Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

The Simpsons

View on Wikipedia

| The Simpsons | |

|---|---|

| |

| Genre | |

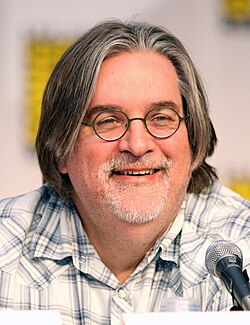

| Created by | Matt Groening |

| Developed by |

|

| Showrunners |

|

| Written by | List of writers |

| Directed by | List of directors |

| Voices of | |

| Theme music composer | Danny Elfman |

| Opening theme | "The Simpsons Theme" |

| Ending theme | "The Simpsons Theme" (reprise) |

| Composers | |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Original language | English |

| No. of seasons | 37 |

| No. of episodes | 794 (list of episodes) |

| Production | |

| Executive producer | Various

|

| Producers |

|

| Editors |

|

| Running time | 21–24 minutes |

| Production companies |

|

| Original release | |

| Network | Fox Disney+ (from 2024, specials) |

| Release | December 17, 1989 – present |

The Simpsons is an American animated sitcom created by Matt Groening and developed by Groening, James L. Brooks and Sam Simon for the Fox Broadcasting Company. It is a satirical depiction of American life, epitomized by the Simpson family, which consists of Homer, Marge, Bart, Lisa, and Maggie. Set in the fictional town of Springfield, in an unspecified location in the United States, it caricatures society, Western culture, television and the human condition.

The family was conceived by Groening shortly before a solicitation for a series of animated shorts with producer Brooks. He created a dysfunctional family and named the characters after his own family members, substituting Bart for his own name; he thought Simpson was a funny name in that it sounded similar to "simpleton".[1] The shorts became a part of The Tracey Ullman Show on April 19, 1987. After three seasons, the sketch was developed into a half-hour prime time show and became Fox's first series to land in the Top 30 ratings in a season (1989–1990).

Since its debut on December 17, 1989, 794 episodes of the show have been broadcast. It is the longest-running American animated series, longest-running American sitcom, and the longest-running American scripted primetime television series, both in seasons and individual episodes. A feature-length film, The Simpsons Movie, was released in theaters worldwide on July 27, 2007, to critical and commercial success, with a sequel in development with a release date of July 2027. The series has also spawned numerous comic book series, video games, books and other related media, as well as a billion-dollar merchandising industry. The Simpsons was initially a joint production by Gracie Films and 20th Television; 20th Television's involvement was later moved to 20th Television Animation, a separate unit of Disney Television Studios.[2] On April 2, 2025, the show was renewed for four additional seasons on Fox, with 15 episodes each.

The Simpsons received widespread acclaim throughout its early seasons in the 1990s, which are generally considered its "golden age". Since then, it has been criticized for a perceived decline in quality. Time named it the 20th century's best television series,[3] and Erik Adams of The A.V. Club named it "television's crowning achievement regardless of format".[4] On January 14, 2000, the Simpson family was awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. It has won dozens of awards since it debuted as a series, including 37 Primetime Emmy Awards, 34 Annie Awards, and 2 Peabody Awards. Homer's exclamatory catchphrase of "D'oh!" has been adopted into the English language, while The Simpsons has influenced many other later adult-oriented animated sitcom television series.

Premise

[edit]Characters

[edit]The main characters are the Simpson family, who live in the fictional "Middle America" town of Springfield.[5] Homer, the father, works as a safety inspector at the Springfield Nuclear Power Plant, a position at odds with his careless, buffoonish personality. He is married to Marge (née Bouvier), a stereotypical American housewife and mother. They have three children: Bart, a ten-year-old troublemaker and prankster; Lisa, a precocious eight-year-old activist; and Maggie (named by Bart),[6] the baby of the family who rarely speaks, but communicates by sucking on a pacifier. Although the family is dysfunctional, many episodes examine their relationships and bonds with each other and they are often shown to care about one another.[7]

The family also owns a greyhound, Santa's Little Helper, (who first appeared in the episode "Simpsons Roasting on an Open Fire") and a cat, Snowball II, who is replaced by a cat, also named Snowball II, in the fifteenth-season episode "I, (Annoyed Grunt)-Bot".[8] Extended members of the Simpson and Bouvier family in the main cast include Homer's father Abe and Marge's sisters Patty and Selma. Marge's mother Jacqueline and Homer's mother Mona appear less frequently.

-

The Simpsons sports a vast array of secondary and tertiary characters.

The show includes a vast array of quirky supporting characters, which include Homer's friends Barney Gumble, Lenny Leonard, and Carl Carlson; the school principal Seymour Skinner and staff members such as Edna Krabappel and Groundskeeper Willie; students such as Milhouse Van Houten, Nelson Muntz, and Ralph Wiggum; shopkeepers such as Apu Nahasapeemapetilon, Comic Book Guy, and Moe Szyslak; government figures Mayor "Diamond" Joe Quimby and Clancy Wiggum; next-door neighbor Ned Flanders; local celebrities such as Krusty the Clown and news reporter Kent Brockman; nuclear tycoon Montgomery Burns and his devoted assistant Waylon Smithers; and many more.

The creators originally intended many of these characters as one-time jokes or for fulfilling needed functions in the town. A number of them have gained expanded roles and subsequently starred in their own episodes. According to Matt Groening, the show adopted the concept of a large supporting cast from the comedy show SCTV.[9]

Continuity and the floating timeline

[edit]Despite the depiction of yearly milestones such as holidays or birthdays passing, the characters never age. The series uses a floating timeline in which episodes generally take place in the year the episode is produced. Flashbacks and flashforwards do occasionally depict the characters at other points in their lives, with the timeline of these depictions also generally floating relative to the year the episode is produced. For example, the 1991 episodes "The Way We Was" and "I Married Marge" depict Homer and Marge as high schoolers in the 1970s who had Bart (who is always 10 years old) in the early '80s, while the 2008 episode "That '90s Show" depicts Homer and Marge as a childless couple in the '90s, and the 2021 episode "Do Pizza Bots Dream of Electric Guitars" portrays Homer as an adolescent in the same period. The 1995 episode "Lisa's Wedding" takes place during Lisa's college years in the then-future year of 2010, the same year the show began airing its 22nd season, in which Lisa was still 8. In 2015, the show reached the point where, had the characters been allowed to age in real time, Bart would have been older than Homer was in the first episode. Regarding the contradictory flashbacks, Selman stated that "they all kind of happened in their imaginary world".[10]

The show follows a loose and inconsistent continuity. For example, Krusty the Clown may be able to read in one episode, but not in another. However, it is consistently portrayed that he is Jewish, that his father was a rabbi, and that his career began in the 1960s. The latter point introduces another snag in the floating timeline: historical periods that are a core part of a character's backstory remain so even when their age makes it unlikely or impossible, such as Grampa Simpson and Principal Skinner's respective service in World War II and Vietnam.

The only episodes not part of the series' main canon are the Treehouse of Horror episodes, which often feature the deaths of main characters. Characters who die in "regular" episodes, such as Maude Flanders, Mona Simpson, Edna Krabappel, etc, however, stay dead. An exception to this is Hans Moleman, who is often killed in his appearances – as of 2019[update] he has been killed 26 times only to reappear later.[11] Most episodes end with the status quo being restored, though occasionally major changes will stick, such as Lisa's conversions to vegetarianism and Buddhism, the divorce of Milhouse van Houten's parents, and the marriage and subsequent parenthood of Apu and Manjula.

Setting

[edit]The Simpsons takes place in a fictional American town called Springfield. Although there are many real settlements in America named Springfield,[12] the town the show is set in is fictional. The state it is in is not established. In fact, the show is intentionally evasive with regard to Springfield's location.[13] Springfield's geography and that of its surroundings is inconsistent: from one episode to another, it may have coastlines, deserts, vast farmland, mountains, or whatever the story or joke requires.[14] Groening has said that Springfield has much in common with Portland, Oregon, the city where he grew up.[15] Groening has said that he named it after Springfield, Oregon, and the fictitious Springfield which was the setting of the series Father Knows Best. He "figured out that Springfield was one of the most common names for a city in the U.S. In anticipation of the success of the show, I thought, 'This will be cool; everyone will think it's their Springfield.' And they do."[16] Many landmarks, including street names, have connections to Portland.[17]

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]When producer James L. Brooks was working on the television variety show The Tracey Ullman Show, he decided to include small animated sketches before and after the commercial breaks. Having seen one of cartoonist Matt Groening's Life in Hell comic strips, Brooks asked Groening to pitch an idea for a series of animated shorts. Groening initially intended to present an animated version of his Life in Hell series.[18] However, Groening later realized that animating Life in Hell would require the rescinding of publication rights for his life's work. He therefore chose another approach while waiting in the lobby of Brooks's office for the pitch meeting, hurriedly formulating his version of a dysfunctional family that became the Simpsons.[18][19] He named the characters after his own family members, substituting "Bart" for his own name, adopting an anagram of the word "brat".[18]

The Simpson family first appeared as shorts in The Tracey Ullman Show on April 19, 1987.[20] Groening submitted only basic sketches to the animators and assumed that the figures would be cleaned up in production. However, the animators merely re-traced his drawings, which led to the crude appearance of the characters in the initial shorts.[18] The animation was produced domestically at Klasky Csupo,[21][22] with Wes Archer, David Silverman, and Bill Kopp being animators for the first season.[23] The colorist, "Georgie" Gyorgyi Kovacs Peluce (Kovács Györgyike)[24][25][26][27][28][29] made the characters yellow; as Bart, Lisa, and Maggie have no hairlines, she felt they would look strange if they were flesh-colored. Groening supported the decision, saying: "Marge is yellow with blue hair? That's hilarious — let's do it!"[23]

In 1989, a team of production companies adapted The Simpsons into a half-hour series for the Fox Broadcasting Company. The team included the Klasky Csupo animation house. Brooks negotiated a provision in the contract with the Fox network that prevented Fox from interfering with the show's content.[30] Groening said his goal in creating the show was to offer the audience an alternative to what he called "the mainstream trash" that they were watching.[31] The half-hour series premiered on December 17, 1989, with "Simpsons Roasting on an Open Fire".[32] "Some Enchanted Evening" was the first full-length episode produced, but it did not broadcast until May 1990, as the last episode of the first season, because of animation problems.[33] In 1992, Tracey Ullman filed a lawsuit against Fox, claiming that her show was the source of the series' success. The suit said she should receive a share of the profits of The Simpsons[34]—a claim rejected by the courts.[35]

Executive producers and showrunners

[edit]List of showrunners throughout the series' run:

- Season 1–2: Matt Groening, James L. Brooks, & Sam Simon

- Season 3–4: Al Jean & Mike Reiss

- Season 5–6: David Mirkin

- Season 7–8: Bill Oakley & Josh Weinstein

- Season 9–12: Mike Scully

- Season 13–31: Al Jean

- Season 32–35: Al Jean & Matt Selman

- Season 36–present: Matt Selman

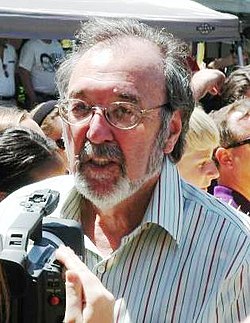

Matt Groening and James L. Brooks have served as executive producers during the show's entire history, and also function as creative consultants. Sam Simon, described by former Simpsons director Brad Bird as "the unsung hero" of the show,[36] served as creative supervisor for the first four seasons. He was constantly at odds with Groening, Brooks and the show's production company Gracie Films and left in 1993.[37] Before leaving, he negotiated a deal that sees him receive a share of the profits every year, and an executive producer credit despite not having worked on the show since 1993,[37][38] at least until his death in 2015.[39] A more involved position on the show is the showrunner, who acts as head writer and manages the show's production for an entire season.[23]

Writing

[edit]

The first team of writers, assembled by Sam Simon, consisted of John Swartzwelder, Jon Vitti, George Meyer, Jeff Martin, Al Jean, Mike Reiss, Jay Kogen, and Wallace Wolodarsky.[40] Newer Simpsons' writing teams typically consist of sixteen writers who propose episode ideas at the beginning of each December.[41] The main writer of each episode writes the first draft. Group rewriting sessions develop final scripts by adding or removing jokes, inserting scenes, and calling for re-readings of lines by the show's vocal performers.[42] Until 2004,[43] George Meyer, who had developed the show since the first season, was active in these sessions. According to long-time writer Jon Vitti, Meyer usually invented the best lines in a given episode, even though other writers may receive script credits.[42] Each episode takes approximately six months to produce, so the show rarely comments on current events.[44]

Credited with sixty episodes, John Swartzwelder is the most prolific writer on The Simpsons.[45] One of the best-known former writers is Conan O'Brien, who contributed to several episodes in the early 1990s before replacing David Letterman as host of the talk show Late Night.[46] English comedian Ricky Gervais wrote the episode "Homer Simpson, This Is Your Wife", becoming the first celebrity both to write and guest star in the same episode.[47] Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg, writers of the film Superbad, wrote the episode "Homer the Whopper", with Rogen voicing a character in it.[48]

At the end of 2007, the writers of The Simpsons went on strike together with the other members of the Writers Guild of America, East. The show's writers had joined the guild in 1998.[49]

In May 2023, the writers of The Simpsons went on strike together with the other members of the Writers Guild of America, East.[50][51]

Voice actors

[edit]| Cast members | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||

| Dan Castellaneta | Julie Kavner | Nancy Cartwright | Yeardley Smith | Hank Azaria | Harry Shearer | |||

| Homer Simpson, Abe Simpson, Krusty the Clown, various characters | Marge Simpson, Patty and Selma Bouvier, additional voices | Bart Simpson, Maggie Simpson, Nelson Muntz, various characters | Lisa Simpson | Moe Szyslak, Chief Wiggum, Apu Nahasapeemapetilon (1990–2020), Lou (1990–2020), various characters | Ned Flanders, Mr. Burns, Dr. Hibbert (1990–2021), Waylon Smithers, Principal Skinner, Reverend Lovejoy, various characters | |||

The Simpsons has six main cast members: Dan Castellaneta, Julie Kavner, Nancy Cartwright, Yeardley Smith, Hank Azaria, and Harry Shearer. Castellaneta voices Homer Simpson, Grampa Simpson, Krusty the Clown, Groundskeeper Willie, Mayor Quimby, Barney Gumble, and other adult male characters.[52] Julie Kavner voices Marge Simpson, Patty, Selma, as well as several minor characters.[52] Castellaneta and Kavner had been a part of The Tracey Ullman Show cast and were given the parts so that new actors would not be needed.[53] Cartwright voices Bart Simpson, Maggie Simpson, Nelson Muntz, Ralph Wiggum, and other children.[52] Smith, the voice of Lisa Simpson, is the only cast member who regularly voices only one character, although she occasionally plays other episodic characters.[52] The producers decided to hold casting for the roles of Bart and Lisa. Smith had initially been asked to audition for the role of Bart, but casting director Bonita Pietila believed her voice was too high,[54] so she was given the role of Lisa instead.[55] Cartwright was originally brought in to voice Lisa, but upon arriving at the audition, she found that Lisa was simply described as the "middle child" and at the time did not have much personality. Cartwright became more interested in the role of Bart, who was described as "devious, underachieving, school-hating, irreverent, [and] clever".[56] Groening let her try out for the part instead, and upon hearing her read, gave her the job on the spot.[57] Cartwright is the only one of the six main Simpsons cast members who had been professionally trained in voice acting prior to working on the show.[45] Azaria and Shearer do not voice members of the title family, but play a majority of the male townspeople. Azaria, who has been a part of the main voice cast since the second season in one episode "Old Money" and then perpetually part of the regular main voice cast since the third season, voices recurring characters such as Moe Szyslak, Chief Wiggum, Apu Nahasapeemapetilon, and Professor Frink. Shearer provides voices for Mr. Burns, Mr. Smithers, Principal Skinner, Ned Flanders, Reverend Lovejoy, and formerly Dr. Hibbert.[52] Every main cast member has won a Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Voice-Over Performance.[58][59]

With one exception, episode credits list only the voice actors, and not the characters they voice. Both Fox and the production crew wanted to keep their identities secret during the early seasons and, therefore, closed most of the recording sessions while refusing to publish photos of the recording artists.[60] However, the network eventually revealed which roles each actor performed in the episode "Old Money", because the producers said the voice actors should receive credit for their work.[61] In 2003, the cast appeared in an episode of Inside the Actors Studio, doing live performances of their characters' voices.

The six main actors were paid $30,000 per episode, until 1998, when they were involved in a pay dispute with Fox. The company threatened to replace them with new actors, even going as far as preparing for casting of new voices, but series creator Groening supported the actors in their action.[62] The issue was soon resolved and, from 1998 to 2004, they were paid $125,000 per episode. The show's revenue continued to rise through syndication and DVD sales, and in April 2004 the main cast stopped appearing for script readings, demanding they be paid $360,000 per episode.[63][64] The strike was resolved a month later[65] and their salaries were increased to between $250,000[66] and $360,000 per episode.[67] In 2008, production for the twentieth season was put on hold due to new contract negotiations with the voice actors, who wanted a "healthy bump" in salary to an amount close to $500,000 per episode.[67] The negotiations were soon completed, and the actors' salary was raised to $400,000 per episode.[68] Three years later, with Fox threatening to cancel the series unless production costs were cut, the cast members accepted a 30 percent pay cut, down to just over $300,000 per episode.[69]

In addition to the main cast, Pamela Hayden, Tress MacNeille, Marcia Wallace, Maggie Roswell, and Russi Taylor voice supporting characters.[52] From 1999 to 2002, Roswell's characters were voiced by Marcia Mitzman Gaven. Karl Wiedergott has also appeared in minor roles, but does not voice any recurring characters.[70] Wiedergott left the show in 2010, and since then Chris Edgerly has appeared regularly to voice minor characters. Repeat "special guest" cast members include Albert Brooks, Phil Hartman, Jon Lovitz, Joe Mantegna, Maurice LaMarche, and Kelsey Grammer.[71] Following Hartman's death in 1998, the characters he voiced (Troy McClure and Lionel Hutz) were retired;[72] Wallace's character of Edna Krabappel was retired as well after her death in 2013. Following Taylor's death in 2019, her characters (including Sherri, Terri, and Martin Prince) are now voiced by Grey Griffin.[73]

Episodes will quite often feature guest voices from a wide range of professions, including actors, athletes, authors, bands, musicians and scientists. In the earlier seasons, most of the guest stars voiced characters, but eventually more started appearing as themselves. Tony Bennett was the first guest star to appear as himself, appearing briefly in the season two episode "Dancin' Homer".[74] The Simpsons holds the world record for "Most Guest Stars Featured in a Television Series".[75]

The Simpsons has been dubbed into several other languages, including Japanese, German, Spanish, Portuguese and Italian. It is also one of the few programs dubbed in both standard French and Quebec French.[76] The show has been broadcast in Arabic, but due to Islamic customs, numerous aspects of the show have been changed. For example, Homer drinks soda instead of beer and eats Egyptian beef sausages instead of hot dogs. Because of such changes, the Arabized version of the series met with a negative reaction from the lifelong Simpsons fans in the area.[77]

Animation

[edit]

Several different American and international studios animate The Simpsons. Throughout the run of the animated shorts on The Tracey Ullman Show, the animation was produced domestically at Klasky Csupo.[21] With the debut of the series, because of an increased workload, Fox subcontracted production to several local and foreign studios.[21] These are AKOM,[78] Anivision,[79] Rough Draft Studios,[80] USAnimation,[81] and Toonzone Entertainment.[82]

For the first three seasons, Klasky Csupo animated The Simpsons in the United States. In 1992, the show's production company, Gracie Films, switched domestic production to Film Roman,[83] who continued to animate the show until 2016 when they were replaced by Fox Television Animation, which allowed the show to be made more in-house. In the first episode of Season 14, production switched from traditional cel animation to digital ink and paint.[84] The first episode to experiment with digital coloring was "Radioactive Man" in 1995. Animators used digital ink and paint during production of the season 12 episode "Tennis the Menace", but Gracie Films delayed the regular use of digital ink and paint until two seasons later. The already completed "Tennis the Menace" was broadcast as made.[85]

The production staff at the American animation studio, Film Roman, draws storyboards, designs new characters, backgrounds, props and draws character and background layouts, which in turn become animatics to be screened for the writers at Gracie Films for any changes to be made before the work is shipped overseas. The overseas studios then draw the inbetweens, ink and paint, and render the animation to tape before it is shipped back to the United States to be delivered to Fox three to four months later.[86]

The series began high-definition production in season 20; the first episode, "Take My Life, Please", aired February 15, 2009. The move to HDTV included a new opening sequence.[87] Matt Groening called it a complicated change because it affected the timing and composition of animation.[88]

Themes

[edit]The Simpsons uses the standard setup of a situational comedy, or sitcom, as its premise. The series centers on a family and their life in a typical American town,[5] serving as a satirical parody of a middle class American lifestyle.[89] However, because of its animated nature, The Simpsons' scope is larger than that of a regular sitcom. The town of Springfield acts as a complete universe in which characters can explore the issues faced by modern society. By having Homer work in a nuclear power plant, the show can comment on the state of the environment.[90] Through Bart and Lisa's days at Springfield Elementary School, the show's writers illustrate pressing or controversial issues in the field of education. The town features a vast array of television channels, which enables the producers to make jokes about the entertainment industry and the press.[91]

Some commentators say the show is political in nature and susceptible to a left-wing bias.[92] Al Jean acknowledged in an interview that "We [the show] are of liberal bent."[93] The writers often evince an appreciation for progressive leanings, but the show makes jokes across the political spectrum.[94] The show portrays government and large corporations as evil entities that take advantage of the common worker.[93] Thus, the writers often portray authority figures in an unflattering or negative light. In The Simpsons, politicians are corrupt, ministers such as Reverend Lovejoy are dismissive to churchgoers, and the local police force is incompetent.[95] Religion also figures as a recurring theme.[96] In times of crisis, the family often turns to God, and the show has dealt with most of the major religions.[97]

Sexuality is often a source of jokes in the series or serves as the theme of certain episodes. Even though homosexuals are sometimes sources of gags, the series often comments on how American society treats them, with "Homer's Phobia" devoting an entire episode to the family making a gay friend and Homer's initial hostility to him. In 1990, The Simpsons became the first animated early evening show to depict a kiss between two men in "Simpson and Delilah".

Hallmarks

[edit]Opening sequence

[edit]The Simpsons' opening sequence is one of the show's most memorable hallmarks. The standard opening has gone through three iterations (a replacement of some shots at the start of the second season, and a brand new sequence when the show switched to high-definition in 2009).[98]

Each has the same basic sequence of events: the camera zooms through cumulus clouds, through the show's title towards the town of Springfield. The camera then follows the members of the family on their way home. Upon entering their house, the Simpsons settle down on their couch to watch television. The original opening was created by David Silverman, and was the first task he did when production began on the show.[99] The series' distinctive theme song was composed by musician Danny Elfman in 1989, after Groening approached him requesting a retro-style piece. This piece has been noted by Elfman as the most popular of his career.[100]

One of the most distinctive aspects of the opening is that three of its elements change from episode to episode: Bart writes different things on the school chalkboard,[99] Lisa plays different solos on her saxophone (or occasionally a different instrument), and different gags accompany the family as they enter their living room to sit on the couch.[101]

Halloween episodes

[edit]

The special Halloween episode has become an annual tradition. "Treehouse of Horror" first broadcast in 1990 as part of season two and established the pattern of three separate, self-contained stories in each Halloween episode.[102] These pieces usually involve the family in some horror, science fiction, or supernatural setting and often parody or pay homage to a famous piece of work in those genres.[103] They always take place outside the normal continuity of the show. Although the Treehouse series is meant to be seen on Halloween, this changed by the 2000s (and again in 2020), when new installments have premiered after Halloween due to Fox's current contract with Major League Baseball's World Series.[104] Prior to 2020 (between 2011 and 2019), every Treehouse of Horror episode had aired in October.

Humor

[edit]The show's humor turns on cultural references that cover a wide spectrum of society so that viewers from all generations can enjoy the show. Such references, for example, come from movies, television, music, literature, science, and history.[105] The animators also regularly add jokes or sight gags into the show's background via humorous or incongruous bits of text in signs, newspapers, billboards, and elsewhere. The audience may often not notice the visual jokes in a single viewing. Some are so fleeting that they become apparent only by pausing a video recording of the show or viewing it in slow motion.[106] Kristin Thompson argues that The Simpsons uses a "flurry of cultural references, intentionally inconsistent characterization, and considerable self-reflexivity about television conventions and the status of the programme as a television show."[107]

One of Bart's early hallmarks was his prank calls to Moe's Tavern owner Moe Szyslak where he asks for a gag name. Moe tries to find that person in the bar, but soon realizes it is a prank call and angrily threatens Bart. These calls were apparently based on a series of prank calls known as the Tube Bar recordings, though Groening has denied any causal connection.[108] Moe was based partly on Tube Bar owner Louis "Red" Deutsch, whose often profane responses inspired Moe's violent side.[109] As the series progressed, it became more difficult for the writers to come up with a fake name and to write Moe's angry response, and the pranks were dropped as a regular joke during the fourth season.[110][111] The Simpsons also often includes self-referential humor.[112] The most common form is jokes about Fox Broadcasting.[113] For example, the episode "She Used to Be My Girl" included a scene in which a Fox News Channel van drove down the street while displaying a large "Bush Cheney 2004" banner and playing Queen's "We Are the Champions", in reference to the 2004 U.S. presidential election and claims of conservative bias in Fox News.[114][115]

The show uses catchphrases, and most of the primary and secondary characters have at least one each.[116] Notable expressions include Homer's annoyed grunt "D'oh!", Mr. Burns' "Excellent" and Nelson Muntz's "Ha-ha!" Some of Bart's catchphrases, such as "¡Ay, caramba!", "Don't have a cow, man!" and "Eat my shorts!" appeared on T-shirts in the show's early days.[117] However, Bart rarely used the latter two phrases until after they became popular through the merchandising. The use of many of these catchphrases has declined in recent seasons. The episode "Bart Gets Famous" mocks catchphrase-based humor, as Bart achieves fame on the Krusty the Clown Show solely for saying "I didn't do it".[118]

Purported foreshadowing of actual events

[edit]The Simpsons has gained notoriety for jokes that appeared to become reality. Perhaps the most famous example comes from the episode "Bart to the Future", which mentions billionaire Donald Trump having been president of the United States at one time and leaving the nation broke. The episode first aired in 2000, sixteen years before Trump (who at the time was exploring a presidential run) was elected.[119] Another episode, "When You Dish Upon a Star", lampooned 20th Century Fox as a division of The Walt Disney Company. Nineteen years later, Disney purchased Fox.[120] Other examples purported as The Simpsons predicting the future include the introduction of the smartwatch, video chat services, Richard Branson's spaceflight[121][122] and Lady Gaga's acrobatic performance at the Super Bowl LI halftime show.[123]

Al Jean has commented on the show's purported ability to predict the future, explaining that they are really just "educated guesses" and stating that "if you throw enough darts, you're going to get some bullseyes."[124] Producer Bill Oakley stated, "There are very few cases where The Simpsons predicted something. It's mainly just coincidence because the episodes are so old that history repeats itself."[125] Fact-checking sources such as Snopes have debunked many of the claimed prophecies, explaining that the show's extensive run means "a lot of jokes, and a lot of opportunities for coincidences to appear" and "most of these 'predictions' have rather simple and mundane explanations".[126] For example, the device shown on The Simpsons with autocorrection is an Apple Newton, a real 1993 device notorious for its poor handwriting recognition.[127] Technologically advanced watches have appeared in numerous works of fiction, decades before The Simpsons.[128]

Influence and legacy

[edit]Idioms

[edit]A number of neologisms that originated on The Simpsons have entered popular vernacular.[129][130] Mark Liberman, director of the Linguistic Data Consortium, remarked, "The Simpsons has apparently taken over from Shakespeare and the Bible as our culture's greatest source of idioms, catchphrases and sundry other textual allusions."[130] The most famous catchphrase is Homer's annoyed grunt: "D'oh!" So ubiquitous is the expression that it is now listed in the Oxford English Dictionary, but without the apostrophe.[131] Dan Castellaneta says he borrowed the phrase from James Finlayson, an actor in many Laurel and Hardy comedies, who pronounced it in a more elongated and whining tone. The staff of The Simpsons told Castellaneta to shorten the noise, and it went on to become the well-known exclamation in the television series.[132]

Groundskeeper Willie's description of the French as "cheese-eating surrender monkeys" was used by National Review columnist Jonah Goldberg in 2003, after France's opposition to the proposed invasion of Iraq. The phrase quickly spread to other journalists.[130][133] "Cromulent" and "embiggen", words used in "Lisa the Iconoclast", have since appeared in the Dictionary.com's 21st Century Lexicon,[134] and scientific journals respectively.[130][135] "Kwyjibo", a fake Scrabble word invented by Bart in "Bart the Genius", was used as one of the aliases of the creator of the Melissa worm.[136] "I, for one, welcome our new insect overlords", was used by Kent Brockman in "Deep Space Homer" and has become a snowclone,[137] with variants of the utterance used to express obsequious submission. It has been used in media, such as New Scientist magazine.[138] The dismissive term "Meh", believed to have been popularized by the show,[130][139][140] entered the Collins English Dictionary in 2008.[141] Other words credited as stemming from the show include "yoink" and "craptacular".[130]

The Oxford Dictionary of Modern Quotations includes several quotations from the show. As well as "cheese-eating surrender monkeys", Homer's lines, "Kids, you tried your best and you failed miserably. The lesson is never try", from "Burns' Heir" (season five, 1994) as well as "Kids are the best, Apu. You can teach them to hate the things you hate. And they practically raise themselves, what with the Internet and all", from "Eight Misbehavin'" (season 11, 1999), entered the dictionary in August 2007.[142]

Many quotes/scenes have become popular Internet memes, including Jasper Beardley's quote "That's a paddlin'" from "The PTA Disbands" (season 6, 1995) and "Steamed Hams" from "22 Short Films About Springfield" (season 7, 1996).

Television

[edit]The Simpsons was the first successful animated program in American prime-time since Wait Till Your Father Gets Home in the 1970s.[143] During most of the 1980s, American pundits considered animated shows as appropriate only for children, and animating a show was too expensive to achieve a quality suitable for prime-time television. The Simpsons changed this perception,[21] initially leading to a short period where networks attempted to recreate prime-time cartoon success with shows like Capitol Critters, Fish Police, and Family Dog, which were expensive and unsuccessful.[144] The Simpsons' use of Korean animation studios for tweening, coloring, and filming made the episodes cheaper. The success of The Simpsons and the lower production cost prompted American television networks to take chances on other adult animated series.[21] This development led American producers to a 1990s boom in new, animated prime-time shows for adults, such as Beavis and Butt-Head, South Park, Family Guy, King of the Hill, Futurama (which was created by Matt Groening), and The Critic (which was also produced by Gracie Films).[21] For Family Guy creator Seth MacFarlane, "The Simpsons created an audience for prime-time animation that had not been there for many, many years ... As far as I'm concerned, they basically re-invented the wheel. They created what is in many ways—you could classify it as—a wholly new medium."[145]

The Simpsons has had crossovers with four other shows. In the episode "A Star Is Burns", Marge invites Jay Sherman, the main character of The Critic, to be a judge for a film festival in Springfield. Matt Groening had his name removed from the episode since he had no involvement with The Critic.[146] South Park later paid homage to The Simpsons with the episode "Simpsons Already Did It".[147] In "Simpsorama", the Planet Express crew from Futurama come to Springfield in the present to prevent the Simpsons from destroying the future.[148] In the Family Guy episode "The Simpsons Guy", the Griffins visit Springfield and meet the Simpsons.[149]

The Simpsons has also influenced live-action shows like Malcolm in the Middle, which featured the use of sight gags and did not use a laugh track unlike most sitcoms.[150][151] Malcolm in the Middle debuted January 9, 2000, in the time slot after The Simpsons. Ricky Gervais called The Simpsons an influence on The Office,[152] and fellow British sitcom Spaced was, according to its director Edgar Wright, "an attempt to do a live-action The Simpsons".[153] In Georgia, the animated television sitcom The Samsonadzes, launched in November 2009, has been noted for its very strong resemblance with The Simpsons, which its creator Shalva Ramishvili has acknowledged.[154][155]

LGBTQ representation

[edit]The Simpsons has historically been open to portrayals of LGBTQ characters and settings, and it has routinely challenged heteronormativity.[156][157] It was one of several animated television shows in the United States that began introducing characters that were LGBTQ, both openly and implied, in the 1990s.[156] While early episodes involving LGBTQ characters primarily included them through the use of stereotypes, The Simpsons developed several prominent LGBTQ characters over its run.[158] Producers of the show, such as Matt Groening and Al Jean, have expressed their opinion that LGBTQ representation in media is important, and that they seek to actively include it.[157][159] Some characters, such as Julio, were created with their sexual orientation in mind, with it being central to their character.[160] The show expanded its roster of openly LGBTQ characters through episodes in which prominent characters Patty Bouvier and Waylon Smithers came out in seasons 16 and 27, respectively.[161][162]

Release

[edit]Broadcast

[edit]| Season | No. of episodes |

Originally aired | Viewership | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Season premiere | Season finale | Time slot (ET) | Avg. households / viewers (in millions) |

Most watched episode | ||||

| Viewers (millions) |

Episode title | |||||||

| 1 | 1989–90 | 13 | December 17, 1989 | May 13, 1990 | Sunday 8:30 pm | 13.4m h.[n1][163] | 33.5[164] | "Life on the Fast Lane" |

| 2 | 1990–91 | 22 | October 11, 1990 | July 11, 1991 | Thursday 8:00 pm | 12.2m h.[n1][n2] | 33.6[165] | "Bart Gets an 'F'" |

| 3 | 1991–92 | 24 | September 19, 1991 | August 27, 1992 | 12m h.[n1][n3] | 25.5[166] | "Colonel Homer" | |

| 4 | 1992–93 | 22 | September 24, 1992 | May 13, 1993 | 12.1m h.[n1][167] | 28.6[168] | "Lisa's First Word" | |

| 5 | 1993–94 | 22 | September 30, 1993 | May 19, 1994 | 10.5m h.[n1][n4] | 24.0[169] | "Treehouse of Horror IV" | |

| 6 | 1994–95 | 25 | September 4, 1994 | May 21, 1995 | Sunday 8:00 pm | 9m h.[n1][170] | 22.2[171] | "Treehouse of Horror V" |

| 7 | 1995–96 | 25 | September 17, 1995 | May 19, 1996 | Sunday 8:00 pm (Episodes 1–24) Sunday 8:30 pm (Episode 25) |

8m h.[n1][172] | 22.6[173] | "Who Shot Mr. Burns? – Part II" |

| 8 | 1996–97 | 25 | October 27, 1996 | May 18, 1997 | Sunday 8:30 pm (Episodes 1–3) Sunday 8:00 pm (Episodes 4–12, 14–25) Friday 8:00 pm (Episode 13)[174] |

8.6m h.[175] | 20.41[176] | "The Springfield Files" |

| 9 | 1997–98 | 25 | September 21, 1997 | May 17, 1998 | Sunday 8:00 pm | 9.1m h.[177] | 19.80[178] | "The Two Mrs. Nahasapeemapetilons" |

| 10 | 1998–99 | 23 | August 23, 1998 | May 16, 1999 | 7.9m h.[179] | 19.11[180] | "Sunday, Cruddy Sunday" | |

| 11 | 1999–2000 | 22 | September 26, 1999 | May 21, 2000 | 8.2m h.[181] | 19.16[182] | "Faith Off" | |

| 12 | 2000–01 | 21 | November 1, 2000 | May 20, 2001 | 14.7m v.[183] | 18.52[184] | "HOMR" | |

| 13 | 2001–02 | 22 | November 6, 2001 | May 22, 2002 | Tuesday 8:30 pm (Episode 1) Sunday 8:00 pm (Episodes 2–20) Sunday 7:30 pm (Episode 21) Wednesday 8:00 pm (Episode 22) |

12.4m v.[185] | 14.91[186] | "The Parent Rap" |

| 14 | 2002–03 | 22 | November 3, 2002 | May 18, 2003 | Sunday 8:00 pm (Episodes 1–11, 13–21) Sunday 8:30 pm (Episodes 12, 22) |

13.4m v.[187] | 22.04[188] | "I'm Spelling as Fast as I Can" |

| 15 | 2003–04 | 22 | November 2, 2003 | May 23, 2004 | Sunday 8:00 pm | 10.6m v.[189] | 16.30[190] | "I, (Annoyed Grunt)-Bot" |

| 16 | 2004–05 | 21 | November 7, 2004 | May 15, 2005 | Sunday 8:00 pm (Episodes 1–7, 9–16, 18, 20) Sunday 10:30 pm (Episode 8) Sunday 8:30 pm (Episodes 17, 19, 21) |

9.6m v.[191] | 23.07[192] | "Homer and Ned's Hail Mary Pass" |

| 17 | 2005–06 | 22 | September 11, 2005 | May 21, 2006 | Sunday 8:00 pm | 9.1m v.[193] | 11.66[194] | "Treehouse of Horror XVI" |

| 18 | 2006–07 | 22 | September 10, 2006 | May 20, 2007 | 8.6m v.[195] | 11.63[196] | "The Mook, the Chef, the Wife and Her Homer" | |

| 19 | 2007–08 | 20 | September 23, 2007 | May 18, 2008 | 8m v.[197] | 11.74[198] | "Treehouse of Horror XVIII" | |

| 20 | 2008–09 | 21 | September 28, 2008 | May 17, 2009 | Sunday 8:00 pm (Episodes 1–7, 9–21) Sunday 8:30 pm (Episode 8) |

6.9m v.[199] | 12.40[200] | "Treehouse of Horror XIX" |

| 21 | 2009–10 | 23 | September 27, 2009 | May 23, 2010 | Sunday 8:00 pm | 7.2m v.[201] | 14.62[202] | "Once Upon a Time in Springfield" |

| 22 | 2010–11 | 22 | September 26, 2010 | May 22, 2011 | 7.3m v.[203] | 12.55[204] | "Moms I'd Like to Forget" | |

| 23 | 2011–12 | 22 | September 25, 2011 | May 20, 2012 | 7m v.[205] | 11.48[206] | "The D'oh-cial Network" | |

| 24 | 2012–13 | 22 | September 30, 2012 | May 19, 2013 | Sunday 8:00 pm (Episodes 1–21) Sunday 8:30 pm (Episode 22) |

6.3m v.[207] | 8.97[208] | "Homer Goes to Prep School" |

| 25 | 2013–14 | 22 | September 29, 2013 | May 18, 2014 | Sunday 8:00 pm (Episodes 1–11, 13–22) Sunday 7:30 pm (Episode 12) |

5.6m v.[209] | 12.04[210] | "Steal This Episode" |

| 26 | 2014–15 | 22 | September 28, 2014 | May 17, 2015 | Sunday 8:00 pm | 5.6m v.[211] | 10.62[212] | "The Man Who Came to Be Dinner" |

| 27 | 2015–16 | 22 | September 27, 2015 | May 22, 2016 | 4.7m v.[213] | 8.33[214] | "Teenage Mutant Milk-Caused Hurdles" | |

| 28 | 2016–17 | 22 | September 25, 2016 | May 21, 2017 | 4.8[215] | 8.19[216] | "Pork and Burns" | |

| 29 | 2017–18 | 21 | October 1, 2017 | May 20, 2018 | 4.1m v.[217] | 8.04[218] | "Frink Gets Testy" | |

| 30 | 2018–19 | 23 | September 30, 2018 | May 12, 2019 | 3.7m v.[219] | 8.20[220] | "The Girl on the Bus" | |

| 31 | 2019–20 | 22 | September 29, 2019 | May 17, 2020 | 3m v.[221] | 5.63[222] | "Go Big or Go Homer" | |

| 32 | 2020–21 | 22 | September 27, 2020 | May 23, 2021 | Sunday 8:00 pm (Episodes 1–10, 12–22) Sunday 9:00 pm (Episode 11) |

2.4m v.[223] | 4.93[224] | "Treehouse of Horror XXXI" |

| 33 | 2021–22 | 22 | September 26, 2021 | May 22, 2022 | 2.3m v.[225] | 3.97[226] | "Portrait of a Lackey on Fire" | |

| 34 | 2022–23 | 22 | September 25, 2022 | May 21, 2023 | Sunday 8:00 pm (Episodes 1–8, 10–22) Sunday 8:30 pm (Episode 9) |

2.1m v.[227] | 4.77[228] | "From Beer to Paternity" |

| 35 | 2023–24 | 18 | October 1, 2023 | May 19, 2024 | Sunday 8:00 pm (Episodes 1–5, 7, 10–18) Sunday 8:30 pm (Episodes 6, 8, 9) |

1.99m v.[229] | 5.41[230] | "Do the Wrong Thing" |

| 36 | 2024–25 | 22 | September 29, 2024 | May 18, 2025 | Sunday 8:00 pm (Episodes 1–2, 4–7, 10–18) Sunday 8:30 pm (Episodes 3, 8, 9) |

N/A | 3.31[231] | "Bottle Episode" |

| 37 | 2025–26 | 17 | September 28, 2025 | TBA | Sunday 8:00 pm | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Renewals

[edit]This section needs expansion with: Information regarding renewals before 2023 is needed. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . (September 2025) |

On January 26, 2023, the series was renewed for its 35th and 36th seasons, taking the show through the 2024–25 television season.[232] The two seasons contain a combined total of 51 episodes. Seven of these episodes are season 34 holdovers, while the other 44 will be produced in the production cycle of the upcoming seasons, bringing the show's overall episode total up to 801.[233] Season 35 premiered on October 1, 2023.[234] Season 36 premiered on September 29, 2024.[235]

On April 2, 2025, it was announced that The Simpsons would be renewed for four more seasons in what is considered a "mega deal" with parent company Disney. This renewal will take the show through the 2028–2029 television season, coinciding with the 40th anniversary of the show. Each season will consist of 15 episodes.[236]

Syndication

[edit]In the United States, the cable television network FXX, a sibling of 20th Television and formerly the Fox network, has exclusive cable and digital syndication rights for The Simpsons. Original contracts had previously stated that syndication rights for The Simpsons would not be sold to cable until the series conclusion, at a time when cable syndication deals were highly rare. The series has been syndicated to local broadcast stations in nearly all markets throughout the United States since September 1994.[237]

FXX premiered The Simpsons on their network on August 21, 2014, by starting a twelve-day marathon which featured the first 552 episodes (every single episode that had already been released at the time) aired chronologically, including The Simpsons Movie, which FX Networks had already owned the rights to air. It was the longest continuous marathon in the history of television (until VH1 Classic aired a 433-hour, nineteen-day, marathon of Saturday Night Live in 2015; celebrating that program's 40th anniversary).[238][239] The first day of the marathon was the highest rated broadcast day in the history of the network so far, the ratings more than tripled those of regular prime time programming for FXX.[240] Ratings during the first six nights of the marathon grew night after night, with the network ranking within the top 5 networks in basic cable each night.[241] In Australia, a marathon of every episode of the show (at the time) aired from December 16, 2019, to January 5, 2020, on Fox8 (a cable network operated on pay TV provider Foxtel and a corporate sibling to the American Fox network).[242] In Canada, Bell Media's Much and Rogers Media's FXX Canada syndicate the series as of January 2025.

After Disney acquired both 20th Television and FX Networks, it was announced that The Simpsons would air on the company's Freeform channel starting October 2, 2019.[243]

Streaming and digital sell-through

[edit]On October 21, 2014, a digital service courtesy of the FXNOW app, called Simpsons World, launched with every episode of the series accessible to authenticated FX subscribers, and is available on game consoles such as Xbox One, streaming devices such as Roku and Apple TV, and online via web browser.[244][245] There was early criticism of both wrong aspect ratios for earlier episodes and the length of commercial breaks on the streaming service, but that problem was soon amended with fewer commercial breaks during individual episodes.[246] Later it was announced that Simpsons World would now let users watch all of the SD episodes in their original format.[247] Simpsons World was discontinued after the launch of Disney+ on November 12, 2019, where the series streams exclusively.[248][249] Initially, the series was only available cropped to 16:9 without the option to view the original 4:3 versions, reigniting criticisms of cropping old episodes.[250] In response, Disney announced that "in early 2020, Disney+ will make the first 19 seasons (and some episodes from season 20) of The Simpsons available in their original 4:3 aspect ratio, giving subscribers a choice of how they prefer to view the popular series."[251][252] On May 28, 2020, Disney+ made the first 19 seasons, along with some episodes from season 20, of The Simpsons available in both 16:9 and the original 4:3 aspect ratio.[253] Season 31 came to Disney+ on October 2, 2020, with Hulu streaming the latest episodes of season 32 the next day. Season 32 came to Disney+ on September 29, 2021.

The season 3 premiere "Stark Raving Dad", which features Michael Jackson as the voice of Leon Kompowsky, was pulled out of rotation in 2019 by Matt Groening, James L. Brooks and Al Jean after HBO aired the documentary Leaving Neverland, in which two men share details into how Jackson allegedly abused them as children.[254][255] It is therefore unavailable on Disney+. However, the episode is still available on The Complete Third Season DVD box set released on August 26, 2003.[256]

In July 2017, all episodes from seasons 4 to 19 were made available for purchase on the iTunes Store in Canada.[257]

On August 10, 2024, it was announced that four episodes of season 36 would air exclusively on Disney+.[258]

Reception and achievements

[edit]Early success

[edit]The Simpsons was the Fox network's first television series to rank among a season's top 30 highest-rated shows.[259] In 1990, Bart quickly became one of the most popular characters on television in what was termed "Bartmania".[260][261][262][263] He became the most prevalent Simpsons character on memorabilia, such as T-shirts. In the early 1990s, millions of T-shirts featuring Bart were sold;[264] as many as one million were sold on some days.[265] Believing Bart to be a bad role model, several American public schools banned T-shirts featuring Bart next to captions such as "I'm Bart Simpson. Who the hell are you?" and "Underachiever ('And proud of it, man!')".[266][267][268] The Simpsons merchandise sold well and generated $2 billion in revenue during the first 14 months of sales.[266] Because of his popularity, Bart was often the most promoted member of the Simpson family in advertisements for the show, even for episodes in which he was not involved in the main plot.[269]

Due to the show's success, over the summer of 1990 the Fox Network decided to switch The Simpsons' time slot from 8:00 p.m. ET on Sunday night to the same time on Thursday, where it competed with The Cosby Show on NBC, the number one show at the time.[270][271] Through the summer, several news outlets published stories about the supposed "Bill vs. Bart" rivalry.[265][270] "Bart Gets an 'F'" (season two, 1990) was the first episode to air against The Cosby Show, and it received a lower Nielsen rating, tying for eighth behind The Cosby Show, which had an 18.5 rating. The rating is based on the number of household televisions that were tuned into the show, but Nielsen Media Research estimated that 33.6 million viewers watched the episode, making it the number one show in terms of actual viewers that week. At the time, it was the most watched episode in the history of the Fox Network,[272] and it is still the highest rated episode in the history of The Simpsons.[273] The show moved back to its Sunday slot in 1994 and has remained there ever since.[274]

The Simpsons has received overwhelmingly positive reviews from critics, and it has been noted for being described as "the most irreverent and unapologetic show on the air".[275] In a 1990 review of the show, Ken Tucker of Entertainment Weekly described it as "the American family at its most complicated, drawn as simple cartoons. It's this neat paradox that makes millions of people turn away from the three big networks on Sunday nights to concentrate on The Simpsons."[276] Tucker also described the show as a "pop-cultural phenomenon, a prime-time cartoon show that appeals to the entire family."[277]

Run length achievements

[edit]On February 9, 1997, The Simpsons surpassed The Flintstones with the episode "The Itchy & Scratchy & Poochie Show" as the longest-running prime-time animated series in the United States.[278] In 2004, The Simpsons replaced The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet (1952 to 1966) as the longest-running sitcom (animated or live action) in the United States in terms of the number of years airing.[279] In 2009, The Simpsons surpassed The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet's record of 435 episodes and is now recognized by Guinness World Records as the world's longest running sitcom (in terms of episode count).[280][281] In October 2004, Scooby-Doo briefly overtook The Simpsons as the American animated show with the highest number of episodes (albeit under several different iterations).[282] However, network executives in April 2005 again canceled Scooby-Doo, which finished with 371 episodes, and The Simpsons reclaimed the title with 378 episodes at the end of their seventeenth season.[283] In May 2007, The Simpsons reached their 400th episode at the end of the eighteenth season. While The Simpsons has the record for the number of episodes by an American animated show, other animated series have surpassed The Simpsons.[284] For example, the Japanese anime series Sazae-san has over 2,000 episodes (7,000+ segments) to its credit.[284]

In 2009, Fox began a year-long celebration of the show titled "Best. 20 Years. Ever." to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the premiere of The Simpsons. One of the first parts of the celebration is the "Unleash Your Yellow" contest in which entrants must design a poster for the show.[285] The celebration ended on January 10, 2010 (almost 20 years after "Bart the Genius" aired on January 14, 1990), with The Simpsons 20th Anniversary Special – In 3-D! On Ice!, a documentary special by documentary filmmaker Morgan Spurlock that examines the "cultural phenomenon of The Simpsons".[286][287]

As of the twenty-first season (2009–2010), The Simpsons became the longest-running American scripted primetime television series, having surpassed the 1955–1975 run of Gunsmoke. On April 29, 2018, The Simpsons also surpassed Gunsmoke's 635-episode count with the episode "Forgive and Regret".[279][288]

The Simpsons is both the longest-running and the highest ranking animated series to feature on TV Time's top 50 most followed TV shows ever.[289]

On February 6, 2019, it was announced that The Simpsons has been renewed for seasons 31 and 32.[290]

On March 3, 2021, it was announced that The Simpsons was renewed for seasons 33 and 34.[291]

Awards and honors

[edit]

The Simpsons has won dozens of awards since it debuted as a series, including 34 Primetime Emmy Awards,[75] 34 Annie Awards[292] and a Peabody Award.[293] In a 1999 issue celebrating the 20th century's greatest achievements in arts and entertainment, Time named The Simpsons the century's best television series, writing: "Dazzlingly intelligent and unapologetically vulgar, the Simpsons have surpassed the humor, topicality and, yes, humanity of past TV greats."[294] In that same issue, Time included Bart Simpson in the Time 100, the publication's list of the century's 100 most influential people.[295] Bart was the only fictional character on the list. On January 14, 2000, the Simpsons were awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.[296] Also in 2000, Entertainment Weekly magazine TV critic Ken Tucker named The Simpsons the greatest television show of the 1990s. Furthermore, viewers of the UK television channel Channel 4 have voted The Simpsons at the top of two polls: 2001's 100 Greatest Kids' TV shows (despite the show not being aimed at children),[297] and 2005's The 100 Greatest Cartoons,[298] with Homer Simpson voted into first place in 2001's 100 Greatest TV Characters.[299] Homer also placed ninth on Entertainment Weekly's list of the "50 Greatest TV icons".[300]

In 2002, The Simpsons ranked No. 8 on TV Guide's 50 Greatest TV Shows of All Time,[301] and was ranked the No. 6 cult show in 2004.[302] In 2007, it moved to No. 8 on TV Guide's cult shows list[303] and was included in Time's list of the "100 Best TV Shows of All Time".[304] In 2008 the show was placed in first on Entertainment Weekly's "Top 100 Shows of the Past 25 Years".[305] Empire named it the greatest TV show of all time.[306] In 2010, Entertainment Weekly named Homer "the greatest character of the last 20 years",[307] while in 2013 the Writers Guild of America listed The Simpsons as the 11th "best written" series in television history.[308] In 2013, TV Guide ranked The Simpsons as the greatest TV cartoon of all time[309] and the tenth greatest show of all time.[310] A 2015 The Hollywood Reporter survey of 2,800 actors, producers, directors, and other industry people named it as their No. 10 favorite show.[311] In 2015, British newspaper The Telegraph named The Simpsons as one of the 10 best TV sitcoms of all time.[312] Television critics Alan Sepinwall and Matt Zoller Seitz ranked The Simpsons as the greatest American TV series of all time in their 2016 book TV (The Book).[313] In 2022, Rolling Stone ranked The Simpsons as the second-greatest TV show of all time.[314] In 2023, Variety ranked The Simpsons as the fourth-greatest TV show of all time.[315]

Criticism

[edit]Controversy

[edit]Bart's rebellious, bad boy nature, which underlies his misbehavior and rarely leads to any punishment, led some people to characterize him as a poor role model for children.[316][317] In schools, educators claimed that Bart was a "threat to learning" because of his "underachiever and proud of it" attitude and negative attitude regarding his education.[318] Others described him as "egotistical, aggressive and mean-spirited".[319] In a 1991 interview, Bill Cosby described Bart as a bad role model for children, calling him "angry, confused, frustrated". In response, Matt Groening said, "That sums up Bart, all right. Most people are in a struggle to be normal [and] he thinks normal is very boring, and does things that others just wished they dare do."[320] On January 27, 1992, then-President George H. W. Bush said, "We are going to keep on trying to strengthen the American family, to make American families a lot more like the Waltons and a lot less like the Simpsons."[266] The writers rushed out a tongue-in-cheek reply in the form of a short segment that aired three days later before a rerun of "Stark Raving Dad" in which Bart replied, "Hey, we're just like the Waltons. We're praying for an end to the Depression, too."[321][322]

The show also received criticism from the nuclear power industry in its early years, with its portrayal of the evil boss Mr. Burns and "bungling idiot" employees (including Homer Simpson himself) with their lack of safety and security.[323] In a letter to the nuclear power-backed U.S. Council for Energy Awareness, producer Sam Simon apologized, stating, "I apologize that the Simpsons have offended a lot of people in the energy industry. I agree with you that in real life, Homer Simpson would not be employed at a nuclear power plant. On the other hand, he probably wouldn't be employed anywhere."[323]

Various episodes of the show have generated controversy. The Simpsons visit Australia in "Bart vs. Australia" (season six, 1995) and Brazil in "Blame It on Lisa" (season 13, 2002) and both episodes generated controversy and negative reaction in the visited countries.[324] In the latter case, Rio de Janeiro's tourist board—which claimed that the city was portrayed as having rampant street crime, kidnappings, slums, and monkey and rat infestations—went so far as to threaten Fox with legal action.[325] Groening was a fierce and vocal critic of the episode "A Star Is Burns" (season six, 1995), which featured a crossover with The Critic. He felt that it was just an advertisement for The Critic, and that people would incorrectly associate the show with him. When he was unsuccessful in getting the episode pulled, he had his name removed from the credits and went public with his concerns, openly criticizing James L. Brooks and saying the episode "violates the Simpsons' universe". In response, Brooks said, "I am furious with Matt, ... he's allowed his opinion, but airing this publicly in the press is going too far. ... his behavior right now is rotten."[146][326]

"The Principal and the Pauper" (season nine, 1997) is one of the most controversial episodes of The Simpsons. Many fans and critics reacted negatively to the revelation that Seymour Skinner, a recurring character since the first season, was an impostor. The episode has been criticized by Groening and by Harry Shearer, who provides the voice of Skinner. In a 2001 interview, Shearer recalled that after reading the script, he told the writers, "That's so wrong. You're taking something that an audience has built eight years or nine years of investment in and just tossed it in the trash can for no good reason, for a story we've done before with other characters. It's so arbitrary and gratuitous, and it's disrespectful to the audience."[327]

Bans

[edit]The show has reportedly been taken off the air in several countries. China banned it from prime-time television in August 2006, "in an effort to protect China's struggling animation studios".[328] In 2008, Venezuela barred the show from airing on morning television as it was deemed "unsuitable for children".[329] The same year, several Russian Pentecostal churches demanded that The Simpsons, South Park and some other Western cartoons be removed from broadcast schedules "for propaganda of various vices" and the broadcaster's license to be revoked. However, a court decision later dismissed this request.[330]

Perceived decline in quality

[edit]Critics' reviews of early Simpsons episodes praised the show for its sassy humor, wit, realism, and intelligence.[31][331] However, in the late 1990s, around the airing of season nine, the tone and emphasis of the show began to change. Some critics started calling the show "tired".[332] By 2000, some long-term fans had become disillusioned with the show, and pointed to its shift from character-driven plots to what they perceived as an overemphasis on zany antics.[333][334][335] Jim Schembri of The Sydney Morning Herald attributed the decline in quality to an abandonment of character-driven storylines in favor of celebrity cameo appearances and references to popular culture. Schembri wrote in 2011: "The central tragedy of The Simpsons is that it has gone from commanding attention to merely being attention-seeking. It began by proving that cartoon characters don't have to be caricatures; they can be invested with real emotions. Now the show has in essence fermented into a limp parody of itself. Memorable story arcs have been sacrificed for the sake of celebrity walk-ons and punchline-hungry dialogue."[336]

In 2010, the BBC noted "the common consensus is that The Simpsons' golden era ended after season nine",[337] and Todd Leopold of CNN, in an article looking at its perceived decline, stated "for many fans ... the glory days are long past."[335] Similarly, Tyler Wilson of Coeur d'Alene Press has referred to seasons one to nine as the show's "golden age",[338] and Ian Nathan of Empire described the show's classic era as being "say, the first ten seasons".[339] Jon Heacock of LucidWorks stated that "for the first ten years [seasons], the show was consistently at the top of its game", with "so many moments, quotations, and references – both epic and obscure – that helped turn the Simpson family into the cultural icons that they remain to this day".[340]

Mike Scully, who was showrunner during seasons nine through twelve, has been the subject of criticism.[341][342] Chris Suellentrop of Slate wrote that "under Scully's tenure, The Simpsons became, well, a cartoon ... Episodes that once would have ended with Homer and Marge bicycling into the sunset now end with Homer blowing a tranquilizer dart into Marge's neck. The show's still funny, but it hasn't been touching in years."[341] When asked in 2007 how the series' longevity is sustained, Scully joked: "Lower your quality standards. Once you've done that you can go on forever."[343]

Al Jean, who was showrunner during seasons thirteen through thirty-three,[344] has also been the subject of criticism, with some arguing that the show has continued to decline in quality under his tenure. Former writers have complained that under Jean, the show is "on auto-pilot", "too sentimental", and the episodes are "just being cranked out". Some critics believe that the show has "entered a steady decline under Jean and is no longer really funny".[345] John Ortved, author of The Simpsons: An Uncensored, Unauthorized History, characterized the Jean era as "toothless",[346] and criticized what he perceived as the show's increase in social and political commentary.[347] Jean responded: "Well, it's possible that we've declined. But honestly, I've been here the whole time and I do remember in season two people saying, 'It's gone downhill.' If we'd listened to that then we would have stopped after episode 13. I'm glad we didn't."[348]

In 2004, cast member Harry Shearer criticized what he perceived as the show's declining quality: "I rate the last three seasons as among the worst, so season four looks very good to me now."[349] Cast member Dan Castellaneta responded: "I don't agree, ... I think Harry's issue is that the show isn't as grounded as it was in the first three or four seasons, that it's gotten crazy or a little more madcap. I think it organically changes to stay fresh."[350] Also in 2004 author Douglas Coupland described claims of declining quality in the series as "hogwash", saying "The Simpsons hasn't fumbled the ball in fourteen years, it's hardly likely to fumble it now."[351] In an April 2006 interview, Groening said: "I honestly don't see any end in sight. I think it's possible that the show will get too financially cumbersome ... but right now, the show is creatively, I think, as good or better than it's ever been. The animation is incredibly detailed and imaginative, the stories do things that we haven't done before, so creatively there's no reason to quit."[9]

In 2016, popular culture writer Anna Leszkiewicz suggested that even though The Simpsons still holds cultural relevance, "contemporary appeal" is only for the "first ten or so seasons", with recent episodes only garnering mainstream attention when a favorite character from the golden era is killed off, or when new information and shock twists are given for old characters.[352] The series' ratings have also declined; while the first season enjoyed an average of 13.4 million viewing households per episode in the U.S.,[259] the twenty-first season had an average of 7.2 million viewers.[353]

Alan Sepinwall and Matt Zoller Seitz argued in their 2016 book titled TV (The Book) that the peak of The Simpsons are "roughly seasons 3–12", and that despite the decline, episodes from the later seasons such as "Eternal Moonshine of the Simpson Mind" and "Holidays of Future Passed" could be considered on par with the earlier classic episodes, further stating that "even if you want to call the show today a thin shadow of its former self, think about how mind-boggingly great its former self had to be for so-diminished a version to be watchable at all."[354][355]

In 2020, Uproxx writer Josh Kurp stated that while he agrees with the sentiment that The Simpsons is not as good as it used to be, it is because "it was working at a level of comedy and characterization that no show ever has." He felt there were still many reasons to watch the series, as it was "still capable of quality television, and even the occasional new classic" and the fact that the show was willing to experiment, giving examples such as bringing on guest animators like Don Hertzfeldt and Sylvain Chomet to produce couch gags, and guest writers like Seth Rogen, Evan Goldberg, Pete Holmes and Megan Amram to write episodes.[356] In the season thirty-two episode "I, Carumbus", the show itself makes a nod to these concerns in its credits gag where the god Jupiter notes that "It definitely feels like they're wrapping it up ... any day now."[357][358]

In a 2021 interview with NME, Jean was quoted as saying, "To people who say The Simpsons isn't as good as it used to be, I would say I think the world isn't as good as it used to be. But we're declining at a slower rate."[359]

A counter-narrative since mid-2023 has asserted that—with seasons thirty-three and thirty-four—the show started to become "good again".[360][361][362] ScreenRant asserted that season thirty-four was "seen as a return to form" and had been interpreted by reviewers as a "comeback".[363] They then wrote of season thirty-five that there was "no denying that there has been an obvious uptick in quality beginning as early as season 33".[364]

Race controversy

[edit]The stereotypical nature of the character Apu Nahasapeemapetilon has been the subject of controversy. Indian-American comedian Hari Kondabolu stated in his 2017 documentary The Problem with Apu that as a child he was a fan of The Simpsons and liked Apu, but he now finds the character's stereotypical nature troublesome. Defenders of the character responded that the show is built on comical stereotypes, with creator Matt Groening saying, "that's the nature of cartooning."[365] He added that he was "proud of what we do on the show", and "it's a time in our culture where people love to pretend they're offended".[366] In response to the controversy, Apu's voice actor, Hank Azaria, said he was willing to step aside from his role as Apu: "The most important thing is to listen to South Asian people, Indian people in this country when they talk about what they feel and how they think about this character."[367] In February 2020, he confirmed that he would no longer voice Apu. Groening stated at the same time that the character would remain in the show.

The criticisms were referenced in the season 29 episode "No Good Read Goes Unpunished", when Lisa breaks the fourth wall and addresses the audience by saying, "Something that started decades ago and was applauded and inoffensive is now politically incorrect. What can you do?" to which Marge replies, "Some things will be addressed at a later date." Lisa adds, "If at all." This reference was clarified by the fact that there was a framed photo of Apu with the caption on the photo saying "Don't have a cow, Apu", a play on Bart's catchphrase "Don't have a cow, man," as well as the fact that many Hindus do not eat cows as they are considered sacred. In October 2018, it was reported that Apu would be written out of the show,[368] which Groening denied.[369]

On June 26, 2020, in light of the various Black Lives Matter protests, Fox announced that recurring characters of color (Carl Carlson and Dr. Hibbert, among others) would no longer be voiced by white actors.[370] Beginning with season 32, Carl, a black character originally voiced by Azaria, is now voiced by black actor Alex Désert.[371] In addition, Bumblebee Man, a Spanish-speaking Latino character also originally voiced by Azaria, is now voiced by Mexican-American actor Eric Lopez,[372] and Dr. Hibbert, a black character originally voiced by Harry Shearer, is now voiced by black actor Kevin Michael Richardson.[373]

Other media

[edit]Comic books

[edit]Numerous Simpson-related comic books have been released over the years. The first comic strips based on The Simpsons appeared in 1991 in the magazine Simpsons Illustrated, which was a companion magazine to the show.[374] The comic strips were popular and a one-shot comic book titled Simpsons Comics and Stories, containing four different stories, was released in 1993 for the fans.[375] The book was a success and due to this, Groening and his companions Bill Morrison, Mike Rote, and Steve and Cindy Vance created the publishing company Bongo Comics.[375] A total of nine comic book series were published by Bongo Comics between 1993 and the company's dissolution in 2018.[376] Issues of Simpsons Comics, Bart Simpson's Treehouse of Horror and Bart Simpson have been collected and reprinted in trade paperbacks in the United States by HarperCollins.[377][378][379]

Film

[edit]

20th Century Fox and Gracie Films produced The Simpsons Movie, an animated film that was released on July 27, 2007.[380] The film was directed by long-time Simpsons producer David Silverman and written by a team of Simpsons writers comprising Matt Groening, James L. Brooks, Al Jean, George Meyer, Mike Reiss, John Swartzwelder, Jon Vitti, David Mirkin, Mike Scully, Matt Selman, and Ian Maxtone-Graham.[380] Production of the film occurred alongside continued writing of the series despite long-time claims by those involved in the show that a film would enter production only after the series had concluded.[380] There had been talk of a possible feature-length Simpsons film ever since the early seasons of the series. James L. Brooks originally thought that the story of the episode "Kamp Krusty" was suitable for a film, but he encountered difficulties in trying to expand the script to feature-length.[381] For a long time, difficulties such as lack of a suitable story and an already fully engaged crew of writers delayed the project.[9]

On August 10, 2018, 20th Century Fox announced that a sequel is in development.[382] In September 2025, a sequel was officially announced to be in production, set for theatrical release on July 23, 2027.[383]

Music

[edit]Collections of original music featured in the series have been released on the albums Songs in the Key of Springfield, Go Simpsonic with The Simpsons and The Simpsons: Testify.[384] Several songs have been recorded with the purpose of a single or album release and have not been featured on the show. The album The Simpsons Sing the Blues was released in September 1990 and was a success, peaking at No. 3 on the Billboard 200[385] and becoming certified 2× platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America.[386] The first single from the album was the pop rap song "Do the Bartman", performed by Nancy Cartwright and released on November 20, 1990. The song had backing vocals by Michael Jackson, although he did not receive any credit.[387] The Yellow Album was released in 1998, but received poor reception and did not chart in any country.[388][389][390]

The Simpsons Ride

[edit]

In 2007, it was officially announced that The Simpsons Ride, a simulator ride, would be implemented into the Universal Studios Orlando and Universal Studios Hollywood.[391] It officially opened May 15, 2008, in Florida[392] and May 19, 2008, in Hollywood.[393] In the ride, patrons are introduced to a cartoon theme park called Krustyland built by Krusty the Clown. However, Sideshow Bob is loose from prison to get revenge on Krusty and the Simpson family.[394] It features more than 24 regular characters from The Simpsons and features the voices of the regular cast members, as well as Pamela Hayden, Russi Taylor and Kelsey Grammer.[395] Harry Shearer did not participate in the ride, so none of his characters have vocal parts.[396] The ride also features clips from the show in the waiting line.

Video games

[edit]Numerous video games based on the show have been produced. Some of the early games include Konami's arcade game The Simpsons (1991) and Acclaim Entertainment's The Simpsons: Bart vs. the Space Mutants (1991).[397][398] More modern games include The Simpsons: Road Rage (2001), The Simpsons: Hit & Run (2003) and The Simpsons Game (2007).[399][400][401] Electronic Arts, which produced The Simpsons Game, has owned the exclusive rights to create video games based on the show since 2005.[402] In 2010, they released a game called The Simpsons Arcade for iOS.[403] Another EA-produced mobile game, Tapped Out, was released in 2012 for iOS users, then in 2013 for Android and Kindle users.[404][405][406] Two Simpsons pinball machines have been produced: one that was available briefly after the first season, and another in 2007, both out of production.[407]

Merchandise