore, where he gained widespread notoriety as an effective litigator. In 1826, Taney and Daniel Webster represented merchant Solomon Etting in a case that appeared before the Supreme Court of the United States. In 1827, Taney was appointed as the Attorney General of Maryland.[11] Taney supported Andrew Jackson in the 1824 presidential election and the 1828 presidential election. He joined Jackson's Democratic Party and served as a leader of Jackson's 1828 campaign in Maryland.[12]

Taney considered slavery to be an evil practice.[13] He freed the slaves that he inherited from his father early in his life, and as long as they lived, he provided monthly pensions to the older ones who were unable to work.[14] He believed, however, that slavery was a problem to be resolved gradually and chiefly by the states in which it existed,[13] and, as a nationalist, blamed abolitionists for "ripping the country apart".[15] In 1819, nevertheless, Taney defended an abolitionist Methodist minister, Jacob Gruber, who had been arrested for his criticism of slavery. Gruber was charged with attempting to stir up "acts of mutiny and rebellion".[16] Taney claimed that the prosecution lacked a case against Gruber and argued that, lacking evidence of criminal intent, Gruber's freedom of conscience and freedom of speech needed to be protected.[16] Taney delivered "an impassioned defense of Gruber" and, in his opening argument, Taney condemned slavery as "a blot on our national character".[17] After listening to the defense, the jury acquitted Gruber.[16]

Jackson administration

[edit]

Cabinet member

[edit]As a result of the Petticoat Affair, in 1831 President Jackson asked for the resignations of most of the members of his cabinet, including Attorney General John M. Berrien.[18] Jackson turned to Taney to fill the vacancy caused by Berrien's resignation, Taney having been suggested to Jackson by a Washington physician.[19] Taney thus became the president's top legal adviser. In one advisory opinion that he wrote for the president, Taney argued that the protections of the United States Constitution did not apply to free blacks; he would revisit this issue later in his career.[20] Like his predecessors, Taney continued the private practice of law while he served as attorney general, and he served as a counsel for the city of Baltimore in the landmark Supreme Court case of Barron v. Baltimore.[21]

Taney became an important lieutenant in the "Bank War," Jackson's clash with the Second Bank of the United States (or "national bank"). Unlike other members of the cabinet, Taney argued that the national bank was unconstitutional, and that Jackson should seek to abolish it. With Taney's backing, Jackson vetoed a bill to renew the national bank's charter,[22] which was scheduled to expire in 1836.[23] The Bank War became the key issue of the 1832 presidential election, which saw Jackson defeat a challenge from national bank supporter Henry Clay. Taney's unyielding opposition to the bank, combined with Jackson's decisive victory in the election, made the attorney general one of the most prominent members of Jackson's cabinet.[24]

Jackson escalated the Bank War after winning re-election. When Secretary of the Treasury William J. Duane refused to authorize the removal of federal deposits from the national bank, Jackson fired Duane and gave Taney a recess appointment as secretary of the treasury.[25] Taney redistributed federal deposits from the national bank to favored state-chartered banks, which became known as "pet banks".[26] In June 1834, the Senate rejected Taney's nomination as secretary of the treasury, leaving Taney without a position in the cabinet.[27] Taney was the first cabinet nominee in the nation's history to be rejected by the Senate.[28]

Supreme Court nominations

[edit]Despite Taney's earlier rejection by the Senate, in January 1835 Jackson nominated Taney to fill the seat of retiring Supreme Court Associate Justice Gabriel Duvall. Opponents of Taney ensured that his nomination was not voted on before the end of the Senate session, thereby defeating the nomination. The Democrats picked up seats in the 1834 and 1835 Senate elections, giving the party a stronger presence in the chamber. In July 1835, Jackson nominated Taney to succeed Chief Justice John Marshall, who had died earlier in 1835. Though Jackson's opponents in the Whig Party once again attempted to defeat Taney's nomination, Taney won confirmation in March 1836.[29] He was the first Catholic to serve on the Supreme Court.[1]

Taney Court

[edit]Marshall had dominated the Court during his 35 years of service, and his opinion in Marbury v. Madison had helped establish the federal courts as a co-equal branch of government. To the dismay of states' rights advocates, the Marshall Court's rulings in cases such as McCulloch v. Maryland had upheld the power of federal law and institutions over state governments. Many Whigs believed that Taney was a "political hack" and worried about the direction in which he would take the Supreme Court. One of Marshall's key allies, Associate Justice Joseph Story, remained on the Court when Taney took office, but Jackson appointees made up a majority of the Court.[30] Though Taney would preside over a jurisprudential shift toward states' rights, the Taney Court did not reject broad federal authority to the degree that many Whigs initially feared.[31]

1836–1844

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2018) |

Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge presented one of the first major cases of the Taney Court. In 1785, the legislature of Massachusetts had chartered a company to build the Charles River Bridge on the Charles River. In 1828, the state legislature chartered a second company to build a second bridge, the Warren Bridge, just 100 yards away from the Charles River Bridge. The owners of the Charles River Bridge sued, arguing that their charter had given them a monopoly on the operation of bridges in that area of the Charles River. The attorney for the Charles River Bridge, Daniel Webster, argued that the Commonwealth of Massachusetts had violated the Commerce Clause by disregarding the monopoly that the commonwealth had granted to his client. The attorney for Massachusetts, Simon Greenleaf, challenged Webster's interpretation of the charter, noting that the charter did not explicitly grant a monopoly to the proprietors of the Charles River Bridge.[32] In his majority opinion, Taney ruled that the charter did not grant a monopoly to the Charles River Bridge. He held that, while the Contract Clause prevents state legislatures from violating the express provisions of a contract, the Court would interpret a contract provision narrowly when it conflicted with the general welfare of the state. Taney reasoned that any other interpretation would prevent advancements in infrastructure, since the owners of other state charters would demand compensation in return for relinquishing implied monopoly rights.[33]

In Mayor of the City of New York v. Miln (1837), the plaintiffs challenged a New York statute that required masters of incoming ships to report information on all passengers they brought into the country--e.g., age, health, last legal residence. The question before the Taney court was whether or not the state statute undercut Congress's authority to regulate commerce; or was it a police measure, as New York claimed, fully within the authority of the state. Taney and his colleagues sought to devise a more nuanced means of accommodating competing federal and state claims of regulatory power. The Court ruled in favor of New York, holding that the statute did not assume to regulate commerce between the port of New York and foreign ports and because the statute was passed in the exercise of a police power which rightfully belonged to the states.[34]

In Briscoe v. Commonwealth Bank of Kentucky (1837), the third critical ruling of Taney's debut term, the Chief Justice confronted the banking system, in particular state banking. Disgruntled creditors had demanded invalidation of the notes issued by Kentucky's Commonwealth Bank, created during the panic of 1819 to aid economic recovery. The institution had been backed by the credit of the state treasury and the value of unsold public lands, and by every usual measure, its notes were bills of credit of the sort prohibited by the federal Constitution.

Briscoe manifested this change in the field of banking and currency in the first full term of the court's new chief justice. Article I, section 10 of the Constitution prohibited states from using bills of credit, but the precise meaning of a bill of credit remained unclear. In Craig v. Missouri (1830), the Marshall Court had held, by a vote of 4 to 3, that state interest-bearing loan certificates were unconstitutional. However, in the Briscoe case, the Court upheld the issuance of circulating notes by a state-chartered bank even when the Bank's stock, funds, and profits belonged to the state, and where the officers and directors were appointed by the state legislature. The Court narrowly defined a bill of credit as a note issued by the state, on the faith of the state, and designed to circulate as money. Since the notes in question were redeemable by the bank and not by the state itself, they were not bills of credit for constitutional purposes. By validating the constitutionality of state bank notes, the Supreme Court completed the financial revolution triggered by President Andrew Jackson's refusal to recharter the Second Bank of the United States and opened the door to greater state control of banking and currency in the antebellum period.

In the 1839 case of Bank of Augusta v. Earle, Taney joined with seven other justices in voting to reverse a lower court decision that had barred out-of-state corporations from conducting business operations in the state of Alabama.[35] Taney's majority opinion held that out-of-state corporations could do business in Alabama (or any other state) so long as the state legislature did not pass a law explicitly prohibiting such operations.[36]

In Prigg v. Pennsylvania (1842), the Taney Court agreed to hear a case regarding slavery, slaves, slave owners, and states' rights. It held that the Constitutional prohibition against state laws that would emancipate any "person held to service or labor in [another] state" barred Pennsylvania from punishing a Maryland man who had seized a former slave and her child and had taken them back to Maryland without seeking an order from the Pennsylvania courts permitting the abduction. In his opinion for the Court, Justice Joseph Story held not only that states were barred from interfering with enforcement of federal fugitive slave laws, but that they also were barred from assisting in enforcing those laws.

1845–1856

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2018) |

In the 1847 License Cases, Taney developed the concept of police power. He wrote that "whether a state passes a quarantine law, or a law to punish offenses, or to establish courts of justice ... in every case it exercises the same power; that is to say, the power of sovereignty, the power to govern men and things within the limits of its dominion." This broad conception of state power helped to provide a constitutional justification for state governments to take on new responsibilities, such as the construction of internal improvements and the establishment of public schools.[37]

Taney's majority opinion in Luther v. Borden (1849)[38] provided an important rationale for limiting federal judicial power. The Court considered its own authority to issue rulings on matters deemed to be political in nature. Martin Luther, a Dorrite shoemaker, brought suit against Luther Borden, a state militiaman because Luther's house had been ransacked. Luther based his case on the claim that the Dorr government was the legitimate government of Rhode Island, and that Borden's violation of his home constituted a private act lacking legal authority. The circuit court, rejecting this contention, held that no trespass had been committed, and the Supreme Court, in 1849, affirmed. The decision provides the distinction between political questions and justiciable ones. The majority opinion interpreted the Guarantee Clause of the Constitution, Article IV, Section 4. Taney held that under this article Congress is able to decide what government is established in each state. This decision was important as an example of judicial self-restraint. Many Democrats had hoped that the justices would legitimize the actions of the Rhode Island reformers.

Genesee Chief v. Fitzhugh (1852) dealt with the issue of admiralty jurisdiction. This case concerned an 1847 maritime collision on Lake Ontario in which the Genesee Chief's propeller struck and sank the schooner Cuba. Suing under the 1845 act that extended admiralty jurisdiction to the Great Lakes, the owners of the Cuba alleged that the negligence of the Genesee Chief's crew caused the accident. Counsel for the Genesee Chief blamed the Cuba and contended that the incident occurred within New York's waters, outside the reach of federal jurisdiction. The key constitutional question was whether the case properly belonged in the federal courts—specifically, whether admiralty jurisdiction extended to the great freshwater lakes. In England, only tidal rivers had been navigable; hence, in English Law, the Admiralty Courts, which had been given jurisdiction over navigable waters, found their jurisdiction limited to places which felt the effect of the tides of the sea. In the United States, the vast expanse of the Great Lakes and stretches of the continental rivers, extending for hundreds of miles, were not tidal; yet upon these waters large vessels could move, with burdens of passengers and cargo. Taney ruled that the admiralty jurisdiction of the US Courts extends to waters which are actually navigable, without regard to the flow of the ocean tides. Taney's majority opinion established a broad new definition of federal admiralty jurisdiction. According to Taney, the 1845 act fell within Congress's power to control the jurisdiction of the federal courts. "If this law, therefore, is constitutional, it must be supported on the ground that the lakes and navigable waters connecting them are within the scope of admiralty and maritime jurisdiction, as known and understood in the United States when the Constitution was adopted."[39]

The United States increasingly polarized along sectional lines during the 1850s, with slavery acting as the central source of sectional tension.[40] Taney wrote the majority opinion in the 1851 case of Strader v. Graham, in which the Court held that slaves from Kentucky who had conducted a musical performance in the free state of Ohio remained slaves because they had voluntarily returned to Kentucky. Taney's narrowly constructed opinion was joined by both pro-slavery and anti-slavery justices on the Court.[41] While the Court avoided splitting over the issue of slavery, debates over the status of slavery in the territories, as well as the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, continued to roil the nation.[42]

Dred Scott decision

[edit]

As Congress was unable to settle the debate over slavery, some leaders from both the North and the South came to believe that only the Supreme Court could bring an end to the controversy.[43] The Compromise of 1850 contained provisions to expedite appeals regarding slavery in the territories to the Supreme Court, but no suitable case arose until Dred Scott v. Sandford reached the Supreme Court in 1856.[44] In 1846, Dred Scott, an enslaved African American man living in the slave state of Missouri, had filed suit against his master for his own freedom. Scott argued that he had legally gained freedom in the 1830s, when he had resided with a previous master in both the free state of Illinois and a portion of the Louisiana Territory that banned slavery under the Missouri Compromise. Scott prevailed in a state trial court, but that ruling was reversed by the Missouri Supreme Court. After a series of legal maneuvers, the case finally made its way to the Supreme Court in 1856. Although the case concerned the explosive issue of slavery, it initially received relatively little attention from the press and from the justices themselves.[45]

In February 1857, a majority of the judges on the Court voted to deny Scott freedom simply because he had returned to Missouri, thereby reaffirming the precedent set in Strader. However, after two of the Northern justices objected to the decision, Taney and his four Southern colleagues decided to write a much broader decision that would bar federal regulation of slavery in the territories. Like the other Southerners on the Court, Taney was outraged over what he saw as "Northern aggression" towards slavery, an institution that he believed was critical to "Southern life and values".[46] Along with newly elected President James Buchanan, who was aware of the broad outlines of the upcoming decision, Taney and his allies on the Court hoped that the Dred Scott case would permanently remove slavery as a subject of national debate. Reflecting these hopes, Buchanan's March 4, 1857, inaugural address indicated that the issue of slavery would soon be "finally settled" by the Court.[47] To avoid the appearance of sectional favoritism, Taney and his Southern colleagues sought to win the support of at least one Northern justice to the Court's decision. At the request of Associate Justice John Catron, Buchanan convinced Northern Associate Justice Robert Cooper Grier to join the majority opinion in Dred Scott.[46]

The Court's majority opinion, written by Taney, was given on March 6, 1857. He first held that no African American, free or enslaved, had ever enjoyed the rights of a citizen under the Constitution. He argued that, for more than a century leading up to the ratification of the Constitution, blacks had been "regarded as beings of an inferior order, altogether unfit to associate with the white race ... and so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect".[48] To bolster the argument that blacks were widely regarded as legally inferior when the Constitution was adopted, Taney pointed to various state laws, but ignored the fact that five states had allowed blacks to vote in 1788.[49] He next declared that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional, and that the Constitution did not grant Congress the power to bar slavery in the territories. Taney argued that the federal government served as a "trustee" to the people of the territory and could not deprive the right of slaveowners to take slaves into the territories. Only the states, Taney asserted, could bar slavery. Finally, he held that Scott remained a slave.[50]

The Dred Scott opinion received strong criticism in the North, and Associate Justice Benjamin Robbins Curtis resigned in protest.[51] Rather than removing slavery as an issue, it bolstered the popularity of the anti-slavery Republican Party. Republicans like Abraham Lincoln rejected Taney's legal reasoning and argued that the Declaration of Independence showed that the Founding Fathers favored the protection of individual rights for all free men, regardless of race.[52] Many Republicans accused Taney of being part of a conspiracy to legalize slavery throughout the United States.[53]

American Civil War

[edit]

Republican nominee Abraham Lincoln won the 1860 presidential election, defeating Taney's preferred candidate, John C. Breckinridge.[54] Several Southern states seceded in response to Lincoln's election and formed the Confederate States of America; the American Civil War began in April 1861 with the Battle of Fort Sumter.[55] Unlike Associate Justice John Archibald Campbell, Taney (whose home state of Maryland remained in the Union) did not resign from the Court to join the Confederacy, but he believed that the Southern states had the constitutional right to secede, and he blamed Lincoln for starting the war. From his position on the Court, Taney challenged Lincoln's more expansive view of presidential and federal power during the Civil War.[56] He did not get the opportunity to rule against the constitutionality of the Emancipation Proclamation, the Legal Tender Act, or the Enrollment Act, but he did preside over two important Civil War cases.[57]

After secessionists destroyed important bridges and telegraph lines in the border state of Maryland, Lincoln suspended the writ of habeas corpus in much of the state. That suspension allowed military officials to arrest and imprison suspected secessionists for an indefinite period and without a judicial hearing. After the Baltimore riot of 1861, Union officials arrested state legislator John Merryman, whom they suspected of having destroyed Union infrastructure. Union officials allowed Merryman access to his lawyers, who delivered a petition of habeas corpus to the federal circuit court for Maryland. In his role as the head of that circuit court, Taney presided over the case of Ex parte Merryman.[58] Taney held that only Congress had the power to suspend the writ of habeas corpus, and, according to legal scholar James F. Simon, he ordered the release of Merryman.[59] Ultimately however, Taney's final order in Merryman never actually ordered Cadwalader (the actual defendant), the Army, Lincoln or his administration, or anyone else to release John Merryman.[60] Lincoln invoked nonacquiescence in response to Taney's order as well as subsequent Taney orders. On July 4, 1861, in a message to Congress, he argued that the Constitution did in fact give the president the power to suspend the writ of habeas corpus, saying, "Now it is insisted that Congress, and not the Executive, is vested with this power. But the Constitution itself, is silent as to which, or who, is to exercise the power; and as the provision was plainly made for a dangerous emergency, it cannot be believed the framers of the instrument intended, that in every case, the danger should run its course, until Congress could be called together; the very assembling of which might be prevented, as was intended in this case, by the rebellion."[61] Nonetheless, when Lincoln suspended habeas corpus on a far larger scale, he did so only after requesting that Congress authorize him to suspend the writ, which it did by passing the Habeas Corpus Suspension Act of 1863.[62]

In 1863, the Supreme Court heard the Prize Cases, which arose after Union ships blockading the Confederacy seized ships that conducted trade with Confederate ports.[63] An adverse Supreme Court decision would strike a major blow against Lincoln's prosecution of the war, since the blockade cut off the crucial Confederate cotton trade with European countries.[64] The Court's majority opinion, written by Associate Justice Grier, upheld the seizures and ruled that the president had the authority to impose a blockade without a congressional declaration of war. Taney joined a dissenting opinion written by Associate Justice Samuel Nelson, who argued that Lincoln had overstepped his authority by ordering a blockade without the express consent of Congress.[65]

Death

[edit]Taney died on October 12, 1864, at the age of 87,[66] the same day his home state of Maryland passed an amendment abolishing slavery.[67] The following morning, the clerk of the Supreme Court announced that "the great and good Chief Justice is no more." He served as Chief Justice for 28 years, 198 days, the second-longest tenure of any chief justice,[66] and was the oldest-ever serving Chief Justice in United States history.[68] Taney had administered the presidential oath of office to seven incoming presidents. Taney's estate consisted of a $10,000 life insurance policy (equivalent to $200,000 in 2024[69]) and worthless bonds from the commonwealth of Virginia.[70]

President Lincoln made no public statement in response to Taney's death. Lincoln and three members of his cabinet (Secretary of State William H. Seward, Attorney General Edward Bates, and Postmaster General William Dennison) attended Taney's memorial service in Washington. Only Bates joined the cortège to Frederick, Maryland, for Taney's funeral and burial at St. John the Evangelist Cemetery.[71] After Lincoln was re-elected, he appointed Salmon P. Chase, a strongly anti-slavery Republican from Ohio, to succeed Taney.[72]

Legacy

[edit]

Historical reputation

[edit]After his death, Taney remained a controversial figure. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles spoke for many Northerners when he stated that the Dred Scott decision "forfeited respect for [Taney] as a man or a judge".[74] In early 1865, the House of Representatives passed a bill to appropriate funds for a bust of Chief Justice Taney to be displayed in the Supreme Court alongside those of his four predecessors.[75] In response, Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts said:

I speak what cannot be denied when I declare that the opinion of the Chief Justice in the case of Dred Scott was more thoroughly abominable than anything of the kind in the history of courts. Judicial baseness reached its lowest point on that occasion. You have not forgotten that terrible decision where a most unrighteous judgment was sustained by a falsification of history. Of course, the Constitution of the United States and every principle of Liberty was falsified, but historical truth was falsified also.[76][77]

The low point in Taney's reputation came with the 1865 publication of an anonymous sixty-eight-page pamphlet, The Unjust Judge: A Memorial of Roger Brooke Taney.[78] One scholar speculated in 1964 that Sumner was its author.[79]

George Ticknor Curtis, one of the lawyers who argued before Taney on behalf of Dred Scott, held Taney in high esteem despite his decision in Dred Scott. In a volume of memoirs written for his brother Benjamin Robbins Curtis, George Ticknor Curtis gave the following description of Taney:

He was indeed a great magistrate, and a man of singular purity of life and character. That there should have been one mistake in a judicial career so long, so exalted, and so useful is only proof of the imperfection of our nature. The reputation of Chief Justice Taney can afford to have anything known that he ever did and still leave a great fund of honor and praise to illustrate his name. If he had never done anything else that was high, heroic, and important, his noble vindication of the writ of habeas corpus, and of the dignity and authority of his office, against a rash minister of state, who, in the pride of a fancied executive power, came near to the commission of a great crime, will command the admiration and gratitude of every lover of constitutional liberty, so long as our institutions shall endure.[80]

Biographer James F. Simon writes that "Taney's place in history [is] inextricably bound to his disastrous Dred Scott opinion." Simon argues that Taney's opinion in Dred Scott "abandoned the careful, pragmatic approach to constitutional problems that had been the hallmark of [Taney's] early judicial tenure".[81] Historian Daniel Walker Howe writes that "Taney's blend of state sovereignty, white racism, sympathy with commerce, and concern for social order was typical of Jacksonian jurisprudence."[82] Law professor Bernard Schwartz lists Taney as one of the ten greatest Supreme Court justices, writing that "Taney's monumental mistake in Dred Scott should not overshadow his numerous accomplishments on the Court. Taney was second only to Marshall in laying the foundation of our constitutional law."[83] Taney's mixed legacy was noted by Justice Antonin Scalia in his dissenting opinion in Planned Parenthood v. Casey:

There comes vividly to mind a portrait by Emanuel Leutze that hangs in the Harvard Law School: Roger Brooke Taney, painted in 1859, the 82nd year of his life, the 24th of his Chief Justiceship, the second after his opinion in Dred Scott. He is all in black, sitting in a shadowed red armchair, left hand resting upon a pad of paper in his lap, right hand hanging limply, almost lifelessly, beside the inner arm of the chair. He sits facing the viewer, and staring straight out. There seems to be on his face, and in his deep-set eyes, an expression of profound sadness and disillusionment. Perhaps he always looked that way, even when dwelling upon the happiest of thoughts. But those of us who know how the lustre of his great Chief Justiceship came to be eclipsed by Dred Scott cannot help believing that he had that case—its already apparent consequences for the Court and its soon-to-be-played-out consequences for the Nation—burning on his mind.

In this dissent, Scalia contends that his peers on the court are making the same mistake that Taney did in Dred Scott.[84]

It is no more realistic for us in this case, than it was for him in that, to think that an issue of the sort they both involved--an issue involving life and death, freedom and subjugation--can be "speedily and finally settled" by the Supreme Court…

Memorials

[edit]Taney's home, Taney Place, in Calvert County, Maryland, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972. Another property owned by Taney, called the Roger Brooke Taney House (although he never lived there), is in Frederick, Maryland. The House and its associated outbuildings were sold to a private party in 2021.[85] In the past the property was open for tours by appointment and interpreted "the life of Taney and his wife Anne Key (sister of Francis Scott Key), as well as various aspects of life in early nineteenth century Frederick County".[86][87]

Several places and things have been named for Taney, including Taney County, Missouri, the USCGC Taney (WPG-37)[88] (although the ship was later renamed during Taney's de-memorialization),[89] and the Liberty ship SS Roger B. Taney.[90]

De-memorialization due to Dred Scott

[edit]

In 1993, the Roger B. Taney Middle School in Temple Hills, Maryland, was renamed for Justice Thurgood Marshall, the Supreme Court's first African American justice.[91] A statue of Taney formerly stood on the grounds of the Maryland State House, but the state of Maryland removed the statue in 2017,[92] two days after Baltimore mayor Catherine Pugh ordered the removal of its replica in Baltimore City.[73]

In 2020, in the midst of the protests following the murder of George Floyd, the U.S. House of Representatives eventually voted 305–113 to remove a bust of Taney (as well as statues honoring figures who were part of the Confederacy during the Civil War) from the U.S. Capitol and replace it with a bust of Justice Thurgood Marshall, who was a champion of civil rights. The bill called for the removal of Taney's bust within 30 days after the law's passage. The bust had been mounted in the old robing room adjacent to the Old Supreme Court Chamber in the Capitol Building. The bill (H.R. 7573[93]) also created a "process to obtain a bust of Marshall ... and place it there within a minimum of two years".[94] After the bill reached the Republican-led Senate (S.4382), it was referred to the Committee on Rules and Administration, but no further action on it was taken.[95] On June 29, 2021, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a resolution 285 to 120 with sixty-seven Republican Representatives to replace the bust with one of Thurgood Marshall and expel Confederate statues from the U.S. Capitol.[96]

On February 9, 2023, the bust of Roger Taney was officially removed from the United States Capitol Building in Washington, D.C., thanks to an effort led by Maryland Democratic Senators Ben Cardin and Chris Van Hollen, as well as Maryland Democratic Representative Steny Hoyer. The removed statue is to be replaced by a new work of art honoring Justice Thurgood Marshall.[97]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Bunson, Matthew (March 20, 2017). "Catholics and the Supreme Court". National Catholic Register. Archived from the original on November 10, 2018. Retrieved November 8, 2018.

- ^ Hall, Kermit (1992). Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. Oxford University Press. p. 889. ISBN 9780195176612.

American legal and constitutional scholars consider the Dred Scott decision to be the worst ever rendered by the Supreme Court. Historians have abundantly documented its role in crystallizing attitudes that led to war. Taney's opinion stands as a model of censurable judicial craft and failed judicial statesmanship.

- ^ Urofsky, Melvin (January 5, 2023). "Dred Scott decision | Definition, History, Summary, Significance, & Facts | Britannica". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved February 3, 2023.

Among constitutional scholars, Scott v. Sandford is widely considered the worst decision ever rendered by the Supreme Court. It has been cited in particular as the most egregious example in the court's history of wrongly imposing a judicial solution on a political problem. A later chief justice, Charles Evans Hughes, famously characterized the decision as the court's great "self-inflicted wound."

- ^ Staff (October 14, 2015). "13 Worst Supreme Court Decisions of All Time". FindLaw. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- ^ "Roger Brooke Taney". Dickinson College Archives and Special Collections. Retrieved October 29, 2022.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 5–7.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- ^ Simon 2006, p. 8.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 95–97.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 7–9.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Simon 2006, p. 14.

- ^ a b Schumacher, Alvin J. (July 20, 1998). "Roger B. Taney". Encyclopedia Britannica.

Taney, a deeply religious Roman Catholic, considered slavery an evil. He had freed the slaves he had inherited before he came to the Supreme Court. It was his belief, however, that slavery was a problem to be resolved gradually and chiefly by the states in which it existed.

- ^

McNeal, J. P. W. (1913). "Roger Brooke Taney". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company."Early in life he manumitted the slaves inherited from his father, and as long as they lived, he provided for the older ones by monthly pensions".

McNeal, J. P. W. (1913). "Roger Brooke Taney". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company."Early in life he manumitted the slaves inherited from his father, and as long as they lived, he provided for the older ones by monthly pensions".

- ^ Pinkster, Matthew (2020). "Roger Taney, Dickinson and Slavery". Dickinson University. Retrieved October 29, 2022.

Originally from Maryland, Taney had been a slaveholder until he emancipated his own slaves in 1818. But the Border State judge considered himself a nationalist above all else, and angrily blamed abolitionists for ripping the country apart.

- ^ a b c Huebner, Timothy S. (2009). "State v. Gruber (Md., Cty. Ct.) (1819)". The First Amendment Encyclopedia.

- ^ Huebner 2010, pp. 17–38.

- ^ Cole 1993, pp. 84–86.

- ^ Claude G. Bowers, The Party Battles of the Jackson Period, p.129 (Houghton Mifflin Co. 1922) (retrieved Jun. 29, 2024)

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 15–17.

- ^ Howe 2007, p. 441.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Howe 2007, p. 387.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Howe 2007, pp. 392–393.

- ^ Simon 2006, p. 24.

- ^ "Nominations". Washington, D.C.: Office of the Secretary, United States Senate. Archived from the original on April 7, 2019. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 24–26.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 27–29.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 29–32.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Mayor of the City of New York v. Miln, 36 US 102 (1837).

- ^ Huebner 2003, p. 74.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Schwartz 1995, pp. 103–104.

- ^ Luther v. Borden, 48 US 1 (1849).

- ^ The Propeller Genesee Chief v. Fitzhugh, 53 US 443, 453 (1851).

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Simon 2006, p. 94.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 98–100.

- ^ McPherson 2003, p. 172.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 102–105.

- ^ a b McPherson 2003, pp. 171–174

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 117–120.

- ^ Erlich, Walter (2007). They Have No Rights. Applewood Books. pp. 142–143. ISBN 9781557099952.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 121–124.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 124–125.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 125–130.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 155–156.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 168–171, 177.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 171–172, 182.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 194–195, 220–221.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 222–223, 245.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 183–187.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 189–192.

- ^ Ex parte Merryman, 17 F. Cas. 144, 152 (C.C.D. Md. 1861).

- ^ Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, vol. 4, pp. 430-431.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 195–197.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 205–207.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 225–226.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 229–232.

- ^ a b "Roger Brooke Taney, 1836-1864". Washington, D.C.: Supreme Court Historical Society. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved January 16, 2018.

- ^ Shaffer, Donald R. (November 1, 2014). "Slavery Ends in Maryland: November 1, 1864". Archived from the original on October 5, 2019. Retrieved October 5, 2019.

- ^ Damon, Allan L. "A look at the Record - The Supreme Court". www.americanheritage.com. American Heritage. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Simon 2006, p. 269.

- ^ Christensen, George A. (1983). "Here Lies the Supreme Court: Gravesites of the Justices". Supreme Court Historical Society. Archived from the original on September 3, 2005.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 267–268.

- ^ a b Nirappil, Fenit (August 16, 2017). "Baltimore hauls away four Confederate monuments after overnight removal". Maryland Politics. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 17, 2017. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ^ Simon 2006, p. 266.

- ^ "Art and History: Roger B. Taney". United States Senate. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved February 16, 2018.

- ^ Konig, David Thomas; Finkelman, Paul; Bracey, Christopher Alan (2014). The Dred Scott Case: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Race and Law. Ohio University Press. p. 228. ISBN 9780821443286.

- ^ Simon 2006, p. 268.

- ^ Huebner, Timothy S. (2015). ""The Unjust Judge": Roger B. Taney, the Slave Power, and the Meaning of Emancipation". Journal of Supreme Court History. 40 (3): 249–262. doi:10.1111/jsch.12081. S2CID 143192028., quotation on p. 257.

- ^ Lewis, Walker (October 1964). "The Unjust Judge: Who Wrote It?". American Bar Association Journal. 50 (10): 932–937. JSTOR 25722968.

- ^ Curtis, Benjamin R., ed. (2002) [1879]. A Memoir of Benjamin Robbins Curtis, LL.D. with some of his Professional and Miscellaneous Writings, Vol. I. The Lawbook Exchange. pp. 239–240. ISBN 1-58477-235-2. Archived from the original on November 8, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2016.

- ^ Simon 2006, pp. 270–271.

- ^ Howe 2007, p. 445.

- ^ Schwartz 1995, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Scalia (June 29, 1992), Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania, Et Al., Petitioners 91-744 v. Robert P. Casey, Et Al., Etc. Robert P. Casey, Et Al., Etc., Petitioners 91-902, retrieved March 26, 2025

- ^ "121 S Bentz Street, Frederick, MD 21701 | MLS MDFR277060 | Listing Information | Long & Foster". Archived from the original on May 9, 2021. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ "Roger Brooke Taney House". VisitFrederick. Archived from the original on April 2, 2019. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

The site, including the family's living quarters, a summer kitchen and slaves' quarters, interprets the life of Taney and various aspects of middle class life in early nineteenth century Frederick County. The Roger Brooke Taney House is not open to the public. The exterior can be viewed from the street, but visitors will not be able to enter the house. Groups may contact Heritage Frederick for tours by appointment.

- ^ "Roger Brooke Taney House : General Information". Historical Society of Frederick County. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved January 23, 2016.

- ^ "Taney II (Coast Guard Cutter No. 68)". Naval History and Heritage Command. United States Navy. Archived from the original on November 10, 2018. Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- ^ Kesling, Ben (July 2020). "Historic Coast Guard Ship 'Taney' to Be Renamed". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on July 24, 2020. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

- ^ Maryland in World War II.: Military participation. Maryland Historical Society. 1950. p. 360.

- ^ Leff, Lisa (March 5, 1993). "P.G. County Replaces Taney With Marshall". Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 17, 2018. Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- ^ Witte, Brian (August 18, 2017). "Maryland removes Dred Scott ruling author's statue". Associated Press. Archived from the original on August 18, 2017. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- ^ "H.R.7573 - To direct the Joint Committee on the Library to replace the bust of Roger Brooke Taney in the Old Supreme Court Chamber of the United States Capitol with a bust of Thurgood Marshall to be obtained by the Joint Committee on the Library and to remove certain statues from areas of the United States Capitol which are accessible to the public, to remove all statues of individuals who voluntarily served the Confederate States of America from display in the United States Capitol, and for other purposes". United States Congress. July 22, 2020. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- ^ Walsh, Deirdre (July 22, 2020). "House Passes Bill Removing Confederate Statues, Other Figures From Capitol". NPR. Archived from the original on July 23, 2020. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- ^ "S. 4382: A bill to direct the Joint Committee on the Library to replace the bust of Roger Brooke Taney in the Old Supreme Court Chamber of the Capitol with a bust of Thurgood Marshall to be obtained by the Joint Committee on the Library and to remove certain statues from areas of the Capitol which are accessible to the public, to remove all statues of individuals who voluntarily served the Confederate States of America from display in the Capitol, and for other purposes". govtrack.us. July 30, 2020. Archived from the original on February 2, 2021. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- ^ Alex Rogers (June 29, 2021). "House votes to remove Confederate statues". CNN. Archived from the original on June 30, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ State of Notorious Dred Scott Justice removed from Capitol

Bibliography

[edit]- Abraham, Henry J. (1992). Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506557-3.

- Allen, Austin (2010). Origins of the Dred Scott Case: Jacksonian Jurisprudence and the Supreme Court, 1837–1857. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 9780820336640.

- Cole, Donald B. (1993). The Presidency of Andrew Jackson. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0600-9.

- Cushman, Clare (2001). The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–1995 (2nd ed.). (Supreme Court Historical Society, Congressional Quarterly Books). ISBN 1-56802-126-7.

- Finkelman, Paul (2018). Supreme Injustice: Slavery in the Nation's Highest Court. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674051218.

- Flanders, Henry (1874). The Lives and Times of the Chief Justices of the United States Supreme Court. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co.

- Frank, John P. (1995). Friedman, Leon; Israel, Fred L. (eds.). The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0-7910-1377-4.

- Hall, Kermit L., ed. (1992). The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505835-6.

- Howe, Daniel Walker (2007). What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507894-7.

- Huebner, Timothy S. (2003). The Taney Court, Justice Rulings and Legacy. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-Clio. ISBN 1-57607-368-8.

- ——— (2010). "Roger Taney and the Slavery Issue: Looking Beyond—and Before—Dred Scott". Journal of American History. 97 (1): 39–62. doi:10.2307/jahist/97.1.17. JSTOR 40662816.

- Kahan, Paul (2016). The Bank War: Andrew Jackson, Nicholas Biddle, and the Fight for American Finance. Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing. pp. 83–130. ISBN 978-1594162343.

- Lewis, Walker (1965). Without Fear or Favor: A Biography of Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney. Houghton Mifflin. ASIN B0006D6Y2E.

- McPherson, James M. (2003). Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (Illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199743902.

- Remini, Robert V. (1967). Andrew Jackson and the Bank War. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 111–172. ISBN 978-0393097573.

- Schwartz, Bernard (1995). "Supreme Court Superstars: The Ten Greatest Justices". Tulsa Law Review. 31 (1): 93–159. Archived from the original on November 10, 2018. Retrieved November 9, 2018.

- Simon, James F. (2006). Lincoln and Chief Justice Taney: Slavery, Secession, and the President's War Powers. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-5032-0.

- Swisher, Carl B. (1935). Roger B. Taney. Macmillan. OCLC 71254704.

- Urofsky, Melvin I. (1994). The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. New York: Garland Publishing. p. 590. ISBN 0-8153-1176-1.

- VanBurkleo, Sandra F.; Speck, Bonnie (2000). Taney, Roger Brooke. doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1100834. ISBN 978-0-19-860669-7. Archived from the original on November 10, 2018. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help)

Further reading

[edit]- Ellis, Charles M. (February 1865). "Roger B. Taney and the Leviathan of Slavery". The Atlantic.

Falsifying history; setting above the Constitution the most odious theory of tyranny, long before exploded; scoffing at the rules of justice and sentiments of humanity, he tied in a knot those cords which must end the life of his country or be burst in revolution.

External links

[edit]- Roger Brooke Taney at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- Anne Key, Wife Of Chief Justice Roger B. Taney

- Biography from FindLaw.

- Fox, John, Capitalism and Conflict, Biographies of the Robes, Roger Taney. Public Broadcasting Service.

- Oyez.org Supreme Court media on Roger B. Taney.

- Roger Brooke Taney Home/Museum in Frederick, MD.

- The Unjust Judge digitized copy from Cornell University

Roger B. Taney

View on GrokipediaRoger Brooke Taney (March 17, 1777 – October 12, 1864) was an American lawyer, politician, and jurist who served as the fifth Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court from 1836 to 1864, the second-longest tenure in the Court's history.[1][2] A native of Calvert County, Maryland, born to a prosperous Catholic tobacco-planting family, Taney graduated from Dickinson College in 1795, was admitted to the bar in 1799, and built a successful legal practice while entering politics as a Federalist before aligning with Andrew Jackson's Democrats.[2][3] Appointed U.S. Attorney General in 1831, he advised Jackson during the Bank War and briefly served as Secretary of the Treasury in 1833–1834 via recess appointment, implementing policies to dismantle the Second Bank of the United States before Senate rejection prompted his return to Attorney General.[4][2] Nominated by Jackson to succeed Chief Justice John Marshall, Taney faced initial Senate rejection amid anti-Catholic and anti-Jackson sentiment but was confirmed in 1836 as the first Catholic Chief Justice.[1] His Court emphasized states' rights, contractual freedoms in cases like Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge (1837), and federal limits, but Taney's legacy is dominated by the 1857 Dred Scott v. Sandford decision, where he authored the majority opinion declaring African Americans ineligible for citizenship, voiding congressional power to prohibit slavery in territories under the Missouri Compromise, and affirming slavery as constitutionally protected property in states—positions rooted in his view of the framers' original intent despite his personal emancipation of inherited slaves around 1819.[5][6] A slaveholder by inheritance who freed his own bondspeople amid economic pressures rather than abolitionist conviction, Taney defended slavery's legality while rejecting federal interference, contributing to sectional tensions culminating in the Civil War; he administered Abraham Lincoln's oath in 1861 but clashed with Union policies, notably dissenting in the Merryman habeas case.[6][7]