Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Trombone

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

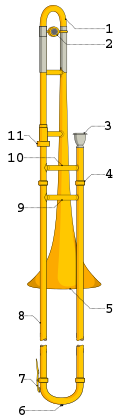

A tenor trombone | |

| Brass instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification | |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 423.22 (Sliding aerophone sounded by lip vibration) |

| Developed | Originated mid 15th century, sackbut in English until the early 18th century. |

| Playing range | |

Range of the tenor trombone. Ranges marked "F" are only possible with an F attachment; low B is only possible if the tuning slide of the F attachment is pulled out to E. For other trombones, see § Types. | |

| Related instruments | |

| Musicians | |

| Part of a series on |

| Musical instruments |

|---|

The trombone is a musical instrument in the brass family. As with all brass instruments, sound is produced when the player's lips vibrate inside a mouthpiece, causing the air column inside the instrument to vibrate. Nearly all trombones use a telescoping slide mechanism to alter the pitch instead of the valves used by other brass instruments. The valve trombone is an exception, using three valves similar to those on a trumpet, and the superbone has valves and a slide.

The word trombone derives from Italian tromba (trumpet) and -one (a suffix meaning 'large'), so the name means 'large trumpet'. The trombone has a predominantly cylindrical bore like the trumpet, in contrast to the more conical brass instruments like the cornet, the flugelhorn, the baritone, and the euphonium. The two most frequently encountered variants are the tenor trombone and bass trombone; when the word trombone is mentioned alone; it is mostly taken to mean the tenor model. These are treated as non-transposing instruments, reading at concert pitch in bass clef, with higher notes sometimes being notated in tenor clef. They are pitched in B♭, an octave below the B♭ trumpet and an octave above the B♭ contrabass tuba. The once common E♭ alto trombone became less common as improvements in technique extended the upper range of the tenor, but it is regaining popularity for its lighter sonority. In British brass-band music the tenor trombone is treated as a B♭ transposing instrument, written in treble clef, and the alto trombone is written at concert pitch, usually in alto clef.

A person who plays the trombone is called a trombonist or trombone player.

History

[edit]Etymology

[edit]Trombone comes from the Italian word tromba (trumpet) plus the suffix -one (large), meaning 'large trumpet'.

During the Renaissance, the equivalent English term was sackbut. The word first appears in court records in 1495 as shakbusshe. Shakbusshe is similar to sacabuche, attested in Spain as early as 1478. The French equivalent saqueboute appears in 1466.[1]

The German Posaune long predates the invention of the slide and could refer to a natural trumpet as late as the early fifteenth century.[2]

Origin

[edit]

The sackbut appeared in the 15th century and was used extensively across Europe, declining in most places by the mid to late 17th century. It was used in outdoor events, in concert, and in liturgical settings. Its principal role was as the contratenor part in a dance band.[3] It was also used, along with shawms, in bands sponsored by towns and courts. Trumpeters and trombonists were employed in German city-states to stand watch in the city towers and herald the arrival of important people to the city, an activity that signified wealth and strength in 16th-century German cities. These heralding trombonists were often viewed separately from the more skilled trombonists who played in groups such as the alta capella wind ensembles and the first orchestral ensembles, which performed in religious settings such as St Mark's Basilica in Venice in the early 17th century.[4] The 17th-century trombone had slightly smaller dimensions than a modern trombone, with a bell that was more conical and less flared. Modern period performers use the term "sackbut" to distinguish this earlier version of the trombone from the modern instrument.

Composers who wrote for trombone during this period include Claudio Monteverdi, Heinrich Schütz, Giovanni Gabrieli and his uncle Andrea Gabrieli. The trombone doubled voice parts in sacred works, but there are also solo pieces written for trombone in the early 17th century.

When the sackbut returned to common use in England in the 18th century, Italian music was so influential that the instrument became known by its Italian name, "trombone".[5] Its name remained constant in Italy (trombone) and in Germany (Posaune).

During the later Baroque period, Johann Sebastian Bach and George Frideric Handel used trombones on a few occasions. Bach called for a tromba di tirarsi, which may have been a form of the closely related slide trumpet, to double the cantus firmus in some liturgical cantatas.[6] He also employed a choir of four trombones to double the chorus in three of his cantatas (BWV 2, BWV 21 and BWV 38),[7] and used three trombones and a cornett in the cantata BWV 25. Handel used it in Samson, in Israel in Egypt, and in the Death March from Saul. All were examples of an oratorio style popular during the early 18th century. Score notations are rare because only a few professional "Stadtpfeiffer" or alta cappella musicians were available. Handel, for instance, had to import trombones to England from a Royal court in Hanover, Germany, to perform one of his larger compositions.[citation needed] Because of the relative scarcity of trombones, their solo parts were generally interchangeable with other instruments.

Classical period

[edit]The construction of the trombone did not change very much between the Baroque and Classical period, but the bell became slightly more flared. Christoph Willibald Gluck was the first major composer to use the trombone in an opera overture, in the opera Alceste (1767). He also used it in the operas Orfeo ed Euridice, Iphigénie en Tauride (1779), and Echo et Narcisse.

Early Classical composers occasionally included concertante movements with alto trombone as a solo instrument in divertimenti and serenades; these movements are often extracted from the multi-movement works and performed as standalone alto trombone concerti. Examples include the Serenade in E♭ (1755) by Leopold Mozart[8] and Divertimento in D major (1764)[9] by Michael Haydn. The earliest known independent trombone concerto is probably the Concerto for Alto Trombone and Strings in B♭ (1769)[10] by Johann Georg Albrechtsberger.

Mozart used the trombone in operas (notably in scenes featuring the Commendatore in Don Giovanni) and in sacred music. The prominent solo part in the Tuba Mirum section of his Requiem became a staple audition piece for the instrument. Aside from solo parts, Mozart's orchestration usually features a trio of alto, tenor and bass trombones, doubling the respective voices in the choir. The earliest known symphony featuring a trombone section is Symphony in C minor by Anton Zimmermann.[11] The date is uncertain but it is most probably from the peak of the composer's activity in the 1770s. The earliest confident date for introducing the trombone to the symphony is therefore Zimmermann's death in 1781.

Transition to Romantic period

[edit]Symphony in E♭ (1807) by Swedish composer Joachim Nicolas Eggert[12] features an independent trombone part. Ludwig van Beethoven is sometimes mistakenly credited with the trombone's introduction into the orchestra, having used it shortly afterwards in his Symphony No. 5 in C minor (1808), Symphony No. 6 in F major ("Pastoral"), and Symphony No. 9 ("Choral").

Romantic period

[edit]19th-century orchestras

[edit]Trombones were included in operas, symphonies, and other compositions by Felix Mendelssohn, Hector Berlioz, Franz Berwald, Charles Gounod, Franz Liszt, Gioacchino Rossini, Franz Schubert, Robert Schumann, Giuseppe Verdi, and Richard Wagner, and others.

The trombone trio was combined with one or two cornetts during the Renaissance and early Baroque periods. The replacement of cornetts with oboes and clarinets did not change the trombone's role as a support to the alto, tenor, and bass voices of the chorus (usually in ecclesiastical settings), whose moving harmonic lines were more difficult to pick out than the melodic soprano line. The introduction of trombones into the orchestra allied them more closely with trumpets, and soon a tenor trombone replaced the alto. The Germans and Austrians kept alto trombone somewhat longer than the French, who preferred a section of three tenor trombones until after the Second World War. In other countries, the trio of two tenor trombones and one bass became standard by about the mid-19th century.

Trombonists were employed less by court orchestras and cathedrals, who had been providing the instruments. Military musicians were provided with instruments, and instruments like the long F or E♭ bass trombone remained in military use until around the First World War. Orchestral musicians adopted the tenor trombone, as it could generally play any of the three trombone parts in orchestral scores.[vague]

Valve trombones in the mid-19th century did little to alter the make-up of the orchestral trombone section. While its use declined in German and French orchestras, the valve trombone remained popular in some countries, including Italy and Bohemia, almost to the exclusion of the slide instrument. Composers such as Giuseppe Verdi, Giacomo Puccini, Bedřich Smetana, and Antonín Dvořák scored for a valve trombone section.

As the ophicleide or the tuba was added to the orchestra during the 19th century, bass trombone parts were scored in a higher register than previously.[vague] The bass trombone regained some independence in the early 20th century. Experiments with the trombone section included Richard Wagner's addition of a contrabass trombone in Der Ring des Nibelungen and Gustav Mahler's and Richard Strauss' addition of a second bass trombone to the usual trio of two tenors and one bass. The majority of orchestral works are still scored for the usual mid- to late-19th-century low brass section of two tenor trombones, one bass trombone, and one tuba.

19th-century wind bands

[edit]Wind bands began during the French Revolution of 1791 and have always included trombones. They became more established in the 19th century and included circus bands, military bands, brass bands (primarily in the UK), and town bands (primarily in the US). Some of these, especially military bands in Europe, used rear-facing trombones with the bell pointing behind the player's left shoulder. These bands played a limited repertoire that consisted mainly of orchestral transcriptions, arrangements of popular and patriotic tunes, and feature pieces for soloists (usually cornetists, singers, and violinists). A notable work for wind band is Berlioz's 1840 Grande symphonie funèbre et triomphale, which uses a trombone solo for the entire second movement. Toward the end of the 19th century, trombone virtuosi began appearing as soloists in American wind bands. Arthur Pryor, who played with the John Philip Sousa band and formed his own band, was one of the most famous of these trombonists.

19th-century pedagogy

[edit]In the Romantic era, Leipzig became a center of trombone pedagogy, and the instrument was taught at the Musikhochschule founded by Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy. The Paris Conservatory and its yearly exhibition also contributed to trombone education. At the Leipzig academy, Mendelssohn's bass trombonist, Karl Traugott Queisser, was the first in a long line of distinguished professors of the trombone. Several composers wrote works for Queisser, including Mendelssohn's concertmaster Ferdinand David, Ernst Sachse, and Friedrich August Belcke. David wrote his Concertino for Trombone and Orchestra in 1837, and Sachse's solo works remain popular in Germany. Queisser championed and popularized Christian Friedrich Sattler's tenor-bass trombone during the 1840s, leading to its widespread use in orchestras throughout Germany and Austria.

19th-century construction

[edit]Sattler had a great influence on trombone design, introducing a significantly larger bore (the most important innovation since the Renaissance), Schlangenverzierungen (snake decorations), the bell garland, and the wide bell flare. These features were widely copied during the 19th century and are still found on German made trombones.

The trombone was improved in the 19th century with the addition of "stockings" at the end of the inner slide to reduce friction, the development of the water key to expel condensation from the horn, and the occasional addition of a valve that was designed to be set in a single position but later became the modern F-valve. The valve trombone appeared around the 1850s shortly after the invention of valves, and was in common use in Italy and Austria in the second half of the century.

Twentieth century

[edit]

With the rise of recorded music and music schools, orchestral trombone sections around the world began to have a more consistent idea of a standard trombone sound. In the 1940s, British orchestras abandoned the use of small bore tenors and G basses in favor of the American/German choice of large bore tenors and B♭ basses. French orchestras did the same in the 1960s.

20th-century wind bands

[edit]During the first half of the 20th century the popularity of touring and community concert bands in the United States decreased. At the same time, the development of music education in the public school system made high-school and university concert bands and marching bands ubiquitous. A typical concert band trombone section consists of two tenor trombones and one bass trombone, but using multiple players per part is common practice, especially in public-school settings.[citation needed]

Use in jazz

[edit]In the 1900s the trombone and the tuba played bass lines and outlined chords to support improvisation by the higher-pitched instruments. It began to be used as a solo instrument during the swing era of the mid-1920s. Jack Teagarden and J. J. Johnson were early trombone soloists.[13][14]

20th-century construction

[edit]The trombone's construction changed in the 20th century. Different materials were used, mouthpiece, bore, and bell dimensions increased, and different mutes and valves were developed. Despite the overall trend towards larger bore instruments, many European trombone makers prefer a slightly smaller bore than their American counterparts.

One of the most significant changes was the development of the F-attachment trigger. Through the mid-20th century there was no need for orchestral trombonists to use instruments with the F attachment trigger. As contemporary composers such as Mahler began to write lower passages for the trombone, the trigger became necessary.

Contemporary use

[edit]The trombone can be found in symphony orchestras, concert bands, big bands, marching bands, military bands, brass bands, and brass choirs. In chamber music, it is used in brass quintets, quartets, and trios, and also in trombone groups ranging from trios to choirs. A trombone choir can vary in size from five to twenty or more members. Trombones are also common in swing, jazz, merengue, salsa, R&B, ska, and New Orleans brass bands.

Construction

[edit]

|

|

The trombone is a predominantly cylindrical tube with two U-shaped bends and a flared bell at the end. The tubing is approximately cylindrical but contains a complex series of tapers which affect the instrument's intonation. As with other brass instruments, sound is produced by blowing air through pursed lips producing a vibration that creates a standing wave in the instrument.

The detachable cup-shaped mouthpiece is similar to that of the baritone horn and closely related to that of the trumpet. It has a venturi:[15] a small constriction of the air column that adds resistance, greatly affecting the tone of the instrument. The slide section consists of a leadpipe, inner and outer slide tubes, and bracing, or "stays". The soldered stays on modern instruments replaced the loose stays found on sackbuts (medieval precursors to trombones).[16][17]

The most distinctive feature of the trombone is the slide that lengthens the tubing and lowers the pitch (cf. valve trombone). During the Renaissance, sleeves (called "stockings") were developed to decrease friction that would impede the slide's motion. These were soldered onto the ends of the inner slide tubes to slightly increase their diameter. The ends of inner slides on modern instruments are manufactured with a slightly larger diameter to achieve the same end. This part of the slide must be lubricated frequently. The slide section is connected to the bell section by the neckpipe and a U-bend called the bell or back bow. The joint connecting the slide and bell sections has a threaded collar to secure the connection. Prior to the early 20th century this connection was made with friction joints alone.

Trombones have a short tuning slide in the U-shaped bend between the neckpipe and the bell, a feature designed by the French maker François Riedlocker in the early 19th century. It was incorporated into French and British designs, and later to German and American models, although German trombones were built without tuning slides well into the 20th century. Many types of trombone also include one or more rotary valves connected to additional tubing which lengthens the instrument. This extends the low range of the instrument and creates the option of using alternate slide positions for many notes.

Like the trumpet, the trombone is considered a cylindrical bore instrument since it has extensive sections of tubing that are of unchanging diameter (the slide section must be cylindrical in order to function). Tenor trombones typically have a bore of 0.450 inches (11.4 mm) (small bore) to 0.547 inches (13.9 mm) (large or orchestral bore) after the leadpipe and through the slide. The bore expands through the bow to the bell, which is typically between 7 and 8+1⁄2 inches (18 and 22 cm). A number of common variations on trombone construction are noted below.

Bells

[edit]Trombone bells (and sometimes slides) may be constructed of different brass mixtures. The most common material is yellow brass (70% copper, 30% zinc), but other materials include rose brass (85% copper, 15% zinc) and red brass (90% copper, 10% zinc). Some manufacturers offer interchangeable bells. Tenor trombone bells are usually between 7 and 9 in (18–23 cm) in diameter, with most being between 7+1⁄2 and 8+1⁄2 in (19–22 cm). The smallest sizes are found on jazz trombones and older narrow-bore instruments, while the larger sizes are common on orchestral models. Bass trombone bells can be 10+1⁄2 in (27 cm) or more, with most being between 9+1⁄2 and 10 in (24 and 25 cm). The bell may be made from two separate brass sheets or from one single piece of metal, hammered on a mandrel to shape it. The edge of the bell may be finished with or without a piece of bell wire to secure it, which also affects the tone quality; most bells are built with bell wire. Occasionally, trombone bells are made from solid sterling silver.

Valve attachments

[edit]

Modern trombones often have a valve attachment, an extra loop of tubing attached to the bell section and engaged by a valve operated by the left thumb by means of a lever or trigger. The valve attachment aids in increasing the lower range of the instrument, while also allowing alternate slide positions for difficult music passages. A valve can also make trills easier.

The valve attachment was originally developed by German instrument maker Christian Friedrich Sattler in the late 1830s for the Tenorbaßposaune (lit. 'tenor-bass trombone'), a B♭ tenor trombone built with the wider bore and larger bell of a bass trombone that Sattler had earlier invented in 1821. Sattler's valve attachment added about 3 feet (0.9 m) of tubing to lower the fundamental pitch from B♭ to F, controlled by a rotary valve, and is essentially unchanged in modern instruments.

Valve attachments are most commonly found on tenor and bass trombones, but they can appear on sizes from soprano to contrabass.

- Soprano

- In the early 2010s Torbjörn Hultmark of the Royal College of Music commissioned the first soprano trombone in B♭ with an F valve, built by Thein Brass.[19]

- Alto

- Although rare on the E♭ alto trombone, a valve attachment usually lowers the instrument a perfect fourth into B♭, providing the first five or six positions from the tenor trombone slide. Some alto models have what is called a trill valve, providing a small loop of tubing that lowers the instrument by only a minor or major second, into D or D♭ respectively.[20]

- Tenor

- Tenor trombones, especially the larger bore symphonic models, commonly have a valve attachment which lowers the instrument from B♭ to F.

- It provides access to the otherwise missing notes between the pedal B♭1 in first position, and the second partial E2 in seventh, as well as providing alternate slide positions for other notes in long (sixth and seventh) positions. Because the attachment tubing increases the length of the overall instrument by one-third, the distances between slide positions must also be one-third longer when the valve is engaged, resulting in only six positions available on the F slide, to low C2. Thus, the F attachment cannot provide the low B♮1, but it usually has a sufficiently long tuning slide to lower it into E as required, which will provide B♮1 in a very long position.[21]

- Tenor trombones without a valve are sometimes known as straight trombones.

- Bass

- The modern bass trombone usually has two valve attachments to provide all of the notes that are absent on an instrument with no valves (B♮1 – E2). This allows the player to produce a complete chromatic range upwards from the pedal register.

- The first valve is an F attachment the same as that found on a tenor trombone and extends the range down to C2. The second valve, engaged together with the first, lowers the instrument to D (or less commonly, E♭) and provides the low B1. The second valve can be dependent, where it serves to lower the F attachment to D and has no effect alone. More commonly the second valve is independent, where it can be engaged separately to lower the instrument to G♭, or to D when both are engaged.[22]

- Single-valve B♭ bass trombones with an F attachment are still made but are now less common than two-valve bass trombones. They are essentially very large bore tenor trombones, and likewise cannot provide the low B♮1 without lowering the valve to E with a long tuning slide.[23]

- Contrabass

- Contrabass trombones in F typically have two independent valves, tuned either to C and D♭ combining to A, or in European models tuned to D and B♭ combining to A♭. Contrabass trombones in low B♭ usually have only one valve in F, although Miraphone make a model in C with two independent valves in G and A♭, which combine to E.[24]

Valve types

[edit]The most common type of valve seen for valve attachments is the rotary valve, appearing on most band instruments, as well as most student and intermediate model trombones. Many improvements of the rotary valve, as well as entirely new and radically different valve designs, have been invented since the mid 20th century to give the trombone a more open, free sound than the tight bends in conventional rotary valve designs would allow. Many of these new valve designs have been widely adopted by players, especially in symphony orchestras. The Thayer axial flow valve is offered on professional models from most trombone manufacturers, and the Hagmann valve particularly from European manufacturers.

Some trombones have three piston or rotary valves instead of a slide; see valve trombone.

Tubing

[edit]

F attachment tubing usually has a larger bore through the attachment than through the rest of the instrument. A typical slide bore for an orchestral tenor trombone is 0.547 in (13.9 mm) while the bore in the attachment is 0.562 in (14.3 mm). The attachment tubing also incorporates a tuning slide to tune the valve separately from the rest of the instrument, usually long enough to lower the pitch by a semitone when fully extended (from F to E on tenor and bass trombones, to reach the missing low B1).

Valve attachment tubing is often coiled tightly to keep within the bell section (closed wrap or traditional wrap). A less coiled configuration, called open wrap, is found on some 19th and early 20th century instruments.[25] In the early 1980s, American instrument manufacturers began producing open wrap instruments after Californian instrument technician Larry Minick introduced open wraps around the same time that the Thayer valve began to emerge among orchestral players.[26] Open wrap F attachment tubing is shaped in a single loop free of tight bends, resulting in a freer response and more "open" sound through the valve.[27]

In marching bands and other situations where the trombone may be more prone to damage, the confined traditional wrap is more common, since open wrap tubing protrudes behind the bell section.

Tuning

[edit]

Some trombones are tuned using a mechanism in the slide section instead of a tuning slide in the bell section. Having the tuning slide in the bell section (the more typical setup) requires two sections of cylindrical tubing in an otherwise conical part of the instrument, which affects the tone quality. Placing the tuning mechanism in the cylindrical slide section allows the bell section to remain conical.

Slides

[edit]Common and popular bore sizes for trombone slides are 0.500, 0.508, 0.525 and 0.547 in (12.7, 12.9, 13.3 and 13.9 mm) for tenor trombones, and 0.562 in (14.3 mm) for bass trombones. The slide may also be built with a dual-bore configuration, in which the bore of the second leg of the slide is slightly larger than the bore of the first leg, producing a stepwise conical effect. The most common dual-bore combinations are 0.481–0.491 in (12.2–12.5 mm), 0.500–0.508 in (12.7–12.9 mm), 0.508–0.525 in (12.9–13.3 mm), 0.525–0.547 in (13.3–13.9 mm), 0.547–0.562 in (13.9–14.3 mm) for tenor trombones, and 0.562–0.578 in (14.3–14.7 mm) for bass trombones.

Mouthpiece

[edit]

The mouthpiece is a separate part of the trombone and can be interchanged between similarly sized trombones from different manufacturers. Available mouthpieces for trombone (as with all brass instruments) vary in material composition, length, diameter, rim shape, cup depth, throat entrance, venturi aperture, venturi profile, outside design and other factors. Variations in mouthpiece construction affect the individual player's ability to make a lip seal and produce a reliable tone, the timbre of that tone, its volume, the instrument's intonation tendencies, the player's subjective level of comfort, and the instrument's playability in a given pitch range.

Mouthpiece selection is a highly personal decision. Thus, a symphonic trombonist might prefer a mouthpiece with a deeper cup and sharper inner rim shape in order to produce a rich symphonic tone quality, while a jazz trombonist might choose a shallower cup for brighter tone and easier production of higher notes. Further, for certain compositions, these choices between two such performers could easily be reversed. Some mouthpiece makers now offer mouthpieces that feature removable rims, cups, and shanks allowing players to further customize and adjust their mouthpieces to their preference.

Plastic

[edit]

Instruments made mostly from plastic, including the pBone and the Tromba plastic trombone, emerged in the 2010s as a cheaper and more robust alternative to brass.[28][29] Plastic instruments could come in almost any colour but the sound plastic instruments produce is different from that of brass. While originally seen as a gimmick, these plastic models have found increasing popularity of the last decade and are now viewed as practice tools that make for more convenient travel as well as a cheaper option for beginning players not wishing to invest so much money in a trombone right away. Manufacturers now produce large-bore models with triggers as well as smaller alto models.

Regional variations

[edit]Germany and Austria

[edit]

German trombones have been built in a wide variety of bore and bell sizes. The traditional German Konzertposaune can differ substantially from American designs in many aspects. The mouthpiece is typically rather small and is placed into a slide section with a very long leadpipe of at least 12 to 24 inches (30–60 cm). The whole instrument is typically made of gold brass. They are constructed using very thin metal (especially in the bell section), and many have a metal ring called a Kranz (lit. 'wreath') on the rim of the bell. Their sound is very even across dynamic levels but it can be difficult to play at louder volumes.[15] While their bore sizes were considered large in the 19th century, German trombones have altered very little over the last 150 years and are now typically somewhat smaller than their American counterparts. Bell sizes remain very large in all sizes of German trombone and a bass trombone bell may exceed 10 inches (25 cm) in diameter.

Valve attachments in tenor and bass trombones were first seen in the mid 19th century, originally on the tenor B♭ trombone. Before 1850, bass trombone parts were mostly played on a slightly longer F-bass trombone (a fourth lower). The first valve was simply a fourth-valve, or in German "Quart-Ventil", built onto a B♭ tenor trombone, to allow playing in low F. This valve was first built without a return spring, and was only intended to set the instrument in B♭ or F for extended passages.[30] Since the mid-20th century, modern instruments use a trigger to engage the valve while playing.

As with other traditional German and Austrian brass instruments, rotary valves are used to the exclusion of almost all other types of valve, even in valve trombones. Other features often found on German trombones include long water keys as well as Schlangenverzierungen (snake decorations) on the slide and bell U-bows to help protect the tubing from damage.

Since around 1925, when jazz music became popular, Germany has been selling "American trombones" as well. Most trombones made and/or played in Germany today, especially by amateurs, are built in the American fashion, as those are much more widely available, and thus far cheaper. However, some higher-end manufacturers such as Thein make modern iterations of the classic German Konzertposaune, as well as American-style trombones with German features like the Kranz and snake decorations.

France

[edit]French trombones were built in the very smallest bore sizes up to the end of the Second World War and whilst other sizes were made there, the French usually preferred the tenor trombone to any other size. French music, therefore, usually employed a section of three tenor trombones up to the mid–20th century. Tenor trombones produced in France during the 19th and early 20th centuries featured bore sizes of around 0.450 in (11.4 mm), small bells of not more than 6 in (15 cm) in diameter, as well as a funnel-shaped mouthpiece slightly larger than that of the cornet or horn. French tenor trombones were built in both C and B♭, altos in D♭, sopranos in F, piccolos in B♭, basses in G and E♭, and contrabasses in B♭.

Types

[edit]The most frequently encountered types of trombone today are the tenor and bass, though as with many other instrument families such as the clarinet, the trombone has been built in sizes from piccolo to contrabass. Although trombones are usually constructed with a slide to change the pitch, valve trombones instead use the set of three valves common on other brass instruments.

Slide trombones

[edit]

Contrabass trombone

[edit]The contrabass trombone is the lowest trombone, first appearing in BB♭ an octave below the tenor with a double slide. This design was commissioned by Wagner in the 1870s for his Der Ring des Nibelungen opera cycle. Since the late 20th century however, it has largely been supplanted by a less cumbersome single-slide bass-contrabass instrument pitched in 12' F. With two valve attachments to provide the same full range as its predecessor, this design is effectively a modern bass trombone built down a perfect fourth. Although the contrabass has only appeared occasionally in orchestral repertoire and is not a permanent member of the modern orchestra, it has enjoyed a revival in the 21st century, particularly in film and video game soundtracks.

Bass trombone

[edit]Although early instruments were pitched in G, F or E♭ below the tenor trombone, the modern bass trombone is pitched in the same B♭ as the tenor but with a wider bore, a larger bell, and a larger mouthpiece. These features facilitate playing in the lower register of the instrument. Modern bass trombones have valves that allow a fully chromatic range down to the pedal register (B♭1). In Britain, the bass trombone in G was used in orchestras from the mid-19th century and survived into the 1950s, particularly in British brass bands.

Tenor trombone

[edit]The tenor trombone has a fundamental note of B♭ and is usually treated as a non-transposing instrument (see below). Tenor trombones with C as their fundamental note were almost equally popular in the mid-19th century in Britain and France. As the trombone in its simplest form has neither crooks, valves nor keys to lower the pitch by a specific interval, trombonists use seven chromatic slide positions. Each position progressively increases the length of the air column, thus lowering the pitch.

Extending the slide from one position to the next lowers the pitch by one semitone. Thus, each note in the harmonic series can be lowered by an interval of up to a tritone. The lowest note of the standard instrument is therefore an E♮ – a tritone below B♭. Most experienced trombonists can play lower "falset" notes and much lower pedal notes (first partials or fundamentals, which have a peculiar metallic rumbling sound). Slide positions are subject to adjustment, compensating for imperfections in the tuning of different harmonics. The fifth partial is rather flat on most trombones and usually requires a minute shortening of the slide position to compensate; other small adjustments are also normally required throughout the range. Trombonists make frequent use of alternate positions to minimize slide movement in rapid passages; for instance, B♭3 may be played in first or fifth position. Alternate positions are also needed to allow a player to produce a glissando to or from a higher note on the same partial.

While the lowest note of the tenor trombone's range (excluding fundamentals or pedal notes) is E2, the trombone's upper range is theoretically open-ended. The practical top of the range is sometimes considered to be F5, or more conservatively D5. The range of the C tenor trombone is F♯2 to G5.

Alto trombone

[edit]The alto trombone is smaller than the tenor trombone and almost always pitched in E♭ a fourth higher than the tenor, although examples pitched in F are occasionally found. Modern instruments are sometimes fitted with a valve to lower the pitch, either by a semitone to D (known as a "trill" valve), or by a fourth into B♭. The alto trombone was commonly used in the 16th to the 18th centuries in church music to strengthen the alto voice, particularly in the Mass. Early 19th century composers such as Beethoven, Brahms, and Schumann began writing for alto trombone in their symphonies, but the subsequent use and popularity of tenor trombones in the orchestra largely eclipsed their use until a modern revival that began in the late 20th century.

Soprano trombone

[edit]The soprano trombone is usually pitched in B♭ an octave above the tenor, and has seldom been used since its first known appearance in 1677 outside of trombone choirs in Moravian Church music. Built with mouthpiece, bore and bell dimensions similar to the B♭ trumpet, it tends to be played by trumpet players. During the 20th century some soprano trombones—dubbed slide cornets—were made as novelties or for use by jazz players including Louis Armstrong and Dizzy Gillespie. A small number of contemporary proponents of the instrument include jazz artists Wycliffe Gordon and Christian Scott, and classical trumpeter Torbjörn Hultmark, who advocates for its use as an instrument for young children to learn music.

Sopranino and piccolo trombones

[edit]The sopranino and piccolo trombones appeared in the 1950s as novelty instruments, and are even smaller and higher than the soprano. They are pitched in high E♭ and B♭ respectively, one octave above the alto and soprano trombones. Owing to being essentially a slide variant of the piccolo trumpet, they are played primarily by trumpet players.

Trombones with valves

[edit]Valve trombone

[edit]

In the 19th century as soon as brass instrument valves were invented, trombones with valves instead of slides were adopted widely in orchestras, and remain popular in some parts of Europe and in military bands.

Cimbasso

[edit]

The cimbasso covers the same range as a tuba or a contrabass trombone. The term cimbasso first appeared in early 19th century Italian opera scores, and originally referred to an upright serpent or an ophicleide. The modern cimbasso first appeared as the trombone basso Verdi in the 1880s and has three to six piston or rotary valves and a predominantly cylindrical bore. They are most often pitched in 12' F, although models are available in E♭ and occasionally 16' C and 18' B♭. The cimbasso is most commonly used in performances of late Romantic Italian operas by Verdi and Puccini, but has also experienced a 21st-century revival in film, television and video game soundtracks.

Superbone

[edit]

A hybrid, "duplex" or "double" trombone is a design of trombone that has both a slide and a set of three valves for altering the pitch. It has been reinvented several times since first appearing in the 19th century by Besson, and later Conn. Jazz trombonist and machinist Brad Gowans invented his "valide trombone" in the 1940s with a short four-position slide. In the 1970s Maynard Ferguson and Holton produced the "Superbone", very similar to the earlier Conn. In 2013 Schagerl in collaboration with James Morrison announced a larger bore variant with rotary valves.

Flugabone

[edit]

The "flugabone" (or sometimes "flugelbone"), portmanteau of "flugelhorn" and "trombone", also known as the "marching trombone", is a marching brass instrument, essentially a valve trombone wrapped into a compact flugelhorn shape.[31] It retains the cylindrical bore of the trombone, rather than the conical bore of either the flugelhorn or bugle, and thus is similar in playing characteristics to a valve trombone. A similar marching trombone is the "trombonium" first produced by King Musical Instruments, wrapped and held vertically like a euphonium.

Other variants

[edit]Sackbut

[edit]

The term "sackbut" refers to the early forms of the trombone commonly used during the Renaissance and Baroque eras, with a characteristically smaller, more cylindrically proportioned bore, and a less-flared bell.

Buccin

[edit]

A distinctive form of tenor trombone was popularized in France in the early 19th century. Called the buccin, it featured a tenor trombone slide and a bell that ended in a zoomorphic (serpent or dragon) head. It sounds like a cross between a trombone and a French horn, with a very wide dynamic range but a limited and variable range of pitch. Hector Berlioz wrote for the buccin in his Messe solennelle of 1824.

Tromboon

[edit]A portmanteau of "trombone" and "bassoon", the "tromboon" was created by musical parodist Peter Schickele by replacing a trombone's mouthpiece with the reed and bocal of a bassoon. It appears in several humorous works of Schickele's fictional composer, P. D. Q. Bach.

Technique

[edit]Basic slide positions

[edit]

The modern system has seven chromatic slide positions on a tenor trombone in B♭. It was first described by Andre Braun circa 1795.[32]

In 1811 Joseph Fröhlich wrote on the differences between the modern system and an old system where four diatonic slide positions were used and the trombone was usually keyed to A.[33] To compare between the two styles the chart below may be helpful (take note for example, in the old system contemporary 1st-position was considered "drawn past" then current 1st).[33] In the modern system, each successive position outward (approximately 3+1⁄4 inches [8 cm]) will produce a note which is one semitone lower when played in the same partial. Tightening and loosening the lips will allow the player to "bend" the note up or down by a semitone without changing position, so a slightly out-of-position slide may be compensated for by ear.

| New system | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old system | – | 1 | – | 2 | – | 3 | 4 |

Partials and intonation

[edit]

As with all brass instruments, progressive tightening of the lips and increased air pressure allow the player to move to different partial in the harmonic series. In the first position (also called closed position) on a B♭ trombone, the notes in the harmonic series begin with B♭2 (one octave higher than the pedal B♭1), F3 (a perfect fifth higher than the previous partial), B♭3 (a perfect fourth higher), D4 (a major third higher), and F4 (a minor third higher).

F4 marks the sixth partial, or the fifth overtone. Notes on the next partial, for example A♭4 (a minor third higher) in first position, tend to be out of tune in regards to the twelve-tone equal temperament scale. A♭4 in particular, which is at the seventh partial (sixth overtone) is nearly always 31 cents, or about one third of a semitone, flat of the minor seventh. On the slide trombone, such deviations from intonation are corrected for by slightly adjusting the slide or by using an alternate position.[18] Although much of Western music has adopted the even-tempered scale, it has been the practice in Germany and Austria to play these notes in position, where they will have just intonation (see harmonic seventh as well for A♭4).

The next higher partials—B♭4 (a major second higher), C5 (a major second higher), D5 (a major second higher)—do not require much adjustment for even-tempered intonation, but E♭5 (a minor second higher) is almost exactly a quarter tone higher than it would be in twelve-tone equal temperament. E♭5 and F5 (a major second higher) at the next partial are very high notes; a very skilled player with a highly developed facial musculature and diaphragm can go even higher to G5, A♭5, B♭5 and beyond.

The higher in the harmonic series any two successive notes are, the closer they tend to be (as evidenced by the progressively smaller intervals noted above). A byproduct of this is the relatively few motions needed to move between notes in the higher ranges of the trombone. In the lower range, significant movement of the slide is required between positions, which becomes more exaggerated on lower pitched trombones, but for higher notes the player need only use the first four positions of the slide since the partials are closer together, allowing higher notes in alternate positions. As an example, F4 (at the bottom of the treble clef) may be played in first, fourth or sixth position on a B♭ trombone. The note E1 (or the lowest E on a standard 88-key piano keyboard) is the lowest attainable note on a 9-foot (2.7 m) B♭ tenor trombone, requiring a full 7 feet 4 inches (2.24 m) of tubing. On trombones without an F attachment, there is a gap between B♭1 (the fundamental in first position) and E2 (the first harmonic in seventh position). Skilled players can produce "falset" notes between these, but the sound is relatively weak and not usually used in performance. The addition of an F attachment allows for intermediate notes to be played with more clarity.

Pedal tones

[edit]

The B♭ pedal tone is frequently seen in commercial scoring but much less often in symphonic music, while notes below that are called for only rarely as they "become increasingly difficult to produce and insecure in quality" with A♭ or G being the bottom limit for most tenor trombonists.[18] The trombone's tubing is largely cylindrical, which inhibits the production of the fundamental as a pedal tone pitch. Instead, trombonists use the higher harmonics of the instrument to produce pedal tones, giving them a bright and hollow tone quality.[34] Some contemporary orchestral writing, movie or video game scoring, trombone ensemble and solo works will call for notes as low as a pedal C, B, or even double pedal B♭ on the bass trombone.

Glissando

[edit]The trombone is one of the few wind instruments that can produce a true glissando, by moving the slide without interrupting the airflow or sound production. Every pitch in a glissando must have the same harmonic number, and a tritone is the largest interval that can be performed as a glissando.[18]: 151

The trombone glissando can create remarkable effects, and it is used in jazz and popular music, as in the famous song "The Stripper" by David Rose and his orchestra.

'Harmonic', 'inverted', 'broken' or 'false' glissandos are those that cross one or more harmonic series, requiring a simulated or faked glissando effect.[35]

Trills

[edit]Trills, though generally simple with valves, are difficult on the slide trombone. Trills tend to be easiest and most effective higher in the harmonic series because the distance between notes is much smaller and slide movement is minimal. For example, a trill on B♭3/C4 is virtually impossible as the slide must move two positions (either 1st-to-3rd or 5th-to-3rd), however at an octave higher (B♭4/C5) the notes can both be achieved in 1st position as a lip trill. Thus, the most convincing trills tend to be above the first octave and a half of the tenor's range.[36] Trills are most commonly found in early Baroque and Classical music for the trombone as a means of ornamentation, however, some more modern pieces will call for trills as well.

Notation

[edit]Unlike most other brass instruments in an orchestral setting, the trombone is not usually considered a transposing instrument. Prior to the invention of valve systems, most brass instruments were limited to playing one overtone series at a time; altering the pitch of the instrument required manually replacing a section of tubing (called a "crook") or picking up an instrument of different length. Their parts were transposed according to which crook or length-of-instrument they used at any given time, so that a particular note on the staff always corresponded to a particular partial on the instrument. Trombones, on the other hand, have used slides since their inception. As such, they have always been fully chromatic, so no such tradition took hold, and trombone parts have always been notated at concert pitch (with one exception, discussed below). Also, it was quite common for trombones to double choir parts; reading in concert pitch meant there was no need for dedicated trombone parts. Note that while the fundamental sounding pitch (slide fully retracted) has remained quite consistent, the conceptual pitch of trombones has changed since their origin (e.g. Baroque A tenor = modern B-flat tenor).[37]

Trombone parts are typically notated in bass clef, though sometimes also written in tenor clef or alto clef. The use of alto clef is usually confined to orchestral first trombone parts, with the second trombone part written in tenor clef and the third (bass) part in bass clef. As the alto trombone declined in popularity during the 19th century, this practice was gradually abandoned and first trombone parts came to be notated in the tenor or bass clef. Some Russian and Eastern European composers wrote first and second tenor trombone parts on one alto clef staff (the German Robert Schumann was the first to do this). Examples of this practice are evident in scores by Igor Stravinsky, Sergei Prokofiev, Dmitri Shostakovich. Trombone parts in band music are nearly exclusively notated in bass clef. The rare exceptions are in contemporary works intended for high-level wind bands.

An accomplished performer today is expected to be proficient in reading parts notated in bass clef, tenor clef, alto clef, and (more rarely) treble clef in C, with the British brass-band performer expected to handle treble clef in B♭ as well.

Mutes

[edit]

A variety of mutes can be used with the trombone to alter its timbre. Many are held in place with the use of cork grips, including the straight, cup, harmon and pixie mutes. Some fit over the bell, like the bucket mute. In addition to this, mutes can be held in front of the bell and moved to cover more or less area for a wah-wah effect. Mutes used in this way include the "hat" (a metal mute shaped like a bowler hat) and plunger (which looks like, and often is, the rubber suction cup from a sink or toilet plunger). The "wah-wah" sound of a trombone with a harmon mute is featured as the voices of adults in the Peanuts cartoons.

Didactics

[edit]Several makers have begun to market compact B♭/C trombones that are especially well suited for young children learning to play the trombone who cannot reach the outer slide positions of full-length instruments. The fundamental note of the unenhanced length is C, but the short attachment that puts the instrument in B♭ has its valve open when the trigger is not depressed. While such instruments have no seventh slide position, C and B natural may be comfortably accessed on the first and second positions by using the trigger. A similar design ("Preacher model") was marketed by C.G. Conn in the 1920s, also under the Wurlitzer label. Currently, B♭/C trombones are available from many manufacturers, including German makers Günter Frost, Thein and Helmut Voigt, as well as the Yamaha Corporation.[38]

Manufacturers

[edit]Trombones in slide and valve configuration have been made by a vast array of musical instrument manufacturers. For the brass bands of the late 19th and early 20th century, prominent American manufacturers included Graves and Sons, E. G. Wright and Company, Boston Musical Instrument Company, E. A. Couturier, H. N. White Company/King Musical Instruments, J. W. York, and C.G. Conn. In the 21st century, leading mainstream manufacturers of trombones include Bach, Conn, Courtois, Edwards, Getzen, Jupiter, King, Rath, Schilke, S.E. Shires, Thein, Wessex, Willson and Yamaha.

See also

[edit]- Aequale – Composition for equal voices

- Shout band – Style of Gospel music

- Trombone repertoire – Set of available musical works for trombone

References

[edit]- ^ Michault, Pierre. Le doctrinal du temps présent , compilé par maistre Pierre Michault, secrétaire du très puissant duc de Bourgoingne (in French). p. 16. Retrieved 4 December 2018 – via Gallica, Bibliothèque nationale de France.

- ^ Guion 2010, p. 22.

- ^ Herbert 2006, p. 59.

- ^ Green, Helen (2011). "Defining the City 'Trumpeter': German Civic Identity and the Employment of Brass Instruments, c. 1500". Journal of the Royal Musical Association. doi:10.1080/02690403.2011.562714. S2CID 144303968.

- ^ Guion 1988, p. 3: "Many modern musicians prefer to use the word 'sackbut' when referring to the Baroque trombone. All other instruments in constant use since the Baroque have changed more...In response to the number of times people including musicians, have asked if the sackbut is something like a trombone, I have stopped using this misleading word.".

- ^ Lewis, Horace Monroe (May 1975). The Problem of the Tromba Da Tirarsi in the Works of J. S. Bach (PhD dissertation). Louisiana State University. doi:10.31390/gradschool_disstheses.2799. S2CID 249667805. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ Weiner, Harold. "The Soprano Trombone Hoax" (PDF). Historical Brass Society Journal. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ March, Ivan. "Albrechtsberger; Mozart, L.: Trombone Concertos". Gramophone.

- ^ "Haydn, M.: Concerto per Trombone Alto in D". Stretta Music.

- ^ "Albrechtsberger, J.G.: Concerto per trombone alto ed archi". Stretta Music.

- ^ Threasher, David. "A. Zimmermann: Symphonies (Ehrhardt)". Gramophone.

- ^ Kallai, Avishai. "Biography of Joachim Nikolas Eggert". Musicalics. Archived from the original on 8 November 2014.

- ^ Bernotas, Bob (7 September 2015). "Trombone". All About Jazz. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ Wilken, David. "The Evolution of the Jazz Trombone: Part One". trombone.org. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ a b Friedman, Jay (8 November 2003). "The German Trombone, by Jay Friedman". Jay Friedman. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ^ Campbell, Murray; Greated, Clive A.; Myers, Arnold (2004). Musical Instruments: History, Technology, and Performance of Instruments of Western Music. Oxford University Press. pp. 201–. ISBN 978-0-19-816504-0. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ^ Fischer, Henry George (1984). The Renaissance Sackbut and Its Use Today. Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 15–. ISBN 978-0-87099-412-8. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kennan, Kent; Grantham, Donald (2002). The Technique of Orchestration (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall. pp. 148–9. ISBN 978-0-13-040772-6. OCLC 1312487324. Wikidata Q113561204.

- ^ Salmon, Jane (23 June 2016). "The Soprano Trombone Project". Jane Salmon (blog). Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^ Yeo 2021, p. 10, "alto trombone".

- ^ Yeo 2021, p. 55, "F-attachment".

- ^ Yeo 2021, p. 73, "independent valves".

- ^ Guion 2010, p. 61.

- ^ "Contrabass Trombone in Bb with Double Slide". Thein Brass. Retrieved 7 March 2022. "Bb contrabass slide trombone". Miraphone eG. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ Boosey & Hawkes (1933). "Bass trombone". London: Horniman Museum & Gardens. Accession number 2004.1171. Retrieved 20 November 2024 – via Musical Instrument Museums Online.

- ^ Tanner, K (January 1999). "Larry David Minick Passes". The Cambrian (obituary). Retrieved 26 April 2024 – via The Online Trombone Journal.

- ^ Yeo 2021, p. 34, "closed wrap".

- ^ Flynn, Mike (20 June 2013). "pBone plastic trombone". Jazzwise Magazine. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ^ "Korg UK takes on distribution of Tromba". Musical Instrument Professional. 2 May 2013. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ Baines, Anthony C.; Myers, Arnold; Herbert, Trevor (2001). "Trombone". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.40576. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0.

- ^ "Model 955 Bb Flugelbone". Kanstul Musical Instruments. Retrieved 21 July 2022. "FB124 Bb Flugabone (Marching Trombone)". Wessex Tubas. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ Weiner, H. (1993). "André Braun's Gamme et Méthode pour les Trombonnes: The Earliest Modern Trombone Method Rediscovered". Historic Brass Society Journal. 5: 288–308. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ a b Guion 1988, p. 93.

- ^ Myers, Arnold (2001). Pedal Note. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Herbert 2006, p. 40.

- ^ Herbert 2006, p. 43.

- ^ Palm, Paul W. (2010). Baroque Solo and Homogeneous Ensemble Trombone Repertoire: A Lecture Recital Supporting and Demonstrating Performance at a Pitch Standard Derived from Primary Sources and Extant Instruments (DMA thesis). University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- ^ Yamaha Catalog YSL-350C with ascending Bb/C rotor. Wayback.archive-it.org

Further reading

[edit]- Adey, Christopher (1998). Orchestral Performance. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-17724-7.

- Baines, Anthony (1980). Brass Instruments: Their History and Development. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-11571-3.

- Bate, Philip (1978). The Trumpet and Trombone. London: Ernest Benn. ISBN 0-510-36413-6.

- Blatter, Alfred (1997). Instrumentation and Orchestration. Belmont: Schirmer. ISBN 0-534-25187-0.

- Blüme, Friedrich, ed. (1962). Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart. Kassel: Bärenreiter.

- Carter, Stewart (2011). The Trombone in the Renaissance: A History in Pictures and Documents. Bucina: The Historic Brass Society Series. Hillsdale, N.Y.: Pendragon Press. ISBN 978-1-57647-206-4.

- Del Mar, Norman (1983). Anatomy of the Orchestra. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-520-05062-2.

- Gregory, Robin (1973). The Trombone: The Instrument and its Music. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-08816-3.

- Guion, David (1988). The Trombone: Its History and Music, 1697–1811. Gordon and Breach. ISBN 2-88124-211-1.

- Guion, David M. (2010). A History of the Trombone. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810874459.

- Herbert, Trevor; Wallace, John, eds. (1997). The Cambridge Companion to Brass Instruments. Cambridge Companions to Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56522-7.

- Herbert, Trevor (2006). The Trombone. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300235-75-3.

- Kunitz, Hans (1959). Die Instrumentation: Teil 8 Posaune. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel. ISBN 3-7330-0009-9. This source is now considered unreliable.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Lavignac, Albert, ed. (1927). Encyclopédie de la musique et Dictionnaire du Conservatoire. Paris: Delagrave.

- Maxted, George (1970). Talking about the Trombone. London: John Baker. ISBN 0-212-98360-1.

- Montagu, Jeremy (1979). The World of Baroque & Classical Musical Instruments. New York: The Overlook Press. ISBN 0-87951-089-7.

- Montagu, Jeremy (1976). The World of Medieval & Renaissance Musical Instruments. New York: The Overlook Press. ISBN 0-87951-045-5.

- Montagu, Jeremy (1981). The World of Romantic & Modern Musical Instruments. London: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-7994-1.

- Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John, eds. (2001). "Trombone". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

- Wick, Denis (1984). Trombone Technique. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-322378-3.

- Yeo, Douglas (2021). An Illustrated Dictionary for the Modern Trombone, Tuba, and Euphonium Player. Dictionaries for the Modern Musician. Illustrator: Lennie Peterson. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-5381-5966-8. LCCN 2021020757. OCLC 1249799159. OL 34132790M. Wikidata Q111040546.

External links

[edit]- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). 1911.

- International Trombone Association

- Online Trombone Journal

- British Trombone Society

- Trombone History Timeline by Will Kimball, Professor of Trombone at Brigham Young University

- Acoustics of Brass Instruments from Music Acoustics at the University of New South Wales

- Sources for the Prescribed Sheet Music for the ABRSM practical exams

- Two Frequencies Trombone

- NPR story about trombone bands (2003)

- Overview of trombones on the MIMO (Musical Instrument Museums Online) portal

- Merriam Webster

Slide positions

[edit]- Christian E. Waage (2009). "Slide Position Chart", YeoDoug.com

- Antonio J. García. (1997). "Choosing Alternate Positions for Bebop Lines", GarciaMusic.com.

Trombone

View on GrokipediaHistory

Etymology and Origins

The word "trombone" derives from the Italian "tromba," meaning trumpet, combined with the augmentative suffix "-one," indicating "large," thus literally translating to "large trumpet." This etymological root reflects the instrument's conception as an extended, lower-pitched variant of the trumpet. The earliest documented use of the term appears in 1439 in Ferrara, Italy, in a reference to "tuba ductili…trombonus vulgo dictus," highlighting its association with a slide mechanism for pitch variation.[7][8] The trombone originated during the Renaissance as the sackbut, an evolution from the slide trumpet that emerged in Europe around the early 15th century. Likely developed in northern Italy, southern France, or Germany circa 1400, the sackbut introduced a double-slide design, allowing greater chromatic flexibility compared to its single-slide predecessor. By the mid-15th century, it had become a distinct instrument, with records indicating its integration into musical ensembles for both secular and sacred contexts.[8][1] Key early references to the trombone appear in 15th-century art and manuscripts from Italy and Germany, providing visual and documentary evidence of its emergence. In Germany, a 1403 city record from Braunschweig mentions a "bassuner" (trombone) alongside shawms, suggesting its use in civic music. Italian sources include a 1407 Siena reference to a "tuba grossa," potentially denoting the instrument, and a 1444 Florence document describing it as a "tortuous trumpet." Depictions feature in artworks such as Matteo di Giovanni's circa 1474 The Assumption of the Virgin in Asciano, Italy, showing an angel with a trombone-like instrument, and Filippino Lippi's 1488–1493 fresco in Rome's Santa Maria sopra Minerva church, offering one of the earliest reliable visual representations.[8] Unlike non-slide predecessors such as the ancient Roman buccina—a curved, valveless horn used for signaling—or early medieval trumpets limited to natural harmonics, the trombone's defining innovation was its telescoping slide, enabling semitonal adjustments and distinguishing it as a melodic brass instrument from the outset.[9][8]Medieval and Renaissance Development

The sackbut, the direct precursor to the modern trombone, developed in Northern Europe during the late 15th century as an evolution from earlier medieval slide trumpets, which featured a single slide for limited pitch variation.[10] This transition likely occurred in regions like Flanders and Germany around 1400–1500, where instrument makers refined the U-shaped slide mechanism to allow for a fuller chromatic range and greater harmonic flexibility, distinguishing it from the straighter slide trumpets of the prior era.[11] The earliest surviving instruments date to the late 16th century, such as the 1581 tenor sackbut by Anton Schnitzer of Nuremberg, confirming its establishment by then.[10] By the early 16th century, the sackbut had become integral to various musical contexts across Europe, particularly as the bass voice in alta capella ensembles—loud wind bands comprising shawms, cornetts, and sackbuts—that performed in Italy, Germany, and the Low Countries.[12] These groups accompanied civic ceremonies, such as royal baptisms and processions, and contributed to religious music in cathedrals; for instance, sackbuts were documented at Seville Cathedral in 1526 for sacred performances.[10] In civic bands like the German Stadtpfeifer and English waits (from the mid-1520s), sackbuts provided harmonic foundation for outdoor and ceremonial events, emphasizing their role in both sacred and secular polyphony.[13] Composers of the 16th century increasingly incorporated the sackbut into polyphonic works, leveraging its agile slide for expressive lines in ensemble settings. Tielman Susato, a prominent Antwerp-based trombonist and publisher active from the 1530s, featured sackbuts in his instrumental collections like the Danserye (1551), which included polyphonic dances and motets arranged for winds, reflecting the instrument's growing sophistication in Renaissance polyphony.[14] By the late 1500s, the sackbut had spread regionally from its Flemish origins to Spain—evidenced by its use in Prince Juan’s 1478 baptism—and England, where foreign players like Hans Nagle arrived in the late 15th century and it appeared in royal payments under Henry VII by 1495.[10][13] This dissemination solidified its place in diverse European musical traditions before further refinements in later periods.Baroque and Classical Periods

During the Baroque period, the trombone, often referred to as the sackbut, saw the introduction of crooks in the early 1600s to facilitate tuning adjustments and pitch standardization, typically to A or G, allowing performers to adapt to varying ensemble requirements without altering the instrument's core construction.[15][16] These removable tuning bits or slide extensions enabled precise intonation in the harmonic series, supporting the instrument's integration into polyphonic textures where exact pitch alignment was essential.[17] The trombone gained prominence in opera and sacred music during this era, exemplifying its evocative timbre for dramatic and ceremonial contexts. In Claudio Monteverdi's L'Orfeo (1607), trombones contributed to the underworld scenes, producing an eerie, resonant effect alongside continuo instruments to underscore the hero's descent into hell.[18] Similarly, in sacred works, Johann Sebastian Bach employed trombones in his early Leipzig cantatas (1724–1725), such as BWV 25 (Es ist niemand gesund am ganzen Leibe) and BWV 4 (Christ lag in Todes Banden), where they doubled vocal lines in chorales or provided independent parts to evoke solemnity and transcendence, often in motet-style movements associated with funeral or liturgical themes.[19] Entering the Classical period, the trombone's orchestral role expanded modestly in symphonic works by composers like Joseph Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, though it remained more conventional in sacred and theatrical genres. Haydn incorporated trombones in oratorios such as The Creation (1798) for reinforcing choral forces and heightening dramatic climaxes, while Mozart featured them prominently in masses and the Requiem (1791), using the instrument to double voices or punctuate supernatural elements, as in the tenor trombone solo of the "Tuba mirum."[20] These applications highlighted the trombone's capacity for both supportive blending and theatrical emphasis, bridging Baroque traditions with emerging symphonic forms. By the mid-18th century, the trombone experienced a decline in secular orchestral use, overshadowed by the rising preference for horns, which offered greater melodic flexibility and lyrical expression in evolving galant styles.[16] This shift reduced trombone parts in instrumental ensembles outside Italy, yet the instrument persisted robustly in church music, where its dignified, archaic tone continued to symbolize solemnity in masses, motets, and ceremonial pieces across Europe.[10]Romantic and 19th-Century Evolution

In the early 19th century, the trombone underwent significant technical refinements that enhanced its playability and integration into Romantic ensembles. Around the 1830s, the standard tenor trombone began shifting toward F tuning through the development of the F-attachment, a valve mechanism that allowed players to extend the instrument's range downward while maintaining Bb tuning for the primary scale. This innovation, initially applied to bass models, enabled greater chromatic flexibility for tenor instruments, addressing limitations in the slide's harmonic series. Concurrently, the invention of the knick—a bend in the outer slide—reduced the physical reach required for the seventh position, making extended low notes more accessible without compromising tone production.[21] Romantic composers capitalized on these advancements to elevate the trombone's role beyond its Classical-era doubling functions. Hector Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique (1830) marked one of the earliest orchestral works to assign the trombones prominent, independent melodic lines, particularly in the alto register, demanding expressive phrasing and dynamic contrast that showcased the instrument's lyrical potential. Richard Wagner further expanded its chromatic capabilities in his operas, employing a standard trio of alto, tenor, and bass trombones augmented by contrabass models in works like the Ring Cycle (composed 1848–1874), where they provided dramatic harmonic depth and reinforced leitmotifs with bold, unified brass chorales. These compositional demands pushed instrument makers to refine bore sizes and slide mechanisms for improved intonation across the expanded range.[21][22][23] The trombone's prominence also surged in 19th-century wind bands and military music, reflecting broader cultural shifts toward public spectacles. In France, post-Revolutionary military ensembles routinely featured trombones for their penetrating tone in outdoor settings, influencing composers like Berlioz who drew from band traditions for orchestral color. Similarly, in the United States, Civil War-era brass bands adopted the instrument as a core element, with tenor and bass models providing harmonic foundation in marches and signals, as seen in Union and Confederate regimental bands. This band context popularized the trombone among amateur musicians and solidified its association with national identity and ceremony.[24][25] Pedagogical resources emerged to support these evolutions, emphasizing slide position mastery for precise intonation and agility. In the 1830s and 1840s, method books like Antoine Dieppo's Méthode complète pour le trombone (1836) and Robert Müller's early studies (circa 1845) focused on systematic position exercises, lip slurs, and scalar patterns to develop the technical facility required for Romantic repertoire. These texts, often tailored to the emerging F-attachment instruments, laid the groundwork for standardized teaching that prioritized clean slide technique over rudimentary tone production.[21]20th-Century Innovations

The 20th century marked a period of significant mechanical and musical advancements for the trombone, particularly in valve systems that enhanced playability and range for bass models. In the early 1910s, French manufacturer Lefevre introduced tenor and bass trombones with F-attachments featuring static valves (Stellventil), allowing players to access lower registers more efficiently without relying solely on extended slides; this design was notably used by trombonist Joannés Rochut in the 1920s and 1930s.[26] By the 1930s, further progress came with the development of double-valve systems, as F.E. Olds produced the first dependent double-valve bass trombone in 1938 (later the Model S-23), which combined F and E-flat triggers in a stacked configuration to improve chromatic agility and transition speed compared to single rotary valves.[26] These innovations addressed limitations in traditional rotary valves by reducing resistance and enabling quicker shifts, making bass trombones more suitable for demanding orchestral repertoire.[26] The rise of electrical recording technology in the mid-1920s profoundly influenced trombone tone production and standardization, as the shift from acoustic to microphone-based methods allowed for greater fidelity and balance in ensemble recordings. Prior to 1925, acoustic recording horns favored louder, brighter brass tones to project over the mechanical limitations, often requiring trombonists to position farther from the horn, resulting in a distant and thinner sound.[27] After the introduction of electrical processes by companies like Western Electric, recordings captured subtler dynamics and timbres, prompting performers and manufacturers to refine trombone designs toward a more consistent, resonant tone suited to both live and recorded media; this standardization emphasized even scaling and reduced mouthpiece variability to achieve reliable projection on disc.[28][29] Trombone usage expanded dramatically in film scores and avant-garde compositions during the century, bridging classical traditions with emerging media and experimental forms. In Hollywood, composers like Franz Waxman integrated the trombone for dramatic effect, employing muted horns and trombones to evoke foreboding in scores such as The Virgin Queen (1955), where low brass underscored tense narrative moments.[30] Similarly, in avant-garde music, Karlheinz Stockhausen composed works exploiting the instrument's extended techniques, including In Freundschaft (1977/1982) for solo trombone, which explores multiphonics and feedback integration to push timbral boundaries.[31] These applications highlighted the trombone's versatility in creating atmospheric depth in film and innovative sonorities in electronic-influenced pieces like Signale zur Invasion (1992–1993) for trombone and electronics.[31] Post-World War II developments focused on professional-grade instruments, with Vincent Bach introducing refined Stradivarius models in the 1950s that became staples for orchestral players. In 1956, Bach crafted a custom dependent double-valve bass trombone for trombonist Lawrence Weinman, incorporating ergonomic triggers and balanced weight distribution to facilitate extended playing sessions.[26] By 1961, this evolved into the production Model 50B2, featuring a .547-inch bore and 9.5-inch bell for enhanced projection and tonal warmth, which quickly gained adoption among symphony musicians for its reliability in large ensembles.[26] These models exemplified the era's emphasis on precision manufacturing, drawing from Stradivarius-inspired proportions to standardize professional performance standards.Contemporary Developments

In the 21st century, the trombone has seen innovative integrations of electronic technologies, enabling hybrid acoustic-electronic performances. Prototypes like the Double Slide Controller, developed in 2010, emulate the trombone's slide mechanism to function as a MIDI controller, allowing performers to trigger synthesized sounds and effects in real-time.[32] Similarly, the eBone project, initiated around 2019, augments the traditional trombone with sensors and software for blending live playing with digital processing, expanding expressive possibilities in contemporary compositions.[33] These developments, emerging prominently in the 2010s, facilitate novel timbres and interactions with software synthesizers, influencing experimental music and multimedia performances.[34] Advancements in additive manufacturing have revolutionized trombone accessories, particularly since the mid-2010s, with 3D printing enabling customized mouthpieces and slides tailored to individual ergonomics. A 2021 study demonstrated that 3D-printed trombone mouthpieces produced via fused deposition modeling (FDM) and stereolithography (SLA) achieve sound characteristics comparable to conventionally machined brass ones, with SLA versions offering superior intonation and projection.[35] Commercial offerings, such as those from specialized printers, allow musicians to iterate designs for comfort and response, reducing production waste and democratizing access to personalized gear.[36] This technology has gained traction among professionals and educators, fostering innovation in performance technique and instrument adaptation. As of 2025, advances in 3D printing and materials science continue to improve slide precision and tonal quality.[37] The trombone's cultural role has expanded in global fusion genres and media soundtracks, where its versatile timbre enhances dramatic and rhythmic elements. In video game music, orchestral scores increasingly feature trombones for epic and tension-building motifs, as seen in collections adapting themes from titles like The Legend of Zelda and Final Fantasy that incorporate brass sections. Composers like Hans Zimmer, known for brass-heavy film scores such as Inception (2010) with its prominent trombone ensembles, have influenced game audio design, promoting the instrument's use in hybrid orchestral-electronic hybrids across global styles.[38] Sustainability initiatives in trombone manufacturing have accelerated in the 2020s, driven by eco-friendly materials and processes to mitigate environmental impact. Companies like pBone produce lightweight, recyclable ABS plastic trombones that achieve carbon-neutral status through offsetting emissions and durable design, reducing resource demands compared to traditional brass models.[39] Yamaha has adopted bioplastics, lead-free solders, and recycled packaging in its brass instrument production, aligning with broader industry shifts toward responsible sourcing.[40] Additionally, innovations like carbon-fiber components in models from Butler Trombone lighten instruments while potentially lowering material use, supporting ergonomic and ecological goals.[41]Design and Construction

Core Components

The trombone is classified as an end-blown lip-reed aerophone, characterized by a telescoping slide mechanism that allows the player to alter pitch by adjusting the length of the instrument's tubing, producing notes from the harmonic series through lip vibration and air column resonance.[2] This design enables the performer to extend or retract the slide to change the effective tube length, thereby selecting specific harmonics or overtones from the fundamental frequency.[42] The primary structural components of the trombone include the outer slide, which forms a U-shaped outer tube connected to the bell section; the inner slide, a straight dual-tube assembly that telescopes within the outer slide for smooth extension; the bell, the flared terminus that amplifies and projects the sound; and the leadpipe, the initial curved tube that receives the mouthpiece and directs airflow into the slide.[43] These elements work in concert to form the instrument's core framework, with the slide assembly enabling precise pitch control and the bell shaping the output timbre.[43] Acoustically, the trombone operates on the principle that adjusting the slide length modifies the fundamental frequency of the air column, allowing access to a series of partials or overtones that constitute the harmonic series, typically starting from a low fundamental like Bb1 in the fully extended position.[42][44] This length variation tunes the resonances to match the desired pitches, with the player's embouchure selecting higher harmonics through increased lip tension.[42] Basic bore sizes, which refer to the inner diameter of the tubing, typically measure .500 inches for standard tenor trombones, providing a balanced resistance and brighter timbre suitable for agile playing, while bass trombones often feature a 0.562-inch bore for enhanced volume and a fuller, darker tone.[45][46] These dimensions influence the instrument's overall timbre by affecting airflow resistance and harmonic projection, with narrower bores yielding a more focused sound and wider ones promoting richer overtones.[45]Materials and Manufacturing