Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

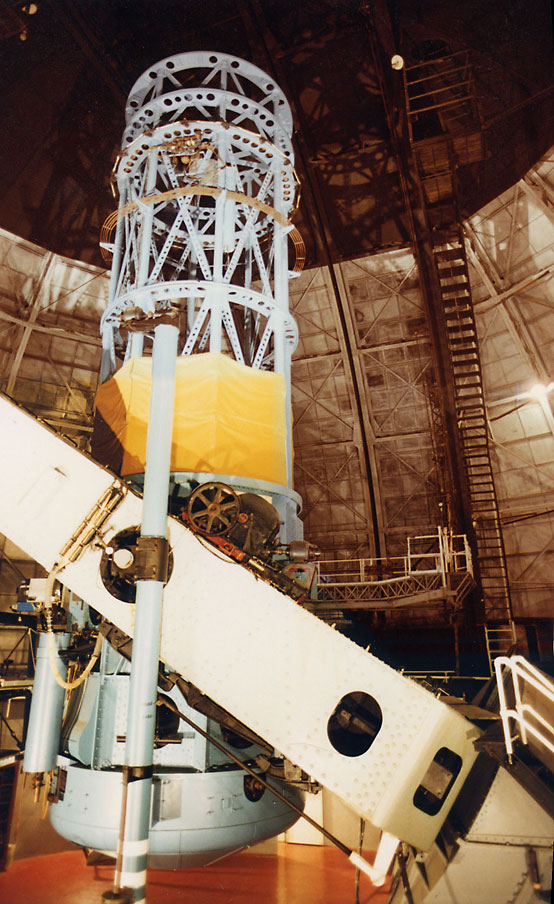

Telescope

View on Wikipedia

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, absorption, or reflection of electromagnetic radiation.[1] Originally, it was an optical instrument using lenses, curved mirrors, or a combination of both to observe distant objects – an optical telescope. Nowadays, the word "telescope" is defined as a wide range of instruments capable of detecting different regions of the electromagnetic spectrum, and in some cases other types of detectors.

The first known practical telescopes were refracting telescopes with glass lenses and were invented in the Netherlands at the beginning of the 17th century. They were used for both terrestrial applications and astronomy.

The reflecting telescope, which uses mirrors to collect and focus light, was invented within a few decades of the first refracting telescope.

In the 20th century, many new types of telescopes were invented, including radio telescopes in the 1930s and infrared telescopes in the 1960s.

Etymology

[edit]The word telescope was coined in 1611 by the Greek mathematician Giovanni Demisiani for one of Galileo Galilei's instruments presented at a banquet at the Accademia dei Lincei.[2][3] In the Starry Messenger, Galileo had used the Latin term perspicillum. The root of the word is from the Ancient Greek τῆλε, tele 'far' and σκοπεῖν, skopein 'to look or see'; τηλεσκόπος, teleskopos 'far-seeing'.[4]

History

[edit]

The earliest existing record of a telescope was a 1608 patent submitted to the government in the Netherlands by Middelburg spectacle maker Hans Lipperhey for a refracting telescope.[6] The actual inventor is unknown but word of it spread through Europe. Galileo heard about it and, in 1609, built his own version, and made his telescopic observations of celestial objects.[7][8]

The idea that the objective, or light-gathering element, could be a mirror instead of a lens was being investigated soon after the invention of the refracting telescope.[9] The potential advantages of using parabolic mirrors—reduction of spherical aberration and no chromatic aberration—led to many proposed designs and several attempts to build reflecting telescopes.[10] In 1668, Isaac Newton built the first practical reflecting telescope, of a design which now bears his name, the Newtonian reflector.[11]

The invention of the achromatic lens in 1733 partially corrected color aberrations present in the simple lens[12] and enabled the construction of shorter, more functional refracting telescopes.[13] Reflecting telescopes, though not limited by the color problems seen in refractors, were hampered by the use of fast tarnishing speculum metal mirrors employed during the 18th and early 19th century—a problem alleviated by the introduction of silver coated glass mirrors in 1857, and aluminized mirrors in 1932.[14] The maximum physical size limit for refracting telescopes is about 1 meter (39 inches), dictating that the vast majority of large optical researching telescopes built since the turn of the 20th century have been reflectors. The largest reflecting telescopes currently have objectives larger than 10 meters (33 feet), and work is underway on several 30–40m designs.[15]

The 20th century also saw the development of telescopes that worked in a wide range of wavelengths from radio to gamma-rays. The first purpose-built radio telescope went into operation in 1937. Since then, a large variety of complex astronomical instruments have been developed.

In the late 2010s, smart telescopes[16] democratize access to the night sky observation[17]. They simplify setup, automate object tracking, and deliver clear, processed images to users, including those in light-polluted environments. Smart telescopes don't have an eyepiece like a traditional telescope. They capture multiple images of an object, stacking the images in real time to display a clear view.

In space

[edit]Since the atmosphere is opaque for most of the electromagnetic spectrum, only a few bands can be observed from the Earth's surface. These bands are visible – near-infrared and a portion of the radio-wave part of the spectrum.[18] For this reason there are no X-ray or far-infrared ground-based telescopes as these have to be observed from orbit. Even if a wavelength is observable from the ground, it might still be advantageous to place a telescope on a satellite due to issues such as clouds, astronomical seeing and light pollution.[19]

The disadvantages of launching a space telescope include cost, size, maintainability and upgradability.[20]

Some examples of space telescopes from NASA are the Hubble Space Telescope that detects visible light, ultraviolet, and near-infrared wavelengths, the Spitzer Space Telescope that detects infrared radiation, and the Kepler Space Telescope that discovered thousands of exoplanets.[21] The latest telescope that was launched was the James Webb Space Telescope on December 25, 2021, in Kourou, French Guiana. The Webb telescope detects infrared light.[22]

By electromagnetic spectrum

[edit]

The name "telescope" covers a wide range of instruments. Most detect electromagnetic radiation, but there are major differences in how astronomers must go about collecting light (electromagnetic radiation) in different frequency bands.

As wavelengths become longer, it becomes easier to use antenna technology to interact with electromagnetic radiation (although it is possible to make very tiny antenna). The near-infrared can be collected much like visible light; however, in the far-infrared and submillimetre range, telescopes can operate more like a radio telescope. For example, the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope observes from wavelengths from 3 μm (0.003 mm) to 2000 μm (2 mm), but uses a parabolic aluminum antenna.[23] On the other hand, the Spitzer Space Telescope, observing from about 3 μm (0.003 mm) to 180 μm (0.18 mm) uses a mirror (reflecting optics). Also using reflecting optics, the Hubble Space Telescope with Wide Field Camera 3 can observe in the frequency range from about 0.2 μm (0.0002 mm) to 1.7 μm (0.0017 mm) (from ultra-violet to infrared light).[24]

With photons of the shorter wavelengths, with the higher frequencies, glancing-incident optics, rather than fully reflecting optics are used. Telescopes such as TRACE and SOHO use special mirrors to reflect extreme ultraviolet, producing higher resolution and brighter images than are otherwise possible. A larger aperture does not just mean that more light is collected, it also enables a finer angular resolution.

Telescopes may also be classified by location: ground telescope, space telescope, or flying telescope. They may also be classified by whether they are operated by professional astronomers or amateur astronomers. A vehicle or permanent campus containing one or more telescopes or other instruments is called an observatory.

Radio and submillimeter

[edit]

Radio telescopes are directional radio antennas that typically employ a large dish to collect radio waves. The dishes are sometimes constructed of a conductive wire mesh whose openings are smaller than the wavelength being observed.

Unlike an optical telescope, which produces a magnified image of the patch of sky being observed, a traditional radio telescope dish contains a single receiver and records a single time-varying signal characteristic of the observed region; this signal may be sampled at various frequencies. In some newer radio telescope designs, a single dish contains an array of several receivers; this is known as a focal-plane array.

By collecting and correlating signals simultaneously received by several dishes, high-resolution images can be computed. Such multi-dish arrays are known as astronomical interferometers and the technique is called aperture synthesis. The 'virtual' apertures of these arrays are similar in size to the distance between the telescopes. As of 2005, the record array size is many times the diameter of the Earth – using space-based very-long-baseline interferometry (VLBI) telescopes such as the Japanese HALCA (Highly Advanced Laboratory for Communications and Astronomy) VSOP (VLBI Space Observatory Program) satellite.[25]

Aperture synthesis is now also being applied to optical telescopes using optical interferometers (arrays of optical telescopes) and aperture masking interferometry at single reflecting telescopes.

Radio telescopes are also used to collect microwave radiation, which has the advantage of being able to pass through the atmosphere and interstellar gas and dust clouds.

Some radio telescopes such as the Allen Telescope Array are used by programs such as SETI[26] and the Arecibo Observatory to search for extraterrestrial life.[27][28]

Infrared

[edit]Visible light

[edit]

An optical telescope gathers and focuses light mainly from the visible part of the electromagnetic spectrum.[29] Optical telescopes increase the apparent angular size of distant objects as well as their apparent brightness. For the image to be observed, photographed, studied, and sent to a computer, telescopes work by employing one or more curved optical elements, usually made from glass lenses and/or mirrors, to gather light and other electromagnetic radiation to bring that light or radiation to a focal point. Optical telescopes are used for astronomy and in many non-astronomical instruments, including: theodolites (including transits), spotting scopes, monoculars, binoculars, camera lenses, and spyglasses. There are three main optical types:

- The refracting telescope which uses lenses to form an image.[30]

- The reflecting telescope which uses an arrangement of mirrors to form an image.[31]

- The catadioptric telescope which uses mirrors combined with lenses to form an image.

A Fresnel imager is a proposed ultra-lightweight design for a space telescope that uses a Fresnel lens to focus light.[32][33]

Beyond these basic optical types there are many sub-types of varying optical design classified by the task they perform such as astrographs,[34] comet seekers[35] and solar telescopes.[36]

Ultraviolet

[edit]Most ultraviolet light is absorbed by the Earth's atmosphere, so observations at these wavelengths must be performed from the upper atmosphere or from space.[37][38]

X-ray

[edit]

X-rays are much harder to collect and focus than electromagnetic radiation of longer wavelengths. X-ray telescopes can use X-ray optics, such as Wolter telescopes composed of ring-shaped 'glancing' mirrors made of heavy metals that are able to reflect the rays just a few degrees. The mirrors are usually a section of a rotated parabola and a hyperbola, or ellipse. In 1952, Hans Wolter outlined 3 ways a telescope could be built using only this kind of mirror.[39][40] Examples of space observatories using this type of telescope are the Einstein Observatory,[41] ROSAT,[42] and the Chandra X-ray Observatory.[43][44] In 2012 the NuSTAR X-ray Telescope was launched which uses Wolter telescope design optics at the end of a long deployable mast to enable photon energies of 79 keV.[45][46]

Gamma ray

[edit]

Higher energy X-ray and gamma ray telescopes refrain from focusing completely and use coded aperture masks: the patterns of the shadow the mask creates can be reconstructed to form an image.

X-ray and Gamma-ray telescopes are usually installed on high-flying balloons[47][48] or Earth-orbiting satellites since the Earth's atmosphere is opaque to this part of the electromagnetic spectrum. An example of this type of telescope is the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope which was launched in June 2008.[49][50]

The detection of very high energy gamma rays, with shorter wavelength and higher frequency than regular gamma rays, requires further specialization. Such detections can be made either with the Imaging Atmospheric Cherenkov Telescopes (IACTs) or with Water Cherenkov Detectors (WCDs). Examples of IACTs are H.E.S.S.[51] and VERITAS[52][53] with the next-generation gamma-ray telescope, the Cherenkov Telescope Array (CTA), currently under construction. HAWC and LHAASO are examples of gamma-ray detectors based on the Water Cherenkov Detectors.

A discovery in 2012 may allow focusing gamma-ray telescopes.[54] At photon energies greater than 700 keV, the index of refraction starts to increase again.[54]

Lists of telescopes

[edit]- List of optical telescopes

- List of largest optical reflecting telescopes

- List of largest optical refracting telescopes

- List of largest optical telescopes historically

- List of radio telescopes

- List of solar telescopes

- List of space observatories

- List of telescope parts and construction

- List of telescope types

See also

[edit]- Airmass

- Amateur telescope making

- Angular resolution

- ASCOM open standards for computer control of telescopes

- Bahtinov mask

- Binoculars

- Bioptic telescope

- Carey mask

- Dew shield

- Dynameter

- f-number

- First light

- Hartmann mask

- Keyhole problem

- Microscope

- Planetariums

- Remote Telescope Markup Language

- Robotic telescope

- Timeline of telescope technology

- Timeline of telescopes, observatories, and observing technology

References

[edit]- ^ "Telescope". The American Heritage Dictionary. Archived from the original on 11 March 2020. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ Sobel (2000, p.43), Drake (1978, p.196)

- ^ Rosen, Edward, The Naming of the Telescope (1947)

- ^ Jack, Albert (2015). They Laughed at Galileo: How the Great Inventors Proved Their Critics Wrong. Skyhorse. ISBN 978-1629147581.

- ^ Helden, Albert Van; Dupré, Sven; Gent, Rob van (2010). The Origins of the Telescope. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-90-6984-615-6. OCLC 760914120. Retrieved 15 April 2025.

- ^ galileo.rice.edu The Galileo Project > Science > The Telescope by Al Van Helden: The Hague discussed the patent applications first of Hans Lipperhey of Middelburg, and then of Archived 23 June 2004 at the Wayback MachineJacob Metius of Alkmaar... another citizen of Middelburg, Zacharias Janssen is sometimes associated with the invention

- ^ "NASA – Telescope History". www.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 14 February 2021. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- ^ Loker, Aleck (20 November 2017). Profiles in Colonial History. Aleck Loker. ISBN 978-1-928874-16-4. Archived from the original on 27 May 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2015 – via Google Books.

- ^ Watson, Fred (20 November 2017). Stargazer: The Life and Times of the Telescope. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74176-392-8. Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 21 November 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Attempts by Niccolò Zucchi and James Gregory and theoretical designs by Bonaventura Cavalieri, Marin Mersenne, and Gregory among others

- ^ Hall, A. Rupert (1992). Isaac Newton: Adventurer in Thought. Cambridge University Press. p. 67. ISBN 9780521566698.

- ^ "Chester Moor Hall". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 17 May 2016. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- ^ Richard Pearson, The History of Astronomy, Astro Publication (2020), p. 281.

- ^ Bakich, Michael E. (10 July 2003). "Chapter Two: Equipment". The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Amateur Astronomy (PDF). Cambridge University Press. p. 33. ISBN 9780521812986. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2008.

- ^ Tate, Karl (30 August 2013). "World's Largest Reflecting Telescopes Explained (Infographic)". Space.com. Archived from the original on 20 August 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ "Best smart telescopes 2025". Space.com. 7 February 2024.

- ^ "Smart telescope users join forces to photograph the interstellar comet moving through our Solar System". 15 July 2025.

- ^ Stierwalt, Everyday Einstein Sabrina. "Why Do We Put Telescopes in Space?". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 20 August 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ Siegel, Ethan. "5 Reasons Why Astronomy Is Better From The Ground Than In Space". Forbes. Archived from the original on 20 August 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ Siegel, Ethan. "This Is Why We Can't Just Do All Of Our Astronomy From Space". Forbes. Archived from the original on 20 August 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ Brennan, Pat; NASA (26 July 2022). "Missons/Discovery". NASA's exoplanet-hunting space telescopes. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ Space Telescope Science Institution; NASA (19 July 2023). "Quick Facts". Webb Space Telescope. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ ASTROLab du parc national du Mont-Mégantic (January 2016). "The James-Clerk-Maxwell Observatory". Canada under the stars. Archived from the original on 5 February 2011. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- ^ "Hubble's Instruments: WFC3 – Wide Field Camera 3". www.spacetelescope.org. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- ^ "Observatories Across the Electromagnetic Spectrum". imagine.gsfc.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 20 August 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ Dalton, Rex (1 August 2000). "Microsoft moguls back search for ET intelligence". Nature. 406 (6796): 551. doi:10.1038/35020722. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 10949267. S2CID 4415108.

- ^ Tarter, Jill (September 2001). "The Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI)". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 39 (1): 511–548. Bibcode:2001ARA&A..39..511T. doi:10.1146/annurev.astro.39.1.511. ISSN 0066-4146. S2CID 261531924. Archived from the original on 20 August 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ Nola Taylor Tillman (2 August 2016). "SETI & the Search for Extraterrestrial Life". Space.com. Archived from the original on 17 August 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ Jones, Barrie W. (2 September 2008). The Search for Life Continued: Planets Around Other Stars. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-387-76559-4. Archived from the original on 8 March 2020. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- ^ Lauren Cox (26 October 2021). "Who Invented the Telescope?". Space.com. Archived from the original on 16 July 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ Rupert, Charles G. (1918). "1918PA.....26..525R Page 525". Popular Astronomy. 26: 525. Bibcode:1918PA.....26..525R. Archived from the original on 20 August 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ "Telescope could focus light without a mirror or lens". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 20 August 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ Koechlin, L.; Serre, D.; Duchon, P. (1 November 2005). "High resolution imaging with Fresnel interferometric arrays: suitability for exoplanet detection". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 443 (2): 709–720. arXiv:astro-ph/0510383. Bibcode:2005A&A...443..709K. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20052880. ISSN 0004-6361. S2CID 119423063. Archived from the original on 3 December 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ "Celestron Rowe-Ackermann Schmidt Astrograph – Astronomy Now". Archived from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ "Telescope (Comet Seeker)". Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 20 August 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ Stenflo, J. O. (1 January 2001). "Limitations and Opportunities for the Diagnostics of Solar and Stellar Magnetic Fields". Magnetic Fields Across the Hertzsprung-Russell Diagram. 248: 639. Bibcode:2001ASPC..248..639S. Archived from the original on 20 August 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ Allen, C. W. (2000). Allen's astrophysical quantities. Arthur N. Cox (4th ed.). New York: AIP Press. ISBN 0-387-98746-0. OCLC 40473741.

- ^ Ortiz, Roberto; Guerrero, Martín A. (28 June 2016). "Ultraviolet emission from main-sequence companions of AGB stars". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 461 (3): 3036–3046. arXiv:1606.09086. Bibcode:2016MNRAS.461.3036O. doi:10.1093/mnras/stw1547. ISSN 0035-8711.

- ^ Wolter, H. (1952), "Glancing Incidence Mirror Systems as Imaging Optics for X-rays", Annalen der Physik, 10 (1): 94–114, Bibcode:1952AnP...445...94W, doi:10.1002/andp.19524450108.

- ^ Wolter, H. (1952), "Verallgemeinerte Schwarzschildsche Spiegelsysteme streifender Reflexion als Optiken für Röntgenstrahlen", Annalen der Physik, 10 (4–5): 286–295, Bibcode:1952AnP...445..286W, doi:10.1002/andp.19524450410.

- ^ Giacconi, R.; Branduardi, G.; Briel, U.; Epstein, A.; Fabricant, D.; Feigelson, E.; Forman, W.; Gorenstein, P.; Grindlay, J.; Gursky, H.; Harnden, F. R.; Henry, J. P.; Jones, C.; Kellogg, E.; Koch, D. (June 1979). "The Einstein /HEAO 2/ X-ray Observatory". The Astrophysical Journal. 230: 540. Bibcode:1979ApJ...230..540G. doi:10.1086/157110. ISSN 0004-637X. S2CID 120943949.

- ^ "DLR – About the ROSAT mission". DLRARTICLE DLR Portal. Archived from the original on 16 August 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ Schwartz, Daniel A. (1 August 2004). "The development and scientific impact of the chandra x-ray observatory". International Journal of Modern Physics D. 13 (7): 1239–1247. arXiv:astro-ph/0402275. Bibcode:2004IJMPD..13.1239S. doi:10.1142/S0218271804005377. ISSN 0218-2718. S2CID 858689. Archived from the original on 20 August 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ Madejski, Greg (2006). "Recent and Future Observations in the X-ray and Gamma-ray Bands: Chandra, Suzaku, GLAST, and NuSTAR". AIP Conference Proceedings. 801 (1): 21–30. arXiv:astro-ph/0512012. Bibcode:2005AIPC..801...21M. doi:10.1063/1.2141828. ISSN 0094-243X. S2CID 14601312. Archived from the original on 28 April 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ "NuStar: Instrumentation: Optics". Archived from the original on 1 November 2010.

- ^ Hailey, Charles J.; An, HongJun; Blaedel, Kenneth L.; Brejnholt, Nicolai F.; Christensen, Finn E.; Craig, William W.; Decker, Todd A.; Doll, Melanie; Gum, Jeff; Koglin, Jason E.; Jensen, Carsten P.; Hale, Layton; Mori, Kaya; Pivovaroff, Michael J.; Sharpe, Marton (29 July 2010). Arnaud, Monique; Murray, Stephen S; Takahashi, Tadayuki (eds.). "The Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array (NuSTAR): optics overview and current status". Space Telescopes and Instrumentation 2010: Ultraviolet to Gamma Ray. 7732. SPIE: 197–209. Bibcode:2010SPIE.7732E..0TH. doi:10.1117/12.857654. S2CID 121831705.

- ^ Braga, João; D’Amico, Flavio; Avila, Manuel A. C.; Penacchioni, Ana V.; Sacahui, J. Rodrigo; Santiago, Valdivino A. de; Mattiello-Francisco, Fátima; Strauss, Cesar; Fialho, Márcio A. A. (1 August 2015). "The protoMIRAX hard X-ray imaging balloon experiment". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 580: A108. arXiv:1505.06631. Bibcode:2015A&A...580A.108B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201526343. ISSN 0004-6361. S2CID 119222297. Archived from the original on 29 January 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ Brett Tingley (13 July 2022). "Balloon-borne telescope lifts off to study black holes and neutron stars". Space.com. Archived from the original on 20 August 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ Atwood, W. B.; Abdo, A. A.; Ackermann, M.; Althouse, W.; Anderson, B.; Axelsson, M.; Baldini, L.; Ballet, J.; Band, D. L.; Barbiellini, G.; Bartelt, J.; Bastieri, D.; Baughman, B. M.; Bechtol, K.; Bédérède, D. (1 June 2009). "The Large Area Telescope on Thefermi Gamma-Ray Space Telescopemission". The Astrophysical Journal. 697 (2): 1071–1102. arXiv:0902.1089. Bibcode:2009ApJ...697.1071A. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/697/2/1071. ISSN 0004-637X. S2CID 26361978. Archived from the original on 20 August 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ Ackermann, M.; Ajello, M.; Baldini, L.; Ballet, J.; Barbiellini, G.; Bastieri, D.; Bellazzini, R.; Bissaldi, E.; Bloom, E. D.; Bonino, R.; Bottacini, E.; Brandt, T. J.; Bregeon, J.; Bruel, P.; Buehler, R. (13 July 2017). "Search for Extended Sources in the Galactic Plane Using Six Years ofFermi-Large Area Telescope Pass 8 Data above 10 GeV". The Astrophysical Journal. 843 (2): 139. arXiv:1702.00476. Bibcode:2017ApJ...843..139A. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/aa775a. ISSN 1538-4357. S2CID 119187437.

- ^ Aharonian, F.; Akhperjanian, A. G.; Bazer-Bachi, A. R.; Beilicke, M.; Benbow, W.; Berge, D.; Bernlöhr, K.; Boisson, C.; Bolz, O.; Borrel, V.; Braun, I.; Breitling, F.; Brown, A. M.; Bühler, R.; Büsching, I. (1 October 2006). "Observations of the Crab nebula with HESS". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 457 (3): 899–915. arXiv:astro-ph/0607333. Bibcode:2006A&A...457..899A. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20065351. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ^ Krennrich, F.; Bond, I. H.; Boyle, P. J.; Bradbury, S. M.; Buckley, J. H.; Carter-Lewis, D.; Celik, O.; Cui, W.; Daniel, M.; D'Vali, M.; de la Calle Perez, I.; Duke, C.; Falcone, A.; Fegan, D. J.; Fegan, S. J. (1 April 2004). "VERITAS: the Very Energetic Radiation Imaging Telescope Array System". New Astronomy Reviews. 2nd VERITAS Symposium on the Astrophysics of Extragalactic Sources. 48 (5): 345–349. Bibcode:2004NewAR..48..345K. doi:10.1016/j.newar.2003.12.050. hdl:10379/9414. ISSN 1387-6473.

- ^ Weekes, T. C.; Cawley, M. F.; Fegan, D. J.; Gibbs, K. G.; Hillas, A. M.; Kowk, P. W.; Lamb, R. C.; Lewis, D. A.; Macomb, D.; Porter, N. A.; Reynolds, P. T.; Vacanti, G. (1 July 1989). "Observation of TeV Gamma Rays from the Crab Nebula Using the Atmospheric Cerenkov Imaging Technique". The Astrophysical Journal. 342: 379. Bibcode:1989ApJ...342..379W. doi:10.1086/167599. ISSN 0004-637X. S2CID 119424766. Archived from the original on 11 April 2023. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ a b "Silicon 'prism' bends gamma rays – Physics World". 9 May 2012. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

Further reading

[edit]- Elliott, Robert S. (1966), Electromagnetics, McGraw-Hill

- King, Henry C. (1979). The history of the telescope. H. Spencer Jones. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-23893-8. OCLC 6025190.

- Pasachoff, Jay M. (1981). Contemporary astronomy (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders College Pub. ISBN 0-03-057861-2. OCLC 7734917.

- Rashed, Roshdi; Morelon, Régis (1996), Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science, vol. 1 & 3, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-12410-2

- Sabra, A. I.; Hogendijk, J. P. (2003). The Enterprise of Science in Islam: New Perspectives. MIT Press. pp. 85–118. ISBN 978-0-262-19482-2.

- Wade, Nicholas J.; Finger, Stanley (2001), "The eye as an optical instrument: from camera obscura to Helmholtz's perspective", Perception, 30 (10): 1157–1177, doi:10.1068/p3210, PMID 11721819, S2CID 8185797

- Watson, Fred (2007). Stargazer : the life and times of the telescope. Crows Nest, New South Wales, Australia: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74176-392-8. OCLC 173996168.

External links

[edit]- Galileo to Gamma Cephei – The History of the Telescope. Archived 8 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- The Galileo Project – The Telescope by Al Van Helden

- "The First Telescopes". Part of an exhibit from Cosmic Journey: A History of Scientific Cosmology. Archived 9 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine by the American Institute of Physics

- Taylor, Harold Dennis; Gill, David (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). pp. 557–573.

- Outside the Optical: Other Kinds of Telescopes

- Gray, Meghan; Merrifield, Michael (2009). "Telescope Diameter". Sixty Symbols. Brady Haran for the University of Nottingham.

Telescope

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Etymology

A telescope is an optical instrument that employs lenses, mirrors, or electronic detectors to observe remote objects by collecting electromagnetic radiation (EMR) from across the spectrum, including visible light, ultraviolet, infrared, X-rays, and gamma rays, and focusing it to form magnified images or enhanced data. This process increases the apparent angular size of distant sources or improves their resolving power, allowing detailed study of otherwise faint or minuscule features.[1] The word "telescope" originates from the Greek roots tēle- ("far," from the Proto-Indo-European root *kwel- meaning "to revolve or move round") and skopein ("to look or see," from *spek- "to observe"), literally meaning "far-seeing." It was coined in 1611 by the Greek mathematician Giovanni Demisiani during a banquet at the Accademia dei Lincei to name one of Galileo Galilei's instruments, distinguishing it from the "microscope," which examines nearby objects. The term entered English via Italian telescopio (used by Galileo in 1611) and Latin telescopium (Kepler, 1613).[10][11] Telescopes serve primarily in astronomy to investigate celestial bodies, gathering EMR from stars, galaxies, and cosmic phenomena that would be invisible to the naked eye, though they also enable terrestrial uses like surveillance and surveying. Their effectiveness hinges on resolving power—the capacity to separate closely spaced objects—rather than magnifying power, which merely enlarges the image but cannot reveal details beyond the resolution limit. Resolving power is constrained by diffraction, while magnification is achieved by adjusting focal lengths and is secondary to light-gathering ability and detail clarity.[12] The fundamental limit to resolving power is quantified by the Rayleigh criterion, which defines the minimum angular separation (in radians) between two point sources as just resolvable when the central maximum of one diffraction pattern falls on the first minimum of the other: Here, is the wavelength of the EMR, and is the aperture diameter. This formula derives from the Airy diffraction pattern for a circular aperture, where the first minimum occurs at an angle determined by the Bessel function of the first kind, yielding the 1.22 factor for equal-intensity sources. Shorter wavelengths or larger apertures reduce , enhancing resolution; for visible light ( nm), a 1-meter telescope achieves arcseconds. Established by Lord Rayleigh in 1879, this criterion underscores why aperture size is paramount in telescope performance.[13]Basic Components and Principles

A telescope's primary function relies on its core optical and mechanical components, which work together to collect, focus, and magnify incoming electromagnetic radiation. The objective serves as the main light-gathering element, either a lens in refracting telescopes or a mirror in reflecting designs, capturing parallel rays from distant objects and converging them to form a real image at its focal plane.[14] The eyepiece, used primarily in visual observing setups, acts as a magnifying lens that allows the observer to view this image by further magnifying it and presenting it at a comfortable distance.[15] Supporting these optics, the mount provides stability and precise tracking; common types include the altazimuth mount, which allows motion in altitude (up-down) and azimuth (left-right) directions, and the equatorial mount, aligned with Earth's rotational axis for easier sidereal tracking.[16] The tube or enclosure houses the optics, protecting them from stray light and environmental factors while maintaining alignment.[17] The fundamental principles governing telescope performance stem from geometric optics and wave properties of light. Light collection is determined by the objective's aperture area, which scales with the square of its diameter , given by the formula for circular apertures: This area dictates the telescope's light-gathering power, enabling detection of fainter objects compared to the unaided eye.[18] Image formation occurs at the objective's focal length , the distance from the optic to the point where parallel rays converge; longer focal lengths produce larger but dimmer images.[19] For refracting telescopes, angular magnification is calculated as the ratio of the objective's focal length to the eyepiece's: This formula highlights how shorter eyepiece focal lengths increase magnification, though practical limits arise from eye relief and field of view.[19] Telescopes employ two main optical principles: refraction and reflection. In refracting systems, light bends through transparent lenses, but this introduces chromatic aberration, where different wavelengths focus at slightly different points due to varying refractive indices, causing color fringing in images.[20] Reflecting telescopes avoid this by using curved mirrors to bounce light, reflecting all wavelengths equally without dispersion, though they may introduce other issues like off-axis aberrations.[21] Both types are ultimately limited by diffraction, the wave nature of light bending around the aperture edges, setting a theoretical angular resolution of approximately , where is the wavelength; smaller apertures yield blurrier images for fine details.[22] Earth's atmosphere impacts ground-based observations through seeing and extinction. Seeing refers to image blurring from turbulent air cells, which distort wavefronts and limit resolution to about 0.5–2 arcseconds under typical conditions, far coarser than diffraction limits for large telescopes.[23] Extinction diminishes light intensity via absorption (e.g., by water vapor or ozone) and scattering (e.g., by aerosols), with effects worsening at shorter wavelengths and higher airmasses; for instance, blue light suffers more than red.[24] To illustrate light-gathering power, the table below compares the collecting area of the human eye (pupil diameter ≈7 mm under dark conditions) to common telescope apertures, showing relative gains:[25]| Aperture Diameter (D) | Collecting Area (relative to eye) | Example Telescope Type |

|---|---|---|

| 7 mm | 1x | Human eye |

| 10 cm | 204x | Small refractor |

| 20 cm | 816x | Amateur reflector |

| 1 m | 20,224x | Professional observatory |