Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Type design

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2011) |

Type design is the art and process of designing typefaces. This involves drawing each letterform using a consistent style. The basic concepts and design variables are described below.

A typeface differs from other modes of graphic production such as handwriting and drawing in that it is a fixed set of alphanumeric characters with specific characteristics to be used repetitively. Historically, these were physical elements, called sorts, placed in a wooden frame; modern typefaces are stored and used electronically. It is the art of a type designer to develop a pleasing and functional typeface. In contrast, it is the task of the typographer (or typesetter) to lay out a page using a typeface that is appropriate to the work to be printed or displayed.

Type designers use the basic concepts of strokes, counter, body, and structural groups when designing typefaces. There are also variables that type designers take into account when creating typefaces. These design variables are style, weight, contrast, width, posture, and case.

History

[edit]The technology of printing text using movable type was invented in China,[1] but the vast number of Chinese characters, and the esteem with which calligraphy was held, meant that few distinctive, complete typefaces were created in China in the early centuries of printing.

Gutenberg's most important innovation in the mid 15th century development of his press was not the printing itself, but the casting of Latinate types. Unlike Chinese characters, which are based on a uniform square area, European Latin characters vary in width, from the very wide "M" to the slender "l". Gutenberg developed an adjustable mold which could accommodate an infinite variety of widths. From then until at least 400 years later, type started with cutting punches, which would be struck into a brass "matrix". The matrix was inserted into the bottom of the adjustable meld and the negative space formed by the mold cavity plus the matrix acted as the master for each letter that was cast. The casting material was an alloy usually containing lead, which had a low melting point, cooled readily, and could be easily filed and finished. In those early days, type design had to not only imitate the familiar handwritten forms common to readers, but also account for the limitations of the printing process, such as the rough papers of uneven thicknesses, the squeezing or splashing properties of the ink, and the eventual wear on the type itself.

Beginning in the 1890s, each character was drawn in a very large size for the American Type Founders Corporation and a few others using their technology—over a foot (30 cm) high. The outline was then traced by a Benton pantograph-based engraving machine with a pointer at the hand-held vertex and a cutting tool at the opposite vertex down to a size usually less than a quarter-inch (6 mm). The pantographic engraver was first used to cut punches, and later to directly create matrices.

In the late 1960s through the 1980s, typesetting moved from metal to photo composition. During this time, type design made a similar transition from physical matrixes to hand drawn letters on vellum or mylar and then the precise cutting of "rubyliths". Rubylith was a common material in the printing trade, in which a red transparent film, very soft and pliable, was bonded to a supporting clear acetate. Placing the ruby over the master drawing of the letter, the craftsman would gently and precisely cut through the upper film and peel the non-image portions away. The resulting letterform, now existing as the remaining red material still adhering to the clear substrate, would then be ready to be photographed using a reproduction camera.

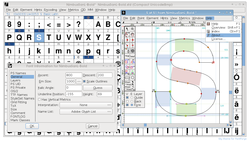

With the coming of computers, type design became a form of computer graphics. Initially, this transition occurred with a program called Ikarus around 1980, but widespread transition began with programs such as Aldus Freehand and Adobe Illustrator, and finally to dedicated type design programs called font editors, such as Fontographer and FontLab. This process occurred rapidly: by the mid-1990s, virtually all commercial type design had transitioned to digital vector drawing programs.

Each glyph design can be drawn or traced by a stylus on a digitizing board, or modified from a scanned drawing, or composed entirely within the program itself. Each glyph is then in a digital form, either in a bitmap (pixel-based) or vector (scalable outline) format. A given digitization of a typeface can easily be modified by another type designer; such a modified font is usually considered a derivative work, and is covered by the copyright of the original font software.

Type design could be copyrighted typeface by typeface in many countries, though not the United States. The United States offered and continues to offer design patents as an option for typeface design protection.[2]

Basic concepts

[edit]

Stroke

[edit]The shape of designed letterforms and other characters are defined by strokes arranged in specific combinations. This shaping and construction has a basis in the gestural movements of handwriting. The visual qualities of a given stroke are derived from factors surrounding its formation: the kind of tool used, the angle at which the tool is dragged across a surface, and the degree of pressure applied from beginning to end. The stroke is the positive form that establishes a character's archetypal shape.[3]: 49

Counter

[edit]The spaces created between and around strokes are called counters (also known as counterforms). These negative forms help to define the proportion, density, and rhythm of letterforms. The counter is an integral element in Western typography, however this concept may not apply universally to non-Western typographic traditions. More complex scripts, such as Chinese, which make use of compounding elements (radicals) within a single character may additionally require consideration of spacing not only between characters but also within characters.[4]

Body

[edit]The overall proportion of characters, or their body, considers proportions of width and height for all cases involved (which in Latin are uppercase and lowercase), and individually for each character. In the former case, a grid system is used to delineate vertical proportions and gridlines (such as the baseline, mean line/x-height, cap line, descent line, and ascent line). In the latter case, letterforms of a typeface may be designed with variable bodies, making the typeface proportional, or they may be designed to fit within a single body measure, making the typeface fixed width or monospaced.

Structural groups

[edit]When designing letterforms, characters with analogous structures can be grouped in consideration of their shared visual qualities. In Latin, for example, archetypal groups can be made on the basis of the dominant strokes of each letter: verticals and horizontals (E F H L T), diagonals (V W X), verticals and diagonals (K M N Y), horizontals and diagonals (A Z), circular strokes (C O Q S), circular strokes and verticals (B D G P R U), and verticals (I J).

Design variables

[edit]Type design takes into consideration a number of design variables which are delineated based on writing system and vary in consideration of functionality, aesthetic quality, cultural expectations, and historical context.[3]: 48

Style

[edit]Style describes several different aspects of typeface variability historically related to character and function. This includes variations in:

- Structural class (such as serif, sans serif, and script typefaces)

- Historical class (such as oldstyle, transitional, neoclassical, grotesque, humanist, etc.)

- Relative neutrality (ranging from neutral typefaces to stylized typefaces)

- Functional use (such as text, display, and caption typefaces)

Weight

[edit]

Weight refers to the thickness or thinness of a typeface's strokes in a global sense. Typefaces usually have a default medium, or regular, weight which will produce the appearance of a uniform grey value when set in text. Categories of weight include hairline, thin, extra light, light, book, regular/medium, semibold, bold, black/heavy, and extra black/ultra.

Variable fonts are computer fonts that are able to store and make use of a continuous range of weight (and size) variants of a single typeface.

Contrast

[edit]Contrast refers to the variation in weight that may exist internally within each character, between thin strokes and thick strokes. More extreme contrasts will produce texts with more uneven typographic color. At a smaller scale, strokes within a character may individually also exhibit contrasts in weight, which is called modulation.

Width

[edit]Each character within a typeface has its own overall width relative to its height. These proportions may be changed globally so that characters are narrowed or widened. Typefaces that are narrowed are called condensed typefaces, while those that are widened are called extended typefaces.

Posture

[edit]Letterform structures may be structured in a way that changes the angle between upright stem structures and the typeface's baseline, changing the overall posture of the typeface. In Latin script typefaces, a typeface is categorized as a Roman when this angle is perpendicular. A forward-leaning angle produces either an Italic, if the letterforms are designed with reanalyzed cursive forms, or an oblique, if the letterforms are slanted mechanically. A back-leaning angle produces a reverse oblique, or backslanted, posture.

Case

[edit]

A proportion of writing systems are bicameral, distinguishing between two parallel sets of letters that vary in use based on prescribed grammar or convention. These sets of letters are known as cases. The larger case is called uppercase or capitals (also known as majuscule) and the smaller case is called lowercase (also known as minuscule). Typefaces may also include a set of small capitals, which are uppercase forms designed in the same height and weight as lowercase forms. Other writing systems are unicameral, meaning only one case exists for letterforms. Bicameral writing systems may have typefaces with unicase designs, which mix uppercase and lowercase letterforms within a single case.

Principles

[edit]The design of a legible text-based typeface remains one of the most challenging assignments in graphic design. The even visual quality of the reading material being of paramount importance, each drawn character (called a glyph) must be even in appearance with every other glyph regardless of order or sequence. Also, if the typeface is to be versatile, it must appear the same whether it is small or large. Because of optical illusions that occur when we apprehend small or large objects, this entails that in the best fonts, a version is designed for small use and another version is drawn for large, display, applications. Also, large letterforms reveal their shape, whereas small letterforms in text settings reveal only their textures: this requires that any typeface that aspires to versatility in both text and display, needs to be evaluated in both of these visual domains. A beautifully shaped typeface may not have a particularly attractive or legible texture when seen in text settings.

Spacing is also an important part of type design. Each glyph consists not only of the shape of the character, but also the white space around it. The type designer must consider the relationship of the space within a letter form (the counter) and the letter spacing between them.

Designing type requires many accommodations for the quirks of human perception, "optical corrections" required to make shapes look right, in ways that diverge from what might seem mathematically right. For example, round shapes need to be slightly bigger than square ones to appear "the same" size ("overshoot"), and vertical lines need to be thicker than horizontal ones to appear the same thickness. For a character to be perceived as geometrically round, it must usually be slightly "squared" off (made slightly wider at the shoulders). As a result of all these subtleties, excellence in type design is highly respected in the design professions.

Profession

[edit]Type design is performed by a type designer. It is a craft, blending elements of art and science. In the pre-digital era it was primarily learned through apprenticeship and professional training within the industry. Since the mid-1990s it has become the subject of dedicated degree programs at a handful of universities, including the MA Typeface Design at the University of Reading (UK) and the Type Media program at the KABK (Royal Academy of Art in the Hague). At the same time, the transition to digital type and font editors which can be inexpensive (or even open source and free) has led to a great democratization of type design; the craft is accessible to anyone with the interest to pursue it, nevertheless, it may take a very long time for the serious artist to master.

References

[edit]- ^ Needham, Joseph (1994). The Shorter Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 4. Cambridge University Press. p. 14. ISBN 9780521329958.

Bi Sheng... who first devised, about 1045, the art of printing with movable type

- ^ "Types of Patents". United States Patent and Trademark Office. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ^ a b Samara, Timothy (2018). Letterforms: Typeface Design From Past to Future. Minneapolis: Rockport Publishers. ISBN 978-1631594731.

- ^ Takagi, Mariko (2012). "Typography between Chinese complex characters and Latin Letters". ATypI 2012 Hong Kong: 11.

Further reading

[edit]- Stiebner, Erhardt D. & Dieter Urban. Initials and Decorative Alphabets. Poole, England: Blandford Press, 1985. ISBN 0-7137-1640-1

Type design

View on GrokipediaHistory

Origins in antiquity

The earliest forms of writing that influenced type design originated in ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt, where pictographic systems evolved into phonetic scripts. Sumerian cuneiform, invented around 3200 BCE in the city of Uruk, began as impressions of clay tokens representing goods for accounting purposes, transitioning by 3100 BCE into two-dimensional pictographs on clay tablets that abstracted quantities and objects.[5] By circa 3000 BCE, phonetic signs were introduced to transcribe personal names and spoken elements, blending logograms with syllabic representations to expand beyond mere enumeration into narrative and administrative texts.[5] Similarly, Egyptian hieroglyphs emerged around the late 4th millennium BCE as pictographs depicting objects like eyes or reeds, gradually incorporating phonetic principles akin to rebus puzzles to denote sounds or words, enabling the expression of complex ideas in religious and royal inscriptions.[6] The Greek alphabet, adapted from the Phoenician script in the 8th century BCE, introduced vowels and phonetic consistency, forming the basis for subsequent Western letterforms with straight-lined majuscule capitals written between guidelines.[7] This evolved into the Roman alphabet by the 1st century BCE, where early lapidary inscriptions featured equal-width letters without serifs, later refined with thick-and-thin strokes and serifs derived from brush techniques transferred to stone carving.[7] By the 4th century CE, Roman scripts included refined majuscule forms for monumental use and emerging minuscule variants in cursive hands, distinguishing between uppercase for emphasis and lowercase precursors for speed in manuscripts.[8] A prime example of ideal Roman capitals is the inscription on Trajan's Column, dedicated in 113 CE, which employs capitalis monumentalis with vertical strokes twice the thickness of horizontals and a letter height of 8.5–9 times the stroke width, setting a proportional standard for enduring letterform elegance.[9] In early Christian texts from the 4th century CE, uncial and half-uncial scripts bridged majuscule and minuscule forms, facilitating the copying of scriptures across Europe. Uncial script, derived from Old Roman Cursive, featured rounded, curved letters like A, D, and E written at a 90-degree angle between two lines, allowing broader text blocks and appearing in works such as 4th-century palimpsests of Cicero and 5th-century copies of Livy.[10] Half-uncial, evolving from New Roman Cursive, introduced ascenders and descenders in letters like D and P, varying heights for efficiency and used in 6th-century manuscripts such as those of St. Hilary, marking a shift toward compact, readable minuscule styles in monastic settings.[10] During the Carolingian Renaissance of the 8th–9th centuries, scribes in monastic scriptoria standardized Carolingian minuscule as a clear, legible script blending elements from Roman cursive, half-uncial, and regional variants like Merovingian, promoting uniformity in copying classical and biblical texts.[11] Under Charlemagne's reforms, scribes such as those at the Palace School of Aachen reduced ligatures and regional differences, enabling faster production of over 7,000 surviving manuscripts that preserved antiquity's knowledge for lay and clerical use.[12] This script, with its balanced ascenders, descenders, and four-line structure, directly influenced humanist minuscule and became the foundational precursor to modern lowercase letters in Roman typefaces.[12]Printing press and metal type

The invention of movable type by Johannes Gutenberg around 1450 revolutionized printing by enabling the mass production of texts through reusable metal characters cast from an alloy of lead, tin, and antimony, which provided durability and uniformity far superior to earlier wooden types.[13][14] This innovation, developed in Mainz, Germany, combined with the screw press, allowed for precise inking and impression, standardizing letterforms and facilitating the dissemination of knowledge across Europe.[15][16] Gutenberg's approach emphasized craftsmanship in typefounding, where punches were hand-engraved to strike matrices, from which molten alloy was poured to create the sorts used in composition.[17] In the 16th century, punchcutting techniques advanced significantly through artisans like Claude Garamond in Paris, who introduced greater exactness and uniformity in engraving punches, enabling the production of refined humanist typefaces modeled on Italian Renaissance calligraphy.[18] Garamond's designs, such as his Grec du Roi, featured subtle stroke variations and open counters that enhanced legibility and aesthetic harmony, influencing subsequent Roman types by prioritizing readability for scholarly texts.[19] These techniques required meticulous handwork, with punchcutters using files and gravers to shape steel tools that ensured consistent type across large editions, marking a shift toward professional type design as a distinct craft. A pivotal development occurred in the 1490s when printer Aldus Manutius in Venice, collaborating with punchcutter Francesco Griffo, introduced the first Roman typeface and italic as companion styles, compacting letterforms to fit more text on pages for affordable pocket editions of classical works.[21][22] The Roman drew from humanist scripts for clarity, while italic mimicked cursive handwriting, adding elegance and slope without sacrificing reproducibility; these innovations set standards for book typography, blending functionality with classical proportions.[23] By the 18th century, type design evolved from old style faces, exemplified by William Caslon's English types introduced around 1722, which retained the moderate contrast and bracketed serifs of earlier humanists but achieved warmer, more organic forms suited to British printing traditions.[24] Caslon's work emphasized practicality for legal and religious texts, with subtle irregularities that evoked handwritten warmth while maintaining metal type's precision.[25] This old style period transitioned into the late 18th century with transitional designs like John Baskerville's typeface of 1757, which increased stroke contrast, vertical stress, and refined serifs, bridging organic old styles and the sharper moderns through innovations in paper and ink that allowed crisper impressions.[26][21] Baskerville's Birmingham-foundry types, with their larger x-heights and transitional sharpness, reflected Enlightenment ideals of clarity and rationality in printing.[26] The modern classification emerged in the late 18th and early 19th centuries with faces like Firmin Didot's designs from the 1780s onward, characterized by extreme high-contrast between thick and thin strokes, unbracketed hairline serifs, and geometric precision, which amplified neoclassical elegance for French luxury printing.[27] Didot's innovations, paralleling Giambattista Bodoni's Italian efforts, pushed type toward abstraction, with vertical axis alignment and minimal curves that suited the era's emphasis on symmetry and speed in production.[28] This evolution from old style's fluidity to transitional balance and modern rigidity standardized typeface families, enabling punchcutters to produce scalable weights while preserving the metal type's tactile craftsmanship.[21][26] In the 19th century, the rise of advertising spurred slab serif types, first commercialized by Vincent Figgins in London around 1815 under the name Antique, featuring bold, block-like serifs that provided visual impact on posters and broadsides amid industrial expansion.[29] These Egyptian-style faces, with their monolinear thickness and mechanical robustness, contrasted the delicacy of modern serifs, thriving in wood type for large-scale display and reflecting the era's demand for attention-grabbing, durable forms in commercial printing.[30][31] Slab serifs thus extended metal type's versatility into mass media, prioritizing boldness over subtlety in an age of rapid urbanization and print proliferation.Phototypesetting and early digital

Phototypesetting marked a pivotal shift in the mid-20th century, transitioning from the physical constraints of metal type to photographic methods that revolutionized type reproduction. Developed in the late 1940s and early 1950s, this technology used light to expose images of type characters onto photographic film or paper, eliminating the need for casting individual metal pieces. A key example was the Linofilm system introduced by Mergenthaler Linotype in 1950, with its electronic version debuting in 1954, capable of producing up to 43,200 characters per hour through shutter-based exposure mechanisms.[32] This innovation allowed for unprecedented flexibility, such as curved baselines for circular text arrangements and instantaneous scaling to various sizes without recasting, vastly improving efficiency and creative possibilities over the rigid metal type era.[32] The rise of phototypesetting also amplified the influence of certain typefaces, particularly Helvetica, which gained dominance during the 1960s as a cornerstone of the Swiss or International Typographic Style. Released in 1957 by Haas Type Foundry, Helvetica's clean, neutral sans-serif design aligned perfectly with the style's emphasis on clarity, asymmetry, and grid-based layouts, making it ideal for photographic reproduction in advertising, signage, and print media.[33] By the 1960s, its versatility in phototypesetting workflows contributed to widespread adoption, symbolizing modernity and objectivity in graphic design across Europe and North America.[33] As phototypesetting evolved into early digital systems in the 1970s and 1980s, foundational tools like Donald Knuth's Metafont emerged, introducing parametric descriptions for generating scalable letterforms through mathematical algorithms rather than fixed images. Initiated in 1977 and first implemented in 1979, Metafont allowed designers to define fonts programmatically, influencing subsequent digital typography by prioritizing adaptability over static bitmaps.[34] Concurrently, bitmap fonts became prominent with the Apple Macintosh's launch in 1984, featuring pixel-based designs like Susan Kare's Chicago typeface, which provided accessible on-screen rendering for personal computing but was limited to fixed resolutions. These early digital approaches, however, faced significant challenges in kerning—the fine adjustment of space between character pairs—due to low-resolution outputs, device-dependent rendering, and the need for manual interventions in systems like Ikarus and LIP, often resulting in inconsistent spacing across platforms.[35] Key advancements addressed these limitations through scalable outline formats. Adobe's PostScript, developed from 1982 to 1984, introduced vector-based descriptions that enabled high-quality, resolution-independent rendering on laser printers and displays, fundamentally enabling desktop publishing by allowing precise control over curves and spacing.[36] Building on this, the TrueType format, jointly developed by Apple and Microsoft and released in 1991 with System 7, provided cross-platform compatibility with simplified hinting for better on-screen display, reducing reliance on proprietary rasterization and improving kerning portability.[37] These developments bridged phototypesetting's photographic precision with digital scalability, setting the stage for broader typographic innovation.Modern digital and open-source era

The modern digital era of type design, beginning in the late 1990s, marked a shift toward outline-based font formats that enabled scalable, vector-based glyphs suitable for digital displays and printing. OpenType, jointly developed by Adobe and Microsoft, emerged as a pivotal standard in 1996, extending the TrueType format to include advanced typographic features such as ligatures—combined glyphs for improved readability—and glyph variants for contextual alternates, allowing designers greater control over linguistic nuances across scripts.[38][39] This format's cross-platform compatibility and support for complex layouts facilitated the integration of diverse writing systems, democratizing access to professional-grade typography beyond proprietary systems. Unicode's adoption, starting with its initial version in 1991, revolutionized type design by providing a universal encoding system that transcended Latin alphabets, encompassing scripts from Arabic to Devanagari and beyond. By 2025, Unicode 17.0 encoded 159,801 characters across 172 scripts, enabling font families to support global multilingualism without fragmentation.[40] This standardization encouraged type designers to create inclusive fonts that handle bidirectional text, complex shaping, and right-to-left rendering, fostering equitable digital communication worldwide.[41] Open-source initiatives further accelerated accessibility in the 21st century, empowering independent designers with free tools and resources. Launched in 2010, Google Fonts provided a vast, no-cost library of web-optimized typefaces, promoting open licensing and rapid iteration in digital projects.[42] Complementary efforts like the Noto project, initiated by Google, delivered comprehensive font coverage for over 1,000 languages and 150 writing systems, including specialized variants for emoji to ensure "no tofu" (unrendered placeholders) in multilingual interfaces.[43] Tools such as FontForge, an open-source editor developed since 2000, allowed users to create and modify outline fonts without commercial software, supporting formats like OpenType and fostering community-driven contributions to Unicode-compliant designs.[44] Recent trends emphasize flexibility and multimedia integration, with variable fonts introduced in 2016 as an OpenType extension enabling continuous interpolation of attributes like weight, width, and slant within a single file, reducing bandwidth while enhancing responsive web typography.[45] Simultaneously, emoji and icon incorporation has become standard in type families, as seen in Noto Emoji's support for full-color, animated Unicode symbols, blending pictographic elements with text for expressive, accessible digital content.[46] These advancements reflect a collaborative, inclusive ethos, where open-source communities drive innovation in scalable, globally relevant type design.Anatomy and Basic Concepts

Letterform components

Letterform components form the foundational elements of individual glyphs, defining their structure and visual identity within a typeface. These parts, analogous to anatomical features, include primary strokes and decorative accents that ensure coherence across an alphabet. In Latin-based scripts, key components encompass stems, bowls, serifs, and terminals, each contributing to the glyph's form and readability.[47] The stem serves as the primary vertical or diagonal stroke in a letterform, providing structural support; for instance, in the lowercase 'b', the stem forms the upright ascender to which the bowl attaches. The bowl, a curved, enclosed or semi-enclosed form, creates the rounded body of letters like the 'a' and 'g', where it defines the upper loop in 'a' and the open counter in single-story 'g' variants. Terminals mark the endpoints of strokes without serifs, often appearing as subtle flares or curves, such as the tapered finish on the arm of a lowercase 'r'. These elements interact to maintain optical balance, with broader stroke variations influencing their proportions.[47] Serifs are short perpendicular or angled strokes appended to the ends of main stems and arms, enhancing elegance or emphasis in letterforms. They are classified by their attachment to the stem: bracketed serifs feature a curved or filleted transition, as seen in the old-style typeface Garamond, where the serif gently arcs into the vertical stroke for a humanistic flow. In contrast, unbracketed or slab serifs connect abruptly at a right angle with thick, rectangular projections, exemplified by typefaces like Rockwell, which convey a bold, mechanical presence suited to display uses.[1] Beyond Latin scripts, letterform components adapt to linguistic needs, incorporating diacritics and script-specific features. In accented Latin characters, diacritics such as the acute (´) or umlaut (¨) overlay base glyphs to denote pronunciation, positioned above vowels like 'é' without altering the core stem or bowl. Arabic script introduces hooks and loops as integral curves; for example, the 'noon' (ن) ends in a hooked tail, while 'ghayn' (غ) includes a looped descender, with dots as diacritics stacked above or below to distinguish forms like 'ba' (ب) from 'ta' (ت). These elements ensure phonetic clarity in cursive connections.[48][49] The lowercase 'e' exemplifies these components' interplay, as the most frequent letter in English text, comprising a vertical stem on the left, a rounded bowl enclosing the counter, a horizontal crossbar, and often subtle terminals at the bar's ends. Its design, with the bar typically horizontal in traditional faces like Garamond, sets the rhythmic tone for the entire typeface, influencing legibility in extended reading.[50][1]Strokes, counters, and terminals

In type design, strokes form the foundational linear elements of letterforms, categorized by orientation and function. Vertical strokes, known as stems, provide the primary upright structure in letters such as "H" or "l," while horizontal strokes, often called bars or crossbars, connect elements horizontally, as seen in "A" or "e." Diagonal strokes, referred to as arms or legs, introduce angled lines for dynamic forms, exemplified in "N" or "K."[51] These stroke types contribute to the overall rhythm and stability of a typeface, with their proportions influencing visual balance.[52] Modulation describes the variation in stroke thickness, particularly the transition from thin to thick along curved or angled lines, which is a hallmark of transitional serif typefaces. In these designs, such as Baskerville, the axis of curved strokes shows subtle inclination, with pronounced contrast between thick verticals and thinner horizontals or diagonals, enhancing elegance and readability without extreme stress.[51][53] This modulation differentiates transitional styles from old-style serifs, where contrasts are milder, by emphasizing vertical stress while maintaining harmonious flow.[54] Counters represent the negative spaces enclosed or partially enclosed by strokes, playing a critical role in a typeface's perceived weight and openness. Enclosed counters are fully bounded areas, as in the circular space of "o" or "d," creating a sense of solidity, whereas open counters feature partial enclosures, like the curved interior of "c" or "n," which promote an airy feel.[51] The size and shape of counters significantly influence perceived weight: larger counters make a typeface appear lighter and more breathable, while smaller ones convey density and robustness, affecting how the overall design is interpreted at a glance.[55] Counter size also impacts legibility, with appropriate proportions ensuring clear distinction of forms without overwhelming the positive stroke areas.[51] Terminals are the endpoints of strokes that lack serifs, varying in form to define a typeface's character and style. Ball terminals feature a rounded, circular flourish, adding softness to endings in letters like "a" or "f"; slab terminals present blunt, rectangular caps for a bold, mechanical appearance; and tapered terminals narrow gradually to a point, lending precision and elegance.[56] In geometric sans-serif fonts like Futura, terminals often adopt tapered or subtly rounded forms, aligning with the typeface's emphasis on clean, modernist geometry and contributing to its crisp, impersonal aesthetic.[57] These variations allow designers to subtly modulate the typeface's personality, from playful to structured, while preserving legibility across weights.[51]Spatial elements like baseline and x-height

In type design, the baseline serves as the foundational imaginary horizontal line upon which the majority of letters rest, ensuring consistent alignment across a line of text.[58] Letters with descenders, such as 'g', 'p', and 'y', extend below this line, while most other characters align their bottoms to it.[58] To achieve optical evenness, especially with curved or circular forms like the lowercase 'o' or 'c', designers incorporate a subtle overshoot, allowing these elements to dip slightly below the baseline; this compensates for the perceptual shortening of curves relative to straight edges, preventing visual misalignment.[59] The x-height represents the vertical distance from the baseline to the top of the lowercase 'x', defining the core height of lowercase letters exclusive of ascenders and descenders.[58] This metric varies widely among typefaces even at the same point size, influencing perceived scale and legibility; for example, Helvetica employs a tall x-height relative to its cap height, fostering a modern, open aesthetic that enhances readability in diverse applications from signage to interfaces.[60] Additional spatial metrics include cap height, the distance from the baseline to the tops of uppercase letters like 'H', which often aligns closely but not identically with ascender peaks.[58] Ascenders denote the extensions above the x-height in letters such as 'b' and 'k', while descenders mark the portions below the baseline in letters like 'j'; the ratios between these elements, x-height, and cap height establish the typeface's vertical rhythm and bounding box.[58] For proportional scaling and spacing, em and en units provide relative measures: the em equals the typeface's point size (e.g., 10 units in 10-point type), and the en is half an em, enabling scalable consistency in kerning, leading, and layout.[58] In Times New Roman, the x-height measures roughly 70% of the cap height, a proportion that supports efficient readability in extended text by balancing compactness with clarity.Structural groupings in alphabets

In type design, alphabets are structurally grouped to maintain visual and functional coherence, with roman and blackletter representing two foundational categories derived from historical writing traditions. Roman type, characterized by upright letterforms with even strokes and often subtle serifs, evolved from classical inscriptions and early humanist calligraphy, providing a balanced, readable structure for extended text.[1] In contrast, blackletter, also known as gothic, features dense, angular forms with thick vertical strokes and minimal counters, originating from medieval manuscripts penned at a 45-degree angle with a broad nib, which creates a more compressed and ornate appearance suited to ceremonial or historical contexts.[1] These groupings ensure that letterforms within each category share proportional relationships, such as consistent x-heights and baselines, to support legibility across compositions.[54] Italic serves as a slanted companion to roman, designed not merely as a stylistic variant but as an integral structural pair that enhances textual hierarchy through subtle cursiveness and axis tilt, typically around 5 to 12 degrees.[54] Historically introduced as standalone fonts in the 16th century, italics now form a matched nuclear family with roman, where the slanted forms retain core proportions like stem widths while introducing fluid entry and exit strokes for emphasis or stylistic contrast.[1] This pairing promotes consistency in type families, allowing bold variants to align seamlessly with both roman and italic for balanced weighting.[54] Script and display groupings extend these principles into more expressive forms, prioritizing fluidity and ornamentation over strict readability in body text. Script types emulate handwriting with connected, flowing strokes from brush or pointed nib tools, fostering a cursive structure that conveys personality or informality, as seen in designs like Bickham Script.[1] Display types, meanwhile, encompass decorative capitals and bold emphatics optimized for headlines, featuring exaggerated proportions and non-linear elements that depart from alphabetic norms to capture attention without the modular consistency of roman or script.[54] Together, these groups maintain internal harmony, such as uniform stroke modulation, to ensure cohesive application in limited contexts. Beyond Latin alphabets, structural groupings adapt to non-alphabetic systems, exemplified by syllabaries in Hangul and logographic elements in Chinese type. Hangul, the Korean script, organizes phonemic components—14 consonants and 10 vowels—into modular syllabic blocks within square em-units, enabling combinatorial assembly for over 11,000 characters while preserving optical alignment in horizontal or vertical layouts.[61] Chinese type, conversely, relies on logographic characters representing morphemes, each a self-contained unit with 1 to 64 strokes, designed monospaced for dense, grid-based composition that emphasizes semantic density over phonetic sequencing.[62] These non-Latin structures underscore the role of groupings in ensuring consistency, such as pairing weights within a family to harmonize bold forms with standard blocks for cross-script typography.[62]Classification and Design Variables

Serif and sans-serif styles

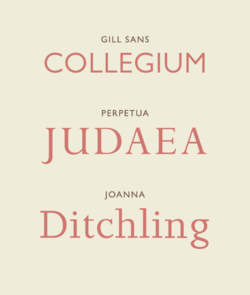

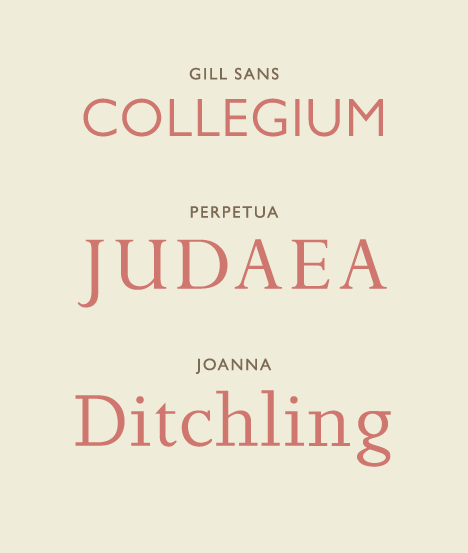

A primary distinction in type design is between serif and sans-serif styles, alongside other categories such as script and blackletter, with serifs defined as the small, decorative lines or strokes attached to the ends of letterforms' main strokes, enhancing visual flow and aiding readability in print media.[63] Serif typefaces emerged in the Renaissance period, drawing from ancient Roman inscriptions where chisel marks created subtle terminals, evolving through the printing press era to formalize these features for better ink distribution on metal type.[28] In contrast, sans-serif typefaces, appearing in the early 19th century, omit serifs for a streamlined, geometric look suited to industrial and modern contexts, initially viewed as unconventional "grotesques" before gaining widespread adoption in signage and advertising.[1] Serif styles are subdivided based on historical development and formal characteristics. Old-style serifs, originating in the 15th century Venetian and French traditions, feature low stroke contrast, bracketed serifs, and diagonal stress, evoking humanistic proportions inspired by handwriting; Bembo exemplifies this with its subtle, organic curves and even weighting.[28][63] Transitional serifs, from the 18th century Enlightenment, bridge old styles and later innovations with moderate contrast and vertical axis alignment, as seen in Baskerville's refined elegance.[28] Modern serifs, developed in the late 18th century by designers like Giambattista Bodoni, emphasize high contrast between thick and thin strokes, unbracketed hairline serifs, and sharp verticality for a neoclassical precision; Bodoni remains iconic for its dramatic, formal presence.[28][63] Slab serifs, emerging in the 19th century as a bold evolution from modern styles, incorporate thick, block-like serifs equal in weight to the strokes, often with minimal bracketing, serving as a transitional form between traditional serifs and sans-serifs due to their mechanical robustness; Rockwell illustrates this with its squared-off, sturdy terminals ideal for headlines and display use.[63][28] Sans-serif styles further diversify by proportion and inspiration. Grotesque sans-serifs, the earliest 19th-century variants, exhibit uneven stroke widths, condensed forms, and a raw, utilitarian feel without classical roots; Akzidenz-Grotesk, released in 1896, pioneered this with its irregular counters and bold neutrality for posters and industrial printing.[1] Humanist sans-serifs, developed in the early 20th century, draw letterform inspiration from old-style serifs, featuring open apertures, slanted stress, and moderate contrast for enhanced legibility; Gill Sans, designed by Eric Gill in 1928, embodies this by adapting Renaissance proportions to sans-serif clarity, making it suitable for extended reading.[1][63] In distinction, geometric sans-serifs prioritize pure shapes like circles and squares, with uniform stroke widths and vertical stress for a futuristic minimalism; Futura, created by Paul Renner in 1927, exemplifies this abstract approach, contrasting the organic flow of humanist designs.[1]Weights, contrasts, and optical variations

In type design, weights determine the overall thickness of strokes in letterforms, influencing visual density and emphasis. Standard weights include light (thinner strokes for subtlety), regular (balanced for body text), bold (thicker for hierarchy), and black (heaviest for impact). The OpenType specification standardizes these on a numerical scale from 100 (thin/light) to 900 (black/extra bold), where 400 denotes regular and 700 bold, enabling precise interpolation in variable fonts.[64][65] Contrast refers to the degree of variation between thick and thin strokes within a single letterform, shaping its expressive quality. High-contrast designs, exemplified by Didone typefaces like Bodoni, exhibit sharp modulation with hairline thins and robust vertical stems, featuring a vertical stress direction characteristic of French modern styles. Low-contrast or monoline forms, common in sans-serif typefaces such as Helvetica, maintain uniform stroke widths for a consistent, unmodulated appearance.[1][53] Optical variations involve subtle adjustments to counteract perceptual distortions, ensuring letterforms appear balanced despite geometric irregularities. A key technique is thinning or curving at junctions where thin and thick strokes converge, preventing visual heaviness or breaks that occur due to optical merging. In Adobe Garamond Pro, these variations are integrated through optically sized masters, which refine stroke weights and contrasts across scales—subtle in regular for text, more pronounced in bold—to maintain harmony without disrupting readability.[66][67] Contrast ratios also influence the emotional tone of a typeface; high modulation conveys elegance and sophistication, often selected for luxury contexts, while low ratios foster neutrality and modernity in sans-serif applications.[68][69]Widths, postures, and case distinctions

In type design, widths refer to the horizontal proportions of letterforms within a typeface family, allowing designers to adapt text to specific spatial constraints while preserving readability. Type widths are classified into categories such as normal (standard proportions), condensed (narrower forms), extended (wider forms), and further variations like compressed (very narrow) and expanded (very wide). These classifications enable precise control over horizontal spacing, impacting layout efficiency and visual impact. Normal width serves as the standard proportion, balancing character spacing for general body text and display uses. Condensed widths, including compressed variants, narrow the letters—often to fit more content into limited areas, such as headlines, narrow columns, or mobile interfaces—without significantly altering vertical dimensions or legibility when properly designed, though extreme narrowing can reduce readability in extended text. Extended widths, conversely, broaden the forms for emphasis in logos, titles, or branding where a bold, expansive presence is desired, enhancing distinctiveness at larger sizes but potentially complicating layouts due to increased space requirements.[58][51][70] Postures describe the angular orientation of letterforms, primarily through slanting to convey motion, emphasis, or stylistic variation. Italic postures involve a deliberate, curved slant typically drawn as distinct forms inspired by handwriting, narrower than their upright counterparts, and historically suited to Romance languages for fluid expression in continuous text. Oblique postures, common in sans-serif typefaces, achieve slant through mechanical shearing of upright forms followed by optical corrections, resulting in a more uniform, less calligraphic appearance that prioritizes simplicity over cursive flow.[51][71] Case distinctions define the vertical structure and height variations among letters, influencing hierarchy and visual rhythm in composition. Uppercase letters, or capitals, feature blocky, uniform forms without ascenders or descenders, reaching a consistent cap height for shouting emphasis or acronyms. Lowercase letters introduce variety with ascenders (e.g., in 'h' or 'k') extending above the x-height and descenders (e.g., in 'g' or 'p') below the baseline, promoting organic flow in running text. Small capitals are scaled uppercase forms matching the x-height of lowercase, ensuring harmonious integration for stylistic abbreviations or emphasis without disrupting line rhythm.[47] For instance, the Frutiger sans-serif family includes condensed widths optimized for high legibility in signage applications, such as airports, where narrower proportions allow clear visibility under constrained conditions.[47]Type families and super families

A type family consists of a coordinated set of related fonts derived from a single typeface design, typically varying in attributes such as weight, width, and style to provide versatility for different typographic needs.[72] For instance, the Helvetica family, originally released in 1957 by the Haas Type Foundry, includes over eight variants encompassing multiple weights like Light, Regular, and Bold, along with italic and condensed styles, allowing designers to maintain visual consistency across applications.[73] Super families represent an expanded evolution of type families, integrating multiple subfamilies that span diverse stylistic categories such as sans-serif, serif, and slab-serif within a unified system, enabling broader adaptability for complex design projects.[74] A prominent example is the Thesis superfamily, designed by Luc(as) de Groot between 1989 and 1994 and first published in 1994 through the FontFont library, which comprises TheSans (sans-serif), TheSerif (serif), and TheMix (a hybrid style blending slab and sans elements), each offering up to eight weights with matching italics across various widths.[75] This modular structure supports extensive language coverage, including Latin, Cyrillic, and Arabic, making it suitable for international branding and identity systems.[75] Large coordinated type families gained prominence in the mid-20th century with designs like Univers, a sans-serif family created by Adrian Frutiger and released in 1957 by Deberny & Peignot, featuring 21 coordinated variations in weights and widths through an innovative numbering system that facilitated systematic selection for branding purposes.[76] Univers pioneered this modular approach by being the first typeface produced simultaneously in hand-set, hot-metal, and phototype formats, establishing a precedent for scalable, cohesive font systems in corporate and editorial design.[76] Advancements in digital typography have further enhanced type families and super families through variable fonts, which encapsulate an entire range of variations—such as weight, width, and slant—within a single file using continuous axes defined in the OpenType specification.[77] The Axis-Praxis project, launched in 2016 by Laurence Penney, exemplifies this by providing an interactive web tool for testing variable fonts, allowing designers to adjust axes like weight and width in real-time to explore design instances without multiple files.[78]Principles of Type Design

Legibility and readability factors

Legibility in type design refers to the ease with which individual glyphs can be distinguished and recognized, particularly at small sizes or distances, ensuring clear perception without ambiguity. A key factor is glyph distinctiveness, where designers avoid visual similarities between characters, such as between lowercase 'l' and uppercase 'I', by incorporating subtle flares, serifs, or varying widths to enhance quick identification. For instance, widening narrow letters like 'f', 'j', 'l', and 't' has been shown to improve recognition accuracy in experimental fonts.[79] Another critical element is counter size—the enclosed white space within letters like 'o', 'e', and 'a'—which becomes especially important at small sizes, as larger counters prevent merging with surrounding strokes and aid differentiation under low-resolution conditions. Research indicates that increasing counter areas in small typefaces significantly boosts letter recognition by providing more visual cues for the eye.[80] Readability extends legibility to the flow of continuous text, focusing on how design choices facilitate sustained reading without fatigue. Optimal line length typically ranges from 45 to 75 characters per line, including spaces, to minimize disruptive eye movements and maintain focus; lines shorter than 45 characters increase saccades, while longer ones exceed the optimal visual span. Leading, or line spacing, should ideally be 1.2 to 1.5 times the x-height to allow sufficient vertical breathing room, preventing crowding and improving scannability, with studies showing double spacing (approximately 2x) enhances on-screen reading speed compared to single spacing. Even color in text blocks—the uniform density of ink across a paragraph—contributes to readability by avoiding "rivers" of white space or overly dense patches, achieved through consistent stroke weights and kerning that distribute visual weight evenly.[81][82][79] Additional factors influencing legibility and readability include stroke uniformity, which varies by medium: uniform strokes perform better on screens due to pixel rendering limitations, reducing aliasing and blurring compared to high-contrast variations suited for print. Studies confirm that low-contrast, uniform stroke fonts like Courier enable faster reading at small sizes on digital displays than high-contrast ones like Times Roman. For specific populations, dyslexia-friendly designs such as OpenDyslexic incorporate weighted bottoms on letters to counteract perceived flipping or rotation, aiming to enhance stability and reduce visual stress, though empirical results on reading speed improvements remain mixed. Overall, research suggests sans-serif typefaces offer slightly better digital legibility than serif ones owing to their uniform strokes and larger x-heights, which adapt well to low-resolution environments.[79][79][83][84]Rhythm, proportion, and harmony

In type design, rhythm refers to the visual cadence created by the patterned flow of letterforms, which guides the reader's eye across text in a natural, engaging manner. This quality emerges from the alternation of thick and thin strokes within glyphs, establishing a consistent texture that mimics natural movements and reduces visual monotony. For instance, the contrast between heavier stems and lighter serifs or curves forms a repetitive motif that unifies the typeface, contributing to an overall sense of movement and balance. Designers like those at the Font Bureau emphasize that arranging these thicks and thins is essential for assembling coherent shape systems, where high contrast can amplify dramatic effects while low contrast promotes subtlety.[85] Kerning plays a pivotal role in sustaining this rhythm by adjusting the space between specific letter pairs to achieve even visual spacing, preventing awkward gaps or overlaps that disrupt the flow. Unlike uniform tracking, which applies global adjustments, kerning targets problematic combinations—such as the space between "A" and "V"—to maintain an optical equilibrium between black (strokes) and white (spaces). According to Adobe's typography guidelines, effective kerning ensures polished harmony, particularly in display settings, where uneven spacing can otherwise create tension and hinder the text's cadence. In broader terms, letter spacing methods, including optical compensation, help balance the "color" of a text block, fostering a rhythmic consistency that aligns with natural perceptual patterns.[86][87] Proportion in type design involves harmonious relationships among letter elements, often influenced by mathematical ratios like the golden ratio (approximately 1:1.618), which informs scalable hierarchies in sizing, spacing, and overall structure. This principle extends to letter spacing, where proportional adjustments—such as scaling line heights or inter-character gaps by the golden ratio—create balanced compositions that enhance flow without overwhelming the reader. The Nielsen Norman Group highlights its application in typography, noting that body text at 16px with a line height of about 26px (16 × 1.618) optimizes readability by aligning with human visual preferences for symmetry. Within type families, harmony is achieved through consistent proportions across weights and styles, ensuring that variants like bold or italic maintain the core rhythm without introducing discord.[88] Exemplifying dramatic rhythm, the Bodoni typeface employs extreme high contrast between thick vertical stems and hairline horizontals, producing a vertical emphasis that creates a pulsating visual energy ideal for headlines and editorial use. This stark alternation evokes a sense of elegance and tension, drawing the eye through text with theatrical flair while preserving legibility at larger sizes. In contrast, monospace fonts like those designed for coding prioritize uniform character widths to foster harmony in technical contexts, where even texture across glyphs—despite fixed spacing—ensures predictable alignment and reduces visual clutter in code blocks. As noted by type designer Mark Bloom, maintaining this even texture in monospaced designs is challenging but crucial for seamless readability in programming environments.[89] Proper rhythm, supported by balanced proportions and spacing, contributes to overall readability by minimizing visual strain during extended reading sessions. Ideal tracking values typically range from 0 to 100 units per em (thousandths of an em), allowing fine-tuned loosening or tightening to suit context without compromising harmony—values beyond this can distort the typeface's inherent rhythm. This approach indirectly alleviates eye fatigue, as consistent visual patterns align with perceptual expectations, echoing legibility principles where even spacing supports sustained focus.[90][91]Optical illusions and adjustments

In type design, optical illusions arise from the human visual system's tendency to misperceive geometric forms, necessitating compensatory adjustments to ensure letters appear balanced and proportional. One prominent illusion causes circular or curved elements, such as the lowercase 'o', to appear taller when aligned to the baseline compared to flat-sided letters like 'x', due to the way curves interact with horizontal alignments. To counteract this, designers apply overshoot, extending the curve slightly beyond the x-height—typically by about 5%—so that the 'o' visually matches the height of straight-edged forms. This adjustment, known since early typographic practices, ensures rhythmic harmony in letterforms without relying solely on mathematical precision.[59] Another key illusion, the horizontal-vertical effect, makes horizontal strokes appear thicker than vertical ones of identical width, a perceptual bias confirmed in visual perception studies. Type designers compensate by thickening vertical strokes by approximately 10-15% relative to horizontals, as seen in letters like 'H' or 'T', to achieve uniform apparent weight across the glyph. For instance, in classic serifs like Times Roman, curves may be adjusted up to 20% thicker than vertical stems to maintain optical consistency. These tweaks enable the proportional ideals discussed in type rhythm and harmony, where even subtle distortions prevent visual imbalance.[59][92] Practical adjustments extend to production contexts, where ink trapping addresses ink spread in offset printing by incorporating small notches at stroke junctions, preventing filled-in corners and preserving sharpness at small sizes. Similarly, for low-resolution screens, hinting instructions align Bézier curve paths to pixel grids, minimizing jagged edges and ensuring curves fit optically without aliasing. In Bézier-based design, curve fitting involves iteratively adjusting control points to approximate ideal forms while compensating for illusions, such as elongating horizontals in perfect circles to counter perceived shortness.[93][94][95] Experimental typefaces from foundries like Emigre exemplify radical optical distortions for postmodern effects, where designers like Zuzana Licko deliberately exaggerated overshoots and stroke modulations in fonts such as Mrs Eaves to evoke digital grit and challenge traditional legibility. These intentional illusions, drawn with distorted Bézier paths, prioritize expressive disruption over strict correction, influencing late-20th-century digital typography. Such approaches highlight how optical adjustments can serve both corrective and artistic purposes in type creation.[96]Cultural and contextual influences

Type design has historically been shaped by cultural biases, particularly a Latin-centric perspective that dominated early European printing traditions and marginalized non-Latin scripts. This Euro-centric approach is evident in typography education and reference materials, which often focus exclusively on Latin alphabets while using colonial terminology like "Non-Latin" or "Orientales" to describe other writing systems, thereby framing them as peripheral or exotic.[97] Such biases have influenced global standards, limiting the development of typefaces for diverse scripts until recent decades.[98] Adaptations for right-to-left (RTL) scripts, such as Hebrew, require specific adjustments to accommodate directional flow and visual harmony. Hebrew typefaces often feature widened characters like צ and ש, narrowed forms like ד and ה, and varied stroke terminations inspired by broad-nib calligraphy to enhance legibility and texture in continuous text, diverging from Latin conventions.[99] Designs like Rapida Hebrew integrate energetic cursive elements from "Ktiv" (fast writing) with geometric and calligraphic details, ensuring compatibility in trilingual systems while respecting RTL directionality and avoiding monotonous serifs.[100] Contextual factors further influence type choices, distinguishing display faces—optimized for large-scale, short-form use like posters, where bold, expressive forms such as heavy weights grab attention—from text faces, which prioritize even spacing and subtle contrasts for sustained readability in body copy.[101] For accessibility, particularly for low-vision users, typefaces incorporate larger counters and open apertures to improve letter recognition, as seen in designs like Atkinson Hyperlegible, which expands internal spaces in characters to reduce visual crowding.[102] These features enhance legibility in contexts like signage or digital interfaces without compromising overall aesthetics.[103] Globalization, facilitated by Unicode since 1991, has profoundly impacted type design by providing encoding for up to 1,114,112 code points across scripts, with 159,801 characters assigned as of September 2025.[40] This has spurred the creation of "united" type families that harmonize diverse glyphs, such as decodeunicode's integration of 99,000+ characters for scripts like Ethiopic and Aramaic, fostering inclusivity in global design.[104] Efforts to decolonize type design address historical exclusions by reviving indigenous scripts, exemplified by the 2014 release of Phoreus Cherokee, a serif typeface adapted from Latin forms to support the Cherokee syllabary's 85 characters. Developed with input from Cherokee Nation archives, it includes simplified glyphs, a new lowercase variant—the first in 195 years—and small caps for bilingual use, aiding language preservation among 22,000 native speakers.[105] Such projects challenge Latin dominance and promote cultural equity in typography.[106] In East Asian contexts, typefaces for Chinese, Japanese, and Korean (CJK) scripts emphasize vertical density to suit dense text blocks, with recommended leading of about 1.7 times the font size—such as 17 points for 10-point text—to balance high information density per character while maintaining readability in vertical or horizontal layouts.[62] This approach accounts for scripts' stroke complexity, ensuring harmonious flow in publications like newspapers or books.[62]The Profession and Practice

Tools, software, and workflows

Type designers rely on a combination of traditional and digital tools to create and refine fonts, with specialized software enabling precise control over glyph construction and font metrics. Key applications include FontLab, which serves as an integrated editor for Mac and Windows, supporting the full process from initial design to complex projects involving variable fonts, color fonts, and OpenType features using both Bézier and TrueType outlines.[107] Glyphs offers a user-friendly interface with built-in tools for professional workflows, making it accessible for creating high-quality fonts while handling Bézier curve editing efficiently.[108] RoboFont provides a customizable, scriptable environment via Python, ideal for advanced users needing extensibility in glyph drawing and automation, including its dedicated Bézier Tool for contour creation.[109] For preliminary stages, Adobe Illustrator is commonly employed to sketch and vectorize initial designs, converting hand-drawn elements into editable paths before import into font editors.[110] Workflows in type design typically commence with hand sketching to explore forms and proportions, often on paper or tablets, allowing designers to iterate freely without technical constraints. These sketches are then digitized by tracing outlines with cubic or quadratic Bézier curves—cubic for PostScript-based OpenType fonts (OTF) and quadratic for TrueType fonts (TTF)—to define smooth, scalable glyph shapes mathematically.[95] Once digitized, fonts are refined for spacing, kerning, and features in the primary editor, followed by testing in layout software like Adobe InDesign to evaluate legibility across sizes and contexts, using sample texts or pangrams to reveal rendering issues.[111][50] Final output involves exporting to standard formats such as OTF for advanced typographic controls or TTF for broad compatibility, ensuring the font integrates seamlessly with operating systems and applications. Proofing occurs through high-resolution digital renders to inspect details like hinting and rasterization, supplemented by physical print tests on various papers and devices to assess real-world performance and optical adjustments.[112] Tools like Font Proofer facilitate this by generating comprehensive proof documents directly from editors such as Glyphs or RoboFont.[113] In the 2020s, AI-assisted features have augmented traditional workflows, particularly in interpolation for generating intermediate weights or styles between master designs, reducing manual effort while preserving typographic harmony.[114] These tools analyze existing glyphs to suggest or automate variations, enabling faster iteration in complex families, though human oversight remains essential for nuanced adjustments.Education, training, and collaboration

Formal education in type design typically involves specialized programs that blend theoretical knowledge with practical skills in typeface creation. The Type@Cooper program at The Cooper Union in New York City offers post-graduate certificate options, including an Extended Program for working professionals and a Condensed Program, focusing on typeface design principles through hands-on workshops led by industry experts.[115] Similarly, the University of Reading in the UK provides an MA in Communication Design with a Typeface Design pathway, emphasizing multiscript typeface development, historical context, and theoretical issues over one year of full-time study.[116] For accessible entry, online platforms like FutureLearn host courses such as Graphic Design Essentials: Introduction to Typography, which covers type anatomy, classification, and design choices for beginners.[117] Training paths often extend beyond academia through apprenticeships and self-directed learning. Apprenticeships at institutions like the Type Archive in London provide hands-on experience in typographic engineering and historical typefounding techniques, aiming to preserve skills amid a declining workforce.[118] Foundries such as The Northern Block offer structured apprenticeships in font technology, combining technical production with design under mentorship.[119] Self-taught designers frequently build expertise by contributing to open-source projects; for instance, independent creators like Matthijs Herzberg have developed and licensed fonts through self-study and iterative practice using tools like Glyphs software.[120] Collaboration is integral to modern type design, particularly in large-scale projects at tech companies. Adobe's typeface team, including specialists like Paul D. Hunt, collaborates on Adobe Originals, curating and developing fonts for integration across Creative Cloud applications.[121] Google Fonts fosters global partnerships with designers, such as collaborations with Yoshimichi Ohira to expand Japanese typeface offerings, enabling shared contributions to an open library of over 1,500 font families.[122] Crowdsourcing via platforms like GitHub supports variable font development, as seen in repositories converting open-source fonts to variable formats for community refinement and distribution.[123] Post-2020 efforts have increasingly addressed diversity in type design, with initiatives promoting women's contributions to counter historical underrepresentation. The Women in Type project researches and highlights female-led typeface designs from the 20th century, fostering awareness and inclusion in the field.[124] Readymag's Designing Women initiative, relaunched in 2024, celebrates diverse women and nonbinary designers through profiles and resources to build gender equity.[125] Similarly, Femme Type creates platforms for uplifting women's typographic work, encouraging broader participation in design communities.[126]Legal aspects and distribution

Type designs are subject to varying intellectual property protections across jurisdictions, primarily through copyright laws that treat them differently from other graphic works. In the United States, the shapes and designs of typefaces themselves are not eligible for copyright protection, as they are considered utilitarian and functional; however, the digital font software that generates them can be copyrighted as computer programs.[127] In contrast, many European Union member states, such as France and Germany, recognize typefaces as artistic works eligible for copyright protection, provided they demonstrate sufficient originality and creative authorship.[128] Under international standards like the Berne Convention, which both the US and EU adhere to, copyright for such protectable elements generally lasts for the life of the author plus 70 years after their death.[129][130] Licensing forms the core mechanism for controlling and monetizing typeface use, with end-user license agreements (EULAs) dictating permissible applications. Desktop licenses typically allow installation on individual or multi-user workstations for creating print materials, static images, or documents, but prohibit embedding in distributable software or websites without additional permissions. Web embedding licenses, often provided as WOFF or WOFF2 files, enable fonts to be hosted on servers for display across browsers and devices, with usage limits based on page views or traffic volume to ensure scalability. For open and freely distributable fonts, licenses like the SIL Open Font License (OFL) permit modification, redistribution, and commercial use without royalties, while Creative Commons variants, such as CC BY-SA, support sharing with attribution and share-alike conditions, fostering collaborative typeface development.[131][132][133][134] Distribution of typefaces occurs primarily through specialized foundries and platforms that manage sales, updates, and compliance. Monotype, one of the largest foundries, operates marketplaces like MyFonts to enable independent designers to sell their work globally, offering tiered licensing options that adapt to client needs such as enterprise-wide deployment. Piracy remains a persistent challenge, with practices like font ripping—extracting embedded fonts from PDFs or applications using specialized tools—leading to unauthorized copying and widespread illegal sharing on file-hosting sites. In the 2020s, some designers have experimented with non-fungible tokens (NFTs) to create verifiable, unique digital certificates of ownership for custom typefaces, aiming to combat piracy through blockchain-based provenance.[135][136]Notable designers and foundries

Eric Gill, an English sculptor and type designer, created the sans-serif typeface Gill Sans in 1928 for the Monotype Corporation, drawing inspiration from Edward Johnston's London Underground signage to produce a clean, humanist design widely adopted for British branding and publishing.[137][138] Adrian Frutiger, a Swiss designer, developed the Univers typeface family in 1957 for Deberny & Peignot, introducing a systematic neo-grotesque sans-serif with multiple weights and widths that emphasized legibility and versatility across print media.[139][76] Zuzana Licko, co-founder of Emigre Fonts, pioneered digital type in the 1980s by designing bitmap fonts like Oakland for early Macintosh systems, pushing boundaries in low-resolution typography and influencing the experimental aesthetic of desktop publishing.[140][141] Matthew Carter's Verdana, released in 1996 for Microsoft, marked a significant advancement in screen typography with its wide letterforms and generous spacing optimized for low-resolution displays, becoming a standard for web readability.[142][143] Historical foundries like Linotype, established in 1886, revolutionized type production through its hot-metal composing machines, enabling efficient casting of lines of text and supporting the development of numerous classic faces for newspapers and books.[144] Modern foundries such as Dalton Maag, founded in 1991, specialize in multilingual typefaces supporting over 870 languages, including Latin, Cyrillic, and Arabic extensions, for global branding and user interfaces.[145] The Indian Type Foundry focuses on non-Latin scripts like Devanagari, Bengali, and Tamil, creating responsive fonts that address the complexities of Indic writing systems for digital and print applications in South Asia.[146] Contemporary studios like Dinamo, based in Berlin since 2009, advance experimental type design through variable fonts and custom projects, such as interactive tools for real-time customization, blending historical influences with innovative software-driven approaches.[147] Recent efforts in inclusivity highlight designers like Kristyan Sarkis, a Beirut-born type designer based in Amsterdam, whose work at TPTQ Arabic promotes diverse non-Latin typographies, including Arabic extensions for broader cultural representation in global design.[148][149]References

- ftp://ctan.math.utah.edu/tex-archive/info/memdesign/memdesign.pdf