Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

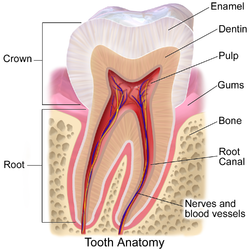

Human tooth

View on Wikipedia

| Human tooth | |

|---|---|

| |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | dens |

| TA2 | 914 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Human teeth function to mechanically break down items of food by cutting and crushing them in preparation for swallowing and digesting. As such, they are considered part of the human digestive system.[1] Humans have four types of teeth: incisors, canines, premolars, and molars, which each have a specific function. The incisors cut the food, the canines tear the food and the molars and premolars crush the food. The roots of teeth are embedded in the maxilla (upper jaw) or the mandible (lower jaw) and are covered by gums. Teeth are made of multiple tissues of varying density and hardness.

Humans, like most other mammals, are diphyodont, meaning that they develop two sets of teeth. The first set, deciduous teeth, also called "primary teeth", "baby teeth", or "milk teeth", normally eventually contains 20 teeth. Primary teeth typically start to appear ("erupt") around six months of age and this may be distracting and/or painful for the infant. However, some babies are born with one or more visible teeth, known as neonatal teeth or "natal teeth".

Structure

[edit]Dental anatomy is dedicated to the study of tooth structure. The development, appearance, and classification of teeth fall within its field of study, though dental occlusion, or contact between teeth, does not. Dental anatomy is also a taxonomic science as it is concerned with the naming of teeth and their structures. This information serves a practical purpose for dentists, enabling them to easily identify and describe teeth and structures during treatment.

The anatomic crown of a tooth is the area covered in enamel above the cementoenamel junction (CEJ) or "neck" of the tooth.[2][3] Most of the crown is composed of dentin ("dentine" in British English) with the pulp chamber inside.[4] The crown is within bone before eruption.[5] After eruption, it is almost always visible. The anatomic root is found below the CEJ and is covered with cementum. As with the crown, dentin composes most of the root, which normally has pulp canals. Canines and most premolars, except for maxillary first premolars, usually have one root. Maxillary first premolars and mandibular molars usually have two roots. Maxillary molars usually have three roots. Additional roots are referred to as supernumerary roots.

Humans usually have 20 primary (deciduous, "baby" or "milk") teeth and 32 permanent (adult) teeth. Teeth are classified as incisors, canines, premolars (also called bicuspids), and molars. Incisors are primarily used for cutting, canines are for tearing, and molars serve for grinding.

Most teeth have identifiable features that distinguish them from others. There are several different notation systems to refer to a specific tooth. The three most common systems are the FDI World Dental Federation notation (ISO 3950), the Universal Numbering System, and the Palmer notation. The FDI system is used worldwide, the Universal only in the United States, while the older Palmer notation still has some adherents only in the United Kingdom.

Primary teeth

[edit]Among deciduous (primary) teeth, ten are found in the maxilla (upper jaw) and ten in the mandible (lower jaw), for a total of 20. The dental formula for primary teeth in humans is 2.1.0.22.1.0.2.

In the primary set of teeth, in addition to the canines there are two types of incisors—centrals and laterals—and two types of molars—first and second. All primary teeth are normally later replaced with their permanent counterparts.

Permanent teeth

[edit]Among permanent teeth, 16 are found in the maxilla and 16 in the mandible, for a total of 32. The dental formula is 2.1.2.32.1.2.3. Permanent human teeth are numbered in a boustrophedonic sequence.

The maxillary teeth are the maxillary central incisors (teeth 8 and 9 in the diagram), maxillary lateral incisors (7 and 10), maxillary canines (6 and 11), maxillary first premolars (5 and 12), maxillary second premolars (4 and 13), maxillary first molars (3 and 14), maxillary second molars (2 and 15), and maxillary third molars (1 and 16). The mandibular teeth are the mandibular central incisors (24 and 25), mandibular lateral incisors (23 and 26), mandibular canines (22 and 27), mandibular first premolars (21 and 28), mandibular second premolars (20 and 29), mandibular first molars (19 and 30), mandibular second molars (18 and 31), and mandibular third molars (17 and 32). Third molars are commonly called "wisdom teeth" and usually emerge at ages 17 to 25.[6] These molars may never erupt into the mouth or form at all.[citation needed] When they do form, they often must be removed. If any additional teeth form—for example, fourth and fifth molars, which are rare—they are referred to as supernumerary teeth (hyperdontia). Development of fewer than the usual number of teeth is called hypodontia.

There are small differences between the teeth of males and females, with male teeth along with the male jaw tending to be larger on average than female teeth and jaw. There are also differences in the internal dental tissue proportions, with male teeth consisting of proportionately more dentin while female teeth have proportionately more enamel.[7]

Parts

[edit]Enamel

[edit]Enamel is the hardest and most highly mineralized substance of the body. It has its origin from oral ectoderm. It is one of the four major tissues which make up the tooth, along with dentin, cementum, and dental pulp.[8] It is normally visible and must be supported by underlying dentin. 96% of enamel consists of mineral, with water and organic material comprising the rest.[9] The normal color of enamel varies from light yellow to grayish white. At the edges of teeth where there is no dentin underlying the enamel, the color sometimes has a slightly blue tone. Since enamel is semitranslucent, the color of dentin and any restorative dental material underneath the enamel strongly affects the appearance of a tooth. Enamel varies in thickness over the surface of the tooth and is often thickest at the cusp, up to 2.5mm, and thinnest at its border, which is seen clinically as the CEJ.[10] The wear rate of enamel, called attrition, is 8 micrometers a year from normal factors.[11]

Enamel's primary mineral is hydroxyapatite, which is a crystalline calcium phosphate.[12] The large amount of minerals in enamel accounts not only for its strength but also for its brittleness.[10] Dentin, which is less mineralized and less brittle, compensates for enamel and is necessary as a support.[12] Unlike dentin and bone, enamel does not contain collagen. Proteins of note in the development of enamel are ameloblastins, amelogenins, enamelins and tuftelins. It is believed that they aid in the development of enamel by serving as framework support, among other functions.[13] In rare circumstances enamel can fail to form, leaving the underlying dentin exposed on the surface.[14]

Dentin

[edit]Dentin is the substance between enamel or cementum and the pulp chamber. It is secreted by the odontoblasts of the dental pulp.[15] The formation of dentin is known as dentinogenesis. The porous, yellow-hued material is made up of 70% inorganic materials, 20% organic materials, and 10% water by weight.[16] Because it is softer than enamel, it decays more rapidly and is subject to severe cavities if not properly treated, but dentin still acts as a protective layer and supports the crown of the tooth.

Dentin is a mineralized connective tissue with an organic matrix of collagenous proteins. Dentin has microscopic channels, called dentinal tubules, which radiate outward through the dentin from the pulp cavity to the exterior cementum or enamel border.[17] The diameter of these tubules range from 2.5 μm near the pulp, to 1.2 μm in the midportion, and 900 nm near the dentino-enamel junction.[18] Although they may have tiny side-branches, the tubules do not intersect with each other. Their length is dictated by the radius of the tooth. The three dimensional configuration of the dentinal tubules is genetically determined.

There are three types of dentin, primary, secondary and tertiary.[19] Secondary dentin is a layer of dentin produced after root formation and continues to form with age. Tertiary dentin is created in response to stimulus, such as cavities and tooth wear.[20]

Cementum

[edit]Cementum is a specialized bone-like substance covering the root of a tooth.[15] It is approximately 45% inorganic material (mainly hydroxyapatite), 33% organic material (mainly collagen) and 22% water. Cementum is excreted by cementoblasts within the root of the tooth and is thickest at the root apex. Its coloration is yellowish and it is softer than dentin and enamel. The principal role of cementum is to serve as a medium by which the periodontal ligaments can attach to the tooth for stability. At the cement to enamel junction, the cementum is acellular due to its lack of cellular components, and this acellular type covers at least 2⁄3 of the root.[21] The more permeable form of cementum, cellular cementum, covers about 1⁄3 of the root apex.[22]

Dental pulp

[edit]The dental pulp is the central part of the tooth filled with soft connective tissue.[16] This tissue contains blood vessels and nerves that enter the tooth from a hole at the apex of the root.[23] Along the border between the dentin and the pulp are odontoblasts, which initiate the formation of dentin.[16] Other cells in the pulp include fibroblasts, preodontoblasts, macrophages and T lymphocytes.[24] The pulp is commonly called "the nerve" of the tooth.

Development

[edit]

Tooth development is the complex process by which teeth form from embryonic cells, grow, and erupt into the mouth. Although many diverse species have teeth, their development is largely the same as in humans. For human teeth to have a healthy oral environment, enamel, dentin, cementum, and the periodontium must all develop during appropriate stages of fetal development. Primary teeth start to form in the development of the embryo between the sixth and eighth weeks, and permanent teeth begin to form in the twentieth week.[25] If teeth do not start to develop at or near these times, they will not develop at all.

A significant amount of research has focused on determining the processes that initiate tooth development. It is widely accepted that there is a factor within the tissues of the first pharyngeal arch that is necessary for the development of teeth.[26]

Tooth development is commonly divided into the following stages: the bud stage, the cap, the bell, and finally maturation. The staging of tooth development is an attempt to categorize changes that take place along a continuum; frequently it is difficult to decide what stage should be assigned to a particular developing tooth.[26] This determination is further complicated by the varying appearance of different histologic sections of the same developing tooth, which can appear to be different stages.

The tooth bud (sometimes called the tooth germ) is an aggregation of cells that eventually forms a tooth. It is organized into three parts: the enamel organ, the dental papilla and the dental follicle.[27] The enamel organ is composed of the outer enamel epithelium, inner enamel epithelium, stellate reticulum and stratum intermedium.[27] These cells give rise to ameloblasts, which produce enamel and the reduced enamel epithelium. The growth of cervical loop cells into the deeper tissues forms Hertwig's Epithelial Root Sheath, which determines a tooth's root shape. The dental papilla contains cells that develop into odontoblasts, which are dentin-forming cells.[27] Additionally, the junction between the dental papilla and inner enamel epithelium determines the crown shape of a tooth.[28] The dental follicle gives rise to three important cells: cementoblasts, osteoblasts, and fibroblasts. Cementoblasts form the cementum of a tooth. Osteoblasts give rise to the alveolar bone around the roots of teeth. Fibroblasts develop the periodontal ligaments which connect teeth to the alveolar bone through cementum.[29]

Eruption

[edit]

Tooth eruption in humans is a process in tooth development in which the teeth enter the mouth and become visible. Current research indicates that the periodontal ligaments play an important role in tooth eruption. Primary teeth erupt into the mouth from around six months until two years of age. These teeth are the only ones in the mouth until a person is about six years old. At that time, the first permanent tooth erupts. This stage, during which a person has a combination of primary and permanent teeth, is known as the mixed stage. The mixed stage lasts until the last primary tooth is lost and the remaining permanent teeth erupt into the mouth.

There have been many theories about the cause of tooth eruption. One theory proposes that the developing root of a tooth pushes it into the mouth. Another, known as the cushioned hammock theory, resulted from microscopic study of teeth, which was thought to show a ligament around the root. It was later discovered that the "ligament" was merely an artifact created in the process of preparing the slide. Currently, the most widely held belief is that the periodontal ligaments provide the main impetus for the process.

The onset of primary tooth loss has been found to correlate strongly with somatic and psychological criteria of school readiness.[30][31][clarification needed]

Supporting structures

[edit]

A: tooth

B: gingiva

C: bone

D: periodontal ligaments

The periodontium is the supporting structure of a tooth, helping to attach the tooth to surrounding tissues and to allow sensations of touch and pressure.[32] It consists of the cementum, periodontal ligaments, alveolar bone, and gingiva. Of these, cementum is the only one that is a part of a tooth. Periodontal ligaments connect the alveolar bone to the cementum. Alveolar bone surrounds the roots of teeth to provide support and creates what is commonly called an alveolus, or "socket". Lying over the bone is the gingiva or gum, which is readily visible in the mouth.

Periodontal ligaments

[edit]The periodontal ligament is a specialized connective tissue that attaches the cementum of a tooth to the alveolar bone. This tissue covers the root of the tooth within the bone. Each ligament has a width of 0.15–0.38mm, but this size decreases over time.[33] The functions of the periodontal ligaments include attachment of the tooth to the bone, support for the tooth, formation and resorption of bone during tooth movement, sensation, and eruption.[29] The cells of the periodontal ligaments include osteoblasts, osteoclasts, fibroblasts, macrophages, cementoblasts, and epithelial cell rests of Malassez.[34] Consisting of mostly Type I and III collagen, the fibers are grouped in bundles and named according to their location. The groups of fibers are named alveolar crest, horizontal, oblique, periapical, and interradicular fibers.[35] The nerve supply generally enters from the bone apical to the tooth and forms a network around the tooth toward the crest of the gingiva.[36] When pressure is exerted on a tooth, such as during chewing or biting, the tooth moves slightly in its socket and puts tension on the periodontal ligaments. The nerve fibers can then send the information to the central nervous system for interpretation.

Alveolar bone

[edit]The alveolar bone is the bone of the jaw which forms the alveolus around teeth.[37] Like any other bone in the human body, alveolar bone is modified throughout life. Osteoblasts create bone and osteoclasts destroy it, especially if force is placed on a tooth.[32] As is the case when movement of teeth is attempted through orthodontics, an area of bone under compressive force from a tooth moving toward it has a high osteoclast level, resulting in bone resorption. An area of bone receiving tension from periodontal ligaments attached to a tooth moving away from it has a high number of osteoblasts, resulting in bone formation.

Gingiva

[edit]The gingiva ("gums") is the mucosal tissue that overlays the jaws. There are three different types of epithelium associated with the gingiva: gingival, junctional, and sulcular epithelium. These three types form from a mass of epithelial cells known as the epithelial cuff between the tooth and the mouth.[38] The gingival epithelium is not associated directly with tooth attachment and is visible in the mouth. The junctional epithelium, composed of the basal lamina and hemidesmosomes, forms an attachment to the tooth.[29] The sulcular epithelium is nonkeratinized stratified squamous tissue on the gingiva which touches but is not attached to the tooth.[39]

Tooth decay

[edit]Plaque

[edit]Plaque is a biofilm consisting of large quantities of various bacteria that form on teeth.[40] If not removed regularly, plaque buildup can lead to periodontal problems such as gingivitis. Given time, plaque can mineralize along the gingiva, forming tartar. The microorganisms that form the biofilm are almost entirely bacteria (mainly streptococcus and anaerobes), with the composition varying by location in the mouth.[41] Streptococcus mutans is the most important bacterium associated with dental caries.

Certain bacteria in the mouth live off the remains of foods, especially sugars and starches. In the absence of oxygen they produce lactic acid, which dissolves the calcium and phosphorus in the enamel.[15][42] This process, known as "demineralisation", leads to tooth destruction. Saliva gradually neutralises the acids, which causes the pH of the tooth surface to rise above the critical pH, typically considered to be 5.5. This causes remineralisation, the return of the dissolved minerals to the enamel. If there is sufficient time between the intake of foods then the impact is limited and the teeth can repair themselves. Saliva is unable to penetrate through plaque, however, to neutralize the acid produced by the bacteria.

Caries (cavities)

[edit]

Dental caries (cavities), described as "tooth decay", is an infectious disease which damages the structures of teeth.[43] The disease can lead to pain, tooth loss, and infection. Dental caries has a long history, with evidence showing the disease was present in the Bronze Age, Iron Age, and Middle Ages but also prior to the Neolithic period.[44] The largest increases in the prevalence of caries have been associated with diet changes.[45] Today, caries remains one of the most common diseases throughout the world. In the United States, dental caries is the most common chronic childhood disease, being at least five times more common than asthma.[46] Countries that have experienced an overall decrease in cases of tooth decay continue to have a disparity in the distribution of the disease.[47] Among children in the United States and Europe, 60–80% of cases of dental caries occur in 20% of the population.[48]

Tooth decay is caused by certain types of acid-producing bacteria which cause the most damage in the presence of fermentable carbohydrates such as sucrose, fructose, and glucose.[49][50] The resulting acidic levels in the mouth affect teeth because a tooth's special mineral content causes it to be sensitive to low pH. Depending on the extent of tooth destruction, various treatments can be used to restore teeth to proper form, function, and aesthetics, but there is no known method to regenerate large amounts of tooth structure. Instead, dental health organizations advocate preventive and prophylactic measures, such as regular oral hygiene and dietary modifications, to avoid dental caries.[51]

Tooth care

[edit]Oral hygiene

[edit]

Oral hygiene is the practice of keeping the mouth clean and is a means of preventing dental caries, gingivitis, periodontal disease, bad breath, and other dental disorders. It consists of both professional and personal care. Regular cleanings, usually done by dentists and dental hygienists, remove tartar (mineralized plaque) that may develop even with careful brushing and flossing. Professional cleaning includes tooth scaling, using various instruments or devices to loosen and remove deposits from teeth.

The purpose of cleaning teeth is to remove plaque, which consists mostly of bacteria.[52] Healthcare professionals recommend regular brushing twice a day (in the morning and in the evening, or after meals) in order to prevent formation of plaque and tartar.[51] A toothbrush is able to remove most plaque, except in areas between teeth. As a result, flossing is also considered a necessity to maintain oral hygiene. When used correctly, dental floss removes plaque from between teeth and at the gum line, where periodontal disease often begins and could develop caries.

Electric toothbrushes are a popular aid to oral hygiene. A user without disabilities, with proper training in manual brushing, and with good motivation, can achieve standards of oral hygiene at least as satisfactory as the best electric brushes, but untrained users rarely achieve anything of the kind. Not all electric toothbrushes are equally effective and even a good design needs to be used properly for best effect, but: "Electric toothbrushes tend to help people who are not as good at cleaning teeth and as a result have had oral hygiene problems."[53] The most important advantage of electric toothbrushes is their ability to aid people with dexterity difficulties, such as those associated with rheumatoid arthritis.

Protective treatments

[edit]Fluoride therapy is often recommended to protect against dental caries. Water fluoridation and fluoride supplements decrease the incidence of dental caries. Fluoride helps prevent dental decay by binding to the hydroxyapatite crystals in enamel.[54] The incorporated fluoride makes enamel more resistant to demineralization and thus more resistant to decay.[29] Topical fluoride, such as a fluoride toothpaste or mouthwash, is also recommended to protect teeth surfaces. Many dentists include application of topical fluoride solutions as part of routine cleanings.

Dental sealants are another preventive therapy often used to provide a barrier to bacteria and decay on the surface of teeth. Sealants can last up to ten years and are primarily used on the biting surfaces of molars of children and young adults, especially those who may have difficulty brushing and flossing effectively. Sealants are applied in a dentist's office, sometimes by a dental hygienist, in a procedure similar in technique and cost to a fluoride application.

Restorations

[edit]

After a tooth has been damaged or destroyed, restoration of the missing structure can be achieved with a variety of treatments. Restorations may be created from a variety of materials, including glass ionomer, amalgam, gold, porcelain, and composite.[55] Small restorations placed inside a tooth are referred to as "intracoronal restorations". These restorations may be formed directly in the mouth or may be cast using the lost-wax technique, such as for some inlays and onlays. When larger portions of a tooth are lost, an "extracoronal restoration" may be fabricated, such as an artificial crown or a veneer, to restore the involved tooth.

When a tooth is lost, dentures, bridges, or implants may be used as replacements.[56] Dentures are usually the least costly whereas implants are usually the most expensive. Dentures may replace complete arches of the mouth or only a partial number of teeth. Bridges replace smaller spaces of missing teeth and use adjacent teeth to support the restoration. Dental implants may be used to replace a single tooth or a series of teeth. Though implants are the most expensive treatment option, they are often the most desirable restoration because of their aesthetics and function. To improve the function of dentures, implants may be used as support.[57]

Abnormalities

[edit]

Tooth abnormalities may be categorized according to whether they have environmental or developmental causes.[58] While environmental abnormalities may appear to have an obvious cause, there may not appear to be any known cause for some developmental abnormalities. Environmental forces may affect teeth during development, destroy tooth structure after development, discolor teeth at any stage of development, or alter the course of tooth eruption. Developmental abnormalities most commonly affect the number, size, shape, and structure of teeth.

Environmental

[edit]Alteration during tooth development

[edit]Tooth abnormalities caused by environmental factors during tooth development have long-lasting effects. Enamel and dentin do not regenerate after they mineralize initially. Enamel hypoplasia is a condition in which the amount of enamel formed is inadequate.[59] This results either in pits and grooves in areas of the tooth or in widespread absence of enamel. Diffuse opacities of enamel does not affect the amount of enamel but changes its appearance. Affected enamel has a different translucency than the rest of the tooth. Demarcated opacities of enamel have sharp boundaries where the translucency decreases and manifest a white, cream, yellow, or brown color. All these may be caused by nutritional factors,[60] an exanthematous disease (chicken pox, congenital syphilis),[60][61] undiagnosed and untreated celiac disease,[62][63][64] hypocalcemia, dental fluorosis, birth injury, preterm birth, infection or trauma from a deciduous tooth.[60] Dental fluorosis is a condition which results from ingesting excessive amounts of fluoride and leads to teeth which are spotted, yellow, brown, black or sometimes pitted. In most cases, the enamel defects caused by celiac disease, which may be the only manifestation of this disease in the absence of any other symptoms or signs, are not recognized and mistakenly attributed to other causes, such as fluorosis.[62] Enamel hypoplasia resulting from syphilis is frequently referred to as Hutchinson's teeth, which is considered one part of Hutchinson's triad.[65] Turner's hypoplasia is a portion of missing or diminished enamel on a permanent tooth usually from a prior infection of a nearby primary tooth. Hypoplasia may also result from antineoplastic therapy.

Destruction after development

[edit]Tooth destruction from processes other than dental caries is considered a normal physiologic process but may become severe enough to become a pathologic condition. Attrition is the loss of tooth structure by mechanical forces from opposing teeth.[66] Attrition initially affects the enamel and, if unchecked, may proceed to the underlying dentin. Abrasion is the loss of tooth structure by mechanical forces from a foreign element.[67] If this force begins at the cementoenamel junction, then progression of tooth loss can be rapid since enamel is very thin in this region of the tooth. A common source of this type of tooth wear is excessive force when using a toothbrush. Erosion is the loss of tooth structure due to chemical dissolution by acids not of bacterial origin.[68] Signs of tooth destruction from erosion is a common characteristic in the mouths of people with bulimia since vomiting results in exposure of the teeth to gastric acids. Another important source of erosive acids are from frequent sucking of lemon juice. Abfraction is the loss of tooth structure from flexural forces. As teeth flex under pressure, the arrangement of teeth touching each other, known as occlusion, causes tension on one side of the tooth and compression on the other side of the tooth. This is believed to cause V-shaped depressions on the side under tension and C-shaped depressions on the side under compression. When tooth destruction occurs at the roots of teeth, the process is referred to as internal resorption, when caused by cells within the pulp, or external resorption, when caused by cells in the periodontal ligament.

Discoloration

[edit]

Discoloration of teeth may result from bacteria stains, tobacco, tea, coffee, foods with an abundance of chlorophyll, restorative materials, and medications.[69] Stains from bacteria may cause colors varying from green to black to orange. Green stains also result from foods with chlorophyll or excessive exposure to copper or nickel. Amalgam, a common dental restorative material, may turn adjacent areas of teeth black or gray. Long term use of chlorhexidine, a mouthwash, may encourage extrinsic stain formation near the gingiva on teeth. This is usually easy for a hygienist to remove. Systemic disorders also can cause tooth discoloration. Congenital erythropoietic porphyria causes porphyrins to be deposited in teeth, causing a red-brown coloration. Blue discoloration may occur with alkaptonuria and rarely with Parkinson's disease. Erythroblastosis fetalis and biliary atresia are diseases which may cause teeth to appear green from the deposition of biliverdin. Also, trauma may change a tooth to a pink, yellow, or dark gray color. Pink and red discolorations are also associated in patients with lepromatous leprosy. Some medications, such as tetracycline antibiotics, may become incorporated into the structure of a tooth, causing intrinsic staining of the teeth.

Alteration of eruption

[edit]Tooth eruption may be altered by some environmental factors. When eruption is prematurely stopped, the tooth is said to be impacted. The most common cause of tooth impaction is lack of space in the mouth for the tooth.[70] Other causes may be tumors, cysts, trauma, and thickened bone or soft tissue. Tooth ankylosis occurs when the tooth has already erupted into the mouth but the cementum or dentin has fused with the alveolar bone. This may cause a person to retain their primary tooth instead of having it replaced by a permanent one.

A technique for altering the natural progression of eruption is employed by orthodontists who wish to delay or speed up the eruption of certain teeth for reasons of space maintenance or otherwise preventing crowding and/or spacing. If a primary tooth is extracted before its succeeding permanent tooth's root reaches 1⁄3 of its total growth, the eruption of the permanent tooth will be delayed. Conversely, if the roots of the permanent tooth are more than 2⁄3 complete, the eruption of the permanent tooth will be accelerated. Between 1⁄3 and 2⁄3, it is unknown exactly what will occur to the speed of eruption.

Developmental

[edit]Abnormality in number

[edit]- Anodontia is the total lack of tooth development.

- Hyperdontia is the presence of a higher-than-normal number of teeth.

- Hypodontia is the lack of development of one or more teeth.

- Oligodontia may be used to describe the absence of 6 or more teeth.

Some systemic disorders which may result in hyperdontia include Apert syndrome, cleidocranial dysostosis, Crouzon syndrome, Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, Gardner's syndrome, and Sturge–Weber syndrome.[71] Some systemic disorders which may result in hypodontia include Crouzon syndrome, Ectodermal dysplasia, Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, and Gorlin syndrome.[72]

Abnormality in size

[edit]- Microdontia is a condition where teeth are smaller than the usual size.

- Macrodontia is where teeth are larger than the usual size.

Microdontia of a single tooth is more likely to occur in a maxillary lateral incisor. The second most likely tooth to have microdontia are third molars. Macrodontia of all the teeth is known to occur in pituitary gigantism and pineal hyperplasia. It may also occur on one side of the face in cases of hemifacial hyperplasia.

Abnormality in shape

[edit]

- Gemination occurs when a developing tooth incompletely splits into the formation of two teeth.

- Fusion is the union of two adjacent teeth during development.

- Concrescence is the fusion of two separate teeth only in their cementum.

- Accessory cusps are additional cusps on a tooth and may manifest as a Talon cusp, Cusp of Carabelli, or Dens evaginatus.

- Dens invaginatus, also called Dens in dente, is a deep invagination in a tooth causing the appearance of a tooth within a tooth.

- Ectopic enamel is enamel found in an unusual location, such as the root of a tooth.

- Taurodontism is a condition where the body of the tooth and pulp chamber is enlarged, and is associated with Klinefelter syndrome, Tricho-dento-osseous syndrome, Triple X syndrome, and XYY syndrome.[73]

- Hypercementosis is excessive formation of cementum, which may result from trauma, inflammation, acromegaly, rheumatic fever, and Paget's disease of bone.[73]

- A dilaceration is a bend in the root which may have been caused by trauma to the tooth during formation.

- Supernumerary roots is the presence of a greater number of roots on a tooth than expected

Cleft lip and palate and their association with dental anomalies

[edit]There are many types of dental anomalies seen in cleft lip and palate (CLP) patients. Both sets of dentition may be affected; however, they are commonly seen in the affected side. Most frequently, missing teeth, supernumerary or discoloured teeth can be seen; however, enamel dysplasia, discolouration and delayed root development are also common. In children with cleft lip and palate, the lateral incisor in the alveolar cleft region has the highest prevalence of dental developmental disorders;[74] this condition may be a cause of tooth crowding.[75] This is important to consider in order to correctly plan treatment keeping in mind considerations for function and aesthetics. By correctly coordinating management invasive treatment procedures can be prevented resulting in successful and conservative treatment.

There have been a plethora of research studies to calculate prevalence of certain dental anomalies in CLP populations however a variety of results have been obtained.

In a study evaluating dental anomalies in Brazilian cleft patients, male patients had a higher incidence of CLP, agenesis, and supernumerary teeth than did female patients. In cases of complete CLP, the left maxillary lateral incisor was the most commonly absent tooth. Supernumerary teeth were typically located distal to the cleft.[76] In a study of Jordanian subjects, the prevalence of dental anomaly was higher in CLP patients than in normal subjects. Missing teeth were observed in 66.7% of patients, with maxillary lateral incisor as the most frequently affected tooth. Supernumerary teeth were observed in 16.7% of patients; other findings included microdontia (37%), taurodontism (70.5%), transposition or ectopic teeth (30.8%), dilacerations (19.2%), and hypoplasia (30.8%). The incidence of microdontia, dilaceration, and hypoplasia was significantly higher in bilateral CLP patients than in unilateral CLP patients, and none of the anomalies showed any significant sexual dimorphism.[77]

It is therefore evident that patients with cleft lip and palate may present with a variety of dental anomalies. It is essential to assess the patient both clinically and radiographically in order to correctly treat and prevent progression of any dental problems. It is also useful to note that patients with a cleft lip and palate automatically score a 5 on the IOTN ( index for orthodontic need) and therefore are eligible for orthodontic treatment, liaising with an orthodontist is vital in order coordinate and plan treatment successfully.

Abnormality in structure

[edit]- Amelogenesis imperfecta is a condition in which enamel does not form properly or at all.[78]

- Dentinogenesis imperfecta is a condition in which dentin does not form properly and is sometimes associated with osteogenesis imperfecta.[79]

- Dentin dysplasia is a disorder in which the roots and pulp of teeth may be affected.

- Regional odontodysplasia is a disorder affecting enamel, dentin, and pulp and causes the teeth to appear "ghostly" on radiographs.[80]

- Diastema is a condition in which there is a gap between two teeth caused by the imbalance in the relationship between the jaw and the size of teeth.[81]

See also

[edit]Lists

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Stay, Flora. "How Your Teeth Affect Your Digestive System". TotalHealth Magazine. Archived from the original on 18 December 2023. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ Clemente, Carmine (1987). Anatomy, a regional atlas of the human body. Baltimore: Urban & Schwarzenberg. ISBN 978-0-8067-0323-7.

- ^ Ash 2003, p. 6

- ^ Cate 1998, p. 3

- ^ Ash 2003, p. 9

- ^ "Impacted wisdom teeth". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ Sorenti, Mark; Martinón-Torres, María; Martín-Francés, Laura; Perea-Pérez, Bernardo (2019). "Sexual dimorphism of dental tissues in modern human mandibular molars". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 169 (2): 332–340. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23822. ISSN 1096-8644. PMID 30866041. S2CID 76662620.

- ^ Ross 2002, p. 441

- ^ Cate 1998, p. 1

- ^ a b Cate 1998, p. 219

- ^ "Tooth enamel | Drug Discrimination Database".

- ^ a b Johnson, Clarke (1998). "Biology of the Human Dentition Archived 2015-10-30 at the Wayback Machine". uic.edu.

- ^ Cate 1998, p. 198

- ^ "Severe Plane-Form Enamel Hypoplasia in a Dentition from Roman Britain". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2019-01-09.

- ^ a b c Ross 2002, p. 448

- ^ a b c Cate 1998, p. 150

- ^ Ross 2002, p. 450

- ^ Cate 1998, p. 152

- ^ Zilberman, U.; Smith, P. (2001). "Sex- and Age-related Differences in Primary and Secondary Dentin Formation". Advances in Dental Research. 15: 42–45. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.535.5123. doi:10.1177/08959374010150011101. PMID 12640738. S2CID 4798656.

- ^ "Tertiary Dentine Frequencies in Extant Great Apes and Fossil Hominins". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2019-03-28.

- ^ Cate 1998, p. 236

- ^ Cate 1998, p. 241

- ^ Ross 2002, p. 451

- ^ Walton, Richard E. and Mahmoud Torabinejad. Principles and Practice of Endodontics. 3rd ed. 2002. pp. 11–13. ISBN 0-7216-9160-9.

- ^ Cate 1998, p. 95

- ^ a b Cate 1998, p. 81

- ^ a b c Lab Exercises: Tooth development. University of Texas Medical Branch.

- ^ Cate 1998, pp. 86 and 102.

- ^ a b c d Ross 2002, p. 453

- ^ Kranich, Ernst-Michael (1990) "Anthropologie", in F. Bohnsack and E-M Kranich (eds.), Erziehungswissenschaft und Waldorfpädagogik, Reihe Pädagogik Beltz, Weinheim, p. 126, citing Frances Ilg and Louise Bates Ames (Gesell Institute), School Readiness, p. 236 ff

- ^ Silvestro, JR (1977). "Second Dentition and School Readiness". New York State Dental Journal. 43 (3): 155–8. PMID 264640.

...the loss of the first deciduous tooth can serve as a definite indicator of a male child's readiness for reading and schoolwork

- ^ a b Ross 2002, p. 452

- ^ Cate 1998, p. 256

- ^ Cate 1998, p. 260

- ^ Listgarten, Max A. "Histology of the Periodontium: Principal fibers of the periodontal ligament," University of Pennsylvania and Temple University. Created May 8, 1999, revised 16 January 2007.

- ^ Cate 1998, p. 270

- ^ Cate 1998, p. 274

- ^ Cate 1998, pp. 247 and 248

- ^ Cate 1998, p. 280

- ^ "Oral Health Topics: Plaque", American Dental Association.

- ^ Introduction to dental plaque Archived 2011-08-27 at the Wayback Machine, Leeds Dental Institute.

- ^ Ophardt, Charles E. "Sugar and tooth decay", Elmhurst College.

- ^ Dental Cavities, MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia.

- ^ Seiler R, Spielman AI, Zink A, Rühli F (2013). "Oral pathologies of the Neolithic Iceman, c.3,300 BC". European Journal of Oral Sciences (Historical Article. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't). 121 (3 Pt 1): 137–41. doi:10.1111/eos.12037. PMID 23659234.

- ^ Suddick RP, Harris NO (1990). "Historical perspectives of oral biology: a series". Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 1 (2): 135–51. doi:10.1177/10454411900010020301. PMID 2129621.

- ^ Healthy People: 2010. Healthy People.gov.

- ^ "Dental caries", from the Disease Control Priorities Project.

- ^ Touger-Decker R, van Loveren C (2003). "Sugars and dental caries". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 78 (4): 881S – 892S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/78.4.881S. PMID 14522753.

- ^ Hardie JM (1982). "The microbiology of dental caries". Dent Update. 9 (4): 199–200, 202–4, 206–8. PMID 6959931.

- ^ Moore WJ; Moore, W.J. (1983). "The role of sugar in the aetiology of dental caries. 1. Sugar and the antiquity of dental caries". J Dent. 11 (3): 189–90. doi:10.1016/0300-5712(83)90182-3. PMID 6358295.

- ^ a b Oral Health Topics: Cleaning your teeth and gums. American Dental Association.

- ^ Introduction to Dental Plaque Archived 2011-08-27 at the Wayback Machine. Leeds Dental Institute.

- ^ Thumbs down for electric toothbrush, BBC News, January 21, 2003.

- ^ Cate 1998, p. 223

- ^ "Oral Health Topics: Dental Filling Options". ada.org.

- ^ "Prosthodontic Procedures", The American College of Prosthodontists.

- ^ "Dental Implants", American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons.

- ^ Neville 2002, p. 50.

- ^ Ash 2003, p. 31

- ^ a b c Kanchan T, Machado M, Rao A, Krishan K, Garg AK (Apr 2015). "Enamel hypoplasia and its role in identification of individuals: A review of literature". Indian J Dent (Revisión). 6 (2): 99–102. doi:10.4103/0975-962X.155887. PMC 4455163. PMID 26097340.

- ^ Neville 2002, p. 51

- ^ a b Dental Enamel Defects and Celiac Disease Archived 2016-03-05 at the Wayback Machine National Institute of Health (NIH)

- ^ Ferraz EG, Campos Ede J, Sarmento VA, Silva LR (2012). "The oral manifestations of celiac disease: information for the pediatric dentist". Pediatr Dent (Review). 34 (7): 485–8. PMID 23265166.

- ^ Giuca MR, Cei G, Gigli F, Gandini P (2010). "Oral signs in the diagnosis of celiac disease: review of the literature". Minerva Stomatol (Review). 59 (1–2): 33–43. PMID 20212408.

- ^ Syphilis: Complications, Mayo Clinic.

- ^ "Loss of Tooth Structure Archived 2012-12-27 at the Wayback Machine", American Dental Hygiene Association.

- ^ "Abnormalities of Teeth", University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Dentistry.

- ^ Yip, KH; Smales, RJ; Kaidonis, JA (2003). "The diagnosis and control of extrinsic acid erosion of tooth substance" (PDF). General Dentistry. 51 (4): 350–3, quiz 354. PMID 15055615. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 7, 2006.

- ^ Neville 2002, p. 63

- ^ Neville 2002, p. 66

- ^ Neville 2002, p. 70

- ^ Neville 2002, p. 69

- ^ a b Neville 2002, p. 85

- ^ Tortora C, Meazzini MC, Garattini G, Brusati R (March 2008). "Prevalence of abnormalities in dental structure, position and eruption pattern in population of unilateral and bilateral cleft lip and palate patients". The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal. 45 (2): 154–162. doi:10.1597/06-218.1. PMID 18333651. S2CID 23991279.

- ^ "Dental Crowding: Causes and Treatment Options". Orthodontics Australia. 2020-06-29. Retrieved 2021-02-06.

- ^ Luciane Macedo de Menezes; Susana Maria Deon Rizzatto; Fabiane Azeredo; Diogo Antunes Vargas (2010). "Characteristics and distribution of dental anomalies in a Brazilian cleft population". Revista Odonto Ciência. 25 (2): 137–141. doi:10.1590/S1980-65232010000200006.

- ^ Al Jamal GA, Hazza'a AM, Rawashdeh MA (2010). "Prevalence of dental anomalies in a population of cleft lip and palate patients". The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal. 47 (4): 413–420. doi:10.1597/08-275.1. PMID 20590463. S2CID 7220626.

- ^ Amelogenesis imperfecta, Genetics Home Reference, a service of the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Dentinogenesis imperfecta, Genetics Home Reference, a service of the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Cho, Shiu-yin (2006). "Conservative Management of Regional Odontodysplasia: Case Report" (PDF). J Can Dent Assoc. 72 (8): 735–8. PMID 17049109.

- ^ ASDC Journal of Dentistry for Children, Volume 48. American Society of Dentistry for Children, 1980. p. 266

Sources

[edit]- Ash, Major M.; Nelson, Stanley J. (2003). Wheeler's Dental Anatomy, Physiology, and Occlusion (8th ed.). W.B. Saunders. ISBN 978-0-7216-9382-8.

- Cate, A. R. Ten (1998). Oral Histology: development, structure, and function (5th ed.). Mosby. ISBN 978-0815129523.

- Neville, B. W.; Damm, D.; Allen, C.; Bouquot, J. (2002). Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology (2nd ed.). W.B. Saunders. ISBN 978-0-7216-9003-2.

- Ross, Michael H.; Kaye, Gordon I.; Pawlina, Wojciech (2002). Histology: a Text and Atlas (4th ed.). Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0683302424.

External links

[edit]Human tooth

View on GrokipediaEvolutionary Background

Origins and adaptations in hominids

Early hominids, such as Australopithecus species dating from approximately 4 to 2 million years ago, exhibited robust dental morphology characterized by larger jaw sizes, thicker enamel, and pronounced canine teeth compared to later Homo species, adaptations suited to processing tough, fibrous plant-based diets supplemented by occasional hard or abrasive foods. Fossil evidence from East African sites, including specimens of Australopithecus afarensis, reveals molars with relatively low occlusal relief and slope, facilitating grinding of abrasive vegetation, while the presence of large, sexually dimorphic canines suggests a role in display or intra-group competition rather than primary food processing.[6][7] These features reflect selective pressures from a diet dominated by C3 and C4 plants requiring extensive mastication, as inferred from microwear patterns and isotopic analysis of enamel.[8] The transition to the genus Homo around 2.8 to 1.8 million years ago marked a significant reduction in overall tooth size, jaw robusticity, and canine projection relative to Australopithecus, with early Homo erectus fossils from sites like Dmanisi and Koobi Fora showing smaller postcanine teeth and diminished sexual dimorphism in canines. This dental miniaturization, evidenced by metrics such as reduced mandibular corpus breadth and molar crown areas up to 20-30% smaller than in australopiths, correlates with the advent of flaked stone tools (Oldowan industry) around 2.6 million years ago, which enabled food preprocessing like slicing meat or pounding plants, thereby alleviating selective pressure for massive chewing apparatus.[9][10][11] Comparative dental metrics indicate that early Homo cheek teeth evolved more sloping occlusal surfaces for shearing tougher items efficiently, reflecting a dietary shift toward higher-quality foods like meat and marrow, which demanded less grinding force.[12] In Homo erectus, spanning roughly 1.9 million to 110,000 years ago, further adaptations included even smaller anterior teeth and a trend toward parabolic dental arcades, as seen in fossils from Java and Zhoukoudian, linked to advanced tool technologies (Acheulean handaxes) and potential fire use for cooking by at least 1 million years ago, which softened foods and reduced the need for robust dentition.[11][13] Enamel thickness in these hominids remained relatively thick—moderate to extreme compared to great apes—serving as a wear-resistant layer against abrasive particles from unprocessed or grit-contaminated foods, though variations across taxa suggest homoplasy driven by durophagous (hard-object) feeding or prolonged dietary abrasion rather than uniform selective pressure.[14][15] This combination of morphological changes underscores how behavioral innovations in food acquisition and preparation causally drove evolutionary relaxation of dental robusticity, prioritizing encephalization over masticatory power.[16]Dietary shifts and morphological changes

Human dentition features reduced, blunt canines and flat molars suited for grinding plant material, unlike the sharp, pointed canines and carnassial teeth of carnivores adapted for shearing meat, illustrating evolutionary adaptations for omnivory.[17] The transition from hunter-gatherer lifestyles to agriculture around 10,000 BCE introduced diets dominated by softer, carbohydrate-rich staples such as ground grains and tubers, which required less masticatory force compared to the tough, fibrous foods like raw meats, nuts, and roots prevalent in pre-agricultural societies.[18] This shift reduced the biomechanical loading on the jaws, leading to diminished alveolar bone stimulation and consequent underdevelopment of mandibular and maxillary dimensions, as bone remodeling responds directly to mechanical stress per principles of functional adaptation.[19] Ancestral populations exhibited larger, more robust dentition suited to processing unprocessed foods, with tooth crowns and roots scaled to accommodate expansive jaw arches that minimized impaction risks.[20] Post-Neolithic skeletal analyses reveal a marked reduction in jaw size—typically 10-15% shorter and narrower mandibles in early farmers versus contemporaneous hunter-gatherers—correlating with decreased occlusal wear and overall tooth dimensions, as softer diets failed to promote full skeletal maturation during ontogeny.[21] [22] These morphological changes manifested rapidly across generations, evident in comparative studies of Mesolithic-Neolithic transitions, where agricultural groups displayed brachycephalic tendencies and reduced facial robusticity attributable to dietary softening rather than isolated genetic selection, given the timescale precludes substantial evolutionary drift.[23] The causal mechanism involves diminished perimasticatory muscle activity, which limits condylar growth and alveolar expansion, resulting in insufficient space for erupting teeth and predisposing to misalignment without invoking inherent genetic predispositions over environmental drivers.[24] Empirical data from global archaeological samples confirm higher rates of dental crowding and third molar impaction in agriculturalist remains—up to 20-30% prevalence versus near-absent in hunter-gatherers—directly linked to contracted dental arches from reduced chewing demands.[20] This pattern persists into modern populations, where industrialized ultra-processed foods exacerbate the trend, but originates in the Neolithic pivot to farming, as validated by morphometric analyses showing consistent craniofacial gracilization tied to subsistence shifts.[19] Accompanying these adaptations, the Neolithic diet's higher fermentable carbohydrate content elevated caries prevalence—rising from under 5% in pre-agricultural teeth to 10-15% or more in early farmers—due to increased substrate for acidogenic bacteria, independent of hygiene variances.[25] Enamel hypoplasia, marking episodic growth disruptions often from nutritional deficits in weaning-age children reliant on starchy porridges, showed elevated frequencies (e.g., 12-20% in Neolithic samples versus lower in foragers), reflecting metabolic stresses from monocrop dependence rather than purely infectious or climatic factors.[26] Such pathologies underscore diet's primacy in dental health trajectories, countering attributions to inevitable genetic decay by demonstrating reversible environmental causation in responsive craniofacial systems.[27]Anatomy

Classification and types

Human teeth are classified into two main sets: deciduous (primary) and permanent dentition. The deciduous set comprises 20 teeth, with 10 in each dental arch: 8 incisors, 4 canines, and 8 molars, lacking premolars.[28] These teeth erupt between 6 months and approximately 3 years of age, beginning with central incisors at 6-12 months and completing with second molars at 23-33 months.[28]| Dentition | Total Teeth | Incisors | Canines | Premolars | Molars |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deciduous | 20 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 8 |

| Permanent | 32 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 12 |

External and internal components

The human tooth is divided into three principal external regions: the crown, the neck, and the root. The crown represents the visible portion projecting above the gingiva, shaped to facilitate specific masticatory functions, while the neck forms a constricted zone at the cemento-enamel junction, and the root anchors the tooth within the alveolar process. These components provide structural integrity, with the crown typically measuring 8 to 12 mm in height depending on tooth type, such as approximately 10.8 mm for the maxillary central incisor crown.[33] Anterior teeth, including incisors and canines, generally possess a single root, whereas posterior premolars often have one or two roots, and molars feature two to three roots for enhanced stability. Root lengths vary by tooth and arch; for instance, the maxillary central incisor root averages 13.0 mm, the maxillary canine root about 17.0 mm, and premolar roots around 14 mm.[33] [34] The root terminates at the apical foramen, a small opening permitting passage of neurovascular structures into the periodontal tissues.[35] Internally, the pulp cavity occupies the central space within the tooth, extending from the pulp chamber in the crown through root canals to the apex. This cavity houses the dental pulp, comprising soft connective tissue, blood vessels, and nerves, which is isolated from the surrounding dentin by its tubular structure.[36] [35] The pulp chamber's configuration mirrors the crown's outline, narrowing into canals that branch in multi-rooted teeth to supply each root.[37]Histological layers

The enamel forms the outermost protective layer over the crown of the tooth, characterized by its acellular nature and high degree of mineralization. Composed primarily of hydroxyapatite crystals organized into rod-like prisms, enamel contains approximately 96% mineral by weight, with the remainder consisting of trace organic proteins and water. This composition renders enamel the hardest tissue in the human body, with empirical measurements confirming its superior resistance to mechanical wear compared to other dental structures. However, lacking living cells after maturation, enamel possesses no capacity for repair or regeneration.[38][39] Underlying the enamel is the dentin, which constitutes the main structural bulk of the tooth and exhibits a porous, tubular microstructure. Dentin comprises about 70% mineral by weight—primarily hydroxyapatite—along with 20% organic matrix dominated by type I collagen and 10% water, enabling some degree of flexibility absent in enamel. The dentinal tubules, which house extensions of odontoblasts, traverse this layer and facilitate sensory responses to thermal, chemical, or mechanical stimuli through fluid movement within them. While less mineralized than enamel, dentin's higher organic content allows odontoblasts to deposit secondary dentin as a reparative mechanism in response to irritation, though this process is limited and does not restore original structure.[40][41] The cementum is a thin, mineralized layer covering the root surface, analogous in composition to bone but avascular and with lower cellularity. It consists of roughly 65% mineral by weight, embedded in an organic matrix of collagen fibers that anchor the periodontal ligament for tooth support. Unlike enamel, cementum undergoes continuous, albeit slow, deposition throughout life via cementoblasts, contributing to root adaptation under functional loads. Its permeability and vascular proximity via the ligament distinguish it from the impermeable enamel, influencing its role in tissue attachment rather than direct wear resistance.[41][42] At the core resides the dental pulp, a soft, gelatinous connective tissue filling the pulp chamber and root canals. Predominantly composed of extracellular matrix with fibroblasts, collagen, and ground substance, the pulp houses blood vessels, nerves, and odontoblasts arrayed along its periphery. These odontoblasts, derived from neural crest cells, secrete the initial predentin matrix that mineralizes into dentin, and they persist to generate reactionary or tertiary dentin under stress. The pulp's vascularity and innervation provide nutritive and sensory functions, but its enclosed position renders it vulnerable to inflammation from external insults penetrating outer layers.[40][43]| Tissue | Mineral Content (wt%) | Primary Mineral | Key Microstructural Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enamel | ~96% | Hydroxyapatite | Prism-like rods, acellular |

| Dentin | ~70% | Hydroxyapatite | Tubules with odontoblastic processes |

| Cementum | ~65% | Hydroxyapatite | Collagen-embedded Sharpey's fibers |

| Pulp | 0% | None | Vascular connective tissue |

Development

Embryonic formation

Tooth development, or odontogenesis, initiates during the sixth to eighth week of gestation when the oral epithelium thickens to form the dental lamina, a band of ectodermal tissue along the future alveolar ridges of the maxilla and mandible.[44] This structure gives rise to epithelial buds that invaginate into the underlying neural crest-derived mesenchyme, marking the bud stage and establishing sites for 20 primary tooth germs (10 per arch).[44] By the eighth week, these buds are evident, with the primary tooth primordia positioned symmetrically to ensure bilateral mirroring of dentition.[45] Progression to the cap stage occurs around the ninth to tenth week, where buds proliferate and partially enclose mesenchymal condensations forming the dental papilla and dental follicle.[44] The bell stage follows by approximately 14 weeks, characterized by further epithelial differentiation into the enamel organ: the inner enamel epithelium (future ameloblasts), outer enamel epithelium, stellate reticulum, and stratum intermedium.[44] Concurrently, the dental papilla differentiates into odontoblasts, which begin secreting predentin, while mesenchymal cells in the follicle commit to periodontal and cementum lineages.[44] Hard tissue formation commences in the late bell stage around 16 weeks with apposition and calcification: ameloblasts from the inner epithelium produce enamel matrix proteins (e.g., amelogenin), enabling hydroxyapatite deposition, while odontoblasts lay down dentin matrix.[44] Primary crown calcification is underway by this point, with enamel organ maturation ensuring crown morphology.[44] Buds for permanent successors emerge lingually from the primary dental lamina extensions by 20 weeks, initiating secondary dentition development in a similar sequential manner.[2] Genetic regulation, primarily via homeobox transcription factors like Msx1, Msx2, and Dlx family genes, orchestrates these processes through epithelial-mesenchymal signaling (e.g., via BMP, FGF, and Shh pathways), controlling bud initiation, cusp patterning, and symmetry.[46] Mutations in these genes, such as Msx1 loss-of-function variants, disrupt odontogenesis, resulting in selective tooth agenesis (e.g., second premolars or third molars absent) or syndromes like Witkop syndrome, underscoring their causal role in precise spatiotemporal control.[46][47] Empirical studies in knockout models confirm these genes' necessity for bud-to-cap transitions and enamel knot formation, without which bilateral asymmetry or aplasia ensues.[46]Tooth eruption and replacement

Tooth eruption refers to the axial movement of teeth from their developmental position within the alveolar bone through the overlying mucosa into functional occlusion in the oral cavity. In humans, this process occurs for both primary and permanent dentitions, but the replacement phase focuses on the succession of permanent teeth displacing the primary set. The mixed dentition phase, spanning approximately ages 6 to 12 years, features the coexistence of resorbing primary teeth and erupting permanent teeth, during which the first permanent molars emerge behind the primary second molars without predecessor resorption.[48][49] The eruption of permanent teeth begins around age 6 with the first molars, followed by incisors, premolars, canines, and second molars by age 12, with third molars typically emerging later in adolescence or early adulthood. Empirical timelines indicate lower central incisors erupt at 6-7 years, upper central incisors at 7-8 years, and first permanent molars at about 6 years for both arches. Factors such as arch space availability and jaw growth influence alignment during this transition, with insufficient space potentially leading to crowding. Primary tooth roots undergo resorption mediated by osteoclasts activated by signals from the underlying permanent tooth follicle, facilitating exfoliation as the permanent successor advances.[48][50][51] The mechanism of eruption involves coordinated bone remodeling, where the dental follicle governs osteoclast differentiation for alveolar bone resorption apical to the tooth and osteoblast activity for bone deposition coronal to it, enabling net upward movement at rates of about 1 mm per month pre-emergence. Gubernacular cords, remnants of the dental lamina connecting the permanent tooth follicle to the overlying gingiva, provide a guiding pathway and may contribute to directional forces via collagen fiber orientation. Post-emergence, the periodontal ligament attaches and further supports positioning into occlusion.[51][52] Humans exhibit diphyodonty, limited to two successive dentitions, unlike the continuous polyphyodont replacement in reptiles where the dental lamina persists for ongoing tooth generation. This limitation arises from the degradation of the dental lamina and loss of Sox2-expressing epithelial stem cells following the formation of permanent teeth, preventing further successional teeth. Epithelial rests of Malassez, derived from Hertwig's epithelial root sheath, persist but do not regenerate functional tooth-forming structures in adults, enforcing the single replacement set adapted to mammalian dietary and longevity patterns.[53][54]| Tooth Type | Upper Arch Eruption Age (years) | Lower Arch Eruption Age (years) |

|---|---|---|

| First Molar | 6-7 | 6-7 |

| Central Incisor | 7-8 | 6-7 |

| Lateral Incisor | 8-9 | 7-8 |

| First Premolar | 10-11 | 10-12 |

| Second Premolar | 10-12 | 11-12 |

| Canine | 11-12 | 9-10 |

| Second Molar | 12-13 | 11-13 |

Function

Mechanical roles in mastication

Human teeth perform mechanical roles in mastication by applying compressive, shearing, and grinding forces to fragment food particles, facilitating digestion through trituration and size reduction. Incisor teeth initiate the process via incisal edges that guide mandibular protrusion and penetration into food, enabling initial cutting and separation, while canine teeth contribute shearing actions during lateral excursions. Premolars and molars, with their cuspal inclines and interdigitating occlusal surfaces, optimize force distribution during grinding; cuspal-fossa contacts stabilize the occlusion and enhance particle comminution by concentrating forces on food bolus between opposing surfaces.[55][56] Occlusal forces during mastication peak in posterior regions, with molars typically bearing 200-500 N, varying by age, sex, and dentition integrity; for instance, mean maximum bite forces around 430 N have been recorded in adults. These forces arise from masseter and temporalis muscle contractions, transmitted through the dental arches to create shear and compressive stresses that exceed food's tensile strength, causing fracture along fault lines. Enamel's prismatic microstructure, with hardness approaching 5 GPa, resists abrasion from food particulates and opposing cusps, distributing localized stresses to prevent crack propagation into underlying dentin.[57][58] The periodontal ligament mediates biomechanical efficiency by providing viscoelastic damping, absorbing peak loads up to 10-20% of applied force, while embedded mechanoreceptors deliver proprioceptive feedback to the trigeminal nucleus, reflexively modulating jaw muscle activity to avert overload beyond 500-700 N thresholds that could fracture enamel or ligament fibers. This sensory control ensures adaptive force application, with rapid adjustments during chewing cycles averaging 1-2 Hz. Empirical evidence from dental microwear shows attritional facets on ancestral hominid molars, formed by sustained tooth-tooth contact during trituration of fibrous, abrasive diets, contrasting with reduced mechanical wear in modern populations due to softer foods, underscoring teeth's evolved capacity for high-cycle mechanical processing.[59][60]Contributions to speech and occlusion

Teeth facilitate the articulation of labiodental fricatives such as /f/ and /v/ by providing the upper incisors as a stable surface against which the lower lip approximates to generate turbulent airflow, a mechanism rooted in the typical overjet that minimizes muscular effort for these sounds.[61] Malocclusions disrupting incisor positioning or overjet can alter tongue and lip dynamics, leading to speech impediments like lisps, where empirical studies document increased misarticulation rates for sibilants (/s/, /z/) due to improper airflow channeling and contact points, as observed in cohorts with Class II or open bite patterns.[62][63] Dental occlusion refers to the alignment and contact of opposing teeth during jaw closure, with Class I occlusion defined as the normative molar relationship in which the mesiobuccal cusp of the maxillary first permanent molar occludes in the buccal groove of the mandibular first permanent molar, establishing a balanced transverse and sagittal foundation for functional contacts.[64] Centric relation, the reproducible maxillomandibular position independent of tooth contacts, aligns with centric occlusion to distribute occlusal forces evenly across the dentition, preventing localized overloads that could arise from discrepancies exceeding 1-2 mm, as quantified via cephalometric analyses measuring condylar positioning and skeletal angles.[65][66] This even loading in proper occlusion sustains bite stability by optimizing force vectors along the periodontal ligament and alveolar bone, thereby minimizing shear stresses and promoting long-term dentoalveolar integrity, with disruptions empirically linked to accelerated wear or joint strain in misaligned cases.[67] While aligned occlusion influences social perceptions of facial aesthetics, such effects derive causally from enhanced phonetic precision and mechanical equilibrium rather than isolated visual appeal.[68]Supporting Tissues

Periodontal ligament and gingiva

The periodontal ligament (PDL) is a fibrous connective tissue layer, typically 0.15 to 0.38 mm thick, that suspends the tooth root within the alveolar socket and transmits occlusal forces between the cementum and bone.[69] Composed primarily of type I collagen fibers arranged in principal bundles—such as the numerous oblique fibers that extend coronally from cementum to alveolar bone—the PDL facilitates shock absorption during masticatory loading, distributing forces to prevent excessive stress on hard tissues.[70] These fibers, embedded as Sharpey's fibers measuring 1-2 μm in width, integrate with mineralized surfaces to maintain structural continuity.[71] The PDL exhibits rapid collagen turnover, with half-lives ranging from 2.45 days in apical regions to 6.42 days in middle thirds under normal conditions, enabling adaptive remodeling to functional stimuli via fibroblast-mediated synthesis and degradation.[72] This dynamic matrix supports homeostasis by responding to mechanical cues, with collagen fibers averaging 45-55 nm in diameter providing viscoelastic properties essential for force dissipation.[70] The gingiva, a keratinized stratified squamous epithelium overlying dense connective tissue, encircles the cervical portion of teeth and contrasts with the non-keratinized, mobile alveolar mucosa by offering masticatory resilience and microbial resistance.[73] Attached gingiva, bounded by the mucogingival junction, adheres firmly to periosteum, while the gingival sulcus—a 0.5-1.5 mm deep V-shaped crevice—together with the basal junctional epithelium, establishes a selective barrier that restricts subgingival bacterial ingress under physiological conditions.[73] In gingival homeostasis, cytokines such as interleukins and tumor necrosis factor mediate localized inflammatory signaling to regulate epithelial integrity and connective tissue remodeling in response to commensal microbiota, preventing dysbiosis without progressing to overt pathology.[74] This cytokine network, produced by resident fibroblasts and immune cells, balances pro- and anti-inflammatory pathways to sustain the gingival seal and PDL attachment.[75]Alveolar bone and its role

The alveolar bone, or alveolar process, forms the specialized ridges of the maxilla and mandible that contain the tooth sockets, known as alveoli, which encase the roots and provide anchorage via the periodontal ligament.[76][77] This bone consists of a thin cribriform plate (alveolar bone proper) lined with Sharpey's fibers and supported by trabecular bone, enabling dynamic integration with teeth under functional loads.[78] Alveolar bone demonstrates adaptive remodeling in accordance with Wolff's law, altering its mass and architecture in response to mechanical stresses from mastication and occlusion.[79] This process involves osteoclasts resorbing bone on compression sides and osteoblasts depositing new lamellar bone on tension sides, optimizing density and strength for intermittent, multidirectional forces.[80] The crestal height is maintained through this remodeling to support the biologic width, preserving approximately 2 mm from the alveolar crest to the gingival attachment for periodontal stability.[81] Compared to long bones, alveolar bone exhibits higher turnover rates and a more trabecular composition with thinner cortical layers, adaptations suited to shock absorption during chewing rather than sustained weight-bearing.[82] Its vascular supply arises from periapical branches of the inferior alveolar artery in the mandible and posterior superior alveolar artery in the maxilla, with nutrient foramina in the cribriform plate facilitating blood flow through marrow spaces and periodontal ligament vessels.[83] Innervation derives from the inferior alveolar nerve (mandibular division of trigeminal) and superior alveolar nerves, providing sensory feedback that modulates remodeling via mechanotransduction.[84] Post-tooth extraction, alveolar bone undergoes physiological resorption as a adaptive response to the loss of functional loading, with horizontal width diminishing by 25-60% and vertical height by 11-22% within the first year, primarily driven by reduced osteoblast activity and unopposed osteoclast function.[79][85] This remodeling reflects the bone's dependency on dental stimuli, reverting toward basal bone contours without pathological implication.[79]Pathology

Etiology of tooth decay and caries

Dental caries, commonly known as tooth decay, results from a dysbiotic shift in the oral microbiome, where acidogenic and aciduric bacteria in supragingival biofilms metabolize fermentable carbohydrates to produce organic acids, predominantly lactic acid, leading to localized enamel demineralization.[86][87] This process is initiated when plaque pH falls below the critical threshold of approximately 5.5, at which the solubility of enamel's hydroxyapatite increases, allowing calcium and phosphate ions to dissolve from the mineral phase.[88][89] Streptococcus mutans serves as a primary etiological contributor due to its proficiency in carbohydrate fermentation, glucan synthesis for biofilm adhesion, and acid tolerance, enabling dominance in low-pH environments.[90][91] These bacteria hydrolyze sucrose and other fermentable carbohydrates—encompassing monosaccharides, disaccharides, and starches—via enzymes like glucosyltransferases and amylases, yielding acids that diffuse into enamel prism sheaths.[92] Empirical observations confirm lesion onset as subsurface demineralization, appearing clinically as opaque white spot lesions when mineral loss reaches 30-50%, progressing to surface breakdown and cavitation under sustained acid challenge exceeding remineralization capacity.[86] The dynamics of plaque pH, as depicted by the Stephan curve, demonstrate a precipitous drop to 4.5-5.2 within 5-10 minutes post-carbohydrate ingestion, followed by gradual recovery over 30-60 minutes via salivary bicarbonate buffering and clearance.[93][94] Frequent substrate availability from snacking patterns exacerbates risk by prolonging subcritical pH intervals, impeding salivary-mediated ion replenishment, whereas consolidated meal consumption permits fuller pH normalization.[95][96] This frequency-dependent causality underscores that total carbohydrate volume alone inadequately predicts caries; repeated, intermittent exposures amplify biofilm acidogenicity beyond isolated high-load events.[97][98]Trauma and wear mechanisms

Dental fractures from trauma are classified by the Ellis system based on the depth of crown involvement. Ellis Class I fractures are limited to enamel, appearing as minor chipping with rough edges and no pulpal exposure or sensitivity.[99] Ellis Class II fractures extend through enamel into dentin, often causing thermal sensitivity due to exposed dentinal tubules.[99] Ellis Class III fractures reach the pulp, presenting with hemorrhage, severe pain, and risk of pulp necrosis from bacterial invasion.[100] These classifications guide immediate management, with deeper fractures requiring pulp protection to prevent complications.[101] Biomechanically, enamel withstands compressive loads up to approximately 363 MPa before failure, owing to its highly mineralized, prismatic structure oriented to resist masticatory forces.[102] However, enamel exhibits anisotropic weakness in tension, fracturing at stresses as low as 10-11.4 MPa perpendicular to prism orientation, which explains susceptibility to shear and bending during impacts like falls or assaults.[103] Traumatic forces exceeding these thresholds propagate cracks from the enamel surface inward, often exacerbated by the tooth's lack of collagen for toughness compared to dentin.[104] Tooth wear encompasses attrition and erosion as distinct non-carious mechanisms. Attrition arises from chronic mechanical tooth-to-tooth contact, particularly via bruxism—repetitive grinding or clenching generating forces up to 700 N during sleep or wakefulness—resulting in flattened incisal edges and occlusal facets with interproximal wear.[105] Bruxism's etiology involves multifactorial triggers like occlusal interferences and stress, leading to progressive loss of cuspal height without chemical softening.[106] Erosion, conversely, is a chemical process driven by extrinsic acids (e.g., from citrus or carbonated beverages) or intrinsic sources (e.g., gastroesophageal reflux), demineralizing enamel through pH-dependent hydroxyapatite dissolution below 5.5 without bacterial mediation.[107] This yields smooth, cupped lesions on palatal or occlusal surfaces, distinguishable from attrition's sharp, mechanically abraded margins, and progresses faster in low-salivary buffer conditions.[108] In forensic odontology, bite mark analysis seeks to link dental trauma patterns to suspects via arch impressions, but reliability is undermined by skin elasticity causing distortions, postmortem changes, and high intra- and inter-individual tooth variability, with empirical validation lacking and error rates elevated in controlled studies.[109][110] Peer-reviewed assessments conclude it fails foundational scientific criteria for positive identification, limiting utility to exclusionary evidence at best.[109]Inflammatory and infectious conditions

Pulpitis refers to inflammation of the dental pulp, primarily resulting from bacterial invasion originating in carious lesions that penetrate dentin tubules, allowing microbial byproducts and pathogens to reach the pulp tissue.[111] This ingress triggers an inflammatory response, with reversible pulpitis characterized by mild, transient symptoms that subside upon removal of the irritant, such as early caries excavation, due to the pulp's capacity for limited repair via odontoblast activity.[112] In contrast, irreversible pulpitis arises when bacterial proliferation overwhelms host defenses, leading to persistent hyperalgesia, necrosis, and potential extension beyond the pulp, as evidenced by histological findings of extensive microbial colonization in affected tissues.[113] Apical periodontitis develops as a periapical inflammatory lesion consequent to pulp necrosis and bacterial extrusion through the apical foramen, representing the host's adaptive immune response aimed at containing infection via granulomatous tissue formation and bone resorption.[114] Immune cells, including lymphocytes and macrophages, infiltrate the area in reaction to persistent microbial challenge from the root canal system, producing cytokines and reactive oxygen species that limit bacterial dissemination but can perpetuate chronic inflammation if unresolved.[115] Empirical data from radiographic and microbiological studies confirm that untreated endodontic infections sustain this process, with host factors modulating lesion size and symptomatic progression.[116] Dental abscesses form through accumulation of pus—comprising neutrophils, bacteria, and tissue debris—in periapical or periodontal spaces, typically as a suppurative extension of untreated pulpitis or periodontitis, exerting pressure on surrounding structures and causing acute pain.[117] Primary management emphasizes incision and drainage to alleviate pressure and eliminate necrotic content, with root canal therapy or extraction addressing the source, as surgical intervention alone resolves most localized cases without reliance on systemic antibiotics, which show limited efficacy against walled-off polymicrobial foci and risk fostering resistance.[118][117] Systemic conditions such as diabetes mellitus exacerbate inflammatory dental infections by impairing neutrophil function and wound healing through hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress and delayed immune modulation, increasing abscess severity and tooth loss risk by up to 63% in affected individuals per meta-analytic reviews.[119] Poor oral hygiene accelerates bacterial ingress as a proximal cause, yet empirical cohort studies highlight diabetes' causal role in amplifying infection persistence via vascular complications and reduced salivary antimicrobial defenses, independent of hygiene alone.[120][121]Abnormalities

Developmental defects